Abstract

Calcium-dependent, neuronal adenylyl cyclase subtype 1 (AC1) is critical for cortical potentiation and chronic pain. NB001 is a first-in-class drug acting as a selective inhibitor against AC1. The present study delineated the pharmacokinetic (PK) properties of human-used NB001 (hNB001) formulated as immediate-release tablet. This first-in-human (FIH) study was designed as randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. hNB001 showed placebo-like safety and good tolerability in healthy volunteers. A linear dose-exposure relationship was demonstrated at doses between 20 mg and 400 mg. The relatively small systemic exposure of hNB001 in human showed low bioavailability of this compound through oral administration, which can be improved through future dosage research. Food intake had minimal impact on the absorption of hNB001 tablet. Animal experiments further confirmed that hNB001 had strong analgesic effect in animal models of neuropathic pain. In brain slice prepared from the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), bath application of hNB001 blocked the induction of long-term potentiation (LTP). These results from both rodents and human strongly suggest that hNB001 can be safely used for the future treatment of different types of chronic pain in human patients.

Keywords: NB001, anterior cingulate cortex, pharmacokinetics, safety, tolerability, effectiveness, first-in-human study

Introduction

Chronic pain is mainly treated with drugs. Currently recommended pharmacotherapies include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids. The former drug class only works in patients with mild-to-moderate pain and use of these drugs are sometimes limited by the appearance of gastrointestinal adverse reactions.1,2 The latter drugs have stronger analgesic effects, but they are associated with adverse reactions involving the central nervous system (CNS) and gastrointestinal mobility. Moreover, gradual development of drug dependence, as well as issues of addiction and abuse are frequently seen during long-term administration of opioids. 3 Taken together, there are still great unmet needs in medical management of chronic pain.

Neurons in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) have been shown to play an important role in the perception of nociceptive signals.4–7 Adenylate cyclase 1 (AC1) is selectively expressed in the CNS, particularly in cortical areas that are important for pain perception such as the ACC and insular cortex (IC).8–11 Cumulative studies have demonstrated AC1 to be a promising therapeutic target for neuropathic and inflammatory pain, cancer pain, chronic visceral pain, and deep muscle pain.5,10–16 NB001 is a selective inhibitor of AC1, which has an estimated 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 10 μM on HEK293 cells expressing AC1. The effects of NB001 in previous formulation on pain sensitization were also investigated in vivo in tumor prone C3H/HeJ mice and SD rats. Compared to saline solution, NB001 significantly inhibited spontaneous and mechanical hyperalgesia in mice at intraperitoneal dose of 30 mg/kg and in rats at intragastric doses of 10 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg. 13 In SD rats with cancerous pain model, NB001 gavage (20 mg/kg) significantly increased paw withdrawal latency (PWL) and paw withdrawal threshold (PWT), the effects of which were comparable to those of morphine (2 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection) and gabapentin (100 mg/kg, gavage) (unpublished data). In a thermal hyperalgesia experiment, the analgesic effect of NB001 (20 mg/kg) was significantly greater than that of morphine (2 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection) and gabapentin (100 mg/kg, gavage). Recent studies have also demonstrated the analgesic effect of NB001 on animal models of gouty arthritis, migraine, and Parkinson’s disease-related pain.17–20 The analgesic effect of NB001 is believed to be produced by inhibiting several central synaptic mechanisms that are critical for chronic pain and related emotional changes. 21 They include the following: cortical postsynaptic long-term potentiation (post-LTP) and presynaptic long-term potentiation (pre-LTP) in the ACC and IC, 5 activation of various immediate early genes,22,23 upregulation of NMDA receptors 24 after injury, new protein synthesis of AC1 after injury, 15 spinal LTP and serotonin-induced facilitation.9,25

According to the instruction of relevant guidance (https://www.fda.gov/), the dose levels of human-used NB001 (hNB001) investigated in this phase I trial were determined from both preclinical toxicity studies and pharmacodynamic studies in animal models. NB001 demonstrated a fairly safe profile in animal studies (unpublished data). The no observable adverse effect level (NOAEL) of NB001 in 28-days repeat-dose toxicity studies were 1500 mg/kg/day in SD rats and 500 mg/kg/day in Beagle dogs. Taken a safety factor of 10, both NOAEL doses corresponded to a human equivalence dose (HED) of approximately 1500 mg. On the other hand, the pharmacologically active doses (PAD) of NB001 were 10 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg in rats, and 30 mg/kg in mice. These doses were converted to HEDs of 100 mg, 200 mg, and 144 mg, respectively, in men with an average body weight of 60 kg. NB001 is a first-in-class new chemical entity, and the largely different oral bioavailability of NB001 between rodents and dogs suggested further uncertainty in human studies. Therefore, a relatively conservative starting dose estimation was employed for the first-in-human (FIH) study. Using its minimal anticipated biological effect level (MABEL) and an extra safety factor of 5, the starting dose of hNB001 was calculated as 20 mg. Meanwhile, considering substantial inter-species differences in drug disposition, a maximal dose of 400 mg was also selected for the first study.

NB001 is a first-in-class AC1 inhibitor being developed for chronic pain relief. The FIH study of hNB001 was designed to evaluate the pharmacokinetic (PK) characteristics, safety, tolerability, and the effect of food intake on the PK of hNB001 in Chinese healthy volunteers. The purpose of this study was to explore a dose range of hNB001 with acceptable safety, and to identify dose levels that results in similar exposures as those correspond to the effective doses seen in preclinical in vivo studies. The conclusive doses would serve as important basis for dose selection of the proof-of-concept (POC) study in patients. Chinese Clinical Trial Registration (http://www.chinadrugtrials.org.cn) identifier: CTR20180859. Animal experiments were also carried out to confirm the analgesic effect on its role in synaptic plasticity.

Methods

Design

This single-center phase I study had three parts. Part 1 was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-ascending-dose (SAD) sub-study in 44 healthy volunteers, in which the doses of hNB001 ranged from 20 mg to 400 mg. Part 2 was a food-effect (FE) sub-study, which was designed as a randomized, open-label, two-way, crossover study in 12 subjects at dose of hNB001 100 mg. Part 3 was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple-ascending-dose (MAD) sub-study in 20 healthy volunteers, in which hNB001 or placebo was administered at doses of 100 mg twice daily or 200 mg twice daily for seven successive days.

The entire study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Council for Harmonization guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. It was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Tiantan Hospital affiliated to Capital Medical University.

Subjects

All volunteers must sign the informed consent before entering the study. Inclusion criteria included age of 18–55 years, body mass index (BMI) of 18–28 kg/m2 and acceptance of medically effective contraception for at least 3 months after the first study dose. Subjects with a history of cardiovascular, hepatic, pulmonary, renal, gastrointestinal, hematological, or neuropsychiatric disorders or a history of clinically significant allergic events or substance abuse were excluded from the study. All subjects were required to avoid intense physical exercise during the study. Drinking alcohol, tea, coffee, or other caffeinated beverages and smoking were not allowed. Except for drugs used for treatment of adverse events (AEs), concomitant medications were prohibited during the trial.

Treatments

A total of 76 Chinese healthy male or female volunteers were enrolled. In the SAD sub-study, 44 subjects were sequentially included into six dose cohorts, that is, 20 mg (N = 4), 50 mg (N = 8), 100 mg (N = 8), 200 mg (N = 8), 300 mg (N = 8), and 400 mg (N = 8). In each cohort, the subjects were 3:1 randomized into the hNB001 group or the placebo group. The investigational medication, either hNB001 or matching placebo tablet(s), was orally administered in the morning of the dosing day after overnight fasting.

Twelve participants joined the FE sub-study. Eligible subjects were 1:1 randomized to one of the two dosing sequences, namely, fasting administration followed by postprandial administration, or postprandial administration followed by fasting administration. In the two study periods, 100 mg hNB001 was swallowed either at fasting status or at 30 min after the first bite of a high-fat meal (800–1000 Kcal). The washout period was 3 days between the two doses.

In the MAD sub-study, there were two dose cohorts. Each cohort included 10 subjects, who were 8:2 randomized to receive multiple administrations of hNB001 or placebo. The first dose of investigational medication was given on Day 0. Thereafter, repeat-dose administrations started in the morning of Day 1 with a dosing interval of 12 h. The last dose (i.e., the 15th dose) occurred on Day 8 morning.

Pharmacokinetics

Blood samples were collected pre-dose and at 0.25 h, 0.5 h, 1 h, 1.5 h, 2 h, 3 h, 4 h, 6 h, 8 h, 12 h, 24 h, 36 h, and 48 h post-dose in the SAD sub-study. In the FE sub-study, serial blood samples were taken during each study period at the same time points as those arranged in the SAD sub-study. For the MAD sub-study, blood samples were collected pre-dose and at 0.25 h, 0.5 h, 1 h, 1.5 h, 2 h, 3 h, 4 h, 6 h, 8 h, 12 h, and 24 h on Day 0, within 5 min before the morning doses on Day 5, Day 6, and Day 7, and pre-dose and at 0.25 h, 0.5 h, 1 h, 1.5 h, 2 h, 3 h, 4 h, 6 h, 8 h, 12 h, 24 h, 36 h, and 48 h post-dose on Day 8.

At each time point, 4 mL of venous blood was drawn and then placed in an EDTA-K2 tube and centrifuged (1200 g, 4°C, 10 min) within 1 h of sampling. Then, the samples were transferred to two cryopreservation tubes for storage in an ultra-low temperature refrigerator at −80°C. Plasma samples were analyzed in Shanghai Teddy Clinical Laboratory. Using 13 C2, d2-hNB001 as internal standard (IS), the concentration of hNB001 in human EDTA-K2 plasma was assayed by liquid chromatography-multistage mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Human-used NB001 and IS were extracted from human plasma by protein precipitation method, and then separated by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) and detected by electrospray ionization (ESI) positive mode tandem mass spectrometry. The mass charge ratio (m/z) of NB001 was 265.1 → 130.1, and that of IS was 269.2 → 134.1. The bioanalytical method was validated before sample analysis and the lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) of hNB001 was 0.5 ng/mL.

Safety

Safety assessments were performed by collection of AEs, concomitant medications, laboratory examinations (hematology test, coagulation function, blood chemistry, and urinalysis), physical examinations, vital signs, and 12-lead electrocardiograms (ECG).

Animals

Adult (6–8 weeks old) male mice were used. C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River. Mice were maintained on a 12-h light–dark cycle. Food and water were provided ad libitum. Experiments were performed under protocols approved by the Animal Care Committee of Qingdao International Academician Park.

Acute nociception

The spinal nociceptive tail-flick reflex was evoked by focused, radiant heat (Panlab) provided by a 50-W projector lamp focused on a 1.5-mm by 10-mm area on the underside of the tail. The latency to reflexive removal of the tail from the heat was measured by a digital photocell timer to the nearest 0.1 s. The cutoff time of 10 s was used to minimize damage to the skin of the tail.

The hot plate consisted of a thermally controlled 25.4-cm by 25.4-cm metal plate (55°C) surrounded by four Plexiglas walls (Panlab). The time between placement of the mouse on the plate and the licking or lifting of a hind paw or jumping was measured with a digital timer. Mice were removed from the hot plate immediately after the first response. The cutoff time of 30 s was imposed to prevent tissue damage. All behavioral tests were performed at 10-min intervals. The response latency was an average of three or four measurements. The baseline latencies were measured 1 day before drug injection. The response latencies for the animals were then retaken on hot plate and tail-flick tests 30 min after intragastric injection of either saline or NB001.

For measuring mechanical threshold, animals were placed in individual plastic boxes and allowed to adjust to the environment for 1 h. Using the up-down paradigm, mechanical sensitivity was assessed with a set of von Frey filaments (Ugo Basile). The up-down paradigm method was used to determine the mechanical threshold. The filament was applied to the point of bending 6 times each to the dorsal surfaces of the left and right hind paws. Positive responses included prolonged hind paw withdrawal followed by licking or scratching.

Animal model of neuropathic pain

A model of neuropathic pain was induced by the ligation of the common peroneal nerve (CPN) as described previously. 26 Briefly, mice were anesthetized by 1.5% isoflurane. The left CPN was slowly ligated with chromic gut suture 5–0 (Ethicon) until contraction of the dorsiflexors of the foot was visible as twitching of the digits. Mechanical threshold was tested on postsurgical day 7.

Electrophysiological recordings

After incubation, one slice containing the ACC was transferred to the prepared MED64 probe and perfused with oxygenated (95% O2 and 5% CO2) ACSF at 28–30°C and maintained at a 2 mL/min flow rate. The slice was positioned on the MED64 probe in such a way that the different layers of the ACC were entirely covered by the whole array of the electrodes, and then a fine-mesh anchor was placed on the slice to ensure its stabilization during the experiments. One of the channels located in the layer V of the ACC was chosen as the stimulation site, from which the best synaptic responses can be induced in the surrounding recording channels. Slices were kept in the recording chamber for at least 1 h before the start of experiments. Bipolar constant current pulse stimulation (1–10 mA, 0.2 ms) was applied to the stimulation channel, and the intensity was adjusted so that a half-maximal field excitatory postsynaptic potential (fEPSP) was elicited in the channels closest to the stimulation site. The channels with fEPSPs were considered as active channels and their fEPSPs responses were sampled every 1 min and averaged every 5 min. After the baseline synaptic responses were stabilized for at least 1 h, a TBS (five trains of bursts with four pulses at 100 Hz at 200 ms interval; repeated five times at intervals of 10 s) was applied to the same stimulation channel to induce LTP. The parameter of “slope” indicated the averaged slope of each fEPSP recorded by activated channels. Stable baseline responses were first recorded until the baseline response variation less than 5% in most of the active channels within 0.5 h. After recording stable baseline, hNB001 was applied 30 min before washout in the C57BL/6 mice.

Statistical analysis

In human study, individual PK parameters were calculated using Phoenix WinNonlin (Pharsight Corp, Cary, NC, USA) version 7.0. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) version 9.4. Descriptive statistics of PK parameters were summarized by NB001 dose level or dosing condition (fasting or fed). The dose proportionality of hNB001 was analyzed using power model. The effect of food on the absorption of hNB001 tablet was analyzed using a bioequivalence approach, with which the geometric mean ratios (GMRs) of fed over fasting condition were estimated for logarithmic transformed AUC0-inf, AUC0-last, and Cmax.

Adverse events were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA 22.0). All AEs were tabulated with system organ class (SOC) and preferred term (PT) by treatment. Laboratory measurements, vital signs, ECG measurements, physical examination results, and their changes from baseline were summarized by time point and treatment.

In animal experiments, for comparisons between two groups, we used the unpaired Student’s t test or paired t test. For comparison among three groups, we used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or two-way ANOVA. Significance between groups was tested with a Bonferroni test to adjust for multiple comparisons. All data were presented as the means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). In all cases, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics

In the SAD sub-study, 44 subjects were randomized. All of them completed their study. The subjects ages 28.8 ± 5.79 (18–41) years, with an average weight of 66.91 ± 8.977 (49.9–89.6) kg and a mean BMI of 22.76 ± 2.492 (18.3–27.6) kg/m2. Subjects enrolled in each dose cohort were generally comparable in terms of age, weight, and BMI. Subjects participating in the FE sub-study (N = 12) and the MAD sub-study had similar baseline measures as those in SAD sub-study (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

Summary of the SAD sub-study volunteer characteristics.

| SAD sub-study | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 mg | 50 mg | 100 mg | 200 mg | 300 mg | 400 mg | Placebo | Total | ||

| Age | N (Nmiss) | 3 (0) | 6 (0) | 6 (0) | 6 (0) | 6 (0) | 6 (0) | 11 (0) | 44 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 25.0 (1.73) | 30.0 (8.46) | 28.8 (1.47) | 30.0 (6.81) | 25.3 (7.50) | 28.5 (3.94) | 30.6 (5.54) | 28.8 (5.79) | |

| Min, Max | 23, 26 | 19, 41 | 27, 31 | 23, 39 | 18, 39 | 21, 32 | 22, 36 | 18, 41 | |

| Gender | Male | 3 (100.0%) | 6 (100.0%) | 6 (100.0%) | 6 (100.0%) | 6 (100.0%) | 6 (100.0%) | 10 (90.9%) | 43 (97.7%) |

| Female | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (2.3%) | |

| Total | 3 (100.0%) | 6 (100.0%) | 6 (100.0%) | 6 (100.0%) | 6 (100.0%) | 6 (100.0%) | 11 (100.0%) | 44 (100.0%) | |

| Weight (kg) | N (Nmiss) | 3 (0) | 6 (0) | 6 (0) | 6 (0) | 6 (0) | 6 (0) | 11 (0) | 44 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 62.43 (6.516) | 65.53 (4.806) | 70.97 (11.867) | 62.15 (8.158) | 66.90 (7.239) | 65.70 (10.895) | 69.94 (9.781) | 66.91 (8.977) | |

| Min, Max | 56.2, 69.2 | 60.0, 71.0 | 58.3, 89.6 | 51.1, 75.7 | 54.1, 73.8 | 55.2, 85.1 | 49.9, 84.4 | 49.9, 89.6 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | N (Nmiss) | 3 (0) | 6 (0) | 6 (0) | 6 (0) | 6 (0) | 6 (0) | 11 (0) | 44 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 21.60 (3.105) | 21.90 (1.077) | 24.18 (2.250) | 20.88 (1.890) | 22.48 (2.551) | 23.05 (2.510) | 23.77 (2.842) | 22.76 (2.492) | |

| Min, Max | 18.6, 24.8 | 20.8, 23.2 | 20.9, 26.2 | 19.8, 24.7 | 18.3, 26.2 | 19.8, 26.9 | 18.3, 27.6 | 18.3, 27.6 | |

Table 2.

Summary of the MAD sub-study and FE sub-study volunteer characteristics.

| MAD sub-study | FE sub-study | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 mg | 200 mg | Placebo | Total | Total | ||

| Age | N (Nmiss) | 8 (0) | 8 (0) | 4 (0) | 20 (0) | 12 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 28.8 (3.62) | 27.6 (5.07) | 28.3 (4.35) | 28.2 (4.19) | 28.7 (6.71) | |

| Min, Max | 23, 35 | 21, 35 | 24, 34 | 21, 35 | 19, 39 | |

| Gender | Male | 6 (75.0%) | 7 (87.5%) | 4 (100.0%) | 17 (85.0%) | 10 (83.3%) |

| Female | 2 (25.0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0 | 3 (15.0%) | 2 (16.7%) | |

| Total | 8 (100.0%) | 8 (100.0%) | 4 (100.0%) | 20 (100.0%) | 12 (100.0%) | |

| Weight (kg) | N (Nmiss) | 8 (0) | 8 (0) | 4 (0) | 20 (0) | 12 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 63.79 (8.435) | 62.38 (7.166) | 61.10 (0.497) | 62.69 (6.801) | 65.06 (8.439) | |

| Min, Max | 55.7, 81.0 | 52.7, 72.7 | 60.5, 61.7 | 52.7, 81.0 | 54.6, 76.3 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | N (Nmiss) | 8 (0) | 8 (0) | 4 (0) | 20 (0) | 12 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 22.38 (2.470) | 21.90 (1.495) | 23.23 (0.741) | 22.36 (1.845) | 22.27 (2.803) | |

| Min, Max | 18.8, 26.8 | 19.7, 23.5 | 22.4, 23.9 | 18.8, 26.8 | 18.6, 25.7 | |

All subjects completed the study per protocol. Pharmacokinetic and safety analyses were performed on data from all treated subjects.

Pharmacokinetics

After a single oral administration of hNB001 tablet, the compound was absorbed rapidly. The median time to peak plasma concentration (Tmax) varied between 0.5 h and 3 h in the dose groups. A double-peak pattern was observed in the average PK profiles of most dose groups within 4 h post-dose (Figure 1), suggesting multiple-sites of intestinal absorption. Mean peak concentrations (Cmax) of hNB001 ranged from 3.1692 ± 1.7546 to 91.7961 ± 63.3739 ng/mL after single doses of 20 mg–400 mg. Plasma exposures, as measured by AUC0-last and AUC0-inf, increased roughly dose proportionally from 11.9163 ± 6.9028 and 19.4965 ± 0.1742 h·ng/mL at 20 mg to 343.4537 ± 78.1085 h·ng/mL and 396.3935 ± 88.9971 h·ng/mL at 400 mg. The apparent clearance (CL/F) of hNB001 was generally comparable among different dose groups, indicating linear PK. However, the terminal half-life (T1/2) appeared to prolong with dose escalation. This finding was in line with the biphasic elimination profiles seen in the semi-log concentration-time curves of the high-dose groups of hNB001, where the lowest two dose groups demonstrated lower than LLOQ concentration level after 12 h post-dose (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Linear scale plasma concentration-time curve after single oral. Linear Scale of mean drug concentrations profile following single oral administration of 20 mg (n = 3), 50 mg (n = 6), 100 mg (n = 6), 200 mg (n = 6), 300 mg (n = 6), and 400 mg (n = 6) hNB001 tablet in 0–12 h in human.

Figure 2.

Semi-logarithmic scale plasma concentration-time curve after single oral. Semi-logarithmic scale of mean (SD) drug concentrations profile following single oral administration of 20 mg (n = 3), 50 mg (n = 6), 100 mg (n = 6), 200 mg (n = 6), 300 mg (n = 6), and 400 mg (n = 6) hNB001 tablet in 0–48 h in human.

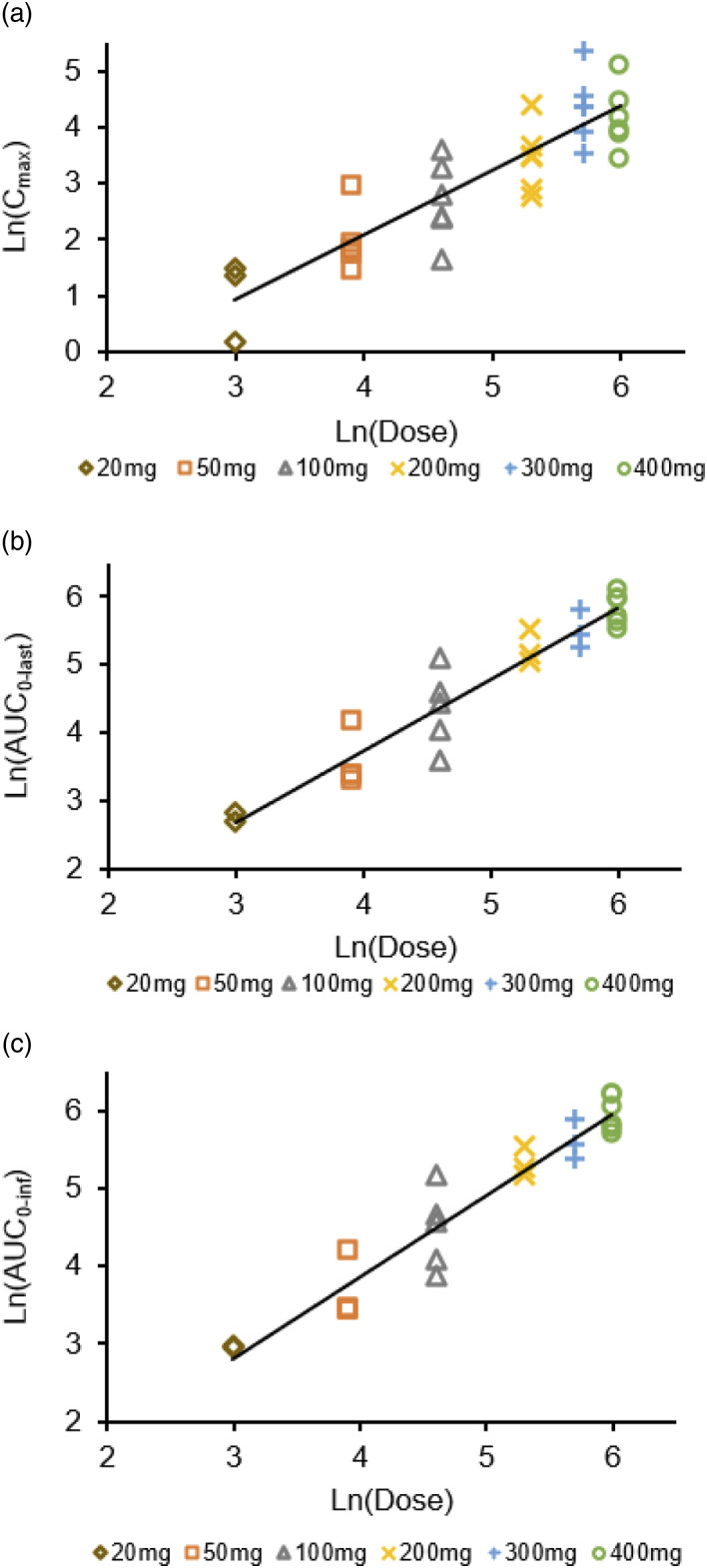

As can be seen in Figure 3, the estimated slope β1 values of Cmax, AUC0-last, and AUC0-inf of hNB001 were 1.1518, 1.1827, and 1.0516, respectively, indicating dose-proportional increase of plasma hNB001 exposure among the doses from 20 mg to 400 mg. Pharmacokinetic parameters following single oral administration of hNB001 20 mg–400 mg are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 3.

Proportional dose relationship after a single oral administration. (a) Proportional dose relationship of Cmax after a single oral administration of 20 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg, 200 mg, 300 mg and 400 mg hNB001 tablet in human. (b) Proportional dose relationship of AUC0-last after a single oral administration of 20 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg, 200 mg, 300 mg and 400 mg hNB001 tablet in human. (c) Proportional dose relationship of AUC0-inf after a single oral administration of 20 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg, 200 mg, 300 mg and 400 mg hNB001 tablet in human.

Table 3.

Summary of pharmacokinetic parameters following single oral administration of 20 mg–400 mg hNB001 in the SAD sub-study.

| Dose group | Parameter | Tmax (h) | Cmax (ng/mL) | AUC0-last (h*ng/mL) | AUC0-inf (h*ng/mL) | T1/2 (h) | Vz/F (L) | CL/F (L/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 mg (N = 3) | n | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Mean | 3.1692 | 11.9163 | 19.4965 | 4.40 | 6499.0730 | 1025.8666 | ||

| SD | 1.7546 | 6.9028 | 0.1742 | 1.51 | 2173.0308 | 9.1676 | ||

| Min | 0.25 | 1.1765 | 4.0239 | 19.3733 | 3.33 | 4962.5082 | 1019.3841 | |

| Max | 1.00 | 4.4822 | 16.8272 | 19.6197 | 5.46 | 8035.6378 | 1032.3491 | |

| 50 mg (N = 6) | n | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Mean | 8.0770 | 35.2268 | 40.3083 | 2.78 | 5824.2470 | 1383.6203 | ||

| SD | 5.5781 | 14.8169 | 17.9986 | 1.34 | 3841.2642 | 427.7209 | ||

| Min | 0.50 | 4.2505 | 26.3905 | 30.8248 | 1.99 | 2129.2038 | 742.9677 | |

| Max | 4.00 | 19.3153 | 64.9508 | 67.2977 | 4.79 | 11,220.7753 | 1622.0704 | |

| 100 mg (N = 6) | n | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Mean | 17.7066 | 91.1995 | 97.1249 | 11.98 | 21,360.9849 | 1263.1450 | ||

| SD | 11.6095 | 43.6741 | 50.3619 | 7.20 | 19,704.2812 | 608.0415 | ||

| Min | 1.50 | 5.1790 | 36.3961 | 48.1065 | 2.13 | 5171.1986 | 567.6697 | |

| Max | 4.00 | 36.3030 | 162.0105 | 176.1588 | 17.90 | 53,686.1628 | 2078.7228 | |

| 200 mg (N = 6) | n | 6 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Mean | 40.1860 | 181.9156 | 208.6215 | 19.35 | 28,485.6391 | 983.2640 | ||

| SD | 22.1888 | 40.3246 | 42.3352 | 6.39 | 13,729.4781 | 182.1469 | ||

| Min | 1.50 | 18.3272 | 132.9652 | 177.2190 | 13.41 | 15,069.4155 | 778.9141 | |

| Max | 6.00 | 82.5742 | 248.1377 | 256.7677 | 26.11 | 42,508.2760 | 1128.5472 | |

| 300 mg (N = 6) | n | 6 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Mean | 91.7961 | 312.3117 | 279.5103 | 18.51 | 30,104.9054 | 1121.3311 | ||

| SD | 63.3739 | 100.1970 | 73.9833 | 6.17 | 12,442.0968 | 274.2648 | ||

| Min | 2.00 | 34.3458 | 190.3882 | 218.4435 | 14.77 | 18,107.1750 | 829.2329 | |

| Max | 4.00 | 212.8810 | 429.4125 | 361.7802 | 25.63 | 42,948.2299 | 1373.3526 | |

| 400 mg (N = 6) | n | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Mean | 74.1981 | 343.4537 | 396.3935 | 21.28 | 31,382.8841 | 1052.2830 | ||

| SD | 47.2512 | 78.1085 | 88.9971 | 9.44 | 14,272.8086 | 232.1570 | ||

| Min | 0.50 | 30.7477 | 247.8564 | 300.7818 | 12.54 | 18,947.4489 | 801.3192 | |

| Max | 4.00 | 163.0100 | 450.0673 | 499.1769 | 34.18 | 58,047.1854 | 1329.8679 |

Tmax (Time at which the highest drug concentration occurs).

Cmax (The highest drug concentration).

AUC0-last (The AUC from 0 o’clock to the last time point when the concentration can be accurately measured).

AUC0-inf (The AUC from 0 to infinity).

T1/2 (Elimination half-life).

Vz/F (Apparent distribution volume).

CL/F (Apparent clearance).

In the FE sub-study, the point estimates and 90% confident intervals (90% CIs) of GMRs of Cmax, AUC0-last, and AUC0-inf of hNB001 were 107.05% (86.21%–132.93%), 105.50% (90.92%–122.43%), and 101.72% (75.59%–136.88%), respectively. In addition, the median time to peak concentration was 2.5 h and 3.0 h following postprandial and fasting administration, respectively. These results suggested minimal food effect on the bioavailability of hNB001.

In the MAD sub-study, twice daily administration of hNB001 led to achievement of steady-state on Day 5. Table 4 presents the summary of hNB001 PK parameters after single and repeat doses, respectively. The accumulation ratio was 1.31–1.50 for AUC0–12h and 1.11 to 1.35 for Cmax at the two experimental doses.

Table 4.

Summary of pharmacokinetic parameters following multiple oral administration of 100 mg–200 mg hNB001 on Day 0 and Day 8 in the MAD sub-study.

| Dose group | Day | Parameter | Tmax (h) | Cmax (ng/mL) | AUC0-last (h*ng/mL) | AUC0-inf (h*ng/mL) | T1/2 (h) | Vz/F (L) | CL/F (L/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 mg (N = 8) | Day 0 | n | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Mean | 22.3882 | 101.9429 | 106.8373 | 6.51 | 9974.3106 | 1167.2304 | |||

| SD | 11.6781 | 45.6682 | 54.5920 | 3.33 | 6058.3023 | 617.3944 | |||

| Min | 0.50 | 10.2405 | 41.8616 | 43.9325 | 1.92 | 3247.4276 | 505.9853 | ||

| Max | 6.00 | 46.4684 | 188.8654 | 197.6342 | 10.61 | 19,603.4549 | 2276.2183 | ||

| Day 8 | n | 8 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Mean | 22.1310 | 202.0401 | 271.4821 | 28.92 | 35,400.3641 | 867.5060 | |||

| SD | 6.8985 | 82.8570 | 86.4490 | 11.28 | 14,348.8025 | 213.8033 | |||

| Min | 0.50 | 12.1751 | 99.6047 | 150.3312 | 17.03 | 20,104.5296 | 704.5807 | ||

| Max | 4.00 | 32.6294 | 364.3057 | 359.0812 | 44.07 | 57,823.4044 | 1222.2679 | ||

| 200 mg (N = 8) | Day 0 | n | 8 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Mean | 35.7360 | 154.0939 | 165.4215 | 11.59 | 22,324.9070 | 1288.8793 | |||

| SD | 21.0912 | 47.2073 | 48.6236 | 2.24 | 9782.8682 | 346.7914 | |||

| Min | 1.00 | 13.9540 | 94.1623 | 121.2985 | 9.34 | 11,254.5056 | 834.8034 | ||

| Max | 4.00 | 76.5630 | 218.6206 | 239.5774 | 15.11 | 35,285.3026 | 1648.8257 | ||

| Day 8 | n | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Mean | 43.0689 | 314.3201 | 380.3028 | 25.88 | 44,285.7328 | 1178.2339 | |||

| SD | 18.3971 | 73.3493 | 92.6308 | 5.33 | 13,892.0948 | 259.2433 | |||

| Min | 1.00 | 24.1019 | 196.4047 | 245.9573 | 21.54 | 32,080.5854 | 1010.7814 | ||

| Max | 4.00 | 71.0706 | 436.1206 | 452.7297 | 33.27 | 59,094.6175 | 1562.0914 |

Tmax (Time at which the highest drug concentration occurs).

Cmax (The highest drug concentration).

AUC0-last (The AUC from 0 o’clock to the last time point when the concentration can be accurately measured).

AUC0-inf (The AUC from 0 to infinity).

T1/2 (Elimination half-life).

Vz/F (Apparent distribution volume).

CL/F (Apparent clearance).

Safety

No serious adverse event (SAE) was reported. There was no AEs leading to death, discontinuation of the investigational medication, or premature study cessation. All AEs were mild and self-limiting. Most AEs were laboratory abnormalities, which were classified as the SOC of “Inspections” and judged “possibly related” to the investigational medication by the investigators.

In the SAD sub-study, a total of 9 AEs were reported by eight subjects (incidence: 18.2%). The incidence of AEs varied between 9.1% and 33.3% in the hNB001 groups and the placebo group (Table 5). In the FE sub-study, 8 AEs occurred in six subjects (50.0%), including 6 cases (33.3%) appeared after the fasting dose and 2 cases (16.7%) after the fed dose. In the MAD sub-study, a total of nine subjects (45%) reported 15 AEs, including two subjects (25.0%) in the hNB001 100 mg BID group, five subjects (62.5%) in the hNB001 200 mg BID group, and two subjects (50.0%) in the placebo group (Table 6). However, the incidences of adverse drug reactions, which is defined as AEs that were judged to be “related to” the investigational medication, were 12.5%, 12.5%, and 50.0%, respectively, in the three groups.

Table 5.

Summary of adverse events (AE) in the SAD sub-study.

| SOC | 20 mg | 50 mg | 100 mg | 200 mg | 300 mg | 400 mg | Placebo | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT | n | N (%) | n | N (%) | n | N (%) | n | N (%) | n | N (%) | n | N (%) | n | N (%) | n | N (%) |

| Total | 2 | 1 (33.3%) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 (33.3%) | 2 | 2 (33.3%) | 1 | 1 (16.7%) | 1 | 1 (16.7%) | 1 | 1 (9.1%) | 9 | 8 (18.2%) |

| Investigations | 1 | 1 (33.3%) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (16.7%) | 1 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 (9.1%) |

| Blood pressure increased | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (2.3%) |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 1 | 1 (33.3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 (4.5%) |

| Serum uric acid increased | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (2.3%) |

| Nervous system disorders | 1 | 1 (33.3%) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (9.1%) | 3 | 3 (6.8%) |

| Drowsiness | 1 | 1 (33.3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (9.1%) | 2 | 2 (4.5%) |

| Dizziness | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (2.3%) |

| Systemic diseases and various reactions at the administration site | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (2.3%) |

| Chest pain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (2.3%) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (2.3%) |

| Abdominal pain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (2.3%) |

n(Numbers of AEs).

N (Numbers of subjects with AE).

Table 6.

Summary of adverse events (AE) in the MAD sub-study.

| SOC | 100 mg | 200 mg | Placebo | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT | n | N (%) | n | N (%) | n | N (%) | n | N (%) |

| Total | 2 | 2 (25%) | 9 | 5 (62.5%) | 4 | 2 (50%) | 15 | 9 (45%) |

| Investigations | 2 | 2 (25%) | 7 | 4 (50%) | 3 | 2 (50%) | 12 | 8 (40%) |

| White blood cell decreased | 1 | 1 (12.5%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (5%) |

| White blood cell in urine positive | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (12.5%) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (5%) |

| Red blood cell in urine positive | 1 | 1 (12.5%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (5%) |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (12.5%) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (5%) |

| Blood triglyceride increased | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (12.5%) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (5%) |

| Serum uric acid increased | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (25%) | 1 | 1 (5%) |

| Blood glucose decreased | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 (37.5%) | 1 | 1 (25%) | 4 | 4 (20%) |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (12.5%) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (5%) |

| Aminopherase increased | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (25%) | 1 | 1 (5%) |

| Nervous system disorders | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (12.5%) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (5%) |

| Drowsiness | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (12.5%) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (5%) |

| Systemic diseases and various reactions at the administration site | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (12.5%) | 1 | 1 (25%) | 2 | 2 (10%) |

| Chest pain | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (12.5%) | 1 | 1 (25%) | 2 | 2 (10%) |

n (Numbers of AEs).

N (Numbers of subjects with AE).

There was no obvious trend of AE increase with hNB001 dose escalation. No statistically significant correlation was observed between AE incidence and the exposure of hNB001 (AUC, Cmax).

hNB001 has no significant effect on nociceptive responses

Previous studies with non-human-used NB001 reported that NB001 affected behavior in neither the spinal nociceptive tail-flick reflex nor the hot-plate test (at 55°C). 12 Here, we carried out behavioral tests to determine whether hNB001 affects physiological nociceptive responses in normal mice. We tested the effect of intragastric injected hNB001 (40 mg/kg) in different nociceptive tests. For mechanical threshold, we measured hind paw withdrawal responses to von Frey filaments in normal mice. hNB001 did not produce any significant effect to the mechanical pain threshold (0.5 ± 0.06 g in hNB001 group vs. 0.5 ± 0.07 g in saline group, n = 15 in each group, t(28) = 0.388, p = 0.701, Figure 4(a)). For noxious thermal pain, we measured the latency of spinal nociceptive tail-flick reflex and the hot-plate test (tail-flick test: 7.7 ± 0.2 s in hNB001 group vs. 7.8 ± 0.5 s in saline group, n = 10 in each group, t(18) = 0.305, p = 0.764 and hot-plate test: 9.8 ± 1.1 s in hNB001 group vs. 8.5 ± 0.6 s in saline group, n = 8 in hNB001 group and n = 12 in saline group, t(18) = 1.229, p = 0.235, Figure 4(b) and (c)). Again, hNB001 did not produce any significant effect to the thermal pain. These results suggest that hNB001 did not affect acute nociception, in good accord with previous findings of unchanged physiological pain in AC1 knockout mice and non-human-used NB001.8,12

Figure 4.

Effect of hNB001 on acute pain. (a) Comparison of behavioral responses to non-noxious mechanical stimulus. There was no significant difference in hind paw withdrawal to von Frey filaments before and after intragastric injection of saline (n = 15) and 40 mg/kg hNB001 (n = 15). (b) Effect of hNB001 in tail-flick (TF) test. hNB001 (10 mg/kg i. g.) did not affect spinal nociceptive TF reflex (n = 10 for hNB001 group and n = 10 for control group). (c) Effect of hNB001 in hot-plate test at 55°C. There was no significant difference in response latency before and after intragastric injection of saline (n = 8) and hNB001 (10 mg/kg) (n = 12).

Analgesic effects of NB001 in animal models of neuropathic pain

Previous studies with genetic knockout mice lacking AC1 and an inhibitor for AC1 NB001 showed that behavioral allodynia in animal models of neuropathic pain and inflammatory pain was significantly reduced.8,12 Similar to the previous report,26,27 we used the CPN ligation model as the model of neuropathic pain (Figure 5(a)). The behavioral decrease mechanical threshold was found on day 7 after the nerve injury. Intragastric administration of hNB001 (40 mg/kg) given 45 min before the behavior test produced a significant analgesic effect (CPN group: 1.0 ± 0.1 g before the surgery, 0.3 ± 0.05 g at 7 days after the surgery, 0.5 ± 0.1 g after the application of hNB001, n = 13 in CPN group, F(2,36) = 7.990; sham group: 0.9 ± 0.09 g before the surgery, 0.9 ± 0.1 g at 7 days after the surgery, 1.0 ± 0.2 g after the application of hNB001, n = 10 in sham group, F(2,27) = 0.798, p < 0.001) (Figure 5(b)). Since a recent study reported that NB001 produced similar potent analgesic effects in adult female mice compared with male mice. 28 Therefore, we assume there is no gender difference in the analgesic effect of hNB001 in rodents.

Figure 5.

Effect of hNB001 on neuropathic pain. (a) Schematic diagram showing the common peroneal nerve (CPN) model. The sciatic nerve has three terminal branches: the sural nerve (SN), CPN, and tibial nerve (TN). The CPN was ligated but leaving the TN and SN intact. (b) Effect of hNB001 on mechanical threshold after common peroneal nerve (CPN) ligation (left) and sham surgery (right). Intragastric administration of hNB001 (40 mg/kg body weight) given 45 min before von Frey testing produced a significant analgesic effect (n = 13 for CPN group and n = 10 for sham group). Mechanical threshold was measured before the ligation surgery, 7 days after the surgery and at 45 min after intragastric application of hNB001. ***p<0.001compared with before surgery, #p < 0.05 compared with 7 days after surgery.

hNB001 blocked the network LTP without affecting the basal transmission

Previous study has shown that an AC1 inhibitor NB001 blocks the LTP in the ACC.12,29 Here we tested whether bath application of hNB001 could induce the similar blocking effect on the network LTP in the ACC slices. In the presence of hNB001 (10 μM), we found that LTP induction was totally blocked (Figure 6). Figure 3(b) showed two examples of two active channels in the superficial layers with or without hNB001 application. After TBS, the hNB001 group failed to undergo any potentiation (hNB001 group was 99.7% and control was 147.3% of baseline at 2 h after TBS, n = 7 slices/3 mice for hNB001 group and n = 4 slices/3 mice from saline group, t(8) = 14.458 from the last 20 min, p < 0.001). In a total of 38 channels from seven slices with hNB001, TBS did not induce LTP in 30 channels (averaged as 113.8 ± 6.4% of baseline at 2 h after TBS), while in a total of 46 channels from four slices without hNB001, LTP was induced in 36 channels (averaged as 144.9 ± 6.7% of baseline at 2 h after TBS) (Figure 6(c)).

Figure 6.

Effect of hNB001 on the LTP of the fEPSPs induction in the ACC. (a) Two mapped figures show the evoked field potentials in the ACC with (left) and without (right) the application of 10 μM hNB001. Field potentials were recorded from the other 63 channels 0.5 h before (black) and 2 h (red) after TBS being delivered to one channel marked as “s”. (b) The fEPSP slope (bottom) and the superimposed samples (top) from one channel show that hNB001 blocked the induction of LTP (red circles) but the control group without hNB001 remains the LTP intact (black squares). (c) The summarized fEPSP slopes show that hNB001 blocked potentials from seven slices in three mice (red circles). The summarized fEPSP slopes show that LTP from four slices in three mice (black squares).

hNB001 blocked the channel recruitment induced by TBS

Multi-channels recording provides a convenient way to study the cortical network LTP. Previous studies have proved that TBS can induce channel recruitment in the ACC of adult mice, which was demonstrated by the spread of active response around the stimulation site. 30 Using previous NB001, investigators found that bath application of NB001 did not affect the number of activated channels but blocked the TBS induced channel recruitment. 29 Here we used the same approaches to test the effect of hNB001. We found that the number of activated channels increase at 2 h after TBS (13.7 ± 2.2 after TBS vs. 12.0 ± 1.8 before TBS, Figure 7(b)) in normal slices of ACC. However, in the group applying hNB001, no significant channel recruitment was observed (10.7 ± 2.7 after TBS vs. 10.1 ± 2.4 before TBS, Figure 7(a); n = 7 slices/3 mice for hNB001 group and n = 6 slices/3 mice from saline group, t(11) = 1.732, p = 0.019, Figure 7(c)). The average amplitude of the recruited responses finally reached as 8.2 ± 1.4 μV in control group while 4.2 ± 2.6 μV in hNB001 group, t(8) = 9.993, p < 0.001, from the last 20 min. There results indicated that hNB001 blocked the channel recruitment induced by TBS.

Figure 7.

Effect of NB001 on the recruited responses induced by TBS. (a) Baseline areas of activated sites with fEPSPs (blue) was not enlarged after TBS (red) in the presence of hNB001 (10 μM). (b) Polygonal diagrams of showed the baseline areas of the activated sites with fEPSPs (blue) and the enlarged areas after TBS (red) in normal slices without hNB001. Overlapped blue or red regions indicated the high frequently activated areas. (c) Summarize number of recruited channels (n = 7 slices/3 mice for hNB001 group and n = 6 slices/3 mice for saline group) that are activated before and after TBS induction. (d) Summarized results showing the temporal changes of the EPSP amplitude.

Discussion

This study was conducted to investigate the PK characteristics, safety, and tolerability of hNB001 in healthy volunteers, and the effect of food intake on the PK of hNB001. In conclusion, the present FIH study delineated the PK properties of hNB001 formulated as immediate-release tablet. A linear dose-exposure relationship was demonstrated at doses between 20 mg and 400 mg, with which dosing regimens of 400 mg BID or 600 mg QD are expected to reach systemic exposures correspond to effective doses detected in animal models. The relatively small systemic exposure of hNB001 in human suggested low bioavailability of this compound through oral administration. Food intake had minimal impact on the absorption of hNB001 tablet. hNB001 showed placebo-like safety and good tolerability in healthy volunteers. In animals, hNB001 had no significant effect on acute pain but alleviated chronic pain. In the ACC of mice, hNB001 blocked the induction of LTP. Such favorable behaviors support future clinical exploration of this compound with higher dosage. These results of hNB001 are in consistent with previous animals’ studies using NB001 which is designed for research tool in the lab.12–14,17,28,31

With dose escalation, the exposure of hNB001 increased proportionally, suggesting linear PK. Before the start of this study, the HED of hNB001 20 mg/kg in rats was estimated to be approximately 200 mg for a man with 60 kg body weight. In the current study, the average AUC0-inf in the 200 mg group was relatively lower than those observed in rats with 20 mg/kg. Given the relatively slower elimination half-life of hNB001 in human, the reduced dose-exposure relationship indicated even lower bioavailability of hNB001 in men than in rats, which might be explained by the low permeability of this compound assessed by the Caco-2 cell monolayer. A double-peak pattern was observed in the absorption phase of hNB001 PK profile. This may be attributed to inadequate formulation property or compound-specific multiple-site absorption.

In addition, food intake had minimal effect on the absorption of hNB001. High-fat food intake usually causes changes of gastrointestinal fluids and prolongs gastrointestinal transition time. Our findings further confirm the lack of body-formulation interaction with the hNB001 tablet. Future clinical trials with hNB001 tablets may relax the requirement for food intake.

The aim of this phase I study was to identify one or two proper doses to be used in the POC study in cancer patients. Since no pharmacodynamic biomarkers were assessed in the phase I study, the only clue we can rely on is the exposure of NB001 in rats under the pharmacodynamically effective dose, that is, 20 mg/kg. The average exposure parameters of rats after oral administration of 20 mg/kg NB001 were 175 ± 44.2 ng/mL for Cmax and 634 ± 182 ng·h/mL for AUC0-last. Such exposure levels were set as the target exposure levels in human pharmacology study. Compared to PK parameters obtained in this human study, single oral dose of hNB001 tablet 400 mg resulted in an average AUC value close to the target AUC value in rats. Moreover, the accumulation ratio of hNB001 AUC after twice daily repeat doses suggested twice daily administration of 300 mg or 400 mg hNB001 tablet may result in a systemic exposure similar to those seen in rats dosed with 20 mg/kg NB001 by gavage. Likewise, given the linear PK of hNB001, good safety and relatively long elimination half-life observed in human, an alternative approach is to use higher single doses but longer dosing interval, such as 600 mg QD, in the POC study.

Our studies provide the first evidence that inhibiting AC1 activity in healthy human is safe. The same analgesic effect of NB001 on animal models of chronic pain is observed in both the present animal studies and previous reports. These results lay the foundation of pharmacologically inhibiting AC1 as the treatment of patients suffering chronic pain in future clinical studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Zhejiang Forevercheer Medicine Technology Co., Ltd. for sponsoring this study. We also would like to express our gratitude to all the volunteers who participated in the study for their contribution to medicine and science.

Footnotes

Author contributions: X.C. designed the research plan of human subjects, and M.Z. and Q.Y.C. designed animal studies. X.C., W.C.W. wrote the clinical trial protocol. X.C., W.C.W., Q.Y.C., P.P.Z., J.B.Z., Y.W., X.R.L. performed the research. W.C.W., Q.Y.C., M.Z. and X.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed towards critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content, approve the final manuscript, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work and will ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Incubation Programme PG2018006.

Ethical standards: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

ORCID iDs

Weicong Wang https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6524-4901

Qi-Yu Chen https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5707-6220

References

- 1.Sostres C, Gargallo CJ, Arroyo MT, Lanas A. Adverse effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, aspirin and coxibs) on upper gastrointestinal tract. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2010; 24: 121–132. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpg.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conforti A, Leone R, Moretti U, Mozzo F, Velo G. Adverse drug reactions related to the use of NSAIDs with a focus on nimesulide: results of spontaneous reporting from a Northern Italian area. Drug Saf 2001; 24: 1081–1090. DOI: 10.2165/00002018-200124140-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DuPen A, Shen D, Ersek M. Mechanisms of opioid-induced tolerance and hyperalgesia. Pain Manag Nurs 2007; 8: 113–121. DOI: 10.1016/j.pmn.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogt BA. Pain and emotion interactions in subregions of the cingulate gyrus. Nat Rev Neurosci 2005; 6: 533–544. DOI: 10.1038/nrn1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bliss TV, Collingridge GL, Kaang BK, Zhuo M. Synaptic plasticity in the anterior cingulate cortex in acute and chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2016; 17: 485–496. DOI: 10.1038/nrn.2016.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhuo M. Cortical excitation and chronic pain. Trends Neurosci 2008; 31: 199–207. DOI: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang SJ, Kwak C, Lee J, Sim SE, Shim J, Choi T, Collingridge GL, Zhuo M, Kaang BK. Bidirectional modulation of hyperalgesia via the specific control of excitatory and inhibitory neuronal activity in the ACC. Mol Brain 2015; 8: 81. DOI: 10.1186/s13041-015-0170-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei F, Qiu CS, Kim SJ, Muglia L, Maas JW, Pineda VV, Xu HM, Chen ZF, Storm DR, Muglia LJ, Zhuo M. Genetic elimination of behavioral sensitization in mice lacking calmodulin-stimulated adenylyl cyclases. Neuron 2002; 36: 713–726. DOI: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei F, Vadakkan KI, Toyoda H, Wu LJ, Zhao MG, Xu H, Shum FW, Jia YH, Zhuo M. Calcium calmodulin-stimulated adenylyl cyclases contribute to activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase in spinal dorsal horn neurons in adult rats and mice. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 851–861. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3292-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhuo M. Targeting neuronal adenylyl cyclase for the treatment of chronic pain. Drug Discov Today 2012; 17: 573–582. DOI: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li XH, Chen QY, Zhuo M. Neuronal adenylyl cyclase targeting central plasticity for the treatment of chronic pain. Neurotherapeutics 2020; 17: 861–873. DOI: 10.1007/s13311-020-00927-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H, Xu H, Wu LJ, Kim SS, Chen T, Koga K, Descalzi G, Gong B, Vadakkan KI, Zhang X, Kaang BK, Zhuo M. Identification of an adenylyl cyclase inhibitor for treating neuropathic and inflammatory pain. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3: 65ra3. DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang W-b, Yang Q, Guo Y-y, Wang L, Wang D-s, Cheng Q, Li X-m, Tang J, Zhao J-n, Liu G, Zhuo M, Zhao M-g. Analgesic effects of adenylyl cyclase inhibitor NB001 on bone cancer pain in a mouse model. Mol Pain 2016; 12: 174480691665240. DOI: 10.1177/1744806916652409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang MM, Liu SB, Chen T, Koga K, Zhang T, Li YQ, Zhuo M. Effects of NB001 and gabapentin on irritable bowel syndrome-induced behavioral anxiety and spontaneous pain. Mol Brain 2014; 7: 47. DOI: 10.1186/1756-6606-7-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu SB, Wang XS, Yue J, Yang L, Li XH, Hu LN, Lu JS, Song Q, Zhang K, Yang Q, Zhang MM, Bernabucci M, Zhao MG, Zhuo M. Cyclic AMP-dependent positive feedback signaling pathways in the cortex contributes to visceral pain. J Neurochem 2020; 153: 252–263. DOI: 10.1111/jnc.14903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vadakkan KI, Wang H, Ko SW, Zastepa E, Petrovic MJ, Sluka KA, Zhuo M. Genetic reduction of chronic muscle pain in mice lacking calcium/calmodulin-stimulated adenylyl cyclases. Mol Pain 2006; 2: 7. DOI: 10.1186/1744-8069-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu RH, Shi W, Zhang YX, Zhuo M, Li XH. Selective inhibition of adenylyl cyclase subtype 1 reduces inflammatory pain in chicken of gouty arthritis. Mol Pain 2021; 17: 17448069211047863. DOI: 10.1177/17448069211047863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou Z, Ye P, Li XH, Zhang Y, Li M, Chen QY, Lu JS, Xue M, Li Y, Liu W, Lu L, Shi W, Xu PY, Zhuo M. Synaptic potentiation of anterior cingulate cortex contributes to chronic pain of Parkinson's disease. Mol Brain 2021; 14: 161. DOI: 10.1186/s13041-021-00870-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li XH, Matsuura T, Liu RH, Xue M, Zhuo M. Calcitonin gene-related peptide potentiated the excitatory transmission and network propagation in the anterior cingulate cortex of adult mice. Mol Pain 2019; 15: 1744806919832718. DOI: 10.1177/1744806919832718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, Chen QY, Lee JH, Li XH, Yu S, Zhuo M. Cortical potentiation induced by calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) in the insular cortex of adult mice. Mol Brain 2020; 13: 36. DOI: 10.1186/s13041-020-00580-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhuo M. Neural mechanisms underlying anxiety-chronic pain interactions. Trends Neurosci 2016; 39: 136–145. DOI: 10.1016/j.tins.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei F, Li P, Zhuo M. Loss of synaptic depression in mammalian anterior cingulate cortex after amputation. J Neurosci 1999; 19: 9346–9354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ko SW, Vadakkan KI, Ao H, Gallitano-Mendel A, Wei F, Milbrandt J, Zhuo M. Selective contribution of Egr1 (zif/268) to persistent inflammatory pain. J Pain 2005; 6: 12–20. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qiu S, Chen T, Koga K, Guo YY, Xu H, Song Q, Wang JJ, Descalzi G, Kaang BK, Luo JH, Zhuo M, Zhao MG. An increase in synaptic NMDA receptors in the insular cortex contributes to neuropathic pain. Sci Signaling 2013; 6: ra34. DOI: 10.1126/scisignal.2003778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang GD, Zhuo M. Synergistic enhancement of glutamate-mediated responses by serotonin and forskolin in adult mouse spinal dorsal horn neurons. J Neurophysiol 2002; 87: 732–739. DOI: 10.1152/jn.00423.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vadakkan KI, Jia YH, Zhuo M. A behavioral model of neuropathic pain induced by ligation of the common peroneal nerve in mice. J Pain 2005; 6: 747–756. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu H, Wu LJ, Wang H, Zhang X, Vadakkan KI, Kim SS, Steenland HW, Zhuo M. Presynaptic and postsynaptic amplifications of neuropathic pain in the anterior cingulate cortex. J Neurosci 2008; 28: 7445–7453. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1812-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou Z, Shi W, Fan K, Xue M, Zhou S, Chen QY, Lu JS, Li XH, Zhuo M. Inhibition of calcium-stimulated adenylyl cyclase subtype 1 (AC1) for the treatment of neuropathic and inflammatory pain in adult female mice. Mol Pain 2021; 17: 17448069211021698. DOI: 10.1177/17448069211021698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen T, O'Den G, Song Q, Koga K, Zhang MM, Zhuo M. Adenylyl cyclase subtype 1 is essential for late-phase long term potentiation and spatial propagation of synaptic responses in the anterior cingulate cortex of adult mice. Mol Pain 2014; 10: 65. DOI: 10.1186/1744-8069-10-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen T, Lu JS, Song Q, Liu MG, Koga K, Descalzi G, Li YQ, Zhuo M. Pharmacological rescue of cortical synaptic and network potentiation in a mouse model for fragile X syndrome. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014; 39: 1955–1967. DOI: 10.1038/npp.2014.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li XH, Chen QY, Zhuo M. Correction to: neuronal adenylyl cyclase targeting central plasticity for the treatment of chronic pain. Neurotherapeutics 2021; 18: 2129–2129. DOI: 10.1007/s13311-021-01065-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]