Abstract

Aims

To explore (1) the context in which nursing executives were working, (2) nursing's contribution to the healthcare response and (3) the impact from delivering healthcare in response to the pandemic.

Design

Retrospective, constructivist qualitative study.

Methods

Individual interviews using a semi‐structured interview guide were conducted between 12 February and 29 March 2021. Participants were purposively sampled from the Victorian Metropolitan Executive Directors of Nursing and Midwifery Group, based in Melbourne, Victoria the epi‐centre of COVID‐19 in Australia during 2020. All members were invited; 14/16 executive‐level nurse leaders were participated. Individual interviews were recorded with participant consent, transcribed and analysed using thematic analysis.

Results

Four inter‐related themes (with sub‐themes) were identified: (1) rapid, relentless action required (preparation insufficient, extensive information and communication flow, expanded working relationships, constant change, organizational barriers removed); (2) multi‐faceted contribution (leadership activities, flexible work approach, knowledge development and dissemination, new models of care, workforce numbers); (3) unintended consequences (negative experiences, mix of emotions, difficult conditions, negative outcomes for executives and workforce) and (4) silver linings (expanded ways of working, new opportunities, strengthened clinical practice, deepened working relationships).

Conclusion

Responding to the COIVD‐19 health crisis required substantial effort, but historical and industrial limits on nursing practice were removed. With minimal information and constantly changing circumstances, nursing executives spearheaded change with leadership skills including a flexible approach, courageous decision‐making and taking calculated risks. Opportunities for innovative work practices were taken, with nursing leading policy development and delivery of care models in new and established healthcare settings, supporting patient and staff safety.

Impact

Nursing comprises the majority of the healthcare workforce, placing executive nurse leaders in a key role for healthcare responses to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Nursing's contribution was multi‐faceted, and advantages gained for nursing practice must be maintained and leveraged. Recommendations for how nursing can contribute to current and future widespread health emergencies are provided.

Keywords: COVID‐19, nurses' role, nursing, nursing models, qualitative research

1. INTRODUCTION

With over 230 million cases and almost 5 million deaths worldwide (as at 4 October 2021), the COVID‐19 pandemic has presented a significant challenge to healthcare systems, with substantial risks for the healthcare workforce (Nguyen et al., 2020; Quigley et al., 2021). For example, in the first 6 months of the pandemic, results indicated that Australian healthcare workers were more than 2.5 times more likely to contract COVID‐19 than community members (Quigley et al., 2021). There are almost 28 million nursing personnel globally (World Health Organization, 2020), comprising the largest proportion of the health workforce (59%), with nurses likely the first clinical contact for those presenting to health services (World Health Organization, 2020) and making up to 90% of patient/clinician contacts (Crisp et al., 2018). As such, the nursing workforce is critical to the healthcare system response (Halcomb et al., 2020), placing executive nurse leaders in a key role responding to the pandemic. However, little is known about their experiences during COVID‐19 (Hølge‐Hazelton et al., 2021).

1.1. Background

In Australia, initial modelling, Government responses and recommendations focused on nurse staffing numbers for intensive care unit (ICU) beds (Australian Government, 23 March 2020; Litton et al., 2020; Marshall et al., 2020). For example, initial estimates indicated a 269% increase in registered ICU nurses could be required (Litton et al., 2020) and a call for former ICU nurses was made (Australian Government, 23 March 2020). However, nurse leaders played a critical role during the previous coronavirus outbreaks with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) crisis, demonstrating significant crisis management expertise (e.g. Tseng et al., 2005). An early exploration (April 2020) of public health nursing staff needs during COVID‐19 illustrated the broad impact on nursing activities (Halcomb et al., 2020). Survey results from 637 Australian‐based public health nurses employed in various settings (e.g. general practice, community health, schools/universities, Aboriginal health services, etc.) identified seven key areas where support was required. Key areas included access to personal protective equipment (PPE), communication (e.g. protocolized care, delivery of information, professional education), service funding (e.g. nurse telehealth, nurse billing) and industrial issues (e.g. job security, leave, etc) (Halcomb et al., 2020).

Meeting these diverse needs in challenging and stressful circumstances, and the reliance on nursing to deliver care, requires substantial management. Some early investigations into nurse leaders' experiences are available from the United States of America (USA) (Aquilia et al., 2020; Joslin & Joslin, 2020). For example, nurse leaders (n = 1824) completed an online survey in July 2020 with the top challenges for addressing COVID‐19 identified. These included managing with no established procedures, surge workforce required, staff well‐being concerns and access to equipment including PPE (Joslin & Joslin, 2020). Leaders from a range of different settings were included, and results were combined across leadership roles; that is, Chief Nursing Officer/Executive (approximately 20% of sample) alongside Directors and Managers. This quantitative approach precluded a nuanced understanding of their experience. Another article (sample size and timing not reported) presented a qualitative narrative on nurse leaders' experiences, reporting on some of their contributions and challenges during COVID‐19 (Aquilia et al., 2020). The authors highlighted the significance of decision‐making and adapting with limited information and changing circumstances, alongside the importance of staff well‐being and ensuring high‐quality patient and family experiences.

These results illustrate the breadth of nursing's role, beyond the initial expected focus of providing staffing for ICU wards. While providing some initial insights into nurse leaders' experiences from early in the pandemic, detailed research methodologies were not presented and participants reflected broad nursing management roles. A rigorous qualitative research design using individual interviews with nurse executives is needed to provide a robust understanding of the most senior nurse hospital leaders' experiences responding to the pandemic. This information will provide important insights to those responsible for preparing for or managing in similar circumstances.

2. THE STUDY

2.1. Aims

The aim of the current study was to understand the nursing response to the COVID‐19 pandemic in Melbourne, Australia from the perspective of nursing executives. Specifically, we will explore (1) the context in which nursing executives were working, (2) nursing's contribution to the healthcare response and (3) the impact from delivering healthcare services in response to the pandemic.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Design

We used a qualitative, retrospective research design, with a constructivist approach. In‐depth individual interviews were conducted using a semi‐structured interview guide.

2.2.2. Context

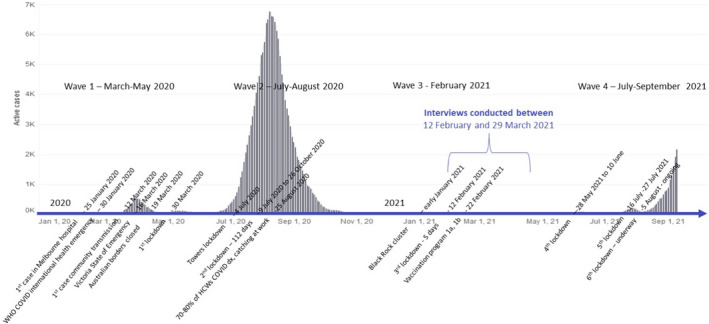

During 2020, Victoria became the epi‐centre of COVID‐19 with 73% (20,345/27,923) of Australia's COVID cases, 88% (19,360/22,092) of locally acquired cases, and 90% (820/908) of COVID deaths (2 December 2020) (Australian Government Department of Health, 2020). Victoria was declared a State of Emergency (16 March 2020) with two main waves and associated lockdowns experienced (see Figure 1 for timeline). Health services within Victoria are Government funded and function independently of one another. Melbourne is the capital city of the south‐eastern state of Victoria, Australia; the greater Melbourne area has an estimated resident population of 5.2 million (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2021), covering a geographical area of almost 10,000 square kilometres.

FIGURE 1.

Timeline of key dates for COVID‐19 in Victoria for nursing/midwifery addressing COVID‐19 pandemic, overlaid with active cases. Active cases 9 September 2021 via https://www.coronavirus.vic.gov.au/victorian‐coronavirus‐covid‐19‐data

The project was initiated by the Victorian Metro Public Health Nursing and Midwifery Executive Group, with an independent social sciences researcher (K.B.). The Executive Directors of Nursing and Midwifery (metro EDONM) group are a well‐established, professional leadership group for the Melbourne metropolitan nursing and midwifery workforce. The group provides the mechanism for shared learning, problem solving, lobbying to Department of Health (and others), framing and progressing collective projects and forming agreed positions on industrial matters relevant to acute hospital, community and public health nursing practice. The group typically meets monthly, although the focus and frequency changed during the heightened period of COVID‐19.

2.2.3. Participants

Purposive sampling targeted the members of the metro EDONM group. Members are the executive leads of nursing and/or midwifery (e.g. titles include Chief Nursing/Midwifery Officer or Executive Director) across 15 large, public health services within metropolitan Melbourne. In all, 16 personalized invitation letters and a research project Participant Information and Consent Form were sent via email by KB to each member of the group (1 February 2020), with two follow‐up reminders sent.

2.2.4. Data collection

One researcher (K.B.; female, BBSci [Hons, psychology], PhD, experienced in qualitative research methods) conducted individual, in‐depth, semi‐structured interviews remotely via Zoom. The interview guide (Box 1) included open‐ended questions and prompts if needed (probes such as ‘tell me more about that’ were also used) covering three key areas: ascertaining the contribution of nursing to the response (e.g. system‐, organizational‐ or individual‐level contributions), the resources required for the associated changes (e.g. staffing, PPE, supplies) and the impact on nursing (e.g. new standards of practice, varying models of care, workforce). Participants were also asked about ongoing concerns and any benefits identified from the nursing practice response or pandemic. Two pilot interviews were undertaken to test content and timing. Interviews were recorded with participant consent, transcribed verbatim and anonymised.

BOX 1. Interview guide.

1.

Introduction

- Thank participant/s for their time. Confirm that participant has read information sheet and consent form. Confirm it is OK to record interview/focus group. If yes, indicate when pressing record. Advise that:

-

aparticipant can stop at any time, reconvene later or not; whatever suits best

-

ba list of questions to pose and when reported, all responses will be anonymous and confidential

-

cindividual statements will be attributed to EDON plus participant number (e.g. EDON 1)

-

a

Can view transcript at conclusion and delete anything do not wish to have included

Any questions before getting started?

Overview of interview—wanting to capture key aspects about how nursing practice responded to COVID‐19 last year

Participant details

-

d

Participant details

-

a

What is your role?

-

b

How long have you been working in nursing?

-

c

Did you/your hospital have a unique role in addressing COVID?

-

d

How did your role change to address the pandemic?

Note: Questions were not posed in this specific order below, but were drawn on as relevant to maintain a flowing conversation and engagement between interviewer and interviewee.

Nursing contribution to addressing the pandemic

-

e

Because of COVID‐19, describe any nursing practice changes or adjustments in the model of care adjustments made within hospital, with specific examples

Prompts- how prepared was your area/hospital/nursing group for the pandemic?

- what was response of hospital/nursing?—when and why did these changes happen, how did it happen?

- impact on in‐hospital (e.g. delivering bedside care) or outside of hospital?

-

f

What was the contribution made by nursing practice from these changes?

Prompts

-

a

system‐, organizational‐ or individual‐level capacity

-

b

specialist skills, knowledge, experience, education, training

-

c

role in multi‐disciplinary clinical/governance teams, supply chains, information/communication flow

-

d

what was innovative for practice?

Resources required

-

e

What resources were needed to support these changes, to build capacity?

Prompts

-

a

Consider policy, resources, workforce, communication, environment

-

b

What enablers were put in place for these changes to take place?

-

c

What barriers were removed for these changes to take place?

Prompts for both

-

a

Formal or informal processes? How were these resources sourced?

-

b

Working with others?

Impact of nursing contribution

-

c

Are any of these identified changes still in place? Are they considered interim or permanent?

-

d

Can you describe the impact of addressing COVID on nursing practice?

Prompts-

aProfessional autonomy; status, profile; scope of practice; staff retention

-

bWorkspace

-

cExperiences, for example, physical, including personnel testing positive for COVID‐19 or emotional, including for personnel working outside usual setting

-

a

Final reflections

-

dAre there any current concerns associated with the pandemic?

-

aWhat is your greatest concern currently about the pandemic?

-

a

-

e

What would you want someone in your position know when addressing the pandemic? For example, someone in another state of Australia preparing for an outbreak?

-

f

Were there any beneficial outcomes from addressing the pandemic?

-

g

What is your/nursing proudest achievement from addressing the pandemic?

Conclude

-

b

Is there anything else you would like to add?

-

c

Wrap up

Would you like to receive a copy of the transcript for review prior to analysis?

-

All quotes will be deidentified; that is, attributed to, for example, EDON 1, and personal details (e.g. years of experience) used only when not able to be identified

Thank you very much for time and input. Will be helpful to understand current and future aspects of addressing pandemic from nursing perspective.

2.2.5. Data analysis

Reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2012, 2019, 2021) was conducted inductively (no a priori framework) by one researcher (K.B.). Analysis was undertaken through six consecutive stages: stage 1 required data familiarization through iterative reading of transcripts, in stage 2 initial categories were identified through coding from line‐by‐line analysis and stage 3 was grouping categories, including hierarchical relationships between codes. Stage 4 was identifying and refining key themes and sub‐themes, with stage 5 involving defining and naming of themes. Stage 6 included review and endorsement by all authors during write‐up. NVivo (v12) software was used for stages 1–3, and a virtual whiteboard (www.miro.com) for stages 4–5 to facilitate analysis.

2.2.6. Rigour of constructivist approach and researcher reflexivity

The interviewer had no previous relationships with participants, but was experienced in conducting qualitative and quantitative research with healthcare clinicians across multiple health services. Members of the group reviewed the protocol, including the interview guide, prior to ethics submission and invitations to participate. Participants were advised of the researcher's non‐nursing background but experience in multi‐disciplinary health services research to support open dialogue. Participant review of transcripts was available prior to analysis. No changes were made, with no incentives to participants offered. In line with a reflexive thematic approach (Braun & Clarke, 2019, 2021), analysis was undertaken by one researcher, with review of analytical process and initial theme‐level results probed by an experienced, senior qualitative researcher (E.M.; Professor of Nursing, nursing practice and research, not in the group). Members of the metro EDONM group, including research participants (i.e. member checking), reviewed initial and final versions of the results and manuscript. Members as participants and co‐authors supported a constructivist approach, addressing possible bias of social desirability. Participants' grammar‐corrected illustrative quotes are provided for transparency. Results are presented in accordance with the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007).

3. FINDINGS

3.1. Participants

There were 14 individual interviews (88% response rate) conducted between 12 February and 29 March 2021 (Figure 1), taking an average of 65 minutes each. Participants were from general and specialist hospitals, with a mix of elective and non‐elective work, and with new personnel in senior executive roles and large, non‐COVID‐related projects underway. Active COVID‐19 cases within health services (presence, frequency) varied across participants. Participants held the most senior role in nursing in their health service, with role titles such as Chief Nursing Officer, Chief Nursing & Midwifery Officer, Executive Director of Nursing and Midwifery or Executive Director Nursing Services, with between 18 and 47 years of nursing experience. In addition to Nursing or Midwifery, participants also held multiple portfolios including education, quality and risk, infection control, ancillary support services and acute and midwifery operational service management. To maintain anonymity, additional specific details for participants (e.g. participant gender) are not provided, and participants remained anonymous to the larger group.

3.2. Themes and sub‐themes

There were four main themes identified: (1) rapid, relentless, around the clock action; (2) nursing's multifaceted contribution; (3) unintended consequences and (4) silver linings (Table 1). While themes are presented separately, they are overlapping and inter‐related. In text below, themes are bold and underlined, and sub‐themes are italicized and underlined.

TABLE 1.

Themes and sub‐themes for nurse executives responding to the COVID‐19 pandemic

| Rapid, relentless, around the clock action | Nursing's multifaceted contribution | Unintended consequences | Silver linings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insufficient preparation | Leadership activities | Experience of addressing the pandemic | Expanded ways of working |

| Extensive information and communication | Flexible work approach and practices | Mix of emotions | Strengthened clinical practice |

| Expanded working relationships | Knowledge development and dissemination | Difficult personal and work conditions | New opportunities |

| Constant change | New models of care | Negative outcomes | Deepened relationships |

| Removal of organizational barriers | Workforce numbers |

Rapid, relentless, 24/7, 360° action required

All participants noted that constant engagement in their roles was required. Five sub‐themes underpinned the relentless action: (i) insufficient preparation, (ii), extensive information and communication, (iii) expanded working relationships, (iv) constant change and (v) the removal of barriers.

While some participants indicated having experience in similar health crises, and hospitals had pandemic‐specific and emergency plans, the preparation for COVID‐19 was mostly insufficient for the reality. One participant noted:

We had to dust off an old pandemic plan that was just threadbare. There was nothing of much value in it, and it really didn't address anything on this sort of scale or with this sort of level of transmission. So we were totally unprepared for what was coming. (Participant 002)

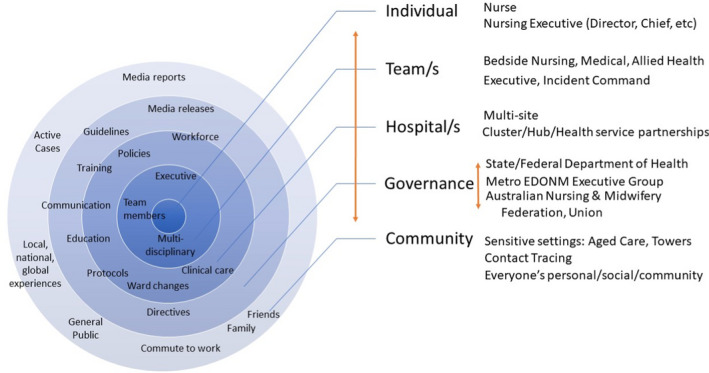

With so little in place, all participants referred to the frustratingly extensive information and communication flow , with high volumes of information being received and delivered from multiple sources and in various formats (Figure 2). External inputs ranged from Federal and State government, nursing union, international and local colleagues, and media releases. Details covered operational and policy directives, and COVID‐19 case numbers and locations.

FIGURE 2.

Influential inputs, output and contextual factors across multiple levels for nursing/midwifery addressing pandemic

… so there were multiple sources of information, some of them more reliable than others, that was just leading to great confusion to be quite honest. (Participant 008)

Keeping staff informed safely required changing to multi‐modal methods including predominantly virtual meetings (via Microsoft Teams) with face‐to‐face options not often available.

Working relationships were extensive and mostly supportive. Individuals held multiple roles within multiple teams, including Executive and Incident Command in their healthcare service and externally in multi‐site groups and government oversight. Internal hospital working relationships included executive teams and management, and members of nursing, medical, allied health and support services.

We still meet as an executive team daily. One of the things that we received a lot of really positive feedback for was that people said they really appreciated the rapid decision‐making that meeting daily provided and people didn't feel they were having to wait. (Participant 014)

External connections included government departments, armed defence forces and professional cleaning companies. Multiple health governance bodies were involved, government and community agencies and the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (ANMF; Union), with participants juggling and drawing on these multiple relationships.

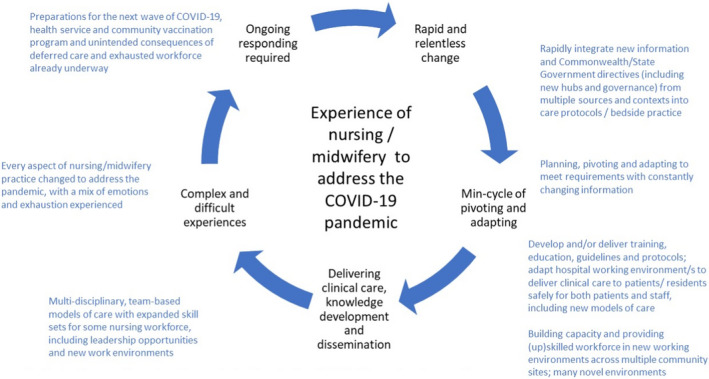

Change was constant, and involved operational and clinical processes. Each new, updated or amended piece of information initiated a cycle of rapid change management to occur, including absorbing or comparing new information (e.g. infection control details), identifying the flow‐on effects and associated consequences, addressing changing and ongoing responding to deliver clinical care in new and complex settings (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Cycle of preparing, planning and pivoting during COVID‐19 pandemic, ongoing

It was changing on a daily basis, sometimes an hourly or two‐hourly basis. (Participant 013)

New geographically based hubs of multiple health services (now called Health Service Partnerships) were implemented to organize and deliver care. These hubs required governance infrastructure, working relationships and protocols to be developed, operationalized and established, in addition to those underway within each health service. Support to address and undertake these changes was predominantly from the removal of organizational barriers . Governance of changes by multiple committees was reduced, business cases or change impact analyses were not required to the same degree as pre‐COVID‐19, and expedited processes for financial approvals were established.

Normally we're very consultative and to get policy changes takes probably about three months for them to go through all the various committees. It was just approved through incident command and put up that day. (Participant 006)

We had thrown around a centralized recruitment model at some point [prior to COVID‐19]. We had kind of a business case so we knew how it would work and we just stood it up, basically. (Participant 012)

Nursing's response was a multi‐faceted contribution

All participants noted a range of contributions that nursing had made with five main sub‐themes identified: (i) leadership activities, (ii) flexible work approach and practices, (iii) knowledge development and dissemination, (iv) adapting models of care and (v) providing workforce.

Nursing executives played a critical role in the leadership activities for the COVID‐19 response, including within and external to the hospital. Nurse executives were chairing committees, leading command teams and delivering surge workforce. Many participants noted that across multiple jurisdictions (e.g. State government, Commonwealth government, primary health, health service partnerships), it was not clear as to who was in charge of addressing the impact of the pandemic; be it at a specific facility or group of health services. In many circumstances outside of their home hospital setting, nursing executives stepped up to fill this leadership gap to source, direct and coordinate required resources (e.g. information, workforce, protocols). Within the hospitals, nursing leads were part of Incident Command teams, COVID Executive groups or addressing Code Brown. Leadership roles external to the hospital included across organizations (e.g. multiple Aged Care facilities) and other health services (e.g. as part of health service hubs) and with the State Government, including being on Steering Committees, Advisory Committees and Clinical Expert Taskforces.

One of our executives did say to me, “Gosh, it's actually ‐ it's nurses that are really leading this response, isn't it?” (Participant 011)

Visibility of leadership occurred through regular communications, including virtual meetings with hundreds of personnel participating.

Participants noted that a flexible work approach and self‐initiated practices were required. Without established procedures, and delays in directives, nursing executives were making decisions as to how best address current circumstances immediately.

We were probably four to six weeks ahead of the Department. So, we would implement things and then four to six weeks later they would put out a policy saying ‘This is how it's going to be’ … but we wouldn't sit on our hands, I suppose, and wait for that to come through. (Participant 008)

If we'd waited for the guidelines, we wouldn't have had those positions [COVID safety spotters] to keep our staff safe. (Participant 013)

Decision‐making was undertaken outside usual or ideal conditions; that is, large‐scale changes to workforce and models of care to address circumstances were made without all of the required information or resources available.

Everything that came out was almost too late. (Participant 005)

This flexible approach included some participants having to work at patient bedsides to provide patient care themselves due to staffing shortages, and then liaising with senior Federal Government officials about the on‐the‐ground reality, and the requirements to meet demands on health service and healthcare.

…to the point that ‐ and you'll no doubt hear this from others ‐ I was in scrubs. I was giving care. I was washing and feeding. It's been a while since I've been on the tools. (Participant 002)

…and pulling massive hours, to get it all ‐ stay on top of it all. Plus running a hospital, as well. It's not just all about COVID [laughs]. We still had to run the health services. (Participant 009)

Nursing executives were required to, and able to, take calculated risks, based on their knowledge and expertise in managing processes and personnel during emergency, life‐threatening circumstances. To meet the demands and context, they changed how they led, how they managed personnel and processes, and how they communicated.

I have a strong belief in visible leadership, okay. All of a sudden, that visibility, how you led changed, because I couldn't be out there on the floor. I wasn't allowed to go on the red zones anymore and you know, I think that was challenging too. (Participant 001)

COVID‐19 specific knowledge development and dissemination included operational and policy contributions. The development and delivery of clinical care protocols and guidelines within a COVID‐19 setting, and associated training and education. In particular, it was nursing primarily responsible for ensuring PPE protocols (e.g. donning/doffing safely) and ensuring infection control procedures were developed, delivered and adhered to across hospitals and other health services.

3.3.

I think one of the things I'm really incredibly proud of is the training team that [we] stood up virtually overnight. That went out across the state, so that people could have some training in how to use PPE because it was a gap within the private aged care that we just had previously been blinded to. Where they had equipment, they didn't know how to use it, and oftentimes they didn't have equipment. (Participant 014)

Contributions external to hospital settings included the National Quality Standards for Infection Control, a detailed submission to the Aged Care Royal Commission outlining the significant failings of the aged care setting for their residents, and participating in State and Federal governance bodies.

I was talking to the Chief Medical Officer for Australia and he was listening to me and being guided by me … you know, I'm a [nursing executive‐level role] working in a health service, and, no, I'm not normally in that position. (Participant 004)

New models of care were implemented including setting up COVID‐19 and suspected COVID‐19 patient pathways including specific wards, new telehealth models which required clinicians and patients having to learn and adapt under novel and difficult conditions, and treatments at home were expanded.

Obviously, we've been doing telehealth, a lot more telehealth, providing more care at home. … but some of our clinicians – “oh, it's just much easier to pick up the phone and dial the number and speak on the phone”. But then they say to us, “I'm a bit concerned about that because I haven't seen them and I didn't get to take their blood pressure and can you just set up a drive‐through blood pressure clinic”; that kind of thing. So, we did do that. (Participant 007)

Mobile models were required including mobile clinics for testing, the Mobile Aged Treatment Service and mobilizing teams to provide care in new or expanded settings. Incorporating care delivery safely for those who were in quarantine or isolation had to occur, including those incarcerated. To maximize available staffing, rosters changed to two 12‐h shifts (from three 8‐h shifts), including changes to the number of days worked and breaks.

There's only so many ways you can slice the pie if you don't have enough nurses to provide care in the traditional way. You've just got to look at how do you share that. (Participant 014)

Exposure times were limited for patient and staff safety, requiring changes to how patient‐facing activities were conducted (e.g. to‐do list outside patient room to be completed by the next person to enter, limits to visitors). When working off‐site, novel models for staff safety were implemented, including the use of truck‐based facilities so nurses could safely access services (e.g. bathrooms, break area, meals) when working at an external facility.

Nursing provided the workforce which underpinned the pandemic response across multiple areas. While other disciplines were able to separate from direct patient contact (e.g. many allied health moved to telehealth models, elective surgery was cancelled), face‐to‐face nursing was still required and identified for additional large‐scale activities.

Look, every profession has a role, doesn't it? But the 24/7, the constant is the nurse and I think nurses, through COVID, came to value that. That there is a role around connecting … They are the backbone of a health service. They are the glue that holds the system together and COVID really highlighted that. (Participant 011)

Nurses were identified as the essential workforce for many activities addressing COVID‐19. Within the hospital, this included screening, surveillance, delivering education and training, and external to the hospital included community testing, contact tracing. Nurses also had to completely manage and run facilities outside of the home health service.

You can see how this all just became this perfect storm of stuff, and in the meantime, we had to set up the observer program, and then we had to set up a COVID marshal program, and then we had to do the vaccination program. This all pulls our resources and the staff just aren't there. We're all competing for the same staff. It's just … it's hard. It was, and it still is, a hard environment. (Participant 006)

This workforce had to be identified, trained and operational (often with very short timeframes) within new or extended to settings such as hotel quarantine, public housing residential towers, correctional facilities, privately owned residential aged care facilities and to those that are homeless while maintaining staff and patient safety. Nursing flexibility supported this including theatre staff being trained to be ICU staff, or observation unit nurses being trained to be members of the emergency department team.

There were multiple nurse‐led initiatives such as pilots and programmes for equipment fit testing and community watch. In some cases, a whole team or ward needed to be furloughed due to a COVID‐19 case contact/outbreak, and replacement workforce members were required to be sourced, trained, deployed and supported. These activities were not identified prior to the pandemic, but were negotiated and undertaken in real time.

I can remember on a Friday night we were notified that we had … one staff ‐ two staff and then another four staff within a matter of six hours COVID positive and then we had to shut our ED down which was significant. … We didn't shut it down completely; we did a whole new model of care but we had to furlough 500 staff from that ED at that time. (Participant 001)

Unintended consequences

A number of unintended consequences were identified for the nurse leaders, extending to the nursing workforce. Sub‐themes included (i) nurse leaders' personal experience, (ii) a mix of emotions while managing a nursing workforce with (iii) difficult working conditions, leading to both (iv) short‐ and long‐term consequences, with some (iv) new opportunities.

Overall, participants described the difficult experience of addressing the pandemic as “super challenging” (Participant 003) and “incredibly hard” (Participant 002). Despite their decades of experiences in nursing/executive roles, participants described situations as “confronting” (Participants 010 and 011), “atrocious” (Participant 001), “distressing” (Participants 002 and 007), “horrific” (Participant 004), “scary” (Participant 011) and “absolutely unacceptable” (Participant 005). Participants referred to the “enormity of the work” (Participant 001), the “horrendous hours” (Participant 002), “almost crippled by” managing the size of the workforce required (Participant 005) and having to “struggle … ethically and morally” with asking staff to assist more (Participant 009).

I cannot believe we have to make decisions like this. (Participant 005)

I've never in my career not slept at night. I'm fairly robust on my sleeping behaviours but when we had the worry about PPE, the thought of not being able to provide a mask for someone really kept me awake at night. (Participant 010)

Some participants also noted that they personally experienced the policies they were developing and implementing, including being unable to visit a hospitalized family member.

There were some positive aspects of the experience, including all reporting an immense pride in the nursing workforce, the scope and scale of the contribution that nursing made, and knowing that the efforts of nursing had really “made a difference” (Participant 005), with one saying they were “exceptionally proud of the profession” (Participant 001). Working relationships within and across organizations were important, and mostly very supportive. In particular, participants referred to their metro EDONM group colleagues and State Chief Nursing Officer (located within Safer Care Victoria team and key interface with Department of Health).

But I think one of the things we're really proud of is how willing folk are in a crisis to do whatever's required to keep staff safe and our patients safe. (Participant 004)

[re the Executive Directors of Nursing and Midwifery group] It was just really important to understand each other's challenges and know that we were all going through the same challenges and that you had a safe place to tell each other how hard it was ‐ professionally, emotionally, psychologically. So I think I felt that was a really excellent space. (Participant 003)

Participants reported experiencing a mix of emotions . Specific to managing workforce, participants noted being proud and humbled by the response of nurses; however, some also referred to feeling guilt (e.g. having to ask more of nurses already at capacity) and one noted being embarrassed (e.g. no or few nurses responding to requests to support another organization). More broadly, feelings of high anxiety, stress, fear, depression, mental health struggles including symptoms similar to post‐traumatic stress disorder were all reported.

A number of participants noted that nursing was so critical in 2020—the International Year of the Nurse and the Midwife.

How ironic that it was the year of the nurse and midwife in 2020 and did nurses and midwives not demonstrate absolutely why we had a year dedicated to nurses and midwives? (Participant 007)

Continuing to work through the pandemic meant working through difficult personal and work conditions .

When I think of the relentless hours, the stress and anxiety ‐ and that was not just in their work environment, often it was at home because they were trying to home‐school and everything else. (Participant 002)

During 2020 while having to personally juggle the pandemic, nurse leaders were managing a nursing workforce, many with fears of getting COVID at work, additional stressful conditions (e.g. an increase in occupational violence, an increase in patient falls with no visitors), having to deliver care with questionable PPE (e.g. masks that were not fit‐for‐purpose, masks not fit tested) which was hot and difficult to work in, and changes to working with management and colleagues (e.g. face‐to‐face debriefings reduced or removed, working in isolation).

It wasn't the tram drivers that were getting it. It was the nurses at the bedside. So, why was that? Why would I want to go and work in that environment? Even though you tell me I'll be in full PPE, people are still getting COVID in full PPE. (Participant 005)

With so many changes taking place, there were reports of nursing being mistrustful of information and management. More broadly, nursing groups identified that other nursing groups and disciples within and across hospitals and other Australian states had better conditions (e.g. more and better resources available to others such as quality PPE, fewer numbers of cases in settings, lower exposure risks particularly for other disciplines, greater ability to live relatively normal life in other areas).

Negative outcomes for nursing , both short term and long term, were noted. Participants noted nurses having to “isolate pending test results [and] seeing colleagues falling” (Participant 002) with “30% loss during our outbreaks” (Participant 013). All participants reported that the experience has resulted in the nursing workforce being physically and mentally exhausted, and for many, emotionally traumatized.

I started to see exhaustion, and where the rapid change and the rapid pivoting was starting to really wear thin (Participant 012)

So, I don't actually think at the time, people realised fully the impact that it was having on them. (Participant 003)

For some, reports of nursing being angry and feeling abandoned (e.g. not having enough staff to deliver appropriate care in aged care facilities) as well as being disillusioned (e.g. variation in experiences across organizations). Longer term effects have led to increases in sick leave impacting workforce (e.g. additional shifts for those able to work), annual leave is not restorative (e.g. not able to travel, watching case numbers) and retirement options being brought forward.

I think we're paying for it now. I think we're paying for it in the emotional and physical burden that they had to pick up during that time. (Participant 001)

I worry that the nurses say that they can't do it again, that they really can't do it again. I think that's highly unlikely, but I worry about people's wellbeing. (Participant 011)

Silver linings

All participants noted a number of positive outcomes, that is, silver linings, from addressing the pandemic. Three sub‐themes were (i) ways of working expanded, (ii) clinical practice strengthened and (iii) relationships deepened.

A main beneficial outcome was that ways of working were expanded . The experience of the pandemic improved opportunities for multi‐disciplinary teams, and team‐based models of care were successful. Many barriers and siloed ways of working were broken down or improved (e.g. between medical and nursing, two‐way respect and reliance on each other, although in place pre‐pandemic, were now increased) and many new models of care that were developed which participants hoped would be retained. Agile change management processes were established, including the implementation of rapid innovation and communication practices to improve access and connectedness to personnel, and many noted (and hoped) that these also would be retained.

We can stand up a pop‐up screening clinic in about four hours now. We've got it down so pat. It's amazing what we can do. That kind of agility is pretty impressive, and we don't want to lose it. (Participant 006)

Registered undergraduate student nurses who had been deployed to services were transitioning well to registered nurses were reported, including “hitting the ground running” (Participant 002).

Clinical practice has been strengthened , internal and external to hospitals, including infection control practices, telehealth fast‐tracked in multiple areas (although not all retained during non‐high COVID‐19 periods), and expanded skill set and experience extending career options for nursing.

[Name of health service removed] been a bit slow to adopt virtual care but that took off overnight as it should have many years earlier. (Participant 011)

In particular, many systems within aged care facilities were improved and retained, including protocols, governance and clinical care established.

Some new opportunities were described, particularly leadership opportunities became available. One participant noted that a nurse had indicated that the work they were involved in was the “highlight of her career” (Participant 011), others noted that it was “empowering” (Participants 008 and 013).

It's helped them [nurse managers] also find more of their voice and their power to influence and drive changes and not sweat the small stuff and just get on. Things that we've been challenged with for many years and we've just sort of crashed through a lot of that now. (Participant 002)

I think our line managers have really been able to take leadership learning and really apply them. So I think that they are far better leaders than what they were at the start of this and we're absolutely seeing them wanting to be more autonomous and that's a great thing. So I think that that's been a positive out of it. (Participant 008)

Student nurses had an expanded role, described as “scary but rewarding” (Participant 011).

Another silver lining was the deepening of work relationships , including expanded collegiate working relationships and professional connections, extended respect for others' work areas particularly for support services such as cleaning and catering, with many participants noted a stronger connection with team members.

Nurses might be at the forefront of it, we're also the largest workforce but nobody does this alone. Never before have cleaners been more important to be alongside our professions. The expertise of our medical staff, the willingness of our allied health staff to take on completely different roles. They were so important in our response as well. (Participant 011)

Some noted that the value of nursing by the community increased.

4. DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first analysis conducted focusing on the nurse executive experience of managing the COVID‐19 pandemic across multiple metropolitan health services. Nurse executives' leadership and management of hospital's responses during an epidemic upsurge led delivery of critical healthcare, as safely as possible for patients and staff, across established and novel settings with old and new working relationships. In particular, previously identified clinical leadership attributes (Stanley & Stanley, 2018) in addition to clinical knowledge and competence were displayed by nurse executives, including decision‐maker, effective communicator, motivator for others, visibility and team‐focussed approaches. While other positives such as innovative models of care have been established, many short‐ and long‐term negative individual, workforce and organizational impacts were experienced. The pandemic has disrupted how healthcare systems are operating, and how workforces operate. In turn, the profile of nursing has been raised, including as agents of change (as illustrated by our participants' experiences), in line with the Nursing Now campaign initiated by the World Health Organization and the International Council of Nurses (Holloway et al., 2021). Our analysis of the responses and repercussions provides important insights to the contributions made and challenges faced for others to consider.

4.1. The pandemic allowed nursing to work to full potential

Nursing is often undervalued and in the shadow of the medical profession (All‐Party Parliamentary Group on Global Health, 2016) or silenced (Daly et al., 2020). However, the health crisis situation provided the circumstances under which limitations—both historical (e.g. scope of practice and role definitions were blended and expanded) and industrial (e.g. greater freedoms to utilize students and flexible rostering approaches) projected onto nursing—were removed or ignored. Our experience suggests that no other clinical group stepped up to coordinate or be in charge of addressing such issues to the same scale, demonstrating critical leadership skills to develop and delivering preventative and responsive strategies, policymaking and operations. Examples included managing the crisis in the aged care setting, leading health policy decision‐making, implementing innovative models of care, and preparing staffing resources for adapted COVID and suspected COVID patient care pathways. The crisis circumstances of the pandemic provided an opportunity for nursing to work to top of practice and illustrated interprofessional working and collaboration practices of values‐based leadership (James et al., 2021). This collaboration included within the metro EDONM group where increased meeting frequency supported sharing of operational approaches and resources, alongside relevant knowledge and skills. Nursing's diverse skills and expertise support continuity of care (Australian Nursing and Midwifery Foundation, 2018) including planning and implementing clinical management, infection prevention and control, and delivery of specific acute and chronic care (e.g. emergency, palliative) for communicable and non‐communicable disease. Our results indicate that this expertise supported nursing to lead significant local change.

While nursing practice is person centred and evidence based (Australian Nursing and Midwifery Foundation, 2018), evidence for delivering care in a COVID‐19 context was lacking, delayed or changing over time (including how COVID‐19 was transmitted). Support from working relationships with government and union was important, but while some jurisdictional barriers were actively removed, others remained and governmental directives were delayed or contradictory information received. As such, nursing executives had to spearhead change, and be decisive without a solid evidence base. In the face of such uncertainty, personal and professional qualities merged, with leadership comprising courageous decision‐making, taking calculated risks and being agile and constantly re‐inventing clinical, management and communication practices (Aquilia et al., 2020). Nurse leaders in the United States have also reported significant decision‐making with limited information (Aquilia et al., 2020), with another reporting nurse leaders demonstrating significant adaptability and innovation while overworked and stressed (Freitas et al., 2021).

4.2. Addressing change, challenges and uncertainty required nursing to be trailblazers

Capitalizing on nurse leadership is one of the International Council of Nurses' key priorities to beat COVID‐19 (International Council of Nurses, 2020). Drawing on their specialist expertise and experience, nurse executives in the current study were leading changes and improvements, re‐engineering the workforce and physical environment, and ensuring that barriers did not get in the way of what was required to be done. Recent research in one hospital (n = 6 nurse leaders, Brazil) also reported substantial workforce and environmental changes undertaken by nursing (Freitas et al., 2021). For our participants, these changes occurred internally and externally to the home hospital, including working with other health services (as part of a hub) further extending their work environments, working remotely from the hospital or team members. Without established procedures (Joslin & Joslin, 2020), nurse executives were trailblazers ensuring that multiple new models of care were developed, resourced and implemented to meet patient and staff needs safely. As reported elsewhere (Kerrissey & Singer, 2020), identifying someone in charge of the response proved difficult at times, and similar to that in the United States (Stucky et al., 2020), the pandemic exposed limitations in the local healthcare system, particularly in aged care (Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, 2020), with increased risks for those working there (Nguyen et al., 2020). One local example had nursing lead and operate all aspects of a number of aged care facilities, well beyond usual practice and with limited facility staff.

A number of innovations were reported by participants, including new models of care, novel communication practices, and input and leadership from unexpected staff. International work has outlined how the pandemic has provided a unique circumstance for nursing practice reforms, including change in practice (Stucky et al., 2020). For example, a number of legislative changes were made within the United States to extend the role of nurse practitioners' practice. For many, the use of undergraduate nurses in the workforce was an innovative model, but not without risk. However, reports of adapting well to registered roles suggest for many this was a successful approach. In a content analysis of USA graduating nurses' (n = 84) assessment of personal practice within COVID‐19, the majority indicated they were willing to care for COVID‐19 patients but robust PPE was required (Lancaster et al., 2021). Such innovations were supported through funding available to address COVID‐19, cross‐functional teams and a shared purpose, and should not be rolled back. Others have also identified that benefits gained though addressing the pandemic should be maintained (Palese et al., 2021).

4.3. Feelings of safety and well‐being depleted

These contributions and meeting the challenges have, however, come at a cost. Under resourced healthcare systems were already under pressure prior to the pandemic. Having to work at patient bedsides has been reported by other nurse leaders (Aquilia et al., 2020), illustrating the pervasiveness of the virus and insufficient workforce available. Many participants reported on the toll on themselves and on their teams, including working through concerns about their own physical safety, the distressing experiences in aged care settings or through the lack of family visitors in hospitals. With nurses working so closely and constantly with patients, their exposure and risk were significantly higher than other roles. Indeed, of the 764 cases contracted in Victorian hospitals, 75% (n = 572) were nurses and midwives (compared with 14% were medical practitioners) (Victorian Department of Health, 2021).

Nurse executives described considerable negative experiences, providing the first insights into the emotional impact at this level. Those in management positions have a double responsibility, addressing both patient and staff needs and safety. Addressing patient outcomes, and work environment and job satisfaction are part of values‐based leadership models (James et al., 2021). Participants reported ethical dilemmas (e.g. which clinical trials to continue, which to cease; inadequate PPE available for staff, asking more from an exhausted workforce), as reported elsewhere (Aquilia et al., 2020). Moral distress has been previously associated with absences and turnover (Gaudine & Thorne, 2012). Conflicting obligations have also been previously reported for nursing (Lancaster et al., 2021) with low resilience and job satisfaction associated with executive nurse turnover (Bernard, 2021).

Nurses' willingness to continue to work, working face‐to‐face with other staff and patients at their home hospital or in other settings were commonly reported, with some hesitancy revealed to move from non‐COVID to COVID settings by a few participants. Difficulties of working included safety/risk concerns to self and their families, along with the discomfort of working in PPE have been reported by the ANMF (Adelson et al., 2021) and elsewhere (Lancaster et al., 2021). In their survey of 32,174 nurses, the American Nursing Association reported that 87% were ‘very’ or ‘somewhat’ afraid to go to work (American Nursing Association, 2020). Results also indicated that 68% of nurses were worried about staff shortages (American Nursing Association, 2020). In their survey (n = 13,410, 85% nurses, midwives or personal care workers), the ANMF reported high levels of emotional exhaustion for those working in residential aged care facilities and hospitals (Adelson et al., 2021). Continuing to provide care despite risks has previously been reported by Australian healthcare workers as a professional obligation (Seale et al., 2009).

The capacity and resilience of the workforce, both at bedside and executive levels, has been depleted (Galanis et al., 2021). Higher nursing workload has been reported internationally (Hoogendoorn et al., 2021), along with behavioural and psychological impacts (American Nurses Foundation, 2020). A recent scoping review of healthcare workers risks during COVID‐19 found that nurses had the worst health outcomes (Franklin & Gkiouleka, 2021). In a sample of 10,997 nurses surveyed in the United States between March and July 2020, about half reported feeling overwhelmed (51%), anxious or unable to relax (48%) and irritable (48%) with 60% reporting having difficulty sleeping or sleeping too much (American Nurses Foundation, 2020). Of concern, is that little is known how to address front line healthcare workers' resilience and well‐being during infectious disease outbreaks (Pollock et al., 2020). This gap must be addressed urgently to support nursing and the broader healthcare workforce (e.g. Suleiman‐Martos et al., 2020), and for the next generation of nurse leaders. In the face of this exhaustion and traumatic experience, nurse leaders have to continue addressing the pandemic through continuing outbreaks, usual care and now the vaccination programme rollout. Unfortunately, COVID‐19 Delta and Omicron variant cases in two Australian states (including Victoria) are increasing, putting our healthcare systems under significant pressure again. While many lessons have been learnt in the last 18 months that can be drawn on to improve healthcare, sustaining nursing in terms of both staff (e.g. mental health, well‐being) and practice (e.g. innovative ways of working) need to be addressed (Adelson et al., 2021). Based on the contributions, negative consequences and potential risks identified in our study, we provide our top five recommendations for addressing widespread health emergencies (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Research aims and identified risks, and associated recommendations for nursing to address widespread health emergencies

| Research aim | Identified current and potential risks | Recommendations | Actions to address recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing's contribution to the healthcare response |

|

1. Capitalize on breadth and depth of nursing leadership skills and expertise to meet healthcare needs |

|

| Context in which nursing and nursing executives work |

|

2. Ensure adequate operational and psychological support and connection is available across all levels of nursing |

|

|

3. Build a sustainable workforce to deliver healthcare |

|

|

|

4. Prepare for new home‐based models of care given changing circumstances |

|

|

| Impact from delivering healthcare in response to the pandemic |

|

5. Address physical and psychological impact of working on workforce within local and global health emergencies |

|

4.4. Strengths and limitations

The current study has a number of strengths including the robust qualitative methodology using a constructivist approach. This design allowed an in‐depth exploration and presentation of executive nurses' insights and experiences. Nurse executives were from multiple health services at the epicentre of the COVID‐19 pandemic in a large metropolitan city. Many of our insights are relevant to global nursing policy and practice. Limitations, however, need to be considered. This study is based on a small, pragmatic sample, and to maintain anonymity we were unable to report on demographics. This gap meant we could not speak to inclusive (or not) representation across health services for nursing at the executive level. However, participants represented all of the nursing executives actively responding to COVID‐19 for the major metropolitan hospitals in a large metropolitan city of Australia during 2020. This study focused on the experiences and perspectives of the executive level. Future research is required to capture that of the bedside nursing workforce, and that of Nurse Unit Managers. It is to be noted that as the work was initiated and conceptualized by the group, many of the authors acted as participants as well. The scope and scale of participant reports were extensive, reflecting the range of their experiences during 2020. While many nursing executives shared experiences, some had unique role/s and many areas warrant a detailed exploration outside the scope of this work, including how nursing led the aged care response, multi‐disciplinary education in infection control or transitioning workforce across specialities and/or unique settings.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In the first year of responding to the COVID‐19 pandemic, nurse executives detailed a complex context of multiple stakeholders, extensive information and constant changes. Significant leadership qualities consistent with values‐based leadership models, including being proactive, rapid decision‐making, flexible work approach and agile change management were required to identify and mobilize resources and infrastructure to design and implement acute, community and public health policies, and develop and deliver protocols for safe practice. These results illustrate the breadth and impact of the experience of nursing responding to the COVID‐19 pandemic across a range of healthcare settings. During the International Year of the Nurse and the Midwife, nursing went beyond being key stakeholders to proactively leading the development and delivery of health services and community, ensuring continuity of care to patients. For the sustainability of nursing, nurse executives and health services, attention must be paid to addressing workforce exhaustion and trauma. As outlined in the recommendations, maintaining the opportunity to work to the full scope of nursing practice should continue and be leveraged to emphasize nursing's contribution at all times in healthcare.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The Victorian metropolitan Executive Directors of Nursing and Midwifery Group initiated and members were participants in this research. An experienced researcher independent from the group was funded to conduct all aspects of the research.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have agreed on the final version and meet at least one of the following criteria: (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. CRediT authorship: Kathryn Riddell: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; methodology; project administration; writing – review and editing, Supervision. Laura Bignell: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Debra Bourne: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Leanne Boyd: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Shane Crowe: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Sinéad Cucanic: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Maria Flynn: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Kate Gillan: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Denise Heinjus: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Jac Mathieson: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Katrina Nankervis: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Fiona Reed: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Linda Townsend: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Bernadette Twomey: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Janet Weir‐Phyland: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing. Kathleen Bagot: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; validation; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing, visualization, supervision.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The St Vincent's Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study (72529, LRR 001/21; 22 January 2021). Participation was voluntary and confidential from the group membership. Verbal consent was obtained from participants prior to the interview recording commencing. Illustrative quotes are deidentified.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/jan.15186.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Prof Elizabeth McInnes (EM) for her review and feedback on an initial draft of results and manuscript. Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley ‐ University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Riddell, K. , Bignell, L. , Bourne, D. , Boyd, L. , Crowe, S. , Cucanic, S. , Flynn, M. , Gillan, K. , Heinjus, D. , Mathieson, J. , Nankervis, K. , Reed, F. , Townsend, L. , Twomey, B. , Weir‐Phyland, J. & Bagot, K. (2022). The context, contribution and consequences of addressing the COVID‐19 pandemic: A qualitative exploration of executive nurses' perspectives. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78, 2214–2231. 10.1111/jan.15186

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not‐for‐profit sectors. In‐kind support from each author's hospital.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- Adelson, P. , Fish, J. , Peters, M. , Corsini, N. , Sharplin, G. , & Eckert, M. (2021). COVID‐19 and workforce wellbeing: A survey of the Australian nursing, midwifery, and care worker workforce. A report prepared for the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation. (pp. 116). University of South Australia. [Google Scholar]

- All‐Party Parliamentary Group on Global Health . (2016). Triple impact: How developing nursing will improve health, promote gender equality and support economic growth. https://www.who.int/hrh/com‐heeg/digital‐APPG_triple‐impact.pdf

- American Nurses Foundation . (2020). COVID‐19 survey series 1: Mental health and wellness. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice‐policy/work‐environment/health‐safety/disaster‐preparedness/coronavirus/what‐you‐need‐to‐know/mental‐health‐and‐wellbeing‐survey/

- American Nursing Association . (2020). Find out what 32,000 nurses want you to know about treating COVID‐19. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice‐policy/work‐environment/health‐safety/disaster‐preparedness/coronavirus/what‐you‐need‐to‐know/covid‐19‐survey‐results/

- Aquilia, A. , Grimley, K. , Jacobs, B. , Kosturko, M. , Mansfield, J. , Mathers, C. , Parniawski, P. , Wood, L. , & Niederhauser, V. (2020). Nursing leadership during COVID‐19: Enhancing patient, family and workforce experience. Patient Experience Journal, 7(2), 136–143. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics . (2021). Regional population 2019‐20 financial year. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/regional‐population/2019‐20

- Australian Government . (2020). Australian health sector emergency response plan for novel coronavirus (COVID‐19) ‐ short form. Australian Government Retrieved from https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/australian‐health‐sector‐emergency‐response‐plan‐for‐novel‐coronavirus‐covid‐19‐short‐form

- Australian Government Department of Health . (2020). Current status of confirmed cases. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/12/coronavirus‐covid‐19‐at‐a‐glance‐2‐december‐2020‐coronavirus‐covid‐19‐at‐a‐glance‐2‐december‐2020.pdf

- Australian Nursing and Midwifery Foundation . (2018). Nursing practice. (Online). ANMF. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, N. (2021). The relationships between resilience, job satisfaction, and anticipated turnover in CNOs. Nurse Leader, 19(1), 101–107. 10.1016/j.mnl.2020.10.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In Cooper P. M. C. H., Long D. L., Panter A. T., Rindskopf D., & Sher K. J. (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp, N. , Brownie, S. , & Refsum, C. D. (2018). Nursing & midwifery: The key to the rapid and cost effective expansion of high quality universal healthcare world innovation summit for health (pp. 1–39). World Innovation Summit for Health. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, J. , Jackson, D. , Anders, R. , & Davidson, P. M. (2020). Who speaks for nursing? COVID‐19 highlighting gaps in leadership. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(15–16), 2751–2752. 10.1111/jocn.15305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, P. , & Gkiouleka, A. (2021). A scoping review of psychosocial risks to health workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2453. 10.3390/ijerph18052453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, J. , Queiroz, A. , Bortotti, I. , Laselva, C. , & Leão, E. (2021). Nurse Leaders' challenges fighting the COVID‐19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Open Journal of Nursing, 11, 267–280. 10.4236/ojn.2021.115024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galanis, P. , Vraka, I. , Fragkou, D. , Bilali, A. , & Kaitelidou, D. (2021). Nurses' burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(8), 3286–3302. 10.1111/jan.14839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudine, A. , & Thorne, L. (2012). Nurses' ethical conflict with hospitals: A longitudinal study of outcomes. Nursing Ethics, 19(6), 727–737. 10.1177/0969733011421626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halcomb, E. , Williams, A. , Ashley, C. , McInnes, S. , Stephen, C. , Calma, K. , & James, S. (2020). The support needs of Australian primary health care nurses during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(7), 1553–1560. 10.1111/jonm.13108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hølge‐Hazelton, B. , Kjerholt, M. , Rosted, E. , Thestrup Hansen, S. , Zacho Borre, L. , & McCormack, B. (2021). Health professional frontline Leaders' experiences during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A cross‐sectional study. Journal of Healthcare Leadership, 13, 7–18. 10.2147/jhl.S287243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway, A. , Thomson, A. , Stilwell, B. , Finch, H. , Irwin, K. , & Crisp, N. (2021). Agents of change: The story of the nursing now campaign. Burdett Trust for Nursing. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogendoorn, M. E. , Brinkman, S. , Bosman, R. J. , Haringman, J. , de Keizer, N. F. , & Spijkstra, J. J. (2021). The impact of COVID‐19 on nursing workload and planning of nursing staff on the intensive care: A prospective descriptive multicenter study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 121, 104005. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Council of Nurses (2020). ICN highlights top priorities to beat COVID‐19. https://www.icn.ch/news/icn‐highlights‐top‐priorities‐beat‐covid‐19

- James, A. H. , Bennett, C. L. , Blanchard, D. , & Stanley, D. (2021). Nursing and values‐based leadership: A literature review. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(5), 916–930. 10.1111/jonm.13273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joslin, D. , & Joslin, H. (2020). Nursing leadership COVID‐19 insight survey: Key concerns, primary challenges, and expectations for the future. Nurse Leader, 18(6), 527–531. 10.1016/j.mnl.2020.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrissey, M. J. , & Singer, S. J. (2020). Leading frontline COVID‐19 teams: Research‐informed strategies. NEJM Catalyst, Innovations in Care Delivery, 1–8. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/CAT.20.0192 [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, R. J. , Schmitt, C. , & Debish, M. (2021). A qualitative examination of graduating nurses' response to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Nursing Ethics, 28(7–8), 1337–1347. 10.1177/0969733021999772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litton, E. , Bucci, T. , Chavan, S. , Ho, Y. Y. , Holley, A. , Howard, G. , Huckson, S. , Kwong, P. , Millar, J. , Nguyen, N. , Secombe, P. , Ziegenfuss, M. , & Pilcher, D. (2020). Surge capacity of intensive care units in case of acute increase in demand caused by COVID‐19 in Australia. Medical Journal of Australia, 212(10), 463–467. 10.5694/mja2.50596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, A. P. , Austin, D. E. , Chamberlain, D. , Chapple, L.‐A. S. , Cree, M. , Fetterplace, K. , Foster, M. , Freeman‐Sanderson, A. , Fyfe, R. , Grealy, B. A. , Hodak, A. , Holley, A. , Kruger, P. , Kucharski, G. , Pollock, W. , Ridley, E. , Stewart, P. , Thomas, P. , Torresi, K. , & Williams, L. (2020). A critical care pandemic staffing framework in Australia. Australian Critical Care, 34, 123–131. 10.1016/j.aucc.2020.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L. H. , Drew, D. A. , Graham, M. S. , Joshi, A. D. , Guo, C.‐G. , Ma, W. , Mehta, R. S. , Warner, E. T. , Sikavi, D. R. , Lo, C‐H. , Kwon, S. , Song, M. , Mucci, L. A. , Stampfer, M. J. , Willett, W. C. , Eliassen, A. H. , Hart, J. E. , Chavarro, J. E. , Rich‐Edwards, J. W. , … Zhang, F. (2020). Risk of COVID‐19 among front‐line health‐care workers and the general community: A prospective cohort study. The Lancet Public Health, 5(9), e475–e483. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30164-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palese, A. , Papastavrou, E. , & Sermeus, W. (2021). Challenges and opportunities in health care and nursing management research in times of COVID‐19 outbreak. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(6), 1351–1355. 10.1111/jonm.13299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, A. , Campbell, P. , Cheyne, J. , Cowie, J. , Davis, B. , McCallum, J. , McGill, K. , Elders, A. , Hagen, S. , McClurg, D. , Torrens, C. , & Maxwell, M. (2020). Interventions to support the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic: A mixed methods systematic review. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews, 11, CD013779. 10.1002/14651858.Cd013779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley, A. L. , Stone, H. , Nguyen, P. Y. , Chughtai, A. A. , & MacIntyre, C. R. (2021). Estimating the burden of COVID‐19 on the Australian healthcare workers and health system. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 114, 103811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety . (2020). Aged care and COVID‐19: A special report (pp. 30). Commonwealth of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Seale, H. , Leask, J. , Po, K. , & MacIntyre, C. R. (2009). "Will they just pack up and leave?" – Attitudes and intended behaviour of hospital health care workers during an influenza pandemic. BMC Health Services Research, 9(1), 30. 10.1186/1472-6963-9-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, D. , & Stanley, K. (2018). Clinical leadership and nursing explored: A literature search. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(9–10), 1730–1743. 10.1111/jocn.14145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stucky, C. H. , Brown, W. J. , & Stucky, M. G. (2020). COVID 19: An unprecedented opportunity for nurse practitioners to reform healthcare and advocate for permanent full practice authority. Nursing Forum, 1‐6, 222–227. 10.1111/nuf.12515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suleiman‐Martos, N. , Gomez‐Urquiza, J. L. , Aguayo‐Estremera, R. , Cañadas‐De La Fuente, G. A. , De La Fuente‐Solana, E. I. , & Albendín‐García, L. (2020). The effect of mindfulness training on burnout syndrome in nursing: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(5), 1124–1140. 10.1111/jan.14318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. , Sainsbury, P. , & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, H. C. , Chen, T. F. , & Chou, S. M. (2005). SARS: Key factors in crisis management. Journal of Nursing Research, 13(1), 58–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victorian Department of Health . (2021). Victorian healthcare worker (clinical and non‐clinical) COVID‐19 data.

- World Health Organization . (2020). State of the World's nursing: Investing in education, jobs and leadership. WHO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003279

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.