Abstract

The halophilic methanoarchaeon Methanohalophilus portucalensis can synthesize de novo and accumulate β-glutamine, Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine, and glycine betaine (betaine) as compatible solutes (osmolytes) when grown at elevated salt concentrations. Both in vivo and in vitro betaine formation assays in this study confirmed previous nuclear magnetic resonance 13C-labelling studies showing that the de novo synthesis of betaine proceeded from glycine, sarcosine, and dimethylglycine to form betaine through threefold methylation. Exogenous sarcosine (1 mM) effectively suppressed the intracellular accumulation of betaine, and a higher level of sarcosine accumulation was accompanied by a lower level of betaine synthesis. Exogenous dimethylglycine has an effect similar to that of betaine addition, which increased the intracellular pool of betaine and suppressed the levels of Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine and β-glutamine. Both in vivo and in vitro betaine formation assays with glycine as the substrate showed only sarcosine and betaine, but no dimethylglycine. Dimethylglycine was detected only when it was added as a substrate in in vitro assays. A high level of potassium (400 mM and above) was necessary for betaine formation in vitro. Interestingly, no methylamines were detected without the addition of KCl. Also, high levels of NaCl and LiCl (800 mM) favored sarcosine accumulation, while a lower level (400 mM) favored betaine synthesis. The above observations indicate that a high sarcosine level suppressed multiple methylation while dimethylglycine was rapidly converted to betaine. Also, high levels of potassium led to greater amounts of betaine, while lower levels of potassium led to greater amounts of sarcosine. This finding suggests that the intracellular levels of both sarcosine and potassium are associated with the regulation of betaine synthesis in M. portucalensis.

Methanoarchaea, although a metabolically restricted group, exhibit extreme habitat diversity (19). In terms of salinity, methanoarchaea have been isolated from environments with NaCl concentrations ranging from <0.05 M for many nonmarine species to >4 M for halophilic species (2, 31, 40, 42). To survive and adapt to an environment with a fluctuating concentration of changing extracellular solutes, methanoarchaea resemble other microorganisms in that they accumulate low-molecular-weight organic compounds as osmolytes, thereby enabling them to minimize water loss and maintain cell turgor pressure. The mechanisms and functions of osmolytes are still not clear; however, studies have shown that osmolytes can protect enzymes from low water activity caused by the accumulation of solutes (9, 16, 26, 32, 41).

Several osmolytes have been identified in methanogens, including α-glutamate, dimethylglycine, betaine, β-glutamate, β-glutamine, 1,3,4,6-tetracarboxyhexane, Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine, and di-myo-inositol-1,1-phosphate (7, 8, 22, 23, 30, 35, 39). Among these, betaine is a widely adopted osmolyte which has a crucial osmoprotective function in plants, animals, and eubacteria (1, 9, 41). A study by Pollard and Wyn Jones (32) demonstrated that intracellularly accumulated betaine up to 500 mM had no inhibitory effect on the cell. Moreover, their work also showed the ability of betaine to prevent the inhibition by NaCl of malate dehydrogenase activity in Horleum vulgare (32). Uptake or transport of betaine and its precursors as compatible solutes under osmotic stress are common phenomena among many organisms (6, 9, 10, 13, 14, 20, 21, 27, 33). However, only three microorganisms have demonstrated the capability for de novo synthesis of betaine: the halophilic methanogen Methanohalophilus portucalensis FDF1, the extremely haloalkalophilic sulfur bacterium Ectothiorhodospira halochloris, and the salt-tolerant cyanobacterium Aphanothece halophytica (11–13, 22, 34, 36, 38).

Nonhalophilic, marine, and halotolerant methanogens can accumulate and transport betaine as an osmolyte in response to increased external NaCl (22, 33, 39, 40), but they cannot synthesize it de novo. However, the accumulation and de novo synthesis of betaine in M. portucalensis were in response to external salt concentrations (22, 23). In addition to salt effect, the amount of betaine accumulation is also subject to the methanogenesis substrate (36). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopic analysis of 13CH3OH-12CO2 label incorporation by M. portucalensis suggests that the biosynthetic pathway of betaine is through the methylation of glycine, generated from serine (34), in which sarcosine and dimethylglycine serve as the intermediates for betaine synthesis. In this study, we investigate the factors associated with the regulation of betaine synthesis to further elucidate the physiological basis of the osmoregulatory phenomena in the halophilic methanoarchaea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms and growth conditions.

The bacterial strain used in this study was M. portucalensis FDF1 (= OCM59). This strain was isolated from the solar saltern of Figueria da Foz, Portugal, by Mathrani et al. and was provided by R. Mah (4). The cells were routinely cultured in defined medium that contained 120 g of NaCl/liter and 20 mM trimethylamine or 100 mM methanol as the sole carbon and energy source (22). Sterile medium was prepared under a N2-CO2 atmosphere (4:1) by a modification of the Hungate technique (2). The medium was anaerobically dispensed into serum bottles, which were then sealed with butyl rubber stoppers and aluminum crimp closures (Bellco, Inc., Vineland, N.J.). The methanogenic substrates and Na2S · 9H2O were added to the sterile medium just prior to cell inoculation. Sealed serum bottles were inoculated with a 0.5% volume of late-exponential-phase culture by using a N2-flushed syringe. The cells were grown at 37°C, as previously described (22). Cell growth rates were monitored by removing 1 ml of the culture with a N2-flushed syringe into a cuvette containing Na2S2O3 and measuring the optical density of the culture at 540 nm.

Extraction and detection of intracellular osmolytes.

The extraction and detection of intracellular osmolytes were performed as previously described (24). Mid-exponential-phase cultures were centrifuged, and pellets were extracted twice with 1 ml of 70% (vol/vol) ethanol-water by heating for 5 min at 65°C. Pooled extracts were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 5 min, filtered through 0.2-μm-pore-size PTFE membrane filters (Gelman Sciences, Ann Arbor, Mich.), and lyophilized. For analysis of primary amines, dried ethanol cell extracts were dissolved in deionized H2O, applied to a Sep-Pak C18 column (Waters Associates, Milford, Mass.), and eluted with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in water-methanol (7:3). The high-performance liquid chromatography HPLC dual-pump system (Waters Associates) was equipped with a gradient programmer (model 720). The extract (20 μl) was eluted from an anion-exchange column with a linear pH gradient ranging from 3.17 to 9.94. The eluate was monitored after O-phthaldehyde postderivatization with a fluorescence spectrophotometer (excitation at 340 nm and emission at 455 nm). The betaine concentration of ethanol extracts was quantified by the absorbance of the periodide derivative (24). Betaine standards and unknowns were analyzed in triplicate. Cell volumes were determined by measuring the differential retention of [14C]glucose and 3H2O in the cell pellets (24). The average volume of M. portucalensis grown in defined medium containing 12% NaCl was 2.68 × 10−10 μl/cell. Cell counts were determined with a Petroff-Hausser counting chamber and a phase-contrast microscope.

Preparation of anaerobic cell extract.

All steps were anaerobically performed under an atmosphere of N2-CO2 (4:1) and at 4°C. Manipulations were performed in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory, Ann Arbor, Mich.). The cultures were grown to mid-log phase, anaerobically harvested by centrifugation, and then resuspended with buffer A {50 mM TES [N-tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl-2-amino and ethanesulfonic acid], 800 mM KCl, 200 mM glutamic acid, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.2}. The suspended cells were anaerobically broken by one or two passages through a French pressure cell (SLM Instruments Inc., Urbana, Ill.) at 10,000 lb/in2. The cell lysates were collected and anaerobically centrifuged at 18,000 rpm for 30 min. Finally, the supernatant was collected in a serum bottle under nitrogen and stored at −85°C.

In vivo betaine formation test.

Cells were incubated with 20 μCi of [2-14C]glycine (Amersham, Aylesbury, United Kingdom) and anaerobically harvested at mid-log phase. The cells were extracted twice by heating for 5 min at 65°C in 50 ml of 70% (vol/vol) ethanol-water. The ethanol extracts were collected and concentrated by vacuum evaporation and then spotted onto a silica gel 60 thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate (Merck Co., Rahway, N.J.) for glycine, sarcosine, and betaine separation under a methanol-acetone-HCl (9:1:1) solvent system. Authentic betaine, sarcosine, and glycine were used as the standards. After being dried at room temperature, the plate was first stained with iodine vapor, and the brownish-colored spot of betaine (Rf, 0.71) appeared. The iodine stain was then evaporated, and the TLC plate was sprayed with heated 0.2% ninhydrin in isopropanol-pyridine (80:20) to stain sarcosine (Rf, 0.93) pink and glycine (Rf, 0.94) yellow. Finally, radioactivity on the TLC plate was detected by a β-scanner (Ambis Co., San Diego, Calif.).

In vitro betaine formation assay.

Anaerobic crude extracts were incubated with 4.6 mM S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), with or without the addition of 1.0 μCi of [methyl-14C]SAM (Amersham), and 50 mM TES buffer at 37°C for 4 h. KCl, NaCl, and LiCl were added at the indicated concentrations. The substrates selected for the assays were glycine, sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and betaine (2 mM each). After the reactions were stopped, samples were passed through a Dowex 50Wx8 minicolumn (1-ml disposable syringe with 2-cm-high resin) to partially remove proteins and KCl. Then glycine, sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and betaine were eluted with 2 N NH4OH. Samples were concentrated by vacuum evaporation and then spotted onto a silica gel TLC plate (Merck Co.) to separate N-methylamines (glycine, sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and betaine) under a phenol-H2O (4:1) solvent system. The plates were stained with 0.1% bromocresol green. After the dye solution was applied, the plates were dried with hot air to develop the colors. Glycine, sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and betaine appeared as blue spots on a green background, with Rf values of the authentic standards at 0.21, 0.42, 0.58, and 0.65, respectively. Residual proteins and salts in the assay samples tended to decelerate the migration of the N-methylamines in the TLC plates. Additional tests were performed to elucidate the identities of the N-methylamines by scraping the spots from the TLC plates and rerunning the eluted material with the authentic standards. Finally, radioactivity in the TLC plates was imaged and calculated by the Bio-imaging analysis system (Fuji Photographic Co., Tokyo, Japan).

RESULTS

Effects of extracellular addition of sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and betaine on the intracellular compatible-solute pool of M. portucalensis.

Tests were performed to examine how possible betaine biosynthesis intermediates, sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and betaine, influence the intracellular osmolyte pool of M. portucalensis. Cells were grown in a defined medium containing 2.1 M NaCl, and methanol was the sole carbon source. Sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and betaine (1 mM each) were added to the medium. Ethanol extracts of mid-exponential-phase culture were collected and analyzed for the intracellular level of osmolytes. As shown in Table 1, betaine, Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine, β-glutamine, and α-glutamate are the major solutes in the methanol-grown M. portucalensis in defined medium with 2.1 M NaCl. With the external addition of betaine, the intracellular concentrations of Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine, β-glutamine, and α-glutamate were dramatically suppressed. With the addition of sarcosine, the intracellular level of betaine dropped while the levels of Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine, β-glutamine, and α-glutamate slightly increased. This finding suggests that a high level of sarcosine suppressed the de novo biosynthesis of betaine (Table 1). In contrast, the external addition of dimethylglycine maintained an intracellular osmolyte level similar to that in the betaine addition test, which was high in betaine, and nearly abolished the levels of Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine, β-glutamine, and α-glutamate. Table 1 also shows slightly higher levels of intracellular osmolytes with the addition of dimethylglycine than with the added-betaine test.

TABLE 1.

Effects of extracellular addition of sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and betaine on the intracellular compatible-solute pool of M. portucalensis FDF1a

| Extracellular addition | Intracellular compatible solutes (M)b

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Glu | NABL | β-Gln | Betaine | Total | |

| None | 0.20 | 0.43 | 0.25 | 0.76 | 1.64 |

| Sarcosine (1.0 mM) | 0.29 | 0.56 | 0.28 | 0.10 | 1.23 |

| Dimethylglycine (1.0 mM) | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.90 | 1.30 |

| Betaine (1.0 mM) | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.87 | 1.03 |

Cells were grown at 37°C in a defined medium containing 2.1 M NaCl and 100 mM methanol as carbon source.

α-Glu, l-α-glutamate; NABL, Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine; β-Gln, β-glutamine; Betaine, glycine betaine. The total shows the intracellular osmolarity, which includes l-α-glutamate, Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine, β-glutamine, and glycine betaine.

In vivo betaine formation.

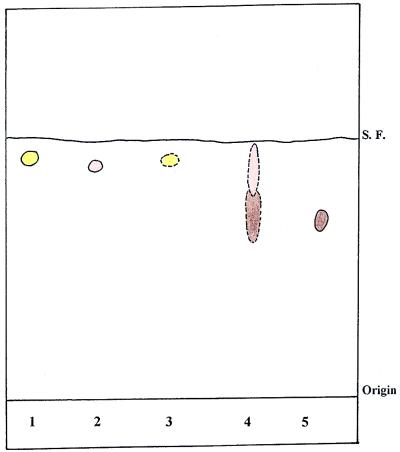

To examine betaine formation in vivo, cells were incubated with [14C]glycine and anaerobically harvested at mid-log phase. Concentrated ethanol extracts were applied to the TLC plate and chromatographed with the solvent system of methanol-acetone-HCl (9:1:1) to separate glycine, sarcosine, and betaine. After chromatography, two different stain systems and radioactivity analyses were applied. Two radioactive spots that slightly overlapped each other were detected in the ethanol extract of the culture of M. portucalensis with [14C]glycine added. One spot corresponded to the authentic betaine Rf value of 0.71 and displayed a brownish color with an iodine vapor stain, indicating that it was betaine. The other radioactive spot showed a pinkish color under heated ninhydrin stain and had an Rf value similar to that of authentic sarcosine (Fig. 1, lane 4). These results showed that the addition of [14C]glycine to the culture of M. portucalensis led to the intracellular accumulation of [14C]sarcosine and [14C]betaine.

FIG. 1.

TLC separation of ethanol extract from M. portucalensis FDF1 in a methanol-acetone-HCl (9:1:1) solvent system. The culture was grown in 12% NaCl defined medium with the addition of [14C]glycine. After TLC separation, the color was developed by heated ninhydrin solution and an iodine chamber. Radioactivity was detected by a β-scanner. Spots with dashed outlines indicate the areas with radioactivity. Lane 1, authentic glycine; lane 2, authentic sarcosine; lane 3, [14C]glycine; lane 4, ethanol extract of M. portucalensis; lane 5, authentic betaine. S. F., solvent front.

Effects of Li+, K+, and Na+ on biosynthesis of betaine.

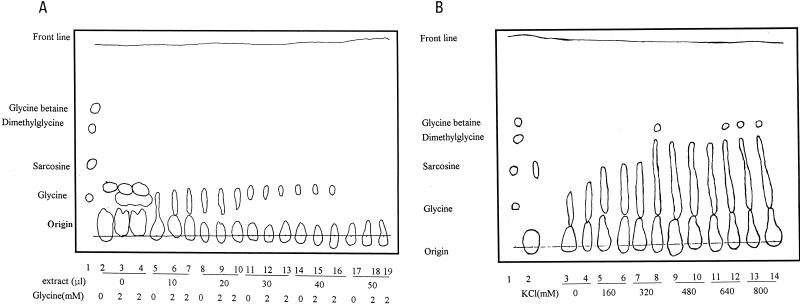

In vitro betaine formation assays were performed with the anaerobic crude extract of M. portucalensis FDF1, with SAM as the methyl donor and glycine as the substrate. Following the reaction, samples were concentrated and spotted onto the TLC plate for glycine, sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and betaine separation with a phenol-water (4:1) solvent system, and then the samples were colored with bromocresol green solution. As shown in Fig. 2A, no N-methylamines (sarcosine, dimethylglycine, or betaine) were detected in any of the tests containing glycine and anaerobic crude extracts. Moreover, the amount of glycine substrate (including both the residual in the crude extract and the addition in the assay) decreased with an increasing amount of crude extract. This phenomenon suggests that the anaerobic crude extract may consume the glycine substrate for other biochemical reactions. However, this extract does not synthesize betaine or any intermediates (sarcosine or dimethylglycine) under these assay conditions. Interestingly, the intracellular concentration of potassium ions in M. portucalensis was high, within the range of 0.6 to 1.1 M, when the extracellular NaCl concentration ranged from 1.7 to 2.7 M (22). Therefore, we added various levels of KCl (0 to 800 mM) to the same in vitro betaine formation assays shown in Fig. 2A, with 2 mM glycine used as the substrate. After bromocresol green staining, the large bluish-colored areas obviously indicated the presence of N- methylamines (glycine, sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and betaine) on the TLC plate for this assay with added KCl (Fig. 2B). In addition, the level of N-methylamine increased with an increase in the concentration of added potassium (Fig. 2B). In some tests, blue betaine spots were clearly identified. These assays clearly demonstrated that a high level of potassium is a prerequisite for de novo betaine biosynthesis.

FIG. 2.

N-Methylamine separation in betaine formation assays under a TLC phenol-water system. (A) The tests were performed by detecting the N-methylamine products after the anaerobic reaction (180 min; 37°C) of crude extract (9.73 μg of protein/10 μl) in 50 mM TES buffer with or without the addition of 2 mM glycine. Lane 1 is the mixture of glycine (19 μg), sarcosine (22 μg), dimethylglycine (26 μg), and betaine (29 μg). Lane 2 is the crude extract of M. portucalensis FDF1. (B) Tests were performed by detecting the N-methylamine products after the anaerobic reaction (180 min; 37°C) of crude extract (38.93 μg of protein) in 50 mM TES buffer with the addition of 2 mM glycine. KCl was added at the indicated concentrations.

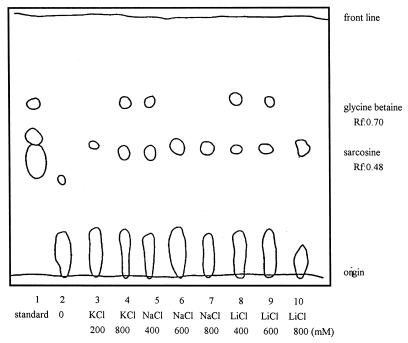

We also tested the effects of Li+, Na+, and K+ on betaine formation. In vitro betaine formation assays were performed with an anaerobic crude extract of M. portucalensis and with glycine as the substrate, SAM as the methyl donor, and the indicated level of KCl, LiCl, or NaCl added, as described in Materials and Methods. Additionally, samples were eluted from the Dowex minicolumns to reduce high-salt and protein effects during the separation by TLC. As shown in Fig. 3, all assays with KCl, LiCl, or NaCl (200 to 800 mM) synthesized only sarcosine or both sarcosine and betaine. However, the control assay without added cations showed that only glycine remained; no sarcosine or betaine was formed. After Dowex minicolumn treatment, the migration rate of N-methylamine was slightly higher than that of the authentic standard. Although the Rf value of authentic sarcosine was 0.42, the Rf values of assay samples were 0.48. To confirm the identities of these spots on the TLC plate, they were scraped off, dissolved in water, concentrated, respotted onto another TLC plate, and rerun in the same solvent system along with authentic glycine, sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and betaine.

FIG. 3.

N-methylamine separation in betaine formation assays under a TLC phenol-water system. The tests were performed by adding various concentrations of NaCl, KCl, and LiCl to the anaerobic crude extract of M. portucalensis FDF1 containing 50 mM TES buffer and 2 mM glycine. The reactions were incubated at 37°C for 4 h, and the reaction mixtures were passed through Dowex minicolumns to remove salt after the reaction was stopped. Samples were eluted with ammonia. Lane 1 is the mixture of standards containing glycine, sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and betaine. The Rf values of treated samples were slightly higher than that of the standard, with the Rf value for sarcosine at 0.48 and that for betaine at 0.67.

All three cations, Li+, Na+, and K+, can affect sarcosine and betaine formation. Nevertheless, the biosynthesis of sarcosine differs from that of betaine in its regulation. Assays with LiCl added in the range of 400 to 600 mM showed the formation of both sarcosine and betaine; however, a high concentration of LiCl (800 mM) led to the formation of sarcosine alone. This finding suggests that a higher level of LiCl may suppress the process of converting sarcosine to betaine (Fig. 3). Sodium chloride behaved similarly to LiCl in its effects on betaine formation, although the effective concentration range was slightly different (Fig. 3). Betaine was not accumulated in the assay with 600 mM NaCl (Fig. 3). In contrast to the effects of Na+ and K+, betaine was only detected in the assay with a high concentration of KCl (800 mM) but not with the smaller amount of KCl (200 mM). This experimental result again demonstrated that a high potassium level is a prerequisite for betaine formation.

Combinatory effect of biosynthesis intermediates and potassium ions on the de novo biosynthesis of betaine in vitro.

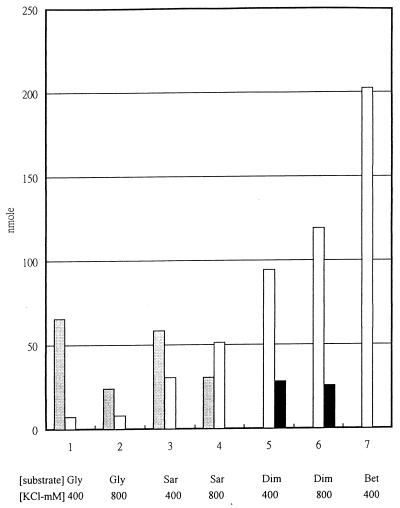

The combined effects of glycine, sarcosine, dimethylglycine, betaine, and potassium ions on betaine formation were tested. In vitro betaine formation assays were performed with an anaerobic crude extract of M. portucalensis FDF1 and with [methyl-14C]SAM as the methyl donor and 400 or 800 mM KCl added. Glycine, sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and betaine (2 mM each) were added as the substrate. The controls had deionized water in place of the biosynthetic intermediates. After incubation, samples were run through Dowex minicolumns and concentrated. Then glycine, sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and betaine were separated on a silica gel TLC plate under a phenol-H2O (4:1) solvent system. Radioactivity was detected by the Bio-imaging analysis system. The concentrations of sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and betaine in the assay sample were calculated by subtracting appropriate values from the controls. All assays with 400 mM KCl accumulated larger amounts of sarcosine than assays with 800 mM KCl, whereas assays with 800 mM KCl accumulated higher levels of betaine (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Amounts of sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and betaine from in vitro betaine formation assays with [14C]SAM as methyl donor with different substrates added and under various potassium ion concentrations. The assays were performed with 50 mM TES buffer, 4.6 mM SAM (including 1.0 μCi of [methyl-14 C]SAM), 2 mM (each) indicated substrate, and 400 or 800 mM KCl added to anaerobic crude extract of M. portucalensis FDF1 (20 μg of protein) for 4 h at 37°C. The controls had deionized water in place of the biosynthetic intermediates. Concentrated assay samples were spotted onto a silica gel plate for N-methylamine separation with a phenol-water (80:20) solvent system, and radioactivity was detected by the Bio-imaging analysis system. The amounts of sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and betaine in the tests were subtracted from the control test and calculated. Symbols:  , sarcosine; □, betaine; ■, dimethylglycine.

, sarcosine; □, betaine; ■, dimethylglycine.

Results from the [14C]SAM-labelled in vitro betaine formation assays corresponded to the in vivo and in vitro studies mentioned earlier. When glycine was used as the substrate, sarcosine was the major solute and only a low level of betaine was observed; however, no dimethylglycine was detected. The sarcosine level was threefold higher in the assay with 400 mM KCl than in the assay with 800 mM KCl when glycine was used as the substrate (Fig. 4, lanes 1 and 2). When sarcosine was added as a substrate, sarcosine and betaine were detected but not dimethylglycine. Also, betaine formation increased four- to sevenfold compared to that in the assays with glycine as the substrate. A higher KCl level in the assay led to a larger amount of betaine accumulated (Fig. 4, lanes 3 and 4). In the assays with dimethylglycine as the substrate, higher levels of betaine were accumulated and moderate amounts of dimethylglycine were detected. Again, a higher KCl level in this assay led to a larger amount of betaine accumulated (Fig. 4, lanes 5 and 6). The amount of betaine produced gradually increased as the substrate was changed from glycine to sarcosine, to dimethylglycine, and to betaine. This finding confirmed the stepwise methylation process of betaine, formation from glycine, sarcosine, and dimethylglycine to betaine, with SAM as the methyl donor, as suggested by the NMR studies of Roberts et al. (34). Additionally, when betaine itself was added as a substrate in the assay, only betaine (2.5 nmol/μg · h) was detected, with no other intermediates (sarcosine or dimethylglycine). Since [methyl-14C]SAM was used as the methyl donor and radioactivity was detected in the methyl-14 C group of betaine in this assay, betaine biosynthesis could still proceed. The radioactive betaine may arise from the betaine demethylation to dimethylglycine and the remethylation to betaine. Since dimethylglycine pools are low, any exogenous betaine formed would be quickly converted to the radioactive species.

DISCUSSION

Intracellular potassium glutamate as a secondary signal of osmotic stress in enteric bacteria has received extensive attention (5, 9, 29). In extremely halophilic archaea, e.g., Halobacterium sp., high intracellular potassium concentrations have been reported, and the function of K+ as an inorganic osmolyte in these hypersaline microorganisms has also been discussed (18, 28). In methanoarchaea, high intracellular potassium concentrations, in the range of 800 to 1,200 mM, have been reported in the family Methanobacteriaceae (17). High intracellular potassium levels have also been reported in the marine species Methanosarcina thermophila (40), the moderate halophilic methanogen M. portucalensis FDF1 (22), and the extremely halophilic methanogen Methanohalophilus strain Z7302 (23). The total intracellular potassium concentration in M. thermophila increased with an increase in the medium osmolarity (40). Similarly, the intracellular concentration of potassium in M. portucalensis FDF1 increased from 0.6 to 1.1 M when the extracellular NaCl concentration ranged from 1.7 to 2.7 M (22). Even-higher intracellular potassium levels (1.22 to 3.09 M) were detected in the extremely halophilic methanogen Methanohalophilus strain Z7302 when extracellular NaCl ranged from 2.05 to 4.10 M (23).

A detailed survey of osmolyte pools demonstrated that the mechanism of halotolerance in Methanosarcina spp. involves the regulation of K+, α-glutamate, Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine, and betaine accumulation in response to the osmotic effects of extracellular solute (40). An increasing intracellular level of potassium was accompanied by an increase in the intracellular concentration of betaine in the moderate halophile M. portucalensis FDF1 and in the extreme halophile Methanohalophilus strain Z7302 (22, 23). The results of this study demonstrated that a high level of potassium is necessary for the in vitro biosynthesis of betaine in M. portucalensis. The highest intracellular potassium level detected in M. portucalensis FDF1, grown in 12% NaCl, was 800 mM (22). With this high level of potassium added to in vitro assays, betaine was formed, but without added potassium, no N-methylamines were detected. These observations suggest that intracellular K+ not only controls the balance of the cytoplasmic osmolytes but may also function as an intracellular signal for osmoregulation.

Moreover, the cations sodium and lithium also influence the in vitro synthesis of betaine, but with patterns different from that of potassium. Notably, a higher level of sodium or lithium ions (800 mM) leads to the accumulation of sarcosine, with no betaine. Reductions in sodium or lithium levels (to 600 and 400 mM, respectively) led to increased betaine biosynthesis. In contrast, a higher level of potassium led to a larger amount of betaine. This finding suggests that a high level of LiCl or NaCl may suppress the conversion of sarcosine to betaine while a high level of KCl enhances betaine formation. Unfortunately, the intracellular concentration of Na+ and Li+ in the halophilic methanogens is not known. Therefore, the role these cations play in the halotolerance mechanism in the methanoarchaea is not clear.

De novo synthesis of betaine in M. portucalensis FDF1 was originally confirmed by growing the cells in a defined medium that contained methanol and 15NH4Cl instead of 14NH4Cl. The 1H-decoupled 15N NMR spectrum of the extract from these cells indicated incorporation of the label into betaine (22). The intracellular level of betaine increased with an increase in the external salt concentration, implying that it functions as an osmolyte (22). The turnover rate of betaine measured by 13CH3OH pulse-12CH3OH chase experiments was low (0.022 h−1), which is consistent with its role as an osmolyte (36). Although unable to synthesize betaine de novo, most eubacteria can accumulate it by taking up choline and converting it to betaine (3, 25). The steps involved in the uptake of choline and its enzymatic conversion into betaine in Escherichia coli and other organisms have also been extensively studied (1, 3, 9, 10, 15, 25). Previous studies have demonstrated that M. portucalensis possesses a high-affinity and highly specific betaine transport system (14); however, it does not internalize choline (data not shown). This feature suggests that betaine accumulation through a choline uptake and oxidation process is unlikely to occur in this halophilic methanogen.

NMR spectroscopic analyses of 13CH3OH-12CO2 label incorporation by M. portucalensis FDF1 suggested that the biosynthetic pathway of betaine is through the methylation of glycine generated from serine. The glycine is then methylated by an intermediate methyl donor to sequentially form sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and ultimately, betaine (34). These NMR results were confirmed in this study with in vivo and in vitro betaine formation assays with [14C]glycine and [14C]SAM, respectively. 14C-labelled sarcosine and betaine were the major solutes in ethanol extracts of [14C]glycine-grown M. portucalensis. Also, 14C-labelled sarcosine, dimethylglycine, and betaine were detected in an in vitro study where [methyl-14C]SAM was added to the crude extracts of M. portucalensis. In general, the de novo biosynthesis of betaine osmolyte is through the stepwise methylation of glycine by SAM.

Sarcosine and betaine can easily be detected by both in vivo and in vitro betaine formation assays. However, dimethylglycine was only detected in the in vitro betaine formation assay, when dimethylglycine was used as the substrate and [methyl-14C]SAM was added. Moreover, externally adding dimethylglycine to the M. portucalensis culture has an effect similar to that of betaine addition, in which the intracellular pool of betaine increased and the other solutes (Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine and β-glutamine) were suppressed. By using NMR spectroscopic analysis of the effect of exogenous dimethylglycine on the distribution of intracellular solutes, Robinson and Roberts (37) recently reported the similar result that exogenous dimethylglycine greatly increased the intracellular betaine level and that the betaine generated from it suppresses the synthesis of the other osmolytes. These results suggest that the methylation of dimethylglycine to form betaine is a relatively rapid process and causes dimethylglycine to be maintained at low levels. Interestingly, the occurrence of dimethylglycine as a major osmolyte that varies with external osmolarities has been reported in another halophilic methanogen—Methanohalophilus mahii (30). Halophilic methanogens may have more diverse pathways for forming and utilizing the N-methylamines as an osmolyte.

NMR spectroscopic analysis of the effect of exogenous sarcosine on the distribution of intracellular solutes showed that exogenous sarcosine did not bias the cells to accumulate any more betaine (37). The present study showed that the intracellular compatible-solute pool of betaine was depressed (from 0.8 to 0.1 M) with the addition of 1.0 mM sarcosine in methanol-grown M. portucalensis (Table 1). In addition, a higher level of sarcosine accumulation accompanied by a lower level of betaine biosynthesis was observed in [14C]SAM-labelled in vitro betaine formation assays with the crude extract of M. portucalensis (Fig. 4).

The apparently rapid conversion of dimethylglycine to betaine and suppression of betaine biosynthesis by high levels of sarcosine suggested that at least two different processes are involved in the formation of betaine from glycine. One process is associated with the formation of sarcosine from glycine (glycine N-methyltransferase). The other process is associated with the formation of glycine betaine from sarcosine and dimethylglycine. It may involve two independent enzymes (sarcosine N-methyltransferase and dimethylglycine methyltransferase) or a single amine N-methyltransferase with a broad substrate specificity. The intracellular levels of both sarcosine and potassium ions are associated with the regulation of betaine synthesis. A high intracellular sarcosine level suppressed methyltransferase activity for dimethylglycine and betaine formation, and a higher level of potassium led to a larger amount of betaine while a lower level of potassium led to a larger amount of sarcosine. Therefore, the potassium level should significantly influence both processes of betaine formation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank R. P. Gunsalus for the use of laboratory facilities during the initial stages of this work.

This work has been supported by grants NSC 82-0203-B-005-146 and NSC 86-2311-B-005-015 from the National Council of Science, Taiwan, Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anthoni U, Christophersen C, Horegard L, Nielsen P H. Quaternary ammonium compounds in the biosphere—an example of a versatile adaptative strategy. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1991;99B:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balch W E, Fox G E, Magrum L J, Woese C R, Wolfe R S. Methanogens: reevaluation of a unique biological group. Microbiol Rev. 1979;43:260–296. doi: 10.1128/mr.43.2.260-296.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boch J, Kempf B, Bremer E. Osmoregulation in Bacillus subtilis: synthesis of the osmoprotectant glycine betaine from exogenously provided choline. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5364–5371. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5364-5371.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boone D R, Mathrani I M, Liu Y, Menaia J A G F, Mah R A, Boone J E. Isolation and characterization of Methanohalophilus portucalensis sp. nov. and DNA reassociation study of the genus Methanohalophilus. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:430–437. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Booth I R, Higgins C F. Enteric bacteria and osmotic stress: intracellular potassium glutamate as a secondary signal of osmotic stress? FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1990;75:239–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burg M B, Kwon E D, Kiltz D. Regulation of gene expression by hypertonicity. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:437–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciulla R, Clougherty C, Belay N, Krishan S, Zhou C, Byrd D, Roberts M F. Halotolerance of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH and Marburg. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3177–3187. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3177-3187.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciulla R A, Burggraf S, Stetter K O, Roberts M F. Occurrence and role of di-myo-inositol-1,1 phosphate in Methanococcus igneus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3660–3664. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.10.3660-3664.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Csonka L N. Physiological and genetic responses of bacteria to osmotic stress. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:121–147. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.121-147.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Csonka L N, Hanson A D. Prokaryotic osmoregulation: genetics and physiology. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:569–606. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.003033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galinski E A, Truper H G. Betaine, a compatible solute in the extremely halophilic phototrophic bacterium Ectothiorhodospira halochloris. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1982;13:357–360. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galinski E A. Compatible solutes of halophilic eubacteria: molecular principles, water-solute interaction, stress protection. Experientia. 1993;49:487–496. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galinski E A, Truper H G. Microbial behavior in salt stress ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;15:95–108. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong T-Y, Lai M-C. Abstracts of the 97th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1997. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. Glycine betaine transport in the halophilic methanogen, abstr. K-144; p. 366. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikuta S, Matuura K, Imamura S, Misaki H, Horiuti Y. Oxidation pathway of choline to betaine in the soluble fraction prepared from Arthrobacter globiformis. J Biochem. 1977;82:157–163. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imhoff J F. Osmoregulation and compatible solutes in eubacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1986;39:57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarrell K F, Sprott G D, Matheson A T. Intracellular potassium concentration and relative acidity of the ribosomal proteins of methanogenic bacteria. Can J Microbiol. 1984;30:663–668. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Javor B. Hypersaline environments: microbiology and biochemistry. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1989. pp. 101–124. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones W J, Nagle D P, Jr, Whitman W B. Methanogens and the diversity of archaebacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:135–177. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.1.135-177.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kappes R M, Kempf B, Bremer E. Three transport systems for the osmoprotectant glycine betaine operate in Bacillus subtilis: characterization of OpuD. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5071–5079. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5071-5079.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kinne R K H. The role of organic osmolytes in osmoregulation: from bacteria to mammals. J Exp Zool. 1993;265:346–355. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402650403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai M-C, Sowers K R, Robertson D E, Roberts M F, Gunsalus R P. Distribution of compatible solutes in the halophilic methanogenic archaebacteria. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5352–5358. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5352-5358.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai M-C, Gunsalus R P. Glycine betaine and potassium ion are the major compatible solutes in the extremely halophilic methanogen Methanohalophilus strain Z7302. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7474–7477. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7474-7477.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai M-C, Ciulla R, Roberts M F, Sowers K R, Gunsalus R P. Extraction and detection of compatible intracellular solutes. In: Sowers K R, Schreier H T, editors. Archaea: a laboratory manual. 2. Methanogens. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. pp. 349–368. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landfald B, Strom A R. Choline-glycine betaine pathway confers a high level of osmotic tolerance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:849–855. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.3.849-855.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lippert K, Galinski E A. Enzyme stabilization by ectoine-type compatible solutes: protection against heating, freezing and drying. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1992;37:61–65. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lucht J M, Bremer E. Adaptation of Escherichia coli to high osmolarity environment: osmoregulation of the high affinity glycine betaine transport system ProU. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;14:3–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matheson A T, Sprott G D, McDonald I J, Tessier H. Some properties of unidentified halophile: growth characteristics, internal salt concentration and morphology. Can J Microbiol. 1976;22:780–786. doi: 10.1139/m76-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLaggen D, Naprstek J, Epsteo W. Interdependence of K+ and glutamate accumulation during osmotic adaptation of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1911–1917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menaia J A G F, Duarte J C, Boone D R. Osmotic adaptation of moderately halophilic methanogenic archaebacteria, and detection of cytosolic N, N-dimethylglycine. Experientia. 1993;49:1047–1054. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ollivier B, Canmette P, Gareia J L, Horiuti Y. Anaerobic bacteria from hypersaline environments. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:27–38. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.1.27-38.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pollard A, Wyn Jones R G. Enzyme activities in concentrated solutes of glycine betaine and other solutes. Planta. 1979;144:291–298. doi: 10.1007/BF00388772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Proctor L M, Lai R, Gunsalus R P. The methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcina thermophila TM-1 possesses a high-affinity glycine betaine transporter involved in osmotic adaptation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2252–2257. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2252-2257.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts M F, Lai M-C, Gunsalus R P. Biosynthetic pathway of the osmolytes Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine, β-glutamine, and betaine in Methanohalophilus strain FDF1 suggested by nuclear magnetic resonance analyses. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6688–6693. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.20.6688-6693.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robertson D E, Roberts M F. Organic osmolytes on methanogenic archaebacteria. Biofactors. 1991;3:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robertson D E, Lai M-C, Gunsalus R P, Roberts M F. Composition, variation, and dynamics of major osmotic solutes in Methanohalophilus strain FDF1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2438–2443. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.8.2438-2443.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robinson P M, Roberts M F. Effects of osmolyte precursors on the distribution of compatible solutes in Methanohalophilus portucalensis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4032–4038. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.10.4032-4038.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sibley M H, Yopp J H. Regulation of S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase in the halophilic cyanobacterium Aphanothece halophytica: a possible role in glycine betaine biosynthesis. Arch Microbiol. 1987;149:43–46. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sowers K R, Robertson D E, Noll D, Gunsalus R P, Roberts M F. Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine: an osmolyte synthesized by methanogenic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9083–9087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sowers K R, Gunsalus R P. Halotolerance in Methanosarcina spp.: role of Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine, α-glutamate, glycine betaine, and K+ as compatible solutes for osmotic adaptation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4382–4388. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.12.4382-4388.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yancey P H, Clark M E, Hand S C, Bowlus R D, Somero G N. Living under water stress: evolution of osmolyte systems. Science. 1982;217:1214–1222. doi: 10.1126/science.7112124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhilina T N. Methanogenic bacteria from hypersaline environments. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1986;7:216–222. [Google Scholar]