Abstract

Background

Insulin pump use in type 1 diabetes management has significantly increased in recent years, but we have few data on its impact on inpatient admissions for acute diabetes complications.

Methods

We used the 2006, 2009, 2012, and 2019 Kids’ Inpatient Database to identify all-cause type 1 diabetes hospital admissions in those with and without documented insulin pump use and insulin pump failure. We described differences in (1) prevalence of acute diabetes complications, (2) severity of illness during hospitalization and disposition after discharge, and (3) length of stay (LOS) and inpatient costs.

Results

We identified 228 474 all-cause admissions. Insulin pump use was documented in 7% of admissions, of which 20% were due to pump failure. The prevalence of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) was 47% in pump nonusers, 39% in pump users, and 60% in those with pump failure. Admissions for hyperglycemia without DKA, hypoglycemia, sepsis, and soft tissue infections were rare and similar across all groups. Admissions with pump failure had a higher proportion of admissions classified as major severity of illness (14.7%) but had the lowest LOS (1.60 days, 95% CI 1.55-1.65) and healthcare costs ($13 078, 95% CI $12 549-$13 608).

Conclusions

Despite the increased prevalence of insulin pump in the United States, a minority of pediatric admissions documented insulin pump use, which may represent undercoding. DKA admission rates were lower among insulin pump users compared to pump nonusers. Improved accuracy in coding practices and other approaches to identify insulin pump users in administrative data are needed, as are interventions to mitigate risk for DKA.

Keywords: diabetic ketoacidosis, type 1 diabetes, insulin pump, inpatient admissions

There have been many advances in diabetes management over the past several decades. While some innovations such as ultralong-acting basal insulin have been found to reduce acute complications of diabetes [eg, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), hypoglycemia] (1, 2), other innovations, such as insulin pumps, may also have the potential to predispose users to acute diabetes complications. For example, ketoacidosis may occur in the setting of technical failures in the insulin pump’s infusion system and patients may be at increased risk of DKA due to its use of only short-acting insulin (3). Additionally, subcutaneous catheters in insulin pumps may increase risk for soft tissue infections (4). While we have seen a dramatic increase in insulin pump use in type 1 diabetes management over the past 20 years from an estimated 1% in 1995 to 53% in 2017 (5), we know little about the effect of insulin pump use on inpatient admissions for acute diabetes complications. This may be especially relevant in the setting of the rising rates of DKA seen nationally (6).

Using data from the Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID), which is the largest all-payer pediatric inpatient care database in the United States, our goal was to compare trends in pediatric type 1 diabetes admissions among youth with and without insulin pump use and those with pump failure between 2006 to 2016. Specifically, we sought to assess the prevalence of acute diabetes complications, clinical presentation and outcome (severity and disposition), length of stay (LOS), and health expenditures.

Methods

Study Population

We used the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project KID, developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (7). KID is a publicly available deidentified database containing admissions from children and youth ≤ 20 years old from 42 000 hospitals across 46 states, sampled at a rate of 80% for non-newborn admissions. KID data are released every 3 years, and our study years included 2006, 2009, 2012, and 2016 (the transition from the International Classification of Diseases ICD-9 to ICD-10 coding led to an update in 2016 instead of 2015). We used ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes to categorize admissions into 4 groups: (1) all-cause admissions in patients with type 1 diabetes excluding hospital births, (2) type 1 diabetes admissions without documentation of insulin pump use (ie, pump nonusers), (3) type 1 diabetes admissions with documentation of insulin pump use (ie, pump users), and (4) a subset of insulin pump users who had documented insulin pump failure. We defined insulin pump user based on the presence of an ICD code indicating insulin pump status or a pump related complication. Insulin pump failure admissions were identified using the ICD- 9 and ICD-10 codes for insulin pump failures and complications [Supplemental Table 1 (8)].

Data Elements

We summarized patient and hospital-level variables among the 4 admission categories (all type 1 diabetes, insulin pump users, nonusers, and insulin pump failures). Patient-level variables included age, sex, race/ethnicity, admission payer, income, and urbanicity. Race/ethnicity were defined as reported by the data source (hospitals) and presumed to be self-reported. Admission payers were defined as public insurance (eg, Medicare, Medicaid), private payers (eg, private health maintenance organizations, preferred provider organizations), or other (worker’s compensation, Title V, Civilian Health and Medical Health and Medical Program of the Department of Veteran Affairs, or other government programs), and self-pay or no charge (eg, charity care). Median household income was reported as quartiles as determined based on median household income per zip code for the calendar year. Patient location was reported per the 2010 US urban-rural classification, which defines an urbanized area as ≥50 000 residents and a nonurban area as less than 50 000 residents. Hospital-level variables included region, ownership, and size. Four geographical regions of the United States were also specified: Northeast, Midwest, South and West. Hospital type was defined as either government or private (eg, nonprofit private or private investment). Size was characterized as small, medium, or large, based on hospital region and urbanicity.

We compared the prevalence of acute complications associated among our 4 aforementioned admission categories. Acute complications, including DKA, hyperglycemia without DKA, hypoglycemia, soft tissue infections, and sepsis, were ascertained by primary and secondary billing codes [Supplemental Table 2 (8)]. Severity of illness on admission was determined using All Patient Refined Diagnosis-Related Groups (9), which classifies patients according to their reasons for admission, severity of illness, risk of mortality, and resource intensity. Disposition indicated the context of the hospital discharge (eg, transfer to skilled nursing facility, discharge against medical advice, patient death, etc.). A routine discharge was considered a discharge to home or self-care. We also evaluated LOS, defined as the difference in days between the admission date and the discharge date, and admission costs. Total admission healthcare cost was reported by the hospital and does not include professional fees and noncovered charges. Healthcare costs were reported as 2016 US dollars and accounted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index (10).

Statistical Analysis

Weights provided by KID were used to generate nationally representative estimates of hospital admissions, and all analyses accounted for the stratified sampling design. We used descriptive statistics to describe the weighted frequency of patient and hospital-level characteristics, acute diabetes complications, severity of illness, disposition, LOS and inpatient healthcare expenditures across our 4 categories of hospital admissions. Chi-squared test was used to evaluate for statistical differences between insulin pump users and nonusers. We performed logistic regression to evaluate the association between insulin pump failure and DKA among insulin pump users, adjusting for patient and hospital characteristics.

All analyses were performed with Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). This study was Institutional Review Board exempt since it was a secondary analysis of preexisting and deidentified data. This report follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guidelines for cross-sectional studies.

Results

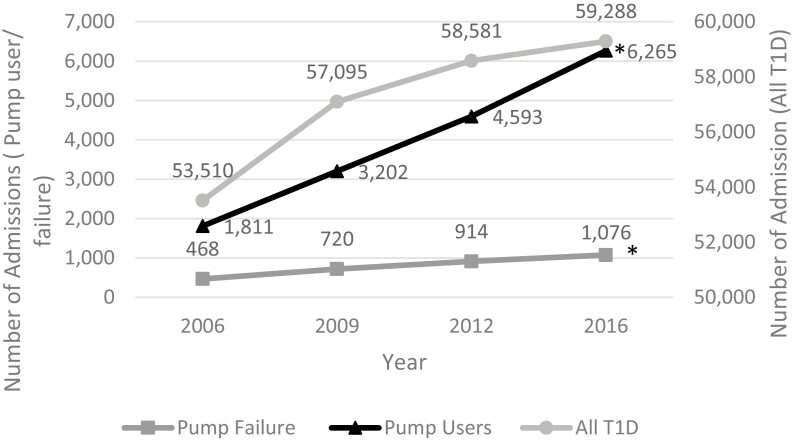

We identified a total of 228 474 all-cause hospital admissions in children with type 1 diabetes, only 7% (n = 15 871) of which documented insulin pump use. Between 2006 and 2016, the number of all-cause admissions in pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes and admissions among pump users increased by 10% (Fig. 1). Admissions with documented pump failure also increased from 468 in 2016 to 1076 in 2019, but represented a subset of only 20% of pump user admissions overall.

Figure 1.

Figure shows weighted number of admissions across time for all type 1 diabetes admissions, those with type 1 diabetes who are insulin users, and those with type 1 diabetes who are insulin pump users with pump failure. *P for trend <0.001 for pump users and pump failure admissions, respectively compared to all-cause admissions in those with type 1 diabetes.

Insulin pump users were more likely to be between the ages 16 and 20 years (51%), female (57%), White (67%), and have private insurance (61%) but were distributed equally across all income quartiles (Table 1). Youth hospitalized with insulin pump failure had similar demographics. As compared to pump users, pump nonusers were more likely to be Black (17% vs 8%), Hispanic (12% vs 7%), from the lowest income quartile (31% vs 23%), and have public insurance (43% vs 31%).

Table 1.

Demographics of admissions in patients with and without insulin pump use

| All type 1 diabetes, n (%) | Pump nonuser, n (%) | Pump user, n (%) | P-valuea | Pump failure, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 228 474 (100) | 212 634 (100) | 15 871 (100) | 3179 (100) | |

| Age, years | <0.001 | ||||

| 0-5 | 16 553 (7.3) | 15 939 (7.5) | 615 (3.9) | 90 (2.8) | |

| 6-10 | 33 254 (14.6) | 31 148 (14.6) | 2107 (13.3) | 543 (17.1) | |

| 11-15 | 63 986 (28.0) | 58 910 (27.7) | 5076 (32.0) | 1100 (34.6) | |

| 16-20 | 113 801 (49.7) | 105 742 (49.8) | 8059 (50.7) | 1444 (45.5) | |

| Unknown | 879 (0.4) | 865 (0.4) | 15 (0.1) | <10 (0.0) | |

| Sex | <0.001 | ||||

| Male | 101 131(44.3) | 94 420 (44.5) | 6712 (42.3) | 1423 (44.8) | |

| Female | 125 949 (55.1) | 116 810 (54.9) | 9139 (57.6) | 1746 (54.9) | |

| Unknown | 1394 (0.6) | 1373 (0.6) | 21 (0.1) | <10 (0.3) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 116 679(51.1) | 105 997 (49.9) | 10 682 (67.4) | 2029 (63.9) | |

| Black | 37 815 (16.6) | 36 524 (17.2) | 1291 (8.1) | 279 (8.8) | |

| Hispanic | 27 261 (11.9) | 26 061 (12.3) | 1200 (7.6) | 293 (9.2) | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 2304 (1.0) | 2200 (1.0) | 103 (0.6) | 26 (0.8) | |

| Native American | 1424 (0.6) | 1369 (0.6) | 55 (0.3) | 11 (0.3) | |

| Other/unknown | 42 991 (18.8) | 40 452 (19.0) | 2540 (16.0) | 541 (17.0) | |

| Payer | <0.001 | ||||

| Private | 103 990(45.5) | 94 361 (44.4) | 9629 (60.6) | 1917 (60.3) | |

| Public | 96 780(42.4) | 91 850 (43.2) | 4930 (31.1) | 1011 (31.8) | |

| Self-pay or no charge | 14 821(6.5) | 14 384 (6.7) | 437 (2.8) | 68 (2.1) | |

| Other/unknown | 12 883(5.6) | 12 008 (5.7) | 876 (5.5) | 183 (5.8) | |

| Urbanicity | <0.001 | ||||

| Nonurban areas | 41 519 (18.2) | 38 185 (18.0) | 3334 (21.0) | 659 (20.8) | |

| Urban areas | 185 284(81.1) | 172 832 (81.3) | 12 452 (78.5) | 2500 (78.6) | |

| Unknown | 1672 (0.7) | 1585 (0.7) | 86 (0.5) | 19 (0.6) | |

| Household income | |||||

| Quartile 1 | 68 875(30.1) | 65 192 (30.7) | 3683 (23.2) | <0.001 | 789 (24.9) |

| Quartile 2 | 57 995 (25.5) | 53 925 (25.4) | 4070 (25.6) | 776 (24.4) | |

| Quartile 3 | 52 860(23.1) | 48 764 (22.9) | 4096 (25.9) | 780 (24.5) | |

| Quartile 4 | 44 441(19.4) | 40 696 (19.1) | 3745 (23.6) | 766 (24.1) | |

| Unknown | 4303 (1.9) | 44 026 (1.9) | 277 (1.7) | 68 (2.1) | |

| Region of hospital | <0.001 | ||||

| Northeast | 35 451 (15.5) | 32 898 (15.5) | 2553 (16.1) | 526 (16.5) | |

| Midwest | 57 517(25.2) | 52 968 (24.9) | 4549 (28.7) | 832 (26.2) | |

| South | 86 811(38.0) | 81 476 (38.3) | 5335 (33.6) | 1125 (35.4) | |

| West | 48 695(21.3) | 45 261 (21.3) | 3434 (21.6) | 695 (21.9) | |

| Hospital type | <0.001 | ||||

| Government | 24 682 (10.8) | 23 028 (10.8) | 1654 (10.4) | 369 (11.6) | |

| Private | 159 358 (69.8) | 146 688 (69.0) | 12 669 (79.8) | 2409 (75.8) | |

| Unknown | 44 435(19.4) | 42 887 (20.2) | 1548 (9.8) | 401 (12.6) | |

| Bed size | |||||

| Small | 27 183 (11.9) | 25 376 (11.9) | 1807 (11.4) | 0.011 | 369 (11.6) |

| Medium | 56 298 (24.7) | 52 378 (24.6) | 3920 (24.7) | 719 (22.6) | |

| Large | 138 091(60.4) | 128 240 (60.4) | 9851 (62.1) | 2027 (63.8) | |

| Unknown | 6903 (3.0) | 6609 (3.1) | 293 (1.8) | 64 (2.0) | |

| Year | |||||

| 2006 | 53 510 (23.4) | 51 710 (24.3) | 1811 (11.4) | <0.001 | 468 (14.7) |

| 2009 | 57 095 (25.0) | 53 893 (25.3) | 3202 (20.2) | 720 (22.6) | |

| 2012 | 58 581 (25.7) | 53 988 (25.4) | 4593 (28.9) | 914 (28.8) | |

| 2016 | 59 288 (25.9) | 53 023 (24.9) | 6265 (39.5) | 1076 (33.9) |

a P-value is noted for difference between pump user and nonpump user group.

DKA accounted for 48% of all admissions overall (Table 2). DKA admissions were more common among admissions with pump failure than pump users and pump nonusers [60% vs 39%, and 47%, respectively (P < 0.001)]. In an adjusted analysis (data not shown), the presence of insulin pump failure was associated with an 8.5-fold higher odds (95% CI 7.13-10.17) for DKA among insulin pump users. DKA admissions with documented pump failure increased over time from 423 in 2006 to 1032 in 2016 [Supplemental Table 1 (8)]. Admissions for hyperglycemia without DKA, hypoglycemia and sepsis were rare and similar across all groups. Soft tissue infections occurred at a similar rate across insulin pump users and nonusers (2.3 vs 2.6% P = 0.121).

Table 2.

Prevalence of acute diabetes complications, clinical presentation, and disposition of type 1 diabetes admissions

| All-cause type 1 diabetes | Pump nonuser | Pump user | P-valuea | Pump failure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n | 228 506 | 212 634 | 15 871 | 3179 | |

| Acute diabetes complications, % | |||||

| DKA | 48.14 | 46.50 | 39.29 | <0.001 | 60.33 |

| Soft tissue | 2.40 | 2.38 | 2.63 | 0.121 | 1.89 |

| Sepsis | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.42 | 0.039 | 0.28 |

| Hyperglycemia | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.16 | <0.001 | 0.22 |

| Severity of illness, n | <0.001 | ||||

| Minor | 45 999(20.1) | 44 272 (20.8) | 1726 (10.9) | 89.1 (2.8) | |

| Moderate | 154 207(67.5) | 142 276 (66.9) | 11 932 (75.2) | 2590 (81.5) | |

| Major | 24 723(10.8) | 22 710 (10.7) | 2014 (12.7) | 466 (14.7) | |

| Extreme | 3480 (1.5) | 3282 (1.5) | 199 (1.3) | 34 (1.1) | |

| No class | 65 (<0.1) | 64 (<0.1) | <10 (<0.1) | <10 (<0.1) | |

| Disposition, n | <0.001 | ||||

| Routine | 212 474 (93.0) | 197 284 (92.8) | 15 190 (95.7) | 3123 (98.3) | |

| Transfer to short-term hospital | 2551 (1.1) | 2426 (1.1) | 125 (0.8) | 10.9 (0.3) | |

| Transfer other: SNF, ICF, etc | 2952 (1.1) | 2795 (1.3) | 157 (1.0) | <10 (0.2) | |

| Home healthcare | 5274 (1.3) | 5088 (2.4) | 186 (1.2) | 13.8 (0.4) | |

| Against medical advice | 4875 (2.3) | 4675 (2.2) | 200 (1.3) | 23.6 (0.7) | |

| Died | 265 (2.1) | 254 (0.1) | 11.2 (0.1) | 1.61 (<0.1) | |

| Discharged alive, unknown destination | 30.5 (<0.1) | 30.5 (<0.1) | <10 (<0.1) | <10 (<0.1) | |

| Unknown | 53.1 (<0.1) | 51.7 (<0.1) | 1.44 (<0.1) | < 10(<0.1) |

This table demonstrates the prevalence of each acute complications between admission types.

Abbreviations: ICF, intermediate care facility; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis group; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

a P-value is noted for difference between pump users and nonusers user groups.

The majority of admissions among youth with type 1 diabetes were classified as minor or moderate severity of illness (~85%) (Table 2). Insulin pump nonusers had more admissions of minor severity of illness while those with pump failure had the highest proportion of admissions of major severity of illness. A routine discharge was the most common mode of disposition in all groups (Table 2). Admissions in pump nonusers had a higher prevalence of transfers to other facilities, discharge with home health, and discharge against medical advice. Mortality was low across all groups. Mean LOS (2.89 days, 95% CI 2.84-2.93) (Table 3) and total charges ($20 486, 95% CI $19 929-$21 043) were the highest for admissions in insulin pump nonusers and lowest in insulin pump users admitted with pump failure (LOS 1.60 days, 95% CI 1.55-1.65; charge $13 078, 95% CI $12 549-$13 608).

Table 3.

Length of stay and charges for insulin pump admissions

| All type 1 diabetes | Pump nonuser | Pump user | Pump failure | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | |

| LOS, days | 2.84 | 2.80-2.89 | 2.89 | 2.84-2.93 | 2.24 | 2.18-2.30 | 1.60 | 1.55-1.65 |

| Chargea | $18 921 | $18 392-$19 450 | $20 486 | $19 929-$21 043 | $17 672 | $16 910-$18 434 | $13 078 | $12 549-$13 608 |

Abbreviation: LOS, length of stay.

aCharges adjusted for inflation and are reported in 2016 dollars.

Discussion

From 2006 to 2016, the number of all-cause admissions among youth with type 1 diabetes has increased, including admissions in youth with and without documented insulin pump use. Although admissions among insulin pump users increased substantially over time, they represented less than 1 in 10 pediatric type 1 diabetes admissions overall. While admissions for insulin pump failure were also infrequent, occurring in 2 out of 10 pump user admissions overall, they did increase over time. To our knowledge, our study is the first to use a nationally representative sample to describe features and trends of pediatric inpatient admissions with insulin pump use in the United States.

Although studies estimate that 40% to 50% of patients with type 1 diabetes use insulin pumps (11, 12), we found that insulin pump use was documented in only 7% of all type 1 diabetes admissions (increasing from 3.3% in 2006 to 10.6% in 2016). While it is possible that insulin pump users may be much less likely to be admitted than nonusers (13), concerns regarding inpatient undercoding for insulin pump use is also a concern. To our knowledge, our study is the first to describe inpatient insulin pump coding rates in the United States. We also found that admissions among insulin pump users occurred mostly in Whites with private insurance. These findings are consistent with other studies that have shown disparities in technology access in type 1 diabetes (12, 14, 15). Interestingly, admissions among insulin pump users occurred equally across all income quartiles. Since insulin pump use is more likely to occur in those of higher income (12, 14, 15), this suggests that insulin pump users of lower income may be more likely to have a hospital admission. Given disparities in technology adoption, it will be critically important for future work to examine disparities in how diabetes technology may be prescribed, initiated, or used and if this can explain differences in diabetes outcomes.

DKA was a common diagnosis in insulin pump nonuser, user, and insulin pump failure admissions. Our group and others have also shown rising rates of DKA admissions nationally (16-18). The reasons for increased prevalence of DKA admissions are not entirely clear. Some studies suggest that nonadherence in the setting of rising insulin costs may be a significant contributor as well as other social determinants of health (6, 18-20). These issues raise concerns about the overall care of youth with type 1 diabetes and potential impacts on growing diabetes related healthcare expenditures in the United States.

Interestingly, insulin pump users had a lower prevalence of DKA admissions as compared to nonusers. The literature is mixed as to whether DKA risk with insulin pump use matches that of multiple daily injection use (3, 21-23), but insulin pump malfunctions are not uncommon and can lead to hospitalizations for DKA. In a survey of 91 pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes on insulin pumps, approximately 50% reported at least 1 infusion set/site-related malfunction in the past year (24). Among all patient surveyed, about 10% experienced an insulin pump adverse effect resulting in hospitalization, and nearly all these admissions were for DKA or high ketones. Despite some of the risks associated with pump use, our data suggest that insulin pump use may mitigate against DKA requiring hospital admission (13). Since insulin pumps may also provide increased convenience and accuracy in type 1 diabetes management, disparities in reach and uptake of diabetes technologies are a critical area of needed research.

The prevalence of hypoglycemia and soft tissue infection admissions were low across all groups. Patients with type 1 diabetes are generally at increased risk for acute infections (25), and since insulin pump use requires a subcutaneous catheter, the risk for soft tissue infections may be increased (26). However, advancements in infusion set changing procedures and recommended hygiene practices have significantly reduced the rate of these infections (27). In our study, the lowest prevalence of soft tissue infection occurred in those who were admitted with pump failure, suggesting that local infections at insulin pump infusion sites may not be a significant contributor to pump failure. Our 2.5% overall prevalence of soft tissue infections among youth with type 1 diabetes admissions was consistent with the prevalence reported in an analysis of the Pediatric Health Information System database (25). This study did not evaluate whether soft tissue infections differed by insulin pump use.

Severity of illness was most often in the minor to moderate category across all admission groups. There was a slight predominance of moderate to major severity of illness admissions in those admitted with pump failure. This may be related to increase resource intensity associated with managing an insulin pump in the inpatient setting. Despite having a higher severity of illness, those admitted with pump failure had the lowest LOS and admission cost. This may be due to the fact that those with insulin pump failure are likely admitted with DKA without other acute issues, whereas other pump users or those without insulin pump use may have more complex clinical presentations (eg, multiple acute medical issues). This is supported by the higher prevalence of nonroutine discharges (eg, transfer to other facilities at discharge, use of home healthcare, etc). Additionally, given those admitted without insulin pump use are more likely to be of lower socioeconomic status, LOS may be prolonged in the setting of addressing pertinent social issues that may result in more complex discharge planning (28).

Our study has some limitations. The use of billing codes to establish diagnoses and determine insulin pump status has the potential for inaccuracies in classification. As previously discussed, the low prevalence of inpatient admissions with insulin pump use may reflect undercoding for insulin pump use, and so these findings may underrepresent the true prevalence of insulin pump admissions. It is also unclear how the switch from ICD-9 to ICD-10 may have influenced coding practices for type 1 diabetes admissions and for pump use specifically. Furthermore, the results of this study may not be generalizable to other countries with differing structures of healthcare (eg, universal healthcare).

In this study, were unable to evaluate trends in hospitalizations based on insulin pump type, this is relevant in the setting of the advances in technology and wide range of pump systems that have become available during this decade and its subsequent impact on diabetes management. We are also unable to evaluate whether continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) use modified the prevalence and type of admissions that occur among insulin pump users. While there are several ICD codes that may identify an insulin pump user in claims data, there are currently no CGM-related ICD codes available. As administrative data such as KID are premier tools for large-scale investigations in health services research, it is critically important to improve documentation of diabetes technology use so that these treatment regimens will be correctly identified in future work. Especially as the use of CGM systems has also expanded in recent years, accurate documentation of both CGM and pump use will be critical for facilitating investigations into the impact of these devices on service use and diabetes outcomes nationally.

Conclusion

Inpatient admissions in youth who are insulin pump users are increasing over time but appear to account for a minority of type 1 diabetes admissions overall. Admissions among pump users displayed some unique features, such as fewer concurrent DKA diagnoses, higher severity of illness, and lower LOS and inpatient healthcare utilization. The prevalence of insulin pump admissions may be underestimated due to undercoding of insulin pump use in inpatient administrative data. Improved accuracy in coding practices or other approaches to identify insulin pump users in administrative data are needed to ensure we can appropriately evaluate the implications of rising technology use on the frequency and severity of acute hospitalizations nationally and its impact on healthcare expenditures and health outcomes.

Financial Support

We wish to acknowledge the generous funding support from the National Institute of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) K01DK116932 (principal investigator: L.E.W.). T.M. also receives support from the NIH/NIDDK (R01DK124503, R01DK127733, and R18DK122372), NIH/NIDDK/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U18DP006535), the Department of Veterans Affairs (QUE20-028 and CSP2002), and from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI; SDM-2018C2-13543). E.M.E. would like to acknowledge support from NIH/NIDDK Pediatric Loan Repayment Program Award (L40DK129996).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author Contributions

E.M.E. conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. T.P.C. analyzed and interpreted the data and reviewed and revised the manuscript. T.M. conceptualized and designed the study, interpreted the data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. L.E.W. conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosures

Authors have no relevant conflict of interests, including specific financial interests, relationships, and affiliations relevant to the subject of this manuscript to disclose.

Data Availability

Some or all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in the references.

References

- 1. Schmitt J, Scott ML. Insulin degludec in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: is newer better? A retrospective self-control case series in adolescents with a history of diabetic ketoacidosis. Horm Res Paediatr. 2019;92(3):179-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thalange N, Deeb L, Klingensmith G, et al. . The rate of hyperglycemia and ketosis with insulin degludec-based treatment compared with insulin detemir in pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes: an analysis of data from two randomized trials. Pediatr Diabetes. 2019;20(3):314-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guilhem I, Leguerrier AM, Lecordier F, Poirier JY, Maugendre D. Technical risks with subcutaneous insulin infusion. Diabetes Metab. 2006;32(3):279-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berg AK, Thorsen SU, Thyssen JP, Zachariae C, Keiding H, Svensson J. Cost of treating skin problems in patients with diabetes who use insulin pumps and/or glucose sensors. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2020;22(9):658-665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Van Den Boom L, Karges B, Auzanneau M, et al. . Temporal trends and contemporary use of insulin pump therapy and glucose monitoring among children, adolescents, and adults with type 1 diabetes between 1995 and 2017. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(11):2050-2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Everett EM, Copeland TP, Moin T, Wisk LE. National trends in pediatric admissions for diabetic ketoacidosis, 2006-2016. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(8):2343-2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. HCUP-KID overview. ProMED-mail website. Accessed May 29, 2020. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/kidoverview.jsp

- 8. Everett EM, Copeland TP, Moin T, Wisk LE.Supplemental data for: Insulin pump related admissions in a national sample of youth with type 1 diabetes. FigShare. Deposited February 14, 2022. Doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.16869107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Averill AF, Goldfield N, Hughes JS, et al. . All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRGs) methodology overview. 3M Health Information Systems. 2003. ProMED-mail website. Accessed September 1, 2021. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/APR-DRGsV20MethodologyOverviewandBibliography.pdf

- 10. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index. 2021. ProMED-mail website. Accessed August 25, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/

- 11. Lipman TH, Willi SM, Lai CW, Smith JA, Patil O, Hawkes CP. Insulin pump use in children with type 1 diabetes: over a decade of disparities. J Pediatr Nurs. 2020;55:110-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Willi SM, Miller KM, DiMeglio LA, et al. . Racial-ethnic disparities in management and outcomes among children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):424-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O’Reilly JE, Jeyam A, Caparrotta TM, et al. . Rising rates and widening socioeconomic disparities in diabetic ketoacidosis in type 1 diabetes in Scotland: a nationwide retrospective cohort observational study. Diabetes Care. 2021:44(9):2010-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Paris CA, Imperatore G, Klingensmith G, et al. . Predictors of insulin regimens and impact on outcomes in youth with type 1 diabetes: the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study J Pediatr. 2009;155(2):183-189.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O’Connor MR, Carlin K, Coker T, et al. . Disparities in insulin pump therapy persist in youth with type 1 diabetes despite rising overall pump use rates. J Pediatr Nurs. 2019;44:16-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Everett E, Copeland T, Moin T, Wisk L. National trends in pediatric admissions for diabetic ketoacidosis, 2006-2016. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(8):2343-2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17. Benoit SR, Zhang Y, Geiss LS, Gregg EW, Albright A. Trends in diabetic ketoacidosis hospitalizations and in-hospital mortality—United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(12):362-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Desai D, Mehta D, Mathias P, Menon G, Schubart UK. Health care utilization and burden of diabetic ketoacidosis in the U.S. over the past decade: a nationwide analysis. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(8):1631-1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Everett E, Mathioudakis N. Association of socioeconomic status and DKA readmission in adults with type 1 diabetes: analysis of the US National Readmission Database. BMJ Open Diab Res Care. 2019;7:e000621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Everett E, Mathioudakis N. Association of area deprivation and diabetic ketoacidosis readmissions: comparative risk analysis of adults vs children with type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:3473-3480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Karges B, Schwandt A, Heidtmann B, et al. . Association of insulin pump therapy vs insulin injection therapy with severe hypoglycemia, ketoacidosis, and glycemic control among children, adolescents, and young adults with type 1 diabetes. JAMA. 2017;318(14):1358-1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hoshina S, Andersen GS, Jørgensen ME, Ridderstråle M, Vistisen D, Andersen HU. Treatment modality-dependent risk of diabetic ketoacidosis in patients with type 1 diabetes: Danish Adult Diabetes Database Study. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2018;20(3):229-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pala L, Dicembrini I, Mannucci E. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion vs modern multiple injection regimens in type 1 diabetes: an updated meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Acta Diabetol. 2019;56(9):973-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ross P, Gray A, Milburn J, et al. . Insulin pump-associated adverse events are common, but not associated with glycemic control, socio-economic status, or pump/infusion set type. Acta Diabetol. 2016;53(6):991-998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Korbel L, Easterling RS, Punja N, Spencer JD. The burden of common infections in children and adolescents with diabetes mellitus: a Pediatric Health Information System study. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19(3):512-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang E, Cao Z. Tissue response to subcutaneous infusion catheter. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2019;14(2):226-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Berg AK, Nørgaard K, Thyssen JP, et al. . Skin problems associated with insulin pumps and sensors in adults with type 1 diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2018;20(7):475-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ghosh AK, Geisler BP, Ibrahim S. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic variations in hospital length of stay: a state-based analysis. Medicine (Baltim). 2021;100(20):e25976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in the references.