Abstract

Background:

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a large class of synthetic (man-made) chemicals widely used in consumer products and industrial processes. Thousands of distinct PFAS exist in commerce. The 2019 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Action Plan outlines a multiprogram national research plan to address the challenge of PFAS. One component of this strategy involves the use of systematic evidence map (SEM) approaches to characterize the evidence base for hundreds of PFAS.

Objective:

SEM methods were used to summarize available epidemiological and animal bioassay evidence for a set of PFAS that were prioritized in 2019 by the U.S. EPA’s Center for Computational Toxicology and Exposure (CCTE) for in vitro toxicity and toxicokinetic assay testing.

Methods:

Systematic review methods were used to identify and screen literature using manual review and machine-learning software. The Populations, Exposures, Comparators, and Outcomes (PECO) criteria were kept broad to identify mammalian animal bioassay and epidemiological studies that could inform human hazard identification. A variety of supplemental content was also tracked, including information on in vitro model systems; exposure measurement–only studies in humans; and absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME). Animal bioassay and epidemiology studies meeting PECO criteria were summarized with respect to study design, and health system(s) were assessed. Because animal bioassay studies with exposure duration (or reproductive/developmental study design) were most useful to CCTE analyses, these studies underwent study evaluation and detailed data extraction. All data extraction is publicly available online as interactive visuals with downloadable metadata.

Results:

More than 40,000 studies were identified from scientific databases. Screening processes identified 44 animal and 148 epidemiology studies from the peer-reviewed literature and 95 animal and 50 epidemiology studies from gray literature that met PECO criteria. Epidemiological evidence (available for 15 PFAS) mostly assessed the reproductive, endocrine, developmental, metabolic, cardiovascular, and immune systems. Animal evidence (available for 40 PFAS) commonly assessed effects in the reproductive, developmental, urinary, immunological, and hepatic systems. Overall, 45 PFAS had evidence across animal and epidemiology data streams.

Discussion:

Many of the PFAS were data poor. Epidemiological and animal evidence were lacking for most of the PFAS included in our search. By disseminating this information, we hope to facilitate additional assessment work by providing the initial scoping literature survey and identifying key research needs. Future research on data-poor PFAS will help support a more complete understanding of the potential health effects from PFAS exposures. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP10343

Introduction

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a large class of synthetic compounds with widespread presence used in consumer products and industrial processes. The core structure of PFAS consists of a carbon chain attached to multiple fluorine atoms, with different chemicals possessing different end functional groups. There is no single consensus definition of PFAS. Buck et al.1 defined PFAS as fluorinated substances that “contain 1 or more C atoms on which all the H substituents (present in the nonfluorinated analogues from which they are notionally derived) have been replaced by F atoms, in such a manner that they contain the perfluoroalkyl moiety .” Other definitions of PFAS include the Office of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) definition, “fluorinated substances that contain at least one fully fluorinated methyl or methylene carbon atom (without any H/Cl/Br/I atom attached to it), i.e., with a few noted exceptions, any chemical with at least a perfluorinated methyl group () or a perfluorinated methylene group () is a PFAS.”2–4 In addition, The Interstate Technology and Regulatory Council (ITRC) also notes that “there is no universally accepted definition of PFAS, however, in general PFAS are characterized as having carbon atoms linked to each other and bonded to fluorine atoms at most or all of the available carbon bonding sites.”5 The definition in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) CompTox Chemicals Dashboard (from here on, the Dashboard), which (as of late 2021) yields over 10,776 PFAS structures,6 includes all substances that contain a specific set of substructural elements.7 The Dashboard defines this set of substructures as “designed to be simple, reproducible and transparent, yet general enough to encompass the largest set of structures having sufficient levels of fluorination to potentially impart PFAS-type properties.” Humans have widespread exposure to PFAS,8 and PFAS have been shown to pose ecological9 and human health hazards.9–11 To date, most toxicity data is available for a small number of legacy PFAS chemicals, such as perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), whereas thousands of other PFAS have limited toxicity data available.

The 2019 U.S. EPA Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Action Plan12 outlines a multiprogram national research plan to address the challenge of PFAS.12 One component of this strategy involves the use of systematic evidence map (SEM) approaches to characterize the evidence base for hundreds of PFAS, especially those that are not the subject of existing or assessments under development by the U.S. EPA (Table 1 includes a list of PFAS that are not included in this SEM). Although there is no one consistent definition of an evidence map,13–18 one description is “A comprehensive summary of the characteristics and availability of evidence as it relates to broad issues of policy or management relevance. Systematic maps do not seek to synthesize evidence but instead to catalogue it, using systematic search and selection strategies to produce searchable databases of studies along with detailed descriptive information.”19 SEMs may include critical evaluation of studies, but there is no synthesis of the evidence to answer an assessment question.

Table 1.

PFAS under assessment by U.S. EPA that are not included in this systematic evidence map.

| PFAS | CASRN | DTSXID | DTSXID citation | U.S. EPA assessment activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA) | 375-22-4 | DTXSID4059916 | U.S. EPA60 | IRIS AssessmentaU.S. EPA61 |

| Ammonium perfluorobutanoate | 10495-86-0 | DTXSID10893420 | U.S. EPA62 | — |

| Perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA) | 307-24-4 | DTXSID3031862 | U.S. EPA63 | IRIS AssessmentaU.S. EPA61 |

| Ammonium perfluorohexanoate | 21615-47-4 | DTXSID90880232 | U.S. EPA64 | — |

| Sodium perfluorohexanoate | 2923-26-4 | DTXSID3052856 | U.S. EPA18 | — |

| Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) | 335-67-1 | DTXSID8031865 | U.S. EPA66 | Development of SDWA National Primary Drinking Water StandardbU.S. EPA67–69 |

| Ammonium perfluorooctanoate | 3825-26-1 | DTXSID8037708 | U.S. EPA70 | — |

| Perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) | 375-95-1 | DTXSID8031863 | U.S. EPA71 | IRIS AssessmentaU.S. EPA61 |

| Ammonium perfluorononanoate | 4149-60-4 | DTXSID20880205 | U.S. EPA72 | — |

| Sodium heptadecafluorononanoate | 21049-39-8 | DTXSID50896632 | U.S. EPA73 | — |

| Perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA) | 335-76-2 | DTXSID3031860 | U.S. EPA74 | IRIS AssessmentaU.S. EPA61 |

| Ammonium perfluorodecanoate | 3108-42-7 | DTXSID60880027 | U.S. EPA75 | — |

| Sodium perfluorodecanoate | 3830-45-3 | DTXSID20880028 | U.S. EPA76 | — |

| Perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS) | 375-73-5 | DTXSID5030030 | U.S. EPA77 | ORD AssessmentU.S. EPA78 |

| Perfluorobutanesulfonate | 45187-15-3 | DTXSID60873015 | U.S. EPA79 | — |

| Ammonium perfluorobutanesulfonate | 68259-10-9 | DTXSID3071355 | U.S. EPA80 | — |

| Potassium perfluorobutanesulfonate | 29420-49-3 | DTXSID3037707 | U.S. EPA81 | — |

| Perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS) | 355-46-4 | DTXSID7040150 | U.S. EPA82 | IRIS AssessmentaU.S. EPA61 |

| Potassium perfluorohexanesulfonate | 3871-99-6 | DTXSID3037709 | U.S. EPA83 | — |

| Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) | 1763-23-1 | DTXSID3031864 | U.S. EPA84 | Development of SDWA National Primary Drinking Water StandardbU.S. EPA67–69 |

| Perfluorooctanesulfonate | 45298-90-6 | DTXSID80108992 | U.S. EPA85 | — |

| Ammonium perfluorooctanesulfonate | 29081-56-9 | DTXSID9067435 | U.S. EPA86 | — |

| Lithium perfluorooctanesulfonate | 29457-72-5 | DTXSID2032421 | U.S. EPA87 | — |

| Potassium perfluorooctanesulfonate | 2795-39-3 | DTXSID8037706 | U.S. EPA88 | — |

| Sodium perfluorooctanesulfonate | 4021-47-0 | DTXSID50635462 | U.S. EPA89 | — |

| Perfluoro-2-methyl-3-oxahexanoic acid (“GenX Chemicals”) | 13252-13-6 | DTXSID70880215 | U.S. EPA90 | OW Assessment91 |

| Ammonium perfluoro-2-methyl-3-oxahexanoate | 62037-80-3 | DTXSID40108559 | U.S. EPA92 | OW Assessment91 |

Note: These PFAS chemicals were deprioritized from the evidence map due to scoping considerations as described in the Methods section. These PFAS chemicals are undergoing more in-depth analyses as part of specific U.S. EPA chemical assessments. Interested readers can access assessments or draft materials at the identified citations. —, chemical included as synonym in overarching assessment; ORD, U.S. EPA Office of Research and Development; OW, U.S. EPA Office of Water.

The URLs provided in the table provide links to the chemical assessment page for PFAS under assessment by the ORD Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) Program. Information on timelines for development of the assessments can be found in the IRIS Program Outlook,93 which is updated three times per year.

In February 2021, the U.S. EPA Office of Water (OW) published the final Regulatory Determination 494 which presented a final positive determination to regulate PFOA and PFOS in drinking water. As part of the process that will result in the promulgation of a National Primary Drinking Water Standard under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), the U.S. EPA initiated a systematic literature review of peer-reviewed scientific literature for PFOA and PFOS published since 2013, with the goal of identifying any new studies that may be relevant to human health assessment. Additional analyses of these new studies are needed to confirm relevance, extract the data to assess the weight of evidence, and identify critical studies to inform future decision-making with respect to SDWA.95

This study employs SEM approaches to compile and summarize the human and experimental animal evidence for a subset of PFAS that are undergoing in vitro high-throughput toxicity (HTT) and toxicokinetic testing. It focuses on PFAS that were selected in 2019 by the U.S. EPA Center for Computational Toxicology and Exposure (CCTE).20 (For complete list of all 171 PFAS, see Excel Table S1, which also includes conjugate salts, acids, etc., that would be environmentally present.) Some results of the CCTE PFAS 150 testing that describe the key PFAS structural features associated with various nuclear receptor activities have been published,21 and there are more publications currently under development. In addition, the SEM includes Nafion (see Excel Table S2; DTXSID90897643, CASRN 31,175-20-9), a PFAS of emerging interest that was not included in the CCTE priority list. By compiling evidence on such a large number of chemicals simultaneously, we hope to demonstrate the utility of SEMs for assessment scoping and hazard identification, to identify areas of uncertainty, and to clarify research needs for this chemical data set.

Methods

The Office of Research and Development (ORD) Staff Handbook for Developing Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) Assessments (referred to as the “IRIS Handbook”)22 outlines the systematic review methods used to conduct the PFAS 150 SEM. The IRIS Handbook has been reviewed by the National Academy of Sciences,23 and these methods have been used in other peer-reviewed systematic reviews.24,25

Populations, Exposures, Comparators, and Outcomes (PECO) Criteria and Supplemental Material Tagging

PECO criteria are used to focus the scope of an evidence map or systematic review by defining the research question(s), search terms, and inclusion/exclusion criteria. The PECO for the PFAS 150 SEM is presented in Table 2. In addition to PECO-relevant studies, studies that did not meet PECO criteria but contained “potentially relevant” supplemental material were tracked during the literature screening process. Supplemental material was tagged by category, as outlined in Table 3. Note that “supplemental material” does not refer to findings contained in the supplement of papers identified.

Table 2.

Populations, exposures, comparators, and outcomes (PECO) criteria.

| PECO element | Description |

|---|---|

| Populations | Human: Any population and life stage (occupational or general population, including children and other potentially sensitive populations).Animal: Nonhuman mammalian animal species (whole organism) of any life stage (including preconception, in utero, lactation, peripubertal, and adult stages). |

| Exposures | Relevant forms: PFAS represented by PFAS structures and substances identified in the Excel File (Excel Tables S1 and S2).Human: Any exposure to PFAS via the oral and inhalation routes because these are the most relevant routes of human exposure and typically the most useful for developing human health toxicity values. Studies are also included if biomarkers of PFAS exposure are evaluated (e.g., measured PFAS or metabolite in tissues or bodily fluids) but the exposure route is unclear or reflects multiple routes. Other exposure routes, including dermal, and mixture-only studies (i.e., without effect estimates for individual PFAS of interest) are tracked during title and abstract screening and are tagged as “potentially relevant” supplemental material.Animal: Any exposure to PFAS via oral or inhalation routes. Studies involving exposures to mixtures are included only if a treatment group consists of exposure to a PFAS alone. Other exposure routes, including dermal or injection, and mixture-only studies are tagged as “potentially relevant” supplemental material. |

| Comparators | Human: A comparison or referent population exposed to lower levels (or no exposure/exposure below detection limits) or exposed for shorter periods of time. However, worker surveillance studies are considered to meet PECO criteria even if no referent group is presented. Case reports describing findings in 1–3 people in nonoccupational or occupational settings are tracked as “potentially relevant” supplemental material.Animal: A concurrent control group exposed to vehicle-only treatment and/or untreated control (control could be a baseline measurement). |

| Outcomes | All health outcomes (cancer and noncancer). |

Table 3.

Major categories of “potentially relevant” supplemental material.

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| In vitro, ex vivo, or in silico “mechanistic” studies | In vitro, ex vivo, or in silico studies reporting measurements related to a health outcome that inform the biological or chemical events associated with phenotypic effects, in both mammalian and nonmammalian model systems. |

| Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) |

ADME studies are primarily controlled experiments where defined exposures usually occur by intravenous, oral, inhalation, or dermal routes, and the concentration of particles, a chemical, or its metabolites in blood or serum, other body tissues, or excreta are then measured. These data are used to estimate the amount absorbed (A), distributed to different organs (D), metabolized (M), and/or excreted/eliminated (E) through urine, breath, feces, etc.

|

| Classical Pharmacokinetic (PK) Model Studies, or Physiologically based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Model studies | Classical Pharmacokinetic (PK) or Dosimetry Model Studies: Classical PK or dosimetry modeling usually divides the body into just one or two compartments, which are not specified by physiology, where movement of a chemical into, between, and out of the compartments is quantified empirically by fitting model parameters to ADME data. Physiologically based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) or Mechanistic Dosimetry Model Studies: PBPK models represent the body as various compartments (e.g., liver, lung, slowly perfused tissue, richly perfused tissue) to quantify the movement of chemicals or particles into and out of the body (compartments) by defined routes of exposure, metabolism, and elimination, and thereby estimate concentrations in blood or target tissues. |

| Nonmammalian model systems | Studies in nonmammalian model systems, e.g., Xenopus, fish, birds, C. elegans. |

| Transgenic mammalian model systems | Transgenic studies in mammalian model systems. |

| Non-oral or noninhalation routes of administration | Studies in which humans or animals (whole organism) were exposed via a non-oral or noninhalation route (e.g., injection, dermal exposure). |

| Exposure characteristics (no health outcome assessment) | Exposure characteristic studies which include data that are unrelated to health outcomes but which provide information on exposure sources or measurement properties of the environmental agent (e.g., demonstrate a biomarker of exposure). |

| Mixture studies | Mixture studies that are not considered PECO-relevant because they do not contain an exposure or treatment group assessing only the chemical of interest. This category is generally used for experimental studies and generally does not apply to epidemiological studies where the exposure source may be unclear. |

| Case reports | Case reports describing health outcomes after exposure will be tracked as potentially relevant supplemental information when the number of subjects is three or fewer. |

| Records with no original data | Records that do not contain original data, such as other agency assessments, informative scientific literature reviews, editorials, or commentaries. |

| Conference abstracts | Records that do not contain sufficient documentation to support study evaluation and data extraction. |

| European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) read-across | Data on a non-relevant chemical that makes inferences about a relevant PFAS chemical. |

| Presumed duplicate | Duplicate studies (e.g., published vs. unpublished reports) identified during data extraction and study quality evaluation. |

Note: “Potentially relevant” supplemental material are studies that do not meet the PECO criteria but may still contain information of interest that was tracked during screening. Additionally, the definitions in the table follow standard template language that is used in systematic evidence maps developed by the U.S. EPA22,51 and have only been adjusted, where appropriate, for the specific needs of this SEM. PECO, populations, exposures, comparators, and outcomes; PFAS, PFAS per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

Literature Search and Screening Strategies

Database search term development.

Chemical search terms were used to search for relevant literature in the databases listed below. The detailed search strategy for each database, including specific search strings, are presented in Excel Tables S3 through S8.

PubMed (National Library of Medicine)

Web of Science (Thomson Reuters)

ToxLine via the ToxNet (included in the 2019 search; no longer operational in the 2020 or 2021 search updates)

The literature search for the PFAS (except Nafion, described below) consisted only of the chemical name, synonyms, and trade names and no additional limits, with exception of the Web of Science (WoS) search strategy. Due to the specifics of searching WoS, a chemical name-based search can retrieve a very large number of off-topic references. Given the number of PFAS included in this screening effort, a more targeted WoS search strategy was used to identify the records most likely applicable to human health (see Excel Tables S4, S6, and S8). Chemical synonyms for PFAS were identified by using synonyms in the Dashboard26 indicated as “valid” or “good.” The preferred chemical name (as presented in the Dashboard), Chemical Abstract Services Registry Number (CASRN), and synonyms were then shared with U.S. EPA information specialists, who used these inputs to develop search strategies tailored for PubMed, Web of Science, and ToxLine (see Excel Tables S4, S6, and S8).

An SEM for Nafion was created before the expanded SEM on the PFAS was initiated and used a different process for identifying synonyms in the search terms. Synonyms were identified by using the “Find Chemical Synonyms” tool in SWIFT-Review (version 1.42; Sciome LLC).27 In brief, this feature automatically creates a PubMed-formatted chemical search using a) the common name for the chemical as presented in the Tox21 chemical inventory list; b) the CASRN; and c) synonyms from the ChemIDPlus database, with removal of ambiguous or short alphanumeric terms that could lead to false positives. This search was manually reviewed to ensure that any synonyms listed in the Dashboard as “valid” or “good” were included (see Excel Table S2). The PubMed search created from SWIFT-Review was then modified as needed by U.S. EPA information specialists for usage on other databases (see Excel Tables S3, S5, and S7).

Database searches.

The database searches were conducted by a U.S. EPA information specialist in June 2019 for Nafion and in August 2019 for the PFAS 150, and searches were updated in December 2020 and again in December 2021. For the December 2020 and December 2021 searches, the following PFAS were inadvertently excluded: 1-bromoheptafluoropropane (CASRN 422-85-5; DTXSID3059971), 11:1 fluorotelomer alcohol (CASRN 423-65-4; DTXSID80375107), 6H-perfluorohex-1-ene (CASRN 1767-94-8; DTXSID10379850), perfluoroheptanoic acid (CASRN 375-85-9; DTXSID1037303), perfluorooctanesulfonamid (CASRN 76752-79-9; DTXSID001016256), and perfluoroundecanoic acid (CASRN 2058-94-8; DTXSID8047553). Consequently, the literature results reported for these PFAS are only current through 2019. In Excel Table S6, these PFAS appear as ‘not searched’ under the ‘Database’ column and in Excel Table S8, these PFAS are excluded entirely. Other ‘not searched’ cells in the ‘Database’ column for Excel Table S6 are for PFAS that were deprioritized after the 2019 search as is described later in this section.

All records were stored in the U.S. EPA’s Health and Environmental Research Online (HERO) database.28,29 The HERO database30 is used to provide access to the references used in the U.S. EPA’s scientific assessments, including this effort. After deduplication in HERO using unique identifiers (e.g., PMID, WoSID, or DOI) and citations, the references went through an additional round of deduplication using ICF’s DeDuper tool (described in detail in Supplemental Material, “DeDuper”), which uses a two-phase approach to identify duplicates by a) locating duplicates using automated logic and b) employing machine learning built from Python’s Dedupe package to predict likely duplicates, which are then verified manually.31 Following deduplication, SWIFT-Review software27 was used to identify which of the unique references were most relevant for human health risk assessment. In brief, SWIFT-Review was used to filter the unique references based on the software’s preset literature search strategies (titled “evidence stream”). These evidence streams were developed by information specialists and can be used to separate the references most relevant to human health from those that are not (e.g., environmental fate studies). References are tagged to a specific evidence stream if the search terms from that evidence stream appear in the title, abstract, keyword, and/or medical subject headings (MeSH) fields of that reference. For this SEM, the following SWIFT-Review evidence streams were applied: human, animal models for human health, and in vitro studies. Specific details on the evidence stream search strategies are available through Sciome’s SWIFT-Review documentation.32 Studies not retrieved using the search strategies were not considered further.

Several PFAS were deprioritized from the evidence map due to scoping considerations as outlined below. Some PFAS under assessment by the U.S. EPA IRIS Program and the Office of Water (OW) (Table 1) were included in the initial literature search but later deprioritized for screening because they are undergoing more in-depth analyses as part of specific U.S. EPA chemical assessments. To remove these records from further screening, the search results for the combined chemical list were imported into SWIFT-Review27 and analyzed using filters that were developed for the PFAS 150 SEM. To develop these filters in SWIFT-Review, the search strategies developed by HERO information specialists were analyzed using the SWIFT-Review integrated Chemical Synonyms tool to generate additional keywords, including MeSH and supplementary concept terms, for each chemical in the PFAS 150 list. The search filters explore words included in the title, abstract, keyword, or MeSH fields.

In addition, the PFAS compounds sevoflurane, perfluorooctane, and flurothyl were de-prioritized. These chemicals are pharmaceuticals or have uses associated with medical applications and were included in the initial CCTE list to maximize coverage of chemical space (for structural diversity, etc.) covered in the experimental testing work.20 However, some of these compounds failed analytical quality control (QC) for the planned experimental work or were unavailable as pure substances from a commercial supplier and were therefore not included in the final set of chemicals tested by CCTE. Furthermore, sevoflurane, perfluorooctane, and flurothyl accounted for approximately half of the 20,473 articles. Because they significantly increased the screening level of effort and were ultimately not included in the list of chemicals tested by CCTE, they were deprioritized for inclusion in the SEM.

Other resources consulted.

The literature search strategies described above are intentionally broad; however, it is still possible that some studies were not captured (e.g., cases where the specific chemical is not mentioned in title, abstract, or keyword content; “gray” literature that is not indexed in the databases listed above). Additionally, if incomplete citation information was provided (e.g., if reference lists searched did not include titles), no additional searching was conducted. Thus, in addition to the databases identified above, the sources below were used to identify studies that may not have been captured in the database searches. Table 4 describes the other resources consulted.

Reference list from the Health Effects Chapter of the draft Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) Toxicological Profiles for three PFAS included in the PFAS 150 SEM: perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA), perfluoroundecanoic acid (PFUA), and perfluorooctane sulfonamide (PFOSA).33

Reference list from the PFAS-Tox Database, a 2019 evidence map of 29 PFAS.34,35

Reference lists from all PECO-relevant animal and epidemiological studies identified in the database searches meeting PECO criteria. (see Excel Table S9)

National Toxicology Program (NTP) database of study results and research projects. This was accomplished by personal communication with NTP rather than manual search of the NTP database for all the PFAS included in the evidence map.

- References from the U.S. EPA’s CompTox Chemicals Dashboard ToxValDB (Toxicity Values Database) to identify studies or assessments that present point of departure (POD) information.26 ToxValDB collates publicly available toxicity dose–effect related summary values typically used in risk assessments. Many of the PODs presented in ToxValDB are based on gray literature studies or assessments not available in databases such as PubMed, WoS, etc. It is important to note that ToxValDB entries have not undergone quality control to ensure accuracy or completeness and may not include recent studies.

- ToxValDB include POD data collected from data sources within ACToR (Aggregated Computational Toxicology Resource) and ToxRefDB (Toxicity Reference Database) and no-observed and lowest-observed (adverse) effect level (NOEL, NOAEL, LOEL, LOAEL) data extracted from repeated dose toxicity studies submitted under Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH). Also included are reference dose and concentration values (RfDs and RfCs) from the U.S. EPA IRIS Program and dose descriptors from the U.S. EPA’s Provisional Peer-Reviewed Toxicity Values (PPRTV) documents. Acute toxicity information in ToxValDB comes from a number of different sources, including Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) eChemPortal, National Library of Medicine (NLM), Hazardous Substances Data Bank (HDSB), ChemIDplus via the U.S. EPA Toxicity Estimation Software Tool (TEST), the European Union’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) AcutoxBase the European Union’s COSMOS project, and the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) registration dossiers to identify data submitted by registrants.36

Table 4.

Summary of other sources consulted and number of references identified.

| Source name | Source citation | Search terms | Search date | Total unique number of results retrieved | Records not otherwise identified that were screened in DistillerSR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Review of reference lists studies considered relevant to PECO based on full-text screening. | NA | NA | NA | 790 | 276 |

| U.S. EPA CompTox (Computational Toxicology Program) Chemicals Dashboard (ToxVal) | U.S. EPA26 | Provided by CCTE | Provided by CCTE | 16 | 15 |

| European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) | ECHA36 | [CASRN] | 11/27/2019-12/18/2019 | 539 | 486 |

| 2019, 2020 PFAS-Tox Database | PFASToxDatabas35 | NA | NA | 795 | 384 |

| National Toxicology Program (NTP) Chemical Effects in Biological Systems (CEBS) | (John Bucher, National Toxicology Program, personal communication) | [CASRN] | 3/18/2020 | 3 | 2 |

Note: NA, not applicable.

Results from searching other resources.

Records from these other sources were uploaded into DistillerSR (version 2.29.0; Evidence Partners Inc.)37 and annotated with respect to source of the record. The specific methods and results for searching each source are described below. Searching of these sources is summarized to include the source type or name, the search string (when applicable), the number of results present within the resource, and the URL (when available and applicable).

ECHA.

A search of the ECHA registered substances database was conducted using the CASRN. The registration dossier associated with the CASRN was retrieved by navigating to and clicking the eye-shaped view icon displayed in the chemical summary panel. The General Information tab and all subpages under the Toxicological Information tab were downloaded in PDF format, including all nested reports that had unique URLs. In addition, the data was extracted from each dossier page and used to populate an Excel tracking sheet with this data. Extracted fields included data from the general information page regarding the registration type and publication dates, and on a typical ECHA dossier page the primary fields reported in the administrative data, data source, and effect levels sections. Each study summary resulted in more than one row in the tracking sheet if more than one data source or effect level was reported.

At this stage, each reference was reviewed for inclusion based on PECO criteria. ECHA dossiers without information under the ToxCategory column were excluded from review because these refer to data extracted from the General Information tab. Toxicological and end point summary pages, study protocols, and dossiers with data waiving were also excluded from review. When a reference that was considered relevant reported data from a named study or lab report, a citation for the full study was either retrieved or generated in HERO and verified that it was not already identified from the peer-reviewed literature search prior to moving forward to screening in DistillerSR. If citation information was not available and a full text could not be retrieved, ECHA and ToxValDB references were compared using information on the chemical, points of departure, study type, species, strain, sex, exposure route and method, and critical effect to determine whether any of these references were previously accounted for in ToxValDB. When there were no overlaps between references, a citation was created in HERO using the information provided in the ECHA dossier. The generated PDF for the dossier was used as the full text for screening, and these citations were annotated accordingly for Tableau and HAWC visualizations by adding “(ECHA)” to the citation.

U.S. EPA CompTox chemical dashboard (ToxValDB).

ToxValDB data was retrieved for the PFAS chemicals from the U.S. EPA CompTox Dashboard.38 Data available from the Hazard tab for each chemical was exported from the Dashboard by U.S. EPA staff and provided as an Excel file output. Using this ToxValDB POD summary file, citations were identified for references that apply to human health PODs. A citation for each reference, except those indicated as “ECHA” or “ECHA IUCLID,” was either retrieved or generated in HERO and verified that it was not already identified from the database search prior to moving forward to screening in DistillerSR.

References in ToxValDB described as from an ECHA or ECHA IUCLID source were confirmed to be accounted for in the ECHA results retrieved above. A comparison was performed between 25% of the ECHA references from ToxValDB and the full ECHA results retrieved above, and although the comparison noted discrepancies (5 out of 34), these were found to be inaccuracies in ToxValDB, most likely because the data was removed or modified during an update to ECHA since the last time ToxValDB imported ECHA data. That is, the ECHA dossiers retrieved above were determined to be more accurate and up to date than the ToxValDB ECHA entries and could supersede the ECHA data from ToxValDB.

Screening and tagging process.

After selection of evidence streams and chemicals in SWIFT-Review as described in the “Database Searches” section, the filtered studies were imported into SWIFT-Active Screener (version 1.061; Sciome LLC) for title or abstract (TIAB) screening. SWIFT-Active Screener is a web-based collaborative software application that uses active machine-learning approaches to reduce the screening effort.39 The screening process was designed to prioritize records that appeared to meet PECO criteria or that included supplemental material content based on TIAB content (i.e., both types of records were screened as “include” for active-learning purposes). Studies were screened in SWIFT-Active Screener until the software indicated a likelihood of 95% that all relevant studies had been captured. This threshold is comparable to human error rates27,40,41 and is used as a metric to evaluate machine-learning performance. Any studies in “partially screened” status at the time of reaching the 95% threshold were fully screened.

Studies that met these criteria from TIAB screening were then imported into DistillerSR for more specific TIAB tagging (i.e., to separate studies meeting PECO criteria vs. supplemental content and to tag the specific category of supplemental content and, if necessary, the chemical). Supplemental content tags are described in Table 3. For studies meeting PECO criteria at the DistillerSR TIAB level, full text articles were retrieved through the U.S. EPA HERO database. References that were not able to be retrieved within 45 d were identified to be unavailable.

Studies identified via the gray literature searches were imported directly into DistillerSR at the TIAB phase. References identified in the gray searches that had previously been screened as not relevant to PECO at either the SWIFT-Review or SWIFT-Active Screener stage were rescreened in Distiller.

Two independent reviewers conducted each level of screening (TIAB and full text). At all levels (SWIFT-Active Screener TIAB, DistillerSR TIAB, and DistillerSR full-text review), any conflicts in screening were resolved by discussion between the two independent reviewers; a third reviewer was consulted if any conflicts remained thereafter. Conflicts between screeners in applying the supplemental tags were resolved by discussion at both the TIAB and full-text levels, erring on the side of overtagging at the TIAB level. At the TIAB level, articles without an abstract were screened based on title (title should indicate clear relevance), and number of pages (articles two pages or fewer in length were assumed to be records with no original data) For additional information, please see Table 3 for supplemental categorization information. All studies identified as supplemental material at TIAB and full-text levels were tagged to their respective chemical(s) using the preferred chemical names. All studies identified as PECO were tagged to the preferred chemical name after the full-text screening stage. A caveat to tagging at the TIAB level was that tagging was based only on information provided in the abstract and could therefore miss additional details that may have been provided in the full text of the manuscript. Additionally, sources that did not list a specific PFAS in the TIAB (i.e., included terms like “PFAS”) were tagged to “chemical not specified.” However, if any PFAS were specified, they were tagged and the “chemical not specified” tag was not selected, even though it was possible that additional PFAS chemicals were reported in the full text. All chemical tagging was reviewed by an expert in chemistry (with a doctoral or similar degree). Where chemical identity presented in the manuscript was unclear, the original authors were contacted to resolve the chemical species.

Data Extraction of Study Methods and Findings

Animal toxicology studies.

Studies that met PECO criteria after full-text review were summarized using custom forms (Supplemental Material, “Distiller Literature Inventory SOP for PFAS 150 (abbreviated)”] in DistillerSR. For animal studies, the following study summary information was captured in a literature inventory: PFAS assessed, study type [acute (), short term (1–30 d), subchronic (30–90 d), chronic (), developmental, peripubertal, multigenerational], route of exposure, species, sex, and health system(s) assessed (described in Table S1). For epidemiology studies, the following study summary information was captured in a literature inventory: PFAS assessed, sex, population, study design (Table S2), exposure measurement (e.g., blood, feces), and health system(s) assessed. Summaries were then extracted into DistillerSR by one team member, and the extracted data were checked for quality by at least one other team member. The data from these summary literature inventories were exported from DistillerSR to an Excel format and were then modified and transformed using Excel’s “Get and Transform” features for import into Tableau visualization software (https://www.tableau.com/) (version 2019.4; Tableau Software LLC). These data transformations included pivoting multiple columns of data to single columns, appending data from multiple literature inventories (i.e., Nafion and PFAS 150), and merging detailed reference information and chemical ID information into the data set.

The survey of available evidence presented in the Tableau heat maps is also available for download as an Excel file.42

The literature inventory was used to prioritize animal toxicology studies with exposure to the PFAS 150 chemicals for repeat dose studies of 21-d and longer durations, or with study designs focusing on exposure windows targeting reproduction or development. Studies meeting these exposure timing and duration parameters were moved forward for study evaluation (described in next section) and end point–level data extraction. Animal toxicology studies not meeting these criteria did not move forward and were summarized at the literature inventory level only.

Data extraction was conducted for prioritized animal toxicology studies by two members of the evaluation team using the U.S. EPA’s version of the Health Assessment Workspace Collaborative (HAWC),43 a free and open-source web-based software application that facilitates the management of literature assessments for environmental pollutants. Data extracted included basic study information (e.g., full citation, funding, author-reported conflicts of interest); experiment details (e.g., study type, chemical name, chemical source, and purity); animal group specifics (species, strain, sex, age at exposure and assessment, husbandry); dosing regimen; end points evaluated; and results (qualitative or quantitative) by end point. Authors were not contacted for information that was not reported in a study. Data extraction was performed by one member of the evaluation team (primary extractor) and checked by a second member for completeness and accuracy (secondary extractor). Data extraction results were used to create HAWC visualizations (e.g., exposure–response arrays) by health system and effect for each of the PFAS chemicals. Although outside the scope of this SEM, once in HAWC, the extracted data can be used for evidence synthesis and benchmark dose (BMD) modeling on an end point-by-end point basis at the discretion of the user. The detailed HAWC extractions for animal studies are available for download from the U.S. EPA HAWC in Excel format44 and are presented in Excel Table S10. The data extraction output will also be available as an Excel file from the Dashboard ToxValDB database in a future release.

Subsequent to HAWC data extraction, U.S. EPA toxicologists (M.A., X.A., A.D., L.D., I.D., A.K., P.K., L.L., P.N., and M.T.) reviewed each study to identify study and system level (e.g., hepatic, urinary, etc.) NOAELs and LOAELs. These judgments were made at the individual study level. Study and end point–level NOAELs and LOAELs are available in the HAWC project45 (and are summarized in Excel Table S11). This review was conducted to ensure consistent annotation of the animal toxicology studies in CCTE analyses that will compare in vitro to in vivo potencies and effects. While in most cases determinations of NOAELs and LOAELs were consistent with statistically significant findings as reported by authors, judgments were based on the biological significance and evaluation in the context of other, related findings. For example, findings of noncancer hepatic adversity findings were evaluated based on recommendations presented in Hall et al.46 These determinations were made by toxicologists who are serving as chemical managers for the IRIS PFAS assessments listed in Table 1, each of whom has multiple years of experience in developing chemical human health assessments. Judgments were made independently by two toxicologists, with additional discussions to resolve conflicts (if any).

Epidemiology studies.

Epidemiology studies did not undergo study evaluation or full end point–level data extraction because they will not be used in the planned HTT testing.20 However, a more detailed analysis of these studies is being pursued as part of a separate publication activity.

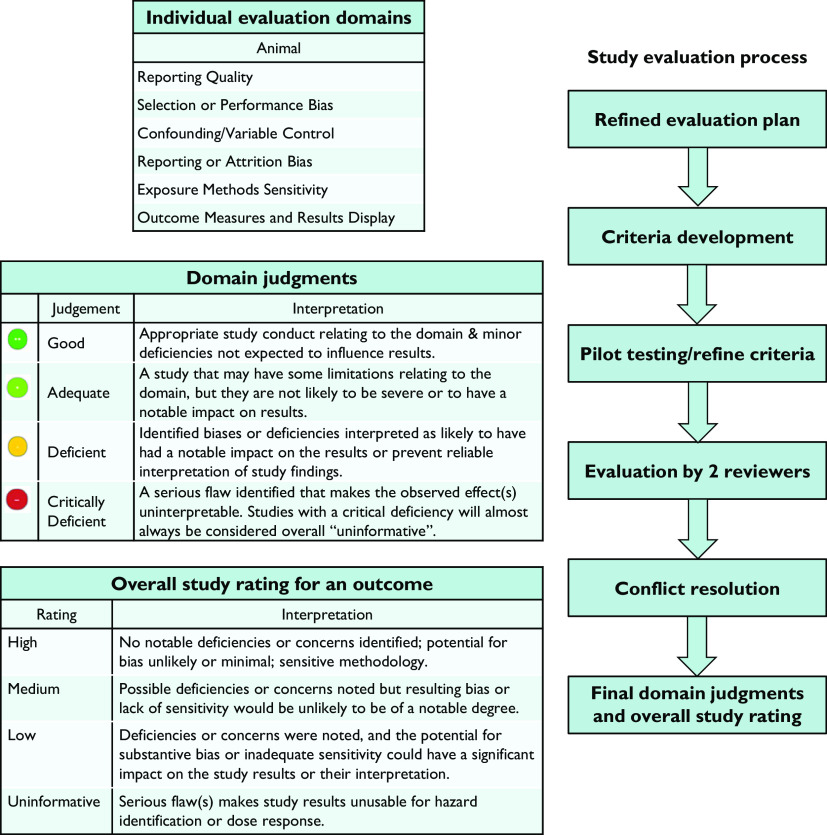

Study Evaluation

Study evaluation was conducted for prioritized animal toxicology studies ( exposure durations or exposure occurring during reproduction or development) by two reviewers using the U.S. EPA’s version of HAWC.43 Reviews were made by toxicologists with multiple years of experience in developing chemical human health assessments. For each study evaluation domain, at least two reviewers reached a consensus rating of Good, Adequate, Deficient, Not Reported or Critically Deficient, as defined in HAWC. The overall study evaluation approach is presented graphically in Figure 1. Key study evaluation considerations included potential sources of bias (factors affecting the magnitude or direction of an effect in a systematic way) and insensitivity (factors limiting detection of a true effect). Core and prompting questions used to guide the judgment for each domain are described in more detail in the IRIS Handbook22 and have been described in several other published publications, including Yost et al.,24,47 Radke et al.,25,49 and Dishaw et al.48 After a consensus rating was reached, the reviewers considered the identified strengths and limitations to reach an overall study confidence rating of High, Medium, Low, or Uninformative for each health outcome (Figure 1). The ratings, which reflect a consensus judgment between reviewers, are defined in the IRIS Handbook.22 The definitions below follow the standard template language that is used in systematic evidence maps developed by the U.S. EPA50 and have only been adjusted, where appropriate, for the specific needs of this SEM.

Figure 1.

Study evaluation approach for experimental animal studies. Note: The approach follows standard methods that are used in systematic evidence maps developed by the U.S. EPA22,50 and have only been adjusted, where appropriate, for the specific needs of this SEM. Note: SEM, systematic evidence map.

High: A well-conducted study with no notable deficiencies or concerns identified for the outcome(s) of interest; the potential for bias is unlikely or minimal, and the study used sensitive methodology. “High” confidence studies generally reflect judgments of good across all or most evaluation domains.

Medium: A study where some deficiencies or concerns were noted for the outcome(s) of interest, but the limitations are unlikely to be of a notable degree. Generally, “medium” confidence studies will include adequate or good judgments across most domains, with the impact of any identified limitation not being judged as severe.

Low: A study where one or more deficiencies or concerns were noted for the outcome(s) of interest, and the potential for bias or inadequate sensitivity could have a significant impact on the study results or their interpretation. Typically, “low” confidence studies would have a deficient evaluation for one or more domains, although some “medium” confidence studies may have a deficient rating in domain(s) considered to have less influence on the magnitude or direction of the results. Generally, in an assessment context (or a full systematic review), low confidence results are given less weight in comparison with high or medium confidence results during evidence synthesis and integration and are generally not used as the primary sources of information for hazard identification or derivation of toxicity values unless they are the only studies available. Studies rated as low confidence only because of sensitivity concerns about biases toward the null would require additional consideration during evidence synthesis.

Uninformative: A study where serious flaw(s) make the results unusable for informing hazard identification for the outcome(s) of interest. Studies with critically deficient judgments in any evaluation domain will almost always be classified as “uninformative” (see explanation above). Studies with multiple deficient judgments across domains may also be considered uninformative. As mentioned above, although outside the scope of this SEM, in an assessment or full systematic review, uninformative studies would not be considered during the synthesis and integration of evidence for hazard identification or for dose response but might be used to highlight possible research gaps. Thus, data from studies deemed uninformative are not depicted in the results displays included in this SEM.

Rationales for each study evaluation classification, including a description of how domain ratings impacted the overall study confidence rating, are available in Excel Table S12 and are documented and retrievable in HAWC.45

Results

Please note that the study counts and figures presented in this manuscript represent a snapshot in time of a repository that may evolve as this project is updated or revisions are made. For the most current information, please visit the web-based inventory and project pages in HAWC and HERO.28,29

Literature Screening Results

As described in the methods section, an SEM for Nafion was developed prior to the SEM for the remaining 150 PFAS chemicals. We will begin by discussing the literature screening results for Nafion.

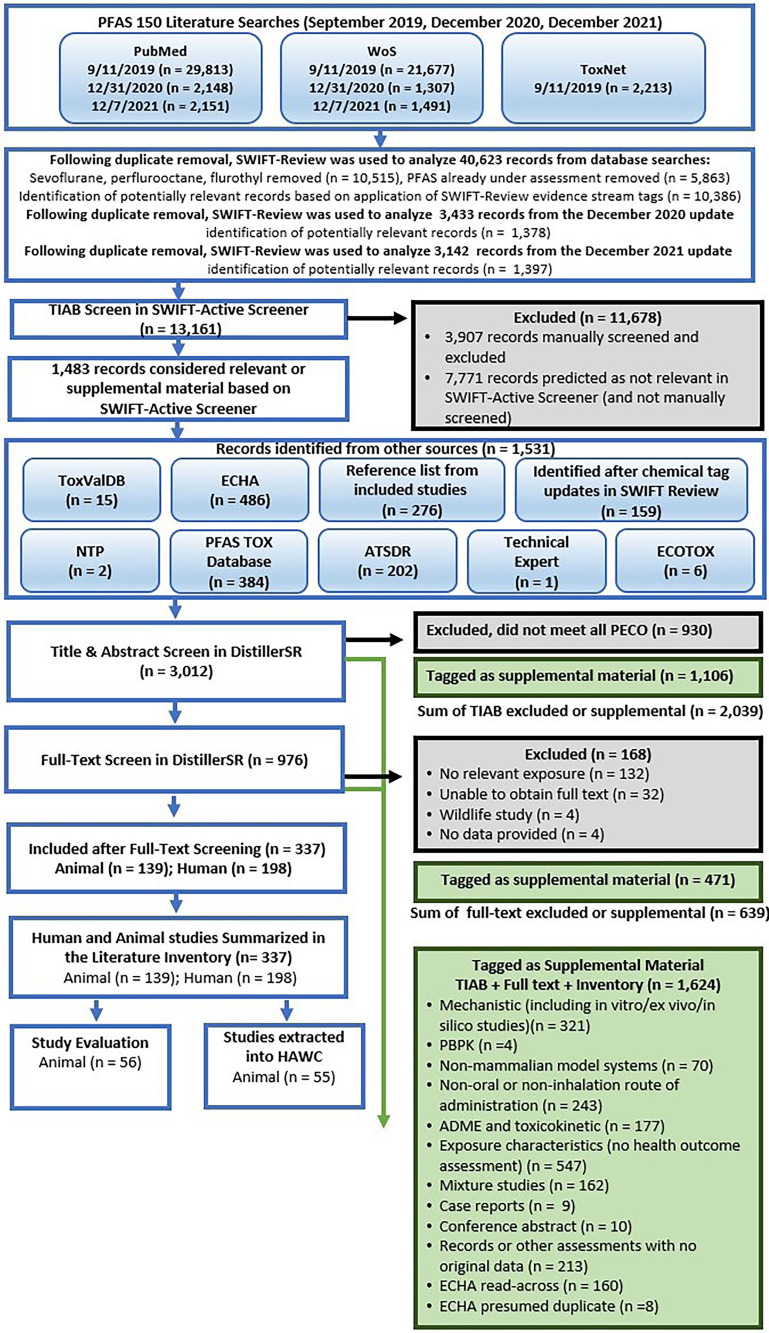

Nafion [CASRN 31175-20-9].

The database searches for Nafion yielded 4,388 records after duplicate removal in HERO (Figure 2). After application of SWIFT-Review evidence stream filters, the total number of studies for consideration was reduced to 1,918. A literature search update conducted in December 2020 yielded 88 unique records after duplicate removal. The references were added directly to DistillerSR TIAB screening. A literature search update conducted in December 2021 yielded 545 additional records after duplicate removal. After application of SWIFT-Review evidence stream filters, the total number of studies for consideration was reduced to 247. During TIAB screening, 5 were included for full-text review, 15 were tagged as supplemental material, and 2,248 were excluded as not relevant to PECO. During full-text review, three studies were excluded as not relevant to PECO. No records were identified from other sources or from a review of the reference lists for the two included studies. Thus, only two studies (one human and one animal) were considered relevant and included in the literature inventory. The single animal study included was extracted into HAWC and underwent study evaluation.

Figure 2.

Nafion study flow diagram (May 17, 2022). Note: ADME, absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion; CASRN, Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number; ECOTOX, U.S. EPA Ecotoxicology Knowledgebase; OECD SIDS HPV, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development Screening Information Dataset for High Production Volume Chemicals; PECO, Populations, Exposure, Comparator, Outcome criteria; ToxValDB, U.S. EPA CompTox Chemicals Dashboard; WoS, Web of Science.

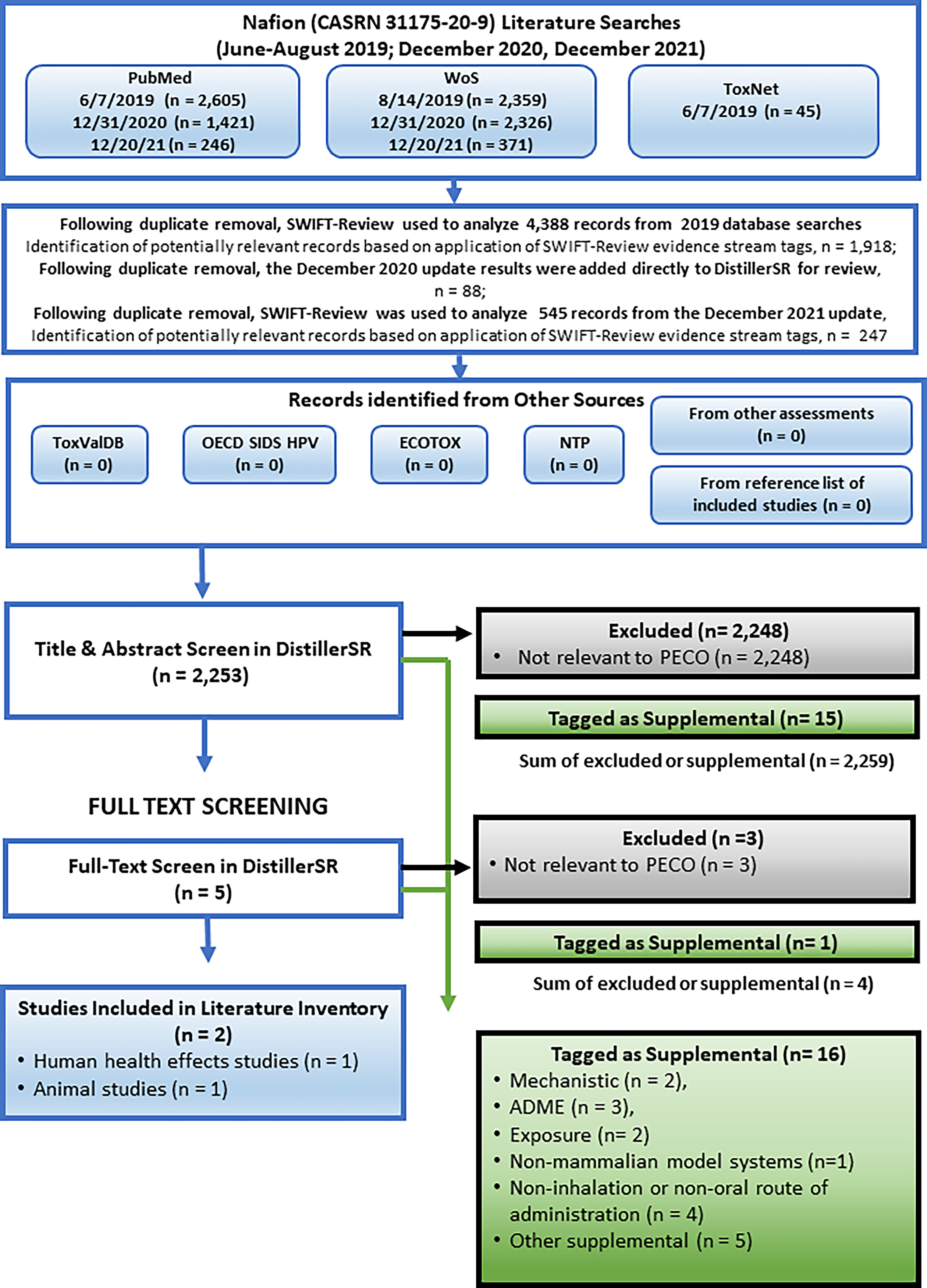

PFAS 150.

The 2019 database searches yielded 40,623 records in HERO after duplicate removal (Figure 3). After application of the SWIFT-Review evidence stream filters for human, animal, and in vitro evidence, the total number of studies for consideration was reduced to 22,121. Additionally, the PFAS filters in SWIFT-Review were used to exclude citations that matched only to PFAS chemicals from the deprioritized list (Table 1), reducing the number of records from 22,121 to 20,473 studies. Sevoflurane, perfluorooctane, and flurothyl accounted for approximately half of the 20,473 articles. After the removal of sevoflurane, perfluorooctane, and flurothyl (as described in the literature search and screen section), 10,386 studies were left for TIAB screening and were imported in SWIFT-Active Screener39 (Figure 3). A literature search update conducted in December 2020 yielded 3,433 records in HERO after duplicate removal. Application of the SWIFT-Review literature search filters for human, animal, and in vitro evidence, removal of sevoflurane, perfluorooctane, and flurothyl, and deprioritized chemicals reduced the number of studies for consideration to 1,378. A literature search update conducted in December 2021 yielded 3,142 records in HERO after duplicate removal. Application of the SWIFT-Review literature search filters for human, animal, and in vitro evidence, removal of sevoflurane, perfluorooctane, and flurothyl, and deprioritized chemicals reduced the number of studies for consideration to 1,397. Across the three literature searches (the original search and two updates) a total of 13,161 studies were identified for screening in SWIFT-Active Screener.

Figure 3.

PFAS-150 Study flow diagram (May 17, 2022). Note: References identified from other sources joined screening at DistillerSR TIAB review. Some references may have multiple supplemental or exclusion tags. For the December 2020 and December 2021 searches, the following PFAS were inadvertently excluded: 1-bromoheptafluoropropane (CASRN 422-85-5; DTXSID3059971), 11:1 fluorotelomer alcohol (CASRN 423-65-4; DTXSID80375107), 6H-perfluorohex-1-ene (CASRN 1767-94-8; DTXSID10379850), perfluoroheptanoic acid (CASRN 375-85-9; DTXSID1037303), perfluorooctanesulfonamid (CASRN 76752-79-9; DTXSID001016256), and perfluoroundecanoic acid (CASRN 2058-94-8; DTXSID8047553). Consequently, the literature results reported for these PFAS are only current through 2019. ADME, absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion; ATSDR, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry; ECHA, European Chemicals Agency; ECOTOX, U.S. EPA Ecotoxicology Knowledgebase; HAWC, Health Assessment Workspace Collaborative; NTP, National Toxicology Program Chemical Effects in Biological Systems; PFAS, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances; PBPK, physiologically based pharmacokinetic; PECO, Populations, Exposure, Comparator, Outcome criteria; PFAS Tox Database, 2019 PFAS evidence map34,35; TIAB, title or abstract screening; ToxValDB, U.S. EPA CompTox Chemicals Dashboard; WoS, Web of Science.

The studies were screened in SWIFT-Active Screener using predictive relevance, resulting in 5,390 studies being manually screened to identify 1,483 studies that were considered potentially PECO-relevant or supplemental (“included” for the purposes of machine learning) and 3,907 records that were excluded. After manually reviewing the 5,390 records, screening was stopped because SWIFT-Active Screener indicated that it was likely that 96% of the relevant studies were identified. SWIFT-Active Screener typically uses an inclusion rate of 95% and has been documented in Howard et al.39 This represented a significant reduction in screening effort (i.e., screening was stopped after of the records were reviewed, and 7,771 records were not manually screened).

An additional 1,372 unique studies were identified from the gray literature sources searched, including 276 that came from reviewing the reference lists of studies considered PECO-relevant after full-text review. During the course of the review, the SWIFT-Review search filters were updated resulting in an additional 159 studies that were prioritized from Swift-Review. These 1,531 studies (1,372 from gray literature and 159 from the Swift-Review search filter update) were imported into DistillerSR for a total of 3,012 studies screened at TIAB level. During TIAB screening in DistillerSR, 976 were included for full-text review, 1,106 were tagged as supplemental material, and 930 were excluded as not relevant to PECO.

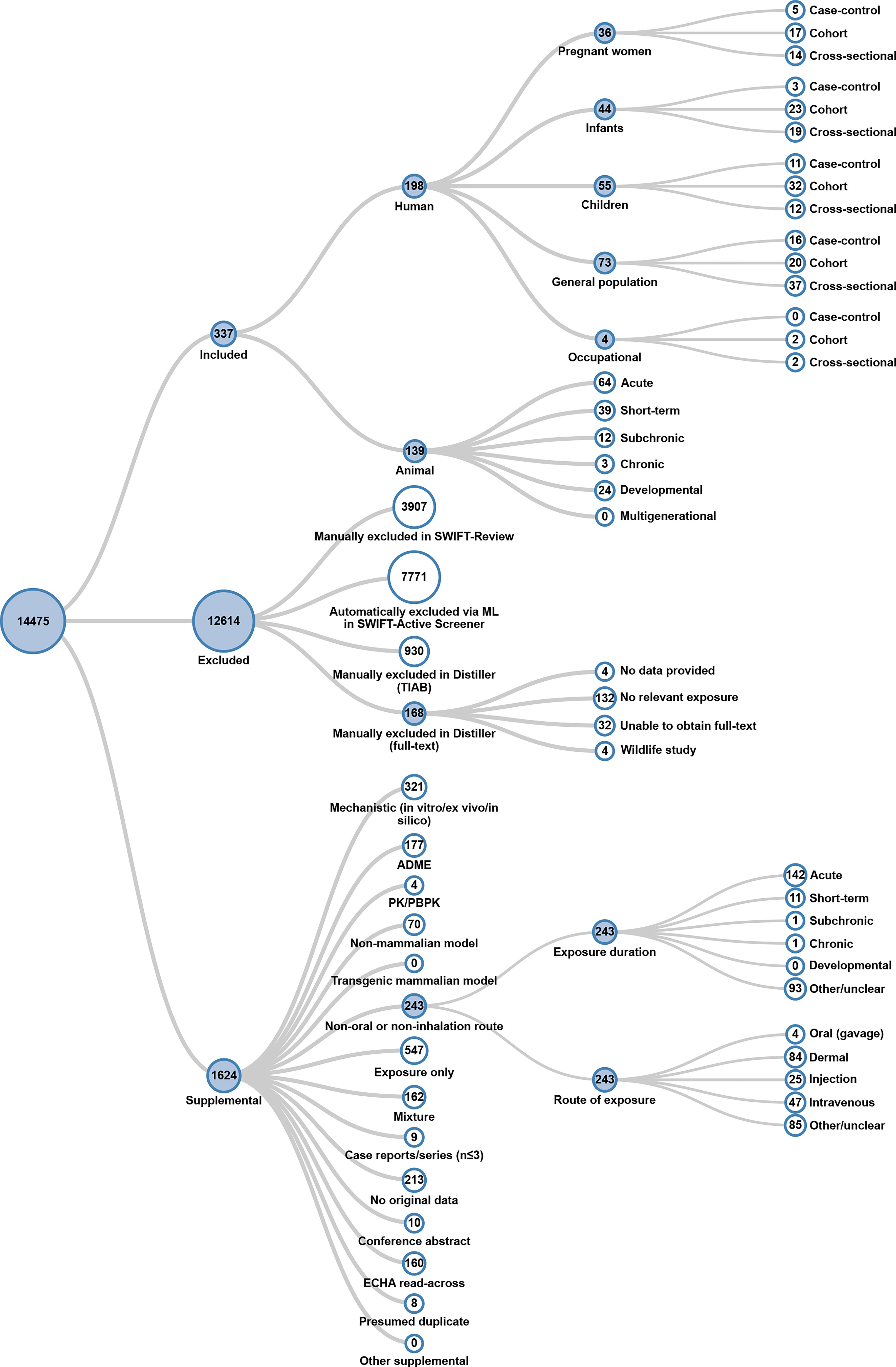

During full-text review, 337 studies were considered PECO-relevant (139 animal studies and 198 human studies), 168 studies were excluded, and 471 studies were tagged as supplemental material. Of the 139 animal studies, 56 were prioritized for study evaluation, and 55 proceeded to full extraction because they were of 21 d or longer exposure durations or exposures that occurred during reproduction or development. Literature search results are summarized graphically in Figure 3 and Figure 4. Chemical-specific literature trees are also available in HAWC51 (filter by visualization type “literature tagtree”). References are available in the literature trees by clicking Control or Command keys on a node.

Figure 4.

PFAS-150 literature inventory tree. Screenshot from interactive image accessed May 17, 2022.96 References are available in the literature inventory tree by Control-clicking or Command-clicking on a node. A full download of the literature review and study tagging can be found in Excel Table S13. Study counts for 1-bromoheptafluoropropane (CASRN 422-85-5; DTXSID3059971), 11:1 fluorotelomer alcohol (CASRN 423-65-4; DTXSID80375107), 6H-perfluorohex-1-ene (CASRN 1767-94-8; DTXSID10379850), perfluoroheptanoic acid (CASRN 375-85-9; DTXSID1037303), perfluorooctanesulfonamid (CASRN 76752-79-9; DTXSID001016256), and perfluoroundecanoic acid (CASRN 2058-94-8; DTXSID8047553) are only current through 2019. Note: ADME, absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion studies; ECHA, European Chemicals Agency; ML, machine learning; PFAS, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances; PK/PBPK, classical pharmacokinetic/physiologically based pharmacokinetic model studies; TIAB, title or abstract screening.

Use of a machine-learning software greatly expedited the screening process. Although SWIFT-Active Screener39 was used for this project, other machine-learning screening applications are available, and still others are being currently being developed, because the use of these applications is gaining widespread acceptance in systematic review processes.52 With the use of machine-learning software and a large team, the screening phase of the SEM was relatively quick. A screening team of 20 people was able to complete the TIAB level screening in 94 h spread across 10 business days (an average of 4.7 h per screener).

Details of Identified Epidemiological and Animal Studies

Human studies.

Literature inventory.

The human studies that met PECO criteria are summarized by study design, population, and health systems in Figure 5. Further details on the specific studies, exposure measurements, and chemicals evaluated are available in an interactive graphic.42 Table 5 also provides a high-level summary of which PFAS had at least one epidemiology study identified during literature inventory. A total of 199 human studies that included information on 16 different PFAS chemicals, including Nafion, were identified. The most frequently studied chemicals were perfluoroundecanoic acid (162 studies), perfluoroheptanoic acid (64 studies), perfluorooctanesulfonamide (38 studies), perfluorotridecanoic acid (35 studies), perfluorotetradecanoic acid (24 studies), perfluoroheptane sulfonic acid (22 studies), perfluoroheptanesulfonate (20 studies), and perfluoropentanoic acid (15 studies). The most common types of study design were cohort (90 studies) and cross-sectional (81 studies), followed by case–control (35 studies). The studies were primarily of the general population, sometimes including infants (), children (), and pregnant women. Only five studies were conducted in an occupational setting. Except for these occupational studies and one drinking-water study, all the identified studies measured exposure using biomonitoring of PFAS. The majority measured levels in blood, with a few studies measuring PFAS in breast milk, urine, semen, follicular fluid, or amniotic fluid. A wide range of health effects were considered. The most studied health systems were reproductive, metabolic, endocrine, cardiovascular, developmental, and immune systems.

Figure 5.

Survey of human studies that met PECO criteria summarized by study design, population, and health systems assessed. (A) This is a thumbnail image of the interactive dashboard accessed May 17, 2022.53 The numbers indicate the distinct number of studies that investigated a health system within a particular study design and population, not the number of studies that observed an association with PFAS exposure. If a study evaluated multiple health outcomes or populations, it is shown here multiple times, though totals reflect distinct numbers of studies. (B). This is a thumbnail image of the interactive dashboard that provides additional information like evaluated chemicals (searchable by name, CASRN, and DTXSID), exposure measurement information, and sex. Study counts for 1-Bromoheptafluoropropane (CASRN 422-85-5; DTXSID3059971), 11:1 Fluorotelomer alcohol (CASRN 423-65-4; DTXSID80375107), 6H-Perfluorohex-1-ene (CASRN 1767-94-8; DTXSID10379850), Perfluoroheptanoic acid (CASRN 375-85-9; DTXSID1037303); Perfluorooctanesulfonamid (CASRN 76752-79-9; DTXSID001016256), and Perfluoroundecanoic acid (CASRN 2058-94-8; DTXSID8047553) are only current through 2019. Note: CASRN, Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number; DTXSID, DSSTox substance identifier; PECO, population, exposure, comparator, and outcome; PFAS, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

Table 5.

PFAS chemicals identified in this SEM that had at least one animal or human study summarized in the literature inventory.

| Chemical name | CASRN | Animal evidence | Human evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Butanesulfonic acid, 1,1,2,2,3,3,4,4,4-nonafluoro-, salt with sulfonium, dimethylphenyl- (1:1) | 220133-51-7 | X | — |

| 1H,1H,2H-Perfluorocyclopentane | 15290-77-4 | X | — |

| 1H,1H,5H-Perfluoropentanol | 355-80-6 | X | — |

| 2-Chloro-1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane | 2837-89-0 | X | — |

| 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,6-Nonafluorohexene | 19430-93-4 | X | — |

| 3-Methoxyperfluoro(2-methylpentane) | 132182-92-4 | X | — |

| 6:2 Fluorotelomer alcohol | 647-42-7 | X | — |

| 6:2 Fluorotelomer methacrylate | 2144-53-8 | X | — |

| 6:2 Fluorotelomer sulfonic acid | 27619-97-2 | X | X |

| 8:2 Fluorotelomer alcohol | 678-39-7 | X | X |

| Dodecafluoroheptanol | 335-99-9 | X | — |

| Methyl perfluoro[3-(1-ethenyloxypropan-2-yloxy)propanoate] | 63863-43-4 | X | — |

| Nafion | 31175-20-9 | X | X |

| N-Ethyl-N-(2-hydroxyethyl)perfluorooctanesulfonamide | 1691-99-2 | X | — |

| N-Ethylperfluorooctanesulfonamide | 4151-50-2 | X | — |

| N-Methyl-N-(2-hydroxyethyl)perfluorooctanesulfonamide | 24448-09-7 | X | — |

| Perfluamine | 338-83-0 | X | — |

| Perfluoro(4-methoxybutanoic) acid | 863090-89-5 | X | — |

| Perfluoro(N-methylmorpholine) | 382-28-5 | X | — |

| Perfluoro(propyl vinyl ether) | 1623-05-8 | X | — |

| Perfluoro-1,3-dimethylcyclohexane | 335-27-3 | X | — |

| Perfluoro-1-iodohexane | 355-43-1 | X | — |

| Perfluoro-2,5-dimethyl-3,6-dioxanonanoic acid | 13252-14-7 | X | X |

| Perfluoro-3-methoxypropanoic acid | 377-73-1 | X | |

| Perfluoro-3-(1H-perfluoroethoxy)propane | 3330-15-2 | X | — |

| Perfluorobutanesulfonyl fluoride | 375-72-4 | X | — |

| Perfluorocyclohexanecarbonyl fluoride | 6588-63-2 | X | — |

| Perfluoroheptanesulfonate | 146689-46-5 | — | X |

| Perfluoroheptanesulfonic acid | 375-92-8 | — | X |

| Perfluoroheptanoic acid | 375-85-9 | — | X |

| Perfluoromethylcyclopentane | 1805-22-7 | X | — |

| Perfluorooctanesulfonamide | 754-91-6 | X | X |

| Perfluorooctanesulfonyl fluoride | 307-35-7 | X | X |

| Perfluoropentanoic acid | 2706-90-3 | X | X |

| Perfluoropropanoic acid | 422-64-0 | — | X |

| Perfluorotetradecanoic acid | 376-06-7 | X | X |

| Perfluorotridecanoic acid | 72629-94-8 | X | X |

| Perfluoroundecanoic acid | 2058-94-8 | X | X |

| Sodium perfluorodecanesulfonate | 2806-15-7 | — | X |

| Tetrabutylphosphonium perfluorobutanesulfonate | 220689-12-3 | X | — |

| Tetraethylammonium perfluorooctanesulfonate | 56773-42-3 | X | — |

| Trichloro((perfluorohexyl)ethyl)silane | 78560-45-9 | X | — |

| Triethoxy((perfluorohexyl)ethyl)silane | 51851-37-7 | X | — |

| Trifluoroacetic acid | 76-05-1 | X | X |

| Trifluoromethanesulfonic acid | 1493-13-6 | X | — |

Note: For perfluoroheptanoic acid and perfluoroundecanoic acid, data are only current through December 2019 because these PFAS were inadvertently excluded in the 2020 and 2021 literature search updates. —, no studies summarized in the literature inventory; CASRN, Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number; PFAS, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances; SEM, systematic evidence map; X, at least one study summarized in the literature inventory. An interactive visual summary of the information extracted in the literature inventory can be found in Tableau.53 For the most current information, please visit the web-based HAWC project page.45

Animal studies.

Literature inventory.

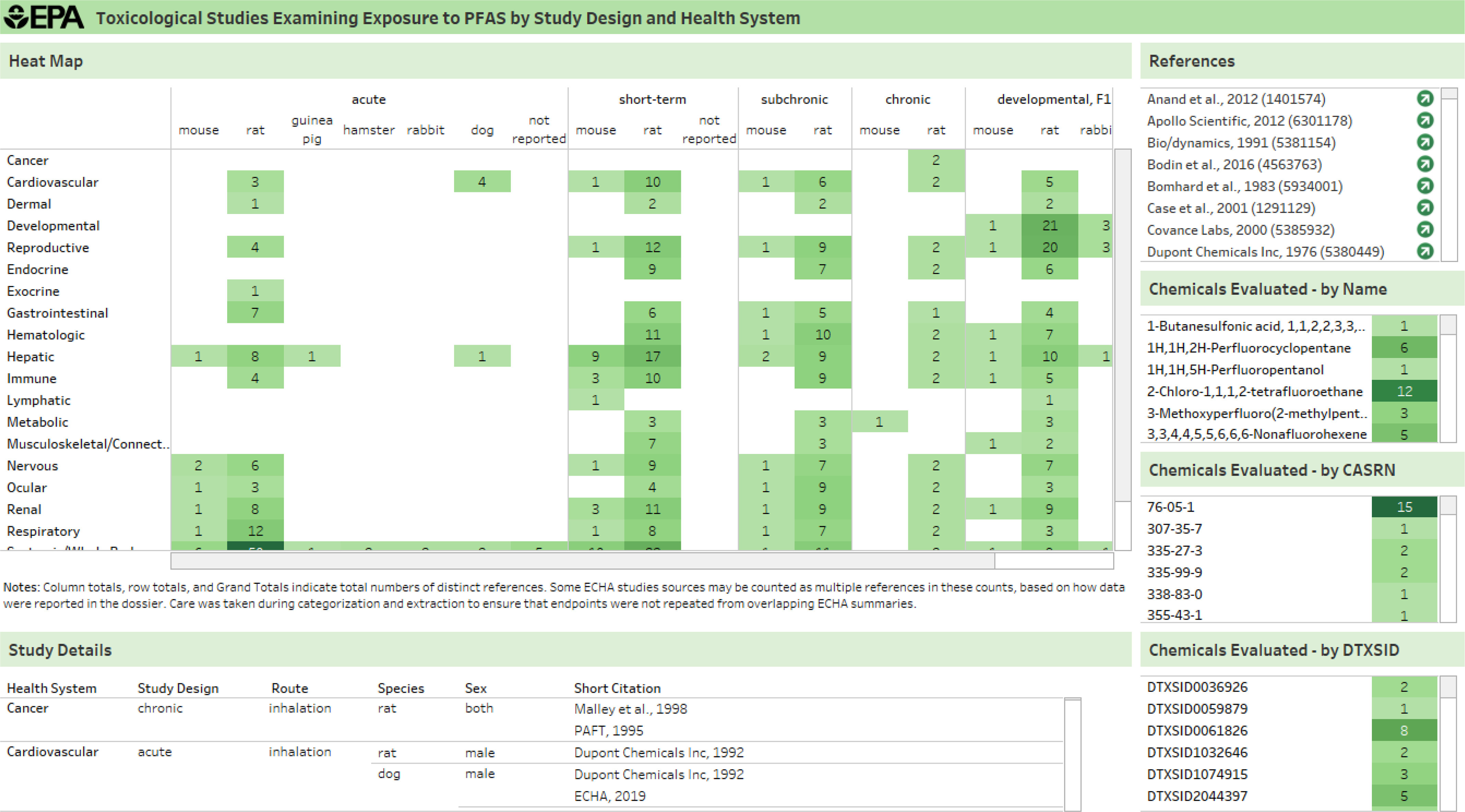

There were 140 animal studies that met PECO criteria. A survey of the animal model systems, study designs, and health effects is provided in Figure 6. Table 5 also provides a high-level summary of which PFAS had at least one animal toxicology study identified during literature inventory. Further details on specific studies, chemicals, and routes of exposure are available in an interactive graphic.53 The data underlying the graphic are available to download and are also available in Excel Table S12.

Figure 6.

Survey of animal studies that met PECO criteria by study design, species, and health systems. This is a thumbnail image of the interactive dashboard53 accessed May 17, 2022. The interactive dashboard is filterable by health system, study design, PFAS name, CASRN, and DTXSID. The numbers in the heat map inset indicate the distinct number of studies that investigated a health system within a particular study design. If a study evaluated multiple health outcomes or presented several experiments, it is shown here multiple times, though totals reflect distinct numbers of studies. The study design panel includes information on animal model, exposure duration, route of administration, and dose level(s) tested. Study counts for 1-Bromoheptafluoropropane (CASRN 422-85-5; DTXSID3059971), 11:1 Fluorotelomer alcohol (CASRN 423-65-4; DTXSID80375107), 6H-Perfluorohex-1-ene (CASRN 1767-94-8; DTXSID10379850), Perfluoroheptanoic acid (CASRN 375-85-9; DTXSID1037303); Perfluorooctanesulfonamid (CASRN 76752-79-9; DTXSID001016256), and Perfluoroundecanoic acid (CASRN 2058-94-8; DTXSID8047553) are only current through 2019. Note: CASRN, Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number; DTXSID, DSSTox substance identifier; PFAS, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

These studies evaluated exposure to 40 unique PFAS chemicals (including Nafion) administered orally (via gavage, diet, or water) or through inhalation (list of chemicals provided in Table 5). Of these, trifluoroacetic acid (15 studies); 2-chloro-1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane (12 studies); 6:2 fluorotelomer alcohol (11 studies); 6:2 fluorotelomer methacrylate (8 studies); perfluoro(propyl vinyl ether) (8 studies); 1H,1H,2H-perfluorocyclopentane (6 studies); and 6:2 fluorotelomer sulfonic acid (6 studies) were the most frequently studied compounds. Most studies were conducted in rats (110 studies) and mice (21 studies), but data were also available in rabbits, dogs, hamsters, and guinea pigs.

Data extraction.

Of the 140 studies, a subset of 52 studies focused on 21-d or longer exposure durations (or were reproductive or developmental studies) for 20 PFAS chemicals. These study designs were considered most suitable for identifying a subchronic or chronic POD and were prioritized for study evaluation and full data extraction in HAWC. The most commonly assessed health systems included the reproductive (e.g., male and female reproductive organ weights, fertility); developmental (e.g., pup weight and viability, lactation index, skull malformation); urinary (e.g., kidney weight, organ function measurements, such as blood urea nitrogen); immunological (e.g., spleen and/or thymus weight; blood components, such as monocytes, eosinophils, and lymphocytes); and hepatic (e.g., liver weight, enzyme activity, cholesterol, and lipid metabolism, total bilirubin, nonneoplastic lesions such as hepatocellular hypertrophy) systems.

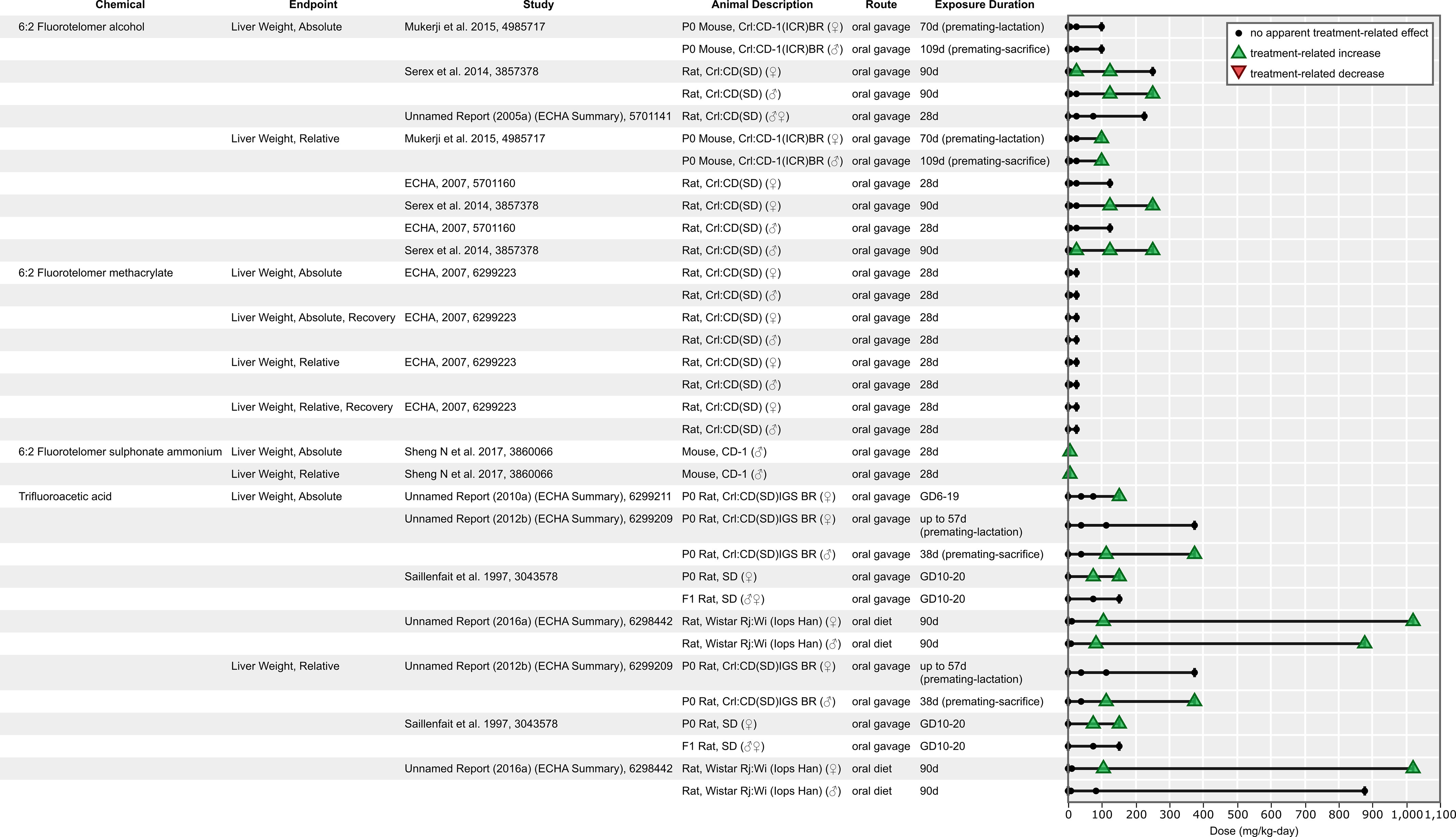

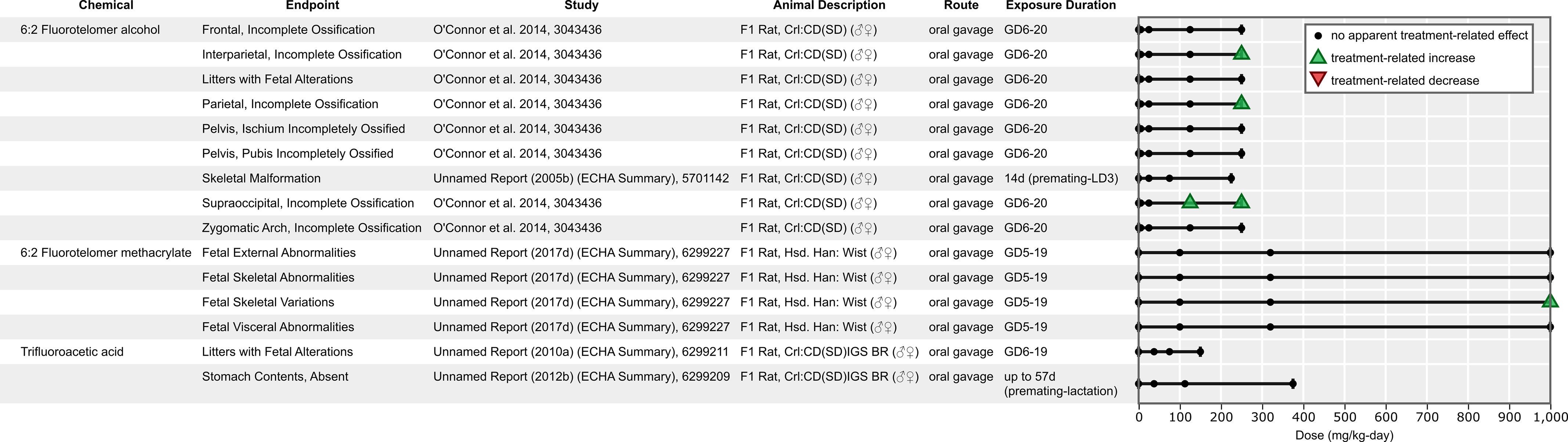

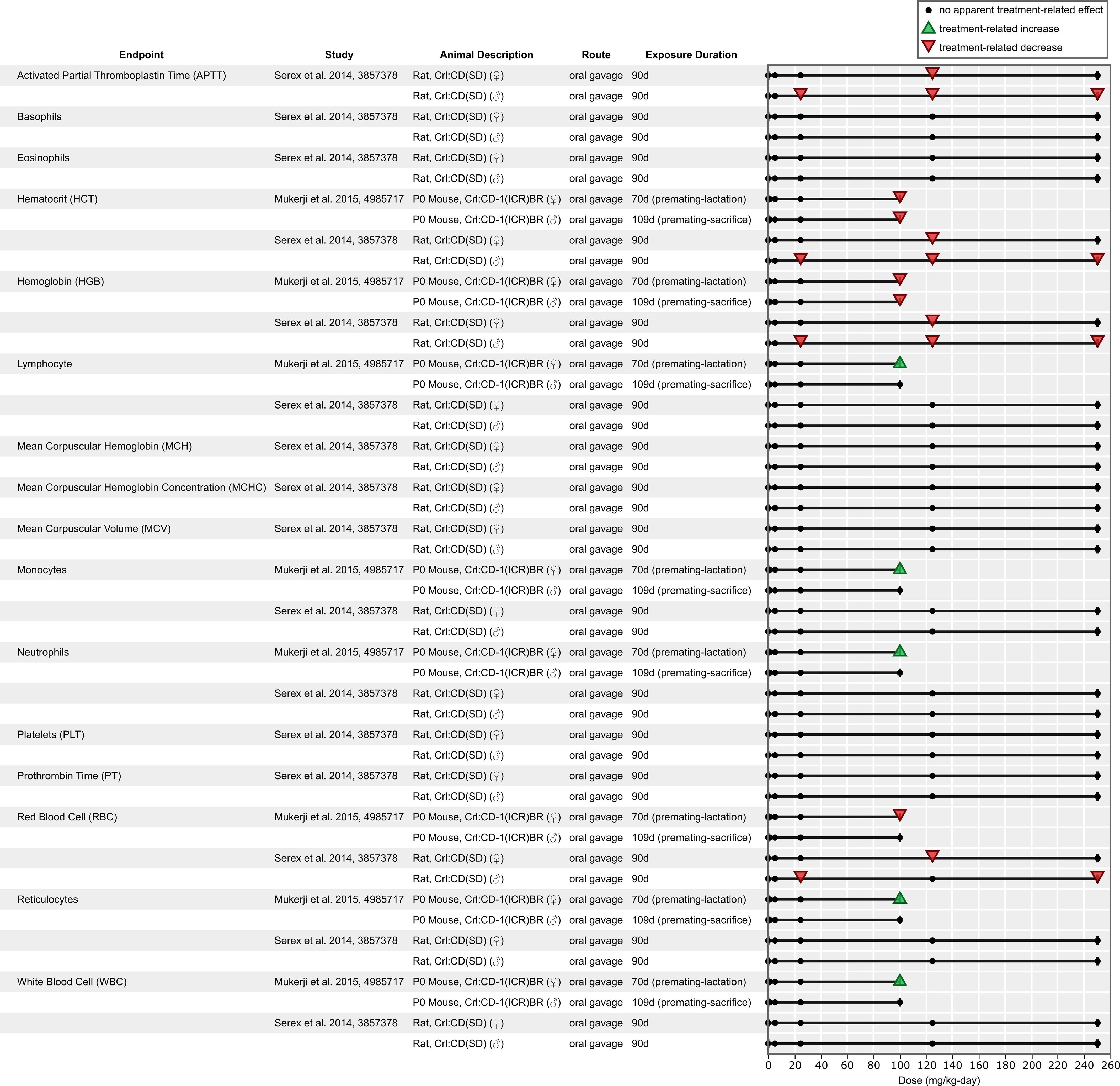

Figures 7, 8, and 9 present a small subset of example visualizations of the data extraction for some of the PFAS animal data. More than 75 visualizations summarizing 20 PFAS chemicals across 19 health effect systems are available but are not discussed here in the interest of brevity. Users can view visualizations by chemical name or by health effect system in HAWC. Table S3 also describes the inventory of HAWC data pivot visuals available by PFAS chemical and health category. HAWC visualizations include interactive literature tagging trees reflecting the literature identified for over 40 PFAS chemicals. Instead, we have presented a representative subset of data in this manuscript for different databases. For example, Figure 7 displays data on three chemicals that suggest an effect on liver weight due to the consideration of ECHA data [Trifluoroacetic acid (CASRN 76-05-1), 6:2 fluorotelomer alcohol (CASRN 647-42-7), and 6:2 fluorotelomer methacrylate (CASRN 17,527-29-6)], thereby highlighting the importance of gray literature. Figure 8 depicts three relatively data-rich chemicals [trifluoroacetic acid (CASRN 76-05-1), 6:2 fluorotelomer alcohol (CASRN 647-42-7), and 6:2 fluorotelomer methacrylate (CASRN 17,527-29-6)] that suggest an effect on offspring abnormalities. Last, we present Figure 9, which exemplifies a representative chemical [6:2 fluorotelomer alcohol (CASRN 647-42-7)] that does not clearly appear to be associated with a consistent effect of exposure for multiple end points (). Note, these examples are a small subset of the PFAS chemicals for which data were extracted. All data extraction visualizations (more than 75 figures) are available in HAWC by selecting visualization type “Data pivot (animal bioassay)” or “literature tagtree”51 The underlying literature review and tagging data are also available in Excel Table S13.

Figure 7.

Survey of liver weight findings among the most studied PFAS included in the systematic evidence map with animal toxicology evidence (trifluoroacetic acid, 6:2 fluorotelomer alcohol, 6:2 fluorotelomer sulphonate ammonium, 6:2 fluorotelomer methacrylate). Screenshot is shown of interactive version accessed May 17, 2022.97 Note: 6-digit number in “Study” column, Health and Environmental Research Online (HERO) identification; d, days; ECHA, European Chemicals Agency; GD, gestation day; PFAS, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

Figure 8.

Survey of developmental findings among the most studied PFAS included in the systematic evidence map with animal toxicology evidence (trifluoroacetic acid, 6:2 fluorotelomer alcohol, 6:2 fluorotelomer methacrylate). Screenshot of interactive version98 accessed May 17, 2022 is shown. Note: 6-digit number in “Study” column, Health & Environmental Research Online (HERO) identification; d, days; ECHA, European Chemicals Agency; GD, gestation day; PFAS, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

Figure 9.

Survey of hematological findings for 6:2 fluorotelomer alcohol for animal toxicology studies. Screenshot of interactive version99 accessed May 17, 2022 is shown. Note: 6-digit number in “Study” column, Health & Environmental Research Online (HERO) identification; d, days.

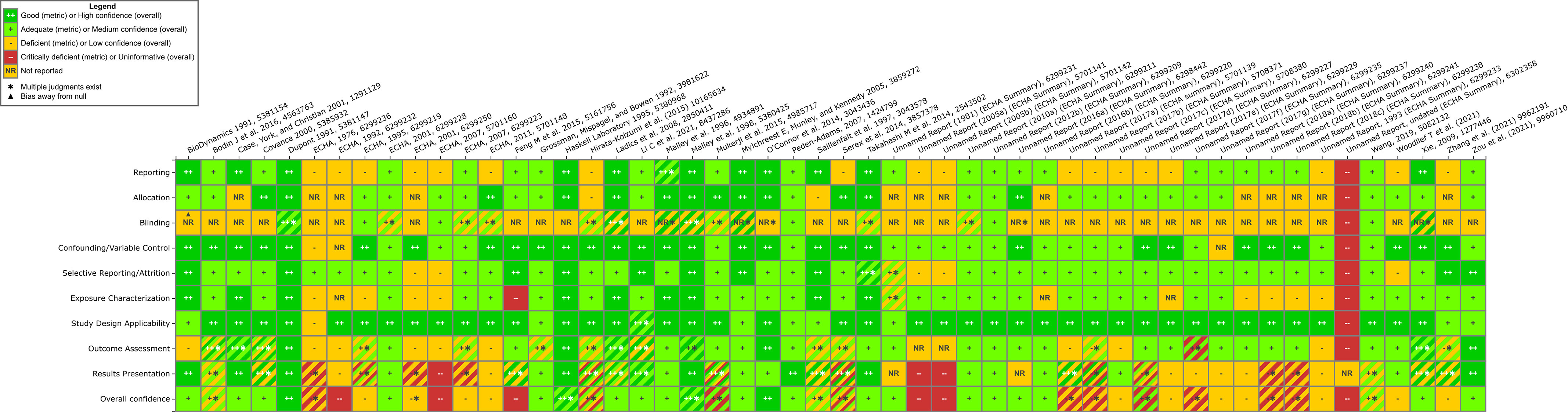

Study evaluation.

Study evaluations of all the animal studies are summarized in Figure 10, and rationales for each domain and overall confidence ratings are available in an interactive graphic in HAWC.54 Excel Table S12 also contains the full study evaluation report of the findings summarized in HAWC. The majority of the identified literature for PFAS were from ECHA summaries (27 ECHA summaries); however, these summaries typically lack details on the methods and results, resulting in ratings of low confidence or uninformative for specific end points or overall. Just over 10% (6 out of 53) of all the animal studies identified were rated as uninformative overall; all were ECHA summaries. Another 22 studies were identified as low confidence for specific end points or overall, and again they were mostly ECHA summaries. The lack of reporting and public access to the underlying primary study information is a barrier to usage of ECHA records in many assessment contexts. However, there may be instances where using ECHA data is useful. For example, in data-poor scenarios, ECHA records may be the only available information and could perhaps be used in screening-level analyses. Additionally, for data-poor chemicals that may be undergoing read-across assessments, ECHA records can be used to look for consistency in hazard effects. For researchers, ECHA records can indicate the existence of toxicology studies that may not be represented in databases of the peer-reviewed literature. This information can be helpful in designing new toxicity studies to address data gaps.

Figure 10.

Study evaluation results for animal studies. Figure is presented as a thumbnail for reference. Screenshot of interactive version54 accessed May 17, 2022 is shown. A full download of study evaluation summaries is also available in Excel Table S12. Note: ECHA, European Chemicals Agency.

For the most part, studies that were not ECHA summaries were considered well-conducted (medium or high overall confidence for the outcomes assessed). An interactive graphic can be found in HAWC.55 Over 50% of studies received ratings of medium or high confidence overall (30 out of 53). The exception was Feng et al.,56 in which the Nafion was administered as Nafion membrane. Nafion membranes are composed of and release fluoride, and the study’s internal fluoride measurements indicated that the Nafion was not absorbed. Outcome-specific judgments sometimes varied within a study, usually based on the presentation of the results, and they are indicated by hashing in the visualizations. Information was also rarely reported on blinding, which contributed to low scores for this domain across the board.

Discussion

Our main goal in conducting this SEM was to use systematic review methods to compile, summarize, and disseminate the evidence (including gray literature) pertinent to future efforts to characterize potential human health concerns for PFAS chemicals and Nafion. Evidence synthesis of the available data goes beyond the scope of this SEM.23 We found 140 animal bioassay studies evaluating 38 PFAS and 199 epidemiology studies evaluating 15 PFAS (summarized in Table 5) We prioritized studies of 21-d and longer and reproduction/developmental designs to extract data for 20 PFAS across 19 health effect categories, which are summarized in more than 75 visualizations.51 The visualizations can be viewed by PFAS chemical or by health system. A full inventory listing of the available visualizations by PFAS chemical is available in Table S3. The full underlying extracted data can be downloaded in HAWC and are available in Excel Table S10.

Because so few PFAS have animal and human data, it is apparent that many PFAS are data poor, and more studies are needed to fully characterize the range of chemistries represented by these diverse structures and their toxicities. Although study evaluations were completed for PECO-relevant studies of duration, in many cases insufficient reporting quality of methodological details or results made it impossible to fully evaluate the quality of the data. In the future, author outreach could be used for recent peer-reviewed studies to identify any missing or unreported data that might improve study quality ratings. Gray literature studies often also had limited reporting quality, which impacted study ratings.

Although previous research efforts have made some efforts to systematically identify PFAS research for a subset of 29 chemicals,35,57 our present effort is unique in several ways. We focused on a larger group of PFAS chemicals (), and we included gray literature sources (such as ECHA data), whereas the former effort largely relied on references identified through PubMed.34 They did include in vitro studies in their analysis, which differs from this approach, which focused on human and animal evidence.

For future consideration and expansion of the PFAS evidence mapping work, hundreds of injection- or dermal-exposure studies that we considered supplemental information were identified (full study list is provided in Excel Table S14). It is possible that some of these studies may provide additional information to support hazard identification for data-poor PFAS. Except for a few PFAS that are being reviewed by ATSDR (e.g., PFHpA, PFUA, and PFOSA),58 we are not aware of existing or in-progress assessment work for the PFAS included in this SEM. One limitation of this analysis is that it excluded some of the more data-rich PFAS (e.g., PFBA, PFHxA, PFOA, PFNA, PFDA, PFBS, PFHxS, PFOS, and GenX) already under assessment by the U.S. EPA. This exclusion was done to avoid duplication of work but does limit ability to evaluate the evidence base across PFAS. However, the evidence map dashboard is being expanded to include these PFAS and is expected to be available in 2022.

As described in the introduction, this SEM was initiated to complement experimental in vitro work, including cell-based high-throughput assays and toxicokinetic assays run on the PFAS included in the SEM.20 In addition to this application, given the high degree of interest in PFAS, we hope disseminating this information can help identify key research needs and facilitate additional assessment work (e.g., BMD analyses on extracted data in HAWC). With respect to testing, given the large number of PFAS chemicals, new testing needs to be done in a targeted and strategic manner. The current SEM should help inform such activities.

This analysis is the first installment of a series of anticipated PFAS SEMs, ultimately culminating in a future analysis of 12,034 substances currently registered as PFAS in the U.S. EPA Dashboard of which 10,776 have structures.59 Disseminating the available human and animal data for PFAS chemicals represents an important first step in identifying research needs and data gaps.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank V. Soto and D. Shams for document production support and S. Foster and D. Hoff for internal review. The authors would also like to thank the following ICF International staff members for assistance in screening studies and creating Tableau visualizations and HAWC trees: C. Austin, K. Duke, H. Eglinton, K. Geary, A. Goldstone, L. Green, J. Greig, S. Hearn, A. Ichida, E. Lee, C. Lieb, J. Luh, R. McGill, E. Murray, A. Murphy, P. Piatos, J. Rochester, A. Ross, A. Schumacher, J. Seed, C. Sibrizzi, S. Snow, P. Soleymani, M. Socha, J. Trgovcich, A. Williams, and C. Xiong.

This material has been funded in part by the U.S. EPA under contract 68HERC19D0003 to ICF International. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the U.S. EPA. Any mention of trade names, products, or services does not imply an endorsement by the U.S. government or the U.S. EPA. The U.S. EPA does not endorse any commercial products, services, or enterprises.

References