SUMMARY

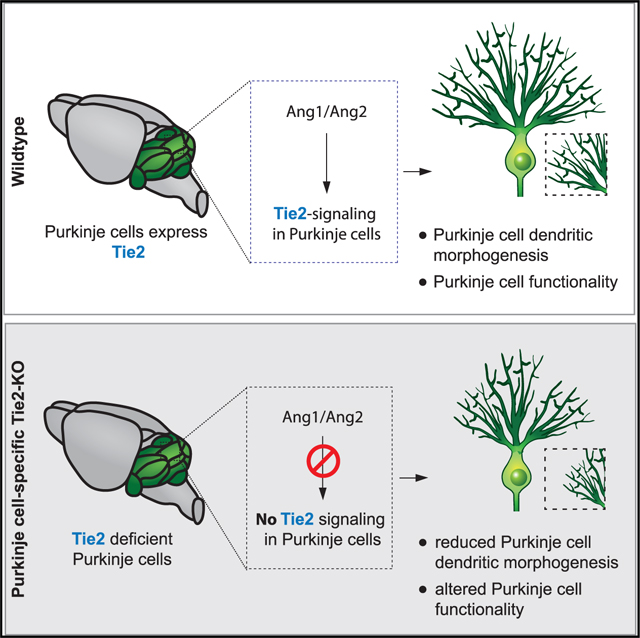

Neuro-vascular communication is essential to synchronize central nervous system development. Here, we identify angiopoietin/Tie2 as a neuro-vascular signaling axis involved in regulating dendritic morphogenesis of Purkinje cells (PCs). We show that in the developing cerebellum Tie2 expression is not restricted to blood vessels, but it is also present in PCs. Its ligands angiopoietin-1 (Ang1) and angiopoietin-2 (Ang2) are expressed in neural cells and endothelial cells (ECs), respectively. PC-specific deletion of Tie2 results in reduced dendritic arborization, which is recapitulated in neural-specific Ang1-knockout and Ang2 full-knockout mice. Mechanistically, RNA sequencing reveals that Tie2-deficient PCs present alterations in gene expression of multiple genes involved in cytoskeleton organization, dendritic formation, growth, and branching. Functionally, mice with deletion of Tie2 in PCs present alterations in PC network functionality. Altogether, our data propose Ang/Tie2 signaling as a mediator of intercellular communication between neural cells, ECs, and PCs, required for proper PC dendritic morphogenesis and function.

In brief

Luck et al. describe a mechanism regulating Purkinje cell dendritic morphogenesis. They show that Tie2 signaling acts in a cell-autonomous manner in Purkinje cells. The ligands, Ang1 and Ang2, are expressed in neural and endothelial cells, respectively. This pathway is required for proper dendritic morphogenesis and neuronal functionality.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Research of the last decade has shown that factors involved in the development of the nervous system are also required to regulate blood vessel growth and guidance, and vice versa. Furthermore, the intercellular communication between vascular and neural cells (neural progenitors, neurons, and glia) is crucial for the proper development and function of the central and peripheral nervous systems (Paredes et al., 2018; Segarra et al., 2019). However, the molecular determinants that both systems use to communicate are poorly understood. While most studies in this context have focused on characterizing particular aspects of this neurovascular crosstalk in the developing cortex, spinal cord, and retina (Paredes et al., 2018), the cerebellum, and how neurovascular mechanisms might regulate dendritic morphogenesis, has been largely unexplored.

Cerebellar function has been linked to sensory-motor processing (D’Angelo et al., 2011), as well as to the coordination of emotions (e.g., reward seeking and anxiety) and diverse aspects of cognition (e.g., spatial learning and navigation) (Adamaszek et al., 2017; Koziol et al., 2014; Wang and Zoghbi, 2001). In mice, the formation of the cerebellum starts during embryonic stages and continues postnatally (Butts et al., 2014). The mature cerebellum contains several types of excitatory and inhibitory neurons, organized in a three-layered structure: from outside to inside—the molecular layer (ML), the Purkinje cell layer (PCL), and the internal granular layer (IGL) (Butts et al., 2014). PCs represent the main GABAergic cell type, integrating motor, and sensory information derived from an array of parallel fibers and a single climbing fiber input. The PC soma is positioned in the PCL (a single cell layer), and its extensively branched dendritic tree expands into the ML. PC dendrites project in a planar fashion, oriented in parallel to the anterior-posterior axis of the brain (Leto et al., 2016). PC dendritic morphogenesis starts postnatally and proceed during a long period of time up to at least 3 months of age (McKay and Turner, 2005). It is regulated by cellular mechanisms involving dendritic growth, branching, dendritic self-avoidance, retraction processes, and maturation, which assures precise integration of inputs and propagation of signals (Takeo et al., 2015). Several signaling molecules have been described to regulate PC morphogenesis, among them Slit/Robo signaling (Gibson et al., 2014), Protocadherins (Ing-Esteves et al., 2018; Lefebvre et al., 2012; Toyoda et al., 2014), tropomyosin receptor kinase C (TrkC) (Huang et al., 2014; Joo et al., 2014), and thyroid hormone receptor a1 (TRa1) (Heuer and Mason, 2003), among others. Remarkably, at the same time as PCs are extending and positioning their dendritic trees, blood vessels are growing and branching in close vicinity. This also occurs within an environment of glia cells (Buffo and Rossi, 2013). If and how growing blood vessels, glia cells, and neurons communicate during cerebellum formation to assure proper PC dendritic morphogenesis remains unknown.

The angiopoietin-Tie signaling pathway is crucial for blood vessel formation, assembly, maturation, and homeostasis (Augustin et al., 2009). In ECs, Tie2 is the main protein tyrosine kinase receptor that is activated by angiopoietin ligands. Its activation is tightly regulated by the ratio of Ang1/Ang2 expression. While Ang1-induced signaling mediates EC survival and maturation, Ang2 can either counteract Ang1 or induce Tie2 activation in a context-dependent manner (Augustin et al., 2009). Tie2 activation is further regulated by the presence or absence of its co-receptor Tie1 (Hansen et al., 2010; Savant et al., 2015). Concerning CNS development, several studies (mainly in vitro) suggest a potential role of the angiopoietins in regulating neuronal progenitor proliferation, differentiation, migration, survival, and branching (Bai et al., 2009; Kosacka et al., 2005; Marteau et al., 2011; Rosa et al., 2010; Ward et al., 2005). However, the in vivo characterization of their effects on neurons is still missing. In addition, in vivo proof of whether the receptor Tie2 is expressed in certain neuronal types, and if the observed effects occur via direct signaling to Tie2 in neurons is lacking.

In this study, we describe a cell-autonomous role for Tie2 in PCs as a modifier of dendritic morphogenesis. Using in vivo mouse genetics for Ang1, Ang2, and Tie2, we identify the AngTie2 pathway as a neural-vascular-PC intercellular communication axis that regulates PC dendritic morphogenesis, with Tie2 acting in a PC cell-autonomous fashion. Unbiased analysis of the PC translatome indicates that the absence of Tie2 in PCs leads to deregulated expression of proteins involved in cytoskeleton dynamics and neurite branching. At the functional level, we show that Tie2-deficient PCs present altered network electrophysiological properties.

RESULTS

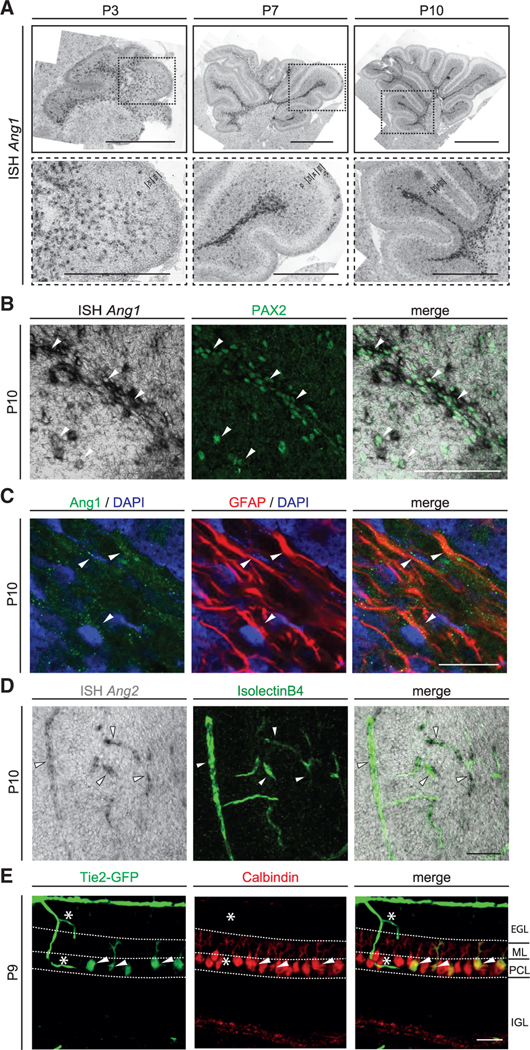

Ang1, Ang2, and Tie2 are expressed in different cell types during postnatal cerebellar development

We analyzed the temporal expression of angiopoietin ligands and their Tie2 receptor in the entire developing cerebellum. In the first postnatal week, Ang1 mRNA expression levels increased and peaked at P7. Subsequently, mRNA levels gradually diminished (Figure S1A). Consistently, in situ hybridization (ISH) showed that Ang1 mRNA was detected in the white matter (WM) of the cerebellum as well as in the IGL (Figure 1A). Ang1 mRNA expression declined in later stages (Figures S1A and S1B). To determine the cellular source of Ang1 we analyzed an available single cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) dataset of the developing murine cerebellum (Carter et al., 2018). In this dataset, Ang1 expression was found in the majority of GABAergic interneurons, in pial vessels and in a subpopulation of astrocytes (Figure S1C). To verify these results, we performed ISH combined with immunofluorescent (IF) staining on postnatal cerebellar tissue at different developmental stages (from P3 to P21). Consistent with the analysis of Ang1 expression using the scRNA-seq dataset, Ang1 mRNA colocalized with the GABAergic interneuron lineage marker Pax2 (Fleming et al., 2013; Maricich and Herrup, 1999; Figure 1B). Ang1 expression also colocalized with GFAP-expressing astrocytes located in the WM and the IGL (Figure 1C), which is consistent with previously published data (Baldwin et al., 2001).

Figure 1. Ang1, Ang2, and Tie2 are expressed by distinct cell types during development of the cerebellum.

(A) ISH of Ang1 mRNA in sections of cerebellum at different postnatal stages. Bottom images show insets of the respective top image. Scale bar, 1 mm (overview) and 500 μm (higher magnification).

(B) ISH of Ang1 mRNA on P10 cerebellar tissue together with IF staining of GABAergic interneuron lineage marker PAX2.

(C) IF staining of Ang1 on P10 cerebellar tissue together with astrocyte marker GFAP and DAPI.

(D) ISH of Ang2 mRNA on P10 cerebellar tissue combined with IsolectinB4 (EC marker).

(E) Representative image of cerebellar tissue of P9 Tie2-GFP mice stained for GFP and Calbindin (PC marker).

Double-positive cells are indicated with white arrowhead in (B)–(E). Asterisks shows GFP-positive blood vessels in (E). Scale bar in (B): 100 μm, (C): 20 μm and in (D) and (E): 50 μm. See also Figure S1.

The temporal course of Ang2 mRNA expression in the whole cerebellum was less dynamic (Figure S1D). Expression of Ang2 mRNA was found in ECs at all developmental stages analyzed, as previously described (Fiedler et al., 2006; Figure 1D).

Next, we analyzed the expression of the angiopoietin receptor Tie2 using a previously described Tie2-GFP reporter mouse line (De Palma et al., 2005). GFP expression was not just restricted to blood vessels of the postnatal cerebellum but was also observed in cerebellar PCs at P7 and P9 (Figure 1E; Figure S1E) and adult (Figure S1E). Of note, GFP signal was also detected in pyramidal neurons of the developing hippocampus (Figure S1F). Expression of Ang1 mRNA was also observed in the developing hippocampus (Figure S1G). To confirm the expression of Tie2 in PCs, we made use of the RiboTag mouse line, in which a modified ribosomal protein Rpl22 is tagged with an HA epitope and expressed in a Cre-dependent manner (Sanz et al., 2009). We crossed a PC-specific Cre driver line (Pcp2Cre; Barski et al., 2000) with RiboTag mice to assure specific expression in PCs (from here on Pcp2Cre:Rpl22HA/HA). The temporal expression of Cre recombinase in the driver line and its functionality was assessed by ISH of Cre mRNA as well as by using the ROSA-mTmG reporter line (from here on Pcp2Cre:mTmG) at different postnatal stages (Muzumdar et al., 2007). These approaches showed that Cre expression and activity started around P7 in a small number of PCs and that the majority of PCs expressed functional Cre recombinase by P21 (Figures S1H and S1I). Considering the temporal expression of Cre recombinase in PCs, we immunoprecipitated the HA-Rpl22 subunit together with its associated mRNA from cerebellar lysates of Pcp2Cre:Rpl22HA/HA animals at different time points starting from P10 and analyzed expression of Tie2 in the associated mRNA. Tie2 mRNA was detectable after ribosomal pull-down in all tested stages (Figure S1J). Finally, to verify that Tie2 mRNA was expressed in PCs, we crossed Pcp2Cre:Rpl22HA/HA mice with Tie2flox/flox animals (Savant et al., 2015) to generate triple-transgenic Pcp2Cre:Tie2flox/flox:Rpl22HA/HA mice, in which a reduction of Tie2 mRNA should be detected after HA-Rpl22 pull-down, when compared to Pcp2Cre:Rpl22HA/HA animals. Indeed, Tie2 mRNA expression was reduced in the triple-transgenic mice as early as P10 (Figure S1M), confirming the expression of Tie2 in PCs.

Taken together, the time points when Tie2 and its ligands Ang1 and Ang2 were expressed in the developing cerebellum coincided with the critical period of PC dendritic morphogenesis. This suggests that the angiopoietin-Tie2 signaling axis could be an intercellular communication mechanism via which neural cells, ECs, and PCs crosstalk to regulate PC development. As Tie2 is expressed in PCs during this developmental period, this also suggests that Tie2 might exert a cell-autonomous function in PCs.

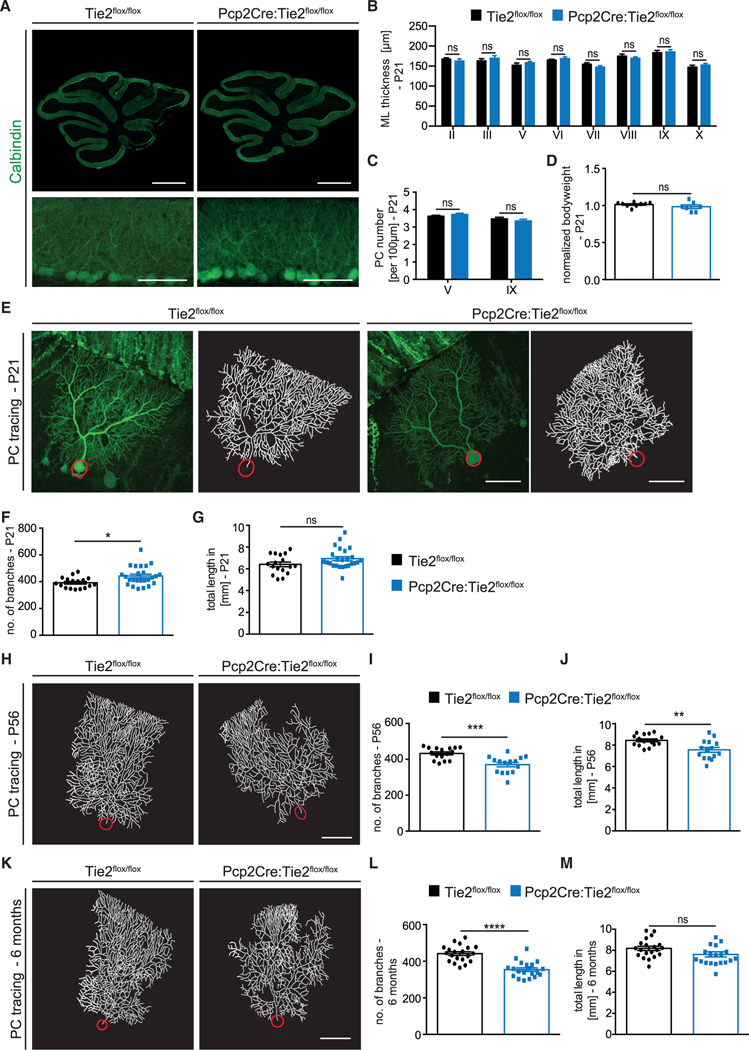

Tie2 expression in postnatal PCs regulates dendritic development and maintenance

The expression of Tie2 in PCs led us to investigate whether Tie2 regulated the dendritic development of these neurons in vivo, in a cell-autonomous manner. For this, we analyzed PC dendritic morphogenesis in Pcp2Cre+/−:Tie2flox/flox mice (in which Tie2 was specifically deleted in PCs; termed from hereon Pcp2Cre:Tie2flox/flox) and control littermates (Pcp2Cre−/−:Tie2flox/flox; termed from hereon Tie2flox/flox). Pcp2Cre:Tie2flox/flox animals showed no obvious differences in cerebellar anatomy, density of PC soma, or bodyweight when compared to control mice (Figures 2A–2D). PC dendritic branching was analyzed by stereotactic injection of low concentrations of AAV serotype 8 encoding YFP (AAV8-YFP, which has a tropism for PCs; Gibson et al., 2014) into the cerebellum of P7, P42, or 6-month-old mice, allowing us to reconstruct PC dendritic arbors at the single-cell level upon imaging (Figures S2A–S2C). Mice were sacrificed 2 weeks post-injection, and the number of PC dendritic branches as well as the total dendritic length were analyzed (see STAR Methods and Figure S2 for further details of the analysis). This revealed that Pcp2Cre:-Tie2flox/flox mice lost dendritic complexity over time. While initially the number of branches was slightly increased at P21 (Figures 2E–2G), PC dendritic complexity at later stages was characterized by a reduced number of both dendritic branches and total dendritic length (Figures 2H–2M). Notably, we also observed changes in the ordered array of the dendritic field (Figures 2E, 2H, and 2K). Interestingly, similar defects in dendritic morphogenesis were observed in heterozygous Pcp2Cre:Tie2+/flox animals (Figures S3A–S3C and S3G–S3I). Pcp2Cre+/− mice (from here on Pcp2Cre; Pcp2Cre−/− animals from here on referred to as WT) were analyzed as an additional control. These mice did not show any differences in cerebellar anatomy, the density of PC soma and bodyweight, or in PC dendritic morphology (Figures S4A–S4G), indicating that it is the absence of Tie2 in PCs that leads to the observed dendritic branching phenotype and not the expression of Cre recombinase.

Figure 2. PC-specific deletion of Tie2 leads to a progressive reduction in PC dendritic complexity.

(A) Representative images of P21 Tie2flox/flox and Pcp2Cre:Tie2flox/flox cerebella stained with Calbindin. Scale bar, 1 mm (top panels) and 100 μm (bottom panels).

(B) Bar graph showing ML thickness at P21 in all cerebella lobes (II-X).

(C) Bar graph showing PC number per 100 μm in lobes V and IX. Data in (B) and (C) are shown as mean ± SEM from minimum n = 7 animals per genotype.

(D) Bar graph showing normalized bodyweight of Tie2flox/flox and Pcp2Cre:Tie2flox/flox P21 mice. Data are shown as mean ± SEM from a minimum of n = 7 animals.

(E) Representative images of PCs from P21 Tie2flox/flox and Pcp2Cre:Tie2flox/flox mice labeled with YFP using AAV8 (left panels) and corresponding tracing (right panels).

(F and G) Quantitation of the number of branches (F) and total dendritic length (G) at P21.

(H) Representative image of traced PCs of Tie2flox/flox and Pcp2Cre:Tie2flox/flox mice at P56.

(I and J) Quantitation of the number of branches (I) and total dendritic length (J) at P56. K) Representative image of traced PCs of Tie2flox/flox and Pcp2Cre: Tie2flox/flox mice at 6 months.

(L and M) Quantitation of the number of branches (L) and total dendritic length (M) at 6 months.

Data in (E)–(M) are shown as mean ± SEM from a minimum of n = 15 neurons of a minimum of 3 independent animals. Unpaired Student’s t test; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001; ns = not significant. Scale bar in (E), (H), and (K), 50 μm. See also Figures S3, S4, and S6.

In summary, our analysis revealed that Tie2 in PCs contributes to the regulation of dendritic morphogenesis in a cell-autonomous manner. The fact that Pcp2Cre:Tie2flox/flox mice showed a slight increase in PC branching at P21, which is not maintained at later developmental stages, suggests that a compensatory mechanism might be active in early development, but this is not sufficient to compensate for the absence of Tie2.

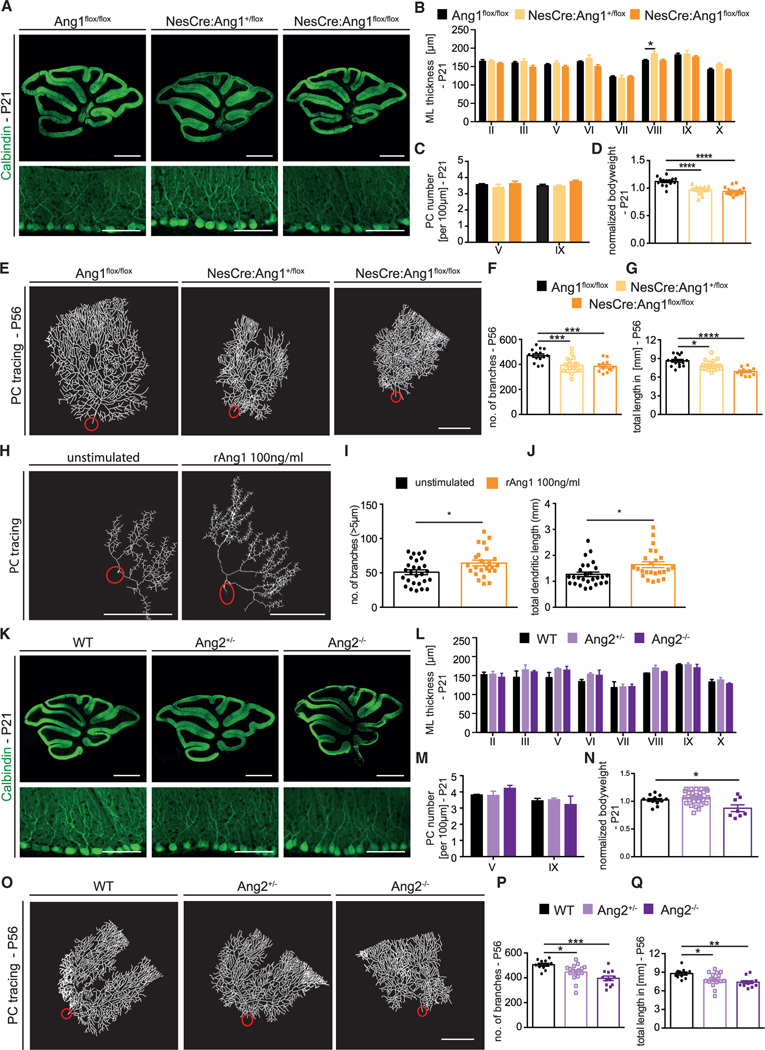

Nervous-system-specific deletion of Ang1 and constitutive Ang2 knockout lead to reduced PC dendritic complexity

Next, we asked whether changes in the expression of the Tie2 ligands Ang1 and Ang2 would also impair PC dendritic morphogenesis. To investigate the role of Ang1 in the developing cerebellum, we crossed Ang1flox/flox mice (provided by Susan E. Quaggin [Jeansson et al., 2011]) with the Nestin-Cre driver line (Tronche et al., 1999). Nestin-Cre recombines in all cells derived from Nestin-expressing neural progenitors (Wojcinski et al., 2017), including interneurons and astrocytes, where we detected Ang1 expression during cerebella development. Ang1 deletion was confirmed by ISH (Figure S5A) and qPCR (Figures S5B and S5D). Genetic inactivation of Ang1 expression did not affect Ang2 mRNA levels (Figures S5C and S5E). The overall anatomy of the cerebellum and the density of PC soma were unchanged in NesCre:Ang1+/flox and NesCre:Ang1flox/flox animals (Figures 3A– 3C), despite the fact that both genotypes showed a reduction in bodyweight at P21 compared to their Cre-negative littermates (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Mice with neural-specific deletion of Ang1 or Ang2 full knockout mice present aberrant PC dendritic morphogenesis.

(A) Representative images of P21 Ang1flox/flox, NesCre:Ang1+/flox, and NesCre:Ang1flox/flox stained with Calbindin (PC marker). Scale bar, 1 mm (top panels) and 100 μm (bottom panels).

(B) Bar graph showing ML thickness at P21 in all cerebella lobes (II–X).

(C) Bar graph showing PC number per 100 μm in lobes V and IX.

Data in (B) and (C) are shown as mean ± SEM from a minimum of n = 6 animals per genotype. Data are not significant if not indicated. One-way ANOVA for each lobe; *p < 0.05.

(D) Bar graph showing normalized bodyweight at P21 for the indicated mice. Data are represented as mean ± SEM from a minimum of n = 14 animals. One-way ANOVA; ****p < 0.0001.

(E) Representative image of traced PCs of Ang1flox/flox, NesCre:Ang1+/flox, and NesCre:Ang1flox/flox mice at P56.

(F and G) Quantitation of the number of branches and total dendritic length at P56. Data are represented as mean ± SEM from a minimum of n = 11 neurons from a minimum of 3 independent animals. One-way ANOVA; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001.

(H) Representative PC traces of PCs from organotypic cerebellar slices from P6 pups stimulated with or without 100 ng/mL rAng1 over the course of 3 DIV.

(I and J) Quantitation of the number of branches and total dendritic length of PCs from cerebellar slices. Data are represented as mean ± SEM from a minimum of n = 24 neurons from a minimum of 4 independent experiments. Unpaired Student’s t test; *p < 0.05.

(K) Representative images of P21 Ang2+/− and Ang2−/− cerebella sections stained with Calbindin. Scale bar, 1 mm and 100 μm in higher magnification.

(L) Bar graph showing ML thickness at P21 in all cerebella lobes (II–X).

(M) Bar graph showing PC number per 100 μm in lobes V and IX.

Data in (L) and (M) are represented as mean ± SEM from a minimum of n = 3 animals. Data are not significant if not indicated. One-way ANOVA for each lobe.

(N) Bar graph showing normalized bodyweight at P21 for the indicated mice. Data are represented as mean ± SEM from a minimum of n = 8 animals. Data are not significant if not indicated. One-way ANOVA; *p < 0.05.

(O) Representative traced PCs of WT, Ang2+/−, and Ang2−/− mice at P56.

(P and Q) Quantitation of the number of branches and total dendritic length of WT, Ang2+/−, and Ang2−/− mice at P56.

Data are represented as mean ± SEM from a minimum of n = 11 neurons from a minimum of 3 independent animals. One-way ANOVA; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Scale bars in (E), (H), and (O), 50 μm. See also Figures S5 and S6.

Using the same AAV8 approach, we then studied PC dendritic development in NesCre:Ang1+/flox and NesCre:Ang1flox/flox animals. PCs showed lower dendritic complexity already at P21, with a reduced number of dendritic branches in both genotypes, and reduced total dendritic length in NesCre:Ang1flox/flox animals, when compared to control littermates (Figures S5F–S5H). This phenotype was even more severe at P56 (Figures 3E–3G). Similarly, dendritic length of in vivo CA1 hippocampal neurons of NesCre:Ang1flox/flox pups (measured from Golgi staining) was also reduced compared to control mice (Figures S5I and S5J). These data suggested that Ang1-Tie2 signaling in Tie2-expressing neurons might be required to promote the development of dendritic branches. To test this hypothesis in PCs, we used an in vitro approach using cerebellar slice cultures. Cerebellar slices from P6 mice were cultured with or without recombinant Ang1 for 3 days in vitro (DIV). Analysis of PC dendrites showed that Ang1 stimulation resulted in a significant increase in both the number of branches and branch length (Figures 3H–3J). Taken together, these data show that Ang1 promoted dendritic growth and branching in CNS neurons. In vivo, neural loss of Ang1 led to a reduction in PC dendritic complexity, which recapitulated the phenotype observed in PC-specific Tie2 knockout mice. Based on the expression pattern of Ang1, our data suggest that direct binding of neural-derived Ang1 to Tie2 in PCs might induce a signaling cascade to regulate dendritic development.

We next studied whether Ang2 would also contribute to PC dendritic development using homo- and heterozygous Ang2 full knockout mice (from hereon Ang2+/− and Ang−/−) (Gale et al., 2002). Reduction of cerebellar Ang2 mRNA was confirmed in whole-tissue lysates of P21 mice (Figure S5K). Levels of Ang1 mRNA were unchanged in Ang2+/− and Ang2−/− animals (Figure S5L). The overall anatomy of the cerebellum, including the thickness of the ML as well as the density of PC somas, was unchanged (Figures 3K–3M). However, Ang2−/− mice had significantly reduced bodyweight at P21 compared to their WT littermates (Figure 3N). At P21, a significant reduction in the number of dendritic branches as well as the total dendritic length was observed in Ang2−/− animals but not in Ang2+/− mice (Figures S5M–S5O). At P56, both Ang2+/− and Ang2−/− animals showed a strong reduction of dendritic arborization (Figures 3O–3Q). Thus, Ang2 deficiency also resulted in reduced dendritic complexity of PCs. Altogether, the data suggested that the angiopoietin-Tie2 signaling axis contributed to the development and long-term maintenance of PC dendrites.

In PCs, dendritic self-avoidance (repulsion between branches of the same neuron) and acquisition of dendritic planarity are crucial steps to achieve proper morphology and functionality (Ing-Esteves et al., 2018; Lefebvre et al., 2012; Toyoda et al., 2014). This process can occur independently of dendritic branching (Gibson et al., 2014). We questioned whether, besides dendritic branching, the Ang-Tie2 signaling axis would also regulate dendritic self-avoidance and planarity. NesCre:Ang1flox/flox mice showed an increase in dendritic crosses at P21 that strongly inverted at P56 (Figures S6A and S6D). Concomitantly, PCs lost their dendritic planarity over time as indicated by an increased spread of branch endpoints as well as an increased planar width in the Z axis (Figures S6B, S6C, S6E, and S6F). In contrast to the NesCre:Ang1flox/flox animals, Ang2−/− mice showed a significant reduction in the number of dendritic crosses at P21, which normalized between genotypes in later stages (Figures S6G and S6J). Dendritic planarity was not affected in Ang2−/− mice (Figures S6H, S6I, S6K, and S6L). No differences were observed in Pcp2Cre:Tie2flox/flox and Pcp2Cre:-Tie2+/flox (Figures S6M–S6U and Figures S3D–S3F and S3J–S3L). Altogether, the data suggest either that Tie2 in PCs is only required to regulate dendritic branching but not self-avoidance or that a compensatory mechanism prevents a self-avoidance phenotype in the absence of Tie2 receptor (see also Discussion).

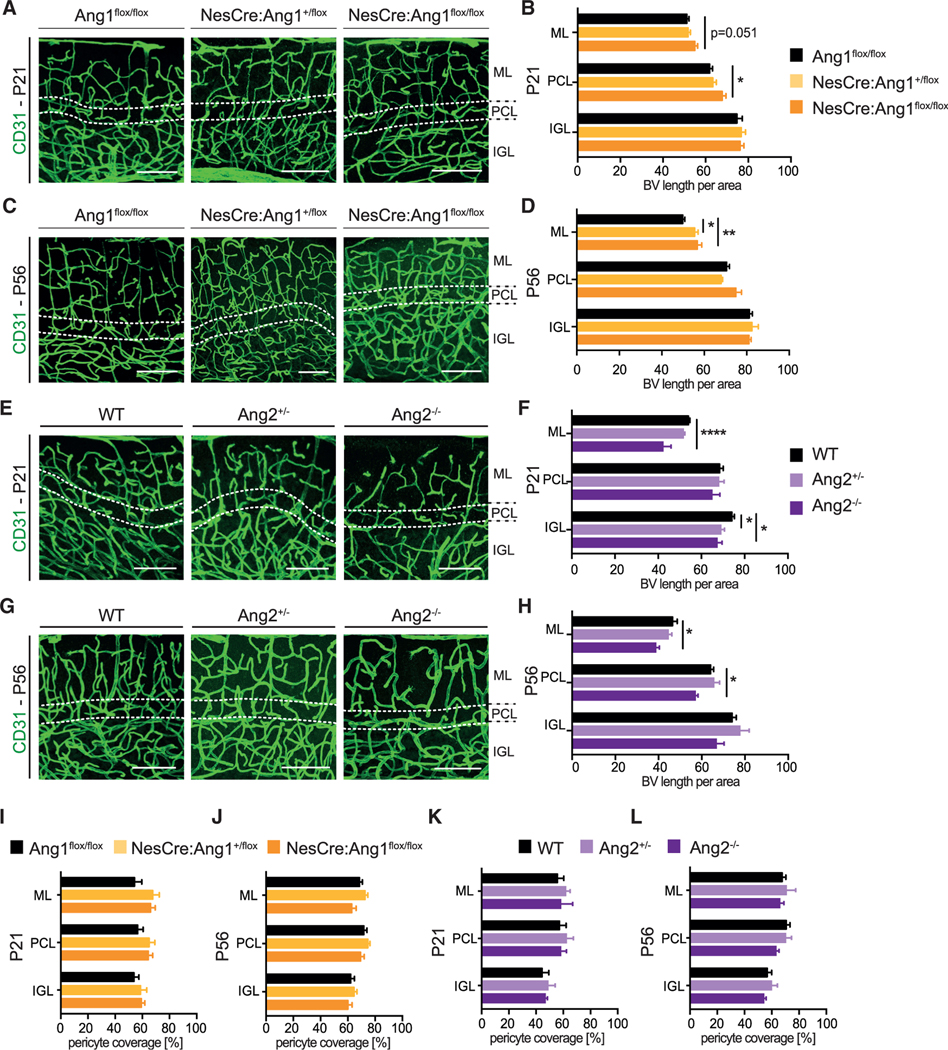

Cerebellar vasculature is mildly affected in NesCre:Ang1flox/flox and Ang2−/− mice

Our data so far indicate a cell-autonomous function of the angiopoietin-Tie2 signaling axis when studying Pcp2Cre:Tie2flox/flox mice. To further investigate whether changes in the vasculature could indirectly contribute to the observed PC branching phenotype, we analyzed the Ang1 and Ang2 transgenic mice. More specifically, we analyzed blood vessel development in the cerebellum of NesCre:Ang1+/flox and NesCre:Ang1flox/flox, as well as Ang2+/− and Ang2−/− animals. While heterozygous mice for both ligands (NesCre:Ang1+/flox and Ang2+/−) did not show any vascular defects, homozygous mice had a mild morphological phenotype (Figures 4A–4H). Consistent with Angiopoietin ligands function in the vascular system, NesCre:Ang1flox/flox animals presented a mild increase in blood vessel length at P21 and P56 in the outer layers of the cerebellum (Figures 4A–4D), whereas Ang2−/− mice showed a mild reduction in blood vessel length in the cerebellum (Figures 4E–4H). Pericyte coverage was not affected in the transgenic mouse lines at the different time points analyzed (Figures 4I–4L).

Figure 4. NesCre:Ang1flox/flox and Ang2−/− mice show mild vascular morphological defects in the cerebellum.

(A and C) Representative images of blood vessels (stained with the EC marker CD31) in the cerebellum from P21 and P56 from Ang1flox/flox, NesCre:Ang1+/flox and NesCre:Ang1flox/flox animals.

(B and D) Quantification of blood vessel length per area, for the different cerebellar layers. Data are represented as mean ± SEM from a minimum of n = 3 animals. Data are not significant if not indicated. One-way ANOVA; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

(E and G) Representative images of blood vessels (stained with the EC marker CD31) in the cerebellum from P21 and P56 from WT, Ang2+/−, and Ang2−/− mice.

(F and H) Quantification of blood vessel length per area for the different cerebellar layers. Data are represented as mean ± SEM from a minimum of n = 3 animals. Data are not significant if not indicated. One-way ANOVA; *p < 0.05; ****p < 0.001. Scale bar in (A), (C), (E), and (G): 100 μm.

(I–L) Pericyte coverage of blood vessels in the cerebellum was quantified in the different cerebellar layers at P21 (I and K) and P56 (J and L) for the indicated mice. Data are represented as mean ± SEM from a minimum of n = 3 animals. Data are not significant if not indicated. One-way ANOVA.

Taken together, neural loss of Ang1 and Ang2-deficiency mildly affected the patterning of cerebellar vascularization. The fact that (1) heterozygous mice showed PC dendritic branching defects but no vascular phenotype and (2) the PC-specific deletion of Tie2 also resulted in a PC dendritic arborization phenotype supports our hypothesis that angiopoietin-Tie2 signaling controlled PC dendritic branching in a cell-autonomous manner. However, the experiments could not completely rule out the possibility that the aberrant blood vessel patterning in homozygous knockout animals also contributed to the observed PC dendritic arborization defects.

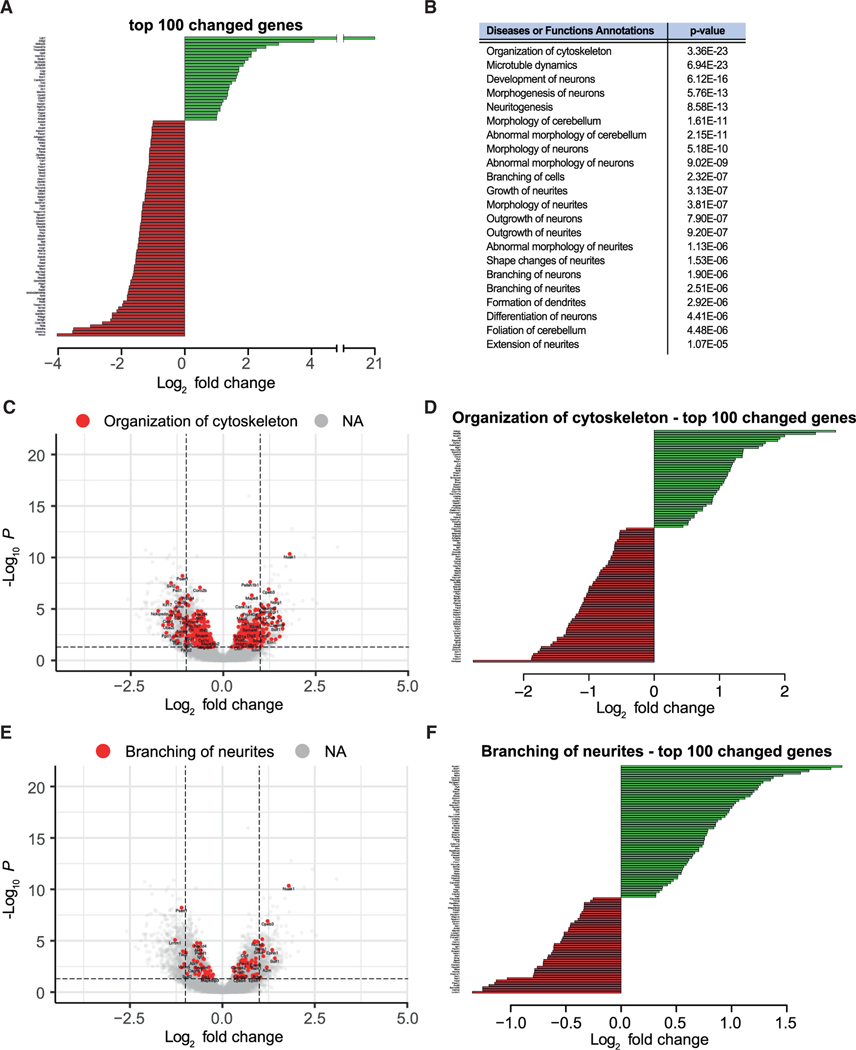

Tie2-deficient PCs present alterations in the expression of genes involved in neuronal wiring

We next aimed to investigate in further detail the molecular mechanisms behind the observed PC dendritic arborization phenotype. For this, we used the triple transgenic mouse line Pcp2Cre: Tie2flox/flox:Rpl22HA/HA to isolate and sequence mRNAs being translated specifically in PCs lacking Tie2 at P56. As control, we also isolated and sequenced mRNAs being translated in PCs from P56 Pcp2Cre:Rpl22HA/HA mice. Analysis of the sequencing data showed a total number of 4,147 differentially expressed genes, among them having 1,889 genes upregulated and 2,258 genes downregulated (Table S1; Figure 5A). These differentially expressed genes were characterized using ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA), which provides a list of affected pathways from all aspects of cell biology (Krämer et al., 2014). Consistent with a defect in dendritic morphogenesis, the output from IPA remarkably indicated that functions such as cytoskeleton organization, development of neurons, neuritogenesis, outgrowth of neurons, and neurites as well as formation of dendrites were significantly changed in Tie2-deficient PCs (Figures 5B–5F; Figures S7A–S7G; Table S2). Genes within those functional categories included multiple receptors, ligands, and intracellular signaling molecules known to regulate neurite outgrowth and branching (e.g., Bdnf, Cxcl12, Netrin1, Sema3B, Ntrk3/TrkC, EphB8, EphB1, Dscam, Ryk). In addition, the expression of molecules regulating cytoskeleton dynamics (e.g., Cdc42, Rap1Gap, Wasf1), the cytoskeleton structural component Tubb3 (Tubulin beta 3 Class III), and microtubule dynamics were also altered (Figures 5C and 5D; Figures S7F and S7G). Altogether, the sequencing data indicate that absence of Tie2 specifically in PCs results in expression changes of a pool of genes involved in neuronal development, dendritogenesis, and dendritic branching. These data also suggest that Tie2 activation in PCs leads to the regulation of multiple genes, which most likely participate in different steps of dendritic morphogenesis (growth, branching, etc.) and together shape the dendritic tree of these neurons.

Figure 5. PC-specific loss of Tie2 leads to alterations in the expression of genes involved in neuronal wiring.

(A) The PC translatome was sequenced form Pcp2Cre:Rpl22HA/HA and Pcp2Cre:Tie2flox/flox:Rpl22HA/HA animals at P56. The top 100 gene changes (by adjusted p value) are shown ranked by unmodified log2 fold change.

(B) Shortened list of affected pathways analyzed with ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA).

(C–F) Among annotations, “organization of cytoskeleton” (C and D) and “branching of neurites” (E and F) are shown. Total gene changes (IfcShrink fold change) are visualized by volcano plot in (C) and (E). The top 100 up- and downregulated genes of the annotations are shown ranked by unmodified log2 fold change in (D) and (F).

See also Figure S7.

Loss of Tie2 expression in postnatal PCs results in alterations of cerebellum network functionality

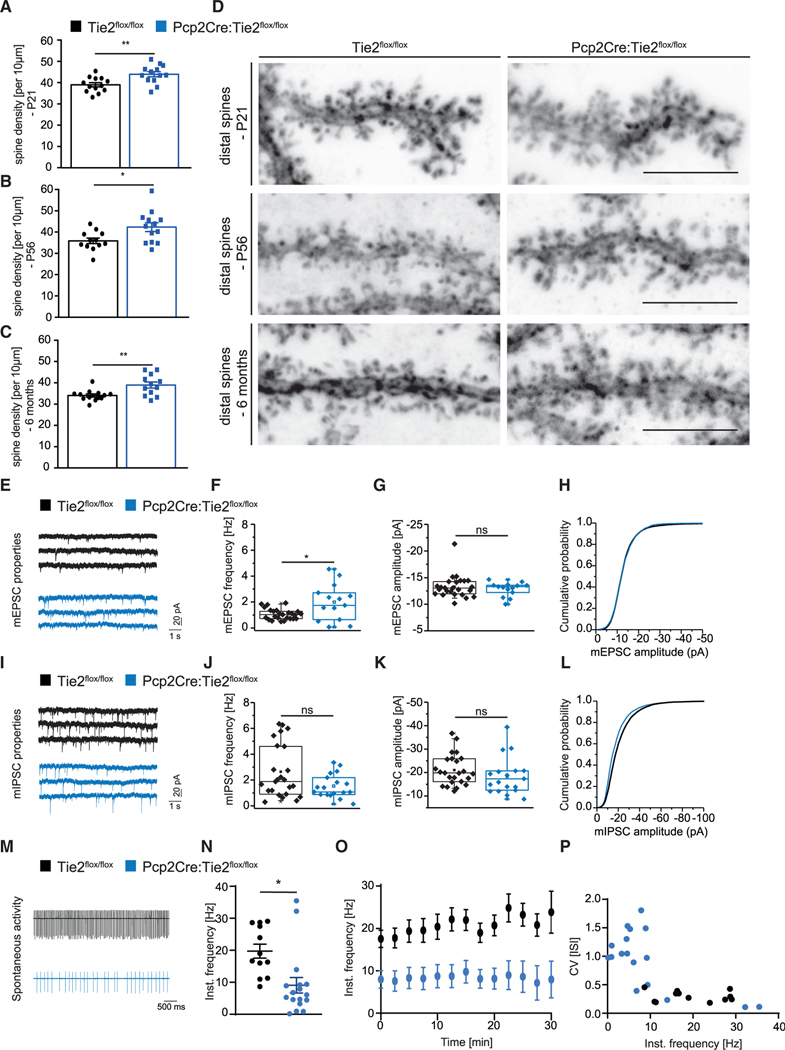

Next, we questioned whether the morphological differences seen in Pcp2Cre:Tie2flox/flox are accompanied by changes on the level of synapses and neuronal electrophysiological properties of PCs. Analysis of dendritic spines in AAV8-infected PCs of the Pcp2Cre:Tie2flox/flox line revealed an increased density of distal spines in all stages analyzed (P21, P56, and 6 months) compared to control mice (Figures 6A–6D). No difference was detected in Pcp2Cre+/− versus Pcp2Cre−/− mice (Figures S4K and S4L). Next, PCs from 8- to 11-week-old Pcp2Cre;Tie2flox/flox mice were patched and recorded to analyze inputs from parallel fibers (mEPSCs) and from GABAergic interneurons (mIPSCs) as described before (Zhang et al., 2015). Consistent with the increase in spine number, PCs from 8–11-week-old Pcp2Cre;Tie2flox/flox animals showed increased mEPSC frequency, albeit its amplitude was unchanged (Figures 6E–6H). mIPSC characteristics were not affected upon deletion of Tie2 (Figures 6I–6L). Last, an additional set of PCs from 8- to 11-week-old Pcp2Cre;Tie2flox/flox animals was patched to analyze their spontaneous activity (spontaneous tonic firing). These electrophysiological recordings showed that spontaneous tonic firing was reduced in Pcp2Cre;Tie2flox/flox animals compared to controls (Figures 6M–6P).

Figure 6. Loss of Tie2 expression in postnatal PCs results in alterations of cerebellum network functionality.

(A–D) Distal dendritic spines were counted in AAV8-transduce PCs of Tie2flox/flox and Pcp2Cre:Tie2flox/flox animals at P21 (A and D), P56 (B and D), and 6 months (C and D). Data are represented as mean ± SEM from a minimum of n = 10 neurons from a minimum of three independent animals. Unpaired Student’s t test; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. Representative pictures are shown in (D). Scale bar: 5 μm.

(E–L) PCs of Tie2lox/lox and Pcp2Cre:Tie2flox/flox animals were patched at 8–11 weeks of age and mEPSCs (E–H) and mIPSCs (I–L) were recorded. Example traces are shown in (E) and (I). Event frequency (F and J), amplitude (G and K), and cumulative probability (H and L) are shown. Data are represented as boxplot from a minimum of n = 14 neurons from a minimum of 4 independent animals.

(M–P) PCs of Tie2lox/lox and Pcp2Cre:Tie2flox/flox animals were patched at 8–11 weeks of age and spontaneous tonic firing was recorded. Example traces are shown in (M). Instantaneous frequency (N–P) was analyzed. Data are represented as mean ± SEM from a minimum of n = 12 neurons from a minimum of 3 independent animals. Unpaired Student’s t test; *p < 0.05; ns, not significant. See also Figure S4.

Collectively, these data suggest that PC function and network is altered in animals lacking Tie2 in PCs.

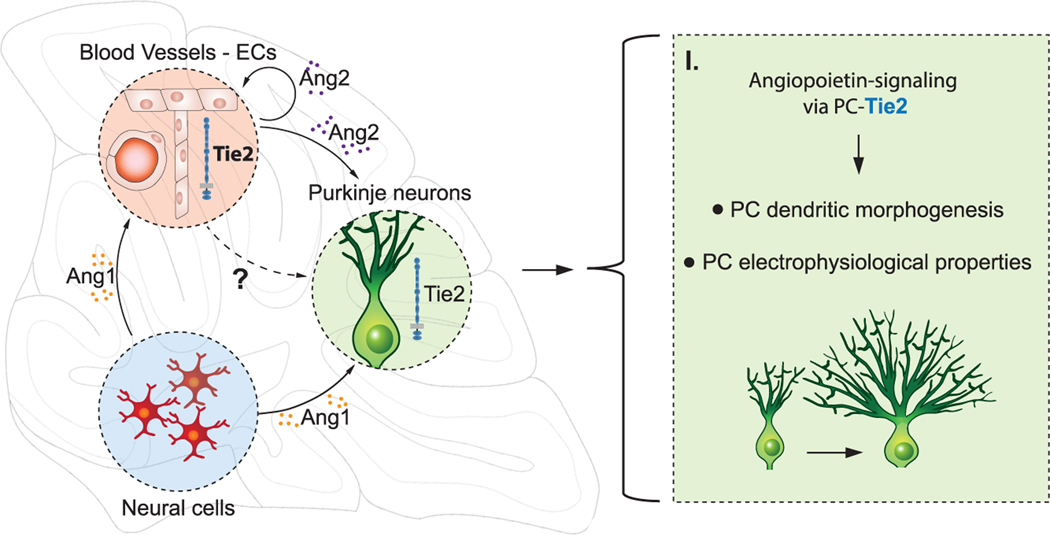

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified a previously undescribed nonvascular role of Tie2 in PCs. We document a role for the angiopoietin-Tie2 pathway as an intercellular communication axis between distinct cell types in the cerebellum during development. We describe a cell-autonomous role for Tie2 in PCs that contributes to the regulation of dendritic morphogenesis, and we also show that angiopoietin ligands derived from the neural and endothelial compartments are important for this process (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Proposed model of Tie2 cell-autonomous effect in PCs.

During development of the mouse cerebellum, Ang1 expressed by neural cells and Ang2 expressed by ECs signal to Tie2, expressed in PCs to modulate dendritic morphogenesis and electrophysiological properties. Angiopoietin ligands expressed during the postnatal development also contribute to the proper formation of the vasculature in the cerebellum, via Tie2 signaling in ECs.

The expression profiling experiments in this study demonstrate that the cognate angiopoietin receptor Tie2, apart from being expressed in the vasculature, is also expressed in PCs of the cerebellum. So far, expression of Tie2 has mainly been described in ECs (Augustin et al., 2009), pericytes, and a subpopulation of monocytes termed TEMs (Tie2-expressing monocytes) (Teichert et al., 2017; Venneri et al., 2007). In the context of neural cells, Tie2-expression has only been reported in neuronal progenitor cells (NPCs) (Androutsellis-Theotokis et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2009; Parati et al., 2002; Rosa et al., 2010). Our study adds to this knowledge and reports expression of Tie2 in differentiated neurons of the cerebellum (PCs) and the hippocampus (pyramidal neurons). Consistent with a previous study (Baldwin et al., 2001), we show that angiopoietins are expressed in the postnatal developing cerebellum during a temporal window when high PC dendritic morphogenesis and cerebellar vascularization take place. These observations are in line with previous reports that describe astrocytes and ECs as the cellular source of Ang1 and Ang2, respectively (Fiedler et al., 2006; Michinaga et al., 2020; Ward et al., 2005). Here, we extend those findings and further show that Ang1 is also expressed in GABAergic interneurons. These combined expression patterns, together with our functional in vivo analysis (see below for further discussion), suggest that a controlled inter-neural-vascular communication is required for proper cerebellar development.

The role of the Ang-Tie2 signaling axis in neurodevelopment processes in vivo was so far little characterized. In our study, we show that Tie2 expression in cerebellar PCs has a cell-autonomous role in regulating PC dendritic morphogenesis. The observed morphological changes of dendritic branching are in a similar range as those occurring reported before (Gibson et al., 2014; Kawabata Galbraith et al., 2018; Kuwako and Okano, 2018). PC-specific loss of Tie2 resulted in a transient increase in dendritic branching at earlier time points, which, however, was not maintained and finally led to a reduced dendritic complexity at later stages. This transient increase might be interpreted as compensatory reaction of PCs trying to compensate for the lack of Tie2. This compensatory mechanism, although active at early time points, is not sufficient, and PCs end up with reduced dendritic branches. Moreover, our data might also suggest that Tie2 receptor in PCs is required for dendritic maintenance. A similar role is attributed to Tie2 in the vascular context, where Tie2 expression is essential during embryogenesis but also contributes to the maintenance of vessels in postnatal stages (Augustin et al., 2009).

A variety of extracellular signaling molecules, membrane receptors, and intracellular signaling components have been described to regulate dendritic morphogenesis. These include Slits, BDNF, Ryk, TrkC, PKCγ, NF-κB-RelA, and mTOR signaling molecules among others (Angliker et al., 2015; Fujishima et al., 2012; Gibson et al., 2014; Joo et al., 2014; Lanoue et al., 2017; Li et al., 2010; Schrenk et al., 2002; Schwartz et al., 1997). Our sequencing data in Tie2-deficient PCs revealed that a great number of genes involved in neuronal and dendritic development change their expression upon loss of Tie2, indicating a complex regulatory network of downstream pathways that is affected by Tie2. In ECs, Ang1-Tie2 signaling activates the PI3K/Akt pathway that subsequently regulates mTOR activity (Kim et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2015). TSC2, mTOR, and Raptor are described to regulate PC dendritic development (Angliker et al., 2015; Reith et al., 2013; Thomanetz et al., 2013). Notably, expression of these genes was reduced in PCs of Pcp2Cre;Tie2flox/flox animals, supporting the hypothesis that Tie2-signaling might also affect this pathway, in PCs similar to its role in ECs.

Consistent with the requirement of a precise and controlled Tie2 activation in PCs, mice with neural-specific deletion of Ang1 or Ang2-null mice presented similar PC dendritic defects as the ones observed in mice with PC-specific deletion of Tie2. As mild vascular changes were present upon homozygous disruption of ligand expression, it cannot be completely ruled out that the vasculature contributes to the PC dendritic arborization defects in those animals. However, the fact that heterozygous mice show reduced PC dendritic complexity but no obvious vascular impairment as well as the phenotype of the PC-specific knockout of Tie2 points toward a cell-autonomous mechanism and suggest that the observed phenotypes in Ang1 and Ang2-transgenic mice are (at least in part) mediated by the lack of direct signaling to PC-Tie2. Whether other mechanisms could be altered upon lack of Ang1 or Ang2 (e.g., differential angiocrine signaling from ECs) requires further investigation.

While certain molecules are known to regulate dendritic branching, they do not regulate self-avoidance mechanisms and vice versa (Gibson et al., 2014; Kaneko et al., 2011; Kuwako and Okano, 2018). In this respect, molecular regulation of dendritic self-avoidance and planarity in PCs is incompletely understood. Here, we find that, while the absence of neural-derived Ang1, or the complete absence of Ang2, change the degree of PCs self-avoidance, PCs with specific deletion of Tie2 do not show any defects. Two models could explain these phenotypes: (1) Tie2 in PCs is required for proper self-avoidance but its deletion activates compensatory mechanisms that compensate the phenotype. Alternatively, (2) Tie2 is only required for dendritic branching but not for self-avoidance. If so, the latter would imply that Ang1/Ang2 might act on PCs to regulate self-avoidance perhaps by binding another receptor such as integrins, or that Ang1/Ang2 act on the vasculature, which in turn (either as a physical barrier or via direct signaling) affects PC dendritic self-avoidance. Further studies will be needed to elucidate these different possibilities.

The changes in PCs dendrite morphogenesis upon loss of Tie2 were accompanied by an increase in distal spine density. Consistent with increased spine density, mEPSC frequency was also increased in PCs of Pcp2Cre;Tie2flox/floxmice. Interestingly, cumulative synapse formation has been shown to inhibit dendritic growth (Takeo et al., 2021). Thus, it is possible that the decrease in dendritic complexity could be partially due to an increase in synapse number. Whether these defects are also reflected at a behavioral level remains to be determined.

Notably, perinatal hypoxia in mice has been associated with reduced PC dendritic arborization (Ramani et al., 2013; Sathyanesan et al., 2018; Scheuer et al., 2018). As changes in oxygen level strongly affected angiopoietin expression (Abdulmalek et al., 2001; Gustavsson et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2000), it is tempting to hypothesize that changes in physiological oxygen concentrations during cerebellar development, or in pathological conditions, regulate angiopoietin expression. This might represent a mechanism adapting PC dendritic growth and branching as well as cerebellar vascular development to the environmental conditions.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Carmen Ruiz de Almodóvar (carmen.ruizdealmodovar@medma.uni-heidelberg.de).

Materials availability

All unique reagents generated in this study are listed in the Key resource table and available from the lead contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Antibodies | ||

|

| ||

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Ang1 | Abcam | ab8451 |

| anti-chicken-Alexa488 | Molecular Probes | A11039 |

| anti-goat-Alexa488 | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 705–545-033 |

| anti-goat-Alexa568 | Molecular Probes | A11057 |

| anti-mouse-Alexa488 | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 115–545-146 |

| anti-mouse-Alexa568 | Invitrogen | A11031 |

| anti-rabbit-Alexa488 | Invitrogen | A11008 |

| anti-rabbit-Alexa488 | Invitrogen | 711–545-152 |

| anti-rabbit-Alexa568 | Jackson ImmunoResearch | A10042 |

| anti-rat-Alexa594 | Molecular Probes | A21209 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-CALBINDIN-D-28K(clone CB-955) | Sigma-Aldrich | C9848 |

| Rat monoclonal anti-CD13 | Bio-Rad | MCA2183GA |

| Goat polyclonal anti-CD31 | R&D | AF3628 |

| DAPI | Invitrogen | D1306 |

| Goat polyclonal anti-GFAP | Abcam | ab53554 |

| Chicken polyclonal anti-GFP | Aves | GFP-1020 |

| IsolectinB-Alex568 | Invitrogen | I21412 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-OLIG2 | Millipore | MABN50 |

| TO-PRO-3 | Invitrogen | T3605 |

|

| ||

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

|

| ||

| Agarose | Sigma-Aldrich | A9538 |

| Ampicillin sodium salt | Sigma-Aldrich | A9518 |

| Anti-HA-tag mAb-Magnetic Beads | MBL | M180–11 |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Roth | 8076.2 |

| Calcium chloride dihydrate | AppliChem | A3587 |

| cDNA synthesis SuperScript® Vilo | Invitrogen | 11754–050 |

| D(+)-Saccharose | Roth | 4621.1 |

| Deoxynucleotides (dNTPs) | NEB | N0447S |

| DEPC | Sigma-Aldrich | D5758 |

| Dextran Sulfate Sodium (DSS) | MP Biomedicals | SKU 0216011050 |

| DIG Blocking Reagent | Roche | 11096176001 |

| Digoxigenin (DIG) RNA labeling kit | Roche | 11175025910 |

| Dimethylsulfoxid (DMSO) | Gruesing | 10282 |

| DNA ladder 1 kb | Thermo Scientific | SM0311 |

| DNA ladder 100 bp | NEB | N3231S |

| DNA loading dye (6×) | Thermo Scientific | P0611 |

| DNA stain | Serva | 39803.01 |

| DNase I, Rnase-free | Thermo Scientific | EN0521 |

| DNaseI | Sigma-Aldrich | 4716728001 |

| EDTA | AppliChem | A3553 |

| Ethanol | Sigma-Aldrich | 32205 |

| Fast Green FCF | Sigma-Aldrich | F7252 |

| Fast SYBR Green Master Mix | Thermo Scientific | 408995 |

| Fluoromount-G | Linaris | 0100–01 |

| Formamid | Sigma-Aldrich | 47670 |

| Gelatine from porcin skin | Sigma-Aldrich | G1890 |

| GenElute Plasmid Miniprepkit | Sigma-Aldrich | PLN70–1Kt |

| Hydrochloric acid solution, 1 M | Sigma-Aldrich | 35328 |

| Isofluran | Sigma-Aldrich | 792632 |

| Isopropanol | VWR | ACRO423830010 |

| Ketamin (10%) | Bremer Pharma GmbH | 27015.00.00 |

| LB-Medium (BactoTMAgar) | BD | 214010 |

| LB-Medium (BactoTMTryptone) | BD | 211705 |

| LB-Medium (BactoTMYeast Extract) | BD | 212750 |

| Levamisol | Sigma-Aldrich | BP212 |

| Lidocain | Aspen Pharma Trading Limited | PL 39699/0086 |

| Magnesium chloride | AppliChem | A3618 |

| Maleic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | M0375 |

| mAng1 recombinant protein | R&D Systems | 9936-AN |

| mAng2 recombinant protein | R&D Systems | 7186-AN |

| Maxima Reverse Transcriptase | Thermo Scientific | EP0742 |

| Methanol | Sigma-Aldrich | 32213 |

| Mowiol® 4–88 | Sigma-Aldrich | 81381 |

| NBT/BCIP | Promega | S3771 |

| NEB T4 DNA Ligase | NEB | M0202 |

| NEG-50TM | Thermo Scientific | 6502 |

| Normal donkey serum | Dianova | 017–000-121 |

| Normal goat serum | Dianova | 005–000-121 |

| NucleoSpin® Gel and PCR Clean-Up | Nachery-Nagel | 740609.25 |

| PCR-CleanUp | Promega | A9281 |

| Phosphate Buffer Saline | Sigma-Aldrich | D8537 |

| Plasmid Plus MAXI kit | QIAGEN | 12963 |

| Potassium chloride | AppliChem | A3582 |

| Potassium dihydrogenphosphate | AppliChem | A3620 |

| Q5® HighFidelity DNA Polymerase | NEB | M0491 |

| Sodium bicarbonate | Sigma-Aldrich | 31437 |

| Sodium chloride | Sigma-Aldrich | 31434 |

| Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) | Roth | CN30.3 |

| Sodium hydroxyde | Sigma-Aldrich | 30620 |

| Sodium phosphate dibasic dihydrate | Sigma-Aldrich | 4272 |

| Sodium phosphate monobasic monohydrate | Sigma-Aldrich | 71504 |

| Tissue-Tek® O.C.T. Compound | Genprice | 4583 |

| Tneasy® Mini kit | QIAGEN | 74104 |

| Torula RNA | Merck | 10109223001 |

| tris(hydroxymethyl)aminoethane (TRIS) | Roth | 4855.2 |

| Triton X-100 | Merck | 108603 |

| TRIzol Reagent | Thermo Scientific | 15596026 |

| Trypsine-EDTA | Sigma-Aldrich | T3924 |

| Tween®20 | Roth | 9127.1 |

| Wizard®SV Gel and PCR CleanUp System | Promega | A9281 |

| Xylavet (20 mg/ml) | CP-Pharma Handelsges. mbH | 401510.00.00 |

|

| ||

| Deposited data | ||

|

| ||

| RNA-seq data | this study | GSE178659 |

|

| ||

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

|

| ||

| Ang1flox/flox | (Jeansson et al., 2011) | N/A |

| Ang2−/− | (Hu et al., 2014) | N/A |

| NesCre | (Tronche et al., 1999) | N/A |

| Rosa26:mTomato-mGFP | (Muzumdar et al., 2007) | N/A |

| Jackson Laboratories | ||

| JAX stock #007676 | ||

| Pcp2Cre | (Barski et al., 2000) | N/A |

| Rpl22HA/HA | (Sanz et al., 2009) | N/A |

| Jackson Laboratories | ||

| JAX stock #011029 | ||

| Tie2flox/flox | (Savant et al., 2015) | N/A |

| Tie2-GFP | (De Palma et al., 2005) | N/A |

|

| ||

| Oligonucleotides | ||

|

| ||

| See Table S3 | N/A | |

|

| ||

| Software and algorithms | ||

|

| ||

| DEseq2 | (Love et al., 2014) | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html |

| FastQC | Freeware (Andrews, 2010) | https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ |

| Fiji - ImageJ | Freeware (Schindelin et al., 2012) | https://imagej.net/software/fiji |

| GraphPad Prism 6/7 | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com |

| HTSeq-count | (Anders et al., 2015) | https://htseq.readthedocs.io/en/release_0.11.1/overview.html |

| IMARIS 8.4.2 | Bitplane AG | https://imaris.oxinst.com/ |

| IPA | QIAGEN Inc. (Krämer et al., 2014) | https://digitalinsights.qiagen.com/products |

| Microsoft Office | Microsoft | https://office.live.com/start/Excel.aspx |

| R | Freeware (R Team, 2020) | https://cran.r-project.org/ |

| samtools | (Li et al., 2009) | http://www.htslib.org/ |

| STAR | (Dobin et al., 2013) | https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR |

Data and code availability

This paper also analyzes existing, publicly available data (scRNaseq). The accession number for the dataset is listed in the Key resource table.

RNaseq FASTQ files generated in this study are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (accession number GSE178659).

All original code is available in this paper’s supplemental information

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell lines

HEK293 cells were cultured in DMEM medium, supplemented with 10% v/v of fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% l-glutamine, penicillin (100 IU mL−1), and streptomycin (100 mg mL−1). Cell were grown at 37°C.

Animals

The animal welfare officers and the local authorities approved all animal experiments performed in this study (G47/16, G118/16, I19/13, T38/19, T48/18, T36/17, T46/16 and T49/15). Wild-type (CD1 or C57BL/6) animals were purchased from Janvier Labs and Charles Rivers. Transgenic animals were kept and bred in the local IBF facility of the University Heidelberg. Ang1flox/flox animals were previously described (Jeansson et al., 2011) and kindly provided by Susan E Quaggin. Ang1flox/flox mice were crossed with Nestin-Cre mice (Tronche et al., 1999). Ang2−/− and Tie2flox/flox animals were bred and used as previously described (Hu et al., 2014; Savant et al., 2015). Pcp2Cre mice (Barski et al., 2000) were kindly provided by Jaroslaw J Barski. Rpl22HA/HA and Rosa26:mTomato-mGFP animals (Muzumdar et al., 2007) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. Tie2-GFP mice were described previously (De Palma et al., 2005).

Animal models in this study are listed in Key resource table. Wild-type (CD1 or C57BL/6) animals were purchased from Janvier Labs and Charls Rivers. Transgenic animals were kept and bread in the local IBF facility of the University Heidelberg. Animals were fed at the condition of 25°C and 55% of humidity and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Heidelberg University. All animal experiments were performed in compliance with all institutional and national guidelines. Both sexes were used in the experiments and randomly assigned to experimental groups. In this study mice were used until 6 months of age. The specific stages are indicated in the Figures.

METHOD DETAILS

Virus production, intracranial viral injections into the cerebellum

AAV8-YFP production: to produce AAV8-YFP, a triple-plasmid transfection protocol using polyethylenimine, purification by cesium chloride density gradient centrifugation and titration by quantitative real-time PCR were used, as previously reported (Fakhiri et al., 2019). Intracranial injection of viruses was performed in pups (P7) and adults (> 6 weeks). Animals were anaesthetized using isoflurane (anesthesia initiation − 3%−2.5%; later − 2.5%−2.0%). Once the animal was deeply anaesthetized, the head was fixed in a stereotaxic device. The skin was shaved, numbed using lidocain spray (10% solution) and disinfected with 70% ethanol. A small incision was made into the skin above the cerebellum. Lambda (posterior fontanelle) was used as reference point for the injection coordinates (A/P −1.8 to −2mm; M/L 0mm; D/V −1.8 to −2mm). 500nl (pups) or 800nl (adults) of AAV8-YFP at a concentration of 1.6*1010 viral particles per ml were injected at a rate of 200nl/min using a micro injector and a Hamilton pipette. Virus was provided by Dirk Grimm (Center for Infectious Diseases; Heidelberg University). For pups, the incision of the skin was closed using 3M Vetbond Tissue Adhesive, whereby the wound of adult animal was sutured. The mice were kept on a heat plate (37°C) until they woke up and then placed back into the home cage. Animals were under continuous observation.

Tissue processing

Animals were intraperitoneally injected with ketamin/xylazin (70mg/kgBW /7mg/kgBW). Transcardial perfusion was performed for 5 min with PBS followed by 5min with 4% PFA solution. The brain was post-fixed with 4% PFA solution over night at 4°C and subsequently washed with PBS. Tissue for later cryo-sectioning was equilibrated in 30% sucrose solution (in PBS) prior embedding in Tissue-Tek® O.C.T. Compound and freezing in liquid nitrogen. PBS and PFA solutions used for ISH were previously treated with DEPC (0.1% prior autoclaving).

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization (ISH) was performed on cryo-sections to localize mRNA in mouse brain tissue. Cryo-sections were hybridized with digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled antisense riboprobes (see Key resource table) in ISH hybridization buffer at a concentration of 500ng/ml. Riboprobes of the respective sense sequence were used as negative control. Hybridization was carried out o/n at 68°C. Sections were washed first with 1x SSC buffer containing 50% formamide and 0.1% Tween®20 and subsequently with 1x MAB containing 0.1% Tween®20. Sections were blocked with 2% DIG Blocking Reagent solution before applying anti-DIG antibody coupled to alkaline phosphatase 2h at RT (dilution 1:500). Subsequently, the sections were washed again with 1x MAB containing 0.1% Tween®20. Nitroblue tetrazolium/5-bromo/4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (NBT/BCIP concentrated at 340μg/ml and 175μg/ml ISH staining buffer) was used as chromogenic substrate. The reaction was stopped by washing with water and sections were post-fixed for 30min with 4% PFA. In case of a subsequent immunofluorescent staining the protocol described below was followed.

Immunofluorescent staining

Sagittal tissue sections were prepared using a vibratome (100μm thick slices, if not stated different) or cryostat (20μm thick slices, if not stated different). Primary and secondary antibodies used for immunofluorescent staining are listed in the key resource table. Dilutions are indicated. Briefly, sections were blocked 1h at RT in blocking solution (PBS, 1% BSA, 2% serum (depending on secondary combination) and 0.5% Triton X-100). Primary and secondary antibodies were applied in staining solution (PBS, 1% BSA, 2% serum (depending on secondary combination) and 0.3% Triton X-100). Primary antibodies were incubated at 4°C for 24h (20μm cryo-sections) or 48h (free-floating 100μm vibratome sections), respectively. Secondary antibodies were incubated at RT for 2h (20μm cryo-sections) or at 4°C for 24h (free-floating 100μm vibratome sections), respectively.

Golgi staining

Brain tissue was incubated in Golgi staining solution (1% potassium dichromate, 1% mercury chloride, 0.8% potassium chromate) for 2 days at 37°C before changing the solution to 30% sucrose in water. Sections of 250 μm were cut at the vibratome and stored in 6% sucrose in water. Sections were incubated in 15% ammonia solution for 30 min to develop Golgi reaction. Subsequently, tissue was washed with 5% sodium thiosulfate solution, dehydrated and mounted using Eukitt® medium.

Organotypic cerebellar slice cultures

Organotypic cerebellar slice cultures were prepared from P6 WT pups (for rAng1 stimulation to analyze dendritic branching) and from P13 in the case of Pcp2Cre;Rpl22HA/HA and Pcp2Cre;Tie2flox/flox;Rpl22HA/HA animals. To prepare slices pups were sacrificed through decapitation and the brain was isolated in ice-cold dissection medium (BME; 0.45% glucose; 50mg/ml BSA; 2x glutamine; 1× ITS; 1× Penicillin/Streptomycin). The cerebellum was dissected and the meninges were removed. Cerebellar slices of 350μm were prepared using a McIlwain Tissue Chopper. Slices were transferred onto Millicells and cultured. For morphological analysis, cultures were stimulated with 100ng/ml rAng1 (R&D Systems; 923-AN) over the course of 3 days (half of the medium was replaced after 2 DIV and Ang1 stimulation was renewed). Experiment was stopped by adding warm 8% PFA containing 20% sucrose into the medium for 1h at RT. For qPCR analysis, slices were stimulated with 100ng/ml rAng1 for 24h and subsequently snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for future processing.

Microscopy

Images of fluorescent and Golgi-staining were collected on a confocal microscope: Zeiss LSM510 unit mounted on Axiovert 200M inverted microscope; Zeiss LSM800; Nikon AR1. For Golgi-staining a reflection setting was used. ISH images were taken with stereo microscope SMZ1270i. Pictures were taken at 1024X1024 resolution using 10x, 20x or 40x objectives. Serial z stacks were taken from the scanned images. Data were saved as .lsm, .czi or .zvi file format. Digital processing of pictures was done using FIJI software (Schindelin et al., 2012).

Reconstruction and quantification of dendritic morphology

PC dendritic arbors from in vitro slice culture experiments (lobe V and IX; from minimum 3 independent experiments) and in vivo AAV-injected animals (lobe II-V from minimum 10 neurons of minimum 3 pups) were reconstructed using FIJI software plugin “Simple Neurite Tracer” (Version 3.1.6). The total length of dendrites as well as the number of dendritic branches was extracted from the .csv file. Using “Simple Neurite Tracer,” a filling of the dendritic traces was generated to clear all background and get a binary picture of the dendritic arbor.

Imaris 8.4.2 software was used to assess the number of dendritic crosses. Briefly, the binary picture of the traced dendrites was processed and skeletonized to analyze the number of loop structures, which serve as readout for dendritic self-association. These were manually counted.

Using an R language script, we analyzed PC dendritic planarity in our traced neurons. The branch endpoints were extracted from the .csv files. All points in the three two-dimensional projections (X-Y; X-Z; Y-Z) were aligned and rotated by the angle that was defined by the center of the PC-soma (first starting point in all .csv files) and the center of mass of each two-dimensional projection (see Data S1: 3DRepresentationofPurkinjecellendpoints.html file). Subsequently, the maximum width of the endpoints in the Z axis was quantified. Additionally, we wanted to visualize the distribution of endpoints in the X-Z axis. For this an ellipse containing the 95% percentile density of all branch endpoints was generated from the pooled data of control animals of each mouse line. The ellipse was fitted onto the data of all neuron from the same dataset and the percentage of branch endpoints outside the ellipse was measured (see Data S2: Ellipsoid_calculator.html file).

Quantitation of PC spines

High magnification images (63×) of PCs were taken of the AAV8-YFP injected animals used before for morphological analysis. Distal spines were manually counted using FIJI software plugin “Cell Counter” and normalized to the length.

Quantitation of blood vessel length and pericyte coverage

The length of blood vessels and the coverage of blood vessels with pericytes were analyzed in the different layers of the cerebellum using FIJI software. Pictures were taken from lobes V and IX (1–2 pictures per lobe and section; 3–5 sections per mouse). Confocal image Z stacks of blood vessels (CD31) and pericytes (CD13) were projected to a single picture with the maximum intensity. A binary picture was generated for the blood vessel and pericyte staining. Nuclear staining of TO-PRO-3 was used to identify cerebellar layers. The signal-area of pericytes that overlaid with the blood vessel area was measured (pericyte coverage). Binary pictures of the blood vessel stain were further processed using a Gaussian Blur (sigma = 2) and auto-threshold. Particles smaller than 10 pixel were considered background and were removed. The final binary picture was processed with the FIJI plugins “Skeletonize (2D/3D)” and “Analyze Skeleton (2D/3D)” to quantify the length and number of blood vessel branches.

Rpl22HA/HA pull-down

The pull-down of Rpl22HA/HA was performed as described before (Sanz et al., 2009) using the Pcp2Cre:Rpl22HA/HA and Pcp2Cre:-Tie2flox/flox:Rpl22HA/HA mouse lines. In short, cerebellar tissue samples were homogenized on ice in 10% w/v polysome buffer. Samples were centrifuged for 10min at 12.000rpm at 4°C, supernatant was collected and 10ml were kept as input. Remaining sample was incubated o/n at 4°C with anti-HA antibody-coated magnetic beats. Magnetic beads were washed with ice-cold HS-buffer and finally re-suspended in RLT buffer from RNeasy® Mini Kit (QIAGEN; 74104). The mRNA enrichment of PC-marker genes Pcp2 and Calbindin as well as EC-marker genes CD31 and VE-cad in the purified fraction over the input were checked to assess the quality of the pulldown (Figures 2D and 2E).

RNA sequencing and analysis

Library preparation and sequencing were performed by BGI Genomics, China. Sequencing quality check was performed with FastQC (Andrews, 2010). Mapping was performed with STAR (Dobin et al., 2013) to the mouse genome from Ensembl (Mus_musculus.GRCm38.98)(Yates et al., 2020), and the indexing with samtools (Li et al., 2009). Read counting was done using HTSeq-count (Anders et al., 2015). Differential expression analysis was done with DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014) package in R (R Team, 2020), using genotype and sequencing batch as variables. Results were obtained from the genotype differences. Data were analyzed through the use of IPA (QIAGEN Inc., https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuity-pathway-analysis) (Krämer et al., 2014). The IPA output was visualized using R scripts.

Animals and slice preparation

Mice were sent from Heidelberg according to the given guidelines of Baden-Württemberg and Rhineland-Palatinate. Before the experiments, mice were housed for at least one week in the animal housing of the BFZ of the University Medicine Mainz under a 12h/12h light/dark cycle and had access to water and food ad libitum.

Animals of 8–11 weeks old (aprox. postnatal days 67–79) were used in electrophysiological experiments. All mice were handled according to the guidelines of the Landesuntersuchungsamt (LUA) Rheinlandpfalz and were anesthetized with isoflurane and decapitated. Mice were transcardially perfused with ice-cold sucrose containing solution bubbled with carbogen gas using the following composition (in mM): Sucrose (212), KCl (3), NaH2PO4 (1.25), MgCl2 (7), CaCl2 (0.16), NaHCO3 (26), glucose (10). The brain was quickly removed and sectioned to contain the vermis region of the cerebellum.

Sagittal slices of the vermis of the cerebellum at a thickness of 250 μm were made using a Leica VT1200S at a speed of 0.1 mm/s and 1 mm amplitude using Personna razor blades. Slices were transferred into carbogen-bubbled Ringer’s solution for 30 min at 34°C for recovery containing (in mM): NaCl (125), NaHCO3 (25), KCl (2.5), NaH2PO4 (1.25), CaCl2 (2), MgCl2 (1), glucose (25). Slices were kept at room temperature until recording.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell voltage clamp recordings were performed at a holding potential of —70 mV in Ringer’s solution containing (in mM): NaCl (125), NaHCO3 (25), KCl (2.5), NaH2PO4 (1.25), CaCl2 (2), MgCl2 (1), glucose (25) and 1 mM TTX to block Na+-channels. For mEPSC recordings, 10 μm gabazine and 50 μm APV was added to block GABA receptor- and NMDA receptor-mediated currents, respectively. For mIPSC recordings, 50 μm APV and 10 μm CNQX was added to block NMDA and AMPA mediated currents, respectively. Recording electrodes were made using borosilicate glass pipettes with a resistance of 3–5 MU when filled with intracellular recording solution containing in mM (for mEPSC recording): Cs+-methanesulfonate (120), CsCl (10), EGTA (0.2), HEPES (10), Phosphocreatin- Na+ (0.1), ATP-Mg2+ salt (2), NaCl (8), GTP (0.3) or (for mIPSC recording): CsCl (145), HEPES (10), EGTA (0.1), ATP-Mg2+ salt (2), MgCl2 (2). Series resistance was continuously monitored by applying a +5 mV pulse at the start of each sweep. Cells exceeding 30 MΩ series resistance were omitted. All recordings were performed at room temperature using an EPC10 double USB patch clamp amplifier with Patchmaster software (HEKA Elektronic, Germany). Signals were filtered with two Bessel filters (2.9 and 10 kHz) and digitized at 20 kHz. Purkinje cells in the vermis region of the cerebellum (lobes IV-V) were visualized on an upright Olympus BX51W1 microscope with differential interference contrast (DIC) optics using a 40× water immersion objective (LUMPlanFl/IR 40× 0.80 W) and an Olympus XM10 digital camera. Miniature current analysis was performed with Clampfit software using a template matching algorithm (10.2.0.13, MDS Analytical Technologies, 2007).

Data analysis

Data was subjected to Shapiro Wilks test for normality and if normal distribution was given, a subsequent two sample t test was performed. In case of a rejected normal distribution a non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was performed using R scripts. Differences between two groups leading to p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Electrophysiological recordings of spontaneous activity: Slice preparation

Mice, female and male, 8–11 weeks old, were decapitate under deep isoflurane anesthesia. All experiments were conducted in accordance with international guidelines from the European Community Council Directive and with the local guideline on the ethical use of animals. The cerebellum was removed and immersed into ice-cold (2–3°C) “slicing” solution containing (in mM): 240 sucrose, 5 KCl, 1.25 Na2HPO4, 2 MgSO4, 1 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3 and 10 D-Glucose, bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Cerebellar vermis was isolated and parasagittal slices (220 μm thick) were cut using a vibratome (VT1200S, Leica). Slices were incubated for at least 1 h before recordings in ACSF containing (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 Na2HPO4, 1 MgSO4, 2 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3 and 25 D-Glucose, bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2, maintained at 32°C.

Electrophysiological apparatus and patch-clamp recordings

For electrophysiological recordings, slices were transferred to the recording chamber and perfused at 1.5 mL min −1 with ACSF in the presence of 100 μm picrotoxin unless stated otherwise, bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2, at room temperature (RT; 20–23°C). Slices were visualized with an upright microscope equipped with a × 63, 0·9 NA water-immersion objective and differential interference contrast (DIC) optics (Scientifica, UK).

Patch pipettes were made from thick-walled borosilicate glass capillaries with filament (GB150F-8P, Science Product) by means of a Sutter P-1000 horizontal puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA). Recordings were obtained in patch-clamp cell-attached configuration using an Axoclamp 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA, USA).

For cell-attached recordings (10–80MΩseal resistance), patch pipettes were filled with standard extracellular saline. Pipettes were held at 0 mV in the voltage-clamp mode. Consecutive 140 s. current traces were filtered at 2 kHz and acquired at 50 kHz sampling rate. In these conditions, recorded spikes appear as biphasic current deflections (6M, right inset). Recordings were judged to be stable when the shape and frequency of spikes was constant over time (6M). Stable recordings were routinely obtained for as long as 20–30min (6M).

Data analysis

In cell-attached recordings, firing frequency (Inst. Freq.) of the tonic simple spikes was evaluated with the event-sorting function in pClamp 10 Software suite; the variability of the interspike interval (ISI) was calculated from the mean ISI and the ISI coefficient of variation (CV(ISI)) computed as standard deviation of interspike intervals (ISI)/mean of ISI . Each Freq. and CV(ISI) value was computed from an event-sample recorded over a time window of 140 s. All values are represented as mean ± s.e.m, p values of < 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analysis was done using unpaired Student’s t test, unless stated otherwise.

qRT-PCR analysis

RNA from RiboTag-tissue was isolated by using the RNeasy® Mini Kit, following manufacturer’s instructions. RNA from whole cerebellum was isolated using TRIzol Reagent. RNA was DNaseI-treated and reverse-transcribed using either Maxima Reverse Transcriptase or SuperScript®Vilo. qRT-PCR was performed using Fast SYBR Green Master Mix to assess mRNA expression levels. Gapdh served as control for normalization. The qRT-PCR primers are listed in the key resource table.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc.). All data are shown as mean ± SEM if not stated otherwise. The unpaired Student’s t test was used for comparison between two groups, if not stated otherwise. One-way ANOVA together with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used for comparison between multiple groups to the same control condition. The investigator was blinded for all analysis. The experiments were not randomized and no samples were excluded from the analysis. Statistical significance was defined as *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001. Statistical details of the experiments can be found in the respective figure legends.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Ang1 and Ang2 are expressed in cerebellar neural and endothelial cells, respectively

The angiopoietin receptor Tie2 is expressed in blood vessels and Purkinje cells

Tie2 signaling regulates PC dendritic morphogenesis in a cell-autonomous manner

PCs network functionality is altered in PC specific Tie2-deficient mice

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Nikon Imaging Center, the Math-Clinic, and the INBC of the University of Heidelberg for their support. We thank Prof. Susan E. Quaggin for providing the Ang1fl/fl mice (supported by the National Institutes of Health (P30 DK114857 [PI-SEQ]), Prof. Barski for the Pcp2-Cre mice, and Prof. Dr. Hannah Monyer for the Nestin:Cre mice. We thank Andreas Fischer and Juan Rodriguez-Vita for their support with the IPA analysis. We thank Melanie Richter, Alberto Arenas Molina, Daniel Maeso Miguel, Philip Ruthig, and Yi Lien for technical assistance and Prof. Daniela Mauceri and the entire Ruiz de Almodovar lab for useful discussions. The authors gratefully acknowledge the data storage service SDS@hd supported by the Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts Baden-Württemberg (M.W.K.) and the German Research Foundation (DFG) through grant INST 35/1314–1 FUGG and INST 35/1503–1 FUGG. R.L. was supported by a Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds fellowship. This work was supported by the Schram Foundation and the Chica and Heinz Schaller Foundation, by research grants of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) from FOR2325 (“Interactions at the Neurovascular Interface” [to C.R.d.A and R.H.A.]), by DFG grants from SFB1366 (“Vascular Control of Organ Function;” Project number 394046768-SFB 1366; [to C.R.d.A., R.H.A., and H.G.A.]), by funds from the Baden-Württemberg Stiftung special programme “Angioformatics Single Cell Platform” (to C.R.d.A. and to H.G.A.), and by the European Research Council Consolidator grant 864875 “OLI.VAS” (to C.R.d.A.) and ERC Advance Grant 787181 “Angiomature” (to H.G.A.).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109522.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

INCLUSION AND DIVERSITY

One or more of the authors of this paper self-identifies as a member of the LGBTQ+ community.

REFERENCES

- Abdulmalek K, Ashur F, Ezer N, Ye F, Magder S, and Hussain SN (2001). Differential expression of Tie-2 receptors and angiopoietins in response to in vivo hypoxia in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 281, L582–L590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamaszek M, D’Agata F, Ferrucci R, Habas C, Keulen S, Kirkby KC, Leggio M, Mariën P, Molinari M, Moulton E, et al. (2017). Consensus Paper: Cerebellum and Emotion. Cerebellum 16, 552–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S, Pyl PT, and Huber W. (2015). HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews S. (2010). FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data, http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/.

- Androutsellis-Theotokis A, Rueger MA, Park DM, Mkhikian H, Korb E, Poser SW, Walbridge S, Munasinghe J, Koretsky AP, Lonser RR, and McKay RD (2009). Targeting neural precursors in the adult brain rescues injured dopamine neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 13570–13575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angliker N, Burri M, Zaichuk M, Fritschy JM, and Rüegg MA (2015). mTORC1 and mTORC2 have largely distinct functions in Purkinje cells. Eur. J. Neurosci. 42, 2595–2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin HG, Koh GY, Thurston G, and Alitalo K. (2009). Control of vascular morphogenesis and homeostasis through the angiopoietin-Tie system. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 165–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Cui M, Meng Z, Shen L, He Q, Zhang X, Chen F, and Xiao J. (2009). Ectopic expression of angiopoietin-1 promotes neuronal differentiation in neural progenitor cells through the Akt pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 378, 296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin ME, Catimel B, Nice EC, Roufail S, Hall NE, Stenvers KL, Karkkainen MJ, Alitalo K, Stacker SA, and Achen MG (2001). The specificity of receptor binding by vascular endothelial growth factor-d is different in mouse and man. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19166–19171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barski JJ, Dethleffsen K, and Meyer M. (2000). Cre recombinase expression in cerebellar Purkinje cells. Genesis 28, 93–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffo A, and Rossi F. (2013). Origin, lineage and function of cerebellar glia. Prog. Neurobiol. 109, 42–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts T, Green MJ, and Wingate RJ (2014). Development of the cerebellum: simple steps to make a ‘little brain’. Development 141, 4031–4041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RA, Bihannic L, Rosencrance C, Hadley JL, Tong Y, Phoenix TN, Natarajan S, Easton J, Northcott PA, and Gawad C. (2018). A Single-Cell Transcriptional Atlas of the Developing Murine Cerebellum. Curr. Biol. 28, 2910–2920.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo E, Mazzarello P, Prestori F, Mapelli J, Solinas S, Lombardo P, Cesana E, Gandolfi D, and Congi L. (2011). The cerebellar network: from structure to function and dynamics. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 66, 5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Palma M, Venneri MA, Galli R, Sergi Sergi L, Politi LS, Sampaolesi M, and Naldini L. (2005). Tie2 identifies a hematopoietic lineage of proangiogenic monocytes required for tumor vessel formation and a mesenchymal population of pericyte progenitors. Cancer Cell 8, 211–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, and Gingeras TR (2013). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakhiri J, Schneider MA, Puschhof J, Stanifer M, Schildgen V, Holderbach S, Voss Y, El Andari J, Schildgen O, Boulant S, et al. (2019). Novel Chimeric Gene Therapy Vectors Based on Adeno-Associated Virus and Four Different Mammalian Bocaviruses. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 12, 202–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler U, Reiss Y, Scharpfenecker M, Grunow V, Koidl S, Thurston G, Gale NW, Witzenrath M, Rosseau S, Suttorp N, et al. (2006). Angiopoietin-2 sensitizes endothelial cells to TNF-alpha and has a crucial role in the induction of inflammation. Nat. Med. 12, 235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming JT, He W, Hao C, Ketova T, Pan FC, Wright CCV, Litingtung Y, and Chiang C. (2013). The Purkinje neuron acts as a central regulator of spatially and functionally distinct cerebellar precursors. Dev. Cell 27, 278–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujishima K, Horie R, Mochizuki A, and Kengaku M. (2012). Principles of branch dynamics governing shape characteristics of cerebellar Purkinje cell dendrites. Development 139, 3442–3455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale NW, Thurston G, Hackett SF, Renard R, Wang Q, McClain J, Martin C, Witte C, Witte MH, Jackson D, et al. (2002). Angiopoietin-2 is required for postnatal angiogenesis and lymphatic patterning, and only the latter role is rescued by Angiopoietin-1. Dev. Cell 3, 411–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson DA, Tymanskyj S, Yuan RC, Leung HC, Lefebvre JL, Sanes JR, Cheódotal A, and Ma L. (2014). Dendrite self-avoidance requires cell-autonomous slit/robo signaling in cerebellar purkinje cells. Neuron 81, 1040–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson M, Mallard C, Vannucci SJ, Wilson MA, Johnston MV, and Hagberg H. (2007). Vascular response to hypoxic preconditioning in the immature brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 27, 928–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen TM, Singh H, Tahir TA, and Brindle NP (2010). Effects of angiopoietins-1 and −2 on the receptor tyrosine kinase Tie2 are differentially regulated at the endothelial cell surface. Cell. Signal. 22, 527–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer H, and Mason CA (2003). Thyroid hormone induces cerebellar Purkinje cell dendritic development via the thyroid hormone receptor alpha1. J. Neurosci. 23, 10604–10612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Srivastava K, Wieland M, Runge A, Mogler C, Besemfelder E, Terhardt D, Vogel MJ, Cao L, Korn C, et al. (2014). Endothelial cell-derived angiopoietin-2 controls liver regeneration as a spatiotemporal rheostat. Science 343, 416–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang GJ, Edwards A, Tsai CY, Lee YS, Peng L, Era T, Hirabayashi Y, Tsai CY, Nishikawa S, Iwakura Y, et al. (2014). Ectopic cerebellar cell migration causes maldevelopment of Purkinje cells and abnormal motor behaviour in Cxcr4 null mice. PLoS ONE 9, e86471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ing-Esteves S, Kostadinov D, Marocha J, Sing AD, Joseph KS, Laboulaye MA, Sanes JR, and Lefebvre JL (2018). Combinatorial Effects of Alpha- and Gamma-Protocadherins on Neuronal Survival and Dendritic Self-Avoidance. J. Neurosci. 38, 2713–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]