Abstract

It has recently been reported that Pleurotus pulmonarius secretes a versatile peroxidase that oxidizes Mn2+, as well as different phenolic and nonphenolic aromatic compounds; this enzyme has also been detected in other Pleurotus species and in Bjerkandera species. During culture production of the enzyme, the activity of the main peak was as high as 1,000 U/liter (measured on the basis of the Mn3+-tartrate formation) but this peak was very ephemeral due to enzyme instability (up to 80% of the activity was lost within 15 h). In culture filtrates inactivation was even faster; all peroxidase activity was lost within a few hours. Using different inhibitor compounds, we found that proteases were not responsible for the decrease in peroxidase activity. Peroxidase instability coincided with an increase in the H2O2 concentration, which reached 200 μM when filtrates were incubated for several hours. It also coincided with the onset of biosynthesis of anisylic compounds and a decrease in the pH of the culture. Anisyl alcohol is the natural substrate of the enzyme aryl-alcohol oxidase, the main source of extracellular H2O2 in Pleurotus cultures, and addition of anisyl alcohol to filtrates containing stable peroxidase activity resulted in rapid inactivation. A decrease in the culture pH could also dramatically affect the stability of the P. pulmonarius peroxidase, as shown by using pH values ranging from 6 to 3.25, which resulted in an increase in the level of inactivation by 10 μM H2O2 from 5 to 80% after 1 h. Moreover, stabilization of the enzyme was observed after addition of catalase, Mn2+, or some phenols or after dialysis of the culture filtrate. We concluded that extracellular H2O2 produced by the fungus during oxidation of aromatic metabolites is responsible for inactivation of the peroxidase and that the enzyme can protect itself in the presence of different reducing substrates.

Lignin degradation by basidiomycetes belonging to the genus Pleurotus is being investigated because of the industrial potential of some of these fungi for selectively removing lignin from wheat straw (26, 32). It has been shown by using in vivo 14C labeling that Mn2+ stimulates lignin mineralization by Pleurotus pulmonarius under solid-state fermentation (SSF) conditions (5). This suggests that Mn3+ is involved; Mn3+ can be generated directly by the Mn2+-oxidizing peroxidases secreted by ligninolytic fungi (22, 38) or indirectly by other ligninolytic enzymes (36). In the presence of chelators secreted by fungi (30), the Mn3+ formed could be responsible for the attack on lignin “at a distance” by the fungal mycelium. This degradation pattern, which is characteristic of extensive fungal delignification of wood in nature (3), has been found in straw treated with Pleurotus species (32).

Seven extracellular Mn2+-oxidizing peroxidases have been purified from liquid and SSF cultures of Pleurotus eryngii and P. pulmonarius and characterized (33). Two additional peroxidases have been obtained from liquid cultures of Pleurotus ostreatus (2, 42). All of these enzymes efficiently oxidize Mn2+ to Mn3+ and therefore have been described as Mn peroxidases. However, six of them, including the enzymes from P. pulmonarius, exhibit activity on phenolic and nonphenolic aromatic substrates and dyes, and the optimum pH for Mn-independent reactions is around 3 (24, 33, 34). Because of this they can be considered representatives of a new type of peroxidase with catalytic properties intermediate between the catalytic properties of Phanerochaete chrysosporium Mn-dependent peroxidases (MnP), which require Mn2+ to complete the catalytic cycle, and the catalytic properties of lignin peroxidase (LiP) (29). Molecular characterization of the new peroxidases isolated from P. eryngii has revealed that on the basis of amino acid sequence and molecular architecture these enzymes are more similar to P. chrysosporium LiP than to MnP (41) and that they have an Mn-binding site which accounts for their ability to oxidize Mn2+ (25). Peroxidases with similar catalytic properties have been found recently in Bjerkandera adusta (23) and Bjerkandera sp. (35).

P. pulmonarius is a strongly ligninolytic fungus, as revealed by the greater wheat lignin mineralization by this organism than by P. chrysosporium or other Pleurotus species (5). High levels of the new peroxidase described above are produced by this fungus in peptone-containing media. However, the main activity peak is very ephemeral. Efficient production and purification of this enzyme from liquid cultures are hampered by the very rapid decline in peroxidase activity that occurs. A similar phenomenon has been described for production of enzymes by other ligninolytic fungi, and proteinases have been found to be largely responsible for this decline in enzyme activity (13, 40). In the present work we investigated the causes of peroxidase instability in P. pulmonarius cultures and ways to protect the enzyme against inactivation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungi and culture conditions.

P. pulmonarius CBS 507.85 (= IJFM A578) was grown in 2% glucose–0.2% yeast extract–0.5% peptone medium containing 1 g of H2PO4 per liter and 0.5 g of MgSO4 per liter (pH 5.5) (28). A homogenized 7-day-old culture in the same medium was used as the inoculum (4%, vol/vol), and incubation was carried out at 28°C and 200 rpm. Samples were collected after different incubation periods, filtered, and analyzed directly or stored at −80°C.

Enzymatic activities.

P. pulmonarius peroxidase activity was generally estimated on the basis of the formation of an Mn3+-tartrate complex (ɛ238, 6,500 M−1 cm−1) during oxidation of 0.1 mM MnSO4 in 0.1 M sodium tartrate (pH 5) containing 0.1 mM H2O2. In experiments which included EDTA or compounds with high levels of UV absorbance, the peroxidase activity was estimated by measuring the direct oxidation of 2.5 mM 2,6-dimethoxyphenol (ɛ469, 27,500 M−1 cm−1) in 0.1 M sodium tartrate (pH 3) containing 0.1 mM H2O2 (34). Aryl-alcohol oxidase (AAO) activity was determined by measuring the amount of veratraldehyde (ɛ310, 9,300 M−1 cm−1) formed from 5 mM veratryl alcohol in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6). Laccase activity was measured by using 10 mM 2,6-dimethoxyphenol in 0.1 M sodium tartrate (pH 5). One unit of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that transformed 1 μmol of substrate per min.

Proteinase studies.

Proteinase activity was measured by using 0.25% azocasein in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6). After incubation for 30 min at 30°C, azocasein was precipitated with trichloroacetic acid, and the activity in the supernatant was determined by measuring the absorbance at 440 nm. One unit of proteinase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that produced a change of 1 absorbance unit per min. Additional information concerning proteinase activity was obtained by adding 0.2% insoluble azo dye-impregnated collagen (azocoll) (Sigma) to whole cultures or filtrates and monitoring the release of soluble red-dyed peptides (at 520 nm) during 24 h of incubation at 28°C. Finally, different compounds were tested as proteinase inhibitors by using azocasein as the substrate; the compounds tested included phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (0.1 mM), 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride (AEBSF) (1 mg/ml), EDTA (1 to 5 mM), leupeptin (1 μM), and pepstatin (1 μM).

Estimation of hydrogen peroxide concentration.

The H2O2 concentration was estimated by using horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and phenol red as the substrate (39). Samples were incubated with 0.01% phenol red in 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 6) containing 2.5 U of HRP per ml in a 950-μl (total volume) reaction mixture. The reaction was stopped by adding 50 μl of 3 M NaOH. The filtrates were not heated (to inactivate the enzymes) before the H2O2 contents were estimated because heating resulted in lower concentrations, and incubation was limited to 30 s in order to prevent slow oxidation of phenol red by other components of the culture filtrate.

Analysis of aromatic metabolites.

Ten-milliliter samples of culture filtrates were adjusted to acid pH values and were extracted twice with 25 ml of diethyl ether. The water was removed with anhydrous Na2SO4, the ether was evaporated under an N2 stream, and the compounds that were extracted were resuspended in 12.5 μl of pyridine (containing 4 μg of ethylvanillin as an internal standard) and derivatized with 20 μl of bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide for 10 min at 50°C. The trimethylsilyl derivatives were analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry by using a type SPB1 column (30 m by 0.25 mm [inside diameter]) which was programmed so that the temperature increased from 100 to 280°C at a rate of 4°C min−1, and they were identified by comparing their mass spectra with mass spectra obtained from the National Bureau of Standards library or mass spectra of standard compounds. Yields were calculated from the peak areas of the different compounds and the internal standard and were corrected with the response factors.

Enzyme purification.

The P. pulmonarius peroxidase was purified from culture filtrates after 64 h of incubation in the medium described above. The purification process included (i) ultrafiltration and dialysis (cutoff, 5 kDa) with 10 mM sodium tartrate (pH 4.5), (ii) Q-cartridge (Bio-Rad) chromatography (to remove laccase and pigment), (iii) Sephacryl S-200 chromatography (to remove AAO), and (iv) Mono-Q chromatography (pH 5) to complete the purification (34).

Evaluation of peroxidase stability.

Peroxidase instability during fungal growth was estimated by incubating culture and culture filtrate samples for several hours at room temperature and then measuring the remaining activity and H2O2 concentration. The effects of different incubation conditions and additives were also determined (the compounds and concentrations used are shown in Tables 1 and 2). Finally, we investigated inactivation of purified peroxidase (700 U/liter) by H2O2 at concentrations ranging from 1.4 to 70 μM at different pH values by using 0.1 M tartrate (pH 3.25 to 5) and 0.1 M phosphate (pH 6).

RESULTS

Production and instability of P. pulmonarius peroxidase in liquid cultures.

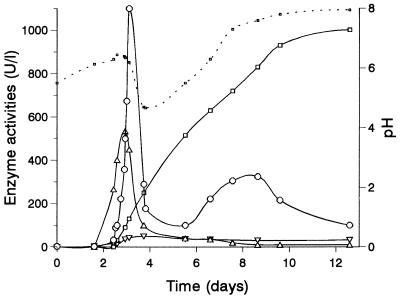

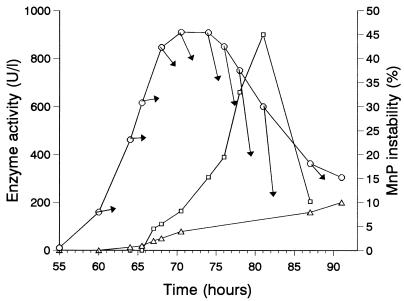

The time courses of extracellular peroxidase, AAO, and laccase activities in a representative culture of P. pulmonarius are shown in Fig. 1. The culture pH values are also shown, and the minimum pH occurred around days 4 and 5. The peroxidase activity exhibited an ephemeral peak around day 3, and there were only a few hours of maximal activity. Samples were collected from P. pulmonarius cultures after different growth periods, and enzymatic activities were monitored in filtrates for several hours. Figure 2 shows the main peroxidase peak together with the time courses of activity in filtrates. The enzyme became unstable just before the maximum level of activity was reached in the culture. The greatest instability in the culture filtrates (45% of the activity was lost after 1 h) was observed after 81 h of growth. In the same filtrates laccase and AAO activities did not change appreciably. In order to determine the cause of the sudden inactivation of peroxidase and to identify conditions that prevented enzyme loss during purification, samples were taken before and after the maximum level of peroxidase activity was observed (corresponding to filtrates with unstable and stable activities shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively), and enzyme inactivation was investigated under different conditions.

FIG. 1.

Time course of extracellular peroxidase activity estimated on the basis of Mn3+-tartrate formation (○), laccase (▵), AAO (□), and proteinase (▿) activities, and pH (.....) during 13 days of growth of P. pulmonarius in glucose-yeast extract-peptone medium. The data are data from a typical culture.

FIG. 2.

Time course of extracellular peroxidase activity estimated on the basis of Mn3+-tartrate formation (○) and AAO activities (▵) in P. pulmonarius cultures during the main peak of peroxidase activity (Fig. 1). The courses of peroxidase activity in culture filtrate samples (taken at different time points and incubated at room temperature) are indicated by arrows. The corresponding peroxidase instability, expressed as the percentage of activity lost 1 h after filtering (□), is also shown.

Factors involved in peroxidase instability.

First, we considered whether extracellular fungal proteinases could be responsible for the enzyme inactivation observed. As shown in Fig. 1, the maximal level of extracellular proteinase activity found in P. pulmonarius cultures was 25 U/liter, and no degradation of azocoll was observed with whole cultures or filtrates. When proteinase inhibitors were used, we observed that most of the activity probably corresponded to serine-type proteinases, since it was inhibited by PMSF and AEBSF, and exhibited neutral or alkaline optimum pH values. Moreover, the effects of the proteinase inhibitors PMSF, AEBSF, EDTA, leupeptin, and pepstatin were tested with an unstable filtrate in which 50% of the peroxidase was inactivated after 2 h, but none of these inhibitors stabilized the enzyme (Table 1).

Second, peroxidase stabilization by different compounds, including some enzyme substrates, was tested by using the unstable filtrate described above (Table 1). Addition of Mn2+ resulted in appreciable stabilization at concentrations greater than 10 μM. Among the other divalent cations tested, only Fe2+ stabilized the enzyme to some extent. Addition of the phenolic substrates p-cresol and 1,6-dichlorophenol also resulted in appreciable stabilization. However, none of the compounds mentioned above was able to reactivate the peroxidase once the activity in the filtrates had been lost. When purified enzyme was added to preincubated filtrates that had lost activity, rapid inactivation of the new enzyme was observed, suggesting that an inactivating factor was present. Because dialysis of the culture filtrate (against 10 mM phosphate buffer at the same pH as the culture pH) resulted in peroxidase stabilization, we concluded that a low-molecular-weight compound was involved in inactivation.

Third, by using scavengers of active oxygen species, we found that neither the superoxide anion radical (O2•−) nor the hydroxyl radical (OH•) was involved, since inactivation was not modified by the presence of superoxide dismutase or mannitol (Table 1). However, addition of catalase resulted in enzyme stabilization, which indicated that H2O2 could be the agent causing inactivation of the enzyme. Moreover, direct addition of H2O2 or generation of H2O2 in cultures and filtrates from methoxybenzylic alcohols (see below) led to peroxidase inactivation. As described above for Mn2+ and phenolic substrates, catalase and/or superoxide dismutase (200 U/ml) did not restore the activity of inactivated peroxidase.

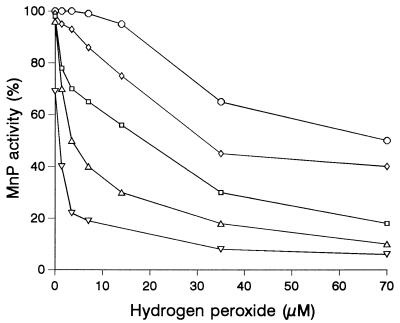

Finally, based on the fact that the decrease in pH observed in cultures paralleled the decrease in the peroxidase peak (Fig. 1), the influence of pH on inactivation by H2O2 was studied (Fig. 3). Purified enzyme was incubated for 1 h with different H2O2 concentrations at different pH values in the absence of reducing substrates. The amount of enzyme used (700 U/liter) corresponded to 0.14 μM, as calculated from a specific activity of 115 U/mg and a molecular mass of 43 kDa (5), which was similar to the concentration found in cultures. At pH 6 the enzyme was quite stable in the presence of H2O2 concentrations up to 15 μM (which corresponded to more than 100 enzyme equivalents). However, at lower pH values the stability decreased, and the same H2O2 concentrations resulted in 70 to 80% peroxidase inactivation at pH values ranging from 3.75 to 3.25.

FIG. 3.

Effect of pH on peroxidase inactivation by H2O2. Purified enzyme from P. pulmonarius (700 U/liter, as estimated on the basis of Mn3+-tartrate formation) was incubated at room temperature with different initial concentrations of H2O2 at different pH values (from top to bottom, pH 6, 5, 4, 3.75, and 3.25). The activities remaining after 1 h are shown.

Production of H2O2.

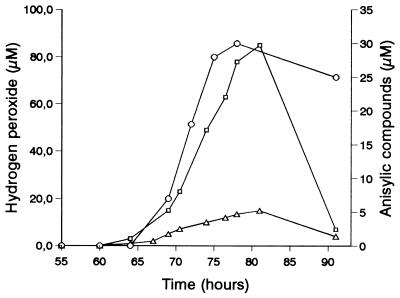

The H2O2 levels found in fresh filtrates obtained from P. pulmonarius cultures are shown in Fig. 4. The onset of H2O2 production and biosynthesis of anisylic compounds coincided with the onset of peroxidase instability (Fig. 2). The total amounts of anisylic compounds (Fig. 4) were estimated by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, including 75 to 95% anisaldehyde and 5 to 25% anisic acid. Both anisaldehyde and anisic acid can participate in H2O2 generation via redox cycling involving cell-bound reducing activities on aromatic aldehydes and acids and AAO extracellular oxidation of the alcohols formed (17, 19).

FIG. 4.

H2O2 concentrations in fresh filtrates from P. pulmonarius cultures (▵) and after incubation of the culture filtrates for 3 h at room temperature (□). The concentrations of anisylic compounds in fresh culture filtrates (○) are also shown.

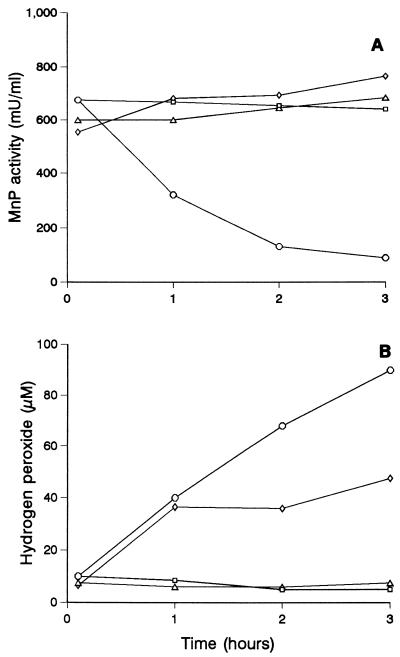

As shown in Fig. 5, H2O2 in filtrates containing unstable peroxidase activity (obtained after 75 h of cultivation) was produced constantly, and the enzyme was inactivated simultaneously. The fact that addition of catalase (and filtrate dialysis) protected the peroxidase against inactivation supported the hypothesis that H2O2 was involved. Similar protection was obtained by adding Mn2+, although the H2O2 levels were only partially lowered. In the case of filtrates containing stable peroxidase (obtained after 64 h of growth), addition of 1 mM veratryl or anisyl alcohol resulted in enzyme inactivation that paralleled H2O2 production (Table 2). As determined for naturally unstable peroxidase, simultaneous addition of catalase or Mn2+ prevented inactivation. The effect of Mn2+ depended on the concentration; significant protection was obtained with 0.1 mM Mn2+. Addition of tartrate as a chelator partially decreased peroxidase stabilization by Mn2+.

FIG. 5.

Peroxidase activity estimated on the basis of Mn3+-tartrate formation (A) and H2O2 concentration (B) during incubation of culture filtrates from 75-h cultures of P. pulmonarius at room temperature (○) and effects of continuous dialysis (□), addition of catalase (100 U/ml) (▵), and addition of 0.1 mM Mn2+ (◊).

DISCUSSION

The action of extracellular proteases has been described by Dosoretz et al. (14) as a major factor that decreases peroxidase levels in cultures of P. chrysosporium, and similar findings have been reported for other ligninolytic fungi (7, 44). In P. chrysosporium two types of proteases were described, and these two types were related to decreases in LiP and MnP levels in both liquid cultures (4, 9, 13) and SSF cultures (10). Therefore, we initially considered whether proteases could be responsible for the rapid decreases in peroxidase activity observed in cultures of P. pulmonarius (33). However, the enzyme was not stabilized by protease inhibitors, including PMSF, which efficiently protects P. chrysosporium peroxidases (12, 13). As discussed below, our results indicate that H2O2 is a major factor in inactivation of the P. pulmonarius peroxidase in cultures.

H2O2 and aromatic metabolites.

H2O2 is required for lignin degradation, as described by Faison and Kirk (15), but it is a strong oxidant that has deleterious effects on living cells. The H2O2 involved in lignin degradation is probably turned over rapidly, and the excess is decomposed by mycelium-associated catalase. This would explain the larger amounts of H2O2 found in culture filtrates than in whole cultures, where the mycelium prevents undesirably high concentrations.

In Pleurotus and Bjerkandera species H2O2 is produced by AAO (11, 17, 20), in contrast to P. chrysosporium, in which H2O2 is generated by glyoxal oxidase (27). Nevertheless, the H2O2 levels found in cultures of P. pulmonarius were similar to the H2O2 levels reported for P. chrysosporium (45). The present study revealed that P. pulmonarius is a good AAO producer, and the levels obtained were the highest levels reported for this enzyme. AAO exhibits high levels of activity with anisylic alcohol and other primary aromatic alcohols and low levels of activity with some aromatic aldehydes (18). It has been reported that the basidiomycetes are able to synthesize a variety of phenolic and nonphenolic aromatic compounds, such as vanillin (16), veratryl alcohol (43), and anisaldehyde (20). In addition, during growth on natural substrates simple aromatic compounds are released as a result of lignin depolymerization (8). We suggest that the cyclic H2O2-producing system proposed by Guillén and Evans (17) for P. eryngii, involving extracellular AAO and mycelium-associated dehydrogenases acting on anisylic and other aromatic compounds, is responsible for H2O2 generation in P. pulmonarius cultures. The balance among the aromatic alcohols, aldehydes, and acids depends on the efficiency of the oxidizing and reducing systems (17, 20), and due to the high level of AAO activity in P. pulmonarius, anisaldehyde predominates in cultures of this organism. It is necessary to point out that production of anisylic compounds in P. pulmonarius cultures starts a few hours before the time when the maximal levels of H2O2 are observed, which coincides with the time when the greatest peroxidase instability is observed.

In culture filtrates, the redox cycle is interrupted since the reducing counterpart, the mycelium, is absent. Any traces of anisyl alcohol are quickly oxidized. Since AAO exhibits broad substrate specificity (17), we postulated that the slow generation of H2O2 in filtrates was maintained by AAO activity with other aromatic substrates. These substrates could include phenolic or nonphenolic aromatic alcohols present in cultures of P. pulmonarius and related species (20). As shown by Guillén and Evans (17), the concentrations of some benzylic alcohols (substrates of AAO) are relatively high in the presence of Pleurotus mycelium because of the balance between oxidizing and reducing enzymatic activities (whereas mainly anisaldehyde is found during incubation with anisylic compounds). Other mechanisms could also generate H2O2; for example, we confirmed that Mn-mediated production of H2O2 occurred after glyoxylate was added to culture filtrates of P. pulmonarius (data not shown). However, this type of reaction (31) may not have been involved in peroxidase inactivation because the presence of Mn2+ would have protected the enzyme.

Peroxidase inactivation and protection.

Inactivation of P. chrysosporium LiP and MnP by H2O2 has been investigated previously. Odier and Artaud (37) reported that LiP is more sensitive to an excess of H2O2 (compound III formation by 25 equivalents of H2O2) than MnP (250 H2O2 equivalents required) and HRP (500 H2O2 equivalents required) are, but differences in the reaction pH values (usually pH 3 for LiP, pH 4.5 for MnP, and around pH 6 for HRP) should be taken into account. The P. pulmonarius peroxidase is inactivated by H2O2, and the susceptibility of this enzyme varies with pH. In this way, addition of 250 equivalents of H2O2 (corresponding to 35 μM H2O2 under our experimental conditions) resulted in more than 90% inactivation of this peroxidase at pH 3, around 60% inactivation at pH 4.5, and only 30% inactivation at pH 6. This effect of pH on peroxidase stability is important in order to understand the inactivation of the enzyme in P. pulmonarius cultures, in which a sudden decrease in pH is observed near the peak of peroxidase activity. Compared with P. chrysosporium peroxidases, the P. pulmonarius enzyme appears to be more resistant to an excess of H2O2 than MnP is at pH 4.5, and it exhibited resistance similar to that of LiP at lower pH values. It is interesting that the maximal peroxidase instability found in cultures was nearly the same as the maximal peroxidase instability observed after we incubated purified peroxidase under H2O2 concentration conditions (ca. 15 μM) and pH conditions (ca. pH 4.5) similar to those found in the unstable cultures.

The experiments designed to stabilize P. pulmonarius peroxidase provided information about the way in which inactivation is caused. The enzyme was stabilized by reducing substrates, such as phenols and Mn2+. Stabilization of HRP in the presence of H2O2 by phenols has been described by Halliwell (21), and veratryl alcohol acts as a LiP stabilizer in P. chrysosporium cultures (6, 45). Although veratryl alcohol can be oxidized by P. pulmonarius peroxidase, addition of this compound to cultures resulted in rapid peroxidase inactivation because it is a better substrate of AAO (18) than of peroxidase (33) (and strongly promotes H2O2 generation). Addition of Mn2+ efficiently protected the P. pulmonarius peroxidase against inactivation, but only a partial decrease in the H2O2 concentration was observed. This suggests that H2O2 generation continues in the presence of Mn2+ and that this compound acts as a reductant of the oxidized enzyme which prevents formation of compound III and peroxidase bleaching, as described previously for LiP (46). Protection of the enzyme by low Mn2+ concentrations implies that Mn3+ is recycled, probably by oxidation of H2O2 to O2•−(1), whereas the lower level of protection provided by phenols could be related to difficulties in product recycling. During peroxidase purification from Pleurotus liquid cultures, addition of about 100 μM MnSO4 before separation of the mycelium stabilizes the peroxidase during the critical steps, ultrafiltration and dialysis. Peroxidase inactivation by the mechanism described here does not seem to occur during fungal growth on lignocellulosic substrates because the vanillin and syringaldehyde (and corresponding acids) released during oxidative depolymerization of lignin probably act as electron donors for Pleurotus peroxidase. This conclusion is supported by the results of Camarero et al. (5), who showed that extended peroxidase production occurred from weeks 1 to 4, when P. pulmonarius was grown on wheat straw under SSF conditions.

TABLE 1.

Effects of different compounds and enzymes as stabilizers of P. pulmonarius peroxidase: experiments performed with filtrates from 75-h cultures exhibiting unstable peroxidase activity (estimated on the basis of Mn3+-tartrate formation)

| Prepn or compound | % Activity after incubation for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 h | 2 h | 24 h | |

| Control filtrate | 90 | 54 | 0 |

| PMSF (0.1 mM)a | 90 | 54 | 0 |

| MnSO4 (0.01 mM) | 96 | 88 | 41 |

| MnSO4 (0.1 mM) | 109 | 93 | 73 |

| MnSO4 (1 mM) | 120 | 116 | 94 |

| FeSO4 (1 mM) | 101 | 94 | 58 |

| CaCl2 (1 mM) | 90 | 60 | 0 |

| CuSO4 (1 mM)b | 95 | 65 | 0 |

| p-Cresol (1 mM) | 94 | 83 | 43 |

| 1,6-Dichlorophenol (1 mM) | 95 | 90 | 68 |

| Catalase (100 U/ml)c | 96 | 86 | |

| Superoxide dismutase (100 U/ml) | 91 | 50 | 0 |

| Mannitol (5 mM) | 90 | 46 | 0 |

The same results were obtained with 1 mg of AEBSF per ml, 1 mM EDTA, 1 μM leupeptin, or 1 μM pepstatin.

The same results were obtained with 1 mM MgSO4.

We confirmed that 100 U of catalase per ml did not affect the initial Mn2+ oxidation rate.

TABLE 2.

H2O2 production and inactivation of P. pulmonarius peroxidase by aromatic compounds and protection by Mn2+ and enzymes: experiments performed with filtrates from 64-h cultures exhibiting initially stable peroxidase activity (estimated on the basis of Mn3+-tartrate formation)

| Prepn or compound(s) | H2O2 concn (μM) after incubation for:

|

% Activity after incubation for:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 h | 1 h | 20 h | 0.5 h | 1 h | 20 h | |

| Control filtrate | 0 | 0 | 0 | 106 | 106 | 102 |

| Veratryl alcohol (1 mM) | 203 | 275 | 670 | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| Anisyl alcohol (1 mM) | 277 | 363 | 760 | 8 | 1 | 0 |

| Anisyl alcohol (1 mM) + MnSO4 (0.01 mM) | 247 | 161 | 530 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Anisyl alcohol (1 mM) + MnSO4 (0.1 mM) | 69 | 99 | 10 | 82 | 79 | 73 |

| Anisyl alcohol (1 mM) + MnSO4 (0.1 mM) + tartratea | 94 | 65 | 14 | 39 | 34 | 30 |

| Anisyl alcohol (1 mM) + MnSO4 (1 mM) | 102 | 59 | 25 | 118 | 124 | 118 |

| Anisyl alcohol (1 mM) + catalase (100 U/ml)b | 43 | 37 | 0 | 93 | 86 | 67 |

| Anisyl alcohol (1 mM) + superoxide dismutase (100 U/ml) | 314 | 361 | 579 | 26 | 2 | 0 |

The tartrate used was 50 mM sodium tartrate (pH 5).

Catalase was added every 2 h.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Prieto for the gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analyses and C. Rodríguez for skillful technical assistance.

B.B. thanks the HCM Programme and the FAIR Programme of the European Union for two postdoctoral fellowships supporting her stay at the Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas (Madrid). This work was supported by project BIO96-393 (Evaluation of Enzymatic and Radical-Mediated Mechanisms in Lignin Degradation by Fungi from the Genera Pleurotus and Phanerochaete) of the Spanish Biotechnology Program and by project AIR2-CT93-1219 (Biological Delignification in Paper Manufacture) of the European Union.

REFERENCES

- 1.Archibald F S, Fridovich I. The scavenging of superoxide radical by manganous complexes: in vitro. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1982;214:452–463. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asada Y, Watanabe A, Irie T, Nakayama T, Kuwahara M. Structures of genomic and complementary DNAs coding for Pleurotus ostreatus manganese(II) peroxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1251:205–209. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(95)00102-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrasa J M, González A E, Martínez A T. Ultrastructural aspects of fungal delignification of Chilean woods by Ganoderma australe and Phlebia chrysocrea: a study of natural and in vitro degradation. Holzforschung. 1992;46:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonnarme P, Asther M. Influence of primary and secondary proteases produced by free or immobilized cells of the white-rot fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium on lignin peroxidase activity. J Biotechnol. 1993;30:271–282. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camarero S, Böckle B, Martínez M J, Martínez A T. Manganese-mediated lignin degradation by Pleurotus pulmonarius. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1070–1072. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.1070-1072.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cancel A M, Orth A B, Tien M. Lignin and veratryl alcohol are not inducers of the ligninolytic system of Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2909–2913. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.9.2909-2913.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caporale C, Garzillo A M V, Caruso C, Buonocore V. Characterization of extracellular proteases from Trametes trogii. Phytochemistry. 1996;41:385–393. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(96)83284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C-L, Chang H-M. Chemistry of lignin biodegradation. In: Higuchi T, editor; Higuchi T, editor. Biosynthesis and biodegradation of wood components. Orlando, Fla: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 535–555. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dass S B, Dosoretz C G, Reddy C A, Grethlein H E. Extracellular proteases produced by the wood-degrading fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium under ligninolytic and non-ligninolytic conditions. Arch Microbiol. 1995;163:254–258. doi: 10.1007/BF00393377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Datta A. Purification and characterization of a novel protease from solid substrate cultures of Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:728–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Jong E, Cazemier A E, Field J A, de Bont J A M. Physiological role of chlorinated aryl alcohols biosynthesized de novo by the white rot fungus Bjerkandera sp. strain BOS55. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:271–277. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.1.271-277.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dey S, Maiti T K, Saha N, Banerjee R, Bhattacharya B C. Extracellular protease and amylase activities in ligninase-producing liquid culture of Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Process Biochem. 1991;26:325–329. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dosoretz C G, Chen H-C, Grethlein H E. Effect of environmental conditions on extracellular protease activity in lignolytic cultures of Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:395–400. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.2.395-400.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dosoretz C G, Dass S B, Reddy C A, Grethlein H E. Protease-mediated degradation of lignin peroxidase in liquid cultures of Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3429–3434. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.11.3429-3434.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faison B D, Kirk T K. Relationship between lignin degradation and production of reduced oxygen species by Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;46:1140–1145. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.5.1140-1145.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feron G, Bonnarme P, Durand A. Prospects for the microbial production of food flavours. Trends Food Sci Technol. 1996;7:285–293. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guillén F, Evans C S. Anisaldehyde and veratraldehyde acting as redox cycling agents for H2O2 production by Pleurotus eryngii. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2811–2817. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.8.2811-2817.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guillén F, Martínez A T, Martínez M J. Substrate specificity and properties of the aryl-alcohol oxidase from the ligninolytic fungus Pleurotus eryngii. Eur J Biochem. 1992;209:603–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guillén F, Martínez A T, Martínez M J, Evans C S. Hydrogen peroxide-producing system of Pleurotus eryngii involving the extracellular enzyme aryl-alcohol oxidase. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1994;41:465–470. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gutiérrez A, Caramelo L, Prieto A, Martínez M J, Martínez A T. Anisaldehyde production and aryl-alcohol oxidase and dehydrogenase activities in ligninolytic fungi from the genus Pleurotus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1783–1788. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.6.1783-1788.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halliwell B. Lignin synthesis: the generation of hydrogen peroxide and superoxide by horseradish peroxidase and its stimulation by manganese(II) and phenols. Planta. 1978;140:81–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00389384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hatakka A. Lignin-modifying enzymes from selected white-rot fungi—production and role in lignin degradation. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;13:125–135. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinfling A, Martínez M J, Martínez A T, Bergbauer M, Szewzyk U. Purification and characterization of peroxidases from the dye-decolorizing fungus Bjerkandera adusta. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;165:43–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heinfling A, Martínez M J, Martínez A T, Bergbauer M, Szewzyk U. Transformation of industrial dyes by manganese peroxidase from Bjerkandera adusta and Pleurotus eryngii in a Mn-independent reaction. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2788–2793. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.8.2788-2793.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heinfling A, Ruiz-Dueãs F J, Martínez M J, Bergbauer M, Szewzyk U, Martínez A T. A study on reducing substrates of manganese-oxidizing peroxidases from Pleurotus eryngii and Bjerkandera adusta. FEBS Lett. 1998;428:141–146. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00512-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamra D N, Zadrazil F. Influence of gaseous phase, light and substrate pretreatment on fruit-body formation, lignin degradation and in vitro digestibility of wheat straw fermented with Pleurotus spp. Agric Wastes. 1986;18:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kersten P J, Kirk T K. Involvement of a new enzyme, glyoxal oxidase, in extracellular H2O2 production by Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2195–2201. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.5.2195-2201.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimura Y, Asada Y, Kuwahara M. Screening of basidiomycetes for lignin peroxidase genes using a DNA probe. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1990;32:436–442. doi: 10.1007/BF00903779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirk T K, Farrell R L. Enzymatic “combustion”: the microbial degradation of lignin. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1987;41:465–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.002341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kishi K, Wariishi H, Marquez L, Dunford H B, Gold M H. Mechanism of manganese peroxidase compound II reduction. Effect of organic acid chelators and pH. Biochemistry. 1994;33:8694–8701. doi: 10.1021/bi00195a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuan I C, Tien M. Glyoxylate-supported reactions catalyzed by Mn peroxidase of Phanerochaete chrysosporium—activity in the absence of added hydrogen peroxide. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;302:447–454. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martínez A T, Camarero S, Guillén F, Gutiérrez A, Muñoz C, Varela E, Martínez M J, Barrasa J M, Ruel K, Pelayo M. Progress in biopulping of non-woody materials: chemical, enzymatic and ultrastructural aspects of wheat-straw delignification with ligninolytic fungi from the genus Pleurotus. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;13:265–274. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martínez M J, Böckle B, Camarero S, Guillén F, Martínez A T. MnP isoenzymes produced by two Pleurotus species in liquid culture and during wheat straw solid-state fermentation. In: Jeffries T W, Viikari L, editors; Jeffries T W, Viikari L, editors. Enzymes for pulp and paper processing. Washington, D.C: American Chemical Society; 1996. pp. 183–196. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martínez M J, Ruiz-Dueñas F J, Guillén F, Martínez A T. Purification and catalytic properties of two manganese-peroxidase isoenzymes from Pleurotus eryngii. Eur J Biochem. 1996;237:424–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0424k.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mester T, Field J A. Characterization of a novel manganese peroxidase-lignin peroxidase hybrid isozyme produced by Bjerkandera species strain BOS55 in the absence of manganese. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15412–15417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muñoz C, Guillén F, Martínez A T, Martínez M J. Laccase isoenzymes of Pleurotus eryngii: characterization, catalytic properties and participation in activation of molecular oxygen and Mn2+ oxidation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2166–2174. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2166-2174.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Odier E, Artaud I. Degradation of lignin. In: Winkelmann G, editor; Winkelmann G, editor. Microbial degradation of natural products. Weinheim, Germany: VCH; 1992. pp. 161–191. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peláez F, Martínez M J, Martínez A T. Screening of 68 species of basidiomycetes for enzymes involved in lignin degradation. Mycol Res. 1995;99:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pick E, Keisari Y. A simple colorimetric method for the measurement of hydrogen peroxide produced by cells in culture. J Immunol Methods. 1980;38:161–170. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(80)90340-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roy B P, Dumonceaux T, Koukoulas A A, Archibald F S. Purification and characterization of cellobiose dehydrogenases from the white rot fungus Trametes versicolor. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4417–4427. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.12.4417-4427.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruiz-Dueñas F J, Martínez M J, Martínez A T. Molecular characterization of a novel peroxidase isolated from the ligninolytic fungus Pleurotus eryngii. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:223–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sarkar S, Martínez A T, Martínez M J. Biochemical and molecular characterization of a manganese peroxidase isoenzyme from Pleurotus ostreatus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1339:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(96)00201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimada M, Nakatsubo F, Kirk T K, Higuchi T. Biosynthesis of the secondary metabolite veratryl alcohol in relation to lignin degradation by Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Arch Microbiol. 1981;129:321–324. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Staszczak M, Nowak G, Grzywnowicz K, Leonowicz A. Proteolytic activities in cultures of selected white-rot fungi. J Basic Microbiol. 1996;36:193–203. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tonon F, Odier E. Influence of veratryl alcohol and hydrogen peroxide on ligninase activity and ligninase production by Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:466–472. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.2.466-472.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wariishi H, Gold M H. Lignin peroxidase compound III. Mechanism of formation and decomposition. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2070–2077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]