Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a population of non-hematopoietic and self-renewing cells characterized by the potential to differentiate into different cell subtypes. MSCs have interesting features which have attracted a lot of attention in various clinical investigations. Some basic features of MSCs are including the weak immunogenicity (absence of MHC-II and costimulatory ligands accompanied by the low expression of MHC-I) and the potential of plasticity and multi-organ homing via expressing related surface molecules. MSCs by immunomodulatory effects could also ameliorate several immune-pathological conditions like graft-versus-host diseases (GVHD). The efficacy and potency of MSCs are the main objections of MSCs therapeutic applications. It suggested that improving the MSC immunosuppressive characteristic via genetic engineering to produce therapeutic molecules consider as one of the best options for this purpose. In this review, we explain the functions, immunologic properties, and clinical applications of MSCs to discuss the beneficial application of genetically modified MSCs in GVHD.

Keywords: mesenchymal stem cell, GVHD, immunotherapy, gene therapy

Mesenchymal Stem cells (MSCs) by immunomodulatory effects can ameliorate several immune related disorders such as graft-versus-host diseases (GVHD). The efficacy and potency of MSCs are the main objections of MSCs therapeutic applications. MSCs can be genetically modified to improve clinical therapeutic advantages via production of therapeutic molecules including target-associated cytokines and other modulatory molecules with notable immunosuppressive characteristics without interfering with their differentiation and self-regeneration manners.

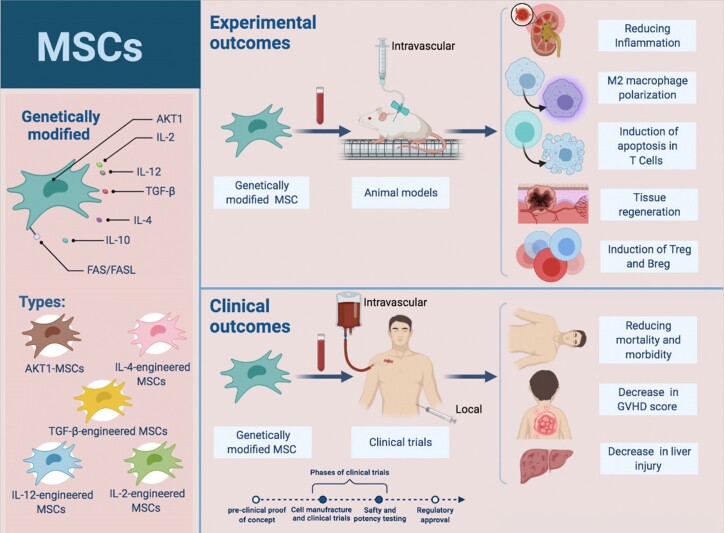

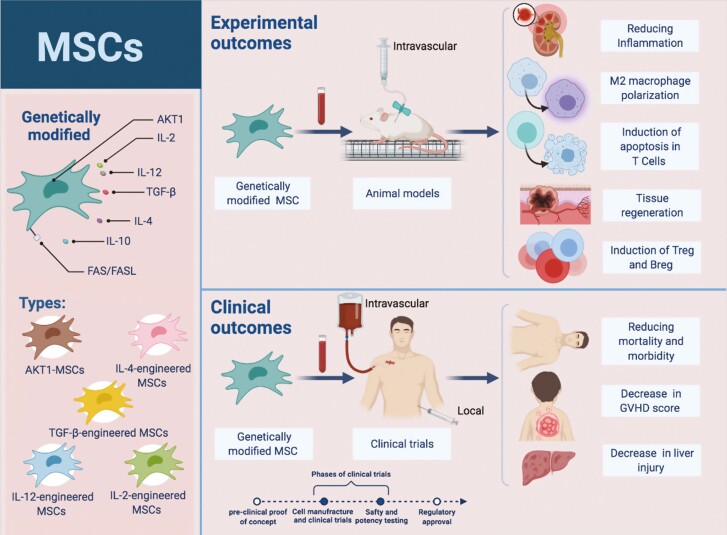

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) represent a population of non-hematopoietic, self-renewing cells, plastic-adherent and characterized by differentiating capacity into adipocytes, chondrocytes, and osteoblasts under in vitro and in vivo conditions [1–3]. The first description of these multipotent progenitors as term of MSC was applied by Caplan and colleagues in 1991 [4]. MSCs were originally isolated from bone marrow (BM); however, their presence has been demonstrated in several other tissues including adipose tissue (AT), umbilical cord blood (UCB), muscle, brain, spleen, kidney, lung, thymus, pancreas, and dental pulp [1, 5]. Nowadays, due to the considerable immunomodulatory and regenerative properties of MCSs, support of hematopoiesis, and tissue repair through secretion of soluble factors and cell-to-cell contact, they render a suitable therapeutic option for transplantation in immune-mediated disorders [4, 6]. The considerable beneficial characteristics of MSCs are metastasis everywhere in the body, and low immunogenicity due to the absence of HLA-II and other costimulatory receptors such as CD80 and CD86 and CD40 [2, 5]. Current development in MSC-based cell therapies has revealed a considerable potential to relieve several immune-based diseases, including diabetes, Crohn’s disease, cancers, multiple sclerosis (MS), and rheumatoid arthritis [4, 5]. In addition, MSCs have been widely being investigated in clinical trials of different conditions, including graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) following bone marrow transplantation (BMT), orthopedic diseases, cardiovascular disorders, liver diseases, cancers, and autoimmune diseases [7].

In addition, animal experiments and clinical trials demonstrated MSCs successfully are applied in hematological disease therapy [4]. In this review, we describe the function and immunologic properties of MSCs to discuss the MSCs’ clinical application in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and MSCs application in GVHD. Finally, the last section of this review focused on genetically modified MSCs application in GVHD. According to some challenges in MSCs therapy efficacy, MSCs have been genetically engineered in vitro or ex vivo and next used for therapeutic prospects in vivo to produce target therapeutic molecules and improve therapeutic efficacy.

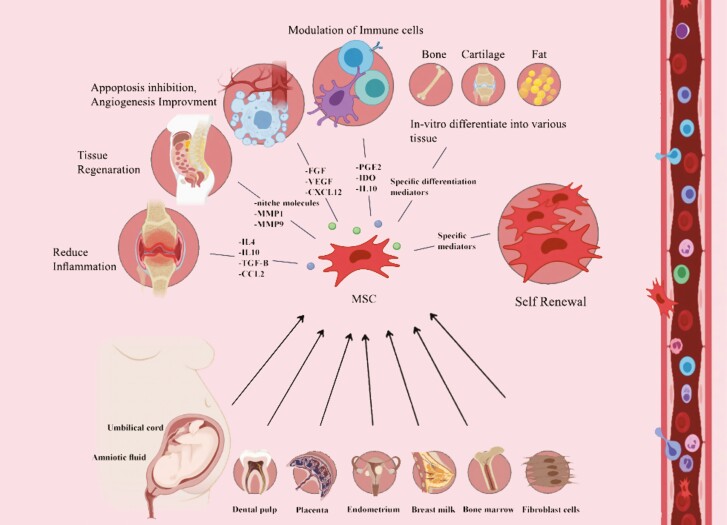

Function of MSCs

BM is considered the primary region of physiological function studies of endogenous MSCs as the main source of these cells. MSCs also play a role in modulating immune or inflammation response and repairing tissue through the regeneration capacity of these cells [4]. The first and foremost functions of MSCs are their differentiation capacity into several cell types such as bone, cartilage, and adipocytes [8], and recently their differentiating ability into all three germ layers has been demonstrated [4, 9–12]. The other prominent proposed MSCs application is in regenerative medicine through this plasticity property of MSCs toward specialized cells of mesenchymal tissue (including adipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes) [1]. This field of MSC investigation and possible clinical utilization has attracted so much attention these days.

The second function of MSCs is migration capacity to the inflammation regions, presumably based on inflammation degree and various disease conditions [4, 13–15]. It is reported that MSCs could primarily and quickly home to the lungs, subsequently migrate into other GVHD-targeted organs (i.e. small intestine, esophagus, liver, stomach, and large intestine) [4, 16]. Finally, it revealed that MSCs co-localized with HSCs in the BM niche and participate in hematopoiesis maintenance through developing and preserving the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niche [17] and secrete factors to recruit HSCs [1, 4, 18].

Collectively, that is demonstrated allogeneic MSCs might also engraft and differentiate in humans despite the major histocompatibility limitations even in immunocompetent recipients [19]. MSCs like hematopoietic stem cells have plasticity potential and multi-organ homing through expressing CD90 and CD73 surface molecules (absence of CD11b, CD14, CD19, CD34, CD45, CD79a, and HLA-DR) [8, 20].

Immunological properties of MSCs

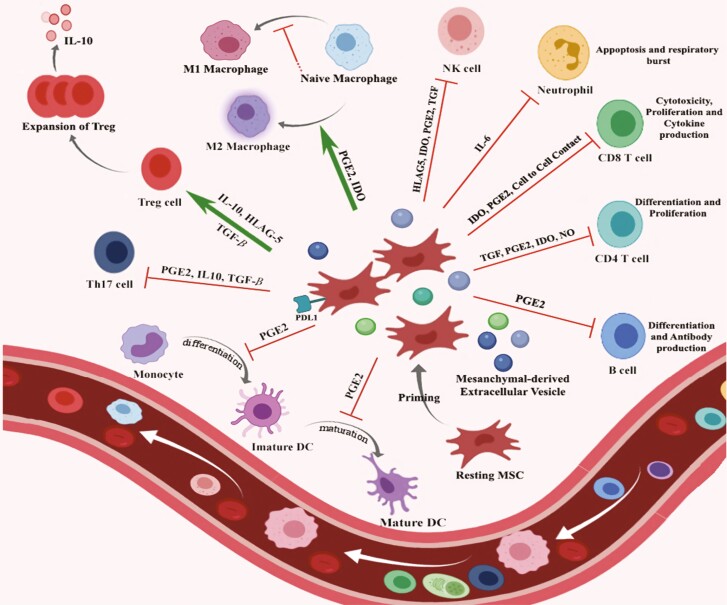

The immunomodulatory characteristic of MSCs via central (Fig. 1) and peripheral (Fig. 2) immune compartments is one of the most attractive findings of recent investigations [6, 21, 22]. MSCs modulate the immune response through direct cell-to-cell contact mechanisms and indirectly via secretion of several soluble molecules. As discussed before, MSCs probably are weakly immunogenic due to the absence of MHC-II and costimulatory ligands CD80 and CD86 and CD40, besides their low expression level of MHC-I. MSCs through cooperating with different immune cells (e.g. T-cell interaction) via expression of numerous adhesion molecules (i.e. lymphocyte function-associated antigen-3, intercellular cell adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, and vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1) and producing soluble factors in various microenvironments regulate both innate and adaptive immune systems [4, 23]. Recent in vivo investigation reported that MSCs enhance anti-inflammatory and regenerative effects through secreting cytokines and regulatory mediators (indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), nitric oxide, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), the highly anti-inflammatory molecule tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α-induced gene/protein 6 (TSG-6), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and interleukin (IL)-10 [24]) that result in promoting endogenous tissue repair and replacement of the injured tissues [25]. Both in vitro and in vivo investigations have shown that MSCs exert immunomodulatory effects through the secretion of these factors which are contributed in several immune-pathological conditions in the same manner, such as type 1 diabetes and GVHD [20, 26, 27].

Figure 1.

immunomodulatory effects of MSC on the components of the immune system. The cellular characteristics of MSCs are important for their therapeutic uses. MSCs apply immunomodulatory effects on central and peripheral immune compartments through producing many immunomodulatory molecules such as TGF-β, HLA-G5, IDO, and PGE2 by the effect on M2 macrophages polarization in inflammatory conditions. MSCs also modulate central immune compartments through promoting T-cells maturation, repairing damaged thymus, inducing the proliferation of natural Tregs, and stimulation of thymocytes differentiation.

Figure 2.

characteristics of MSCs and their functional principle. MSCs have been isolated from different tissues. They exhibit a high self-renewal capacity, multilineage differentiation potential, and immunomodulatory properties by secreting multiple soluble factors. Thereby, MSCs promote tissue regeneration and neoangiogenesis, reduce inflammation, and prevent fibrosis and apoptosis. Further, these cells stimulate local stem cells to develop new tissue.

Additional investigations described that besides suppression of T-cell activation and proliferation, MSCs could regulate helper T (Th) cells differentiation [23, 28]. MSCs also suppress alloreactive natural killer (NK) cell proliferation and maturation as central players in innate immune responses [1, 2, 29–31] through secretion of IDO and PGE2 [32, 33]. Moreover, MSCs may also increase the regulatory T cells (Tregs) induction as a central character for the maintenance of peripheral immune tolerance (as shown in Fig. 1) [1, 34]. MSCs can modulate the functions of effector immune cells by interactions of the cell to cell through the PD-1/PDL-1 and HLA-G1 molecules. C–C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) acts as a potent monocyte chemoattractant and is a chemokine classically involved in the recruitment of monocytes/macrophages. After phagocytosis of MSCs, monocytes enhance their phagocytic efficiency and differentiation to M2 type immunosuppressive phenotype via upregulating the CD206, TGF-β, and IL-10 expression [35, 36]. MSCs could also suppress the differentiation of monocytes to dendritic cells (DCs) and turn them into a more tolerogenic phenotype (decreasing the CD80, CD83, CD1a and HLA-DR expression, and IL-12 production) [37]. These primed monocytes after MSC phagocytosis, increase CD4+CD25hi Foxp3+Treg formation in vitro [38]. It is proposed that the regulatory CD25 + cells elevation is one of the immune modulation mechanisms by MSCs [39].

Moreover, in vivo treatment under active inflammatory conditions by milieu, MSCs obtain most clearly the required activating signals or “licensing” to take a full anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive actions [35]. This phenomenon is defined as increased expression of MHC class I/class II, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 adhesion molecules, as well as hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), IL-6, IL-8, PGE2, IDO, PDL-1, and COX2. In presence of both IFN-g and TNF-a, MSCs are completely activated and induce CCR10, CXCR3, CXCL9, and CXCL10 expression [40–46]. All these possible mechanisms have been previously reviewed [40, 43, 45, 47, 48].

MSCs play an inhibitory role on cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) by suppressing the proliferation of CD8+ T cells. The autologous and allogeneic effector cells could also represent the MSC-induced suppression effects [25, 49]. Many studies demonstrated that the addition of MSCs at the early phase of mixed lymphocyte culture leads to inhibition of the cytotoxic action of CTLs against target cells [32, 50]. In addition, MSCs can render a transient cell cycle arrest of B cells in the G0/G1 phase, which repress the maturation and proliferation of B cells and subsequently the immunoglobulin (Ig) secretion [1, 51]. MSCs repress the B cells differentiation due to the impaired IgG, IgM, and IgA production. Recent studies have shown that MSCs can inhibit the chemotactic capacity of the B cells in response to chemokines [32, 52]. Recently, a study reported that IL-10 secreted by MSCs considerably enhanced CD5+ regulatory B cells (Bregs) development [4, 53]. Interestingly, current evidence demonstrates MSCs act as a “sensor” of inflammation and can adopt a wide spectrum of functional phenotypes that range from the proinflammatory phenotype, to the anti-inflammatory phenotype both in vitro and in vivo through interfering with adaptive and innate immune responses [4, 54]. The deep understanding of the different dimensions of MSCs functions presents the innovative ideas for MSCs-based cellular therapies and their possible usage in stem cell treatment of severe acute GVHD.

Clinical applications of MSCs in HSCT

The immunomodulatory, plasticity, and migration capacity of MSC proposes a promising novel treatment approach for development of stem cell-mediated gene therapy platforms [1, 55]. The BM, placenta, cord blood products, amniotic fluid, Wharton’s jelly, AT, and other tissues are common sources of MSCs. MSCs isolation from adult tissues is easy procedure and the major benefit is that isolation strategies do not need ethical approval. The effectiveness of isolation of MSCs from the adipose and BM tissues in comparison with ATs is 100%, although the differentiation capability is identical among MSCs obtained from various sources.

The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of MSCs are the main clinical significance of MSCs. MSCs can repress cells via MHC-independent identity among donor and recipient considerably because of low HLA-II and other co-stimulatory molecules expression. Some of immunosuppressive effects of MSCs require cell-to-cell contact, whereas others are dependent on soluble factors such as HGF, TGF-β, nitric oxide, and IDO.

The immunomodulatory properties of MSCs make these cells a novel promising therapeutic option throughout or after transplantation since MSC co-transplantation can reduce the toxicity following different conditioning regimens while inducing long-term hematopoietic engraftment and reduce the GVHD severity and incidence. The numerous clinical trials show the co-transplantation of MSCs with HSCs could improve the engraftment levels, although their action mechanisms remain unknown [56].

The traditional therapeutic method in hematologic malignancies is allogeneic HSCT. In allo-HSCT, T cells existing in the donor BM might stimulate an immune responses against the recipient, whereby rejecting the transplanted tissue. Corticosteroids are the most widely used immunosuppression drugs for decreasing GVHD occurrence, but these agents enhance the chance of acquiring infections [55, 57, 58]. In this way, MSCs through the beneficial properties are extensively utilized in hematological related complications, particularly in HSCT, which principally promote HSCs engraftment, improvement of engraftment failure and poor graft function and GVHD preventing [4].

MSCs can also promote hematopoiesis through various mechanisms. In HSCT candidates, the hematopoietic microenvironment is usually impaired via chemotherapy, irradiation, and malignant hematological disorders [59]. MSCs as a principal component of the BM microenvironment contribute to reconstitute the damaged stroma and produce a range of hematopoietic cytokines (i.e. IL-8, IL-11, IL-6, IL-7, stem cell factor, and Flt-3 ligand) to improve self-regeneration and differentiation of HSCs [4, 18, 60]. In addition, MSCs can promote hematopoiesis through the inflammatory microenvironment and T-cell subtypes modulation and inducing Tregs development [4, 59].

Mesenchymal stem cells and GVHD

GVHD remains the main cause of non–relapse-related mortality and morbidity and is considered as a common and life-threatening complication restricting the extensive application of allo-HSCT [4, 58]. GVHD developed from distinguishing between self and non-self that is one of the main functions of the immune system. During the development of GVHD, non-identical donor (graft) immune cells which have been transplanted into the recipient as host, recognize the recipient (host) cells as “foreign”, so beginning a graft-versus-host reaction [61]. GVHD is basically categorized to acute (aGVHD) and chronic (cGVHD) according to time of onset after allo-HSCT as aGVHD occurred at <100 days and cGVHD occurred at >100 days. Currently, GVHD is defined based on a novel scoring system according to the clinical symptoms and signs and pathogenesis [58, 62–65]. aGVHD affects the liver, the skin, and the gastrointestinal tract, and clinical signs include gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea and abdominal cramps, maculopapular erythema, and cholestatic hepatitis, while cGVHD can essentially affect any organ or tissue [58, 62, 66].

According to the immunosuppressive functions of MSCs, these cells are successfully applied in patients undergoing hemopoietic cell transplantation to ameliorate GVHD [67]. Recent studies in the field of GVHD treatment with MSCs were summarized in Table 1. It is demonstrated that MSCs escape immune recognition by circulating T cells [68]. Therefore, allo-MSCs transplantation is considered to correlate with a decreased transplant rejection risk, presenting the idea of an allo-MSC preparing to be a “one-size-fits all, off-the-shelf “ therapy [1, 69]. The initial efficient MSCs usage in severe aGvHD treatment was reported in 2004 and numerous clinical and preclinical investigations have been conducted within [67]. These studies showed controversial results because of heterogeneity into clinical treatment planning (including concentration of MSC, administration route, and timing and number of doses) and other factors, such as tissue source of MSC and recipient inflammatory status [70–72]. Preclinical data from mouse models also demonstrated similar controversial results and side effects (pulmonary embolization) [62, 73, 74].

Table 1.

experimental and clinical outcomes of MSCs in GVHD

| MSCs source | Stage of disorder | Clinical outcome | Year | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | Grad IV therapy-resistant severe acute GVHD of the gut and liver | Striking immunosuppressive effect in vivo | 2004 | [67] |

| BM | Hematologic malignancy patients | Incidence percentage of acute GVHD in patients ↓ | 2005 | [75] |

| Prochymal® (MSC-derived from unrelated volunteer adult donors) | Steroid-refractory acute GVHD (SR-GVHD) | Prochymal vs. placebo % in the grades of GVHD: | 2009 | [76] |

| Grade B (22% vs. 26%) | ||||

| Grade C (51% vs. 58%) | ||||

| Grade D (27% vs. 16%) | ||||

| The respective durable complete response (DCR) rates were 35% vs. 30% in the intention-to-treat (ITT) individuals and 40% vs. 28% in the per protocol population | ||||

| GvHD patients affecting all three organs showed overall partial or CRs rate of 63% vs. 0% at day 28 | ||||

| Patients receiving Prochymal demonstrated less liver GVHD progression at weeks 2 and 4 (32% vs. 59% and 37% vs. 65%) respectively | ||||

| BM | cGvHD | More effective for liver, gastrointestinal tract and skin involvement cGVHD patients | 2010 | [77] |

| Keratoconjunctivitis sicca patients demonstrated: | ||||

| Improved clinical symptoms | ||||

| Enhanced ratio of CD8+ CD28−/CD8+ CD28+ T lymphocytes and CD5+ CD19+/CD5− CD19+ B lymphocytes | ||||

| BM | Refractory aGVHD patients | Severity and incidence of chronic GVHD in patients with aGVHD by induction of Tregsandimproving thymic function ↓ | 2015 | [78] |

| The ratio of CD3+CD4+/CD3+CD8+ T cells ↑ | ||||

| The frequencies of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs↑ | ||||

| Signal joint T-cell-receptor excision DNA circles (sjTRECs) levels ↑ | ||||

| BM | Steroid-refractory aGvHD | Not significantly different in OS rate and OR rate to MSCs therapy in patients with steroid-resistant scute GVHD | 2016 | [79] |

| BM(remestemcel-L) | Steroid-refractory aGVHD | Patients with liver involvement: higher overall partial or CR rate (OR) and DCR levels than placebo (29% vs. 5%) | 2020 | [80] |

| Patients with high risk (aGVHD grades C and D): higher OR at day 28 compared with placebo (58% vs. 37%) | ||||

| Pediatric patients: higher OR with MSC infusion than placebo (64% vs. 23%) | ||||

| BM | SR-aGVHD | The 28-day ORratein 157 patients (65.1%), with 34 achieving CR (14.1%) and 123achieving PR(51.3%) | 2020 | [81, 82] |

| Based the OR rate at day +28 on aGVHD grade at baseline: | ||||

| aGVHD grade B: 72.9% | ||||

| aGVHD grade C: 67.1% | ||||

| aGVHD grade D: 60.8% | ||||

| BM | Severe, refractory cGvHD | MSCs therapy efficiency correlated with: | 2020 | [83] |

| Immunological properties of the individual patient (absolute number of B lymphocytes (CD19+ IgD+ CD38low) and the CD31+ CD4 subpopulation) | ||||

| Ability to produce sufficient levels of naive Tregs and naive T cells | ||||

| The clinical effects were correlated with: decreased inflammatory levels of cytokine and chemokines (CXCL10, CXCL2, and CCL2 levels) | ||||

| Skin histology in the responders | ||||

| BM+ MSC+ IFN – γ | GVHD mouse model | Significant decrease of the GVHD incidence | 2021 | [84] |

| Increase of the survival rate |

MSCs have been shown to exhibit various efficacy outcomes for GVHD prophylaxis based on diverse studies [4, 75, 85]. Lazarus et al. reported that co-infusion of MSCs with HSCs resulted in 28% development of acute GVHD in patients compared to 56% in patients receiving only HSCs [75]. The data supported that administration of MSCs for acute GVHD prophylaxis was safe and effective. Although co-transplantation of MSCs with HSCs to a certain extent reduced the incidence and severity of acute GVHD, many researches revealed no significant difference compared with the historical control participants [4].

Moreover, Zhao et al. showed that MSCs could ameliorate acute GVHD through central components of the immune system. MSCs promote reconstruct damaged thymic structure and thymic output function which lead to long-term induction of immune tolerance [4, 78]. MSCs could also support hematopoiesis by modulation of T-cell subtypes and inflammatory microenvironment, which decrease the chance of BM graft rejection [59]. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) play a central role in maintaining peripheral self-tolerance and immunological homeostasis. MSCs can enhance the generation and expansion of Tregs for preventing GVHD [34].

Nevertheless, an American clinical trial assessed the outcome of an industrial-sponsored manufactured allogeneic MSC cells (Prochymal) and determined that these MSCs were failed to achieve a notable development of complete response (CR) rate in patients with steroid-resistant GVHD in comparison to placebo [76, 86]. Various researches in Germany were isolated MSCs from third-party donors and also recorded a negative response (not significantly different in overall response (OR) rate and overall survival (OS) rate) to MSCs therapy in steroid-resistant acute GVHD patients who had a more severe grade of acute GVHD compared to patients without administration of MSCs [79]. A recent meta-analysis including 13 non-randomized studies comprising 336 patients revealed that survival rate at 6 months after MSC administration was 63% with a CR rate of 28%. The age of patients, culture medium of MSC, MSC doses, and time of administration did not effect on survival rate [87].

Another Cochrane-based extended meta-analysis including 12 randomized clinical trials comprising 879 patients analyzed the prophylaxis outcome or treatment with mesenchymal stem cells in acute or chronic GVHD. The data reported that MSCs are not thoroughly confirmed to be an effective treatment, even though several single reports recommend a positive outcome of MSCs [88]. In addition, a phase III, placebo-controlled clinical study reported that the infusion of MSCs derived from BM (Remestemcel-L) did not meet its main end-point (durable complete response (DCR) lasting ≥28 days) [44, 80]. Nevertheless, liver-involved patients receiving at least one cell infusion compared with the placebo control group had a higher value of DCR and overall partial or CR rate to therapy. Patients with high risk who developed grades C and D acute GVHD and pediatric patients showed higher OR rate in remestemcel-L compared with placebo [80].

Furthermore, a phase 3, single-arm, prospective, multicenter trial including 241 children recommends some clinical and survival advantages of MSCs such as improved Day 28 OR rate in children following the failure of conventional therapies with a median of 11 MSC infusions (2 × 106 cells per kg) [37, 81, 82]. The biologics license application of Mesoblasts company for pediatric steroid refractory acute GVHD (SR-aGvHD) treatment with MSCs was declined in October 2020 by the US Food and Drug Administration, who suggested conducting at least one further randomized clinical trial in children and/or adults [37].

Unlike comprehensive studies on the fields of acute GVHD therapies via MSCs administration, the effectiveness of MSCs in chronic GVHD has rarely been reported and inadequate and temporary benefits can be found in chronic GVHD patients following MSCs administration [4]. Nevertheless, Weng et al. reported notable advancements of MSC-based therapy in refractory chronic GVHD patients [77]. The modulation of chronic GVHD by MSCs has been applied via promoting B lymphocyte reconstruction and maintaining homeostasis of B lymphocyte through enhancing naive and memory B lymphocyte subsets in patients with responsive chronic GVHD and modulating BAFF secretion and BAFF-R expression on B lymphocytes [89]. Also, recent report found that MSCs promote the proliferation of regulatory CD5+ B cells (Bregs) in responsive chronic GVHD patients [4, 53].

In the starting of clinical trials investigations, Ringden’s pilot investigation employing MSCs to treat a steroid-refractory GVHD pediatric patient was a landmark in the area of MSC therapy. This study was followed by considerable worldwide investigations on the treatment of various types of GVHD including de novo GVHD, steroid-refractory GVHD, chronic GVHD and prevention of GVHD [90].

The first clinical trial of cGVHD where 19 severe refractory patients were treated with MSC reported that administration of MSCs seems to be more effective for liver, gastrointestinal tract, and skin involvement of cGVHD patients. In addition, keratoconjunctivitis sicca patients exhibited improved clinical symptoms accompanied by an enhanced ratio of CD8+ CD28−/CD8+ CD28+ T lymphocytes and CD5+ CD19+/CD5− CD19+ B lymphocytes, representing the effective mechanisms of immune modulation by MSCs [77]. Recently, Boberg et al. evaluated the BM-derived MSCs treatment of 11 patients with severe steroid-refractory cGvHD over a 6- to 12-month period [83]. The data indicated that repeated MSC infusions were well tolerated without urgent side effects in volunteers and the immunological properties of patients including levels of inflammatory cytokine (CXCL10, CXCL2, and CCL2), absolute numbers of naive B cells (CD19+ IgD+ CD38low) and ability to generate sufficient numbers of naive T cells and Tregs were affected by the success of MSC therapy [83]. Conclusively, it is suggested to develop more homogeneous MSC preparations by using MSCs obtained from different donors for the improvement of therapeutic purposes [91]. Wang also reported that IFN-γ treated MSCs significantly decreased the GVHD incidence and increased the survival rate of mice after allogeneic HSCT [84].

Interestingly, previous studies demonstrated that several molecules such as BAFF, ST2, MMP-3, CXCL9, CXCL10, the macrophage scavenging receptor CD163, osteopontin, and DKK3 (Dickkopf-related protein 3) could be effective prognostic cGVHD biomarkers after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation [37, 92].

In addition, MSCs decrease the chronic GVHD occurrence and severity in acute GVHD patients through their immunomodulatory effects on central immune compartments via promoting thymic function [4, 93]. Notwithstanding the developing experimental and clinical application of MSCs in regenerative medicine [94–96], clinical MSC-based therapeutic approaches have not been efficiently organized as low engraftment and viability of cells restrict the therapeutic efficiency of MSC transplantation. So that several MSC immunotherapy trials on phase III are incapable of reaching the primary clinical endpoints considering the low efficiency of engrafted cells [6, 97]. Despite comprehensive investigation of therapeutic applications, the efficacy of MSCs still confronts formidable questions. In this way, improving the MSC immunosuppressive characteristic is considered as one of the basic problems of MSC treatment [6]. One of the best options for improving therapeutic privileges is genetically engineering of MSCs to produce therapeutic molecules [5, 98, 99]. Genetically modification of MSCs for improving their viability and therapeutic effectiveness has been recommended as a possible efficient approach to tissue repair and reconstruction [100].

Genetically modified MSCs as a new trend for treatment of severe acute GVHD

Therapeutic applications of MSCs are facing remarkable objections in terms of potency and efficiency. Nowadays, genetic engineering of MSCs to generate therapeutic molecules (several cytokines with notable immunomodulatory effects) without interfering with their differentiation and self-regeneration manners is applied to promote therapeutic advantages [2, 5]. Accordingly, various clinical trials, as well as animal models using engineered MSC, have been designed (Fig. 3). For this purpose, MSCs can be instantly expanded and genetically transduced with viral vectors (adenoviruses, and helper-dependent adenoviral and lentiviral vectors) [101] and transfected by non-viral vectors (inorganic nanomaterials, cationic peptides, cationic polysaccharides, and cationic polymers) [102] ex vivo or in vitro, and then utilized for therapeutic purposes in vivo [5].

Figure 3.

advantages of engineered MSC therapy in GVHD. Different types of engineered mesenchymal cells, as well as the clinical and therapeutic outcomes of this type of cell therapy in GVHD, are shown. Genetic engineering of MSCs is aimed at improving their survival and engraftment as well as enhancing their repair mechanisms. Being easily isolated, having multilineage differentiation capacity،“manipulated ex vivo” and homing into the injury area are considered as features of engineered MSC. Upon genetic modification, they gain improved therapeutic functionalities of increased injury repair and disease recovery.

Additionally, MSCs could genetically be transformed via micro-and nano-injection, electroporation, microporation, and nucleofection [103]. The efficacy of transduction differs based on target cells and viral vectors. Viral vectors are commonly recognized to have high transduction effectiveness and infectivity and have been genetically modified to improve their transduction efficiencies and to decrease their immunogenicity, inflammatory impacts and toxicity [104]. It is demonstrated the clinical efficiency of genetically engineered MSCs with adenoviral vectors is poor due to the low adenoviral transduction and gene delivery efficiencies with the loss of adenovirus and coxsackie receptor expression [5, 105, 106].

Gene modified MSCs have demonstrated enhanced therapeutic outcomes in various preclinical models of human disorders [55]. In the cancer field, MSCs have been genetically modified to express and produce enhanced cytokines levels with associated antitumor functions inside the microenvironment in other to expand endogenous immunity against malignancy [107, 108]. Studeny et al. were reported the primary findings of this kind of modified cells via IFN-β-engineered MSCs, a cytokine with potent anti-proliferative effects on different cell types (i.e. tumor cells) and inhibitory functions on the metastatic melanoma growth. They showed IFN-β-engineered MSCs have more ability to inhibit tumor development in comparison to systemic IFN-β therapy [107]. Afterward, high expression IL-2 and IL-12-engineered MSCs were applied to improve the survival in various cancer models (i.e. glioma and renal cell carcinoma) [109–111].

Several experimental models of autoimmunity via gene-modified MSCs have also been conducted [112]. Earlier mouse studies showed TGF-β-engineered MSCs could potently repress collagen-induced arthritis models in comparison to untransduced MSCs [113]. Furthermore, IL-4-engineered MSCs could attenuate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis [114]. Another study demonstrated that human UCB mesenchymal stem cells (HUCB-MSCs) genetically modified with VEGF165 showed enhanced HUCB-MSCs multipotency and increased homing capacity and colonization in the liver tissues of acute liver failure (ALF) rats. Moreover, VEGF165-HUCB-MSC represented stronger therapeutic effects on improving liver injury and increasing liver regeneration to some extent in ALF rats [115].

Park et al. developed a cell therapy approach through genetically engineered human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hUC-MSCs), which secrete angiogenic (VEGF or ANG1) or anti-inflammatory (EPO or αMSH) factors. They demonstrated that these genome-engineered MSCs represent a protective effect in improving mice acute kidney injury (AKI) and suggested them as a promising treatment for AKI [116]. Increasing evidence indicates MSCs application for prophylaxis of acute GVHD was safe and effective. It is reported that co-transplanted MSCs with HSCs reduced the acute GVHD incidence to some degree, notwithstanding many investigations showed no statistical difference in comparison with the historical control group [4]. Nowadays, for improvement of highly specific MSC therapeutic effects, tissue-dependent genetically engineered MSCs with therapeutic transgene expression are emerging as a promising therapeutic tools. The potency of MSCs could improve independent of external inflammatory stimuli through gene modification to maintain the expression of therapeutic genes. There is evidence that for overcoming the development of GVHD, in vivo treatment with genetically modified MSCs overexpressing IL-10 significantly decrease mortality rates of mice, which is associated with reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines [117]. Last studies in the field of GVHD treatment with genetically modified MSCs were summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

experimental and clinical outcomes of genetically modified MSCs

| MSCs source/type of engineered MSC | Cell line/models/human | Experimental outcomes | Clinical outcomes | Year | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM/(IL-10-MSC) | Well-established murine model of human GVHD | Serum levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, IFN-γ on day + 7 ↓ | Mortality at day 50 after the transplant ↓ | 2007 | [117] |

| Semi-quantitative GVHD score ↓ | |||||

| BM/ (let-7a knockdown in MSCs) | Experimental GVHD and colitis mouse models | Prevents both FasL and Fas protein accumulation | Therapeutic effect of MSC cytotherapy on inflammatory bowel diseases and GVHD ↑ | 2016 | [6] |

| In vitro MSC-induced T cell apoptosis and migration ↑ | |||||

| In vivo MSC-induced T cell apoptosis ↑ | |||||

| MSC cytotherapy through Fas/FasL ↑ | |||||

| BM/(AKT1-MSCs) | ConA-induced liver injury model | Survival (anti-apoptotic) ↑ | Histopathological abnormalities of liver injury ↓ | 2019 | [118] |

| Homing capacity ↑ | Amelioration of ConA-induced liver GVHD and liverinjury↑ | ||||

| Persistence in the damaged liver ↑ | |||||

| IL-4, IL-10, PTGES2, HGF and VEGF mRNA expression ↑ | |||||

| IL-10, VEGF and HGF protein levels after IFN-γ stimulation ↑ | |||||

| Serum levels of AST and ALT ↓ | |||||

| Tissue and serum TNF-α and IFN-γ ↓ | |||||

| BM/(MSC-TGF-β1) | Mouse aGVHD model | In vitro immunosuppressive potential of T lymphocyte ↑ | Ameliorated aGvHD severity | 2020 | [119] |

| Polarization of M2 macrophages in aGVHD mice ↑ | Increased overall survival in murine model | ||||

| Treg cell proportion in peripheral blood of aGVHD mice ↑ | Improved overall survival andclinical symptomsin aGVHD murine model |

Lately, Shi and colleagues discovered that Fas/Fas ligand (FasL) expressed on MSCs are essential for MSC treatment of inflammatory disorders [120]. FasL and Fas play critical roles in triggering pathways of T lymphocyte apoptosis and enhancing the T cell migration, respectively [121]. In MS, it is recommended that increasing Fas and FasL expression in MSCs can improve MSC treatment efficacy [120]. Nevertheless, because FasL/Fas interaction could induce MSC apoptosis, it is required to adjust their levels for proper therapy course [122]. The subsequent study developed a miRNAs targeting of Fas and FasL mRNA (let-7a as a negative regulator of Fas/FasL expression) to improve a miRNA-based approach in promoting MSC treatment for inflammatory disorders such as GVHD and IBD [6]. Let-7a Knockdown increases FasL/Fas protein levels approximately 2-fold, which significantly increases in vitro and in vivo FasL-induced T-cell apoptosis and Fas-induced T-cell migration. There is evidence that upregulation of Fas/FasL might also increase Treg levels, resulting in the rebalancing of the immune system [6].

Zhou L et al. reported that BM-MSCs genetically modified with AKT1 could be an efficient therapeutic candidate for the prevention and improvement of hepatic GVHD and other immunity- related liver lesions. The data demonstrated that AKT1-MSCs have a better homing capacity, anti-apoptotic advantage, and high persistence in the damaged liver compared with null-MSC treatment based on in vitro apoptosis analyses. Also, AKT1-MSCs showed improved immunomodulatory activity both in vivo and in vitro as elevated secretion of IL-10, decreased the histopathological abnormalities of liver injury besides lower serum levels of AST and ALT and tissue and serum TNF-α and IFN-γ) [118]. Wu et al. observed that MSC-TGF-β1 exhibited an improved immunosuppressive function on the proliferation of lymphocytes in vitro. In vivo, MSC-TGF-β1 prophylaxis and treatment decreased the aGVHD severity in murine models. Finally, MSC-TGF-β1–treated mice exhibited a remarkable developing anti-inflammatory M2-like phenotype macrophage and CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ Treg cells differentiation [84, 119].

Concerns about clinical application of MSC

Based on previous studies, one of the main concerns in the clinical application of MSCs for various disorders treatment is the potential of MSCs to increase the tumor recurrence and incidence of infection. There is evidence that MSCs through secretion of certain cytokines such as IL-6 and VEGF and suppressing T-cell response raise the risk of infections and tumor relapse [4]. One of the most significant current discussions concerning MSC based treatments is in vitro survival and lifespan of MSCs. Several studies have revealed that MSCs quickly lose their potential of proliferation and multipotency during in vitro culture rounds [123, 124] and attempts to solve the issue will be of great help to reduce the inconsistency in the previous research findings into therapy outcome of genetically engineered MSC-based strategies.

Conclusion

The present review described GVHD therapies using genetically engineered MSCs. MSCs play several roles in modulating immune or inflammation response (via direct cell-to-cell contact mechanisms and indirectly through secretion of several anti-inflammatory factors), repairing tissue (via the regeneration capacity), migration capacity to the inflammation sites. The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties of MSCs are the main clinical significance of these cells. Immunosuppressive functions of MSCs including escaping circulating T-cell recognition, improving hematopoiesis by modulating the inflammatory microenvironment, promotion of Tregs development and suppression of the monocyte differentiation to DCs and turn them to a more tolerogenic profile, are successfully applied to ameliorate GVHD. One of the most important challenges in MSCs clinical application is their therapeutic efficiency. MSCs can be genetically modified to improve clinical therapeutic advantages via production of therapeutic molecules including target-associated cytokines and other modulatory molecules with notable immunomodulatory effects without interfering with their differentiation and self-regeneration manners.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BMT

bone marrow transplantation

- CD

cluster of differentiation

- CTL

cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- FasL

Fas ligand

- GVHD

graft-versus-host disease

- HSCT

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- IDO

indoleamine 2:3-dioxygenase

- IL

interleukin

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- MSCs

mesenchymal stem cells

- NK cells

Natural Killer cells

- Tregs

regulatory T cells

- OR

overall response

- OS

overall survival

Contributor Information

Sanaz Keshavarz Shahbaz, Cellular and Molecular Research Center, Research Institute for Prevention of Non-communicable Disease, Qazvin University of Medical Science, Qazvin, Iran.

Amir Hossein Mansourabadi, Department of Immunology, School of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran; Immunogenetics Research Network (IgReN), Universal Scientific Education and Research Network (USERN), Tehran, Iran.

Davood Jafari, Department of Immunology, School of Medicine, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Zanjan, Iran; Immunogenetics Research Network (IgReN), Universal Scientific Education and Research Network (USERN), Zanjan, Iran.

Funding

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be considered as a potential conflict of interest.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

D.J. and S.K. were responsible for designing the review protocol, writing the manuscript, conducting the search, screening potentially eligible studies, extracting data, interpreting results and creating “Summary of findings” tables. A.H.M. was responsible for designing the review protocol and screening potentially eligible studies. He contributed to writing the report, extracting and analyzing data, updating reference lists, and interpreting results.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary material.

References

- 1. Niess H, Thomas MN, Schiergens TS, Kleespies A, Jauch K-W, Bruns C, et al. Genetic engineering of mesenchymal stromal cells for cancer therapy: turning partners in crime into Trojan horses. Innov Surg Sci 2016, 1, 19–32. doi: 10.1515/iss-2016-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu H, Ye Z, Mahato RI. Genetically modified mesenchymal stem cells for improved islet transplantation. Mol Pharm 2011, 8, 1458–70. doi: 10.1021/mp200135e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mansourabadi AH, Khosroshahi LM, Noorbakhsh F, Amirzargar A. Cell therapy in transplantation: a comprehensive review of the current applications of cell therapy in transplant patients with the focus on Tregs, CAR Tregs, and Mesenchymal stem cells. Int Immunopharmacol 2021, 97, 107669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhao K, Liu Q. The clinical application of mesenchymal stromal cells in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Hematol Oncol 2016, 9, 46. doi: 10.1186/s13045-016-0276-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hwang BW, Kim SJ, Park KM, Kim H, Yeom J, Yang J-A, et al. Genetically engineered mesenchymal stem cell therapy using self-assembling supramolecular hydrogels. J Control Release 2015, 220, 119–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yu Y, Liao L, Shao B, Su X, Shuai Y, Wang H, et al. Knockdown of MicroRNA Let-7a improves the functionality of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in immunotherapy. Mol Ther 2017, 25, 480–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2016.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim N, Cho S-G. Clinical applications of mesenchymal stem cells. Korean J Intern Med 2013, 28, 387–402. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2013.28.4.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–7. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Choi YS, Dusting GJ, Stubbs S, Arunothayaraj S, Han XL, Collas P, et al. Differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells into beating cardiomyocytes. J Cell Mol Med 2010, 14, 878–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seo B-M, Miura M, Gronthos S, Bartold PM, Batouli S, Brahim J, et al. Investigation of multipotent postnatal stem cells from human periodontal ligament. Lancet 2004, 364, 149–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kuroda Y, Kitada M, Wakao S, Nishikawa K, Tanimura Y, Makinoshima H, et al. Unique multipotent cells in adult human mesenchymal cell populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010, 107, 8639–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911647107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guo F, Kerrigan BCP, Yang D, Hu L, Shmulevich I, Sood AK, et al. Post-transcriptional regulatory network of epithelial-to-mesenchymal and mesenchymal-to-epithelial transitions. J Hematol Oncol 2014, 7, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sun Z, Wang S, Zhao RC. The roles of mesenchymal stem cells in tumor inflammatory microenvironment. J Hematol Oncol 2014, 7, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Karp JM, Teo GSL. Mesenchymal stem cell homing: the devil is in the details. Cell Stem Cell 2009, 4, 206–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marquez-Curtis LA, Janowska-Wieczorek A. Enhancing the migration ability of mesenchymal stromal cells by targeting the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis. Biomed Res Int 2013, 2013, 1–15. doi: 10.1155/2013/561098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Joo SY, Cho KA, Jung YJ, Kim H, Park SY, Choi YB, et al. Bioimaging for the monitoring of the in vivo distribution of infused mesenchymal stem cells in a mouse model of the graft-versus-host reaction. Cell Biol Int 2011, 35, 417–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sacchetti B, Funari A, Michienzi S, Di Cesare S, Piersanti S, Saggio I, et al. Self-renewing osteoprogenitors in bone marrow sinusoids can organize a hematopoietic microenvironment. Cell 2007, 131, 324–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meuleman N, Tondreau T, Ahmad I, Kwan J, Crokaert F, Delforge A, et al. Infusion of mesenchymal stromal cells can aid hematopoietic recovery following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell myeloablative transplant: a pilot study. Stem Cells Dev 2009, 18, 1247–52. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Le Blanc K, Götherström C, Ringdén O, Hassan M, McMahon R, Horwitz E, et al. Fetal mesenchymal stem-cell engraftment in bone after in utero transplantation in a patient with severe osteogenesis imperfecta. Transplantation 2005, 79, 1607–14. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000159029.48678.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Elgaz S, Kuçi Z, Kuçi S, Bönig H, Bader P. Clinical use of mesenchymal stromal cells in the treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease. Transfus Med Hemother 2019, 46, 27–34. doi: 10.1159/000496809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wolf D, Wolf AM. Mesenchymal stem cells as cellular immunosuppressants. Lancet (London, England) 2008, 371, 1553–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60666-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Keating A. Mesenchymal stromal cells: new directions. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 10, 709–16. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bartholomew A, Sturgeon C, Siatskas M, Ferrer K, McIntosh K, Patil S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro and prolong skin graft survival in vivo. Exp Hematol 2002, 30, 42–8. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00769-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Uccelli A, de Rosbo NK. The immunomodulatory function of mesenchymal stem cells: mode of action and pathways. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2015, 1351, 114–26. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Di Nicola M, Carlo-Stella C, Magni M, Milanesi M, Longoni PD, Matteucci P, et al. Human bone marrow stromal cells suppress T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by cellular or nonspecific mitogenic stimuli. Blood 2002, 99, 3838–43. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Le Blanc K, Davies LC. Mesenchymal stromal cells and the innate immune response. Immunol Lett 2015, 168, 140–6. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bader P, Kuçi Z, Bakhtiar S, Basu O, Bug G, Dennis M, et al. Effective treatment of steroid and therapy-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease with a novel mesenchymal stromal cell product (MSC-FFM). Bone Marrow Transplant 2018, 53, 852–62. doi: 10.1038/s41409-018-0102-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Keating A. How do mesenchymal stromal cells suppress T cells?. Cell Stem Cell 2008, 2, 106–8. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Abdelrazik H, Becchetti F, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit natural killer–cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, and cytokine production: role of indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase and prostaglandin E2. Blood. J Am Soc Hematol 2008, 111, 1327–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jafari D, Nafar M, Yekaninejad MS, Abdolvahabi R, Pezeshki ML, Razaghi E, et al. Investigation of killer immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) and HLA genotypes to predict the occurrence of acute allograft rejection after kidney transplantation. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol 2017, 16, 245–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bonakdar AT, Mohammadi MM, Namdar A, Ahmadpoor P, Jafari D, Yekaninejad MS, et al. Natural killer cells exhibit an activated phenotype in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of renal allograft rejection recipients: a preliminary study. Exp Clin Transplant 2019, 4, 490–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhou X, Jin N, Wang F, Chen B. Mesenchymal stem cells: a promising way in therapies of graft-versus-host disease. Cancer Cell Int 2020, 20, 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Abdelrazik H, Becchetti F, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit natural killer-cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, and cytokine production: role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and prostaglandin E2. Blood 2008, 111, 1327–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-074997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Selmani Z, Naji A, Zidi I, Favier B, Gaiffe E, Obert L, et al. Human leukocyte antigen-G5 secretion by human mesenchymal stem cells is required to suppress T lymphocyte and natural killer function and to induce CD4+ CD25highFOXP3+ regulatory T cells. Stem Cells 2008, 26, 212–22. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Krampera M, Cosmi L, Angeli R, Pasini A, Liotta F, Andreini A, et al. Role for interferon-γ in the immunomodulatory activity of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 2006, 24, 386–98. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Braza F, Dirou S, Forest V, Sauzeau V, Hassoun D, Chesné J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells induce suppressive macrophages through phagocytosis in a mouse model of asthma. Stem Cells 2016, 34, 1836–45. doi: 10.1002/stem.2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Introna M, Golay J. Tolerance to bone marrow transplantation: do mesenchymal stromal cells still have a future for acute or chronic GvHD?. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 609063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. de Witte SFH, Luk F, Sierra Parraga JM, Gargesha M, Merino A, Korevaar SS, et al. Immunomodulation by therapeutic mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) is triggered through phagocytosis of MSC by monocytic cells. Stem Cells 2018, 36, 602–15. doi: 10.1002/stem.2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ringden O, Keating A. Mesenchymal stromal cells as treatment for chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011, 46, 163–4. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Godoy JAP, Paiva RMA, Souza AM, Kondo AT, Kutner JM, Okamoto OK. Clinical translation of mesenchymal stromal cell therapy for graft versus host disease. Front Cell Dev Biol 2019, 7, 255. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zahid MF, Lazarus HM, Ringdén O, Barrett JA, Gale RP, Hashmi SK. Can we prevent or treat graft-versus-host disease with cellular-therapy?. Blood Rev 2020, 43, 100669. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2020.100669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cheung TS, Bertolino GM, Giacomini C, Bornhäuser M, Dazzi F, Galleu A. Mesenchymal stromal cells for graft versus host disease: mechanism-based biomarkers. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Voermans C, Hazenberg MD. Cellular therapies for graft-versus-host disease: a tale of tissue repair and tolerance. Blood 2020, 136, 410–7. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Locatelli F, Algeri M, Trevisan V, Bertaina A. Remestemcel-L for the treatment of graft versus host disease. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2017, 13, 43–56. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2016.1208086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Galipeau J. Mesenchymal stromal cells for graft-versus-host disease: a trilogy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2020, 26, e89–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gomez-Salazar M, Gonzalez-Galofre ZN, Casamitjana J, Crisan M, James AW, Péault B. Five decades later, are mesenchymal stem cells still relevant?. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020, 8, 148. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Le Blanc K, Mougiakakos D. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells and the innate immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2012, 12, 383–96. doi: 10.1038/nri3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dazzi F, Lopes L, Weng L. Mesenchymal stromal cells: a key player in ‘innate tolerance’?. Immunology 2012, 137, 206–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2012.03621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Maccario R, Podestà M, Moretta A, Cometa A, Comoli P, Montagna D, et al. Interaction of human mesenchymal stem cells with cells involved in alloantigen-specific immune response favors the differentiation of CD4+ T-cell subsets expressing a regulatory/suppressive phenotype. Haematologica 2005, 90, 516–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rasmusson I, Ringdén O, Sundberg B, Le Blanc K. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the formation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes, but not activated cytotoxic T lymphocytes or natural killer cells. Transplantation 2003, 76, 1208–13. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000082540.43730.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Franquesa M, Hoogduijn MJ, Bestard O, Grinyó JM. Immunomodulatory effect of mesenchymal stem cells on B cells. Front Immunol 2012, 3, 212. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Corcione A, Benvenuto F, Ferretti E, Giunti D, Cappiello V, Cazzanti F, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate B-cell functions. Blood 2006, 107, 367–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Peng Y, Chen X, Liu Q, Zhang X, Huang K, Liu L, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells infusions improve refractory chronic graft versus host disease through an increase of CD5+ regulatory B cells producing interleukin 10. Leukemia 2015, 29, 636–46. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bernardo ME, Fibbe WE. Mesenchymal stromal cells: sensors and switchers of inflammation. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 13, 392–402. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kumar S, Chanda D, Ponnazhagan S. Therapeutic potential of genetically modified mesenchymal stem cells. Gene Ther 2008, 15, 711–5. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. James R, Haridas N, Deb KD. Clinical applications of mesenchymal stem cells. Biointegration of Medical Implant Materials. Elsevier; 2020; 101–16. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bacigalupo A. Management of acute graft-versus-host disease. Br J Haematol 2007, 137, 87–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hoseinian SA, Jafari D, Mahmoodi M, Alimoghaddam K, Ostadali M, Bonakdar AT, et al. The impact of donor and recipient KIR genes and KIR ligands on the occurrence of acute graft-versus-host disease and graft survival after HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Turk J Med Sci 2018, 48, 794–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ball LM, Bernardo ME, Roelofs H, Lankester A, Cometa A, Egeler RM, et al. Cotransplantation of ex vivo expanded mesenchymal stem cells accelerates lymphocyte recovery and may reduce the risk of graft failure in haploidentical hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Blood 2007, 110, 2764–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-087056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dazzi F, Ramasamy R, Glennie S, Jones SP, Roberts I. The role of mesenchymal stem cells in haemopoiesis. Blood Rev 2006, 20, 161–71. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Martinez-Cibrian N, Zeiser R, Perez-Simon JA. Graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis: Pathophysiology-based review on current approaches and future directions. Blood Rev 2021, 48, 100792. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2020.100792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dal Collo G, Adamo A, Gatti A, Tamellini E, Bazzoni R, Takam Kamga P, et al. Functional dosing of mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles for the prevention of acute graft-versus-host-disease. Stem Cells 2020, 38, 698–711. doi: 10.1002/stem.3160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lee SJ. Classification systems for chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2017, 129, 30–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-07-686642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Schoemans HM, Lee SJ, Ferrara JL, Wolff D, Levine JE, Schultz KR, et al. EBMT-NIH-CIBMTR Task Force position statement on standardized terminology & guidance for graft-versus-host disease assessment. Bone Marrow Transplant 2018, 53, 1401–15. doi: 10.1038/s41409-018-0204-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Funke VA, Moreira MCR, Vigorito AC. Acute and chronic Graft-versus-host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Rev Assoc Méd Bras 2016, 62, 44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Murray J, Stringer J, Hutt D. Graft-versus-host disease (GvHD). The European Blood and Marrow Transplantation Textbook for Nurses. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018:221–51. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Le Blanc K, Rasmusson I, Sundberg B, Götherström C, Hassan M, Uzunel M, et al. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. The Lancet 2004, 363, 1439–41. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(04)16104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yagi H, Soto-Gutierrez A, Parekkadan B, Kitagawa Y, Tompkins RG, Kobayashi N, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: mechanisms of immunomodulation and homing. Cell Transplant 2010, 19, 667–79. doi: 10.3727/096368910X508762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ankrum JA, Ong JF, Karp JM. Mesenchymal stem cells: immune evasive, not immune privileged. Nat Biotechnol 2014, 32, 252–60. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Galipeau J, Sensébé L. Mesenchymal stromal cells: clinical challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22, 824–33. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sudres M, Norol F, Trenado A, Grégoire S, Charlotte F, Levacher B, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro but fail to prevent graft-versus-host disease in mice. J Immunol 2006, 176, 7761–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Auletta JJ, Eid SK, Wuttisarnwattana P, Silva I, Metheny L, Keller MD, et al. Human mesenchymal stromal cells attenuate graft-versus-host disease and maintain graft-versus-leukemia activity following experimental allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Stem Cells 2015, 33, 601–14. doi: 10.1002/stem.1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Grégoire C, Ritacco C, Hannon M, Seidel L, Delens L, Belle L, et al. Comparison of mesenchymal stromal cells from different origins for the treatment of graft-vs.-host-disease in a humanized mouse model. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Seng A, Dunavin N. Mesenchymal stromal cell infusions for acute graft-versus-host disease: Rationale, data, and unanswered questions. Adv Cell Gene Ther 2018, 1, e14. doi: 10.1002/acg2.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Lazarus HM, Koc ON, Devine SM, Curtin P, Maziarz RT, Holland HK, et al. Cotransplantation of HLA-identical sibling culture-expanded mesenchymal stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells in hematologic malignancy patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005, 11, 389–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Galipeau J. The mesenchymal stromal cells dilemma--does a negative phase III trial of random donor mesenchymal stromal cells in steroid-resistant graft-versus-host disease represent a death knell or a bump in the road?. Cytotherapy 2013, 15, 2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Weng J, Du X, Geng S, Peng Y, Wang Z, Lu Z, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell as salvage treatment for refractory chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant 2010, 45, 1732–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zhao K, Lou R, Huang F, Peng Y, Jiang Z, Huang K, et al. Immunomodulation effects of mesenchymal stromal cells on acute graft-versus-host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015, 21, 97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. von Dalowski F, Kramer M, Wermke M, Wehner R, Röllig C, Alakel N, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells for treatment of acute steroid-refractory graft versus host disease: clinical responses and long-term outcome. Stem Cells 2016, 34, 357–66. doi: 10.1002/stem.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kebriaei P, Hayes J, Daly A, Uberti J, Marks DI, Soiffer R, et al. A phase 3 randomized study of remestemcel-L versus placebo added to second-line therapy in patients with steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2020, 26, 835–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kurtzberg J, Abdel-Azim H, Carpenter P, Chaudhury S, Horn B, Mahadeo K, et al. A phase 3, single-arm, prospective study of remestemcel-L, ex vivo culture-expanded adult human mesenchymal stromal cells for the treatment of pediatric patients who failed to respond to steroid treatment for acute graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2020, 26, 845–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kurtzberg J, Prockop S, Chaudhury S, Horn B, Nemecek E, Prasad V, et al. Study 275: updated expanded access program for remestemcel-l in steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease in children. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2020, 26, 855–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Boberg E, von Bahr L, Afram G, Lindström C, Ljungman P, Heldring N, et al. Treatment of chronic GvHD with mesenchymal stromal cells induces durable responses: a phase II study. Stem Cells Transl Med 2020, 9, 1190–202. doi: 10.1002/sctm.20-0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Wang Y. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) delays the occurrence of graft-versus-host disease(GVHD) in the inhibition of hematopoietic stem cells in major histocompatibility complex semi-consistent mice by regulating the expression of IFN-γ/IL-6. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 4500–7. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2021.1955549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Baron F, Lechanteur C, Willems E, Bruck F, Baudoux E, Seidel L, et al. Cotransplantation of mesenchymal stem cells might prevent death from graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) without abrogating graft-versus-tumor effects after HLA-mismatched allogeneic transplantation following nonmyeloablative conditioning. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2010, 16, 838–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Martin PJ, Uberti JP, Soiffer RJ, Klingemann H, Waller EK, Daly AS, et al. Prochymal improves response rates in patients with steroid-refractory acute graft versus host disease (SR-GVHD) involving the liver and gut: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase III trial in GVHD. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2010, 16, S169–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.12.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Hashmi S, Ahmed M, Murad MH, Litzow MR, Adams RH, Ball LM, et al. Survival after mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Haematol 2016, 3, e45–52. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(15)00224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Fisher SA, Cutler A, Doree C, Brunskill SJ, Stanworth SJ, Navarrete C, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells as treatment or prophylaxis for acute or chronic graft-versus-host disease in haematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients with a haematological condition. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019, 1, Cd009768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Peng Y, Chen X, Liu Q, Xu D, Zheng H, Liu L, et al. Alteration of naive and memory B-cell subset in chronic graft-versus-host disease patients after treatment with mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cells Transl Med 2014, 3, 1023–31. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Kim N, Cho S-G. Stem Cell Therapy for GVHD. Stem Cells: Basics and Clinical Translation. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer; 2015, 361–89. [Google Scholar]

- 91. Russell AL, Lefavor RC, Zubair AC. Characterization and cost–benefit analysis of automated bioreactor-expanded mesenchymal stem cells for clinical applications. Transfusion 2018, 58, 2374–82. doi: 10.1111/trf.14805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Inamoto Y, Martin PJ, Lee SJ, Momin AA, Tabellini L, Onstad LE, et al. Dickkopf-related protein 3 is a novel biomarker for chronic GVHD after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood Adv 2020, 4, 2409–17. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Zhao K, Lou R, Huang F, Peng Y, Jiang Z, Huang K, et al. Immunomodulation effects of mesenchymal stromal cells on acute graft-versus-host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015, 21, 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Gómez-Barrena E, Rosset P, Müller I, Giordano R, Bunu C, Layrolle P, et al. Bone regeneration: stem cell therapies and clinical studies in orthopaedics and traumatology. J Cell Mol Med 2011, 15, 1266–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Wei C-C, Lin AB, Hung S-C. Mesenchymal stem cells in regenerative medicine for musculoskeletal diseases: bench, bedside, and industry. Cell Transplant 2014, 23, 505–12. doi: 10.3727/096368914X678328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Zaidi N, Nixon AJ. Stem cell therapy in bone repair and regeneration. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007, 1117, 62–72. doi: 10.1196/annals.1402.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Ankrum J, Karp JM. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy: two steps forward, one step back. Trends Mol Med 2010, 16, 203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Aggarwal S, Pittenger MF. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood 2005, 105, 1815–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Griffin MD, Ritter T, Mahon BP. Immunological aspects of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell therapies. Hum Gene Ther 2010, 21, 1641–55. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Kim S-H, Moon H-H, Chung B-G, Choi D-H. Preparation and characterization of genetically engineered mesenchymal stem cell aggregates for regenerative medicine. J Pharmaceut Invest 2010, 40, 333–7. [Google Scholar]

- 101. Bouard D, Alazard-Dany N, Cosset FL. Viral vectors: from virology to transgene expression. Br J Pharmacol 2009, 157, 153–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Yin H, Kanasty RL, Eltoukhy AA, Vegas AJ, Dorkin JR, Anderson DG. Non-viral vectors for gene-based therapy. Nat Rev Genet 2014, 15, 541–55. doi: 10.1038/nrg3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Nowakowski A, Andrzejewska A, Janowski M, Walczak P, Lukomska B. Genetic engineering of stem cells for enhanced therapy. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2013, 73, 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Tomanin R, Scarpa M. Why do we need new gene therapy viral vectors? Characteristics, limitations and future perspectives of viral vector transduction. Curr Gene Ther 2004, 4, 357–72. doi: 10.2174/1566523043346011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Bergelson JM, Cunningham JA, Droguett G, Kurt-Jones EA, Krithivas A, Hong JS, et al. Isolation of a common receptor for Coxsackie B viruses and adenoviruses 2 and 5. Science 1997, 275, 1320–3. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Kim SM, Lim JY, Park SI, Jeong CH, Oh JH, Jeong M, et al. Gene therapy using TRAIL-secreting human umbilical cord blood–derived mesenchymal stem cells against intracranial glioma. Cancer Res 2008, 68, 9614–23. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Studeny M, Marini FC, Champlin RE, Zompetta C, Fidler IJ, Andreeff M. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells as vehicles for interferon-β delivery into tumors. Cancer Res 2002, 62, 3603–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Chen X, Lin X, Zhao J, Shi W, Zhang H, Wang Y, et al. A tumor-selective biotherapy with prolonged impact on established metastases based on cytokine gene-engineered MSCs. Mol Ther 2008, 16, 749–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Nakamura K, Ito Y, Kawano Y, Kurozumi K, Kobune M, Tsuda H, et al. Antitumor effect of genetically engineered mesenchymal stem cells in a rat glioma model. Gene Ther 2004, 11, 1155–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Hong X, Miller C, Savant-Bhonsale S, Kalkanis SN. Antitumor treatment using interleukin-12-secreting marrow stromal cells in an invasive glioma model. Neurosurgery 2009, 64, 1139–46; discussion 1146. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000345646.85472.EA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Gao P, Ding Q, Wu Z, Jiang H, Fang Z. Therapeutic potential of human mesenchymal stem cells producing IL-12 in a mouse xenograft model of renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett 2010, 290, 157–66. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Kim N, Cho S-G. New strategies for overcoming limitations of mesenchymal stem cell-based immune modulation. Int J Stem Cells 2015, 8, 54–68. doi: 10.15283/ijsc.2015.8.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Park MJ, Park HS, Cho ML, Oh HJ, Cho YG, Min SY, et al. Transforming growth factor β–transduced mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate experimental autoimmune arthritis through reciprocal regulation of Treg/Th17 cells and osteoclastogenesis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2011, 63, 1668–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Payne NL, Dantanarayana A, Sun G, Moussa L, Caine S, McDonald C, et al. Early intervention with gene-modified mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing interleukin-4 enhances anti-inflammatory responses and functional recovery in experimental autoimmune demyelination. Cell Adhes Migr 2012, 6, 179–89. doi: 10.4161/cam.20341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Chen H, Tang S, Liao J, Liu M, Lin Y. VEGF165 gene-modified human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells protect against acute liver failure in rats. J Gene Med 2021, n/a, e3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Park H-J, Kong MJ, Jang H-J, Cho J-I, Park E-J, Lee I-K, et al. A nonbiodegradable scaffold-free cell sheet of genome-engineered mesenchymal stem cells inhibits development of acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 2021, 99, 117–33. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Min C, Kim B, Park G, Cho B, Oh I. IL-10-transduced bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells can attenuate the severity of acute graft-versus-host disease after experimental allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2007, 39, 637–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Zhou L, Liu S, Wang Z, Yao J, Cao W, Chen S, et al. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells modified with Akt1 ameliorates acute liver GVHD. Biol Proced Online 2019, 21, 24. doi: 10.1186/s12575-019-0112-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Wu R, Liu C, Deng X, Chen L, Hao S, Ma L. Enhanced alleviation of aGVHD by TGF-β1-modified mesenchymal stem cells in mice through shifting MΦ into M2 phenotype and promoting the differentiation of Treg cells. J Cell Mol Med 2020, 24, 1684–99. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Akiyama K, Chen C, Wang D, Xu X, Qu C, Yamaza T, et al. Mesenchymal-stem-cell-induced immunoregulation involves FAS-ligand-/FAS-mediated T cell apoptosis. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 10, 544–55. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Murphy WJ, Nolta JA. Autoimmune T cells lured to a FASL web of death by MSCs. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 10, 485–7. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Kennea N, Stratou C, Naparus A, Fisk N, Mehmet H. Functional intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways in human fetal mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Differ 2005, 12, 1439–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Briquet A, Dubois S, Bekaert S, Dolhet M, Beguin Y, Gothot A. Prolonged ex vivo culture of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells influences their supportive activity toward NOD/SCID-repopulating cells and committed progenitor cells of B lymphoid and myeloid lineages. Haematologica 2010, 95, 47–56. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.008524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Banfi A, Muraglia A, Dozin B, Mastrogiacomo M, Cancedda R, Quarto R. Proliferation kinetics and differentiation potential of ex vivo expanded human bone marrow stromal cells: implications for their use in cell therapy. Exp Hematol 2000, 28, 707–15. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary material.