Abstract

Introduction

The comparative efficacy of targeted systemic therapies for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) has not been systematically assessed using recent phase 3 data. This network meta-analysis assesses the comparative efficacy of targeted systemic therapies without the addition of topical corticosteroids (TCS) and/or topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) in adults with moderate to severe AD.

Methods

The systematic literature review searched through 17 May 2021 for phase 3/4 trials with upadacitinib, interleukin-4 (IL-4), interleukin-13 (IL-13), or JAK inhibitors compared with placebo or active intervention for adults and adolescents with moderate to severe AD with inadequate response to TCS/TCI or for whom TCS/TCI was medically inadvisable, without restrictions on year or region. Researchers assessed data using PRISMA guidelines. The proportion of patients achieving trial co-primary endpoints [Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1 (clear or almost clear) and reduction of ≥ 2 points from baseline; proportion of patients achieving Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) improvement ≥ 75% from baseline (EASI-75)]; EASI improvement ≥ 90% from baseline (EASI-90); and ≥ 4-point improvement on Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale from baseline (ΔNRS ≥ 4) were evaluated using Bayesian network meta-analysis.

Results

Of 3415 initially identified records, network meta-analysis (NMA) ultimately included 6 records representing 9 unique studies. Two upadacitinib trials were also included. Eleven clinical trials including 6254 patients were analyzed. Upadacitinib 30 mg daily was the most efficacious therapy across all endpoints at the primary endpoint (week 12 or 16) and at earlier timepoints, followed by upadacitinib 15 mg daily and abrocitinib 200 mg daily.

Discussion

Many factors need to be considered for treatment selection for AD. These findings can help healthcare providers when personalizing a patient’s treatment.

Conclusion

Upadacitinib 30 mg daily, upadacitinib 15 mg daily, and abrocitinib 200 mg daily may be the most efficacious targeted systemic therapies over 12–16 weeks of therapy in AD.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-022-00721-1.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, EASI, IGA, Network meta-analysis, Pruritus NRS, Systematic literature review

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| The comparative efficacy of targeted systemic therapies for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) has not been systematically assessed using recent phase 3 data. Network meta-analysis is a useful tool for clinicians, payers, and healthcare providers to inform decision-making about various therapies when treating patients with moderate to severe AD. |

| The study analyzed 11 clinical trials for IGA 0/1, EASI-75, EASI-90, and Pruritus NRS (≥ 4-point improvement) at the primary endpoint (week 12 or 16) and at earlier timepoints. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| The study found that upadacitinib 30 mg daily, upadacitinib 15 mg daily, and abrocitinib 200 mg daily may be the most efficacious targeted systemic therapies across 12–16 weeks of therapy. |

| This NMA suggests that some targeted systemic treatment options provide greater efficacy across key disease domains, such as skin and itch responses. These findings can help healthcare providers evaluate the overall efficacy benefit of these treatments when personalizing a patient’s treatment plan. Additionally, other factors, including safety, benefit–risk, and patient preferences, should be taken into account when personalizing a patient’s treatment plan. |

Introduction

Moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) is characterized by extensive eczematous lesions, along with persistent and severe itch, excoriation, skin pain, and discomfort [1–8], posing a significant burden for the affected patients, their families, and society [9, 10]. Targeted systemic therapies, including abrocitinib, baricitinib, dupilumab, tralokinumab, and upadacitinib, are new potential treatments for moderate to severe AD. While there are robust clinical trial programs for these therapies, including trials in combination with topical corticosteroids (TCS) and/or topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI), little is known about the comparative efficacy of these agents as monotherapy, i.e., without the addition of TCS and/or TCI. Additionally, there is a paucity of head-to-head monotherapy trials for these therapies [11]. Network meta-analysis (NMA) can provide indirect comparisons where head-to-head data are not available. This makes NMA a useful tool for clinicians, payers, and healthcare providers to inform decision-making about various therapies when treating patients with moderate to severe AD [12].

The objective of this study was to assess the comparative efficacy of targeted therapies as monotherapy for moderate to severe AD on the basis of a systematic literature review and NMA.

Methods

Data Source

A systematic literature review was conducted in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 2019 [13], the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Guide to the Methods of Technology Appraisal 2013 [14], and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care [15]. Databases examined are listed in the Supplementary Material. Two reviewers independently identified studies for inclusion at each stage of study selection. Discrepancies between inclusion/exclusion decisions were resolved by a third independent reviewer. Data from unpublished upadacitinib trials meeting search criteria were supplied by AbbVie. These trials have since been published [16]. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Selection Criteria

The systematic literature search was performed on records up to 17 May 2021 and was designed to identify all phase 3 or 4 randomized controlled trials evaluating targeted therapies in adults with moderate to severe AD who had an inadequate response to TCS or TCI treatment, or for whom topical treatments were medically inadvisable (Supplementary Material). The search identified publications for targeted therapies that are approved or could gain approval. Actual or potential licensed doses were included. Detailed in the Supplementary Material are the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram (Fig. S1), patient/population, intervention, comparison, outcomes, and study design criteria (Table S1), and quality and potential bias assessments of included trials (Table S2).

Outcomes

Efficacy outcomes included the proportion of patients achieving trial co-primary endpoints [Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1 (clear or almost clear) and reduction of ≥ 2 points from baseline; proportion of patients achieving Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) improvement ≥ 75% from baseline (EASI-75)], EASI improvement ≥ 90% from baseline (EASI-90), and ≥ 4-point improvement on Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale from baseline (ΔNRS ≥ 4) [17–19]. Different doses were considered independent treatment options. Outcomes were evaluated at the primary endpoint timepoint of each trial (week 12 for abrocitinib, week 16 for all other therapies), as well as at week 4 and week 8. Additionally, ΔNRS ≥ 4 and EASI-75 were compared at week 2, the earliest timepoint for which most treatments reported these outcomes. Values for earlier timepoints that were only available in figures were extracted using DigitizeIt software, version 2.5 [20].

Feasibility Assessment

NMA feasibility was assessed per Cope et al. [21]. Network connectivity of included trials was checked. Relevant study and baseline patient characteristics, including potential treatment effect modifiers (age, gender, duration of disease, EASI, IGA, itch), and mean placebo outcomes were compared to identify potential sources of cross-study heterogeneity [22–24].

Statistical Analysis

NMAs were conducted in a generalized linear model (GLM) framework using Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulations with four chains of 100,000 posterior iterations each. NMAs were run in JAGS (version 4.3.0) via R statistical software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; version 4.0.2) using the bnma package (version 1.4.0) [25–28]. Convergence was assessed with the Brooks–Gelman–Rubin method using potential scale reduction factor (PSRF). Fixed effects, random effects, and baseline risk-adjusted models were evaluated [28, 29], and NMA consistency assumptions were checked [29] to identify the best-fitting models. Placebo-unadjusted response rates, numbers needed to treat (NNT), odds ratios, and Surface Under the Cumulative RAnking curve (SUCRA) scores were estimated [29]. Statistical significance was determined by examining calculated odds ratio 95% credible intervals.

Results

Systematic Literature Review

Of 3415 unique records identified, 500 publications were assessed for eligibility and six records representing 9 unique studies were extracted [30–35]. Additionally, two upadacitinib trials (Measure Up 1, Measure Up 2) were included [16]. Studies included the following targeted therapy study arms: abrocitinib 100 mg daily, abrocitinib 200 mg daily, baricitinib 2 mg daily, baricitinib 4 mg daily, dupilumab 300 mg once every 2 weeks, tralokinumab 300 mg once every 2 weeks, upadacitinib 15 mg daily, and upadacitinib 30 mg daily.

For the network analysis of outcomes at the primary endpoint timepoint, 11 unique trials encompassing 6254 patients in 28 arms were included (Table 1). For the network analysis of EASI-75 at weeks 2, 4, and 8, and IGA 0/1 at week 4 and week 8, six records and two upadacitinib trials representing 11 unique trials were extracted, encompassing 6254 patients in 28 arms [32, 35–39]. Two of the studies were pooled [39]. For the network analysis of ΔNRS ≥ 4 at weeks 2, 4, and 8, nine unique trials of 4658 patients in 24 arms were analyzed [31–33, 36–39]. Two of the studies were pooled at week 8 [39]. Tralokinumab was excluded as a treatment option, given that no trials reported ΔNRS ≥ 4 at those timepoints. For the network analysis of EASI-90 at week 4 and week 8, ten unique trials encompassing 5961 patients in 26 arms were included [32, 35, 37–39]. Two of the studies were pooled [39].

Table 1.

Overview of studies for the network meta-analysis

| Study | Treatment | N | Age, years (mean ± SD) | Disease duration, years (mean ± SD) | Male (N, %) | Baseline EASI score (mean ± SD) | Baseline IGA score of 4 (N, %) | Baseline NRS score (mean ± SD) | Response rate observed in study at primary endpoint, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EASI-75 (%) | EASI-90 (%) | IGA 0/1 (%) | ΔNRS ≥4 (%) | |||||||||

| JADE MONO-1 | Abrocitinib 200 mg | 154 | 33.0 ± 17.4 | 22.7 ± 14.5 | 81 (53.0%) | 30.6 ± 14.1 | 63 (40.9%) | 7.1 ± 1.9 | 62.7 | 38.6 | 43.8 | 57.1 |

| Abrocitinib 100 mg | 156 | 32.6 ± 15.4 | 24.9 ± 16.1 | 90 (58.0%) | 31.3 ± 13.6 | 64 (41.0%) | 6.9 ± 2.0 | 39.7 | 18.6 | 23.7 | 37.4 | |

| Placebo | 77 | 31.5 ± 14.4 | 22.5 ± 14.4 | 49 (64.0%) | 28.7 ± 12.5 | 31 (40.3%) | 7.0 ± 1.8 | 11.8 | 5.3 | 7.9 | 14.9 | |

| JADE MONO-2 | Abrocitinib 200 mg | 155 | 33.5 ± 14.7 | 20.5 ± 14.8 | 88 (56.8%) | 29.0 ± 12.4 | 49 (31.6%) | 7.0 ± 1.6 | 61.0 | 37.7 | 38.1 | 55.3 |

| Abrocitinib 100 mg | 158 | 37.4 ± 15.8 | 21.1 ± 14.8 | 94 (59.5%) | 28.4 ± 11.2 | 51 (32.3%) | 7.1 ± 1.6 | 44.5 | 23.9 | 28.4 | 45.2 | |

| Placebo | 78 | 33.4 ± 13.8 | 21.7 ± 14.3 | 47 (60.3%) | 28.0 ± 10.2 | 26 (33.3%) | 6.7 ± 1.9 | 10.4 | 3.9 | 9.1 | 11.5 | |

| BREEZE-AD1 | Baricitinib 4 mg | 125 | 37.0 ± 12.9 | 25.0 ± 14.9 | 83 (66.4%) | 32.0 ± 12.7 | 51 (40.8%) | 6.5 ± 2.0 | 24.8 | 16.0 | 16.8 | 21.5 |

| Baricitinib 2 mg | 123 | 35.0 ± 13.7 | 25.0 ± 14.6 | 82 (66.7%) | 31.0 ± 11.7 | 52 (42.3%) | 6.4 ± 2.2 | 18.7 | 10.6 | 11.4 | 12.0 | |

| Placebo | 249 | 35.0 ± 12.6 | 26.0 ± 15.5 | 148 (59.4%) | 32.0 ± 13.0 | 105 (42.2%) | 6.7 ± 2.0 | 8.8 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 7.2 | |

| BREEZE-AD2 | Baricitinib 4 mg | 123 | 34.0 ± 14.1 | 23.0 ± 14.8 | 82 (66.7%) | 33.0 ± 12.7 | 63 (51.2%) | 6.6 ± 2.2 | 21.1 | 13.0 | 13.8 | 18.7 |

| Baricitinib 2 mg | 123 | 36.0 ± 13.2 | 24.0 ± 13.8 | 65 (52.9%) | 35.0 ± 16.0 | 62 (50.4%) | 6.6 ± 2.2 | 17.9 | 8.9 | 10.6 | 15.1 | |

| Placebo | 244 | 35.0 ± 13.0 | 25.0 ± 13.9 | 154 (63.1%) | 33.0 ± 12.8 | 121 (49.6%) | 6.8 ± 2.2 | 6.1 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 4.1 | |

| BREEZE-AD5 | Baricitinib 2 mg | 146 | 40.0 ± 15.0 | 24.0 ± 16.0 | 69 (47.3%) | 26.6 ± 11.0 | 61 (41.8%) | 7.3 ± 2.1 | 29.5 | 20.5 | 24.0 | 25.2 |

| Placebo | 147 | 39.0 ± 17.0 | 23.0 ± 17.0 | 80 (54.4%) | 27.0 ± 11.0 | 61 (41.5%) | 7.0 ± 2.4 | 8.2 | 3.4 | 5.4 | 5.7 | |

| SOLO 1 | Dupilumab 300 mg | 224 | 39.8 ± 14.7 | 28.5 ± 16.1 | 130 (58.0%) | 33.0 ± 13.6 | 108 (48.2%) | 7.2 ± 1.9 | 51.3 | 35.7 | 37.9 | 40.8 |

| Placebo | 224 | 39.5 ± 13.9 | 29.5 ± 14.5 | 118 (52.7%) | 34.5 ± 14.5 | 110 (49.1%) | 7.4 ± 1.8 | 14.7 | 7.6 | 10.3 | 12.3 | |

| SOLO 2 | Dupilumab 300 mg | 233 | 36.9 ± 14.0 | 27.2 ± 14.2 | 137 (58.8%) | 31.8 ± 13.1 | 115 (49.4%) | 7.6 ± 1.6 | 44.2 | 30.0 | 36.1 | 36.0 |

| Placebo | 236 | 37.4 ± 14.1 | 28.2 ± 14.4 | 132 (55.9%) | 33.6 ± 14.3 | 115 (48.7%) | 7.5 ± 1.9 | 11.9 | 7.2 | 8.5 | 9.5 | |

| ECZTRA 1 | Tralokinumab 300 mg | 603 | 38.6 ± 13.7 | 27.9 ± 14.5 | 351 (58.2%) | 32.2 ± 13.7 | 305 (50.6%) | 7.7 ± 1.4 | 25.0 | 14.5 | 15.8 | 20.0 |

| Placebo | 199 | 39.4 ± 15.2 | 29.6 ± 15.1 | 123 (61.8%) | 32.9 ± 13.9 | 102 (51.3%) | 7.7 ± 1.4 | 12.7 | 4.1 | 7.1 | 10.3 | |

| ECZTRA 2 | Tralokinumab 300 mg | 593 | 37.2 ± 14.7 | 28.3 ± 15.9 | 359 (60.5%) | 32.1 ± 14.3 | 286 (48.2%) | 7.9 ± 1.5 | 33.2 | 18.3 | 22.2 | 25.0 |

| Placebo | 201 | 35.1 ± 14.0 | 27.5 ± 14.7 | 114 (56.7%) | 32.6 ± 13.9 | 101 (50.3%) | 8.0 ± 1.4 | 11.4 | 5.5 | 10.9 | 9.5 | |

| Measure Up 1 | Upadacitinib 30 mg | 285 | 33.6 ± 15.8 | 20.4 ± 14.3 | 155 (54.4%) | 29.0 ± 11.1 | 125 (43.9%) | 7.3 ± 1.5 | 79.7 | 65.8 | 62.0 | 60.0 |

| Upadacitinib 15 mg | 281 | 34.1 ± 15.7 | 20.5 ± 15.9 | 157 (55.9%) | 30.6 ± 12.8 | 127 (45.2%) | 7.2 ± 1.6 | 69.6 | 53.1 | 48.1 | 52.2 | |

| Placebo | 281 | 34.4 ± 15.5 | 21.3 ± 15.3 | 144 (51.3%) | 28.8 ± 12.6 | 131 (46.6%) | 7.3 ± 1.7 | 16.3 | 8.1 | 8.4 | 11.8 | |

| Measure Up 2 | Upadacitinib 30 mg | 282 | 34.1 ± 16.0 | 20.8 ± 14.3 | 162 (57.5%) | 29.7 ± 12.2 | 156 (55.3%) | 7.3 ± 1.6 | 72.9 | 58.5 | 52.0 | 59.6 |

| Upadacitinib 15 mg | 276 | 33.3 ± 15.7 | 18.8 ± 13.3 | 155 (56.2%) | 28.6 ± 11.7 | 150 (54.4%) | 7.2 ± 1.6 | 60.1 | 42.4 | 38.8 | 41.9 | |

| Placebo | 278 | 33.4 ± 14.8 | 21.1 ± 13.6 | 154 (55.4%) | 29.1 ± 12.1 | 153 (55.0%) | 7.3 ± 1.6 | 13.3 | 5.4 | 4.7 | 9.1 | |

Abrocitinib 100 mg, abrocitinib 200 mg, baricitinib 2 mg, baricitinib 4 mg, upadacitinib 15 mg, and upadacitinib 30 mg are once-daily treatments. Dupilumab 300 mg and tralokinumab 300 mg are administered once every 2 weeks

EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, IGA Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis, N sample size, NRS Numerical Rating Scale, ΔNRS ≥ 4 Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale reduction of ≥ 4 points from baseline, SD standard deviation

Network Meta-Analysis

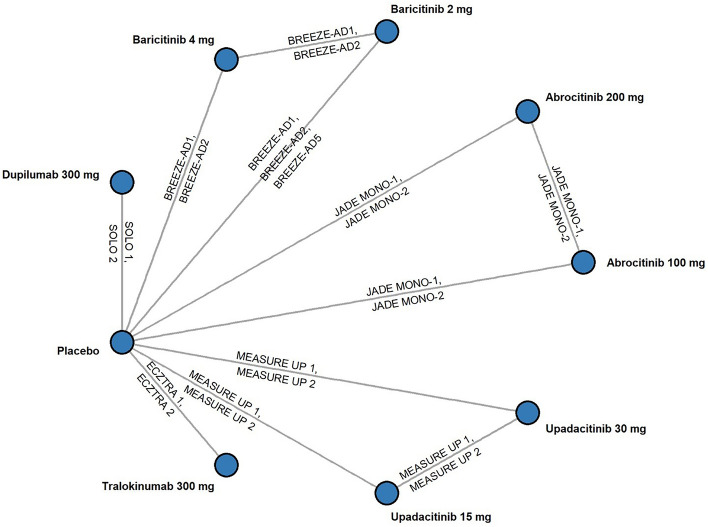

All trials were placebo controlled (Fig. 1) and generally comparable on the basis of enrollment inclusion and exclusion criteria and potential treatment effect modifiers (Table 1). Some differences were observed in placebo outcomes. Baseline risk-adjusted models were estimated to account for this heterogeneity but did not improve model fit in most cases. Model consistency checks and fit diagnostics supported fixed-effects models as the best-fitting parsimonious models for all efficacy outcomes evaluated except for ΔNRS ≥ 4 at week 2, EASI-75 at week 4, and IGA 0/1 at week 8, where the fixed-effects baseline risk-adjusted model had the best fit.

Fig. 1.

Network meta-analysis diagram. Network above is for primary endpoint analysis. The ΔNRS ≥ 4 network of the week 2 analysis is identical to the above except without ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2 (tralokinumab) as these trials did not report ΔNRS ≥ 4 at week 2. The EASI-75 network of the week 2 analysis is identical except with pooled SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 data as reported in Thaçi et al. [39]. EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, NRS Numerical Rating Scale, ΔNRS ≥ 4 Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale reduction of ≥ 4 points from baseline

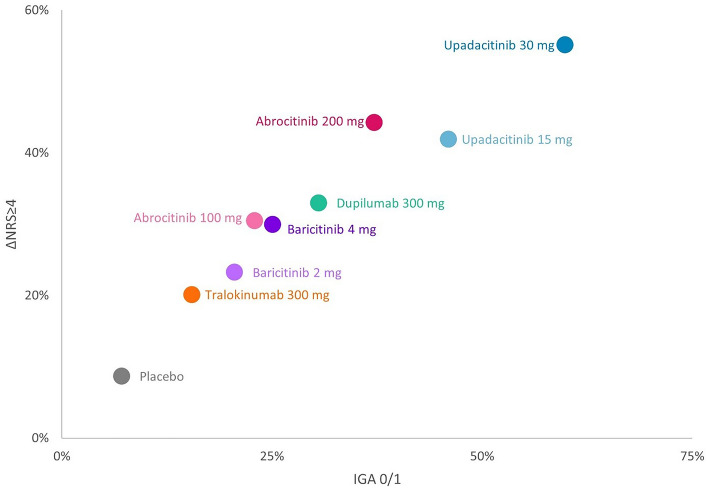

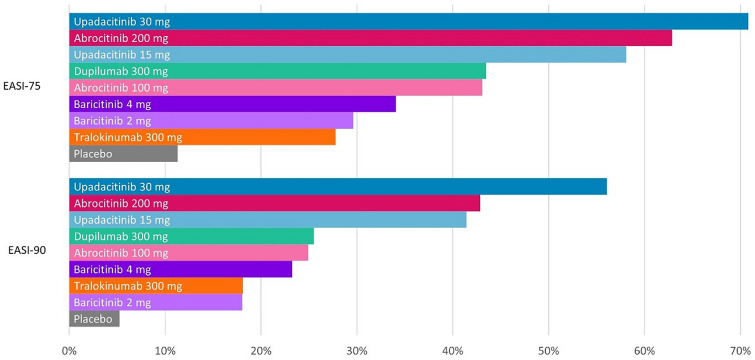

Results at the primary endpoint timepoint are presented in Table 2. The IGA 0/1 response rate was highest for upadacitinib 30 mg, followed by upadacitinib 15 mg, abrocitinib 200 mg, and dupilumab (Fig. 2). For ΔNRS ≥ 4, upadacitinib 30 mg also had the highest response rate, followed by abrocitinib 200 mg, upadacitinib 15 mg, and dupilumab. This rank order was also observed for EASI-75 and EASI-90 response rates (Fig. 3). Response rates for all efficacy outcomes at the primary endpoint are also shown in Fig. S2. Response rate rankings were the same as NNT and SUCRA score rankings. NNT and SUCRA score rankings for all efficacy outcomes at the primary endpoint are also shown in Figs. S3 and S5.

Table 2.

Odds ratios versus placebo, NNT, response rate, and SUCRA scores, at week 2 and primary endpoint timepoint (NMA fixed-effects results*)

| Outcome | Treatment | Na | Odds ratio versus placebo | NNT | Response rate | SUCRA (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoint timepoint | ||||||||

| EASI-75 | Abrocitinib 100 mg | 314 | 5.93 (3.49–10.72) | 3.2 (2.1–5.9) | 43.0% (24.8–64.0%) | 53.9 | ||

| Abrocitinib 200 mg | 309 | 13.27 (7.80–24.05) | 2.0 (1.6–2.9) | 62.9% (42.5–79.9%) | 85.8 | |||

| Baricitinib 2 mg | 392 | 3.31 (2.27–4.87) | 5.5 (3.4–10.6) | 29.6% (16.8–46.8%) | 23.2 | |||

| Baricitinib 4 mg | 248 | 4.07 (2.64–6.31) | 4.4 (2.8–8.4) | 34.1% (19.4–52.6%) | 36.4 | |||

| Dupilumab 300 mg | 457 | 6.05 (4.38–8.44) | 3.1 (2.3–4.9) | 43.5% (27.4–61.0%) | 55.6 | |||

| Tralokinumab 300 mg | 1196 | 3.02 (2.19–4.24) | 6.1 (3.8–11.4) | 27.8% (15.9–43.9%) | 19.1 | |||

| Upadacitinib 15 mg | 557 | 10.89 (8.16–14.71) | 2.1 (1.8–2.9) | 58.1% (40.9–73.5%) | 77.9 | |||

| Upadacitinib 30 mg | 567 | 19.08 (14.14–26.02) | 1.7 (1.5–2.1) | 70.8% (54.7–83.0%) | 98.3 | |||

| Placebo | 2214 | 11.3% (6.3–19.2%) | 0.0 | |||||

| EASI-90 | Abrocitinib 100 mg | 314 | 5.98 (2.84–14.92) | 5.1 (2.3–14.2) | 24.9% (10.7–50.6%) | 46.3 | ||

| Abrocitinib 200 mg | 309 | 13.49 (6.51–33.31) | 2.7 (1.6–5.6) | 42.8% (21.4–69.7%) | 82.5 | |||

| Baricitinib 2 mg | 392 | 3.98 (2.40–6.79) | 7.9 (3.9–19.0) | 18.0% (8.6–34.3%) | 23.8 | |||

| Baricitinib 4 mg | 248 | 5.50 (3.11–9.94) | 5.6 (2.9–13.0) | 23.2% (11.1–42.8%) | 44.0 | |||

| Dupilumab 300 mg | 457 | 6.20 (4.19–9.41) | 5.0 (2.9–9.6) | 25.5% (13.4–43.2%) | 50.2 | |||

| Tralokinumab 300 mg | 1196 | 3.99 (2.51–6.73) | 7.9 (3.9–18.2) | 18.1% (8.7–34.2%) | 25.0 | |||

| Upadacitinib 15 mg | 557 | 12.84 (8.93–18.85) | 2.8 (1.9–4.6) | 41.4% (24.5–60.8%) | 79.8 | |||

| Upadacitinib 30 mg | 567 | 23.17 (16.07–34.06) | 2.0 (1.5–2.9) | 56.1% (37.0–73.6%) | 98.4 | |||

| Placebo | 2214 | 5.2% (2.7–9.9%) | 0.0 | |||||

| IGA 0/1 | Abrocitinib 100 mg | 314 | 3.88 (2.14–7.58) | 6.4 (3.1–17.0) | 22.9% (10.7–43.3%) | 38.6 | ||

| Abrocitinib 200 mg | 309 | 7.71 (4.30–14.95) | 3.4 (2.0–6.8) | 37.2% (19.4–60.1%) | 73.3 | |||

| Baricitinib 2 mg | 392 | 3.39 (2.16–5.41) | 7.5 (3.9–17.3) | 20.6% (10.3–36.9%) | 30.6 | |||

| Baricitinib 4 mg | 248 | 4.38 (2.58–7.47) | 5.6 (3.0–12.8) | 25.0% (12.4–44.0%) | 46.3 | |||

| Dupilumab 300 mg | 457 | 5.75 (4.01–8.39) | 4.3 (2.7–7.8) | 30.5% (17.0–48.7%) | 60.3 | |||

| Tralokinumab 300 mg | 1196 | 2.39 (1.67–3.52) | 12.1 (6.0–29.1) | 15.5% (7.8–28.3%) | 15.7 | |||

| Upadacitinib 15 mg | 557 | 11.12 (7.77–16.40) | 2.6 (1.9–4.1) | 46.0% (28.3–64.8%) | 85.3 | |||

| Upadacitinib 30 mg | 567 | 19.47 (13.57–28.75) | 1.9 (1.5–2.7) | 59.8% (40.9–76.3%) | 99.9 | |||

| Placebo | 2214 | 7.1% (3.8–13.0%) | 0.0 | |||||

| ΔNRS ≥ 4 | Abrocitinib 100 mg | 314 | 4.59 (2.78–7.95) | 4.6 (2.6–10.0) | 30.5% (15.3–52.1%) | 47.0 | ||

| Abrocitinib 200 mg | 309 | 8.30 (5.03–14.38) | 2.8 (1.9–5.2) | 44.3% (24.6–66.3%) | 82.3 | |||

| Baricitinib 2 mg | 392 | 3.17 (2.03–5.04) | 7.0 (3.7–16.4) | 23.3% (11.4–41.7%) | 25.1 | |||

| Baricitinib 4 mg | 248 | 4.49 (2.71–7.50) | 4.7 (2.7–10.3) | 30.0% (15.1–51.0%) | 47.1 | |||

| Dupilumab 300 mg | 457 | 5.16 (3.63–7.44) | 4.1 (2.7–7.7) | 33.0% (18.0–52.6%) | 54.7 | |||

| Tralokinumab 300 mg | 1196 | 2.64 (1.86–3.84) | 8.9 (4.7–19.8) | 20.1% (10.1–36.3%) | 17.0 | |||

| Upadacitinib 15 mg | 557 | 7.56 (5.53–10.53) | 3.0 (2.2–5.0) | 41.9% (24.6–61.6%) | 77.7 | |||

| Upadacitinib 30 mg | 567 | 12.88 (9.42–17.94) | 2.2 (1.7–3.2) | 55.2% (35.7–73.2%) | 98.9 | |||

| Placebo | 2214 | 8.7% (4.4–16.5%) | 0.0 | |||||

| Week 2b | ||||||||

| EASI-75 | Abrocitinib 100 mg | 314 | 4.65 (1.76–16.36) | 10.6 (2.9–54.9) | 12.6% (3.9–38.8%) | 43.2 | ||

| Abrocitinib 200 mg | 309 | 13.02 (5.13–44.86) | 3.9 (1.7–11.8) | 28.9% (10.3–63.5%) | 79.6 | |||

| Baricitinib 2 mg | 392 | 4.32 (2.52–7.68) | 11.5 (4.8–32.3) | 11.8% (4.8–26.4%) | 39.4 | |||

| Baricitinib 4 mg | 248 | 7.37 (4.08–13.76) | 6.5 (3.0–16.7) | 18.5% (7.6–38.7%) | 61.1 | |||

| Dupilumab 300 mg | 457 | 3.54 (2.00–6.64) | 14.8 (5.6–46.8) | 9.8% (3.9–23.3%) | 33.0 | |||

| Tralokinumab 300 mg | 1196 | 1.78 (0.95–3.65) | 43.5 (−250.5 to 479.2) | 5.2% (1.9–13.9%) | 14.0 | |||

| Upadacitinib 15 mg | 557 | 15.18 (9.59–25.47) | 3.5 (2.0–7.2) | 31.9% (15.4–55.0%) | 81.6 | |||

| Upadacitinib 30 mg | 567 | 23.20 (14.72–38.84) | 2.6 (1.7–4.9) | 41.7% (21.9–65.1%) | 97.6 | |||

| Placebo | 2214 | 3.0% (1.3–6.5%) | 0.5 | |||||

| ΔNRS ≥ 4 | Abrocitinib 100 mg | 314 | 18.34 (13.47–25.30) | 5.0 (1.9–23.5) | 21.6% (4.5–61.5%) | 56.9 | ||

| Abrocitinib 200 mg | 309 | 44.43 (34.17–59.58) | 2.6 (1.4–9.9) | 40.0% (10.4–79.5%) | 87.8 | |||

| Baricitinib 2 mg | 392 | 5.85 (3.53–9.01) | 15.5 (3.7–89.1) | 8.0% (1.4–34.4%) | 18.2 | |||

| Baricitinib 4 mg | 248 | 9.15 (5.28–15.49) | 9.6 (2.6–53.1) | 12.0% (2.2–45.8%) | 39.5 | |||

| Dupilumab 300 mg | 457 | 7.18 (5.12–9.79) | 12.2 (3.2–65.2) | 9.7% (1.8–38.5%) | 28.4 | |||

| Tralokinumab 300 mgc | ||||||||

| Upadacitinib 15 mg | 557 | 30.09 (24.72–36.90) | 3.4 (1.6–14.2) | 31.1% (7.3–72.0%) | 71.5 | |||

| Upadacitinib 30 mg | 567 | 52.15 (43.52–63.29) | 2.4 (1.4–8.5) | 43.9% (12.1–81.7%) | 97.8 | |||

| Placebo | 1814 | 1.5% (0.3–7.8%) | 0.0 | |||||

The primary endpoint timepoint for each trial was week 12 for abrocitinib and week 16 for all other targeted therapies. Higher efficacy is indicated by higher values for response rate and lower values for NNT. SUCRA scores are based on the overall ranking of a treatment from the NMA, with higher SUCRA scores indicating a greater likelihood that a treatment is the top-ranked treatment in the network. Targeted therapy outcomes were reported at week 2 for all treatments except tralokinumab, which did not report ΔNRS ≥ 4 at week 2

ΔNRS ≥ 4 Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale reduction of ≥ 4 points from baseline, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, FEA fixed-effects baseline risk adjusted, IGA Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis, NNT Number needed to treat, SUCRA Surface Under the Cumulative RAnking curve

aN represents sample size of trial arms used in the NMA

bΔNRS ≥ 4 week 2 results use FEA model

cΔNRS ≥ 4 results not reported for tralokinumab 300 mg at week 2

Fig. 2.

IGA 0/1 versus ΔNRS ≥ 4 absolute response rate estimates for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (primary endpoint timepoint). ΔNRS ≥ 4 Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale reduction of ≥ 4 points from baseline, IGA Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis

Fig. 3.

EASI-75 and EASI-90 absolute response rate estimates for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (primary endpoint timepoint). EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index

The odds ratios of all targeted therapies were statistically more efficacious than placebo for each outcome assessed at the primary endpoint timepoint (Table 2) with statistical differences observed between some targeted therapies (Table S3). For IGA 0/1, upadacitinib 30 mg was statistically more efficacious than all other therapies. For EASI-75, EASI-90, and ΔNRS ≥ 4, upadacitinib 30 mg was statistically more efficacious than all other therapies except for abrocitinib 200 mg. For select outcomes, upadacitinib 15 mg was statistically more efficacious than abrocitinib 100 mg (IGA 0/1), baricitinib 2 mg (all outcomes), baricitinib 4 mg (IGA 0/1, EASI-75, EASI-90), dupilumab (IGA 0/1, EASI-75, EASI-90), and tralokinumab (all outcomes). Abrocitinib 200 mg was statistically more efficacious than abrocitinib 100 mg (all outcomes), baricitinib 2 mg (all outcomes), baricitinib 4 mg (EASI-75), dupilumab (EASI-75), and tralokinumab (all outcomes).

Results at week 2 are presented in Table 2. The EASI-75 response rate was highest for upadacitinib 30 mg, followed by upadacitinib 15 mg, abrocitinib 200 mg, and baricitinib 4 mg, whereas the ΔNRS ≥ 4 response rate was highest for upadacitinib 30 mg, followed by abrocitinib 200 mg, upadacitinib 15 mg, and abrocitinib 100 mg. Response rates and NNT for EASI-75 and ΔNRS ≥ 4 at week 2 are also shown in Fig. S4. The EASI-75 odds ratios indicate that all therapies except for tralokinumab were statistically more efficacious than placebo, with upadacitinib 30 mg statistically more efficacious than all other therapies except abrocitinib 200 mg (Table S4). The ΔNRS ≥ 4 odds ratios indicate that all targeted therapies analyzed were statistically more efficacious than placebo, with both upadacitinib 30 mg and abrocitinib 200 mg statistically more efficacious than all other remaining therapies (Table S4). Results at other early timepoints are available in the Supplementary Material (Fig. S7, Table S6-S7).

Discussion

NMA allows for the simultaneous comparison of interventions that were not directly compared in head-to-head randomized controlled trials [40]. It can be very useful in ranking interventions in order of their relative efficacy [41]. When performed correctly, NMA can be an essential tool for decision-makers in the healthcare field to draw conclusions from the cumulative scientific evidence [42].

Skin and itch response are very important clinical responses for patients. This NMA found that monotherapy with upadacitinib 30 mg daily had the highest efficacy at the primary endpoint evaluation, followed by abrocitinib 200 mg daily (second in EASI-75, EASI-90, ΔNRS ≥ 4, third in IGA 0/1) and upadacitinib 15 mg daily (second in IGA 0/1, third in the other outcomes). All targeted therapies were superior to placebo at the primary endpoint. At all earlier timepoints analyzed for EASI-75, EASI-90, and IGA 0/1 (weeks 2, 4, and 8 for EASI-75, weeks 4 and 8 for EASI-90 and IGA 0/1), upadacitinib 30 mg daily had the highest efficacy, followed by upadacitinib 15 mg daily and abrocitinib 200 mg daily. For ΔNRS ≥ 4, upadacitinib 30 mg daily had the highest efficacy at weeks 2, 4, and 8, followed by upadacitinib 15 mg daily (third at week 2, second at weeks 4 and 8), abrocitinib 200 mg daily (second at week 2, third at week 8), and baricitinib 4 mg daily (third at week 4).

Drucker et al. published an ongoing NMA of patients with moderate to severe AD [43, 44]. They included randomized controlled trials with potentially heterogeneous baseline patient severity and concomitant medication use but did not report the same outcomes as in our research. Siegels et al. published a meta-analysis comparing outcomes for 13 different treatments for moderate to severe AD, but did not perform an NMA, making comparison of targeted therapies more challenging [45]. Silverberg et al. published an NMA comparing systemic therapies in monotherapy and combination therapy for AD but did not include data after October 2019, and so excluded the phase 3 upadacitinib trial program [46]. This analysis focused only on targeted therapies studied as monotherapy and considered the primary endpoints used in clinical trials (IGA 0/1 and EASI-75) and itch, the hallmark symptom of AD. This analysis also provided novel examination of early treatment benefits. Our research was based on an NMA to make treatment comparisons more directly comparable and investigated models with baseline risk adjustment to account for placebo response heterogeneity.

When it comes to personalized treatment selection for AD, many factors need to be considered, including age, childbearing age, treatable traits, patient needs, concomitant therapies, and appropriate treatment targets [47, 48]. Some patients may also prefer to use monotherapy, or may prefer not to use topical treatments. Treatments that provide rapid and greater efficacy across multiple disease domains may better align with personalized treatment expectations and benefit more patients. This NMA suggests that some targeted systemic treatment options provide greater efficacy across key disease domains, such as skin and itch responses. These findings can help healthcare providers evaluate the overall efficacy benefit of these treatments when personalizing a patient’s treatment plan.

In addition to efficacy, the choice of therapy is based on safety and benefit–risk. Further analysis is needed to assess the relative safety of targeted systemic treatments for AD, their benefit–risk profiles, and how these relate to patient preferences. These areas of future research can better inform shared decision-making processes.

Limitations

If any of the assumptions of an NMA, including network connectivity, homogeneity, and transitivity or consistency, are violated, its conclusions may be invalid [49]. Additionally, NMAs are susceptible to the methodological quality of included studies, reporting biases, and choices of study eligibility criteria [50]. NMAs are not substitutes for multiple head-to-head randomized controlled trial comparisons. We tested the assumptions in this NMA, tried multiple modeling approaches to ascertain best fit, and reviewed the quality of the underlying trial data to mitigate these limitations. NMAs use aggregated statistics from studies and not individual data.

Specific limitations to this study include variability in the primary endpoint timepoint across trials (12 weeks for abrocitinib and 16 weeks for the other therapies). Additionally, we assessed efficacy at earlier timepoints and did not find evidence of differing treatment effects from those observed at the primary endpoint assessment.

There appears to be some heterogeneity in placebo response rates across trials, though baseline risk-adjusted models accounting for this heterogeneity did not provide a better fit for all outcomes assessed except for ΔNRS ≥ 4 at week 2, EASI-75 at week 4, and IGA 0/1 at week 8. There are other sources of heterogeneity in the analyzed trials, including prior corticosteroid exposure and inclusion of adolescent patients in some trials. This analysis also excluded trials of patients receiving TCS or TCIs in combination with targeted therapies for AD, which may mimic current real-world use of treatments. A substantial set of trial results assessing targeted therapies in this patient population are available. Future research will examine their relative efficacy.

There are some nuanced cross-trial differences in outcome methodologies. For example, all trials utilized a five-level IGA scale that included “clear” and “almost clear,” though the descriptions of each level were not identical across trials. Similarly, all trials evaluated patient-reported itch on an 11-point NRS, though the questionnaire text differed slightly across trials. Specific to the abrocitinib trials, EASI and IGA excluded the scalp, palms, and soles from the assessment [51]. Although the results presented here utilize efficacy rates based on nonresponder imputation, the upadacitinib trials also employed a multiple imputation process to account for missing data due to the COVID pandemic [52, 53].

This NMA is over a relatively short period of treatment, up to 16 weeks. Long-term trials for these therapies are underway. Of note, long-term trials may present methodological challenges for NMAs due to attrition and differences in design.

Finally, this NMA focused on select efficacy outcomes and did not evaluate overall symptom severity, quality of life, or safety outcomes. Safety information for the therapies should be studied carefully, with attention to the risk–benefit of each treatment option. Future research in this area is warranted to better understand the risk–benefit profile of these therapies.

Conclusion

In this NMA, looking at targeted systemic therapies for AD used as monotherapy, upadacitinib 30 mg daily appears to be the most efficacious targeted therapy, followed by abrocitinib 200 mg daily and upadacitinib 15 mg daily, after 12 or 16 weeks of therapy. Relative differences in efficacy were apparent as early as week 2 of treatment, indicating the potential for early response. While upadacitinib appears to be the most efficacious therapy, other factors, including safety, benefit–risk, and patient preferences, should be taken into account when personalizing a patient’s treatment plan.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

AbbVie Inc., funded this study and participated in the study design; study research; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; and writing, reviewing and approving of this publication. All authors had access to the data, and participated in the development, review, and approval, and in the decision to submit this publication. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship. AbbVie Inc., also provided funding for the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Marric Buessing, PhD, Medicus Economics LLC, Boston, MA, United States; this support was funded by AbbVie. Systematic literature review was provided by Kimberley Maxwell, Georghia Michael, Manpreet Sambi, Helen Baldwin, Fiona Robinson, Robin Marwick, Diana Petrina and Sabrina Smith; this support was funded by AbbVie.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

All named authors (Jonathan I. Silverberg, H. Chih-ho Hong, Jacob P. Thyssen, Brian M. Calimlim, Avani Joshi, Henrique D. Teixeira, Eric B. Collins, Marjorie M. Crowell, Scott J. Johnson and April W. Armstrong) contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Eric B. Collins, Marjorie M. Crowell, and Scott J. Johnson. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Eric B. Collins, Marjorie M. Crowell, Scott J. Johnson, and Brian M. Calimlim. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Prior Presentation

These data have been presented via poster at Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis in June of 2021, and at AMCP Nexus in October of 2021.

Disclosures

Jonathan I. Silverberg is an advisor, speaker, or consultant for AbbVie, Asana Biosciences, Dermavant, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Glenmark, Kiniksa, LEO Pharma, Lilly, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, Pfizer, Realm Pharma, and Regeneron-Sanofi. He is also a researcher for GlaxoSmithKline.

Chih-ho Hong is a researcher, consultant, and/or advisor for AbbVie, Amgen, Arcutis, Bausch Health, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Celgene, Dermira, Dermavant, DS Biopharma, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Lilly, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, and UCB.

Jacob P. Thyssen is an advisor, investigator, and speaker for Almirall, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Leo Pharma, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi-Genzyme.

Brian M. Calimlim, Avani Joshi, and Henrique D. Teixeira are full-time, salaried employees of AbbVie Inc. and own AbbVie stock or stock options.

Eric B. Collins, Marjorie M. Crowell and Scott J. Johnson are employees of Medicus Economics LLC, which was paid fees by AbbVie to conduct the research in the manuscript.

April W. Armstrong reported receiving grants and personal fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Leo Pharma, and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp; personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim/Parexel, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dermavant, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc, Merck, Modernizing Medicine, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer Inc, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi Genzyme, Science 37 Inc, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, and Valeant; and grants from Dermira, Janssen-Ortho Inc, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, and UCB Pharma outside the submitted work.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or as supplementary materials.

References

- 1.Sánchez-Pérez J, Daudén-Tello E, Mora AM, et al. Impact of atopic dermatitis on health-related quality of life in Spanish children and adults: the PSEDA study. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104(1):44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silverberg JI, Garg NK, Paller AS, et al. Sleep disturbances in adults with eczema are associated with impaired overall health: a US population-based study. J Invest Derm. 2015;135(1):56–66. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simpson EL, Bieber T, Eckert L, et al. Patient burden of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD): insights from a phase 2b clinical trial of dupilumab in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(3):491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drucker AM, Wang AR, Qureshi AA. Research gaps in quality of life and economic burden of atopic dermatitis: the National Eczema Association Burden of Disease Audit. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(8):873–874. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sibbald C, Drucker AM. Patient burden of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(3):303–316. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Von Kobyletzki LB, Thomas KS, Schmitt J, et al. What factors are important to patients when assessing treatment response: an international crosssectional survey. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97(1):86–90. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(1):116–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCollum AD, Paik A, Eichenfield LF. The safety and efficacy of tacrolimus ointment in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27(5):425–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansson SG, Bieber T, Dahl R, et al. Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization, October 2003. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(5):832–836. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.12.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Odhiambo JA, Williams HC, Clayton TO, et al. Global variations in prevalence of eczema symptoms in children from ISAAC Phase Three. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(6):1251–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ClinicalTrials.gov. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). January 2021. Identifier NCT03738397. A Study to Compare Safety and Efficacy of Upadacitinib to Dupilumab in Adult Participants With Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis (Heads Up). Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03738397?term=NCT03738397&draw=2&rank=1

- 12.Catalá-López F, Tobías A, Cameron C, et al. Network meta-analysis for comparing treatment effects of multiple interventions: an introduction. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34(11):1489–1496. doi: 10.1007/s00296-014-2994-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J et al. (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane; 2019. http://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- 14.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Guide to the methods of technology appraisal. Process and methods [PMG9]. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg9/chapter/foreword#. Published 2013. [PubMed]

- 15.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) Systematic reviews: guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York: CRD, University of York; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021;397(10290):2151–2168. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00588-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simpson E, Bissonnette R, Eichenfield LF, et al. The Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD): the development and reliability testing of a novel clinical outcome measurement instrument for the severity of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(3):839–846. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leshem YA, Hajar T, Simpson EL. What the Eczema Area and Severity Index score tells us about the severity of atopic dermatitis: an interpretability study. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(5):1353–1357. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yosipovitch G, Reaney M, Mastery V, et al. Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale: psychometric validation and responder definition for assessing itch in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(4):761–769. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bormann, DigitizeIt (version 2.5), 2001–2020. http://www.digitizeit.de/

- 21.Cope S, Zhang J, Saletan S, et al. A process for assessing the feasibility of a network meta-analysis: a case study of everolimus in combination with hormonal therapy versus chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer. BMC Med. 2014;12(1):93. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chou JS, LeBovidge J, Timmons K, et al. Predictors of clinical success in a multidisciplinary model of atopic dermatitis treatment. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32(5):377–383. doi: 10.2500/aap.2011.32.3462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bosma AL, Spuls PI, Garcia-Doval I, et al. TREatment of ATopic eczema (TREAT) Registry Taskforce: protocol for a European safety study of dupilumab and other systemic therapies in patients with atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(6):1423–1429. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bosma AL, de Wijs LE, Hof MH, et al. Long-term effectiveness and safety of treatment with dupilumab in patients with atopic dermatitis: results of the TREAT NL (TREatment of ATopic eczema, the Netherlands) registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(5):1375–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plummer M. JAGS: a program for analysis of Bayesian graphical models using Gibbs sampling. Available at : http://mcmc-jags.sourceforge.net/. Updated 14 Sep 2017.

- 26.R Core Team (2020) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/.

- 27.Seo M, Schmid C. Bnma: Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis using 'JAGS'. R package version 1.4.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=bnma.

- 28.Dias S, Welton NJ, Sutton AJ, et al. NICE DSU technical support document 2: a generalised linear modelling framework for pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Technical support document in evidence synthesis. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dias SA, Ades AE, Welton NJ, et al. Statistics in practice. 1. Hoboken: Wiley; 2018. Network meta-analysis for decision-making. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Thyssen JP, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(8):863–873. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simpson EL, Akinlade B, Ardeleanu M. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(11):1090–1091. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1700366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simpson EL, Lacour JP, Spelman L, et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis and inadequate response to topical corticosteroids: results from two randomized monotherapy phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(2):242–255. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simpson EL, Sinclair R, Forman S, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (JADE MONO-1): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10246):255–266. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30732-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simpson EL, Forman S, Silverberg JI, Zirwas M, Maverakis E, Han G, Guttman-Yassky E, Marnell D, Bissonnette R, Waibel J, Nunes FP, DeLozier AM, Angle R, Gamalo M, Holzwarth K, Goldblum O, Zhong J, Janes J, Papp K. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a randomized monotherapy phase 3 trial in the United States and Canada (BREEZE-AD5) J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(1):62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wollenberg A, Blauvelt A, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Tralokinumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from two 52-week, randomized, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase III trials (ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2) Br J Dermatol. 2020;180:437–449. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simpson E, Forman S, Silverberg J, et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trial (BREEZE-AD5) Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(4):3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 37.ClinicalTrials.gov. Study to evaluate efficacy and safety of PF-04965842 in subjects aged 12 years and older with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (JADE Mono-1). Identifier: NCT03349060. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT03349060. Updated 10 Dec 2019.

- 38.ClinicalTrials.gov. Study to evaluate efficacy and safety of PF-04965842 in subjects aged 12 years and older with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (JADE Mono-2). Identifier: NCT03575871. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03575871. Updated 21 Apr 2020.

- 39.Thaçi D, Simpson EL, Deleuran M, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab monotherapy in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 randomized trials (LIBERTY AD SOLO 1 and LIBERTY AD SOLO 2) J Dermatol Sci. 2019;94:266–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2019.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu G, Ades AE. Combination of direct and indirect evidence in mixed treatment comparisons. Stat Med. 2004;23(20):3105–3124. doi: 10.1002/sim.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watt J, Tricco AC, Straus S, et al. Research techniques made simple: network meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(1):4–12.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mills EJ, Thorlund K, Ioannidis JP. Demystifying trial networks and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;14:346. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drucker AM, Ellis A, Jabbar-Lopez Z, et al. Systemic immunomodulatory treatments for atopic dermatitis: protocol for a systematic review with network meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(8):e023061. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Drucker AM, Ellis AG, Bohdanowicz M, et al. Systemic immunomodulatory treatments for patients with atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(6):659–667. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siegels D, Heratizadeh A, Abraham S, et al. Systemic treatments in the management of atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2020;76:1053–1076. doi: 10.1111/all.14631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silverberg JI, Thyssen JP, Fahrbach K, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of systemic therapies used in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a systematic literature review and network meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:1797–1810. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thyssen JP, Thomsen SF. Treatment of atopic dermatitis with biologics and Janus kinase inhibitors. Lancet. 2021;397(10290):2126–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00717-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thyssen J, Vestergaard C, Deleuran M, et al. European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis (ETFAD): treatment targets and treatable traits in atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(12):e839–e842. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cipriani A, Higgins JP, Geddes JR, et al. Conceptual and technical challenges in network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(2):130–137. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-2-201307160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salanti G, Del Giovane C, Chaimani A, et al. Evaluating the quality of evidence from a network meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e99682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.A phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group, multi-center study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of PF-04965842 monotherapy in subjects aged 12 years and older, with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. Identifier NCT03575871. In: Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Thyssen JP, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(8):863–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.A phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study to evaluate upadacitinib in adolescent and adult subjects with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. Identifier NCT03569293. In: Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021 ;397(10290):2151–2168. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.A phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study to evaluate upadacitinib in adolescent and adult subjects with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. Identifier NCT03607422. In: Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021 Jun 5;397(10290):2151–2168. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or as supplementary materials.