Abstract

This review article addresses challenges in the management of UNESCO Biosphere Reserves (BRs) by analyzing the value of research published in journals, chapters, and books that are not indexed by Web of Science or Scopus. This widely ignored body of grounded knowledge allows deeper insights when assessing participatory management of BRs, an imperative reflected in guiding principles such as Aichi Target 11. The scoping literature review conducted found 120 publications that address stakeholder participation in decision-making and the economic benefits generated in Mexican BRs. Only 65 of those studies were published in indexed journals, while national outlets accounted for the other 55, most of them also peer-reviewed publications. International papers differ from national ones regarding spatial coverage, research foci, and the methods applied. Though both bodies of publications identified similar challenges, each sheds a distinct light on social-environmental contexts and regions. However, there is a consensus that genuine stakeholder participation has not yet been achieved.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13280-021-01672-1.

Keywords: Biosphere reserves, Governance, Mexico, Participation, Scientific knowledge

Introduction

We argue that literature reviews continue to focus on research published in international journals (usually with high impact factors), inevitably ignoring “other” case studies based on distinct contexts, theories, or concepts (Alatas 2003; Baber 2003; Meriläinen et al. 2008; Ergin and Alkan 2019; Sengupta 2021) that address different topics, apply distinct methods, and may well draw diverse conclusions (Konno et al. 2020). Strong evidence suggests that the origins of editors and referees, publications, and review practices (Altbach 2013), as well as the mandatory use of English (Aalbers 2004), combine to generate multiple biases that favor the Western academic traditions, perspectives, and institutional organizations that evolved in the United States and the United Kingdom after World War II (Müller 2021). As Gutiérrez and López-Nieva (2001) and Ergin and Alkan (2019) state, scholars at prestigious American and British institutions wield considerable influence over the topics, theoretical approaches, methods, and results that appear in international journals. Consequently, “other research”, published in different languages and scholarly outlets, is often virtually invisible to the international scientific community (Kratzer 2018). To provide a more inclusive review, we proposed identifying, categorizing, and comparing international and national research related to a specific topic and region.

Accordingly, we will show that research published in non-internationally indexed journals makes significant, but largely ignored, contributions to assessing the outcomes of public policy measures designed to foster stakeholder participation in decision-making and economic benefits in UNESCO BRs. A comprehensive review of this nature, elaborated to address these issues through a focus on Mexico, is worthwhile for several reasons.

First, efforts to foster conservation at the international level stress the imperative of stakeholder participation in decision-making and of an equitable distribution of economic benefits. In 2010, the parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) agreed on the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity, which includes the oft-quoted Aichi Target 11 related to protected areas (PAs): “By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water areas and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative, and well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscape and seascape” (CBD 2010; emphasis by authors).

Second, in Mexico, as in many other countries, establishing terrestrial and, more recently, marine BRs1 is a key strategy for achieving this target. BRs should foster integrated landscape management by means of meaningful participation in decision-making and the distribution of economic benefits among local resource users, regardless of the agency that is formally in charge of management (Gannon et al. 2019), so they are intimately related to the aim of being “equitably managed” (see above). Therefore, according to the IUCN’s classification of governance regimes, BRs require a “shared governance” approach (Borrini-Feyerabend et al. 2013). In addition, and in accordance with the UNESCO paradigm, BRs should enhance equitably distributed economic development at the regional and local levels (Kraus et al. 2014; Carius and Job 2019).

Third, Mexico is one of the pioneers in establishing BRs to implement the UNESCO paradigm on the ground, which explains why we chose to focus our analysis there. The earliest ones (La Michilía and Mapimí in the semi-arid northwest, and Montes Azules in the tropical southeastern lowlands) were declared in the late 1970s (Sada Guevara 2020), just a few years after the UNESCO’s BR concept was implemented by designating the first reserves in 1976 (Job et al. 2019). The inclusion of local resource users (small-scale farmers, cattle-breeders, indigenous people) was promoted from the outset, mainly by informing stakeholders at an early stage and through participation in day-to-day management (Halffter 1981, 2011; Andrews 2006), though not necessarily in strategic decision-making (Brenner 2019, 2020). In the ensuing years, prominent Mexican conservationists (Gonzalo Halffter and Arturo Gómez Pompa, among others) were influential at the international level, especially between the establishment phase of BRs (1976–1982) and the groundbreaking Second World Congress of Biosphere Reserves in Seville in 1995, when an innovative paradigm for modern BRs was defined (Durand et al. 2011; Sada Guevara 2020).

In this context, the so-called “Mexican Model of BRs” has been promoted by a group of conservation biologists at Mexico’s largest university (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México). This explicitly inclusive national paradigm of PA establishment and management was deemed highly influential during the preparation of the Seville Strategy (1983–1995; see Halffter 1981; Durand et al. 2011; Sada Guevara 2020). Those authors argue that the Mexican Model shaped the policy guidelines of the Seville Strategy. As a result, the traditional “Yellowstone-Model”, based on strict conservation and centralized administration, came to be considered unfit for the often densely populated, poverty-stricken natural areas of the Global South (Simonian 1995; Halffter 2011; Durand 2019). Instead of top-down management and “fines and fences”, the Mexican multi-stakeholder approach of shared governance (Borrini-Feyerabend et al. 2013) emphasized, from the late 1970s onwards, the non-manipulative participation of local communities and resource users in management activities, and the distribution of economic benefits (Brenner and Job 2006; Brenner 2020). The ultimate goal of the Mexican Model was to resolve the trade-off between conservation and regional economic development (Simonian 1995; Durand et al. 2011; Halffter 2011). This ambitious aim was recognized internationally at the Seville World Congress (1994) and became a key goal of the Seville Strategy that seeks to foster sustainable regional development in BRs (UNESCO 1996; UNESCO 2008; Sada Guevara 2020).

Fourth, all 44 BRs2 in Mexico declared by national legislation according to the UNESCO paradigm are (at least formally) managed according to the “Mexican Model” and regulated by the Federal Law on Ecological Equilibrium and Environmental Protection (LGEEyPA for its acronym in Spanish, passed in 1988). Consequently, several participatory PA-related management strategies have been developed and applied over the last four decades (Durand et al. 2014; Brenner 2019). However, consensus is lacking on whether, and to what extent, the effective participation of local populations and stakeholders has been implemented in Mexican BRs (Reyes-García et al. 2013; Brenner 2020). Thus, there is ongoing debate on the degree of success that the Mexican Model has enjoyed in implementing “shared governance” according to the IUCN typology, in which “representatives of various interests or constituencies sit on a governance body with decision-making authority and responsibility, taking decisions together” (Borrini-Feyerabend et al. 2013, p. 32). In this context, several authors (Paré and Fuentes 2007; Durand and Vazquez 2011; Brenner and Job 2012; Méndez-López et al. 2014) have concluded that Mexican BR management is still based essentially on traditional “governance by government” (following the IUCN classification), since central institutions tend to implement legal norms and measures with no genuine, meaningful stakeholder participation. There is also evidence that the economic benefits generated by sustainable activities such as ecotourism have turned out to be insufficient to significantly enhance the livelihoods of traditionally marginalized groups (Durand et al. 2014). Moreover, in many cases, income and employment opportunities seem to be distributed unequally among local populations (Brenner and San Germán 2012). Several other studies, however, have shown that progress has been made in fostering the meaningful participation of local stakeholders in decision-making (Díaz Ávila et al. 2005; Brenner 2019, 2020) and the income generated (Mayer et al. 2018).

To address the question of whether, and to what extent, the goal of fostering participation in decision-making and the distribution of economic benefits has been achieved in Mexican BRs from an academic perspective, we conducted a scoping review of case studies that included peer-reviewed international journal articles (indexed by the Web of Science Core Collection and Scopus). We call these, “international research publications”. But we included other peer-reviewed journals (generally indexed nationally in Mexico, other Latin American countries, and Spain), and peer-reviewed books and book chapters, which we call “national research publications”. The decision to consider research not published in leading international journals was based on the assumption that much academic knowledge would be omitted by ignoring the wide range of cases published mainly in Mexican and Latin American journals and books.

Our five research questions were:

Do international publications differ from national ones when analyzing the outcomes of attempts to implement Aichi Target 11 and the Mexican Model?

Do international and national publications differ on the key factors that foster or impede stakeholder participation in decision-making and economic benefits?

Do international and national publications differ in terms of the regional distribution of case studies, the analytical methodologies applied, and the causes of the lack of stakeholder participation in decision-making and economic benefits?

Are contributions by Mexican scholars publishing mainly or exclusively in national outlets likely to be overlooked?

Does considering research from national publications enhance our understanding of the challenges that BR management faces at the local and regional levels?

Methodology

As mentioned, to identify and select the broadest possible variety of case studies published in international and national outlets, we conducted a scoping review that, according to Pham et al. (2014, p. 371), “aims to map the existing literature in a field of interest in terms of the volume, nature, and characteristics of the primary research”. Unlike systematic reviews, scoping reviews do not necessarily imply mandatory critical appraisal, assessment of risk of bias, or quantitative syntheses of findings from individual studies (Munn et al. 2018, pp. 18–43). Hence, our strategy was to conduct keyword search in the Web of Science Core Collection (including the Social Science Citation Index, Science Citation Index Expanded, Arts & Humanities Citation Index, Book Citation Index) and Scopus. In addition, we used an updated institutional subscription provided by one of Mexico’s leading universities (Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana) to search the regional database SciELO Citation Index.

The original search conducted in December 2019 was updated in June 2020. To search systematically for case studies published in national outlets (i.e., peer-reviewed journal articles not included in the Web of Science Core Collection or Scopus, as well as books and book chapters in Spanish) we accessed electronic libraries and databases provided by the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana using the same keywords and Boolean operators (see below). In addition, a snowball method for reviewing references cited in articles, books, and book chapters that met the eligibility criteria was applied to cross-check results and track additional publications (see ESM S1 for further details).

For all the electronic databases, the following keywords and Boolean operators were used as search terms (in English and Spanish, search by title and abstract): (“Biosphere* Reserve*” AND “Mexico” AND “Participation”), (“Biosphere Reserve*” AND “Mexico” AND “Inclusion”), (“Biosphere Reserve*” AND “Mexico” AND “Exclusion”), (“Reserva* de (la) Biosfera” AND “México” AND “Participación”), (“Reserva* de (la) Biosfera” AND “México” AND “Inclusión”, and (“Reserva* de (la) Biosfera” AND “México” AND “Exclusión”).3 Duplicates were detected and removed by comparing the search results from the Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus, electronic libraries, and other databases provided by the aforementioned university. We faced limitations due to the lack of comprehensive national databases which would have allowed a systematic search for Bachelor, Masters, and Doctoral theses, as well as unpublished technical reports commissioned by government institutions or NGOs. Therefore, it was virtually impossible to include this “gray” literature in our search.

Following recommendations in Haddaway et al. (2020) and O’Leary et al. (2016), the study team (two scholars working in the field of PA management research) elaborated and applied simultaneously two different a priori procedures to define search strategies and eligibility criteria (ESM S1). The eligibility criteria for the screening methodology were: (a) publication dates between 1981 (first relevant article on Mexican BRs) and June 2020; (b) abstracts and full texts that refer to participation in the establishment and/or management of Mexican BRs and the generation and distribution of economic benefits generated in BRs (natural scientific literature with no social component was excluded; and (c) formally published research based mainly on case studies of one or more BRs and general assessments of participation in Mexican BRs that used fieldwork or other methods to generate and analyze quantitative data and/or qualitative information. Screening was carried out independently by the two members of the research team by revising title, abstract, and—if applicable—the full text. Search results were compared and discrepancies regarding eligibility were resolved during several meetings.

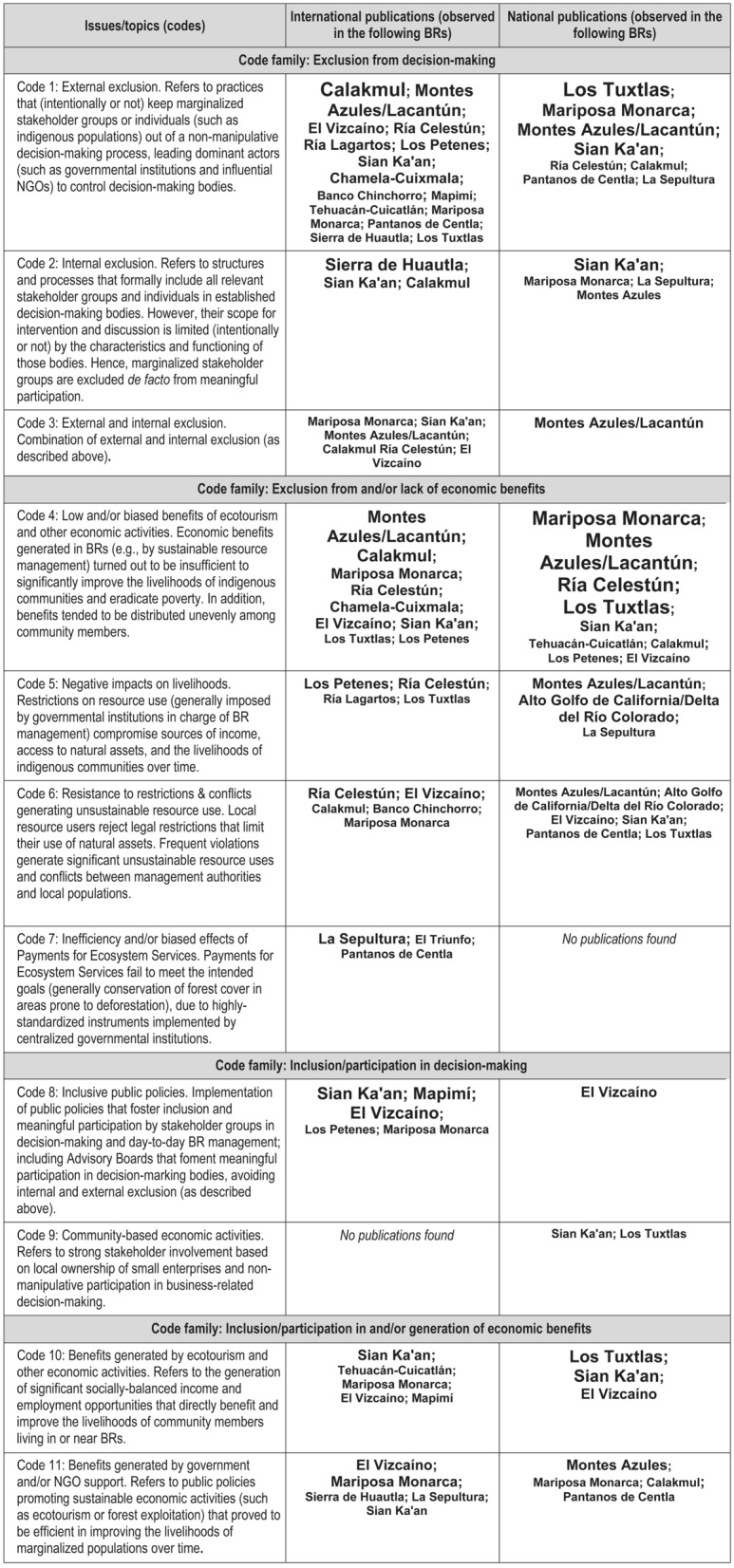

All publications selected were reviewed in this way and registered on an Excel Spreadsheet according to the following criteria: title, summary, publication date, institutional affiliation of the first author, guiding theoretical approach, research methods applied, location of study areas, and the specific topics and problems highlighted. Subsequently, qualitative inductive and iterative coding was applied to systematically summarize study results and synthesize findings qualitatively. As a result, study findings (full texts) were coded after defining 11 major codes classified in 4 code families (see Table 1 for the code list, code descriptions, and BRs included). Codes were defined following an inductive approach, applying open coding to categorize results. Throughout this process, team members discussed the codes and definitions.

Table 1.

Research foci of international and national publications (all 120 publications were coded; text size indicates the relative frequency of the 107 coded publications based on 117 case studies conducted in specific BRs)

In addition, theoretical approaches and paradigms related to the governance of BRs were categorized qualitatively. We applied inductive coding according to the focuses addressed—explicitly or implicitly—in the respective sections of the literature review and the references cited. As a result, five general categories for theoretical approach were identified, broadly supported by empirical evidence: (1) political ecology; (2) environmental governance; (3) citizen/stakeholder participation; (4) socioeconomic factors that caused changes in land use and factors that determined the impacts of ecotourism; and (5) narrative descriptions based on professional experiences with no reference to specific theories or paradigms. Regarding the research methods and techniques applied, we classified publications as: (a) qualitative; (b) quantitative; and (c) mixed method techniques.4

Results

Descriptive statistics

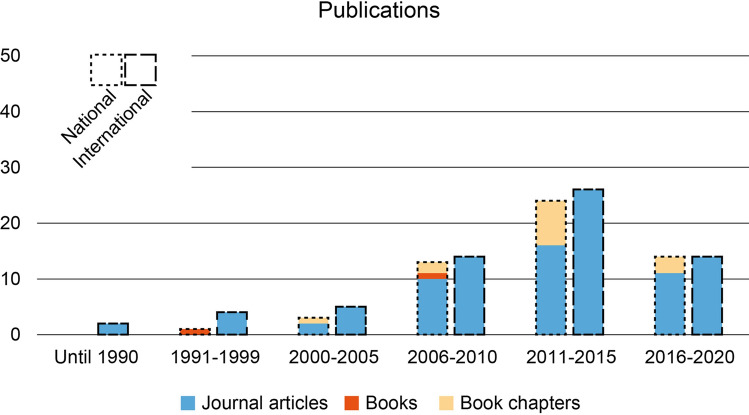

Our sample includes 120 publications that satisfied the eligibility criteria, of which 65 (54.2%) were peer-reviewed and published in internationally indexed journals (Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus), and 55 in national outlets (45.8%), including 39 peer-reviewed journal articles (not included in the Web of Science Core Collection, Journal Citation Reports, or Scopus), two books, and 14 book chapters (Fig. 1 and ESM S2). Hence, the international outlets are exclusively peer-reviewed and indexed journals, while most of the national publications are from peer-reviewed journals that lack international indexing, but include books and book chapters. Thus, almost half of the research in our evidence base was published in outlets that are not internationally indexed. With regards to language, 62 (51.7%) of the studies were published in Spanish, the remaining 58 (48.3%) in English. Interestingly, a considerable portion (20.0%) of international research has been published in Spanish. In contrast, few national publications were written in English (10.9%).

Fig. 1.

Number of international and national publications on participatory management of Biosphere Reserves in Mexico (1981–2020)

Though some scholars in the 1980s addressed issues related to participation (see Halffter 1981), few analyses of this kind appeared before the 2000s. Our evidence base suggests a notable increase in publications after 2005 that peaked in 2011–2015 before decreasing after 2016 (Fig. 1). International publications addressed participation-related issues earlier than national ones. However, national publications have increased continuously and equaled international publications after 2016.

As to the affiliation of the first author, it became clear that most of the publications in our sample were written by scholars at Mexican universities or research institutions. While it is hardly surprising that the national publications were authored almost exclusively by scholars affiliated with universities, institutions, or NGOs in Mexico (96.4%), international publications relied predominantly on scholars living and working in Mexico (53.8%) and, though to a much lesser extent, the staff of international NGOs based in Mexico (3.1%). The percentage of authors affiliated with North American and European universities and research institutions, however, was huge (43.1%).

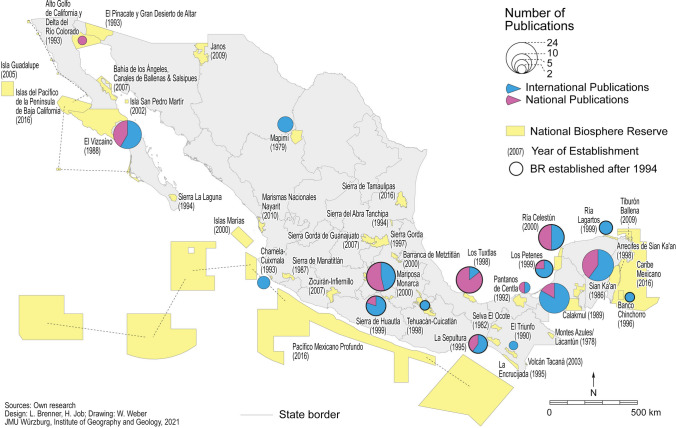

The case studies5 published in international and national outlets have been conducted in only a relatively small number of BRs; in fact, just 18 (41%) of Mexico’s 44 BRs (ESM S3). For this reason, most of the terrestrial BRs declared in the 1980s and early 1990s, as well as several large marine reserves (declared after 2015), still lack evidence-based information on the outcomes of public policies or management activities that strive to enhance stakeholder participation (Fig. 2 and ESM S3).

Fig. 2.

International and national publications based on case studies related to participation in Mexican Biosphere Reserves (1981–2020)

In addition, the research in our sample focuses on very few BRs, as 99 of the 117 case studies that refer to specific BRs (analyzed in 107 publications) were done in only nine (of 44) BRs, most of which are well-known in the scholarly community (ESM S3): Sian Ka’an, Los Tuxtlas, Mariposa Monarca, Montes Azules, Calakmul, El Vizcaíno, Ría Celestún, Sierra de Huautla, and La Sepultura. In sharp contrast, only 18 case studies have been carried out in other BRs (ESM S3). International publications differ fundamentally from national ones in geographic terms: research published internationally covers considerably more BRs than national publications. Research in five BRs (Mapimí, Ría Lagartos, Chamela-Cuixmala, El Triunfo, Banco Chinchorro) has been published in international journals only, while exclusively national research is limited to one BR (Alto Golfo de California & Delta del Río Colorado). International research was conducted primarily in BRs in southeastern Mexico (Montes Azules, La Sepultura, Los Tuxtlas, El Triunfo, Pantanos de Centla), especially on the Yucatán peninsula (Calakmul, Sian Ka’an, Ría Celestún, Los Petenes, Ría Lagartos, Banco Chinchorro). In contrast, case studies published in national outlets have been conducted in a considerably smaller number of BRs, particularly in Los Tuxtlas, Montes Azules, Mariposa Monarca, Sian Ka’an, Ría Celestún and El Vizcaíno. Another striking fact is that international publications focus on “older” BRs that were declared before the Seville World Congress (1995) (Fig. 1), whereas research on post-Seville BRs has been published almost equally in national and international outlets (Fig. 2 and ESM S3).

Regarding the research methods applied, our sample suggests that qualitative (66.7%, n = 120) and mixed methods (20.8%)—usually a combination of semi-structured expert interviews and questionnaires—were applied more often than exclusively quantitative methods (12.5%). Comparing international and national research, the former applied mixed methods more than the latter. National publications tended to apply either qualitative or quantitative methods.

With respect to theoretical approaches or paradigms, most of the research in our sample deals with topics related to issues of management and governance (36.6%), especially decision-making processes and their outcomes. Studies that analyze, specifically, citizen and stakeholder participation (31.2%) also appear frequently. The socioeconomic impacts of ecotourism form another important research topic (14.4%), while 12.1% of all publications applied a political ecology approach to BRs that highlighted actor constellations, power relations, and conflicts of interest. Less common focuses were socioeconomic factors that cause changes in land use (3.0%) and narrative accounts based on professional experiences (2.7%). International publications draw mainly on approaches related to environmental governance, stakeholder participation, and political ecology, while national ones focus on topics related to ecotourism.

Participation in decision-making and economic benefits

Both sets of publications in our evidence base focus on two key issues: a) participation of local resource users and communities in decision-making and management; and b) the generation and distribution of economic benefits (Table 1).

Regarding the implementation of participative management strategies and instruments in Mexican BRs, publications based on case studies in specific BRs (n = 107) and those that more generally assessed participation in Mexican BRs (n = 13) indicate both shortcomings and achievements. However, both corpora coincide in sustaining that negative policy outcomes prevail. As Table 1 illustrates, the objectives of effective stakeholder participation in management-related issues and the generation of socially balanced economic benefits have rarely been achieved. Various forms of exclusion from decision-making were observed in numerous cases highlighted, respectively, in international (e.g., Kaus 1993; Durand 2019) and national publications (e.g., Brenner and San Germán 2012). Only in comparatively few cases were efforts to strengthen participation in decision-making judged as “somewhat effective” (see for example, Martinez et al. 2016 [national] and Mayer et al. 2018 [international] ).

The research in our sample further suggests that many BRs generate few economic benefits and that these are often socially unbalanced, though they may provide some compensation for opportunity costs caused by legal restrictions and support for community development projects. Again, such shortcomings, observed in numerous cases—highlighted in both international (e.g., Ruiz Maillén et al. 2014) and national publications (e.g., Tejada-Cruz 2009)—frequently affect Mexican BRs (see Table 1). Nevertheless, there is some evidence of positive outcomes: in several cases (highlighted in both international and national publications), authors provided evidence that conservation-related economic activities such as ecotourism may generate considerable benefits that are (relatively) broadly distributed to local communities and other resource users (see for example, Piñar Álvarez et al. 2012 [national] and Manzo-Delgado et al. 2014 [international]).

The international and national publications in our evidence base also tend to coincide on the specific factors that impede participation in decision-making and the generation and distribution of economic benefits and, though to a lower degree, on the specific BRs that are most affected by these issues. We found notable overlap regarding the nature of the obstacles to participation identified in these studies and the geographic areas impacted by these inhibiting factors (Table 1). On the one hand, similar issues (such as external exclusion, see below) were identified by both international and national research in case studies conducted essentially in the same locales, such as Los Tuxtlas, Mariposa Monarca, Montes Azules, Sian Ka’an, Ría Celestún, Calakmul and Pantanos de Centla (e.g., Durand and Lazos 2008 [international], and Guzmán Chávez 2006 [national] for Los Tuxtlas). This finding could reveal overlap with respect to both the issues and the geographic areas involved. On the other hand, issues—some identical, others similar (e.g., resistance to restrictions due to perceived exclusion from economic benefits)—were identified in both bodies of research in our evidence base, but in case studies in different BRs. For example, Merino Pérez and Hernández Apolinar (2004, national publication) stressed resistance to restrictions in the case of the Mariposa Monarca BR, as did Durand et al. (2014, international) for the Montes Azules BR. Finally, several topics were identified exclusively by international or national research; that is, there was no overlap on issues or geographic areas.

With respect to the lack of stakeholder involvement in decision-making, both sets of literature highlight external and internal exclusion (or a combination) as key factors (Table 1). International research demonstrated external exclusion, defined as power structures and practices that push certain groups or individuals to the margins of debates or decision-making processes in several BRs, as shown in Table 1 (e.g., Trench 2008; Durand et al. 2014), whereas national publications provided similar evidence for the same and other BRs (e.g., Paré and Fuentes 2007). Interestingly, external exclusion has been detected congruently by international and national publications in several BRs. Issue-related overlaps also apply to the internal exclusion that occurs when groups and individuals are formally included in deliberative spaces but with only limited (or null) opportunities to intervene in meaningful decision-making due to the characteristics of the participatory platforms established (Durand et al. 2014). However, while internal exclusion was emphasized in both international (e.g., Alonso-Yañez et al. 2016) and national (e.g., Brenner and Vargas 2010) research, most case studies were conducted in different BRs. The combination of internal and external exclusion was identified mainly by international research (e.g., García-Frapolli et al. 2009; 2018), but only marginally in national publications (e.g., Tejeda-Cruz 2009).

With respect to exclusion from economic benefits and their impact, our evidence base shows the following patterns: low, socially biased income generated by ecotourism or other community-based activities was observed in both international (e.g., Ruíz Mallén et al. 2014) and national research (e.g., Díaz Carrión and Neger 2014) in several BRs. Moreover, negative impacts on livelihoods due to biased opportunity costs (generated by restrictions on access to resources or their use) that affect income and access to natural assets were observed by both international (Doyon and Sabinot 2014) and national (e.g., Legorreta-Díaz and Márquez-Rosano 2014) researchers as well, though in distinct BRs.

In contrast, evidence for the generation of, and participation in, economic benefits was detected less often in the international and national research in our evidence base. Hence, relatively few international (e.g., Lee 2014) or national (e.g., Piñar Álvarez et al. 2012) publications provide information regarding the equal distribution of income and employment (generated mainly by community-based ecotourism) among community members in virtually the same BRs. In a similar vein, only a few international (e.g., López-Medellín et al. 2017) and national (e.g., Isaac Márquez 2016) cases highlight benefits (income, employment) generated by government programs (including payments for ecosystem services) and support by NGOs. However, this research was conducted in different study areas (Table 1).

The literature analyzed shows similar patterns regarding conflicts generated by unsustainable resource use, for when local users respond to restrictions by performing practices of this kind conflicts with management authorities ensue. This situation was confirmed in both international (e.g., Hoffman 2014) and national (e.g., Morales Rodríguez et al. 2019) research, though in different BRs. One issue addressed exclusively in international research was the inefficiency, or biased effects, of payments for ecosystem services (e.g., De la Rosa-Velázquez et al. 2017) that ultimately fail to achieve the intended goals; in most cases, the conservation of forest cover in areas prone to deforestation (Table 1).

As mentioned above, our sample contains comparatively few case studies that provide evidence of effective stakeholder participation in management-related decision-making. Interestingly, positive outcomes were mentioned mostly in international publications (e.g., Brenner 2020). In contrast, national publications refer to only a few cases in one BR (Martínez et al. 2016). Examples of successful community-based economic activities based on local ownership and participation in business-related decision-making have been detected, but exclusively by national publications and only in a very few BRs (e.g., Diaz Carrión 2010).

Discussion

As we mentioned at the outset, we focused on five research questions. As to the first one, it became clear that there is no notable difference between both corpora of research. Negative assessments regarding participation in decision-making and economic benefits prevail in the case of both international and national publications included in our evidence base. If “equally managed” is synonymous with the absence of external and internal exclusion and the generation of considerable, socially non-biased economic benefits, both sets of research coincide in finding that most Mexican BRs fall short of achieving Aichi Target 11, at least in qualitative terms. The same goes for the goals of the Mexican Model. Though a few case studies (in both sources) highlight the effective, meaningful participation of local stakeholders on several advisory boards (e.g., Díaz Ávila et al. 2005; Bezaury-Creel and Gutiérrez-Carbonell 2009; Brenner 2019; 2020), in on-site management (e.g., Halffter 1981; Brenner and De la Vega-Leinert 2014), and in the economic benefits generated by ecotourism (e.g., Lee 2014; Mayer et al. 2018) or payments for ecosystem services (e.g., Manzo-Delgado et al. 2014; Cruz et al. 2017), the bulk of the publications underscore multiple types of shortcomings, especially external and internal exclusion (e.g., Smardon and Faust 2006; Brenner and San Germán 2012; Durand et al. 2014) and the lack of economic benefits generated by BRs (Esquivel Ríos et al. 2014; Ruíz-Mallén et al. 2014).

If the formally published scientific research in our evidence base mirrors “real” socio-environmental developments, then to date neither Aichi Target 11 nor the “Mexican Model” has been implemented in an entirely successful manner in Mexican BRs. Though we were not able to analyze “grey” literature (particularly the extensive work of practitioners) that might differ from more formal types of publications, this is nevertheless an issue of great concern considering the early establishment and rapid expansion of BRs that now cover all of Mexico’s biomes, and the clear focus on stakeholder participation within the scope of national environmental policies. Therefore, it is doubtful that Aichi Target 11 has been met in BRs in other lower income areas of the world that face even more obstacles than Mexico.

Addressing the second research question, it stands out that the international and national publications in our evidence base largely overlap regarding key factors and their implications that impede (or foster) stakeholder participation in decision-making and economic benefits. This overlap indicates the occurrence and relevance of specific policy- and management-related problems, which could deepen our knowledge of the obstacles to, and achievement of, Aichi Target 11 and the “Mexican Model”. To this effect, comparing the results of international and national research provides a reasonable level of certainty regarding the nature and consequences of specific challenges and issues related to BR management and the outcomes of public policies. The overlaps identified also point to the severity and recurrence of certain management- and policy-related challenges, such as the lack of economic benefits to compensate opportunity costs (e.g., Dickinson Castillo et al. 2014; Martínez-Reyes 2014). These overlaps serve as warning signals. Finally, the absence of overlaps may also provide useful insight into the wide variety of challenges and issues that exist. Contrasting international and national publications can help us identify issues that might be “overlooked” by focusing exclusively on international journals; for example, internal exclusion in the Mariposa Monarca (Brenner 2009; 2010), La Sepultura (Cruz Morales 2014), and Montes Azules BRs (Trench 2013) BRs.

Regarding the third research question, we noticed that the international research in our evidence base covers a considerably broader range of BRs, while national publications concentrate on comparatively few (Fig. 2). Hence, international papers provide a broader assessment in geographic terms. A possible explanation of this finding could be that scholars and postgraduate students at Mexican universities and research centers (who publish nationally) tend to conduct field research in BRs close to their place of residence. For example, the Mariposa Monarca BR is easily accessible from Mexico City and large, nearby cities like Toluca, Puebla, and Cuernavaca. Moreover, senior staff from foreign institutions generally have considerable funds at their disposal to cover travel expenses. Hence, the unequal availability of research funding might well explain the broader distribution of international research in spatial terms. The fact that research on BRs established before the Seville World Congress has been published primarily in international outlets and by foreign scholars (Fig. 2) might be related to the evolution of Mexican research institutions. Since the early 1990s, the number of universities, research centers, qualified academics, available funding, and publications outlets has increased continuously (see https://www.siicyt.gob.mx; retrieved 6 July 2021 from https://www.siicyt.gob.mx/index.php/estadisticas/), so national publications on management-related issues have increased slowly in quantitative terms, but still focus on a comparatively small number of BRs.

As to the fourth research question, it strikes that 95% of the national publications analyzed were authored by scholars who live and work in Mexico, with only a minimal percentage by practitioners usually working for major international and national NGOs. This result proves that the production of scholarly knowledge published in other than “visible” international journals is often overlooked, though it should be considered when assessing the shortcomings and achievements related to the outcomes of Aichi Targets, specifically, and the normative concept of BRs. Moreover, the large number and variety of national publications reveal familiarity with local contexts marked by frequent, close interaction with both resources and management authorities (some authors are members of advisory boards or serve as consultants) that can enhance our understanding of complex social interactions, including participation in BR management. There are reasons to believe that academics and practitioners living and working in Mexico not only add knowledge to research conducted by “visiting scholars” but may provide analyses that are deeper in many regards. The broad involvement of Mexican scholars also squares with UNESCO’s Lima Action Plan (2016), which demands that local actors, national academics, and publishing practitioners with considerable—yet often disregarded—knowledge support “their” BRs by “looking into them” constantly and closely. For instance, promotion of ecotourism might be supported by in-depth and case-specific research conducted by scholars living and working in Mexico.

Addressing the fifth research question, it stands out that the national publications in our sample frequently address issues (e.g., socioeconomic impacts of governmental policies at the Mariposa Monarca, Los Tuxtlas, and Montes Azules BRs) which are not—or only sketchily—addressed by international publications. Moreover, national publications tend to apply different theoretical-epistemological approaches that widen our analytical horizon when looking into management-related issues. Finally, if national publications are not considered, there is a large knowledge gap regarding many Mexican BRs, particularly in the case of those where no international research has been carried out, such as the Alto Golfo de California and Rìo de Colorado BRs.

With regard to the limitations of our review, using a fairly small number of keywords (titles, abstracts) during the search string might have missed some publications that employed other terms. Second, we excluded research published in languages other than English and Spanish. One source of possible biases in the review method utilized might be related to the screening and application of eligibility criteria by only two members of the research team. Moreover, coding as a qualitative and narrative synthesis method eliminates the possibility of applying statistical methods to validate results. In addition, the classification of study results involved generalizing results and findings of heterogeneous (in terms of methodology, theoretical approach, and publication date) case studies. We also acknowledge that including “grey” literature (such as theses and technical reports) would have broadened our analysis. Finally, it is possible that we missed some national publications (books and chapters) that are not recorded in the electronic libraries and databases searched.

Conclusion

Regarding the practical implications of our review of the Mexican case, several issues stand out. First, there is a consensus that Aichi Target 11—which stipulates that protected areas must be “equally managed”—has not been achieved in most Mexican BRs because considerable obstacles await solution. In particular, effective, legitimate, meaningful participation in decision-making remains a critical issue, despite notable efforts to foster stakeholder inclusion. Second, the genuine shared governance demanded by the Mexican Model and the Lima Action Plan have yet to become a reality in Mexico’s 44 BRs. Third, the same can be said for the equitable sharing of economic benefits generated, directly or indirectly, by conservation programs. Thus, it seems that the forward-looking vision of the “founding fathers” of the Mexican Model still awaits broad implementation.

The World Network of Biosphere Reserves “fosters the harmonious integration of people and nature for sustainable development through participatory dialogue; knowledge sharing; poverty reduction (…) thus contributing to the 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals” (retrieved 10, October, 2021 from https://en.unesco.org/biosphere/wnbr). In light of this statement by UNESCO, we recommend carefully reviewing and citing national publications together with high-ranking journal articles when doing future scientific research, despite the possible language barriers that may arise when analyzing participatory management issues in BRs. Specifically, we suggest taking a closer look at regional and local research focusing on UNESCO’s IberoMAB Network, especially in those Latin American countries that have established numerous BRs, such as Argentina, Chile, and Ecuador. Finally, fostering cooperation and knowledge transfer between management authorities and national-based scholars who conduct research in BRs might be fruitful, as the latter are more familiar with the local and regional environments than their foreign counterparts. This approach could enhance management efficiency and legitimacy not only in Mexico but also in other countries of the Global South.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Winfried Weber for the design and elaboration of maps.

Biographies

Ludger Brenner

is a Professor at the Universidad Autómoma Metropolitana (Department of Sociology) in Mexico-City/Mexico. His research interests include management of protected areas and tourism geography.

Hubert Job

is a Professor at the Julius-Maximilians-University (Institute of Geography and Geology) in Würzburg/Germany. His research interests include economic impacts of protected areas and ecotourism.

Footnotes

BRs are a legally established category of PAs in Mexico. However, they are not considered PAs by the IUCN, but could be “Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures” (OECMs), though they might overlap with traditional PAs, with core zones frequently declared as National Parks. Regardless of these divergent classifications, integration into the surrounding landscape and man-made environments (highlighted by Aichi Goal 11) is a key objective of BRs (Job et al. 2017).

BRs now comprise 62,952,750 hectares (including ocean surface), equivalent to 69.3% of the overall area protected by federal law. Of the 44 BRs declared by Mexican legislation, 41 are officially recognized by UNESCO and form part of the World Network of BRs (the three remaining BRs were declared recently, so UNESCO approval is pending). As to achieving the Aichi Targets, 10.9% of the national terrestrial and 22.3% of the marine territory have been declared federal protected areas (http://sig.conanp.gob.mx/website/pagsig/listanp/, retrieved 07/08/2020).

In addition, the following strings were used (in English and Spanish): Protected AND Area(s) AND Mexico; Environmental AND Protection AND México; as well as Conservation AND Mexico. However, they turned out to be largely ineffective, as very few relevant publications were found.

Qualitative methods generally refer to semi-structured expert/stakeholder interviews, coding, and content analysis supported by commercial software. Quantitative methods mostly comprise interviews using structured questionnaire and computer-assisted statistical analysis.

Of the 120 publications that met the eligibility criteria, 107 contain case studies carried out in a total of 117 specific BRs (see Fig. 1 and ESM S3). In addition, we found 14 publications with regional or national assessments based on empirical studies that did not refer to any specific BRs All 120 publications were coded and analyzed to support the findings reported in the Results section. Table 1 presents the 117 case studies carried out in specific BRs (analyzed in 107 publications).

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ludger Brenner, Email: bren@xanum.uam.mx.

Hubert Job, Email: hubert.job@uni-wuerzburg.de.

References

- Aalbers MB. Creative destruction through the Anglo-American hegemony: A non-Anglo-American view on publications, referees and language. Area. 2004;3:319–322. doi: 10.1111/j.0004-0894.2004.00229.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alatas SF. Academic dependency and the global division of labour in the social sciences. Current Sociology. 2003;51:599–613. doi: 10.1177/00113921030516003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Yanez G, Thumlert K, de Castell S. Re-mapping integrative conservation: (Dis)Coordinate participation in a Biosphere Reserve in Mexico. Conservation and Society. 2016;14:134–145. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.186335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altbach, P.G. 2013. Advancing the national and global knowledge economy: The role of research universities in developing countries. Studies in Higher Education 38: 316–330. 10.1080/03075079.2013.773222.

- Andrews JM. Shifts of strategies and focus of the conservation efforts of PRONATURA on the Yucatán Peninsula: A personal history. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2006;74:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2004.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baber Z. Provincial universalism: The landscape of knowledge production in an area of globalization. Current Sociology. 2003;51:615–623. doi: 10.1177/00113921030516004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bezaury-Creel, J.E. and D. Gutiérrez-Carbonell. 2009. Áreas naturales protegidas y desarrollo social en México. In Capital natural de México, vol. II: Estado de conservación y tendencias de cambio, ed. R. Dirzo, 385–43. Mexico-City: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO).

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G., N. Dudley, T. Jaeger, B. Lassen, N. Pathak Broome, A. Phillips and T. Sandwith. 2013. Governance of Protected Areas: From understanding to action. Gland: Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series 20.

- Brenner L. Aceptación de políticas de conservación ambiental: El caso de la Reserva de la Biosfera Mariposa Monarca. Economía, Sociedad y Territorio. 2009;9:259–295. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner L. Gobernanza ambiental, actores sociales y conflictos en las Áreas Naturales Protegidas de México. Revista Mexicana De Sociología. 2010;72:283–310. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner L. Multi-stakeholder platforms and protected area management: Evidence from El Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Conservation & Society. 2019;17:147–160. doi: 10.4103/cs.cs_18_63. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner L. La gestión participativa de Áreas Naturales Protegidas en México. Revista Mexicana De Sociología. 2020;82:343–373. doi: 10.22201/iis.01882503p.2020.2.58147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner L, Job H. Actor-oriented management of protected areas and ecotourism in Mexico. Journal of Latin American Geography. 2006;5:7–27. doi: 10.1353/lag.2006.0019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner L, Vargas del Río D. Gobernabilidad y gobernanza ambiental en México: La experiencia de la Reserva de la Biosfera Sian Ka´an. Polis. 2010;6:115–152. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner L, San Germán S. Gobernanza local para el "ecoturismo" en la Reserva de la Biosfera Mariposa Monarca, Mexico. Alteridades. 2012;22:131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner L, Job H. Challenges to actor-oriented environmental governance: Examples from three Mexican Biosphere Reserves. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie. 2012;103:1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9663.2011.00671.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner L, De la Vega-Leinert AC. La gobernanza participativa de áreas naturales protegidas. El caso de la Reserva de la biosfera El Vizcaíno. Región y Sociedad. 2014;26:183–213. doi: 10.22198/rys.2014.59.a77. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carius F, Job H. Community involvement and tourism revenue sharing as contributing factors to the UN Sustainable Development Goals in Jozani-Chwaka Bay National Park and Biosphere Reserve, Zanzibar. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2019;27:826–846. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2018.1560457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). 2010. Convention on Biological Diversity. Retrieved 27 July, 2020, from https://www.cbd.int/nbsap/training/quick-guides/.

- Cruz, B., M. Gustavo and J. López García. 2017. Resiliencia de la reserva de la biosfera Mariposa Monarca. In Los sistemas socioecológicos y su resiliencia: Casos de estudio, ed. R. Calderón Contreras, 123–137. Mexico-City: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana/Editorial Gedisa.

- Cruz Morales J. Desafíos para construir la democracia ambiental en la Cuenca Alta del Río Tablón, Reserva de la Biosfera La Sepultura, México. In: Díaz CL, Rosano CM, Trench T, editors. Paradojas de las tierras en Chiapas. Mexico-City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo; 2014. pp. 21–60. [Google Scholar]

- De la Rosa-Velázquez MI, Espinoza-Tenorio A, Díaz-Perera MÁ-, Ortega-Argueta A, Ramos-Reyes R, Espejel I. Development stressors are stronger than protected areas management: A case of the Pantanos de Centla Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Land Use Policy. 2017;67:340–351. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Ávila M, Jhon Mendoza LH, Locht Peitzner M, López Azuz N, Padrón Gil F, Rosas Hernández MI, von Bertrab Tamm A. Diagnóstico de los Consejos Asesores de 47 Áreas Naturales Protegidas. Mexico-City: Iniciativa Mexicana de Aprendizaje para la Conservación; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Carrión, I.A. 2010. Ecoturismo comunitario y género en la Reserva de la Biosfera Los Tuxtlas (México). Pasos/Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural 8: 151–165.

- Díaz Carrión IA, Neger C. Ecotourism in the Reserva de la Biosfera de Los Tuxtlas (Veracruz, Mexico) Athens Journal of Tourism. 2014;1:191–202. doi: 10.30958/ajt.1-3-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson Castillo J, Pinkus Rendón M, Pinkus Rendón M, Ramón Mac C. Depredación y ecoturismo. Realidades de los prestadores de servicios en la Reserva de la Biosfera Ría Celestún. Yucatán. Península. 2014;10:145–161. doi: 10.1016/j.pnsla.2015.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon S, Sabinot C. A new "conservation space"? Protected areas, environmental economic activities and discourses in two Yucatán Biosphere Reserves in Mexico. Conservation & Society. 2014;12:133–146. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.138409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durand L. Power, identity and biodiversity conservation in the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve, Chiapas, Mexico. Journal of Political Ecology. 2019;26:19–37. doi: 10.2458/v26i1.23160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durand L, Lazos E. The local perception of tropical deforestation and its relation to conservation policies in Los Tuxtlas Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Human Ecology. 2008;36:383–394. doi: 10.1007/s10745-008-9172-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durand L, Vázquez LB. Biodiversity conservation discourses. A case study on scientists and government authorities in Sierra de Huautla Biosphere Reserve. Land Use Policy. 2011;28:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2010.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durand L, Figueroa F, Guzmán MG. La ecología política en México. ¿Dónde estamos y para dónde vamos? Estudios Sociales. 2011;19:282–307. [Google Scholar]

- Durand L, Figueroa F, Trench T. Inclusion and exclusion in participation strategies in the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve, Chiapas, Mexico. Conservation and Society. 2014;12:175–189. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.138420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ergin M, Alkan A. Academic neo-colonialism in writing practices: Geographic markers in three journals from Japan, Turkey and the US. Geoforum. 2019;104:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esquivel Ríos SG, Cruz Jiménez L, Villarreal Zizumbo, Cadena Inostroza C. Gobernanza para el turismo en espacios rurales. Reserva de la biosfera Mariposa Monarca. Revista Mexicana De Ciencias Agrícolas. 2014;9:1631–1643. doi: 10.29312/remexca.v0i9.1053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon P, Dubois G, Dudley N, Ervin J, Ferrier S, Gidda S, Mackinnon K, Richardson K, Schmidt M, Seyoum-Edjigu E, Shestakov AS. Editorial Essay: An update on progress towards Aichi Biodiversity Target 11. Parks. 2019;25:7–18. doi: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2019.PARKAS-25-2PG.en. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García-Frapolli E, Ramos-Fernández G, Galicia E, Serrano A. The complex reality of biodiversity conservation through Natural Protected Area policy: Three cases from the Yucatán Peninsula. Land Use Policy. 2009;26:715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García-Frapolli E, Ayala-Orozco B, Oliva M, Smith RJ. Different approaches towards the understanding of socioenvironmental conflicts in protected areas. Sustainability. 2018;10:2240. doi: 10.3390/su10072240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez J, López-Nieva P. Are international journals of human geography really international? Progress in Human Geography. 2001;25:35–69. doi: 10.1191/030913201666823316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán Chávez MG. Biodiversidad y conocimiento local: del discurso a la práctica basada en el territorio. Espiral: Estudios Sobre Estado y Sociedad. 2006;13:145–176. [Google Scholar]

- Haddaway NR, Bethel A, Dicks VL, Koricheva J, Macura B, Petrokofsky G, Pullin AS, Savilaakso S, Stewart GB. Eight problems with literature reviews and how to fix them. Nature Ecology and Evolution. 2020;4:1582–1589. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-01295-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halffter G. Local participation in conservation and development. Ambio. 1981;10:93–96. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-7956-7_8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halffter G. Reservas de la Biosfera: problemas y oportunidades en México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana. 2011;27:177–189. doi: 10.21829/azm.2011.271743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DM. Conch, cooperatives, and conflict: Conservation and resistance in the Banco Chinchorro Biosphere Reserve. Conservation & Society. 2014;12:120–132. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.138408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac Márquez R. Ecoturismo y desarrollo comunitario: El caso de "Valentín Natural" en el sureste de México. Turismo y Sociedad. 2016;18:117–135. doi: 10.18601/01207555.n18.07. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Job H, Becken S, Lane B. Protected Areas in a neoliberal world and the role of tourism in supporting conservation and sustainable development: An assessment of strategic planning, zoning, impact monitoring, and tourism management at natural World Heritage Sites. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2017;25:1697–1718. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2017.1377432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Job H, Engelbauer M, Engels B. Das Portfolio deutscher Biosphärenreservate im Lichte der Sustainable Development Goals. Raumforschung Und Raumordnung. 2019;77:57–79. doi: 10.2478/rara-2019-0005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaus A. Environmental perceptions and social relations in the Mapimi Biosphere Reserve. Conservation Biology. 1993;7:398–406. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1993.07020398.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Konno K, Munemitzu A, Koshida C, Katayama N, Osada N, Spake R, Amano T. Ignoring non-English-language studies may bias ecological meta-analyses. Ecology and Evolution. 2020;2020:6373–6384. doi: 10.1002/ece3.6368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratzer A. Biosphere Reserves research: a bibliometric analysis. Eco.mont. 2018;10:36–49. doi: 10.1553/eco.mont-10-2s36. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus F, Merlin C, Job H. Biosphere reserves and their contribution to sustainable development. A value-chain analysis in the Rhön Biosphere Reserve. Germany. Zeitschrift Für Wirtschaftsgeographie. 2014;58:164–180. doi: 10.1515/zfw.2014.0011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AE. Territorialization, conservation, and neoliberalism in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Conservation & Society. 2014;12:147–161. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.138413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Legorreta Díaz MC, Márquez Rosano C. Atrapados en el laberinto de la mendicidad Democracia y política ambiental en las reservas de la biosfera Montes Azules y Lacantún, Chiapas. In: Díaz L, Rosano MCM, Trench T, editors. Paradojas de las tierras protegidas en Chiapas. Mexico-City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo; 2014. pp. 173–213. [Google Scholar]

- López-Medellín X, Vázquez LB, Valenzuela-Galván D, Wehncke E, Maldonado-Almanza B, Durand-Smith L. Percepciones de los habitantes de la Reserva de la Biosfera Sierra de Huantla: Hacía el desarrollo de nuevas estrategias de manejo participativo. Interciencia. 2017;42:8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Manzo-Delgado L, López-Garcia J, Alcántara-Ayala I. Role of forest conservation in lessening land degradation in a temperate region: The Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Journal of Environmental Management. 2014;138:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez N, Espejel I, Martinez Valdés C. Evaluation of governance in an administration of protected areas on the peninsula of Baja California. Frontera Norte. 2016;55:103–129. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Reyes JE. Beyond nature appropriation: Towards post-development conservation in the Maya forest. Conservation & Society. 2014;12:162–174. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.138417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer ML, Brenner B, Schauss C, Stadler J. Arnegger, Job H. The nexus between governance and economic impact of whale watching. The case of the coastal lagoons in the El Vizcaíno Reserve, Baja California; Mexico. Ocean & Coastal Management. 2018;162:46–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2018.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meriläinen S, Tienari J, Thomas R, Davies A. Hegemonic academic practices: Experiences of publishing from the periphery. Organization. 2008;15:584–597. doi: 10.1177/1350508408091008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merino Pérez L, Hernández Apolinar M. Destrucción de instituciones comunitarias y deterioro de los bosques en la Reserva de la Biosfera Mariposa Monarca. Revista Mexicana De Sociología. 2004;66:261–309. doi: 10.2307/3541458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morales Rodríguez JR, Ortega Argueta A, Ramos Muñoz DE, Gurri García FD. La capacidad de adaptación en la Reserva de la Biosfera Pantanos de Centla. Economía, Sociedad y Territorio. 2019;59:1119–1153. doi: 10.22136/est20191255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M. Worlding geography. From linguistic privileges to decolonial anywheres. Progress in Human Geography. 2021 doi: 10.1177/0309132520979356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M, Job H. Governance und Regionalentwicklung in Großschutzgebieten der Schweiz und Österreichs. Raumforschung Und Raumordnung. 2016;74:569–583. doi: 10.1007/s13147-016-0451-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Munn Z, Peters DJMDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2018;18:143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary BC, Kvista K, Bayliss HR, Derroire G, Healey JR, Hughes K, Kleinschroth F, Sciberrasc M, Woodcock P, Pullina AS. The reliability of evidence review methodology in environmental science and conservation. Environmental Science and Policy. 2016;64:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2016.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paré L, Fuentes T. Gobernanza ambiental y políticas públicas en Áreas Naturales Protegidas: Lecciones desde Los Tuxtlas. Mexico-City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods. 2014;5:371–385. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñar Álvarez Á, García Segura MD, García Campos H. Ecoturismo y educación ambiental para la sustentabilidad en la Reserva de la Biosfera de Los Tuxtlas. Revista De Investigación En Turismo y Desarrollo Local. 2012;5:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-García V, Ruiz-Mallen I, Porter-Bolland L, García-Frapolli E, Ellis EA, Mendez ME, Pritchard DJ, Sánchez-González MC. Local understandings of conservation in southeastern Mexico and their implications for community-based conservation as an alternative paradigm. Conservation Biology. 2013;27:856–865. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruíz-Mallén I, Newing H, Porter-Bolland L, Pritchard DJ, García-Frapolli E, López MEM, González MCS, De la Peña A, Reyes-García V. Cognisance, participation and protected areas in the Yucatán Peninsula. Environmental Conservation. 2014;41:265–275. doi: 10.1017/S0376892913000507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sada Guevara S. The Mexican Biosphere Reserves Landscape and sustainability. In: Reed MG, Price MF, editors. UNESCO Biosphere Reserves. Supporting biocultural diversity, sustainability and society. London: Earthscan; 2020. pp. 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta P. Open access publication: Academic colonialism or philanthropy? Geoforum. 2021;118:203–206. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simonian L. Defending the land of the jaguar. A history of conservation in Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Smardon R, Faust BB. Introduction: International policy in the biosphere reserves of Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2006;74:160–192. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2004.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tejeda-Cruz C. Conservación de la biodiversidad y comunidades locales: Conflictos en Áreas Naturales Protegidas de la Selva Lacandona, Chiapas, México. Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies. 2009;34:57–88. doi: 10.2307/41800468. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trench T. From "Orphans of the State" to Comunidad Conservacionista Institucional: The case of the Lacandón community, Chiapas. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power. 2008;15:607–634. doi: 10.1080/10702890802333827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trench, T. 2013. ¿Ganando terreno? La CONANP en la subregión Miramar de la Reserva de la Biosfera Montes Azules, Chiapas. In Paradojas de las tierras protegidas en Chiapas, eds. C. Legorreta Díaz, C. Márquez Rosano and T. Trench, 61–105. Mexico-City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo.

- United Nations Environment Program/World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC). 2020. World database on protected areas. Retrieved 27 July, 2020, from www.unep-wcme.org/resource-and-data/wdpahttps://www.cbd.int/article/2020-01-10-19-02-38.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 1996. Biosphere reserves: The Seville Strategy and the Statutory Framework of the World Network. Retrieved 10 August, 2020, from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0010/001038/103849eb.pdf.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 2008. Madrid Action Plan for Biosphere Reserves (2008–2013). Retrieved 10 August, 2020, from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0016/001633/163301e.pdf.

- Woodley S, Bhola N, Money C, Locke H. A review of evidence for area-based conservation targets for the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. Parks. 2019;25:31–46. doi: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2019.PARKS-25-2SW2.en. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.