Abstract

Sakacin K is an antilisterial bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus sake CTC 494, a strain isolated from Spanish dry fermented sausages. The biokinetics of cell growth and bacteriocin production of L. sake CTC 494 in vitro during laboratory fermentations were investigated by making use of MRS broth. The data obtained from the fermentations was used to set up a predictive model to describe the influence of the physical factors temperature and pH on microbial behavior. The model was validated successfully for all components. However, the specific bacteriocin production rate seemed to have an upper limit. Both cell growth and bacteriocin activity were very much influenced by changes in temperature and pH. The production of biomass was closely related to bacteriocin activity, indicating primary metabolite kinetics, but was not the only factor of importance. Acidity dramatically influenced both the production and the inactivation of sakacin K; the optimal pH for cell growth did not correspond to the pH for maximal sakacin K activity. Furthermore, cells grew well at 35°C but no bacteriocin production could be detected at this temperature. L. sake CTC 494 shows special promise for implementation as a novel bacteriocin-producing sausage starter culture with antilisterial properties, considering the fact that the temperature and acidity conditions that prevail during the fermentation process of dry fermented sausages are optimal for the production of sakacin K.

Fermentation is a worldwide and ancient preservation technique, probably one of the oldest methods known (51). It is commonly employed to preserve or enhance the organoleptic attributes and microbiological safety of foods. Indigenous microorganisms have been responsible for fermentation traditionally, but starter cultures can now be added to induce fermentation and favorable processing conditions can be selected to ensure desired quality (6, 23). These processes encourage the development of a desirable safe microflora, which is important for preventing the outgrowth of spoilage bacteria and food-borne pathogens.

With the increasing demand for biological preservation techniques, the application of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) as starter or protective cultures is gaining interest (20). Some LAB show special promise as they do not pose any health risk to man and are able to prevent the outgrowth of undesirable bacteria and opportunistic pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Listeria monocytogenes. Microbial antagonism is due to the production of metabolites such as lactic acid, acetic acid, diacetyl, hydrogen peroxide, and bacteriocins. Bacteriocins are, in general, small cationic peptides (30 to 60 amino acid residues) with high isoelectric points and amphiphilic characteristics that inhibit at micromolar concentrations the growth of bacterial species closely related to the producing organism and thus provide this organism with a selective advantage over its natural competitors (13).

Many of the antimicrobial activities associated with Lactobacillus meat isolates were proven to be bacteriocin mediated (17, 30, 40). In most cases activity against Listeria monocytogenes was detected. Examples of such bacteriocins are sakacins A, M, and P (19, 39, 41, 45), curvacin A (45), curvaticins 13 and FS47 (18, 43), plantaricin BN (25), lactocin 705 (47), acidocin B (44), salivaricin B (44), and bavaricin MN (25, 49). Antilisterial activities by LAB have been demonstrated for fermented meat systems, such as with American-style fermented meat products (2, 14, 36), Italian salami (5), and Spanish-style dry fermented sausages (22). Although no Listeria outbreak due to the consumption of fermented meat products has yet been reported, several health authorities have expressed their concern (22). A high rate of patient fatality (circa 30%) (1) and the resistance of Listeria to low temperature, pH, and water activity and to high concentrations of NaCl have indeed made the bacterium a major concern for the modern food industry (35). Gahan et al. even warn us about acid-adapted Listeria mutants that have an increased ability to survive in low-pH foods (15).

The application of bacteriocin-producing lactic acid starter cultures may be a potential solution for preserving fermented meat products from the outgrowth of Listeria monocytogenes (22). However, although the results of active inhibition of Listeria outgrowth in meat are encouraging, bacteriocin activity in meat was shown to be less effective than in broth (42), probably due to partial inactivation by proteases, limited diffusion in the food matrix, and unspecific binding to food ingredients such as fat particles (8, 20). Therefore, the production of bioavailable, active bacteriocins must be increased (4). Careful selection of strains adapted to certain food environments and food processing conditions such as temperature and pH is absolutely necessary.

In this paper, the kinetics of in vitro cell growth and bacteriocin production of a Lactobacillus sake starter strain during laboratory fermentations were investigated by making use of MRS broth. The data obtained from the fermentations was used to set up a predictive model to describe the influence of the physical factors temperature and pH on microbial behavior. The bacterium investigated was the bacteriocinogenic strain L. sake CTC 494, which has previously been isolated from dry fermented sausages and has been characterized by Hugas et al. (21). The bacteriocin produced was designated sakacin K; it has a bacteriolytic effect on Listeria monocytogenes. L. sake CTC 494 has excellent starter culture capacities. Besides producing bacteriocin, it is highly competitive in the meat environment and imparts good sensorial and organoleptic qualities to the final product (22).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms and media.

L. sake CTC 494, a producer of sakacin K (22), and Listeria innocua LMG 13568, which was used as an indicator organism to determine bacteriocin activity levels, were stored at −80°C in MRS broth (9) (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) and brain heart infusion (Oxoid), respectively, both of which contained 25% (vol/vol) glycerol as a cryoprotectant. L. sake CTC 494 was kindly provided by M. Hugas (Institut de Recerca i Technologia Agroalimentàries, Meat Technology Center, Monells, Spain). The strains were propagated twice at 30°C for 12 h before experimental use. Solid medium was prepared by adding 1.5% agar (Oxoid) to the broth. The overlays needed for the estimation of the bacteriocin titer were prepared with 0.7% agar.

Fermentation experiments.

In order to investigate the influence of temperature and pH on both the growth and the bacteriocin production of L. sake CTC 494, a series of fermentations was performed with MRS broth (9).

Fermentations were carried out in a 15-liter laboratory fermentor (Biostat C; B. Braun Biotech International, Melsungen, Germany) containing 10 liters of MRS broth. The vessel was sterilized in situ at 121°C for 20 min. Glucose was sterilized separately and aseptically added to the fermentor. For the preparation of the inoculum, 10 ml of MRS broth was inoculated with 0.5 ml of a freshly prepared L. sake CTC 494 culture and incubated for 12 h at 30°C. This preculture was added to 90 ml of MRS broth. After 11 h of growth at 30°C this culture was used to inoculate the fermentor (1%, vol/vol). Temperature and pH control was performed on-line (Micro-MFCS for Windows NT; B. Braun Biotech International). The pH was controlled to within pH 0.05 of the set point by automatic addition of 10 M NaOH. Temperature stayed within 0.1°C of the set point. Moderate agitation (50 rpm) was performed to ensure homogeneity of the broth.

During the first experiments the pH was maintained at 6.5 while the fermentations were carried out at 20, 25, 30, and 35°C. In a second series of experiments the temperature was held at 30°C while the fermentations were carried out with pHs of 4.5, 5.0, 5.5, and 6.5. For the validation of the model, two additional fermentations were performed, one at a temperature of 25°C and a pH of 5.5 and the other at a temperature of 23°C and a pH of 5.0.

Assays.

Samples were withdrawn aseptically from the fermentor in order to determine cell dry mass (CDM), bacteriocin activity, lactic acid concentration, and residual glucose concentration. CDM was determined after membrane filtration (0.45-μm-pore-size filters, type HA; Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) of a known volume of fermentation liquor, followed by washing the filter with demineralized water and drying it overnight at 105°C. Microcentrifugation (13,000 × g for 10 min) was performed in order to obtain cell-free samples, needed for the measurement of lactic acid and residual glucose concentration with a high-performance liquid chromatograph (Waters Corporation, Milford, Mass.) and also for the estimation of bacteriocin activity levels. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis was performed as described previously (11). The soluble bacteriocin activity was determined by a modified critical dilution method (10). Briefly, serial twofold dilutions of cell-free culture supernatant with sodium phosphate buffer (50 mmol liter−1, pH 6.5) were spotted (10 μl) onto indicator lawns. The lawns were prepared by adding fresh cultures of Listeria innocua LMG 13568 with an optical density at 600 nm of 0.45 to 3.5 ml of brain heart infusion overlay agar. Overlaid agar plates were incubated at 30°C. Activity was expressed in arbitrary units (AU), corresponding to 10 μl of the highest dilution causing a definite zone of inhibition on the lawn of the indicator organism.

Model development.

Cell growth was modeled with the equation for logistic growth (46); this equation has been frequently used to describe the growth of LAB (24, 27, 31):

|

1 |

where X is the CDM concentration (in grams of CDM per liter), t is time (in hours), μmax is the maximum specific growth rate (per hour), and Xmax is the maximum attainable CDM concentration (in grams of CDM per liter) under a given set of conditions. By this model, the specific growth rate [μ = μmax (1 − X/Xmax)] decreases linearly as cell concentration increases.

Glucose consumption can be described by using the maintenance energy model of Pirt (32):

|

2 |

where S is the residual glucose concentration (in grams of glucose per liter), YX/S is the cell yield coefficient (in grams of CDM per gram of glucose), and mS is the maintenance coefficient (in grams of glucose per gram of CDM per hour).

Lactic acid production can be calculated from the consumption of glucose, with YL/S (in grams of lactic acid per gram of glucose) being a yield coefficient for the conversion of glucose into lactic acid:

|

3 |

where L is lactic acid production (in grams of lactic acid per liter).

Sakacin K is produced as a primary metabolite, and its titer increases with CDM (this paper). When CDM production stagnates as the growth curve reaches the stationary phase, bacteriocin production ceases and the activity decreases due to proteolytic degradation, aggregation, or adsorption to the cells (10, 11, 31). The soluble bacteriocin activity (B), which was measured in the cell-free supernatant, can be expressed in arbitrary units per liter as follows (31):

|

4 |

where kb is the specific bacteriocin production (in arbitrary units per gram of CDM) and kinact is the specific rate of bacteriocin degradation (in liters per gram of CDM per hour). However, this equation has never been validated experimentally.

The relation between maximum specific growth rate and temperature can be obtained with the equation of Ratkowsky et al. (33):

|

5 |

where a (per hour per degree Celsius squared) and Tmin (in degrees Celsius) are regression coefficients, with Tmin being the theoretical minimum temperature for cell growth. Wijtzes et al. have demonstrated that for Lactobacillus curvatus Tmin is independent of the pH (48).

Growth behavior can also be expressed as a function of pH with a parabolic equation (48):

|

6 |

where b (per hour) is a regression coefficient and pHmin and pHmax are the theoretical minimum and maximum pHs for cell growth, respectively. Neither pHmin nor pHmax showed a trend as a function of temperature for the growth of an L. curvatus strain (48).

Combining equations 5 and 6 as

|

7 |

yields a general equation for the combined effect of temperature and pH on the maximum specific rate of growth, with c (per hour per degree Celsius squared) being a regression coefficient (48).

Equations 1, 2, 3, and 4 were integrated with the Euler integration technique with Microsoft Excel version 7.0. All parameters needed for the modeling were estimated by manual adjustment until a good visual fit was obtained.

RESULTS

Modeling of the fermentation profiles.

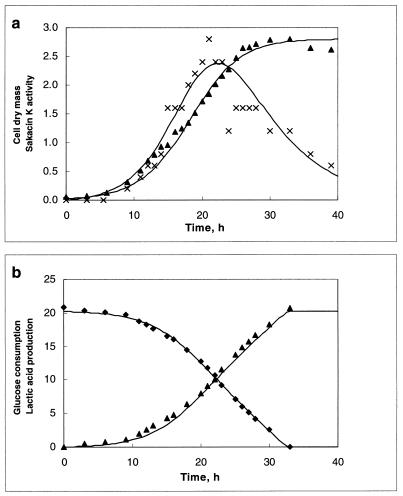

The influence of temperature and pH on both the growth and the bacteriocin production of L. sake CTC 494 was assessed. The data concerning the consumption of glucose and the production of biomass, lactic acid, and bacteriocin in fermentations maintained at constant pHs and temperatures were fitted with equations 1 to 4. Biokinetic parameters were varied manually until a good visual fit of the curves was obtained. Figure 1 is included as an illustrative example, representing a fermentation run at a controlled temperature and pH of 20°C and 6.5, respectively. The experimental as well as the modeled evolutions of CDM concentration and bacteriocin titer (Fig. 1a) and of residual glucose concentration and lactic acid production (Fig. 1b) are shown. To check the repeatability of the results, one of the fermentations (30°C, pH 6.5; see below), which was chosen randomly, was carried out in fourfold. Standard deviations of 0.03 g of CDM g of glucose−1, 0.04 g of glucose g of CDM−1 h−1, 0.05 h−1, 0.11 g of CDM liter−1, 48 AU ml−1, and 0.02 liter g of CDM−1 h−1 for YX/S, mS, μmax, Xmax, kb, and kinact, respectively, were obtained. Validation of the model further contributes to the reliability of the experiments (see below).

FIG. 1.

Modeling of the biomass (in grams of CDM per liter; ▴) and bacteriocin production (in arbitrary units [in millions] per liter; ×) (a) and the lactic acid production (in grams per liter; ▴) and glucose consumption (in grams per liter; ⧫) (b) of L. sake CTC 494 in MRS broth at a controlled temperature and pH of 20°C and pH 6.5.

Bacteriocin activity increased rapidly while cells were growing exponentially. This finding confirmed equation 4, which supposes that the production rate of bacteriocin is related to the production rate of biomass, and indicated clearly that the production of bacteriocin by L. sake CTC 494 follows primary metabolite kinetics (11, 12, 24). Once cell mass production began to level off, bacteriocin activity decreased rather quickly. This decrease was more pronounced at the high temperatures and pH values, indicating greater proteolytic degradation or adsorption (Tables 1 and 2).

TABLE 1.

Influence of temperature on μmax, YX/S, mS, Xmax, Bmax, kb, and kinact of L. sake CTC 494 in MRS broth at a constant pH of 6.5

| Temp (°C) | μmax (h−1) | YX/S (g of CDM g of glucose−1) | mS (g of glucose g of CDM−1 h−1) | Xmax (g of CDM liter−1) | Bmax (MAU liter−1) | kb (kAU g of CDM−1) | kinact (liter g of CDM−1 h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 0.27 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 2.72 | 2.43 | 1,700 | 0.05 |

| 25 | 0.45 | 0.31 | 0.40 | 2.68 | 3.27 | 2,250 | 0.09 |

| 30 | 0.56 | 0.25 | 0.56 | 2.15 | 0.95 | 800 | 0.16 |

| 35 | 0.71 | 0.23 | 0.70 | 1.67 | 0.00 | 0 | —a |

—, not relevant.

TABLE 2.

Influence of pH on μmax, YX/S, mS, Xmax, Bmax, kb, and kinact of L. sake CTC 494 in MRS broth at a constant temperature of 30°C

| pH | μmax (h−1) | YX/S (g of CDM g of glucose−1) | mS (g of glucose g of CDM−1 h−1) | Xmax (g of CDM liter−1) | Bmax (MAU liter−1) | kb (kAU g of CDM−1) | kinact (liter g of CDM−1 h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.5 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.90 | 0.00 | 0 | —a |

| 5.0 | 0.39 | 0.24 | 0.35 | 1.90 | 3.50 | 2,600 | 0.03 |

| 5.5 | 0.52 | 0.29 | 0.50 | 1.98 | 1.22 | 850 | 0.04 |

| 6.5 | 0.56 | 0.25 | 0.56 | 2.15 | 0.95 | 800 | 0.16 |

—, not relevant.

For all experiments the yield coefficient, YL/S, for lactate production was equal to 1 g g−1. This means that all glucose was converted into lactic acid, confirming the homofermentative character of L. sake CTC 494. The other parameters (μmax, YX/S, mS, Xmax, kb, and kinact) were dependent on pH and temperature (see below).

Influence of temperature.

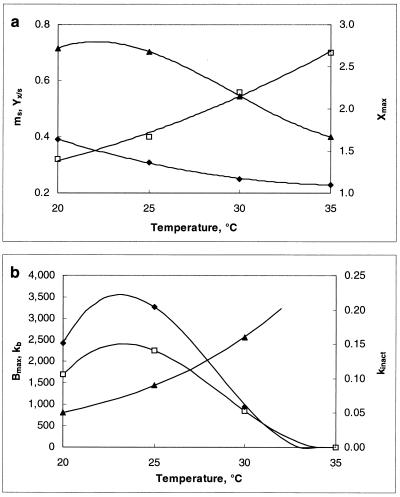

Table 1 and Fig. 2 demonstrate the influence of temperature at a constant pH of 6.5 on the different parameters used in the model. They indicate that at a pH of 6.5 both bacteriocin and cell mass production were optimal at a temperature between 20 and 25°C. At 35°C, no bacteriocin was produced and only 61% of the biomass obtained at 20°C was achieved. Hence, the bacteriocin-producing isolate L. sake CTC 494 clearly showed mesophilic growth behavior.

FIG. 2.

Influence of temperature on the biomass production (YX/S [⧫] in grams of CDM per gram of glucose, mS [□] in grams of glucose per gram of CDM per hour, and Xmax [▴] in grams of CDM per liter) (a) and the bacteriocin production (Bmax [⧫] in arbitrary units per milliliter, kb [□] in arbitrary units [in thousands] per gram of CDM, and kinact [▴] in liters per gram of CDM per hour) (b) of L. sake CTC 494 in MRS broth at a constant pH of 6.5. Lines are drawn according to the model.

Above 25°C the specific bacteriocin production decreased rather rapidly as a function of temperature to become 0 at 34°C. Furthermore, the degradation of bacteriocin activity (kinact) became more important if temperature increased, probably due to a higher protease activity or cell-bacteriocin or bacteriocin-bacteriocin interaction. This degradation of bacteriocin activity resulted in low bacteriocin titers when a fermentation temperature of more than 30°C was applied.

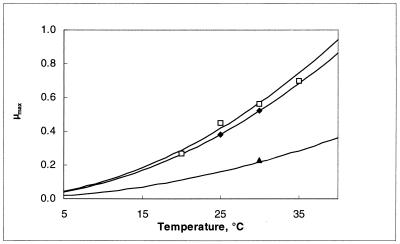

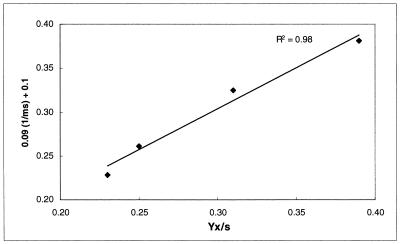

Figure 3 shows the relation between temperature and maximum specific growth rate as calculated with the model of Ratkowsky et al. (equation 6). Cells grew faster with higher temperature. The cell yield, however, decreased because the energy needed for maintenance is higher when temperature increases. Apparently, the maintenance coefficient is correlated (r2 = 0.98) with the inverse of the cell yield coefficient, as is represented in Fig. 4.

FIG. 3.

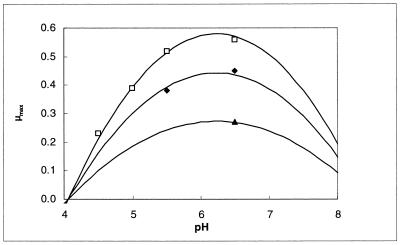

Influence of temperature on the maximum specific growth rate (per hour) of L. sake CTC 494 in MRS broth at pH 4.5 (▴), pH 5.5 (⧫), and pH 6.5 (□). Lines drawn are according to the model.

FIG. 4.

Correlation between the cell yield coefficient (YX/S [in grams of CDM per gram of glucose]) and the inverse of the maintenance coefficient (mS [in grams of glucose per gram of CDM per hour]) for growth of L. sake CTC 494 in MRS broth at different temperatures.

Influence of pH.

When temperature is kept at a constant value, it is possible to investigate the effect of the acidity level on cell growth and bacteriocin production. Table 2 and Fig. 5 show the values of the different parameters used for modeling (μmax, YX/S, mS, Xmax, kb, and kinact) and of the highest bacteriocin titer (Bmax) obtained. The fermentations were performed at a constant temperature of 30°C.

FIG. 5.

Influence of pH on the biomass production (YX/S [⧫] in grams of CDM per gram of glucose, mS [□] in grams of glucose per gram of CDM per hour, and Xmax [▴] in grams of CDM per liter) (a) and the bacteriocin production (Bmax [⧫] in arbitrary units per milliliter, kb [□] in arbitrary units [in thousands] per gram of CDM, and kinact [▴] in liters per gram of CDM per hour) (b) of L. sake CTC 494 in MRS broth at a constant temperature of 30°C. Lines drawn are according to the model.

Maximal cell yield was obtained between pH 5.5 and 6.5. Sakacin K production was maximal at pH 5.0, but the acidity range for optimal bacteriocin production was rather narrow. With a fermentation temperature of 30°C, bacteriocin titer appeared to be fairly low at pH values above 5.5 and undetectable at pH 4.5. The bacteriocin inactivation rate increased when pH increased, probably because of the higher degree of adsorption to the cells.

As shown in Fig. 6, cells grew fastest between pH 6.0 and 6.5 while the theoretical minimum and maximum pHs for growth were 4.06 and 8.40, respectively.

FIG. 6.

Influence of pH on the maximum specific growth rate (per hour) of L. sake CTC 494 in MRS broth at 20°C (▴), 25°C (⧫), and 30°C (□). Lines drawn are according to the model.

Model.

An empirical model was obtained from the experimental data by combining the temperature and pH profiles. The model allows calculation of parameters for cell growth and bacteriocin production for a range of physiological pH and temperature (T) values (20°C ≤ T ≤ 35°C; 4.5 ≤ pH ≤ 6.5). Eventually, calculated values that are negative have to be set to 0.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

where e is the base of the natural logarithm. In addition, equation 7 yielded a formula for the estimation of μmax:

|

The model gives satisfactory correlations (r2 ≥ 0.93) with experimental values for all parameters (Table 3). The validation of the model through fermentations at 25°C with pH 5.5 and 23°C with pH 5.0 was successful, as predicted values corresponded well with the experimental measurements. However, the predicted value for the specific bacteriocin production rate, kb, for the fermentation at 23°C and pH 5.0 was far below expectations (2,950 instead of 8,010 kAU g of CDM−1). Apparently, kb had reached its upper limit and higher values could not be achieved when acidity and temperature were varied under the given set of environmental conditions.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of calculated and experimental values for μmax, YX/S, mS, Xmax, Bmax, kb, and kinact for L. sake CTC 494 at a given combination of pH and temperaturea

| Temp (°C) | pH | Calculated (exptl) value for:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μmax (h−1) | YX/S (g of CDM g of glucose−1) | mS (g of glucose h−1 g of CDM−1) | Xmax (g liter−1) | kb (kAU g of CDM−1) | kinact (liter g of CDM−1 h−1) | ||

| 20 | 6.5 | 0.29 (0.27) | 0.37 (0.39) | 0.33 (0.32) | 2.75 (2.72) | 1,750 (1,700) | 0.05 (0.05) |

| 23 | 5.0 | 0.25 (0.25) | 0.32 (0.33) | 0.20 (0.18) | 2.24 (2.12) | 8,010 (2,950) | 0.01 (0.02) |

| 25 | 6.5 | 0.41 (0.45) | 0.30 (0.31) | 0.46 (0.40) | 2.70 (2.68) | 2,290 (2,250) | 0.09 (0.09) |

| 25 | 5.5 | 0.37 (0.38) | 0.34 (0.32) | 0.31 (0.26) | 2.48 (2.68) | 2,870 (2,800) | 0.03 (0.03) |

| 30 | 6.5 | 0.56 (0.56) | 0.25 (0.25) | 0.60 (0.56) | 2.14 (2.15) | 800 (800) | 0.15 (0.16) |

| 30 | 5.5 | 0.51 (0.53) | 0.29 (0.29) | 0.41 (0.50) | 1.96 (1.98) | 1,000 (1,000) | 0.05 (0.04) |

| 30 | 5.0 | 0.39 (0.39) | 0.25 (0.24) | 0.32 (0.35) | 1.71 (1.90) | 2,600 (2,600) | 0.03 (0.03) |

| 30 | 4.5 | 0.21 (0.23) | 0.16 (0.15) | 0.16 (0.12) | 0.90 (0.90) | 0 (0) | —b |

| 35 | 6.5 | 0.73 (0.71) | 0.23 (0.23) | 0.67 (0.70) | 1.57 (1.67) | 0 (0) | — |

r2 values for μmax, YX/S, mS, Xmax, kb, and kinact were 0.987, 0.998, 0.935, 0.968, 0.999 (the kb values for 23°C and pH 5.0 were omitted), and 0.989, respectively.

—, not relevant.

DISCUSSION

Lactobacilli and pediococci are naturally involved in various meat fermentations and are consequently used as starter cultures (6). Most studies about the in situ behavior of bacteriocins against Listeria monocytogenes have been done with bacteriocinogenic strains of Pediococcus acidilactici. This species is the main starter culture used in the manufacture of American-style fermented meat products. In Europe, fermented sausages are manufactured with starter cultures containing mainly L. sake and L. curvatus and, to a lesser extent, Lactobacillus plantarum. Few papers about the inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes during meat fermentations by a bacteriocinogenic strain of L. sake have been published (22, 38). In addition, only the competitiveness and inhibitory capacity towards Listeria have been examined. There was no examination of bacteriocin production kinetics.

This paper describes a model for the production of biomass and bacteriocin by the bacteriocin-producing meat isolate L. sake CTC 494. The modeled growth (determined with the logistic equation) and sakacin K activity curves fit well with experimental data. The assumption that bacteriocin titer is dependent on cell growth was confirmed experimentally. Activity increases while cells are growing exponentially and decreases when cell mass production begins to level off. This leveling off occurs when cell growth becomes inhibited due to the accumulation of lactic acid and the exhaustion of sugar and possibly of essential amino acids (26).

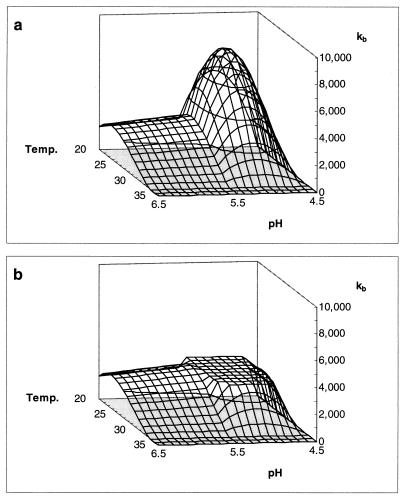

A combined model was elaborated from temperature and pH profiles in order to predict both cell growth and bacteriocin production for any combination of temperature and acidity level (between 20 and 35°C and pH 4.5 and 6.5, respectively). The model was validated successfully by two extra fermentations for all parameters (μmax, YX/S, YL/S, mS, Xmax, and kinact) except for the specific bacteriocin production rate (kb). The experimental value (2,950 kAU g of CDM−1) was far below the predicted peak value (8,010 kAU g of CDM−1) (Fig. 7). Apparently, this is the highest value one can practically achieve when the pH and temperature of classical MRS broth are varied. This may be due to a limited immunity of bacteriocin-producing cells. A modification might be made in the model by introducing a cutoff value for kb of 2,950 kAU g of CDM−1 as an upper limit.

FIG. 7.

Surface model showing the influence of pH and temperature (in degrees Celsius) on kb (in arbitrary units [in thousands] per gram of CDM) before (a) and after (b) introduction of an upper limit for this parameter.

The parameters used in the model all appeared to be strongly influenced by pH and temperature (Fig. 7 to 9). However, in all such experiments, as the total amount of glucose is quantitatively converted into lactate, the yield coefficient, YL/S, for lactate production can be set equal to 1 g g−1 for any combination of temperature and pH. This means that L. sake CTC 494 is a homofermentative LAB, which is a desirable feature for sausage starter cultures. Another consequence is that apparently no glucose is used for the building of the cell material, which is due to the facts that LAB metabolize sugars predominantly to generate a necessary flux of biochemical energy but that cell material is synthesized from nitrogen-containing organic matter (7).

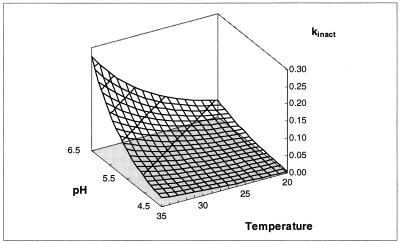

FIG. 9.

Surface model showing the influence of pH and temperature (in degrees Celsius) on kinact (in liters per gram of CDM per hour).

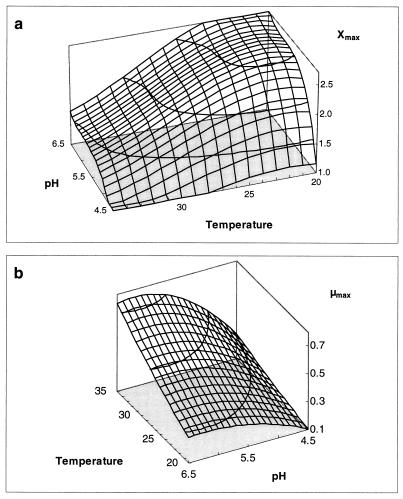

The production of biomass and sakacin K is obviously related to temperature. Maximal values are achieved at temperatures between 20 and 25°C. Interestingly, the fermentation of European sausages is performed at similar temperatures (34). Schillinger obtained comparable results for L. sake Lb 706, stating that optimal growth and sakacin A production occur at temperatures between 20 and 30°C (37). Sakacin K titer drops significantly as temperature exceeds 25°C. This is due to the combined effect of a lower specific productivity (kb) (Fig. 7) and a higher bacteriocin degradation rate (kinact) (Fig. 9). Although cells grow faster, cell yield also decreases with higher temperatures (Fig. 8), because the energy needed for maintenance becomes more important. Maintenance-generating processes, such as turnover of macromolecules and maintenance of proton gradients, are indeed strongly growth dependent (29). The maintenance coefficient (mS) seems to be correlated with the inverse of the cell yield coefficient (YX/S).

FIG. 8.

Surface model showing the influence of pH and temperature (in degrees Celsius) on Xmax (in grams of CDM per liter) (a) and μmax (per hour) (b).

The optimal pH for growth rate and biomass formation (pH 6.0) does not correspond to the optimal pH for sakacin K production. This is because the tendency to produce sakacin K (specific bacteriocin production) is maximal at pH 5.0 (Fig. 7) and because the sakacin K inactivation rate increases with pH due to greater adsorption to the cells (Fig. 9). Adsorption is pH dependent (50) and nonspecific and probably involves lipoteichoic acids (3). At 30°C, sakacin K activity is highest at pH 5.0, 0 at pH 4.5, and rather low at pH 5.5, meaning that the pH range for good sakacin production is narrow. This range, however, corresponds to the pH drop observed with the fermentation of sausages (normally from a pH of about 5.8 to a final value of approximately 4.8).

These results indicate that satisfactory sakacin K activity can be expected when L. sake CTC 494 is used as a sausage starter culture. Microbial growth and bacteriocin bioavailability in situ will also be dependent on the influence of several other factors, such as the presence of (curing) salts (16), a limited diffusion of both nutrients and bacteriocin in the sausage matrix, and a lowered water activity of the microbial environment. This knowledge can be used to develop new protective and/or starter organisms with the potential to improve both the hygienic status of the food and their competitiveness in food fermentations. Hugas et al. have indeed demonstrated a diminishment of Listeria number by 1.25 log units in sausages fermented with L. sake CTC 494 compared to that of sausages fermented with a nonbacteriocinogenic control strain (22). Considering both the antilisterial capacities of the strain and the good sensorial quality of the final product, one can postulate that L. sake CTC 494 has high potential for industrial application as a novel bacteriocin-producing sausage starter culture. In addition, previous studies have shown that the addition of original isolates to the sausage mixture results in the inhibition of staphylococcal growth, mainly due to acid production (28). The combined action of organic acids and bacteriocin might be effective against undesirable opportunistic bacteria in fermented meat products.

In this paper, an attempt was made to model the production of biomass and bacteriocin by the bacteriocin-producing isolate L. sake CTC 494. It was shown that the temperature and acidity conditions that prevail during the fermentation process of dry fermented sausages are optimal for the production of sakacin K. Although the experiments were carried out with in vitro cultures, the research will contribute to a better understanding of the behavior of the strain in the meat environment. Further work is in progress to investigate the influence of the particular conditions prevailing in fermented sausages (salt, curing agents, limited diffusion in the matrix, low water activity, etc.) on sakacin K production and L. sake CTC 494 growth.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was financially supported by the Research Council of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, the Fund for Scientific Research—Flanders, and the European Community (grant FAIR-CT97-3227).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bean N H, Griffin P M. Foodborne disease outbreaks in the United States, 1973–1987: pathogens, vehicles and trends. J Food Prot. 1990;53:148–150. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-53.9.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berry E D, Liewen M B, Mandigo R W, Hutkins R W. Inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes by bacteriocin-producing Pediococcus during the manufacture of fermented semidry sausage. J Food Prot. 1990;53:194–197. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-53.3.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhunia A K, Johnson M C, Ray B, Kalchayanand N. Mode of action of pediocin AcH from Pediococcus acidilacti H on sensitive bacterial strains. J Appl Bacteriol. 1991;70:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buncic S, Avery S M, Moorhead S M. Insufficient antilisterial capacity of low inoculum Lactobacillus cultures on long-term stored meats at 4°C. Int J Food Microbiol. 1997;34:157–170. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(96)01181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campanini M, Pedrazzoni I, Barbuti S, Baldini P. Behaviour of Listeria monocytogenes during the maturation of naturally and artificially contaminated salami: effect of lactic-acid bacteria starter cultures. Int J Food Microbiol. 1993;20:169–175. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(93)90109-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell-Platt G. Fermented meats—a world perspective. In: Campbell-Platt G, Cook P E, editors. Fermented meats. London, United Kingdom: Blackie Academic & Professional; 1995. pp. 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cocaign-Bousquet M, Garrigues C, Loubière P, Lindley N D. Physiology of pyruvate metabolism in Lactococcus lactis. Antonie Leeuwenhoek Int J Gen Mol Microbiol. 1996;70:253–267. doi: 10.1007/BF00395936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daeschel M A. Applications and interactions of bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria in foods and beverages. In: Hoover D G, Steenson L R, editors. Bacteriocins of lactic acid bacteria. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 63–91. [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Man J C, Rogosa M, Sharpe M E. A medium for the cultivation of lactobacilli. J Appl Bacteriol. 1960;23:130–135. [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Vuyst L, Callewaert R, Pot B. Characterization and antagonistic activity of Lactobacillus amylovorus DCE471 and large scale isolation of its bacteriocin amylovorin L471. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1996;19:9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Vuyst L, Callewaert R, Crabbé K. Primary metabolite kinetics of bacteriocin biosynthesis by Lactobacillus amylovorus and evidence for stimulation of bacteriocin production under unfavourable growth conditions. Microbiology. 1996;142:817–827. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-4-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Vuyst L, Vandamme E J. Influence of the carbon source on nisin production in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis batch fermentations. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:571–578. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-3-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Vuyst L, Vandamme E J. Antimicrobial potential of lactic acid bacteria. In: De Vuyst L, Vandamme E J, editors. Bacteriocins of lactic acid bacteria: microbiology, genetics and applications. London, United Kingdom: Blackie Academic & Professional; 1994. pp. 91–142. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foegeding P M, Thomas A B, Pilkington D H, Klaenhammer T R. Enhanced control of Listeria monocytogenes by in situ-produced pediocin during dry fermented sausage production. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:884–890. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.3.884-890.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gahan C G M, O’Driscoll B, Hill C. Acid adaptation of Listeria monocytogenes can enhance survival in acidic foods and during milk fermentation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3128–3132. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3128-3132.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gänzle M G, Hertel C, Hammes W P. Modelling the effect of pH, NaCl, and nitrite concentrations on the antimicrobial activity of sakacin P against Listeria ivanovii DSM 20750. Fleischwirtschaft. 1996;76:409–412. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garriga M, Hugas M, Aymerich T, Monfort J M. Bacteriocinogenic activity of lactobacilli from fermented sausages. J Appl Bacteriol. 1993;75:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1993.tb02759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garver K I, Muriana P M. Detection, identification and characterization of bacteriocin-producing lactic acid bacteria from retail food products. Int J Food Microbiol. 1993;19:241–258. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(93)90017-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holck A L, Axelsson L, Hühne K, Kröckel L. Purification and cloning of sakacin 674, a bacteriocin from Lactobacillus sake Lb674. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;115:143–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holzapfel W H, Geisen R, Schillinger U. Biological preservation of foods with reference to protective cultures, bacteriocins and food-grade enzymes. Int J Food Microbiol. 1995;24:343–362. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hugas M, Garriga M, Aymerich M T, Monfort J M. Biochemical characterization of lactobacilli isolated from dry sausages. Int J Food Microbiol. 1993;18:107–113. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(93)90215-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hugas M, Garriga M, Aymerich M T, Monfort J M. Inhibition of Listeria in dry fermented sausages by the bacteriocinogenic Lactobacillus sake CTC494. J Appl Bacteriol. 1995;79:322–330. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawrie R. The structure, composition and preservation of meat. In: Campbell-Platt G, Cook P E, editors. Fermented meats. London, United Kingdom: Blackie Academic & Professional; 1995. pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lejeune R, Callewaert R, Crabbé K, De Vuyst L. Modeling the growth and bacteriocin production by Lactobacillus amylovorus DCE 471 in batch cultivation. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;84:159–168. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewus C B, Montville T J. Further characterization of bacteriocins plantaricin BN, bavaricin MN and pediocin A. Food Biotechnol. 1992;6:153–174. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loubière P, Cocaign-Bousquet M, Matos J, Goma G, Lindley N D. Influence of end-products inhibition and nutrient limitations on the growth of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. J Appl Microbiol. 1997;82:95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mercier P, Yerusalmi L, Rouleau D, Dochain D. Kinetics of lactic acid fermentation on glucose and corn by Lactobacillus amylophilus. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 1992;55:111–121. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metaxopoulos J, Genigeorgis C, Fanelli M J, Franti C, Cosma E. Production of Italian dry salami: effect of starter culture and chemical acidulation on staphylococcal growth in salami under commercial manufacturing conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;42:863–871. doi: 10.1128/aem.42.5.863-871.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen J, Nikolajsen K, Villadsen J. Structured modeling of a microbial system II. Experimental verification of a structured lactic acid fermentation model. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1991;38:11–23. doi: 10.1002/bit.260380103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papathanasopoulos M A, Franz C M A P, Dykes G A, von Holy A. Antimicrobial activity of meat spoilage lactic acid bacteria. S-Afr Tydskr Wet. 1991;87:243–246. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parente E, Ricciardi A, Addario G. Influence of pH on growth and bacteriocin production by Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis 140NWC during batch fermentation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1994;41:388–394. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pirt S J. The maintenance energy of bacteria in growing cultures. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1965;163:224–231. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1965.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ratkowsky D A, Olley J, McMeekin T A, Ball A. Relationship between temperature and growth rate of bacterial cultures. J Bacteriol. 1982;149:565–568. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.1.1-5.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ricke S C, Keeton J T. Fermented meat, poultry and fish products. In: Doyle M P, Beuchat L R, Montville T J, editors. Food microbiology: fundamentals and frontiers. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1997. pp. 610–628. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rocourt J, Cossart P. Listeria monocytogenes. In: Doyle M P, Beuchat L R, Montville T J, editors. Food microbiology: fundamentals and frontiers. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1997. pp. 337–352. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sabel D, Yousef A E, Marth E H. Behaviour of Listeria monocytogenes during fermentation of beaker sausage made with or without a starter culture and antioxidant food additives. Lebensm-Wiss Technol. 1991;24:252–255. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schillinger U. Sakacin A produced by Lactobacillus sake Lb 706. In: De Vuyst L, Vandamme E J, editors. Bacteriocins of lactic acid bacteria: microbiology, genetics and applications. London, United Kingdom: Blackie Academic & Professional; 1994. pp. 419–434. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schillinger U, Kaya M, Lücke F K. Behaviour of Listeria monocytogenes in meat and its control by a bacteriocin-producing strain of Lactobacillus sake. J Appl Bacteriol. 1991;70:473–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1991.tb02743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schillinger U, Lücke F K. Antibacterial activity of Lactobacillus sake isolated from meat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:1901–1906. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.8.1901-1906.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sobrino O J, Rodríguez J M, Moreira W L, Fernández M F, Sanz B, Hernández P E. Antibacterial activity of Lactobacillus sake isolated from dry fermented sausages. Int J Food Microbiol. 1991;13:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(91)90130-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sobrino O J, Rodríguez J M, Moreira W L, Cintas L M, Fernández M F, Sanz B, Hernández P E. Sakacin M, a bacteriocin-like substance from Lactobacillus sake 148. Int J Food Microbiol. 1992;16:215–225. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(92)90082-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stiles M E, Hastings J W. Bacteriocin production by lactic acid bacteria: potential for use in meat preservation. Trends Food Sci Technol. 1991;2:247–251. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sudirman I, Mathier F, Michel M, Lefebvre G. Detection and properties of curvaticin 13, a bacteriocin-like substance produced by Lactobacillus curvatus SB13. Curr Microbiol. 1993;27:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 44.ten Brink B, Minekus M, van der Vossen J M B M, Leer R J, Huis in ’t Veld J H J. Antimicrobial activity of lactobacilli: preliminary characterization and optimization of production of acidocin B, a novel bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus acidophilus M46. J Appl Bacteriol. 1994;77:140–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1994.tb03057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tichaczek P S, Nissen-Meyer J, Nes I F, Vogel R F, Hammes W P. Characterization of the bacteriocins curvacin A from Lactobacillus curvatus LTH1174 and sakacin P from L. sake LTH673. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1992;15:460–468. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verhulst R. Notice sur la loi que la population suit dans son accroissement. Corresp Math Phys. 1838;10:113. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vignolo G M, Suriani F, de Ruiz Holgado A P, Oliver G. Antibacterial activity of Lactobacillus strains isolated from dry fermented sausages. J Appl Bacteriol. 1993;75:344–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1993.tb02786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wijtzes T, de Wit J C, Huis in ’t Veld J H J, van ’t Riet K, Zwietering M H. Modeling bacterial growth of Lactobacillus curvatus as a function of acidity and temperature. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2533–2539. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2533-2539.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winkowski K, Montville T J. Use of meat isolate, Lactobacillus bavaricus MN, to inhibit Listeria monocytogenes growth in a model meat gravy system. J Food Saf. 1992;13:19–31. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang R, Johnson M C, Ray B. Novel method to extract large amounts of bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3355–3359. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.10.3355-3359.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zeuthen P. Historical aspects of meat fermentations. In: Campbell-Platt G, Cook P E, editors. Fermented meats. London, United Kingdom: Blackie Academic & Professional; 1995. pp. 53–68. [Google Scholar]