Abstract

Aims

The present study investigated the association between resilience, stigma, life satisfaction and the intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination among Chinese HCWs. It also explored the mediating role of stigma and life satisfaction on the association between resilience and intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination.

Design

An anonymous cross‐sectional survey.

Methods

1733 HCWs from five hospitals in four provinces of mainland China completed a cross‐sectional online survey in October and November 2020.

Results

Among the HCWs, the rate of intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination was 73.1%. Results from structural equation modelling showed that resilience was associated both directly, and indirectly with greater intent to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination through two pathways: first by increasing life satisfaction, and second by reducing stigma and increasing life satisfaction.

Conclusion

Promoting the resilience of HCWs has the potential to increase the COVID‐19 vaccination uptake rate among HCWs in China.

Impact

This study tested the relationship between several psychological factors and the COVID‐19 vaccination intention of HCWs in China, finding that resilience played a significant role in improving COVID‐19 vaccination intention rates by reducing stigma and increasing life satisfaction.

Keywords: healthcare workers, intention, life satisfaction, nurses, resilience, self‐stigma, vaccination

1. INTRODUCTION

COVID‐19 has caused significant morbidity and mortality and has resulted in additional strains on the health care systems in many countries (Godderis et al., 2020). Healthcare workers (HCWs) are at the frontline of this pandemic, providing treatment and care for patients with COVID‐19. They are exposed to heavy workloads and work‐related stresses, whilst also being at significant risk of infection (Jones, 2020; Lai et al., 2020) due to various factors, such as frequent exposure to infected individuals, shortages of personal protective equipment, and inadequate infection control training (Gan et al., 2020). Infection of HCWs may reduce the available healthcare workforce, which then has a negative impact on effective pandemic control. Ensuring HCWs’ safety and protecting them from potential infection plays an important role in controlling nosocomial transmission (Lancet, 2020).

2. BACKGROUNDS

2.1. Importance of promoting COVID‐19 vaccination among HCWs

Due to the devastating impact of COVID‐19 on global health, often leading to fatalities, developing effective vaccines for this pandemic has become a top priority worldwide (McAteer et al., 2020; Padron‐Regalado, 2020). Vaccination will undoubtedly provide one of the most effective strategies in preventing the spread of the disease and facilitating the achievement of herd immunity in a population (Fu et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2020). The success of a vaccine relies not only on its efficacy but also on its coverage (Nuño et al., 2007). Therefore, improving the acceptance of COVID‐19 vaccinations is crucial in the prevention and elimination of COVID‐19.

HCWs are considered to be one of the most trustworthy sources of vaccine‐related information, as they can explain the benefits of vaccination and respond to the worries and concerns of the public (Larson, 2015). HCWs’ acceptance of COVID‐19 vaccination is also particularly important in boosting public confidence and decisions concerning the vaccines, which could, eventually, increase vaccine coverage in the community (Dempsey et al., 2018; Kabamba Nzaji et al., 2020; Mereckiene et al., 2014; Paterson et al., 2016). There is evidence that the vaccine hesitancy observed in the general population is closely linked to the level of vaccine hesitancy among HCWs (Arda et al., 2011). Hence, identifying the factors related to acceptance of COVID‐19 vaccination among HCWs is needed, to help prevent further infection and maximize public acceptance of COVID‐19 vaccinations.

2.2. Predictors for the intention to receive COVID‐19 vaccination among HCWs

It was reported that 76.4% of HCWs in China demonstrated a willingness to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination (Fu et al., 2020). Current studies on the factors related to HCWs’ willingness to become vaccinated against COVID‐19 showed that some demographic, health‐related and psychosocial factors, such as older age, male gender, involvement in the care of confirmed patients with COVID‐19, suffering from chronic conditions, greater self‐confidence and more collective responsibility, and acceptance of the influenza vaccination in 2019 were associated with stronger rates of COVID‐19 vaccine intention (Detoc et al., 2020; Dror et al., 2020; Fu et al., 2020; Grech et al., 2020; Kabamba Nzaji et al., 2020; Wang, Wong, et al., 2020). Reasons for hesitation or refusal of COVID‐19 vaccination included doubts about vaccine efficacy, effectiveness and safety, beliefs that vaccination was unnecessary, and lack of time (Wang, Wong, et al., 2020). On the other hand, it was also found that the proportion of HCWs showing concern about poor vaccine quality was twice that reported by the public (7% vs. 3%; Fu et al., 2020), suggesting that HCWs might have a more negative view of COVID‐19 vaccination.

2.3. Resilience and COVID‐19 vaccination intention

Psychological factors are known to play a vital role in the management of pandemics. Psychological resilience is commonly defined as the capacity of an individual or organization to survive and to adapt to difficult situations (Hart et al., 2014; Luthar et al., 2000). The importance of resilience stems from its direct link to the ability to cope effectively with adversities (Turenne et al., 2019), and the capacity and dynamic process to overcome stress adaptively while maintaining normal mental and physical functioning (Rutter, 2012; Wu et al., 2013). Resilience is a major component in positive psychology and is believed to play an important role in fostering well‐being and positive behaviours. The Broaden and Build Theory posits that positive emotions broaden thought‐action repertoires (Fredrickson, 2001). Positive emotionality, such as resiliency, prompts individuals to discard the limitations of negative emotions as they relate to cognition and behaviours, and to pursue more novel and creative paths of thought and action (Fredrickson & Joiner, 2002). The importance of psychological resilience comes to the fore during a pandemic period (Greenberg et al., 2020; Wang, Wong, et al., 2020). Promoting resilience has been listed as one of the 10 most important considerations for effectively managing the COVID‐19 transition worldwide (Habersaat et al., 2020).

Considering the inherent stress of the working environments of HCWs’, especially during the COVID‐19 period, resilience can be seen as a key attribute of HCWs. Previous studies found that highly‐resilient nurses reported better outcomes, such as lower burnout, depression and anxiety rates (Manzano García & Ayala Calvo, 2012), higher levels of job satisfaction (Matos et al., 2010) and the adoption of more active coping approaches (Ang et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2013). Resilience has also been shown to be positively associated with life satisfaction, self‐esteem, positive affect and health‐promoting behaviours (Cohn et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2013), while low levels of resilience have been associated with negative affect (Alarcón et al., 2020) in other populations. In the context of COVID‐19, studies have found that resilience is negatively associated with a sense of danger and symptoms of distress (Kimhi et al., 2020). It is conjectured, therefore, that resilience may be associated with the acceptance of a COVID‐19 vaccination, which is considered as an active and preventive behaviour taken to address the current pandemic situation. No studies to date have tested the relationship between resilience and HCWs’ levels of intention to receive a COVID vaccination.

2.4. Stigma and COVID‐19 vaccination intention

It is evident that HCWs are not only at a higher risk of exposure to COVID‐19, but they are also subject to considerable stigmatization due to their proximity to patients, as well as public fears of contracting the virus from them (Blake et al., 2020; Devakumar et al., 2020). Disease‐related stigmatization, such as those related to the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (Almutairi et al., 2018), and SARS (Bai et al., 2004; Maunder et al., 2006; Siu, 2008; Verma et al., 2004), has been previously reported among HCWs. In the COVID‐19 pandemic, stigma associated with infection was mentioned by about two‐thirds of Egyptian HCWs surveyed (Abdel Wahed et al., 2020). Another study in Korea also showed that 38% of HCWs reported experiences of social rejection due to engagement in COVID‐19 related work (Park et al., 2020). In the case of stigma related to infectious diseases, stigmatization, blame and discrimination are intensified due to fear of illness. Self‐stigma occurs when individuals internalize these public or social attitudes, suffering numerous negative consequences (Corrigan et al., 2006, 2010; Rüsch et al., 2005, 2010). In an Egyptian study, most HCWs surveyed reported experiencing COVID‐19‐related stigmatization, mainly from their neighbours and the people they interacted in their life (Mostafa et al., 2020). Stigma was found to be associated with lower levels of health‐promoting behaviours (Kato et al., 2016; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009) and poorer health outcomes (Fischer et al., 2019; Stuber et al., 2008). It is speculated that higher levels of stigma are associated with a lower level of intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination among HCWs.

2.5. Life satisfaction and COVID‐19 vaccination intention

Life satisfaction represents an overall evaluation of one's life and is an important component of subjective well‐being (Diener et al., 1999). Life satisfaction signifies a positive evaluation of life from the individual's perspective and may have similar function to positive emotions which, according to the Broaden and Build Theory, have the potential to expand the cognitive and behavioural repertoires of an individual (Fredrickson, 2001). Life satisfaction is associated with a range of positive psychological and behavioural outcomes, including preventive health behaviours (Jo et al., 2003; Lopuszanska‐Dawid, 2018) such as uptake of influenza vaccinations (Bock et al., 2017). Life satisfaction can also facilitate positive coping, engagement and problem solving, which may promote the intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination.

2.6. The mediating role of stigma and life satisfaction

Kumpfer postulates that stressors or challenges (e.g. the stressors caused by COVID‐19), environmental context (e.g. perceived stigma and peer support), internal self‐characteristics and person‐environment interactional processes are the main predictors of resilience, which, in turn, help individuals to cope well and achieve better life outcomes (e.g. life‐satisfaction; Kumpfer, 1999). According to Kumpfer's resilience framework, confronting the stressors and challenges in everyday life allows resilient individuals to develop psychosocial resources, which, in turn, increase their ability to cope with new stressors. Based on this framework and the extensive evidence of the positive effect of resilience on psychosocial and behavioural outcomes, it is therefore conjectured that resilience is indirectly associated with the intention to receive the COVID‐19 vaccination by promoting life satisfaction and reducing stigma among HCWs. Highly‐resilient nurses showed higher levels of life satisfaction (Matos et al., 2010) and lower level of stigma (Hernandez et al., 2016). Resilience has also been documented to be associated with the life satisfaction of HCWs during the COVID‐19 pandemic (Bozdağ & Ergün, 2020). It would, therefore, be meaningful to incorporate life satisfaction and stigma into the relationship between resilience and COVID‐19 vaccination intention among HCWs, as they could be important factors involved.

3. THE STUDY

3.1. Aims

The present study investigated the association between resilience and the intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination among Chinese HCWs, and the mediating role of stigma and life satisfaction on the association between resilience and the intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination.

3.2. Sample/participants

The targeted participants were HCWs in mainland China. More specifically, only HCWs who had been employed full‐time since January 2020 (the outbreak of COVID‐19 in China) and who reported having Internet access were included.

3.3. Designs

An anonymous cross‐sectional survey was conducted during October and November 2020. Participants were recruited from five hospitals in four provinces (two in Zhejiang, one in Ningxia, one in Guangxi and one in Yunnan) of mainland China.

3.4. Data collection

All eligible HCWs working in the major departments of the selected hospitals (e.g. internal medicine, surgery, gynaecology and obstetrics, paediatrics, emergency and infectious diseases) were invited to participate in the study. Facilitated by the hospital administrators, prospective participants received an invitation letter via the existing WeChat/QQ groups used for work‐related communications for the respective departments of the selected hospitals; these groups included all HCWs in the departments. The invitation letter contained information about the study's background and the participants were assured of their anonymity, their right to quit at any time, and that return of the completed questionnaire implied informed consent. No incentives were given to the participants. A total of 2703 invitations were sent out and 1733 completed questionnaires were returned. The number of completed responses exceeded the recommended sample size of at least 20 observations for each estimated variable in a hypothesized model (Bentler & Chou, 1987).

3.5. Validity, reliability and rigour

Resilience was assessed by the 10‐item Connor‐Davidson Resilience Scale (Campbell‐Sills & Stein, 2007), which has shown high levels of validity and reliability in the Chinese population with a Cronbach's alpha of over 0.90 (Cheng et al., 2020). Items were rated on a 5‐point Likert Scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 4 (Always). The Cronbach's alpha for this scale in the present study was 0.95.

Stigma was assessed by the 3‐item behavioural dimension of the Stigma Scale‐Short (SSS‐S) form. The Chinese version has been validated with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.80 in mental health consumers (Mak & Cheung, 2010). Participants were asked to rate the extent to which they agreed with each item on a 4‐point Likert scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 4 (Strongly agree). The Cronbach's alpha for this scale in the present study was 0.87.

Life satisfaction was evaluated using the single item Life Satisfaction Measure ‘Are you satisfied with your life as a whole?’ (Cheung & Lucas, 2014). It is an 11‐point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Completely dissatisfied) to 10 (Completely satisfied). This scale has been used in previous research and has shown high levels of validity (e.g. Cheung & Lucas, 2016; Espie et al., 2019).

Intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination was assessed by a single item ‘If the government provides free vaccination services in the first six months of the COVID‐19 vaccine in China, how likely are you to be vaccinated if the vaccine is shown to have 80% effectiveness’. Response ranges from 1 (Very unlikely) to 5 (Very likely). Those who scored 4 or above were classified as having the intention to receive the vaccine.

3.6. Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Survey and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (No. SBRE‐19‐644).

3.7. Data analysis

Descriptive analyses were presented to characterize the study population. First, logistic regressions were conducted to examine the associations between the socio‐demographic variables, the study variables (resilience, stigma and life satisfaction) and the intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination. Then, univariate logistic regressions were performed, and univariate odds ratios (ORu) and respective 95% confidence intervals were derived. Second, adjusting for those socio‐demographic variables with p < .05 in the univariate analysis as candidates, adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and respective 95% confidence intervals were derived. Using all the variables with p < .05 obtained from the univariate analysis as candidates, a summary multiple stepwise logistic regression model was fitted, and multivariate odds ratios (ORm) and respective 95% confidence intervals were derived. The analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0.

The mediation analyses were performed using structural equation modelling (SEM). In SEM, resilience was the independent variable, intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination was the outcome variable, and life satisfaction and stigma were mediators. Socio‐demographic variables that were significant in the logistic regression were also controlled for in the SEM. Bootstrapping analysis based on 2000 samplings was conducted to test the indirect effect. Statistical significance was inferred when the 95% confidence interval didn't include zero. The analyses were performed using Mplus 7.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Descriptive statistics

Of all the participants, the average age was M = 34.16 (SD 9.03) years old; the majority (81.1%) were females; more than two thirds (73.2%) had a bachelor's degree or above; over half (57.5%) were married, and a similar number (59.2%) were nurses. Slightly more than half (56.1%) had primary professional titles. 73.1% of the participants reported that they would be likely to receive the COVID‐19 vaccination. Results from the logistic regression showed that those who were cohabitating were 1.69 times more willing to accept a free vaccination (p < .01). This variable was adjusted for in the subsequent analyses. Other demographic characteristics were not significantly associated with COVID‐19 vaccination intention (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics and association between socio‐demographics and COVID‐19 vaccination intention among health care workers in China (N = 1733)

| Socio‐demographics | COVID‐19 vaccination intention | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N a (%)/mean (SD) | N b (row%) | ORu (95% CI) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 327 (18.9) | 244 (74.6) | 1 |

| Female | 1406 (81.1) | 1022 (72.7) | 0.91 (0.69, 1.19) |

| Age | 34.16 (9.03) | / | 0.99 (0.99, 1.01) |

| Education level | |||

| Secondary or below | 465 (26.8) | 326 (7.1) | 1 |

| Bachelor | 1195 (69.0) | 887 (74.2) | 1.23 (0.97, 1.56) |

| Master or above | 73 (4.2) | 53 (72.6) | 1.13 (0.65, 1.96) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 412 (23.8) | 283 (68.7) | 1 |

| Married | 997 (57.5) | 728 (73.0) | 1.23 (0.96, 1.59) |

| Cohabitation | 324 (18.7) | 255 (78.7) | 1.69 (1.20, 2.36)** |

| Department in hospital | |||

| Internal Medicine | 341 (19.7) | 244 (71.6) | 1 |

| Surgery | 232 (13.4) | 173 (74.6) | 1.17 (0.80, 1.70) |

| Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 80 (4.6) | 52 (65.0) | 0.74 (0.44, 1.24) |

| Paediatrics | 80 (4.6) | 59 (73.8) | 1.12 (0.64, 1.94) |

| Infectious Department | 100 (5.8) | 75 (75.0) | 1.19 (0.72, 1.99) |

| Emergency Department | 50 (2.9) | 39 (78.0) | 1.41 (0.69, 2.87) |

| Intensive Care Unit | 83 (4.8) | 66 (79.5) | 1.54 (0.86, 2.76) |

| Others | 755 (43.6) | 553 (73.2) | 1.09 (0.82, 1.45) |

| Professional titles | |||

| Primary | 972 (56.1) | 719 (74.0) | 1 |

| Middle | 507 (29.3) | 357 (7.4) | 0.84 (0.66, 1.06) |

| Vice‐senior | 154 (8.9) | 116 (75.3) | 1.07 (0.73, 1.59) |

| Senior | 44 (2.5) | 35 (79.5) | 1.37 (0.65, 2.89) |

| Others | 56 (3.2) | 39 (69.6) | 0.81 (0.45, 1.45) |

| Position | |||

| Doctor | 423 (24.4) | 314 (74.2) | 1 |

| Nurse | 1026 (59.2) | 749 (73.0) | 0.94 (0.73, 1.22) |

| Medical technician | 263 (15.2) | 185 (7.3) | 0.82 (0.58, 1.16) |

| Others | 21 (1.2) | 18 (85.7) | 2.08 (0.60, 7.21) |

Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; ORu, univariate odds ratio.

N means the total number of HCWs.

N means the numbers of HCWs who had the intention to receive vaccination.

p < .05.

p < .01.

4.2. Association between study variables and COVID‐19 vaccination intention

The results of the logistic regressions showed that resilience (ORu = 2.06, 95% CI = 1.73 to 2.46) and life satisfaction (ORu = 1.28, 95% CI = 1.201 to 1.36) were also associated with higher levels of intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination, while stigma (ORu = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.67 to 0.92) was associated with lower intention to receive COVID‐19 vaccination. These variables remained significant after adjusting for significant socio‐demographic variables (i.e. marital status). Results from the multiple stepwise regression analysis demonstrated that resilience (ORu = 1.68, 95% CI = 1.38 to 2.03), life satisfaction (ORu = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.10 to 1.26), and stigma (ORu = 0.84, 95% CI = 0.70 to 1.00) were all associated with intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Logistic regression on resilience, stigma, life satisfaction and intention to receive COVID‐19 vaccination among health care professionals in China

| COVID‐19 vaccination intention | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ORu (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | ORm (95% CI) | |

| Resilience | 2.06 (1.73, 2.46)*** | 2.05 (1.72, 2.45)*** | 1.68 (1.38, 2.03)*** |

| Stigma | 0.78 (0.67, 0.92)** | 0.77 (0.65, 0.91)** | 0.84 (0.70, 1.00)* |

| Life satisfaction | 1.28 (1.20, 1.36)*** | 1.28 (1.20, 1.36)*** | 1.18 (1.10, 1.26)*** |

Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; AOR, adjusted OR, odds ratios adjusting for the significant socio‐demographic variable in the univariate analyses; ORm, odds ratio derived from multiple stepwise regression; ORu, univariate odds ratio.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

4.3. SEM analyses for the mediation effect

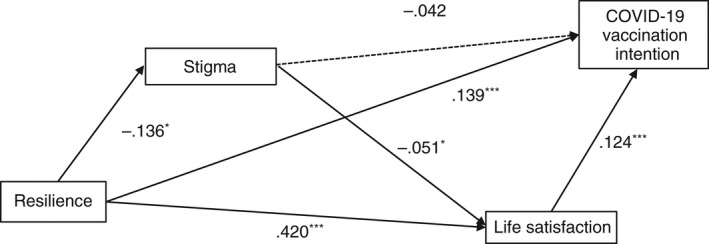

The results of the SEM revealed that resilience was positively related to COVID‐19 vaccination intention (B = 0.139, p < .001) and life satisfaction (B = 0.420, p < .001), and negatively related to stigma (B = 0.136, p < .001). Life satisfaction was positively related to vaccination intention (B = 0.124, p < .001). Stigma was negatively associated with life satisfaction (B = −.051, p < .05) but had no significant association with COVID‐19 vaccination intention (B = −.042, p = n.s.; see Figure 1). The SEM model showed an adequate fit for the large sample of data (χ 2/df = 9.116, CFI = 0.968, TLI = 0.854, RMSEA = 0.068, SRMR = 0.021).

FIGURE 1.

The structural equation model of resilience, stigma, life satisfaction, and COVID‐19 vaccination intention among health care professionals in China. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. The non‐significant path is shown in dotted line

Furthermore, resilience showed a significant total effect on vaccination intention (B = 0.197, 95% CI = 0.151 to 0.243). The direct effect of resilience on COVID‐19 vaccination intention was reduced when resilience and stigma were entered as mediators (B = 0.139, 95% CI = 0.086 to 0.191), indicating a significant mediation effect. Moreover, the total mediation effect was significant (B = 0.059, 95% CI = 0.034 to 0.083), accounting for 30% of the total effect. Specifically, there are two significant paths for the mediation effect. First, there was a significant indirect pathway of Resilience→Life satisfaction→COVID‐19 vaccination intention (B = 0.052, 95% CI = 0.028 to 0.076), accounting for 26% of the total effect. Second, there was another significant indirect pathway of Resilience→Stigma→Life satisfaction→Vaccination intention (B = 0.001, 95% CI = 0.000 to 0.002). This chain mediation effect accounted for 1% of the total effect. The proposed pathway via stigma alone was not supported (B = 0.006, 95% CI = −0.001 to 0.012; see Table 3).

TABLE 3.

The direct and indirect effects between resilience and COVID‐19 vaccination intention among healthcare workers in China

| Effect | B (95% CI) | Relative mediation effect |

|---|---|---|

| Total Resilience→COVID‐19 vaccination intention | 0.197 (0.151–0.243) | |

| Total indirect effect | 0.059 (0.034–0.083) | 30% |

| Specific indirect effect | ||

| Resilience→Life satisfaction→COVID‐19 vaccination intention | 0.052 (0.028–0.076) | 26% |

| Resilience→Stigma→COVID‐19 vaccination intention | 0.006 (−0.001–0.012) | 3% |

| Resilience→Stigma→Life satisfaction→COVID‐19 vaccination intention | 0.001 (0.000–0.002) | 1% |

| Direct Resilience→COVID‐19 vaccination intention | 0.139 (0.086–0.191) | — |

5. DISCUSSION

The COVID‐19 pandemic is undoubtedly one of the most significant stressors in any individual's life, causing serious disruptions and psychological stress. The ability to adjust and negotiate transitions and to adapt to the unprecedented life changes presented by the pandemic is crucial. HCWs play a key role in the containment of COVID‐19 in the community, as patients with COVID‐19 symptoms are most likely to seek help from them. They are constantly at risk of exposure to the COVID‐19 virus and may suffer from significant stress, negative feelings and fears of infecting others. While previous studies have explored the role of resilience in adaptation to change and psychological distress during the COVID‐19 pandemic, there has been less focus on the role of resilience in promoting positive coping behaviours such as uptake of the COVID‐19 vaccination among HCWs. The present study examined the role of resilience on intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination among HCWs in China and identified the mechanisms underlying these associations. First, it is interesting to report that despite the relatively low prevalence of the COVID‐19 pandemic in China, as many as 73.1% of the surveyed HCWs were likely to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination. Such intention is higher than those reported by HCWs in Hong Kong (40%–63%; Kwok et al., 2020; Wang, Pan, et al., 2020) and similar to those HCWs in China (76.4%; Fu et al., 2020), the UK and France (76.2%–76.9%; Butter et al., 2021; Gagneux‐Brunon et al., 2020). The willingness of HCWs to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination has important public health implications as HCWs are important role models for the general public. A high level of intention to receive COVID‐19 vaccination among HCWs is thus key.

5.1. Resilience and COVID‐19 vaccination intention

Resilience signifies a process of positive adaptation in the context of significant adversity. In the present study, resilience was found to be associated with higher levels of intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination. These results are consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated the usefulness of resilience in dealing with various threats and stressful events (Rutter, 2012; Wu et al., 2013). According to the Broaden and Build Theory, HCWs with high levels of resilience are more likely to pursue novel ways of thinking and different behavioural options (Fredrickson, 2001). They are also likely to be more task‐oriented and to actively seek solutions in stressful situations. Receiving a COVID‐19 vaccination can be regarded as a novel and positive coping behaviour with respect to the pandemic. Findings highlight the importance of resilience as an indicator of positive behaviours during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

5.2. Mediation through life satisfaction

The present study also found that resilience was indirectly associated with higher levels of intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination through life satisfaction. Findings lend support to the literature that resilience is linked to positive well‐being (Cohn et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2013). Resilient individuals are more likely to benefit from positive emotionality, which makes them more likely to bounce back from negative experiences. Such positive emotions can help them undo lingering negative emotions, which further promotes life satisfaction (Fredrickson, 2001; Fredrickson et al., 2000; L. Fredrickson & Levenson, 1998). Findings concur with the current evidence about the influence of life satisfaction on health behaviours (Bock et al., 2017; Jo et al., 2003; Lopuszanska‐Dawid, 2018), and also evidence that people who are dissatisfied with their lives report poorer health behaviours such as lower levels of healthy diet, and problematic internet use (Bittó Urbanová et al., 2019). Life satisfaction allows individuals to experience more positive emotions which may broaden one's resources and thoughts and facilitate adaptive cognitive and behavioural coping. Individuals with higher levels of life satisfaction might also be more active in life engagement, therefore exerting higher levels of self‐care, as evidenced by their intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination.

5.3. Mediation through stigma and life satisfaction

Findings of the present study also revealed a second pathway by which resilience was associated with a higher level of intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination. Specifically, higher levels of resilience were sequentially related to lower levels of stigma and increased life satisfaction. This, in turn, was associated with higher levels of intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccine. Findings support the current evidence, suggesting an association between stigma and lower levels of satisfaction (Ramaci et al., 2020), Individuals who are resilient tend to view adversities as inevitable, challenging and manageable. They tend to believe that they can overcome difficult situations and persevere in the face of obstacles. They are therefore more likely to display a more positive view of themself and greater optimism for the future, leading to lower levels of stigma. However, it is important to note that the sequential mediating effect of stigma and life satisfaction on the association between resilience and COVID‐19 vaccination intention was very small. More studies are needed to confirm the impact of stigma on COVID‐19 vaccination intention.

5.4. Implications for practice

Resilience is an important facility for HCWs to deal with various challenges and difficult situations at work. The findings of the present study suggest that promoting resilience may reduce self‐stigma and promote life satisfaction, which, in turn, may motivate HCWs to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination. Building resilience has been advocated as an important strategy for coping with stress and is increasingly recognized as an important asset for healthcare professionals. It is also evident that resilience is influenced by many factors other than merely the individual. Individuals, families, peers, workplace and communities all have an important role in mobilizing the capabilities and nurturing the resilience of healthcare workers. Interventions that promote resilience should take into account the multifaceted nature of resilience.

On an individual level, it is important to promote one's self‐belief and increase personal qualities such as self‐regulation, problem‐solving, motivation to adapt, persistence, competence, optimism and hope. Evidence from other influenza outbreaks suggests that providing appropriate preparation and training for a pandemic, improving adaptive coping strategies such as problem solving, seeking support and reducing avoidance behaviours are useful in promoting resilience for HCWs (Aiello et al., 2011; Maunder et al., 2010). Other strategies that promote resilience, such as cognitive‐behavioural therapy, mindfulness training and computer‐assisted resilience training have also been found to have a positive impact on individual resilience during pandemics (Joyce et al., 2018; Maunder et al., 2010). It is advised that HCWs are provided with such resilience training, especially during pandemics.

On an interpersonal level, there is ample evidence that promoting close relationships, social support and sense of connectedness are important pathways by which resilience can be increased (Dumont & Provost, 1999; Landau, 2007; Scarf et al., 2017; Sippel et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2018). A sense of connectedness with colleagues may be particularly critical for HCWs, as they may perceive that their stressors are unique and cannot be understood by ‘outsiders’ (Albott et al., 2020). Interventions to promote resilience among HCWs should therefore facilitate social support and relationships in their organizations, and instil confidence that they will be supported by their organization (Heath et al., 2020). A review study has found that among all the interventions for resilience among hospital staff, one‐on‐one discussion with colleagues and informal social mechanisms outside of the hospital were most frequently used and reported to be most impactful by the respondents (Lee et al., 2015). Organizations should seek to provide venues for both formal and informal exchange among colleagues.

The influence of the work environment was evidently a key factor in promoting resilience. Workplace related factors, such as lack of control over schedules, long working hours, huge workloads, lack of quality sleep, lack of autonomy at work, and not feeling valued in the workplace are all significant risk predictors for stress and resilience (Bozdağ & Ergün, 2020; Yu et al., 2019). Workplaces should foster autonomy at work, provide opportunities for development, a healthy work environment, a reasonable workload and improved communication (Heath et al., 2020; Pipe et al., 2012). Clear workplace strategies to achieve increased resilience should be established in an organization.

5.5. Limitations

The study was subject to some limitations. First, it was cross‐sectional in nature so no causality between the variables can be assumed. Second, the data were only obtained from five hospitals in four provinces so it might not be representative of the whole HCW population in mainland China. Third, participants were self‐selected and self‐reported measures were used, therefore the intention to receive COVID‐19 vaccination might have been overestimated. Fourth, due to issues with the length of the questionnaire, a single item was used to measure life satisfaction and intention to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination. The validity of these measures, therefore, needs to be considered. Finally, other factors, such as beliefs in vaccine safety and efficacy, and previous experience with vaccines, might also impact the vaccination intention of HCWs but were not included in the present study.

6. CONCLUSIONS

The present study reveals that resilience played a significant role both directly and indirectly in the intention of HCWS to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination, by reducing stigma and increasing life satisfaction. Promoting the resilience of HCWs could increase the COVID‐19 vaccination uptake rate among HCWs in China. Interventions that promote the COVID‐19 vaccination among HCWs should be considered to improve their resilience on individual, interpersonal and organizational levels.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Phoenix K. H. Mo, Rui She, Yanqiu Yu, Joseph T. F. Lau; Investigation: Lijuan Li, Qian Yang, Jianyan Lin, Xiaoli Ye, Suliu Wu, Z.Y., S.G., Jianxin Zhang; Supervision: Joseph T. F. Lau; Writing: original draft, Phoenix K. H. Mo, Huahua Hu, Luyao Xie; Writing: review and editing, Joseph T. F. Lau All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/jan.15143.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Ling Guo of Kunming Fourth People's Hospital, Lingling Ma of No. 3 Hospital of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, Wenyi Dong, Yingxing Nong, Beibei Gong of the Fourth People's Hospital of Nanning, Ying Yang of the Children's Hospital Zhejiang University School of Medicine for their assistance in data collection.

Mo, P. K. H. , She, R. , Yu, Y. , Li, L. , Yang, Q. , Lin, J. , Ye, X. , Wu, S. , Yang, Z. , Guan, S. , Zhang, J. , Hu, H. , Xie, L. , & Lau, J. T. F. (2022). Resilience and intention of healthcare workers in China to receive a COVID‐19 vaccination: The mediating role of life satisfaction and stigma. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78, 2327–2338. 10.1111/jan.15143

Funding information

The study was supported by the internal research funding of the Centre for Health Behaviour Research, the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Authors do not wish to share the data.

REFERENCES

- Abdel Wahed, W. Y. , Hefzy, E. M. , Ahmed, M. I. , & Hamed, N. S. (2020). Assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and perception of health care workers regarding COVID‐19, a cross‐sectional study from Egypt. Journal of Community Health, 45(6), 1242–1251. 10.1007/s10900-020-00882-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiello, A. , Khayeri, M.‐E. , Raja, S. , Peladeau, N. , Romano, D. , Leszcz, M. , Maunder, R. G. , Rose, M. , Adam, M. A. , Pain, C. , Moore, A. , Savage, D. , & Schulman, R. B. (2011). Resilience training for hospital workers in anticipation of an influenza pandemic. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 31(1), 15–20. 10.1002/chp.20096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón, R. , Cerezo, M. V. , Hevilla, S. , & Blanca, M. J. (2020). Psychometric properties of the Connor‐Davidson Resilience Scale in women with breast cancer. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 20(1), 81–89. 10.1016/j.ijchp.2019.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albott, C. S. , Wozniak, J. R. , McGlinch, B. P. , Wall, M. H. , Gold, B. S. , & Vinogradov, S. (2020). Battle buddies: Rapid deployment of a psychological resilience intervention for health care workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almutairi, A. F. , Adlan, A. A. , Balkhy, H. H. , Abbas, O. A. , & Clark, A. M. (2018). "It feels like I'm the dirtiest person in the world.": Exploring the experiences of healthcare providers who survived MERS‐CoV in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 11(2), 187–191. 10.1016/j.jiph.2017.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang, S. Y. , Uthaman, T. , Ayre, T. C. , Lim, S. H. , & Lopez, V. (2019). Differing pathways to resiliency: A grounded theory study of enactment of resilience among acute care nurses. Nursing & Health Sciences, 21(1), 132–138. 10.1111/nhs.12573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arda, B. , Durusoy, R. , Yamazhan, T. , Sipahi, O. R. , Taşbakan, M. , Pullukçu, H. , Erdem, E. , & Ulusoy, S. (2011). Did the pandemic have an impact on influenza vaccination attitude? A survey among health care workers. BMC Infectious Diseases, 11(1), 1–8. 10.1186/1471-2334-11-87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y. , Lin, C. C. , Lin, C. Y. , Chen, J. Y. , Chue, C. M. , & Chou, P. (2004). Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatric Services, 55(9), 1055–1057. 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P. M. , & Chou, C.‐P. (1987). Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research, 16(1), 78–117. 10.1177/0049124187016001004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bittó Urbanová, L. , Holubcikova, J. , Geckova, A. , Reijneveld, S. A. , & Dijk, J. P. (2019). Does life satisfaction mediate the association between socioeconomic status and excessive internet use? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, 3914. 10.3390/ijerph16203914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake, H. , Bermingham, F. , Johnson, G. , & Tabner, A. (2020). Mitigating the psychological impact of COVID‐19 on healthcare workers: A digital learning package. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 17(9), 2997. 10.3390/ijerph17092997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock, J.‐O. , Hajek, A. , & König, H.‐H. (2017). Psychological determinants of influenza vaccination. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 194. 10.1186/s12877-017-0597-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozdağ, F. , & Ergün, N. (2020). Psychological resilience of healthcare professionals during COVID‐19 pandemic. Psychological Reports, 124(6), 2567–2586. 10.1177/0033294120965477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butter, S. , McGlinchey, E. , Berry, E. , & Armour, C. (2021). Psychological, social, and situational factors associated with COVID‐19 vaccination intentions: A study of UK key workers and non‐key workers. British Journal of Health Psychology. 10.1111/bjhp.12530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell‐Sills, L. , & Stein, M. B. (2007). Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor‐Davidson resilience scale (CD‐RISC): Validation of a 10‐item measure of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(6), 1019–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C. , Dong, D. , He, J. , Zhong, X. , & Yao, S. (2020). Psychometric properties of the 10‐item Connor‐Davidson Resilience Scale (CD‐RISC‐10) in Chinese undergraduates and depressive patients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 261, 211–220. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, F. , & Lucas, R. E. (2014). Assessing the validity of single‐item life satisfaction measures: Results from three large samples. Quality of Life Research, 23(10), 2809–2818. 10.1007/s11136-014-0726-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, F. , & Lucas, R. E. (2016). Income inequality is associated with stronger social comparison effects: The effect of relative income on life satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110(2), 332–341. 10.1037/pspp0000059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, M. A. , Fredrickson, B. L. , Brown, S. L. , Mikels, J. A. , & Conway, A. M. (2009). Happiness unpacked: Positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion, 9(3), 361–368. 10.1037/a0015952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan, P. W. , Larson, J. E. & Kuwabara, S. A. (2010). Social psychology of the stigma of mental illness: Public and self‐stigma models.

- Corrigan, P. W. , Watson, A. C. , & Barr, L. (2006). The self–stigma of mental illness: Implications for self–esteem and self–efficacy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25(8), 875–884. 10.1521/jscp.2006.25.8.875 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey, A. F. , Pyrznawoski, J. , Lockhart, S. , Barnard, J. , Campagna, E. J. , Garrett, K. , Fisher, A. , Dickinson, L. M. , & O’Leary, S. T. (2018). Effect of a health care professional communication training intervention on adolescent human papillomavirus vaccination: A cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(5), e180016. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detoc, M. , Bruel, S. , Frappe, P. , Tardy, B. , Botelho‐Nevers, E. , & Gagneux‐Brunon, A. (2020). Intention to participate in a COVID‐19 vaccine clinical trial and to get vaccinated against COVID‐19 in France during the pandemic. Vaccine, 38(45), 7002–7006. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devakumar, D. , Shannon, G. , Bhopal, S. S. , & Abubakar, I. (2020). Racism and discrimination in COVID‐19 responses. Lancet, 395(10231), 1194. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30792-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. , Suh, E. M. , Lucas, R. E. , & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well‐being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302. 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dror, A. A. , Eisenbach, N. , Taiber, S. , Morozov, N. G. , Mizrachi, M. , Zigron, A. , Srouji, S. , & Sela, E. (2020). Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID‐19. European Journal of Epidemiology, 35(8), 775–779. 10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, M. , & Provost, M. A. (1999). Resilience in adolescents: Protective role of social support, coping strategies, self‐esteem, and social activities on experience of stress and depression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28(3), 343–363. 10.1023/a:1021637011732 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espie, C. A. , Emsley, R. , Kyle, S. D. , Gordon, C. , Drake, C. L. , Siriwardena, A. N. , Cape, J. , Ong, J. C. , Sheaves, B. , Foster, R. , Freeman, D. , Costa‐Font, J. , Marsden, A. , & Luik, A. I. (2019). Effect of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on health, psychological well‐being, and sleep‐related quality of life: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(1), 21–30. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, L. S. , Mansergh, G. , Lynch, J. , & Santibanez, S. (2019). Addressing disease‐related stigma during infectious disease outbreaks. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 13(5–6), 989–994. 10.1017/dmp.2018.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden‐and‐build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B. L. , & Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well‐being. Psychological Science, 13(2), 172–175. 10.1111/1467-9280.00431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B. L. , Mancuso, R. A. , Branigan, C. , & Tugade, M. M. (2000). The undoing effect of positive emotions. Motivation and Emotion, 24(4), 237–258. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3128334/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, C. , Wei, Z. , Pei, S. , Li, S. , Sun, X. , & Liu, P. (2020). Acceptance and preference for COVID‐19 vaccination in health‐care workers (HCWs). medRxiv. 10.1101/2020.04.09.20060103 [DOI]

- Gagneux‐Brunon, A. , Detoc, M. , Bruel, S. , Tardy, B. , Rozaire, O. , Frappe, P. , & Botelho‐Nevers, E. (2020). Intention to get vaccinations against COVID‐19 in French healthcare workers during the first pandemic wave: A cross sectional survey. Journal of Hospital, 108. 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan, W. H. , Lim, J. W. , & Koh, D. (2020). Preventing intra‐hospital infection and transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 in health‐care workers. Safety and Health at Work, 11(2), 241–243. 10.1016/j.shaw.2020.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Q. , Bao, L. , Mao, H. , Wang, L. , Xu, K. , Yang, M. , Li, Y. , Zhu, L. , Wang, N. , Lv, Z. , Gao, H. , Ge, X. , Kan, B. , Yaling, H. U. , Liu, J. , Cai, F. , Jiang, D. , Yin, Y. , Qin, C. , … Qin, C. (2020). Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate for SARS‐CoV‐2. Science, 369(6499), 77–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godderis, L. , Boone, A. , & Bakusic, J. (2020). COVID‐19: a new work‐related disease threatening healthcare workers. Occupational Medicine, 70(5), 315–316. 10.1093/occmed/kqaa056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grech, V. , Bonnici, J. , & Zammit, D. (2020). Vaccine hesitancy in Maltese family physicians and their trainees vis‐à‐vis influenza and novel COVID‐19 vaccination. Early Human Development, 105259. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, N. , Docherty, M. , Gnanapragasam, S. , & Wessely, S. (2020). Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid‐19 pandemic. BMJ, 368, m1211. 10.1136/bmj.m1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habersaat, K. B. , Betsch, C. , Danchin, M. , Sunstein, C. R. , Böhm, R. , Falk, A. , Brewer, N. T. , Omer, S. B. , Scherzer, M. , Sah, S. , Fischer, E. F. , Scheel, A. E. , Fancourt, D. , Kitayama, S. , Dubé, E. , Leask, J. , Dutta, M. , MacDonald, N. E. , Temkina, A. , … Butler, R. (2020). Ten considerations for effectively managing the COVID‐19 transition. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(7), 677–687. 10.1038/s41562-020-0906-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart, P. L. , Brannan, J. D. , & De Chesnay, M. (2014). Resilience in nurses: An integrative review. Journal of Nursing Management, 22(6), 720–734. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01485.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath, C. , Sommerfield, A. , & von Ungern‐Sternberg, B. (2020). Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A narrative review. Anaesthesia, 75(10), 1364–1371. 10.1111/anae.15180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, S. H. A. , Morgan, B. J. , & Parshall, M. B. (2016). Resilience, stress, stigma, and barriers to mental healthcare in U.S. air force nursing personnel. Nursing Research, 65(6), 481–486. 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H. R. , Chen, C. W. , Chen, C. M. , Yang, H. L. , Su, W. J. , Wang, J. K. , & Tsai, P. K. (2018). A positive perspective of knowledge, attitude, and practices for health‐promoting behaviors of adolescents with congenital heart disease. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 17(3), 217–225. 10.1177/1474515117728609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo, H. , Lee, S. , Ahn, M. O. , & Jung, S. H. (2003). Structural relationship of factors affecting health promotion behaviors of Korean urban residents. Health Promotion International, 18(3), 229–236. 10.1093/heapro/dag018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D. S. (2020). History in a crisis—Lessons for Covid‐19. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(18), 1681–1683. 10.1056/NEJMp2004361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, S. , Shand, F. , Tighe, J. , Laurent, S. J. , Bryant, R. A. , & Harvey, S. B. (2018). Road to resilience: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of resilience training programmes and interventions. British Medical Journal Open, 8(6), e017858. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabamba Nzaji, M. , Kabamba Ngombe, L. , Ngoie Mwamba, G. , Banza Ndala, D. B. , Mbidi Miema, J. , Luhata Lungoyo, C. , Lora Mwimba, B. , Cikomola Mwana Bene, A. , & Mukamba Musenga, E. (2020). Acceptability of vaccination against COVID‐19 among healthcare workers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Pragmatatic and Observational Research, 11, 103–109. 10.2147/por.s271096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato, A. , Fujimaki, Y. , Fujimori, S. , Isogawa, A. , Onishi, Y. , Suzuki, R. , Yamauchi, T. , Ueki, K. , Kadowaki, T. , & Hashimoto, H. (2016). Association between self‐stigma and self‐care behaviors in patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross‐sectional study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care, 4(1), e000156. 10.1136/bmjdrc-2015-000156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimhi, S. , Marciano, H. , Eshel, Y. , & Adini, B. (2020). Resilience and demographic characteristics predicting distress during the COVID‐19 crisis. Social Science & Medicine, 265, 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer, K. L. (1999). Factors and processes contributing to resilience: The resilience framework. In Glantz M. D. & Johnson J. L. (Eds.), Resilience and development: Positive life adaptations (pp. 179–224). Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kwok, K. O. , Li, K. K. , Wei, W. I. , Tang, A. , Wong, S. Y. S. , & Lee, S. S. (2020). Influenza vaccine uptake, COVID‐19 vaccination intention and vaccine hesitancy among nurses: A survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 103854. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L. Fredrickson, B. , & Levenson, R. W. (1998). Positive emotions speed recovery from the cardiovascular sequelae of negative emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 12(2), 191–220. 10.1080/026999398379718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J. , Ma, S. , Wang, Y. , Cai, Z. , Hu, J. , Wei, N. , Wu, J. , Du, H. , Chen, T. , Li, R. , Tan, H. , Kang, L. , Yao, L. , Huang, M. , Wang, H. , Wang, G. , Liu, Z. , & Hu, S. (2020). Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Network Open, 3(3), e203976. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancet, T. (2020). COVID‐19: Protecting health‐care workers. Lancet, 395(10228), 922. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30644-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau, J. (2007). Enhancing resilience: Families and communities as agents for change. Family Process, 46(3), 351–365. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2007.00216.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson, H. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers and their patients in Europe: A qualitative study. ECDC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. J. , Forbes, M. L. , Lukasiewicz, G. J. , Williams, T. , Sheets, A. , Fischer, K. , & Niedner, M. F. (2015). Promoting staff resilience in the pediatric intensive care unit. American Journal of Critical Care, 24(5), 422–430. 10.4037/ajcc2015720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopuszanska‐Dawid, M. (2018). Life satisfaction as a health determinant among Polish adult population. Anthropologischer Anzeiger, 75(3), 175–184. 10.1127/anthranz/2018/0814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar, S. S. , Cicchetti, D. , & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562. 10.1111/1467-8624.00164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.‐C. , Chang, H.‐J. , Liu, Y.‐M. , Hsieh, H.‐L. , Lo, L. , Lin, M.‐Y. , & Lu, K.‐C. (2013). The relationship between health‐promoting behaviors and resilience in patients with chronic kidney disease. The Scientific World Journal, 2013, 1–7. 10.1155/2013/124973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak, W. W. , & Cheung, R. Y. (2010). Self‐stigma among concealable minorities in Hong Kong: Conceptualization and unified measurement. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80(2), 267–281. 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01030.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzano García, G. , & Ayala Calvo, J. C. (2012). Emotional exhaustion of nursing staff: Influence of emotional annoyance and resilience. International Nursing Review, 59(1), 101–107. 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2011.00927.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matos, P. S. , Neushotz, L. A. , Griffin, M. T. , & Fitzpatrick, J. J. (2010). An exploratory study of resilience and job satisfaction among psychiatric nurses working in inpatient units. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 19(5), 307–312. 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2010.00690.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunder, R. , Lancee, W. , Balderson, K. , Bennett, J. , Borgundvaag, B. , Evans, S. , Fernandes, C. , Goldbloom, D. , Gupta, M. , Hunter, J. , McGillis Hall, L. , Nagle, L. , Pain, C. , Peczeniuk, S. , Raymond, G. , Read, N. , Rourke, S. , Steinberg, R. , Stewart, T. , … Wasylenki, D. (2006). Long‐term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 12(12), 1924–1932. 10.3201/eid1212.060584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunder, R. G. , Lancee, W. J. , Mae, R. , Vincent, L. , Peladeau, N. , Beduz, M. A. , Hunter, J. J. , & Leszcz, M. (2010). Computer‐assisted resilience training to prepare healthcare workers for pandemic influenza: A randomized trial of the optimal dose of training. BMC Health Services Research, 10(1), 1–10. 10.1186/1472-6963-10-72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAteer, J. , Yildirim, I. , & Chahroudi, A. (2020). The VACCINES act: Deciphering vaccine hesitancy in the time of COVID‐19. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 71(15), 703–705. 10.1093/cid/ciaa433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mereckiene, J. , Cotter, S. , Nicoll, A. , Lopalco, P. , Noori, T. , Weber, J. , D’Ancona, F. , Levy‐Bruhl, D. , Dematte, L. , Giambi, C. , Valentiner‐Branth, P. , Stankiewicz, I. , Appelgren, E. , Flanagan, D. O. ; VENICE Project Gatekeepers Group . (2014). Seasonal influenza immunisation in Europe. Overview of recommendations and vaccination coverage for three seasons: Pre‐pandemic (2008/09), pandemic (2009/10) and post‐pandemic (2010/11). Eurosurveillance, 19(16), 20780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, A. , Sabry, W. , & Mostafa, N. S. (2020). COVID‐19‐related stigmatization among a sample of Egyptian healthcare workers. PLoS One, 15(12), e0244172. 10.1371/journal.pone.0244172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuño, M. , Chowell, G. , & Gumel, A. B. (2007). Assessing the role of basic control measures, antivirals and vaccine in curtailing pandemic influenza: Scenarios for the US, UK and the Netherlands. Journal of the Royal Society, Interface, 4(14), 505–521. 10.1098/rsif.2006.0186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padron‐Regalado, E. (2020). Vaccines for SARS‐CoV‐2: Lessons from other coronavirus strains. Infectious Diseases and Therapy, 9(2), 255–274. 10.1007/s40121-020-00300-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, C. , Hwang, J. M. , Jo, S. , Bae, S. J. , & Sakong, J. (2020). COVID‐19 outbreak and its association with healthcare workers’ emotional stress: A cross‐sectional study. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 35(41), e372. 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe, E. A. , & Smart Richman, L. (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta‐analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135(4), 531–554. 10.1037/a0016059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson, P. , Meurice, F. , Stanberry, L. R. , Glismann, S. , Rosenthal, S. L. , & Larson, H. J. (2016). Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine, 34(52), 6700–6706. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pipe, T. B. , Buchda, V. L. , Launder, S. , Hudak, B. , Hulvey, L. , Karns, K. E. , & Pendergast, D. (2012). Building personal and professional resources of resilience and agility in the healthcare workplace. Stress and Health, 28(1), 11–22. 10.1002/smi.1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaci, T. , Barattucci, M. , Ledda, C. , & Rapisarda, V. (2020). Social stigma during COVID‐19 and its impact on HCWs outcomes. Sustainability, 12(9), 3834. 10.3390/su12093834 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch, N. , Angermeyer, M. C. , & Corrigan, P. W. (2005). Mental illness stigma: Concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. European Psychiatry, 20(8), 529–539. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch, N. , Corrigan, P. W. , Todd, A. R. , & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2010). Implicit self‐stigma in people with mental illness. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 198(2), 150–153. 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181cc43b5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, M. (2012). Resilience as a dynamic concept. Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 335–344. 10.1017/s0954579412000028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarf, D. , Hayhurst, J. G. , Riordan, B. C. , Boyes, M. , Ruffman, T. , & Hunter, J. A. (2017). Increasing resilience in adolescents: The importance of social connectedness in adventure education programmes. Australasian Psychiatry, 25(2), 154–156. 10.1177/1039856216671668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sippel, L. M. , Pietrzak, R. H. , Charney, D. S. , Mayes, L. C. , & Southwick, S. M. (2015). How does social support enhance resilience in the trauma‐exposed individual? Ecology and Society, 20(4). 10.5751/ES-07832-200410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siu, J. Y. (2008). The SARS‐associated stigma of SARS victims in the post‐SARS era of Hong Kong. Qualitative Health Research, 18(6), 729–738. 10.1177/1049732308318372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuber, J. , Meyer, I. , & Link, B. (2008). Stigma, prejudice, discrimination and health. Social Science and Medicine, 67(3), 351–357. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turenne, C. P. , Gautier, L. , Degroote, S. , Guillard, E. , Chabrol, F. , & Ridde, V. (2019). Conceptual analysis of health systems resilience: A scoping review. Social Science and Medicine, 232, 168–180. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma, S. , Mythily, S. , Chan, Y. H. , Deslypere, J. P. , Teo, E. K. , & Chong, S. A. (2004). Post‐SARS psychological morbidity and stigma among general practitioners and traditional Chinese medicine practitioners in Singapore. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, 33(6), 743–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. , Pan, R. , Wan, X. , Tan, Y. , Xu, L. , Ho, C. S. , & Ho, R. C. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID‐19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1729. 10.3390/ijerph17051729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K. , Wong, E. L. Y. , Ho, K. F. , Cheung, A. W. L. , Chan, E. Y. Y. , Yeoh, E. K. , & Wong, S. Y. S. (2020). Intention of nurses to accept coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination and change of intention to accept seasonal influenza vaccination during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A cross‐sectional survey. Vaccine, 38(45), 7049–7056. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. , Tao, H. , Bowers, B. J. , Brown, R. , & Zhang, Y. (2018). Influence of social support and self‐efficacy on resilience of early career registered nurses. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 40(5), 648–664. 10.1177/0193945916685712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G. , Feder, A. , Cohen, H. , Kim, J. J. , Calderon, S. , Charney, D. S. , & Mathé, A. A. (2013). Understanding resilience. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 7, 10. 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F. , Raphael, D. , Mackay, L. , Smith, M. , & King, A. (2019). Personal and work‐related factors associated with nurse resilience: A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 93, 129–140. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Authors do not wish to share the data.