Abstract

Objectives

Medicaid’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) pediatric benefit is designed to meet children’s medically necessary needs for care. A 2018 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Bulletin advised Medicaid programs to ensure that their dental payment policies and periodicity schedules include language that highlights that medically necessary care should be provided even if that care exceeds typical service frequency or intensity. We assessed the extent to which Medicaid agencies’ administrative documents reflect EPSDT’s flexibility requirement.

Methods

From August 2018 through July 2019, we retrieved dental provider manuals, periodicity schedules, and fee schedules in all 50 states and the District of Columbia; analyzed these administrative documents for consistency with the CMS advisory; and determined whether instructions were provided on how to bill for services that exceed customary frequencies or intensities.

Results

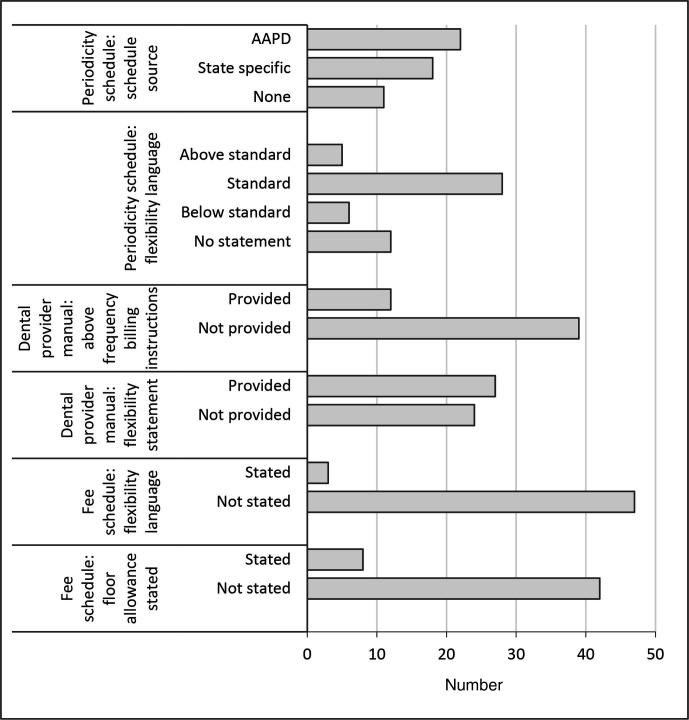

Dental-specific periodicity schedules were not evident in 11 states. Eighteen states did not include flexibility language, for example, as advocated by the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Flexibility language was not evident in 24 dental provider manuals or in 47 fee schedules. Only 8 states provided billing instructions within fee schedules for more frequent or intensive services.

Conclusion

Updating Medicaid agency administrative documents—including dental provider manuals and periodicity and fee schedules—holds promise to promote individualized dental care as ensured by EPSDT.

Keywords: Medicaid, dental care, children, pediatric dentistry, preventive health, oral health

Within 2 years of Medicaid’s enactment in 1965, President Johnson pressed Congress to institute a special health benefit for low-income children. In 1967, that special consideration became the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit for all Medicaid beneficiaries aged <21 years. 1 The Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Payment and Access Commission today describes EPSDT as providing “access to any Medicaid-coverable service in any amount that is medically necessary, regardless of whether the service is covered in the state [Medicaid] plan.” 2

President Johnson was motivated by Head Start research that found early-life evidence of nascent disabilities and by a federal task force investigating Selective Service System findings that half of military draftees were unqualified for service because of disabilities, many of which could have been prevented or ameliorated early in life. 3,4 One of those disabilities—consequential tooth decay—persists today, with the US Department of Defense reporting “historically abysmal dental readiness” among reservists and a high rate of dental emergencies among active-duty service members. 5,6 Because tooth decay progresses throughout the life course, these dental disabilities among adults reflect persistent failure to adequately address the high prevalence of preventable tooth decay in childhood, particularly among children from low-income families insured by Medicaid and CHIP.

For oral health and dental care, EPSDT has yet to meet its intended outcome. The 2000 US Surgeon General’s report on oral health highlighted challenges to effective implementation of EPSDT that include inadequate funding for Medicaid and CHIP programs, chronically low levels of reimbursement for dental providers coupled with perceived excess paperwork and electronic requirements, and access-to-care challenges for eligible enrollees, in which people with the highest risk for dental disease are the least likely to have access to regular dental care. 7 An updated 2020 US Surgeon General report on oral health revisited the longstanding conditions that prevent optimal outcomes for all children and adolescents and provides direction for future oral health care design and delivery. 8 Both reports address pediatric caries prevalence, consequence, and importance for adult oral health and function. One finding is that tooth decay is the most common chronic disease among US children and adolescents, with a prevalence of 45.8% among people aged 2-19. 9

Racial/ethnic disparities also persist, with Latino and non-Hispanic Black children and adolescents having a higher prevalence of tooth decay than their non-Hispanic White peers (57.1%, 48.1%, and 40.4%, respectively). 9 People aged 2-19 from families with lower socioeconomic status receive fewer preventive oral health services than their more advantaged peers do. 9 The level of unmet need for dental services in low-income families is more than double the unmet need for medical care. 10 Having failed to reach Healthy People 2010 objectives for dental care use, the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion at the US Department of Health and Human Services issued a comprehensive legal and policy analysis in 2020 suggesting that dental care use can be enhanced through actions that expand financing, augment workforce (including interprofessional health workforce), and address logistical and cultural barriers to care. 11

Although EPSDT requires that Medicaid provides, at a minimum, the “relief of pain and infections, restoration of teeth, and maintenance of dental health,” 3 it also recognizes that to achieve equitable oral health outcomes, the intensity of each child’s dental care needs to be proportionate to a child’s individual risk for caries. Such tailored flexibility and individualization, inherent in EPSDT, reflects advances in professional guidance on caries risk assessment 12 and individualized care paths 13 and is consistent with health care advances more generally that promote value-based care supported by alternative payment mechanisms. 14,15

To ensure that dental care meets EPSDT standards, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released an Informational Bulletin in 2018 that advises states to ensure that their Medicaid pediatric dental payment policies and periodicity schedules align with EPSDT requirements. 16 The Bulletin cites requirements dating to the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989 17 that states provide “all medically needed dental services beyond what is covered under the state’s Medicaid plan.” 16 The Bulletin calls on states to (1) specify the periodicity schedule with which preventive and medically necessary dental restorative services are to be provided; (2) have a mechanism in place to cover medically necessary dental services that exceed the periodicity schedule, recognizing the periodicity schedule as a floor for coverage rather than a ceiling; and (3) ensure that fee schedules and payment policies are aligned with periodicity schedules. Although the Bulletin did not establish new policy, its release signified a growing awareness among policy makers that intensity and frequency of dental services must be tailored to each child’s risk for dental caries. 12,18,19 Each Medicaid agency, regardless of its private contractual agreements for program administration, is also required to make readily available benefit information for enrollees and policies for Medicaid providers. 20

The objective of this study was to assess the extent to which Medicaid agencies’ administrative documents reflect EPSDT’s availability requirement and the 3 dental service requirements detailed in the Bulletin. We examined publicly available pediatric dental periodicity schedules, statements of covered services as described in dental provider manuals, and fee schedules for all 50 states and the District of Columbia to determine whether medically necessary individualized dental care as required by EPSDT is being upheld in the existing and increasingly complex structures of Medicaid financing and administration.

Methods

We created a conceptual framework to assess the conformity of state documents with CMS guidance (Table 1). One investigator (C.F.) performed structured internet searches using the key phrase “[state name] Medicaid dental provider manual” using the Google Chrome search engine from August 2018 through July 2019 to locate publicly available dental provider resources posted by Medicaid agencies. We did not explore dental managed care or administrative services contractors’ websites except in the 8 states in which a single statewide vendor supplied these documents through a link on the state’s web page. Dental provider resources were otherwise available through a state’s online Medicaid provider portal or web page or were contained in a Medicaid provider manual. Some manuals were downloadable as single files, whereas others separated components into service-specific chapters or sections. The resources of interest were (1) dental-specific periodicity schedules, (2) statements of covered services in dental provider manuals, and (3) dental fee schedules. These resources are among the most commonly referenced documents by dental providers and their staff members when questions arise about service provision, benefit limits, and payment policies. Resources were assessed for statements about flexibility of services on the basis of individual patients’ needs, with a particular focus on preventive services. This qualitative assessment of resource language was assessed categorically as described hereinafter.

Table 1.

Conceptual framework used to assess conformity of state Medicaid dental provider documents with CMS guidance on the provision of and payment for medically necessary dental services for children and adolescents as required by the EPSDT benefit

| CMS May 2018 Informational Bulletin directive a | State document data source | Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Specify the periodicity schedule with which preventive and medically necessary restorative services would be provided. | Periodicity schedule |

|

| Have a mechanism in place to cover medically necessary dental services that exceed the periodicity schedule, recognizing the periodicity schedule as a floor for coverage of dental services rather than a ceiling. | Dental provider manual |

|

| Ensure that fee schedules and payment policies are aligned with periodicity schedules. | Fee schedule |

|

Abbreviations: CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; EPSDT, Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment.

aData source: CMS Informational Bulletin. 16

Periodicity Schedules

We categorized dental-specific periodicity schedules as the current American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) schedule, 21,22 state-specific schedule, or no schedule. Periodicity schedules that were either outdated or modified AAPD schedules were classified as state specific. States that referenced the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Bright Futures medical periodicity schedule but no dental-specific schedule were classified as having no dental-specific periodicity schedule, because these recommendations do not meet federal standards for dental care. 23

Schedules were assessed for language on flexibility as “standard” if consistent with the AAPD’s periodicity schedule language, “above standard” if the schedule provided additional language or emphasis, “below standard” if this language was reduced, or “no standard” if none was identified. The AAPD language detailed in the header of its periodicity schedule states, “Since each child is unique, these recommendations are designed for the care of children who have no contributing medical conditions and are developing normally. These recommendations will need to be modified for children with special health care needs or if disease or trauma manifests variations from normal.” 21

Covered Services in Dental Provider Manuals

Detailed dental procedure–specific benefits such as allowable services, service frequencies, or age eligibility are typically referred to as “covered services.” When addressing covered services, manuals may include introductory information that explains EPSDT and provides general guidance on benefit flexibility as appropriate to meet children’s medically necessary needs. Manuals were classified as “yes” if they included such guidance and “no” if they did not include such guidance.

To assess the flexibility in the provision of preventive dental services, we reviewed the dental provider manuals for guidance on 3 common diagnostic and preventive services: dental examination, dental prophylaxis, and topical fluoride treatment (Current Dental Terminology codes D0120/D0150, D1120, and D1206/D1208, respectively). 24 We classified manuals as “yes” if they contained clear language describing the mechanism by which dentists can be paid for these services when delivered with greater frequency or intensity than specified in the periodicity schedule because of medical necessity based on caries risk and “no” if they did not include such guidance.

Fee Schedules

We assessed publicly accessible fee schedules—obtained through searches of dental manuals, provider portals, or as separate files—for language on flexibility in terms of the allowable frequency for each aforementioned diagnostic or preventive service. Stated allowable frequencies established the floor for routine care of children who do not require enhanced care.

Results

Periodicity Schedule

Twenty-two states cited the AAPD schedule, 17 states and the District of Columbia provided a state-specific schedule, and 11 states had no identifiable schedule (Table 2, Figure). Twenty-seven states and the District of Columbia met the standard category, 5 states met the above-standard category, and 6 states met the below-standard category for the AAPD statement on flexibility. Twelve states had no statement on benefit flexibility, including 11 states with no periodicity schedule.

Table 2.

Assessment of states’ Medicaid documents for compliance with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Informational Bulletin a , 50 states and the District of Columbia, 2018-2019

| State | Periodicity schedule | Dental provider manual | Fee schedule | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Statement on flexibility | General statement on flexibility | Mechanism described for additional services | General statement on flexibility | Allowable frequency of services specified | |

| Alabama | State | Below | ✓ | |||

| Alaska | AAPD | Standard | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Arizona | State | Above | ✓ | |||

| Arkansas | AAPD | Standard | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| California | AAPD | Standard | ||||

| Colorado | State | Below | ✓ | |||

| Connecticut | AAPD | Standard | ✓ | |||

| District of Columbia | State | Standard | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Delaware | None | NA | ✓ | |||

| Florida | AAPD | Standard | ||||

| Georgia | AAPD | Standard | ||||

| Hawaii | State | None | ||||

| Idaho | AAPD | Standard | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Illinois | AAPD | Standard | ✓ | |||

| Indiana | AAPD | Standard | ||||

| Iowa | AAPD | Standard | ||||

| Kansas | AAPD | Standard | ||||

| Kentucky | None | NA | ||||

| Louisiana | State | Standard | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Maine | State | Above | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Maryland | State | Standard | ||||

| Massachusetts | AAPD | Standard | ✓ | |||

| Michigan | AAPD | Standard | ✓ | |||

| Minnesota | AAPD | Standard | ✓ | |||

| Mississippi | None | NA | ||||

| Missouri | None | NA | ✓ | |||

| Montana | None | NA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Nebraska | AAPD | Standard | ✓ | |||

| Nevada | AAPD | Standard | ✓ | |||

| New Hampshire | AAPD | Standard | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| New Jersey | State | Below | ✓ | |||

| New Mexico | None | NA | ||||

| New York | None | NA | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| North Carolina | State | Above | ✓ | |||

| North Dakota | None | NA | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Ohio | State | Below | ||||

| Oklahoma | State | Standard | ||||

| Oregon | State | Above | ||||

| Pennsylvania | None | NA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Rhode Island | State | Below | ||||

| South Carolina | State | Standard | ✓ | |||

| South Dakota | None | NA | ✓ | |||

| Tennessee | State | Standard | ND | ND | ||

| Texas | AAPD | Standard | ✓ | |||

| Utah | AAPD | Standard | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Vermont | State | Above | ✓ | |||

| Virginia | AAPD | Standard | ✓ | |||

| Washington | None | NA | ✓ | |||

| West Virginia | AAPD | Standard | ✓ | |||

| Wisconsin | AAPD | Standard | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Wyoming | State | Below | ✓ | |||

Abbreviations: AAPD, American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; NA, not available; ND, not determined.

aData source: CMS Informational Bulletin. 16

Figure.

Number of states with EPSDT-consistent Medicaid documents reflecting dental providers’ requirement to provide, and Medicaid agencies’ obligation to appropriately pay for, medically necessary dental services for children and adolescents per guidance in the May 2018 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Informational Bulletin, 16 50 states and the District of Columbia, 2018-2019. Abbreviations: AAPD, American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; EPSDT, Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment.

Covered Services in Dental Provider Manuals

Twenty-six states and the District of Columbia included a general statement on flexibility within the covered services section of their dental provider manual, and 24 did not (Table 2). Eleven states and the District of Columbia (8 with and 4 without a general statement on flexibility) specified the mechanism for the provision of and payment for preventive services exceeding the periodicity schedule when medically necessary, and 39 states did not.

Fee Schedule

Three states included a general statement on flexibility in their fee schedule, 8 states specified the allowable frequency of services by procedure code in their fee schedule, and 38 states and the District of Columbia provided no indication that services can be provided with greater frequency when medically necessary. The fee schedule for 1 state was not publicly available on the state’s website or through its link to its dental benefits administrator (Table 2).

Discussion

The finding that 11 states had no publicly available dental-specific periodicity schedule and 18 states provided either no individualized flexibility language or provided language that was below standard in their periodicity schedule raises concern that states are not informing dentists and beneficiaries of EPSDT requirements. Most states do not include individualized flexibility language in their dental fee schedule, which is perhaps the most commonly referenced dental provider document. Because dentists depend on fee schedules for allowable charges, the finding that only 8 states detailed the allowable frequency of specific preventive services suggests that dentists may be unaware of the minimum covered service levels established by states.

The AAPD’s Policy Center tracks states’ adoption of its periodicity schedule. 25 Between our 2018 analysis and AAPD’s June 2020 web posting, 6 states changed the source of their periodicity schedule: 4 from state-specific to AAPD and 2 from state-specific to none. As a result of these changes, 3 states retained standard flexibility language (equivalent to AAPD’s), 2 states reduced the quality of flexibility language, and 1 state enhanced the quality of flexibility language. These changes in both variability across states and instability within states indicate that states may modify their Medicaid plans at any time with CMS approval.

Despite shortcomings in providing EPSDT-supportive language in most states, the availability of dental-specific periodicity schedules today evinces a marked improvement over the status in 2005, when an analysis found that “few state Medicaid agencies have published or made available separate periodicity schedules for dental services.” 26 A 2009 brief on improving EPSDT periodicity schedules noted that most states base their periodicity schedules on American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations, particularly Bright Futures Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care, 27 rather than on dental-specific schedules, and that these medical association recommendations do not meet federal standards for dental care. 23

No states met criteria across all of their documents for informing dental providers about the inherent individualization flexibility that is a fundamental characteristic of the EPSDT benefit. However, some states provided language that is notably compliant with EPSDT requirements. Maine and Utah provided excellent examples of guidance in most but not all documents. Although Maine’s periodicity schedule was above standard and its fee schedule provided specific language on flexibility and minimum covered services, its dental provider manual did not provide information on flexibility or billing mechanisms for enhanced services. In Utah, the state-specific periodicity schedule was above average, the dental provider manual described flexibility but did not provide information on billing for enhanced medically necessary services, and the fee schedule described preventive benefits’ minimum coverage but did not provide flexibility information. In general, fee schedules—presumably the most commonly referenced of the 3 dental provider documents—less frequently provided flexibility guidance than did dental provider manuals or periodicity schedules. Only a few states included statements on flexibility or specific information on allowable frequency of service delivery and payment in their fee schedules. Notable examples of clear language supporting individualized medically necessary dental care for children are available in these documents, such as one state’s inclusion of, “It is strongly recommended that the dental periodicity schedule be used as a guide for the provision of services with the understanding that services may be provided more frequently as medically indicated” in its dental provider manual (Table 3). 28 -33

Table 3.

Examples of language in state Medicaid dental provider documents that is consistent with the EPSDT standard on individualized flexibility that meets medical necessity and reflects compliance with CMS directives a

| Dental provider resource | Best practice | State |

|---|---|---|

| Periodicity schedule | “The AAPD and DACP [Oklahoma Health Care Authority Dental Advisory Committee on Periodicity, the Oklahoma Medicaid agency] emphasize the importance of very early professional intervention and the continuity of care based on the individualized needs of the child.” b | Oklahoma |

| “As in all medical care, dental care must be based on the individual needs of the member and the professional judgement [sic] of the oral health provider.” c | Arizona | |

| Dental provider manual section on covered services | “When a Medicaid eligible member requires medically necessary services, those services may be covered by Medicaid. Necessary health care, diagnostic services, treatment or other measures described in Section 1905 (a) of the Social Security Act to correct or ameliorate defects, physical or mental illness or conditions discovered by screening services are available based on medical necessity. Prior authorization may be required before providing services. More information on expanded services is provided throughout this manual.” d | Utah |

| “It is strongly recommended that the Dental Periodicity Schedule be used as a guide for the provision of services with the understanding that services may be provided more frequently as medically indicated.” e | Illinois | |

| Fee schedule | “Children under 21 years of age are eligible for all medically necessary dental services. For children under 21 years of age who require medically necessary dental services beyond the fee schedule limits, the dentist should request a waiver of the limits, as applicable, through the waiver process.” f | Pennsylvania |

| “MaineCare will cover all medically necessary dental services for members under age twenty-one (21) pursuant to Section 94 of the MaineCare Benefits Manual, Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment Services.” g | Maine |

Abbreviations: AAPD, American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; EPSDT, Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment.

aData source: CMS Informational Bulletin. 16

bOklahoma Health Care Authority. 28

cArizona Health Care Cost Containment System. 29

dDivision of Medicaid and Health Financing. 30

eIllinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services Dental Program. 31

fPennsylvania Department of Human Services. 32

gMaine Department of Health and Human Services. 33

Our findings support recommendations that hold promise for correcting identified deficiencies (Box). They include suggestions for clarity on EPSDT’s relevance to dental care, refinement and posting of critical documents that dental providers use to learn about the Medicaid program, and alignment of all documents to support flexibility to meet children’s medically necessary dental services. These policy recommendations may be advanced by state Medicaid agencies themselves and by contractors, dental providers, consumers, and other advocates that influence state Medicaid policy.

Box. Recommendations for Medicaid agencies and contractors, dental providers, consumers, and other advocates to ensure agencies’ program and administrative documents reflect the need for dental providers to provide medically necessary care to children and adolescents and for Medicaid agencies to appropriately pay for this care, consistent with EPSDT and the May 2018 CMS Informational Bulletin a .

| Review the state agency’s program and administrative documents for the following: |

| 1. Adopt a dental-specific periodicity schedule and make it widely available and easily accessible to dental providers and patients/families. |

| 2. Review the periodicity schedule for language pertaining to EPSDT and inherent flexibility in the Medicaid and CHIP programs. |

| 3. Wherever specific services and their indications and frequency are described in the dental provider manual (most often in a “covered services” or similarly titled section), clear directions should be given to dental providers about the accommodations that should and must be made in terms of frequency and intensity of services for children who have a high risk of caries or extensive treatment needs that exceed what is specified in the periodicity schedule, as well as detailed directions to ensure payment for same. |

| 4. Fee schedules should include a general statement on flexibility, reminding dental providers of the inherent flexibility for risk-adjusted care and their ability for increased reimbursement for medically necessary service delivery. |

| 5. Fee schedules should include instructions for preventive service frequency and payment allowances for children with a high risk of caries. |

| 6. Ensure that fee schedules and payment policies are aligned with periodicity schedules such that fee schedules/payment policies allow for payment of each covered service at the same ages as are specified in the periodicity schedule. |

Abbreviations: CHIP, Children’s Health Insurance Program; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; EPSDT, Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment.

aData source: CMS Informational Bulletin. 16

Given the presence of strong and consequential disparities in oral health that are evident across racial/ethnic groups of children, equivalent levels of dental services do not result in equivalent oral health outcomes. 34 For that reason, we additionally endorse a proposal by the Children’s Dental Health Project 35 to modify flexibility language in AAPD’s periodicity schedule so that dental care is individualized for all children at high risk of dental disease, not only for children with medical or developmental disabilities. In addition, we anticipate that payment for assessing caries risk (Current Dental Terminology codes D0601, D0602, and D0603 for low, moderate, and high caries risk, respectively) would encourage dental providers to tailor treatment plans and preventive service schedules on the basis of the individual needs of the child, promoting the delivery of less invasive and less costly care. 36 -38

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, a single evaluator determined the documents’ compliance with EPSDT requirements. The Medicaid provider portals varied considerably in their organization and the availability and accessibility of their provider documents. The analysis of dental provider documents was largely based on interpretation of language that was sometimes subjective in nature. Second, we did not consider the content of EPSDT manuals in addition to dental provider manuals, which may have also contained information on flexibility of services that are covered for children and adolescents. However, the decision to limit our analysis to the dental provider manual was intentional because we thought it was unlikely that a dentist would review a state’s EPSDT manual. Third, the dental provider documents may not be available on state websites when states have contractual relationships with managed-care and/or administrative services vendors and rely on these vendors to provide the required information. In states with these contractual relationships, the information of interest may have been described in the Medicaid managed-care contracts that were typically not readily accessible and were not reviewed. It remains the state’s responsibility to make information on covered services and fees readily accessible to consumers and providers. 20 Fourth, the CMS Information Bulletin also called upon states to ensure that age-based requirements were consistent between periodicity and fee schedules 16 ; however, our study was limited to a universal assessment for all children and adolescents who are Medicaid and CHIP eligible in the state. Fifth, it is unknown how dentists access, review, and understand state documents, although we assume that they are more likely to retrieve and review fee schedules than dental provider manuals or periodicity schedules. Lastly, because all documents are subject to revision, our 2018-2019 snapshot reflects only the status of these documents at that time.

Conclusions

Appropriate implementation of ESPDT standards for dental care by tailoring services to individual children’s needs would likely advance fundamental public health principles. These principles include (1) promoting preventive services over reparative care, (2) allocating services proportional to need, (3) addressing (oral) health disparities, (4) focusing on health determinants, and (5) attending to the needs of a population that has a particularly high risk for disease (eg, low-income children at high risk for dental caries). The implication of improving Medicaid administration by aligning dental guidance documents with EPSDT standards as outlined in the CMS Informational Bulletin is that more children would receive “the right care at the right time in the right setting” 1 to the benefit of their oral health across their life spans. The provision of personalized care would fulfill the original promise of EPSDT: to reduce or ameliorate disabilities through prevention and disease management early in life.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Laurie Norris, JD; Jane Perkins, JD, MPH; and Colin Reusch, MPA, for their comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Fosse as trainee and Dr. Edelstein as program director received support from the Postdoctoral Fellowship in Primary Care Dentistry Program, Section of Population Oral Health, College of Dental Medicine, Columbia University. This program was funded by grant #D88HP20109 from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by, HRSA, HHS, or the US government.

ORCID iD

Chelsea Fosse, DMD, MPH https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6355-2388

References

- 1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/early-and-periodic-screening-diagnostic-and-treatment/index.html

- 2. Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission . EPSDT in Medicaid. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.macpac.gov/subtopic/epsdt-in-medicaid

- 3. Rosenbaum S. When old is new: Medicaid’s EPSDT benefit at fifty, and the future of child health policy. Milbank Q. 2016;94(4):716-719. 10.1111/1468-0009.12224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. US Department of Health, Education & Welfare, President’s Task Force on Manpower Conservation . One-Third of a Nation: A Report on Young Men Found Unqualified for Military Service. University of Michigan Library; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Honey JR. The Army Selected Reserve Dental Readiness System: overview, assessment, and recommendations. Mil Med. 2013;178(6):607-618. 10.7205/MILMED-D-12-00445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee L., Dickens N., Mitchener T., Qureshi I., Cardin S., Simecek J. The burden of dental emergencies, oral-maxillofacial, and cranio-maxillofacial injuries in US military personnel. Mil Med. 2019;184(7-8):e247-e252. 10.1093/milmed/usz059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. US Department of Health and Human Services . Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Albino J., Dye BA., Ricks T. 2020 Surgeon General’s Report: Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fleming E., Afful J. Prevalence of total and untreated dental caries among youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2018;307:1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vujicic M., Buchmueller T., Klein R. Dental care presents the highest level of financial barriers, compared to other types of health care services. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(12):2176-2182. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Edelstein BL., Perkins J., Vargas CM. The Role of Law and Policy in Increasing the Use of the Oral Health Care System and Services. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 2020. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/OH_report_2020-07-13_508_0.pdf

- 12. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry . Guideline on caries-risk assessment and management for infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr Dent. 2013;35(5):E157-E164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry . Policy on medically-necessary care. Published 2019. https://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/P_MedicallyNecessaryCare.pdf

- 14. Rubin MS., Edelstein BL. Perspectives on evolving dental care payment and delivery models. J Am Dent Assoc. 2016;147(1):50-56. 10.1016/j.adaj.2015.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Riley W., Doherty M., Love K. A framework for oral health care value-based payment approaches. J Am Dent Assoc. 2019;150(3):178-185. 10.1016/j.adaj.2018.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hill T. Aligning dental payment policies and periodicity schedules in the Medicaid and CHIP programs. Informational Bulletin. May 4, 2018. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/cib050418.pdf

- 17.Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989, HR 3299, Pub L No 101-239 (1989).

- 18. DeMeester RH., Xu LJ., Nocon RS., Cook SC., Ducas AM., Chin MH. Solving disparities through payment and delivery system reform: a program to achieve health equity. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(6):1133-1139. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Clark MB., Slayton RL. Fluoride use in caries prevention in the primary care setting. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):626-633. 10.1542/peds.2014-1699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rosenbaum S., Wise PH. Crossing the Medicaid–private insurance divide: the case of EPSDT. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(2):382-393. 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry . Recommended dental periodicity schedule—chart. 2018. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.aapd.org/research/oral-health-policies-recommendations/periodicity-of-examination-preventive-dental-services-anticipatory-guidance-counseling-and-oral-treatment-for-infants-children-and-adolescents/periodicity-chart

- 22. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry . Periodicity of examination, preventive dental services, anticipatory guidance/counseling, and oral treatment for infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr Dent. 2017;39(6):188-196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johnson K., Kaye N., Cullen A., May J. Improving EPSDT periodicity schedules to promote healthy development. State Health Policy Briefing. Published 2009. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/10/ESPDT-Brf.pdf

- 24. American Dental Association . CDT 2018: Dental Procedure Codes. American Dental Association; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry . State dental periodicity schedules. https://www.aapd.org/research/policy-center/state-dental-periodicity-schedules

- 26. Schneider D., Crall JJ. EPSDT periodicity schedules and their relation to pediatric oral health standards in Head Start and Early Head Start. Published 2005. htts://www.aapd.org/assets/1/7/Periodicity-PeriodicityBrief.pdf

- 27. American Academy of Pediatrics . Recommendations for preventive pediatric health care. Published 2020. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://downloads.aap.org/AAP/PDF/periodicity_schedule.pdf

- 28. Oklahoma Health Care Authority . Recommendations for Pediatric Oral Health Care. Oklahoma Health Care Authority; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System . AHCCCS Dental Periodicity Schedule. Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Utah Department of Health, Division of Medicaid and Health Financing . Utah Medicaid Provider Manual: Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) Services. Utah Department of Health; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services . Dental Office Reference Manual. Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pennsylvania Department of Human Services . Pennsylvania Medical Assistance Program Dental Fee Schedule. Pennsylvania Department of Human Services; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maine Department of Health and Human Services . MaineCare Benefits Manual: Allowances for Dental Services. Maine Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shariff JA., Edelstein BL. Medicaid meets its equal access requirement for dental care, but oral health disparities remain. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(12):2259-2267. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Children’s Dental Health Project . Medicaid dental guidance to states: an opportunity to aim for equity. March 13, 2019. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.cdhp.org/resources/342-medicaid-dental-guidance-to-states-an-opportunity-to-aim-for-equity

- 36. Chaffee BW., Featherstone JDB., Zhan L. Pediatric caries risk assessment as a predictor of caries outcomes. Pediatr Dent. 2017;39(3):219-232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kutsch VK., Milicich G., Domb W., Anderson M., Zinman E. How to integrate CAMBRA into private practice. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35(11):778-785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yoon RK., Best JM. Advances in pediatric dentistry. Dent Clin North Am. 2011;55(3):419-432. 10.1016/j.cden.2011.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]