Abstract

The growth characteristics of Heterosigma akashiwo virus clone 01 (HaV01) were examined by performing a one-step growth experiment. The virus had a latent period of 30 to 33 h and a burst size of 7.7 × 102 lysis-causing units in an infected cell. Transmission electron microscopy showed that the virus particles formed on the peripheries of viroplasms, as observed in a natural H. akashiwo cell. Inoculation of HaV01 into a mixed algal culture containing four phytoplankton species, H. akashiwo H93616, Chattonella antiqua (a member of the family Raphidophyceae), Heterocapsa triquetra (a member of the family Dinophyceae), and Ditylum brightwellii (a member of the family Bacillariophyceae), resulted in selective growth inhibition of H. akashiwo. Inoculation of HaV01 and H. akashiwo H93616 into a natural seawater sample produced similar results. However, a natural H. akashiwo red tide sample did not exhibit any conspicuous sensitivity to HaV01, presumably because of the great diversity of the host species with respect to virus infection. The growth characteristics of the lytic virus infecting the noxious harmful algal bloom-causing alga were considered, and the possibility of using this virus as a microbiological agent against H. akashiwo red tides is discussed.

Heterosigma akashiwo virus (HaV) is a relatively large DNA virus that infects Heterosigma akashiwo (a member of the family Raphidophyceae), which is one of the typical harmful algal bloom (HAB)-causing microalgae (11). The host specificity of HaV, the effects of physicochemical conditions on HaV algicidal activity, and storage techniques for HaV have been examined previously (11–14).

H. akashiwo occurs in coastal waters of subarctic and temperate areas of both the Northern Hemisphere and the Southern Hemisphere. It often kills cultured fish, including salmon, yellowtail, and sea bream, and the damage to aquaculture caused by H. akashiwo has been increasing (4, 5). Cage-reared chinook salmon worth seventeen million New Zealand dollars were killed in Big Glory Bay, New Zealand, in 1989 (2). In Japan, cultured yellowtail, amberjack, striped jack, etc. worth 1,090 million and 237 million yen were killed in Kagoshima Bay in 1995 and in Nomi Bay in 1997, respectively (the amounts of damage are estimates made by the Fisheries Agency of Japan). Therefore, practical countermeasures against blooms caused by this noxious microalga are urgently needed. In order to develop practical countermeasures for eliminating HAB, the algicidal activities of microorganisms have been examined, and algicidal bacteria and viruses have recently been isolated and studied (7).

Any microbiological agent used for elimination of HAB in the natural environment must fulfill the following three requirements: it must be practical in terms of scale, cost, and safety (10). Thus, scale and the specificity of algicidal activity must be considered prior to application of HaV. The objective of this study was to examine the growth characteristics of HaV and the algicidal activity of HaV in mixed algal cultures and in natural waters. Based on the results obtained, the possibility of using HaV as a microbiological agent against H. akashiwo is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Host strains and virus clones.

Two strains of H. akashiwo were used in this study; H. akashiwo H93616 was isolated from the northern part of Hiroshima Bay (Hiroshima Prefecture) in June 1993, and H. akashiwo NM96 was isolated from Nomi Bay (Kochi Prefecture) in July 1996 (12). Neither algal culture contained bacteria. The algal strains were grown in modified SWM3 medium (3, 8) enriched with 2 nM Na2SeO3 at 20°C by using a cycle consisting of 14 h of cool white fluorescent illumination (ca. 45 μmol of photons m−2 s−1) and 10 h of darkness prior to each experiment.

HaV clone 01 (HaV01), which infects both H. akashiwo NM96 and H93616 and was isolated from Unoshima Fishing Port (Fukuoka Prefecture) in 1996, was used in this study (12). This virus clone was made axenic by filtering a preparation through a 0.2-μm-pore-size Nuclepore filter and treating it with antibiotics. Just prior to each experiment, the HaV01 stock preparation was inoculated into a fresh culture of H. akashiwo NM96 or H93616 and incubated at 20°C for 3 days for multiplication, and the resulting viral suspension was used as the inoculum. The virus titer was estimated by the extinction dilution method (11), and the most probable number was calculated by using the computer program developed by Nishihara et al. (16).

One-step growth experiment.

In order to estimate the latent period and burst size of HaV01, a one-step growth experiment was designed. An H. akashiwo NM96 culture in the late log phase was inoculated with HaV01. The initial densities of the host alga and HaV01 were 1.27 × 105 cells/ml and 2.58 × 105 lysis-causing units (LCU)/ml, respectively; viz., the multiplicity of infection (MOI) was 2.04. The algicidal effects were monitored by determining the host cell density directly by optical microscopy. When most of the host cells had disappeared, the HaV01 density was titrated by the extinction dilution method, and the burst size was calculated. The incubation conditions were as described above and were determined based on the effects of physicochemical conditions on the algicidal activity of HaV01 (13). Aliquots of the algal culture were periodically examined by transmission electron microscopy. The samples used for transmission electron microscopy were prepared by using the method of Nagasaki et al. (15).

Algicidal effects of HaV01 in the mixed algal culture.

Exponentially growing H. akashiwo H93616, Chattonella antiqua OC-B5 (a member of the family Raphidophyceae), Heterocapsa triquetra H9104 (a member of the family Dinophyceae), and Ditylum brightwellii (a member of the family Bacillariophyceae) cultures were mixed; the initial densities of the cultures used were 2.0 × 103, 5.2 × 102, 2.2 × 102, and 1.4 × 102 cells/ml, respectively. HaV01 was inoculated into 50-ml portions of the mixed culture so that the initial HaV01 densities were 6.4 × 103 and 6.4 × 101 LCU/ml; viz., the MOI with respect to H. akashiwo cells were 3.2 and 0.032, respectively. As a control, an HaV01 suspension was incubated at 100°C for 5 min, cooled, and inoculated into a portion of the mixed culture at an initial density of 6.4 × 103 LCU/ml. The incubation conditions were the same as those described above. The density of each alga was monitored by direct counting with an optical microscope.

Algicidal activity of HaV01 in the natural seawater culture.

The algicidal effects of HaV01 in natural seawater were examined twice. First, surface water was collected in Kure Port in northern Hiroshima Bay on 8 April 1998; the density of H. akashiwo in this water was 5 cells/ml. H. akashiwo H93616 and HaV01 were inoculated into 100 ml of this natural seawater at initial densities of 6.3 × 103 cells/ml and 1.7 × 106 LCU/ml, respectively; viz., the MOI with respect to H. akashiwo cells was 260. For the control experiments, we used a filtrate obtained by passing an H. akashiwo H93616 culture through a type GF/F filter and a HaV01 suspension that had been incubated at 100°C for 5 min. The effects of the algal culture filtrate and the heat-treated virus suspension on the growth of H. akashiwo H93616 were also examined. The incubation conditions and methods used to monitor algal growth were the same as those described above. For the second experiment, surface water was collected in Kusatsu Fishing Port in northern Hiroshima Bay on 28 April 1998; diatoms were the dominant organisms in this water, and H. akashiwo was not detected. H. akashiwo H93616 and HaV01 were inoculated into 100 ml of this natural seawater at initial densities of 3.3 × 103 cells/ml and 2.3 × 103, 2.3 × 102, and 2.3 × 101 LCU/ml, respectively; viz., the MOI with respect to H. akashiwo cells (including both natural cells and strain H93616 cells) were 0.70, 0.07, and 0.007, respectively. For the control experiment, we used an H. akashiwo H93616 culture filtrate and a heat-treated suspension of HaV01. The incubation conditions and monitoring methods used were the same as those described above.

RESULTS

One-step growth experiment.

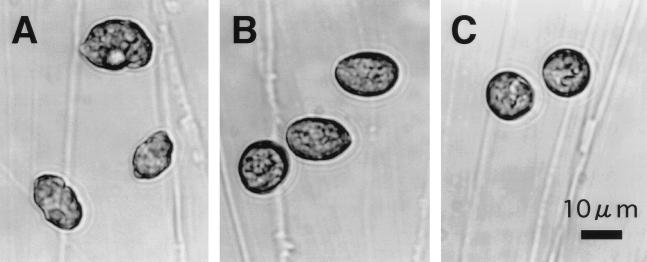

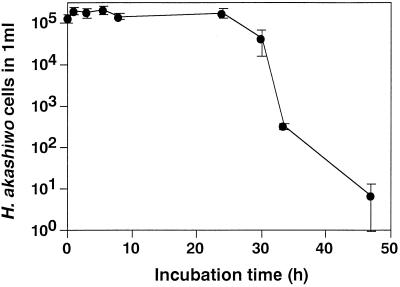

In the one-step growth experiment, H. akashiwo cells became roundish within 8 h after inoculation of HaV01 (Fig. 1). Almost all of the cells lost motility within 24 h. The H. akashiwo cell density decreased drastically and the culture became transparent 30 to 33 h after inoculation (Fig. 2). After lysis of most of the cells in the host culture at 33 to 47 h after inoculation, a small number of surviving cells were observed; these cells were roundish and had lost motility. At 47 h after inoculation, the host cell density had decreased to less than 101 cells/ml, while the density of HaV01 had increased to 9.8 × 107 LCU/ml (Fig. 2). Considering the high initial MOI (2.04) and the synchronous lysis of the host cells, it is probable that most of the H. akashiwo cells did not escape HaV01 infection; that is, this experiment established that one-step growth of HaV01 occurred. The data show that 9.8 × 107 HaV01 particles originating from 1.3 × 105 virus-infected H. akashiwo cells were released into the culture, indicating that ca. 7.7 × 102 infectious particles were produced by each H. akashiwo cell infected with HaV01. The latent period of HaV01 is considered to be 30 to 33 h.

FIG. 1.

Optical microphotographs of H. akashiwo NM96 cells before inoculation (A) and 4 h (B) and 8 h (C) after inoculation of HaV01.

FIG. 2.

Changes in density of H. akashiwo cells in the one-step growth experiment in which the initial MOI of HaV01 was 2.04. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

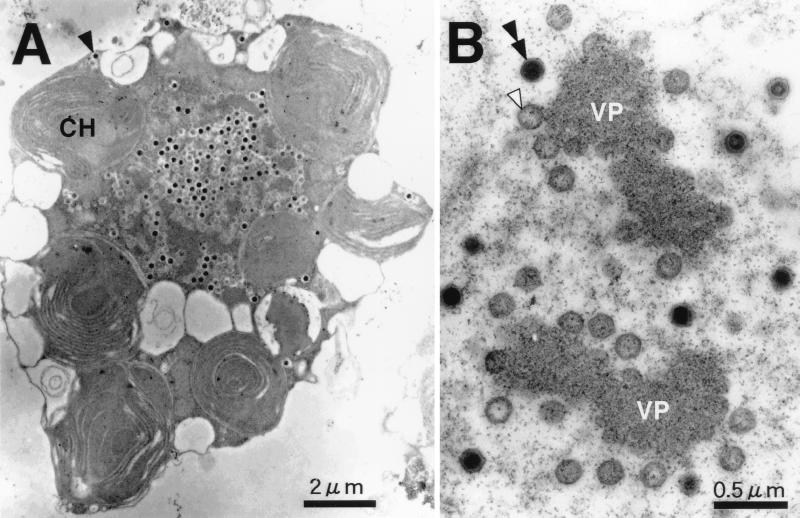

At 24 h after virus inoculation, both mature and immature daughter virus particles were observed in most of the thin sections of H. akashiwo cells. A typical thin section of an infected cell contained ca. 170 sections of virus particles in a circular area with a diameter of 4 μm (Fig. 3A). Assuming that virus particles were distributed at the same concentration in a virus-synthesizing globular zone, ca. 103 virus particles could have been present in a hypothetical globe. This value is comparable to the burst size (7.7 × 102 LCU/ml) calculated by the extinction dilution method in the one-step growth experiment. HaV01 particles were presumably formed on the periphery of the viroplasm (Fig. 3B), as previously observed in H. akashiwo samples obtained from natural waters (15), suggesting that the viruslike particles observed in the previous field studies and the HaV01 particles are identical. HaV01 particles were also observed in the subsurface area, which presumably had been released from the viroplasm and had virus DNA inserted (Fig. 3A, arrowhead).

FIG. 3.

(A) Transmission electron micrograph of an H. akashiwo NM96 cell 24 h after inoculation of HaV01. (B) Higher magnification of viroplasm (VP). Virus particles were found in the subsurface area, as well as in the viroplasm area (arrowheads). Note the difference between the mature virions (double arrowhead) and the immature virions (white arrowhead). CH, chloroplast.

Algicidal effects of HaV01 in the mixed algal culture.

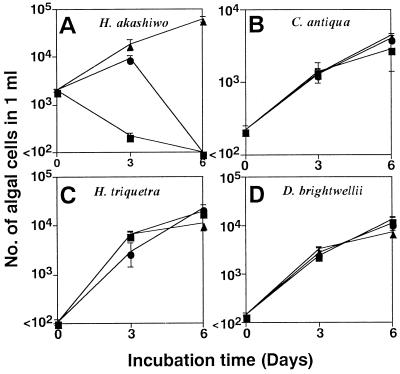

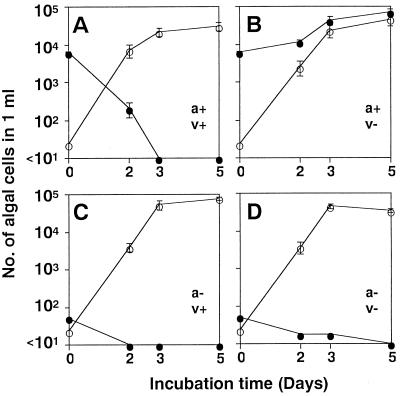

Specific algicidal effects of HaV01 were observed even when C. antiqua, H. triquetra, and D. brightwellii were also present (Fig. 4). Although the rate of disappearance of H. akashiwo was affected by the MOI, H. akashiwo was specifically eliminated even with the lower MOI used in this experiment (0.03). In contrast, HaV01 had no conspicuous effect on the growth of the other three species of phytoplankton.

FIG. 4.

Changes in densities of H. akashiwo (A), C. antiqua (B), H. triquetra (C), and D. brightwellii (D) cells in the mixed algal culture inoculated with HaV01 at MOI of 3.23 (■), 0.03 (●), and 0 (▴). The error bars indicate standard deviations.

Algicidal activity of HaV01 in the natural seawater culture.

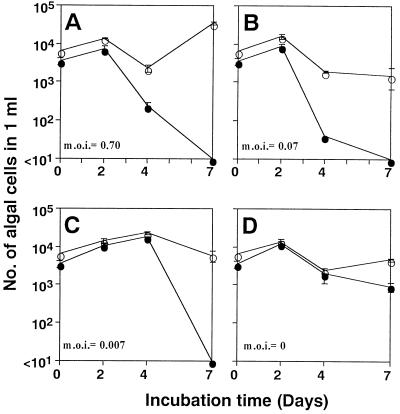

The algicidal effects of HaV01 in natural seawater are shown in Fig. 5 and 6. HaV01 specifically affected H. akashiwo H93616 in unsterilized natural seawater cultures containing numerous natural microorganisms (data not shown). In addition, HaV01 had no obvious effect on the growth of diatoms even at an MOI of 260, which in a natural environment would correspond to an extraordinarily high HaV density (Fig. 5). H. akashiwo H93616 was specifically eliminated even when the MOI was as low as 0.007 (Fig. 6).

FIG. 5.

Changes in densities of H. akashiwo (●) and diatom (○) cells in the natural seawater sample collected at Kure Port on 8 April 1998. The natural seawater was inoculated with an H. akashiwo culture (a+) and nontreated HaV01 (v+) (A), an H. akashiwo culture and heat-treated HaV01 (v−) (B), an H. akashiwo culture filtrate (a−) and nontreated HaV01 (C), and an H. akashiwo culture filtrate and heat-treated HaV01 (D). The error bars indicate standard deviations.

FIG. 6.

Changes in densities of H. akashiwo (●) and diatom (○) cells in the natural seawater collected at Kusatsu Fishing Port on 28 April 1998. Natural seawater samples were inoculated with H. akashiwo and HaV01 at MOI of 0.7 (A), 0.07 (B), 0.007 (C), and 0 (D). The error bars indicate standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

HaV01 has a latent period of 30 to 33 h and a burst size of 7.7 × 102 LCU per infected cell. Compared with the other microalgal viruses whose growth characteristics have been studied, the burst size and the latent period of HaV01 are greater and longer, respectively (Table 1). If these data are used, the potential infectivity can be provisionally calculated based on the growth characteristics of HaV01 estimated in the one-step growth experiment. If an HaV01 particle whose latent period and burst size are 33 h and 7.7 × 102 LCU/ml, respectively, is placed in 1 ml of seawater and constantly supplied with sensitive fresh host cells, ca. 6.0 × 105 infectious particles should be released into the 1 ml of seawater after two cycles of infection, which should take ca. 66 h. Considering that the highest density of H. akashiwo cells in natural red tide water is ca. 4 × 105 cells/ml (6), this virus density is high enough to potentially infect all of the cells. The highest yield of HaV01 that we have obtained in our laboratory is ca. 108 infectious LCU/ml, which implies that 1 ha of shallow (mean depth, 10 m) coastal water should have an HaV density of ca. 1 particle/ml if 1 liter of the HaV suspension is used. In addition, low-cost small-scale production of HaV (in 2-liter flasks) is possible in a laboratory. Although the calculations described above are merely theoretical, use of HaV as a microbiological agent appears to be promising from the viewpoint of scale and cost. Of course, additional technical improvements would be required for large-scale production of HaV prior to practical use of HaV as a microbiological agent for elimination of red tide.

TABLE 1.

Growth and reproduction of algal viruses

| Host alga | Latent period (h) | Burst size | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorella-like alga | 3–4 | 200–350 | 18 |

| Micromonas pusilla | 7–14 | 70 | 19 |

| Chrysochromulina brevifilum | NDa | >320 | 17 |

| Emiliania huxleyi | ND | 350–700 | 1 |

| Phaeocystis pouchetii | 12–18 | 350–600 | 9 |

| Heterosigma akashiwo | 30–33 | 770 | This paper |

ND, not determined.

The present experiments also showed that HaV01 specifically eliminates H. akashiwo H93616 when other phytoplankton species are present and in natural seawater containing numerous natural microorganisms, even at a low MOI. Thus, HaV01 specifically infects H. akashiwo even when other microorganisms are present in the ambient water. From the viewpoint of the safety of using HaV as a microbiological agent for elimination of red tide, HaV specifically affects the target alga, H. akashiwo, and appears to have little influence on other phytoplankton in the natural environment.

On the basis of the characteristics determined so far, HaV01 is a promising tool for controlling H. akashiwo red tides because (i) it has a high growth rate and thus can be applied to natural environments (i.e., it meets the scale requirement), (ii) it can be produced at a low cost, and (iii) it specifically attacks the target HAB-causing alga and has little or no effect on other organisms, guaranteeing its safety. In addition, HaV01 originates from natural coastal water and has not been genetically manipulated or altered in any way from its natural form (11).

A preliminary examination on the algicidal effects of HaV01 on a natural population of H. akashiwo red tide was performed by using water collected in northern Hiroshima Bay on 18 May 1998, in which H. akashiwo (8.0 × 103 cells/ml) and Eutreptiella spp. (8.2 × 103 cells/ml) dominated and diatoms were scarce. HaV01 was inoculated into the natural seawater sample at an MOI with respect to the natural H. akashiwo cells of 0.12. However, little specific growth inhibition of H. akashiwo was detected (data not shown). Although it has not been determined why the natural H. akashiwo population was not eliminated, it should be noted that natural populations of both sensitive and resistant cells occur in natural H. akashiwo red tide seawater samples (12). Therefore, the intraspecies specificity of HaV appears to be the most difficult obstacle to the use of this virus as a microbiological agent against H. akashiwo red tides. To solve this problem, what determines the infection specificity of HaV against H. akashiwo must be clarified. Another practical solution would be to prepare a cocktail of HaV clones, each with a different specificity of infection.

In conclusion, although HaV is a possible microbiological agent when scale, cost, and safety are considered, the effects of various HaV clones on natural populations of H. akashiwo must be assessed in more detail before this virus can be used for elimination of H. akashiwo red tides.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Fisheries Agency of Japan.

We thank S. Norland (University of Bergen) for preparing the most-probable-number computer program and S. Itakura (National Research Institute of Fisheries and Environment of Inland Sea) for isolating H. akashiwo NM96.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bratbak G, Wilson W, Heldal M. Viral control of Emiliania huxleyi blooms? J Mar Syst. 1996;9:75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang F H, Anderson C, Bousted N C. First record of a Heterosigma (Raphidophyceae) bloom with associated mortality of cage-reared salmon in Big Glory Bay, New Zealand. N Z J Mar Freshwater Res. 1990;24:461–469. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen L C M, Edelstein T, McLachlan J. Bonnemaisonia hamifera Hariot in nature and in culture. J Phycol. 1969;5:211–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.1969.tb02605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hallegraeff G M. Aquaculturists’ guide to harmful Australian microalgae. Hobart, Australia: CSIRO; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Honjo T. Overview on bloom dynamics and physiological ecology of Heterosigma akashiwo. In: Smayda T J, Simizu Y, editors. Toxic phytoplankton blooms in the sea. New York, N.Y: Elsevier; 1993. pp. 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iizuka S. The results of a survey of maximum densities in cell number of phytoplankton in coastal waters of Japan. Bull Plankton Soc Jpn. 1985;32:67–72. . (In Japanese with English abstract.) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishida Y. Microbial control of red tide microalgae and its prospect. In: Ishida I, Sugahara I, editors. Prevention and control of red tide microalgae by microorganisms. Kosei-sha Kosei-kaku, Tokyo, Japan. (In Japanese.) 1994. pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito K, Imai I. Japan Fisheries Resource Conservation Association (ed.), A guide for studies of red tide organisms. Shuwa, Tokyo, Japan. (In Japanese.) 1987. Rafido so (Raphidophyceae) pp. 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobsen A, Bratbak G, Heldal M. Isolation and characterization of a virus infecting Phaeocystis pouchetii (Prymnesiophyceae) J Phycol. 1996;32:923–927. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagasaki K. Possible use of algicidal viruses as microbiological agents against harmful algal blooms. Microb Environ. 1998;13:109–113. . (In Japanese with English abstract.) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagasaki K, Yamaguchi M. Isolation of a virus infectious to the harmful bloom causing microalga Heterosigma akashiwo (Raphidophyceae) Aquat Microb Ecol. 1997;13:135–140. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagasaki K, Yamaguchi M. Intra-species host specificity of HaV (Heterosigma akashiwo virus) clones. Aquat Microb Ecol. 1998;14:109–112. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagasaki K, Yamaguchi M. Effect of temperature on the algicidal activity and the stability of HaV (Heterosigma akashiwo virus) Aquat Microb Ecol. 1998;15:211–216. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagasaki, K., and M. Yamaguchi. Cryopreservation of a virus (HaV) infecting a harmful bloom causing microalga, Heterosigma akashiwo (Raphidophyceae). Fish. Sci., in press.

- 15.Nagasaki K, Ando M, Imai I, Itakura S, Ishida Y. Virus-like particles in Heterosigma akashiwo (Raphidophyceae): a possible red tide disintegration mechanism. Mar Biol. 1994;119:307–312. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishihara T, Kurano N, Shinoda S. Calculation of most probable number for enumeration of bacteria on a micro-computer. Eisei Kagaku. 1986;32:226–228. . (In Japanese with English abstract.) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suttle C A, Chan A M. Viruses infecting the marine Prymnesiophyte Chrysochromulina spp.: isolation, preliminary characterization and natural abundance. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1995;118:275–282. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Etten J L, Lane L C, Meints R H. Viruses and viruslike particles of eukaryotic algae. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:586–620. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.4.586-620.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waters R E, Chan A T. Micromonas pusilla virus: the virus growth cycle and associated physiological events within the host cells: host range mutation. J Gen Virol. 1982;63:199–206. [Google Scholar]