Abstract

Problem

Maternity care underwent substantial reconfiguration in the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Background

COVID-19 posed an unprecedented public health crisis, risking population health and causing a significant health system shock.

Aim

To explore the psycho-social experiences of women who received maternity care and gave birth in South London during the first ‘lockdown’.

Methods

We recruited women (N = 23) to semi-structured interviews, conducted virtually. Data were recorded, transcribed, and analysed by hand. A Classical Grounded Theory Analysis was followed including line-by-line coding, focused coding, development of super-categories followed by themes, and finally the generation of a theory.

Findings

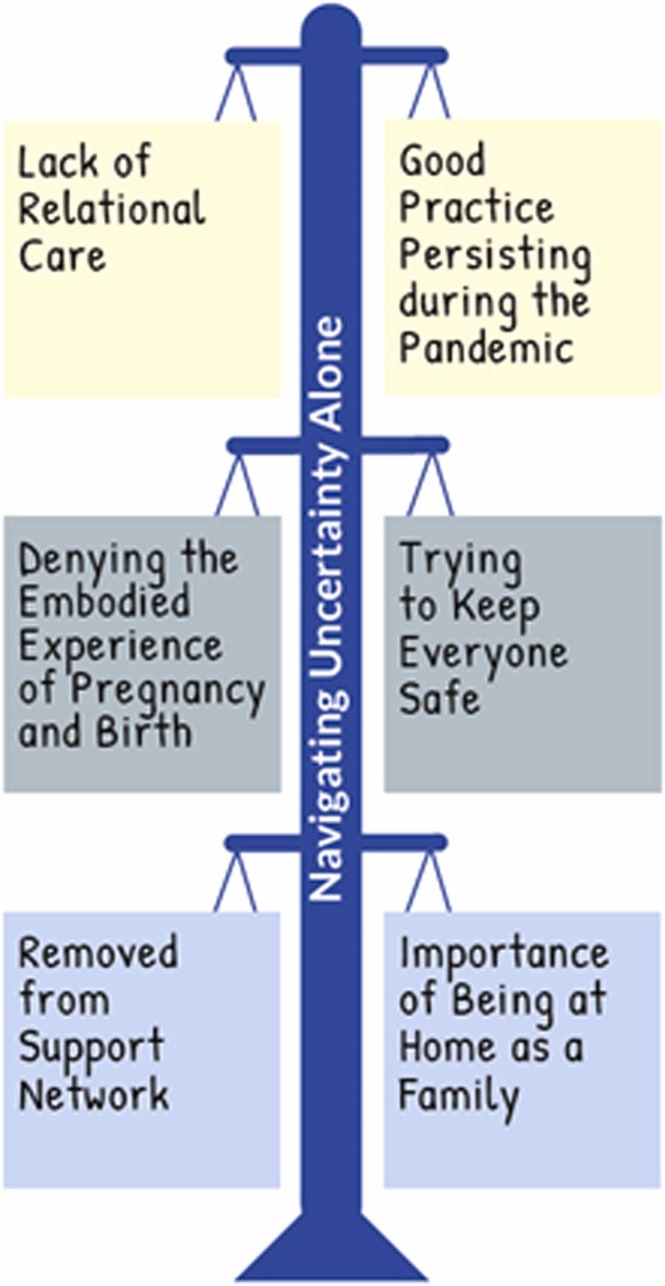

Iterative and inductive analysis generated six emergent themes, sorted into three dyadic pairs: 1 & 2: Lack of relational care vs. Good practice persisting during the pandemic; 3 & 4: Denying the embodied experience of pregnancy and birth vs. Trying to keep everyone safe; and 5 & 6: Removed from support network vs. Importance of being at home as a family. Together, these themes interact to form the theory: ‘Navigating uncertainty alone’.

Discussion

Women’s pregnancy and childbirth journeys during the pandemic were reported as having positive and negative experiences which would counteract one-another. Lack of relational care, denial of embodied experiences, and removal from support networks were counterbalanced by good practice which persisted, understanding staff were trying to keep everyone safe, and renewed importance in the family unit.

Conclusion

Pregnancy can be an uncertain time for women. This was compounded by having to navigate their maternity journey alone during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Abbreviations: COVID-19, The SARS-CoV-2 novel coronavirus; NHS, National Health Service; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; PPIE, Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement; RCOG, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; RCM, Royal College of Midwives

Keywords: COVID-19, Maternity care, Pregnancy and childbirth, Women’s psycho-social experiences, Qualitative methods, Grounded theory

Statement of significance

Problem or Issue

During the COVID-19 pandemic, pregnant women experienced substantial maternity care reconfiguration.

What is already known

The change to maternity care services impacted on women’s access to healthcare and social support, quality of care, and has been found to affect their psychological health, emotional wellbeing, and social support networks.

What this paper adds

By exploring the experiences of women who gave birth during the COVID-19 pandemic, we provide additional evidence about the importance of relational care, social support, and the woman as the expert of her embodied experience.

1. INTRODUCTION

The 2020 International Year of the Nurse and Midwife was met with an unprecedented health system shock, which changed the face of healthcare across the globe. The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 or ‘COVID-19′ outbreak, disrupted healthcare services globally, as they prepared for a surge in hospitalisations due to increased infection rates, with fewer healthcare professionals available to provide care [1], [2], [3]. National government-mandated stay-at-home orders or ‘lockdowns’, and a wide range of social restrictions were implemented in many countries to curb the spread of infection. In the United Kingdom (UK), the first such national lockdown took effect on 23rd March 2020 with national restrictions easing from 13th May 2020 onwards.

There has been growing concern that women in the perinatal period have been disproportionally affected by both the direct and indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic [4]. Particular vulnerability to severe illness has been demonstrated among pregnant women: from Black, Asian, or Minority Ethnic backgrounds; with an increased body mass index (BMI) or existing co-morbidities; of advanced maternal age (≥35 years); living in areas of socio-economic deprivation [5]. As such, and especially in the UK context, the pandemic has re-exposed existing inequalities in healthcare outcomes between individuals from less (vs. more) affluent socio-economic and non-White (vs. White) ethnic groups [6].

At the outset of the pandemic in the UK, pregnant women were identified as having a particular clinical vulnerability to the virus [7] and, to reduce the risk of becoming infected, were advised to ‘shield’ – remain at home under all circumstances unless seeking urgent medical care, or, in the case of pregnant women, travelling to hospital to give birth [8]. This advice remained in place until July 2020, when initial evidence suggested pregnancy in itself was not a risk factor for severe illness [9], but that women who contract the virus in their third trimester may experience more severe symptoms [10]. Simultaneously, maternity services in the UK reconfigured to minimize the risk of COVID-19 transmission amongst healthcare staff, women, and their infants [11], [12]. These changes included restricted access for visitors and birth partners, a modified schedule of antenatal and postnatal appointments [11], [12], [13], a reduction in face-to-face midwifery and obstetric contact, an increase in virtual or telephone contact [12], modifications to screening and monitoring of multi-morbidity in pregnancy [11], [14], and changes to induction of labour pathways [15]. In the UK National Health Service (NHS), healthcare provision is organised into Trusts which act as organisational units serving particular geographic areas or offering specialist services, such as mental health care or ambulance provision. During the pandemic, individual NHS Trusts issued guidance related to home-birth provisions, midwifery-led units, and water birth, reducing women’s options for birth and leading some women to explore giving birth without the assistance of healthcare professionals: ‘free-birthing’ [16]. Whilst national guidance was issued, conflicts arising between the NHS and the guidance issued jointly between the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) and the Royal College of Midwives (RCM), led to local-level decision-making on how to reconfigure services, either by Hospital Trust or individual hospitals.

Throughout the pandemic, evidence from many countries has consistently suggested pregnant and postpartum women have experienced: increased levels of anxiety [17], [18], pregnancy-related stress [19], anxiety related to fear of contracting the virus [20], and the lack of social support [21], [22]. Reduced access to maternity services has been coupled with a reduction in health-seeking behaviours, with poorer outcomes for pregnant women and their babies being noted, such as increased mortality, stillbirth, and ruptured ectopic pregnancies [23], [24], [25]. To tailor adequate support and inform maternity service reconfiguration during future public health crises, it is essential to understand the psycho-social experiences of women who were pregnant and gave birth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Here we take psycho-social experiences to mean the inter-relation of social factors and individual thoughts, emotions, and behaviours. The aim of this study was, therefore, to explore the psycho-social experiences of women who received maternity care in South London during the first ‘lockdown’ until initial easing of restrictions to daily life and social distancing regulations (23 March – 13 May 2020).

2. PARTICIPANTS, ETHICS, AND METHODS

2.1. The present study

The present study was part of a larger project called: ‘The King’s Together Fund (KTF) Changing Maternity Care Study’, funded by the King’s College London King’s Together Rapid COVID-19 Call for rapid response research into the COVID-19 pandemic. The present study engaged women who had received their maternity care and given birth in South London, in semi-structured interviews about their experiences of care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Both study methods and analysis followed a Classical Grounded Theory Analysis methodology [26].

2.2. The study team and reflexivity

The authors are a multi-disciplinary team of researchers and clinical academics, with backgrounds in Midwifery (EM, KDB, JS), Medicine (LAM), Psychology (SAS, AE), and the Social and Implementation Sciences (JS, SAS, AE), who together have a particular research focus on maternity and perinatal mental health (including maternal inequalities, multi-morbidity, care delivery, implementation, and safety). Data were collected, and analysis and write-up overseen by a psychologist, experienced in qualitative research with particular expertise in sensitive interviewing (SAS). Analysis was led by two midwives – one in active clinical practice (KDB) and the other, an experienced academic (EM). Regular meetings were held between the analysts (EM, KDB, SAS) to discuss emergent themes and the developing theory, and each stage of the analysis was discussed with the wider team to sense-check from a psycho-social (AE), clinical medicine (LAM), and policy and practice (JS) perspective. Field notes and theoretical memos [27] were kept by all researchers to aid bracketing [28] of pre-conceived notions of the population (women), phenomenon (pregnancy and childbirth), and context (the COVID-19 pandemic). In this study, bracketing [28] was employed to allow researchers to abide by the Grounded Theory principle of ‘no a priori assumptions’ [26], [29], [30], as it is known for researchers who work closely to their field, phenomena, or population of study, it is often difficult to maintain a tabula rasa [31] .

2.3. Theoretical perspective

This study adopted a theoretical perspective in-line with gendered lifecourse research [32], [33], whereby in Western settings (such as the UK), the normative lifecourse of women includes pregnancy and childbirth. This transition into parenthood through pregnancy offers a site of empirical inquiry. A lifecourse perspective does not conflict with Grounded Theory Analysis – with Glaser and Strauss, themselves, noting the utility of researchers’ awareness of life being demarcated by transitions, each of which have a distinct trajectory and that social roles aid the development of one’s own life path [26]. To this end, our philosophical underpinning was seated in critical realist ontological and objectivist epistemological domains [34], and our positionality comprised a critical approach to reflexivity and an objective outsider position within the data (as none of the study team were experiencing pregnancy or childbirth at the time of the study i.e., during the COVID-19 pandemic; though some were providing clinical care). Together, these made for a post-positivist research paradigm [34], whereby participants’ narratives were accepted as ‘truths’ or ‘lived realities’ [35].

2.4. Ethics

Ethical approvals were granted by the King’s College London Biomedical & Health Sciences, Dentistry, Medicine and Natural & Mathematical Sciences Research Ethics Sub-Committee, in June 2020 (reference:- HR-19/20–19486).

2.5. Recruitment, setting, and participants

Our research group has a mandate for international (global), national (UK), and local (South London) research into maternity care, which during the pandemic has had a significant COVID-19 focus, led by the senior author of this article (SAS). This study was designed to understand local maternity care experiences, and so the focus was set to South London. Following ethical approval and initial Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement (PPIE) meetings, women were recruited to the study using social media adverts which briefly described the study. Some participants then snowballed the study details to other, eligible potential participants. Our method of recruitment followed a critical case purposeful sampling strategy [36]. This meant recruiting from a geographically bounded area (South London, UK) serving as a ‘critical case’ for empirical inquiry, with the aim of producing findings which could be extrapolated more widely, by matching on socio-demographic characteristics of the area (e.g., other cities with high levels of ethnic diversity, social complexity, and/or multiple deprivation) in future research.

Despite targeted involvement strategies to recruit a more ethnically and socio-economically diverse sample, the majority of participants who took part in this study (N = 23) self-identified as White (n = 20; 87%); and reported being married (n = 17; 74%) and employed (n = 22; 96%). Participants ranged in age from 27 to 44 years (M Age = 35 years) and most were primiparous (n = 13; 57%). All newborns were singletons (n = 23; 100%). Approximately a quarter of women were induced (n = 6; 26%), and approximately one-third of women had a Caesarean section (n = 8; 35%; elective: n = 4; 17%; emergency: n = 4; 17%), as compared with spontaneous (n = 13; 57%) or instrumental vaginal births (n = 2; 9%). Almost a third of women reported care which did not meet the threshold for appropriate one-to-one intrapartum care as recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [37] guidance (n = 7; 30%).

Participants reported giving birth in five of South London’s ten maternity hospitals with one participant having initiated antenatal care at one hospital and subsequently transferring care to another. Full demographic and pregnancy information is included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics and pregnancy characteristics.

| Participant Pseudonyms | Age | Ethnicity† | Marital or Partnership Status | Employment Status | Parity | Infant Sex | Antenatal Admission | Labour Companion Present at Birth | Place of Birth | Mode of Birth | Postnatal Admission | Comments on Pregnancy, Labour, or Birth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scarlett | 36 | White British | Married | Employed Part-time | 2 | Male | < 1 day | Yes | Labour Ward | SVD | unclear | Planned, low risk pregnancy, spontaneous labour, normal vaginal birth |

| Vanessa | 34 | White British | Married | Employed | 1 | Male | < 1 day | Yes | Labour Ward | SVD (after IOL) | < 1 day | IVF pregnancy, uneventful pregnancy, induction of labour after Prolonged Rupture of Membranes (PROM), normal vaginal birth |

| Stella | 42 | White Other | Married | Self-Employed | 1 | Female | < 1 day | Yes | Labour ward | SVD | 1 day | Planned pregnancy, SPD, high risk pregnancy due maternal age, spontaneous labour, normal vaginal birth, 3rd degree tear Transferred care during latter half of second trimester. |

| Tabitha | 31 | White British | Married | Employed | 1 | Female | < 1 day | Yes | Labour Ward | SVD | 5days (partner allowed to visit) | Planned and low-risk pregnancy, PPROM at 36weeks, normal vaginal birth at 36wks gestation, episiotomy, |

| Raquel | 32 | White British | Married | Employed | 1 | Male | 36hrs on antenatal ward without partner, 12hrs approx. labour ward with partner | Yes | Labour Ward | Instrumental birth (after IOL) | 2.5days | Unplanned pregnancy, polycystic ovaries; IOL for recurrent reduced foetal movements, Instrumental birth (ventouse) with episiotomy and 3rd degree tear; Baby had undescended testicle |

| Rosie | 33 | White British | Married | Self-Employed | 1 | Female | 3days | Yes | Labour Ward | Instrumental birth (after IOL) | 4nights/5days | Planned pregnancy, Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension (self-monitoring), IOL due to hypertension, Instrumental birth (ventouse) with PPH, treatment for chorioamnionitis; baby had jaundice and cephalhaematoma |

| Katarzyna | 37 | White European | Married | Employed | 1 | Male | < 1 day | Yes | Operating Theatre | Elective Caesarean Section | 4nights | Planned and uneventful pregnancy, elective CS at maternal request (declining IOL for post-maturity), prolonged PN stay due to feeding issues |

| Zara | 27 | White British | Married | Employed | 1 | Female | < 1 day | Yes | Midwife-Led birthing unit | SVD | 1night | Planned and uneventful pregnancy, failed ECV, spontaneous labour and breech Birth; PPH, postnatal admission to High Dependency Unit. PN readmission after 1week, with Psychiatric Review |

| Beatriz | 30 | Portuguese Mixed | Co-habiting | Employed | 2 | Female | 36hrs on antenatal ward (without partner) | Yes | Operating Theatre | Emergency Caesarean Section | 1night | Planned and uneventful pregnancy, planning VBAC, IOL for post-maturity (foley balloon), Emergency CS due to foetal distress, Meconium-stained liquor |

| Mandari | 44 | Asian – Sri Lankan | Married | Employed | 3 | Female | < 1 day | No | Induction bay, antenatal ward | SVD | 5nights | Unplanned pregnancy, Type II Diabetic (insulin-dependent during pregnancy), history of precipitate labour, no intrapartum care, baby requiring admission to special care baby unit (SCBU) |

| Alexa | 32 | White | Engaged | Employed | 1 | Male | 1night | Yes | Operating Theatre | Emergency Caesarean Section | 2nights | Planned and uneventful pregnancy, prolonged labour, emergency CS, Mum and Baby had low Sodium; Baby admitted to HDU, then SCBU (baby admitted for 7days) |

| Carolyn | 44 | White British | Single | Employed | 1 | Male | < 1 day | Yes | Operating Theatre | Emergency Caesarean Section (after IOL) | 2nights | IVF Pregnancy with Donor Sperm, high risk pregnancy (maternal age, large for gestational age), IOL for PROM, emergency CS for foetal distress |

| Elena | 38 | British Mixed | Co-habiting | Employed | 2 | Male | None | Yes | Labour Ward | SVD | < 1 day | IVF baby, high risk pregnancy due to low PAPP-A; no intrapartum care, baby born upon arrival in hospital |

| Hattie | 29 | White British | Married | Employed Part-time | 2 | Female | < 1 day | Yes | Operating Theatre | Emergency Caesarean Section | 2nights | PTSD from previous Pregnancy; Hyperemesis Gravidarum, high risk pregnancy due to gestational diabetes and previous history of Pre-Eclampsia, developed pre-eclampsia at 36wks |

| Samantha | 36 | White American | Married | Employed | 2 | Male | 1 day | Yes | Operating Theatre | Elective Caesarean Section | 1night | Previous traumatic birth experience, aiming for VBAC but changed to Elective CS due to large for gestational age baby |

| Jacqueline | 30 | White British | Married | Employed | 2 | Female | 80 min | Yes | Midwife-led birthing Unit | SVD | < 1 day | Planned uneventful pregnancy, anxiety, spontaneous labour at home, delayed transfer to hospital and baby born shortly after arrival |

| Ava | 42 | White British | Married | Employed | 2 | Male | < 1 day | Yes | Operating Theatre | Elective Caesarean Section | 1 day | Uneventful pregnancy, aiming for VBAC but decided to have elective CS |

| Imogen | 33 | White British | Married | Employed | 1 | Female | < 1 day | Yes | Operating Theatre | Elective Caesarean Section | 1 day | Uneventful pregnancy, elective CS due to breech |

| Faith | 39 | White British-Italian | Single | Unemployed | 4 | Female | < 1 day | No | Labour Ward | SVD | 1week | High risk pregnancy due to VTE risk and gestational diabetes, admission after Pre-term rupture of labour, no intrapartum care, baby requiring admission to High Dependency Unit |

| Felicity | 35 | British | Married | Employed Part-time | 2 | Female | < 1 day | No | Labour Ward | SVD (IOL) | 2nights | Low risk pregnancy, IOL after Prolonged rupture of membranes, no intrapartum care, transferred to labour ward in second stage of labour |

| Rosalyn | 31 | White British | Married | Employed | 1 | Female | < 1 day | Yes | Labour Ward | SVD (IOL) | 1night | Low risk pregnancy, IOL after PROM |

| Gillian | 31 | White British | Married | Employed | 1 | Male | < 1 day | Yes | Labour Ward | SVD | 1night | Low risk pregnancy, advised to remain home, arrived in hospital in second stage, no intrapartum care |

| Hollie | 35 | White Australian-British | Co-habiting | Employed | 1 | Male | None | Yes | Home | SVD | 2nights | Uneventful pregnancy, unplanned homebirth (BBA), no intrapartum care |

†Ethnicity was defined by participants in response to the question: “Could you tell me the ethnicity with which you identify?”

2.6. Data collection

Interested potential participants responded to the research team’s e-mail address, as detailed on the study posters. If they were eligible and agreed to take part, the interviewing researcher (SAS) e-mailed each prospective participant, the participant information sheet and consent form. A date and time suitable for the participant was then arranged, and interviews took place remotely using telephone or video-conferencing [38]. Interviews were semi-structured in nature [39] to ensure common questions were asked of each participant, but to allow enough flexibility for the researcher to pursue interesting lines of inquiry pertinent to and raised by individual participants. Interviews lasted between 30 and 90 min (M Time = 52 min), were recorded, and the audio files were transcribed and anonymised by a professional transcription company. Accuracy of the transcription was checked against the original audio for each participant by a researcher who had not undertaken the interviews (KDB), thus allowing data familiarisation. Participants were assigned a culturally sensitive pseudonym to allow for anonymity, whilst preserving their ethnic identity, as is common practice in qualitative research [40], [41].

2.7. Data analysis

Data were managed electronically, but ‘hand-coded’ using annotation functions on Microsoft Word. A Classical Grounded Theory Analysis [26] was employed to analyse the data, which is both inductive and iterative [29]. Broadly, Grounded Theory Analysis contains seven key principles [26], [30]:

-

1.

No a priori assumptions – the researchers have no preconceived notions of the population, the phenomenon, or the context of the study; and employ ‘bracketing’ to ensure assumptions are acknowledged and set-aside.

-

2.

Data-driven analysis – as opposed to analysis driven by a pre-existing theory or hypothesis

-

3.

In vivocoding – whereby data from participants was used to code transcripts

-

4.

Constant comparison – transcripts are compared to previously coded transcripts to assess the coding and the development of themes.

-

5.

Reflexive practice – whereby researchers keep field notes and theoretical memos to monitor their perspectives of the data

-

6.

Theoretical sampling – where participants with a particular characteristic may exhibit experiences contrary to the majority are specifically investigated to assess whether these anomalies are caused by a particular sub-group of the dataset, or whether they were evidence of a quirk demonstrated by an individual. This assessment is carried out by theoretically sampling in an attempt to recruit more respondents with similar characteristics to those exhibiting the deviating data.

-

7.

Testable theory – developed as the final analytical result.

This approach to Grounded Theory has nine study phases: Study Design and Development; Preparing Data; Cleaning Data; Coding; Theme Development; Theory Generation; Defence of Theory; Writing-up; and Testing the Theory; each of which have several data handling stages, totalling twenty [29].

In this study, data had saturated with a relatively low number of participants as is possible in studies with such specific parameters around population, phenomenon, and context [42]. However, when data saturation was apparent, only one participant (the fourteenth) who did not have a partner (i.e. single parent) had been recruited. Theoretical sampling [26], [43] is conducted with the aim of finding out whether data from participants within the sample who have a particular demographic feature (in this case, single parenthood) is different because of the demographic characteristic or because of a quirk presented by the individual. We therefore continued recruitment, and theoretically sampled for further participants who were unmarried or did not have a partner/were not co-habiting, which was achieved by participant fifteen. In total, twenty-three participants took part, with the residual nine (i.e., participants 15–23) being included in the study as a result of the extended recruitment period using theoretical sampling. In this study, theoretical sampling led to us concluding data from unmarried mothers or those who were not co-habiting, were no different to the data collected from married or co-habiting mothers. Participants 16–23 were therefore used as confirmatory participants for the codes, themes, and theory.

The process of analysing the data followed established practices of grounded theory [26], [29]. Data were coded twice, with lower order (‘open’) coding using verbatim data as initial codes for each line or sentence of the data – conducted by one researcher (KDB); and higher order (‘focused’) coding using slightly broader and more conceptual codes to represent wider trends in the data – conducted by another researcher (EM). Focused codes were merged, fragmented, or re-arranged to develop lower order themes (‘super-categories’), and these super-categories were again subjected to further analysis including collapsing together, splitting, and ordering, to develop higher order ‘themes’. The relationship between the themes, is the crux of the generated theory, which can include causal, processional, negative, and cyclical relationships [29], [30]. In the present study, it was noted that the themes occurred in distinct dyadic pairs, which were in constant oppositional tension. The theory was therefore derived as three sets of counter-balanced themes, which combined described the experience of women navigating uncertainty their pregnancy and birth experiences during the pandemic. Thematic development was undertaken by three researchers (EM, KDB, SAS) with consultative agreement from the wider team (LAM, JS, AE). Theory generation was led by two researchers (SAS, EM), with sense-checking provided by a third (KDB), and wider approval sought from the rest of the inter-disciplinary team (LAM, JS, AE). These iterative and consultative practices were used to improve our trust in the final analytic result and the credibility of the theory generated from the data.

3. FINDINGS

Analysis resulted in three sets of counterbalancing themes. These thematic dyads, supported with the most eloquent and illustrative quotations taken from across the dataset, are as follows:

-

•

Themes 1 & 2: Lack of relational care vs. Good practice persisting during the pandemic

-

•

Themes 3 & 4: Trying to keep everyone safe vs. Denying the embodied experience of pregnancy and birth

-

•

Themes 5 & 6: Removed from support network vs. Importance of being at home as a family

The final theory is also represented graphically ( Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Thematic Diagram of Final Themes in Theory.

3.1. Lack of relational care vs. Good practice persisting during the pandemic

Women whose antenatal care began pre-pandemic had been given expectations about what to expect from the maternity service during pregnancy, but were faced with a very different reality:

It was in the middle of March that the effect of COVID really took hold and that’s when there was a change in my appointments […] It wasn’t like I had a load of things fall out of the diary, it’s more that things didn’t go in the diary after that, so much. So, they became less frequent from the second half of the pregnancy onwards. I still had physical appointments at the diabetes clinic and at the hypertension clinic. I had a couple of midwife appointments that were on the phone, but that was literally two phone calls during the second half of the pregnancy and that was it. (Mandari).

For some this meant not only missing out on face-to-face care, but also continuity of care which had been recommended as leading to better outcomes for women. Those who had kept their appointments on the same day had them rearranged as COVID-19 hit and found that the midwives schedules had also been altered. This entailed meeting new staff:

The thing that was hardest was not only was it not face to face, but every time we spoke to someone it was someone different so you got slightly different advice, or they would say something slightly different. (Rosalyn).

…the first one was actually a little bit shambolic because I got a call on the morning of the appointment and I think it was due to be at about ten o′clock and I got called at about nine from my midwife to just say, ‘Did you get any message last week to say your appointment has been moved?’ And I said, ‘No, I haven’t had a call at all,’ and she said, ‘Oh, I thought not.’ (Vanessa).

Speaking to different clinicians each time meant women having to talk through their history repeatedly. This was difficult if there were traumatic experiences in a woman’s past. It also risked being given slightly different advice each time, which was confusing. Often, women just needed reassurance that what they were experiencing was normal. They were left feeling anxious if the only contact they had was a phone call and less supported than if they had met in person. This was the case even when they already had children:

I’m more confident being a second time mum that I can use my judgement on all of these things but having that reassurance would have been helpful and I think it would have made me feel less worried and anxious. (Scarlett).

Lack of physical care left women, particularly first-time mothers, anxious that they might be missing something. Concerns were most often about the baby, rather than themselves:

…there is this terrible fear that there is something that you are doing wrong or are not noticing with the baby that more experienced people would go, 'Obviously it’s this' or, 'You mean you haven’t done this?' It puts the onus very much on us to freak out about the right things and just get as much knowledge as possible, so we know what to do. (Stella).

Women appreciated being able to speak to Healthcare Professionals (HCPs), but the potential for confusion or misunderstanding was acknowledged when the only contact was by telephone:

Because if it’s only on a phone call then there is a lot of interpretation that is put on us and on the person on the other end of the phone. The bandwidth of communication is quite low compared to being in person. And I think, again, that is a bit tough. (Stella).

Despite concerns over lack of face-to-face provision, opportunities for in-person support led to apprehension:

Normally if it wasn’t for COVID I would have been like, I am worried about this, I am going to call up and hopefully go in, but I was so conflicted. I am weighing up a risk. I am worried about my baby, but equally if he is fine then I am going into a hospital in the middle of a pandemic and could get something which is damaging to my baby. (Raquel).

If women were attending physical appointments, they often had to go alone, which was very hard for those who had anticipated sharing the experience with their partner:

The thing that I found really hard was that you had to go to all the appointments by yourself and you couldn’t have a partner with you when you were having the baby. It was kind of cruel because it was such a stressful time and it felt very old-fashioned, like this is a woman’s problem, the woman has the baby, when really you sort of think well it’s taken two to make this baby… (Hattie).

For some women relational care was completely lacking and being without partners was then unbearably lonely:

I had the epidural, and I was so dirty. I was covered in blood. The bed sheets were really bloody where they had moved me across. I thought, surely someone is going to come and offer to… I would have done it myself. I understand they are so busy, but nobody even came to offer me clean sheets. I don’t think it helped that it was so unbearably hot because everything felt so disgusting, dirty, sticky, and horrible. It was such a shock that not one person even came and said hello or explained what was happening now. (Rosalyn).

Even when relational, face-to-face maternity care was available, it was a very different experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. The personal protective equipment (PPE) worn by staff was an important factor in this:

It felt really strange, and it felt a bit alien and it definitely made things feel far more clinical. […] They all had a mask on, which then felt like it was quite difficult to communicate with them and to hear them properly as to what was going on. (Zara).

…it’s odd to spend the best part of two days somewhere where they are giving you care, and they are interacting with you, but you can’t see their face. It is strange. (Vanessa).

It took adjustment getting used to receiving care from staff whose faces were not visible, but the use of PPE was nevertheless often found to be comforting:

When they did get it in [PPE], I felt more comfortable. It made things a bit more difficult, it made things less friendly and personable as it had been before. It felt less nurturing in a way, but I understand it. (Raquel).

The counterbalance for lack of relational care was the reassurance women found in the quality of care they were offered despite the restrictions the pandemic imposed. Although some women missed the relational care face-to-face appointments provided, others recognised the benefits of a less hurried telephone conversation:

It was quite interesting really because I didn’t mind that it was on the phone and actually because it was on the phone, I felt like we could have more of a chat, and it was less of an appointment. Normally obviously you go and have your appointment and they do the regular things they need to do and the checks and things, but you don’t really feel like they’ve necessarily got time to talk to you about worries and things… (Felicity).

In general, women reported being pleasantly surprised by the more streamlined approach to care (than in previous pregnancies) and often felt safety had been prioritised in the service:

I felt that it was much more centralised and much more co-ordinated now [compared to previous pregnancies], which made quite a big difference. Even things like, for example, they were coordinating appointments to be on the same day and if I was running late for one because of the other, then they would tell the other clinic. Things like that. (Mandari).

I think the appointment was a lot faster. It felt like… And maybe it would have been anyway, but it did feel as though they had tightened things up to do just what they needed to do. And there was more of a process, the waiting area and being taken through and whatever. It all felt pretty safe. (Carolyn).

I was surprised by how fine it felt. I thought it was going to be really scary, but it wasn’t. They had all the measures in place, and it got more and more stringent as time progressed. Everyone in face masks, we had temperature checking and hand gel at the entrance. I was a bit apprehensive about it, but the whole time I was in there after the first visit it felt like business as usual for me anyway. (Rosie).

Somehow, even though the service was more streamlined, women did not feel rushed in the way they had previously been:

…they were reassuring and gave me all the time I needed to ask any questions. I wasn’t rushed out of any of the appointments and some of them took a while because I had a long list of things I wanted to ask. They gave me all the time in the world… (Vanessa).

The fact that staff were facing similar uncertainty to women, seemed to create a feeling of solidarity that was appreciated by the women:

… there was this solidarity of: we are all in the shit now. We have all got to pull together and figure this out. With <name of first child> it felt like it was just me. Everyone else was normal and I was losing it. Here, everyone was losing it, so we had to hold it together. (Samantha).

There was recognition staff were also having to navigate their way through a changing situation that created challenges in delivery of care and the need to keep everyone safe. Even though the situation was frightening at times, the honesty that resulted from the uncertainty was easier for women to manage than hollow reassurances would have been:

[I felt] really scared, but I felt like they were being honest with me, if I’m honest. At the time, if they had said to me, ‘We will figure out how to do it however you want,’ it would have been a lie. I appreciated the fact that they were being honest with where we were at the moment. (Samantha).

3.2. Trying to keep everyone safe vs. Denying the embodied experience of pregnancy and birth

Appreciation for the NHS, the service, and care received was evident:

A lot of the onus was being put on hospitals and midwives. When I saw the midwives, I really felt they had done a brilliant job in adapting, but I felt quite sorry for them. It was quite a stressful time for them. (Ava).

Women realised that the emerging situation and rapidly changing advice created difficulties for staff:

I was conscious, people were adapting as they went along. There was no rule book about what to do here. It wasn’t like 'right, we’re in this protocol; let’s get it out of the cupboard and dust it off'. People were looking at it and thinking well for this week, on this day, this is the guidance, therefore we’ll do this. It might all be different in a week’s time. So, I thought, appointment-wise, everyone handled it pretty well. (Mandari).

Despite the distance created, the precautions staff took were welcome:

To be honest I was just so grateful that they were seeing me that I would have done anything. I thought it was all right and I felt quite reassured that precautions were being taken. (Tabitha).

…none of it was a surprise; they would let you know what situation you were going into, and they would all apologise at the beginning for the amount of PPE they were wearing. Which no apology was necessary, really. As I said, I found the more PPE, the more reassured I felt, frankly, at that point. (Stella).

While some women were anxious about the need to go to hospital, others were confident that they would be safe.

I trusted that the hospital would manage the risk. If I felt I needed to go to the hospital, I wasn’t going to stay at home because I might have got coronavirus. I know that probably some other women would have approached that differently and not gone in if there were any issues, but I trusted the hospital. (Hollie).

Restrictions were often not ideal for women, but they recognised the protection they offered:

…my husband couldn’t come with me to the hospital, which I totally respected, and I totally agreed with the whole approach of the hospital and how they dealt with it, that the husbands couldn’t come, the children couldn’t come, only a single person could go, because I think it protected us all, to be honest (Katarzyna).

One approach taken by staff to keep everyone as safe as possible, was to encourage women to stay at home for as long as possible during early labour. This was an issue for some of the women whose embodied experience did not seem to mirror staff expectations. Women reported feeling their labours were progressing rapidly, but they were still discouraged from going to hospital because contractions were perceived by HCPs to not yet be frequent enough:

Contractions were getting stronger and stronger. About midnight, we called labour ward and let them know what was happening with the contractions. They asked me some questions about our daughter and the birth and labour with her. They felt I was managing well at home and asked me to stay at home. They said I should have a bath. (Elena).

Elena believed that labour was progressing quickly, but despite a follow up phone call to labour ward, she was still advised to remain at home as her contractions were not frequent enough. As she feared would happen Elena had strong urges to push and a stressful journey to hospital followed:

Anyway, we managed to get to labour ward and he was out in five minutes. It was really stressful in that sense because I felt he was either going to come at home, on the journey to the hospital, or in the hospital corridor. I felt that was because I was told to stay at home for so long. (Elena).

Like Elena, one other woman in our study arrived on labour ward shortly before the baby’s birth, but a further woman’s baby was born before she got there.

Women, especially those who already had children, would have appreciated being more involved in decisions about their care. Instead, they reported feeling that they were an inconvenience, and that their own knowledge about their bodies and medical history was not acknowledged, which proved to be a further source of frustration for them:

I just want to be believed, when I say that I am really feeling the pain and when I say that the baby is near, I just want you to believe me because I’ve had two children now and I know how these inductions go for me. I just want to be believed, that it is actually going to be quite soon and that whatever your internal examination might say, it is nevertheless going to be quite soon. (Mandari).

Mandari’s baby was ‘born along with the speculum’ that the midwife had been using to examine her. Her husband missed the birth because she had not been able to call him as she was ‘not in active labour’. This issue of not being deemed to be in active labour was difficult for women:

Now I look back and I think 'Oh my god, I cannot believe how they dealt with me.' Because I don’t think it was even a midwife, I think it was one of the doctors that were there, turned round and said, 'You have to be in established labour, my dear, for us to give you the epidural.' And it was the way that she said, 'My dear', I will never forget just that patronising… (Faith).

This was especially so when it meant that they were having to manage pain alone.

I know that there’s a rule, but no one should have to go through a night of pain on their own like this. (Mandari).

3.3. Removed from support network vs. Importance of being at home as a family

When lockdown first began, partners were not able to be with women in hospital until labour was established. As such, an important element of their support network was denied, whilst being difficult for partners too:

So, I didn’t feel like I was coping particularly well at that point and my husband was quite stressed because he was sat in the car park at this point, wondering what was going on and what was happening. (Scarlett).

The situation was similar after the birth and going home was often assessed as the better option:

So once again I’m alone in a room. It was hard because obviously I had a caesarean, so if I had to feed the baby or the baby was crying it was really difficult to support her because I was in so much pain, so to get up to get her was really hard because I really wanted my partner there. (Beatriz).

I wanted desperately to get home because I thought as soon as I get home, I am going to have more help than I have in the hospital and at least my husband will be there (Samantha).

However, once discharged from maternity care in the early waves of the pandemic, many women still felt isolated and alone. Pre-COVID women had visions of what pregnancy and life with a new baby would be like, whilst the reality during the pandemic was very different:

…it’s quite hard being at home all the time with a young child without having family around us and friends around us that we ordinarily would have done as well. (Scarlett).

The people women would normally have turned to for support were no longer available to them:

It has not been this lovely, fluffy advert for me. It has been really tough, and I wish I could have picked up the phone and told my mum to come round now because I need her. I have not been able to do that. (Raquel).

Women felt cheated of the maternity leave experience they had anticipated and the activities they imagined they would be enjoying with their babies:

I do remember early on feeling a bit robbed, because I had been really looking forward to maternity leave and having a baby and I had all these images of what we might be doing with our days. So, I remember feeling quite robbed of that. (Alexa).

They felt that they had missed out on opportunities that would normally have been available to them and were also concerned about the impact of the situation on the baby and siblings:

We were very much left to fend for ourselves. No one was coming in to meet [the baby], to take [older sister] out to the park and give her some of her own space. Loads of elements of new baby life we lost. (Elena).

Women were sad that the birth of their baby during the pandemic was not hailed in the way other, pre-pandemic births had been:

I felt really isolated because nobody was coming, and we weren’t allowed over. It feels like <name> wasn’t a celebrated baby…. There has not been any fanfare for him. (Samantha).

The lack of shared time with friends, family, and other loved ones was a source of regret:

People have said to me, 'You get inundated with visitors when you have just had a baby and it can be quite annoying actually', and I would give anything for that at the moment because it is just the complete polar opposite. (Vanessa).

Yet there were positive aspects too. The imposition of social distancing during the pandemic meant intrusions during pregnancy women had been warned about did not materialise:

And with the pregnancy I had heard quite a lot of people say, 'Oh it will be horrible: you’ll have loads of people giving you advice; you’ll have loads of people trying to touch your belly.' And obviously I never had any of that because I didn’t see anyone. (Tabitha).

The ‘flip side’ for the woman who did not feel that her baby was celebrated because of the pandemic, was the chance to be together as a family unit:

It felt really relentless from a pandemic point of view. Everything feels grim. The first few months felt a lot like that there. There was no help, no support… It feels a bit sad, but the day-to-day life has been great because we are all here together. (Samantha).

Others recognised benefits as well and raised how there had been renewed importance of the immediate family as guests and visitors were not permitted to visit them:

…my husband was furloughed and has now been made redundant. That is stressful, but equally, my God, I am so happy that my husband has been around for the last seven weeks and will continue to be around for a few more weeks before he needs to start looking at setting himself up with some work. It is very 50/50 for me. I think lockdown has had some really good benefits. My final trimester, I didn’t have to commute. I got to spend all of that time with my husband. That never would have happened in normal life. (Raquel).

I’m starting to come round to going 'Actually, this was a brilliant time to have a baby', because yes, it’s very rare that my husband would be at home so much, and you get to spend a lot more quality time together. So, it’s weird to feel positive about a pandemic because obviously I know a lot of people have had a really bad time with it, so it’s kind of mixed feelings. (Imogen).

The opportunities for bonding as a family unit were noted by several women:

He [husband] spent so much time at home which has been such an amazing support, and also allowed him really to bond with <baby> in a way that he wasn’t able to bond with <first child>. He only went back to work at the start of term last week, so it’s been fantastic, the bond that they’ve got is so much stronger and he feels so much more confident with them. And this quality time where we had to stay indoors has been so lovely. (Jacqueline).

However, the tension between being separated from wider family members and together as a nuclear family unit was often alluded to as a situation of ‘swings and roundabouts’:

[grandparents being unable to visit] is tough, but in other respects it has been quite nice to just have the three of us here, to be at home and have an excuse to not have anyone round and get used to stuff. It is swings and roundabouts really. (Rosie).

The fact women were not able to leave home and socialise relieved the pressure new mothers often feel:

I remember with the others; people would say 'you’ve got to try to get out every day' and I would be thinking 'have I really got to try to get out every day? I just don’t want to have to get out; it’s a real performance getting everyone up and out of the house. Can I not just make a little nest and stay at home?' And so actually having all of that removed makes it easier. It personally suits me in some ways. (Mandari).

The same was true of the need to entertain visitors:

…we didn’t really have the stress of lots of visitors, we just got into our own little groove, and we were able to focus on trying to get him to sleep. And I guess we had some quiet time once he was in our world, which definitely has been lovely. We’ve had a lovely time to bond with our baby, essentially, so there’s definitely been some positives in the situation as well as the negatives, I guess. (Gillian).

The opportunity to re-think priorities and expectations following the birth of a baby was an unexpected and welcome opportunity that in part mitigated the many difficulties women had faced. To some, this was felt as a uniquely positive experience, which they would recommend for future pregnancies:

If I have another baby, it is lockdown for three weeks. Nobody is coming anywhere near us except for close family. They can come and sit in a dirty house and that’s it! (Hollie).

3.4. Interpretation of the theory: Navigating uncertainty alone

The themes we have presented in the form of three dyads relating to women’s psycho-social experiences of pregnancy and childbirth during the COVID-19 pandemic, counterbalanced one another. Women were feeling their way through maternity care at a time that service provision had changed, and an evidence base was lacking. This was a time of great uncertainty when it was feared pregnant women would be particularly vulnerable. Due to social restrictions implemented to curb the spread of infection; networks women would normally rely on for support were not available in the community. The need to minimize the risk of COVID-19 transmission amongst healthcare staff and service users meant that face to face care was limited and the usual relational provision was missing. There were restrictions on who could accompany women into hospital and at what stage of their labouring journey birth partners could join them. Together, these factors meant women were ‘Navigating Uncertainty Alone’. However, although our data suggest the experience of pregnancy and childbirth was not entirely positive, neither was it wholly negative. Despite the fact women were navigating uncertainty and having to do it without the support they would have anticipated,they understood why their care had to be different and appreciated efforts to keep them safe. Many discovered that the pandemic had removed pressures to socialise and entertain, which meant less stress and more focus on the immediate family unit. Due to home working for many partners during lockdown, there were opportunities to develop bonds that would not have been possible before the pandemic. By presenting this analysis and interpretation, we theorise that the population of interest (women), who experienced the phenomenon of interest (pregnancy and childbirth), in the context of interest (the COVID-19 pandemic), not only had to navigate the uncertainty of pregnancy, but had to do so whilst also navigating a global pandemic of a scale not known to living memory, and moreover had to do so alone. By stating women who were pregnant and gave birth during the COVID-19 pandemic, navigated these uncertainties alone, we suggest this as a distinct and unique experience which could have only occurred due to the circumstances of the population, phenomenon, and context coming together which left maternity care services reconfigured and women in a state of flux about their maternity care. Future research may wish to test this theory by altering the context, to see whether similar experiences are recorded by pregnant women and new mothers during other health system shocks, such as natural disaster (e.g. earthquake, hurricane, or tsunami), systemic catastrophic failure (e.g. industrial/urban conflagration or smog), or human intervention (e.g. terrorism or war).

4. DISCUSSION

During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, the participants of our study were ‘Navigating Uncertainty Alone’ in a frequently changing landscape. Initially the likely impact on maternity service delivery was unknown. Concern over availability of ambulances for women birthing in settings that were not co-located [8], led to reconfiguration of services. Midwifery units were closed, and home birth services were often withdrawn [44]. The ambivalence felt when face to face appointments were offered is understandable given the policy context. The UK Government’s advice about maintaining social distance [7] was concurrent with reminders to women about the risks of not attending maternity care [8]. The importance of keeping scheduled appointments was stressed but women were warned that the number of appointments might be reduced. As found by other authors [11], [44], women in our study reported reduced postnatal contact, and the replacement of in-person care with video conferencing or telephone calls [12]. These virtual appointments compounded the anxiety often experienced by women during pregnancy and the early postnatal days [12], [45]. Women were uncertain as to whether they were right to be concerned about issues that were worrying them. They lacked confidence in clinicians conducting remote consultations and remained unconvinced that nothing had been missed during these virtual interactions.

Relational care for women in hospital was disrupted by PPE. The wearing of masks removed facial expression as a form of non-verbal communication. Nevertheless, women appreciated the protection afforded by PPE and found it reassuring. In common with other research [22], [44], [46], the women we interviewed valued efforts staff were making to care for them in challenging circumstances. They realised that the emerging situation and rapidly changing advice created difficulties for staff too. The speed at which these changes were happening during the initial lockdowns in the UK is evidenced by the fact that by October 2020, there had been twelve updates of the COVID-19 in pregnancy guidance issued by the RCOG and RCM [8], [10]. Women recognised staff were also navigating uncertainty, and welcomed honest responses to questions, even if that meant reassurance was not available. Women experienced a more streamlined antenatal service, yet, also seemed to be given time to ask their questions without feeling hurried.

Women understood the reasons for being asked to attend appointments alone but regretted not being able to share the experience with partners. This was often stressful for women who were worried they may have forgotten important information. Although difficult antenatally, the situation was compounded during labour. Guidelines advised women should be allowed to have a birth partner present with them for labour and birth [8], [10], but this was more often than not interpreted as a recommendation for ‘established labour’. Women were encouraged to stay at home until staff deemed their contractions met criteria required for admission, meaning women’s embodied experiences were habitually denied. The consequent lack of agency was frustrating and stressful, as mothers worried their babies would be born before arrival at hospital, as happened with one participant in this study. Those who were admitted before labour was established, struggled to cope without support, as partners were often left in the car park wondering what was happening. There was, therefore, no one to advocate for women when they felt their embodied knowledge was ignored. It could be said that not only women were navigating uncertainly alone, but so too were their partners. The importance of social support during labour is well-established [47], [48] and the impact of disrupted maternity care [12] and isolation from social restrictions on the psycho-social support and emotional wellbeing of pregnant and postpartum women [18], [22], [45], [49] and their partners cannot be underestimated during labour or postnatally.

The need to comply with social distancing restrictions meant hospital policies usually excluded visitors, including partners, from visiting antenatal and postnatal wards. Early postpartum, women (especially those who had received epidurals or undergone Caesarean births) needed practical help, such as reaching for the baby. As they were conscious of the pressure on staff, they were reluctant to call for help. This left women feeling incredibly lonely and desperate to go home; however, being at home was also isolating. Visiting friends and family was not permitted during the first lockdown [22]. It was not until 1st June 2020 that people could ‘get together’, but this was only outdoors in groups of up to six. This meant women were not able to access their usual support networks and they often felt isolated [12], [22], [44], [50]. Navigating uncertainty alone therefore extended to the early days of parenting. In common with other studies [50], [51], women regretted the lack of opportunity to introduce their baby to the wider family and friends. However, there were unexpected advantages: ‘Navigation’ implies new parents were finding their way, and this was illustrated by counterbalancing themes identified. There were ‘two sides of the coin’ for women. Removal from support networks meant women discovered benefits of the immediate family unit without intrusions from friends and loved ones during early postnatal days. There was no longer pressure to open homes to friends and family, and the need to work from home, where possible, created opportunities for both parents to bond with the baby [50]. These factors made the postnatal period restorative and allowed mothers to set pace for their next journey as a new parent.

4.1. Strengths, limitations, & future directions

The strengths and limitations of the research portfolio have been reported previously [12]. The limited demographic diversity of our sample is reflected in studies from elsewhere [51], but was disappointing given the strategies used to recruit a more diverse study sample. Future research should pay careful attention to recruitment of diverse and often understudied populations [52], including those who are: unmarried or not co-habiting; lesbian, gay, bisexual, non-binary, or transgender; or those experiencing severe mental illness or living with high levels of social complexity. Finally, and in-line with the discussion of the interpretation of the theory mentioned above, we support ‘testing’ this theory in different contexts which result in health system shocks, to see whether this theory holds true, or whether the experiences of pregnancy and childbirth change with the changing health system shock context (e.g., natural disaster, systemic catastrophic failure, or human intervention).

5. CONCLUSION

Our study indicates the impact of service reconfiguration on women and their families during the initial lockdown period. Women had to navigate a very uncertain landscape, without the usual networks of support on which they would usually be expected to depend, including their partner. Their journeys were lonely at times, but despite the challenges, many found unexpected benefits, including the comfort of home and their immediate family unit. With regard to how this can be interpreted and used for future policy and practice in a post-pandemic era – or indeed, in future health system shocks – we would recommend the following. Firstly, careful attention is paid to women who may feel isolated when care and social support is inaccessible or is required to be provided at a reduced capacity. This would require extra checks to be undertaken by the attending clinicians and requires the understanding and assessment of perinatal mental health to be aligned with physical health during and after pregnancy. Secondly, there should be no blanket removal of key aspects of maternity care services from antenatal through to postnatal care. Women’s agency and understanding of their own bodies should be factored into negotiating reconfigurations which take place in healthcare, with access and care for pregnant women being prioritised. Finally, and drawing the previous two points together, we have found that removing regular contact leads to women finding themselves alone with no-one to turn to for clinical advice, guidance, and support. Policy and practice for maternity care going forward should look to prioritise relational care between clinicians and pregnant, birthing, and postnatal women – so that no woman has to navigate this journey alone.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

Ethical approvals were granted by the King’s College London Biomedical & Health Sciences, Dentistry, Medicine and Natural & Mathematical Sciences Research Ethics Sub-Committee, in June 2020 (reference:- HR-19/20–19486).

FUNDING

This project was funded by the King’s College London King’s Together Rapid COVID-19 Call, successfully awarded to Laura A. Magee, Sergio A. Silverio, Abigail Easter, & colleagues (grant reference:- 204823/Z/16/Z) as part of a rapid response call for research proposals. The King’s Together Fund is a Wellcome Trust funded initiative. The funders had no role in the recruitment, data collection and analysis, or write-up associated with this work.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Elsa Montgomery: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Kaat De Backer: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Writing – original draft. Abigail Easter: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Laura A. Magee: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Jane Sandall: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Sergio A. Silverio: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the women who participated in this study, and all those who navigated uncertainty of pregnancy and childbirth alone during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our thanks are also extended to Ms. S. Gibson (NIHR ARC South London), Mr. N. Sarson and Mrs. M. Harris-Tafri (King’s College London), for their assistance in the designing the final figure.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Sergio A. Silverio, Abigail Easter, Kaat De Backer, & Jane Sandall (King’s College London) are currently supported by the National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration South London [NIHR ARC South London] at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. Kaat De Backer (King’s College London) is also currently supported by the National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration East of England [NIHR ARC East of England] at Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust. Sergio A. Silverio is also in receipt of a personal Doctoral Fellowship awarded by the NIHR ARC South London Capacity Building Theme and Jane Sandall is also an NIHR Senior Investigator [Award Number: NIHR200306]. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

PATIENT & PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT & ENGAGEMENT

The KTF Changing Maternity Care Study was discussed at a National Institute for Health Research [NIHR] Applied Research Collaboration [ARC] South London, Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement [PPIE] meeting for maternity and perinatal mental health research in July 2020 (which focuses on co-morbidities, inequalities, and maternal ethnicity); an NIHR ARC South London Work in Progress Meeting in October 2020 (focused on maternity and perinatal mental health research); and at an NIHR ARC South London Public Seminar in February 2021 (focused on COVID-19 rapid response research). From these fora, we sought advice on the design of the study, how best to recruit participants, and on our interpretation of the findings. We also requested support from delegates (both lay and expert stakeholders) at these events to share the details of the study within the local community. These stakeholders included members of the local community, experts by experience, health and social care professionals, researchers, and policy makers.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blumenthal D., Fowler E.J., Abrams M., et al. Covid-19 – implications for the health care system. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383(15):1483–1488. doi: 10.1056/nejmsb2021088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen L., Drew D., Joshi A., et al. Risk of COVID-19 among frontline healthcare workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(9):e475–e483. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.29.20084111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson A.N., Ravaldi C., Scoullar M.J.L., et al. Caring for the carers: Ensuring the provision of quality maternity care during a global pandemic. Women Birth. 2021;34(3):206–209. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kotlar B., Gerson E., Petrillo S., et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal health: A scoping review. Reprod. Health. 2021;18(10):1–39. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01070-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jardine J., Morris E. COVID-19 in women’s health: epidemiology. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021;73:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2021.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knight, M., Bunch, K., Cairns, A., et al., (2021). MBRRACE-UK: Saving lives, improving mothers’ care. Rapid report 2021: Learning from SARS-CoV-2-related and associated maternal deaths in the UK June 2020-March 2021. https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/MBRRACE-UK_Maternal_Report_June_2021_-_FINAL_v10.pdf.

- 7.UK Government (2021). Stay at home: guidance for households with possible or confirmed coronavirus (COVID-19) infection. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-stay-at-home-guidance/stay-at-home-guidance-for-households-with-possible-coronavirus-covid-19-infection

- 8.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and Royal College of Midwives (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in pregnancy: Information for healthcare professionals, 11th ed. The RCOG, London.

- 9.Knight, M., Bunch, K., Cairns, A., et al., (2020). Maternal, newborn and infant clinical outcome review programme. Saving lives, improving mothers’ care. Rapid report: Learning from SARS-CoV-2-related and associated maternal deaths in the UK. https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/MBRRACE-UK_Maternal_Report_June_2021_-_FINAL_v10.pdf.

- 10.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and Royal College of Midwives (2021). Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in pregnancy: information for healthcare professionals, 13th ed. The RCOG, London.

- 11.Jardine J., Relph S., Magee L.A., et al. Maternity services in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey of modifications to standard care. BJOG: Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021;128(5):880–889. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverio S.A., De Backer K., Easter A., et al. Women’s experiences of maternity service reconfiguration during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative investigation. Midwifery. 2021;102(103116):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2021.103116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richens Y., Wilkinson M., Connor D. Guidance for the provision of antenatal services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Midwifery. 2020;28(5):324–328. doi: 10.12968/bjom.2020.28.5.324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meek C.L., Lindsay R.S., Scott E.M., et al. Approaches to screening for hyperglycaemia in pregnant women during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Diabet. Med. 2021;38(1):1–13. doi: 10.1111/dme.14380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harkness M., Yuill C., Cheyne H., et al. Induction of labour during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey of impact on practice in the UK. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(310):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03781-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenfield M., Payne-Gifford S., McKenzie G. Between a rock and a hard place: considering “freebirth” during Covid-19. Front. Glob. Women’s Health. 2021;2(603744):1–11. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2021.603744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silverio S.A., Davies S.M., Christiansen P., et al. A validation of the postpartum specific anxiety scale 12-item research short-form for use during global crises with five translations. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(112):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03597-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fallon V., Davies S.M., Silverio S.A., et al. Psychosocial experiences of postnatal women during the COVID-19 pandemic. a UK-wide study of prevalence rates and risk factors for clinically relevant depression and anxiety. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021;136:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pope J., Olander E.K., Leitao S., et al. Prenatal stress, health, and health behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic: an international survey. Women Birth. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meaney S., Leitao S., Olander E.K., et al. The impact of COVID-19 on pregnant womens’ experiences and perceptions of antenatal maternity care, social support, and stress-reduction strategies. Women Birth. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atmuri K., Sarkar M., Obudu E., et al. Perspectives of pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Women Birth. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson L., De Pascalis L., Harrold J.A., et al. Postpartum women’s experiences of social and healthcare professional support during the COVID-19 pandemic: a recurrent cross-sectional thematic analysis. Women Birth. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chmielewska B., Barratt I., Townsend R., et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health. 2021;9(6):E759–E772. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00079-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Homer C., Leisher S.H., Aggarwal N., et al. Counting stillbirths and COVID 19 – there has never been a more urgent time. Lancet Glob. Health. 2021;9(1):e10–e11. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30456-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silverio S.A., Easter A., Storey C., et al. Preliminary findings on the experiences of care for parents who suffered perinatal bereavement during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(840):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-04292-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glaser B.G., Strauss A.L. Aldine; Chicago, IL: 1967. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montgomery P., Bailey P.H. Field notes and theoretical memos in grounded theory. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2007;29(1):65–79. doi: 10.1177/0193945906292557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gearing R.E. Bracketing in research: a typology. Qual. Health Res. 2004;14(10):1429–1452. doi: 10.1177/1049732304270394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silverio, S.A., Gauntlett, W., Wallace, H., et al., (2019). (Re)discovering grounded theory for cross-disciplinary qualitative health research. In: B.C. Clift, J. Gore, S. Bekker, I. Costas Batlle, K. Chudzikowski, & J. Hatchard (Eds.), Myths, methods, and messiness: Insights for qualitative research analysis (pp. 41–59). Bath, United Kingdom: University of Bath.

- 30.Silverio S.A., Wilkinson C., Wilkinson S. Further uses for grounded theory: a methodology for psychological studies of the performing arts, literature and visual media. QMiP Bull. 2020;29:8–19. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thornberg R., Dunne C. In: The SAGE Handbook of current developments in grounded theory. Bryant A., Charmaz K., editors. SAGE; London, United Kingdom: 2019. Literature review in grounded theory; pp. 206–221. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silverio S.A. Women’s mental health a public health priority: a call for action. J. Public Ment. Health. 2021;20(1):60–68. doi: 10.1108/JPMH-04-2020-0023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wainrib B.R., editor. Springer Publishing Company. 1992. Gender issues across the life cycle. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levers M.-J.D. Philosophical paradigms, grounded theory, and perspectives on emergence. SAGE Open. 2013;3(4):1–6. doi: 10.1177/2158244013517243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silverio S.A. In: How do we Belong? Researcher Positionality within Qualitative Inquiry. Clift B.C., Hatchard J., Gore J., editors. University of Bath; Bath, United Kingdom: 2018. A man in women’s studies research: Privileged in more than one sense; pp. 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farrugia B. WASP (write a scientific paper): sampling in qualitative research. Early Hum. Dev. 2019;133:69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2019.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2017). Clinical guidance [CG190]. Intrapartum care for healthy women and babies. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg190

- 38.Archibald M.M., Ambagtsheer R.C., Casey M.G., et al. Using zoom videoconferencing for qualitative data collection: Perceptions and experiences of researchers and participants. Int. J. Qual. Methods. 2019;19(18):1–8. doi: 10.1177/1609406919874596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McIntosh M.J., Morse J.M. Situating and constructing diversity in semi-structured interviews. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2015;2:1–12. doi: 10.1177/2333393615597674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saunders B., Kitzinger J., Kitzinger C. Anonymising interview data: challenges and compromise in practice. Qual. Res. 2015;15(5):616–632. doi: 10.1177/1468794114550439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heaton J. “*Pseudonyms are used throughout”: a footnote, unpacked. Qual. Inq. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1177/10778004211048379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guest G., Bunce A., Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822×05279903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holton J.A., Walsh I. SAGE Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2017. Classic Grounded Theory: Applications with Qualitative and Quantitative data. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanders J., Blaylock R. “Anxious and traumatised”: Users’ experiences of maternity care in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Midwifery. 2021;102(103069):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2021.103069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jackson L., De Pascalis L., Harrold J.A., et al. Postpartum women’s psychological experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: A modified recurrent cross-sectional thematic analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(625):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-04071-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pilav S., Easter A., Silverio S.A., et al. Experiences of perinatal mental health care among minority ethnic women during the covid-19 pandemic in London: A qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19(4):1–15. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19041975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bohren M.A., Hofmeyr G.J., Sakala C., et al. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev., 7(CD003766), i- 2017:4. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003766.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bohren M.A., Berger B.O., Munthe-Kaas H., et al. Perceptions and experiences of labour companionship: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019:85. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012449.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bridle L., Walton L., van der Vord T., et al. Supporting perinatal mental health and wellbeing during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19(3):1–12. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riley V., Ellis N., Mackay L., et al. The impact of COVID-19 restrictions on women’s pregnancy and postpartum experience in England: a qualitative exploration. Midwifery. 2021;101(103061):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2021.103061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ollivier R., Aston D.M., Price D.S., et al. Mental health & parental concerns during COVID-19: the experiences of new mothers amidst social isolation. Midwifery. 2021;94(102902):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2020.102902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fernandez Turienzo C., Newburn M., Agyepong A., et al. Addressing inequities in maternal health among women living in communities of social disadvantage and ethnic diversity. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(176):1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10182-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]