Abstract

Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 is able to utilize eugenol (4-allyl-2-methoxyphenol), vanillin (4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde), or protocatechuate as the sole carbon source for growth. Mutants of this strain which were impaired in the catabolism of vanillin but retained the ability to utilize eugenol or protocatechuate were obtained after nitrosoguanidine mutagenesis. One mutant (SK6169) was used as recipient of a Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 genomic library in cosmid pVK100, and phenotypic complementation was achieved with a 5.8-kbp EcoRI fragment (E58). The amino acid sequences deduced from two corresponding open reading frames (ORF) identified on E58 revealed high degrees of homology to pcaG and pcaH, encoding the two subunits of protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase. Three additional ORF most probably encoded a 4-hydroxybenzoate 3-hydroxylase (PobA) and two putative regulatory proteins, which exhibited homology to PcaQ of Agrobacterium tumefaciens and PobR of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, respectively. Since mutant SK6169 was also complemented by a subfragment of E58 that harbored only pcaH, this mutant was most probably lacking a functional β subunit of the protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase. Since this mutant was still able to grow on protocatechuate and lacked protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase and protocatechuate 2,3-dioxygenase, the degradation had to be catalyzed by different enzymes. Two other mutants (SK6184 and SK6190), which were also impaired in the catabolism of vanillin, were not complemented by fragment E58. Since these mutants accumulated 3-carboxy muconolactone during cultivation on eugenol, they most probably exhibited a defect in a step of the catabolic pathway following the ortho cleavage. Moreover, in these mutants cyclization of 3-carboxymuconic acid seems to occur by a syn absolute stereochemical course, which is normally only observed for cis,cis-muconate lactonization in pseudomonads. In conclusion, vanillin is degraded through the ortho-cleavage pathway in Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 whereas protocatechuate could also be metabolized via a different pathway in the mutants.

Vanillin (4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde) is an important aromatic flavor compound that is frequently used in flavored foods and as a fragrance for perfumes. Since vanillin occurs as an intermediate in the catabolism of phenolic stilbenes, eugenol (4-allyl-2-methoxyphenol), ferulate (4-hydroxy-3-methoxycinnamate), and lignin (4, 38, 43, 45), there is widespread interest in producing it from natural raw materials by biotransformation (for an overview, see reference 16).

We are currently investigating biotransformation processes based on the catabolism of eugenol by Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199, which proceeds via ferulate, vanillin, and vanillate (4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoate) (33). In the context of developing a biotechnological process for the production of vanillin, the investigation of mutants of Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 which were impaired in the catabolism of vanillin was of particular interest. The genes encoding vanillin dehydrogenase (vdh) and vanillate-O-demethylase (vanA and vanB) of this strain, which complemented one type of vanillin-negative mutants, were characterized in a recent study (29). In the present study, we characterized additional mutants with defects in the catabolism of vanillin and cloned and molecularly characterized genes which are involved in vanillin degradation in Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The Pseudomonas sp. and Escherichia coli strains and the plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 | Wild type, eugenol positive, ferulate positive, vanillin positive, vanillate positive, protocatechuate positive | DSM 7063 33 |

| Mutants of Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 | ||

| SK6169 | Vanillin negative, eugenol positive, ferulate positive, vanillate positive, protocatechuate positive | This study |

| SK6184 | Vanillin negative, ferulate negative, vanillate negative, eugenol positive protocatechuate positive | This study |

| SK6190 | Vanillin negative, ferulate negative, vanillate negative, eugenol positive, protocatechuate positive | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| XL1-Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi hsdR17 (rK− mK+) supE44relA1, λ−, Lac− [F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15, Tn10(Tet)] | 2 |

| S17-1 | recA; harboring the tra genes of plasmid RP4 in the chromosome, proA thi-1 | 39 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pVK100 | Tcr Kmr, cosmid, broad host range | 22 |

| pHP1014 | Tcr Kmr Cmr, broad host range | 31 |

| pMP92 | Tcr, broad host range | 40 |

| pBluescript KS− | AprlacPOZ′, T7 and T3 promoter | Stratagene, San Diego, Calif. |

| pBluescript SK− | AprlacPOZ′, T7 and T3 promoter | Stratagene, San Diego, Calif. |

| pE207 | pVK100, harboring fragment E230 with the genes vdh, vanA, and vanB | 29 |

Growth of bacteria.

Cells of E. coli were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium (34). Cells of Pseudomonas sp. were grown at 30°C either in a nutrient broth medium (0.8%, wt/vol) or in mineral salts medium (MM) (35) supplemented with carbon sources as indicated in the text. Vanillin, vanillate, ferulate, and protocatechuate were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and added to the medium at final concentrations of 0.1% (wt/vol). Eugenol was directly added to the medium at a final concentration of 0.1% (vol/vol). Tetracycline and kanamycin were used at final concentrations of 12.5 and 50 μg/ml for E. coli or 25 and 300 μg/ml for Pseudomonas sp., respectively.

Nitrosoguanidine mutagenesis.

The nitrosoguanidine mutagenesis of Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 was performed as described previously (29).

Preparation of the soluble fraction of crude extracts.

Cells were washed twice with 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), resuspended in twice the volume of the cell pellet, and disrupted by sonication with a Branson sonifier 250 apparatus (amplitude, 16 μm; 1 min per ml of cell suspension; 20-s bursts). The soluble fraction of the crude extract was obtained by a 1-h centrifugation at 100, 000 × g and 4°C.

Enzyme assays.

Protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase activity was measured spectrophotometrically by monitoring the decrease of absorbancy at 290 nm by the method of Fujisawa and Hayaishi (13). Protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase (4,5-PCD) activity was measured spectrophotometrically by monitoring either the decrease of absorbancy at 250 nm or the increase of absorbancy at 410 nm by the methods described by Ono et al. (26). 2,3-PCD activity was measured spectrophotometrically by monitoring the increase of absorbancy at 350 nm by the method described by Wolgel and Lipscomb (51). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the conversion of 1 μmol of protocatechuate per min. The protein concentrations were determined as described by Lowry et al. (24) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Qualitative and quantitative determination of catabolic intermediates.

Culture supernatants were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on a Nucleosil-100 C18 column without prior extraction as described previously (29).

Isolation and identification of 3-carboxy muconolactone.

From a culture of mutant SK6190 grown in MM with eugenol as the sole carbon source, 80 ml of cell-free supernatant was prepared, which exhibited only one peak with a retention time of 2 min on HPLC analysis. This supernatant was treated by a method described for the isolation of β-ketoadipate (5). The pH of the culture supernatant was adjusted to 2.8 by addition of 2 M phosphoric acid, and the supernatant was then given a 20-min centrifugation at 4°C and 2,772 × g. The supernatant was extracted six times with an equal volume of diethyl ether. The ether phases were combined, the solvent was evaporated, and 44.2 mg of brownish crystals was obtained.

A sample of the isolated substance was introduced via a direct inlet port into a Finnigan MAT 8200 double-focusing high-resolution mass spectrometer. For evaporation, a temperature gradient from 20 to 400°C was applied. The spectrometer was operated in scan mode (electron impact) over a mass range from 25 to 700. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra (1H, 13C, HMQC) were obtained on a Varian VXR 400S spectrometer in CD3OD with tetramethylsilane TMS as the internal standard. Standard pulse sequences supplied by the manufacturer were used. The infrared spectrum (KBr pellet) was measured on a Bio-Rad FTS 40A spectrometer.

Electrophoretic methods.

Proteins were separated under denaturating conditions in 11.5% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gels by the method of Laemmli (23) and stained with Serva Blue R.

Isolation and manipulation of DNA.

Plasmid DNA and DNA restriction fragments were isolated and analyzed by standard methods described in references compiled in a previous study (30).

Transfer of DNA.

Competent cells of E. coli were prepared and transformed by the CaCl2 procedure as described by Hanahan (17). Conjugations of E. coli S17-1 (donor) harboring hybrid plasmids and of Pseudomonas sp. (recipient) were performed on solidified nutrient broth medium as described by Friedrich et al. (12) or by a “minicomplementation method” on solidified MM containing 0.5% (wt/vol) gluconate as the carbon source and 25 μg of tetracycline per ml or 300 μg of kanamycin per ml, as described previously (29).

DNA sequence determination and analysis.

The nucleotide sequences were determined with a 4000L DNA sequencer (LI-COR Inc., Biotechnology Division, Lincoln, Nebr.) and a Thermo Sequenase fluorescence-labelled primer cycle-sequencing kit with 7-deaza-dGTP (Amersham Life Science, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) as specified by the manufacturers. The DNA sequence of E58 was determined by using subcloned fragments as templates and universal and reverse primers. Additional sequences were obtained with synthetic fluorescence-labelled oligonucleotides as primers, employing the primer-hopping strategy (41). Nucleotide and amino acid sequences were analyzed with the Genetics Computer Group sequence analysis software package (GCG Package, version 6.2, June 1990) as described by Devereux et al. (6).

Chemicals.

Restriction endonucleases, T4 DNA ligase, lambda DNA, and enzymes or substrates used in the enzyme assays were obtained from C. F. Boehringer & Soehne (Mannheim, Germany) or from GIBCO/BRL-Bethesda Research Laboratories GmbH (Eggenstein, Germany). Agarose type NA was purchased from Pharmacia-LKB (Uppsala, Sweden). Radioisotopes were from Amersham/Buchler (Braunschweig, Germany). Synthetic oligonucleotides were purchased from MWG-Biotech (Ebersberg, Germany). All other chemicals were from Haarmann & Reimer (Holzminden, Germany), E. Merck AG (Darmstadt, Germany), Fluka Chemie (Buchs, Switzerland), Serva Feinbiochemica (Heidelberg, Germany), or Sigma Chemie (Deisenhofen, Germany).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide and amino acid sequence data reported in this paper have been submitted to the EMBL, GenBank, and DDBJ nucleotide sequence databases and are listed under accession no. Y18527.

RESULTS

Cloning of the genes involved in the vanillin degradation pathway.

Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 is able to grow on vanillin as the sole carbon source. To identify the genes which are essential for vanillin degradation, nitrosoguanidine-induced mutants were isolated and screened on solidified mineral medium containing vanillin or protocatechuate as the sole carbon source. Three independent mutants (SK6169, SK6184, and SK6190) which had lost their ability to grow on vanillin but were still able to grow on protocatechuate were identified. These mutants were not phenotypically complemented after conjugational reception of plasmid pE207 (29), encoding vanillin dehydrogenase and vanillate-O-demethylase. Since vanillin is converted via vanillate to protocatechuate in the wild type, the phenotype of these mutants was obscure.

One of the mutants (SK6169) was chosen as the recipient for a genomic library of Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 constructed in cosmid pVK100. In total, 1,440 transductants of E. coli S17-1 were selected on LB-tetracycline agar plates, and the hybrid cosmids of these strains were transferred to the “vanillin-negative” mutant SK6169 by conjugation. Two transconjugants which were complemented by the received hybrid cosmids and which grew again on vanillin were isolated. The corresponding hybrid cosmids pV372 and pV801, which occurred in these transconjugants, harbored a 5.8-kbp EcoRI fragment (E58) in addition to other EcoRI fragments of different sizes.

Fragment E58 was isolated and ligated to EcoRI-digested pHP1014 DNA. After transformation of E. coli S17-1, tetracycline-resistant and chloramphenicol-sensitive transformants harboring fragment E58 in pHP1014 were used as donors in conjugation experiments with mutant SK6169 as the recipient. All obtained transconjugants were able to grow again on vanillin. E58 was also cloned in the vector pBluescript SK−, resulting in plasmids pSKE58-1 and pSKE58-2, which harbor fragment E58 in opposite directions. A physical map of this fragment was obtained by digestion with different restriction endonucleases (Fig. 1).

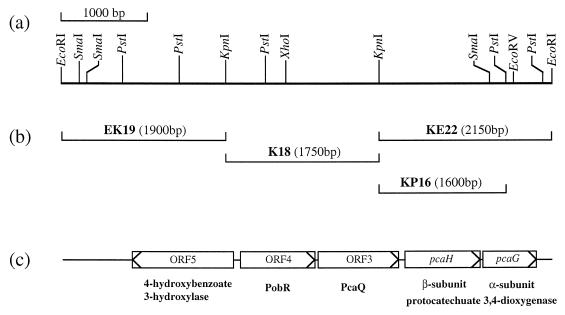

FIG. 1.

Organization of the pcaH and pcaG genes of Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199. (a) Physical map of fragment E58. (b) Subfragments relevant for complementation and heterologous expression studies. (c) Identified genes and ORFs of a putative 4-hydroxybenzoate 3-hydroxylase (ORF5), a putative PobR (ORF4), a putative PcaQ (ORF3), and 3,4-PCD (pcaHG).

Subcloning of pcaH and pcaG.

Plasmids pSKE58-1 and pSKE58-2 were digested with KpnI, and the resulting 1.9-kbp (EK19), 1.75-kbp (K18), and 2.15-kbp (KE22) KpnI fragments were cloned in pMP92. After conjugative transfer of the resulting plasmids from corresponding E. coli S17-1 strains to the “vanillin-negative” mutant SK6169, complementation was achieved only with fragment KE22. By subcloning of the PstI fragments of KE22 in pMP92 and subsequent conjugative transfer to the mutant SK6169, the complementing region was assigned to a 1.6-kbp KpnI-PstI (KP16) subfragment of KE22 (Fig. 1).

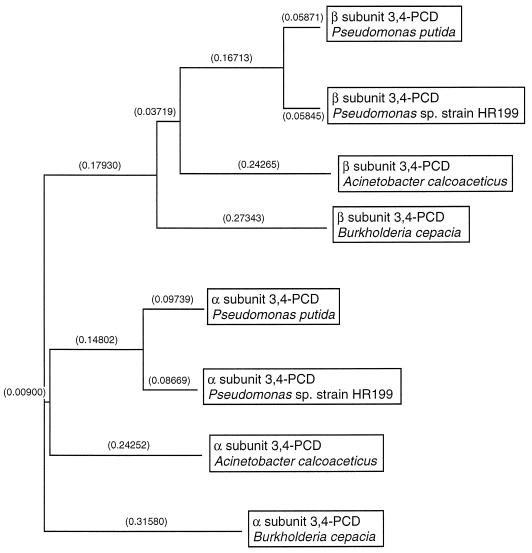

Nucleotide sequence of fragment E58.

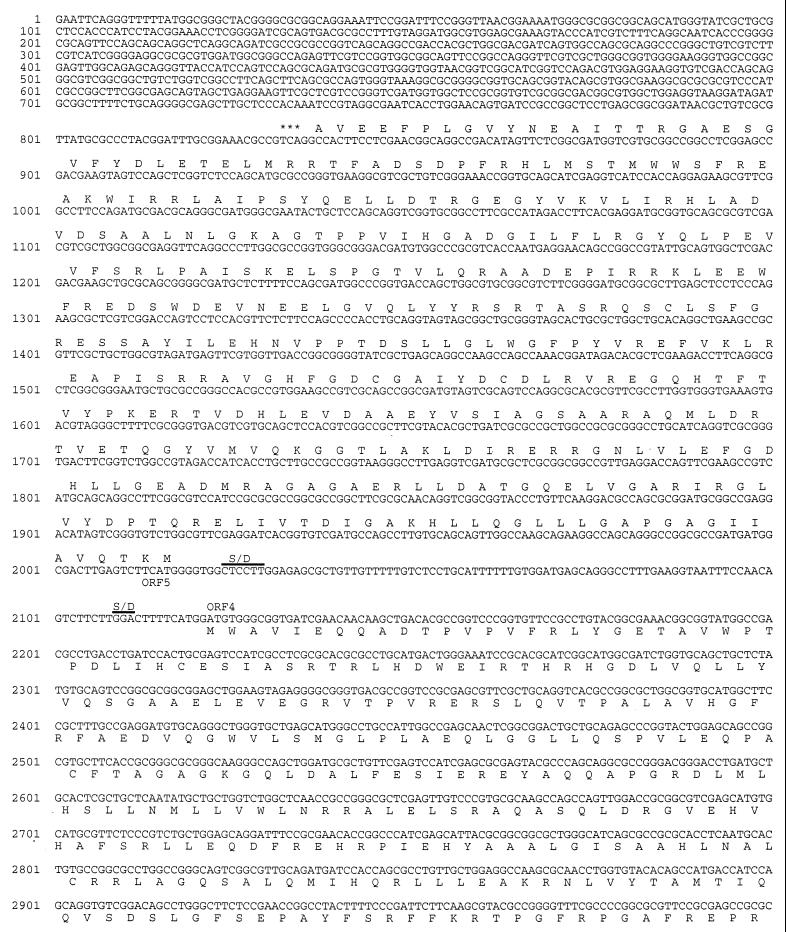

The nucleotide sequence of the entire E58 fragment was determined (Fig. 2). An open reading frame (ORF) of 720 bp (ORF1), whose putative translational product exhibited significant homology to β subunits of 3,4-PCD from various other bacteria (Fig. 3) and which was therefore referred to as pcaH, was identified on fragment KP16. Thus, mutant SK6169 most probably lacked a functional β subunit of 3,4-PCD. At 12 bp downstream of the translational stop codon of pcaH at position 4789 (Fig. 2), the ATG start codon of a second ORF of 606 bp (ORF2) was identified, which was referred to as pcaG since its putative translational product exhibited significant homology to α subunits of 3,4-PCD (Fig. 3). Typical Shine-Dalgarno sequences, AGGAG or AGGAGG, preceded the ATG-start codons of pcaH and pcaG at distances of 6 or 7 nucleotides, respectively. An inverted repeat, which may represent a factor-dependent transcriptional terminator, was identified 20 bp downstream from the translational stop codon of pcaG (Fig. 2). The free energy of this structure is approximately −70.2 kJ/mol according to Tinoco et al. (44).

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence of fragment E58. Amino acids deduced from the nucleotide sequence are specified by standard one-letter abbreviations. The putative ribosome-binding sites are overlined and indicated by S/D. The position of the hairpinlike structure downstream of pcaG is indicated by arrows.

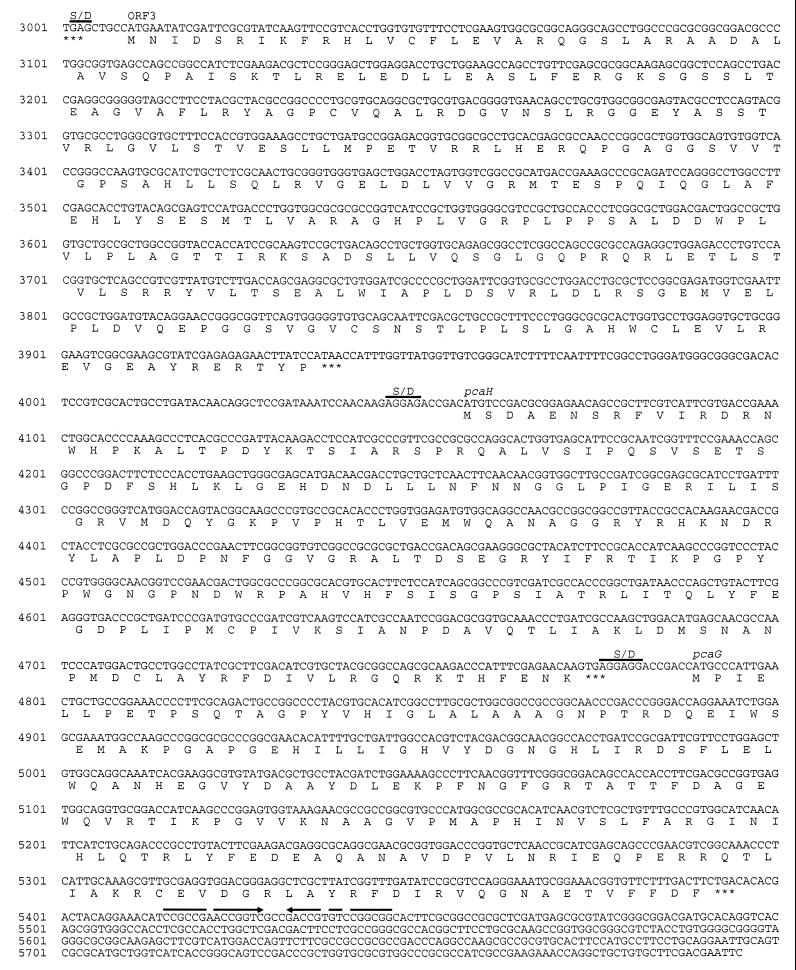

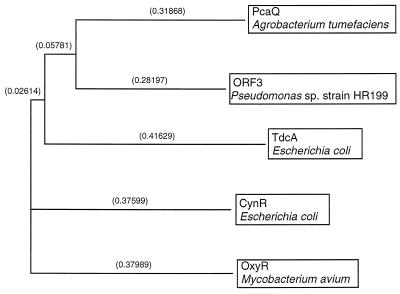

FIG. 3.

Relationship of Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 3,4-PCD and 3,4-PCDs from other sources. The dendrogram was constructed with the CLUSTAL program from pairwise similarity scores generated by the method of Wilbur and Lipman (49) with the following parameters: k-tuple length, 1; gap penalty, 3; number of diagonals, 5; diagonal window size, 5; gap-opening penalty, 10; gap extension penalty, 0.10; protein weight matrix, blosum. Relatedness is represented by the branch length (distances are given as 10−2 percent divergence in parentheses). The amino acid sequences of the α and β subunits of 3,4-PCD from P. putida (pironly:DAPSAA; pironly:DAPSBA) (11), Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (Swissprot:PCXA_ACICA; Swissprot:PCXB_ACICA) (18), and Burkholderia cepacia (Swissprot:PCXA_BURCE; Swissprot:PCXB_BURCE) (53) were compared with the α and β subunits of 3,4-PCD from Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 deduced from pcaG and pcaH.

The G+C contents of pcaG and pcaH were 62.0 and 63.9 mol%, respectively, and the G+C contents for the different codon positions corresponded well to the theoretical values calculated by the method of Bibb et al. (1). In addition, the codon usages of pcaH and pcaG were very similar to the codon usage for the vdh, vanA, and vanB genes of this bacterium (29). These data indicated that pcaH and pcaG represented coding regions and that both genes constitute an operon in Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199. At 117 bp upstream of pcaH, 930-bp ORF (ORF3) was identified, whose putative translational product exhibited significant homology to different regulatory proteins of the LysR family (Fig. 4). The highest homology (40.7% identical amino acids) was to the transcriptional activator PcaQ of the pca operon from Agrobacterium tumefaciens (27). Also, the putative translational start codon (ATG) of ORF3 at position 3010 (Fig. 2) was preceded by a putative Shine-Dalgarno sequence, and the sequence showed all the features typical of a coding region.

FIG. 4.

Relationship of the amino acid sequence deduced from ORF3 from Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 and four representative transcriptional activator proteins of the LysR family from different sources. The program and parameters for the construction of the dendrogram were the same as for Fig. 3. The amino acid sequences of PcaQ from A. tumefaciens (Swissprot:PCAQ_AGRTU) (27), of TdcA from E. coli (Swissprot:TDCA_ECOLI) (15), of CynR from E. coli (Swissprot:CYNR_ECOLI) (42), and of OxyR from Mycobacterium avium (Swissprot:OXYR_MYCAV) (37) were compared with the amino acid sequence of Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 deduced from ORF3.

Deduced properties of the pcaH and pcaG gene products.

The relative molecular masses of the α and β subunits of 3,4-PCD, calculated from the amino acid sequence deduced from pcaG and pcaH, were 22,364 and 26,800 Da, respectively. These values corresponded well to those reported for other 3,4-PCDs, e.g., 22,300 and 26,600 Da for the 3,4-PCD subunits from P. putida (11).

Putative functions of the pcaH and pcaG gene products.

The amino acid sequences deduced from pcaG and pcaH were compared with those collected in GenBank. The highest homology was achieved to the 3,4-PCD of P. putida (81 and 88% identical amino acids for the α and β subunits, respectively). As reported for other 3,4-PCDs, there was a high degree of homology between the α and β subunit of this enzyme from Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 (36.2% identical amino acids), which was also obvious at the DNA level, where the identity of the nucleotide sequences of pcaG and pcaH was 58%. The relationship of the α and β subunit of 3,4-PCD from Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 to 3,4-PCDs from other sources is shown in Fig. 3.

Expression of pcaHG from Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 in the “vanillin-negative” mutant SK6169, and heterologous expression in E. coli.

The 2.2-kbp KpnI-EcoRI subfragment (KE22) of E58 (Fig. 1) was cloned in the vector pMP92, which was then conjugatively transferred from corresponding E. coli S17-1 strains to the mutant SK6169. This mutant was not able to grow on solidified medium with vanillin as the carbon source and lacked 3,4-PCD activity. Plasmid pMPKE22 restored the ability to grow on vanillin in the corresponding transconjugants. Moreover, these transconjugants exhibited 3,4-PCD activities comparable to the wild type (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Expression of the pcaHG gene cluster of Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 in the vanillin-negative mutant SK6169 and in E. colia

| Strain | Plasmid (inducer)b | Sp act of 3,4-PCD (U/mg)c |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 | 0.26 | |

| Pseudomonas mutant SK6169 | <0.01 | |

| Pseudomonas mutant SK6169 | pMPKE22 | 0.18 |

| E. coli S17-1 | pMP92 | <0.01 |

| E. coli S17-1 | pMPKE22 | <0.01 |

| E. coli XL1-Blue | pBluescript SK− (+ IPTG) | <0.01 |

| E. coli XL1-Blue | pBluescript KS− (+ IPTG) | <0.01 |

| E. coli XL1-Blue | pKSKE22 (− IPTG) | 0.05 |

| E. coli XL1-Blue | pKSKE22 (+ IPTG) | 0.28 |

| E. coli XL1-Blue | pSKKE22 (− IPTG) | <0.01 |

| E. coli XL1-Blue | pSKKE22 (+ IPTG) | <0.01 |

Cells of Pseudomonas strains were grown to the late exponential phase at 30°C in MM containing eugenol as a carbon source and harvested. Cells of recombinant strains of E. coli were grown for 12 h at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium.

To induce expression from the lacZ promoter, the recombinant strains of E. coli harboring pBluescript derivatives were cultivated in the presence of 1 mM IPTG.

The 3,4-PCD activities were determined in soluble extracts at 30°C by the method of Fujisawa and Hayaishi (13) as described in Materials and Methods. Specific activities are given as units per milligram of protein.

The pcaHG genes were also heterologously expressed in E. coli. Fragment KE22 was cloned in the vectors pBluescript SK− and pBluescript KS−. Hybrid plasmid pKSKE22, which harbors fragment KE22 with the pcaHG genes colinear to and downstream of the lacZ promoter of pBluescript KS− DNA, conferred 3,4-PCD activity to recombinant strains of E. coli XL1-Blue (Table 2). After growth of this strain in the presence of the inducer IPTG, a 3,4-PCD activity of 0.28 U/mg of protein was obtained. If KE22 was ligated to pBluescript SK− DNA with pcaHG antilinear to the lacZ promoter, the recombinant strains of E. coli XL1-Blue exhibited no 3,4-PCD activity (Table 2). This result indicated that transcription of pcaHG in E. coli occurred only from the lacZ promoter and not from a promoter upstream of pcaHG, which might be used by the RNA polymerase holoenzyme of Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199.

Identification of ORFs exhibiting homology to pobA and pobR.

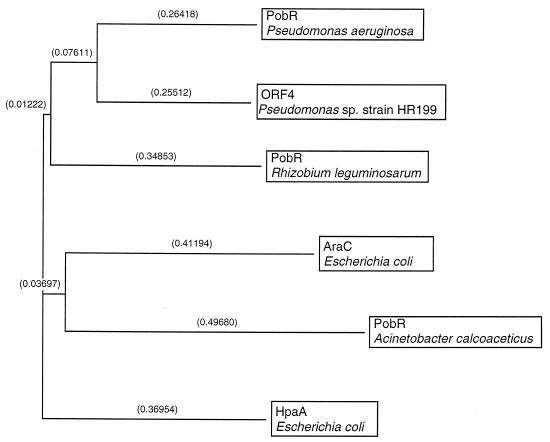

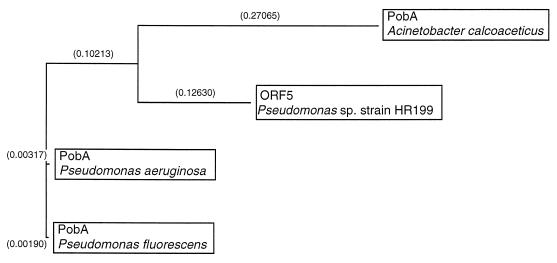

Upstream of ORF3, two additional ORFs of 882 and 1,185 bp were identified (Fig. 1), which were preceded by putative Shine-Dalgarno sequences (Fig. 2) and showed all the features typical of coding regions in Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199. Comparison of the amino acid sequences deduced from ORF4 and ORF5 revealed extended homologies to PobR from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (49.3% identical amino acids) (Fig. 5) and to 4-hydroxybenzoate 3-hydroxylases from different sources (Fig. 6), respectively.

FIG. 5.

Relationship of the amino acid sequence deduced from ORF4 from Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 and four representative regulatory proteins from different sources. The program and parameters for the construction of the dendrogram were the same as for Fig. 3. The amino acid sequences of PobR from P. aeruginosa (pironly:S41382) (10), of PobR from Rhizobium leguminosarum (U40388) (52), of HpaA from E. coli (pironly:A55349) (32), of AraC from E. coli (Swissprot:ARAC_ECOLI) (48), and of PobR from Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (L13114) (8) were compared with the amino acid sequence of Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 deduced from ORF4.

FIG. 6.

Relationship of the amino acid sequence deduced from ORF5 from Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 with 4-hydroxybenzoate 3-hydroxylases (PobA) from other sources. The program and parameters for the construction of the dendrogram were the same as for Fig. 3. The amino acid sequences of PobA from P. aeruginosa (Swissprot:PHHY_PSEAE) (9), P. fluorescens (Swissprot:PHHY_PSEFL) (46), and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (Swissprot:PHHY_ACICA) (7) were compared with the amino acid sequence of Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 deduced from ORF5.

Analysis of mutant SK6169, which exhibited a defective 3,4-PCD but was still able to grow on protocatechuate.

The results of the genetic analysis of mutant SK6169 revealed a defect in the β subunit of 3,4-PCD. In consequence, this mutant lacked 3,4-PCD activity (Table 2). Nevertheless, it was able to grow on eugenol, ferulate, vanillate, or protocatechuate as the sole carbon source. To investigate this obscure phenotype in more detail, the mutant was grown in the presence of vanillin, protocatechuate, or vanillin plus gluconate in liquid MM. These investigations revealed that mutant SK6169 grew as well as the wild type on vanillin plus gluconate and was still able to grow on vanillin without an additional carbon source. However, in comparison to the wild type, the mutant grew only after a long lag phase of about 20 h. In contrast to the analysis on MM agar plates, the growth of the mutant in liquid MM with protocatechuate as the sole carbon source was reduced compared to the wild type. As revealed by HPLC analysis of culture supernatants, vanillin was converted to vanillate and protocatechuate by this mutant, which was further metabolized. In comparison to the wild type, the occurrence of these intermediates was retarded. To exclude the appearance of revertants, aliquots of the cultures were spread on vanillin- or protocatechuate-containing MM agar plates, respectively. No growth of revertants on vanillin agar plates could be observed, and there was no difference in the growth of the wild type and the mutant on protocatechuate-containing agar plates.

Crude extracts obtained from the cells of the aforementioned cultures were investigated for 3,4-PCD, 4,5-PCD, and 2,3-PCD activities. None of these activities were detectable in the extracts of the mutant, whereas extracts of the wild type exhibited 3,4-PCD activity (Table 2). The way in which mutant SK6169 metabolized protocatechuate remained unknown.

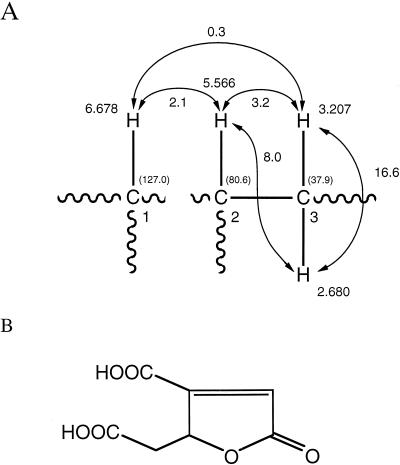

Analysis of mutants SK6184 and SK6190, which were also impaired in the catabolism of vanillin.

During the nitrosoguanidine mutagenesis, mutants SK6184 and SK6190, which had lost their ability to grow on vanillin, vanillate, and ferulate but were still able to grow on eugenol or protocatechuate, were isolated. These mutants were not complemented by the hybrid cosmids pV372 and pV801 after conjugative reception. When these mutants were cultivated in MM with eugenol, vanillin, or protocatechuate as the sole carbon source, the substrates were completely converted to an unknown substance. To identify this product, we isolated it from the culture supernatant of mutant SK6190 grown in MM with eugenol. The light brownish crystals we obtained exhibited a blurred melting point of 114 to 150°C. The isolated substance was soluble in H2O, methanol, ethyl acetate, and diethylether. Its mass spectrum showed a molecular ion at m/z 186. From these results along with the data obtained from 1H NMR (four protons) and 13C NMR (seven carbon atoms) spectra and the infrared spectrum (OH group[s], three carbonyl bands), the molecular formula was found to be C7H6O6. The 1H NMR spectrum of the substance showed an ABXZ spin system (JAB = 16.6 Hz, JAX = 8.0 Hz, JBX = 3.2 Hz) at 2.680, 3.207, and 5.566 ppm, with an allylic coupling (2.1 Hz) between the X proton and the olefinic proton at 6.678 ppm. These findings established the structure fragments shown in Fig. 7. The 13C NMR spectrum showed seven signals at 173.1, 172.6, 163.7, 160.1, 127.0 (⩵CH) 80.6 (CH), and 37.9 (CH2) ppm. Correlations between 1H and 13C extracted from the HMQC spectrum are shown in Fig. 7. Because the protons at C-3 are diastereotopic, an asymmetrically substituted carbon atom must be in the direct neighborhood. C-1 must be part of a double bond with a quaternary carbon atom (160.1 ppm) as a partner. H-1 must be in the β-position to a carbonyl function because of its high shift value. The shift value of 80.6 ppm for C-2 indicates that it must be bonded to an oxygen atom. From these data, the chemical structure of the isolated substance could be assigned to 3-carboxy muconolactone (Fig. 7). Furthermore, the obtained spectral data are in good agreement with the values published by Kirby et al. (21).

FIG. 7.

Identification of the substance accumulated by mutants SK6184 and SK6190 during growth on eugenol. (A) Structure fragments established by NMR spectroscopy: 1H-NMR data (CD3OD), δ [ppm], J [Hz]. 13C NMR shift values (ppm) are shown in parentheses. (B) Chemical structure of 3-carboxy muconolactone.

Thus, the mutants SK6184 and SK6190 accumulated 3-carboxy muconolactone during growth on eugenol, which is most probably due to a lactonization of 3-carboxy-cis,cis-muconate by a syn absolute stereochemical course.

DISCUSSION

A 5.8-kbp EcoRI fragment cloned from genomic DNA of Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 was found to encode proteins which are essentially involved in the degradation of vanillin. A “vanillin-negative” mutant which lacked 3,4-PCD activity was phenotypically complemented by the structural gene pcaH, encoding the β subunit of 3,4-PCD. The structural gene of the corresponding α subunit, pcaG, was localized downstream of pcaH. The amino acid sequences deduced from pcaH and pcaG showed extended homology to the 3,4-PCD from P. putida (11). pcaHG were expressed in E. coli driven by the lac promoter of pBluescript SK−. The 3,4-PCD activity was 13-fold higher than that obtained by the expression of pcaHG of P. putida in E. coli (11). Since the G+C contents and the codon bias of the pcaHG genes of Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 and P. putida were very similar, it is unlikely that the weak expression of the P. putida genes in E. coli is due to these properties, as concluded by Frazee et al. (11).

Upstream of pcaHG was an ORF which had the same orientation and whose deduced amino acid sequence exhibited strong homology to the transcriptional activator protein PcaQ from Agrobacterium tumefaciens (27). The region of highest homology was located in the N-terminal region as described by Viale et al. (47) for transcriptional activator proteins belonging to the LysR family, comprising the helix-turn-helix motif (20) for DNA binding.

In the immediate neighborhood of the pca genes were found two ORF that exhibited high homologies to the pob genes responsible for p-hydroxybenzoate metabolism. The first ORF exhibited high homology to the PobR regulator protein of A. tumefaciens (28), which belongs to transcriptional regulator proteins of the XylS/AraC type (14). As also observed for the PobR regulator protein of A. tumefaciens (28), no homology was obtained with the transcriptional regulator proteins of the so-called PobR subfamily (8), which refers to PobR of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. The amino acid sequence of the second ORF exhibited 77% identity to PobA from P. aeruginosa and P. fluorescens and 61% identity to PobA from Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and most probably resembles the typical NADPH-dependent 4-hydroxybenzoate 3-hydroxylase of the P. aeruginosa type (36).

In the wild-type Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199, vanillin is catabolized by oxidation to vanillate, which is subsequently demethylated to yield protocatechuate (29). Since cells grown on these substrates exhibited 3,4-PCD activity, the catabolism most probably proceeds via the ortho-cleavage pathway in this bacterium. The “vanillin-negative” mutant SK6169 exhibited a defect in the β subunit of 3,4-PCD, thus lacking the corresponding enzyme activity. Nevertheless, this mutant was able to grow on protocatechuate. Since cells grown on this substrate exhibited neither 3,4-PCD, 4,5-PCD, nor 2,3-PCD activities, mutant SK6169 must have another mechanism for protocatechuate catabolism, which might be due to activities of other ring-cleaving enzymes which were not covered by the applied spectrophotometric assays. Two other “vanillin-negative” mutants accumulated 3-carboxy muconolactone in the medium during growth on eugenol. The occurrence of this intermediate seems to be due to a lactonization of 3-carboxy-cis,cis-muconate by a syn absolute stereochemical course. This kind of cyclization is observed only in fungi (25), whereas in bacteria the lactonization catalyzed by 3-carboxy-cis,cis-muconate lactonizing enzyme (CMLE) causes an anti addition (3, 50), resulting in 4-carboxy muconolactone as the product. In contrast, the lactonization of cis,cis-muconate, catalysed by the cis,cis-muconate lactonizing enzyme (MLE) proceeds by a syn addition (19). The accumulation of 3-carboxy muconolactone by the aforementioned mutants could be a hint that Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 possesses an unusual “syn-CMLE” and that the mutants exhibited a defect in a following step of the degradation pathway. Another explanation would be an alteration of the CMLE gene by mutation, changing the “anti-CMLE” to a “syn-CMLE” in the mutants, resulting in the accumulation of the carboxy muconolactone with nonstandard regiochemical properties. Since the “vanillin-negative” phenotypes of the investigated mutants were due to defects in 3,4-PCD or in enzymes of the protocatechuate branch of the ortho-cleavage pathway, vanillin is degraded via this pathway in the wild type.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

H.P. and A.S. are indebted to Haarmann & Reimer GmbH for providing a collaborative research grant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bibb M J, Findlay P R, Johnson M W. The relationship between base composition and codon usage in bacterial genes and its use for the simple and reliable identification of protein-coding sequences. Gene. 1984;30:157–166. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bullock W O, Fernandez J M, Stuart J M. XL1-Blue: a high efficiency plasmid transforming recA Escherichia coli strain with beta-galactosidase selection. BioTechniques. 1987;5:376–379. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chari R V J, Whitman C P, Kozarich J W, Ngai K-L, Ornston L N. Absolute stereochemical course of the 3-carboxymuconate cycloisomerases from Pseudomonas putida and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus: analysis and implications. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:5514–5519. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen C L, Chang H M, Kirk T. Aromatic acids produced during degradation of lignin in spruce wood by Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Holzforschung. 1982;36:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darrah A, Cain R B. A convenient biological method for preparing β-ketoadipic acid. LABP. 1969;16:989–996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiMarco A A, Averhoff B, Kim E E, Ornston L N. Evolutionary divergence of pobA, the structural gene encoding p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase in an Acinetobacter calcoaceticus strain, well-suited for genetic analysis. Gene. 1993;125:25–33. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90741-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiMarco A A, Averhoff B, Ornston L N. Identification of the transcriptional activator pobR and characterization of ist role in the expression of pobA, the structural gene for p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4499–4506. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.14.4499-4506.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Entsch B, Nan Y, Weaich K, Scott K F. Sequence and organization of pobA, the gene coding for p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase, an inducible enzyme from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene. 1988;71:279–291. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Entsch, B., L. Squire, and R. E. Wicks. Unpublished results.

- 11.Frazee R W, Livingston D M, LaPorte D C, Lipscomb J D. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the Pseudomonas putida protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase genes. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6194–6202. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6194-6202.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedrich B, Hogrefe C, Schlegel H G. Naturally occurring genetic transfer of hydrogen-oxidizing ability between strains of Alcaligenes eutrophus. J Bacteriol. 1981;147:198–205. doi: 10.1128/jb.147.1.198-205.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujisawa H, Hayaishi O. Protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase: crystallization and characterization. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:2673–2681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallegos M-T, Michán C, Ramos J L. The XylS/AraC family of regulators. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:807–810. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.4.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goss T J, Datta P. Molecular cloning and expression of the biodegradative threonine dehydratase gene (tdc) of Escherichia coli K12. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;201:308–314. doi: 10.1007/BF00425676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagedorn S, Kaphammer B. Microbial biocatalysis in the generation of flavor and fragrance chemicals. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:773–800. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.004013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartnett C, Neidle E L, Ngai K-L, Ornston L N. DNA sequences of genes encoding Acinetobacter calcoaceticus protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase: evidence indicating shuffling of genes and of DNA sequences within genes during their evolutionary divergence. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:956–966. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.956-966.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helin S, Kahn P C, Guha B L, Mallows D G, Goldman A. The refined X-ray structure of muconate lactonizing enzyme from Pseudomonas putida PRS2000 at 1.85 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:918–941. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henikoff S, Haughn G W, Calvo J M, Wallace J C. A large family of bacterial activator proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6602–6606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirby G W, O’Loughlin G J, Robins D J. The stereochemistry of the enzymic cyclisation of 3-carboxymuconic acid to 3-carboxymuconolactone. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1975;1975:402–403. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knauf V C, Nester E W. Wide host range cloning vectors: a cosmid clone bank of an Agrobacterium Ti plasmid. Plasmid. 1982;8:45–54. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(82)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazur P, Henzel W J, Mattoo S, Kozarich J W. 3-Carboxy-cis,cis-muconate lactonizing enzyme from Neurospora crassa: an alternate cycloisomerase motif. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1718–1728. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1718-1728.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ono K, Nozaki M, Hayaishi O. Purification and some properties of protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970;220:224–238. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(70)90008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parke D. Characterization of PcaQ, a LysR-type transcriptional activator required for catabolism of phenolic compounds, from Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:266–272. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.266-272.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parke D. Acquisition, reorganization, and merger of genes: novel management of the β-ketoadipate pathway in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;146:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Priefert H, Rabenhorst J, Steinbüchel A. Molecular characterization of genes of Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 involved in bioconversion of vanillin to protocatechuate. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2595–2607. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2595-2607.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Priefert H, Hein S, Krüger N, Zeh K, Schmidt B, Steinbüchel A. Identification and molecular characterization of the Alcaligenes eutrophus H16 aco operon genes involved in acetoin catabolism. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4056–4071. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.4056-4071.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pries A, Priefert H, Krüger N, Steinbüchel A. Identification and characterization of two Alcaligenes eutrophus gene loci relevant to the poly(β-hydroxybutyric acid)-leaky phenotype which exhibit homology to ptsH and ptsI of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5843–5853. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.18.5843-5853.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prieto M A, Garcia J L. Molecular characterization of 4-hydroxy-phenylacetate 3-hydroxylase of Escherichia coli. A two-protein component enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22823–22829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rabenhorst J. Production of methoxyphenol type natural aroma chemicals by biotransformation of eugenol with a new Pseudomonas sp. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1996;46:470–474. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlegel H G, Kaltwasser H, Gottschalk G. Ein Submersverfahren zur Kultur wasserstoffoxidierender Bakterien: Wachstumsphysiologische Untersuchungen. Arch Mikrobiol. 1961;38:209–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seibold B, Matthes M, Eppink M H M, Lingens F, Van Berkel W J H, Müller R. 4-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase from Pseudomonas sp. CBS3. Purification, characterization, gene cloning, sequence analysis and assignment of structural features determining the coenzyme specificity. Eur J Biochem. 1996;239:469–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0469u.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sherman D R, Sabo P J, Hickey M J, Arain T M, Mahairas G G, Yuan Y, Barry C E, Stover C K. Disparate responses to oxidative stress in saprophytic and pathogenic mycobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6625–6629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shiotsu Y, Samejima M, Habu N, Yoshimoto T. Enzymatic conversion of stilbenes from the inner back of Picea glehnii into aromatic aldehydes. Mukuzai Gakkaishi. 1989;35:826–831. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spaink H P, Okker R J H, Wijffelman C A, Pees E, Lugtenberg J J. Promoters in the nodulation region of the Rhizobium leguminosarum Sym plasmid pRL1JI. Plant Mol Biol. 1987;9:27–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00017984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strauss E C, Kobori J A, Siu G, Hood L E. Specific-primer-directed DNA sequencing. Anal Biochem. 1986;154:353–360. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sung Y-C, Fuchs J A. The Escherichia coli K-12 cyn operon is positively regulated by a member of the LysR family. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3645–3650. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3645-3650.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tadasa K, Kayahara H. Initial steps of eugenol degradation pathway of a microorganism. Agric Biol Chem. 1983;47:2639–2640. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tinoco I, Borer P N, Dengler B, Levine M D, Uhlenbeck O C, Crothers D M, Gralla J. Improved estimation of secondary structure in ribonucleic acids. Nat (London) New Biol. 1973;246:40–41. doi: 10.1038/newbio246040a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toms A, Wood J M. The degradation of trans-ferulic acid by Pseudomonas acidovorans. Biochemistry. 1970;9:337–343. doi: 10.1021/bi00804a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Berkel W, Westphal A, Eschrich K, Eppink M, DeKok A. Substitution of Arg 214 at the substrate-binding site of p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase from Pseudomonas fluorescens. Eur J Biochem. 1992;210:411–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Viale A M, Kobayashi H, Akazawa T, Henikoff S. rcbR, a gene coding for a member of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators, is located upstream of the expressed set of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase genes in the photosynthetic bacterium Chromatium vinosum. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5224–5229. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.16.5224-5229.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wallace R G, Lee N, Fowler A V. The araC gene of Escherichia coli: transcriptional and translational start-points and complete nucleotide sequence. Gene. 1980;12:179–190. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(80)90100-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilbur W J, Lipman D J. Rapid similarity searches of nucleic acid and protein data banks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:726–730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.3.726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams S E, Woolridge E M, Ransom S C, Landro J A, Babbitt P C, Kozarich J W. 3-Carboxy-cis,cis-muconate lactonizing enzyme from Pseudomonas putida is homologous to the class II fumarase family: a new reaction in the evolution of a mechanistic motif. Biochemistry. 1992;31:9768–9776. doi: 10.1021/bi00155a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolgel S A, Lipscomb J D. Protocatechuate 2,3-dioxygenase from Bacillus macerans. Methods Enzymol. 1990;188:95–101. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)88018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wong, C. M., M. J. Dilworth, and A. R. Glenn. 4-Hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase (pobA) is positively regulated by pobR in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciael. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Zylstra G J, Olsen R H, Ballou D P. Genetic organization and sequence of the Pseudomonas cepacia genes for the α and β subunits of protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5915–5921. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.5915-5921.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]