Abstract

Background

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, a substantial number of emergency health care workers (HCWs) have screened positive for anxiety, depression, risk of posttraumatic stress disorder, and burnout. The purpose of this qualitative study was to describe the impact of COVID‐19 on emergency care providers' health and well‐being using personal perspectives. We conducted in‐depth interviews with emergency physicians, emergency medicine nurses, and emergency medical services providers at 10 collaborating sites across the United States between September 21, 2020, and October 26, 2020.

Methods

We developed a conceptual framework that described the relationship between the work environment and employee health. We used qualitative content analysis to evaluate our interview transcripts classified the domains, themes, and subthemes that emerged from the transcribed interviews.

Results

We interviewed 32 emergency HCWs. They described difficult working conditions, such as constrained physical space, inadequate personnel protective equipment, and care protocols that kept changing. Organizational leadership was largely viewed as unprepared, distant, and unsupportive of employees. Providers expressed high moral distress caused by ethically challenging situations, such as the perception of not being able to provide the normal standard of care and emotional support to patients and their families at all times, being responsible for too many sick patients, relying on inexperienced staff to treat infected patients, and caring for patients that put their own health and the health of their families at risk. Moral distress was commonly experienced by emergency HCWs, exacerbated by an unsupportive organizational environment.

Conclusions

Future preparedness efforts should include mechanisms to support frontline HCWs when faced with ethical challenges in addition to an adverse working environment caused by a pandemic such as COVID‐19.

INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 pandemic created a more hazardous and demanding work environment for health care workers (HCWs). 1 , 2 , 3 Many frontline providers have faced high exposure to the virus, increased working hours, and inadequate resources (e.g., personal protective equipment [PPE], personnel shortages, physical space constraints, insufficient infection control practices) for brief or long periods of time. 1 , 2 , 4 These adverse working conditions have led to excess mortality 5 , 6 , 7 as well as elevated rates of depression, anxiety, and job‐related stress, particularly among frontline emergency HCWs. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12

Studies that focused on health outcomes of emergency HCWs during the pandemic reported that a substantial proportion have screened positive for anxiety, 10 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 depression, 13 , 17 risk of posttraumatic stress disorder, 16 and burnout. 13 , 14 , 18 , 19 , 20 Most studies conducted to date relied on standardized surveys that include scales and questions with uniform response options that facilitate the quantification of outcomes and statistical comparison. 16 , 18 Many qualitative studies have focused on hospital‐based providers without specific focus on emergency medicine (EM) HCWs and have excluded emergency medical services (EMS) providers. 21 , 22 , 23

The purpose of this study was to describe the impact of COVID‐19 on emergency physicians (EPs), emergency medicine (EM) nurses, and EMS providers' health and well‐being using a qualitative approach that allowed us to document participants' reflections and experiences in their own words. We relied on semistructured interviews to identify important themes and patterns that emerged from the personal narratives of the emergency HCWs. These perspectives may not be obtained or well understood with the use of quantitative survey data alone.

METHODS

Study design

This investigation is the qualitative component of a mixed‐methods study aimed at evaluating the impact of COVID‐19 on the health of emergency HCWs. This paper reports the qualitative portion of the study. The project was a collaboration among 10 academic sites. We conducted in‐depth interviews with frontline HCWs between September 21, 2020, and October 26, 2020. The institutional review board (IRB) at the institution of the principal investigator (PI) served as the IRB of record and approved the study. We used the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research as a guide to reporting our results. 24

Theoretical framework

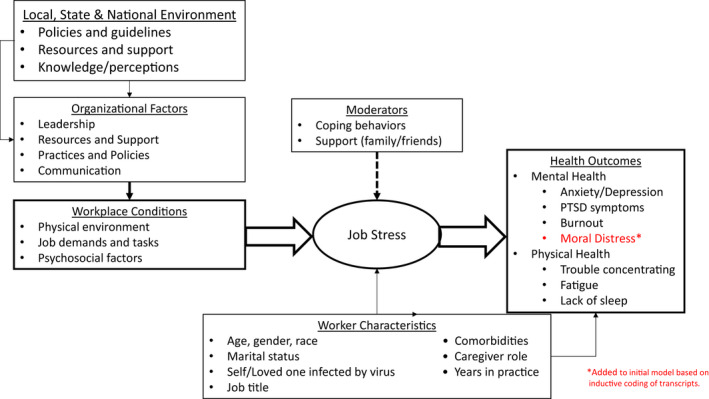

We developed a theoretical framework based on two existing occupational health models shown in Figure 1. 25 , 26 The first is an occupational safety and health promotion model developed by Sorensen and colleagues 25 that emphasizes the centrality of conditions of work as determinants of employee health and safety. This model focuses on the degree of integration between an organization's policies and practices related to occupational safety and health promotion.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework of relationship between working environment and health and well‐being

Adverse working conditions cause job‐related stress, which is not discussed in the Sorensen model but is well detailed in the psychosocial hazards of work model. 26 Job stress is the harmful physical and emotional responses that occur when the job requirements do not match the capabilities, resources, or needs of the worker. The psychosocial hazards of work model proposes that adverse working conditions such as work overload, unpredictable work hours, high uncertainty, and work–family conflicts negatively impact health directly or indirectly through the experience of job‐related stress. 26

Additionally, neither existing model includes potential moderators of the relationship between workplace conditions and worker health nor acknowledges the role of the external environment on the relationship between conditions of work and health. Our combined model posits that an individual's coping behaviors and personal support can moderate the relationship between working conditions and health. Our model recognizes that organizational characteristics and conditions of work are strongly influenced by the policies, resources, knowledge, and attitudes at the local, state, and national levels (see Figure 1).

Study setting and sample

We used purposive sampling to sample emergency providers affiliated with 1 of 10 academic sites. Sites were chosen to capture diverse geographic locations that varied in COVID‐19 transmission rates, clinical caseloads, and geographic location. An emergency physician collaborator at each site identified one EP, one EM nurse, and one EMS provider for an in‐depth interview. Our target sample size was one of each type of emergency HCW from each site for a total of 30 participants across the 10 sites. The goal was to achieve a sample in which we would be able to capture rich content with sufficient saturation of themes, without redundancy. 27 , 28

The EM collaborators provided the names and emails of potential participants to the co‐PIs (J.B., M.M.) who contacted them directly. If we were unable to contact the first HCW at the site, the site EM collaborator identified a second person for us to contact. Participants consented verbally prior to the interview, and we also sent them a copy of the consent form for their records. Collaborators were not involved in the interview process other than recruitment.

We developed an interview protocol based on existing models describing the relationship between job stress and health as well as studies that described stressors during prior pandemics, particularly SARS and MERS. 25 , 26 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 The interview guide is shown in Data S1.

We piloted our interview protocol with two emergency HCWs to test for content and clarity. We finalized our protocol based on the pilot interviews and then the co‐PIs (J.B. and M.M.) each conducted half of the 1:1 interviews using Zoom. The interviews lasted approximately 45–60 min. All interviews were recorded and professionally transcribed. Each participant received a $100 gift card upon completion.

The co‐PIs started each interview by obtaining participants' demographic information. Next, we asked participants open‐ended questions about the main components of our conceptual model including workplace conditions, stressors, mental and physical wellness, and moderators of stress, both at the workplace and at home. We used probing questions such as “can you give me an example of this” or “please tell me more about that” to obtain more detail about a theme of interest. Interviews continued until all preplanned questions had been asked and data saturation was achieved. At the end of the interview, we offered participants information about mental health resources as needed.

Data analysis

We coded our transcript data using qualitative content analysis. 33 , 34 , 35 An initial a priori codebook was developed deductively, based on our framework. 25 , 26 This was followed by an inductive process with a team consisting of a psychiatrist, health services researcher, and EP (J.G., M.M., and J.B.) who reviewed and independently coded three transcripts. We highlighted areas of text that mapped to our codebook and using open coding and noted additional themes and subthemes that emerged. 35

The process was iterative, with team members meeting after each transcript to discuss themes and subthemes, adjusting our codebook accordingly. Members of the coding team met to resolve areas of convergence until agreement across all themes and subthemes had been achieved to produce a final codebook.

After the codebook was finalized, two team members (J.B. and M.M.) coded additional transcripts in NVivo, version 12.0. The two coders used a standardized approach to mark segments that pertained to each theme and resolved disagreements by consensus after each transcript was analyzed. 35 The process was repeated on successive transcripts until a high inter‐rater reliability score (Kappa >0.9) was achieved. After this, J.B. coded all 32 transcripts (including the two pilot interviews) and M.M. reviewed and confirmed all codes.

We also used NVivo to classify the domains, themes, and subthemes across emergency HCW type. We summed the frequency of themes across individuals interviewed. We selected illustrative quotes to demonstrate these themes.

RESULTS

Of the 30 HCWs initially identified for participation, we completed an interview with 27. Two who were initially recruited did not respond to emails and one declined to participate. We replaced these three with a second HCW from the same site to reach our targeted sample size of 30. Those who completed interviews responded after an average of 1.5 attempts by email to reach them, with the majority responding after the first attempt. Because our codebook did not change after the pilot phase, we included our two pilot interviews. Table 1 displays the demographic characteristics of our 32 participants. The mean age was 36 years (range 25–58 years), and slightly more than half of the sample were male (53%). Almost three‐quarters of participants had been working as emergency HCWs for at least 5 years.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive characteristics of study sample (n = 32)

| Participant characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 25–30 | 8 | 25 |

| 31–40 | 17 | 53 |

| 40–58 | 7 | 22 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 22 | 69 |

| Black | 2 | 6 |

| Asian | 5 | 16 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 | 9 |

| Male gender | 17 | 53 |

| Profession | ||

| EM attending | 7 | 22 |

| EM resident | 5 | 16 |

| EM nurse | 10 | 31 |

| EMS provider | 10 | 31 |

| Years in practice | 9.2 (mean) | 6.8 (SD) |

| <5 | 9 | 28 |

| 5–10 | 13 | 41 |

| 11+ | 10 | 31 |

| Site | ||

| Providence, RI | 3 | 9 |

| New York City, NY | 3 | 9 |

| Atlanta, GA | 3 | 9 |

| Washington, DC | 3 | 9 |

| Los Angeles, CA | 4 | 13 |

| New Orleans, LA | 4 | 13 |

| Birmingham, AL | 3 | 9 |

| Omaha, NE | 3 | 9 |

| Dallas, TX | 3 | 9 |

| Detroit, MI | 3 | 9 |

Workplace conditions

Overall, participants described more difficult working conditions than previously experienced because of the physical environment (n = 26, 81%) and increased workload (n = 30, 94%; see Table 2). With the exception of prolonged use of masks, most participants reported that the availability of other types of PPE improved over the duration of the pandemic. Space was especially challenging at peak periods; many participants stated that it was difficult to physically separate patients under investigation for COVID‐19 from patients who presented with other medical problems. One attending stated, “Our entire department was just a virus pit.” In addition, prolonged boarding of patients in the emergency department was initially due to volume but later persisted when some hospitals required COVID‐19 test results prior to transfer to an inpatient unit.

TABLE 2.

Work environment and factors that affected it during COVID‐19

| Domain | Theme | Examples with illustrative quotes | Direction of comments (unique individual citings) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | ||

| Workplace conditions | Physical environment |

Inadequate spaceWe were holding 120 in our department. No one was going anywhere. (Attending) Inadequate SafetyWe've had a lot of exposures from trauma patients because we have this wide‐open trauma‐bay … We've actually had a lot of staff get sick from trauma exposure. (Nurse) Inadequate PPEWe had one N95 mask that was issued to us …It was about optics and making people feel safe, rather than actually keeping them safe. (Resident) |

Adequate SpaceI've done travel nursing. I've worked in a lot of hospitals, and we have rooms like doors and walls which I think is really big. (Nurse) Infection control procedures We'll usually just have one person make [screening] patient contact unless there's a safety issue… or will try to take the patient out of the house into open air. (EMS) Adequate PPEWe were asked to reuse N95 masks unless they were visibly soiled or you had a confirmed positive COVID patient, but other than that, we always had the equipment we needed. (EMS) |

|

|

| Workload |

CognitiveI got to a point where I just stopped checking my emails and trying to understand what the protocol was going to be and just show up to work and have someone tell me in person. (Resident) VolumeThe first couple months of COVID‐19 were bleak…They were inundated with volume, they had to have EMS providers come from across the state to help out. (EMS) Lost learning opportunitiesThe bread and butter of emergency medicine wasn't exactly what we were seeing… we missed out on a lot of that … (Resident) |

EfficiencyA lot of the meetings have moved to Zoom or some other form of distance meeting. It has changed me having to drive into work…That has been positive (EMS) |

|

||

| Psychosocial factors |

Lack of co‐worker supportIt seems like everybody's pretty crappy about this whole situation, honestly. It's hard to really lean on anybody, I'd say. (Attending) Low Work MoraleThe COVID attitude that everybody's adopted, whether it'd be freaking out about it or constantly talking about it or just being depressed about it. There's no escaping it. It's definitely not as fun to go in. (Nurse) |

Support of colleaguesI definitely feel like when I was working on shift with a lot of my colleagues, we just felt like we're in the trenches together and we really bonded. (Resident) My work colleagues have been absolutely the lifeline. (Attending) |

|

||

| Organizational factors | Leadership |

Lack of proactive leadershipOur department is very reactive. It's crazy until something hit the media. They really didn't react a whole lot and then all sudden, they're jumping on the news talking about, "Oh, we're going to do this, this and this." (EMS) Absence of leadershipI didn't see hospital administrators anywhere near the emergency department or any risky hot zone during the crisis. (Resident) |

Effective Leadership ActionsThey’ve put a lot of effort on contact tracing…They’re following all the guidelines, which is excellent. We've got enough PPE, they're taking good care of us…If you have symptoms, they're putting you off for 14‐day quarantine. (EMS) |

|

|

| Communication |

Lack of communicationSometimes even if it's bad news, having an open line of communication/transparency is really crucial… As long as information keeps flowing, you as an employee, always feel like, "Yes, they're working on it or they're doing it." When you don't hear for something for three days or four days or.. you would think they're not thinking about it. (EMS) Mixed messagingThe mixed messaging that we were getting from leadership about how to deal with it, how to deal with it ourselves if we get sick. When to report, when to get tested, those kind of things were kind of a big stressor for me early on. (Attending) |

Regular communicationOur CEO actually, does a Zoom forum that is available to everybody. They talk about all sorts of things… it brings in financial, our chief nursing officer, even…infectious disease. (Nurse) |

|

||

| Resources and support |

Inadequate staffingBecause we were always short‐staffed. It was two nurses per room in the COVID room, so it was like a total of 60. It actually went up to about close to 100 in one room, which is unheard of because the space is so limited. (Nurse) A lot of us came down with the COVID. Because half the workforce was out, that means the other half had to double up on the work. (EMS) |

Resource sharingAt the last second, we would get what we needed. I think they implemented some resource sharing among us throughout the system. (Nurse) |

|

||

|

Inadequate financial supportDoes the leadership appreciate us? They get us a meeting with the CMO, the CFO, and CEO and they said, "You're doing good work."… [We say] "We're doing good work. You're cutting our pay. (Attending) When we did get hazard pay, the doctors were really the ones that supported that, not the nurse managers. The [c‐suite administrator) who was a nurse….came through and was pointing at people in this very punitive way almost and he just says, "Remember that you chose this." (Nurse) Like when you were sick and had to go on quarantine, you just lost income. That was also very discouraging for people to admit that they were sick. I think it was really detrimental. (Attending) Inadequate ResourcesUncertainty about my own personal safety at work, while knowing that my family relies on me, and we don't really have a backup, or a safety net was really hard. (Resident) they just don't have funds for anything anymore. On top of COVID being hard, it's also, "Oh, now your residency doesn't have money to fund your training and education’ (Resident) Lack of appreciationYou just feel like you're almost being used, and no one really cares about what you're doing. (Resident) |

Appreciation of staff at all levelsI think at least our hospital does a really good job of recognizing those not only physicians, but I think they do a great job of recognizing all the people…whether that be a provider or a nurse or a caretaker, custodial staff, or really anybody that works in the healthcare field. (Resident) |

|

|||

| Mental health resources |

StigmaI'm a skeptic. I always feel I don't [need] any mental health…I'm always fearful of going to help because I don't think it's confidential. I think there's always a slip of the lip or something happens, or some insurance process goes through, or I feel like there's always something there that could really hurt me in the future. (EMS) Lack of TimeThe thought of coming up here to do some counseling thing or even get on another Zoom call when you have so many of them… To constantly be on conference calls and interviews and classes and stuff I just don't think anybody took them up on what they offered. (Nurse) |

AvailableWe do have, I can't remember if it's two or four free sessions with their counseling group there. They have come in and talk to our emergency department a couple of times. More of like a group setting, which I think is good. (Nurse) |

|

||

| External environment | Local and community support |

Contagion StigmaIt was this summer, we were at the pool… There was a couple there…They didn't have masks on …She asked what I did. I said, "I'm a firefighter." She got really uncomfortable, and they started to drift away. It wasn't 30 seconds and they're out of there. (EMS) As an Asian American, the amount of discrimination and hate crimes… there was times that either they refused aid and they would want to request another ambulance. (EMS) |

Lodging and food support The community did stuff. There's always food brought to the hospital. It was amazing. It was incredible. The fire departments circling outside with their lights and sirens. That was pretty cool. (Resident) |

|

|

| Public policy and adherence to guidelines |

News/Social mediaWatching the news, seeing them protest, "Why do we have to do this? It's not affecting us." I think if the public all came into the hot zones…and saw all the people dying and how sick they were, they probably would have taken the disease more seriously. (Nurse) Local Nonadherence to GuidelinesIt’s frustrating when you're at work and people come in and they're, I don't know, ignorant to the whole thing. Here I am and all these PPE and you come in and you don't have a mask and you're upset that I'm asking you to wear one. (Nurse) |

Local Adherence to GuidelinesI feel very fortunate to live somewhere where people just do what they're supposed to do… I feel grateful that I'm not somewhere where every step you take, there's someone who's breaking a rule and you have to confront it or leave the situation. (Attending) |

|

||

Almost all participants noted an increase in workload, not only because of patient volume but also due to the cognitive processing involved in caring for patients with a disease that was not well understood. One attending physician said, “Everything changed on a day‐to‐day basis, and then you were told you were doing things the right way. There was no right way.” Protocols frequently changed that required providers to spend excess time and effort making care decisions. Residents and younger trainees reported lost learning opportunities in the workplace setting. Their caseload was heavily skewed toward patients with COVID‐19, giving them much less exposure to typical medical emergencies.

The majority of participants had more positive comments than negative (n = 23, 72%) about the changes in the psychosocial culture of their working conditions (see Table 2). Even though COVID‐19 pervaded the work environment and led to low morale and work conflict at times, many participants reflected positively on the closer bonds and collegiality they felt with their fellow HCWs. One resident said, “It was teamwork. I felt like all of us were struggling, all of us knew what needed to be done, and we just got right at it.”

Organizational characteristics

Many participants were frustrated with their organization's response to COVID‐19 at the highest leadership levels (n = 25, 78%). They viewed leadership as reactive and focused on output rather than providing staff with appropriate resources and frequent communication (see Table 2). One resident stated, “It was honestly infuriating how poorly we were prepared for this.” Participants also felt that leadership was not transparent about budgetary cuts and protocol changes. One nurse described that “on one horrible Saturday with many sick, sick, patients … the CEO just came through and was pointing at people in this very punitive way almost and he just says, ‘Remember that you chose this’.” In general, the EMS providers were more positive about their employers' management of the COVID‐19 pandemic compared to the physicians and nurses.

Although few respondents reported that the organization provided them with hazard pay, lodging, or childcare assistance, almost all participants reported that there were mental health resources available to them at the workplace to support them. Some reported being reluctant to take advantage of the mental health resources because of time constraints, cost, or concerns that it would not remain confidential and could negatively affect their career. Consequently, only one participant reported taking advantage of mental health resources at their workplace. Instead, participants told us they relied on peer and/or family support to help them alleviate work stress.

External environment

The impact of the external environment on the health and well‐being of emergency HCWs was mixed. More than half of the participants appreciated the community support they received through the provision of food, housing, and public displays of gratitude (n = 20, 63%). On the other hand, some emergency HCWs experienced contagion stigma. For example, one Asian American provider noted contagion stigma in the form of racial bias, citing instances in which patients refused treatment because of stereotypical perceptions of disease risk. Participants voiced frustration with social media and news stories that presented misinformation and described how stressful it was to be working so hard to care of people who were not attempting to adhere to public health guidelines (n = 21, 66%). As one nurse put it, “People are coming to the hospital without a mask and you say, ‘Do you have a mask?’ ‘No.’ It's like, ‘Why not? It's October, have you been under a rock?’”

Stress and health

All participants described feelings of stress and poorer health as a result of COVID‐19 (see Table 3). We listened to many instances of moral distress, which is the psychological stress that individuals experience when they make decisions or perform tasks that deviate from their personal values and sense of identity due to institutional or other constraints. 38 , 39 Table 3 shows the moral distress participants described categorized by the underlying reason for the distress: (1) moral dilemma distress (i.e., difficulty choosing between two ethically appropriate options); (2) moral conflict distress (i.e., conflict over the most ethical course of action); (3) moral constraint distress (i.e., the circumstances constrain one from taking the most ethical course of action); (4) moral uncertainty distress (i.e., not sure about the right course of action); and (5) moral tension distress (i.e., unable to share one's beliefs with others). 36

TABLE 3.

Stressors and health outcomes reported by emergency care providers

| Factor type | Theme | Frequency | Subtheme | Quote |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress | Moral distress | 32 | Moral dilemma | There's been numerous occasions where I've spoken to colleagues where they said that they do not even want to go home because of the fear of bringing it back home, that they have actually stayed in their car overnight … (EMS) |

| Moral conflict | I know I've not had adequate PPE so I need to make sure that I'm limiting my exposure to everyone else. (Nurse) | |||

| Moral constraint | I was worried about that EMS wasn't reviving as many people in the field that they might typically revive. (Nurse) | |||

| I had an older woman … [The doctor] told me specifically to not pay attention to her, move my focus from her to somebody else who wasn't in the same situation. (Nurse) | ||||

| Moral uncertainty | It was horrible. There was a woman … who … ended up being intubated … She wasn't that old, and she was thriving in the community beforehand, and managing her end of life decisions with her daughters who were [out of state], and wanted to be at her bedside, and trying to Zoom them in or Skype … It was this horrible thing to have to deal with where they are trying to say goodbye to a human being … and have her open her eyes and intermittently indicate she did not want the breathing tube to come out over Zoom to her children. It was just a terrible thing that no one should have to go through. (Resident) | |||

| Moral tension | When I came home and there's nothing really to talk about because sometimes the less your family knows, the better. You do not necessarily want them to know what kind of demons you are having. (EMS) | |||

| Health outcomes | Mental health | 22 | Anxiety |

Being anxious is one of the things I've felt. I have not felt any depression. Just being anxious at work a lot of the time. (Nurse) For me, it's a worry thing. Where if you do 10 calls in a day, maybe one would bother you … With this one, you do 10 calls, you are concerned about 10 calls. (EMS) |

| Depression |

I feel like I was way more depressed. I felt less motivated to do things that would make me feel better. I'm not supposed to be burnt out yet, but it definitely makes you think long term like, “If this is how they treat healthcare providers during a pandemic, how long do I really want to stay in this if I'm not being valued the way that I deserve to be valued? (Resident) I also would feel very sad all the time, depressed, and cry a lot and come home and think about my patients and the ones that ended up getting very sick and passing away during my shift. (Nurse) |

|||

| Burnout |

At the end of your 10‐h shift or whatever, I feel more emotionally exhausted and less confident in my ability to provide compassionate care. I hate to say that out loud because that really makes me sound like an awful evil person, but I'm just trying to be a little real. (Attending) I emotionally and cognitively cannot contribute when I'm home. I just cannot do it. (Resident) |

|||

| PTSD | My own personal safety. I had a lot of dreams and nightmares that I got COVID, and I died, like the patients I saw die alone in the hospital. (Resident) | |||

| Physical health | 15 | Fatigue |

Yes, fatigue was a big thing, and it was like even when I did get enough sleep, I still just felt wrecked. (Resident) I feel very tired all the time. From all the running around, even just the physical work. I would come home and just have no energy to do anything more in terms of my own home and upkeep and my children. (Nurse) |

|

| Sleep deprivation |

The sleeping was reliving everything every night. It still felt like I was going to work every night. (Attending) I had a very hard time sleeping… I could not get all these thoughts out of my head. It was just constant thinking about everything. (Nurse) |

|||

| Trouble concentrating | I definitely had trouble concentrating. A classic thing will be me saying to my children like, “Wait, just say it again. I'm paying attention. Wait, just say it again. Just say it again.” (Attending) |

Every participant we interviewed who lived with someone was worried about infecting their loved ones at home with COVID‐19, especially if they lived with elderly or young family members (moral dilemma distress). There was a perception that exposure at work, especially when there was not adequate PPE, resulted in increased family risk. Many described the extra measures they took to decontaminate themselves when they returned home to avoid transmission to family.

Participants often voiced moral distress because they felt that they were constrained from providing conventional care. Reuse of PPE and deviation from routine approaches to patient care (moral constraint) and inability to involve families in treatment decisions (moral uncertainty) were raised frequently by participants. Providers noted that they often felt powerless in expressing their concerns to leadership or others within their circle, such as family and friends (moral tension). One attending described the moral conflict that weighed on her and many of her colleagues: “Mentally the biggest challenge for me was seeing this thing and not being able to know what to do and not knowing if the choices we made, especially at the beginning, were the right choices.”

The pandemic took a toll on the health and well‐being of emergency HCWs in many different ways (see Table 3). Many participants noted feelings of anxiety related to the changing information about the disease and concern for family transmission. They described feeling sad when telling families they could not see their loved one and hopeless when patients died alone. Participants reported symptoms of depression, emotional exhaustion, and burnout from not knowing how best to care for patients, the unpredictability of patients' trajectories, and the many deaths that occurred to young and old alike. One resident stated, “I felt just so drained.”

Moderators of stress

Home support helped lessen stress, especially when other family members were in the medical field (n = 16, 50%). However, broader support outside of the immediate family was not a given (Table 4). One resident said, “My family doesn't really understand, and they would just freak out.” Many participants described family members that did not live with them who were reluctant or refused to see them because they feared contracting the virus from them. Participants who lived alone or far from family members described isolation, which was exacerbated by the restriction of normal social outlets during the pandemic (n = 19, 60%).

TABLE 4.

Moderators of stress

| Examples with illustrative quotes | Direction of moderation (unique individual citings) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderator | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive |

| Family and friends |

Isolation I live by myself … I'm not from [my work city], I do not know a single person here outside of my residency, so if I cannot hang out with my friends in residency, I have no one, no one here. That has been hard. (Resident) Lack of family support Feeling alone, and even more so just because our family is almost punishing us for doing this, is what it feels like. (Nurse ID11) |

Family/personal relationship support I think one of the things that helps with that as well is that [my wife] is also in health care … she very much understands the precautions have to be taken, the stressors herself, and so that is a great benefit. (EMS) They're always checking up on me … my family is very tight. We're always checking up on each other and I've called them many times crying and sobbing. It's always just a relief to have someone to talk to including my husband. (Nurse) |

|

|

| Coping mechanisms |

Overeating I'm definitely an eat your feelings kind of girl. I will eat brownies or just whatever is unhealthy that gives me that one second of satisfaction, that's definitely an unhealthy coping mechanism for me. (Nurse) Alcohol I got sauced up. I definitely drank heavily for more than I normally would for probably about 4 weeks. (Attending) Many restrictions I think that my well‐being is not good for many reasons. One is like work is hard. Two is there's nothing on the outside of work that is really rejuvenating … How do you stay well in a time of stress when there's nothing else to do? (Attending) |

Adaptive coping Being more involved and engaged to try to fix a problem, put some sense of control back in my hand. (Attending) Exercise I got to run a ton. If I did not have that, I do not know what would have happened. I still worked out every day and that was huge. I cannot imagine … not being able to go outside. That's what I did to keep it together. (Attending) Hobbies In terms of stress relief, I just really like to cook. (Nurse) Meditate, yoga, breathing exercises, I go hiking and I go walking both with my dogs as often as I can. (EMS) |

|

|

Participants tended to report more positive coping mechanisms (n = 29, 91%) than negative ones (n = 13, 41%). Many noted spending time with family, exercising, hobbies, meditating, and getting pets as sources of positive coping. Some also noted various adaptive coping strategies they used during the pandemic such as coming up with creative ways to address limitations at work and home. While some did discuss negative coping strategies, such as increased alcohol use and overeating, these were generally not described as problematic or being associated with longtime use.

DISCUSSION

This is the first qualitative investigation of the impact of the work environment on the health and well‐being that included EM providers across multiple roles (EPs, EM nurses, and EMS providers) and at diverse sites providers during COVID‐19. Emergency HCWs experienced many instances of moral distress, anxiety, depression, and exhaustion during the pandemic. In a work environment that was more hazardous and cognitively taxing compared to baseline, many felt that their organization did not adequately protect and support employees' health, well‐being, and safety. They commonly criticized organizational leadership, citing inconsistent communication, lack of presence, and insufficient guidance on handling the problems that arose. Disinformation by social media and nonadherence to public health guidelines exacerbated their job stress. Although mental health resources were usually available at work, emergency HCWs relied largely on their immediate colleagues and family, exercise, and hobbies for emotional support and stress relief.

Consistent with previous studies of COVID‐19, our participants reported that COVID‐19 caused them to feel more anxiety, depression, and burnout. 14 , 16 , 18 , 19 Studies have described the anxiety emergency HCWs felt when faced with the dilemma of spreading the virus to their loved ones at home. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 36 , 36 , 37 One of the unexpected findings to emerge from this qualitative investigation was how common emergency HCWs experienced moral distress. As a result, we revised our theoretical framework to add moral distress as one of the mental health outcomes (see Figure 1). Since the pandemic, there has been greater focus on the prevalence of moral distress and moral injury in HCWs. 36 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 A recent study described the common experiences of moral injury among HCWs across disciplines during the pandemic; however, it did not focus specifically on emergency providers and did not include the EMS population. 23 Few studies have focused specifically on the high levels of moral distress experienced by emergency HCWs due to ethically challenging issues such as rationing care, relying on inexperienced personnel, and not providing the emotional support to patients and families that they normally would. 45 , 46 , 47 , 48

Many COVID‐19 studies have recommended providing more workplace mental health resources to reduce the negative health consequences experienced by HCWs during the pandemic. More recently, the United States Congress passed The Lorna Breen Act, named after an EP who died by suicide during the pandemic, which is intended to address behavioral health needs in frontline workers. 49 This is indeed an important step, but our results suggest that frontline emergency HCWs would have also benefited from better organizational leadership and support. 14 , 39 , 48

A bigger issue is that the U.S. health system, like that of many other countries, was not prepared at the national, state, or local level to effectively respond to a virus with high transmissibility and severity.53 It took most hospitals and health care delivery systems too long to adequately protect frontline HCWs, to develop a strategy to allocate health care resources in a rational, ethical, and organized way and to mount a coordinated response. Consequently, there was a tremendous toll on the health and well‐being of frontline HCWs. Pandemic preparedness must be a global security priority, and taking the necessary steps to organize and invest accordingly will prevent this disaster from overwhelming health systems in the future. 50

LIMITATIONS

The results of our study must be interpreted in the context of the following limitations. Participants were interviewed at different points in time in relationship to the peak of the pandemic at their respective sites and there may have been some recall bias. We interviewed individuals recruited by the site PI and therefore there may have been some selection bias. We may not have captured a representative sample of EPs, EM nurses, and EMS providers and may have interviewed individuals with fewer or more grievances than the general population of frontline HCWs. Individuals may also have been less likely to report negative behaviors during the interview. We interviewed providers from select institutions. Although some physicians and nurses worked at community‐based hospitals, these sites were affiliated with academic centers and therefore may have caused other potential biases. We also collected limited data and therefore do not present detailed demographics, such as marital status or caretaker responsibilities, which may have affected perspectives.

We did not use scales to measure any of our mental health outcomes, but instead relied on providers' personal narratives to identify common themes using qualitative research methods. Therefore, we describe participants' feelings and symptoms, not experiences of disease. We also did not measure or describe the general public health climate that may have impacted provider opinions. Our conceptual model has not been previously validated, although it is based on two existing, validated worker health models. In addition, we restricted interviews to EPs, EM nurses, and EMS providers. We did not interview other EM staff who may have been similarly impacted by coping mechanisms during the pandemic, such as advanced practice providers and security and environmental services staff. Finally, the generalizability may be limited, since we do not know whether the race or gender distribution of our sample represents the overall population of providers at our sites. Generalizability may have also been limited since our study captured reflections during the early part of the pandemic.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this qualitative investigation revealed substantial moral distress among frontline emergency care providers that has been largely under reported during COVID‐19. COVID‐19 revealed underlying deficiencies in preparedness that will need to be addressed if we are to maintain a healthy and productive healthcare workforce during future pandemics.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Janice Blanchard and Melissa McCarthy were involved in all stages of the study including securing of funding, conception of the study, data collection, analysis, and composition of the manuscript. Yixuan Li was involved in the data collection, analysis, and composition of the manuscript. Anne M. Messman, Suzanne K. Bentley, Michelle D. Lall, Yiju Teresa Liu, Rory Merritt‐Recchia, Randy Sorge, Christopher Greene, Jordan M. Warchol, and Deborah B. Diercks were involved in survey development, recruitment, and composition of the manuscript. James Griffith and Rory Merritt‐Recchia contributed to survey development and composition of the manuscript.

Supporting information

Data S1

Blanchard J, Messman AM, Bentley SK, et al. In their own words: Experiences of emergency health care workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Acad Emerg Med. 2022;29:974‐986. doi: 10.1111/acem.14490

Supervising Editor: Dr. Jody Vogel

REFERENCES

- 1. Mhango M, Dzobo M, Chitungo I, Dzinamarira T. COVID‐19 risk factors among health workers: a rapid review. Saf Health Work. 2020;11(3):262‐265. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2020.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Calò F, Russo A, Camaioni C, De Pascalis S, Coppola N. Burden, risk assessment, surveillance and management of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in health workers: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):139. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00756-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO . COVID 19: occupational health and safety for health workers: interim guidance 2 February 2021. World Health Organization; 2021. 2021. Accessed March 1, 2022. http://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO‐2019‐nCoVoHCW‐advice‐2021.1.

- 4. Mehta UM, Venkatasubramanian G, Chandra PS. The "mind" behind the "mask": assessing mental states and creating therapeutic alliance amidst COVID‐19. Schizophr Res. 2020;222:503‐504. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.05.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reynolds KA. Coronavirus: at least 7,000 healthcare workers have died globally. Medical Economics. Accessed March 1, 2022. https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/coronavirus‐at‐least‐7‐000‐healthcare‐workers‐have‐died‐globally2020

- 6. Spencer J. 12 months of trauma: more than 3,600 US health workers died in covid's first year. Kaiser Family Foundation. April 8, 2021. Accessed March 1, 2022. https://khn.org/news/article/us‐health‐workers‐deaths‐covid‐lost‐on‐the‐frontline/.

- 7. Joseph A. WHO estimate: 115,000 health workers have died from Covid‐19, as calls for vaccine access grow. STAT. October 21, 2021. Accessed March 1, 2022. https://www.statnews.com/2021/10/21/who‐estimate‐115000‐health‐workers‐have‐died‐from‐covid‐19‐as‐calls‐for‐vaccine‐access‐grow/

- 8. Pappa S, Athanasiou N, Sakkas N, et al. From recession to depression? Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, traumatic stress and burnout in healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Greece: a multi‐center, cross‐sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5):2390. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chu E, Lee KM, Stotts R, et al. Hospital‐based health care worker perceptions of personal risk related to COVID‐19. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(Suppl):S103‐S112. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.S1.200343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F, et al. Mental health outcomes among frontline and second‐line health care workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) Pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e2010185. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kang L, Li Y, Hu S, et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(3):e14. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30047-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wright HM, Griffin BJ, Shoji K, et al. Pandemic‐related mental health risk among front line personnel. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;137:673‐680. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.10.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kelker H, Yoder K, Musey P, et al. Longitudinal prospective study of emergency medicine provider wellness across ten academic and community hospitals during the initial surge of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Res Sq 2020. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-87786/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu Q, Luo D, Haase JE, et al. The experiences of health‐care providers during the COVID‐19 crisis in China: a qualitative study Lancet Glob Health 2020;8(6):e790‐e798. (in Eng). 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30204-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rodriguez RM, Montoy JCC, Hoth KF, et al. Symptoms of anxiety, burnout, and PTSD and the mitigation effect of serologic testing in emergency department personnel during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;78(1):35‐43.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.01.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu Y, Long Y, Cheng Y, et al. Psychological impact of the COVID‐19 outbreak on nurses in China: a nationwide survey during the outbreak. Front Psych. 2020;11:598712. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.598712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rodriguez RM, Medak AJ, Baumann BM, et al. Academic emergency medicine physicians' anxiety levels, stressors, and potential stress mitigation measures during the acceleration phase of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(8):700‐707. doi: 10.1111/acem.14065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chor WPD, Ng WM, Cheng L, et al. Burnout amongst emergency healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A multi‐center study. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;46:700‐702. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.10.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baumann BM, Cooper RJ, Medak AJ, et al. Emergency physician stressors, concerns, and behavioral changes during COVID‐19: a longitudinal study. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(3):314‐324. doi: 10.1111/acem.14219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Warren J, Plunkett E, Rudge J, et al. Trainee doctors' experiences of learning and well‐being while working in intensive care during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a qualitative study using appreciative inquiry. BMJ Open. 2021;11(5):e049437. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bennett P, Noble S, Johnston S, Jones D, Hunter R. COVID‐19 confessions: a qualitative exploration of healthcare workers experiences of working with COVID‐19. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e043949. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Song YK, Mantri S, Lawson JM, Berger EJ, Koenig HG. Morally injurious experiences and emotions of health care professionals during the COVID‐19 pandemic before vaccine availability. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(11):e2136150. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.36150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245‐1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sorensen G, McLellan DL, Sabbath EL, et al. Integrating worksite health protection and health promotion: a conceptual model for intervention and research. Prev Med. 2016;91:188‐196. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leka S. Health impact of psychosocial hazards of work: an overview. World Health Organization. 2010. Accessed March 1, 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44428

- 27. Vasileiou K, Barnett J, Thorpe S, Young T. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview‐based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15‐year period. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):148. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. 4th ed. Sage Publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Rourke S, et al. Factors associated with the psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on nurses and other hospital workers in Toronto. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(6):938‐942. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000145673.84698.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Balderson KE, et al. Long‐term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(12):1924‐1932. doi: 10.3201/eid1212.060584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Magnavita N, Chirico F, Garbarino S, Bragazzi NL, Santacroce E, Zaffina S. SARS/MERS/SARS‐CoV‐2 outbreaks and burnout syndrome among healthcare workers. An umbrella systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(8):4361. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18084361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kisely S, Warren N, McMahon L, Dalais C, Henry I, Siskind D. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review and meta‐analysis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1642. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277‐1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moretti F, van Vliet L, Bensing J, et al. A standardized approach to qualitative content analysis of focus group discussions from different countries. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(3):420‐428. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 3rd ed. Sage Publishing; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Morley G, Sese D, Rajendram P, Horsburgh CC. Addressing caregiver moral distress during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Cleve Clin J Med. 2020. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.87a.ccc047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nie A, Su X, Zhang S, Guan W, Li J. Psychological impact of COVID‐19 outbreak on frontline nurses: a cross‐sectional survey study. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(21–22):4217‐4226. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dean W, Talbot SG, Caplan A. Clarifying the language of clinician distress. JAMA. 2020;323(10):923‐924. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.21576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400‐402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shanafelt TD, Wang H, Leonard M, et al. Assessment of the association of leadership behaviors of supervising physicians with personal‐organizational values alignment among staff physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2035622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2133‐2134. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Campbell LA, LaFreniere JR, Almekdash MH, et al. Assessing civility at an academic health science center: Implications for employee satisfaction and well‐being. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0247715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Norman SB, Feingold JH, Kaye‐Kauderer H, et al. Moral distress in frontline healthcare workers in the initial epicenter of the COVID‐19 pandemic in the United States: relationship to PTSD symptoms, burnout, and psychosocial functioning. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38:1007‐1017. doi: 10.1002/da.23205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Giwa A, Crutchfield D, Fletcher D, et al. Addressing moral injury in emergency medicine J Emerg Med;61(6):782‐788. 2021. (in Eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.07.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rimmer A. Covid‐19: eight in 10 doctors have experienced moral distress during pandemic BMA survey finds. BMJ. 2021;373:n1543. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zalesky CC, Dreyfus N, Davis J, Kreitzer N. Emergency physician work environments during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;77(2):274‐277. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hesselink G, Straten L, Gallée L, et al. Holding the frontline: a cross‐sectional survey of emergency department staff well‐being and psychological distress in the course of the COVID‐19 outbreak. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):525. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06555-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rosenbaum L. Facing Covid‐19 in Italy – ethics, logistics, and therapeutics on the epidemic's front line. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1873‐1875. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Firew T, Sano ED, Lee JW, et al. Protecting the front line: a cross‐sectional survey analysis of the occupational factors contributing to healthcare workers' infection and psychological distress during the COVID‐19 pandemic in the USA. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e042752. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Senate passes AHA‐supported Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act. American Hospital Association. February 28, 2022. Accessed March 2, 2022. https://www.aha.org/news/headline/2022‐02‐18‐senate‐passes‐aha‐supported‐dr‐lorna‐breen‐health‐care‐provider‐protection

- 50. Improving pandemic preparedness: lessons from COVID‐19. Independent Task Force Report No. 78. Council on Foreign Relations. 2020. Accessed March 1, 2022. https://www.cfr.org/report/pandemic‐preparedness‐lessons‐COVID‐19/pdf/TFR_Pandemic_Preparedness.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1