Abstract

Background

Little is known about patient choice in treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE).

Aim

Determine motivators and barriers to using common EoE therapies and describe patient-reported shared decision making (SDM) and satisfaction with treatment.

Methods

We developed and administered a Web-based survey on factors influencing EoE treatment choice, SDM, and satisfaction. Adults with EoE and adult caregivers of pediatric EoE patients were recruited via patient advocacy groups and at two centers. Descriptive statistics of multiple response questions and multivariable logistic regression were performed to identify predictors of SDM and satisfaction with treatment.

Results

A total of 243 adults (mean age 38.7 years) and 270 adult caregivers of children (mean age 9.5 years) completed the survey. Preventing worsening disease was the most common motivator to treat EoE. Barriers to topical steroids were potential side effects, cost, and preferring a medication-free approach. Inconvenience and quality of life were barriers to diet. Potential adverse events, discomfort, and cost were barriers to dilation. Nearly half (42%) of patients experienced low SDM, but those followed by gastroenterologists were more likely to experience greater SDM compared to non-specialists (OR 1.81; 95% CI 1.03–3.15). Patients receiving more SDM were more satisfied with treatment, regardless of provider or treatment type (OR 2.62, 95% CI 1.76–3.92).

Conclusions

Patients with EoE pursue treatment mostly to prevent worsening disease. Common barriers to treatment are inconvenience and financial costs. SDM is practiced most by gastroenterologists, but nearly half of patients do not experience SDM, indicating a substantial area of need in EoE.

Keywords: Symptoms, Outcomes, Barriers, Satisfaction, Treatment preferences

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a recently recognized chronic allergy-mediated inflammatory disease characterized by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and eosinophilic infiltration of the esophagus. Long-term maintenance therapy targeted at the histologic resolution of eosinophilic inflammation and symptoms reduces the risk of esophageal impactions, resulting in a decreased need for esophageal dilation, is associated with improved quality of life, and guidelines suggest that this should be considered for all patients [1–5]. While first-line therapy includes dietary elimination or medications such as proton pump inhibitors (PPI) and topical corticosteroids (TCS), the ideal management strategy is not clear and current practice patterns are heterogeneous [6–10]. Pharmacologic therapies offer short response time and relative ease of use, but daily chronic use can be inconvenient and long-term data to support this approach are sparse. Further, neither PPIs nor TCS are FDA-approved for EoE, and the off-label use of TCS (e.g., fluticasone swallowed inhaler and oral viscous budesonide) can be expensive depending on insurance coverage. There may also be potential and unquantified long-term adverse effects of chronic TCS use. Dietary therapy is an attractive choice to attain drug-free disease control for many patients, but it requires adherence to a strict diet and several endoscopies to identify food triggers. Over time, response rates may also wane due to decreased adherence [11]. Endoscopic dilation can also be a safe and effective method to treat fibrostenotic complications and improve symptoms, but downsides include post-procedural discomfort and requiring periodic retreatments.

Due to likely similar efficacy between different treatment modalities and no direct prospective comparative studies, choosing the optimal treatment strategy can be challenging for both patients and providers [12]. The decision to initiate medications or a dietary approach is a preference-sensitive choice and an ideal setting for shared decision making (SDM) between patients and clinicians. Known to improve healthcare communication and patient participation care decisions, uptake and adherence to treatment, and satisfaction, SDM is the process by which providers and patients work together to decide about interventions based on clinical evidence and the patient’s informed preferences [13, 14]. Current EoE guidelines recommend that the choice of therapy should be individually discussed between the patient and provider, but little is known about the EoE patient experience and how these patients choose and use treatments [1, 15].

We aimed to describe the EoE patient experience around selecting a treatment for EoE by exploring beliefs that motivate and prevent patients from using treatments and shared decision making practices perceived by patients. We hypothesized that ongoing symptoms would be the primary motivator for patients seeking treatment, financial cost would limit the use of topical corticosteroids, and inconvenience would be a barrier to choosing diet therapy. We also hypothesized that shared decision making is poorly experienced by patients initiating EoE treatments.

Methods

Participants

This was a cross-sectional survey study of adult patients with EoE and adult caregivers of pediatric patients with EoE. In order to draw from diverse EoE patient experiences, both adults (≥ 18 years old) and children (< 18 years old) were included. To improve data quality and account for the variable cognitive and communicative skills of children and adolescents, we limited participation to proxy-reporting by an adult caregiver, defined as a parent, guardian, or caretaker of a child with EoE. Participants were recruited via social media and email by patient advocacy groups (PAGs) as well as from two tertiary care centers, the University of Michigan and the University of North Carolina. The Institutional Review Board for the University of Michigan School of Medicine (IRBMED) deemed this research as exempt from review.

Instrument

The survey instrument consisted of 36 questions about knowledge, interactions with providers surrounding decision making for treatment, and attitudes toward standard treatment modalities (see Supplementary Appendix S1). Immediately after knowledge-gauging questions, an educational brief about using three common treatments for EoE was presented within the survey, providing objective information about medications, diet therapy, and endoscopic dilation for the management of EoE. Once completed, participants were not permitted to return to the previous knowledge section or revisit this educational brief as a reference during subsequent sections. The survey was developed by authors with expertise in EoE (JC, JR, ED), and iteratively refined with feedback from leadership of three PAGs (EK, MJS, MS, DM, KS)—Campaign Urging Research for Eosinophilic Disease (CURED), American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders (APFED), and Eosinophilic Family Coalition (EFC). To assess patient knowledge about EoE disease outcomes and treatments, we included 8 questions in the survey for a total maximum score of 15. Answer choices were dichotomized into “agree” and “disagree or do not know” categories for 6 questions and additional points were assigned for every correctly selected multiple response. To assess patient-perceived involvement in the shared decision making process before starting an EoE treatment, we used a validated 9-item shared decision making instrument (SDMQ-9) [16]. These questions included elements of SDM such as being told by a doctor that a decision needed to be made, informed of different treatment options, preference elicitation by a doctor, weighing treatment options with a doctor, and reaching an agreement with a doctor on how to proceed with therapy. The responses were rated on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree), where a higher score indicated greater involvement of the patient in SDM (overall score range: 9–54). Although the dichotomized scoring of the SDM-9-Q has not been previously validated, we dichotomized the variable for the sake of parsimoniously fitting models with outcomes (odds ratios) that are relatively easily interpretable for clinical significance.

Survey Administration

A link to complete the Web-based survey was available on social media and email posts by the PAGs and provided to EoE patients at the universities of Michigan and North Carolina. The survey was administered online using Research Electronic Data Capture (RedCap, Nashville, TN). Participation was voluntary, and no financial incentives were given. Electronic reminder announcements were posted via social media by the PAGs every 1 week for a total of 4 reminders. The data were collected between January 2019 and March 2019. Survey responses were securely stored on the University of Michigan server until analysis.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics of categorical and continuous variables, as well as multiple response questions, were performed. We measured differences between adult and pediatric cohorts using Chi-squared and Student’s t test analysis. Dietary exclusion was defined as six- or four-food elimination diets, or some other dietary restriction. Regular follow-up was defined by seeing the specialty provider at least once per year. We dichotomized the SDM-9 score into “low SDM” (composite score range 9–31) and “high SDM” (composite score range 32–54) and measured associations using logistic regression to identify predictors of shared decision making and satisfaction with treatment. We conducted all data management and analysis using Stata 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and with α = 0.05.

Results

Subjects

Of the 614 responses received, 85 were excluded due to incomplete status, 5 did not indicate the subject’s age, and 3 reported not being previously diagnosed with EoE. Duplicate entries were excluded for 8 subjects. A total of 513 subjects could be analyzed, including 243 (47.4%) adult patients and 270 (52.6%) pediatric patients (< 18 years of age) via an adult caregiver (Table 1). As the survey elicited patients with EoE, 464 (89.6%) subjects had a diagnosis of EoE alone with the remaining minority reporting overlapping eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGIDs) including eosinophilic gastritis (EG), eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE), and eosinophilic colitis (EC). In the adult cohort, 85 (31.5%) reported not having regular specialty care at all, 81 (30.0%) followed only with a gastroenterologist, 20 (7.4%) had regular care with only an allergist, and 84 (31.1%) had regular follow-up with both gastroenterology and allergy specialists. In contrast, a large majority of the pediatric cohort (170, 70.0%) had regular follow-up with both gastroenterology and allergy, 61 (25.1%) followed only with a gastroenterologist, 8 (3.3%) with only an allergist, and 4 (1.7%) with neither subspecialist. Almost half (251, 48.9%) of subjects reported currently using some dietary exclusion as primary therapy for EoE, 119 (23.2%) using both topical corticosteroids and dietary exclusion, 49 (9.5%) using topical corticosteroid alone, 43 (8.4%) PPI, and 22(4.3%) not using any therapies to manage their EoE. The remaining 11 (2.1%) were using only endoscopic dilation or nonstandard treatments.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Adults (n = 270) | Children (n = 243) | Total (n = 513) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean years, SD) | 38.7 (12.1) | 9.5 (4.5) | 24.9 (17.3) |

| Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders | |||

| EoE only | 246 (91.1%) | 218 (89.7%) | 464 (89.6%) |

| Also EG | 13 (4.8%) | 10 (4.1%) | 23 (4.5%) |

| Also EGE | 9 (3.3%) | 9 (3.7%) | 18 (3.5%) |

| Also EC | 4 (1.5%) | 9 (3.7%) | 13 (2.5%) |

| Diagnosis made | |||

| < 1 year ago | 41 (15.2%) | 55 (22.6%) | 96 (18.7%) |

| 1–3 years ago | 96 (35.6%) | 101 (41.6%) | 197 (38.4%) |

| 4–6 years ago | 64 (23.7%) | 46 (18.9%) | 110 (21.4%) |

| 7–10 years ago | 39 (14.4%) | 27 (11.1%) | 66 (12.9%) |

| > 10 years ago | 30 (11.1%) | 13 (5.4%) | 43 (8.4%) |

| Current therapy | |||

| None | 25 (9.3%) | 4 (1.6%) | 29 (5.7%) |

| PPI | 35 (13.0%) | 8 (3.3%) | 43 (8.4%) |

| TCS | 22 (8.1%) | 27 (11.1%) | 49 (9.5%) |

| Diet exclusion | 131 (48.5%) | 120 (49.4%) | 251 (48.9%) |

| TCS + diet | 44 (16.3%) | 75 (30.9%) | 119 (23.2%) |

| H2RA only | 5 (1.8%) | 0 | 5 (1.0%) |

| Dilation alone | 1 (0.4%) | 0 | 1 (0.2%) |

| Other | 7 (2.6%) | 9 (3.7%) | 16 (3.1%) |

EoE eosinophilic esophagitis, EG eosinophilic gastritis, EGE eosinophilic gastroenteritis, EC eosinophilic colitis

Knowledge

A total of 8 knowledge questions were included for analysis. Knowledge scores were not statistically different between the adult (mean score 10.3) and pediatric (mean score 10.4) groups.

Motivators to Treating EoE

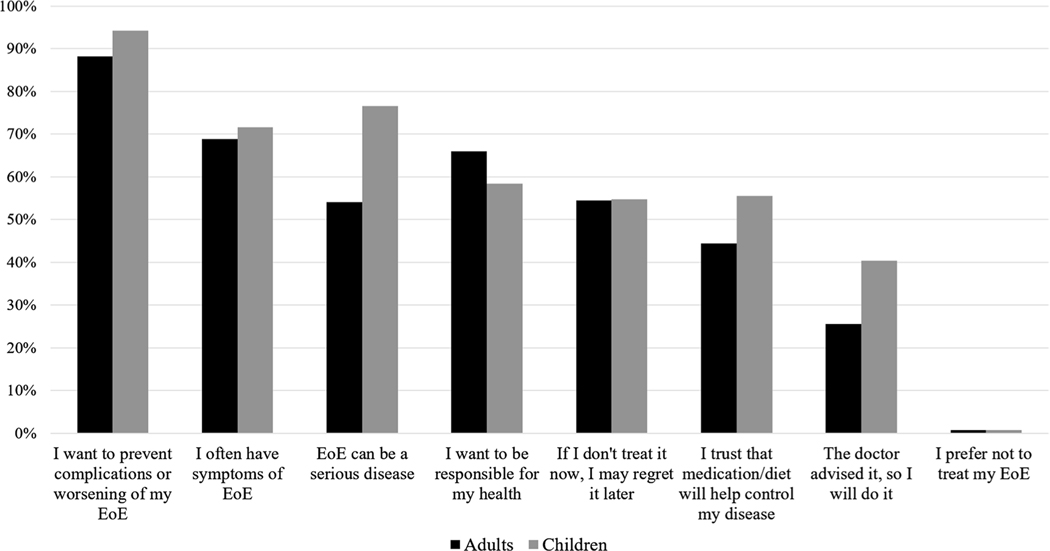

To explore reasons why patients are motivated to seek treatment for EoE, subjects were asked “why would you be willing to use any treatment for EoE?” and prompted to select as many reasons that apply (Fig. 1, Supplemental Figs. 3 and 4). The most common motivator to treat EoE was a desire to prevent complications or worsening disease (88.2% adults, 94.2% peds). Other common responses included having symptoms, belief that EoE is a serious disease, responsibility for ones’ own health, and forecasting future regret if left untreated. Only half of the adult respondents felt that EoE could be a serious disease (54.1% vs 76.5% peds), and 44.4% (55.6% peds) had trust that medications or diet could control it. Additionally, only 25.6% of adult respondents reported that a doctor’s advice to treat EoE would motivate them toward pursuing therapy. Comparisons between adult and pediatric groups were performed and it was found that more children (via adult caregivers) were willing to start treatment because statistically significant differences between the two groups in responses “I want to prevent complication of worsening of my EoE” (peds 94.2% vs adults 88.2%, p = 0.016), “EoE can be a serious disease” (peds 76.5% vs adults 54.1%, p = 0.00), “I trust that medication or diet will help to control my disease” (peds 55.6 vs adults 44.4%, p = 0.012), and “the doctor advised it, so I will do it” (peds 40.3% vs adults 25.6%, p = 0.00). Frequent symptoms (peds 71.6% vs adults 68.9%, p = 0.50) and a sense of responsibility (peds 58.4% vs adults 65.9%, p = 0.08) as motivators to treat EoE were not significantly different between adult and pediatric patients.

Fig. 1.

Patient willingness to treat EoE

Patient Barriers to Using EoE Treatments

Regardless of current or past experiences with treatment, subjects were asked about reasons they would not choose to use TCS, elimination diet, and endoscopic dilation to manage their EoE. The greatest barriers to electing topical steroids were potential side effects (58.2% adults, 63.4% peds), financial cost (34.1% adults, 19.3% peds), and preference for a medication-free or natural approach (24.8% adults, 25.9% peds) (Fig. 2, Supplemental Figs. 3 and 4). The inconvenience of adhering to a restrictive diet (36.3% adults, 27.6% peds), undergoing multiple endoscopies (30.4% adults, 26.8% peds), poor quality of life and socialization (23.7% adults, 27.6% peds), and inadequate nutrition (28.4% peds) were common barriers to diet therapy. The beliefs that endoscopic dilation is a high-risk procedure (30.7% adults, 36.6% peds), discomfort (30.4% adults, 27.6% peds), and financial cost (31.1% adults, 20.6% peds) were reasons subjects would avoid dilation to treat EoE. Additionally, 24.4% of adults felt that they would avoid dilation because of inconveniences around having a procedure (e.g., having transportation and taking off work). More adults were concerned with the financial costs of medication (adults 34.1% vs peds 19.3%, p = 0.00), inconvenience of restrictive diet (adults 36.3% vs peds 27.6%, p = 0.04), access to a dietician (adults 11.5% vs peds 3.3%, p = 0.00), financial costs of repeated procedures (adults 31.1% vs peds 20.6%, p = 0.01), and inconvenience of having a procedure (adults 24.4% vs peds 9.1%, p = 0.00) compared to children. Fewer adults had no concerns about starting a diet therapy (adults 33.3% vs peds 42.4%, p = 0.04). More caregivers of pediatric patients viewed inadequate nutrition (adults 17.0% vs peds 28.4%, p = 0.00) as a barrier to diet therapy. More adults had no concerns about dilation (adults 30.7% vs peds 22.6%, p = 0.04) and more caregivers of children felt they had inadequate information about dilation (adults 7.4% vs peds 16.1%, p = 0.00).

Fig. 2.

Patient barriers to EoE treatments

Shared Decision Making

Overall, 217 (42.3%) of respondents reported experiencing low SDM around EoE treatments before starting therapy (mean SDM-9-Q score 33.28, SD 13.50, median 34, range 22–45). Among adults, 44.4% reported low SDM (mean SDM-9-Q score 32.04, SD 13.85, median 33, range 19–43). In the pediatric cohort, 39.9% reported low SDM (mean SDM-9-Q score 34.66, SD 12.99, median 36, range 25–45). Patients followed by GI providers were more likely to experience greater SDM compared to non-specialists (OR 1.81; 95% CI 1.03–3.15), with similar result for both adults and adult caregivers of children. To assess patient-perceived provider comfort with treatments, respondents were asked how comfortable their doctor would be if they wanted to try a therapy outside of the physician’s recommendation. Among adult subjects, 118 (43.7%) reported that their provider would feel comfortable with trying a therapy outside of their recommendation, 51 (18.9%) felt that their providers would be uncomfortable, and 101 (37.4%) were unsure how their doctor would feel. Among adult caregivers of pediatric patients, 111 (45.7%) indicated that their provider would feel comfortable with their treatment choices, 67 (27.6%) uncomfortable, and 64 (26.3%) were unsure. More SDM occurred when patients perceived providers as comfortable with choosing a therapy outside of their recommendation (Table 2). Higher knowledge score was not significantly associated with high SDM (unadjusted OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.90–1.08; adjusted OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.91–1.11). Comparing adult and pediatric cohorts, adults did not experience more SDM compared to children (unadjusted OR 1.20, CI 0.88–1.71; adjusted OR 1.09, CI 0.71–1.65). Comparing adult and pediatric SDM, there was no difference in SDM when treated as a dichotomous variable. When composite SDM score was treated as a continuous variable, there were statistically significant differences with more SDM in the pediatric cohort (pediatric mean score 35 vs adult mean score 32), but these are unlikely to be clinically significant. Analysis measuring associations with shared decision making for patients with overlapping EGIDs was limited by the small number of observations; however, Chi-squared and t test comparisons revealed that there was no statistically significant difference in SDM composite or dichotomized SDM scores between EoE-only and overlapping EGID groups.

Table 2.

Associations with shared decision making (SDM)

| Low SDM, N (%) | High SDM, N (%) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Mutually adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider type | ||||

| No specialist | 46 (51.7%) | 43 (48.3%) | (Reference) | (Reference) |

| GI only | 52 (36.6%) | 90 (63.4%) | 1.85 (1.08, 3.17) | 1.81 (1.03, 3.15) |

| Allergy only | 18 (64.3%) | 10 (35.7%) | 0.59 (0.25, 1.43) | 0.57 (0.23, 1.42) |

| GI + allergy | 101 (39.8%) | 153 (60.2%) | 1.62 (1.00, 2.63) | 1.54 (0.93, 2.56) |

| Patient-perceived provider comfort with electing other treatments | ||||

| Comfortable | 72 (31.4%) | 157 (68.6%) | (Reference) | (Reference) |

| Uncomfortable | 70 (59.3%) | 48 (40.7%) | 0.31 (0.20, 0.50) | 0.31 (0.20, 0.50) |

| Unsure | 75 (45.5%) | 90 (54.6%) | 0.55 (0.36, 0.83) | 0.58 (0.92, 2.51) |

Provider comfort: Patient-perceived provider comfort with the patient’s decision to use a therapy outside of their recommendation

Satisfaction with Treatment

Only 103 (38.1%) adults felt satisfied with their current treatment, 76 (28.1%) felt dissatisfied, and 91 (33.7%) felt neither and were indifferent to their current treatment. Conversely, 132 (54.3%) of adult caregivers of children with EoE felt satisfied, 64 (26.3%) felt dissatisfied, and only 47 (19.3%) felt indifferent about their child’s current treatment. Adjusting for provider type, current treatment, and perceived provider comfort about therapy choice, multivariate logistic regression revealed that patients who perceived more SDM with their doctor about EoE care were more satisfied with their current EoE treatment for both adults and adult caregivers of pediatric patients (OR 2.62, 95% CI 1.76–3.92; Table 3). Satisfaction with current treatment did not differ significantly by provider type. To assess the effect of “hybrid therapy” with concurrent PPI or dilation on patient satisfaction, sensitivity analysis restricted to medication or diet monotherapy against hybrid therapy regimens revealed satisfaction was not greater with concomitant hybrid therapies regimens (OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.60–1.35). Compared to hybrid therapies, increased satisfaction was also not significantly associated with PPI monotherapy (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.42–1.82), topical steroid monotherapy (OR 1.82, 95% CI 0.70–4.71), or diet monotherapy (OR 1.08, 95% CI 0.68–1.72). Analysis measuring associations with satisfaction for patients with overlapping EGIDs was limited by the small number of observations.

Table 3.

Associations with satisfaction of treatment

| Satisfied | Unsatisfied or indifferent | Mutually Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDM composite | |||

| Low SDM | 66 (30.4%) | 151 (69.6%) | (Reference) |

| High SDM | 169 (57.1%) | 127 (42.9%) | 2.62 (1.76, 3.92) |

| Provider type | |||

| No specialist | 26 (29.2%) | 63 (70.8%) | (Reference) |

| GI only | 74 (52.1%) | 68 (47.9%) | 1.97 (1.04, 3.72) |

| Allergy only | 12 (42.9%) | 16 (57.1%) | 1.52 (0.58, 4.03) |

| GI + allergy | 123 (48.4% | 131 (51.6%) | 1.66 (0.91, 3.03) |

| Patient-perceived provider comfort with electing other treatments | |||

| Comfortable | 118 (51.5%) | 111 (48.5%) | (Reference) |

| Uncomfortable | 54 (45.8%) | 64 (54.2%) | 1.04 (0.63, 1.70) |

| Unsure | 63 (38.2%) | 102 (61.8%) | 0.68 (0.44, 1.07) |

| Current treatment | |||

| No therapy | 3 (10.3%) | 26 (89.7%) | (Reference) |

| PPI only | 18 (41.9%) | 25 (58.1%) | 3.92 (0.98, 15.70) |

| TCS only | 27 (55.1%) | 22 (44.9%) | 5.96 (1.50, 23.77) |

| Diet only | 126 (50.2%) | 125 (49.8%) | 5.22 (1.46, 18.61) |

| TCS + diet | 55 (46.2%) | 64 (53.8%) | 4.33 (1.16, 16.17) |

Provider comfort: Patient-perceived provider comfort with the patient’s decision to use a therapy outside of their recommendation

Discussion

Both elimination diet and medications such as PPI and TCS are effective EoE treatments to attain symptomatic and histologic disease remissions. The ideal treatment strategy is a preference-sensitive choice ripe for shared decision making, but little is known about factors driving treatment choice and how SDM is experienced by patients. In this patient survey study, we found that patients were most motivated by preventing worsening disease and their symptoms to seek treatment; however, only half trusted that medications or diet could control their disease. Common reasons that patients avoid medication or diet therapy include inconvenience and financial cost. Patients with regular gastroenterology care experienced more SDM and are more likely to be satisfied with any treatment when it is practiced, but many patients still receive little SDM around EoE treatment. These findings highlight the need for providers to recognize the challenges of the disease and available treatments, incorporate patient preferences and values toward tailored therapy plans, and promote SDM methods as a vital next step in patient-centered EoE care.

Our results echo what is known about barriers that patients encounter with EoE treatments. In a recent survey of patients with eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases, Hiremath et al. [17] described that repeated endoscopies were convenient and affordable for only a minority of patients. Additionally, only a minority of patients on diet therapy (31%) and swallowed steroids (48%) felt that adherence was easy and convenient. A previous study showed that adherence to a six-food elimination diet costs $650/year in excess compared to an unrestricted diet and increased shopping burden as it required patients to shop at more than one grocery store [18]. In exploring patient motivators for treatment, a survey of Swiss EoE patients reported that over 90% prioritize improvement of symptoms and quality of life as treatment goals, with less importance placed on reducing inflammation and fibrosis [19]. Although quality of life (QoL) is strongly correlated with EoE symptom severity and endoscopic activity, to our knowledge, there are no studies specifically assessing outcomes by levels of SDM [5]. A similar survey showed that Swiss EoE patients consider effect on symptoms (89%) as the most important consideration for the choice of therapy [20]. After this, the effect of inflammation (76%), potential side effects (69%), ease of use (58%), physician’s recommendation (50%), compatibility with lifestyle (46%), and price (19%) were considered less important. In contrast, a desire to prevent complications or worsening disease was the most common reason to seek treatment in our American cohort and for our adults, symptoms and a sense of responsibility for one’s own health were second to this. This perhaps sheds light on our patient population’s understanding of disease chronicity and potential complications of untreated disease and may also reflect cultural differences in healthcare delivery and how information is presented to patients in a survey or educational materials. Safroneeva et al. also found that EoE patients on PPI, TCS, and diet therapy for at least 1 year were overall satisfied with all three treatments. This difference from our findings may be due to increased satisfaction with long-term use, provider effects, and access to healthcare resources. This also broadens our current understanding of the diverse factors in the decision to pursue and maintain treatment, and perhaps conversely, what influences non-adherence or refusal to therapy.

Characterizing and comparing treatment patterns among adult and pediatric EoE patients, we found that adults are more likely to be untreated or use PPI and children are more likely to undergo combination topical steroid and diet regimens. There are several possible explanations for this including how adult patients make tradeoffs between treatments and symptoms, and the perceived safety of PPIs. Diagnostic delay and compensatory adaptive eating behaviors are well documented in adults with EoE and may suggest that adults weigh the inconveniences of treatment and diagnosis over potential risks of active disease. As a widely accepted medication for the management of reflux disease and previously recommended as first-line trial for EoE, PPIs are considered safe, easy to use, and inexpensive, which could explain why patients are more willing to use it and why providers prescribe it more often. In the pediatric population, parents or adult caregivers may be motivated to achieve disease control sooner with aggressive treatments in order to prevent future complications or disease progression. However, our study was not designed to examine differences in reasons to choose various pharmacologic treatments.

Given the similar efficacies of standard EoE treatments and lack of comparative effectiveness trials, shared decision making is commonly advocated as best way to approach treatment selection. Our findings using a validated SDM instrument estimate less SDM compared to previous work by Hiremath et al. [17], where a majority of patients and adult caregivers felt that their medical team sought their input about care decisions. Potential reasons for poorly perceived or practiced SDM may include inadequate patient knowledge, patient-provider communication barriers, discomfort with SDM in either patients or providers, and weighing preferences for therapy. In the existing SDM literature, barriers to implementing SDM in practice include concerns for insufficient in-clinic time, lack of provider motivation, provider beliefs that they are already practicing SDM, and uncertainty in treatment decisions. Our current findings that more SDM occurs when providers are comfortable with patients choosing a therapy outside of their recommendation complements our provider survey demonstrating that many are uncomfortable with allowing patients to do so, highlighting deficits in provider comfort with patient decision making and likely SDM [6]. This is contextualized by a recent study identifying 47% of “SDM skeptic” American gastroenterologists who were less likely to view patients as qualified to participate in treatment decisions for inflammatory bowel disease [21]. External to gastrointestinal diseases, a provider questionnaire found that a majority of Swedish general practitioners (GPs) would not accept a patient’s reluctance toward having a medically motivated intervention and older GPs were more inclined to persuade the patient to pursue surgery [22]. Our results that SDM was not better experienced with multiple specialists bring to light variations in education provided by providers. In our previous work, we showed that among practicing gastroenterologists, little time is spent providing education and counseling during initial encounters for EoE (47% spend less than 10 min, 44% spend 10–15 min) and only 70% reported that they always provide education and counseling on treatment options and expected disease course (e.g., symptoms, future procedures) at the initial visit [6]. As prior provider survey studies among adult and pediatric gastroenterologists, and allergists have demonstrated, provider practices around recommendations for initial therapy and monitoring response to therapy are heterogeneous and not necessarily adherent to the published clinical guidelines [7, 9, 10, 23, 24]. With incongruous recommendations and a lack of quality in patient education and counseling, management with multiple providers or specialists does not guarantee better disease outcomes, and in some instances, may be a hindrance to informed and shared decision making.

This is the first study to specifically examine shared decision making around EoE treatment choices, but there are strengths and limitations to acknowledge. We targeted EoE patients both in two academic clinical practices and the online EoE community, which allowed for diverse recruitment and a large sample size of both adult and pediatric patients. Additionally, we used patient participatory research methods by engaging patient advocacy groups in the development and dissemination of the survey instrument. Similar to prior patient surveys, we included an educational brief prior to questions about factors impacting treatment choices. Because of our diverse recruitment method, participants’ knowledge base was likely disparate and gained from providers, peers, and online resources, if at all. This objective education section was framed to minimize variation and response bias to subsequent questions assessing motivators and barriers to treatment, presented only after participants completed questions measuring knowledge. A major limitation of this study is the recruitment of patients who may be more engaged in their own medical care with active participation in these groups, which may introduce potential bias and affect generalizability of our results. Our data did not distinguish how individual subjects were invited to enroll and which advocacy groups they belonged to, if any. In our patient sample, diet exclusion was the most common current therapy, which may bias responses to barriers to choosing pharmacologic therapies. The study was also limited to American patients and may not reflect perspectives in other countries where financial costs of medications and procedures may vary. We recognize that pediatric SDM experiences may vary from those of adult patients due to the child-caregiver relationship and attempted to capture these differences by eliciting responses from adult caregivers. However, similar responses to motivators to treat EoE and overall SDM between the two groups could possibly be due to the adult proxies describing experiences and considering preferences as adults, instead of as children. This point may also apply in the assessment of patient knowledge base as there were no differences in knowledge scores between the two groups. Higher knowledge score was not found to be associated with SDM which is unexpected because knowledge building is known to positively affect high-quality decision making [25]. However, this may be due to the use of unvalidated questions and lack of validated EoE-specific knowledge instruments. We cannot estimate a formal response rate, as a denominator cannot be calculated when social media recruitment techniques are used. In the context of these potential biases, our findings that nearly half of this selective cohort experiences low SDM may in fact overestimate how the average EoE patient perceives SDM around treatment choices. Although we demonstrated variations in perspectives about treatments and that SDM is poorly experienced, our survey does not explore deeper reasons for these attitudes or deficits in SDM and further patient-focused methods and studies addressing patient-provider decision practices are necessary to capture a comprehensive view of the EoE patient experience. Although understanding why prior treatments were initiated or discontinued would shed light on patient perceptions of treatment options, our survey was not designed to extract this data. Furthermore, because of the cross-sectional study design, we are unable to draw conclusions on if patient perceptions about the treatment were due to previous treatment experiences or preconceived to cause a selection effect.

In summary, this patient survey showed that preventing complications and worsening disease are the most important factors in pursuing treatment and common barriers include inconvenience and financial costs. Perception of SDM surrounding EoE is highest when care is provided by a gastroenterologist and when patients perceive there to be provider comfort with various treatment options, although overall SDM scores are low suggesting that EoE patients do not consistently feel strong participation in decisions regarding their disease management. Because patients are more likely to be satisfied with any treatment when SDM is practiced, improving patient-focused communication and facilitating SDM are pivotal next steps in providing patient-centered care. Shared decision making is also known to improve patient-provider communication, engagement, and reduced decisional conflict, so future prospective studies are needed to validate if SDM in EoE improves these affective-cognitive outcomes as well as distal clinical outcomes such as long-term adherence to therapy, disease activity control, endoscopic utilization, and prevention of complications [14]. As SDM requires access to evidence-based knowledge and the means to deliver it, providers need to recognize the challenges of both the disease and treatments, provide detailed disease-related education, elicit patient preferences, and tailor therapy plans to individual attitudes and values.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the patient advocacy groups (Campaign Urging Research for Eosinophilic Disease, American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders, and Eosinophilic Family Coalition) and thank all of the participants who contributed to this study.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest JHR: No potential conflicts of interest related to this paper. Dr. Rubenstein has received research funding from Takeda. ESD: No potential conflicts of interest related to this paper. Dr. Dellon has received rsearch funding from Adare, Allakos, GSK, Meritage, Miraca, Nutricia, Celgene/Receptos, Regeneron, Shire/Takeda; has received consulting fees from Abbott, Adare, Aimmune, Allakos, Arena, AstraZeneca, Biorasi, Calypso, Celgene/Receptos, Eli Lilly, EsoCap, GSK, Gossamer Bio, Regeneron, Robarts, Salix, Shire/Takeda, and educational grants from Allakos, Banner, and Holoclara. None of the other co-authors report any relevant disclosures or potential conflicts of interest.

Guarantor of the article Joy W. Chang.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-020-06438-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, et al. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:679–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, et al. Updated international consensus diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: proceedings of the agree conference. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1022–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greuter T, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, et al. Maintenance treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis with swallowed topical steroids alters disease course over a 5-year follow-up period in adult patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:419–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuchen T, Straumann A, Safroneeva E, et al. Swallowed topical corticosteroids reduce the risk for long-lasting bolus impactions in eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy. 2014;69:1248–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Safroneeva E, Coslovsky M, Kuehni CE, et al. Eosinophilic oesophagitis: relationship of quality of life with clinical, endoscopic and histological activity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:1000–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang JW, Saini SD, Mellinger JL, Chen JW, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Rubenstein JH. Management of eosinophilic esophagitis is often discordant with guidelines and not patient-centered: results of a survey of gastroenterologists. Dis Esophagus. 2019;32(6):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King J, Khan S. Eosinophilic esophagitis: perspectives of adult and pediatric gastroenterologists. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:973–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miehlke S, von Arnim U, Schlag C, et al. Clinical management of eosinophilic esophagitis—a nationwide survey among gastroenterologists in Germany. Z Gastroenterol. 2019;57:745–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peery AF, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Practice patterns for the evaluation and treatment of eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1373–1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spergel JM, Book WM, Mays E, et al. Variation in prevalence, diagnostic criteria, and initial management options for eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases in the United States. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:300–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang R, Hirano I, Doerfler B, Zalewski A, Gonsalves N, Taft T. Assessing adherence and barriers to long-term elimination diet therapy in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:1756–1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cotton CC, Eluri S, Wolf WA, Dellon ES. Six-food elimination diet and topical steroids are effective for eosinophilic esophagitis: a meta-regression. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:2408–2420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glass KE, Wills CE, Holloman C, et al. Shared decision making and other variables as correlates of satisfaction with health care decisions in a United States national survey. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88:100–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shay LA, Lafata JE. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Making. 2015;35:114–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lucendo AJ, Molina-Infante J, Arias A, et al. Guidelines on eosinophilic esophagitis: evidence-based statements and recommendations for diagnosis and management in children and adults. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2017;5:335–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kriston L, Scholl I, Holzel L, Simon D, Loh A, Harter M. The 9-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire (SDM-Q-9). Development and psychometric properties in a primary care sample. Patient Educ Couns.. 2010;80:94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiremath G, Kodroff E, Strobel MJ, et al. Individuals affected by eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders have complex unmet needs and frequently experience unique barriers to care. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2018;42:483–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolf WA, Huang KZ, Durban R, et al. The six-food elimination diet for eosinophilic esophagitis increases grocery shopping cost and complexity. Dysphagia. 2016;31:765–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safroneeva E, Balsiger L, Hafner D, et al. Adults with eosinophilic oesophagitis identify symptoms and quality of life as the most important outcomes. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48:1082–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Safroneeva E, Hafner D, Kuehni CE, et al. Systematic assessment of adult patients’ satisfaction with various eosinophilic esophagitis therapies. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2019;181:211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siegel CA, Lofland JH, Naim A, et al. Gastroenterologists’ views of shared decision making for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:2636–2645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bremberg S, Nilstun T. Patients’ autonomy and medical benefit: ethical reasoning among GPs. Fam Pract. 2000;17:124–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eluri S, Iglesia EGA, Massaro M, Peery AF, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Practice patterns and adherence to clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management of eosinophilic esophagitis among gastroenterologists. Dis Esophagus. 2020;33:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang KZ, Jensen ET, Chen HX, et al. Practice pattern variation in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis in the carolinas EoE collaborative: a research model in community and academic practices. South Med J. 2018;111:328–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawley ST, Li Y, An LC, et al. Improving breast cancer surgical treatment decision making: the iCanDecide randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol.. 2018;36:659–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.