Abstract

Context

Acetaminophen (APAP, paracetamol) is widely used by pregnant women. Although long considered safe, growing evidence indicates that APAP is an endocrine disruptor since in utero exposure may be associated with a higher risk of male genital tract abnormalities. In rodents, fetal exposure has long-term effects on the reproductive function of female offspring. Human studies have also suggested harmful APAP exposure effects.

Objective

Given that disruption of fetal ovarian development may impact women’s reproductive health, we investigated the effects of APAP on fetal human ovaries in culture.

Design and Setting

Human ovarian fragments from 284 fetuses aged 7 to 12 developmental weeks (DW) were cultivated ex vivo for 7 days in the presence of human-relevant concentrations of APAP (10−8 to 10−3 M) or vehicle control.

Main Outcome Measures

Outcomes included examination of postculture tissue morphology, cell viability, apoptosis, and quantification of hormones, APAP, and APAP metabolites in conditioned culture media.

Results

APAP reduced the total cell number specifically in 10- to 12-DW ovaries, induced cell death, and decreased KI67-positive cell density independently of fetal age. APAP targeted subpopulations of germ cells and disrupted human fetal ovarian steroidogenesis, without affecting prostaglandin or inhibin B production. Human fetal ovaries were able to metabolize APAP.

Conclusions

Our data indicate that APAP can impact first trimester human fetal ovarian development, especially during a 10- to 12-DW window of heightened sensitivity. Overall, APAP behaves as an endocrine disruptor in the fetal human ovary.

Keywords: N-acetyl-p-aminophenol, paracetamol, human fetal ovary, hormones, metabolites

Acetaminophen (N-acetyl-p-aminophenol, APAP, paracetamol) is 1 of the most widely used over-the-counter mild analgesics, with more than half of pregnant women reporting its consumption (1, 2). Although considered safe, its innocuousness during pregnancy is now questioned regarding newborn health (1-4).

Several experimental studies have demonstrated the endocrine disrupting capacity of APAP in fetal testis (5-8). Although studies showed that elements of the steroidogenic pathway are present in the human fetal ovary (hFO) (9-12) and that it displays endocrine activity (13), the effect of APAP on fetal ovarian endocrine capability has not been reported.

During fetal life, female germ cells go through crucial morphogenetic events, starting with migration while actively proliferating, followed by sex differentiation and commitment to meiosis, culminating with primordial follicles assembly (14). Fetal germ cell development—and, more broadly, ovarian development—influences later reproductive lifespan since it establishes a dynamic but finite stockpile of follicles; the ovarian reserve. Studies in rodents demonstrate that APAP reduces both fetal ovarian germ cell numbers and total adult follicle numbers, resulting in reduced fertility (15-17). Its impact on ovarian development in offspring also suggests intergenerational effects through epigenetic germline alterations (15, 18). To the best of our knowledge, only 1 study on the effect of APAP on hFO has been reported to date, and it demonstrated that, ex vivo, APAP may interfere with germ cell development (18).

Metabolic processing effectively deactivates drugs while facilitating their elimination, although it can generate toxic metabolites for some drugs, including APAP (19). Although the liver is the key organ for drug metabolism, other organs have metabolizing activities (20). Fetal exposure to xenobiotics is mainly modulated by the maternal and placental metabolic capacities (21). The human fetal liver also expresses several key enzymes involved in phase I and phase II metabolism (22, 23) and is able to biotransform xenobiotics (24-26).

We aimed to investigate the effect of APAP on first trimester hFO development by using an established ex vivo culture model (27). We show that APAP interferes with first trimester hFO development, altering the viability of a germ cell subpopulation. We also found that APAP disrupts hFO steroidogenic capability without perturbing prostaglandin and inhibin B production, suggesting specific endocrine disruption. Finally, we show, for the first time, that the hFO can metabolize APAP into an inactivated sulfated conjugate.

Materials and Methods

Collection of Human Fetal Ovaries

Two hundred eighty-four first trimester human fetuses [7-12 developmental weeks (DW)] were obtained from legally induced terminations of pregnancy performed in Rennes University Hospital. Tissues were collected following women’s written consent, in accordance with legal procedures agreed by the national agency for biomedical research (recommendation #PFS09-011; Agence de la Biomédecine) and the local ethics committee of Rennes Hospital (notification #11-48). Termination of pregnancy was induced using a standard combined mifepristone and misoprostol protocol, followed by aspiration. The whole aspiration material was collected in a sealed sterile pouch, rapidly stored at 4°C, and kept cold at all times. Ovaries were isolated under a binocular microscope (Olympus SZX7, Lille, France) within 2 hours after sample collection and immediately placed into ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. Gestational age, previously determined by ultrasound, was further confirmed by measurement of foot length. Ovaries were recovered from aspiration products using a binocular microscope (Olympus SZX7, Lille, France) and immediately placed in cold phosphate-buffered saline.

Ex Vivo Culture

Recovered ovaries were processed as previously described (27). Briefly, to ensure the viability of the tissue in terms of nutrients accessibility all along the experimental procedure, each ovary was cut into 1 mm3 size explants. Ovaries from fetuses younger than 10 DW were cultured in 2 separate wells, 1 ovary under control (vehicle) condition and the other exposed to APAP. Ovaries from 1-DW-old fetuses onward were cut into 1 mm3 pieces allowing more than 2 conditions. The same number of ovarian explants (3-4, depending on the endpoint) was used for each condition. One mm3 ovary pieces were placed into cell culture inserts (0.4 μM pores, Millipore #PICM01250) in wells filled with 400 μL of phenol red-free Medium 199 (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Cergy-Pontoise, France) supplemented with 50 μg/mL gentamycin, 2.5 μg/mL fungizone (Sigma Aldrich Chemicals, Saint-Quentin Fallavier, France), and 1 g/L insulin, 0.55 g/L transferrin, and 0.67 mg/l sodium selenite (ITS, Corning, Fisher Scientific). Cultures were incubated at 37°C for 7 days with 5% CO2 and humidity. Explants were immediately exposed to either vehicle at a final concentration of 0.1% v/v [dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)] or APAP (Sigma Aldrich Chemicals, Cas #103-90-2). Commonly used therapeutic doses of APAP lead to 100 to 200 µM APAP in the plasma (28, 29), and APAP freely crosses the placenta (30). APAP concentrations used in this study ranged from 0.01 to 100 µM to assess potential dose-response effects, and concentration of 1000 µM was used to explore toxic effects. Upon replacement, culture media were snap-frozen and stored at −80°C for further analyses.

Single Cell Dissociation and Flow Cytometry

Single cell suspensions from explants were obtained with a 2-step sequential enzymatic digestion procedure (27). Live cells were counted on a Malassez hematocytometer using Trypan Blue. When ovaries were cultivated in a single condition, the total number of cells resulted from the live cell counts. Alternately, the total number of cells per condition was calculated from the number of cells counted after dissociation and the ratio of fragments per condition to the initial number of fragments per ovary. Apoptotic cells were labeled with FITC Annexin-V (BD pharmingen #556419) following the manufacturer’s recommendations, coupled to necrotic nucleus staining with 3 μg/mL 7-aminoactinomycin D (FluoProbes, Interchim #132303) (27). A subpopulation of germ cells was identified through plasma membrane M2A labeling (Table 1). Cell death and germ cell dynamics were evaluated by acquiring a minimum of 20 000 events using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using CellQuest software. The number of M2A-positive germ cells was calculated from the percentage of positive cells and the total cell number.

Table 1.

Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry staining

| Target protein | Primary antibody reference and RRID | Application | Antigen retrieval | Primary antibody dilution | Secondary antibody reference | Secondary antibody dilution | Signal enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleaved caspase 3 | Cell Signaling Tech. #9661 (AB_2341188; https://antibodyregistry.org/search?q=AB_2341188) | IHC | Tris-EDTA, 40 minutes, 80°C | 1:150 | Goat Anti-rabbit Biotin Conjugated Dako #E0432 | 1:500 | ABC |

| CYP11A | Sigma Aldrich #HPA016436 (AB_1847423; https://antibodyregistry.org/search.php?q=AB_1847423) | IHC | Citrate, 40 minutes, 80°C | 1:150 | Dual Link Dako #K4063 | RTU | |

| CYP17A1 | Abcam #ab48019 (AB_869326; https://antibodyregistry.org/search?q=AB_869326) | IHC | Citrate, 40 minutes, 80°C | 1:200 | Rabbit Anti-goat Biotin Conjugated Dako #E0466 | 1:500 | ABC |

| KI67 | Dako #M7240 (AB_2142367; https://antibodyregistry.org/search?q=AB_2142367) | IHC | Citrate, 40 minutes, 80°C | 1:100 | Dual Link Dako #K4063 | RTU | |

| LIN28 | Abcam #ab46020 (AB_776033; https://antibodyregistry.org/search?q=AB_776033) | IHC | Citrate, 40 minutes, 80°C | 1:300 | Dual Link Dako #K4063 | RTU | |

| M2A | Abcam #ab77854 (AB_1566117; https://antibodyregistry.org/search?q=AB_1566117) | FC | 1:200 | R-Phycoerythrin Coupled anti-Mouse Immunoglobin G (H + L) Jackson ImmunoResearch # 715-116-150 | 1:200 | ||

| SYCP3 | Sigma Aldrich #HPA039635 (AB_2676607; https://antibodyregistry.org/search?q=AB_2676607) | IHC | Citrate, 40 minutes, 80°C | 1:250 | Dual Link Dako #K4063 | RTU | |

| SULT1E1 | Sigma #HPA028728 (AB_10601894; https://antibodyregistry.org/search?q=AB_10601894) | IHC | Citrate, 40 minutes, 80°C | 1:250 | Goat Anti-rabbit Biotin Conjugated Dako #E0432 | 1:500 | ABC |

10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA buffer, pH 9 (Tris-EDTA), or 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6 (Citrate).

Abbreviations: ABC, avidin-biotin complex (VECTASTAIN® Elite ABC-HRP Kit, Vector Labs); FC, Flow cytometry; IHC, immunohistochemistry; RTU: ready to use.

Immunohistochemistry, Stereology, and In Situ Hybridization

Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described (27) on Bouin’s fixed, paraffin-embedded ovaries using antibodies as detailed in Table 1. Stained sections were examined and photographed with a light microscope (Olympus BX51). A mean of 6.15 ± 0.14 photos at 40× magnification were taken per condition in areas containing germ cells (at least 2 photos per explant), with a mean area of 191 303 ± 4366 µm2. Same photos were used for proliferation and germ cell counts. ImageJ software (US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to perform the cell counting and surface measurement. Proliferating cells were reported as the percentage of KI67-positive cells in a population of KI67-negative cells. Germ cells were identified based on their morphology and size (either <9 µm or ≥9 µm) (31, 32) calculated with ImageJ. Density of germ cells was the number of germ cells per µm2. In situ hybridization was performed using RNAscope 2.5 (Advanced Cell Diagnostics) on paraformaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded ovaries according to the manufacturer’s instructions with a minor modification (ie, the fifth amplification step was increased from 30 to 60 minutes) (33). Probes are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Probes used for RNAscope

| Target genes | RNAscope probes | Cat no. |

|---|---|---|

| ESR1 | RNAscope® Probe- Hs-ESR1 | 310301 |

| ESR2 | RNAscope® Probe- Hs-ESR2 | 470151 |

| GPER | RNAscope® Probe- Hs-GPER | 553361 |

| CYP19A1 | RNAscope® Probe- Hs-CYP19A1 | 489941 |

Prostaglandin Measurements

Prostaglandin estradiol (PGE2) and prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) levels were measured in culture media of ovarian explants after 1 day of exposure using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (PGE2 EIA Kit: Monoclonal, #514010; PGD2: MOX ELISA Kit, #512011; Cayman Chemical Company Ann Arbor, MI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each sample was diluted 1:2 in sample enzyme immunoassay diluent solution prior to reactions and assayed in duplicate. Intra- and interassay coefficients of variance were 3.7% to 30.4% and 6.4% to 35% for PGE2 and PGD2, respectively.

Measurements of APAP and Its Main Metabolites

APAP, APAP-β-D-glucuronide (APAP-GLU) and APAP-sulfate (APAP-SUL), within culture media collected 24 and 72 hours after culture onset, were simultaneously quantified by liquid chromatography coupled-high resolution mass spectrometer. Briefly, an 8-calibration point range of APAP, APAP-GLU, and APAP-SUL (Sigma Aldrich; 0-5 mg/L) was prepared using culture medium (ie, M199 with ITS) diluted with methanol (Fisher Scientific UK, Loughborough, Leicestershire, UK). Then, 25 µL of medium diluted 5:18 in methanol and standard solutions were enriched with 100 ng of APAP-D4 (Sigma Aldrich) as an internal standard. Following homogenization, samples were incubated at 4°C for 15 minutes prior to centrifugation (10 minutes, 4°C, 3000 g). Target compounds were ionized by using an HESI-II ion source for the electrospray ionization. Analytes were separated by using an Accela Pump (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a Thermo Fisher Hypersil Gold C18 column (3.0 mm, 2.1, 100 mm) as previously described (34). Data were acquired in targeted single ion monitoring in a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive mass spectrometer (San Jose, CA, USA). The limits of quantification of APAP and APAP-SUL were 0.17 µM and 0.105 µM, respectively (35).

Steroid Measurement

Dihydrotestosterone, testosterone, E2, Δ4-androstenedione, progesterone, 17 hydroxy-progesterone (17OHP), and pregnenolone were assayed simultaneously by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry as previously described (36, 37) with minor modifications (available upon request). Saline water/twice charcoal dextran stripped aged female rabbit serum (1/1, v/v) was used as the matrix for calibrators and quality control (QC) standards. Accuracy, target ions, corresponding deuterated internal control, range of detection, low limits of quantification, and intra- and interassay coefficients of variance of the QC are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

GC-MS fetal ovarian cell supernatant analytical control validation

| Accuracy, % | Analytes | Target (GC-MS) or precursor ion analyte (GC-MS/MS)/IS (m/z) | Range, pg/mL | Mean (23 runs; pg/mL) intra- and interassay CVs, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLOQ mean intra- and Interassay CVs | Low QC mean intra- and Interassay CVs | Middle QC mean intra- and interassay CVs | High QC mean intra- and interassay CVs | ||||

| 95-109 | T | 482/ 485 | 3.9-944 | 3.6 | 153.7 | 310.4 | 621.5 |

| 15.1-18.8 | 3.7-5.6 | 3.6-4.9 | 3.4-5.1 | ||||

| 94-108 | DHT | 484/ 487 | 1.4-333 | 1.7 | 30.8 | 62.5 | 124.4 |

| 15.7-19.9 | 4.0-5.8 | 3.8-5.6 | 3.3-5.2 | ||||

| 94-107 | E2 | 660/ 664 | 0.2-56.0 | 0.22 | 2.87 | 6.07 | 12.88 |

| 17.3-19.8 | 4.3-5.7 | 3.6-5.2 | 3.3-5.4 | ||||

| 89-113 | Preg | 298/ 302 | 25-6000 | 5.8 | 14.4 | 77.9 | 198.9 |

| 16.1-19.4 | 4.3-6.7 | 4.1-5.3 | 4.6-5.8 | ||||

| 93-110 | 4-dione | 482/ 488 | 11.7-2833 | 1.6 | 9.8 | 48.1 | 198.5 |

| 16.3-19.2 | 4.4-5.2 | 3.5-5.3 | 3.5-5.9 | ||||

| 94-105 | Prog | 510/ 518 | 16.5-4000 | 16.7 | 63.4 | 125.8 | 251.1 |

| 15.9-19.5 | 3.3-5.3 | 3.2-5.3 | 3.0-5.5 | ||||

| 88-116 | 17OHP | 465/ 469 | 33-8000 | 36.3 | 64.6 | 126.3 | 254.5 |

| 15.8-19.7 | 4.7-8.5 | 4.1-6.1 | 4.4-7.2 |

Abbreviations: 17OHP, 17 hydroxy-progesterone; 4-dione, Δ4-androstenedione; CV, coefficient of variance; DHT, dihydrotestosterone; E2, estradiol; LLOQ, low limit of quantification; Preg, pregnenolone; Prog, progesterone; QC, quality control; T, testosterone.

Statistical Analysis

Distributions of cell numbers, percentages, and densities in response to different APAP concentrations were compared using mixed regression models to account for the testing of multiple conditions for a same fetus. The fetus was considered as a random effect and the treatment group (DMSO, APAP at different concentrations) as a fixed effect. The global effect of the treatment group was tested with a Fisher’s test and comparison of each treatment effect against the DMSO condition used a Student’s t test. Linear models were directly applied or after log-transformation when necessary. A negative binomial regression model was used for the number of germ cells. Fetal age (<10 vs ≥10 DW) and its interaction with the treatment group were included as fixed effects in the models. As interactions appeared significant, we stratified all the analyses according to the age group. Data analyses were computed using the SAS software (SAS/STAT version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc). For hormone measurements, APAP-exposed values were normalized by the corresponding DMSO ones. Global analysis of the effects on ratios was analyzed thanks to a nonparametric Kruskall-Wallis test, followed by Mann-Whitney rank sum test for comparisons between control and APAP-treated samples with the GraphPad Prism 5 software package (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistically significant post hoc tests are indicated if the P-value < 0.05, < 0.01, or < 0.001.

RESULTS

APAP Interferes With Ovarian Development

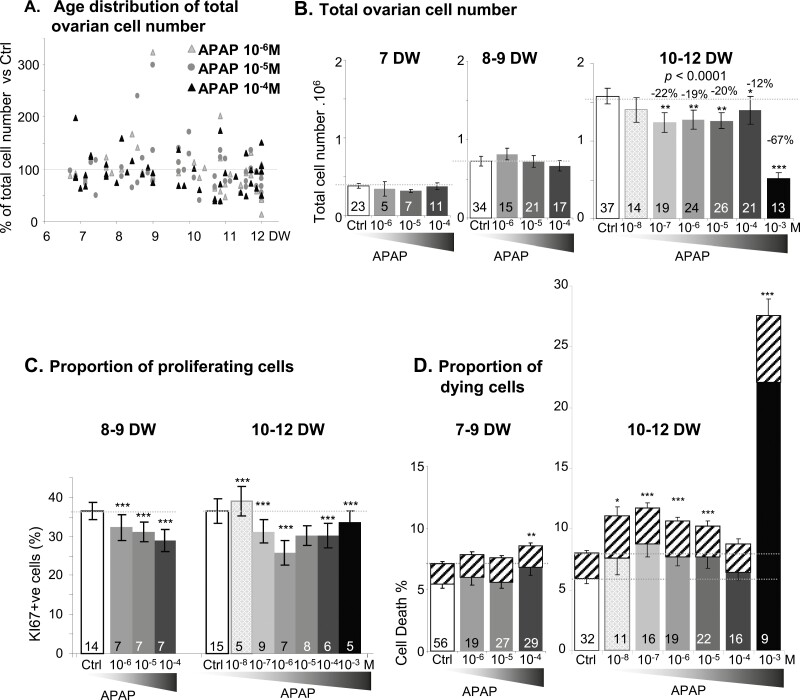

Overall, exposure of 7- to 12-DW ovarian explants to APAP at various concentrations for 7 days affected the total ovarian cell number differently depending on the age of the ovaries (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1A). With the exception of 10−8 M, all APAP concentrations significantly decreased overall cell numbers in10- to 12-DW explants (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1B), with a dramatic decline of 67% (P < 0.0001) at 10−3 M APAP (Fig. 1B). In similar exposure conditions, we scored KI67-positive and -negative cells on immunostained sections of 8- to 12-DW ovarian explants. All tested APAP concentrations significantly decreased the percentage of proliferating KI67-positive cells, except 10−5 M in 10- to 12-DW explants (Fig. 1C). The percentage of dead cells according to sample age and culture condition was then determined by Annexin-V-FITC/7AAD labeling and flow cytometry (Fig. 1D). In 7- to 9-DW ovarian explants, only exposure to 10−4 M APAP induced a significant increase of the dead cell ratio, whereas in 10- to 12-DW explants, all APAP concentrations except 10−4 M, increased (P < 0.05) both apoptosis and necrosis (Table 4), with again an especially pronounced effect of 10−3 M APAP (P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Effects of acetaminophen (APAP) on human fetal ovary growth. (A) Fetal age distribution of total ovarian cell number after 7 days of exposure to 10−6, 10−5, and 10−4 M APAP normalized to control values as a function of age [developmental weeks (DW)] (n = 91). (B) Quantification of total viable cell number per ovary following 7 days of exposure to either control vehicle (Ctrl, white bars) or APAP at 10−8 to 10−3M (gray to black bars) in fetuses at 7, 8 to 9, and 10 to 12 DW. Cell counts were performed with Trypan Blue exclusion staining of 7- to 12-DW fetal explants and are expressed as 106 cells per ovary. (C) Percentage of KI67-positive cells relative to the total number of cells assessed on immunostained sections 7 days after exposure to either control vehicle (Ctrl, white bars) or APAP at 10−8 to 10–3M (gray to black bars) at 8 to 9 DW and 10 to 12 DW. (D) Percentage of apoptotic (solid bars) and necrotic cells (hatched bars) after 7 days of exposure to either control vehicle (Ctrl, white bars) or APAP at 10−8 to 10−3M (gray to black bars) assessed with Annexin-V vs 7-aminoactinomycin D labeling of fetal ovarian explants at 7 to 9 DW and 10 to 12 DW. Data are represented as mean ± SE of the mean. Mixed linear models with fetus as a random fetus effect were performed for cell numbers, densities, and percentages. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, from the t-test comparisons with the control condition. The number of samples tested per condition is indicated at the bottom of each bar.

Table 4.

Comparison of cell death, apoptosis and necrosis occurrence under different exposure concentrations against control condition, stratified by age

| Age (DW) | Cell death type | 10−8M | 10−7M | 10−6M (n = 19) | 10−5M (n = 27) | 10−4M (n = 29) | 10−3M (0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <10 | Cell death | 0.3614 | 0.2662 | 0.0081 | |||

| Apoptosis | 0.7866 | 0.6258 | 0.0154 | ||||

| Necrosis | 0.9383 | 0.4202 | 0.0178 | ||||

| 10 −8 M (n = 14) | 10 −7 M (n = 19) | 10 −6 M (n = 22) | 10 −5 M (n = 25) | 10 −4 M (n = 19) | 10 −3 M (n = 12) | ||

| ≥10 | Cell death | 0.0200 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.1 | <0.0001 |

| Apoptosis | 0.6102 | 0.0045 | 0.0019 | 0.0139 | 0.4103 | <0.0001 | |

| Necrosis | 0.3147 | 0.0019 | 0.0007 | 0.0058 | 0.1482 | <0.0001 |

P-values derived from t-test pairwise comparisons of each exposure concentration against the control condition are indicated. The number of samples per condition (n) is indicated in parenthesis in the concentration row.

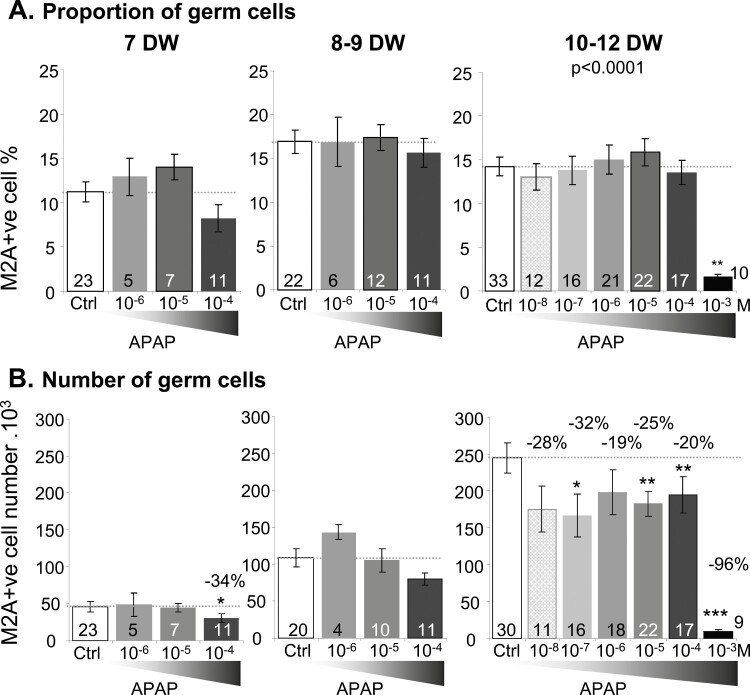

APAP Targets a Subpopulation of Germ Cells

The percentage of M2A-positive germ cells reported to the total cell number remained stable with all the APAP concentrations tested, apart from 10−3 M, which on 10- to 12-DW explants had a massive impact (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A). However, the number of M2A-positive cells significantly decreased in 10- to 12-DW ovarian explants exposed to APAP concentrations as low as 10−7M (P < 0.05). In 7-DW explants, a loss of M2A-positive cell number was observed with 10−4 M APAP exposure (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Effects of acetaminophen (APAP) on germ cells. Percentage (A) and number (B) of M2A-positive germ cells was assessed by flow cytometry following 7 days of exposure to either vehicle (–, white bar) or APAP 10−8 to 10−3M (gray to black bars). Total M2A-germ cells number per ovary is expressed as 103 germ cells per ovary at 7, 8 to 9, and 10 to 12 DW. Data are represented as mean ± SE of the mean. Mixed linear models with fetus as a random effect were performed for cell numbers, densities, and percentages. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, from the t-test comparisons with the control condition. The number of samples tested per condition is indicated at the bottom of each bar.

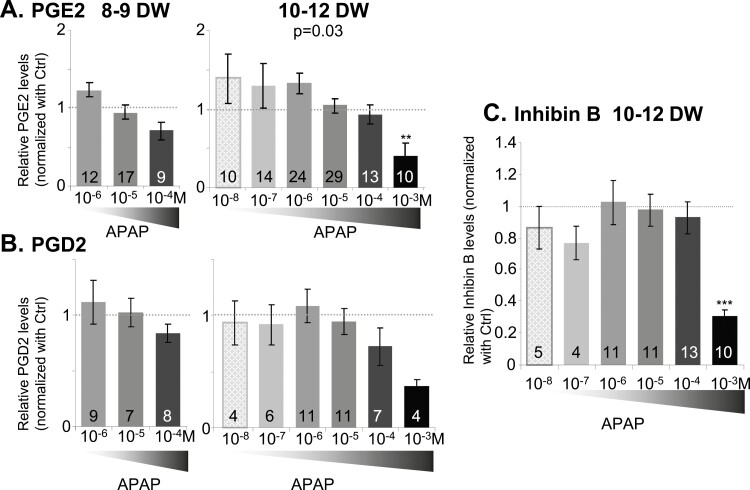

Immunostaining revealed a progressive loss of immature LIN28-positive cells with increasing concentrations of APAP (drastic depletion at 10−3 M) but only a slight reduction in premeiotic SYCP3-positive cell numbers (Fig. 3A-B). We further quantified germ cell numbers based on their diameter (<9 µm and ≥9 µm) and chromatin compaction on histological sections. Compared to 10- to 12-DW explants, where the density of <9 µm germ cells was noticeably reduced by APAP at concentrations as low as 10−8 M, a weak but statistically significant loss of the smaller germ cells was detectable after exposure to 10−6 and 10−4 M APAP in 8- to 9-DW explants. Regarding the larger germ cells (≥9 µm) counts, APAP had little impact, except for the 10−3 M concentration in 10- to 12-DW explants (Fig. 3C). The percentage of KI67-positive germ cells, whether <9 or ≥9 µm, remained steady regardless of the APAP exposure concentration or fetal age (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Differential effects of acetaminophen (APAP) on germ cell populations. (A and B) Representative immunostaining of immature oogonia (A) and premeiotic germ cells (B) with antibodies directed against LIN28 and SYCP3, respectively, after 7 day of exposure of 11.6 DW ovarian explants to control vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide) or different concentrations of APAP (10−6-10−3M) at 8 to 9 DW and 10 to 12 DW. Immunoreactive germ cells appear brown (3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride staining), and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Scale bar = 100 µm. (C) Density of germ cells (number of cells per µm2) in 8- to 9-DW and 10- to 12-DW ovarian explants exposed to 10−8 to 10−3M APAP for 7 days. Cells were quantified as a function of their size (<9 µm and ≥9µm). (D) The percentage of KI67-positive germ cells for each category of germ cells was quantified on immunostained sections as a function of KI67 immunoreactivity and cell size (<9 µm and ≥ 9 µm). Data are represented as mean ± SE of the mean. Mixed linear and negative binomial models with fetus as a random effect were performed. *P < 0.05;***P < 0.001, from the t-test comparisons with the control condition, respectively. The number of samples tested per condition is indicated at the bottom of each bar.

APAP Dysregulates Sex Steroid Production Without Altering PGE2 and PGD2 Production by Human Fetal Ovary

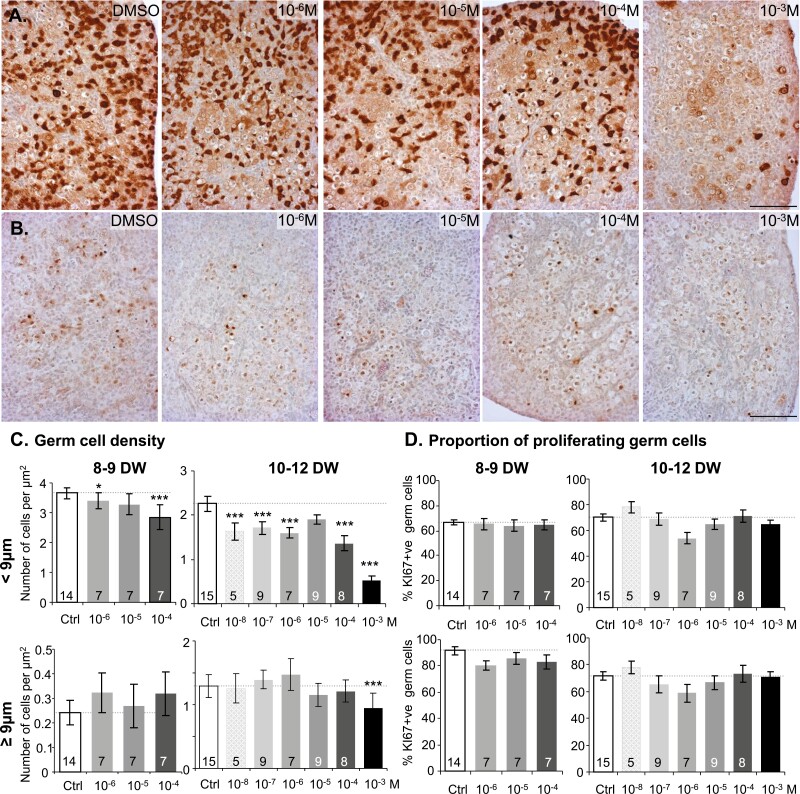

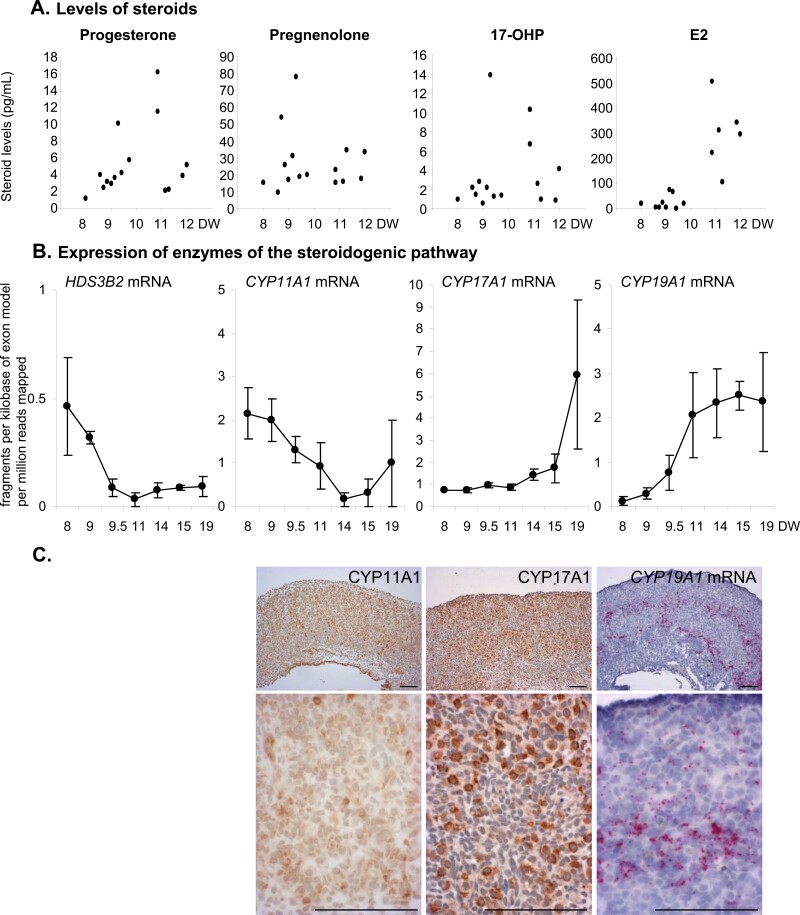

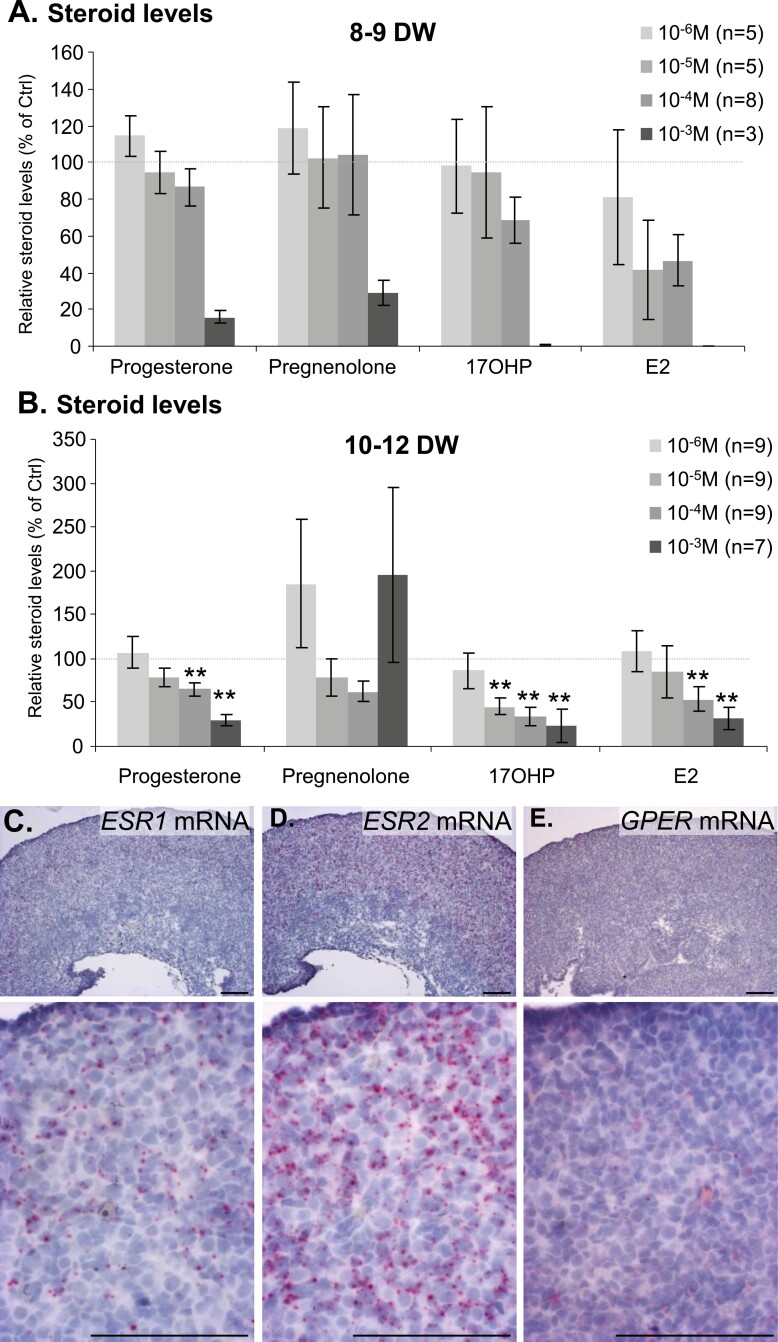

PGD2 and PGE2 and inhibin B (Fig. 4), as well as sex steroid (Figs. 5 and 6), levels were measured in media after either 24-hour or 7-day culture. Neither prostaglandins nor inhibin B production by hFO were significantly altered by APAP except after exposure of 10- to 12-DW ovarian explants to the toxic concentration of 10−3 M APAP (PGE2 P < 0.001; inhibin B P < 0.01). Dihydrotestosterone, testosterone, and Δ4-androstenedione levels were below the limit of quantification, while progesterone, pregnenolone, 17OHP, and E2 were measurable in all samples, consistent with the expression of steroidogenesis pathway enzymes (Fig. 5). Only exposure to 10−3 M APAP drastically decreased levels of these steroids in 8- to 9-DW samples while in 10- to 12-DW samples, both 10−4 and 10−3 M APAP exposures significantly decreased progesterone and E2 levels and at concentrations as low as 10−5 M, lowered 17OHP levels (Fig. 6). To evaluate whether E2 may have a local impact, we analyzed the expression of estrogen receptors using in situ hybridization within first trimester human fetal ovaries. While all 3 receptors were expressed, the level of ESR2 was consistently higher than that of ESR1 and GPER (Fig. 6C-6E).

Figure 4.

Effects of acetaminophen (APAP) on the production of prostaglandin and inhibin B by human fetal ovaries. (A and B) Measurement of prostaglandin E2 (A) and prostaglandin D2 levels (B) normalized with control after 24 hours of exposure of 8- to 9-DW and 10- to 12-DW samples to either vehicle (–, white bars) or APAP at 10–8 to 10−3 M (gray to black bars). (C) Measurement of inhibin B levels normalized with control after 24 hours of exposure to either vehicle (–, white bars) or APAP at 10−8 to 1−3M (gray to black bars) produced by 10- to 12-DW ovarian explants. Data are represented as mean ± SE of the mean. The P-value of the Kruskall-Wallis test is indicated on the top, **P-value < 0.01, Wilcoxon post hoc test compared to control. The number of samples per condition is indicated at the bottom of each bar.

Figure 5.

Steroidogenesis machinery and production in human fetal ovaries. (A) Steroid levels measured by mass spectrometry as a function of developmental weeks (DW). Each dot represents the measurement of steroid levels in the medium of human fetal explants from 1 donor cultivated for 7 days in control conditions. (B) Expression of transcripts encoding enzymes of the steroidogenic pathway, namely the hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase HSD3B2, and the cytochrome P450 CYP11A1, CYP17A1, and CYP19A1 (aromatase) were evaluated in human fetal ovaries by RNA sequencing (38). Data are expressed as means ± SE of the mean of fragments per kilobase of exon model per million reads mapped (fpkm). (C) Representative low magnification (upper panel) and high magnification (lower panels) of in situ localization of CYP11A1 and CYP17A1 proteins and CYP19A1 messenger RNA in a 11.8-DW-old ovary, using immunohistochemistry and RNAscope, respectively. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Figure 6.

Effects of acetaminophen (APAP) on human fetal ovarian sex steroids production. (A and B) Amounts of progesterone, pregnenolone, 17 hydroxyprogesterone (17OHP), and estradiol (E2) produced by APAP-exposed explants, normalized with amounts produced by control explants, after 7 days of exposure. Data from 8- to 9-DW (A) and 10- to 12-DW ovarian explants (B) are shown for normalized values of APAP at 10−6 to 10−3M (gray to black bars). Data are represented as mean ± SE of the mean. **P-value < 0.01, Wilcoxon post hoc test compared to control. The number of individuals per condition is indicated in the exposure key. (C-E) Representative in situ hybridization of nuclear estrogen receptors ESR1 (C), ESR2 (D), and the membrane estrogen receptor GPER messenger RNAs (E) in a 13.6-DW human fetal ovary. Lower panel photos show higher magnifications. Scale bar: 100 µm.

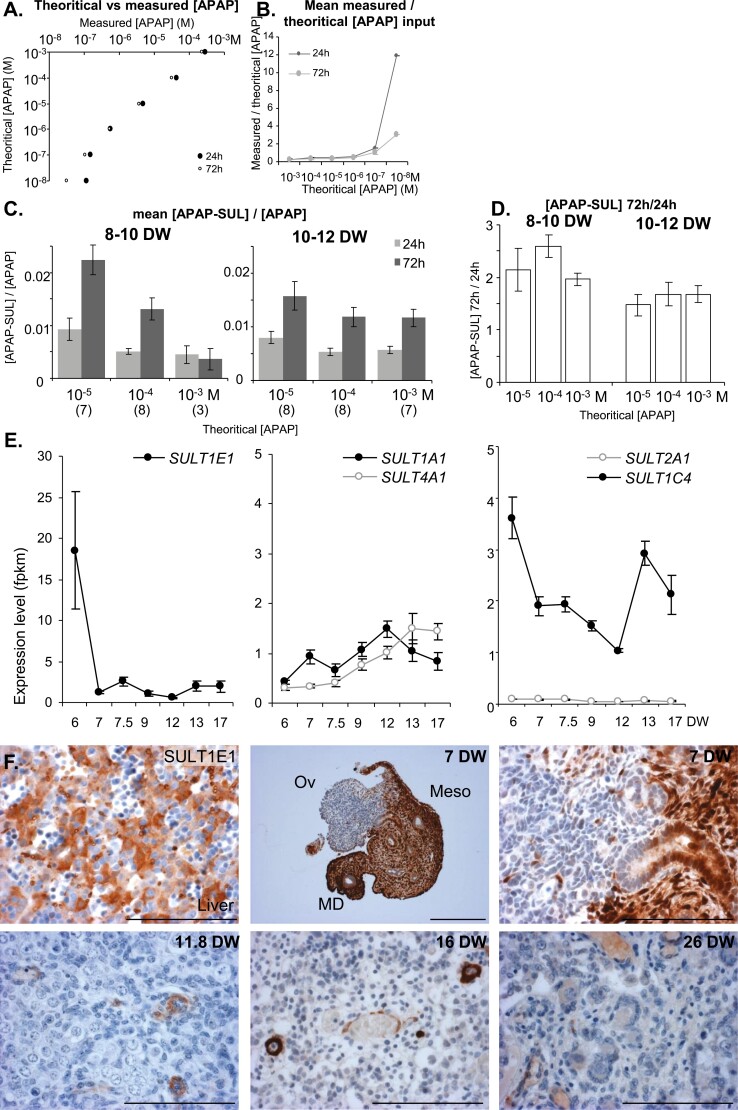

Human Fetal Ovary Metabolizes APAP Mainly Into APAP-SUL

Using liquid chromatography coupled-high resolution mass spectrometer, we measured APAP, as well as its main glucuronide (APAP-GLU) and sulfate (APAP-SUL) metabolites in culture media collected 24 and 72 hours after culture onset (Fig. 7). No APAP was detected in vehicle (DMSO)-exposed culture media (data not shown). A consistent linear relationship between measured and expected (theoretical) APAP levels was evident in both 24- and 72-hour culture media, except for the 10−8 M concentration that was below the limit of quantification (Fig. 7A and 7B). Regardless of the APAP concentration, exposure time, and fetal age, the only metabolite found within culture media was APAP-SUL, APAP-GLU being below the limit of detection. The amount of APAP-SUL produced was similar for ovaries from 8- to 10-DW or 10- to 12-DW fetuses and increased linearly with the concentration of APAP (data not shown). The sulfation rates (ie, the mean ratios between measured levels of APAP-SUL and APAP) ranged from 0.5% to 2% depending on the concentration and the exposure time (Fig. 7C). This rate after 2 consecutive days of culture (72 hours) was usually twice as high as after 24 hours (Fig. 7D). Our bulk RNAseq data (38) indicates that several sulfotransferases, including SULT1E1, SULT1A1, SULT4A1, and SULT1C4, are expressed in hFO (Fig. 7E). Immunohistochemistry for SULT1E1 revealed immunoreactivity in endothelial cells as well as in currently unidentified structures within hFO, strong immunoreactivity in the mesonephros and in human fetal liver, which were used as positive controls (Fig. 7F).

Figure 7.

Metabolization of acetaminophen (APAP) by the human fetal ovary. (A and B) APAP availability in culture media. Relationship between theoretical and measured APAP levels (A) and ratios between measured and theoretical APAP levels (B) were determined for each APAP concentration after 24 hours of culture as well as after an additional 48 hours of culture (72 hours). (C) APAP sulfation rates [measured (APAP-SUL)/(APAP)] in 8- to 10-DW and 10- to 12-DW ovaries for each initial theoretical APAP concentration after 24 hours of culture as well as during the following 48 hours (72 hours). The number of samples per condition is indicated in parentheses below the x-axis. (D) Ratios between measured (APAP-SUL) levels produced by 8- to 10-DW and 10- and 1-DW ovaries after 24 hours and the subsequent 48 hours (72 hours) of exposure were calculated for each initial APAP concentration. The number of samples per condition is the same as in (C). Data are represented as mean ± SE of the mean. (E) SUL1E1, 1A1, 2A1, 4A1 1C4 transcript levels in human fetal ovary as a function of developmental age (38). Data are expressed as fragments per kilobase of exon model per million reads mapped (fpkm). Note that the y-axis scale for SULT1E1 is 6× higher than for the other SULTs. (F) Immunostaining of SULT1E1 using the age-matched fetal liver as a positive control and in uncultured ovaries of 11.8, 16, and 26 DW. SULT1E1-positive cells appear brown (3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride staining), and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Scale bar = 100 µm. Abbreviations: Ov, ovary; Meso, mesonephros; MD, Müllerian duct.

Discussion

Given the wide use of APAP by pregnant women and interspecies variability with rodent models, we took advantage of a previously described ex vivo model of hFO culture (27) to investigate whether APAP interferes with development of the first trimester hFO. Our study shows that concentrations equivalent to or below peak therapeutic APAP plasma levels (28, 29) interfere with both development and steroidogenesis of the hFO, despite the ovary’s innate metabolizing capability.

Ovarian development relies on growth and differentiation, the former sustained by proliferation of both the somatic and germ cell lineages (39), until oogonia commit to meiosis. In line with a previous study from our group (27), we report that the organotypic culture system allows for ovarian development. Under these conditions, APAP did not globally alter the total number of cells in 7- to 9-DW ovaries but reduced the percentage of proliferative KI67-positive cells while moderately inducing apoptosis at 10−4 M. This apparent discrepancy could be attributed to marginal effects observed for these parameters. In contrast, in 10- to 12-DW ovaries, the loss of total cells was consistently accompanied by a reduction of the percentage of KI67-positive cells and an increased percentage of dying cells. The hindering effect of APAP observed on cell proliferation is consistent with previous reports (40, 41). Our data define a possible window of sensitivity of human fetal ovaries for APAP between 10 and 12 DW.

Maternal and fetal blood APAP concentrations, as well as pharmacodynamics, were reported to be similar according to several experimental strategies and physiologically based pharmacokinetic PBPK modeling (30, 42, 43). To the best of our knowledge, there are unfortunately no available findings regarding APAP distribution in the hFO. Hence, we cannot exclude that the exposure of the ovary can be different in vivo via blood flow and ex vivo via exchanges with culture medium. However, the range of APAP concentrations used in this study was chosen to cover peak plasma concentrations after therapeutic doses and subsequent concentrations corresponding to biotransformation and clearing. We also included a typical concentration corresponding to APAP overdosage and classically used as a cytotoxicity-inducing concentration in several cellular models (41, 44-46). Of note, interindividual variability was high for APAP concentrations below 10−4 M, while almost absent at the toxic concentration of 10−3 M. Therefore, 10−3 M APAP-induced cytotoxicity in our ex vivo hFO culture model is consistent with cell line models.

Since germ cells commit to meiosis from 11 DW onward, a biologically consistent hypothesis to explain the difference in response of 7- to 9-DW ovaries compared to that of 10- to 12-DW ovaries could be that APAP differentially affects germ cells according to their differentiation stage. The percentage of M2A-positive cells was not affected by APAP regardless of the drug concentration and the developmental stage considered, while the total number of M2A-positive cells was significantly decreased, in particular in 10- to 12-DW ovaries explants exposed to APAP at 10−7 M and above. In addition, the density of germ cells, quantified on histological sections according to their size and chromatin compaction, indicated an impact of APAP on small (<9 µm) germ cells regardless of age but not on larger germ cells at subtoxic APAP concentrations. This suggests that APAP selectively impacts small germ cells, in agreement with previous observations showing a decrease in the density of immature TFAP2C-positive germ cells after exposure to 10−5 M APAP for 7 days (18). The developmental stages of exposure in rodent studies encompassed 2 crucial consecutive, morphogenetic events occurring in the germ cell lineage (ie, mitosis and meiosis) and therefore did not allow for the identification of a specific window of sensitivity (47). Our data do not support the hypothesis that APAP induces a shift of oogonia toward meiosis (15) in first-trimester hFO as we did not observe any increase in the density of larger germ cells. By contrast, proliferating hepatic HepaRG cells were reported to be more sensitive to APAP than differentiating ones (48), and APAP is known to interfere with mitotic checkpoints and DNA synthesis (40, 41, 45, 46, 49). Since small germ cells are actually actively proliferating oogonia, a working hypothesis that will require further investigations is a preferential effect of APAP on cycling germ cells.

In the fetal rat ovary, APAP-induced germ cell depletion was associated with a slight decrease in PGE2 content (15). In the NTera2 germ cell line, cell number was reduced following exposure to either APAP or PGE2 receptor antagonists, whereas PGE2 agonists prevented the APAP-induced loss in cell number (18). In humans, since PGE2 is considered as an autocrine regulator of germ cell development (50), it was hypothesized that APAP-induced dysregulation of prostaglandin could also explain deleterious impacts on germ cells (18). However, we show here that exposure levels equivalent to or lower than therapeutic doses of APAP had no effect on PGE2 or PGD2 levels. This is in contrast to ibuprofen (27), which is consistent with the weaker inhibitory effect of APAP on prostaglandin production (51, 52). Our results suggest that APAP impacts the hFO independently of prostaglandin inhibition, but its mechanisms of action remain to be elucidated.

Although steroidogenic pathway members are reportedly expressed as early as 11 DW (9-13), only 2 studies have reported conversion of pregnenolone and androgens into androgens and estrogens, respectively, within the hFO (53, 54). We show here that APAP can interfere with progesterone, 17OHP, and E2 production. During pregnancy, circulating estrogens are mostly conjugated to serum proteins, therefore reducing the levels of bioactive-free estrogens (55). The roles for a local production of estrogens at this developmental stage, as well as the consequences of its alterations, remain to be determined in humans. The alteration of the oogonia pool with decreased local estrogens could be consistent with the phenotype reported in CYP19A1-deficient rabbits (56). However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of an ex vivo specific endocrine disruption of the steroidogenesis in the hFO.

In the adult liver, APAP is mainly detoxified by glucuronidation and sulfation while a small proportion is oxidized to form the reactive metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (57, 58). Our recent bulk RNAseq data (38) indicates that the ovaries do not express the main cytochromes P450 (CYPs), metabolizing APAP into N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine [ie, CYP2E1, CYP3A4 and CYP1A2 (data not shown)]. However, previous reports showed that APAP can be toxic via a CYP-independent pathway, which can eventually lead to mitochondrial dysfunction (59, 60). Hence, further investigations are required to determine whether this CYP-independent mechanism of APAP toxicity might explain some of our results including impaired production of sex steroids. In contrast, we show that fetal ovaries as young as 8 DW and at least up to 12 DW metabolize APAP mainly through sulfation, as observed in the fetal liver (57). The stability of sulfation rates despite increasing APAP concentrations suggests that, at least under our experimental conditions, the underlying detoxification system was neither preferentially induced nor saturated. The rapid production of sulfoconjugates (ie, during the first 24 hours) also suggests that sulfotransferases are already expressed in nonexposed ovaries, rather than being induced by the exposure to APAP. Although we cannot rule out the involvement of several SULT enzymes, of those detected at the messenger RNA level, only SULT1E1 was detected in situ. This is consistent with the reports that SULT1E1, one of the main sulfotransferase enzymes known to metabolize APAP, is not only expressed but active in human fetal liver and in extrahepatic tissues (61-64). In 7-DW fetuses, we also observed a very high expression of this enzyme in the mesonephros, suggesting a possible local detoxification role in vivo. The precise identity of the ovarian cell type expressing SULT1E1 remains an avenue of research.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that biologically relevant concentrations of APAP can interfere with hFO development ex vivo. The underlying mechanisms are likely to differ depending on fetal age and APAP concentration, but they may be independent of the prostaglandin pathway. We also confirm that active steroidogenesis takes place within first trimester hFOs. Furthermore, we provide evidence that the hFO displays intrinsic detoxification capacities, although this might not be sufficient to provide significant protection against prolonged or acute exposure to xenobiotics. Nevertheless, we demonstrate, for the first time, that APAP disrupts human fetal ovarian endocrine activity and is therefore an endocrine disruptor in the developing human female.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the staff of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and the Department of Pediatric Surgery of the Rennes Sud Hospital (Rennes, France) and the participating women, without whom this study would not have been possible. The authors are grateful to Isabelle Coiffec for assistance on organ collection and the H2P2 histology facility of Rennes 1 University. We are grateful to Bernard Jégou for his critical advice in the design of this project, and to Prof. Paul A. Fowler and Catherine Lavau for their critical reading of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

L.L.L., S.L.P., and S.M.G. designed, performed, and analyzed experiments (organ collection for SMG and L.L.L.; culture, histology, cell counts, and flow cytometry for S.L.P and L.L.L.; culture, histology, and cell counts for S.M.G.). N.C. performed the statistical analyses and contributed to the writing of the corresponding section. L.L. performed culture. C.D.L. performed prostaglandins measurements. F.G. performed the steroids measurements and contributed to the writing of the corresponding section. B.F. and T.G. designed APAP and metabolites measurements. T.G. and L.L.L. performed APAP and metabolites measurements. V.L. supervised the collection of the first trimester human fetal ovarian samples. S.M.G. and A.D.R. conceptualized the project. L.L.L. and S.M.G. prepared the visualization of the data and wrote the original draft. S.L.P. and A.D.R. contributed to critical discussions, reviewed, and edited the manuscript.

Financial Support

This study was supported by the Agence nationale de la recherche (ANR-15-CE34-0001-01), the Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé (ANSM; # 2014S032) and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 FREIA project (grant agreement no. 825100).

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Current Affiliation

L.L.L.: Institute of Medical Sciences, University of Aberdeen, Foresterhill, Aberdeen, AB25 2ZD, UK; S.L-P.: Univ Poitiers, STIM, CNRS UMR 4061, Poitiers Cedex 9, France.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

- 1. Kristensen DM, Mazaud-Guittot S, Gaudriault P, et al. Analgesic use—prevalence, biomonitoring and endocrine and reproductive effects. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(7):381-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zafeiri A, Mitchell RT, Hay DC, Fowler PA. Over-the-counter analgesics during pregnancy: a comprehensive review of global prevalence and offspring safety. Hum Reprod Update. 2021;27(1):67-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bauer AZ, Swan SH, Kriebel D, et al. Paracetamol use during pregnancy - a call for precautionary action. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17(12):757-766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gurney J, Richiardi L, McGlynn KA, Signal V, Sarfati D. Analgesia use during pregnancy and risk of cryptorchidism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(5):1118-1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mazaud-Guittot S, Nicolaz CN, Desdoits-Lethimonier C, et al. Paracetamol, aspirin, and indomethacin induce endocrine disturbances in the human fetal testis capable of interfering with testicular descent. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(11):E1757-E1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van den Driesche S, Macdonald J, Anderson RA, et al. Prolonged exposure to acetaminophen reduces testosterone production by the human fetal testis in a xenograft model. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(288):288ra-28880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kristensen DM, Hass U, Lesné L, et al. Intrauterine exposure to mild analgesics is a risk factor for development of male reproductive disorders in human and rat. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(1):235-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kristensen DM, Lesné L, Le Fol V, et al. Paracetamol (acetaminophen), aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) and indomethacin are anti-androgenic in the rat foetal testis. Int J Androl. 2012;35(3):377-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vaskivuo TE, Mäentausta M, Törn S, et al. Estrogen receptors and estrogen-metabolizing enzymes in human ovaries during fetal development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(6):3752-3756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Juengel JL, Heath DA, Quirke LD, McNatty KP. Oestrogen receptor alpha and beta, androgen receptor and progesterone receptor mRNA and protein localisation within the developing ovary and in small growing follicles of sheep. Reproduction. 2006;131(1):81-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gould DA, Moscoso GJ, Young MP, Barton DP. Human first trimester fetal ovaries express oncofetal antigens and steroid receptors. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2000;7(2):131-138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilson CM, McPhaul MJ. A and B forms of the androgen receptor are expressed in a variety of human tissues. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1996;120(1):51-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Connan-Perrot S, Léger T, Lelandais P, et al. Six decades of research on human fetal gonadal steroids. Int J Mol Sci . 2021;22(13):6681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Edson MA, Nagaraja AK, Matzuk MM. The mammalian ovary from genesis to revelation. Endocr Rev. 2009;30(6):624-712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dean A, van den Driesche S, Wang Y, et al. Analgesic exposure in pregnant rats affects fetal germ cell development with inter-generational reproductive consequences. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holm JB, Mazaud-Guittot S, Danneskiold-Samsøe NB, et al. Intrauterine exposure to paracetamol and aniline impairs female reproductive development by reducing follicle reserves and fertility. Toxicol Sci. 2016;150(1):178-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Johansson HKL, Jacobsen PR, Hass U, et al. Perinatal exposure to mixtures of endocrine disrupting chemicals reduces female rat follicle reserves and accelerates reproductive aging. Reprod Toxicol. 2016;61:186-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hurtado-Gonzalez P, Anderson RA, Macdonald J, et al. Effects of exposure to acetaminophen and ibuprofen on fetal germ cell development in both sexes in rodent and human using multiple experimental systems. Environ Health Perspect. 2018;126(4):047006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thompson RA, Isin EM, Ogese MO, Mettetal JT, Williams DP. Reactive metabolites: current and emerging risk and hazard assessments. Chem Res Toxicol. 2016;29(4):505-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Krishna DR, Klotz U. Extrahepatic metabolism of drugs in humans. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1994;26(2):144-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Koren G, Ornoy A. The role of the placenta in drug transport and fetal drug exposure. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2018;11(4):373-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hines RN, McCarver DG. The ontogeny of human drug-metabolizing enzymes: phase I oxidative enzymes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300(2):355-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Myllynen P, Immonen E, Kummu M, Vähäkangas K. Developmental expression of drug metabolizing enzymes and transporter proteins in human placenta and fetal tissues. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2009;5(12):1483-1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rane A, Ackermann E. Metabolism of ethylmorphine and aniline in human fetal liver. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1972;13(5part1):663-670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pelkonen O, Kaltiala EH, Larmi TKI, Kärki NT. Comparison of activities of drug-metabolizing enzymes in human fetal and adult livers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1973;14(5):840-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Levy G. Pharmacokinetics of fetal and neonatal exposure to drugs. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;58(5 suppl):9s-16s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leverrier-Penna S, Mitchell RT, Becker E, et al. Ibuprofen is deleterious for the development of first trimester human fetal ovary ex vivo. Hum Reprod. 2018;33(3):482-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rayburn W, Shukla U, Stetson P, Piehl E. Acetaminophen pharmacokinetics: comparison between pregnant and nonpregnant women. Am J Obs Gynecol. 1986;155(6):1353-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Beaulac-Baillargeon L, Rocheleau S. Paracetamol pharmacokinetics during the first trimester of human pregnancy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;46(5):451-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Naga Rani MA, Joseph T, Narayanan R. Placental transfer of paracetamol. J Indian Med Assoc. 1989;87(8):182-183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bendsen E, Laursen SB, Olesen C, Westergaard LG, Andersen CY, Byskov AG. Effect of 4-octylphenol on germ cell number in cultured human fetal gonads. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(2):236-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Anderson RA, Fulton N, Cowan G, Coutts S, Saunders PT. Conserved and divergent patterns of expression of DAZL, VASA and OCT4 in the germ cells of the human fetal ovary and testis. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7(1):1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leverrier-Penna S, Michel A, Lecante LL, et al. Exposure of human fetal kidneys to mild analgesics interferes with early nephrogenesis. FASEB J. 2021;35(7):e21718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gicquel T, Aubert J, Lepage S, Fromenty B, Morel I. Quantitative analysis of acetaminophen and its primary metabolites in small plasma volumes by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. J Anal Toxicol. 2013;37(2):110-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Michaut A, Le Guillou D, Moreau C, et al. A cellular model to study drug-induced liver injury in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: application to acetaminophen. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2016;292:40-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Giton F, Sirab N, Franck G, et al. Evidence of estrone-sulfate uptake modification in young and middle-aged rat prostate. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2015;152:89-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Giton F, Trabado S, Maione L, et al. Sex steroids, precursors, and metabolite deficiencies in men with isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and panhypopituitarism: a GCMS-based comparative study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):E292-E296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lecluze E, Rolland AD, Filis P, et al. Dynamics of the transcriptional landscape during human fetal testis and ovary development. Hum Reprod. 2020;35(5):1099-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fulton N, Martins da Silva SJ, Bayne RAL, Anderson RA. Germ cell proliferation and apoptosis in the developing human ovary. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(8):4664-4670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hongslo J, Bjørge C, Schwarze P, et al. Paracetamol inhibits replicative DNA synthesis and induces sister chromatid exchange and chromosomal aberrations by inhibition of ribonucleotide reductase. Mutagenesis. 1990;5(5):475-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wiger R, Finstad HS, Hongslo JK, Haug K, Holme JA. Paracetamol inhibits cell cycling and induces apoptosis in HL-60 cells. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;81(6):285-293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nitsche JF, Patil AS, Langman LJ, et al. Transplacental passage of acetaminophen in term pregnancy. Am J Perinatol. 2017;34(6):541-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mian P, Allegaert K, Conings S, et al. Integration of placental transfer in a fetal-maternal physiologically based pharmacokinetic model to characterize acetaminophen exposure and metabolic clearance in the fetus. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2020;59(7):911-925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Behrends V, Giskeødegård GF, Bravo-Santano N, Letek M, Keun HC. Acetaminophen cytotoxicity in HepG2 cells is associated with a decoupling of glycolysis from the TCA cycle, loss of NADPH production, and suppression of anabolism. Arch Toxicol. 2019;93(2):341-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Holme JA, Hongslo JK, Bjørnstad C, Harvison PJ, Nelson SD. Toxic effects of paracetamol and related structures in V79 Chinese hamster cells. Mutagenesis. 1988;3(1):51-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rauchman MI, Nigam SK, Delpire E, Gullans SR. An osmotically tolerant inner medullary collecting duct cell line from an SV40 transgenic mouse. Am J Physiol. 1993;265(3 Pt 2):416-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Arendrup FS, Mazaud-Guittot S, Jégou B, Kristensen DM. EDC IMPACT: Is exposure during pregnancy to acetaminophen/paracetamol disrupting female reproductive development? Endocr Connect. 2018;7(1):149-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Young CKJ, Young MJ. Comparison of HepaRG cells following growth in proliferative and differentiated culture conditions reveals distinct bioenergetic profiles. Cell Cycle. 2019;18(4):476-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ayla S, Bilir A, Ertürkoğlu S, et al. Effects of different drug treatments on the proliferation of human ovarian carcinoma cell line MDAH-2774. Turkish J Med Sci. 2018;48(2):441-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bayne RAL, Eddie SL, Collins CS, Childs AJ, Jabbour HN, Anderson RA. Prostaglandin E2 as a regulator of germ cells during ovarian development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(10):4053-4060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ohashi N, Kohno T. Analgesic effect of acetaminophen: a review of known and novel mechanisms of action. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:580289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ouellet M, Percival MD. Mechanism of acetaminophen inhibition of cyclooxygenase isoforms. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;387(2):273-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. George FW, Wilson JD. Conversion of androgen to estrogen by the human fetal ovary. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1978;47(3): 550-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sano Y, Okinaga S, Arai K. Metabolism of [14C]-C21 steroids in the human fetal ovaries. J Steroid Biochem. 1982;16(6):721-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wu CH, Mennuti MT, Mikhail G. Free and protein-bound steroids in amniotic fluid of midpregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;133(6):666-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jolivet G, Daniel-Carlier N, Harscoët E, et al. Fetal estrogens are not involved in sex determination but critical for early ovarian differentiation in rabbits. Endocrinology. 2022;163(1):bqab210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rollins DE, von Bahr C, Glaumann H, Moldéus P, Rane A. Acetaminophen: potentially toxic metabolite formed by human fetal and adult liver microsomes and isolated fetal liver cells. Science. 1979;205(4413):1414-1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mazaleuskaya LL, Sangkuhl K, Thorn CF, Fitzgerald GA, Altman RB, Klein TE. PharmGKB summary: pathways of acetaminophen metabolism at the therapeutic versus toxic doses. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2015;25(8):416-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Prill S, Bavli D, Levy G, et al. Real-time monitoring of oxygen uptake in hepatic bioreactor shows CYP450-independent mitochondrial toxicity of acetaminophen and amiodarone. Arch Toxicol. 2016;90(5):1181-1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Miyakawa K, Albee R, Letzig LG, et al. A cytochrome P450-independent mechanism of acetaminophen-induced injury in cultured mouse hepatocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;354(2):230-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stanley EL, Hume R, Coughtrie MWH. Expression profiling of human fetal cytosolic sulfotransferases involved in steroid and thyroid hormone metabolism and in detoxification. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2005;240(1-2):32-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pacifici GM. Sulfation of drugs and hormones in mid-gestation human fetus. Early Hum Dev. 2005;81(7):573-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hines RN. The ontogeny of drug metabolism enzymes and implications for adverse drug events. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;118(2):250-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ladumor MK, Bhatt DK, Gaedigk A, et al. Ontogeny of hepatic sulfotransferases and prediction of age-dependent fractional contribution of sulfation in acetaminophen metabolism. Drug Metab Dispos. 2019;47(8):818-831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.