Abstract

Utilization of a range of carbohydrates for growth by the hyperthermophile Pyrococcus furiosus was investigated by examining the spectrum of glycosyl hydrolases produced by this microorganism and the thermal labilities of various saccharides. Previously, P. furiosus had been found to grow in batch cultures on several α-linked carbohydrates and cellobiose but not on glucose or other β-linked sugars. Although P. furiosus was not able to grow on any nonglucan carbohydrate or any form of cellulose in this study (growth on oat spelt arabinoxylan was attributed to glucan contamination of this substrate), significant growth at 98°C occurred on β-1,3- and β-1,3–β-1,4-linked glucans. Oligosaccharides generated by digestion with a recombinant laminarinase derived from P. furiosus were the compounds that were most effective in stimulating growth of the microorganism. In several cases, periodic addition of β-glucan substrates to fed-batch cultures limited adverse thermochemical modifications of the carbohydrates (i.e., Maillard reactions and caramelization) and led to significant increases (as much as two- to threefold) in the cell yields. While glucose had only a marginally positive effect on growth in batch culture, the final cell densities nearly tripled when glucose was added by the fed-batch procedure. Nonenzymatic browning reactions were found to be significant at 98°C for saccharides with degrees of polymerization (DP) ranging from 1 to 6; glucose was the most labile compound on a mass basis and the least labile compound on a molar basis. This suggests that for DP of 2 or greater protection of the nonreducing monosaccharide component may be a factor in substrate availability. For P. furiosus, carbohydrate utilization patterns were found to reflect the distribution of the glycosyl hydrolases which are known to be produced by this microorganism.

As the biocatalytic repertoire of hyperthermophilic microorganisms continues to be revealed by a variety of methods (1, 5, 39), it is expected that additional insights into the physiological bases for growth at extremely high temperatures will result. In this regard, it is interesting to consider the carbon and energy sources that are utilized by specific hyperthermophiles in light of the enzymatic machinery available to recruit and utilize these compounds. In the case of Pyrococcus furiosus, a hyperthermophilic archaeon that grows optimally at about 100°C, the initial reports indicated that the organism grew on peptide-based media and that growth was stimulated in the presence of α-linked polysaccharides, such as starch and maltose (14). No growth was observed on several carbohydrates, including glucose, galactose, sorbose, ribose, arabinose, xylose, sucrose, lactose, raffinose, mannitol, xylitol, and gluconate (14). Subsequent studies showed that P. furiosus contains a number of α-specific glycosyl hydrolases (7, 8, 11, 12, 26, 31, 33) which play a role in the utilization of α-linked carbohydrates. These hydrolases ultimately provide glucose as a carbon and energy source for P. furiosus, which has been shown to ferment this monosaccharide (40) by a modified Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway involving ADP-dependent kinases (27, 29). It is interesting that P. furiosus has been reported to not grow on glucose (14); this characteristic is probably related to the thermal lability of glucose in the chemical environment used for cultivation of this organism. However, glucose uptake by resting cells has been observed (40, 42). The manner in which P. furiosus acquires glucose for anabolic and catabolic purposes likely involves strategic use of enzymatically catalyzed reactions in order to minimize detrimental side reactions.

Until recently, the only β-linked carbohydrate known to support growth of P. furiosus was cellobiose, which is consistent with the presence of an intracellular β-glucosidase in this organism (28). However, the presence of additional β-specific glycosyl hydrolases in P. furiosus (5) suggests that growth is possible with other β-linked polysaccharides. Indeed, the genes encoding a β-mannosidase (4), a laminarinase (18), and an endoglucanase (3) in P. furiosus have been identified, and recombinant versions of these enzymes have been characterized biochemically.

There are several questions concerning the utilization of carbohydrates as carbon and energy sources by P. furiosus and other hyperthermophilic organisms. These questions include the origin of the compounds in geothermal environments, the range of and preference for carbohydrates that support growth, and the lability of the compounds at high temperatures. These issues are considered here for P. furiosus based on the available information concerning the biocatalytic capability for carbohydrate hydrolysis by this organism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sources of materials.

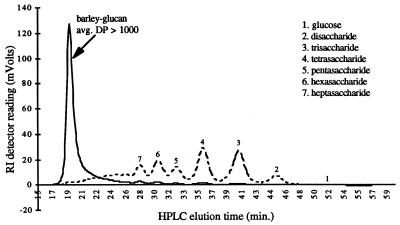

A variety of carbohydrates were included in the growth media used for P. furiosus. These carbohydrates included glucans (gluocose, maltose, cellobiose, laminarin, lichenan, carboxymethyl cellulose, and cellulose [type 20]), oat spelt arabinoxylan, locust bean gum, chitin, and carrageenan (types I and II) purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). Other carbohydrates used in this study were pachyman, barley glucan, wheat arabinoxylan, birchwood arabinoxylan, ivory nut mannan, galactomannan, and pectin purchased from Megazyme (Bray, County Wicklow, Ireland). Cellooligosaccharides and laminarioligosaccharides were obtained by enzymatic digestion of barley glucan (β-1,3–β-1,4 mixed-linkage glucan) and laminarin (β-1,3-linked glucan), respectively, with a laminarinase (18) from P. furiosus during batch and fed-batch experiments. Most of the oligosaccharides formed had degrees of polymerization (DP) of 2 to 7, as determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with an Aminex HPX-42A column (Fig. 1). The amount of laminarinase used for digestion was determined by monitoring the oligosaccharide content at several time points (20 min and 5 h, as shown in Fig. 1) and choosing the enzyme level which resulted in a spectrum of oligosaccharides (predominantly 2 < DP < 7) after 5 h. The amount of enzyme used was 1 μg/ml or less.

FIG. 1.

Product distribution resulting from degradation of barley glucan to oligosaccharides. Short-term hydrolysis and long-term hydrolysis of barley glucan are indicated by the solid and dotted lines, respectively. A spectrum of oligosaccharides with DP ranging from ≥2 to ≤7 were the predominant sugar residues generated. The void volume of the Aminex HPX-42A HPLC column was approximately 3.8 ml, which corresponded to an elution time of 19 min. RI, refractive index.

Growth of the microorganism.

P. furiosus DSM 3638 was obtained from Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen, Braunschweig, Germany. Cells were grown in artificial seawater (ASW) supplemented with yeast extract (0 to 5.0 g/liter), tryptone (5 g/liter), and resazurin (2.5 ml/liter from a 0.4-g/liter stock solution) as a redox indicator, as well as specific carbohydrates. ASW contained (per liter) 23.9 g of NaCl, 4.0 g of Na2SO4, 0.7 g of KCl, 0.2 g of NaHCO3, 0.1 g of KBr, 0.03 g of H3BO3, 10.8 g of MgCl2 · 6H2O, 1.5 g of CaCl2 · 2H2O, and 0.025 g of SrCl2 · 6H2O. Seventy milliliters of medium was added to a 100-ml culture bottle, the bottle was placed in a 98°C oil bath for 45 min, and then a carbohydrate was added. Then 250 μl of an aqueous sodium sulfide solution (100 g/liter) or 250 μl of a mixture containing 50 g of sodium sulfide per liter and 50 g of cysteine per liter was added. The bottle was sparged with inert gas (N2) until the solution became colorless. The bottle was then inoculated with 2.5 ml of a previously grown culture, sealed with a aluminum crimp cap, and placed in a 98°C shaking oil bath for approximately 10 h. Samples (1 ml) for cell enumeration were taken periodically; each sample was preserved with 100 μl of a 2.5% (wt/vol) glutaraldehyde solution and then viewed by epifluorescent microscopy as described elsewhere (38).

For the carbohydrates tested, growth was defined as significant when the maximum cell density (MCD) was at least twice that of the control. The MCD was determined after five transfers of cells grown in the presence of 5 g of carbohydrate per liter and 5 g of yeast extract per liter. Then additional transfers of cells were made, and with each transfer the concentration of yeast extract was reduced by 1 g/liter. After five transfers, reduced medium (RM) conditions were obtained. Three additional transfers were then made under RM conditions with medium containing 5 g of carbohydrate per liter, after which the final determination of whether significant growth had occurred was made.

Fed-batch experiments.

The approach used for the fed-batch experiments was the same as the approach used for the batch growth experiments, except that an additional 1 g of carbohydrate (from a 150-g/liter stock solution) per liter was added to the culture medium every hour for 10 h in addition to the initial 5 g of carbohydrate per liter. Slurry mixtures containing less soluble carbohydrate stocks (e.g., cellulose) were mixed extensively before they were added to a culture.

Analysis of browning reactions.

A refractive index detector (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) was used to monitor the equal molar equivalents of the various oligosaccharides based on the approach described by Buera and coworkers (9, 10). High-purity oligosaccharide standards were purchased from Seikagaku (Tokyo, Japan). Elution peak areas were calculated with HPLC Millenium software (Water Corp., Milford, Mass.). Compared to oligosaccharide standards not exposed to 98°C, additional peak areas due to browning were determined for each oligosaccharide incubated at 98°C for various times. The resulting slope (the rate at which additional peak area was generated per incubation time) for each oligosaccharide was used to quantify the extent of browning.

RESULTS

Medium development.

In order to examine utilization of specific carbohydrates by P. furiosus, it was necessary to develop a medium lacking yeast extract because yeast extract contains some carbohydrate. To do this, a peptide source (5 g of tryptone per liter) was included in the medium; densities of approximately 107 cells/ml were obtained when peptides were added to a sulfur-free medium lacking carbohydrates. The benefit of adding specific carbohydrates to this medium could then be determined. P. furiosus is known to produce an extracellular laminarinase (18) and an extracellular endoglucanase (3), which process larger polysaccharides prior to intracellular transport (14). The laminarinase was used to produce β-1,4 and β-1,3 oligosaccharides in situ by degrading barley β-glucan, a β-1,3–β-1,4 mixed-linkage glucan polysaccharide with an average chain length of more than 1,000 glucose residues (16, 17), and laminarin, a β-1,3-linked polysaccharide with an average chain length of 25 glucose residues (37), respectively. The results of a typical HPLC analysis of degradation of barley glucan to oligosaccharides in an uninoculated control are shown in Fig. 1, which indicates that the predominant products had DP of 2 to 7. This distribution is consistent with results reported previously for degradation of starch by P. furiosus amylase (31).

Growth on non-β-glucan substrates.

Significant growth occurred on only one of the non-β-glucan substrates tested, oat spelt arabinoxylan. No growth was detected on locust bean gum, chitin, carrageenan (types I and II), wheat arabinoxylan, birchwood arabinoxylan, ivory nut mannan, galactomannan, or pectin. Table 1 shows the MCDs obtained for each passage of cells in the presence of 5 g of oat spelt arabinoxylan per liter and in the presence of maltose (for comparison) and for a control containing no added carbohydrate. The oat spelt arabinoxylan findings were interesting because no significant growth was observed with the other two xylan substrates, wheat arabinoxylan and birchwood xylan, which are structurally similar to oat spelt arabinoxylan. However, when the contents of oat spelt arabinoxylan were analyzed, as much as 15% glucose-containing residues were present as contaminants. Thus, the presence of extracellular glucanases, rather than the presence of xylanases, apparently was responsible for the growth on oat spelt arabinoxylan. To test whether a glucanase can release glucose or glucans from oat spelt arabinoxylan, a glucose oxidase assay was used to determine the total amount of glucose released after incubation with a hyperthermophilic β-1,4 endoglucanase (3). Indeed, significant amounts of glucose were present (data not shown). Thus, P. furiosus growth on oat spelt arabinoxylan was attributed to degradation of the contaminating glucans present in this commercial product.

TABLE 1.

P. furiosus growth on maltose and oat spelt arabinoxylana

| Transfer no.b | Cell density (cells/ml) with:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| No sugar (control) | Maltose (5 g/liter) | Oat spelt arabinoxylan (5 g/liter) | |

| 1 | 1.9 × 107 | 7.3 × 107 | 2.6 × 107 |

| 2 | 2.5 × 107 | 9.9 × 107 | 4.9 × 107 |

| 3 | 3.8 × 107 | 1.4 × 108 | 7.5 × 107 |

| 4 | 3.8 × 107 | 1.4 × 108 | 9.7 × 107 |

| 5 | 3.7 × 107 | 1.5 × 108 | 1.2 × 108 |

| 6 | 3.6 × 107 | 1.1 × 108 | 9.8 × 107 |

| 7 | 3.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 108 | 9.8 × 107 |

| 8 | 1.6 × 107 | 7.4 × 107 | 7.1 × 107 |

| 9 | 9.0 × 106 | 4.1 × 107 | 6.2 × 107 |

| 10 | 7.3 × 106 | 2.0 × 107 | 3.1 × 107 |

| 11 | 6.9 × 106 | 2.3 × 107 | 2.6 × 107 |

| 12 | 6.6 × 106 | 2.6 × 107 | 2.4 × 107 |

| 13 | 6.9 × 106 | 2.4 × 107 | 2.9 × 107 |

Batch cultures in 100 ml of ASW containing 5 g of tryptone per liter were grown at 98°C. The initial cell density was approximately 2.0 × 106 cells per ml, and the cell counts typically varied ±15%. Growth was monitored until the stationary phase or for at least 10 h.

The first transfer of cells was a transfer from a stock preparation grown without additional carbohydrates. Transfer preparations 1 through 5 contained 5 g of yeast extract per liter; transfer preparations 6 through 10 contained 4, 3, 2, 1, and 0 g of yeast extract per liter, respectively; and transfer preparations 11 through 13 contained no yeast extract.

Batch culture growth on β-glucans.

We compared growth on β-glucans to growth on glucose, maltose, and cellobiose and growth of a control in order to explore the range of β-glucanases that may be present in P. furiosus. As in the growth studies mentioned above, P. furiosus was acclimated to changes in medium composition by serial transfers until RM conditions were established. Table 2 shows the average MCDs obtained under RM conditions with the various glucan nutrient sources and with controls lacking carbohydrates. As described above, maltose-grown cells supported moderate growth which was comparable to the growth of cellobiose-grown cells. Somewhat higher cell densities were obtained with β-1,3 and β-1,3–β-1,4 polysaccharides. Pachyman and laminarin (β-1,3 glucans) and lichenan and barley glucan (mixed-linkage β-1,3–β-1,4 glucans) produced four- to sixfold-higher MCDs than the carbohydrate-free controls. Growth was most significant with the β-1,3 and β-1,4 oligosaccharides that were generated by enzymatic digestion of barley glucan with the hyperthermophilic laminarinase; more than 10-fold improvements in MCDs compared to controls were achieved. Polysaccharides based exclusively on β-1,4 linkages (i.e., carboxymethyl cellulose and cellulose) did not support significant growth.

TABLE 2.

P. furiosus growth on glucans

| Glucan substrate | Fold increase in MCD compared to controla

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Batch growth | Fed-batch growth | |

| Glucose | 1.7 | 4.6 |

| α-1,4 Maltose | 3.3 | 8.2 |

| β-1,4 Cellobiose | 3.1 | 7.5 |

| β-1,3 Pachyman | 4.9 | 5.6 |

| β-1,3 Laminarin | 4.3 | 5.9 |

| β-1,3 Laminarioligosaccharides | 10.1 | 21.8 |

| β-1,3–β-1,4 Lichenan | 4.8 | 6.2 |

| β-1,3–β-1,4 Barley glucan | 5.5 | 6.3 |

| β-1,4 Carboxymethyl cellulose | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| β-1,4 Cellulose (type 20) | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| β-1,4 Cellooligosaccharides | 11.6 | 29.3 |

Cells were grown in ASW containing tryptone (5 g/liter) and a glucan substrate (5 g/liter) in 100-ml batch cultures at 98°C. The initial cell density was approximately 2.0 × 106 cells/ml, and cultures were grown to the stationary phase or for at least 10 h. The average MCDs determined from four experiments (the standard deviations ranged from ±4.9% to ±18.3%) with each carbohydrate were used to calculate the relative cell yields. The average control MCD was approximately 7.0 × 106 cells per ml. An additional 1 g of substrate per liter was added from concentrated 100-g/liter stock preparations every hour in the fed-batch growth experiments.

Nonenzymatic temperature effects on the nutritional value of carbohydrates, particularly glucose.

Table 2 shows that glucose at a concentration of 5 g/liter marginally stimulated growth (the MCD was less than twofold higher with glucose than without glucose) compared to controls lacking carbohydrates, which is consistent with previous reports on the ineffectiveness of glucose as a growth substrate (14). This issue was examined by using glucose-based saccharides with DP ranging from 1 to 6 (Table 3). Comparisons of browning rates on a molar basis showed that color development increased with increasing DP. However, on a mass basis, the browning rate for glucose was much higher than the browning rates for the larger sugars. This could be attributed to a 1:1 reducing end-to-glucose moiety ratio for glucose compared to a 1:DP reducing end-to-glucose moiety ratio for larger saccharides. Thus, the low growth yields of P. furiosus on glucose compared to the yields on larger carbohydrates likely resulted from increased thermochemical lability of the monosaccharide at elevated temperatures (i.e., mutarotation, opening of the hemiacetal ring, and enolization [9, 10]).

TABLE 3.

Browning of oligosaccharides at 98°C

| Saccharide | Browning ratea

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Molar basis | Mass basis | |

| Glucose | 688 | 3,800 |

| Disaccharide | 913 | 2,670 |

| Trisaccharide | 1,115 | 2,210 |

| Tetrasaccharide | 1,427 | 2,140 |

| Pentasaccharide | 1,790 | 2,160 |

| Hexasaccharide | 2,243 | 2,260 |

Browning rates were determined by chromatographic integration of voltage signals generated by browning reactions for an initial incubation time, as detected with a refractive index detector (Δarea/min). The peak area had units of volt-seconds. The rates are averages obtained from three experiments involving each oligosaccharide. Samples were taken after incubation for 0, 10, 20, and 30 min, and linear regression was used to estimate rates (R2 ≥ 0.994 in all cases). The standard deviations ranged from ±1.9% to ±4.6%. For reference, incubation of 1.0 μmol (or 0.181 mg) of glucose at room temperature for extended periods of time corresponded to an area of 44,040 V-s. Therefore, with a rate of 688 Δarea/min, incubation for 64 min at 98°C would cause the glucose peak to double in area, as determined with the refractive index detector.

Fed-batch culture growth on β-glucans, glucose, and maltose.

P. furiosus growth on carbohydrates apparently depends on the extent of exposure of the substrate to high temperatures. This was examined by performing a series of fed-batch experiments in which 1 g of a carbohydrate per liter was added periodically in addition to the 5 g/liter added to the medium initially. Table 2 shows the changes in the average MCDs of P. furiosus cultures when additional substrate was added. β-1,4-Linked carboxymethyl cellulose and cellulose (type 20) were the only glucans that did not support growth. The average MCDs with all of the other glucans increased compared to the simple batch growth MCDs (Table 2). The most significant changes were observed with the smaller glucans, such as maltose and cellobiose, and with mixtures containing β-1,3 and β-1,4 oligosaccharides. An interesting finding of the fed-batch experiments was that the average MCD on glucose was nearly three times the average MCDs of the batch cultures.

DISCUSSION

The thermal labilities of specific carbohydrates with the respect to nutritional availability to hyperthermophilic microorganisms have not been examined to any significant extent. As the information presented here shows, polysaccharides may be significant compounds in hydrothermal biotopes because of the stabilizing effect that the polysaccharide form has on otherwise labile free hexoses. Heterotrophic hyperthermophiles are expected to harbor glycosyl hydrolases that can degrade stable, available polysaccharides in their ecological niches.

This conclusion is supported by the results of an examination of the glycosyl hydrolase content of P. furiosus (Table 4), which reflects the nutritional diversity of this organism with respect to carbohydrate substrates. Based on current information, P. furiosus readily grows on α-1,4- and α-1,6-linked glucans, as well as on certain β-linked glucans. Growth on nonglucans has not been observed. This is in contrast to the data obtained for members of the hyperthermophilic bacterial genus Thermotoga, which exhibit growth on both glucans (α- and β-linked glucans) and several nonglucans; a number of glycosyl hydrolases which are able to hydrolyze both glucans and nonglucans have been identified in various Thermotoga species (5, 6, 41). When glucans are used as growth substrates, P. furiosus prefers β-1,3 laminarin and β-1,3–β-1,4 mixed-linkage saccharides and does not grow when only β-1,4-linked polysaccharides, such as cellulose, are present. Growth on β-1,3-linked laminarin is consistent with reports that an exocellular laminarinase is produced by this organism (18). Our recent finding that a β-glucosidase from this organism (28) exhibits 2.5-fold greater activity with β-1,3 laminaribiose than with β-1,4 cellobiose further reinforces this conclusion (3, 13). The bgl gene, which encodes the β-glucosidase, has been found to be just “upstream” of the lamA gene, which encodes the laminarinase (18). This clustering of the lamA gene and the bgl gene could be related to expression of these two genes when they are induced in the presence of β-1,3 glucans. The second β-specific extracellular endoglucanase that has been identified and characterized is an extracellular family 12 endoglucanase (EglA) that hydrolyzes only β-1,4 bonds in β-1,3–β-1,4 mixed-linkage glucans and to a small extent β-1,4 bonds in cellulose (3). This enzyme acts in concert with the laminarinase to hydrolyze β-1,3–β-1,4 mixed-linkage saccharides (13). The gene for yet another putative β-1,4-specific endoglucanase has been identified in the P. furiosus genome, and the amino acid sequence of this enzyme corresponds to the amino acid sequences of family 60 glycosyl hydrolases. The physiological role of this enzyme is not known. In fact, only one endoglucanase belonging to this family has been characterized biochemically, the endoglucanase from Clostridium thermocellum. This enzyme exhibited activity with only one of the cellulosic substrates tested, carboxymethyl cellulose, and the specific activity was extremely low (30). Two putative chitinases from P. furiosus that belong to family 18 have also been identified and characterized biochemically (3, 5, 15a). Their capacity of these enzymes to hydrolyze β-1,4 N-acetylglucosamine-based polysaccharides is being investigated. Potential substrates for these enzymes have been identified in geothermal vent sites associated with clam shells, crab carapaces, and pogomophoran tubes (15, 25).

TABLE 4.

Glycosyl hydrolases of P. furiosus

| Enzyme | Hydrolytic specificity | Familya | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-Glucosidase | Exo, α-1,4 glucan | ? | 11 |

| Amylase A | Endo, α-1,4 glucan | 57 | 32 |

| Amylopullulanase A | Endo, α-1,4 and α-1,6 glucans | 57 | 8 |

| β-Glucosidase (Bgl) | Exo, β-1,3 and β-1,4 glucans | 1 | 27 |

| β-Mannosidase | Exo, β-1,4 mannan | 1 | 4 |

| Amylase B | Endo, α-1,4 glucan | 13 | 12, 25 |

| β-Glucosidase B (BglB)b | Exo, undetermined | 1 | |

| β-Glucosidase C (BglC)b | Exo, undetermined | 1 | |

| β-Galactosidaseb | Exo, undetermined | 35 | |

| Endoglucanase (EglA) | Endo, β-1,4 glucan | 12 | 3 |

| Laminarinase (LamA) | Endo, β-1,3 glucan | 16 | 17 |

| Endoglucanaseb | Endo, undetermined | 60 | |

| Chitinase Ab | Endo, β-1,4 N-acetylglucosamine | 18 | |

| Chitinase Bb | Endo, β-1,4 N-acetylglucosamine | 18 |

Family affiliations were determined on the basis of sequence similarities with other glycosyl hydrolases belonging to the families (19–21).

Sequencing of the P. furiosus genome (23) revealed the presence of the following six glycosidases whose recombinant forms are now being characterized biochemically (unpublished data): β-glucosidase B, β-glucosidase C, β-galactosidase, endoglucanase, chitinase A, and chitinase B.

The fact that P. furiosus grows well on glucose only if it is added periodically to fed-batch cultures is related to the thermochemical lability of this substrate in the growth environment. Indeed, nonenzymatic browning reactions involving sugars have been the focus of the food industry for decades (22). Two of these reactions, the heat-induced decomposition of sugars (without amine participation) or caramelization (32) and the Maillard reaction (2, 35, 36), which involves interactions between reducing end sugars and amino compounds, such as amino acids and proteins, have been studied the most. Caramelization proceeds rapidly at temperatures approaching 120°C at pH 3.0 to 9.0, whereas the Maillard reaction proceeds at temperatures above 50°C and is favored at pH 4.0 to 7.0 (32). The Maillard reaction may be the most problematic reaction for P. furiosus grown on carbohydrates in peptide-containing media. It is not completely clear what specific effects the intermediates and melanoidins generated by this reaction have on the nutritional value of sugars and how these effects are influenced by pH, temperature, and salt concentration. However, if fresh glucose is provided periodically, as in our fed-batch experiments, uptake could take place prior to extensive thermochemical modification. This possibility is supported by evidence that glucose is transported by resting P. furiosus cells (39, 41). Maltose, cellobiose, and higher glucans may offer a certain amount of structural protection to the monosaccharidic components away from the reducing end. Once glucan oligosaccharides are transported into the cell, they can be processed to glucose by intracellular glucosidases (11, 28) for immediate use in anabolic and catabolic reactions that take place before undesirable caramelization and Maillard reactions interfere. The ability of these glucosidases to hydrolyze glucan linkages in which the reducing end has been modified is being investigated.

The preference of P. furiosus for oligosaccharide substrates may reflect an adaptation to growth at temperatures at which simpler saccharides are thermochemically labile. It has been found that slightly less thermophilic hyperthermophiles, such as members of Thermotoga species, grow well on glucose at temperatures around 80°C (24). Thus, there may be a threshold temperature at which glucose is marginal as a carbon and energy source. The utilization of carbohydrates by hyperthermophiles also brings into question the source of this material in presumably primitive environments. One possibility is that the targets for the extracellular glycosyl hydrolases are exopolysaccharides known to be produced by several hyperthermophiles (34, 38). Patterns of carbohydrate utilization by hyperthermophilic microorganisms may provide insights into microbial interactions in geothermal environments and how these environments have evolved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We express our appreciation for the financial support provided by grant BES-9632657 from the National Science Foundation and by grant 96-35500-3456 from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams M W W, Kelly R M. Finding and using hyperthermophilicenzymes. TIBTECH. 1998;16:329–332. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(98)01193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ames J M. The Maillard browning reaction—an update. Chem Ind (London) 1988;17:558–561. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer M W, Driskill L E, Callen W, Snead M A, Mathur E J, Kelly R M. An endoglucanase, EglA, from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus hydrolyzes β-1,4 bonds in mixed linkage (1→3),(1→4)-β-d-glucans and cellulose. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:284–290. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.1.284-290.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer M W, Bylina E, Swanson R, Kelly R M. Comparison of a β-glucosidase and a β-mannosidase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus: purification, characterization, gene cloning and sequence analysis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23749–23755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.39.23749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer M W, Driskill L E, Kelly R M. Glycosyl hydrolases from hyperthermophilic microorganisms. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1998;9:141–145. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(98)80106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer M W, Halio S B, Kelly R M. Proteases and glycosyl hydrolases from hyperthermophilic microorganisms. Adv Protein Chem. 1996;48:271–310. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown S H, Costantino H R, Kelly R M. Characterization of amylolytic enzyme activities associated with the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium Pyrococcus furiosus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1985–1991. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.7.1985-1991.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown S H, Kelly R M. Characterization of amylolytic enzymes having both α-1,4 and α-1,6 hydrolytic activity from the thermophilic archaea Pyrococcus furiosus and Thermococcus litoralis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2614–2621. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2614-2621.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buera M D P, Chirife J, Resnik S L, Lozano R D. Nonenzymatic browning in liquid model systems of high water activity: kinetics of color changes due to caramelization of various single sugars. J Food Sci. 1987;52:1059–1062. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buera M D P, Chirife J, Resnik S L, Wetzler G. Nonenzymatic browning in liquid model systems of high water activity: kinetics of color changes due to Maillard’s reaction between different single sugars and glycine and comparison with caramelization browning. J Food Sci. 1987;52:1063–1067. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costantino H R, Brown S H, Kelly R M. Purification and characterization of an α-glucosidase from a hyperthermophilic archaebacterium, Pyrococcus furiosus, exhibiting a temperature optimum of 105 to 115°C. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3654–3660. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3654-3660.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong G, Vielle C, Savchenko A, Zeikus J G. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the gene encoding extracellular α-amylase from Pyrococcus furiosus and biochemical characterization of the recombinant enzyme. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3569–3576. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3569-3576.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Driskill L E. M.S. thesis. Raleigh: North Carolina State University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiala G, Stetter K O. Pyrococcus furiosus, new species represents a novel genus of marine heterotrophic archaebacteria growing optimally at 100°C. Arch Microbiol. 1986;145:56–60. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gage J D, Tyler P A. Deep-sea hydrothermal vents and cold seeps. In: Gage J D, Tyler P A, editors. Deep-sea biology: a natural history of organisms at deep-sea floor. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1991. pp. 363–391. [Google Scholar]

- 15a.Gao, J., M. W. Bauer, and R. M. Kelly. Unpublished data.

- 16.Gomez C, Navarro A, Manzanares P, Horta A, Carbonell J V. Physical and structural properties of barley (1→3),(1→4)-β-d-glucan. Part I. Determination of molecular weight and macromolecular radius by light scattering. Carbohydr Polymers. 1997;32:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomez C, Navarro A, Manzanares P, Horta A, Carbonell J V. Physical and structural properties of barley (1→3),(1→4)-β-d-glucan. Part II. Viscosity, chain stiffness and macromolecular dimensions. Carbohydr Polymers. 1997;32:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gueguen Y, Voorhorst W G B, van der Oost J, de Vos W M. Molecular and biochemical characterization of an endo-β-1,3-glucanase of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31258–31264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henrissat B. A classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino-acid-sequence similarities. Biochem J. 1991;280:309–316. doi: 10.1042/bj2800309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henrissat B, Bairoch A. New families in the classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem J. 1993;293:781–788. doi: 10.1042/bj2930781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henrissat B, Callebaut I, Fabrega S, Lehn P, Mornon J P, Davies G. Conserved catalytic machinery and the prediction of a common fold for several families of glycosyl hydrolases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7090–7094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.7090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodge J E. Dehydrated foods: chemistry of browning reactions in model systems. J Agric Food Chem. 1953;1:928–943. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holzman D. DOE moves to second round of microbial genome sequencing. ASM News. 1996;62:8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huber R, Langworthy T A, Konig H, Thomm M, Woese C R, Sleytr U B, Stetter K O. Thermotoga maritima sp. nov. represents a new genus of unique extremely thermophilic eubacteria growing up to 90°C. Arch Microbiol. 1986;144:324–333. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones M L. Riftia pachyptila, new genus new species, the vestimentiferan worm from the Galapagos Rift geothermal vents (Pogonophora) Proc Biol Soc Wash. 1980;93:1295–1313. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jørgensen S, Vorgias C E, Antranikian G. Cloning, sequencing, characterization and expression of an extracellular α-amylase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16335–16342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kengen S W M, de Bok F A M, van Loo N D, Dijkema C, Stams A J M, de Vos W M. Evidence for the operation of a novel Embden-Meyerhof pathway that involves ADP-dependent kinases during sugar fermentation by Pyrococcus furiosus. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17537–17541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kengen S W M, Luesink E J, Stams J M, Zehnder A J B. Purification and characterization of an extremely thermostable β-glucosidase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. Eur J Biochem. 1993;213:305–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kengen S W M, Stams A J M, de Vos W M. Sugar metabolism of hyperthermophiles. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1996;18:119–137. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi T, Romaniec M P M, Barker P J, Gerngross U T, Demain A L. Nucleotide sequence of gene celM encoding a new endoglucanase (CelM) of Clostridium thermocellum and purification of the enzyme. J Ferment Bioeng. 1993;76:251–256. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koch R, Zablowski P, Spreinat A, Antranikian G. Extremely thermostable amylolytic enzyme from the archaebacterium Pyrococcus furiosus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;71:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroh L W. Carmelisation of food and beverages. Food Chem. 1994;51:373–379. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laderman K A, Asada K, Uemori T, Mukai H, Taguchi Y, Kato I, Anfinsen C B. α-Amylase from the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium Pyrococcus furiosus. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24402–24407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.LaPlagia C, Hartzell P L. Stress-induced production of biofilm in the hyperthermophile Archaeglobus fulgidus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3158–3163. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3158-3163.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Brien J M, Labuza T P. Symposium provides new insights into nonenzymatic browning reactions. Food Technol. 1994;48(7):56–58. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petriella C, Resnik S L, Lozano R D, Chirife J. Kinetics of deteriorative reactions in model food systems of high water activity: color changes due to nonenzymatic browning. J Food Sci. 1985;50:622–626. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Read S M, Currie G, Bacic A. Analysis of the structural heterogeneity of laminarin by electrospray-ionisation-mass spectrometry. Carbohydr Res. 1996;281:187–201. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(95)00350-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rinker K D, Kelly R M. Growth physiology of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus litoralis: development of a sulfur-free defined medium, characterization of an exopolysaccharide, and evidence of biofilm formation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4478–4485. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.12.4478-4485.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robertson D E, Mathur E J, Swanson R V, Marrs B L, Short J M. The discovery of new biocatalysts from microbial diversity. Soc Ind Microbiol News. 1996;46:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schäfer T, Xavier K B, Santos H, Schönheit P. Glucose fermentation to acetate and alanine in resting cell suspensions of Pyrococcus furiosus: proposal of a novel glycolytic pathway based on 13C labeling data and enzyme activities. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;121:107–114. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sunna A, Moracci M, Antranikian G. Glycosyl hydrolases from hyperthermophilic microorganisms. Extremophiles. 1997;1:2–13. doi: 10.1007/s007920050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Usenko I A, Severina L O, Plakunov V K. Uptake of sugars and amino acids by extremely thermophilic archae- and eubacteria. Microbiology (Engl Transl Mikrobiologiya) 1993;62:272–277. [Google Scholar]