Abstract

Background

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a painful and disabling condition that usually manifests in response to trauma or surgery and is associated with significant pain and disability. CRPS can be classified into two types: type I (CRPS I) in which a specific nerve lesion has not been identified and type II (CRPS II) where there is an identifiable nerve lesion. Guidelines recommend the inclusion of a variety of physiotherapy interventions as part of the multimodal treatment of people with CRPS. This is the first update of the review originally published in Issue 2, 2016.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions for treating pain and disability associated with CRPS types I and II in adults.

Search methods

For this update we searched CENTRAL (the Cochrane Library), MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, LILACS, PEDro, Web of Science, DARE and Health Technology Assessments from February 2015 to July 2021 without language restrictions, we searched the reference lists of included studies and we contacted an expert in the field. We also searched additional online sources for unpublished trials and trials in progress.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of physiotherapy interventions compared with placebo, no treatment, another intervention or usual care, or other physiotherapy interventions in adults with CRPS I and II. Primary outcomes were pain intensity and disability. Secondary outcomes were composite scores for CRPS symptoms, health‐related quality of life (HRQoL), patient global impression of change (PGIC) scales and adverse effects.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened database searches for eligibility, extracted data, evaluated risk of bias and assessed the certainty of evidence using the GRADE system.

Main results

We included 16 new trials (600 participants) along with the 18 trials from the original review totalling 34 RCTs (1339 participants). Thirty‐three trials included participants with CRPS I and one trial included participants with CRPS II. Included trials compared a diverse range of interventions including physical rehabilitation, electrotherapy modalities, cortically directed rehabilitation, electroacupuncture and exposure‐based approaches. Most interventions were tested in small, single trials. Most were at high risk of bias overall (27 trials) and the remainder were at 'unclear' risk of bias (seven trials). For all comparisons and outcomes where we found evidence, we graded the certainty of the evidence as very low, downgraded due to serious study limitations, imprecision and inconsistency. Included trials rarely reported adverse effects.

Physiotherapy compared with minimal care for adults with CRPS I

One trial (135 participants) of multimodal physiotherapy, for which pain data were unavailable, found no between‐group differences in pain intensity at 12‐month follow‐up. Multimodal physiotherapy demonstrated a small between‐group improvement in disability at 12 months follow‐up compared to an attention control (Impairment Level Sum score, 5 to 50 scale; mean difference (MD) ‐3.7, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐7.13 to ‐0.27) (very low‐certainty evidence). Equivalent data for pain were not available. Details regarding adverse events were not reported.

Physiotherapy compared with minimal care for adults with CRPS II

We did not find any trials of physiotherapy compared with minimal care for adults with CRPS II.

Authors' conclusions

The evidence is very uncertain about the effects of physiotherapy interventions on pain and disability in CRPS. This conclusion is similar to our 2016 review. Large‐scale, high‐quality RCTs with longer‐term follow‐up are required to test the effectiveness of physiotherapy‐based interventions for treating pain and disability in adults with CRPS I and II.

Plain language summary

Does physiotherapy improve pain and disability in adults with complex regional pain syndrome?

Key messages

We are very uncertain if physiotherapy treatments improve the pain and disability associated with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS).

We are very uncertain because the clinical trials we found:

‐ were not conducted or reported as well as they could have been (or both);

‐ included small numbers of patients with CRPS;

‐ tested a large range of different types of physiotherapy treatments; and

‐ because there were a limited number of trials that investigated any particular physiotherapy treatment.

We are very uncertain if physiotherapy treatments cause unwanted side effects; more evidence is required to clarify this.

Good‐quality clinical trials are required to further investigate whether or not physiotherapy treatments improve the pain and disability associated with CRPS.

Treating pain and disability in adults with complex regional pain syndrome

Complex regional pain syndrome is a painful and disabling condition that can occur after trauma or surgery and is associated with significant pain and disability. CRPS can be classified into two types: type I (CRPS I) in which a specific nerve injury has not been identified and type II (CRPS II) where there is an identifiable nerve injury. Guidelines recommend that physiotherapy rehabilitation should be included as part of the treatment for CRPS. Physiotherapy for CRPS could include a range of treatments and rehabilitation approaches, such as exercise, pain management, manual therapy, electrotherapy or advice and education, either used alone or in combination. Physiotherapy is recommended because it is thought that it may improve the pain and disability associated with CRPS.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out if physiotherapy treatments improve pain and disability in adults (aged over 18) with CRPS.

What did we do?

We searched for clinical trials that involved adults with CRPS, which compared physiotherapy treatments to placebo treatments or routine care or which compared different physiotherapy treatments to each other.

We compared and summarised the results of the studies and rated our confidence in the evidence, based on factors such as trial methods, size and length of follow‐up.

What did we find?

We found 33 clinical trials that involved 1317 people in total with CRPS type I of the upper or lower limb, or both. The trials investigated the effect of a range of physiotherapy treatments. We found only one trial involving 22 people with CRPS type II.

Here we present the findings from comparisons between different physiotherapy treatments and placebo treatments or routine care and for comparisons of different physiotherapy treatments to each other.

Reducing pain

We are uncertain if any of the physiotherapy treatments investigated in the clinical trials we identified help reduce the pain associated with CRPS.

Reducing disability

We are uncertain if any of the physiotherapy treatments investigated in the clinical trials we identified help reduce the disability associated with CRPS.

Side effects

We are uncertain if any of the physiotherapy treatments investigated in the clinical trials we identified cause any unwanted side effects.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

Clinical trials were small and most have been conducted in ways that could introduce errors into their results. This limited our confidence in the evidence.

How up to date is the evidence?

The evidence is up to date to July 2021.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Physiotherapy compared with minimal care for adults with CRPS I.

| Physiotherapy compared with minimal care for adults with CRPS I | ||||

|

Patient or population: adults with CRPS I Settings: outpatient clinic Intervention: multimodal physiotherapy Comparison: 'social work' (i.e. passive attention, advice) | ||||

| Outcomes | Effect size (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Oerlemans 1999 Pain (VAS 0 to 100) |

Not estimable | — | — | — |

|

Oerlemans 1999 Disability as measured by the impairment level sum score (5 to 50) Higher scores indicate greater impairment Measured 12 months post recruitment |

MD ‐3.7 95% CI ‐7.13 to 0.27 |

91 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c |

One study found evidence of a small beneficial effect of physiotherapy compared to 'social work' (i.e. an attention and advice control) intervention |

| Incidence/nature of adverse effects | Not estimable | — | — | Data not reported |

| CI: confidence interval; CRPS I: complex regional pain syndrome type I; MD: mean difference; VAS: visual analogue scale | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect; Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||

aDowngraded once for serious study limitations.

bDowngraded once for inconsistency.

cDowngraded once for imprecision.

Summary of findings 2. Physiotherapy compared with minimal care for adults with CRPS II.

| Physiotherapy compared with minimal care for adults with CRPS II | ||||

|

Patient or population: adults with CRPS II Settings: any Intervention: multimodal physiotherapy Comparison: any eligible comparison | ||||

| Outcomes | Effect size (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Pain (VAS 0 to 100) | No data | — | — | — |

| Disability | No data | — | — | — |

| Incidence/nature of adverse effects | No data | — | — | — |

| CRPS II: complex regional pain syndrome type II | ||||

CI: confidence interval; CRPS: complex regional pain syndrome; VAS: visual analogue scale

Background

This is the first update of a review of physiotherapy interventions for complex regional pain syndrome originally published in 2016 (Smart 2016).

Description of the condition

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a persistent, painful and disabling condition that usually, but not exclusively, manifests in response to acute trauma or surgery (Goebel 2011; Shipton 2009). The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) introduced the diagnostic label 'CRPS' in the 1990s in order to standardise inconsistencies in terminology and diagnostic criteria (Merskey 1994). Two sub‐categories of CRPS have been described: CRPS type I (CRPS I) (formerly and variously referred to as reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD), algodystrophy, Sudek's atrophy), in which there is no clear evidence of a nerve lesion and CRPS type II (CRPS II) (formerly referred to as causalgia, algoneurodystrophy), in which a co‐existing nerve lesion (as determined by nerve conduction studies or surgical inspection, for example) is present (Coderre 2011; Todorova 2013).

CRPS is characterised by symptoms and signs typically confined to a body region or limb, but which may become more widespread (van Rijn 2011). The diagnostic criteria for CRPS originally proposed by Veldman et al (Veldman 1993) and subsequently by the IASP (Merskey 1994) have since been revised in response to their low specificity and potential to over‐diagnose cases of CRPS. The Budapest criteria proposed by Harden 2010 have enhanced diagnostic accuracy and are now widely accepted (Goebel 2011). The diagnosis of CRPS is clinical and the cardinal features include (Goebel 2011):

continuing pain disproportionate to any inciting event;

the presence of clusters of various symptoms and signs reflecting sensory (e.g. hyperaesthesia, allodynia), vasomotor (e.g. asymmetries of temperature or skin colour, or both), sudomotor (e.g. oedema or altered sweating or both), motor (e.g. reduced range of motion, tremor) or trophic (e.g. altered hair or nails, or both) disturbances; and

the absence of any other medical diagnosis that might better account for an individual's symptoms and signs.

However, a recent international survey of clinical practice found half of health professionals who provided clinical care to patients with CRPS had difficulty in recognising the symptoms of CRPS (Grieve 2019). Symptom profiles can vary between individuals with CRPS (Borchers 2014) and while statistically determined phenotypes (‘central’, ‘peripheral’ and ‘mixed’ phenotypes) have been suggested (Dimova 2020), their clinical significance is as yet unclear.

The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying CRPS are not fully understood (Harden 2010). Current understanding implicates multiple mechanisms including complex contributions from a maladaptive pro‐inflammatory response and a disturbance in sympathetically mediated vasomotor control, together with maladaptive peripheral and central neuronal plasticity (Birklein 2017; Bruehl 2010; Bruehl 2015; Knudsen 2019; Marinus 2011; Parkitny 2013). Furthermore, mechanisms, and in consequence symptoms and signs, may vary between individuals and within individuals over the time course of the disorder, thus heightening the complexity (Marinus 2011).

The incidence of CRPS is not accurately known but population estimates indicate an incidence of somewhere between five and 26 cases per 100,000 person‐years (Marinus 2011). A likely conservative 11‐year period prevalence rate for CRPS of 20.57 per 100,000 people has been reported (Sandroni 2003). CRPS is three to four times more likely to occur in women than in men, and although it may occur at any time throughout the lifespan, it tends to occur more frequently with increasing age (Shipton 2009). Genetic susceptibility may serve as an aetiological risk factor for the development of CRPS (de Rooij 2009). In individuals who develop CRPS after a fracture, intra‐articular fracture, fracture‐dislocation, pre‐existing rheumatoid arthritis, pre‐existing musculoskeletal co‐morbidities (e.g. low‐back pain, arthrosis) (Beerthuizen 2012) and limb immobilisation (Marinus 2011) may increase the risk of its development. A retrospective analysis of risk factors for the development of CRPS I in a large (22,533 patients) 'Nationwide Inpatient Sample' database from 2007 to 2011 in the United States found female gender, Caucasian race, higher median household income, depression, headache and drug abuse to be associated with a higher rate of CRPS I in an inpatient population (Elsharydah 2017). Others have found that psychological traits, such as depression, anxiety, neuroticism and anger, have so far been discounted as risk factors for the development of CRPS (Beerthuizen 2009: Lohnberg 2013), although further prospective studies are required to substantiate this assertion (Harden 2013). However, they may be associated with poorer outcomes once the condition has developed (Bean 2015). Studies into the course of CRPS present contradictory findings. Whilst some studies have reported complete and partial symptom resolution within one year (Sandroni 2003; Zyluk 1998), other studies have indicated more protracted symptoms and impairments lasting from three to nine years (de Mos 2009; Geertzen 1998; Vaneker 2006). Evidence from prognostic studies of CRPS is scarce and contradictory (Wertli 2013).

People with CRPS have been found to have poor knowledge of the condition (Brunner 2010), and experience significant suffering and disability (Bruehl 2010; Lohnberg 2013). It appears that men with CRPS are more likely to experience depression and kinesiophobia and use more passive coping strategies than women (van Velzen 2019). Preliminary data suggest that interference with activities of daily living, sleep, work and recreation is common and further contributes to a diminished quality of life (Galer 2000; Geertzen 1998; Kemler 2000; Sharma 2009). Qualitative data concerning the lived experience of CRPS from the patient's perspective is emerging. Such studies have found that living with CRPS is a daily battle, and that coping with changing symptoms together with the knowledge that there is no known cure can be particularly challenging (Johnston‐Devin 2018). Furthermore, living with CRPS can have a widespread impact on personal and social relationships and intimacy (Packham 2020). Another qualitative study that investigated the informational needs of people living with CRPS found patients wanted honest and accurate information, the opportunity to meet others with the condition and readily available resources with which to facilitate access to local expertise (Grieve 2016a).

Guidelines for the treatment of CRPS recommend an interdisciplinary multimodal approach, comprising pharmacological and interventional pain management strategies together with rehabilitation, psychological therapy and educational strategies (Goebel 2018; Harden 2013; Perez 2010; Stanton‐Hicks 2002), and two international surveys of clinical practice suggest such care is being delivered (Grieve 2019; Miller 2017). However determining the optimal approach to therapy remains clinically challenging (Cossins 2013; O'Connell 2013; Shim 2019).

Description of the intervention

Despite the fact that their effectiveness is not known, guidelines recommend the inclusion of a variety of physiotherapy interventions as part of the multimodal treatment of CRPS (Goebel 2018; Perez 2010; Stanton‐Hicks 2002). Physiotherapy has been defined as "the treatment of disorders with physical agents and methods" (Anderson 2002). For CRPS this could include any of the following interventions employed either as stand‐alone interventions or in combination: manual therapy (e.g. mobilisation, manipulation, massage, desensitisation); therapeutic exercise and progressive loading regimens (including hydrotherapy); electrotherapy (e.g. transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), therapeutic ultrasound, interferential, shortwave diathermy, laser); physiotherapist‐administered education (e.g. pain neuroscience education); as well as cortically directed sensory‐motor rehabilitation strategies (e.g. graded motor imagery (GMI), mirror therapy, sensory‐motor retuning, tactile discrimination training).

How the intervention might work

The precise mechanisms of action through which various physiotherapy interventions are purported to relieve the pain and disability associated with CRPS are not fully understood. Theories underpinning the use of manual therapies to relieve pain include the induction of peripheral or central nervous system‐mediated analgesia, or both (Bialosky 2018). While therapeutic exercise may bring about exercise‐induced analgesia by positively influencing i) central pain processing, via endorphin‐mediated inhibition for example (Nijs 2012), ii) immune system function and iii) the affective aspects of pain (Smith 2019), and improve function, and by extension disability, by restoring range of movement at affected joints and improving neuromuscular function and load tolerance (Kisner 2002). Theories underlying the use of electrotherapy modalities, also known as electrophysical agents, for pain relief variously include spinal cord‐mediated electro‐analgesia, heat‐ or cold‐mediated analgesia and anti‐inflammatory effects (Atamaz 2012; Logan 2017; Robertson 2006). Pain neuroscience education aims to reduce pain and disability by helping individuals to better understand the biological processes underlying their pain in a way that positively changes pain perceptions and attitudes (Moseley 2015). Other rehabilitation strategies, such GMI or mirror therapy, may provide pain relief or increase mobility, or both, by ameliorating maladaptive somatosensory and motor cortex reorganisation (Moseley 2012).

Why it is important to do this review

A number of systematic reviews suggest that physiotherapy interventions (e.g. exercise, GMI, TENS) employed in combination with medical management may be beneficial in reducing the pain and disability associated with CRPS (Daly 2009; Smith 2005). However, the inclusion of non‐randomised clinical trials and case series designs, together with the exclusion of studies involving people with CRPS II as well as those published in a language other than English, may have biased these conclusions. Given the limitations of existing systematic reviews, together with the availability of potentially numerous physiotherapy treatment strategies for CRPS, an up‐to‐date systematic review of the evidence from randomised clinical trials for the effectiveness of these interventions may assist clinicians in their treatment choices and inform future clinical guidelines that may be of use to policymakers and those who commission healthcare for people with CRPS.

Our original Cochrane systematic review of physiotherapy interventions for CRPS found very low‐quality evidence supporting the use of graded motor imagery and mirror therapy for pain and disability in people with CRPS I while evidence of the effectiveness of most other physiotherapeutic interventions was generally absent or unclear. Additionally, we found no eligible trials of physiotherapy interventions for CRPS II (Smart 2016). An update to our original Cochrane systematic review of physiotherapy interventions for CRPS was considered appropriate given the publication of a number of additional clinical trials since the endpoint of our original search (February 2015).

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions for treating pain and disability associated with CRPS types I and II.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (including those of parallel, cluster‐randomised and cross‐over design) published in any language. Translators identified by the Managing Editor of the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Group evaluated studies published in a language other than English. We excluded studies in which participants were not randomised to intervention groups.

While we accept that non‐randomised studies (e.g. case series, quasi‐experimental designs) can provide “proof of concept”‐level evidence for healthcare interventions it is our contention that such evidence should not be used to inform clinical treatment decision‐making because such evidence is less robust and subject to greater risks of bias than RCTs (Shea 2017). Also, given that our original systematic review identified 18 clinical trials we decided there was no justification for including non‐randomised studies on the grounds of an absence of RCT data upon which to inform clinical decision‐making. We accept it could be argued that the exclusion of non‐randomised studies provides an incomplete summary of the potential effects of interventions but we maintain the view that a robust systematic review of the evidence for the effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions for CRPS is best established by the inclusion of RCTs only. We remain open to the fact that developments in the science and methodology of systematic reviews might justify the inclusion of data from non‐randomised studies, such as from large population databases, in the future (Shea 2017). We included published abstracts and where there were insufficient data for analysis in the abstracts, we attempted to locate the full study (e.g. by contacting the study authors). If the data from the full study were unavailable, we added the abstract to ‘Studies awaiting classification’ (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table).

Types of participants

We included trials of adults, aged 18 years or older, diagnosed with CRPS I or II, or with an alternative diagnostic label for these conditions (e.g. RSD, causalgia). We grouped trials and analysed data according to diagnosis (i.e. CRPS I and II, or mixed). Since the use of formal diagnostic criteria for CRPS is inconsistent across studies (Reinders 2002), we included trials that used established or validated diagnostic criteria, including the Veldman criteria (Veldman 1993), the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) criteria (Merskey 1994), Bruehl criteria (Bruehl 1999), Budapest criteria (Harden 2010), and Atkins criteria (Atkins 2010), as well as studies that either predate these criteria or use non‐standard diagnostic criteria.

Types of interventions

We included all randomised controlled comparisons of physiotherapy interventions, employed in either a stand‐alone fashion or in combination, compared with placebo, no treatment, another intervention or usual care, or of varying physiotherapy interventions compared with each other, which were aimed at treating pain or disability, or both, associated with CRPS. We included trials in which non‐physiotherapists (e.g. occupational therapists) delivered such physiotherapy interventions, as defined in Description of the intervention, and reported the professional discipline of the clinician delivering the intervention. We did not pre‐define any specific comparisons in advance as physiotherapy interventions encompass a broad range of potential therapeutic approaches (e.g. various rehabilitation strategies or electrotherapy modalities). After the publication of our Cochrane protocol (Smart 2013), we decided to exclude studies that evaluated non‐physiotherapy based interventions (e.g. pharmacological) in which all arms received the same physiotherapy intervention (differing only in the application of the non‐physiotherapy component) as they are unlikely to offer any insight into the value of physiotherapy management (see Differences between protocol and review).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Pain intensity as measured using a visual analogue scale (VAS), numerical rating scale (NRS), verbal rating scale or Likert scale.

Disability as measured by validated self‐report questionnaires/scales or functional testing protocols.

Secondary outcomes

We planned to analyse the following secondary outcome measures where such data were available:

Composite scores for CRPS symptoms.

Health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) using any validated tool.

Patient global impression of change (PGIC) scales.

Incidence/nature of adverse effects (AEs).

We excluded studies that did not measure the primary or secondary outcomes of interest described above.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For this update we identified relevant RCTs by electronically searching the following databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library, Issue 7 of 12, 2021;

MEDLINE (OVID) (1966 to 16 July 2021);

EMBASE (OVID) (1974 to 16 July 2021);

CINAHL (EBSCO) (1982 to July 2021);

PsycINFO (OVID) (1806 to July 2021);

LILACS (Bireme) (1982 to July 2021);

PEDro (1929 to July 2021);

Web of Science (ISI) (1945 to July 2021).

The Information Specialist of the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Group devised the search strategies and added some extra terms to the strategies for this update. She and the review authors ran these searches. We used a combination of controlled vocabulary, i.e. medical subject headings (MeSH) and free‐text terms. The search strategies used for this update and the original review can be found in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

Reference lists

On completion of the electronic searches we searched the reference lists of all eligible studies in order to identify additional relevant studies. In addition we screened the reference lists of previous systematic reviews (Bowering 2013; Daly 2009; O'Connell 2013; Smith 2005).

External experts

We sent the list of included trials to a content expert to help identify any additional relevant studies (November 2020).

Unpublished data

In order to minimise the impact of publication bias we searched the following registers and databases to identify unpublished research as well as research in progress (July to August 2021):

OpenGrey (System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe);

ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (formerly Dissertation Abstracts (ProQuest));

National Research Register Archive;

Health Services Research Projects in Progress;

Current Controlled Trials Register (incorporating the meta‐register of controlled trials and the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number);

ClinicalTrials.gov;

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform;

Pan African Clinical Trials Registry;

EU Clinical Trials Register.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (KMS and BMW in the original review and KMS and MCF in this updated review) independently assessed the titles and abstracts of studies we identified by the search strategy for eligibility. If the eligibility of a trial was unclear from the title and abstract, we assessed the full‐text article. We obtained potentially relevant studies identified in the first round of screening in full text and independently assessed these for inclusion using the same process outlined above. We excluded trials that did not match the inclusion criteria (see the Criteria for considering studies for this review section). We resolved any disagreements between review authors regarding a study's inclusion by discussion. If we could not resolve disagreements, a third review author (NOC) assessed relevant studies and we made a majority decision. Trials were not anonymised prior to assessment. We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (KMS and BMW in the original review and KMS and MCF in this updated review) independently extracted data from all included trials. We extracted data using a standardised and piloted form. We resolved any discrepancies and disagreements by consensus. In cases where we could not achieve consensus, a third review author (NOC) assessed the trial and we took a majority decision. We extracted the following data from each included trial:

country of origin;

study design;

study population (including diagnosis, diagnostic criteria used, symptom duration, age range, gender split);

type of noxious initiating event: surgery, fracture, crush injury, projectile, stab injury, other or no event;

type of tissue injured: nerve, soft tissue, bone;

presence of medico‐legal factors (that may influence the experience of pain and the outcomes of therapeutic interventions);

concomitant treatments that may affect outcome: medication, procedures etc.;

sample size: active and control/comparator groups;

intervention (including type, parameters (e.g. frequency, dose, duration), setting and professional discipline of the clinician delivering the therapy);

type of placebo/comparator intervention;

outcomes (primary and secondary) and time points assessed;

adverse effects;

author conflict of interest statements and study funding source;

assessment of risk of bias.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the overall risk of bias for each included trial on the basis of an evaluation of key domains using a modified version of the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool. We classified risk of bias as either 'low' (low risk of bias for all key domains), 'unclear' (unclear risk of bias for one or more key domains) or 'high' (high risk of bias for one or more key domains) (items 1 to 8 and 11 below), as outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We also considered experimental design‐specific (e.g. cross‐over study designs) risk of bias issues where appropriate (Higgins 2011b). We also evaluated included trials for the additional sources of bias associated with sample size and duration of follow‐up, as recommended by Moore 2010 (items 9 and 10 below). Small studies are more prone to bias because of their inherent imprecision and due to the effects of publication biases (Dechartres 2013; Moore 2012; Nüesch 2010). Inadequate length of follow‐up may produce an overly positive view of the true clinical effectiveness of interventions, particularly in persistent conditions (Moore 2010). These additional criteria were not considered 'key domains' and therefore did not inform judgements of a trial's overall risk of bias. We assessed the following key and non‐key domains of risks of bias for each included trial using either 'low', 'unclear' or 'high' judgements according to the following criteria:

Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias). We assessed the method used to generate the allocation sequence as either: low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator); unclear risk of bias (method used to generate sequence not clearly stated); or high risk of bias (studies on closer inspection using a quasi/non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number).

Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias). The method used to conceal allocation to group prior to assignment determines whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment. We assessed the methods used as: low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes); unclear risk of bias (method not clearly stated); or high risk of bias (studies that do not adequately conceal allocation, e.g. open list).

Blinding of study participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias). We assessed the methods used to blind participants and care providers as either: low risk of bias (participants and care providers blinded to allocated intervention and unlikely that blinding broken; or no/incomplete blinding but judged that both intervention arms reflect active interventions of relatively equal credibility delivered with equal enthusiasm); unclear risk of bias (insufficient information provided to permit a judgement of low/high risk of bias); or high risk of bias (participants and care providers not blinded to the allocated intervention and interventions are clearly identifiable as control and experimental; or participants and care providers blinded to the allocated intervention but likely that blinding was broken).

Blinding of outcome assessment (self‐reported outcomes) (checking for possible detection bias). We assessed the methods used to blind study participants self‐reporting outcomes (e.g. pain severity) from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed the methods as either: low risk of bias (participants blinded to allocated intervention and unlikely that blinding broken; or no/incomplete blinding but judged that both intervention arms reflect active interventions of relatively equal credibility delivered with equal enthusiasm); unclear risk of bias (insufficient information provided to permit a judgement of low/high risk of bias); or high risk of bias (participants not blinded to the allocated intervention and interventions are clearly identifiable as control and experimental; or participants blinded to the allocated intervention but likely that blinding was broken).

Blinding of outcome assessment (investigator‐administered outcomes) (checking for possible detection bias). We assessed the methods used to blind researchers undertaking outcome assessments (e.g. functional testing protocols) from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed the methods as at either: low risk of bias (researchers blinded to allocated intervention and unlikely that blinding broken); unclear risk of bias (insufficient information provided to permit a judgement of low/high risk of bias); high risk of bias (researchers not blinded to the allocated intervention; or researcher blinded to the allocated intervention but likely that blinding was broken).

Incomplete outcome data (dropout) (checking for possible attrition bias). We first assessed for risk of attrition bias by evaluating participant dropout rates according to judgements based on the following criteria: low risk of bias (less than 20% dropout and appears not to be systematic, with numbers for each group and reasons for dropout reported); unclear risk of bias (less than 20% dropout but appears to be systematic or numbers per group and reasons for dropout not reported); high risk of bias (greater than or equal to 20% dropout).

Incomplete outcome data (method of analysis) (participants analysed in the group to which they were allocated) (checking for possible attrition bias). We further assessed for risk of attrition bias by separately evaluating the appropriateness of the method of analysis employed, using the following criteria: low risk of bias (participants analysed in the group to which they were allocated (intention‐to‐treat (ITT) or as an available case analysis); unclear risk of bias (insufficient information provided to determine if analysis was based on the principle of ITT or per protocol); or high risk of bias (if per protocol analysis used or where available data is not analysed or participant data were included in a group to which they were not originally assigned to).

Selective reporting (checking for possible reporting bias). We assessed studies for selective outcome reporting using the following judgements: low risk of bias (study protocol available and all pre‐specified primary outcomes of interest adequately reported or study protocol not available but all expected primary outcomes of interest adequately reported or all primary outcomes numerically reported with point estimates and measures of variance for all time points); unclear risk of bias (insufficient information provided to permit a judgement of low/high risk of bias); or high risk of bias (incomplete reporting of pre‐specified primary outcomes or point estimates and measures of variance for one or more primary outcome not reported numerically (e.g. graphically only) or one or more primary outcomes reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of data that were not pre‐specified or one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified or results for a primary outcome expected to have been reported were excluded).

Sample size (checking for possible biases confounded by small sample size): we assessed trials as being at low risk of bias (greater than or equal to 200 participants per treatment arm); unclear risk of bias (50 to 199 participants per treatment arm); high risk of bias (less than 50 participants per treatment arm).

Duration of follow‐up (checking for possible biases confounded by a short duration of follow‐up): we assessed trials as being at low risk of bias (follow‐up of greater than or equal to eight weeks); unclear risk of bias (follow‐up of two to seven weeks); or high risk of bias (follow‐up of less than two weeks).

Other bias. We assessed studies for other potential sources of bias. We determined judgements regarding low/unclear/high risk of bias according to the potential confounding influence of identified factors, for example: low risk of bias (appears free of other potentially serious sources of bias e.g. no serious study protocol violations identified); unclear risk of bias (other sources of bias may be present but there is either insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists or insufficient rationale or evidence regarding whether an identified problem will introduce bias); or high risk of bias (results may have been confounded by at least one potentially serious risk of bias, e.g. a significant baseline imbalance between groups; a serious protocol violation; use of 'last observation carried forward' when dealing with missing data).

Two review authors (KMS and BMW in the original review and KMS and MCF in this updated review) independently undertook the risk of bias assessments, and resolved any disagreements by discussion. If they could not reach an agreement, a third review author (NOC) undertook a risk of bias assessment and we took a majority decision.

Measures of treatment effect

We expressed the size of treatment effect on pain intensity, as measured with a VAS or NRS, using the mean difference (MD) (where all studies utilised the same measurement scale) or the standardised mean difference (SMD) (where studies used different scales) based on the approach described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011). Effect sizes were also expressed as a proportion of average baseline values. In order to aid interpretation of the pooled effect size we planned to back‐transform the SMD value to a 0 to 100 mm VAS format on the basis of the mean standard deviation (SD) from trials using a 0 to 100 mm VAS where possible.

We presented and analysed primary outcomes as change on a continuous scale or in a dichotomised format as the proportion of participants in each group who attained a predetermined threshold of improvement. For example, we judged cut‐points from which to interpret the likely clinical importance of (pooled) effect sizes according to provisional criteria proposed in the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) consensus statement (Dworkin 2008). Specifically, we judged reductions in pain intensity compared with baseline as follows:

less than 15%: 'no important change';

15% or more: 'minimally important change';

30% or more: 'moderately important change';

50% or more: 'substantially important change'.

We planned to use the cut‐points for 'minimally', 'moderately' and 'substantially’ important changes to generate dichotomous outcomes, the effect size for which we would have expressed as the risk ratio (or relative risk (RR)) but a lack of data did not permit any such analyses.

The IMMPACT thresholds are based on estimates of the degree of within‐person change from baseline that participants might consider clinically important. In a change to our original protocol (Smart 2013) and systematic review (Smart 2016), we extended our interpretation of changes in outcomes to include between‐group differences (see Differences between protocol and review). There is little consensus or evidence regarding cut‐points from which to interpret the magnitude of clinically important differences in pain intensity (or other patient‐related outcome measures) based on the between‐group difference post‐intervention (Dworkin 2009). For the purpose of this systematic review we adopted the recommendations of the OMERACT 12 group, with a threshold of 10 mm on a 0 mm to 100 mm VAS as being the threshold for minimal importance for average between‐group change (Busse 2015). Busse 2015 also suggests some more nuanced interpretations of between‐group changes, with pooled estimates of i) ≥ 2.0 units suggesting a large treatment effect, ii) 1.0 to 1.9 suggesting an important effect, iii) 0.5 to 1.0 suggesting the treatment may benefit an appreciable number of patients, and iv) ≤ 0.5 suggesting a small to very small effect. We interpreted our estimates of treatment effect according to these thresholds but did so appropriately and cautiously.

We planned to present secondary outcomes as change on a continuous scale or in a dichotomised format but a lack of data did not permit any such analyses.

We analysed the data using Review Manager (RevMan) (RevMan 2014). We plotted the results of each RCT with available data as point estimates with corresponding 95% CIs and displayed them using forest plots. If included trials demonstrated clinical homogeneity we performed a meta‐analysis to quantify the pooled treatment effect sizes using a random‐effects model. We did not perform a meta‐analysis when clinical heterogeneity was present. Similarly we presented secondary outcomes, though we did not consider them for meta‐analysis.

Unit of analysis issues

All included trials randomised participants at the individual participant level. We planned to meta‐analyse estimates of treatment effect (and their standard errors (SE)) from cluster‐RCTs employing appropriate statistical analyses using the generic inverse‐variance method in RevMan (RevMan 2014), as suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b). Where we considered such trials to have employed inappropriate analyses, we planned to utilise methods for 'approximately correct analysis' where possible (Higgins 2011b). In addition, we planned to enter cross‐over trials into a meta‐analysis when it was clear that data were free from carry‐over effects, and to combine the results of cross‐over trials with those of parallel trials by imputing the post‐treatment between‐condition correlation coefficient from an included trial that presented individual participant data and use this to calculate the SE of the SMD. These data may be entered into a meta‐analysis using the generic inverse‐variance method (Higgins 2011b).

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to contact the authors of included trials when numerical data were unreported or incomplete. If trial authors only presented data in graphical form, we did not attempt to extract the data from the figures. If SD values were missing from follow‐up assessments but were available at baseline, we used these values as estimates of variance in the follow‐up analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We evaluated the included trials for clinical homogeneity regarding study population, treatment procedure, control intervention, timing of follow‐up and outcome measurement. For trials that were sufficiently clinically homogenous to pool, we formally explored heterogeneity using the Chi² test to investigate the statistical significance of any heterogeneity, and the I² statistic to estimate the amount of heterogeneity. We interpreted I2 values according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011):

0% to 40%: heterogeneity might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to test for the possible influence of publication bias on trials that utilised dichotomised outcomes by estimating the number of participants in trials with zero effect required to change the number needed to treat (NNT) to an unacceptably high level (defined as an NNT of 10), as outlined by Moore 2008. An absence of relevant data meant that we did not undertake any analyses. Instead, we considered the possible influence of small study/publication biases on review findings as part of our risk of bias assessment (see the Assessment of risk of bias in included studies section) and as part of our Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) assessments of the certainty of evidence (see the Data synthesis section) (Guyatt 2011a). We may include such analyses in future updates of this Cochrane Review where relevant data are available.

Data synthesis

Where possible, we grouped extracted data according to diagnosis (CRPS types I or II, or mixed), intervention, outcome (i.e. pain, disability) and duration of follow‐up (short‐term: zero to less than two weeks post intervention; mid‐term: two to seven weeks post intervention; and long‐term: eight or more weeks post intervention). Regarding intervention, we planned to pool data from trials that investigated the same single therapy separately for each therapy. We planned to pool trials of multimodal physiotherapy programmes together.

For all analyses, we report the outcome of the risk of bias assessments. Where we found inadequate data to support statistical pooling, we performed a narrative synthesis of the evidence.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where significant heterogeneity (P value < 0.1) was present, we planned to explore subgroup analyses (see the Differences between protocol and review section). We planned to perform subgroup analyses based on the type of CRPS (i.e. I, II or mixed) and its temporal characteristics (i.e. acute (defined as symptoms and signs of CRPS of zero to 12 weeks duration) and chronic (symptoms and signs of CRPS lasting 13 weeks)). However, we did not undertake them due to the insufficient number of included trials.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct a sensitivity analysis based on risk of bias (investigating the influence of excluding studies classified at high risk of bias).

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We conducted a qualitative analysis of all trial findings and used the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach to assess and rank the certainty of evidence (Guyatt 2011a; Guyatt 2011b).

To ensure consistency of GRADE judgements we applied the following assessment criteria:

Serious study limitations: we downgraded once if more than 25% of the participants were from trials we classified as being at overall high risk of bias, as described in the Assessment of risk of bias in included studies section.

Inconsistency: we downgraded once if heterogeneity was statistically significant and the I² statistic value was greater than 40%. When a meta‐analysis was not performed we downgraded once if the trials did not show effects in the same direction.

Indirectness: we downgraded once if more than 50% of the participants were outside the target group.

Imprecision: we downgraded once if there were fewer than 400 participants for continuous data and fewer than 300 events for dichotomous data.

Publication bias: we downgraded once where there was direct evidence of publication bias or if estimates of effect based on small‐scale, industry‐sponsored studies raised a high index of suspicion of publication bias.

Two review authors (KMS and MCF) made the judgement of whether these factors were present or not. We considered single trials to be inconsistent and imprecise, unless more than 400 participants were randomised for continuous outcomes or more than 300 for dichotomous outcomes. We applied the following definitions regarding the certainty of the evidence (Balshem 2011):

High: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Summary of findings table

At the time of protocol development we did not specify any key comparisons of interventions (Smart 2013). In light of the wide range of trial interventions identified and the very limited data available we have taken the post hoc decision to present summary of findings tables for our primary outcomes of pain and disability, together with adverse effects, for the comparisons 'Physiotherapy compared to minimal care for adults with CRPS I and CRPS II' and included trials that delivered what we determined to be conventional multimodal physiotherapy, reflective of common clinical practice (Miller 2019).

We have not presented summary of findings tables for all identified comparisons of interventions as these are, we judge, too numerous, most often involving single trials with small samples and minimal to no data presented, and therefore of limited clinical use. However, we have considered the findings from all included trials with respect to all our outcomes of interest in full in the Effects of interventions section.

Results

Description of studies

See the Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

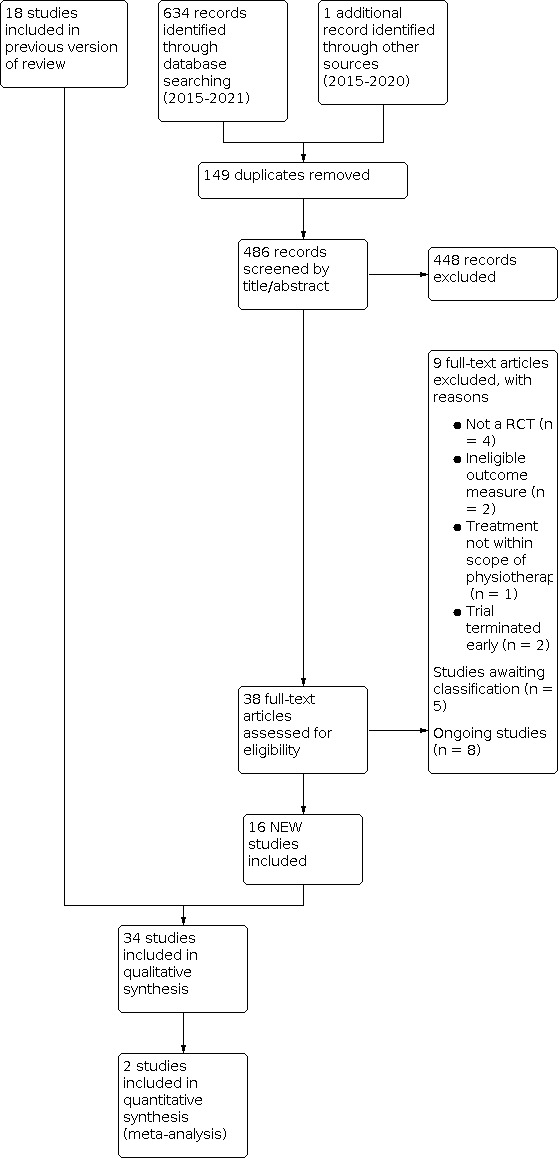

Our updated search period extended from February 2015, the time point up to which our original search was conducted, to July 2021. We identified 634 records from the database searches and one additional record from an author whom we contacted with a query. After de‐duplication (n = 149) we screened 486 abstracts from which we assessed 38 full‐text articles for eligibility. A total of 16 studies met our inclusion criteria (see Characteristics of included studies table). We have presented a flow diagram outlining the trial screening and selection process (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

We combined the 16 trials (600 participants) identified in our updated literature search with the 18 trials (739 participants) included within our original review (Smart 2016). From the combined total of 1230 records screened and 80 full‐text reviews across the two searches, we included 34 trials involving 1339 participants in this review.

Included studies

We included 34 trials in this review, 18 from the original review (Smart 2016) (Askin 2014; Aydemir 2006; Cacchio 2009a; Cacchio 2009b; Dimitrijevic 2014; Duman 2009; Durmus 2004; Hazneci 2005; Jeon 2014; Li 2012; Moseley 2004; Moseley 2005; Moseley 2006; Moseley 2009; Mucha 1992; Oerlemans 1999; Schreuders 2014; Uher 2000), and 16 from the updated searches (Barnhoorn 2015; Benedetti 2018; Bilgili 2016; Bϋyϋkturan 2018; den Hollander 2016; Devrimsel 2015; Halicka 2021; Hwang 2014; Lewis 2021; Ozcan 2019; Ryan 2017; Saha 2021; Sarkar 2017; Strauss 2021; Topcuoglu 2015; Vural 2016). We have provided the details of all included trials in the Characteristics of included studies table.

In our original review we contacted 10 authors for missing data (Cacchio 2009b; Jeon 2014; Moseley 2004; Moseley 2005; Moseley 2006; Moseley 2009; Mucha 1992; Oerlemans 1999; Schreuders 2014; Uher 2000). One trial author responded and supplied data for an outcome measure of 'impairment' but we were unable to extract outcome data linked to 'pain intensity' from the supplied data (Oerlemans 1999). One trial author responded, stating that they were unable to supply the relevant data (Schreuders 2014). There was no response from the other trial authors we had contacted. In this updated review, we contacted 10 authors for missing data (den Hollander 2016; Halicka 2021; Hwang 2014; Lewis 2021; Ozcan 2019; Ryan 2017; Sarkar 2017; Strauss 2021; Topcuoglu 2015; Vural 2016). Five authors supplied missing data (den Hollander 2016; Halicka 2021; Ryan 2017; Sarkar 2017; Strauss 2021). One author replied to report that they did not have the data (Vural 2016). One author replied indicating that they would look into our request but did not subsequently supply the data (Ozcan 2019). There was no response from the remaining three authors (Hwang 2014; Lewis 2021; Topcuoglu 2015).

Design

All included trials were RCTs, and 32 essentially used a parallel‐group design. Whilst the selected participants in three trials crossed over from comparator to intervention groups (Cacchio 2009b; Moseley 2004; Mucha 1992), none employed a true randomised cross‐over design and we analysed them up to the point of cross‐over as parallel‐group designs. Two trials employed a within‐subject randomised cross‐over design (Moseley 2009; Strauss 2021). The majority of included trials (26 out of 34) included two intervention arms, seven trials included three arms (Askin 2014; Aydemir 2006; Cacchio 2009b; Hwang 2014; Moseley 2005; Oerlemans 1999; Sarkar 2017), and one study used four arms (Moseley 2009). No cluster‐RCTs met the inclusion criteria of this Cochrane Review.

Setting

Trials were undertaken across a range of geographical locations including: Turkey (n = 11); Australia and the Netherlands (n = 4 each); Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom (n = 3 each), India and South Korea (n = 2 each); China, India and Serbia (n = 1 each). Three (9%) were multi‐centre trials (Halicka 2021; Lewis 2021; Oerlemans 1999), nine (28%) trials did not report whether they were single‐ or multi‐centre (Cacchio 2009b; Devrimsel 2015; Duman 2009; Moseley 2005; Moseley 2006; Moseley 2009; Mucha 1992; Schreuders 2014; Uher 2000), and the remaining 22 (65%) were all single‐centre trials.

Participants

The 34 trials included a total of 1339 participants and the total number of participants per trial ranged from eight (Ryan 2017) to 135 (Oerlemans 1999). Thirty trials included participants with CRPS I using a range of diagnostic criteria, most commonly using those of Bruehl 1999 and Harden 2007; Harden 2010. One trial included participants with CRPS II (Strauss 2021) and one trial included participants with CRPS type I and II but did not report the numbers with each type (Hwang 2014). Two trials did not specify the type of CRPS for their participants (Lewis 2021; Sarkar 2017).

Twenty‐four trials included participants with CRPS I of the upper limb (Askin 2014; Aydemir 2006; Bilgili 2016; Bϋyϋkturan 2018; Cacchio 2009a; Cacchio 2009b; Devrimsel 2015; Duman 2009; Durmus 2004; Halicka 2021; Hazneci 2005; Lewis 2021; Li 2012; Moseley 2004; Moseley 2005; Moseley 2009; Mucha 1992; Oerlemans 1999; Ozcan 2019; Ryan 2017; Saha 2021; Schreuders 2014; Topcuoglu 2015; Vural 2016), seven with either upper or lower limb CRPS I (Barnhoorn 2015; Benedetti 2018; den Hollander 2016; Dimitrijevic 2014; Hwang 2014; Moseley 2006; Sarkar 2017), one with CRPS I of the lower limb (Uher 2000) and one trial included participants with either upper, lower, multi‐limb or whole body CRPS I (Jeon 2014). In the trials where the type of CRPS was not specified, one study included participants with upper limb CRPS (Lewis 2021) and one included participants with upper and lower limb CRPS (Sarkar 2017). Participants developed CRPS I linked to a range of aetiologies including onset post fracture, soft‐tissue injuries, stroke, surgery, carpal tunnel syndrome as well as of idiopathic onset.

Participants had acute symptoms (less than or equal to three months) of CRPS I in eight trials (Bϋyϋkturan 2018; Cacchio 2009a; Devrimsel 2015; Dimitrijevic 2014; Durmus 2004; Hazneci 2005; Li 2012; Mucha 1992), chronic symptoms (greater than three months) in 14 trials (Barnhoorn 2015; den Hollander 2016; Duman 2009; Halicka 2021; Hwang 2014; Jeon 2014; Lewis 2021; Moseley 2004; Moseley 2005; Moseley 2006; Moseley 2009; Ryan 2017; Saha 2021; Schreuders 2014), and a mix of acute and chronic symptoms in six trials (Askin 2014; Benedetti 2018; Oerlemans 1999; Sarkar 2017; Topcuoglu 2015; Vural 2016). Five trials involving participants with CRPS I did not report the duration of symptoms (Aydemir 2006; Bilgili 2016; Cacchio 2009b; Ozcan 2019; Uher 2000). Participants had chronic symptoms in the one trial involving those with CRPS II (Strauss 2021).

Interventions and comparators

We have provided a detailed description of the interventions delivered in each included trial in the Characteristics of included studies table. The types of physiotherapy interventions delivered were heterogeneous across the included trials and included various electro‐physical modalities (ultrasound, TENS, laser, interferential therapy, pulsed electromagnetic field therapy, whirlpool baths, neuromuscular electrical stimulation, fluidotherapy, contrast baths), cortically‐directed sensory‐motor rehabilitation strategies (GMI, mirror therapy, virtual body swapping, tactile sensory discrimination training, prism adaptation treatment), exercise (active, active‐assisted, passive, stretching, strengthening, mobilising, functional; supervised and unsupervised), cognitive‐behavioural interventions ('exposure‐based' strategies), manual lymphatic drainage (MLD) and pain management advice. Twelve trials evaluated electro‐physical modalities (Askin 2014; Aydemir 2006; Benedetti 2018; Bilgili 2016; Bϋyϋkturan 2018; Devrimsel 2015; Dimitrijevic 2014; Durmus 2004; Hazneci 2005; Mucha 1992; Ozcan 2019; Ryan 2017), 15 trials evaluated cortically‐directed sensory‐motor rehabilitation strategies (Cacchio 2009a; Cacchio 2009b; Halicka 2021; Hwang 2014; Jeon 2014; Lewis 2021; Moseley 2004; Moseley 2005; Moseley 2006; Moseley 2009; Saha 2021; Sarkar 2017; Schreuders 2014; Strauss 2021; Vural 2016), three trials evaluated aerobic exercise or general rehabilitation therapies (Li 2012; Oerlemans 1999; Topcuoglu 2015), two trials evaluated MLD (Duman 2009; Uher 2000) and two trials evaluated cognitive‐behavioural/exposure‐based interventions (Barnhoorn 2015; den Hollander 2016). Eleven trials directly compared an active and placebo intervention (Askin 2014; Aydemir 2006; Benedetti 2018; Bilgili 2016; Bϋyϋkturan 2018; Cacchio 2009a; Cacchio 2009b; Durmus 2004; Halicka 2021; Lewis 2021; Ryan 2017), and 22 trials compared the experimental intervention to an active comparator. Of these, 11 trials compared the experimental intervention to 'conventional treatment' (Barnhoorn 2015; den Hollander 2016; Duman 2009; Li 2012; Moseley 2004; Moseley 2006; Ozcan 2019; Saha 2021; Schreuders 2014; Topcuoglu 2015; Vural 2016), and 11 trials compared the experimental intervention to various other active comparators (Devrimsel 2015; Dimitrijevic 2014; Hazneci 2005; Hwang 2014; Jeon 2014; Moseley 2005; Moseley 2009; Mucha 1992; Oerlemans 1999; Sarkar 2017; Uher 2000). One cross‐over trial compared the experimental intervention to a waiting list control (Strauss 2021).

Excluded studies

We excluded nine full‐text trial reports from the updated searches, in addition to the 13 excluded from the original review, because they were not RCTs (n = 4), investigated outcome measures that were not of interest (n = 2), were terminated early (n = 2) or tested interventions that fell outside the scope of physiotherapy (n = 1) (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Studies awaiting classification

Eight trials are awaiting classification (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). At the time the searches for the current review update were undertaken (July 2021) four trials had only been published as conference abstracts (Dimitrijevic 2019; Dimitrijevic 2020; Mallikarjunaiah 2015; Patru 2017). We were unable to make contact with the authors of three trials to ascertain their status (ISRCTN39729827; ISRCTN97144266; NCT01944150) and one trial had been delayed (UKCRN ID 12602).

Ongoing studies

We identified seven potentially relevant ongoing studies that are either completed and being analysed (NCT03377504; NCT03887962), ongoing (NCT02395211; NCT02753335), delayed (JPRN‐UMIN000029801), or whose progress is unknown (ChiCTR1900020835; CTRI/2019/01/017272) (see Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

We have summarised risk of bias results for all included trials in Figure 2 and Figure 3. We judged the overall risk of bias, based on evaluations of key domains (i.e. random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of study participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other bias) as being 'high' for 27 trials (Askin 2014; Barnhoorn 2015; Bilgili 2016; Bϋyϋkturan 2018; Cacchio 2009b; den Hollander 2016; Dimitrijevic 2014; Duman 2009; Halicka 2021; Jeon 2014; Lewis 2021; Li 2012; Moseley 2004; Moseley 2005; Moseley 2006; Moseley 2009; Mucha 1992; Oerlemans 1999; Ozcan 2019; Ryan 2017; Saha 2021; Sarkar 2017; Schreuders 2014; Strauss 2021; Topcuoglu 2015; Uher 2000; Vural 2016), and 'unclear' for seven trials (Aydemir 2006; Benedetti 2018; Cacchio 2009a; Devrimsel 2015; Durmus 2004; Hazneci 2005; Hwang 2014). We did not judge any of the included trials as having an overall 'low' risk of bias.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included trials.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included trial.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

We judged 18 trials to be at low risk of bias as the methods used to generate the random sequence were adequately described (Aydemir 2006; Barnhoorn 2015; Benedetti 2018; den Hollander 2016; Dimitrijevic 2014; Durmus 2004; Halicka 2021; Lewis 2021; Li 2012; Moseley 2004; Moseley 2005; Moseley 2006; Oerlemans 1999; Ozcan 2019; Ryan 2017; Schreuders 2014; Topcuoglu 2015; Vural 2016), and 12 to be at unclear risk of bias because insufficient information was provided on the process for random sequence generation (Cacchio 2009a; Cacchio 2009b; Devrimsel 2015; Duman 2009; Hazneci 2005; Hwang 2014; Jeon 2014; Moseley 2009; Mucha 1992; Saha 2021; Strauss 2021; Uher 2000). Four trials used a quasi‐randomisation method and we judged these to be at high risk of bias (Askin 2014; Bilgili 2016; Bϋyϋkturan 2018; Sarkar 2017).

Allocation concealment

We judged 10 trials to be at low risk of bias because the methods for concealing allocation were adequately described (Barnhoorn 2015; den Hollander 2016; Dimitrijevic 2014; Lewis 2021; Li 2012; Moseley 2009; Ryan 2017; Saha 2021; Schreuders 2014; Uher 2000), and 24 to be at unclear risk of bias because insufficient information was provided about how allocation was concealed (Askin 2014; Aydemir 2006; Benedetti 2018; Bilgili 2016; Bϋyϋkturan 2018; Cacchio 2009a; Cacchio 2009b; Devrimsel 2015; Duman 2009; Durmus 2004; Halicka 2021; Hazneci 2005; Hwang 2014; Jeon 2014; Moseley 2004; Moseley 2005; Moseley 2006; Mucha 1992; Oerlemans 1999; Ozcan 2019; Sarkar 2017; Strauss 2021; Topcuoglu 2015; Vural 2016).

Blinding

Blinding of study participants and personnel

We judged 10 trials to be at low risk of bias where participants and personnel were adequately blinded to the intervention or where we considered a lack of blinding to have been unlikely to have biased trial outcomes (Askin 2014; Aydemir 2006; Benedetti 2018; Devrimsel 2015; Dimitrijevic 2014; Durmus 2004; Halicka 2021; Hazneci 2005; Lewis 2021; Moseley 2005), and five to be at unclear risk of bias where there was insufficient information provided to permit a judgement of low/high risk of bias (Bϋyϋkturan 2018; den Hollander 2016; Hwang 2014; Jeon 2014; Moseley 2009). We judged 19 trials to have a high risk of bias because of inadequate or a lack of blinding (Barnhoorn 2015; Bilgili 2016; Cacchio 2009a; Cacchio 2009b; Duman 2009; Li 2012; Moseley 2004; Moseley 2006; Mucha 1992; Oerlemans 1999; Ozcan 2019; Ryan 2017; Saha 2021; Sarkar 2017; Schreuders 2014; Strauss 2021; Topcuoglu 2015; Uher 2000; Vural 2016).

Blinding of outcome assessment (self‐reported outcomes)

We judged 12 trials to be at low risk of bias because they successfully blinded participants who self‐reported outcomes (Askin 2014; Aydemir 2006; Benedetti 2018; Bϋyϋkturan 2018; den Hollander 2016; Devrimsel 2015; Dimitrijevic 2014; Durmus 2004; Halicka 2021; Hazneci 2005; Lewis 2021; Moseley 2005), and three to be at unclear risk of bias where there was insufficient information provided to permit a judgement of low/high risk of bias (Hwang 2014; Jeon 2014; Moseley 2009). We judged 19 trials to have a high risk of bias because of inadequate or a lack of blinding of participants who self‐reported outcomes (Barnhoorn 2015; Bilgili 2016; Cacchio 2009a; Cacchio 2009b; Duman 2009; Li 2012; Moseley 2004; Moseley 2006; Mucha 1992; Oerlemans 1999; Ozcan 2019; Ryan 2017; Saha 2021; Sarkar 2017; Schreuders 2014; Strauss 2021; Topcuoglu 2015; Uher 2000; Vural 2016).

Blinding of outcome assessment (investigator‐administered outcomes)

We judged 20 trials to be at low risk of bias either because they successfully blinded outcome assessors or where the trialists did not employ any investigator‐administered outcomes (Askin 2014; Aydemir 2006; Barnhoorn 2015; Benedetti 2018; Cacchio 2009a; Cacchio 2009b; den Hollander 2016; Durmus 2004; Halicka 2021; Hwang 2014; Jeon 2014; Lewis 2021; Moseley 2004; Moseley 2006; Ozcan 2019; Ryan 2017; Sarkar 2017; Schreuders 2014; Uher 2000; Vural 2016). We judged 13 trials to be at unclear risk of bias where there was insufficient information provided to permit a judgement of low/high risk of bias (Bilgili 2016; Bϋyϋkturan 2018; Devrimsel 2015; Dimitrijevic 2014; Duman 2009; Hazneci 2005; Li 2012; Moseley 2005; Moseley 2009; Mucha 1992; Oerlemans 1999; Strauss 2021; Topcuoglu 2015). We judged one trial to have a high risk of bias because of a lack of blinding of investigator‐administered outcomes (Saha 2021).

Incomplete outcome data (dropout)

Eighteen trials either had no dropouts or a dropout rate of less than 20% and as such we judged them as having a low risk of attrition bias secondary to dropouts (Askin 2014; Barnhoorn 2015; Benedetti 2018; Bϋyϋkturan 2018; Cacchio 2009b; Duman 2009; Durmus 2004; Jeon 2014; Li 2012; Moseley 2004; Moseley 2005; Moseley 2006; Moseley 2009; Mucha 1992; Ozcan 2019; Topcuoglu 2015; Uher 2000; Vural 2016). In 11 trials the risk of attrition bias was unclear either because the dropout rate was not reported (Aydemir 2006; Bilgili 2016; Devrimsel 2015; Hazneci 2005; Hwang 2014; Sarkar 2017), or the dropout rate between groups was unequal or the reasons for dropouts were only partially explained and we were unsure of the impact on the trial's results (Cacchio 2009a; Dimitrijevic 2014; Lewis 2021; Oerlemans 1999; Strauss 2021). Five trials with overall dropout rates of ≥ 20% had a high risk of attrition bias (den Hollander 2016; Halicka 2021; Ryan 2017; Saha 2021; Schreuders 2014).

Incomplete outcome data (participants analysed in the group to which they were allocated)

We judged 13 trials (Barnhoorn 2015; Cacchio 2009a; Cacchio 2009b; den Hollander 2016; Duman 2009; Durmus 2004; Jeon 2014; Li 2012; Moseley 2004; Moseley 2006; Moseley 2009; Mucha 1992; Oerlemans 1999), 11 trials (Aydemir 2006; Benedetti 2018; Bilgili 2016; Bϋyϋkturan 2018; Devrimsel 2015; Hazneci 2005; Hwang 2014; Lewis 2021; Sarkar 2017; Topcuoglu 2015; Vural 2016), and 10 trials (Askin 2014; Dimitrijevic 2014; Halicka 2021; Moseley 2005; Ozcan 2019; Ryan 2017; Saha 2021; Schreuders 2014; Strauss 2021; Uher 2000), respectively as being at 'low', 'unclear' and 'high' risk of attrition bias as a consequence of their adopted method of analysis.

Selective reporting

Seventeen trials either adequately reported outcome data (Askin 2014; Aydemir 2006; Benedetti 2018; Bilgili 2016; Bϋyϋkturan 2018; Cacchio 2009a; Devrimsel 2015; Dimitrijevic 2014; Duman 2009; Hazneci 2005; Li 2012; Moseley 2006; Saha 2021), or the authors supplied missing data (Halicka 2021; Ryan 2017; Sarkar 2017; Strauss 2021), and we judged them as being at low risk of reporting bias. We judged reporting bias to be unclear in one trial (Barnhoorn 2015). We judged a total of 16 trials as being at high risk of reporting bias; nine trials because of inadequate or incomplete reporting of primary outcomes, or both (den Hollander 2016; Durmus 2004; Hwang 2014; Jeon 2014; Oerlemans 1999; Ozcan 2019; Topcuoglu 2015; Uher 2000; Vural 2016), and seven trials because the trial authors presented data in graphical format only, i.e. point estimates with measures of variance were not reported (Cacchio 2009b; Lewis 2021; Moseley 2004; Moseley 2005; Moseley 2009; Mucha 1992; Schreuders 2014).

Sample size

None of the included trials had intervention arms with 200 or more participants per treatment arm. One trial randomised 60 participants to each trial arm and we judged it as being at unclear risk of bias (Li 2012). The remaining 33 trials had fewer than 50 participants per trial arm and we judged them as being at high risk of bias.

Duration of follow‐up

Ten trials employed a follow‐up period of eight or more weeks and we judged them as being at low risk of bias (Barnhoorn 2015; Cacchio 2009a; den Hollander 2016; Duman 2009; Halicka 2021; Li 2012; Moseley 2005; Moseley 2006; Oerlemans 1999; Ryan 2017). Five trials reported a follow‐up period of two to seven weeks (Aydemir 2006; Benedetti 2018; Moseley 2004; Saha 2021; Schreuders 2014), and we judged these as being at unclear risk of bias. Nineteen trials employed a follow‐up period of less than two weeks and we judged them as being at high risk of bias based on this criterion (Askin 2014; Bilgili 2016; Bϋyϋkturan 2018; Cacchio 2009b; Devrimsel 2015; Dimitrijevic 2014; Durmus 2004; Hazneci 2005; Hwang 2014; Jeon 2014; Lewis 2021; Moseley 2009; Mucha 1992; Ozcan 2019; Sarkar 2017; Strauss 2021; Topcuoglu 2015; Uher 2000; Vural 2016).

Other potential sources of bias

We considered four trials to be at high risk of other potential sources of bias: one trial because of differences in descriptions of the trial design and specification of a primary outcome measure between the trial registration and the published trial report (Strauss 2021); one trial because of imbalanced numbers of participants in an already very small group (n = 8) and differences in engagement with a co‐intervention between groups (Ryan 2017); one trial because it did not report the baseline data of three participants excluded from the analysis and because of a likely highly significant baseline imbalance in duration of symptoms between groups (Schreuders 2014); and one trial because violations of the random sequence generation were permitted (Oerlemans 1999). We judged six trials to be at unclear risk of bias: one trial because 27% of patients switched between intervention arms (Barnhoorn 2015); one trial because it was published as a 'Letter to the Editor' and not as a full trial report (Cacchio 2009b); one trial because of baseline imbalances between groups with respect to gender and duration of pain (Hwang 2014); one trial because it did not report participants' baseline pain data (Jeon 2014); one trial because of uncertainty regarding the extent to which a carry‐over effect may have introduced bias in estimates of treatment effect (Moseley 2009); and one because it did not report participants' baseline demographics and characteristics (Sarkar 2017). The 23 other trials appeared to be free of other potential sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1 (Physiotherapy compared with minimal care for adults with CRPS I); Table 2 (Physiotherapy compared with minimal care for adults with CRPS II).

Physiotherapy versus occupational therapy or minimal care for CRPS I

One three‐arm trial with 135 participants, which we judged as being at 'high' risk of bias based on a number of criteria, compared a physiotherapy programme (pain management advice, relaxation exercises, connective tissue massage, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and exercise) plus medical treatment according to a fixed pre‐established protocol, to an occupational therapy programme (splinting, de‐sensitisation, functional rehabilitation) plus medical management and to, what we understand is, an attention control intervention, described as 'social work' (SW) (which included attention, advice) plus medical management in participants with CRPS I of the upper limb secondary to mixed aetiologies (Oerlemans 1999). The trial authors did not adequately report details regarding the nature of the interventions and did not standardise the number of treatment sessions given with the intensity and frequency of treatment adjusted to the individual needs of participants. The trial authors did not report the overall duration of the treatment periods for each trial group.

Physiotherapy versus occupational therapy

Pain

Numerical data (i.e. group means and standard deviations (SD) for each time point) for the four self‐reported measures of pain intensity (current pain, pain from effort of use of the affected extremity, least and worst pain experienced in the preceding week) were not reported and the trial authors have not provided these data. Consequently, no further analyses of these measures were possible and we could not determine effect sizes. However, according to the trial report there were no between‐group differences in pain at 12‐month follow‐up (very low‐certainty evidence).

Disability

Numerical data for measures of upper limb disability (Impairment Level Sum score, Radboud Skills Questionnaire, modified Greentest, Radboud Dexterity Test) were not reported and the trial authors have not provided these data. Consequently, no further analyses of these measures were possible and we could not determine effect sizes. However, according to the trial report there were no between‐group differences in disability at 12‐month follow‐up (very low‐certainty evidence).

Other outcomes

The trial authors did not report numerical data from other outcomes of interest, including measures of health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) (Sickness Impact Profile) and adverse effects although the authors state that there were no between‐group differences in well‐being at 12 months follow‐up (Oerlemans 1999) (very low‐certainty evidence).

Certainty of the evidence

We judged the certainty of evidence for outcomes of pain and disability to be very low. We downgraded each three times, once for serious study limitations, once for inconsistency and once for imprecision. Consequently, we are uncertain whether a multimodal physiotherapy intervention improves disability or pain compared to an occupational therapy intervention in the treatment of CRPS I of the upper limb.

Physiotherapy versus minimal care

Pain

According to the trial authors (Oerlemans 1999), physiotherapy was superior to minimal care for reducing pain according to all four measures of pain intensity (current pain, pain from effort of use of the affected extremity, least and worst pain experienced in the preceding week) at three months post‐recruitment, and for reducing pain from effort of use of the affected extremity at six months. However, there were no between‐group differences for any measure of pain intensity at 12 months follow‐up. Numerical data (i.e. group means and standard deviations (SD) for each time point) for the four self‐reported measures of pain intensity were not reported, and the trial authors did not provide these data. Consequently, no further analyses of these measures were possible and we could not determine effect sizes (very low‐certainty evidence).

Disability