Abstract

A dual marker system was developed for simultaneous quantification of bacterial cell numbers and their activity with the luxAB and gfp genes, encoding bacterial luciferase and green fluorescent protein (GFP), respectively. The bioluminescence phenotype of the luxAB biomarker is dependent on cellular energy status. Since cellular metabolism requires energy, bioluminescence output is directly related to the metabolic activity of the cells. By contrast, GFP fluorescence has no energy requirement. Therefore, by combining these two biomarkers, total cell number and metabolic activity of a specific marked cell population could be monitored simultaneously. Two different bacterial strains, Escherichia coli DH5α and Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25, were chromosomally tagged with the dual marker cassette, and the cells were monitored under different conditions by flow cytometry, plate counting, and luminometry. During log-phase growth, the luciferase activity was proportional to the number of GFP-fluorescent cells and culturable cells. Upon entrance into stationary phase or during starvation, luciferase activity decreased due to a decrease in cellular metabolic activity of the population, but the number of GFP-fluorescing cells and culturable cells remained relatively stable. In addition, we optimized a procedure for extraction of bacterial cells from soil, allowing GFP-tagged bacteria in soil samples to be quantitated by flow cytometry. After 30 days of incubation of P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp/lux in soil, the cells were still maintained at high population densities, as determined by GFP fluorescence, but there was a slow decline in luciferase activity, implicating nutrient limitation. In conclusion, the dual marker system allowed simultaneous monitoring of the metabolic activity and cell number of a specific bacterial population and is a promising tool for monitoring of specific bacteria in situ in environmental samples.

Microorganisms are exploited in many areas of environmental biotechnology, including bioremediation, biocontrol, and plant growth enhancement. Increasingly, genetically engineered microorganisms (GEMs) are being constructed for these environmental applications. To assess product efficacy and potential risks of release of GEMs into nature, specific and sensitive monitoring methods are required (14, 23).

Traditional techniques for assessment of microbial numbers and metabolic activity generally lack the specificity required for monitoring of GEMs (15). Therefore, novel molecular biology-based techniques such as DNA probing and marker gene tagging have recently been developed as specific methods to identify and quantitate populations of specific microorganisms in the environment (15).

One of the most promising markers is the gfp gene, encoding the green fluorescent protein (GFP). An advantage of GFP is that, unlike other biomarkers, it does not require any substrate or additional cofactors in order to fluoresce (5). Since the gfp gene is eukaryotic in origin, it was first necessary to develop optimized constructs for expression of gfp in bacteria. Recently, an optimized gfp cassette has been described with gfp under the control of a strong constitutive promoter and with an optimized ribosome binding site (28). In this cassette, wild-type gfp was supplanted by a mutant with the excitation maximum of the GFP shifted towards the red region of the light spectrum (10). These red-shifted mutants have been shown to have a higher fluorescence output in bacteria (10).

Another reason that GFP is becoming so popular is that single cells tagged with gfp can easily be visualized by epifluorescence microscopy (3, 26, 28). Normally, a single copy of gfp integrated into the chromosome is sufficient for visualization of cells (26, 28, 31). In some cases a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera can be used to enhance weak fluorescence signals or to compensate for autofluorescence in certain sample types (28, 31). It is also possible to enhance the intensity of the fluorescent signal by chromosomal integration of two tandem copies of gfp (30).

In addition, fluorescent cells may be rapidly enumerated by flow cytometry (24). The flow cytometer measures parameters related to size, shape, and fluorescence of individual particles. Hundreds of cells may be analyzed per second when passing the laser beam of the flow cytometer, providing a statistically significant picture of the sample’s physical and biochemical makeup. Flow cytometry has recently been demonstrated to be an excellent technique for analysis and quantitation of GFP-fluorescent bacterial cell populations (28–31).

From a biotechnological or functional aspect, the active fraction of a bacterial population is the most important, since this is the fraction that exerts an effect on the environment. However, not all viable cells in a population are metabolically active under all conditions, although they may have the potential to become activated under favorable circumstances. Although gfp-tagged cells have been shown to fluoresce under a variety of growth conditions, including starvation (28), the GFP fluorescence phenotype does not indicate the metabolic status of the cells. Therefore, alternative markers are necessary if metabolic activity is to be determined.

One of the most promising markers for determination of cellular metabolic activity is bacterial luciferase, encoded by the luxAB genes (6, 17, 18). Bacterial luciferase catalyzes the following reaction: RCHO + O2 + FMNH2→RCOOH + H2O + FMN + light (490 nm), where R is a long-chain fatty aldehyde. Due to the requirement for reducing equivalents (FMNH2), the bioluminescence phenotype of the luxAB biomarker is dependent on cellular energy status. Since cellular metabolism requires energy, the bioluminescence output is directly related to the metabolic activity of the cells. Therefore, bioluminescence can be used to assess the metabolic activity of specific bacterial populations (6, 15–18, 23). Eukaryotic luciferase can also be used to monitor metabolic activity, since this reaction is also energy dependent, on ATP in this case (15, 19). One advantage of the bacterial luciferase system, however, is that the substrate, n-decanal, is volatile and therefore easier to apply in a nondestructive manner to soil and plant tissue samples, compared to the liquid luciferin substrate for the eukaryotic enzyme.

Luciferase activity has been shown to be proportional to biomass in growing bacterial populations. However, under nutrient-limited conditions the FMNH2 concentration becomes limiting for the luciferase reaction and the bioluminescence of the population decreases substantially compared to that of the biomass (6, 8, 18). For example, when Pseudomonas fluorescens cells tagged with luxAB genes were monitored in sterile soil microcosms, the light output decreased over time, but the number of viable cells remained relatively constant (18). Amendment of the soil with nutrients enabled the viable cell population to regain activity as measured by an increase in bioluminescence (18). Direct measurement of luminescence from unamended environmental samples, by contrast, provides a measure of the in situ metabolic activity of the marked cell population and is comparable to other activity measurements, such as dehydrogenase activity assays (17, 18, 23).

In order to fully describe the dynamics of a specific microbial population, both the total bacterial biomass and the metabolic activity of the cells have to be assessed. Therefore, the goal of this work was to combine the advantageous properties of the two biomarkers, gfp and luxAB, for simultaneous quantitation of cell numbers and metabolic activity of a specific microbial population in complex environmental samples, such as soil. The dual marker system we describe should be applicable for quantitation of GEMs in nature, since the marker phenotypes are specific to the tagged cells. We chose P. fluorescens SBW25 as a target strain for these studies due to its biotechnological potential as a plant growth-promoting agent (1). Also, considerable data is already available concerning the behavior of a genetically modified derivative of this strain under field conditions (27).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli DH5α was used as the host strain for all plasmids, except for pUTgfplux, which was maintained in E. coli CC118(λpir).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | hsdR17(r− m+) supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 (Nalr) relA1 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 (lacZΔM15) | 9 |

| CC118(λpir) | Δ(ara-leu) araD ΔlacX74 galE galK phoA20 thi-1 rpsE argE(Am) recA1 λpir | 11 |

| DH5α::gfp/lux | E. coli DH5α::gfp-luxAB; Kmr | This work |

| P. fluorescens | ||

| SBW25 | Sugar beet leaf isolate | 1 |

| SBW25::gfp/lux | P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp-luxAB; Kmr | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSB230 | AprluxAB | 12 |

| pUC18Not | AprlacZ oriColE1 multiple cloning site flanked by NotI sites | 11 |

| pUTmini-Tn5 Km | Apr Kmr; delivery plasmid for mini-Tn5 Kmr | 11 |

| pBluescript SK(−) | Apr | Stratagene |

| pIC19Hgfp | PpsbA-gfp Apr | 28 |

| pAU102 | Apr; identical to pUC18Not but with insertion of ppsbA-gfp | This work |

| pAU103 | Apr; identical to pBluescript SK(−) but with insertion of luxAB | This work |

| pAU104 | Apr; identical to pAU102 but with insertion of luxAB | This work |

| pUTgfplux | Apr Kmr; delivery plasmid for mini-Tn5 PpsbA-gfp luxAB Kmr | This work |

P. fluorescens SBW25 is an isolate from sugar beet that colonizes plant roots (1) and was kindly provided by Mark Bailey (Natural Environment Research Council, Oxford, United Kingdom). E. coli DH5α::gfp/lux and P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp/lux are strains that were chromosomally tagged with the gfp-luxAB cassette (Table 1) as described below. All strains were grown in Luria broth (LB) at 28 to 30°C, supplemented with the following antibiotics when appropriate: ampicillin (100 μg ml−1) and/or kanamycin (50 μg ml−1).

Growth was routinely measured as optical density at 600 nm (OD600). In addition, the number of culturable cells was determined by counting colonies grown on LB plates supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg ml−1). During the starvation experiment (see below), cultures were also always plated onto LB without antibiotics to ensure that the cultures were not contaminated and to ensure marker stability.

Cloning procedures.

Cloning procedures were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (25). Plasmid DNA was isolated from E. coli host cells with the Wizard miniprep kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.) or the Qiagen plasmid maxiprep kit (Hilden, Germany). DNA was extracted from agarose gels with the JETSORB gel extraction kit (Genomed, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Restriction enzymes were purchased from Pharmacia (Stockholm, Sweden). We used the rapid DNA ligation kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) for DNA ligations.

Electroporation.

Plasmid DNA was introduced into E. coli cells by electroporation with the Bio-Rad Gene Pulser system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.) set at 2.5 kV, 200 Ω, and 25 μF.

Minitransposons used for chromosomal integration of the gfp-luxAB genes were also introduced into E. coli DH5α and P. fluorescens SBW25 cells by electroporation as previously described (28), with the settings given above. Transformants were selected on LB medium containing kanamycin (50 μg ml−1).

Southern blot conditions.

Genomic DNA from transformants and wild-type controls was isolated according to standard procedures (25) and digested to completion with BglII. The DNA was transferred to a BioDyne nylon membrane (Pall BioSupport, East Hills, N.Y.) with the ECL protocol supplied by the manufacturers (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The gfp and the luxAB DNA probes were isolated as separate bands from plasmid pAU104 digested with EcoRI, XmaI, and SalI. The bands were well separated on the gel and purified from the agarose gel with a JETSORB gel extraction kit. The probes were labelled with the ECL direct nucleic acid labelling and detection system (Amersham). Hybridization was performed at 42°C overnight in gold hybridization buffer (ECL; Amersham) followed by two washes (20 min each, also at 42°C) in a solution containing 6 M urea, 0.4% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 0.5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate).

Studies during growth in rich media.

Overnight cultures were diluted 1:500 in 1 liter of LB, supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg ml−1), and divided into two 500-ml cultures. The cultures were incubated at 30°C while being shaken. Samples of the cultures (3 ml) were removed at specified intervals, and if necessary, the samples were diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer (8 g of NaCl per liter, 0.2 g of KCl per liter, 1.44 g of Na2HPO4 per liter, 0.24 g of KH2PO4 per liter, pH 7.4) before analysis by luminometry, flow cytometry, and plate counting.

Starvation conditions.

Inocula for experiments conducted under carbon and nitrogen starvation conditions were harvested from log-phase cultures (OD600, 0.7), washed once in PBS buffer, and resuspended in 1 liter of PBS buffer to a concentration of approximately 107 cells ml−1. The cultures were divided into two 500-ml duplicate portions and incubated at 30°C while being shaken. Aliquots of the starved cultures (5 ml) were removed at specified intervals, cell clumps were resuspended by being vortexed for 2 to 3 min, and the samples were diluted in PBS buffer before analysis by luminometry, flow cytometry, and plate counting.

Monitoring P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp/lux in nonsterile soil samples.

The soil used in these experiments was a Pustnäs sandy loam (Typic Udipsamment; illitic). The soil was air dried (3.3% moisture content), and 200-mg samples were added to microcentrifuge tubes. The soil samples were inoculated with log-phase (OD600, 0.7) cultures of P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp/lux. Before inoculation, the cultures were washed twice with 1.5× PBS and stored on ice, for approximately 1 h, during calculation of the density of the inoculum by flow cytometry. Then 10 μl was added to the soil to a final concentration of 6.4 × 108 cells g (dry weight) of soil−1.

At specified intervals, the bacterial fraction was isolated from five inoculated soil samples, plus one uninoculated control, by a modification of the density gradient centrifugation technique developed previously (2). To each sample, 8 mg of acid-washed polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP) prepared as previously described (13) and 400 μl of distilled water were added. After being mixed by vortexing for 1 min, gross soil particles settled in the tube, and the upper phase (300 μl) was transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube. Two additional washing steps were performed with 200 μl of water, and the entire supernatants were added to the tube containing the original upper phase, leaving only the gross soil pellet behind. The pooled soil suspensions were mixed by vortexing followed by centrifugation for 6 min at 100 × g. The supernatant was carefully transferred to a microcentrifuge tube containing 700 μl of Nycodenz (Nycomed Pharma, Oslo, Norway) with a density of 1.3 g ml−1. The discontinuous Nycodenz-cell suspension gradient was centrifuged for 30 min at 10,000 × g at a temperature of 4°C. The upper 500 μl of the gradient was discarded, and the next 550 μl, containing the banded soil bacterial fraction, was transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube. The volume was brought up to 1 ml by the addition of 450 μl of 1.5× PBS. The samples were then analyzed for the number of GFP-fluorescing cells by flow cytometry and for luciferase activity by luminometry as described below.

Luminometry.

Luciferase activity was measured in a luminometer built by Bo Höijer (Department of Biochemistry, Stockholm University). The substrate for the luciferase reaction, 1 μl of 0.5% n-decanal in ethanol, was placed at the bottom of a 1.5-ml plastic cuvette. Cells were added to the cuvette in 500-μl aliquots, and luminescence was measured after 4 min of incubation at room temperature. Background levels of luminescence were in the range of 50 to 200 quanta s−1, and these values were always subtracted from the sample readings, which were between 200 and 40,000 quanta s−1. When necessary, the cells were diluted in PBS buffer before measurement.

Flow cytometry.

The number of GFP-fluorescent cells in a sample was counted in a flow cytometer (FACScalibur; Becton Dickinson, Oxford, United Kingdom) equipped with a 15-mW, air-cooled argon ion laser excitation light source (488 nm). GFP fluorescence was detected with an HQ500LP filter (Chroma Technology Corp., Brattleboro, Vt.).

Before injection into the flow cytometer, 1-ml aliquots of the E. coli DH5α::gfp/lux culture were centrifuged for 10 min at 12,500 × g and the cell pellet was resuspended in filtered (0.22-μm pore size) 1.5× PBS. P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp/lux cells were simply diluted in filtered 1.5× PBS. For enumeration of the cells in the sample, an internal standard consisting of a known concentration of polystyrene fluorescent microspheres, 2.2 μm in diameter (Duke Scientific, Palo Alto, Calif.), was added to the final cell suspension before injection into the flow cytometer. The number of cells in the suspension was calculated by relation to the number of microspheres counted in the sample, as previously described (28). Approximately 10,000 cells were counted for each sample.

Direct visualization of fluorescent colonies.

Fluorescent colonies were visualized directly under a black-light blue lamp (Philips, catalog no. 73411; Eindhoven, The Netherlands) in a dark room.

RESULTS

Construction of a mini-Tn5 gfp-luxAB cassette.

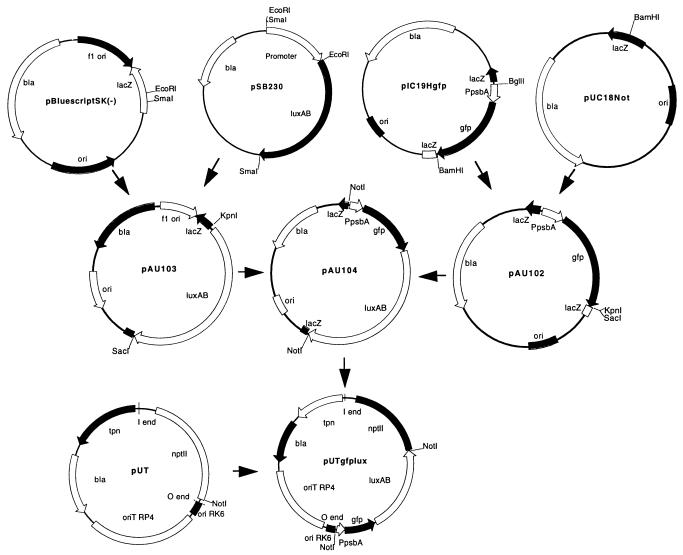

A minitransposon was constructed for stable integration of both the gfp and the luxAB genes into the chromosomes of bacteria (Fig. 1). The red-shifted gfp mutant, P11 (10), referred to as gfp in this communication, was used in all constructs due to its fluorescence intensity in bacterial cells, which was higher than that of wild-type gfp. The gfp gene and the psbA promoter (7) were isolated from plasmid pIC19Hgfp (Table 1) as a BglII/BamHI fragment and inserted into BamHI-digested pUC18Not (Table 1). A clone was selected (pAU102) with the gfp insertion in the appropriate orientation for eventual cloning of the luxAB genes. Before insertion of luxAB into pAU102, it was excised from plasmid pSB230 (Table 1) as an EcoRI/SmaI fragment and inserted into pBluescript SK(−) (Table 1) for acquisition of KpnI and SacI restriction sites (pAU103). Then luxAB was excised from pAU103 as a KpnI/SacI fragment and inserted into pAU102, giving rise to pAU104. The PpsbA-gfp-luxAB cassette was excised from pAU104 by NotI digestion and ligated into the NotI site of pUTmini-Tn5 (Table 1), resulting in the minitransposon vector pUTgfplux (Fig. 1). Both gfp and luxAB are expressed from the psbA promoter, which is known to be a strong constitutive promoter in bacteria (7).

FIG. 1.

Cloning strategy for the pUTgfplux vector. Only key restriction sites used for the cloning are shown. Plasmids are not drawn to scale relative to each other. Details of the individual plasmids are given in Table 1 and in the text.

Chromosomal integration of the gfp-luxAB cassette into the chromosomes of E. coli DH5α and P. fluorescens SBW25.

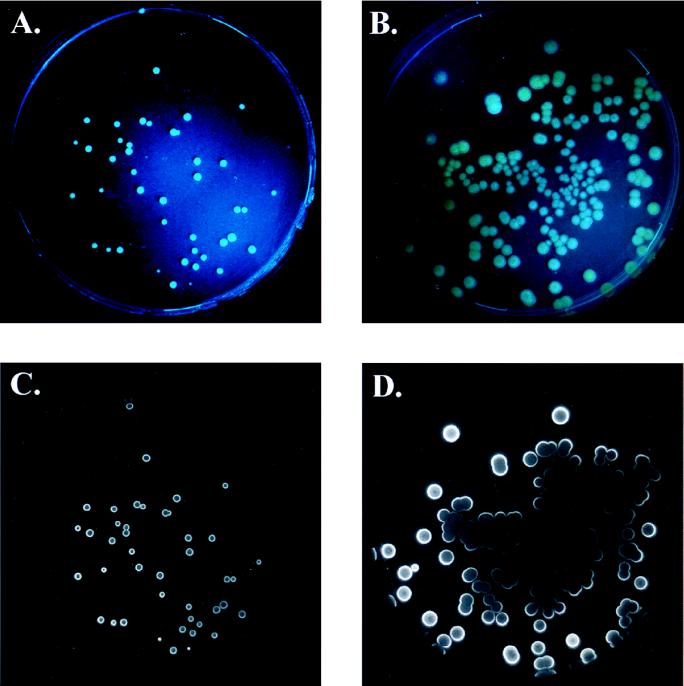

The pUTgfplux plasmid was introduced into E. coli DH5α and P. fluorescens SBW25 cells by electroporation. All transformants arising on selective agar plates could be visualized both by the GFP phenotype (as fluorescent colonies) and by the luciferase phenotype (as light-emitting colonies) (Fig. 2). Single chromosomal integration of the gfp-luxAB genes was confirmed by Southern blot analysis with the gfp gene and the luxAB genes as probes (data not shown). In both cases, the same band on duplicate gels, from BglII genomic DNA digestions, hybridized to both probes, indicating the colocalization of the two biomarkers into the chromosomes.

FIG. 2.

Photographs of colonies of E. coli DH5α::gfp/lux (A and C) and P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp/lux (B and D). Upper panels are photographs of GFP-fluorescing colonies, taken with Fuji Super G Plus 400 film with a 15- to 30-s exposure. Lower panels are CCD images of the same colonies after n-decanal addition. Images were obtained with a Peltier-cooled (−50°C) CCD camera in a light-tight box with 3-min exposures.

The insertion of the gfp-luxAB cassette was stable in both strains; after repeated transfers into nonselective LB medium (approximately 40 generations), there was no loss of either green colony fluorescence or colony luminescence. In addition, there was no loss of either phenotype noted for colonies grown on nonselective agar plates after prolonged incubation in nutrient-limited medium (see description of starvation experiments below).

Phenotype comparisons of transformant and wild-type strains.

Several transformants of each strain were initially analyzed by flow cytometry. The transformants used in this work were selected by confirmation that the size and granularity of the transformants were the same as those of the wild-type cells by flow cytometric analyses of the forward and side scatter properties of the cells (data not shown). Another criterion was that the GFP fluorescence intensity was not unusually high or low compared to the rest of the transformants. Outliers were rejected for further consideration.

One transformant for each strain was selected for further study and compared to the wild-type strains during growth in LB medium. The maximum growth rates (μmax) for the wild-type strains and transformants were approximately 0.75 h−1 for the P. fluorescens SBW25 strains and approximately 0.55 h−1 for the E. coli DH5α strains, and so the transformants were not impaired in their ability to grow under these conditions.

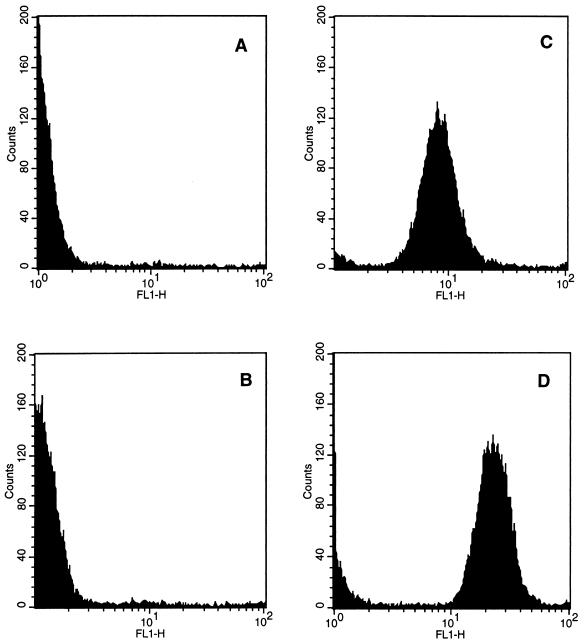

The transformants could easily be distinguished from the wild-type strains based on the phenotypes encoded by the two marker genes. The GFP fluorescence intensity of the transformants, as measured by flow cytometry, was much greater than the autofluorescence of the wild-type strains (Fig. 3). The gfp-tagged pseudomonad exhibited a higher fluorescence intensity than that of the E. coli strain, which could be due to a number of factors particular to the organisms. Also, the tagged strains exhibited a high luciferase activity (approximately 108 quanta s−1 ml of culture1; OD600, 0.8 to 1.0) when grown in nutrient media. No background luminescence in the wild-type strains was observed by luminometry (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Fluorescence intensity comparisons of E. coli DH5α (wild type) (A), P. fluorescens SBW25 (wild type) (B), E. coli DH5α::gfp/lux (C), and P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp/lux (D). Cultures were grown overnight at 30°C and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in Materials and Methods. FL1-H is the fluorescence intensity per cell. The counts shown on the y axis are the numbers of individual fluorescent particles detected.

Monitoring during growth in rich media.

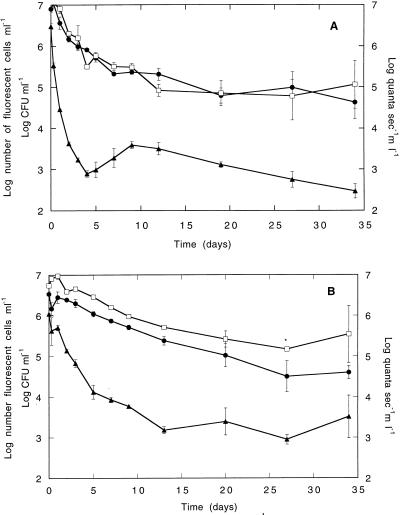

The two bacterial strains, E. coli DH5α::gfp/lux and P. fluorescens SBW25:: gfp/lux, were monitored during growth in rich media to study the performance of the gfp and luxAB markers under these conditions (Fig. 4). During log-phase growth, the luminescence output was proportional to the bacterial biomass, as determined by the number of culturable and GFP-fluorescent cells, and all three measurements were highly correlated (r > 95). Once the cultures reached stationary phase, the luminescence decreased and was no longer correlated with the number of cells (Fig. 4), indicating a decrease in the metabolic activity of the population at stationary phase, as expected.

FIG. 4.

Monitoring of E. coli DH5α::gfp/lux cells (A) or P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp/lux cells (B) during growth in LB medium by flow cytometry, luminometry, and plate counting. Data represents the means of duplicate cultures; error bars show the standard deviations from the means. Filled circles, log CFU per milliliter; open squares, flow cytometric measurements (log fluorescent cell numbers per milliliter); filled triangles, luminescence values (log quanta per second per milliliter).

Monitoring during starvation.

Both E. coli DH5α::gfp/lux and P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp/lux cells were monitored under carbon and nitrogen starvation conditions for 34 days to determine the effect of these conditions on the marker phenotypes for the chromosomally integrated genes, gfp and luxAB, respectively (Fig. 5). Log-phase cultures were used at the initiation of the starvation experiment in order to have a metabolically active population, with high levels of luciferase activity, from the start.

FIG. 5.

Monitoring of E. coli DH5α::gfp/lux cells (A) or P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp/lux cells (B) under starvation conditions by flow cytometry, luminometry, and plate counting. Data represents the means of two replicate cultures (for each replicate, duplicate samples were analyzed by luminometry and plate counting and 10,000 cells were analyzed by flow cytometry). The asterisk indicates that data and error bars are shown for duplicate samples of only one of the replicates on sampling day 27 for P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp/lux (B) since there were problems with cell clumping on this date. Filled circles, log CFU per milliliter; open squares, flow cytometric measurements (log fluorescent cell number per milliliter); filled triangles, luminescence values (log quanta per second per milliliter).

For E. coli DH5α::gfp/lux, the number of GFP-fluorescing cells counted during the experiment declined by 2 orders of magnitude during the first 12 days of incubation, after which the number remained relatively constant (Fig. 5A). The flow cytometry data closely paralleled the values obtained by plate counting, even on nonselective medium, and the values were highly correlated (r = 0.95). However, the luciferase activity decreased dramatically, from approximately 106 quanta s−1 ml−1 to 103 quanta s−1 ml−1 during the first 4 days of starvation, presumably due to energy limitation for the luciferase reaction. After 5 days of incubation, the light output increased slightly and then slowly declined for the remainder of the experiment (Fig. 5A).

The number of GFP-fluorescing P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp/lux cells decreased slightly during the 34-day incubation period, by no more than 1 order of magnitude (Fig. 5B). The number of culturable cells also decreased over the time course of the experiment by approximately 2 orders of magnitude (Fig. 5B). Although the plate count data and fluorescent cell count data were relatively parallel and highly correlated (r = 0.95), the number of fluorescent cells counted was significantly higher than the number of CFU, except for sampling on day 20.

The initial decrease in luciferase activity was more gradual for the P. fluorescens transformant than for the E. coli transformant. However, for P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp/lux there was a drop in light emission from 106 quanta s−1 ml−1, which leveled off after approximately 13 days to a relatively constant value between 103 and 104 quanta s−1 ml−1 for the remainder of the incubation period (Fig. 5B).

Optimization of bacterial extraction from soil for flow cytometry.

In order to enumerate the GFP-fluorescing cells in soil by flow cytometry, it was necessary to extract the bacterial fraction from soil particles and debris. Therefore, we optimized a Nycodenz density gradient centrifugation technique for this purpose. Nycodenz is known to be a suitable gradient material for selective separation of bacterial cells from soil particles (2). We found that the protocol was optimized by addition of PVPP to the sample before centrifugation. PVPP is known to selectively complex and precipitate humic materials from soil samples (13). This improved the cell recovery by approximately 30% and simultaneously reduced background interference. In addition, the protocol was adapted to a microcentrifuge format to reduce the time required for sample preparation. Routinely, more than 70% of the cells known to be added to the soil were extracted by this method.

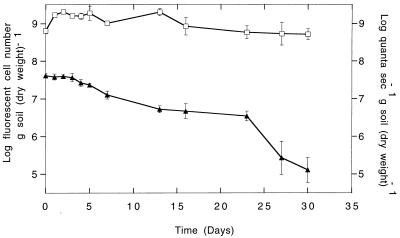

Monitoring of P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp/lux in soil samples.

The number of GFP-fluorescing cells per gram (dry weight) of soil, as determined by flow cytometry, was stable during 30 days of incubation in soil. The cell number increased initially upon inoculation into soil (Fig. 6). The cell density in the soil was relatively constant for the remainder of the experiment, varying within 1 order of magnitude. For the entire sampling period, the GFP fluorescence intensity was always sufficiently high for the cells to be detected and counted by flow cytometry.

FIG. 6.

Monitoring of P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp/lux cells in soil samples by flow cytometry and luminometry. Open squares, flow cytometric measurements (log fluorescent cell number per gram [dry weight] of soil); filled triangles, luminescence values (quanta per second per gram [dry weight] of soil). Data represents the means of five replicate soil samples, and error bars represent the standard deviations of the means.

The luciferase activity of the population declined gradually when the cells were incubated in soil (Fig. 6). After 23 days, the decline was more dramatic, resulting in a total decline in luciferase activity of 2.5 orders of magnitude by the end of the sampling period. By comparison of the values given (Fig. 6), it can be seen that the luciferase activity per cell decreased rapidly after introduction to soil from an initial value of 6.5 × 10−2 quanta s−1 cell−1 to 2.3 × 10−2 quanta s−1 cell−1 on day 1 and then slowly declined during the remainder of the experiment to a final value of 2.9 × 10−4 quanta s−1 cell−1.

DISCUSSION

A novel minitransposon vector was constructed for stable integration of both the gfp and the luxAB genes into the chromosomes of bacterial cells (Fig. 1). This is the first demonstration of the combined application of these biomarkers. The transformants were easily scored as fluorescent colonies under blue-light illumination and as luminescent colonies after addition of the n-decanal substrate (Fig. 2). The luciferase activity is concentrated mainly at the periphery of the bacterial colonies. This localization could be due to the presence of actively growing cells in this region, to oxygen and/or substrate limitation in the center of the colony, or to all of these. By contrast, GFP fluorescence is spread evenly throughout the colony (Fig. 2), due to less dependence on metabolic activity and/or oxygen demand, compared to luciferase.

We assessed the performance of the dual marker system under different growth conditions to ascertain the dependence of the phenotypes of the two biomarkers on the cellular energy status. Previously, we found that P. fluorescens A506, chromosomally tagged with gfp, was fluorescent after incubation during growth and under carbon and nitrogen starvation conditions (28). By contrast, other investigators have demonstrated that the luciferase output from luxAB-tagged bacteria decreases during starvation (6, 17).

In this study, two bacterial strains, P. fluorescens SBW25 and E. coli DH5α, were monitored under growth and nutrient-limiting conditions. We chose to study P. fluorescens SBW25 due to its application for biocontrol of fungal diseases (1), and E. coli DH5α was chosen for comparison. P. fluorescens SBW25, chromosomally tagged with lacZY (encoding β-galactosidase and lactose permease) and Kanr-xylE genes (encoding resistance to kanamycin and catechol-2,3-dioxygenase), has previously been monitored in field trials (27). However, the detection methods used could not distinguish the active population relative to the total number of cells, and only culturable cells were monitored. Therefore, we tested our dual marker system with this strain to determine whether it would be applicable for in situ monitoring of the distribution and metabolic activity of the cells in the environment during biocontrol applications. We also tested the dual marker system with E. coli to ensure that the results were not specific to P. fluorescens or to the chromosomal location of the gfp-luxAB cassette.

During log-phase growth of both strains in rich medium, the luciferase activity measurements paralleled the cell concentration, as determined by enumeration of GFP-fluorescent cells or by plate counting. However, upon entrance to stationary phase there was a higher decline in luciferase activity than in counts of GFP-fluorescent cells. This difference reflects the difference in the dependence of the two phenotypes on cellular energy status.

To further test the dual marker system, we examined the GFP and luciferase phenotypes under conditions where the cellular energy reserves are depleted; i.e., starvation conditions in liquid culture and incubation in soil. These conditions are particularly important for environmental applications since bacteria in nature are normally nutrient limited and therefore have low energy reserves.

We found that there was a rapid decline in luminescence during the first days of starvation in liquid culture, presumably due to a shortage of reducing equivalents required for the luciferase reaction. The decrease in luminescence could also be a result of protein degradation. In either case, the loss of luciferase activity indicates a low metabolic activity in the cell population. Although luciferase activity was useful for determination of the energy status of cells, the number of cells and the light yield (expressed as quanta per second) were not correlated and the luminescence data was not a reasonable indicator of cell biomass when the cells were starved.

By contrast, GFP-fluorescent cells could be detected and quantitated at high levels during the entire starvation period. The stability of the GFP fluorescence may partly be explained by examination of the GFP crystal structure, which reveals that the protein itself is very stable (21, 32). We also found that the numbers of culturable cells and of GFP-fluorescent cells counted in the flow cytometer were highly correlated for both tagged strains. However, although cell counts by both methods were very similar for the E. coli strain, the values obtained by flow cytometry were always higher for the P. fluorescens cells, by approximately 1 order of magnitude, than those obtained by plate counting. This difference could be due either to dead cells or to viable but nonculturable cells that can still be detected by GFP fluorescence. Our hypothesis is that GFP is retained inside cells as long as the cell membrane is intact, regardless of the cells’ viability. In a preliminary study, we found that P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp/lux cells lost GFP fluorescence after being heated at 50°C, a temperature at which GFP is known to be stable (4), while similarly treated E. coli DH5α::gfp/lux retained GFP fluorescence. The difference observed between the strains during starvation or heat treatment could be due to differences in the integrity of their cell membranes under these conditions. We are currently performing further investigations to define when GFP-tagged cells become nonfluorescent.

The goal of this monitoring strategy is to eventually track specific tagged cells in environmental samples containing a mixed population of indigenous bacteria. Environmental samples, such as soil, introduce a much greater degree of sampling difficulty due to their complexity compared to pure culture. In particular, soil samples are not amenable to analysis by flow cytometry due to interference from soil particles and cell binding to particulate material (22). Therefore, we modified a Nycodenz density gradient procedure for extraction of bacterial cells from soil samples before further analysis of the specific gfp-luxAB-tagged cells in the samples by flow cytometry. Nycodenz has previously been shown to selectively separate bacteria from soil samples on the basis of differences in density (2). Addition of PVPP prior to the Nycodenz density gradient centrifugation was found to further decrease interference from soil constituents, such as humic material, while increasing the efficiency of extraction of bacteria from the soil. The number of P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp/lux cells extracted by this protocol was high, greater than 70%. The bacterial fraction isolated from nonsterile soil was sufficiently free from soil debris to be directly injected into the flow cytometer, but at cell densities below 105 gfp-tagged cells g of soil−1, interfering fluorescent material extracted from the soil masked detection of GFP-fluorescing cells. This detection limit may be improved by incorporation of additional fractionation steps. The ability to directly enumerate cells by flow cytometry is advantageous over conventional methods of enumeration since flow cytometry counts individual cells, provides statistical data on the specific population, is rapid, and does not rely on culturability for detection.

The metabolic activity of the P. fluorescens SBW25::gfp/lux cells declined during long-term incubation in soil samples (Fig. 6), indicating nutrient limitation. The decline was not as dramatic as that following abrupt introduction to starvation conditions in pure culture (Fig. 5). This difference could be due to the presence of some available nutrients in the soil at the beginning of the incubation period. Also, the density of inoculation was very high in the soil, which could also be a factor in maintenance of an active population due to cryptic growth.

The initial decline in luciferase activity per cell, calculated by comparison of the number of fluorescent cells counted to the luciferase activity of the population, may be an artifact. This effect could be due either to partitioning of elongated cells without a corresponding increase in metabolic activity or to mechanical disruption of log-phase cells during vortexing, resulting in a difference in the yield of bacteria extracted at time zero, compared to later sampling days.

Clearly, there was a marked distinction between the observed phenotypes of the GFP and luciferase biomarkers in cells incubated in soil and under starvation conditions, indicating differences in the properties quantitated by these two biomarkers. The combination of these marker genes was found to be useful for simultaneous monitoring of cell population activity, by luciferase activity measurements, and of total cell numbers, by enumeration of GFP-fluorescing cells. This marker combination also allows the average luciferase activity per cell to be determined. In addition, since the two biomarkers are under the control of the same promoter and GFP fluorescence is independent of cellular energy status, GFP fluorescence can be used as an internal control for luciferase expression. This dual marker system could therefore also be coupled to the study of expression of bacterial promoters in environmental samples. In a recent study, a different approach was taken based on coupling of gfp to a specific promoter as a reporter of gene activity with simultaneous detection of the specific cells with fluorescence-labelled 16S rRNA targeted probes (20). This approach is also useful for analysis of structure-function relationships of microbial communities, although some sample manipulation is required for the 16S rRNA probes (20).

The methods used in this study, luminometry and flow cytometry, are rapid and simple to use and do not depend on cell culturability or sample manipulation. These detection methods should be easily adoptable as standard assays in most laboratories, although the cost of the equipment may be prohibitive. Studies based on this dual marker system are expected to be important for monitoring of total viable cell numbers and metabolic activity of specific bacteria in complex environments, especially for bacteria that are normally difficult to track by conventional methods. Additionally, the ability to directly visualize gfp-luxAB-tagged single cells in environmental samples in situ is an attainable goal for the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was sponsored by the Carl Tryggers Foundation, the Swedish Research Council for Engineering Sciences, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, and the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailey M J, Lilley A K, Thompson I P, Rainey P B, Ellis R J. Site directed chromosomal marking of a fluorescent pseudomonad isolated from the phytosphere of sugar beet; stability and potential for marker gene transfer. Mol Ecol. 1995;4:755–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.1995.tb00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakken L R, Lindahl V. Recovery of bacteria cells from soil. In: Trevors J T, van Elsas J D, editors. Nucleic acids in the environment: methods and applications. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1995. pp. 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloemberg G V, O’Toole G A, Lugtenberg B J J, Kolter R. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for Pseudomonas spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4543–4551. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4543-4551.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bokman S H, Ward W W. Renaturation of Aequorea green-fluorescent protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1981;101:1372–1380. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)91599-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward W W, Prasher D C. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duncan S, Glover L A, Killham K, Prosser J I. Luminescence-based detection of activity of starved and viable but nonculturable bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1308–1316. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.4.1308-1316.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elhai J. Strong and regulated promoters in the cyanobacterium Anabaena PCC 7120. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;114:179–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferguson Y, Glover L A, McGillivray D M, Prosser J I. Survival and activity of lux-marked Aeromonas salmonicida in seawater. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3494–3498. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.9.3494-3498.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heim R, Prasher D C, Tsien R Y. Wavelength mutations and posttranslational autoxidation of green fluorescent protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12501–12504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herrero M, de Lorenzo V, Timmis K. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6557–6567. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6557-6567.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill P J, Swift S, Stewart G S A B. PCR based gene engineering of the Vibrio harveyi lux operon and the Escherichia coli trp operon provides for biochemically functional native and fused gene products. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;226:41–48. doi: 10.1007/BF00273585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holben W E, Jansson J K, Chelm B K, Tiedje J M. Probe method for the detection of specific microorganisms in the soil bacterial community. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:703–711. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.3.703-711.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jansson J K. Tracking genetically engineered microorganisms in nature. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1995;6:275–283. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(95)80048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jansson J K, Prosser J. Quantification of the presence and activity of specific microorganisms in nature. Mol Biotechnol. 1997;7:103–120. doi: 10.1007/BF02761746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindow S E. The use of reporter genes in the study of microbial ecology. Mol Ecol. 1995;4:555–566. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meikle A, Killham K, Prosser J I, Glover L A. Luminometric measurement of population activity of genetically modified Pseudomonas fluorescens in the soil. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;99:217–220. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90029-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meikle A, Glover L A, Killham K, Prosser J I. Potential luminescence as an indicator of activation of genetically-modified Pseudomonas fluorescens in liquid culture and in soil. Soil Biol Biochem. 1994;26:747–755. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Möller A, Jansson J K. Detection of firefly luciferase-tagged bacteria in environmental samples. Methods Mol Biol. 1998;102:269–283. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-520-4:269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Møller S, Sternberg C, Andersen J B, Christensen B B, Ramos J L, Givskov M, Molin S. In situ gene expression in mixed-culture biofilms: evidence of metabolic interactions between community members. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:721–732. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.2.721-732.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ormö M, Cubitt A B, Kallio K, Gross L A, Tsien R Y, Remington S J. Crystal structure of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein. Science. 1996;273:1392–1395. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5280.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porter J, Deere D, Pickup R, Edwards C. Fluorescent probes and flow cytometry: new insights into environmental bacteriology. Cytometry. 1996;23:91–96. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0320(19960201)23:2<91::AID-CYTO1>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prosser J I. Molecular marker systems for the detection of genetically modified microorganisms in the environment. Microbiology. 1994;140:5–17. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ropp J D, Donahue C J, Wolfgang-Kimball D, Hooley J J, Chin J Y W, Hoffman R A, Cuthbertson R A, Bauer K D. Aequorea green fluorescent protein analysis by flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1995;21:309–317. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990210402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suarez A, Güttler A, Strätz M, Staendener L H, Timmis K N, Guzman C A. Green fluorescent protein-based reporter systems for genetic analysis of bacteria including monocopy applications. Gene. 1997;196:69–74. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson I P, Lilley A K, Ellis R J, Bramwell P A, Bailey M J. Survival, colonization and dispersal of genetically modified Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25 in the phytosphere of field grown sugar beet. Bio/Technology. 1995;13:1493–1497. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tombolini R, Unge A, Davey M E, de Bruijn F J, Jansson J K. Flow cytometric and microscopic analysis of GFP-tagged Pseudomonas fluorescens bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;22:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tombolini R, Jansson J K. Monitoring of GFP tagged bacterial cells. Methods Mol Biol. 1998;102:285–298. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-520-4:285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Unge A, Tombolini R, Möller A, Jansson J K. Optimization of GFP as a marker for detection of bacteria in environmental samples. In: Hastings J W, Kricka L J, Stanley P E, editors. Bioluminescence and chemiluminescence: molecular reporting with photons. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons; 1997. pp. 391–394. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Unge A, Tombolini R, Davey M E, de Bruijn F J, Jansson J K. GFP as a marker gene. In: Akkermans A D L, van Elsas J D, de Bruijn F J, editors. Molecular microbial ecology manual. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. pp. 6.1.13.1–6.1.13.16. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang F, Moss L G, Phillips G N., Jr The molecular structure of green fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:1246–1251. doi: 10.1038/nbt1096-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]