Abstract

Communities in Indian Country across the U.S. are reconnecting to traditional and healthier food systems, often working explicitly for food sovereignty. This paper contributes to these reconnection efforts by (re)telling the story of the Northern Arapaho food system and the path we are creating toward health and our reclamation of Northern Arapaho food sovereignty. With support from my co-author, I approached data gathering and analysis in a blend of traditional native and conventional western research ways. I use the phrase “foreign intrusion” to help re-name eras in our history when our food system was altered by colonialism, forms of physical and cultural genocide, and assimilation. This “restorying” of the food system history of the Northern Arapaho people provides an indigenized frame for understanding our food system history, impacts of intrusion, and paths for reclaiming Indigenous food sovereignty. My methods include interviews with tribal members (N=16), three talking circles (N=14, 11, and 6), autoethnography, seven years of participation and observation in food sovereignty work, and document analysis, in addition to extensive literature reviews.

Keywords: Restorying, Food Sovereignty, Foreign Intrusion, Health Disparities, Indigenous, Native American, Food Dignity, Growing Resilience, Arapaho, Colonization

Introduction

By reclaiming our food sovereignty, Indigenous nations are also restoring our identities, cultures, his/stories, and traditions. In this research, as a Northern Arapaho tribal member, I aim to contribute to my people’s food sovereignty movement by reclaiming our food system story. For all Indigenous nations, recovering our food sovereignty is integral to our self-determination, cultural reclamation, economic development, and public health.

Over the last 200 years, the story of my community has been a brutally violent one. This was, at first, directly at the hands of foreign intruders (as I call them) and then, increasingly, by the long arms of the trauma they have systematically inflicted upon all Indigenous Nations in what is now the U.S. However, like all Indigenous Nations, nearly all of our history, including our food system history, happened before this foreign intrusion. Also, like other Indigenous Nations, we are now reclaiming our food, our health, and our stories. In this paper, I begin to reclaim the story of the Northern Arapaho food system for our tribe’s sovereignty and health.

This reclamation provides a stepping stone toward food sovereignty for Northern Arapaho people today and for other Sovereign Nations who share some of this history. It also provides one example for other Nations who find themselves on a similar journey to reclaim their own stories.

Background and Methods

Before foreign intrusion, Indigenous sovereignty included all North American lands and our ceremonial cycles, sacred places, and languages (Holm, Pearson, & Chavis, 2003). Then—as I discuss in this paper about Arapaho history particularly—our land, culture, food sources, and children were all stripped away by the intruders. Even the small swaths of reservation land assigned to us by treaties have been further diminished through broken treaties, the Dawes Act, and simple seizure by White encroachment.

These traumas and disruptions of intrusion have devastated our traditional foodways and our health (Kuhnlein & Receveur, 1996). For example, from 1492 to 1837, smallpox outbreaks decimated many Indigenous communities. Starting in the 1800s, many Native people starved as a result of the loss of food sources along with the loss of access to hunting, gathering, and growing lands (McGoldrick, Giordano, & Garcia-Preto, 2005). Today, the descendants of those who survived suffer among the worst health disparities in the U.S. (Jones, 2006; Porter, Wechsler, Naschold, & Hime, 2019).

However, as the collection of papers in this special issue show, we are reclaiming our health, our foodways, and our sovereignty. One means of this reclamation is decolonizing our stories of this history and the impacts on the life course of each Nation and Indigenous people as a whole (Oland, Hart, & Frink, 2012; Treuer, 2019). For our people to reclaim our history and our future, the right story, in both factual and ethical senses, needs to be told (King, 2005).

This paper aims to tell the story of the Northern Arapaho food system in a good and right way. Stories about Indigenous people’s food systems help explain and improve the understanding of the historical implications of colonization that have led to current food and health disparities (Kuhnlein, Erasmus, & Spigelski, 2009). Storytelling becomes a form of pedagogy when a story’s plot highlights human experiences and the narrative inquiry process illuminates cultural and historical contexts of that experience (Coulter, Michael, & Poynor, 2007). We use stories to develop, convey, and share knowledge, ethics, and paradigms across generations (Hodge, Pasqua, Marquez, & Geishirt-Cantrell, 2002). The Arapaho people use stories to document their histories from time immemorial, and as such, oral traditions are elements of our society that can only be told by a tribal member (Dorsey & Kroeber, 1997).

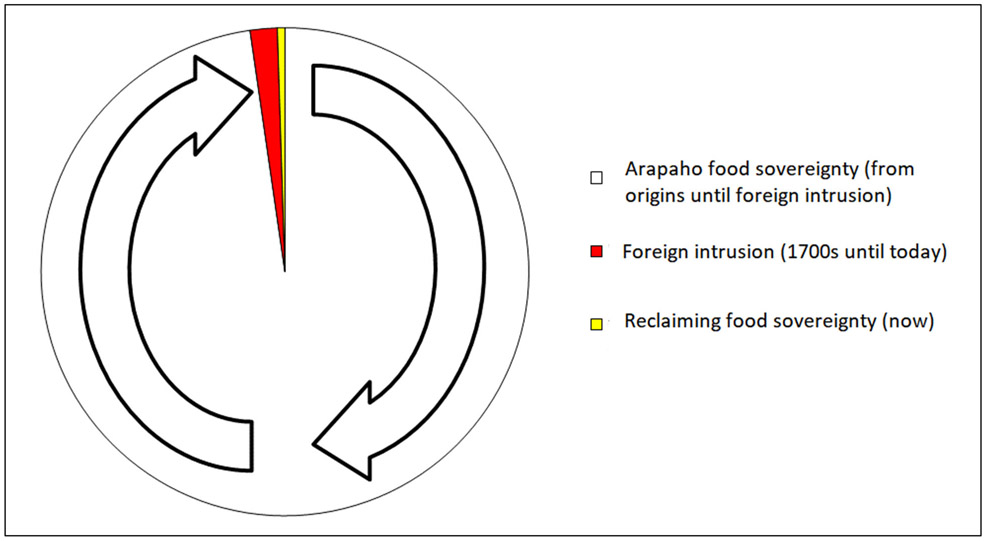

In this paper, I collect stories from the literature and Northern Arapaho people, analyze what Ollerenshaw & Cresswell call “key elements of the story” (2002, p. 332), and organize these elements into a coherent chronological narrative that restories the Arapaho people’s journey. For example, I illustrate our history with a time circle (Figure 1), mirroring Indigenous science, which views time as cycles (such as seasonal, lunar, and life cycles) rather than as linear “progress.” From a Native perspective, the term progress is a particularly inappropriate word to use, as one of the most recent slivers of time in our history is dominated by foreign intrusion (shown in red in Figure 1).

Figure 1. Time Circle History of the Northern Arapaho Food System.

A visual representation of the cycle of life for many Indigenous groups who believe that all life begins and ends with a rebirth, like the changing of the seasons. This figure depicts the perpetual and cyclical nature of the Arapaho food system. It illustrates how short the period of foreign intrusion is in relation to the overall history of the Arapaho people. It also shows the current sliver of hope that Indigenous food sovereignty movements today provide.

Setting

My tribe today is known as the Northern Arapaho. We are “Northern” because, by the 1850s, the intruders disrupted the natural migration of our buffalo herds which split us from our brothers and sisters, who joined our Southern Cheyenne cousins on Oklahoma reservations. Together, we are the Hinono’eiteen. Today, the Northern Arapaho people share the Wind River Reservation (WRR) with the Eastern Shoshone people.

WRR is the seventh-largest reservation in the U.S., with roughly 3,473 square miles (899,500 hectares) within the state of Wyoming. Approximately 27,088 people live within the reservation borders (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018). Nationally, approximately 10,000 people are enrolled Northern Arapaho tribal members, and 5,000 are enrolled as Eastern Shoshone, most of whom live on WRR or in small cities that are nearby (Wind River Native Advocacy Center, Wyoming Association of Churches, & Wyoming Office of Multicultural Health of the Wyoming Department of Health, 2016). Remarkably, on the reservation itself, the majority of people are Whites who lease or own what was originally reservation land (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018). On WRR, most Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone tribal members live on family lands originally allotted by the U.S. government around the turn of the century and that are now designated by tribal governments. The results section shares some of the history that has led to this current setting.

Authorship

Though I am an Indigenous person, I did not first learn a history of the Northern Arapaho from my people, through storytelling. The first version I learned was from conventional White history sources during my academic career. For example, in the U.S. children are taught that Squanto and Massasoit helped the Pilgrims survive in the new world in 1620, but history teachers do not teach children that 55 years later the colonists killed thousands of the Indigenous people and sold many into slavery. For my people, I learned about the Dawes Act of 1887, which led to so many non-Native people owning land on my reservation and aided the state of Wyoming in co-opting some of the best agricultural land in WRR, including building their city of Riverton within our collective home (Carlson, 1998; County 10, 2018).

That history makes me feel angry and, in part, drives the work I do today in food sovereignty with my people. Having first encountered this history only in adulthood, at a non-Native academic institution, and mostly told by non-Natives, also makes me feel angry, and that drives me to reclaim and restory this history about my people in this work here. I hope this example encourages other Native people to tell our own histories while also giving future generations a better chance of learning our stories from one another and not only from history as told by outsiders.

Some conventional Western scholars might have concerns that both my anger and my insider status could contaminate my objectivity. Both do affect my perspective, including the research questions I choose to ask, the methods I use to answer them, and my analysis of results. At the same time, one’s feelings and position affect this process for every scientist and scholar. As science philosopher Sandra Harding notes, objectivity is not neutrality, and our job in research is to strive for strong objectivity by naming and accounting for, as much as possible, our biases and our stances (Harding, 2000). I strive for that here, including by acknowledging my anger and openly conducting this research with the goal of retelling our story from an insider standpoint. This standpoint, I would argue, is at least as valid as the ones from which non-Natives have been telling stories, about us, from outside.

In addition, as Indigenous science philosopher and methodologist Shawn Wilson notes, research is relational, with the purpose of bridging the distances between the truths of our cosmos and us and between us (S. Wilson, 2008). Using the methods described below, I strive to generate these kinds of strongly objective and relational truths here.

In this paper, when I say “we,” I am referring to Northern Arapaho people specifically and, when relevant, Native people generally, including the Eastern Shoshone. We understand ourselves, in many ways, as one people (Anderson, 1994). Also, although I am writing this paper in the singular first person, I have a co-author. She is a White woman who was my chair when I completed much of this work for my master’s thesis as part of a project called Food Dignity. She is now principal investigator of a project called Growing Resilience, for which I am a currently a research scientist and from which I draw some of the data I analyze here. She has supported and guided my research, including helping me to share my work in this form.

This restorying research forms a small subset of two much larger action-research projects about food justice and sovereignty. One is the Food Dignity project, which supported and learned from five community-based food justice organizations about how to create sustainable and equitable community food systems (Porter, 2018). My co-author recruited me to become a master’s student with that project, from 2012 to 2015, with a focus on food sovereignty in WRR. She then secured NIH funding for a randomized controlled trial on the health impacts of home food gardening with 96 families in WRR. I am currently a research scientist for that project, which is called Growing Resilience. A community advisory board in WRR guides that project and the partner organizations that are implementing it. They strongly encouraged my interest in documenting impacts of the gardens with families well beyond the quantitative health indicators being gathered from participants. The data that I have gathered and analyzed for this research have been part of my work with these two projects.

Data Collection

My methodology is intended to fill gaps in our food system history by collecting the stories of our path away from and, more recently, back to self-sustainability and a sense of identity that promotes healthy Indigenous communities. My work is intended to share this restorying with all Sovereign Nations, both because of our partly shared history, and because all Nations need to reclaim and retell their stories. Also, both Natives and non-Natives should know this history of how we lost ownership of the food system as an element of our sovereignty, and how we are beginning to regain it.

To gather the diversity of data needed to tell our story, I used five different kinds of data collection, as described below. All data collection was approved by the University of Wyoming institutional review board and the governments of both Nations of WRR. Individual participants gave their signed, informed consent. In addition, Growing Resilience data gathering and this analysis were approved by the project’s community advisory board.

As part of my Food Dignity master’s thesis research, I conducted semistructured interviews (N=11) with Northern Arapaho tribal members in 2013. I invited community leaders who have or held professional positions in WRR in promoting our well-being and our sovereignty. I asked them to describe and discuss the food system in their community, for example, by asking, “can you please tell me about the food system in your community?” and following up with “what does that mean to you?” In addition, in 2018, a colleague and I invited the 10 families who participated in the first wave of Growing Resilience to tell their own stories about gardening and to choose their approach. Five asked to be inter-viewed, and so I conducted these interviews, asking them about their gardening experience, for example, and what they valued most about it and struggle with most. These were recorded and transcribed.

In 2017 and 2018, a colleague and I conducted three traditional talking circles as part of the Growing Resilience project. These are akin to focus groups, and holding a talking stick is used to represent whose turn it is to talk, while the others listen carefully. We invited all the heads of all 33 gardening families who were in the study at that time to participate in a talking circle. We held two talking circles with these gardeners (N=14 and N=11, representing 13 families). We showed a video produced by a gardener in the community (Potter, 2015) and asked them what the project and gardening mean to their family, and then asked how it impacts our communities. We also held a talking circle with the six members of the Growing Resilience Community Advisory Board, who used the session to tell the story of their experiences in the project to date. These were recorded and transcribed.

I have been participating in and observing the grassroots health and food sovereignty efforts in WRR since 2012. This has included serving as the market manager in the summer of 2012 for the tribal farmers market founded by Blue Mountain Associates (documented in a report I wrote for the organization that season), making many home garden visits (documented in field notes), and participating in dozens of related events and meetings involving health (documented in meeting notes and occasionally my field notes).

As noted above, my life story is embedded in the history of the Arapaho people. I grew up in WRR and am an enrolled member of the Northern Arapaho tribe. Thus, in part, this research is autoethnographic. When these stories are told by Indigenous people and intended to capture their experiences in conflict with dominant forces, their stories become a discursive power; they serve as truths that will not be forgotten (Denzin, 2006). I developed this research program as a response to finding non-Native versions of this history during my university studies and then determining I wanted to become involved in reclaiming Northern Arapaho food sovereignty and our collective story of its loss and our current work to regain it.

I have closely reviewed conventional academic literature and some local primary documents (e.g., media reports) and lesser-known scholarly produced locally about Northern Arapaho history.

In my analysis, described below, I triangulated this blend of methods and resulting data to develop, check, and validate the food system story for and of the Arapaho people.

Data Analysis

The focus of my data analysis was identifying the facts, memories, and interpretations of the Northern Arapaho food system history across all five types of data sources in order to weave them into one narrative. That narrative is the restorying of the Northern Arapaho food system, found in the results section.

I analyzed the transcripts of the interviews and talking circles in two ways. One, I employed a version of narrative inquiry, analyzing the stories people told holistically, for understanding of meaning and context. Particularly in Indigenous applications, narrative inquiry places life stories and relationships at the heart of analysis (Barton, 2004). I read and reread each transcript, highlighting particular stories and examining them overall for themes (Petty, Thomson, & Stew, 2012). I looked specifically for historical events that altered the food system for the Arapaho people, which helped shape the era definitions in the results. Two, I systematically coded the transcripts, using open coding and specifically looking for passages that related to the historical and current eras of our food system. Excerpts of what people told me during the Food Dignity project are indicated with (FD), and those marked with (GR) come from stakeholders in Growing Resilience. Quotations from both appear in italics.

I developed and divided the eras of our story further via my document and literature reviews. Finally, my last seven years of participation and observation, and an auto-ethnographic examination of my own life experience as a Northern Arapaho, inform my systematic analysis and interpretation of these data.

In the results section, I restory the history of the Northern Arapaho food system by weaving together the voices of interviewees and talking circle participants, voices of Native leaders and others as recorded in the literature, and legends and histories written by both Native and non-Native historians. I have also shared and checked this story with dozens of people in and from WRR.

Restorying Northern Arapaho Food Systems for Sovereignty

We are all human beings. Every one of us has a tribal ancestry and we have a genetic memory and encoded on that genetic memory is the experience of our individual and collective evolution. The information is there, because we’re human beings the knowledge of all those experiences are with us.

—Trudell (2008, p. 319)

In the beginning

The land of this world and the Arapaho people were born and borne on the back of the Turtle (see, for example, Dorsey & Kroeber, 1997; King, 2005).

Most of Our Story

The ancestors of the original Arapaho bands journeyed into North America, surviving on what the land had to offer. Foreign intrusion interrupted the recording of our histories in this time, knowledge that should have been shared with my generation today through storytelling, from one generation to the next. However, regardless of how much we know now about this period, starting with our creation and arrival in North America, it clearly composes nearly all of our temporal history (Figure 1).

Piecing together what stories we do have and the relationship of our language to the Algonquin family, we likely lived near the Great Takes, combining some agriculture with travel for hunting and gathering wild foods (Anderson, 1994; Dorsey & Kroeber, 1997). We may also have, or instead, centered our lives in the Great Plains that are now South Dakota, Eastern Wyoming, and Northern Colorado. Either way, during that time, we cultivated some of our food and likely gathered and hunted for the rest. This included the buffalo, who once ranged in the tens of millions across most of what is now the United States. The buffalo not only provided us with food, tools, clothing, and shelter, but also gifted us our ceremonial lodges (see stories 6 and 9 in Dorsey & Kroeber, 1997).

As with all humans at that time, lives were generally shorter than they are now. However, as one storyteller noted, A long time ago the Arapaho survived on what they could get from nature. … We were a lot healthier people back then [FD].

Foreign INTRUSION

Then, when Europeans began colonizing North America, everything changed for us, including our food system.

Pushed west, but gaining guns and horses (1700s—early 1800s)

As colonizing Europeans forced Indigenous peoples of the east off their lands—via disease, direct violence, and displacement—the Indigenous people of central North America, including the Arapaho, were slowly pushed west. For example, in the early 1800s, Lewis and Clark mention meeting Arapaho people in what is now central Colorado (Hilger, 1952). In 1780, the Arapaho population was approximately 3,000 and the food systems of the Indigenous people generally who were migrating out west were evolving rapidly with the new tools they acquired from Europeans (Lowie, 1982). Given the destruction this foreign intrusion would ultimately wreak on my people, I find some irony in describing this period as, in some ways, a golden age for food provisioning. Guns and horses made hunting for food, especially buffalo, so much easier (Schilz & Worcester, 1987). Many Arapaho people lived in and around what is now Rocky Mountain National Park, where they followed the buffalo through the mountain area (Toll, 2003).

Making treaties (late 1800s)

As colonizers increasingly intruded on western lands, they begin to erode the Arapaho way of life and our food system. In 1850, the territories of Wyoming, Kansas, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, New Mexico, and Colorado were occupied by 274,139 Europeans (Anderson & Hill, 1975), putting the Arapaho in direct contact with Europeans and being far outnumbered by them. The U.S. government began demanding that tribes sign treaties, which formally began the policy of separating Indigenous populations in the Great Plains from their land and sustenance and confining us to “reservations.” Table 1 summarizes the treaties signed between the U.S.and the Arapaho people and their more particular implications for food systems.

Table 1.

Arapaho-U.S. Government Treaties (all broken by the U.S.)

| Treaty: Focus | Food System Implications |

|---|---|

| Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851: Ensuring tribal land rights and the safe passage of Whites on the Oregon Trail. | Arapaho guaranteed lands stretching across what is today’s eastern Colorado and parts of Wyoming, Nebraska, and Kansas. Encroachments disrupted natural migration of buffalo. |

| Treaty of Fort Wise, 1861: U.S. demands that the Arapaho and Cheyenne chiefs who signed cede most of the land guarantees above. | First formal loss of land by treaty, including most traditional Arapaho hunting grounds and nearly all the land scoped by intruders in 1851. |

| Little Arkansas Treaty, 1865: Set of treaties with U.S. promising large swaths of reservation lands for Arapaho and others. | U.S. never created most of the promised reservations and took back the land for the few they did create. |

| Medicine Lodge Treaty, 1867: Three treaties reshaping the reservations promised above, with much smaller areas. Launched the era of reservations. | Included provisions for buffalo hunting rights and 4.3 million acres for a Cheyenne and Arapaho reservation (Boissoneault, 2017). |

| Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868: U.S. aims to end wars and defend land against intruders with promises of some land for participating tribes (especially the Sioux) and incentives to settle on reservations, such as cash payments for farming. | By this time, the group that became the Northern Arapaho was eking a living from a limited range of prairie with no U.S.-designated land and diminishing buffalo herds. This treaty did not improve their circumstances. |

Tribes did not, of course, wish to relinquish our lands and, by this loss, our lives, through any of these treaties. However, as the U.S. government and its citizens intruded farther into and across the west, Indigenous people sought to protect ourselves and our ways of life. Sometimes this included violence, whether directly against U.S. troops or colonizers, or aligning with U.S. troops against other Indigenous communities under increasing competition for the diminishing sustenance the remaining lands could provide. For example, Arapaho and Cheyenne warriors raided wagon trains entering their lands as the buffalo were depleted intentionally by U.S. policy (more on this below) and by disruption of their migration patterns by European colonization and introduction of cows (Berthrong, 1976). The U.S. wished to protect its colonizers and its growing extraction of resources such as gold and forced us into such treaties. For example, one Cheyenne leader at the signing of the Medicine Lodge Treaty noted, “You think you are doing a great deal for us by giving these presents to us, but if you gave us all the goods you could give, yet we would prefer our own life. You give us presents and then take our lands; that produces war” (Boissoneault, 2017, p. 3).

Sand Creek Massacre (1864)

In the camp all was confusion and noise… [Black Kettle] kept calling out not to be frightened that the camp was under protection… then suddenly the troops opened fire on this mass of men, women, and children. … White Antelope, when [he] saw the soldiers shooting into the lodges, made up his mind [to] not live any longer… he crossed his arms singing the death song.

—A White witness, George Bent (Bent & Hyde, 1968, p. 155)

When the U.S. government violated the Treaty of 1861 (Table 1), and the Arapaho and Cheyenne elders were forced to agree to surrender their primary hunting grounds, many warriors did not agree. Also by this time, some Arapahos continued to hunt in territories that include what is now eastern Wyoming, while others were trying to sustain a living in the more heavily colonized area of what is now northern Colorado. In addition to fights for territory, some groups raided intruding settlements for food, particularly in the more populated areas around Denver (Scott, 1994). In 1864, one group of (Southern) Arapaho and Cheyenne people was camping at Sand Creek there, with the permission and promised protection of the U.S. government. This group was not involved in such raids. Yet, on November 29, 1864, Army Col. Chivington ordered his soldiers to massacre the group. A group of drunk members of the U.S. military attacked its camp, killing over 100 people, mostly woman and children. They died in the snow, with their bodies mutilated by the soldiers (Roberts, 1984). A U.S. senator of Wisconsin was then called in to investigate the Indigenous people’s conditions and found that they were starving because of large-scale corruption by Indian agents (Chaput, 1972). After this massacre, both Arapaho groups, southern and northern, increased their resistance to the growing foreign intrusion.

Buffalo slaughter (1865–turn of the century)

The Indian, in truth, has no longer a country. His lands are everywhere pervaded by white men; his means of subsistence destroyed and the homes of his tribe violently taken from him, himself and his family reduced to starvation.

—U.S. Major General Pope, writing to his supervisor in 1865 (U.S. War Department, 1896, p. 1151)

Under the guidance of General Sheridan and General Sherman, the U.S. Department of War devised a genocidal plan to finish off the remaining Indigenous people of the Great Plains, whether by death or confinement to reservations. This was done by eliminating our primary food source, the buffalo (Smits, 1994). Sheridan described this as “destroying the Indian’s commissary” (Phippen, 2016, p. 1). A U.S. Army colonel named this more directly with, “Kill every buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone” (Phippen, 2016, p. 1). With this approach, the U.S. reduced herds of tens of millions of buffalo to just a few thousand or possibly just hundreds.

Move to a reservation (1878)

Some tribes fought for their lives and ways of life by strategically collaborating at times with the U.S. military, whether regularly or just intermittently when useful to defend territory against unrelated Indigenous groups. This may have occurred particularly when such groups had competed for hunting and gathering territory even before foreign intrusion, a competition which intensified as the intrusion depleted resources. Though not perhaps reaching these levels of enemy status, the historical relations between the Eastern Shoshone and Arapaho were fraught, with Shoshone living in what is now western Wyoming and Arapahos in the east, both with food systems anchored by the buffalo. Also, we come from very different cultural and linguistic backgrounds, with the Shoshone arriving in that area from the west, and my people from the east.

The Shoshone also participated in both Fort Laramie treaties and additionally signed the Fort Bridger Treaty of 1868 (also known as the Shoshone Bannock Treaty). That treaty established the “Shoshonee reservation,” which included the current-day WRR and much more. The northern group of Arapaho, however, were “granted” no land by the U.S. government anywhere near our home territories. Also, our prospects for one in or near current Wyoming were dwindling, along with our ability to survive in increasingly colonized land.

In spite of some skirmishes between my people and the Shoshone in this period, talks between the Shoshone leader and several Arapaho chiefs, combined with pressure from the U.S. government (who wanted to get the remaining Arapaho onto a reservation), led to the Shoshone agreeing to let the remaining Northern Arapaho move to their reservation in the winter of 1878. Thus began our reservation life.

Reserved Life (1878 to today)

Early reservation life (1878–early 1900s)

Lack of access to our traditional food system forced us onto a reservation, but we did not find much respite from hunger there either. Sherman Sage, a Northern Arapaho man who lived from 1843 to 1944, says of early reservation life that “epidemics, meager rations, poverty, poor housing, and permanent settlement kept the death rate higher than the birth rate” (Anderson, 2003, p. 60). Similarly, one interviewee reflected:

I think the problems go back to early Reservation days, they couldn’t hunt, fish, and they couldn’t grow vegetable gardens. We were a starving people, and there were a lot of malnutrition and health problems, and that’s where it started, when we got off of the buffalo and the healthier foods. [FD]

Having succeeded in either killing or confining most Native Americans of the Great Plains at this point, the U.S. government then rolled out two additional strategies to reduce or eliminate us. One aimed to reduce reservation lands even further by allotting “unused” lands to Whites and privatizing even Native land ownership; this was the Dawes Act of 1887 (also known as the General Allotment Act). For WRR, these losses were compounded by the McLaughlin Agreement of 1905 (Agreement with the Shoshone and Arapahoe Tribes of Indians Belonging on the Shoshone or Wind River Reservation, 1905). This agreement, specific to WRR (which by this time was called, in that Agreement, “The Shoshone or Wind River Reservation”), ceded nearly 1.5 million acres (607,000 ha). Though some of these lands were later restored, these policies as combined enabled Whites to found the city of Riverton on our land and many farms on our best agricultural lands. As one person noted:

I have mixed feelings about the way the land was acquired and the way it was homesteaded and opened up with the tribes not in a good bargaining position to do anything about it, and then all the money went to the wet irrigators and the wet system and very little to the reservation side. [FD]

The government also founded its cultural genocide strategy of boarding schools, starting with Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania in 1879. These schools were designed, as one Army captain put it, to “kill the Indian in him, and save the man” (Lomawaima & Ostler, 2018). The schools treated captive students so terribly that often the “man” was killed also. The remains of five Northern Arapaho teenagers who died and were buried at Carlisle were recently returned to us. However, WRR also had two local boarding schools. One, which still exists today as a day school, was the St. Stephens Mission. Today, some recall this school as helping to show the way toward producing enough food on WRR to sustain ourselves. For example, one elder recalled,

I’ve been talking with one of the elders around who was born in 1924, and he had gone to school at St. Stephens in 1930; it was a self-sustaining community. They had their own beef, chickens; they did all their own processing. They grew huge gardens, and that supported everybody. [FD]

Also during this period, federal agents established demonstration farms and made other efforts to encourage Arapahos to begin our agricultural lives again. However, after generations of hunting and gathering on the plains, alongside the physical and emotional toll of living on a reservation, these efforts did not take root.

Learning to live on WRR (early to mid-1900s)

Government-issued food rations, aimed to lure increasingly starving Indigenous people to reservations, starting in the late 1800s. By the early to mid-1900s, these commodity foods had become staple parts of our diets, including the invention of fry bread, made with the flour and lard provided (Vantrease, 2013). Through the federal gardening promotion programs of the two world wars, home gardening was also increasing. We also began hunting again, mainly for small game, but also able to find pronghorn, deer, and sometimes elk or moose. As one person remembers fondly,

When I was growing up me and my sisters and brother-in-laws would go hunting and get an elk, and then they would skin it and butcher it, and the hindquarters and meat would go on the table, and my Mother would be sharpening the knives. And then we would all sit around and then that’s when we would slice the meat. [FD]

Also, a few Arapaho families began farming and with some federal support, the tribe founded the Arapaho Tribal Ranch in 1940, with about 5,000 cattle (Wilson, 1972), which is still in operation today (http://www.arapahoranch.com/). One elder recalls, I see where people were a lot closer, family members especially when we harvested our, our grain or our fields in the fall time [FD].

Transition from starving to stuffed (from the mid-1900s)

Within the constraints of reservation life and the traumas of this history revisited on our communities, families, and bodies, the 1950s and 1960s were a nutritional recovery period of sorts for us, in between starved and stuffed.

Young tribal leaders came home from WWII as respected heroes. What I will call the U.S. food machine, of both federal feeding programs and industrial food processing, were becoming established and available to our families in WRR. Cooking and ranching skills were being passed down to younger family members, and there was an influx of goods such as cars and farm equipment. Gardens became common, partially thanks to the tribal arms of the Victory Garden programs (Lawson, 2005). Two tribal members recall how things were growing up on the reservation in this period:

When I was growing up my folks had a big old huge garden, and we never bought food from town, and when we got hungry we just run out to the garden and get us a turnip or carrots or something then we’d take off again, we’d go cruising, or go back to the river to swim, or horseback riding, we always had something to do. [GR]

When I was young, we still survived on a lot of wild game—deer, elk, elk meat, and we’d even eat rabbits and pheasant. [FD]

Community feasts were still an important part of tribal members’ diets, as the wives of elected committee officials (who were nearly always men) provided stew, fry bread, and chokecherry gravy for Christmas feasts. Such feasts included dancing and hand games until one in the morning, and losers of the gambling would provide meals for the next night’s games. These meals would sometimes include ham hocks, dried corn, Indian corn, and a cow or big game animals such as deer and elk. A Northern Arapaho tribal elder recalled the early 1950s when community and tribalism were very important in providing nourishment to all people in the community:

We used to have a Christmas Committee who would raise money to have feasts. Everybody took part, and people would go eat, then dance, they would give them extra meat and filled their soup buckets to take home. [FD]

Overall, in the 1950s, we were living on wild game (both big and small), the government rations, and what could be grown in home and community gardens. The national-level trends of switching to getting produce and other food from grocery stores came more slowly to the reservation. New things like candy and pop would be given as treats, and divided out to kids in portions because they were expensive. Tribal members on the reservation canned a lot of the produce they grew, and 4-H programs also helped to keep farming and gardening intergenerational.

In the 1960s, we began to receive checks from the government for the natural resources extracted from our land. Before this time, people generally did not have money unless they had a job, and jobs were rare. The food commodity programs also became a more reliable source of food for us. The food shared during annual feasts and beyond immediate family was increasingly sourced from the conveniences offered from grocery markets and focused on what White people call “nuclear” families. Many participants explained that during this time they “just got away from that,” referring to things like language, sustainability, sharing, tribalism, culture, and happiness, for example:

They got away from creating their own food from scratch, and bought the products and they would make a stew or a meal from that processed stuff, and not create a dish from scratch anymore. [FD]

Trauma + U.S. food machine = Disparities, diabetes, and death (from the 1970s)

By the 1970s, the effects of foreign intrusion on the Northern Arapaho food system were relatively complete. Historical trauma is the culmination of and reaction to the massive acts of violence and oppressive conditions that have been inflicted on a group, which are now embedded in every fabric of their society (Yellow Horse Brave Heart, 2003). The trauma of the transitions above (including the cultural genocidal tactics of boarding schools) combined with per capita cash infusions from mineral royalties had nearly severed us from our traditions and embedded us in the mainstream capitalistic economy, albeit with meager opportunities to participate in the waged economy. For example, even families who hunted often no longer did the traditional processing of their own wild game, including hanging the meat outside the house so people would stop in to visit and get a portion. One person lamented: We’ve just gone, gotten away from that. Nobody does that anymore out here. It’s much easier just to go to the store and buy, buy what you need and that’s not always healthy [FD].

The impact of the USDA Food Distribution program on the Native American diet was also a form of intrusion when Native Nations were given mass quantities of unhealthy and culturally inappropriate foods. This dietary change hit us with a growing supply of the sugar, fat, and salt found in the canned pork, canned chicken, canned beef, butter, corn syrup, and cheese. The program also led toa lack of fresh fruits or vegetables. People relied on unhealthy commodities in a community that was still poverty-stricken (Mailer, & Hale, 2013). As one person noted, That’s where our biggest health problem comes from, those canned commodities, and that’s what contributed to obesityq [FD].

Similar to the rest of the U.S., we also increased our reliance on fast, industrial, processed foods, particularly in the 1980s and ’90s. One Arapaho tribal member and mother of three recollected that In the ’80s, you know here comes the pizza, some sodas, fast food, so when I was working and never had time, that’s what my kids would get, they were kind of a little bit hefty in them days [FD]. Another lamented that today, so a lot of people don’t grow, they don’t grow vegetable gardens, they don’t grow fruit trees, so they get that a lot from the town, neighboring towns. When we got away from that, that’s when a lot of the health problems started [FD].

One result has been that the Native people of WRR have some of the worst health in the nation, often even in comparison with other Indigenous communities in the U.S. (Porter, Wechsler, Naschold, & Hime, 2019). As a Northern Arapaho tribal social worker reported, I work with a lot of kids, and some of them have diabetes. And it’s just really hard for them because they just want to be kids and they have to monitor their blood and what they eat, and they just seem so tired of having to do that every day [FD]. At the same time, many of us are food insecure; as she also notes, A lot of instances, they’re basically in survival mode, and there’s children that go to school, and hoard it because a lot of times they were deprived of just basic food, and they’re afraid of being hungry so they’ll take a piece of bread in their pocket [FD].

Reclaiming Food Sovereignty (the Next Seven Generations)

I did not grow up hearing our stories told in traditional ways. However, some I have caught in whispers, or fragments. One of these stories is that the seventh generation after the onset of the brief (compared to our overall history) but brutal foreign intrusion into our daily lives would rise to help restore health and sovereignty to our people. Some say that this generation’s time has arrived, with my generation.

I am in my late 40s. Many of us from my generation, including many of my elementary school classmates, are no longer with us. Whatever the most proximate causes, none of the deaths I know of have been, in a larger sense, “accidents.” Those of us who remain, as in the previous seven generations, are survivors. We are resilient. And, with the Eastern Shoshone and many other Indigenous Nations, we are reclaiming our food systems, our health, and our sovereignty. Here are some examples of how we are doing this in WRR.

In WRR, Blue Mountain Associates helped to found the first tribal farmers market in 2010. Deploying funding from the Food Dignity project, they then expanded the market, formed a steering committee, supported home gardens and chicken coops, helped such producers become vendors, and more. This year, they added the first winter market season. Also, since 2012, Blue Mountain Associates has been providing the garden installation and support for the pilot and then the full-scale Growing Resilience project.

In 2013, one of the Arapaho leaders I spoke with wished to see us return to eating buffalo:

What I’d like to see is the buffalo come back to the people. And I’d really think the Tribe should consider getting land for the buffalo. I mean the buffalo are part of the Arapaho people, it is still in our ceremonies. The buffalo still symbolizes strength and everything that is good. And if we went back to the buffalo diet, our people would become happy again. [FD]

She also worried about some barriers to that, noting, But they are so accustomed to eating that beef Then, in 2016, the Shoshone tribe introduced a herd of 10 buffalo. With one calf born and 10 additions to the herd in 2017, they are now at 21. The vision is for a herd of a thousand to range free again on this land and to again become a source of sustenance (Voggesser, 2017).

While Blue Mountain Associates has continued its food sovereignty efforts, other groups have also begun leading this kind of work. For example, the Restoring Shoshone Ancestral Food Gathering group is reclaiming and sharing gathering and cooking practices. The Growing Resilience Community Advisory Board, in addition to overseeing that project, has established a new community demonstration garden. A multiyear effort to found a producers cooperative and more, called the Wind River Food Sovereignty Development Project, recently received federal funding (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2018). The Growing Resilience project overall is supporting nearly 100 families in creating and nurturing home food gardens. As one participant said, this garden isn’t just for me, it’s a way to carry on the tradition [GR].

People have expressed hope, ideas, and some new perspectives on the future of our food system. Growing our own food was one theme mentioned by interviewees during Food Dignity (which was part of the evidence of interest that spurred my co-author to suggest the Growing Resilience project). For example, one person told me:

I’d just like to see, you know, like programs like you’re involved in, to be increased to get more resources to, to reach more people. Because I think that we need to go back to living off the land, being outside, appreciating the outdoors and, and seeing things grow and getting the, the satisfaction of, of nurturing plants and things like that. [FD]

Some of the gardeners in the Growing Resilience project said they want to see food growing spread:

I think one way is to get gardens in schools, having each grade be responsible for a greenhouse at the high school, it would be nice getting them involved in gardening. [GR]

In the community, too, if everybody knows that you’re growing a garden, they’re like “Hey [she’s] growing a garden, we could do that.” A lot of people don’t have positive out here, they have so much negative, so if they could do that and put all their energy into that it will help them be less stressful and responsible and feel like they accomplished something rather than not doing anything. [GR]

Also, one person challenged the commodified history that inserted fry bread into our food system:

When I was younger, people would call fry bread traditional food, but it isn’t really a traditional food. It has kind of evolved into traditional food for us, because anytime you have a gathering, you always have fry bread. [FD]

Another saw some hope, albeit tempered by experience, that we were shifting toward healthier foods in WRR:

It seems to me like there’s a lot more interest in eating local and eating more organic, but having been a child of the ’60’s in a lot of ways, there was a big movement back then too, sort of like the hippie movement. I am a little concerned that it, like in the ’60’s, that it’s a trend and it’ll die out.… I hope this is a revolution.[FD]

Implications and Conclusion

Every Sovereign Nation in what is now the U.S. shares an overarching story of millennia where we fed our people and nurtured our well-being in relationship with one another and the land. Although our collective lives then included struggle and suffering, including sometimes wars or starvation, they also were our own to lead, in our own ways. Every Sovereign Nation in what is now the U.S. also shares much more recent overarching story of foreign intrusion. Our struggles and our suffering multiplied as our people were killed—by starvation, disease, despair, and direct attacks—and by having our land, foodways, and children stripped away.

One way to tell this story is from the perspective of the foreign intruders, for example, of Manifest Destiny. Another way to tell this story is how I have done so here, with and of the Northern Arapaho people, about the history of our food system, the loss of food sovereignty and health through intrusion, and our nascent efforts to reclaim both.

In this restorying, people spoke of language, culture, food, health, and gardening “getting away” from us as a people. We associate the loss with what is missing in the community today, and are now working to get it back. Food system work and fighting for our food sovereignty are crucial means for all Indigenous nations to reclaim all of this—our culture, history, health, and political sovereignty.

I hope other Indigenous nations hear parts of their own stories in this restorying in the WRR of the Northern Arapaho food system, and I hope this example will inspire others to reclaim our collective and specific stories as we restore Indigenous food sovereignty across North America. It offers, in a small and short way, rigorous and Indigenous storytelling about one Indigenous food system, as Dunbar-Ortiz (2014) and Treuer (2019) have recently done for our overall collective histories.

I would like to conclude with a revolution—including a revolution of seasons, as we pass out of the winter of foreign intrusion into a spring of Northern Arapaho, Eastern Shoshone, and Indigenous Nation food sovereignty. I have strived to tell this story in a good way, with hope that it may help us find our way.

Acknowledgments

As lead author, I would like to thank my co-researcher Rachael Budowle, the members of the Wind River Reservation community, and all my colleagues and students who volunteered to work on the Food Dignity and Growing Resilience projects, especially those who have instrumental in completing talking circles and sovereign stories about home gardening and the path back to food sovereignty.

Funding Disclosure

Food Dignity (http://www.fooddignity.org) is supported by Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grant no. 2011-68004-30074 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Growing Resilience is funded by NHLBI with NIGMS at the National Institutes of Health with grant no. R01 HL126666-01.

References

- Agreement with the Shoshone and Arapahoe Tribes of Indians Belonging on the Shoshone or Wind River Reservation, 58 U.S.C. Sess. III, Chap. 1452 (1905).

- Anderson JD (1994). Northern Arapaho knowledge and life movement (Doctoral dissertation). University of Chicago, Illinois. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JD (2003). One hundred years of Old Man Sage: An Arapaho life. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson TL, & Hill PJ (1975). The evolution of property rights: A study of the American West. Journal of Law and Economics, 18(1), 163–179. 10.1086/466809 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton SS (2004). Narrative inquiry: Locating Aboriginal epistemology in a relational methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 45(5), 519–526. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02935.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bent G, & Hyde GE (1968). Life of George Bent written from his letters. Norman: Oklahoma University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berthrong DJ (1976). The Cheyenne and Arapaho ordeal: Reservation and agency life in the Indian Territory, 1875–1907. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boissoneault L (2017, October 23). How the 1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty changed the Plains Indian Tribes forever. Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-1867-medicine-lodge-treaty-changed-plains-indian-tribes-forever-180965357 [Google Scholar]

- Carlson PH (1998). The Plains Indians (No. 19). College Station: Texas A&M University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chaput D (1972). Generals, Indian agents, politicians: The Doolittle Survey of 1865. The Western Historical Quarterly, 3(3), 269–282. 10.2307/967424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter C, Michael C, & Poynor L (2007). Storytelling as pedagogy: An unexpected outcome of narrative inquiry. Curriculum Inquiry, 37(2), 103–122. 10.1111/j.1467-873X.2007.00375.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- County 10. (2018, May 19). Trump Administration will not support EPA’s Reservation boundary decision. Retrieved from https://archive.county10.com/breaking-trump-administration-will-not-support-epas-reservation-boundary-decision [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK (2006). Analytic autoethnography, or deja vu all over again. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(4), 419–428. 10.1177/0891241606286985 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey GA, & Kroeber AL (1997). Traditions of the Arapaho. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar-Ortiz R (2014). An Indigenous peoples’ history of the United States. Boston, Massachussetts: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harding S (2000). After the neutrality idea: Science, politics, and “strong objectivity.” In Jacob MC (Ed.), The Politics of Western Science, 1640–1990 (pp. 81–101). Amherst, New York: Humanity Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hilger MI (1952). Arapaho child life and its cultural background. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology (Bulletin 148). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/15443/bulletin1481952smit.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hodge FS, Pasqua A, Marquez CA, & Geishirt-Cantrell B (2002). Utilizing traditional storytelling to promote wellness in American Indian communities. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 13(1), 6–11. 10.1177/104365960201300102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm T, Pearson JD, & Chavis B (2003). Peoplehood: A model for the extension of sovereignty in American Indian studies. Wicazo Sa Review, 18(1), 7–24. 10.1353/wic.2003.0004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DS (2006). The persistence of American Indian health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 96(12), 2122. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King T (2005). The truth about stories: A Native narrative. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnlein HV, Erasmus B, & Spigelski D (2009). Indigenous peoples’ food systems: The many dimensions of culture, diversity and environment for nutrition and health. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/docrep/012/i0370e/i0370e00.htm [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnlein HV, & Receveur O (1996). Dietary change and traditional food systems of indigenous peoples. Annual Review of Nutrition, 16(1), 417–442. 10.1146/annurev.nutr.16.1.417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson LJ (2005). City bountiful: A century of community gardening in America. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lomawaima KT, & Ostler J (2018). Reconsidering Richard Henry Pratt: Cultural genocide and Native liberation in an era of racial oppression. Journal of American Indian Education, 57(1), 79–100. 10.5749/jamerindieduc.57.1.0079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lowie RH (1982). Indians of the Plains. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mailer G, & Hale N (2013). Decolonizing the diet: Synthesizing Native-American history, immunology, and nutritional science. Journal of Evolution and Health, 1 (1), Article 7. 10.15310/2334-3591.1014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGoldrick M, Giordano J, & Garcia-Preto N (Eds.). (2005). Ethnicity and family therapy. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oland M, Hart SM, & Frink L (Eds.). (2012). Decolonizing indigenous histories: Exploring prehistoric/colonial transitions in archaeology. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ollerenshaw JA, & Creswell JW (2002). Narrative research: A comparison of two restorying data analysis approaches. Qualitative Inquiry, 8(3), 329–347. 10.1177/10778004008003008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petty NJ, Thomson OP, & Stew G (2012). Ready for a paradigm shift? Part 2: Introducing qualitative research methodologies and methods. Manual Therapy, 17(5), 378–384. 10.1016/j.math.2012.03.004 P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phippen JW (2016, May 13). Kill every buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2016/05/the-buffalo-killers/482349/ [Google Scholar]

- Porter CM (2018). Triple-rigorous storytelling. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 8(Suppl.1), 37–61. 10.5304/jafscd.2018.08A.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter CM, Wechsler A, Naschold F, & Hime S (2019). Adult health status among Native American families participating in the Growing Resilience home garden study. Preventing Chronic Disease, 6, 190021. 10.5888/pcd16.190021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter E (Producer). (2015). Growing gardens…and kids. Paths to Food Dignity [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zuMNSAH6zIE [Google Scholar]

- Roberts GL (1984). Sand Creek: Tragedy and symbol (Doctoral dissertation). The University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma. [Google Scholar]

- Schilz TF, & Worcester DE (1987). The spread of firearms among the Indian tribes on the Northern frontier of New Spain. American Indian Quarterly, 11(1), 1–10. 10.2307/1183724 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott R (1994). Blood at Sand Creek: The massacre revisited. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smits DD (1994). The frontier army and the destruction of the buffalo: 1865–1883. Western Historical Quarterly, 25(2), 313–338. 10.2307/971110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toll OW (2003). Arapaho names and trails: A report of a 1914 pack trip (Revised ed.). Estes Park, Colorado: Rocky Mountain Nature Association. [Google Scholar]

- Treuer D (2019). The heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the present. New York: Riverhead Books. [Google Scholar]

- Trudell J (2008). The power of being a human being. In Nelson MK (Ed.), Original instructions: Indigenous teachings for a sustainable future (pp. 318–323). Rochester, Vermont: Bear & Co. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2018). Wind River Reservation and off-reservation trust land, WY. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/tribal/?aianihh=4610 [Google Scholar]

- U.S. War Department. (1896). The war of the rebellion: A compilation of official records of the Union and Confederate armies. United States Congressional Serial Set, Series I, Volume XLVIII, Part II—Correspondence Etc., Document 369. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2018). Transportation and marketing, Local Food Promotion Program: Fiscal year 2018 description of funded projects. Retrieved from https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/2018DescriptionofFundedProjectsLFPP.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Vantrease D (2013). Commod bods and frybread power: Government food aid in American Indian culture. Journal of American Folklore, 126(499), 55–69. 10.5406/jamerfolk.126.499.0055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Voggesser G (2017). Buffalo break new trails on Wind River [Blog post]. Retrieved from the National Wildlife Foundation; blog: https://blog.nwf.org/2017/10/buffalo-break-new-trails-on-wind-river/ [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PB (1972). Farming and ranching on the Wind River Indian Reservation, Wyoming (Doctoral dissertation). University of Nebraska at Lincoln. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/dissertations/AAI7315406/ [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Black Point, Nova Scotia: Fernwood Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wind River Native Advocacy Center, Wyoming Association of Churches, & Wyoming Office of Multicultural Health of the Wyoming Department of Health. (2016). In the heart of Wyoming is Indian Country: Home to the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribes. Retrieved from https://health.wyo.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/WR-EducPub2016.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Yellow Horse Brave Heart M (2003). The historical trauma response among Natives and its relationship with substance abuse: A Lakota illustration. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 35(1), 7–13. 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]