Abstract

Asthma and allergic disease result from interactions of environmental exposures and genetics. Vitamin E is one environmental factor that can modify development of allergy early in life and modify responses to allergen after allergen sensitization. Seemingly varied outcomes from vitamin E are consistent with the differential functions of the isoforms of vitamin E. Mechanistic studies demonstrate that the vitamin E isoforms α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol have opposite functions in regulation of allergic inflammation and development of allergic disease, with α-tocopherol having anti-inflammatory functions and γ-tocopherol having pro-inflammatory functions in allergy and asthma. Moreover, global differences in prevalence of asthma by country may be a result, at least in part, of differences in consumption of these two isoforms of tocopherols. It is critical in clinical and animal studies that measurements of the isoforms of tocopherols be determined in vehicles for the treatments, and in the plasma and/or tissues before and after intervention. As allergic inflammation is modifiable by tocopherol isoforms, differential regulation by tocopherol isoforms provide a foundation for development of interventions to improve lung function in disease and raise the possibility of early life dietary interventions to limit the development of lung disease.

Keywords: allergy, asthma, vitamin E, α-tocopherol, γ-tocopherol, human, animal models

Graphical Abstract

Increased Prevalence of Asthma/Allergy and Changes in the Consumption of forms of Vitamin E.

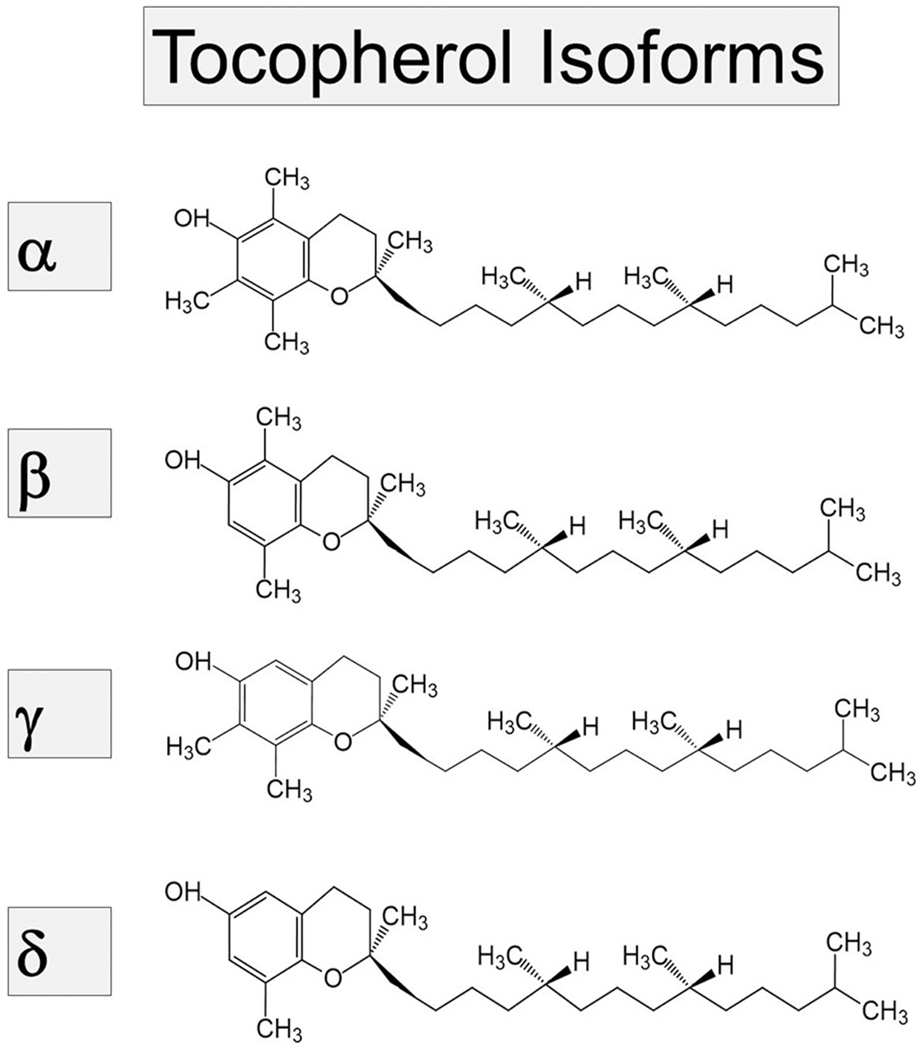

The World Health Organization reported a worldwide increase in asthma and allergies from 1950 to the present 1–4. In 2012–13, the United States Centers for Disease Control reported asthma and allergy prevalence as 10–20%, affecting about 26 million people, costing $56 million/year and 9 deaths/day 5–7. Non-allergic asthma, allergic asthma and allergy are overlapping disorders that result from complex interactions of environmental and genetic factors 8. Allergic and asthmatic clinical characteristics include bronchoconstriction, itch, pain, inflammation and tissue remodeling. In humans, analysis of lung function to monitor ssasthma include forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1, forced volume blown out in 1 second) and forced vital capacity (FVC, forced volume when all air is blown out). Therapies for asthma and allergies commonly include corticosteroids, which can have serious side effects. Therefore, it is critical to identify novel approaches for interventions. Allergic asthma inflammation initiation and perpetuation involves dendritic cell and T-helper type 2 (Th) cell responses 9 and the cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. Asthmatic and allergic inflammation is characterized by elevated allergen-specific IgE antibodies, degranulation of mast cells, and accumulation of eosinophils in the tissue 10. Recruitment of eosinophils into the tissue is a hallmark of allergic inflammation and allergic asthma 11–13. Mechanisms for recruitment of eosinophils from the blood, across the endothelium and into the tissue 14–16 involve signaling induced by adhesion molecules, chemokines, and cytokines 17, 18. This recruitment of eosinophils is differentially regulated by forms of vitamin E. The natural tocopherol isoforms of vitamin E are d-α-tocopherol, d-β-tocopherol, d-γ-tocopherol, and d-δ-tocopherol (Figure 1) and are synthesized by plants from tyrosine and chlorophyll 19. Although mammals do not synthesize vitamin E, mammals acquire vitamin E isoforms from food, cooking oils, and vitamin supplements. These tocopherol isoforms are not interconverted by mammals.

Fig. 1.

Natural d-tocopherol Isoforms. The most abundant tocopherols in plasma and tissues are α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol, which differ by one methyl group on the ring.

The rapid rise in rates of asthma, the differences in rates among countries and the changes in rates in migrating populations indicate a role of the environment, including the diet. During this timespan over which we have seen an increase in asthma and allergic disease, there has also been an increase in consumption of the γ-tocopherol isoform through the diet, infant formulas containing soybean oil that is rich in γ-tocopherol, and in vitamin supplements with γ-tocopherol 20, 21. The variation in global prevalence of asthma and allergies may be influenced, at least in part, by country-specific plasma γ-tocopherol concentrations as countries differ in types of cooking oils which contain no, low or high γ-tocopherol 22–32.

In reviewing reports on plasma tocopherol isoforms, countries with the highest plasma levels of γ-tocopherol tend to the highest prevalence rate of asthma 24, 26. However, the average plasma α-tocopherol concentrations among all countries are similar, likely because α-tocopherol is regulated by α-tocopherol transfer protein in the liver 24, 26. The differences in plasma γ-tocopherol levels in countries reflect, at least in part, differences in cooking oils preferentially used in the countries. In the United States, common cooking oils are soybean oil, corn oil and canola oil, all of which are high in γ-tocopherol per gram of oil (Table 1) 22–31. In contrast, most European countries regularly use sunflower oil, safflower oil, and olive oil that are relatively low in γ-tocopherol per gram of oil (Table 1) 24–26, 32. Consumption of cooking oils with γ-tocopherol increase plasma γ-tocopherol. For example, administration of soybean oil increases plasma γ-tocopherol levels 2–5 fold in humans and in hamsters 33, 34. A similar 5 fold increase in γ-tocopherol in mice enhances allergen-induced lung inflammation as well as a suppresses the anti-inflammatory functions of α-tocopherol 32.

Table 1.

Tocopherol Isoforms in Dietary Oils

| Tocopherol (mg / 100 g of oil) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oils | α-T | γ-T | δ-T | |

| Oils with low γ-T | Sunflower | 56.27±2.95* | 1.22±0.10 | 0.22±0.02 |

| Safflower | 49.33±6.88 | 3.85±0.45 | ND | |

| Olive | 6.13±0.61 | 0.08±0.004 | ND | |

| Grapeseed | 7.58±0.54 | 2.07±0.12 | 0.11±0.01 | |

| Oils with high γ-T | Soybean | 7.82±0.20 | 53.87±0.09 | 15.99±0.25 |

| Corn | 29.01±3.21 | 46.69±0.07 | 5.07±1.38 | |

| Canola | 16.45±0.19 | 21.92±0.05 | 0.13±0.01 | |

| Peanut | 14.41±0.19 | 9.66±0.27 | 0.80±0.23 | |

| Sesame | 77.68±6.07 | 75.41±4.82 | 56.27±0.45 | |

α-T, α-tocopherol; γ-T, γ-tocopherol; δ-T, δ-tocopherol.

mean ± standard deviation. ND, not detected. Adapted from 36

Tocopherol Isoforms and Allergy and Asthma in Adults

Often studies on vitamin E association with human diseases focus on one tocopherol isoform from food frequency questionnaires or plasma. Analysis of one isoform of tocopherol can lead to misinterpretations of outcomes because mechanistic studies have demonstrated opposing functions of γ-tocopherol and α-tocopherol in allergic inflammation 32, 35–39. Although methods for measurements of α-tocopherol, including HPLC and mass spectrometry, generate data for both isoforms from the same sample, historically studies have focused on reporting only the α-tocopherol without including data for γ-tocopherol. This likely occurred because α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol have nearly equal antioxidant function in vitro, but plasma α-tocopherol is at 5–10 fold higher concentrations than γ-tocopherol, because of the function of the liver α-tocopherol transfer protein. Nevertheless, recent studies have shed new light on functions of the tocopherol isoforms, indicating that these isoforms of tocopherols also have non-antioxidant functions that regulate allergic inflammation. Moreover, γ-tocopherol has a potent pro-inflammatory function that can block the benefit of α-tocopherol even when γ-tocopherol is present at 5 fold lower concentrations than α-tocopherol in vivo 21, 32, 35, 37–39. Taking this into consideration, new alternative interpretations can be applied to data from previous clinical studies that did not report γ-tocopherol concentrations. Also, unfortunately meta analysis of vitamin E and lung function have not taken into account the opposing functions of tocopherol isoforms 40. As would be expected, when data including multiple tocopherol isoforms that have opposite functions are combined, the resulting meta analysis indicate no association with lung function and wheeze 40. An alternative interpretation of the meta-analysis results 41 is not that vitamin E is not important for lung function but that the analysis used a combination of data from studies with marked variation of vitamin E isoforms that have ospposing functions and that were present in the diets, supplements, and supplement vehicles.

Subjects in clinical studies acquire multiple isoforms of tocopherols from diet, over-the-counter multi-vitamins and vehicles for tocopherol supplements. Although inconsistent outcomes have been reported for tocopherols in clinical studies of asthma and allergy, these differences in clinical outcomes may actually be more consistent than reported if other parameters are considered including regional diets, regional plasma tocopherol isoform concentration, multi-vitamin supplement use and isoforms administered in supplement vehicles 21, 36, 42. Because tocopherols are acquired by subjects from multiple sources, it is essential in clinical studies to determine the plasma or tissue concentration of tocopherol isoforms for adequate interpretation of study results. The tocopherol concentrations in plasma often correlate with tocopherol concentrations in the lung in humans and mice 32, 35, 43.

Outcomes for clinical studies of tocopherol and adult asthma differ among countries that consume different dietary oils (Table 2). The United States has high rates of asthma as compared to other countries and has an average plasma γ-tocopherol level that is 2 to 5 times higher than those of most European and Asian countries 24, 26. In Italy and Finland that preferentially use safflower oil or olive oil, supplementation of asthma patients with α-tocopherol reduced incidence of physician diagnosed asthma, reduced wheeze incidence and elevated lung function (FEV1) 44–48. In contrast, in the United States or the Netherlands where there is preferential consumption of soybean oil, corn oil and canola oil, α-tocopherol was not beneficial for adult asthmatic patients 44–48. This is consistent with opposing functions of γ-tocopherol because the United States and the Netherlands have high plasma levels of γ-tocopherol and high intake of soybean oil, containing high levels of γ-tocopherol (Table 1). However, in the United States, 16 weeks of consumption of acetate-conjugated α-tocopherol at a very high dose (1500 I.U. which is 1006 mg) by mild atopic asthmatics increased plasma α-tocopherol, decreased plasma γ-tocopherol, and improved airway responsiveness to methacholine challenge 49. In contrast to allergic asthma, a report of exercise-induced asthma in the United States demonstrated that three weeks of supplementation with α-tocopherol supplementation reduced the exercise-induced transient drop in lung function in humans 50.

Table 2.

Average Plasma Tocopherol Isoforms and Asthma Prevalence by Countries

| average plasma tocopherol | asthma prevalence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| country | γ-T (μM) | α-T (μM) | year (reference) | (2004) | (2012) |

| USA | 5 or 7 | 22 or 27 | 2001(review 36) | 10.9% | N.D. |

| Scotland | 1.9 or 2.0 | 24 or 27 | 2000(233),2011(234),1995(235) | 18.4% | ≥10% |

| Netherlands | 2.3 | 25 | 2007(review 36) | N.D. | 15.2% |

| Australia | 1.6 | 19 or 34 | 2003(236), 2009(237) | 14.7% | 21.5% |

| Ireland | 1.8 | 26 | 2001(review 36) | ≥10% | 9.2% |

| Japan | 1.7 or 2 | 23 | 2006, 2008(review 36) | 5.1–7.5% | N.D. |

| Sweden | 1.6 | 19.6 | 1999(238) | 5.1–7.5% | ≥10% |

| Finland | 0.5 or 1.8 | 24 or 41 | 2012(239), 2010(240) | 8.0% | 10.2% |

| France | 1.2 | 26 | 2001(review 36) | 6.8% | 10.6% |

| Italy | 1.2 | 24 | 2003(review 36) | 4.5% | 6.3% |

| Lithuania | 0.9 | 19 | 1999(238) | N.D. | 6.40% |

| Russia | N.D. | 23 | 2008(241) | 2.2% | 2.5% |

| China | 1.4 | 19 or 22 | 1998, 2003(review 36) | 2.1% | 1.4% |

Adapted from 36

As countries adopt Western-like lifestyles and diets, there is increased consumption of soybean oil 51 that would at least result in an increase in γ-tocopherol since vegetable oil (soybean oil) is rich in γ-tocopherol. In a review by Devereaux et al of increasing prevalence of asthma and changes in the environment in Scotland from 1967 to 2004, soybean vegetable oil intake in Scotland significantly increased 52. In England, dietary supplementation of asthmatics with α-tocopherol in soy oil vehicle had no impact on FEV1, asthma symptom scores or bronchodilator use 53. In another study in the United Kingdom, α-tocopherol administration in soybean oil to asthmatics also did not have benefit 54. An alternative interpretation of these two studies is that γ-tocopherol in soybean oil opposed the function of α-tocopherol. In several other clinical studies, α-tocopherol did not associate with asthma 55–57, but these studies did not measure tissue or plasma tocopherol isoforms or did not include analysis of potential opposing functions of γ-tocopherol. Regardless of the many racial, ethnic and environmental factors in different countries that may impact asthma prevalence 58, tocopherol isoforms and outcomes for asthma in clinical studies are consistent with the mechanistic studies demonstrating inhibitory functions of α-tocopherol and agonist functions of γ-tocopherol in allergic inflammation 32.

Opposing regulatory functions of tocopherol isoforms in adults are demonstrated in studies in Finland, the United States, China. In these studies, associations of tocopherol isoforms include analysis of clinical outcomes when the concentration of the opposing tocopherol isoform is low and causing the least competing opposing effects. Ratios of plasma α-tocopherol to γ-tocopherol is unsuitable for tocopherol analyses because the same ratio can be obtained with high α-tocopherol and high γ-tocopherol as for low α-tocopherol and low γ-tocopherol, despite these two situations being different clinically. In a study in Finland, lower serum α-tocopherol associated with increased self-reported asthma 59 whereas, the highest quartile of γ-tocopherol in early childhood (age 1–4) increased risk of developing asthma 60. In a study assessing risk for asthma in China, high plasma γ-tocopherol with low α-tocopherol had a 4 fold increase in odds ratio for onset of adult asthma in a 8 year study 61. In children in the INSPIRE birth cohort in China, higher maternal postpartum plasma α-tocopherol associated with lower wheezing and recurrent wheezing in children in the first 2 years of life, whereas high plasma γ-tocopherols reduced this effect of α-tocopherol 62. In a multicenter study of 4526 adults at age 21–55 years old in the United States, increasing serum levels of γ-tocopherol associated with lower FEV1 or FVC, whereas increasing serum levels of α-tocopherol associated with higher FEV1 or FVC 39. Moreover in this study, 5-fold higher human plasma γ-tocopherol (>10 μM γ-tocopherol) associated with reduced FEV1 and FVC in all participants (asthmatics and non-asthmatics) by age 21–27 years old, suggesting that tocopherol isoforms may regulate development and lung responses to environmental pollutants, allergens, or infections. Furthermore, for asthmatics with plasma γ-tocopherol at >10 μM, there was 350–570 mL lower FEV1 or FVC as compared to the low to moderate γ-tocopherol concentrations (<10 μM γ-tocopherol) at ages 21–27 39. This 350–570 ml decrease represents a 10 to 17% decrease in FEV1. This is substantial and of similar magnitude as the 5–10% reduction in FEV1 reported for other allergens and environmental factors. With occupational allergen exposure, there is a 5–8% decrease in FEV1 which is associated with dyspnea, chest tightness, chronic bronchitis, and chronic cough 63. For particulate matter, there is a 2 to 6% decrease in FEV1 64. Responders to cold or exercise have a 5 to 11% decrease in FEV1 65 and responders to house dust mite or dog/cat dander have a 2–8% decrease in FEV1 66. With a 2% prevalence of serum γ-tocopherol >10μM in adults in this 20 year prospective study and the adult U.S. population in the 2011 census, 4.5 million adults in the U.S. population may have had >10μM serum γ-tocopherol and have lower FEV1 and FVC.

Asthma and wheeze are also associated with respiratory infections. At least in studies of elderly (>65 yrs), α-tocopherol supplementation reduced incidence and duration of upper respiratory infections compared to placebo controls 67, boosted the ability of human neutrophils to kill the bacteria Streptococcus pneumonia and reduced human lung Streptococcus pneumonia infections 68, 69. The greatest benefit of α-tocopherol for Streptococcus pneumonia infections are reported for the elderly 70. Whether there is a benefit of α-tocopherol in limiting this viral infection in children and adolescents is not known. In Streptococcus pneumonia infections in mice, α-tocopherol reduces neutrophil recruitment and lethal septicemia 69. Also α-tocopherol supplementation reduces viral influenza titers in mice 71 and it is reported that dl-α-tocopherol-acetate reduces Diplococcus pneumoniae type I infection in mice 72. In humans, plasma γ-tocopherol levels were lower in hospitalized patients with covid-19 virus respiratory infections, although these patients also had a high proportion of overweight subjects and/or the pathologies of type 2 diabetes or arterial hypertension 73. Further studies are needed to determine if respiratory infections are modulated at α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol in children, a time when wheeze and asthma develop.

Multiples studies found that α-tocopherol levels are lower in adults and children with asthma 45, 46, 74–78. It is also reported that patients with asthma have reduced α-tocopherol and ascorbic acid in airway fluid but the average plasma concentration of α-tocopherol and ascorbic acid in these patients is normal 74, 75, despite reports in normal individuals that plasma and tissue tocopherols correlate 32, 35, 43. Therefore, because α-tocopherol levels are low in asthmatics and because higher α-tocopherol associates with better lung function, supplementation with natural α-tocopherol while maintaining low dietary levels of γ-tocopherol in combination with other treatments may limit development of or improve control of allergic disease/asthma. Potential target plasma tocopherol isoform levels in patients with during allergic disease/asthma may be about 1–1.4 μM plasma γ-tocopherol and 22–30 μM plasma α-tocopherol (Figure 2). These levels are based on average human plasma tocopherol isoforms from countries with lower prevalence of asthma 26 and low α-tocopherol in asthma patients 45, 46, 74–77. Additional intervention studies in adults and children with analysis of the tocopherol isoforms in plasma and tissues are necessary to assess tocopherol isoform regulation of allergic inflammation and asthma.

Fig. 2.

During lung development and allergic disease, a balance of levels of α-tocopherol (α–T) and γ-tocopherol (γ–T) are needed to limit disease. Proposed levels are indicated based on levels in countries with low asthma, but additional clinical and mechanistic preclinical studies are needed.

Early Life Tocopherol Isoform Levels and Development of Allergy and Asthma.

Prenatal and early life exposure to tocopherol isoforms are suggested to influence development of the lung and subsequently asthma. The development of allergies in offspring associate with maternal asthma, particularly for mothers with allergic disease prior to conception 79–87. Higher prevalence of early-onset persistent asthma occurs if the mother has uncontrolled asthma or moderate-to-severe controlled asthma as compared to mothers with mild controlled asthma 88. In studies of human maternal and paternal asthma and development of allergies in offspring, most associations are with maternal allergy or asthma 79–87, suggesting that sensitization can occur prenatally or early postnatally. Also, in utero and early exposures to environmental factors are critical for increased risk of allergic disease 89. Development of responsiveness to allergen in offspring is regulated by tocopherols acquired in the diet of allergic mothers and by the endogenous lipids β-glucosylceramides that are generated during maternal responses to allergen 90–92. Furthermore, there has been an increase in the d-γ-tocopherol isoform of vitamin E in the diet and in infant formulas that contain soybean oil 20, 21, 32, 93, 94. Thus, tocopherol isoforms that regulate allergy and asthma in mothers may affect the risk of development of allergy and asthma in offspring.

Multiple studies suggest that in human development, tocopherols may have early life regulatory functions on responsiveness to allergy or other environmental challenges to the lung. In the CARDIA cohort in the United States, by age 21, higher levels of plasma α-tocopherol associates with better lung spirometry and higher levels of plasma γ-tocopherol associates with worse lung spirometry 39, suggesting that tocopherols may have early life regulatory functions in the lung. In two Scottish cohorts, lower maternal intake of vitamin E (likely referring to α-tocopherol) was associated with increased asthma and wheezing in children up to 5 years old 52, 95. It has been demonstrated that maternal α-tocopherol dietary intake is inversely associated with cord blood mononuclear cell proliferative responses to allergen challenge in vitro 96, 97. Also, from ultrasound studies of the fetus, maternal α-tocopherol levels are reported to associate with fetal growth 98. In rats, maternal α-tocopherol supplementation during pregnancy results in larger lungs with normal structure in offspring 99. In studies with olive oil which contains α-tocopherol and low to undetectable levels of γ-tocopherol, administration of dietary olive oil to preterm infants starting 24 hrs after birth significantly increased infant plasma α-tocopherol 1.5 fold as compared to feeding with soybean oil 100; regrettably in this infant study, plasma concentrations of γ-tocopherol were not included. In premature infants, tocopherol isoforms have been reported to modify Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia that leads to development of asthma but, as has been discussed in a review that discusses that reports are complicated by incomplete understanding of the opposing functions of α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol and that further studies are needed 101. In another study, higher intake of vitamin E is associated with lower odds of wheeze in childhood, but in this analysis, the isoforms of vitamin E are not indicated 102. It is also reported that maternal α-tocopherol intake reported that α-tocopherol intake during pregnancy negatively associates with recurrent wheeze or any wheeze in children 2 years of age 103. In children age 6 to 14 years old in China, children with allergic rhinitis had lower levels of serum vitamin E (isoforms not indicated) and serum vitamin E negatively correlated with allergen-specific IgE and skin prick test 104. Increasing pregnancy levels of α-tocopherol in pregnant women negatively associates with neonate production of inflammatory mediators in vitro in endotoxin-stimulated nasal airway epithelial cells isolated from neonates shortly after birth 105. Also, in the United Kingdom, higher maternal plasma α-tocopherol at 11 weeks gestation (first trimester of pregnancy) associates with fewer asthma treatments in children 106 but γ-tocopherol was not reported. Also in a study in the United Kingdom, higher maternal plasma α-tocopherol at 10–12 weeks gestation (first trimester) associated with lower newborn airway epithelial cell constitutive release of TNFα, MIP1α, MIP1β and IL3 ex vivo 105. In contrast, in the second trimester in project VIVA in the United States, maternal α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol did not associate with wheeze in 7 year old children 107, suggesting that either very early exposure to α-tocopherol is necessary or that there are other environmental differences in the United Kingdom and the United States. However, in VIVA, 3 year old children with high α-tocopherol and low γ-tocopherol plasma levels had significantly better lung function (higher FEV1) at age 7 years than children with low α-tocopherol and high γ-tocopherol levels 107. Recently it has been reported that in 3 year old children, there is a positive association of γ-tocopherol levels with asthma and intestinal metabolites that play a role in development of asthma 108.

Tocopherol Doses in Humans versus Preclinical Mouse Studies

Tocopherol isoform regulation of asthma and allergic disease are studied in humans and animal models, however comparisons of dosages used between human and animal studies need adjustments for species differences. Tocopherol levels in the animal models need to reflect levels of tocopherols in disease and health. Direct dose comparisons per kilogram body weight for humans and mice are not sufficient because of large differences in rates of metabolism between them and thus there is a need to incorporate adjustments for body weight as well as differences in lipid metabolic rates.

Standard mouse basal diet contains about 45 mg α-tocopherol / kg of diet. The calculation for humans is translated as follows: (45 mg α-tocopherol/kg of diet) × (1 kg/1000 g) × (6 g diet eaten/mouse/day)/(28 g body weight for an adult mouse)] × 65000 g human adult = 627 mg α-tocopherol/ day for human adult. However, mouse metabolism is about 8 fold less efficient and mice have a higher metabolic turnover rate/ kg of body weight than humans 109, 110. Thus, mice require about 8 fold higher intake/g body weight. Furthermore, mice eat 1/6 their body weight in food/day 111 which is considerably more than the average amount of food/day for adult humans. Thus, to adjust for metabolic rate: (627 mg/day for adult human)/(8 for metabolic rate difference) = 78 mg α-tocopherol/day for human adults. For supplementation levels during disease, a 3 to 5 fold increase in α-tocopherol for supplementation of mice during studies of lung inflammation (150 or 250 mg α-T/kg of diet for mice) is then 235–392 mg α-tocopherol/day for human adults (calculation: 78 mg/day x (3 or 5)). The 235–392 mg α-tocopherol supplemental doses are well below upper limits suggested for human safety of 1,000 mg α-tocopherol /day in pregnancy. The supplemental level is near clinical levels in pre-eclampsia pregnancy trials of 268 mg (400IU) α-tocopherol 112–117. Also, a supplemented mouse diet with 150 or 250 mg α-tocopherol/kg of diet is reasonable in mice as it is 30–60 times lower than the rodent maternal α-tocopherol diet dose that reduces rodent hippocampus function 118. To achieve relevance for doses, the doses of 150 mg or 250 mg α-tocopherol/kg of diet for mice achieves a 2–3 fold increases in tissue concentrations of α-tocopherol, which is similar to fold tissue changes achievable in humans 21, 32, 35, 37, 38, 119. Thus, physiological, non-toxic doses of tocopherol isoforms for studies in mice are doses that achieve fold changes in mouse tissues similar to fold changes in human tissues.

For mice, the standard basal mouse chow diet contains about 45 mg α-tocopherol/kg of diet and 45 mg γ-tocopherol/kg of diet 90, 91. With equal levels of α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol in the diet, it results in a 10 fold higher tissue α-tocopherol concentration than γ-tocopherol concentration 90, 91 because of the preferential transfer of α-tocopherol by α-tocopherol transfer protein in the liver and because there is a higher rate of liver degradation of γ-tocopherol into its metabolites for excretion 120, 121.

Of important consideration is that the recommended daily allowance of α-tocopherol is 15 mg/day is for healthy adult humans. However, during asthma the levels of tocopherol isoforms are decreased in tissues in humans and mice. Recommended daily doses of tocopherol isoforms during diseases are not known and recommended daily doses of γ-tocopherol have not been addressed. It is critical to include doses with functional effects for the tocopherol isoforms. This is especially relevant to studies in humans with mixed tocopherol isoforms. It is important to be aware that the α-tocopherol isoform is preferentially transferred in the liver but nevertheless, γ-tocopherol is potent even at 10-fold lower levels than α-tocopherol in tissues such that γ-tocopherol can ablate the benefit of α-tocopherol in allergic responses. Moreover, in humans and mice, a basal rather than deficient α-tocopherol dose is relevant as a baseline, especially in studies of development because α-tocopherol is necessary for mouse and human placental development 122, 123.

Regulatory functions of tocopherol isoforms in preclinical mouse studies.

The vitamin E isoforms α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol exhibit opposite regulatory functions in allergic inflammation and airway hyper-responsiveness. As in human studies, in reports with preclinical animal studies, ingestion of tocopherol isoforms differs with regards to doses in supplementation and tocopherol isoforms present in the oil vehicles used for supplementation. Also purity of the α-tocopherol supplement is often not indicated and tissue levels of tocopherol isoforms are not reported. In a report with administration of purified α-tocopherol in soy oil by gavage, there were no major effects on immune parameters or lung airway responsiveness in mice challenged with OVA 124, but tissue levels of tocopherol isoforms were not reported. Since soy oil was used, an alternative interpretation is that high γ-tocopherol in the soy oil vehicle opposed the influence of α-tocopherol. Oral administration of vitamin E (isoform and purity not indicated) reduced Th2 cytokines, IgE, serum histamine in an OVA model of allergic rhinitis 125. In another study of allergic rhinitis, oral gavage with α-tocopherol before each OVA lung challenge reduced numbers of eosinophils and mast cells as well as levels of phospho-protein kinase B levels in isolated mast cells 126. In another report, feeding mice α-tocopherol (purity not indicated) starting 2 weeks before OVA sensitization did not alter IgE levels, but reduced the number of broncho-alveolar lavage eosinophils 127. In a study with mixed tocopherol isoforms, dosing of mild asthmatics for 24 hrs reduced lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulated peripheral blood cells production of IL1 and IL1β ex vivo128 and reduced ex vivo basophil activation by house dust mite ex vivo 129. In a report by Mabalirajan et al. 130, oral administration of α-tocopherol in ethanol after antigen sensitization blocked OVA-induced lung inflammation, airway hyper-responsiveness and mediators of inflammation including IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, OVA-specific IgE, eotaxin, TGFβ, 12/15-LOX, lipid peroxidation, and lung nitric oxide metabolites 131. In summary, α-tocopherol supplementation without γ-tocopherol supplementation reduced allergic inflammation.

As in clinical studies, α-tocopherol supplementation and γ-tocopherol supplementation have opposing effects on allergic inflammation in preclinical studies. In mice, mouse diet supplemented with 250 mg α-tocopherol/kg of diet during house dust mite challenges reduces eosinophilia in the lung and reduces lung levels of reactive oxygen species 61, 132. In contrast, γ-tocopherol (250 mg/kg of diet) elevated house dust mite-induced eosinophilia in the lung 61. In another mouse model, tocopherols were administered after allergen sensitization, but before airway allergen challenge, to demonstrate tocopherol regulation of established allergy because patients are already sensitized. In this model, mice received tocopherols by daily subcutaneous injections after allergen sensitization (chicken egg ovalbumin, OVA, in adjuvant) but before allergen challenge 32. The subcutaneous administration of tocopherols or diet administration of tocopherols results in the same route of tocopherols through the body since the tocopherols enter the lymph, then the thoracic duct and then the liver where the tocopherols are loaded on lipoproteins that then enter circulation. A plateau in tissue levels of tocopherols are achieved in only a few days after subcutaneous administration of tocopherols, whereas it takes a couple of weeks to achieve tissue plateau levels when tocopherol is administered in the diet 33, 133. Lung inflammation in mice was altered by subcutaneous administration of α-tocopherol or γ-tocopherol that yielded a 4–5 fold increase in plasma and lung α-tocopherol or γ-tocopherol, a clinically relevant fold change achievable in humans; this was without affecting body or lung weight 32. In this study, subcutaneous administration of γ-tocopherol elevated lung eosinophil 175%, and subcutaneous administration of α-tocopherol reduced lung eosinophil recruitment by 65% 32. Also airway hyper-responsiveness was reduced by α-tocopherol and elevated by γ-tocopherol 32. Tocopherols did not alter numbers of eosinophils in the blood, vascular adhesion molecules, cytokines or chemokines that are required for eosinophil recruitment, indicating that there were sufficient numbers of eosinophils available for recruitment 32. This regulation of eosinophil recruitment, without alteration of adhesion molecules, cytokines or chemokines, is similar to other reports demonstrating a role for tocopherols in regulation of intracellular signals in endothelial cells during leukocyte recruitment 134–136.

When α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol are administered at the same time, γ-tocopherol opposes the anti-inflammatory benefit of α-tocopherol, such that supplementation of α-tocopherol plus γ-tocopherol during challenge with OVA does not alter the level of numbers of lung eosinophils and airway responses are similar to that of the allergic mice with the vehicle control 32, 35. This suggests that α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol have competing opposing functions and that γ-tocopherol is very potent because it opposed effects of α-tocopherol even at 5–10 times lower plasma concentrations than α-tocopherol. These mouse studies with a 5-fold increase in tocopherol levels 21, 32, 35, 37, 38 are consistent with the clinical studies 39, demonstrating that a 5-fold increase in human plasma γ-tocopherol associates with a reduction in lung function in adult humans. To relate this to prevalence of disease, a 5-fold difference in plasma γ-tocopherol concentrations is consistent with 5-fold higher γ-tocopherol in Americans versus most Western Europeans and Asians and higher prevalence of asthma in Americans (Table 2)24, 26.

The allergen enhancing effects of γ-tocopherol in mice can be partially reversed by switching supplements from γ-tocopherol to α-tocopherol at the models dose of α-tocopherol for 4 weeks 35. To fully reverse effects of γ-tocopherol in 4 weeks, it required 10 fold higher supplemental levels of α-tocopherol 35 but a very high supra-physiological level of α-tocopherol may be potentially risky in humans because at very high levels of α-tocopherol, there is potential for increase the incidence of hemorrhagic stroke and elevate blood pressure 137–139. It is not known whether allergen-enhancing effects of γ-tocopherol can be fully reversed by a longer supplementation with modest levels of α-tocopherol supplementation.

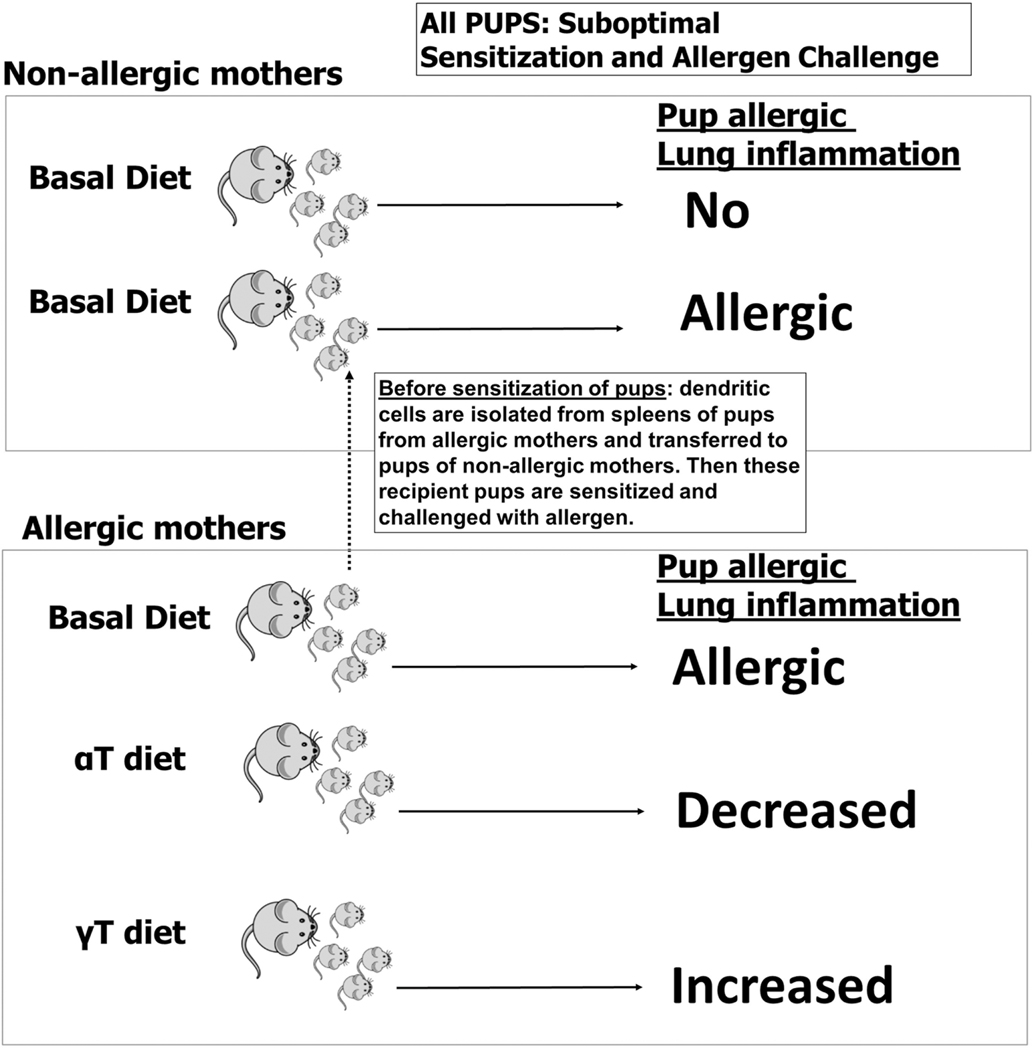

Maternal Tocopherol and Offspring Development of Allergy

In pregnant mice, α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol supplementation of allergic mothers decreases and increases, respectively, the risk of development of allergies in the offspring 90, 91. In description of this model, adult female mice are sensitized by intraperitoneal injection of OVA with the adjuvant alum on week 1 and 2, challenging with inhaled OVA on weeks 4, 8 and 12 and then mating on the last day of allergen challenge 79, 140–148. The OVA challenge just prior to mating is required for the offspring responsiveness (unpublished observations) and an additional OVA challenge during mouse pregnancy does not elevate allergen responses in the offspring 140, likely because allergic lung inflammation takes 2 weeks to resolve and mouse gestation is 3 week. After birth, all of the offspring from allergic mothers and non-allergic mothers are treated with a suboptimal OVA protocol, comprised of neonates receiving only one instead of two OVA/alum treatments at postnatal day 3–5 and then starting 7 days later, the neonates are challenged with aerosolized OVA for three consecutive days 70, 129–137. The offspring from allergic mothers develop allergic lung inflammation and airway responsiveness, whereas pups from non-allergic mothers do not develop allergic inflammation (Figure 3) and this responsiveness is sustained into adulthood (8+ weeks of age) in mice 142.

Fig. 3.

Maternal α-Tocopherol (α-T) and γ-Tocopherol (γ-T) Supplemented Diets Regulate Development of Allergic Lung Inflammation in Offspring of Allergic Mothers. 90–92.

The response of the offspring is blocked if mothers receive at pre-conception anti-IL-4 blocking antibodies 140 or depletion of T cells 144. However, the response of offspring is enhanced if mothers become allergen responsive by adoptive transfer of allergen-specific T cells from OVA TCR transgeneic mice DO11.10 mice to females prior to mating 145. During pregnancy, Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13) and IgE which are elevated in the mother do not pass to the fetus 149–154. Moreover, although allergens can sometimes perhaps cross the placenta, offspring are able to respond to β-lactoglobulin or casein when mothers were sensitized and challenged with OVA 140, 151. An antigen-independent effect of maternal allergy on offspring allergen responsiveness also occurs in canines 155 and in humans 70.

The antigen-independent effect of maternal allergy on offspring allergen responsiveness is a result of changes in dendritic cells (not macrophages) in the fetus and neonate (Figure 3)90–92, 141. The fetal liver and the neonatal lung has increased numbers of specific subsets of dendritic cells (DCs) with the phenotype of resident DCs (rDCS), monocyte-derived DCs (mDCs) and alveolar DCs 90–92. In contrast, there are no changes in CD11b- regulatory dendritic cell subsets, including plasmacytoid dendritic cells and CD103+ dendritic cells 91. Furthermore, before antigen challenge of the pups, the dendritic cells of pups from allergic mothers had little transcriptional changes but extensive DNA methylation changes, but after allergen challenge, transcriptional changes occurred in DCs of pups of allergic mothers as compared to pups of non-allergic mothers 156. The DCs also have increased responses 141, 157, 158. In demonstration of function in vivo, transfer of splenic dendritic cells from non-challenged neonates of allergic mothers into neonatal mice from non-allergic mothers results in increased allergic responsiveness in recipients (Figure 3) 141. A maternal effect on offspring allergic responses has also been demonstrated for maternal exposure to environmental irritants, including maternal inhalation of titanium oxide or diesel exhaust particles 159 and skin exposure to toluene diisocyanate 160. In contrast, offspring are protected from development of asthma by prenatal challenge of the mother with LPS, a TLR4 agonist and Th1 stimulant 161–164 or exposure of allergic mothers on postnatal day 4 with CpG oligonucleotides, a TLR9 agonist and Th1-type stimulant 165.

Endogenous transplacental maternal mediators in allergic mice have been suggested to contribute to the increased responsiveness in the offspring to suboptimal OVA challenge. Cortisol in allergic pregnant BALB/c mice is reported to enhance offspring responsivess to allergen 166, 167. In pregnant asthmatic women without treatment for asthma, a deficiency in the placenta of a cortisol metabolizing enzyme 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 leads to increased fetal cortisol and low birth weight which is predictive of lower lung function later in life 168, 169. In adult mice and rats, OVA sensitization and challenge increases stress 170–175 and endogenous serum corticosterone 176, 177 and stress/anxiety symptoms are commonly associated with allergy/asthma in adult mice and in humans 178–182. Maternal corticosterone can cross the placenta, can affect fetal cortisol levels 167, 183 to induce Th2 responses 184, 185 and cortisol is also present in human breast milk 186. However, the studies with maternal corticosterone were done with BALB/c mice and in our hands with C57BL/6 mice, administration of corticosterone does not enhance offspring response to allergen (unpublished observations), even though offspring of allergic C57BL/6 mice consistently exhibit responsiveness to allergen 90, 91. This suggests that there are mouse strain specific effects of corticosterone.

In C57BL/6 mice, allergic mothers synthesize a lipid, β-glucosylceramide that was both necessary and sufficient for enhanced responsiveness of offspring to allergen in the lung 92 and in a manuscript in revision, we demonstrated an association of cord blood β-glucosylceramide with wheeze in the first year of life. Moreover, tocopherol isoforms and β-glucosylceramide in utero and in breast milk may both influence responsiveness to allergen by neonates. Briefly, pups from allergic mothers that are nursed by non-allergic mothers still have an allergic response to suboptimal challenge with OVA 150. Therefore, maternal effects in utero mediate development of allergen responsiveness in offspring of allergic mothers 150. However, breast milk is sufficient, but not necessary, for maternal transmission of asthma risk in the offspring because when pups from non-allergic mothers are nursed by allergic mothers, the pups exhibit a response to suboptimal allergen challenge 150. In contrast, allergen in breastmilk of non-allergic mothers may confer protection of offspring by oral induction of tolerance to the allergen in breastmilk 187, 188. Understanding mechanisms of maternal transfer of risk for allergy to offspring and mechanisms for tocopherol isoform regulation of this risk will have impact on limiting the development of allergic disease early in life.

Tocopherol supplementation of allergic mothers modifies pup responsiveness to allergen (Figure 3). Supplementation of allergic mothers with α-tocopherol (250 mg α-tocopherol/kg diet) during pregnancy and nursing inhibits OVA-induced offspring lung eosinophilia and immune mediators of Th2 inflammation (IL-4, IL-33, & TSLP and the chemokines CCL11 & CCL24)allergen responsiveness in offspring in the OVA model 91, indicating that the transfer of responsiveness to allergen to offspring of allergic mothers is modifiable. Furthermore, during a second pregnancy, if mothers receive α-tocopherol supplementation, then there is also inhibition of offspring development of allergic responses 91. Maternal α-tocopherol supplementation did not affect pup low levels of the Th1 cytokine IFNγ or the regulatory cytokine IL-10 91, indicating that α-tocopherol does not switch the response to OVA to a Th1 response.

The effect of maternal α-tocopherol supplementation is regulatory in utero and in the breastmilk as demonstrated by cross-fostering pups at birth. Cross-fostering pups from allergic mothers with 250 mg α-tocopherol/kg diet to allergic mothers with basal diet (45 mg α-tocopherol/kg diet) indicated that α-tocopherol supplementation of the allergic mother during fetal development was sufficient to inhibit neonate responsiveness to allergen 91. In addition, α-tocopherol supplementation during lactation reduces the allergic responses in the neonates 91, suggesting that there is also a contribution of α-tocopherol after birth 91. In contrast to the inhibitory effect of α-tocopherol, γ-tocopherol supplementation (250 mg α-tocopherol/kg diet) during pregnancy and nursing elevates the offspring responsiveness to allergen in the OVA model 90. The γ-tocopherol does not induce allergic inflammation in the OVA-challenged pups from non-allergic mothers 90, indicating that endogenous maternal factors of allergic mothers are required for offspring inflammation.

In these maternal mouse studies, control mothers received a basal α-tocopherol diet (45 mg α-tocopherol/kg diet) 91 because a basal α-tocopherol diet is required for placental development and thus the fetus 122, 123. Also, α-tocopherol transfer protein is expressed by trophoblasts, fetal endothelium and amnion epithelium of the placenta, consistent with the critical role for α-tocopherol in placenta development 122, 123. Pup weight and sex distribution was not altered by α-tocopherol supplementation or OVA treatments 91. Disturbing and of potential relevance in humans, maternal γ-tocopherol supplementation decreased the proportion of female mice that had pups, but for the females that had pups, there is no affect numbers of pups per litter or pup body weight. It is not known whether γ-tocopherol influences placentation, placental development of fetal development. The data from maternal supplementation with γ-tocopherol have potential important implications for children of allergic mothers when supplemental levels of γ-tocopherol are present in the maternal diet, prenatal vitamins, parental nutrients, or infant formulas.

The α-tocopherol supplemented diet increases liver α-tocopherol in the non-allergic mothers 3 fold and pup liver α-tocopherol 2.5 fold compared to basal diet controls 91, which is consistent with previous reports for this diet in adult female mice 32, 35. However, with α-tocopherol diet supplementation of allergic mothers, the tissue concentrations of these allergic mothers are lower than non-allergic mothers, which is consistent with reduced α-tocopherol levels in human asthmatics 74–76, 189. Maternal diets supplemented with 250 mg γ-tocopherol/kg diet during pregnancy/lactation increases the maternal liver γ-tocopherol level two-fold and the pup liver γ-tocopherol 5-fold, consistent with the fold tocopherol changes in human and mouse tissues after supplementation 21, 32, 35, 37, 38, 119. In summary, supplementation of allergic mothers with α-tocopherol inhibits and γ-tocopherol elevates offspring responsiveness to allergen. Future studies are needed to determine adequate α-tocopherol levels for individuals with disease in non-pregnant and pregnant women, especially since prenatal vitamins often contain multiple tocopherol isoforms.

Tocopherol supplementation of allergic mothers modifies offspring development of dendritic cells. The fetal liver and allergen-challenged lung of offspring of allergic mothers have increased numbers of subsets of DCs 90, 91. Maternal supplementation with α-tocopherol reduces the fetal liver and allergen-stimulated pup lung numbers of CD11b+ subsets of CD11c+ dendritic cells, including rDCs, mDCs, and CD11b+ alveolar dendritic cells, without altering CD11b- subsets of CD11c+ dendritic cells, including plasmacytoid dendritic cells, CD103+ dendritic cells, CD11b- alveolar dendritic cells, and alveolar macrophages 91. Of critical importance, α-tocopherol supplementation does not completely deplete CD11b+ dendritic cells but instead, α-tocopherol supplementation of allergic mothers reduces the numbers of pup CD11b+ dendritic cells down to the numbers of these dendritic cells in pups from non-allergic mothers 91. This suggests that α-tocopherol does not block the baseline dendritic cell hematopoiesis but instead may block the signals from allergic mothers that specifically induce the increase in differentiation of CD11c+CD11b+ dendritic cell subsets in offspring. In contrast to α-tocopherol supplementation, γ-tocopherol supplementation of allergic mothers increases fetal liver and pup development of these CD11c+CD11b+ dendritic cells, including lung IRF4+CD11c+CD11b+ dendritic cell subsets, but does not alter numbers of offspring regulatory CD11b- dendritic cell subsets 90. For the fetal liver and pup lung, there are no effects of d-α-tocopherol or d-γ-tocopherol on the level of expression per dendritic cell of the costimulatory molecules MHCII, CD80 or IRF4 90.

It has been demonstrated that the tocopherol isoforms directly regulate bone marrow hematopoiesis in vitro. α-tocopherol supplementation during 8 day cultures of GM-CSF-stimulated bone marrow cells reduces the generation of rDCs and mDCs without affecting the percent of viable cells in the culture 91. Also, γ-tocopherol directly regulates development of bone marrow-derived DCs in vitro 90. In vivo, maternal d-γ-tocopherol supplementation increased the cytokines GM-CSF and activing A in pup lungs from allergic mothers 90. GM-CSF induces bone marrow differentiation, Activin A regulates allergic inflammation 190 and both cytokines induce differentiation of monocytes to mDCs and recruitment of DCs 191. γ-tocopherol also increases the chemokine CCL11 in pups from allergic and non-allergic mothers and it increases the chemokine CCL24, and the cytokine IL-5 in the pups from non-allergic mothers 90. OVA-challenge in pups from allergic mothers with d-γ-tocopherol does not result in further increases in CCL24 or IL-5 90, which may indicate that a maximum response was achieved with OVA challenge. Thus these signals may function to amplify recruitment of eosinophils in pups from γ-tocopherol supplemented allergic mothers.

In summary, supplementation of allergic mothers with γ-tocopherol increases and α-tocopherol decreases generation of CD11c+CD11b+ DCs and numbers of eosinophils in allergen-challenged pup lungs. Studies of tocopherol isoform-specific regulation of inflammation provide a basis towards designing drugs, supplements and diets that more effectively modulate these pathways in allergic disease. The function of tocopherol isoforms on allergic inflammation and asthma have implications for tocopherol isoforms in prenatal vitamins, infant formula, and in the diet which may impact risk for allergic disease in future generations. More studies are needed in humans to examine short term versus long term outcomes of tocopherol isoforms.

Tocopherol Isoform Mechanisms of Regulation of Allergy and Asthma: Adults and Maternal Supplementation

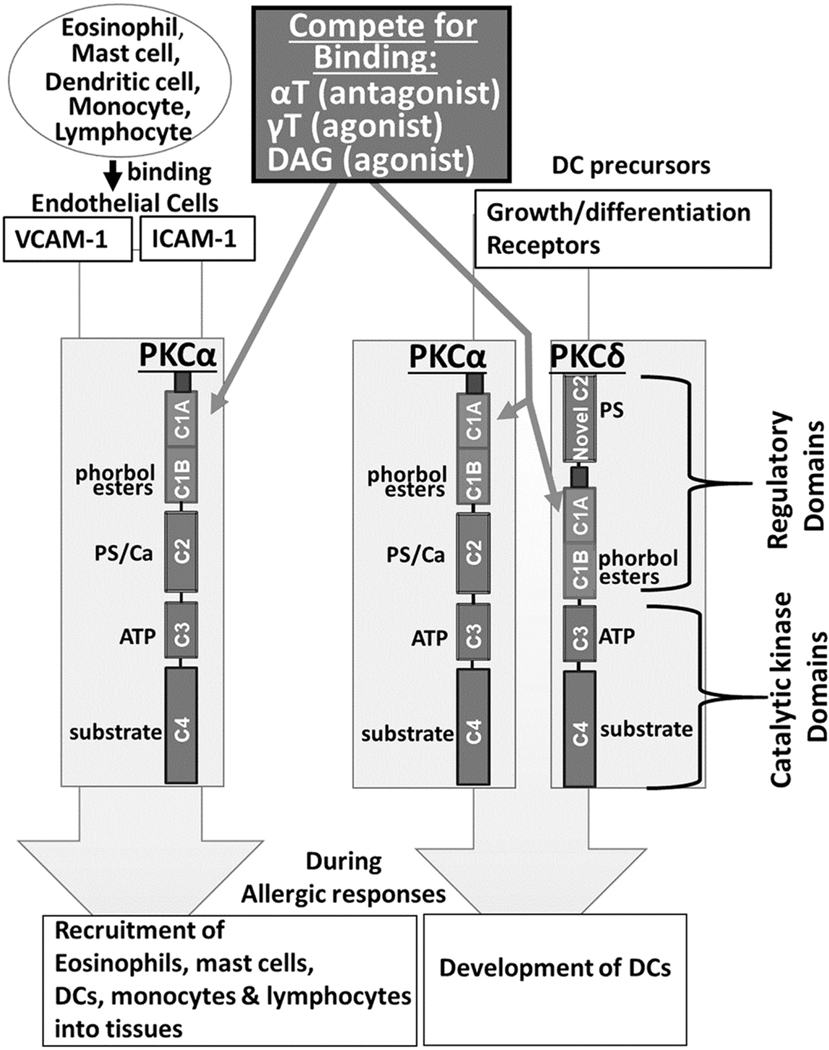

Mechanistically, tocopherol isoforms modify eosinophils, dendritic cells, lymphocytes and mast cells 32, 37, 192migration on VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 during allergic inflammation in the lung 12, 13,31, 36, 200 and modify development of DCs in the fetal liver of allergic mothers 90, 91 (Figure 4). VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 signaling activates protein kinase Cα (PKCα) in endothelial cells and this is necessary for eosinophil recruitment 193. Also, dendritic cell development and activation are regulated by PKCα 194–201, PKCβ202–211 and PKCδ 212–214, all of which contain the C1A regulatory domain (Figure 4). The C1A regulatory domain binds both α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol38 and this tocopherol binding regulates the activation of PKCα 38. Most notably, upon binding to PKCα, α-tocopherol is an antagonist of PKCα and γ-tocopherol is an agonist cofactor of PKCα activation38 (Figure 4). Thus, γ-tocopherol does not activate PKC but strongly enhancing signals that activate PKC. In summary, a mechanism for the opposing regulatory functions for α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol on allergic inflammation in adult mice and in fetal development of DCs in allergic mothers is, at least in part, a result of tocopherol regulation of PKC. Thus, tocopherol isoforms have non-anti-oxidant regulatory functions during allergic inflammation.

Fig. 4.

Model of α-tocopherol (αT) and γ-tocopherol (γT) regulation of PKC activation during allergic responses. α-T, γT and diacylglycerol compete for binding to the C1A regulatory domain of PKCs. α-T is an antagonist, but γT and diacylglycerol are agonists at the C1A domain during activa-tion of PKCs. PKCα mediates VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 signaling in endothelial cells during leukocyte recruitment in allergic responses. PKCα and PKCδ mediate signals for development of dendritic cells during allergic responses.

In addition to direct effects of tocopherol binding to PKC, the α-tocopherol metabolite α-tocopherol-13’-COOH, generated in the liver, can accumulate in leukocytes and inhibit 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO) activity 215. 5-LO is expressed by leukocytes and Intraperitoneal administration of high levels of α-tocopherol-13’-COOH during OVA/alum sensitization blocks development of bronchial hyper-reactivity in mice, but levels of lung leukocytes, anti-OVA IgE and cytokines that regulate allergic inflammation were not reported 215. The effects of endogenous levels of α-tocopherol-13’-COOH during allergic inflammation is not known. Also tocopherols are metabolized to 2′-carboxyethyl-6- hydroxychroman (CEHC), which are reported to have anti-oxidant functions 216. Further studies of endogenous generation of tocopherol metabolites and their effects on allergic inflammation and asthma are needed.

Tocopherol isoforms on lipid particles and in cells have also have anti-oxidant functions. Tocopherols on plasma lipid particles are transferred to cells by plasma phospholipid transfer protein, scavenger receptors or the lipoprotein lipase pathway. In cells, tocopherols, which are lipids, are located in cell membranes and associated with lipophilic domains of proteins. The anti-oxidant activity of α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol, at equal molar concentrations, are relatively similar with regards to scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) during lipid peroxidation 217, 218. Because α-tocopherol is at 10 fold higher concentrations in tissues than γ-tocopherol, α-tocopherol has 10 fold more capacity for scavenging of ROS in vivo. However, of significance in data interpretations is that γ-tocopherol at 5 fold lower concentrations than α-tocopherol is capable of blocking the anti-inflammatory function of α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol has higher binding avidity for the C1A domain of PKC 38. Thus the outcome effects of the tocopherol isoforms on allergic inflammation is mediated by the combination of levels of the tocopherol isoforms and the tocopherol potency for non-anti-oxidant and anti-oxidant functions.

Another functional difference between α-tocopherol and γ-tocopherol is that γ-tocopherol, but not α-tocopherol, scavenges reactive nitrogen species (RNS) with peroxynitrite forming 5-nitro-γ-tocopherol 219. Although α-tocopherol reduces allergic eosinophilic inflammation, γ-tocopherol scavenging of RNS may be beneficial by short term administration for acute inflammation in lungs with increased RNS, such as neutrophil inflammation induced by ozone or endotoxin 220. However, ozone effects on inflammation in asthmatics were not reduced by a 2 day course of four oral supplementation of γ-tocopherol 221 but in a mouse model with ozone exposure with the allergen chicken egg ovalbumin (OVA), α-tocopherol reduced allergic lung inflammation 222. In sheep with burn or smoke inhalation injury, nebulized γ-tocopherol reduces neutrophilia, IL-8 and IL-6 223. In other studies, supplementation with mixed tocopherol isoforms containing γ-tocopherol blocks acute endotoxin-stimulated or ozone-stimulated neutrophil inflammation in the rat and human lung 216, 224–226. In addition to γ-tocopherol, acute administration of α-tocopherol to mice at the time of ozone /OVA challenge blocked ozone-induced exacerbation of OVA-stimulated lung neutrophil and eosinophil inflammation 227. It is reported that γ-tocopherol supplementation reduces antigen induction of rat lung inflammation in which there was several fold more neutrophils than eosinophils 228. In asthmatic children exposed to ozone, vitamin E (isoforms not reported) and vitamin C supplementation reduced IL-6 in nasal lavages 137. Therefore, during acute neutrophilic inflammation, γ-tocopherol may be of benefit. In contrast to reports of γ-tocopherol benefits in acute inflammation or neutrophilic inflammation, it is reported that plasma γ-tocopherol associates with lower lung function in humans 39 and with increased lung eosinophilia and airway hyper-responsiveness in mouse models of allergic asthma 39. Therefore, chronic consumption of γ-tocopherol may be unfavorable during lung development or during chronic inflammatory diseases such as allergies and asthma. Although this review is focused on tocopherols, another form of vitamin E γ-tocotrienol given at pharmacological levels to mice has been reported to reduce allergy to house dust mites 229. Also addition of high levels of γ-tocotrienol in vitro reduces human airway smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration 230. Further clinical studies of tocopherol isoform regulation of allergic lung inflammation and development of allergy are needed.

CONCLUSION.

The rapid increase in rates of asthma implies that the environment influences the generation of asthma and allergic inflammation. Therefore, changes in diet and/or lifestyle could modify disease. There are differences in results of clinical studies with tocopherol isoforms, but these are consistent with the mechanistic studies of functions of tocopherol isoforms in animal models of allergic inflammation and in cell cultures with physiological doses of the tocopherol isoforms. The α-tocopherol isoform functions as an anti-inflammatory, whereas γ-tocopherol is a potent pro-inflammatory isoform by, at least, through functioning as an antagonist and agonist, respectively, of regulatory domains of cell signaling molecules. Defining the differential regulatory functions of isoforms in inflammation provides a basis towards designing interventions that more effectively modulate inflammation and improve lung function in disease in adults and during development. Studies in humans and preclinical models need to include measurements of tocopherol isoforms in the supplements, vehicles for the supplements, and most importantly, the plasma and/or tissues before and after intervention, as this is necessary for adequate interpretation of study outcomes. Further studies are necessary to provide a basis for recommendations for doses of tocopherol isoforms in inflammatory disease states in females and males as well as ethnic groups that differ in prevalence of asthma 231, 232. As allergic disease is modifiable, at least in part, by tocopherol isoforms, studies are needed for dietary manipulation and supplementation in allergic pregnant mothers and children with asthma to define interventions in diet early in life that may limit development of allergic disease.

Highlights.

Increased prevalence of asthma/allergy and altered consumption of tocopherol isoforms

α-tocopherol associates with better lung function but this is reduced by γ-tocopherol

In mice, tocopherol isoforms regulate allergy in adults and their offspring

α- and γ-tocopherol inhibit and enhance, respectively, protein kinase C activation

Needed are studies ssfor a basis to recommend daily tocopherol isoform doses in disease

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01AI127695, R01AI127695-S and R01AI127695-05S1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bousquet J, Bousquet PJ, Godard P, Daures JP, The public health implications of asthma. Bull World Health Organ 83, 548–554 (2005). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vollmer WM, Osborne ML, Buist AS, 20-year trends in the prevalence of asthma and chronic airflow obstruction in an HMO. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 157, 1079–1084 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friebele E, The attack of asthma. Environ Health Perspect 104, 22–25 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Schayck CP, Smit HA, The prevalence of asthma in children: a reversing trend. Eur Respir J 26, 647–650 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC National Asthma Control Program http://www.cdc.gov/asthma/impacts_nation/asthmafactsheet.pdf. 2012.

- 6.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Bailey C, Zahran HS, King M, Johnson CA, Liu X, Trends in asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality in the United States, 20012010. NCHS Data Brief, 1–8 (2012). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Center For Disease Control Report http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db121.pdf. (2013).

- 8.Martinez FD, Genes, environments, development and asthma: a reappraisal. Eur Respir J 29, 179–184 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palli D, Masala G, Vineis P, Garte S, Saieva C, Krogh V, Panico S, Tumino R, Munnia A, Riboli E, Peluso M, Biomarkers of dietary intake of micronutrients modulate DNA adduct levels in healthy adults. Carcinogenesis 24, 739–746 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiscus LC, Van Herpen J, Steeber DA, Tedder TF, Tang ML, L-Selectin is required for the development of airway hyperresponsiveness but not airway inflammation in a murine model of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 107, 1019–1024 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hakugawa J, Bae SJ, Tanaka Y, Katayama I, The inhibitory effect of anti-adhesion molecule antibodies on eosinophil infiltration in cutaneous late phase response in Balb/c mice sensitized with ovalbumin (OVA). Journal of Dermatology 24, 73–79 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sagara H, Matsuda H, Wada N, Yagita H, Fukuda T, Okumura K, Makino S, Ra C, A monoclonal antibody against very late activation antigen-4 inhibits eosinophil accumulation and late asthmatic response in a guinea pig model of asthma. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology 112, 287–294 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chin JE, Hatfield CA, Winterrowd GE, Brashler JR, Vonderfecht SL, Fidler SF, Griffin RL, Kolbasa KP, Krzesicki RF, Sly LM, Staite ND, Richards IM, Airway recruitment of leukocytes in mice is dependent on alpha4-integrins and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. American Journal of Physiology 272, L219–L229 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook-Mills JM, Deem TL, Active participation of endothelial cells in inflammation. Journal of leukocyte biology 77, 487–495 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vestweber D, Novel insights into leukocyte extravasation. Current opinion in hematology 19, 212–217 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muller WA, Mechanisms of leukocyte transendothelial migration. Annual review of pathology 6, 323–344 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang L, Cohn L, Zhang DH, Homer R, Ray A, Ray P, Essential role of nuclear factor kappaB in the induction of eosinophilia in allergic airway inflammation. Journal of Experimental Medicine 188, 1739–1750 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mould AW, Ramsay AJ, Matthaei KI, Young IG, Rothenberg ME, Foster PS, The effect of IL-5 and eotaxin expression in the lung on eosinophil trafficking and degranulation and the induction of bronchial hyperreactivity. J Immunol 164, 2142–2150 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunter SC, Cahoon EB, Enhancing vitamin E in oilseeds: unraveling tocopherol and tocotrienol biosynthesis. Lipids 42, 97–108 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uauy R, Hoffman DR, Birch EE, Birch DG, Jameson DM, Tyson J, Safety and efficacy of omega-3 fatty acids in the nutrition of very low birth weight infants: soy oil and marine oil supplementation of formula. J Pediatr 124, 612–620 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cook-Mills JM, McCary CA, Isoforms of Vitamin E Differentially Regulate Inflammation. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 10, 348–366 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang Q, Christen S, Shigenaga MK, Ames BN, gamma-tocopherol, the major form of vitamin E in the US diet, deserves more attention. Am J Clin Nutr 74, 714–722 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Talegawkar SA, Johnson EJ, Carithers T, Taylor HA Jr., Bogle ML, Tucker KL, Total alpha-tocopherol intakes are associated with serum alpha-tocopherol concentrations in African American adults. J Nutr 137, 2297–2303 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook-Mills JM, Avila PC, Vitamin E and D regulation of allergic asthma immunopathogenesis. Int Immunopharmacol 29, 007 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdala-Valencia H, Berdnikovs S, Cook-Mills JM, Vitamin E isoforms as modulators of lung inflammation. Nutrients 5, 4347–4363 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cook-Mills JM, Abdala-Valencia H, Hartert T, Two faces of vitamin e in the lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 188, 279–284. doi: 210.1164/rccm.201303–200503ED. (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bieri JG, Evarts RP, Tocopherols and fatty acids in American diets. The recommended allowance for vitamin E. J Am Diet Assoc. 62, 147–151. (1973). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bieri JG, Evarts RP, Vitamin E adequacy of vegetable oils. J Am Diet Assoc. 66, 134–139. (1975). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choo JH, Nagata M, Sutani A, Kikuchi I, Sakamoto Y, Theophylline attenuates the adhesion of eosinosphils to endothelial cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 131 Suppl 1, 40–45 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller M, Sung KL, Muller WA, Cho JY, Roman M, Castaneda D, Nayar J, Condon T, Kim J, Sriramarao P, Broide DH, Eosinophil tissue recruitment to sites of allergic inflammation in the lung is platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule independent. J Immunol 167, 2292–2297 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davenpeck KL, Berens KL, Dixon RA, Dupre B, Bochner BS, Inhibition of adhesion of human neutrophils and eosinophils to P-selectin by the sialyl Lewis antagonist TBC1269: preferential activity against neutrophil adhesion in vitro. J Allergy Clin Immunol 105, 769–775 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berdnikovs S, Abdala-Valencia H, McCary C, Somand M, Cole R, Garcia A, Bryce P, Cook-Mills J, Isoforms of Vitamin E have Opposing Immunoregulatory Functions during Inflammation by Regulating Leukocyte Recruitment. J Immunol 182, 4395–4405 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meydani SN, Shapiro AC, Meydani M, Macauley JB, Blumberg JB, Effect of age and dietary fat (fish, corn and coconut oils) on tocopherol status of C57BL/6Nia mice. Lipids 22, 345–350 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Myou S, Zhu X, Boetticher E, Myo S, Meliton A, Lambertino A, Munoz NM, Leff AR, Blockade of focal clustering and active conformation in beta 2-integrin-mediated adhesion of eosinophils to intercellular adhesion molecule-1 caused by transduction of HIV TAT-dominant negative Ras. J Immunol 169, 2670–2676 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCary CA, Abdala-Valencia H, Berdnikovs S, Cook-Mills JM, Supplemental and highly elevated tocopherol doses differentially regulate allergic inflammation: reversibility of alpha-tocopherol and gamma-tocopherol’s effects. J Immunol 186, 3674–3685 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cook-Mills JM, Marchese ME, Abdala-Valencia H, Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression and signaling during disease: regulation by reactive oxygen species and antioxidants. Antioxid Redox Signal 15, 1607–1638 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abdala-Valencia H, Berdnikovs S, Cook-Mills JM, Vitamin E isoforms differentially regulate intercellular adhesion molecule-1 activation of PKCalpha in human microvascular endothelial cells. PLoS ONE 7, e41054 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCary CA, Yoon Y, Panagabko C, Cho W, Atkinson J, Cook-Mills JM, Vitamin E isoforms directly bind PKCalpha and differentially regulate activation of PKCalpha. Biochem J 441, 189–198 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marchese ME, Kumar R, Colangelo LA, Avila PC, Jacobs DR Jr., Gross M, Sood A, Liu K, Cook-Mills JM, The vitamin E isoforms alpha-tocopherol and gamma-tocopherol have opposite associations with spirometric parameters: the CARDIA study. Respir Res 15, 31 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Devaraj S, Tang R, Adams-Huet B, Harris A, Seenivasan T, de Lemos JA, Jialal I, Effect of high-dose alpha-tocopherol supplementation on biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation and carotid atherosclerosis in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Clin Nutr 86, 1392–1398 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allen S, Britton JR, Leonardi-Bee JA, Association between antioxidant vitamins and asthma outcome measures: systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 64, 610–619 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cook-Mills JM, in Eosinophils in Health and Disease., Lee J. J. a. R., F H, Ed. ( Elsevier, 2012), pp. 139–153. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Redlich CA, Grauer JN, Van Bennekum AM, Clever SL, Ponn RB, Blaner WS, Characterization of carotenoid, vitamin A, and alpha-tocopheral levels in human lung tissue and pulmonary macrophages. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 154, 1436–1443 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiss ST, Diet as a risk factor for asthma. Ciba Fndn Symp 206, 244–257 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Troisi RJ, Willett WC, Weiss ST, Trichopoulos D, Rosner B, Speizer FE, A prospective study of diet and adult-onset asthma [see comments]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 151, 1401–1408 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dow L, Tracey M, Villar A, Coggon D, Margetts BM, Campbell MJ, Holgate ST, Does dietary intake of vitamins C and E influence lung function in older people? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 154, 1401–1404 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smit HA, Grievink L, Tabak C, Dietary influences on chronic obstructive lung disease and asthma: a review of the epidemiological evidence. Proc Nutr Soc 58, 309–319 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tabak C, Smit HA, Rasanen L, Fidanza F, Menotti A, Nissinen A, Feskens EJ, Heederik D, Kromhout D, Dietary factors and pulmonary function: a cross sectional study in middle aged men from three European countries. Thorax 54, 1021–1026 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoskins A, Roberts JL 2nd, Milne G, Choi L, Dworski R, Natural-source d-alphatocopheryl acetate inhibits oxidant stress and modulates atopic asthma in humans in vivo. Allergy 67, 676–682 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kurti SP, Murphy JD, Ferguson CS, Brown KR, Smith JR, Harms CA, Improved lung function following dietary antioxidant supplementation in exercise-induced asthmatics. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 220:95–101., 10.1016/j.resp.2015.1009.1012. Epub 2015 Nov 1016. (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Devereux G, Seaton A, Diet as a risk factor for atopy and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 115, 1109–1117; quiz 1118 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Devereux G, Early life events in asthma--diet. Pediatr Pulmonol 42, 663–673 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pearson PJ, Lewis SA, Britton J, Fogarty A, Vitamin E supplements in asthma: a parallel group randomised placebo controlled trial. Thorax 59, 652–656 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hernandez M, Zhou H, Zhou B, Robinette C, Crissman K, Hatch G, Alexis NE, Peden D, Combination treatment with high-dose vitamin C and alpha-tocopherol does not enhance respiratory-tract lining fluid vitamin C levels in asthmatics. Inhal Toxicol 21, 173–181 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Erkkola M, Karppinen M, Javanainen J, Rasanen L, Knip M, Virtanen SM, Validity and reproducibility of a food frequency questionnaire for pregnant Finnish women. Am J Epidemiol. 154, 466–476. (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.West CE, Dunstan J, McCarthy S, Metcalfe J, D’Vaz N, Meldrum S, Oddy WH, Tulic MK, Prescott SL, Associations between maternal antioxidant intakes in pregnancy and infant allergic outcomes. Nutrients. 4, 1747–1758. doi: 1710.3390/nu4111747. (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maslova E, Hansen S, Strom M, Halldorsson TI, Olsen SF, Maternal intake of vitamins A, E and K in pregnancy and child allergic disease: a longitudinal study from the Danish National Birth Cohort. Br J Nutr. 111, 1096–1108. (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zahran HS, Bailey C, Factors associated with asthma prevalence among racial and ethnic groups-United States, 2009–2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. J Asthma 11, 11 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elenius V, Palomares O, Waris M, Turunen R, Puhakka T, Ruckert B, Vuorinen T, Allander T, Vahlberg T, Akdis M, Camargo CA Jr., Akdis CA, Jartti T, The relationship of serum vitamins A, D, E and LL-37 levels with allergic status, tonsillar virus detection and immune response. PLoS One. 12, e0172350. (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hamalainen N, Nwaru BI, Erlund I, Takkinen HM, Ahonen S, Toppari J, Ilonen J, Veijola R, Knip M, Kaila M, Virtanen SM, Serum carotenoid and tocopherol concentrations and risk of asthma in childhood: a nested case-control study. Clin Exp Allergy. 47, 401–409. (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cook-Mills J, Gebretsadik T, Abdala-Valencia H, Green J, Larkin EK, Dupont WD, Shu XO, Gross M, Bai C, Gao YT, Hartman TJ, Rosas-Salazar C, Hartert T, Interaction of vitamin E isoforms on asthma and allergic airway disease. Thorax. 71, 954–956. (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stone CA Jr., Cook-Mills J, Gebretsadik T, Rosas-Salazar C, Turi K, Brunwasser SM, Connolly A, Russell P, Liu Z, Costello K, Hartert TV, Delineation of the Individual Effects of Vitamin E Isoforms on Early Life Incident Wheezing. J Pediatr 206, 156–163. (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jacobs RR, Boehlecke B, van Hage-Hamsten M, Rylander R, Bronchial reactivity, atopy, and airway response to cotton dust. Am Rev Respir Dis 148, 19–24 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Delfino RJ, Quintana PJ, Floro J, Gastanaga VM, Samimi BS, Kleinman MT, Liu LJ, Bufalino C, Wu CF, McLaren CE, Association of FEV1 in asthmatic children with personal and microenvironmental exposure to airborne particulate matter. Environ Health Perspect 112, 932–941 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koskela H, Tukiainen H, Kononoff A, Pekkarinen H, Effect of whole-body exposure to cold and wind on lung function in asthmatic patients. Chest 105, 1728–1731 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Blanc PD, Eisner MD, Katz PP, Yen IH, Archea C, Earnest G, Janson S, Masharani UB, Quinlan PJ, Hammond SK, Thorne PS, Balmes JR, Trupin L, Yelin EH, Impact of the home indoor environment on adult asthma and rhinitis. J Occup Environ Med 47, 362–372 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Meydani SN, Leka LS, Fine BC, Dallal GE, Keusch GT, Singh MF, Hamer DH, Vitamin E and respiratory tract infections in elderly nursing home residents: a randomized controlled trial. Jama 292, 828–836 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bou Ghanem EN, Lee JN, Joma BH, Meydani SN, Leong JM, Panda A, The Alpha-Tocopherol Form of Vitamin E Boosts Elastase Activity of Human PMNs and Their Ability to Kill Streptococcus pneumoniae. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 7, 161 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bou Ghanem EN, Clark S, Du X, Wu D, Camilli A, Leong JM, Meydani SN, The α-tocopherol form of vitamin E reverses age-associated susceptibility to streptococcus pneumoniae lung infection by modulating pulmonary neutrophil recruitment. J Immunol 194, 1090–1099 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hemilä H, Vitamin E administration may decrease the incidence of pneumonia in elderly males. Clinical interventions in aging 11, 1379–1385 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Han SN, Meydani M, Wu D, Bender BS, Smith DE, Viña J, Cao G, Prior RL, Meydani SN, Effect of long-term dietary antioxidant supplementation on influenza virus infection. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences 55, B496–503 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heinzerling RH, Tengerdy RP, Wick LL, Lueker DC, Vitamin E protects mice against Diplococcus pneumoniae type I infection. Infect Immun 10, 1292–1295 (1974). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pincemail J, Cavalier E, Charlier C, Cheramy-Bien JP, Brevers E, Courtois A, Fadeur M, Meziane S, Goff CL, Misset B, Albert A, Defraigne JO, Rousseau AF, Oxidative Stress Status in COVID-19 Patients Hospitalized in Intensive Care Unit for Severe Pneumonia. A Pilot Study. Antioxidants 10, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kalayci O, Besler T, Kilinc K, Sekerel BE, Saraclar Y, Serum levels of antioxidant vitamins (alpha tocopherol, beta carotene, and ascorbic acid) in children with bronchial asthma. Turk J Peds 42, 17–21 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kelly FJ, Mudway I, Blomberg A, Frew A, Sandstrom T, Altered lung antioxidant status in patients with mild asthma [letter]. Lancet 354, 482–483 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schunemann HJ, Grant BJ, Freudenheim JL, Muti P, Browne RW, Drake JA, Klocke RA, Trevisan M, The relation of serum levels of antioxidant vitamins C and E, retinol and carotenoids with pulmonary function in the general population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 163, 1246–1255 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Al-Abdulla NO, Al Naama LM, Hassan MK, Antioxidant status in acute asthmatic attack in children. J Pak Med Assoc 60, 1023–1027 (2010). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Larkin EK, Gao YT, Gebretsadik T, Hartman TJ, Wu P, Wen W, Yang G, Bai C, Jin M, Roberts LJ, 2nd, Gross M, Shu XO, Hartert TV, New risk factors for adult-onset incident asthma. A nested case-control study of host antioxidant defense. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 191, 45–53 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lim RH, Kobzik L, Maternal transmission of asthma risk. Am J Reprod Immunol 61, 1–10 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]