Abstract

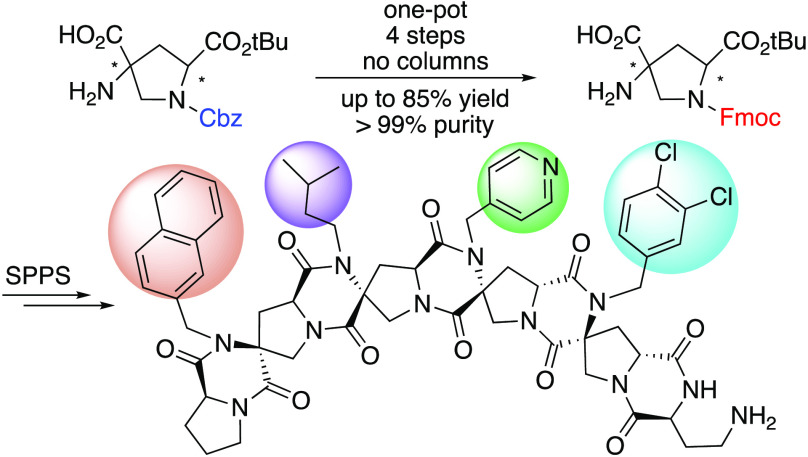

We report the fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) protection of functionalized bis-amino acid building blocks using a temporary Cu2+ complexation strategy, together with an efficient multikilogram-scale synthesis of bis-amino acid precursors. This allows the synthesis of stereochemically and functionally diverse spiroligomers utilizing solid-phase Fmoc/tBu chemistry to facilitate the development of applications. Four tetramers were assembled on a semiautomated microwave peptide synthesizer. We determined their secondary structures with two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

“Molecular structure defines function”. This is the most fundamental paradigm of molecular biology.1 It is a goal of macromolecular chemistry to create ever-larger molecules with control over their three-dimensional structure and the constellation of functional groups that they present.2,3 Stoddart first introduced the concept of a “molecular LEGO” that can be programmed to have desired shapes through iterative ring fusion, such as the belt[n] arenes and kohnkenes, these are ladder molecules that have structure without folding.4 More recently, the Bode group has demonstrated the iterative assembly of polycyclic saturated heterocycles from monomeric building blocks.5 Spiroligomers are fused ring spiro-ladder structures constructed from cyclic, stereochemically pure bis-amino acid building blocks joined together through diketopiperazine (DKP) rings.6 The formation of spirocyclic DKPs enforces the rigidity of the backbone by eliminating single-bond rotation in the backbone. Meanwhile, the positions and orientations of various functional groups on the backbones are dictated by the sequence and stereochemistry of building blocks. Various applications of spiroligomers are being developed, including as catalysts of organic reactions,7 templates of supramolecular metal binding complexes,8 inhibitors of protein–protein interactions,9 and carbohydrate binding molecules.10 Functionalized spiroligomer synthesis has been difficult because the monomer syntheses are time-consuming even at a scale of ∼600 mmol. Previously, the original carboxybenzyl (Cbz), the tert-butoxycarbonyl (Boc), and the p-nitrobenzyloxycarbonyl (pNZ) groups have been used as the chain-extension removable protecting group for the proline amine in solid-phase synthesis. These protecting groups either were difficult to remove (Cbz) or led to side reactions during deprotection and limited the choices of resin linking groups to those that provide low yields.11,12 The fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc) group, as an excellent temporary protecting group in peptide synthesis, allows the use of excellent high-yield cleavable resin linkers like the chloro-trityl linker.13−15 We describe here how we efficiently incorporated the Fmoc group into spiroligomer synthesis. The approach combines a scaled-up synthesis of bis-amino acid intermediates at a scale of tens of kilograms scale and an efficient one-pot synthetic methodology to replace the Cbz group with the Fmoc group. Four unique spiroligomers were synthesized using the Fmoc/tBu solid-phase synthesis, and their three-dimensional structures were confirmed by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy.

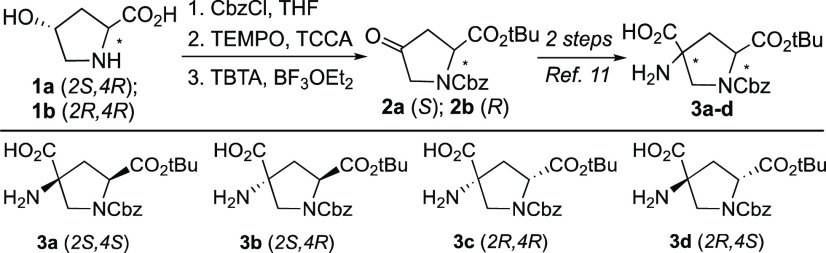

To significantly reduce the labor cost of bis-amino acid synthesis and take advantage of economies of scale, we contracted chemists at WuXi Apptec to develop a large-scale synthesis toward key ketone intermediates 2a and 2b. Compared with the previous synthesis we developed,11 the new route in Scheme 1 increased the intermediate synthesis scale by 3 orders of magnitude. The scaled-up synthesis eliminated the use of highly toxic Jones reagent,16 replacing it with a (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl (TEMPO)-mediated trichloroisocyanuric acid (TCCA) oxidation that avoids downstream problems with impurities that we encountered at a small scale. The scaled-up synthesis also eliminated explosive isobutylene gas,17 which is a problem at a pilot plant scale, and utilized tert-butylating agent tert-butyl 2,2,2-trichloroacetimidate (TBTA) instead. In fewer than two months, tens of kilograms of stereochemically pure S- and R-enantiomers with a cost of less than $4 per gram were produced in a greener way than previous syntheses. Following the protocol we developed previously,11 the Bucherer–Bergs reaction converted 2a and 2b each into a mixture of diastereomeric hydantoins with a roughly 5:1 ratio of 2S,4S and 2S,4R stereoisomers for 2a. A large-scale flash chromatography system was utilized using a methylene chloride/isopropanol gradient to separate ∼200 g of crude hydantoin diastereomers in one loading. A solvent reclamation system was used to recycle the methylene chloride. Each isolated, stereochemically pure hydantoin product was then hydrolyzed to afford the four optically pure bis-amino acids (3a–d) as previously reported.11 The detailed multikilogram-scale synthesis is described in the Supporting Information.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Cbz Building Blocks.

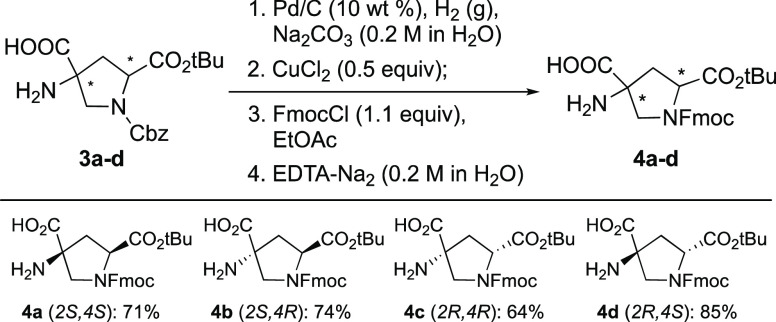

Because the Fmoc group is sensitive to base, the Fmoc protection of the building blocks needs to take place after hydrolysis of the hydantoin and the removal of the Cbz group. Inspired by the selective ω-amino protection of lysine,18 we have developed an efficient synthesis to install the Fmoc group on the proline nitrogen. It relies on the formation of a dimeric Cu(II) complex containing two carboxylic acids and two α-amino groups, which temporarily blocks the primary amino group. The carboxylic acid in position C2 was protected by a tert-butyl group, which prevents it from forming a complex with copper together with the amine in the C1 position. Thus, the free primary amine and carboxylic acid in the C4 position were blocked by the formation of a complex with Cu2+. The proline nitrogen in the building block was then protected with Fmoc protecting reagents such as Fmoc-Cl and Fmoc-OSu. The copper complex was then dissociated by a strong chelating agent in the final stage of the exchange. This strategy was applied to the four bis-amino acid stereoisomers (3a–d) (see Scheme 2). Cbz deprotection was performed by hydrogenolysis with Pd/C in a Na2CO3 aqueous solution. The product was used without purification in the following Cu(II) complexation step. Half of an equivalent of CuCl2 was added directly to the suspension to form a complex with the free amine and the carboxylic acid at position C4 of the bis-amino acid, providing a dark blue solution mixed with Pd/C powder. Under the Schotten–Baumann reaction conditions, a slight excess of Fmoc-Cl in EtOAc was added dropwise to the aqueous slurry. This biphasic mixture was vigorously stirred for 2 h before the Pd/C was filtered out using a short Celite plug. The top EtOAc layer turned blue with an intensity much higher than that of the lower aqueous phase, indicating the formation of the Fmoc-protected Cu complex, which resided in the organic phase due to its reduced polarity. The impurities in the aqueous phase were removed with a separation funnel. The collected organic phase was stirred with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) aqueous solution to remove Cu2+. After 12 h, the blue color was fully transferred from the organic phase to the aqueous phase, suggesting the migration of Cu2+ to the latter. Once the Fmoc-protected bis-amino acid building blocks 4a–d were released from the copper complex, they precipitated from the biphasic system to form a white crystalline powder, as shown in Figure S1. Pure monoprotected solid products 4a–d were then separated by vacuum filtration; small amounts of unreactive starting materials and impurities remained in the yellowish EtOAc phase, and the Cu-EDTA byproduct remained in the blue aqueous phase. This four-step procedure involves no chromatography.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Fmoc Building Blocks.

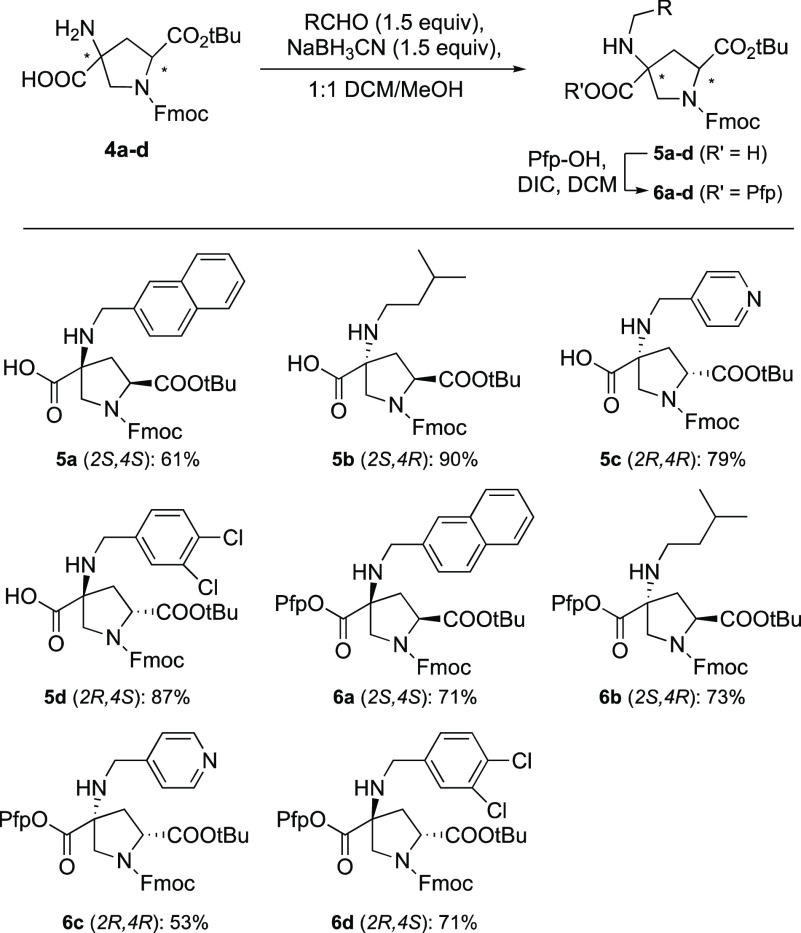

Prior to solid-phase assembly, reductive alkylation was used to incorporate various functional groups into the building blocks, by treating them with the corresponding aldehydes and mild reducing agent NaBH3CN. This is an advantageous feature of spiroligomer synthesis when a functional group chosen from a large set of aldehydes can be installed in the stereochemically pure building blocks to form a measured amount of each monomer for solid-phase synthesis of spiroligomers. Each Fmoc bis-amino acid diastereomer was alkylated with a different functional group to obtain functionalized building blocks 5a–d (see Scheme 3). The four side chains were selected to represent a broad range of functionalities, including alkyl, fused aromatic, heterocyclic, and aryl halide groups. For the functionalization and Pfp ester activation of the Fmoc building block, we found that the previous methods used for pNZ, Boc, and Cbz building blocks are compatible with the new Fmoc building blocks.12,19 By adding DCM with methanol in a 1:1 ratio, we can dissolve 2S,4R and 2R,4S diastereomers to improve the efficiency of reductive alkylation. Solid loading the crude slurry onto Celite with the help of a large amount of methanol and normal-phase chromatography at 0–20% methanol in a DCM gradient was found to be efficient for purifying the functionalized bis-amino acids, with a yield ranging from 61% to 90%. Consistent with previous findings, the functionalized secondary amine on the quaternary center of each building block is so sterically hindered that it does not couple at any appreciable rate to activated esters.20 Therefore, it can be used as a monomer for solid-phase synthesis without protecting the secondary amine on 5a–d. Previously, we observed dimerization of the building blocks using traditional in situ activation coupling strategies.20 Dimerization is minimized using pentafluorophenol (Pfp-OH) to preactivate the monomers and obtain bench-stable building blocks 6a–d as shown in Scheme 3.12 In the coupling step, the Pfp esters of the building blocks can be added directly to the amine on a solid support to avoid the formation of symmetric dimers. Each monomer was purified by normal-phase column chromatography at 0–50% hexane/EtOAc and stored at −20 °C until needed.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Functionalized Building Blocks and Pfp Esters.

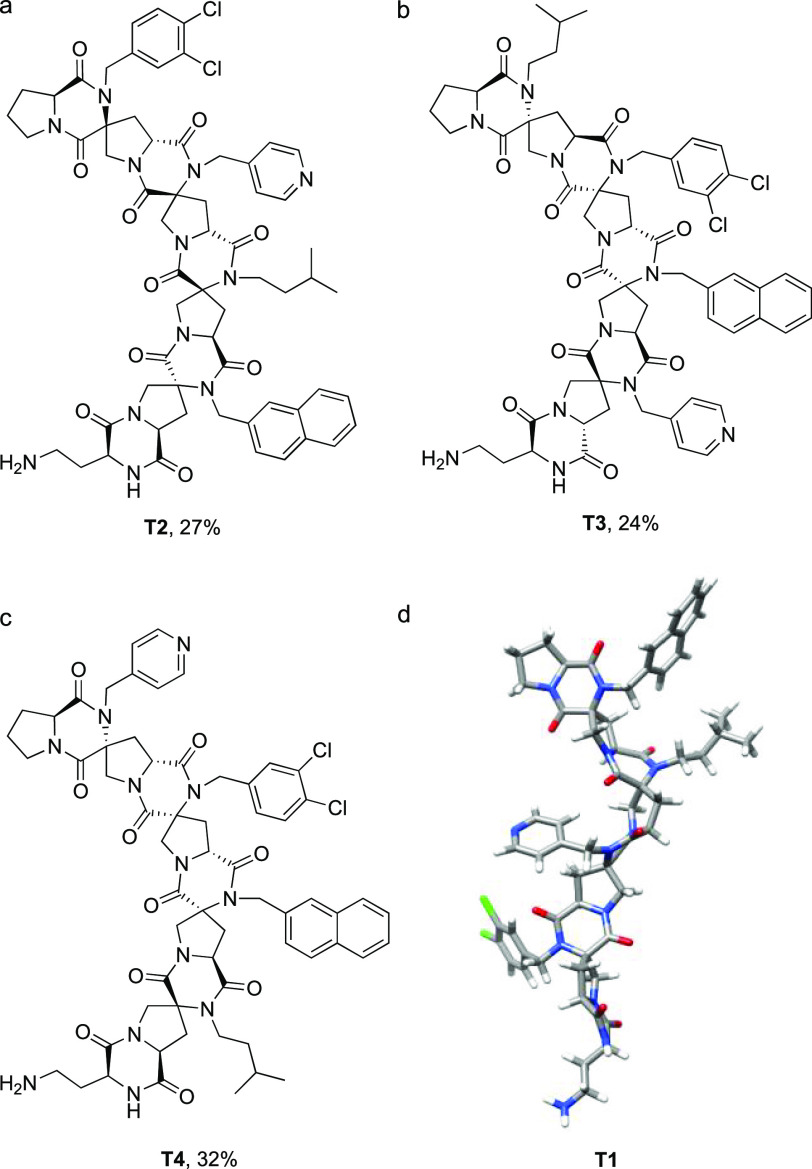

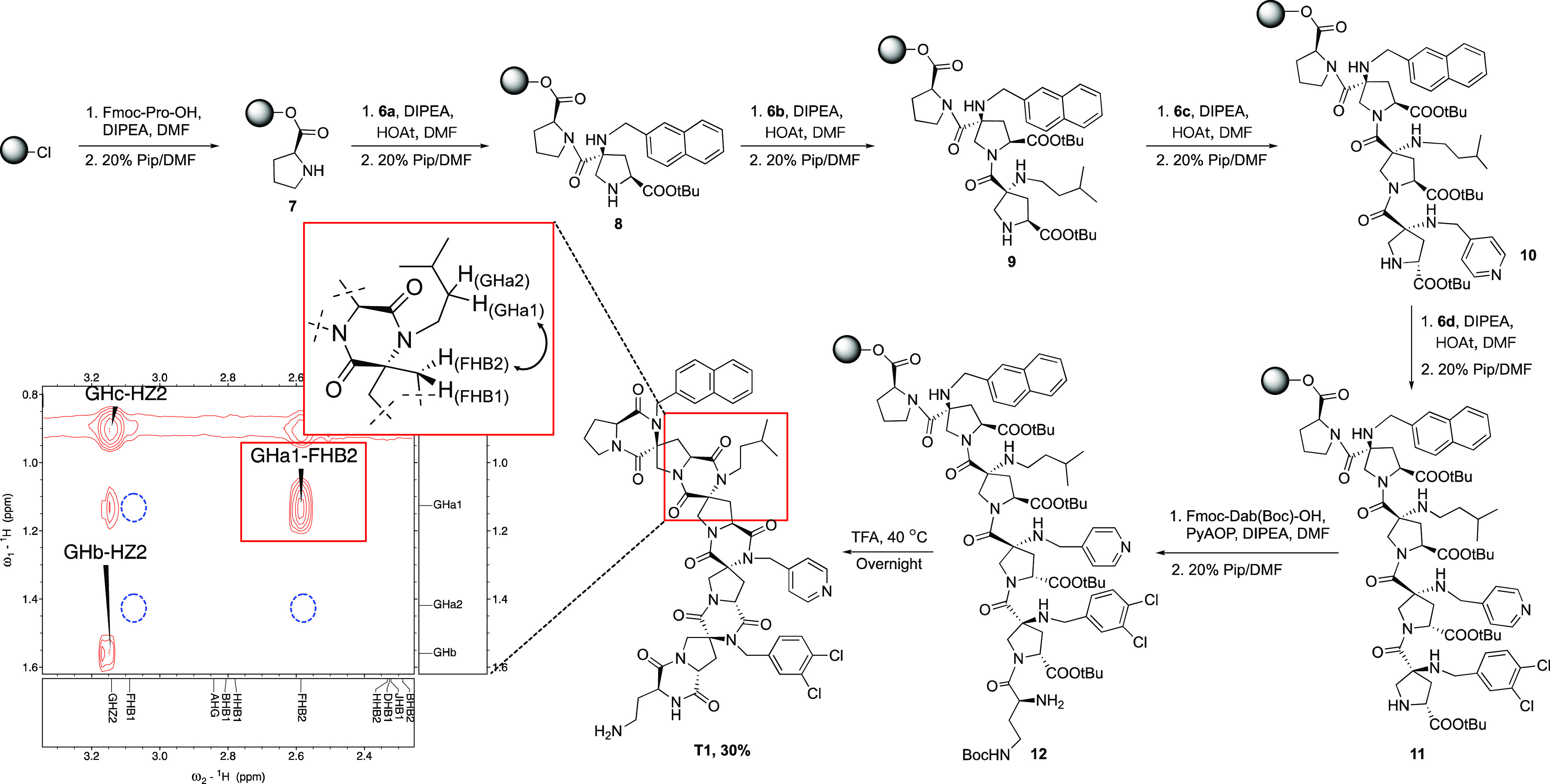

Highly functionalized spiroligomers were assembled through solid-phase synthesis with the four stereoisomers of building blocks 6a–d on a semiautomated microwave peptide synthesizer. As shown in Scheme 4, l-proline was first loaded onto 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin using N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), followed by deprotection of the Fmoc group to generate 7. The second residue, Pfp ester 6a, was coupled using a similar HOAt/DIPEA protocol developed for the pNZ building blocks.12 After optimization, we discovered that 2 equiv of the building block was sufficient to complete the coupling at 50 °C for 1 h in the presence of 4 equiv of HOAt and 8 equiv of DIPEA. Excess base was used to balance the acidity of excess HOAt, which could prematurely cleave the extremely sensitive chloro-trityl linker. Coupling of building block 6b to the resin was followed by Fmoc removal to obtain 9. The coupling of the next bis-amino acid 6c was followed by the removal of the Fmoc group to afford 10. This process was repeated for the installation of the last building block 6d, forming compound 11. The sequence was capped by Fmoc-Dab(Boc)-OH to provide 12, which was liberated from the solid phase by exposure to TFA. After the TFA solution containing cleaved product 12 had been heated at 40 °C overnight, the DKPs in tetramer T1 were fully formed presumably through an acid-catalyzed condensation. No significant byproduct was observed via crude HPLC (see Figure S2). The final yield of T1 was 30% after preparative HPLC based on the maximum loading of resin. To demonstrate the generality of this synthetic approach, three other tetramers, T2–T4, were synthesized by altering the position of the building blocks (see Figure 1). The composition of T1–T4 was verified by high-resolution mass spectrometry (QTOF MS) (see Figures S3–S6). Two-dimensional NMR experiments [double quantum filtered correlation spectroscopy (DQF-COSY), heteronuclear single quantum coherence spectroscopy (HSQC), heteronuclear multiple bond correlation spectroscopy (HMBC), and heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence (HMQC)] in DMSO-d6 were carried out and used to assign the 1H and 13C resonances with the software package SPARKY. The complete lists of chemical shifts can be found in the Supporting Information. The expected connectivity was confirmed with the cross peaks from the correlations between neighboring building blocks in a band selective HMBC spectrum [see the two-dimensional (2D) NMR spectra in the Supporting Information]. Rotating frame Overhauser effect spectroscopy (ROESY) correlations were used to identify the relative stereochemistry of C2 and C4 hydrogens in each pyrrolidine, and they confirmed their configurations relative to the configuration of C1 on each building block. Furthermore, all side chains have hydrogens that show ROESY correlations with backbone hydrogens, and they are consistent with the side chain having a preferred orientation, although we are not able to determine their exact conformations. For example, as shown in Scheme 4, one of the β protons, FHB2, below the plane of the second bis-amino acid proline ring, has a strong ROESY correlation with GHa1 (solid red box), which is one of the methylene protons in the side group of the neighboring building block. On the contrary, no correlation can be found between GHa1 and FHB1, GHa2 and FHB1, or GHa2 and FHB2 [expected where blue dashed circles are drawn (Scheme 4)]. This suggests that the rotation of side chains is restricted by the interaction with the rigid backbones, which meets the expectation of well-defined three-dimensiona structures. The energy-minimized structure of T1 is shown in Figure 1d. The Supporting Information includes the complete ROESY spectral assignments and correlations of T1–T4.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of Functionalized Spiroligomer T1 with Selected ROESY Correlation and Modeled Structure.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of spiroligomers (a) T2, (b) T3, (c) and T4 and (d) modeled structure of T1 based on ROESY correlations and GAFF energy minimization by CANDO (see the Supporting Information for details).

In summary, we have scaled up the synthesis of bis-amino acid intermediates to tens of kilograms. We successfully used a Cu2+ complexation strategy to selectively incorporate an Fmoc group in a four-step, one-pot process with no chromatography with excellent yield and purity. Using these monomers, we synthesized four spiroligomers on a solid support with four different building blocks containing unique functional groups and stereochemistry. This work lays the foundation for the reliable and automated assembly of highly functionalized spiroligomer libraries.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Takuya Mizukami at Fox Chase Cancer Center for performing 2D NMR experiments. The authors thank Dr. Justin D. Northrup and Dr. Conrad T. Pfeiffer at ThirdLaw Molecular LLC for performing QTOF-LCMS and prep-HPLC. The scale-up of the first three steps of the bis-amino acids was 50% supported by the Advanced Manufacturing Office of the Department of Energy (Grant DE-EE0008321) and 50% supported by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency of the Department of Defense (HDTRA1-16-1-0047). The content of the information does not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the federal government, and no official endorsement should be inferred. The authors also thank WuXi Apptec for their work in developing the tens of kilogram synthesis of intermediates 2a and 2b. The molecular graphic of T1 (Figure 1d) was generated using UCSF Chimera, developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, with support from National Institutes of Health Grant P41-GM103311.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.orglett.2c01295.

Experimental procedures and characterizations of compounds 1–6 and tetramers T1–T4, details about the energy-minimized structure of T1, and 2D NMR spectra and assignments of T1–T4 (PDF)

FAIR data, including the primary NMR FID files, for compounds 4a–d, 5a–d, and 6a–d (ZIP)

FAIR data, including the primary NMR FID files, for compound T1 (ZIP)

FAIR data, including the primary NMR FID files, for compound T2 (ZIP)

FAIR data, including the primary NMR FID files, for compound T3 (ZIP)

FAIR data, including the primary NMR FID files, for compound T4 (ZIP)

Author Present Address

‡ S.T.: Wenzhou Institute, University of Chinese Academy of Science (Wenzhou Institute of Biomaterials & Engineering), Wenzhou, Zhejiang 325000, P. R. China

Author Present Address

§ S.C.: Adesis. Inc., 27 McCullough Dr., New Castle, DE 19720.

Author Contributions

† Y.X. and D.L. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): C.S. is Acting President, Chief Scientific Officer, and Founder of ThirdLaw Molecular LLC, a company that is commercializing this technology.

Supplementary Material

References

- Gutteridge A.; Thornton J. M. Understanding nature’s catalytic toolkit. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005, 30 (11), 622–629. 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenci E.; Trabocchi A. Peptidomimetic toolbox for drug discovery. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49 (11), 3262–3277. 10.1039/D0CS00102C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz J.-F.; Ouchi M.; Liu D. R.; Sawamoto M. Sequence-Controlled Polymers. Science 2013, 341 (6146), 1238149. 10.1126/science.1238149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hill D. J.; Mio M. J.; Prince R. B.; Hughes T. S.; Moore J. S. A Field Guide to Foldamers. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101 (12), 3893–4012. 10.1021/cr990120t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ashton P. R.; Brown G. R.; Isaacs N. S.; Giuffrida D.; Kohnke F. H.; Mathias J. P.; Slawin A. M.; Smith D. R.; Stoddart J. F.; Williams D. J. Molecular LEGO. 1. Substrate-directed synthesis via stereoregular Diels-Alder oligomerizations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114 (16), 6330–6353. 10.1021/ja00042a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Qiu Y.; Chen H.; Feng Y.; Schott M. E.; Stoddart J. F. Stitching up the Belt[n]arenes. Chem. 2020, 6 (4), 826–829. 10.1016/j.chempr.2020.03.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saito F.; Trapp N.; Bode J. W. Iterative Assembly of Polycyclic Saturated Heterocycles from Monomeric Building Blocks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (13), 5544–5554. 10.1021/jacs.9b01537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafmeister C. E.; Brown Z. Z.; Gupta S. Shape-Programmable Macromolecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41 (10), 1387–1398. 10.1021/ar700283y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Parker M. F. L.; Osuna S.; Bollot G.; Vaddypally S.; Zdilla M. J.; Houk K. N.; Schafmeister C. E. Acceleration of an Aromatic Claisen Rearrangement via a Designed Spiroligozyme Catalyst that Mimics the Ketosteroid Isomerase Catalytic Dyad. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (10), 3817–3827. 10.1021/ja409214c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhao Q.; Lam Y.-h.; Kheirabadi M.; Xu C.; Houk K. N.; Schafmeister C. E. Hydrophobic Substituent Effects on Proline Catalysis of Aldol Reactions in Water. Journal of Organic Chemistry 2012, 77 (10), 4784–4792. 10.1021/jo300569c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kheirabadi M.; Çelebi-Ölçüm N.; Parker M. F. L.; Zhao Q.; Kiss G.; Houk K. N.; Schafmeister C. E. Spiroligozymes for Transesterifications: Design and Relationship of Structure to Activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (44), 18345–18353. 10.1021/ja3069648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Northrup J. D.; Wiener J. A.; Hurley M. F. D.; Hou C. F. D.; Keller T. M.; Baxter R. H. G.; Zdilla M. J.; Voelz V. A.; Schafmeister C. E. Metal-Binding Q-Proline Macrocycles. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86 (6), 4867–4876. 10.1021/acs.joc.1c00116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Vaddypally S.; Xu C. S.; Zhao S. Z.; Fan Y. F.; Schafmeister C. E.; Zdilla M. J. Architectural Spiroligomers Designed for Binuclear Metal Complex Templating. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52 (11), 6457–6463. 10.1021/ic4003498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zhao Q. Q.; Schafmeister C. E. Synthesis of Spiroligomer-Containing Macrocycles. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80 (18), 8968–8978. 10.1021/acs.joc.5b01109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown Z. Z.; Akula K.; Arzumanyan A.; Alleva J.; Jackson M.; Bichenkov E.; Sheffield J. B.; Feitelson M. A.; Schafmeister C. E. A Spiroligomer alpha-Helix Mimic That Binds HDM2, Penetrates Human Cells and Stabilizes HDM2 in Cell Culture. PLoS One 2012, 7 (10), e45948. 10.1371/journal.pone.0045948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chepyshev S. V.; Schafmeister C. E.. Development of novel spiroligomer carbohydrate binding molecules. Rocky Mountain Regional Meeting, Fort Collins, CO, 2020.

- Cheong J. E.; Pfeiffer C. T.; Northrup J. D.; Parker M. F. L.; Schafmeister C. E. An improved, scalable synthesis of bis-amino acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57 (44), 4882–4884. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.09.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer C. T.; Northrup J. D.; Cheong J. E.; Pham M. A.; Parker M. F. L.; Schafmeister C. E. Utilization of the p-nitrobenzyloxycarbonyl (pNZ) amine protecting group and pentafluorophenyl (Pfp) esters for the solid phase synthesis of spiroligomers. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59 (30), 2884–2888. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2018.05.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt R.; White P.; Offer J. Advances in Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis. Journal of Peptide Science 2016, 22 (1), 4–27. 10.1002/psc.2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ieronymaki M.; Androutsou M. E.; Pantelia A.; Friligou I.; Crisp M.; High K.; Penkman K.; Gatos D.; Tselios T. Use of the 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin for microwave-assisted solid phase peptide synthesis. Biopolymers 2015, 104 (5), 506–514. 10.1002/bip.22710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathopoulos P.; Papas S.; Tsikaris V. C-terminal N-alkylated peptide amides resulting from the linker decomposition of the Rink amide resin. A new cleavage mixture prevents their formation. Journal of Peptide Science 2006, 12 (3), 227–232. 10.1002/psc.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron S.; Dugger R. W.; Ruggeri S. G.; Ragan J. A.; Ripin D. H. B. Large-Scale Oxidations in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106 (7), 2943–2989. 10.1021/cr040679f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. W.; Hageman D. L.; Wright A. S.; McClure L. D. Convenient preparations of t-butyl esters and ethers from t-butanol. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38 (42), 7345–7348. 10.1016/S0040-4039(97)01792-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malkar N. B.; Fields G. B. Synthesis of N-alpha-(fluoren-9-ylmethoxycarbonyl)-N-epsilon- (7-methoxycoumarin-4-yl)acetyl -L-lysine for use in solid-phase synthesis of fluorogenic substrates. Letters in Peptide Science 2000, 7 (5), 263–267. 10.1023/A:1011863616393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown Z. Z.; Alleva J.; Schafmeister C. E. Solid-Phase Synthesis of Functionalized Bis-Peptides. Biopolymers 2011, 96 (5), 578–585. 10.1002/bip.21591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown Z. Z.; Schafmeister C. E. Exploiting an Inherent Neighboring Group Effect of alpha-Amino Acids To Synthesize Extremely Hindered Dipeptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130 (44), 14382–14383. 10.1021/ja806063k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.