Abstract

Lactococcus garvieae (junior synonym, Enterococcus seriolicida) is a major pathogen of fish, producing fatal septicemia among fish species living in very diverse environments. The phenotypic traits of L. garvieae strains collected from three different continents (Asia, Europe, and Australia) indicated phenotypic heterogeneity. On the basis of the acidification of d-tagatose and sucrose, three biotypes were defined. DNA relatedness values and a specific PCR assay showed that all the biotypes belonged to the same genospecies, L. garvieae. All of the L. garvieae strains were serotyped as Lancefield group N. Ribotyping proved that one clone was found both in Japan, where it probably originated, and in Italy, where it was probably imported. PCR of environmental samples did not reveal the source of the contamination of the fish in Italy. Specific clones (ribotypes) were found in outbreaks in Spain and in Italy. The L. garvieae reference strain, isolated in the United Kingdom from a cow, belonged to a unique ribotype. L. garvieae is a rising zoonotic agent. The biotyping scheme, the ribotyping analysis, and the PCR assay described in this work allowed the proper identification of L. garvieae and the description of the origin and of the source of contamination of strains involved in outbreaks or in sporadic cases.

During the last decade, sporadic and epidemic outbreaks of fish diseases due to gram-positive cocci have been reported from different parts of the world, including Japan (18), Korea (14), Italy (11), Spain (8, 24, 26), France (22), Australia (5), Israel (9, 10), and the United States (2, 10). Taxonomic studies have indicated that at least six different species of gram-positive cocci are associated with fish diseases: Streptococcus parauberis (8), Streptococcus iniae (10), Streptococcus difficile (9), Lactococcus piscium (29), Vagococcus salmoninarum (22), and Lactococcus garvieae (junior synonym, Enterococcus seriolicida (7, 11, 18). Some pathogens are well adapted to a specific host; others, like L. garvieae, are ubiquitous. L. garvieae, originally isolated in the United Kingdom from a mastitic udder (6), has been recovered from fish species living in very diverse conditions: yellowtail cultured in a marine environment in the Far East and trout raised in temperate freshwater in Europe and in Australia. L. garvieae strains also have been isolated from humans, indicating the expanding importance of this bacterium (12).

Little is known about the ecological distribution, the source of infection, and the modalities by which L. garvieae is transmitted between fish. The epidemiological relationship between strains isolated from fish has never been investigated. The published identification scheme for L. garvieae, based on biochemical and antigenic characteristics (6, 7, 12, 17), can barely differentiate L. garvieae from Lactococcus lactis and from “Enterococcus-like” strains isolated from diseased fish (24, 26). A clindamycin test (13) and a PCR assay (30) are the only tests able to differentiate L. garvieae from L. lactis definitively. The paucity of knowledge prompted us to investigate this organism. Different L. garvieae strains collected from diseased fish from three different continents (Asia, Australia, and Europe) were analyzed by phenotypic, genetic, and molecular methods. DNA relatedness values and PCR analysis confirmed the wide geographical distribution of this species, and phenotypic traits demonstrated the existence of different biotypes. Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) ribotyping was found to be an efficient tool for studying the epidemiology of L. garvieae in fish, suggesting possible routes of infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The eight Italian L. garvieae strains were randomly taken from a collection of over 100 strains recovered from different outbreaks in trout between May 1992 and August 1995. Japanese strains, isolated from diseased yellowtail, were kindly supplied by F. Salati. Spanish and Australian strains, all isolated from trout, were kindly provided by A. Cacho and J. Carson, respectively. S. iniae ATCC 29178T, E. seriolicida ATCC 49156T, and L. garvieae ATCC 43921T were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md. L. piscium NCFB 2778T, L. lactis NCFB 604T, and V. salmoninarum NCFB 2777T were purchased from the National Collection of Food Bacteria, Reading, United Kingdom. S. difficile CIP 103769T was from our own collection. Bacteria from stock cultures stored in 10% glycerol at −70°C were grown on Columbia agar base (Difco) plates supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) defibrinated sheep blood at 24°C for 24 h, when characteristic alpha-hemolytic colonies became visible.

TABLE 1.

Origins, DNA-DNA homologies, biotypes, and ribotypes of the strains used in this study

| Straina | Originb (animal species, locality, and/or country) | RBRc for L. garvieae ATCC 43921T | EcoRI ribotype | HindIII ribotype | Biotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. garvieae ATCC 43921T | Cattle, United Kingdom | 100 (0) | a | i | 1 |

| E. seriolicida ATCC 49156T | Yellowtail, Kochi, Japan | 82 (0.7) | a | h | 1 |

| L. garvieae ITP1072 | Trout, T. Pallav., Italy | 78 (0.9) | a | c | 1 |

| L. garvieae ITP1313 | Trout, T. Pallav., Italy | 85 (0.4) | a | c | 1 |

| L. garvieae ITP1545 | Trout, T. Pallav., Italy | 77 (0.7) | a | c | 1 |

| L. garvieae ITP1794 | Trout, Cassolnovo, Italy | 74 (1.1) | a | c | 1 |

| L. garvieae ITP1814 | Trout, Cerano, Italy | 72 (0.8) | a | c | 1 |

| L. garvieae ITP1964 | Trout, Cassalnovo, Italy | 87 (0.4) | a | c | 1 |

| L. garvieae ITP2001 | Trout, Cassalnovo, Italy | 85 (0.3) | a | c | 1 |

| L. garvieae ITP2036 | Trout, Cerano, Italy | 86 (0.8) | a | d | 1 |

| L. garvieae S1449 | Yellowtail, Japan | 73 (2.3) | a | c | 1 |

| L. garvieae S014 | Yellowtail, Japan | 71 (2.3) | a | e | 1 |

| L. garvieae 88/1400 | Trout, Australia | 75 (1.3) | a | g | 2 |

| L. garvieae Sp1 | Trout, Segovia, Spain | 73 (2.2) | b | f | 3 |

| L. garvieae Sp2 | Trout, Guadalajara, Spain | 75 (1.7) | b | f | 3 |

| L. garvieae Sp3 | Trout, Guadalajara, Spain | 73 (1.8) | b | f | 3 |

| L. lactis NCFB 604T | Denmark | 39 (6.0) | |||

| S. iniae ATCC 29178T | San Francisco, United States | 32 (8.0) | |||

| S. difficile CIP 103769T | Tilapia, Ein Hanatziv, Israel | 16 (14) | |||

| L. piscium NCFB 2778T | United States | 27 (4.5) | |||

| V. salmoninarum NCFB 2777T | United States | 30 (8.4) |

ITP, Collection of the Experimental Institute for Zooprophylaxis, Turin, Italy; CIP, Collection de l’Institut Pasteur, Paris, France.

T. Pallav., Torre Pallavicina.

Expressed as a percentage of homologous binding. The values in parentheses are ΔTm(e) values in degrees Celsius. ΔTm(e) values reflect the degree of divergence among related DNA sequences.

Biochemical and enzymatic tests.

Biochemical tests (acidification of carbohydrates) and enzymatic tests were performed with the API 20 Strep and API 50CH systems (bioMerieux S.A., Marcy l’Etoile, France). Tests were done in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturer, except for the temperature of incubation, which was set at 24°C. Additional tests included the ability to grow on skim milk (Difco) agar plates supplemented with 0.1 and 0.3% (wt/vol) methylene blue (Sigma); growth at 10, 42, and 45°C; growth in the presence of 10 and 40% (wt/vol) bile salts agar (oxgall; Difco); growth on tryptic soy agar (Difco) containing 4 and 6.5% NaCl; and growth on brain heart infusion agar at a range of pH values (7.0 to 9.6).

Hyperimmune sera and group antigen.

New Zealand White rabbits, 1 kg each, were immunized with formalin-fixed E. seriolicida ATCC 49156T and L. garvieae ATCC 43921T, ITP2001, and S1449 whole cells by methods described by Lancefield (19, 20) and MacCarthy and Lancefield (21). Specific group antigens were extracted by exposure of the bacteria to 0.2 N HCl for 10 min at 100°C (19). L. lactis NCFB 717 was used as a positive control for type N antigen. Capillary precipitin tests were performed by the method of Lancefield (19), and immunodiffusion tests were performed by the agar gel method of Ouchterlony (25).

DNA-DNA hybridizations and PCR assay.

The methods used to lyse gram-positive cocci and to extract the DNA content have been described elsewhere (9). DNA-DNA hybridizations were done by the hydroxyapatite (Bio-Rad) method (3) with modifications regarding the volumes used as described previously (11). Reactions were done in duplicate, and each run was performed twice. The levels of DNA relatedness (relative binding ratio [RBR]) and the differences in melting points between the homologous reactions and the heterologous reactions for the labeled reference strains and other strains [ΔTm(e)] were calculated as described before (3, 9). The rate of reassociation of the labeled DNA was routinely 5 to 6%; this value was subtracted from the absolute ratios of the hybridizations. An L. garvieae species-specific PCR assay was performed on all the strains as described previously (30). Ten water samples (100 ml) from Italian trout pounds where L. garvieae infection was active were centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 20 min. The resulting pellet was boiled and submitted to the PCR assay (30).

Ribotyping.

Genomic DNAs (4 μg) were digested with 50 U each of restriction enzymes HindIII and EcoRI (Promega) at 37°C for 16 h under the conditions specified by the manufacturer. DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel (20 cm long) at 55 V for 17 h in 49 mM Tris acetate–2 mM EDTA and blotted onto a positively charged nylon membrane (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The DNA was fixed by UV cross-linking. Prehybridization and hybridization for 3 and 20 h, respectively, were carried out with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–1 M NaCl–1% sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% dextran sulfate–0.1% blocking reagent. The DNA probe used was a 7.5-kb BamHI fragment of pKK3535 (kindly supplied by G. Glazer, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem), which is a pBR322-derived plasmid comprising the complete Escherichia coli rRNA B operon (4). The DNA probe was labeled by use of a random oligopriming kit (Boehringer) with a mixture of nucleotides and reverse transcriptase in the presence of 0.35 mM digoxigenin-11-dUTP (Boehringer). After hybridization, the filters were washed twice with 0.15 M sodium citrate solution containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 15 min at room temperature. Chemiluminescence was detected as recommended by the manufacturer (Boehringer) by incubating the membranes in the presence of an antidigoxigenin antibody linked to alkaline phosphatase and the alkaline phosphatase substrate AMPPD [3-(2′-spiroadamantane)-4-methoxy-4-(3"-phosphoryloxy)-phenyl-1,2-dioxe-tane]. Filters were autoradiographed by exposure to X-Omat AR 5 films (Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.) from 10 to 120 min at room temperature. Each different combination of patterns was considered a ribotype.

RESULTS

DNA-DNA hybridizations and PCR assay.

RBR and ΔTm(e) values for the DNAs of the various L. garvieae strains and E. seriolicida ATCC 49156T DNA hybridized with labeled L. garvieae ATCC 43921T DNA ranged from 71 to 87% and 0.3 to 2.3°C, respectively (Table 1). The values for L. lactis DNA hybridized with labeled L. garvieae ATCC 43921T DNA were 39% and 6°C, confirming that L. lactis and L. garvieae are genetically different species (Table 1). All of the L. garvieae strains (field and reference strains) submitted to the PCR assay produced a characteristic fragment of 1,100 bp (data not shown). No water sample was found positive by the PCR assay.

Phenotypic studies and serotyping of L. garvieae isolates.

All the strains had several common characteristics: growth at 10 and 42°C, in the presence of 40% bile salts, at pH 9.6, and on 0.3% methylene blue–milk agar. Although scant, growth also was observed on 6.5% NaCl agar and at 45°C. All isolates were alpha-hemolytic. Acetoin production (Voges-Proskauer reaction) and the presence of the enzymes pyrallidonylarylamidase, leucine arylamidase, and arginine dehydrolase were common to all isolates. The following tests were negative for all the L. garvieae strains: reduction of hippurate; production of α- and β-galactosidase, β-glucoronidase, and alkaline phosphatase; and utilization of erythritol, d-arabinose, d- and l-xylose, m-xyloside, l-sorbose, rhamnose, dulcitol, inositol, α-m-d-glucoside, inulin, melezitose, d-raffinose, glycogen, xylitol, d-turanose, l-lyxose, d- and l-fucose, d- and l-arabitol, gluconate, and 2- and 5-ketogluconate. All the L. garvieae strains produced acid from ribose, galactose, d-glucose, d-fructose, d-mannose, mannitol, N-α-glucosamine, amygdalin, arbutin, esculin, salicin, cellobiose, maltose, trehalose, and β-gentobiose.

The Italian, Japanese, and reference ATCC strains which acidified the above-mentioned carbohydrates were characterized as biotype 1 strains. The Australian strain 88/1400 acidified, in addition, d-tagatose (biotype 2 strain). The Spanish strains acidified sucrose (biotype 3 strains) in addition to the sugars acidified by the biotype 2 strain.

The capillary precipitin test and the Ouchterlony test showed that all the strains were part of Lancefield group N.

RFLP ribotyping.

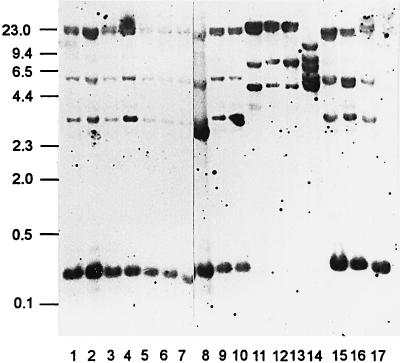

EcoRI- and HindIII-digested L. garvieae DNAs resulted, respectively, in two and seven different patterns (ribotypes a and b and c to i) (Fig. 1 and 2). After Southern blot hybridization, EcoRI-digested DNAs resulted in three or four detectable fragments ranging from 23 to 0.3 kb. The distribution of the bands allowed the definition of two ribotypes. Italian and Japanese strains, as well as the Australian strain and the two ATCC reference strains, belonged to the same ribotype, a (Fig. 1, lanes 1 to 10 and 15 to 17). Spanish strains were designated ribotype b strains (Fig. 1, lanes 11 to 13).

FIG. 1.

RFLP ribotyping of EcoRI digests. Numbers on the left are in kilobases. Lanes: 1 to 8, ITP1072, IPT1313, IPT1545, IPT1794, IPT1814, IPT1964, IPT2001, and IPT1036; 9 and 10, S1449 and S014; 11 to 13, Sp1, Sp2, and Sp3; 14, L. piscium NCFB 2778T; 15, 88/1400; 16, E. seriolicida ATCC 49156T; 17, L. garvieae ATCC 43921T.

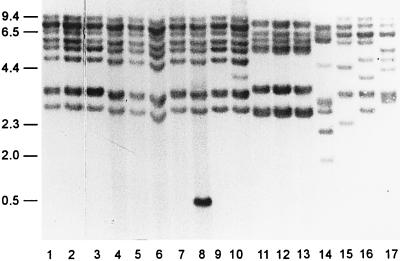

FIG. 2.

RFLP ribotyping of HindIII digests. Numbers on the left are in kilobases. Lanes are as defined in the legend to Fig. 1.

HindIII digests generated more polymorphisms, producing six to nine reproducible restriction fragments ranging from 9.4 to 0.5 kb. Seven Italian strains and one Japanese strain had a common pattern (ribotype c strains) (Table 1 and Fig. 2, lanes 1 to 7 and 9). One Italian strain (ITP2036) and one Japanese strain (S014) differed only slightly from ribotype c strains. Strain ITP2036 (ribotype d) had an additional 0.5-kb restriction fragment (Fig. 2, lane 8), whereas strain S014 (ribotype e) was characterized by the presence of an additional 4.0-kb restriction fragment (Fig. 2, lane 10). The restriction pattern of all Spanish strains was identical, displaying six restriction fragments (ribotype f) (Fig. 2, lanes 11 to 13). The Australian strain and the two ATCC reference strains (E. seriolicida ATCC 49156T and L. garvieae ATCC 43921T) had different patterns, which were designated, respectively, ribotype g (Fig. 2, lane 15), ribotype h (Fig. 2, lane 16), and ribotype i (Fig. 2, lane 17).

All the ribotypes obtained with the L. garvieae strains were different from those obtained with the reference strain of an unrelated species, L. piscium NCFB 2778T (Fig. 1 and 2, lanes 14).

DISCUSSION

Based on phenotypic characteristics, gram-positive cocci isolated from fish and able to grow at 10 and 42°C, in the presence of 40% bile salts, at pH 9.6, and on 0.3% methylene blue–milk agar (with scant growth also on 6.5% NaCl agar and at 45°C) should be classified as L. garvieae. None of the other five species of gram-positive cocci pathogenic for fish grow under these conditions. However, the existence of different L. garvieae biotypes emphasizes the difficulties of definitive identification based on phenotypic traits alone. Therefore, final identification cannot be determined without the support of genetic data.

Indeed, the physiological features of a defined bacterial species should be expressed in terms of percentages rather than as clear-cut characteristics. Murray (23) found that 56% of lactococci tested were able to grow on 6.5% NaCl and that 25% of them were also able to grow at 45°C and at pH 9.6. In the 9th edition of Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology (17), the inability to grow at 45°C and at pH 9.6 is considered a cardinal feature enabling lactococci to be distinguished from enterococci (which do grow under these conditions). The implementation of rigid criteria might therefore lead to inaccuracy. Serological data are also not conclusive, as a serogroup can encompass various bacterial species. The criteria of DNA relatedness levels of 70% or more, accepted as the major criterion for delineating genospecies (16, 28), proved that all the strains studied in this work belonged to the L. garvieae genospecies, regardless of the biotype. The species-specific PCR assay confirmed that all the studied strains belonged to the same species, L. garvieae (30).

Phenotypic traits indicated that a single L. garvieae clone was involved in each of the outbreaks which occurred in Italy and Japan (biotype 1) and that another clone was responsible for the Spanish outbreak (biotype 3). rRNA gene restriction patterns (RFLP ribotyping), first proposed by Grimont and Grimont (15), allowed us to refine the discrimination among strains of the same species. EcoRI digests of Italian and Japanese isolates were found to be identical, substantiating the hypothesis of a straightforward correlation between phenotype and epidemiological source. However, HindIII digests revealed that of the three Japanese strains, only one had the same ribotype as the Italian strains (ribotype c), the second was only closely related, and the third was a totally unrelated epidemiological clone. The variety in ribotypes among Japanese strains is not surprising given that the disease appeared in Japan years (18) before being diagnosed in Europe (7) and that no control measures were available. The Italian and Japanese strains with identical biotypes and identical HindIII and EcoRI ribotypes raised the possibility that the disease spread from Japan to Italy through the import of livestock or fish food. Unfortunately, the PCR assay applied to water samples could not provide an adequate answer regarding the source of contamination in Italy (environment or food). The Spanish strains belonged to a single biotype (biotype 3) and to a single ribotype, indicating that the outbreak in Spain was due to a single epidemiological clone which evolved separately. Since only one Australian isolate was included in this study, no similar conclusion can be drawn regarding L. garvieae infection in Australia. Finally, the RFLP ribotyping showed that L. garvieae ATCC 43921T, originally isolated from a mastitic udder, is a clone different from the Italian and Japanese strains, although it is phenotypically identical.

The data presented here emphasize the biodiversity of L. garvieae strains isolated from various animal sources and continents and show that ribotyping and biotyping can be efficient tools for tracing possible methods of dissemination of this emerging pathogen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by a joint American-Israeli grant (BARD IS-2307-93).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aoki T, Taklami K, Kitao T. Drug resistance in a non hemolytic Streptococcus spp. isolated from cultured yellowtail, Seriola quinqueradiata. Dis Aquat Org. 1990;8:171–177. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baya A M, Lupiani B, Hetrick F M, Roberson B S, Lukakovic R, May E, Poukish C. Association of Streptococcus sp. with fish mortalities in the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. J Fish Dis. 1990;41:251–253. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner D J, Fanning G R, Rake A V, Johnson K E. Batch procedure for thermal elution of DNA from hydroxyapatite. Anal Biochem. 1969;28:447–459. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(69)90199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brosius J, Ulrich A, Raker M A, Gray A, Dull T J, Gutell R R, Noller H F. Construction and fine mapping of recombinant plasmids containing the rrnB ribosomal RNA operon of E. coli. Plasmid. 1981;6:112–118. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(81)90058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carson J, Gudkovs N, Austin B. Characteristics of an Enterococcus-like bacterium from Australia and South Africa, pathogenic for rainbow trout (Onchorynchus mykiss Walbaum) J Fish Dis. 1993;16:381–388. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins M D, Farrow F A E, Phillips B A, Kandler O. Streptococcus garvieae sp. nov. and Streptococcus plantarum sp. nov. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;129:3427–3431. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-11-3427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Domenech A, Prieta J, Fernandez-Garayzabal J F, Collins M D, Jones D, Dominguez L. Phenotypic and phylogenetic evidence for a close relationship between Lactococcus garvieae and Enterococcus seriolicida. Microbiologia. 1993;9:63–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domenech A, Fernandez-Garayzabal J F, Pascual C, Garcia J A, Cutuli M T, Moreno M A, Collins M D, Dominguez L. Streptococcosis in cultured turbot, Scophthalmus maximus (L.), associated with Streptococcus parauberis. J Fish Dis. 1996;19:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eldar A, Bejerano Y, Bercovier H. Streptococcus shiloi and Streptococcus difficile: two new streptococcal species causing a meningoencephalitis in fish. Curr Microbiol. 1994;28:139–143. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eldar A, Frelier P F, Assenta L, Varner P W, Lawhon S, Bercovier H. Streptococcus shiloi, the name for an agent causing septicemic infection in fish, is a junior synonym of Streptococcus iniae. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:840–842. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-4-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eldar A, Ghittino C, Asanta L, Bozzetta E, Goria M, Prearo M, Bercovier H. Enterococcus seriolicida is a junior synonym of Lactococcus garvieae, a causative agent of septicemia and meningoencephalitis in fish. Curr Microbiol. 1996;32:85–88. doi: 10.1007/s002849900015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elliott J A, Collins M D, Pigott N E, Facklam R R. Differentiation of Lactococcus lactis and Lactococcus garvieae from humans by comparison of whole-cell protein patterns. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;20:2731–2734. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.12.2731-2734.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott J A, Facklam R R. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Lactococcus lactis and Lactococcus garvieae and a proposed method to discriminate between them. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1296–1298. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1296-1298.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foo J T W, Ho B, Lam T J. Mass mortality in Siganus canaliculatus due to streptococcal infection. Aquaculture. 1985;49:185–195. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grimont F, Grimont P A D. Ribosomal nucleic acid gene restriction patterns as potential taxonomic tools. Ann Inst Pasteur Microbiol. 1986;137B:165–175. doi: 10.1016/s0769-2609(86)80105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimont P A D. Use of DNA reassociation in bacterial classification. Can J Bacteriol. 1988;34:541–546. doi: 10.1139/m88-092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holt J G, Krieg N R, Sneath P H A, Williams S T, editors. Bergey’s manual of determinative bacteriology. 9th ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1994. pp. 527–558. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kusuda K, Kawai K, Salati F, Banner C R, Freyer J L. Enterococcus seriolicida sp. nov., a fish pathogen. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1991;41:406–409. doi: 10.1099/00207713-41-3-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lancefield R C. A serological differentiation of human and other groups of hemolytic streptococci. J Exp Med. 1933;57:406–409. doi: 10.1084/jem.57.4.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lancefield R C. A microprecipitating technique for classifying hemolytic streptococci and improved methods for producing antisera. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1938;38:473–481. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCarthy M, Lancefield R C. Variation in the group-specific carbohydrate of group A streptococci. J Exp Med. 1935;102:11–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.102.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michel C, Nougaryede P, Eldar A, Sochon A, de Kinkelin P. Vagococcus salmoninarum, a bacterium of pathological significance in rainbow trout (Onchorynchus mykiss) farming. Dis Aquat Org. 1997;30:199–208. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray B B. The life and times of the enterococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:46–65. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nieto J M, Devesa S, Quiroga A, Toranzo A E. Pathology of Enterococcus sp. in farmed turbot, Scophthalmus maximus L. J Fish Dis. 1995;18:21–30. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ouchterlony O. Diffusion-in-gel methods for immunological analysis. Prog Allergy. 1958;5:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romalde J L, Magarinos B, Nunez S, Barja J L, Toranzo A E. Host range susceptibility of Enterococcus sp. strains isolated from diseased turbot: possible routes of infection. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:607–611. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.607-611.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stull T L, Lipuma J J, Edlind T D. A broad-spectrum probe for molecular epidemiology of bacteria: ribosomal RNA. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:280–286. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wayne L G, Brenner D J, Colwell R R, Grimont P A D, Kandler O, Krichevsky M I, Moore L H, Moore W E C, Murray R G E, Stackebrandt E, Starr M P, Truper G H. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Reconciliation of Approaches to Bacterial Systematics. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1987;37:463–464. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams A M, Freyer J L, Collins M D. Lactococcus piscium sp. nov., a new Lactococcus species from salmonid fish. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;68:109–114. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90134-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zlotkin A, Eldar A, Ghittino C, Bercovier H. Identification of Lactococcus garvieae by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:983–985. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.983-985.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]