“However beautiful the strategy, you should occasionally look at the results.” is a famous saying by Sir Winston Churchill. In this issue of Critical Care Medicine, Stockmann et al (1) did exactly that by looking at the result of a well-performed randomized controlled trial in which they investigated an intriguing strategy, namely the use of a cytokine adsorber, in patients with COVID-19 in vasoplegic shock (2). In contrast to a growing popular belief, they neither showed any difference in the need for catecholamines nor in the mortality nor in other secondary outcomes, including interleukin (IL)-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels.

For 2 years, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that causes the COVID-19 has had a serious impact on global health. Especially prior to the advent of prevention by vaccinations and pharmacologic treatment in the early phase of the disease in nonhospitalized patients like remdesivir or antibody-mediated strategies, the armamentarium for the treatment of critically ill patients was basically limited to dexamethasone (3). On this background, extracorporeal treatments with different targets in nonidentical phases of the disease process have been explored in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Therapeutic plasma exchange using fresh frozen plasma is applied to optimize the von Willebrand factor/a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13 ratio (4). A pathogen adsorber is employed in the early phase of the disease to reduce SARS-Cov-2 viremia (5, 6). Among the most frequently used interventions are aimed to reduce the cytokine storm in COVID-19 patients. In 2011, CytoSorb was licensed in the European Union as single-use hemoperfusion device containing adsorbent polymer beads designed to remove substances in the molecular weight range between 8 and 50 kDa. Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines can be found in that range. Recently removal of ticagrelor and rivaroxaban by CytoSorb has been postulated in patients undergoing emergency heart operation (7). On April 10, 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted Emergency Use Authorization for CytoSorb use in critically ill COVID-19 patients with confirmed or imminent respiratory failure.

In the single-center pilot trial, Stockmann et al (1) enrolled 50 severely ill patients with need for norepinephrine greater than 0.2 µg/kg/min to maintain mean arterial pressure greater than or equal to 65 mm Hg, a CRP greater than 100 mg/L, and an acute kidney injury (AKI) stage 3 with need for kidney replacement therapy (KRT) (2). The median time to resolution of vasoplegia, the primary endpoint, was similar between both groups as was the secondary endpoint mortality rate. Furthermore, other secondary outcome parameters (inflammatory markers, catecholamine requirements, and the type and rates of adverse events) were similar between the groups. Based on these data, the authors concluded that in severely ill COVID-19 patients, cytokine adsorption did not improve resolution of vasoplegic shock.

What could have prevented the success of the intervention by cytokine adsorption in the study by Stockmann et al (1)?

Cytokine storm is characterized by elevated levels of circulating cytokines and immune-cell hyperactivation that can be triggered by various causes. Some authors argue that there is no cytokine storm in COVID-19 (8) but rather a dysregulation in hepatocyte growth factor and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 13 (9). Indeed, systemic concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines in patients with severe COVID-19 are not as high as has been reported in patients with other causes of acute respiratory distress syndrome. The study results by Stockmann et al (1) are in line with the results of another randomized controlled study in patients with septic shock and multiple organ failure in which CytoSorb removed IL-6, but the removal had no effect on systemic IL-6-levels (10). So calming the storm, as one of the miracles of Jesus in a fierce storm sailing the Sea of Galilee, seems to be a challenging endeavor.

Second, intervention might have been initiated too late (referring to the time from admission as well as the state of the disease). Indeed, median time since ICU admission to the start of the treatment was 15 days for CytoSorb and 10 days in the control group. Further, the enrolled patients had not only vasoplegic shock but also AKI and acute respiratory failure. All patients required invasive mechanical ventilation and almost half of them required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) therapy. Yet from a practical point of view, the authors managed to start the treatment within 24 hours of shock in 11 patients and in 12 patients treatment was started after 24 hours. Cox regression analysis revealed no benefit in starting the therapy within 24 hours, although the number of patients was limited. Could a concomitant start of treatment along with ECMO therapy have made a difference? The recent data by Supady et al (11) see no benefit of this strategy.

Third, CytoSorb is known to remove drugs including antibiotics (12) and antivirals like remdesivir (13), so the treatment group might have suffered from underdosing of anti-infective drugs. This is especially relevant as half of the patients also had positive microbiological cultures at the time of study inclusion. Although therapeutic drug monitoring data are not available, the authors proactively addressed this point by giving an extra dose of antibiotics and remdesivir in the CytoSorb group with each filter change.

Last, as in previous trials, CytoSorb was not used as a stand-alone extracorporeal treatment but rather was used in combination with KRT, which might also have had a positive or negative impact. This will also make future studies with CytoSorb (14) difficult to interpret as KRT per se, as well as the anticoagulation might have an impact on patient outcome (15).

In a prospective, randomized, open-label study, Supady et al (11) investigated 34 COVID-19 patients with ECMO therapy and showed that the median IL-6 drop over 72 hours occurred regardless of the use of CytoSorb (11). Thirty-day mortality was significantly higher in the CytoSorb group as compared with the control group (11). With that study in mind, although underpowered for mortality, it is comforting that the study by Stockmann et al (1) did show an absence of benefit and no sign of potential harm.

Our collective hope that we not only understood but also could readily manipulate the inflammatory response by reducing pro-inflammatory mediators has been proven incorrect in several trials. We now recognize the inflammatory response to include complex mechanisms propagated through networks of pro- and anti-inflammatory mediator. Addressing only a small part of that network, such as with a single or even several anti-inflammatory treatment, has proven ineffective. Similarly, the use of a single nonspecific sorbent is equally unlikely to have a predictable salutary effect. Furthermore, molecular neutralization or physical adsorption may trigger unanticipated and even adverse consequences.

Outside of the setting of controlled prospective trials, the rationale use of CytoSorb is questionable because of the lack of results. Data from a U.S. registry https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.773461 over a period of 1 year indicates in 52 patients receiving venovenous ECMO plus CytoSorb therapy an ICU mortality of 17.3% (9/52) on day 30 and 26.9% (14/52) on day 90. CytoSorb was well-tolerated without any device-related adverse events reported. It is of note the percentage of patients also requiring KRT was only 21%. Therapeutic plasma exchange was used in 5.7% of the patients.

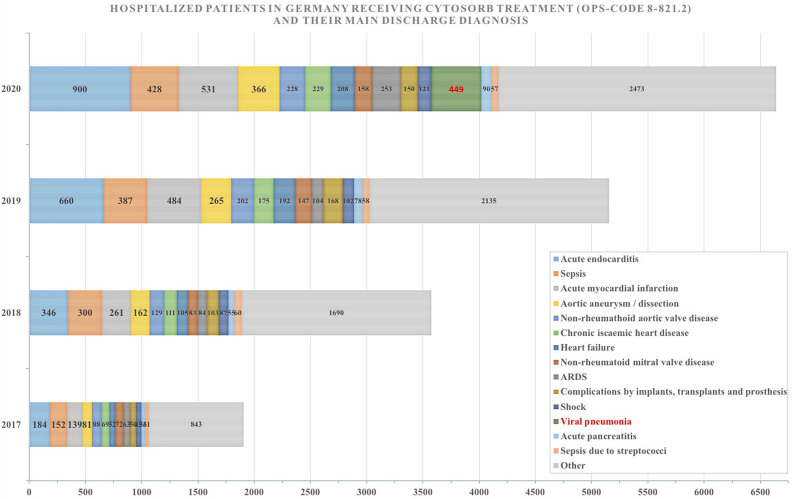

Churchill’s daughter, Marigold, died of septicemia in 1921. One-hundred years later, we aim to save as many lives as possible amidst a pandemic health crisis. Does this justify using untested devices like Cytosorb? In the early phase of the pandemic, it was among treatment options that needed to be explored. Unfortunately, we do only have a small number of the (at least) 449 patients that received CytoSorb in Germany in 2020 for “viral pneumonia” in studies. The same holds true for many extracorporeal procedures worldwide.

Even more relevant is the use of CytoSorb in patients with infective endocarditis. The Revealing Mechanisms and Investigating Efficiency Of Hemoadsorption for Prevention of Vasodilatory Shock in Cardiac Surgery Patients with Infective Endocarditis trial, the biggest (about 140 patients per arm) randomized controlled, publicly funded study with the CytoSorb (16). The trial failed to reach its primary endpoint, an improvement of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score, as well as other secondary endpoints. Will this keep cardiovascular surgeons from using it and insurance companies paying for it in the future?

In the era of evidence-based medicine, we need new strategies to build a solid database for new interventions and devices. Small companies need to get a chance to bring new—and at times disruptive therapies—to the market. In an ideal world, they should not need to generate enough revenue for controlled randomized, adequately powered trials themselves but should partner with healthcare systems and healthcare providers. In 2020, insurance companies in Germany payed for (sometimes multiple) CytoSorb treatments in at least 6,600 patients without increasing the evidence level to today’s standards (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Patients that received at least one Cytosorb treatment in Germany from 2017 to 2020 as well as their primary discharge diagnosis (Statistisches Bundesamt [Destatis], Wiesbaden, Germany). The actual number of treatments per patient is not known. ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome, OPS-CODE = Operation and Procedure Code.

To paraphrase Winston Churchill’s saying, no matter how intriguing the mechanisms behind a proposed therapeutic strategy might be, the intervention must still be substantiated by positive results of well designed and adequately powered clinical trials. Stockmann et al (1) should be commended for doing precisely that—and those challenging the results by Stockmann et al (1) should present compelling evidence from prospective randomized studies.

Footnotes

*See also p. 964.

Drs. Kielstein and Zarbock wrote the article. Dr. Kielstein analyzed the data of the Statistische Bundesamt on CytoSorb treatments in Germany.

Dr. Kielstein was funded by intramural grants. Dr. Zarbock received grants from the German Research Foundation (KFO342-1, ZA428/18-1, and ZA428/21-1 to Dr. Zarbock).

Dr. Kielstein received research grants from ExThera Medical and speaker fees from Fresenius Medical Care. Dr. Zarbock’s institution received funding from Astute Medical, Baxter, Fresenius, Astellas Medical, BioMereiux, Bayer, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, and German-Israeli Foundation; he received funding from Novartis, AM Pharma, Guard Therapeutics, Paion, La Jolla Pharmaceuticals, Baxter, Fresenius, Astellas Medial, BioMereiux, and Bayer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stockmann H, Thelen P, Stroben F, et al. : CytoSorb Rescue for COVID-19 Patients With Vasoplegic Shock and Multiple Organ Failure: A Prospective, Open-Label, Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. Crit Care Med 2022; 50:964–976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stockmann H, Keller T, Büttner S, et al. ; CytoResc Trial Investigators: CytoResc - “CytoSorb” rescue for critically ill patients undergoing the COVID-19 cytokine storm: A structured summary of a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2020; 21:577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al. ; RECOVERY Collaborative Group: Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19 - preliminary report. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:693–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doevelaar AAN, Bachmann M, Holzer B, et al. : von Willebrand factor multimer formation contributes to immunothrombosis in coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Med 2021; 49:e512–e520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt JJ, Borchina DN, Klooster MVT, et al. : Interim-analysis of the COSA (COVID-19 patients treated with the Seraph® 100 Microbind® Affinity filter) registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2021 Dec 7. [online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kielstein JT, Borchina DN, Fühner T, et al. : Hemofiltration with the Seraph® 100 Microbind® Affinity filter decreases SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Crit Care 2021; 25:190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hassan K, Kannmacher J, Wohlmuth P, et al. : Cytosorb adsorption during emergency cardiac operations in patients at high risk of bleeding. Ann Thorac Surg 2019; 108:45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinha P, Matthay MA, Calfee CS: Is a “Cytokine Storm” Relevant to COVID-19? JAMA Intern Med 2020; 180:1152–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perreau M, Suffiotti M, Marques-Vidal P, et al. : The cytokines HGF and CXCL13 predict the severity and the mortality in COVID-19 patients. Nat Commun 2021; 12:4888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schädler D, Pausch C, Heise D, et al. : The effect of a novel extracorporeal cytokine hemoadsorption device on IL-6 elimination in septic patients: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2017; 12:e0187015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Supady A, Weber E, Rieder M, et al. : Cytokine adsorption in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (CYCOV): A single centre, open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9:755–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.König C, Röhr AC, Frey OR, et al. : In vitro removal of anti-infective agents by a novel cytokine adsorbent system. Int J Artif Organs 2019; 42:57–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biever P, Staudacher DL, Sommer MJ, et al. : Hemoadsorption eliminates remdesivir from the circulation: Implications for the treatment of COVID-19. Pharmacol Res Perspect 2021; 9:e00743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanjo A, Molnar Z, Zádori N, et al. : Dosing of Extracorporeal Cytokine Removal In Septic Shock (DECRISS): Protocol of a prospective, randomised, adaptive, multicentre clinical trial. BMJ Open 2021; 11:e050464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zarbock A, Küllmar M, Kindgen-Milles D, et al. ; RICH Investigators and the Sepnet Trial Group: Effect of regional citrate anticoagulation vs systemic heparin anticoagulation during continuous kidney replacement therapy on dialysis filter life span and mortality among critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020; 324:1629–1639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diab M, Platzer S, Guenther A, et al. : Assessing efficacy of CytoSorb haemoadsorber for prevention of organ dysfunction in cardiac surgery patients with infective endocarditis: REMOVE-protocol for randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2020; 10:e031912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]