ABSTRACT

The downregulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa flagellar motility is a key event in biofilm formation, host colonization, and the formation of microbial communities, but the external factors that repress motility are not well understood. Here, we report that on soft agar, swarming motility can be repressed by cells that are nonmotile due to the absence of a flagellum or flagellar rotation. Mutants that lack either flagellum biosynthesis or rotation, when present at as little as 5% of the total population, suppressed swarming of wild-type cells. Non-swarming cells required functional type IV pili and the ability to produce Pel exopolysaccharide to suppress swarming by the flagellated wild type. Flagellated cells required only type IV pili, but not Pel production, for their swarming to be repressed by non-flagellated cells. We hypothesize that interactions between motile and nonmotile cells may enhance the formation of sessile communities, including those involving multiple genotypes, phenotypically diverse cells, and perhaps other species.

IMPORTANCE Our study shows that, under the conditions tested, a small population of non-swarming cells can impact the motility behavior of a larger population. The interactions that lead to the suppression of swarming motility require type IV pili and a secreted polysaccharide, two factors with known roles in biofilm formation. These data suggest that interactions between motile and nonmotile cells may enhance the transition to sessile growth in populations and promote interactions between cells with different genotypes.

KEYWORDS: swarming, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, motility, type IV pili, Pel, microbe-microbe interaction

INTRODUCTION

Microbial localization through processes other than cell division are critical for the formation of spatially structured populations and communities. Thus, motility and its regulation by diverse chemical and physical stimuli is a major driver of intraspecies and interspecies microbial interactions (1, 2). Previously, we found that exogenous ethanol, a common product secreted by many microbes, markedly reduced Pseudomonas aeruginosa swimming and swarming motilities at the population level, but only decreased the motile fraction of cells in the population by 16% when individual cells were examined (3). Prompted by this finding, we sought to determine the impact of a subpopulation of nonmotile cells on the motility of the larger motile P. aeruginosa population.

During P. aeruginosa biofilm formation, motile cells are recruited to microcolonies of sessile cells via a combination of processes which may differ between strains with distinct early biofilm-forming strategies (4, 5) or in response to different experimental conditions. For P. aeruginosa strain PA14, retractile type IV pili (T4P) participate in surface sensing, which results in the upregulation of cAMP and the subsequent induction of cyclic-di-GMP (6–8); flagellar motility is then downregulated in order to facilitate surface attachment (6, 7, 9, 10) followed by Pel exopolysaccharide matrix production (11), which can connect cells to one another (10, 12). Both matrix production and T4P function have been shown to participate in motility repression (10, 12–14), suggesting that matrix materials may mediate physical interactions between neighboring cells. T4P also mediate cell-cell interactions in swarms (15).

Boyle et al. (16) previously showed that a ΔflgK mutant lacking a flagellum repressed swarming (i.e., decreased the swarm radius) when present in excess (83%) compared to the flagellated wild type (WT; 17%). In support of the observation that a non-motile subpopulation can suppress population-wide swarming, our previously published findings (3) showed that while WT strain PA14 was able to swim in soft agar, an average of only 38% of flagellated cells were motile at any given time. Furthermore, we showed that ethanol reduced the motile fraction of the P. aeruginosa population from 38% to 22%. Ethanol also strongly repressed swarming, and this repression required some T4P components (3). Thus, we proposed that a reduction in the motile fraction of cells was sufficient to repress swarming by the entire population, and sought to explore the interactions between motile and non-motile cells in the context of swarms.

In this study, we show that non-motile cells lacking a flagellum, when added to a population at 5% to 75% of the total inoculum, resulted in repression of swarming by WT cells. To repress flagellar motility, non-motile cells required the ability to produce Pel polysaccharide, and both motile and non-motile cells required functional T4P for this interaction. These data have implications for factors which contribute to population-level behaviors and intra- and interspecies interactions. Conditions that promote cell-cell interactions may be relevant in situations where non-motile and motile cells can be found together, such as in cystic fibrosis (CF)-associated lung infections (17–19), wounds (20), and ear infections (18).

RESULTS

The absence of flagellar motility in a subpopulation of cells is sufficient to suppress wild-type P. aeruginosa swarming.

To explore the effects of a subpopulation of non-motile cells on swarming motility, mixtures containing different proportions of flagellated P. aeruginosa strain PA14 (WT) cells and non-flagellated ΔflgK mutant cells lacking the flagellar hook protein were grown on 0.5% M8 agar, which supports swarming motility by the WT strain. The percentage of ΔflgK mutant cells ranged from 5% to 75% in these mixtures, and single strains were included as controls. As expected, cultures with 100% WT swarmed readily, while cultures with 100% ΔflgK showed no swarming (Fig. 1A). We found that swarming motility was completely repressed by the addition of 5 to 75% ΔflgK cells under the conditions tested (Fig. 1A and C). The addition of 1 to 4% ΔflgK was insufficient to repress population-wide swarming (Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), though it is worth noting that a swarming phenotype was variable between technical and biological replicates when the fraction of nonmotile cells was small. This finding is consistent with the variability in swarming ability among replicates that has been previously reported even for single-strain cultures (21, 22), and thus all data for all experiments are summarized in Fig. S1. The ΔflgK mutant, when added at 5% of the population, regularly repressed WT swarming (Fig. S1). In contrast to our finding, work by Boyle et al. (16) reported that ΔflgK repressed swarming only when it was present in excess of the WT. Specifically, the authors reported repression, measured by a reduction in swarm radius, when there was a 1:5 ratio of WT to the ΔflgK mutant; however, images for 1:1 WT:ΔflgK mixes may also suggest a reduction of the swarm area even though swarm radius was not yet affected.

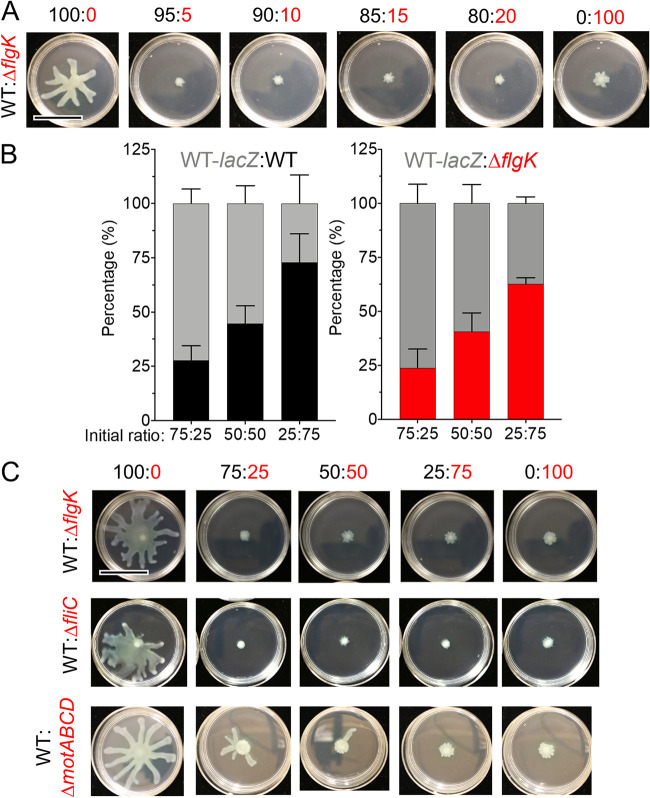

FIG 1.

Motility heterogeneity represses swarming motility independent of competition. (A) Representative images from swarm assay of wild-type (WT) P. aeruginosa strain PA14 (flagellated) mixed with ΔflgK (non-flagellated) at the indicated ratios on M8 agar. WT and derivatives are labeled in black, flagellar mutants are labeled in red. Data are representative of three individual experiments. (B) Competition growth assay between WT tagged with a lacZ reporter (gray) and either an untagged WT (black) or ΔflgK mutant strain (red). Data show the average of three individual experiments. Error bars represent standard deviations between the replicate values. Statistical analysis using one-way analysis of variance showed no difference between input and output for each ratio analyzed. (C) Representative images from swarm assay of WT (flagellated) mixed with ΔflgK (non-flagellated), ΔfliC (non-flagellated), or ΔmotABCD (paralyzed flagellum) at the indicated ratios on M8 agar. Data are representative of three individual experiments. Scale bar, 30 mm.

To determine whether the lack of swarming in WT:ΔflgK co-cultures was due to faster growth of the non-flagellated cells compared to the WT, we competed both the WT and the ΔflgK mutant against a WT strain tagged with a lacZ reporter at different ratios atop a 0.22-μm filter placed on 0.5% M8 agar. After 16 h, the colony was disrupted and the CFU for each strain were enumerated on blue/white screening plates containing X-Gal. At all ratios tested, neither untagged WT nor the ΔflgK mutant could outgrow the lacZ-expressing WT strain (Fig. 1B), indicating that the lack of swarming observed in WT:ΔflgK mixes was not due to increased growth of non-flagellated cells and thus, to overgrowth of the population. Rather, our data suggest that a subpopulation of cells incapable of flagellar motility inhibits the motility of the larger flagellated WT population.

Using conditions in which the non-motile strain comprised 25%, 50%, or 75% of the population, we also found that, like the ΔflgK mutant, the ΔfliC mutant, another strain incapable of flagellar motility due to a lack of the flagellin protein used to make the flagellar filament, inhibited WT swarming at all ratios tested (Fig. 1C). Similarly, the ΔmotABCD mutant, which produces a flagellum that is unable to rotate due to the absence of stators, repressed swarming of the WT; however, compared to ΔflgK and ΔfliC, the ΔmotABCD mutant was slightly less effective at repressing WT swarming (Fig. 1C). Together, these data suggest that the absence of flagellar motility in a subpopulation of cells is sufficient to suppress WT swarming in co-culture.

Functional T4P in flagellated cells are required for non-flagellated cells to repress swarming in co-culture.

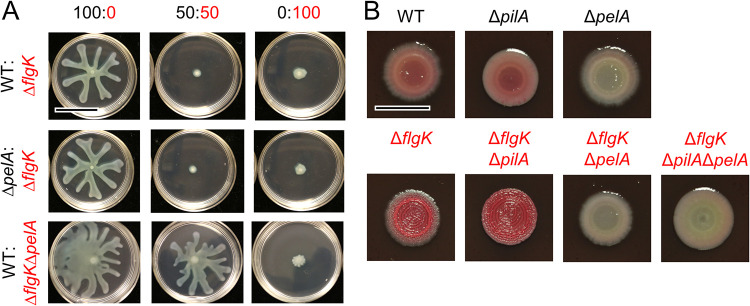

Several studies have shown that P. aeruginosa strains which are deficient in T4P tend to have a hyper-swarming phenotype (23–25), while hyperpiliated strains (those that overproduce elongated pili due to a defect in retraction) have inhibited swarming (15, 26). Additionally, P. aeruginosa cells have been shown to interact via their T4P to form close cell associations that facilitate directional swarming (15). Therefore, we determined whether flagellated cells require T4P in order to facilitate the ability of ΔflgK to inhibit population-wide swarming motility. To do this, we analyzed the ability of ΔflgK to repress swarming when co-cultured with the following mutants: ΔpilA, which lacks T4P; ΔpilMNOP, which lacks the alignment complex required for T4P function (27) and cyclic-di-GMP signaling (28); and both ΔpilT and ΔpilU, hyperpiliated mutants which lack either of the ATPases that mediate T4P retraction (29). Strains lacking pilA, pilMNOP, pilT, and pilU were all defective for twitching motility (Fig. S2 and S3). The swarming motility of strains lacking pilA or pilMNOP was no longer inhibited by the ΔflgK mutant in co-culture (Fig. 2 and Fig. S4). Interestingly, despite its reported hyperpiliation and in contrast to previous reports (15), ΔpilU was capable of swarming, but had an altered morphology compared to the WT (Fig. 2). Swarming by ΔpilU was inhibited by the ΔflgK mutant in co-culture, similar to the WT (Fig. 2 and Fig. S5). However, the hyperpiliated ΔpilT mutant was incapable of swarming (Fig. 2), in agreement with previous models (15). Complementation of the ΔpilU and ΔpilT mutants restored twitching in both strains as well as swarming in ΔpilT (Fig. S6).

FIG 2.

Flagellated P. aeruginosa requires functional T4P to be repressed by the non-motile subpopulation. Representative images from swarm assays of the non-flagellated ΔflgK mutant (functional T4P) mixed with either wild-type (WT) P. aeruginosa strain PA14 (functional T4P), ΔpilA mutant (lacking T4P), ΔpilT mutant (no T4P retraction), or ΔpilU mutant (reduced T4P retraction) at the indicated ratios on M8 agar. Data are representative of three individual experiments. Scale bar, 30 mm.

PilT is the main retractile ATPase, and the ΔpilT mutant completely lacks pilus retraction (26, 30), while the ΔpilU mutant has reduced retraction but still retains some function (26). This accessory role is supported by previous observations that the ΔpilU mutant retained sensitivity to infection by phage PO4, while the ΔpilT mutant became resistant to infection (26). We confirmed that the WT and the ΔpilU mutant were sensitive to phage DMS3 infection and that the ΔpilA and ΔpilT mutants were resistant to infection under our experimental conditions (Fig. S2B). Additionally, while the ΔpilU mutant can form dense biofilms under static conditions (30), its ability to form a biofilm under flow conditions varies by strain (30, 31), possibly due to differences in ΔpilU T4P strength compared to WT and ΔpilT T4P. Differences in T4P strength may allow ΔpilU T4P to readily detach from the cell surface (26, 30). Overall, the data show that ΔpilU displays an intermediate phenotype in that it is hyperpiliated due to reduced T4P retraction, which still results in inhibition of T4P-mediated twitching motility, but not swarming motility. Together, these data indicate that motile cells require T4P, and likely functional T4P, for the non-flagellated subpopulation to inhibit the swarming motility of the WT strain when they are grown in co-culture.

P. aeruginosa T4P participate in a cAMP-dependent signaling pathway (see Fig. S7A for pathway) which involves FimS, PilJ, CyaAB adenylate cyclases, and the cAMP-binding transcription factor Vfr (6). We found that this pathway was not required for the repression of WT swarming motility by the ΔflgK mutant (Fig. S7B), using published mutants lacking components of the cAMP signaling pathway (ΔpilJ, ΔfimS, ΔcyaAB, and Δvfr) which retained expression of partially functional T4P, as evidenced by their sensitivity to phage DMS3 (Fig. S7C). Taken together, these data show that flagellated WT cells require functional T4P, but not the cAMP-dependent surface-sensing pathway, for non-flagellated cells to be able to repress swarming in co-culture.

Non-flagellated cells require functional T4P to repress swarming motility of flagellated cells in co-culture.

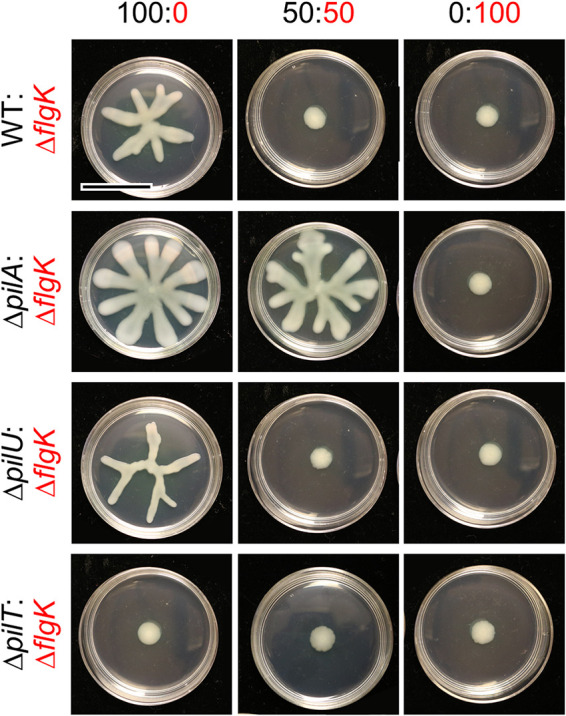

Consistent with published results (4, 32, 33), the ΔflgK mutant has functional T4P, as evidenced by the formation of a large twitching motility zone using an agar-plastic interface assay (Fig. S2A and Fig. S3). While both the WT and ΔflgK formed twitch zones that were significantly larger than those formed by the T4P-null ΔpilA mutant, the ΔflgK twitch zone was ∼25% smaller than that formed by the WT (P < 0.05; Fig. S3A). Using ΔflgK and ΔflgKΔpilA strains, we found that pilA, which encodes the major pilin component of T4P, was required for the ΔflgK mutant to suppress WT swarming on 0.5% M8 agar (Fig. 3A). To assess whether ΔflgK cells needed functional pili to repress the WT, ΔflgK lacking either pilU (reduced T4P retraction) or pilT (no T4P retraction) were mixed with the WT. At all ratios tested, ΔflgKΔpilU and ΔflgKΔpilT were no longer able to repress WT swarming, like ΔflgKΔpilA, indicating that the ΔflgK mutant required fully functional pili to repress population-wide swarming (Fig. 3A and Fig. S8). Complementation of pilU and pilT in ΔflgKΔpilU and ΔflgKΔpilT, respectively, was confirmed to restore twitching motility (Fig. S9); the effect of complementation on swarming motility was not assessed given that ΔflgK does not swarm. In a similar assay using 0.3% M63 agar, which supports both flagellum-mediated swimming and swarming, we found that inoculated spots of ΔflgK cells (Fig. 3B, red dots) decreased local expansion of the motile WT population, while spots of the ΔflgKΔpilA mutant (Fig. 3B, purple dots) did not. In contrast to the effects of ΔflgK cells on flagellar motility, the ΔflgK mutant did not alter T4P-dependent twitching motility of the WT in a 50:50 ratio compared to the that of the WT alone (Fig. S3B). Therefore, the data show that functional T4P are required for non-flagellated cells to inhibit flagellar motility (swimming and swarming) of WT cells in co-culture.

FIG 3.

Non-flagellated P. aeruginosa requires functional T4P to repress flagellum-mediated motility of motile strains on soft agar. (A) Representative images of swarm assays for wild-type (WT) P. aeruginosa strain PA14 (swarmer, T4P+) mixed with ΔflgK (non-swarmer, T4P+), ΔflgKΔpilA (non-swarmer, T4P–), ΔflgKΔpilU (non-swarmer, reduced T4P retraction), or ΔflgKΔpilT (non-swarmer, no T4P retraction) on M8 agar at the indicated ratios. WT is labeled in black, ΔflgK and derivatives are labeled in red. (B) Representative image showing the interaction between WT (black dot), ΔflgK (red dots), and ΔflgKΔpilA (purple dots) for flagellum-mediated swimming motility in soft agar (0.3% M63 agar) after 42 h incubation. Colored dots indicate points of inoculation for the respective strains. Data are representative of three individual experiments. Scale bar, 30 mm.

Non-flagellated P. aeruginosa requires Pel matrix production to repress swarming motility in the flagellated population.

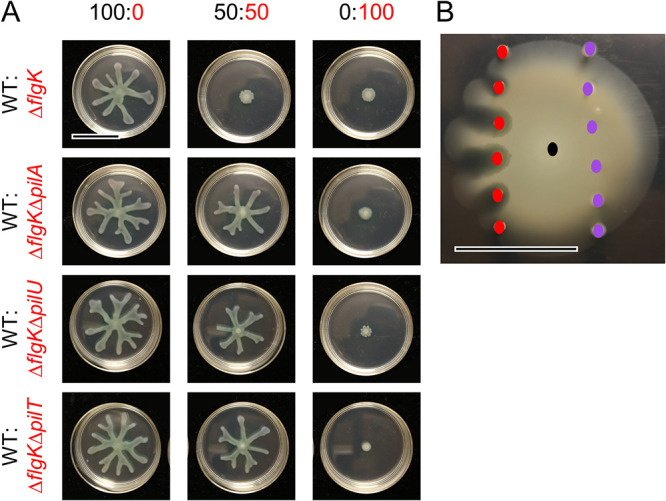

We next explored whether Pel matrix production played a role in swarming repression by using a ΔpelA mutant, which is capable of robust swarming but lacks PelA-mediated deacetylase and hydrolase activities and, subsequently, secretion of properly modified Pel polysaccharide (34). We found that swarming by the ΔpelA mutant was repressed by ΔflgK in co-culture, similar to the WT (Fig. 4A). In contrast, ΔflgKΔpelA did not repress WT swarming (Fig. 4A). Flagellar mutants, such as ΔfliC, have been reported to overexpress Pel and Psl polysaccharides (35). Both ΔflgK and ΔfliC, which repress WT swarming (Fig. 1), had increased Congo red-binding, which is consistent with increased Pel exopolysaccharide production (Fig. 4B and Fig. S10). Additionally, while ΔflgKΔpilA (no T4P), ΔflgKΔpilU (reduced T4P retraction), and ΔflgKΔpilT (no T4P retraction) no longer repressed population-wide swarming motility (Fig. 2A), this did not appear to be due to a change in Pel production, as all ΔflgK mutants displayed an increase in Congo red-binding (Pel production) (Fig. 4B and Fig. S10). Together, these data show that the non-flagellated strain needs to produce Pel matrix to repress swarming motility, but the flagellated strain does not.

FIG 4.

Pel matrix is required by the non-flagellated P. aeruginosa subpopulation alone to repress overall swarming motility. (A) Representative images from swarm assays of ΔflgK (non-flagellated, Pel+) mixed with wild-type (WT) P. aeruginosa strain PA14 (flagellated, Pel+) or ΔpelA (flagellated, Pel–), and of WT mixed with ΔflgKΔpelA (non-flagellated, Pel–), at the indicated ratios on M8 agar. Scale bar, 30 mm. (B) Representative images of WT (flagellated, Pel+, T4P+), ΔpilA (flagellated, Pel+, T4P–), ΔpelA (flagellated, Pel–, T4P+), ΔflgK (non-flagellated, Pel+, T4P+), ΔflgKΔpilA (non-flagellated, Pel+, T4P–), ΔflgKΔpelA (non-flagellated, Pel–, T4P+), and ΔflgKΔpilAΔpelA (non-flagellated, Pel–, T4P–) grown on Congo red plates to assess Pel production. WT and derivatives are labeled in black, ΔflgK and derivatives are labeled in red. Scale bar, 10 mm.

DISCUSSION

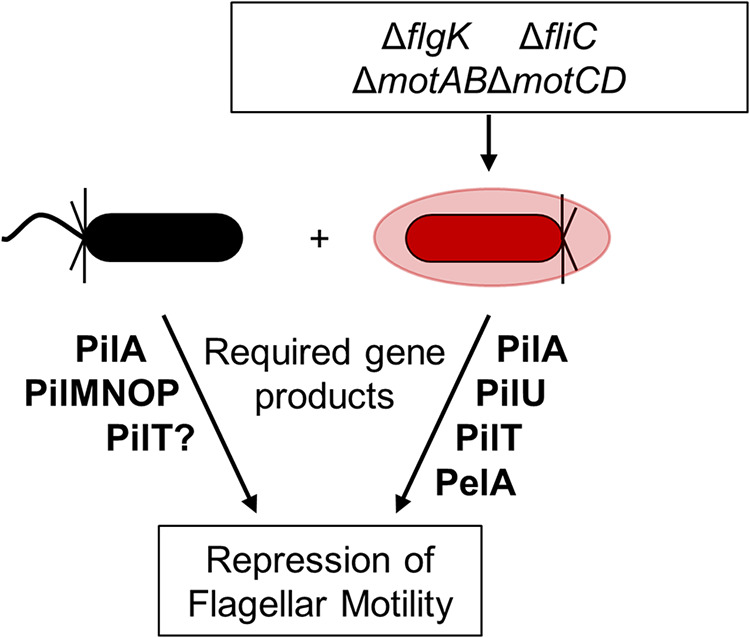

Based on the data presented here, we propose a model (Fig. 5) whereby a subpopulation of cells defective in flagellar motility limits the swarming motility of the entire population. Like Boyle et al. (16), we found that non-motile mutants (e.g., ΔflgK, ΔfliC) can repress WT swarming and, in our assays, only 5% of the population needed to lack flagellar motility to repress swarming by motile cells. Thus, our published findings (3) that ethanol repression of P. aeruginosa flagellar motility may be the result of a combination of direct motility reduction in some cells and interactions between motile and non-motile cells. The number of non-flagellated cells needed to repress WT motility may vary due to experimental conditions, such as medium type and composition. Our analyses revealed that non-flagellated cells required retractile T4P and Pel polysaccharide to inhibit the larger swarming population, and that flagellated cells required retractile T4P, but not the Vfr/cAMP signaling system, to respond to the non-flagellated population. The involvement of T4P and Pel in the recruitment of cells parallels previous studies on microcolony formation during biofilm development and aggregate formation, which has been reported in numerous contexts (e.g., O’Toole and Kolter [4]). While cAMP was not required for the repression of swarming, our previous findings showed that ethanol decreased swarming motility by increasing cyclic-di-GMP (3). Future studies will investigate the role of cyclic-di-GMP levels in the ΔflgK-mediated repression of WT swarming. Furthermore, given that ΔflgK requires retractile T4P and Pel to repress WT swarming, and overproduces Pel compared to the WT, additional studies will test how varying the amount of Pel and TFP in WT and mutant populations contributes to repression of population-wide swarming.

FIG 5.

Summary model describing genes and gene products needed for repression of flagellum-mediated motility by non-flagellated cells in P. aeruginosa strain PA14. We show that a subpopulation of P. aeruginosa cells defective in flagellar motility (red) in co-culture with flagellated cells (black) impedes flagellum-mediated swarming motility in a retractable T4P-dependent manner (PilMNOP, PilA, PilU, PilT). We also show that Pel matrix (PelA), but only that from the non-flagellated strain, is required. PilU, PilJ, FimS, CyaAB, and Vfr were not required for repression of swarming motility.

The involvement of T4P in swarming cells was previously reported by Anyan et al. (15), who reported that T4P impact cell-cell interactions in swarms in ways which limit the movement of cells away from the population front. T4P-null mutants have been shown to have increased swarming motility (23–25), while hyperpiliated mutants have been shown to have decreased swarming motility, compared to the WT (15, 26), suggesting that the intercellular T4P interactions we reported between flagellated and non-flagellated genotypes may also be occurring in single-strain swarms in which all cells have the potential for flagellar motility. Not only may intercellular T4P interactions be occurring in single-strain swarms, but also appropriate flagellum-mediated shear forces during swarming motility (36). This could account for the ability of ΔpilU, a hyperpiliated mutant with fragile and readily sheared T4P, to swarm; unlike ΔpilT, a hyperpiliated mutant with more robust T4P (26, 30). Future studies will determine whether T4P play direct roles in cell-cell interactions or indirect roles in structuring the community.

The WT and ΔpelA mutant responded similarly to non-flagellated cells, while ΔflgKΔpelA was no longer able to repress swarming, suggesting that not all cells need to produce exopolysaccharide to repress swarming. Our findings that Pel production is only necessary in the non-flagellated subpopulation is supported by published data showing that ethanol not only decreases P. aeruginosa flagellar motility (3), but increases Pel production (37). Pel has been suggested to repress motility via the steric hinderance of flagella (3, 38), but further studies are needed to test this hypothesis. The involvement of Pel in the interaction between flagellated and non-flagellated cells is particularly interesting in light of recent work by Whitfield et al. (39), which found that the Pel biosynthetic locus is widespread across Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Future studies will determine whether Pel is specifically detected by a T4P-dependent mechanism.

In the studies here, we seeded a low percentage of non-swarming cells into a swarming population, reminiscent of genetically heterogeneous populations in the CF airway or other chronic infections (19, 40, 41), as well as during normal environmental growth (41, 42). Additionally, clinical P. aeruginosa isolates from the CF lung have diverse motility phenotypes (19). This diversity in motility is even observed within single patients (19). We hypothesize that such a mechanism promotes inter- and intraspecies interactions. The strong implication of these findings is that in a mixed population with a subpopulation of cells deficient in flagellar motility, the entire population can be brought to a halt. Similarly, in a population in which a significant number of cells have stopped swimming or swarming, the further addition of even a few flagellar-mutant cells can suppress the motility of the entire population (e.g., the ethanol studies mentioned above). As P. aeruginosa populations inherently have some number of nonmotile or inactive cells (3), future studies are required to determine how strain background or mutant genotype affects phenotypic heterogeneity among isogenic cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

Strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. P. aeruginosa strain PA14 and derivatives were routinely cultured on lysogeny broth (LB; 1% tryptone [wt/vol], 0.5% yeast extract [wt/vol], and 0.5% NaCl [wt/vol]) solidified with 1.5% agar or in LB broth at 37°C with shaking. For P. aeruginosa phenotypic assays, either M63 [22 mM KH2PO4, 40 mM K2HPO4, and 15 mM (NH4)2SO4] or M8 (42 mM Na2PO4, 22 mM KH2PO4, and 8.5 mM NaCl) minimal salts medium supplemented with MgSO4 (1 mM), glucose (0.2%), and Casamino acids (CAA; 0.5%) were used as indicated. Complemented strains containing genes regulated by an arabinose-inducible promoter (PBAD) were grown in the presence of 0.25% arabinose.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this studya

| Strain or plasmid | Lab strain | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa | |||

| PA14 | DH123 | WT | 45 |

| PA14 att::lacZ | DH22 | WT with constitutive expression of lacZ | 46 |

| ΔflgK | DH1075 | flgK::Tn5B30(Tc); nonmotile | 4 |

| ΔfliC | DH3543 | Unmarked deletion of fliC | This study |

| ΔmotABCD | SMC7230 | Unmarked deletion of motABCD | This study |

| ΔpilMNOP | DH2705 | Unmarked deletion of pilMNOP | 6 |

| ΔpilA | DH2636 | Unmarked deletion of pilA | 24 |

| ΔpelA | DH97 or SMC2893 | Unmarked deletion of pelA | 47 |

| ΔflgKΔpelA | DH3541 | Unmarked deletion of flgK and pelA | 11 |

| ΔflgKΔpilA | DH3539 | Unmarked deletion of flgK and pilA | 11 |

| ΔflgKΔpilAΔpelA | DH3542 | Unmarked deletion of flgK, pilA, and pelA | 11 |

| ΔpilT | DH3591 or SMC7302 | Unmarked deletion of pilT | 31 |

| ΔpilU | DH3592 or SMC7304 | Unmarked deletion of pilU | 31 |

| ΔpilJ | DH2637 or SMC2992 | Unmarked deletion of pilJ | 48 |

| ΔfimS | SMC6967 | Unmarked deletion of fimS | 6 |

| ΔcyaAB | DH2648 or SMC6707 | Unmarked deletion of cyaAB | 6 |

| Δvfr | DH2701 or SMC6722 | Unmarked deletion of vfr | 6 |

| ΔpilU att::PBAD-ara | SMC7826 | Unmarked ΔpilU (DH3592/SMC7304) with arabinose-inducible promoter at the attTn7 site, control, GmR | This study |

| ΔpilU att::PBAD-pilU | SMC7827 | Unmarked ΔpilU (DH3592/SMC7304) complemented with arabinose-inducible pilU at the attTn7 site, GmR | This study |

| ΔpilT att::PBAD-ara | SMC8882 | Unmarked ΔpilT (DH3591/SMC7302) with arabinose-inducible promoter at the attTn7 site, control, GmR | This study |

| ΔpilT att::PBAD-pilT | SMC8883 | Unmarked ΔpilT (DH3591/SMC7302) complemented with arabinose-inducible pilT at the attTn7 site, GmR | This study |

| ΔflgKΔpilU | DH3950 | Unmarked deletion of flgK and pilU | This study |

| ΔflgKΔpilT | DH3951 | Unmarked deletion of flgK and pilT | This study |

| ΔflgKΔpilU att::PBAD-ara | DH3952 | Unmarked deletion of flgK and pilU with arabinose-inducible promoter at the attTn7 site, control, GmR | This study |

| ΔflgKΔpilU att::PBAD-pilU | DH3953 | Unmarked deletion of flgK and pilU complemented with arabinose-inducible pilU at the attTn7 site, control, GmR | This study |

| ΔflgKΔpilT att::PBAD-ara | DH3954 | Unmarked deletion of flgK and pilT with arabinose-inducible promoter at the attTn7 site, control, GmR | This study |

| ΔflgKΔpilT att::PBAD-pilT | DH3955 | Unmarked deletion of flgK and pilT complemented with arabinose-inducible pilT at the attTn7 site, control, GmR | This study |

| E. coli | |||

| S17 λpir | DH71 | Used as a conjugation partner for introducing pMQ30- and GH121-based plasmids | |

| Plasmids | |||

| pUX-BF13 | SMC1852 | Helper plasmid that provides the transposition functions for Tn7 in trans, ApR | 49 |

| pMQ56 | SMC3242 | pMQ56-miniTn7 for insertion at the attTn7 site, ApR | 43 |

| pBAD-ara | SMC7453 | pMQ56-miniTn7 plasmid containing arabinose-inducible PBAD and araC for insertion at the attTn7 site, ApR, GmR | This study |

| pPilU-His | SMC7777 | pMQ56-miniTn7 plasmid containing 6× His-tagged pilU regulated by arabinose-inducible PBAD and araC for insertion at the attTn7 site, ApR, GmR | This study |

| pPilT-His | SMC8873 | pMQ56-miniTn7 plasmid containing 6× His-tagged pilT regulated by arabinose-inducible PBAD and araC for insertion at the attTn7 site, ApR, GmR | This study |

| pMQ30 | DH2620 | Suicide vector for allelic replacement; GmR | 43 |

| pMQ30-del-pilT | SMC7298 | Construct for in-frame deletion of pilT | 31 |

| pMQ30-del-pilU | SMC7299 | Construct for in-frame deletion of pilU | 31 |

WT, wild type.

Construction and complementation of mutant strains.

Plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmid constructs for making in-frame deletions and arabinose-inducible complementation strains were constructed using either a Saccharomyces cerevisiae recombination technique, described previously (43), or Gibson assembly. All plasmids were sequenced at the Molecular Biology Core at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth. Plasmids were introduced into P. aeruginosa by conjugation via S17/lambda pir E. coli. Merodiploids were selected by drug resistance, and double recombinants were obtained using sucrose counter-selection and genotype screening by PCR.

Swarming motility assays.

Swarm assays were performed as previously described (44). Briefly, 9 mL of M8 medium with 0.5% agar (swarm agar) was poured into 60 × 15 mm plates and allowed to dry at room temperature (∼25°C) for 3 h prior to inoculation. The indicated strains were grown for 16 h, then each was washed in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then normalized to an OD600 (optical density at 600 nm) of 1. Indicated isolates were then mixed at the indicated ratios to a final volume of 100 μL. Each plate was inoculated with 0.5 μL of the liquid culture mixture, and the plates were incubated face-up at 37°C for up to 22 h, in stacks of no more than four plates. Each mixture was inoculated in three to four replicates and assessed on at least three separate days. Images were captured using a Canon EOS Rebel T6i camera and images assessed for swarm repression.

Swimming motility assays.

Swim assays were performed as previously described (44). Briefly, M63 medium solidified with 0.3% agar (soft agar) was poured into 100 × 15 mm petri plates and allowed to dry at room temperature (∼25°C) for 3 h prior to inoculation. The indicated strains were grown for 16 h, then each was washed in 1× PBS and then normalized to an OD600 of 1. Indicated isolates were then mixed at the indicated ratios to a final volume of 100 μL. Sterile toothpicks or P20 pipette tips were used to inoculate bacterial mixes into the center of the agar without touching the bottom of the plate. No more than four bacterial mixtures were assayed per plate. Plates were incubated upright at 37°C in stacks of no more than four plates per stack for 18 to 20 h.

Twitching motility assays.

T-broth (1% tryptone [wt/vol], 0.5% NaCl [wt/vol]) medium solidified with 1.5% agar was poured into petri plates and allowed to dry at room temperature (∼25°C) for 3 h. Overnight (16 h) cultures were washed once in 1× PBS and then normalized to an OD600 of 1. Plates were inoculated by dipping a sterile toothpick or P20 pipette tip into the washed and normalized cultures and then inserting the toothpick into the agar until it touched the bottom of the plate. Plates were then incubated at 37°C for 46 h after which time the agar was removed and the plate incubated in 0.1% (wt/vol) crystal violet for 10 min. Plates were then washed three times in water and dried at room temperature. Images of the dried, stained twitch area were taken and twitch diameter was measured.

Competition experiments.

Competition assays were performed to determine relative growth of selected P. aeruginosa strains. Strains were grown for 16 h and then 1 mL of culture was pelleted at 15,682 × g for 2 min, washed once in 1 mL 1× PBS, and then resuspended in 1 mL 1× PBS. The OD600 of each culture was normalized to 1. The strains to be competed were mixed at the indicated ratios to a final volume of 100 μl, and then 0.5 μL of the combined suspension was spotted onto a 0.22-μm polycarbonate filter (Millipore) placed on the surface of a swarm plate, in triplicate. Plates were incubated at 37°C. Filters were then transferred to a 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tube, and filter-associated cells were resuspended by adding 1 mL 1× PBS + 0.05% Triton X-100 detergent and agitating the tubes at high speed for 2 min using a Disruptor Genie (Zymo). This suspension as well as the starting inoculum were diluted, spread on LB plates supplemented with 150 μg/mL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) using glass beads, and incubated at 30°C until blue colonies were visible (∼24 h). The numbers of blue and white colonies per plate were counted and recorded to determine the relative abundance of each strain.

Phage susceptibility assays.

Phage susceptibility was analyzed by the cross-streak method or by spotting phage directly onto a lawn of P. aeruginosa. For the cross-streak method, P. aeruginosa strains were grown for 16 h in LB, diluted 1:100 in LB, and then grown to an OD600 of 0.5 to 0.7. Then, 4 μL of phage DMS3 vir strain was spotted on the side of an LB agar plate and dragged across the agar surface in a straight line before being allowed to absorb into the agar. Once absorbed, 4 μL of each P. aeruginosa strain was spotted at the top of the agar and dragged downward in a straight line through the phage line. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 16 h.

Alternatively, 1% M8 agar plates (60 × 15 mm) containing 0.2% glucose (vol/vol), 0.5% Casamino Acids (vol/vol), and 1 mM MgSO4 were prepared and cooled to room temperature. A 50-μL volume of P. aeruginosa 16 h cultures was added to 1 mL of 0.5% warm top agar (M8 medium and supplements). The mixture was gently mixed and quickly poured onto M8 agar plates. Plates were swirled to ensure even spreading of top agar. Once cooled, 2 μL of phage DMS3 vir strain was spotted onto the center of the plate and allowed to dry before incubating plates at 37°C for 16 h.

Congo red-binding assay.

Cultures were grown in 5 mL LB for 16 h at 37°C with rolling. Culture aliquots were washed once and resuspended in sterile deionized water. Washed cells were spotted (3 μL) onto Congo red plates (1% tryptone [wt/vol], 1.5% agar, 40 μg/mL Congo red, 20 μg/mL Coomassie blue). Plates were grown for 16 h at 37°C and then moved to room temperature for 3 days to allow for color development.

Statistical analysis.

A one-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons was performed pairwise between all isolates and mixtures using GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by CFF HOGAN19G0 to D.A.H., NIH NIAID R37 AI83256 to G.A.O., NIH NIAID R01 AI43730 to G.C.L.W., NSF DGE GRFP 1650604 to Jd.A., and CFF VERMIL21F0 to D.M.V. This work was also supported by NIH NIDDK P30 DK117469 for the Applied Bioinformatics and Biostatistics Core. Sequencing services and specialized equipment was provided by the Genomics and Molecular Biology Shared Resource Core at Dartmouth supported by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant NIH NCI P30 CA023108. Equipment used was supported by the NIH NIGMS IDeA award P20 GM113132 to Dartmouth BioMT.

We thank Amy Baker for constructing the ΔfliC mutant, Christine Toutain for constructing the ΔmotABCD mutant, and Sherry Kuchma for constructing the ΔpilT att::PBAD and ΔpilT att::PBAD-pilT strains.

K.A.L. conceptualized the project, generated most data for the first submission, and contributed to manuscript preparation for first submission. D.M.V. generated data and contributed to manuscript preparation for the first submission and was primarily responsible for data generation and manuscript preparation for the second submission.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Deborah A. Hogan, Email: dhogan@dartmouth.edu.

Michael Y. Galperin, NCBI, NLM, National Institutes of Health

REFERENCES

- 1.Hogan DA, Kolter R. 2002. Pseudomonas-Candida interactions: an ecological role for virulence factors. Science 296:2229–2232. 10.1126/science.1070784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Limoli DH, Warren EA, Yarrington KD, Donegan NP, Cheung AL, O'Toole GA. 2019. Interspecies interactions induce exploratory motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Elife 8:e47365. 10.7554/eLife.47365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis KA, Baker AE, Chen AI, Harty CE, Kuchma SL, O’Toole GA, Hogan DA. 2019. Ethanol decreases Pseudomonas aeruginosa flagellar motility through the regulation of flagellar stators. J Bacteriol 201:e00285-17. 10.1128/JB.00285-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Toole GA, Kolter R. 1998. Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol Microbiol 30:295–304. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao K, Tseng BS, Beckerman B, Jin F, Gibiansky ML, Harrison JJ, Luijten E, Parsek MR, Wong GCL. 2013. Psl trails guide exploration and microcolony formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Nature 497:388–391. 10.1038/nature12155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo Y, Zhao K, Baker AE, Kuchma SL, Coggan KA, Wolfgang MC, Wong GCL, O’Toole GA. 2015. A hierarchical cascade of second messengers regulates Pseudomonas aeruginosa surface behaviors. mBio 6:e02456-14. 10.1128/mBio.02456-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Toole GA, Wong GC. 2016. Sensational biofilms: surface sensing in bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol 30:139–146. 10.1016/j.mib.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee CK, Vachier J, de Anda J, Zhao K, Baker AE, Bennett RR, Armbruster CR, Lewis KA, Tarnopol RL, Lomba CJ, Hogan DA, Parsek MR, O’Toole GA, Golestanian R, Wong GCL. 2020. Social cooperativity of bacteria during reversible surface attachment in young biofilms: a quantitative comparison of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 and PAO1. mBio 11:e02644-19. 10.1128/mBio.02644-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd CD, Smith TJ, El-Kirat-Chatel S, Newell PD, Dufrene YF, O'Toole GA. 2014. Structural features of the Pseudomonas fluorescens biofilm adhesin LapA required for LapG-dependent cleavage, biofilm formation, and cell surface localization. J Bacteriol 196:2775–2788. 10.1128/JB.01629-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parsek MR. 2016. Controlling the connections of cells to the biofilm matrix. J Bacteriol 198:12–14. 10.1128/JB.00865-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ribbe J, Baker AE, Euler S, O'Toole GA, Maier B. 2017. Role of cyclic di-GMP and exopolysaccharide in type IV pilus dynamics. J Bacteriol 199:e00859-16. 10.1128/JB.00859-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma L, Conover M, Lu H, Parsek MR, Bayles K, Wozniak DJ. 2009. Assembly and development of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000354. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colvin KM, Irie Y, Tart CS, Urbano R, Whitney JC, Ryder C, Howell PL, Wozniak DJ, Parsek MR. 2012. The Pel and Psl polysaccharides provide Pseudomonas aeruginosa structural redundancy within the biofilm matrix. Environ Microbiol 14:1913–1928. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei Q, Ma LZ. 2013. Biofilm matrix and its regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Mol Sci 14:20983–21005. 10.3390/ijms141020983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anyan ME, Amiri A, Harvey CW, Tierra G, Morales-Soto N, Driscoll CM, Alber MS, Shrout JD. 2014. Type IV pili interactions promote intercellular association and moderate swarming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:18013–18018. 10.1073/pnas.1414661111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyle KE, Monaco HT, Deforet M, Yan J, Wang Z, Rhee K, Xavier JB. 2017. Metabolism and the evolution of social behavior. Mol Biol Evol 34:2367–2379. 10.1093/molbev/msx174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lozano C, Azcona-Gutierrez JM, Van Bambeke F, Saenz Y. 2018. Great phenotypic and genetic variation among successive chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa from a cystic fibrosis patient. PLoS One 13:e0204167. 10.1371/journal.pone.0204167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahenthiralingam E, Campbell ME, Speert DP. 1994. Nonmotility and phagocytic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from chronically colonized patients with cystic fibrosis. Infect Immun 62:596–605. 10.1128/iai.62.2.596-605.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Workentine ML, Sibley CD, Glezerson B, Purighalla S, Norgaard-Gron JC, Parkins MD, Rabin HR, Surette MG. 2013. Phenotypic heterogeneity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa populations in a cystic fibrosis patient. PLoS One 8:e60225. 10.1371/journal.pone.0060225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner KH, Everett J, Trivedi U, Rumbaugh KP, Whiteley M. 2014. Requirements for Pseudomonas aeruginosa acute burn and chronic surgical wound infection. PLoS Genet 10:e1004518. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ha DG, Kuchma SL, O'Toole GA. 2014. Plate-based assay for swarming motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Methods Mol Biol 1149:67–72. 10.1007/978-1-4939-0473-0_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tremblay J, Deziel E. 2008. Improving the reproducibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa swarming motility assays. J Basic Microbiol 48:509–515. 10.1002/jobm.200800030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shrout JD, Chopp DL, Just CL, Hentzer M, Givskov M, Parsek MR. 2006. The impact of quorum sensing and swarming motility on Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation is nutritionally conditional. Mol Microbiol 62:1264–1277. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuchma SL, Ballok AE, Merritt JH, Hammond JH, Lu W, Rabinowitz JD, O'Toole GA. 2010. Cyclic-di-GMP-mediated repression of swarming motility by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: the pilY1 gene and its impact on surface-associated behaviors. J Bacteriol 192:2950–2964. 10.1128/JB.01642-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuchma SL, Griffin EF, O'Toole GA. 2012. Minor pilins of the type IV pilus system participate in the negative regulation of swarming motility. J Bacteriol 194:5388–5403. 10.1128/JB.00899-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitchurch CB, Mattick JS. 1994. Characterization of a gene, pilU, required for twitching motility but not phage sensitivity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 13:1079–1091. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tammam S, Sampaleanu LM, Koo J, Sundaram P, Ayers M, Chong PA, Forman-Kay JD, Burrows LL, Howell PL. 2011. Characterization of the PilN, PilO and PilP type IVa pilus subcomplex. Mol Microbiol 82:1496–1514. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Webster SS, Lee CK, Schmidt WC, Wong GCL, O'Toole GA. 2021. Interaction between the type 4 pili machinery and a diguanylate cyclase fine-tune c-di-GMP levels during early biofilm formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118:e2105566118. 10.1073/pnas.2105566118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burrows LL. 2005. Weapons of mass retraction. Mol Microbiol 57:878–888. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiang P, Burrows LL. 2003. Biofilm formation by hyperpiliated mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 185:2374–2378. 10.1128/JB.185.7.2374-2378.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee CK, de Anda J, Baker AE, Bennett RR, Luo Y, Lee EY, Keefe JA, Helali JS, Ma J, Zhao K, Golestanian R, O’Toole GA, Wong GCL. 2018. Multigenerational memory and adaptive adhesion in early bacterial biofilm communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115:4471–4476. 10.1073/pnas.1720071115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen Y, Siryaporn A, Lecuyer S, Gitai Z, Stone HA. 2012. Flow directs surface-attached bacteria to twitch upstream. Biophys J 103:146–151. 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landry RM, An D, Hupp JT, Singh PK, Parsek MR. 2006. Mucin-Pseudomonas aeruginosa interactions promote biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance. Mol Microbiol 59:142–151. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marmont LS, Whitfield GB, Rich JD, Yip P, Giesbrecht LB, Stremick CA, Whitney JC, Parsek MR, Harrison JJ, Howell PL. 2017. PelA and PelB proteins form a modification and secretion complex essential for Pel polysaccharide-dependent biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem 292:19411–19422. 10.1074/jbc.M117.812842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrison JJ, Almblad H, Irie Y, Wolter DJ, Eggleston HC, Randall TE, Kitzman JO, Stackhouse B, Emerson JC, McNamara S, Larsen TJ, Shendure J, Hoffman LR, Wozniak DJ, Parsek MR. 2020. Elevated exopolysaccharide levels in Pseudomonas aeruginosa flagellar mutants have implications for biofilm growth and chronic infections. PLoS Genet 16:e1008848. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodesney CA, Roman B, Dhamani N, Cooley BJ, Katira P, Touhami A, Gordon VD. 2017. Mechanosensing of shear by Pseudomonas aeruginosa leads to increased levels of the cyclic-di-GMP signal initiating biofilm development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114:5906–5911. 10.1073/pnas.1703255114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen AI, Dolben EF, Okegbe C, Harty CE, Golub Y, Thao S, Ha DG, Willger SD, O'Toole GA, Harwood CS, Dietrich LE, Hogan DA. 2014. Candida albicans ethanol stimulates Pseudomonas aeruginosa WspR-controlled biofilm formation as part of a cyclic relationship involving phenazines. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004480. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merritt JH, Brothers KM, Kuchma SL, O'Toole GA. 2007. SadC reciprocally influences biofilm formation and swarming motility via modulation of exopolysaccharide production and flagellar function. J Bacteriol 189:8154–8164. 10.1128/JB.00585-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whitfield GB, Marmont LS, Bundalovic-Torma C, Razvi E, Roach EJ, Khursigara CM, Parkinson J, Howell PL. 2020. Discovery and characterization of a Gram-positive Pel polysaccharide biosynthetic gene cluster. PLoS Pathog 16:e1008281. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Darch SE, McNally A, Harrison F, Corander J, Barr HL, Paszkiewicz K, Holden S, Fogarty A, Crusz SA, Diggle SP. 2015. Recombination is a key driver of genomic and phenotypic diversity in a Pseudomonas aeruginosa population during cystic fibrosis infection. Sci Rep 5:7649. 10.1038/srep07649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Head NE, Yu H. 2004. Cross-sectional analysis of clinical and environmental isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: biofilm formation, virulence, and genome diversity. Infect Immun 72:133–144. 10.1128/IAI.72.1.133-144.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grosso-Becerra MV, Santos-Medellin C, Gonzalez-Valdez A, Mendez JL, Delgado G, Morales-Espinosa R, Servin-Gonzalez L, Alcaraz LD, Soberon-Chavez G. 2014. Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical and environmental isolates constitute a single population with high phenotypic diversity. BMC Genomics 15:318. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shanks RM, Caiazza NC, Hinsa SM, Toutain CM, O'Toole GA. 2006. Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based molecular tool kit for manipulation of genes from gram-negative bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:5027–5036. 10.1128/AEM.00682-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ha DG, Richman ME, O'Toole GA. 2014. Deletion mutant library for investigation of functional outputs of cyclic diguanylate metabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:3384–3393. 10.1128/AEM.00299-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rahme LG, Stevens EJ, Wolfort SF, Shao J, Tompkins RG, Ausubel FM. 1995. Common virulence factors for bacterial pathogenicity in plants and animals. Science 268:1899–1902. 10.1126/science.7604262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clay ME, Hammond JH, Zhong F, Chen X, Kowalski CH, Lee AJ, Porter MS, Hampton TH, Greene CS, Pletneva EV, Hogan DA. 2020. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR mutant fitness in microoxia is supported by an Anr-regulated oxygen-binding hemerythrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:3167–3173. 10.1073/pnas.1917576117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friedman L, Kolter R. 2004. Genes involved in matrix formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 biofilms. Mol Microbiol 51:675–690. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Belete B, Lu H, Wozniak DJ. 2008. Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgR regulates type IV pilus biosynthesis by activating transcription of the fimU-pilVWXY1Y2E operon. J Bacteriol 190:2023–2030. 10.1128/JB.01623-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hojberg O, Schnider U, Winteler HV, Sorensen J, Haas D. 1999. Oxygen-sensing reporter strain of Pseudomonas fluorescens for monitoring the distribution of low-oxygen habitats in soil. Appl Environ Microbiol 65:4085–4093. 10.1128/AEM.65.9.4085-4093.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1-S10. Download jb.00528-21-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.8 MB (814.5KB, pdf)