Abstract

Background

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) dates back to December 2019 in China. Iran has been among the most prone countries to the virus. The aim of this study was to report demographics, clinical data, and their association with death and CFR.

Methods

This observational cohort study was performed from 20th March 2020 to 18th March 2021 in three tertiary educational hospitals in Tehran, Iran. All patients were admitted based on the WHO, CDC, and Iran's National Guidelines. Their information was recorded in their medical files. Multivariable analysis was performed to assess demographics, clinical profile, outcomes of disease, and finding the predictors of death due to COVID-19.

Results

Of all 5318 participants, the median age was 60.0 years, and 57.2% of patients were male. The most significant comorbidities were hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Cough, dyspnea, and fever were the most dominant symptoms. Results showed that ICU admission, elderly age, decreased consciousness, low BMI, HTN, IHD, CVA, dialysis, intubation, Alzheimer disease, blood injection, injection of platelets or FFP, and high number of comorbidities were associated with a higher risk of death related to COVID-19. The trend of CFR was increasing (WPC: 1.86) during weeks 25 to 51.

Conclusions

Accurate detection of predictors of poor outcomes helps healthcare providers in stratifying patients, based on their risk factors and healthcare requirements to improve their survival chance.

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was officially announced as a pandemic and public health emergence following the first case detected in China in December 2019 and spread rapidly around the world [1]. At the outset, fever and respiratory symptoms were considered as the major symptoms of this novel virus [2]. Over time, the virus caused several clinical manifestations varying from asymptomatic or mild constitutional symptoms to life-threatening conditions leading to hospitalization and even death [3].

Iran has been among the most prone countries to the virus, especially in the Middle East [4–7]. Approximately 3 851 162 COVID-19 patients and 90 344 deaths (mortality rate: 2.34%) have been recorded in Iran until July 30, 2021 [8].

The sudden rise in requisition for healthcare services brings an overload to private and public health systems that require urgent attention to improve optimal services to COVID-19 patients. As a result, the evaluation of the most common risk factors of mortality, length of hospital stay, and outcome of COVID-19 has become crucial to guide healthcare professionals in decision-making and get the most out of their skills and facilities to immediately detect cases and evaluate the course of infection and to improve treatment outcomes and reduce virus transmission and mortality rates [9–14]. Multiple studies have reported the association of patients' medical records such as demographics, clinical manifestations, and disease outcome, to the COVID-19 pandemic progression to recognize the risk factors of hospitalization and mortality due to SARS-CoV-2 [15–19]. A review article of Wynants et al. demonstrated the relation of age, sex, comorbidities, and serum biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), creatinine, lymphocyte count, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) with increased mortality risk [18].

Obviously, the patients' epidemiology varies in different countries in the matters of population demographic data, genetic, the prevalence of comorbidities, and health care systems [20]. To the best of our knowledge, limited studies estimated the case fatality rate (CFR) of this outbreak in Iran. The case fatality rate is a value of the ability of a virus to damage a host and represents the proportion of death from a specified disease among all diagnosed cases during the exact period of time [21]. The CFR is one of the substantial parameters to estimate the basic epidemiological features of the outbreak and the severity of disease and is also essential for public health services in approaches to reduce the risk of disease [22]. Our study evaluates the CFR of COVID-19 since the outset of the pandemic in Iran.

The purpose of this retrospective study was to investigate the epidemiology, clinical outcomes, therapeutic protocols, and the potential risk factors of in-hospital mortality of the COVID-19 cases from academic and referral health care centers in Tehran, the most populous city in Iran, since the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic. Besides, this study is aimed at calculating CFR to hopefully provide successful guidelines to block transmission of SARS-CoV-2, early detection of severe cases, and perform effective therapeutic guidelines.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

In this retrospective study, confirmed COVID-19 patients admitted to three university hospitals (including Taleghani hospital, Imam Hussein hospital, and Shohadaye Tajrish hospital) in Tehran, Iran, were enrolled from 20 March 2020 until 18 March 2021. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab samples was performed to confirm COVID-19 cases on the first days of admission. The medical team gathered demographics, comorbidities, triage vital signs, patient outcomes, inpatient treatment protocol, and laboratory data through the hospital information system.

2.2. Patient's Characteristic, Treatment, and Outcome

A medical team collected demographic data (age, sex, body mass index), presenting symptoms, symptom onset to admission interval (days), comorbidities, habitual history (smoking, alcohol, opium, hookah), and triage vital signs (pulse rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation without supplementary oxygen, oxygen saturation with supplementary oxygen, body temperature measure by infrared thermometer) from electronic medical records. Inpatient medication and treatment protocol were retrieved from the nursing notes. Outcomes were determined as death versus survived, ICU admission versus ward admission, invasive mechanical ventilation, and length of admission.

2.3. Laboratory Data

Laboratory values during the admission were gathered from the hospital information system and sorted using the Python program (Python Software Foundation. Python Language Reference, version 2.7. Available at http://www.python.org). Some parameters were gathered during the first six days of admission, if available. For other laboratory data, the earliest valid value is considered.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented using mean ± SD and frequency (percentage) for continuous and categorical data, respectively. Bar charts were also used to display summary statistics such as frequency or percentage by demographic or outcome variables. In order to examine the relationship between outcome and explanatory variables, Pearson chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used. The measure of association between outcome and variables was assessed by Cramer's V and Eta. The Kaplan-Meier estimator was used to estimate the survival function. The logrank test was used to compare the risk of death in different categories of a variable. Weekly percent change (WPC) has been used to evaluate the rate of change or trend in CFR each week between the 3rd week and the 50th week of the study. All analyzes were performed by SPSS (version 26), R (4.0.2), and Joinpoint regression (4.9.0.0). p values less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

2.5. Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.RIGLD.REC.004), and IRB exempted this study from informed consent. Data were anonymized before analysis; patients' confidentiality and data security were concerned at all levels, and the study was completed under the Helsinki Declaration (2013) guidelines.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic, Clinical Characteristics, and Outcome of Patients

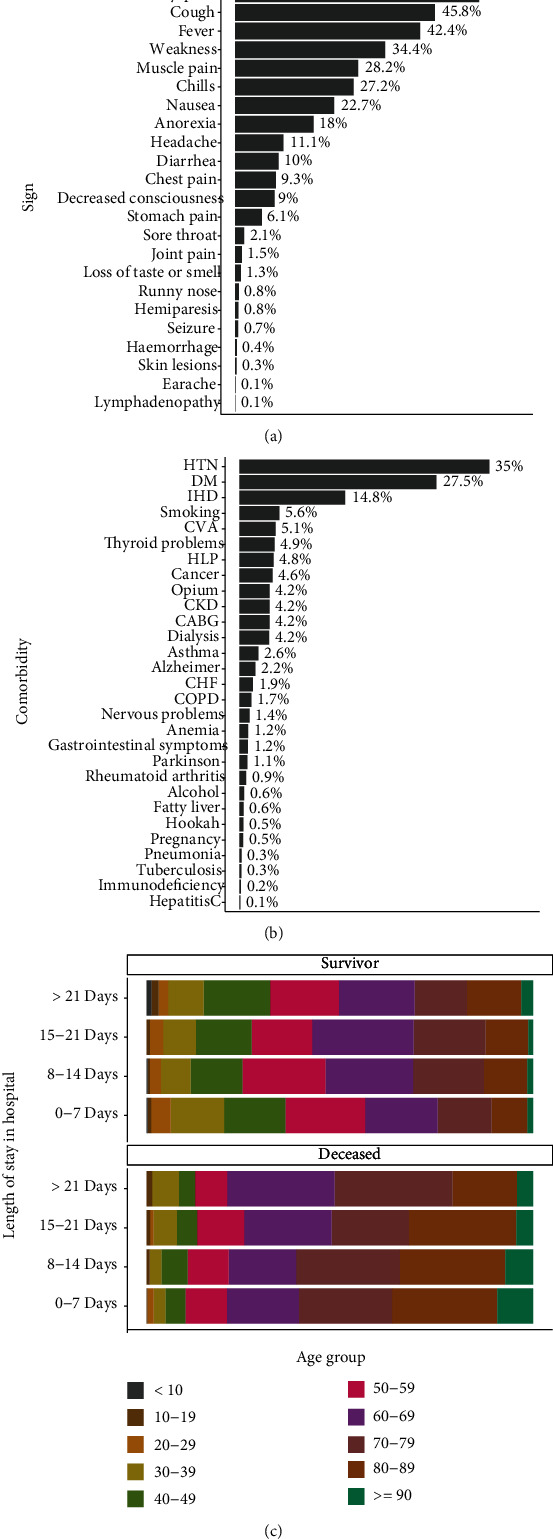

A total of 5 318 patients were included in this study (3 042 males and 2 276 females) with a median age of 60.0 (Q1, Q3, 46.0, 74.0) years old. Patients' clinical characteristics and outcomes were summarized in Table 1. Twenty-one percent (n = 1112) of patients with COVID-19 were deceased. The median age among deceased patients was significantly higher than that of in the survivor group (73.0 vs. 57.0 years, p < 0.001). The association between sex and death was not significant (p = 0.151). Among variables with significant relation with death, the strength of the relationship between death and variables including intubation (Cramer's V = 0.45), oxygen saturation (Eta = 0.32), O2 saturation with ventilator (Eta = 0.30), age (Cramer's V = 0.30), and decreased consciousness (Cramer's V = 0.27) was highest. As shown in Table 1 and Figures 1(a) and 1(b), the main symptoms at admission were dyspnea, cough, fever, weakness, muscle pain, chills, and nausea, respectively. HTN, DM, and IHD were common comorbidities. The age percentage by death status and length of stay in hospital is shown Figure 1(c). Accordingly, among the patients who died, those older than 60 years accounted for approximately 75% of the cases in various categories of the length of hospital stay.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for treatment of COVID-19 in hospitals in Tehran.

| Variables | Total (n = 5318) | Survivor (n = 4204) | Deceased (n = 1112) | Cramer's V/Eta | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 60.0 (46.0, 74.0) | 57.0 (43.0, 70.0) | 73.0 (61.0, 83.0) | 0.30 | <0.001 | |

| BMI | 26.3 (23.9, 29.4) | 26.4 (24.0, 29.6) | 26.0 (22.9, 29.4) | 0.05 | 0.028 | |

| Sex | Male | 3042 (57.20) | 2383 (56.68) | 657 (59.08) | 0.02 | 0.151 |

| Female | 2276 (42.80) | 1821 (43.32) | 455 (40.92) | |||

| Cough | No | 2884 (54.23) | 2227 (52.97) | 656 (58.99) | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 2434 (45.77) | 1977 (47.03) | 456 (41.01) | |||

| Dyspnea | No | 2342 (44.04) | 1906 (45.34) | 436 (39.21) | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 2975 (55.94) | 2297 (54.64) | 676 (60.79) | |||

| Fever | No | 3064 (57.62) | 2378 (56.57) | 685 (61.60) | 0.04 | 0.003 |

| Yes | 2254 (42.38) | 1826 (43.43) | 427 (38.40) | |||

| Chills | No | 3872 (72.81) | 3023 (71.91) | 848 (76.26) | 0.014 | 0.004 |

| Yes | 1445 (27.17) | 1180 (28.07) | 264 (23.74) | |||

| Muscle pain | No | 3818 (71.79) | 2921 (69.48) | 895 (80.49) | 0.1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1498 (28.17) | 1282 (30.49) | 216 (19.42) | |||

| Weakness | No | 3486 (65.55) | 2821 (67.10) | 664 (59.71) | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1829 (34.39) | 1381 (32.85) | 447 (40.20) | |||

| Decreased consciousness | No | 4836 (90.94) | 3990 (94.91) | 844 (75.90) | 0.27 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 481 (9.04) | 213 (5.07) | 268 (24.10) | |||

| Sore throat | No | 5207 (97.91) | 4110 (97.76) | 1095 (98.47) | 0.02 | 0.142 |

| Yes | 111 (2.09) | 94 (2.24) | 17 (1.53) | |||

| Runny nose | No | 5273 (99.15) | 4169 (99.17) | 1102 (99.10) | 0 | 0.829 |

| Yes | 45 (0.85) | 35 (0.83) | 10 (0.90) | |||

| Loss of taste or smell | No | 5247 (98.66) | 4138 (98.43) | 1107 (99.55) | 0.04 | 0.004 |

| Yes | 71 (1.34) | 66 (1.57) | 5 (0.45) | |||

| Nausea | No | 4109 (77.27) | 3202 (76.17) | 905 (81.38) | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1208 (22.72) | 1001 (23.81) | 207 (18.62) | |||

| Anorexia | No | 4358 (81.95) | 3437 (81.76) | 921 (82.82) | 0.01 | 0.427 |

| Yes | 958 (18.01) | 765 (18.20) | 191 (17.18) | |||

| Diarrhea | No | 4788 (90.03) | 3755 (89.32) | 1031 (92.72) | 0.05 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 530 (9.97) | 449 (10.68) | 81 (7.28) | |||

| Chest pain | No | 4821 (90.65) | 3784 (90.01) | 1035 (93.08) | 0.04 | 0.002 |

| Yes | 497 (9.35) | 420 (9.99) | 77 (6.92) | |||

| Lymphadenopathy | No | 5315 (99.94) | 4201 (99.93) | 1112 (100.00) | 0.01 | 0.373 |

| Yes | 3 (0.06) | 3 (0.07) | 0 (0.00) | |||

| Skin lesions | No | 5300 (99.66) | 4196 (99.81) | 1102 (99.10) | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 18 (0.34) | 8 (0.19) | 10 (0.90) | |||

| Joint pain | No | 5237 (98.48) | 4140 (98.48) | 1095 (98.47) | 0 | 0.988 |

| Yes | 81 (1.52) | 64 (1.52) | 17 (1.53) | |||

| Headache | No | 4729 (88.92) | 3686 (87.68) | 1041 (93.62) | 0.08 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 588 (11.06) | 517 (12.30) | 71 (6.38) | |||

| Stomach pain | No | 4993 (93.89) | 3946 (93.86) | 1045 (93.97) | 0 | 0.89 |

| Yes | 325 (6.11) | 258 (6.14) | 67 (6.03) | |||

| Earache | No | 5311 (99.87) | 4198 (99.86) | 1111 (99.91) | 0.01 | 0.666 |

| Yes | 7 (0.13) | 6 (0.14) | 1 (0.09) | |||

| Haemorrhage | No | 5298 (99.62) | 4193 (99.74) | 1103 (99.19) | 0.04 | 0.008 |

| Yes | 20 (0.38) | 11 (0.26) | 9 (0.81) | |||

| Hemiparesis | No | 3976 (74.76) | 3128 (74.41) | 847 (76.17) | 0.01 | 0.391 |

| Yes | 41 (0.77) | 30 (0.71) | 11 (0.99) | |||

| Pregnancy | No | 3991 (75.05) | 3134 (74.55) | 856 (76.98) | 0.03 | 0.076 |

| Yes | 27 (0.51) | 25 (0.59) | 2 (0.18) | |||

| Smoking | No | 5020 (94.40) | 3973 (94.51) | 1045 (93.97) | 0.01 | 0.494 |

| Yes | 298 (5.60) | 231 (5.49) | 67 (6.03) | |||

| Alcohol | No | 5284 (99.36) | 4181 (99.45) | 1101 (99.01) | 0.02 | 0.100 |

| Yes | 34 (0.64) | 23 (0.55) | 11 (0.99) | |||

| Opium | No | 5092 (95.75) | 4029 (95.84) | 1061 (95.41) | 0.01 | 0.619 |

| Yes | 225 (4.23) | 175 (4.16) | 50 (4.50) | |||

| Hookah | No | 5289 (99.45) | 4181 (99.45) | 1106 (99.46) | 0 | 0.976 |

| Yes | 29 (0.55) | 23 (0.55) | 6 (0.54) | |||

| HTN | No | 3456 (64.99) | 2850 (67.79) | 604 (54.32) | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1861 (34.99) | 1353 (32.18) | 508 (45.68) | |||

| IHD | No | 4532 (85.22) | 3677 (87.46) | 853 (76.71) | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 786 (14.78) | 527 (12.54) | 259 (23.29) | |||

| CABG | No | 5094 (95.79) | 4057 (96.50) | 1035 (93.08) | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 224 (4.21) | 147 (3.50) | 77 (6.92) | |||

| CHF | No | 5218 (98.12) | 4141 (98.50) | 1075 (96.67) | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 100 (1.88) | 63 (1.50) | 37 (3.33) | |||

| Asthma | No | 5178 (97.37) | 4091 (97.31) | 1085 (97.57) | 0.01 | 0.63 |

| Yes | 140 (2.63) | 113 (2.69) | 27 (2.43) | |||

| COPD | No | 5228 (98.31) | 4138 (98.43) | 1088 (97.84) | 0.02 | 0.248 |

| Yes | 89 (1.67) | 66 (1.57) | 23 (2.07) | |||

| DM | No | 3852 (72.43) | 3145 (74.81) | 705 (63.40) | 0.1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1465 (27.55) | 1058 (25.17) | 407 (36.60) | |||

| Pneumonia | No | 5301 (99.68) | 4195 (99.79) | 1104 (99.28) | 0.04 | 0.008 |

| Yes | 17 (0.32) | 9 (0.21) | 8 (0.72) | |||

| CVA | No | 5048 (94.92) | 4047 (96.27) | 999 (89.84) | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 269 (5.06) | 156 (3.71) | 113 (10.16) | |||

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | No | 5255 (98.82) | 4157 (98.88) | 1096 (98.56) | 0.01 | 0.379 |

| Yes | 63 (1.18) | 47 (1.12) | 16 (1.44) | |||

| CKD | No | 5093 (95.77) | 4054 (96.43) | 1037 (93.26) | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 225 (4.23) | 150 (3.57) | 75 (6.74) | |||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | No | 5269 (99.08) | 4169 (99.17) | 1098 (98.74) | 0.02 | 0.186 |

| Yes | 49 (0.92) | 35 (0.83) | 14 (1.26) | |||

| Cancer | No | 5047 (94.90) | 4028 (95.81) | 1017 (91.46) | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 247 (4.64) | 162 (3.85) | 85 (7.64) | |||

| HLP | No | 5062 (95.19) | 4000 (95.15) | 1060 (95.32) | 0 | 0.831 |

| Yes | 255 (4.80) | 203 (4.83) | 52 (4.68) | |||

| Hepatitis C | No | 5310 (99.85) | 4198 (99.86) | 1110 (99.82) | 0.01 | 0.619 |

| Yes | 7 (0.13) | 5 (0.12) | 2 (0.18) | |||

| Thyroid problems | No | 5048 (94.92) | 3991 (94.93) | 1055 (94.87) | 0 | 0.949 |

| Yes | 261 (4.91) | 206 (4.90) | 55 (4.95) | |||

| Immunodeficiency | No | 5307 (99.79) | 4194 (99.76) | 1111 (99.91) | 0.01 | 0.334 |

| Yes | 11 (0.21) | 10 (0.24) | 1 (0.09) | |||

| Seizure | No | 5255 (98.82) | 4156 (98.86) | 1097 (98.65) | 0.01 | 0.570 |

| Yes | 63 (1.18) | 48 (1.14) | 15 (1.35) | |||

| Tuberculosis | No | 5303 (99.72) | 4192 (99.71) | 1109 (99.73) | 0 | 0.930 |

| Yes | 15 (0.28) | 12 (0.29) | 3 (0.27) | |||

| Anemia | No | 5252 (98.76) | 4153 (98.79) | 1097 (98.65) | 0 | 0.484 |

| Yes | 64 (1.20) | 50 (1.19) | 14 (1.26) | |||

| Fatty liver | No | 5287 (99.42) | 4177 (99.36) | 1108 (99.64) | 0.02 | 0.271 |

| Yes | 31 (0.58) | 27 (0.64) | 4 (0.36) | |||

| Nervous problems | No | 5235 (98.44) | 4146 (98.62) | 1087 (97.75) | 0.03 | 0.036 |

| Yes | 75 (1.41) | 52 (1.24) | 23 (2.07) | |||

| Parkinson | No | 5260 (98.91) | 4176 (99.33) | 1082 (97.30) | 0.08 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 58 (1.09) | 28 (0.67) | 30 (2.70) | |||

| Alzheimer | No | 5200 (97.78) | 4153 (98.79) | 1045 (93.97) | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 118 (2.22) | 51 (1.21) | 67 (6.03) | |||

| Dialysis | No | 5097 (95.84) | 4108 (97.72) | 987 (88.76) | 0.18 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 221 (4.16) | 96 (2.28) | 125 (11.24) | |||

| Blood injection | No | 4791 (90.09) | 3909 (92.98) | 881 (79.23) | 0.19 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 522 (9.82) | 292 (6.95) | 229 (20.59) | |||

| Injection of platelets or fresh frozen plasma (FFP) | No | 5188 (97.56) | 4145 (98.60) | 1041 (93.62) | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 130 (2.44) | 59 (1.40) | 71 (6.38) | |||

| Intubation | No | 4883 (91.82) | 4126 (98.14) | 755 (67.90) | 0.45 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 432 (8.12) | 75 (1.78) | 357 (32.10) | |||

| Number of days hospitalized in the hospital emergency department | — | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | 0.04 | 0.159 |

| Number of days hospitalized in the hospital general department | — | 5.0 (2.0, 9.0) | 5.0 (2.0, 9.0) | 4.0 (1.0, 8.0) | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Number of days hospitalized in the hospital ICU department | — | 4.0 (2.0, 8.0) | 5.0 (2.0, 9.0) | 4.0 (1.0, 8.0) | 0.02 | 0.035 |

| Oxygen saturation | — | 90.0 (85.0, 93.0) | 90.0 (86.0, 94.0) | 85.0 (76.0, 90.0) | 0.32 | <0.001 |

| O2 saturation with ventilator | — | 95.0 (92.0, 98.0) | 96.0 (93.0, 98.0) | 93.0 (88.0, 97.0) | 0.30 | <0.001 |

| Pulse rate | — | 85.0 (80.0, 95.0) | 85.0 (80.0, 93.0) | 88.0 (80.0, 100.0) | 0.08 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic pressure | — | 80.0 (70.0, 80.0) | 80.0 (70.0, 80.0) | 75.0 (70.0, 80.0) | 0.02 | 0.007 |

| Systolic pressure | — | 120.0 (110.0, 130.0) | 120.0 (110.0, 130.0) | 120.0 (100.0, 130.0) | 0.03 | 0.001 |

| Respiratory rate | — | 18.0 (17.0, 20.0) | 18.0 (17.0, 20.0) | 19.0 (18.0, 22.0) | 0.10 | <0.001 |

| Body temperature | — | 37.0 (36.9, 37.5) | 37.0 (36.9, 37.5) | 37.0 (36.8, 37.5) | 0.01 | 0.653 |

The Cramer's V test was used to measure the association between categorical variables and status. The value of Cramer's V indicates how strongly two categorical variables are associated, giving a value between 0 and +1. For numeric variables, the Mann–Whitney test was used to compare median values between survivors and deceased cases. Eta was used to measure the association of numeric variables with status, giving a value between 0 and 1. In both Cramer's V and Eta, values close to 1 indicating a high degree of association. The missing values were ignored in calculation of percentages. The median (Q1, Q3) and frequency (%) were used for describing the numeric and categorical variables, respectively.

Figure 1.

The percentage of (a) sign, (b) comorbidity, and (c) deceased patients by age group and length of stay in hospital.

3.2. Clinical Laboratory Data

In the next step, we investigated the ranges of laboratory data between deceased and survived patients, which are summarized in Table 2 (see Table S1 in the Supplementary File).

Table 2.

Laboratory statistics of COVID-19 patients in Tehran.

| Variables | Total (n = 5318) | Survivor (n = 4204) | Deceased (n = 1112) | Cramer's V/Eta | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (×103/μL) | — | 7.3 (5.2, 10.5) | 6.9 (5.0, 9.7) | 9.1 (6.2, 13.2) | 0.17 | <0.001 |

| Lymphs (%) | — | 15.6 (10.0, 24.9) | 17.9 (11.0, 25.4) | 10.1 (7.1, 17.1) | 0.22 | <0.001 |

| NEUT (%) | — | 79.5 (70.0, 85.0) | 76.9 (68.0, 85.0) | 85.0 (77.4, 90.0) | 0.23 | <0.001 |

| PLT (×103/μL) | — | 194.0 (150.0, 255.0) | 196.0 (152.0, 254.0) | 186.0 (138.5, 259.0) | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| HB (g/dL) | — | 12.4 (10.9, 13.7) | 12.5 (11.1, 13.8) | 11.9 (10.1, 13.3) | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| MCV (μm3) | — | 84.6 (80.5, 88.3) | 84.3 (80.4, 88.0) | 85.7 (80.7, 89.7) | — | <0.001 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | — | 19.0 (13.0, 31.0) | 17.0 (12.0, 26.0) | 29.0 (18.3, 48.8) | 0.29 | <0.001 |

| CR (mg/dL) | — | 1.1 (1.0, 1.5) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.4) | 1.4 (1.1, 2.2) | 0.19 | <0.001 |

| NA (mEq/L) | — | 138.0 (135.0, 141.0) | 138.0 (135.0, 140.0) | 138.0 (135.0, 141.0) | 0.04 | 0.031 |

| K (mEq/L) | — | 4.1 (3.8, 4.4) | 4.1 (3.8, 4.4) | 4.2 (3.9, 4.7) | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| CA (mg/dL) | — | 8.6 (8.1, 9.3) | 8.7 (8.2, 9.3) | 8.5 (8.0, 9.1) | 0.09 | <0.001 |

| MG (mEq/L) | — | 1.9 (1.7, 2.2) | 1.9 (1.7, 2.1) | 2.0 (1.8, 2.2) | 0.08 | <0.001 |

| P (mg/dL) | — | 3.5 (2.9, 4.1) | 3.4 (2.9, 4.0) | 3.8 (3.1, 4.7) | 0.22 | <0.001 |

| AST (U/L) | — | 36.0 (24.0, 55.0) | 34.0 (23.4, 50.0) | 44.9 (29.0, 72.0) | 0.09 | <0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | — | 28.0 (18.0, 46.0) | 27.1 (18.0, 45.0) | 30.0 (18.0, 50.4) | 0.07 | 0.021 |

| ALKP (U/L) | — | 185.0 (138.0, 257.0) | 181.0 (136.0, 248.0) | 205.0 (148.0, 287.0) | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| BILLT (mg/dL) | — | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.2) | 0.11 | <0.001 |

| BILLD (mg/dL) | — | 0.3 (0.2, 0.4) | 0.3 (0.2, 0.4) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.5) | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Amylase (U/L) | — | 53.0 (38.8, 76.8) | 54.0 (40.0, 75.8) | 49.9 (34.0, 80.0) | 0.0 | 0.164 |

| LIPASE (U/L) | — | 26.0 (19.0, 38.0) | 26.0 (19.0, 38.0) | 25.0 (17.6, 38.0) | 0.01 | 0.559 |

| TG (mg/dL) | — | 120.0 (90.0, 168.0) | 119.0 (90.0, 168.0) | 123.0 (87.8, 173.0) | 0.01 | 0.957 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | — | 130.0 (106.0, 158.0) | 133.5 (110.0, 161.0) | 119.5 (96.8, 148.0) | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | — | 31.0 (28.0, 40.0) | 32.0 (28.0, 40.0) | 30.1 (26.0, 38.0) | 0.04 | 0.053 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | — | 73.0 (54.0, 95.0) | 75.0 (58.0, 98.0) | 65.0 (48.0, 84.0) | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| FBS (mg/dL) | — | 135.0 (104.0, 194.0) | 131.0 (103.0, 188.0) | 146.0 (109.8, 207.3) | 0.06 | 0.001 |

| HBA1C (% of total Hb) | — | 7.5 (6.4, 9.9) | 7.5 (6.4, 10.0) | 7.6 (6.4, 9.5) | 0.03 | 0.527 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | — | 3.8 (3.4, 4.2) | 3.9 (3.5, 4.3) | 3.5 (3.1, 3.9) | 0.28 | <0.001 |

| LDH (U/L) | — | 576.0 (439.0, 800.0) | 547.5 (421.8, 745.0) | 711.0 (520.5, 1072.0) | 0.24 | <0.001 |

| CRP (mg/L) | — | 29.7 (10.5, 69.1) | 26.8 (10.0, 64.0) | 43.4 (15.0, 86.0) | — | <0.001 |

| ESR (mm/h) | — | 34.0 (18.0, 56.0) | 32.0 (18.0, 56.0) | 36.0 (20.0, 59.0) | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Lactate | — | 20.0 (15.0, 27.0) | 19.1 (15.0, 25.9) | 22.0 (16.0, 33.0) | 0.20 | <0.001 |

| IL6 (pg/mL) | — | 25.6 (10.9, 70.2) | 18.5 (8.1, 44.8) | 46.6 (16.1, 146.0) | 0.33 | 0.004 |

| CPK (U/L) | — | 117.0 (63.0, 257.0) | 108.0 (61.0, 232.0) | 150.0 (77.5, 356.5) | 0.08 | <0.001 |

| CKMB (U/L) | — | 21.0 (14.0, 33.0) | 20.0 (14.0, 30.0) | 25.0 (17.0, 45.0) | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| PROBNP (pg/mL) | — | 868.0 (173.8, 3792.8) | 469.0 (132.0, 2313.0) | 3200.0 (894.0, 9987.0) | 0.32 | <0.001 |

| Procalcitonin (pg/mL) | — | 0.4 (0.2, 1.3) | 0.3 (0.2, 0.9) | 0.9 (0.3, 2.6) | 0.08 | <0.001 |

| PTT (s) | — | 30.0 (25.6, 35.0) | 30.0 (25.3, 35.0) | 32.0 (26.7, 38.0) | 0.09 | <0.001 |

| PT (s) | — | 13.0 (11.9, 13.7) | 13.0 (11.7, 13.3) | 13.0 (12.4, 14.6) | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| INR | — | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.3) | 0.16 | <0.001 |

| pH | — | 7.4 (7.3, 7.4) | 7.4 (7.3, 7.4) | 7.4 (7.3, 7.4) | 0.08 | <0.001 |

| PCO2 (mm Hg) | — | 44.3 (38.7, 50.0) | 44.6 (39.3, 50.1) | 42.7 (36.3, 49.8) | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| HCO3 (mEq/L) | — | 25.8 (22.7, 28.6) | 26.2 (23.5, 28.9) | 23.8 (20.2, 27.3) | 0.20 | <0.001 |

| BE (mmol/L) | — | 1.6 (-1.6, 4.4) | 2.0 (-0.7, 4.6) | -0.4 (-5.2, 3.0) | 0.21 | <0.001 |

| ANCA (AU/mL) | — | 1.5 (0.9, 8.8) | 1.6 (1.0, 12.4) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | 0.27 | 0.480 |

| CANCA (AU/mL) | — | 2.4 (1.8, 4.0) | 2.1 (1.4, 3.0) | 3.6 (2.7, 6.3) | 0.19 | 0.015 |

| PANCA (AU/mL) | — | 2.9 (1.7, 4.5) | 2.9 (1.7, 4.4) | 2.8 (1.7, 4.8) | 0.09 | 0.883 |

| FDP (mug/mL) | — | 6.5 (4.0, 12.0) | 5.9 (4.0, 9.4) | 12.0 (6.2, 18.0) | 0.30 | <0.001 |

| Fe (μg/dL) | — | 43.0 (25.0, 80.0) | 44.0 (25.0, 79.8) | 38.5 (24.0, 82.5) | 0.00 | 0.509 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | — | 361.0 (194.0, 639.9) | 340.3 (182.6, 598.6) | 456.3 (257.0, 762.0) | — | <0.001 |

| TIBC (μg/dL) | — | 260.0 (193.3, 328.3) | 269.0 (202.0, 330.0) | 236.0 (167.0, 309.5) | 0.10 | 0.002 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | — | 5.8 (5.2, 6.5) | 6.1 (5.4, 6.7) | 5.6 (5.0, 6.2) | 0.18 | 0.007 |

| TSH (μIU/mL) | — | 1.0 (0.4, 2.0) | 1.1 (0.5, 2.0) | 1.0 (0.4, 1.9) | 0.01 | 0.282 |

| T4 (μg/dL) | — | 8.1 (6.4, 9.6) | 8.4 (6.8, 9.8) | 7.1 (5.3, 8.5) | 0.24 | <0.001 |

| T3(ng/dL) | — | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.0) | 0.17 | <0.001 |

| VitD3 (ng/mL) | — | 25.1 (15.6, 39.0) | 24.5 (15.5, 38.4) | 27.6 (17.1, 42.2) | 0.04 | 0.027 |

| IgM (g/L) | — | 65.5 (38.5, 112.5) | 98.0 (37.8, 127.3) | 59.0 (36.5, 65.3) | 0.34 | 0.052 |

| IgG (g/L) | — | 1060.5 (835.0, 1394.5) | 1073.0 (877.8, 1422.0) | 976.5 (700.5, 1256.0) | 0.16 | 0.228 |

| UREA (mg/dL) | — | 37.4 (26.9, 56.0) | 34.4 (25.0, 48.0) | 57.3 (37.3, 88.8) | 0.33 | <0.001 |

The Cramer's V test was used to measure the association between categorical variables and status. The value of Cramer's V indicates how strongly two categorical variables are associated, giving a value between 0 and +1. For numeric variables, the Mann–Whitney test was used to compare median values between survivors and deceased cases. Eta was used to measure the association of numeric variables with status, giving a value between 0 and 1. In both Cramer's V and Eta, values close to 1 indicating a high degree of association. The missing values were ignored in calculation of percentages. The median (Q1, Q3) and frequency (%) were used for describing the numeric and categorical variables, respectively. The baseline values of WBC, lymph, NEUT, PLT, HB, MCV, BUN, CR, AST, ALT, LDH, CRP, and UREA were summarized.

3.3. Drug Being Tested to Treat COVID-19 for Hospitalized Patients

The drugs used to treat patients with COVID-19 in hospitals are presented in Table 3 and Figure S1-A in the Supplementary File. Overall, 835 patients had received the remdesivir, and the death rate was the 29.0%. In addition, the death rate of Dexamethasone and Clexane was 23.0% and 17.4%, respectively. As shown in Figure S1-B in the Supplementary File, almost all drugs were used less in the last 3 months of the study than in the third trimester.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of drugs being tested to treat COVID-19 for hospitalized patients in Tehran.

| Variables | Total (n = 5318) | Survivor (n = 4204) | Deceased (n = 1112) | Cramer's V/Eta | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmapheresis | No | 5241 (98.55) | 4159 (98.93) | 1080 (97.12) | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 76 (1.43) | 45 (1.07) | 31 (2.79) | |||

| Amantadine | No | 5308 (99.81) | 4195 (99.79) | 1111 (99.91) | 0.01 | 0.396 |

| Yes | 10 (0.19) | 9 (0.21) | 1 (0.09) | |||

| Acetylsalicylic acid | No | 3384 (63.63) | 2750 (65.41) | 632 (56.83) | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1927 (36.24) | 1451 (34.51) | 476 (42.81) | |||

| Atazanavir | No | 5232 (98.38) | 4140 (98.48) | 1090 (98.02) | 0.02 | 0.284 |

| Yes | 86 (1.62) | 64 (1.52) | 22 (1.98) | |||

| Atorvastatin | No | 2996 (56.34) | 2430 (57.80) | 564 (50.72) | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 2277 (42.82) | 1738 (41.34) | 539 (48.47) | |||

| Atrovent | No | 5091 (95.73) | 4028 (95.81) | 1061 (95.41) | 0.01 | 0.535 |

| Yes | 226 (4.25) | 175 (4.16) | 51 (4.59) | |||

| Azithromycin | No | 3147 (59.18) | 2386 (56.76) | 760 (68.35) | 0.1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 2124 (39.94) | 1780 (42.34) | 343 (30.85) | |||

| Bromhexine | No | 5040 (94.77) | 3970 (94.43) | 1068 (96.04) | 0.03 | 0.032 |

| Yes | 278 (5.23) | 234 (5.57) | 44 (3.96) | |||

| Calcium carbonate | No | 5063 (95.20) | 4027 (95.79) | 1034 (92.99) | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 253 (4.76) | 176 (4.19) | 77 (6.92) | |||

| Ceftriaxone | No | 2761 (51.92) | 2124 (50.52) | 636 (57.19) | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 2555 (48.04) | 2078 (49.43) | 476 (42.81) | |||

| Celexan | No | 3318 (62.39) | 2553 (60.73) | 764 (68.71) | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 2000 (37.61) | 1651 (39.27) | 348 (31.29) | |||

| Clindamycin | No | 5100 (95.90) | 4049 (96.31) | 1049 (94.33) | 0.05 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 178 (3.35) | 123 (2.93) | 55 (4.95) | |||

| Ciprofloxacin | No | 4942 (92.93) | 3975 (94.55) | 965 (86.78) | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 376 (7.07) | 229 (5.45) | 147 (13.22) | |||

| Clidinium C | No | 5302 (99.70) | 4190 (99.67) | 1110 (99.82) | 0.01 | 0.407 |

| Yes | 16 (0.30) | 14 (0.33) | 2 (0.18) | |||

| Combivent | No | 4834 (90.90) | 3834 (91.20) | 999 (89.84) | 0.02 | 0.121 |

| Yes | 442 (8.31) | 336 (7.99) | 105 (9.44) | |||

| Dexamethasone | No | 2892 (54.38) | 2338 (55.61) | 554 (49.82) | 0.05 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 2382 (44.79) | 1832 (43.58) | 548 (49.28) | |||

| Dextromethorphan | No | 4999 (94.00) | 3944 (93.82) | 1053 (94.69) | 0.02 | 0.277 |

| Yes | 278 (5.23) | 227 (5.40) | 51 (4.59) | |||

| Dimenhydrinate | No | 5235 (98.44) | 4133 (98.31) | 1100 (98.92) | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Yes | 43 (0.81) | 39 (0.93) | 4 (0.36) | |||

| Diphenhydramin | No | 3802 (71.49) | 2945 (70.05) | 856 (76.98) | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1471 (27.66) | 1224 (29.12) | 246 (22.12) | |||

| Fluconazole | No | 5234 (98.42) | 4158 (98.91) | 1074 (96.58) | 0.08 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 82 (1.54) | 45 (1.07) | 37 (3.33) | |||

| Heparin | No | 2745 (51.62) | 2323 (55.26) | 421 (37.86) | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 2570 (48.33) | 1879 (44.70) | 690 (62.05) | |||

| Hydroxychloroquine | No | 3061 (57.56) | 2411 (57.35) | 649 (58.36) | 0.01 | 0.766 |

| Yes | 1086 (20.42) | 851 (20.24) | 235 (21.13) | |||

| Imipenem | No | 5067 (95.28) | 4057 (96.50) | 1008 (90.65) | 0.11 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 251 (4.72) | 147 (3.50) | 104 (9.35) | |||

| Interferon | No | 3176 (59.72) | 2551 (60.68) | 624 (56.12) | 0.04 | 0.005 |

| Yes | 2088 (39.26) | 1610 (38.30) | 477 (42.90) | |||

| Kaletra | No | 3149 (59.21) | 2506 (59.61) | 642 (57.73) | 0.04 | 0.005 |

| Yes | 954 (17.94) | 719 (17.10) | 235 (21.13) | |||

| Levofloxacin | No | 4851 (91.22) | 3875 (92.17) | 975 (87.68) | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 427 (8.03) | 297 (7.06) | 129 (11.60) | |||

| Linezolid | No | 5238 (98.50) | 4163 (99.02) | 1073 (96.49) | 0.09 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 79 (1.49) | 40 (0.95) | 39 (3.51) | |||

| Meropenem | No | 3936 (74.01) | 3328 (79.16) | 606 (54.50) | 0.23 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1336 (25.12) | 838 (19.93) | 498 (44.78) | |||

| Magnesium sulfate | No | 4960 (93.27) | 3929 (93.46) | 1029 (92.54) | 0.02 | 0.263 |

| Yes | 357 (6.71) | 274 (6.52) | 83 (7.46) | |||

| N-acetyl cysteine | No | 4600 (86.50) | 3687 (87.70) | 911 (81.92) | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 715 (13.44) | 514 (12.23) | 201 (18.08) | |||

| Ondansetron | No | 5009 (94.19) | 3943 (93.79) | 1064 (95.68) | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Yes | 266 (5.00) | 227 (5.40) | 39 (3.51) | |||

| Oseltamivir | No | 3711 (69.78) | 2907 (69.15) | 803 (72.21) | 0.04 | 0.019 |

| Yes | 350 (6.58) | 293 (6.97) | 57 (5.13) | |||

| Piperacillin | No | 5312 (99.89) | 4200 (99.90) | 1110 (99.82) | 0.01 | 0.454 |

| Yes | 6 (0.11) | 4 (0.10) | 2 (0.18) | |||

| Plasil | No | 5288 (99.44) | 4181 (99.45) | 1105 (99.37) | 0 | 0.744 |

| Yes | 30 (0.56) | 23 (0.55) | 7 (0.63) | |||

| Plavix | No | 4899 (92.12) | 3909 (92.98) | 988 (88.85) | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 418 (7.86) | 295 (7.02) | 123 (11.06) | |||

| Prednisolone | No | 4886 (91.88) | 3879 (92.27) | 1005 (90.38) | 0.03 | 0.048 |

| Yes | 426 (8.01) | 321 (7.64) | 105 (9.44) | |||

| Promethazine | No | 5219 (98.14) | 4124 (98.10) | 1093 (98.29) | 0.01 | 0.67 |

| Yes | 99 (1.86) | 80 (1.90) | 19 (1.71) | |||

| Pulmi | No | 4517 (84.94) | 3585 (85.28) | 932 (83.81) | 0.02 | 0.229 |

| Yes | 797 (14.99) | 616 (14.65) | 179 (16.10) | |||

| Ranitidine | No | 5055 (95.05) | 4006 (95.29) | 1047 (94.15) | 0.02 | 0.141 |

| Yes | 261 (4.91) | 197 (4.69) | 64 (5.76) | |||

| Remdesivir | No | 4482 (84.28) | 3611 (85.89) | 870 (78.24) | 0.09 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 836 (15.72) | 593 (14.11) | 242 (21.76) | |||

| Ribavirin | No | 4013 (75.46) | 3163 (75.24) | 849 (76.35) | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 13 (0.24) | 4 (0.10) | 9 (0.81) | |||

| Salb | No | 5189 (97.57) | 4113 (97.84) | 1074 (96.58) | 0.03 | 0.014 |

| Yes | 128 (2.41) | 90 (2.14) | 38 (3.42) | |||

| Selenium | No | 5159 (97.01) | 4078 (97.00) | 1079 (97.03) | 0 | 0.959 |

| Yes | 159 (2.99) | 126 (3.00) | 33 (2.97) | |||

| Seroflo | No | 5142 (96.69) | 4056 (96.48) | 1084 (97.48) | 0.02 | 0.104 |

| Yes | 175 (3.29) | 147 (3.50) | 28 (2.52) | |||

| Sovodac | No | 3993 (75.08) | 3141 (74.71) | 851 (76.53) | 0.01 | 0.618 |

| Yes | 59 (1.11) | 48 (1.14) | 11 (0.99) | |||

| Vanco | No | 3963 (74.52) | 3409 (81.09) | 552 (49.64) | 0.29 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1350 (25.39) | 792 (18.84) | 558 (50.18) | |||

| Vitamin B | No | 4722 (88.79) | 3776 (89.82) | 945 (84.98) | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 593 (11.15) | 427 (10.16) | 165 (14.84) | |||

| Vitamin C | No | 3866 (72.70) | 3059 (72.76) | 806 (72.48) | 0 | 0.824 |

| Yes | 1449 (27.25) | 1142 (27.16) | 306 (27.52) | |||

| Vitamin D | No | 3742 (70.36) | 2974 (70.74) | 767 (68.97) | 0.02 | 0.245 |

| Yes | 1570 (29.52) | 1225 (29.14) | 344 (30.94) | |||

| Pantazole | No | 1327 (24.95) | 1081 (25.71) | 246 (22.12) | 0.05 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 2419 (45.49) | 1860 (44.24) | 558 (50.18) | |||

| Concor (bisoprolol) | No | 3212 (60.40) | 2561 (60.92) | 650 (58.45) | 0.1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 448 (8.42) | 300 (7.14) | 148 (13.31) | |||

| Amlodipine | No | 3214 (60.44) | 2544 (60.51) | 669 (60.16) | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 412 (7.75) | 293 (6.97) | 119 (10.70) | |||

| Aldactone | No | 3321 (62.45) | 2613 (62.16) | 707 (63.58) | 0.03 | 0.063 |

| Yes | 276 (5.19) | 204 (4.85) | 72 (6.47) | |||

| Lactulose | No | 3121 (58.69) | 2462 (58.56) | 658 (59.17) | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Yes | 488 (9.18) | 365 (8.68) | 123 (11.06) | |||

| Carvedilol | No | 3497 (65.76) | 2740 (65.18) | 756 (67.99) | 0 | 0.803 |

| Yes | 83 (1.56) | 66 (1.57) | 17 (1.53) | |||

| Fentanyl | No | 3406 (64.05) | 2778 (66.08) | 628 (56.47) | 0.36 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 177 (3.33) | 24 (0.57) | 152 (13.67) | |||

| Apotel | No | 2552 (47.99) | 2014 (47.91) | 538 (48.38) | 0.02 | 0.192 |

| Yes | 1109 (20.85) | 853 (20.29) | 255 (22.93) | |||

| Zinc | No | 3115 (58.57) | 2430 (57.80) | 684 (61.51) | 0.01 | 0.52 |

| Yes | 499 (9.38) | 395 (9.40) | 103 (9.26) | |||

| Insulin | No | 2767 (52.03) | 2190 (52.09) | 576 (51.80) | 0.03 | 0.061 |

| Yes | 966 (18.16) | 737 (17.53) | 229 (20.59) | |||

| Lasix | No | 2708 (50.92) | 2222 (52.85) | 485 (43.62) | 0.15 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1029 (19.35) | 701 (16.67) | 328 (29.50) | |||

| Hematinic | No | 3499 (65.80) | 2735 (65.06) | 763 (68.62) | 0.03 | 0.106 |

| Yes | 72 (1.35) | 62 (1.47) | 10 (0.90) |

The Cramer's V test was used to measure the association between categorical variables and status. The value of Cramer's V indicates how strongly two categorical variables are associated, giving a value between 0 and +1. For numeric variables, the Mann–Whitney test was used to compare median values between survivors and deceased cases. Eta was used to measure the association of numeric variables with status, giving a value between 0 and 1. In both Cramer's V and Eta, values close to 1 indicating a high degree of association. The missing values were ignored in calculation of percentages. The median (Q1, Q3) and frequency (%) were used for describing the numeric and categorical variables, respectively.

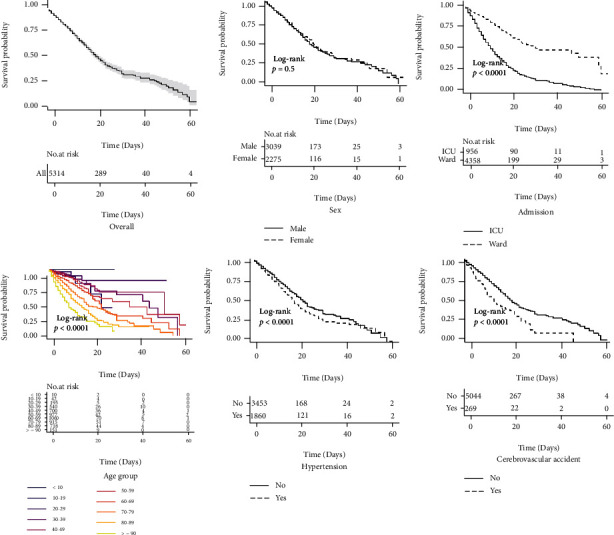

3.4. Survival Rate of COVID-19 Patients

The survival rate of COVID-19 patients and its risk factors were assessed using Kaplan-Meier estimator (Figure 2 and Figure S2 in the Supplementary File). Accordingly, the survival rates of patients in the first, second, and third weeks of hospitalization were about 0.85, 0.65, and 0.50, respectively. The risk of death was not different between men and women (p = 0.500), but it was significantly associated with several factors as shown in Figure 2, including ICU admission, older age, HTN, and CVA.

Figure 2.

The Kaplan-Meier survival time by demographic variables.

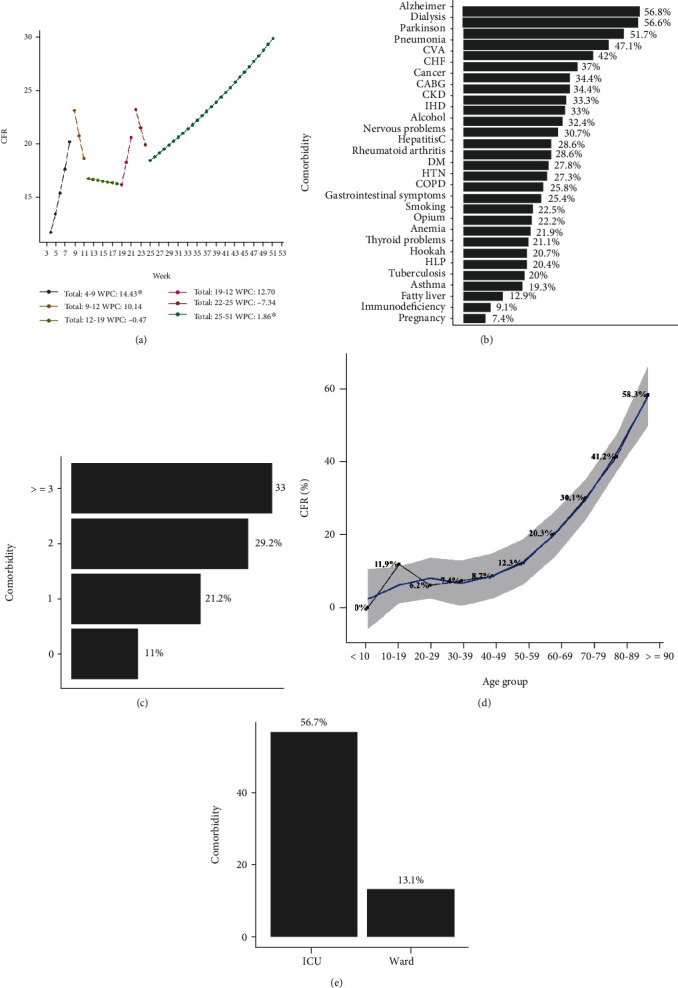

3.5. The CFR of COVID-19 Patients

As shown in Figure 3(a), the CFR of COVID-19 has changed over time. Overall, five joinpoints found in weeks of 9, 12, 19, 22, and 25. In addition, the last trend of CFR was upward and significant (WPC: 14.43% for weeks of 4-9; WPC: 1.86% for weeks of 25-51). According to Figure 3(b), CFR among COVID-19 patients with comorbidities of Alzheimer, dialysis, Parkinson, pneumonia, and CVA were higher than 40%. Based on Figure 3(c), the higher number of comorbidities was associated with higher CFR. As shown in Figure 3(d), the CFR has grown linearly with a slope of 10% from patients aged 50 years and older. Figure 3(e) shows that the CFR for patients admitted to the ICU was 3.1 times higher than that in the general ward.

Figure 3.

The case fatality rate of COVID-19 patients.

4. Discussion

According to our data, 5 318 COVID-19 patients were admitted to three tertiary university hospitals in Tehran, Iran, from 20 March 2020 to 18 March 2021. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest national sample of COVID-19 inpatients with detailed information in one of the remarkable centers of SARS-CoV-2 in Iran. Our findings include detailed demographics, clinical characteristics, paraclinical data, therapeutic agents, and their association with survival rate and CFR.

The majority of cases were men with the median age of 60 years suffering from hypertension and diabetes, which was in line with China, USA, and Italy patterns [23, 24]. The most predominant symptoms were dyspnea (55.9%), cough (45.8%), fever (42.4%), and weakness (34.4%) which were consistent with Rivera-Izquierdo et al. [25] and Guan et al. [26]. 21% of patients were deceased in hospital, which was similar to Germany and France [20], but lower than UK with 39% of mortality [27]. Definitely, this rate could vary, regarding to significant differences between countries in epidemiology, health care systems, and lengths of follow-up. The significant risk factors of death related to COVID-19 were aging, loss of consciousness, the need for intubation and low O2 saturation, and high ranges of WBC, BUN, LDH, IL-6, pro-BNP, and HCO3, which are consistent with prior reports [28–30]. In accordance with Rosenthal et al. study, patients older than 65 years accounted for more than 75% of all in-hospital mortality [31]. Similarly, Cummings et al. reported older age, cardiopulmonary disease, and higher ranges of CRP, and liver and renal tests as predictors of poor progression [32]. High levels of serum creatinine and urea could be due to direct kidney damage or fluid imbalance, and also leukocytosis might be a sign of bacterial superinfection. Similar to China [33] and Italy [34], hypertension and diabetes were associated with poor prognosis. The same as our study, Aggarwal et al. reported that the severity of COVID-19 among patients with cerebrovascular disease is higher [35]. Deceased cases had higher range of blood pressure, pulse rate, respiratory rate, and lower oxygen saturation compared to survivors. The data showed that abnormal vital signs could be predictors of severity. In contrary to Brazilian study [36], we had a weak relationship between age and length of hospital stay since elderly tend to stay more time in the hospital, and on the other hand, younger patients had a higher chance to recover from COVID-19 than older cases.

Remdesivir was administered to 15.72% of cases and had a significant role in their survival. The US Food and Drug Administration approved an emergency use of remdesivir for critical cases of COVID-19 on May 1, 2020 [37, 38]. Enoxaparin and heparin were used in nearly 85% of cases and had a beneficial effect due to prophylaxis and treatment of thrombosis and thrombophilia triggered by COVID-19 [39]. Another challenging drug is Dexamethasone with presented positive results similar to several studies by suppressing the proinflammatory storm of cytokines and chemokines [40]. Guidelines of the UK chief medical officers, the European Medicines Agency, the World Health Organization, and the National Institutes of Health in the United States have approved the use of glucocorticoids in hospitalized cases requiring oxygen support [41–43]. In order to evaluate the impact of each therapeutic agent, more researches are required, whereas these effects are evaluated beside several factors in this study.

The most important features of this study were the estimation of survival rate, CFR of COVID-19 inpatients, and their association with epidemiological factors. Our findings confirm that survival rate of COVID-19 inpatients is exclusively low for older cases requiring ICU admission and intubation and with underlying comorbidities including HTN, IHD, and CVA. These data was in line with a study from Italy and England [44, 45]. The trend of CFR was increasing (WPC: 1.86) during weeks 25 to 51, which is similar to Yemen [46]. This pattern might be due to more accurate recording of cases medical data or the hypothesis that gradually SARS-CoV-2 turns into more invasive variants. In contrary to our study, the rCFR is declining gradually over time in England and New York, which could be attributed to increased detection of asymptomatic or mild cases, improvements in medical management of severely ill patients, and increased public awareness [45, 47]. The CFR varies among different countries, since the calculations, PCR testing, and healthcare services are different. There was significant relation among CFR with aging and comorbidities, especially DM, dialysis, and cancer. Actually, older people had more comorbidities and compromised immune systems and are more vulnerable to infectious disease [48]. Also, these results could be a clue that exacerbation of preexisting conditions due to SARS-CoV-2 increases the death rate of COVID-19 in cases with comorbidities [49]. Perone reported the association of environmental, demographics, and healthcare factors with CFR [50]. Comprehensive estimation of CFR could be served as a theory for successful control of COVID-19 in Iran, by studying the future patterns of CFR.

This study had some strength points. First, the important variables related to the mortality of COVID-19 patients were determined using effect size indices, and the survival rate of patients in different categories of these variables was assessed. Second, the most common symptoms, comorbidities, and prescribed medications were identified among patients with COVID-19, and CFR was reported in patients with various comorbidities and medications. The trends of CFR were evaluated during the study period by age and sex. Fourth, all laboratory data of COVID-19 patients were included in this study. However, the study had some limitations. First, all of our cases were hospitalized, which is a bias to outpatients, so these results could be overestimated and needs further studies to provide a standard approach for accurate and acceptable guidelines. Second, follow-up after discharge was not performed in this study, so we could not be able to include postdischarge deceased cases. Third, there was no data about noninvasive respiratory support including CPAP and NIV.

5. Conclusions

Since SARS-CoV-2 is a novel virus and the pandemic is still alive, we provide a large cohort study to evaluate demographics and clinical profile and their association with mortality. Older patients and cases with comorbidities are at a higher risk for developing complications from COVID-19 infection and even death. Considering the increasing trend of CFR, it is crucial to guide healthcare providers in decision-making and get the most out of their skills and facilities to immediately detect at-risk cases and evaluate the course of infection, to improve therapeutic protocols and reduce virus transmission and mortality rates.

Abbreviations

- HTN:

Hypertension

- IHD:

Ischemic heart disease

- CABG:

Coronary artery bypass graft

- CHF:

Congestive heart failure

- COPD:

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DM:

Diabetes mellitus

- CVA:

Cerebrovascular accident

- CKD:

Chronic kidney disease

- HLP:

Hyperlipidemia

- WBC:

White blood cell

- PLT:

Platelets

- Hb:

Hemoglobin

- MCV:

Mean corpuscular volume

- Cr:

Creatinine

- AST:

Aspartate aminotransferase

- ALT:

Alanine transaminase

- LDH:

Lactate dehydrogenase

- CRP:

C-reactive protein

- Na:

Sodium

- K:

Potassium

- Ca:

Calcium

- P:

Phosphorous

- BIL:

Bilirubin

- TG:

Triglyceride

- Chol:

Cholesterol

- HDL:

High-density lipase

- LDL:

Low-density lipase

- FBS:

Fasting blood sugar

- HbA1c:

Hemoglobin A1c

- ESR:

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- IL-6:

Interlukine-6

- CPK:

Creatine phosphokinase

- CK-MB:

Creatine kinase-MB

- Pro-BNP:

N-Terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide

- PTT:

Partial thromboplastin time

- PT:

Prothrombin time

- INR:

International normalized ratio

- BE:

Bass excess

- ANCA:

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

- c-ANCA:

Cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

- p-ANCA:

Prenuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

- FDP:

Fibrinogen-degradation product

- SI:

Serum iron

- TIBCL:

Total iron-binding capacity

- TSH:

Thyroid stimulating hormone

- T4:

Thyroxine

- T3:

Triiodothyronine

- IgM:

Immunoglobulin M

- IgG:

Immunoglobulin G.

Contributor Information

Mohamad Amin Pourhoseingholi, Email: aminphg@gmail.com.

Amirhossein Sahebkar, Email: amir_saheb2000@yahoo.com.

Data Availability

Some restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Hamidreza Hatamabadi contributed to the conceptualization, supervision, and resources. Tahereh Sabaghian contributed to the supervision and resources. Amir Sadeghi contributed to the supervision, resources, and conceptualization. Kamran Heidari contributed to the supervision and resources. Seyed Amir Ahmad Safavi-Naini contributed to the project administration, data curation, validation, investigation, and writing of the original draft. Mehdi Azizmohammad Looha contributed to the formal analysis, methodology, validation, writing of the original draft, visualization, and writing (review and editing). Nazanin Taraghikhah contributed to the investigation, writing of the original draft, and writing (review and editing). Shayesteh Khalili contributed to the supervision and resources. Keivan karrabi contributed to the investigation. Afsaneh Saffarian contributed to the investigation. Saba Shahsavan contributed to the investigation. Hossein Majlesi contributed to the investigation. Amirreza Allahgholipour Komleh contributed to the investigation. Saba Hatari contributed to the investigation. Nadia Zameni contributed to the investigation. Saba Ilkhani contributed to the investigation. Shideh Moftakhari Hajimirzaei contributed to the investigation. Aydin Ghaffari contributed to the investigation. Mohammad Mahdi Fallah contributed to the investigation. Reyhaneh Kalantar contributed to the investigation. Nariman Naderi contributed to the investigation. Parnian Bahmaei contributed to the investigation. Naghmeh Asadimanesh contributed to the investigation. Romina Esbati contributed to the investigation. Omid Yazdani contributed to the investigation. Fatemeh Sojaeian contributed to the investigation. Zahra Azizan contributed to the investigation. Nastaran Ebrahimi contributed to the investigation. Fateme Jafarzade contributed to the investigation. Amirali Soheili contributed to the investigation. Fateme Gholampoor contributed to the investigation. Negarsadat Namazi contributed to the investigation. Ali Solhpour contributed to the supervision and methodology. Tannaz Jamialahmadi contributed to the supervision and validation. Mohamad Amin Pourhoseingholi contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, project administration, writing (review and editing), resources, and validation. Amirhossein Sahebkar contributed to the conceptualization, writing (review and editing), validation, resources, and methodology.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: laboratory statistics of COVID-19 patients in Tehran. Figure S1: (A) Drugs being tested to treat COVID-19 for hospitalized patients. (B) Frequency of drug during time (note: only drugs that were used more than 250 times were shown. Labels represented the frequency of drugs for survived and deceased patients). Figure S2: the Kaplan-Meier survival time by demographic variables.

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. New England Journal of Medicine . 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant M. C., Geoghegan L., Arbyn M., et al. The prevalence of symptoms in 24,410 adults infected by the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis of 148 studies from 9 countries. PLoS One . 2020;15(6):p. e0234765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pathak S. K., Pandey S., Pandey A., et al. Focus on uncommon symptoms of COVID-19: potential reason for spread of infection. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews . 2020;14(6):1873–1874. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashraf M. A., Shokouhi N., Shirali E., et al. COVID-19, An early investigation from exposure to treatment outcomes in Tehran, Iran. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences . 2021;26(1):p. 114. doi: 10.4103/jrms.JRMS_1088_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azizmohammad Looha M., Rezaei-Tavirani M., Rostami-Nejad M., et al. Assessing sex differential in COVID-19 mortality rate by age and polymerase chain reaction test results: an Iranian multi-center study. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy . 2022;20(4):631–641. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2022.2000860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moayed M. S., Vahedian-Azimi A., Mirmomeni G., et al. Coronavirus (COVID-19)-associated psychological distress among medical students in Iran. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology . 2021:245–251. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-59261-5_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vahedian-Azimi A., Ashtari S., Alishiri G., et al. The primary outcomes and epidemiological and clinical features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Iran. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology . 2021;1321:199–210. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-59261-5_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/iran/

- 9.Pinheiro A. L. S., Andrade K. T. S., Silva D. O., Zacharias F. C. M., Gomide M. F. S., Pinto I. C. Health management: the use of information systems and knowledge sharing for the decision making process. Texto & Contexto-Enfermagem . 2016;25(3) doi: 10.1590/0104-07072016003440015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farì G., de Sire A., Giorgio V., et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in a cohort of Italian rehabilitation healthcare workers. Journal of Medical Virology . 2022;94(1):110–118. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierucci P., Ambrosino N., Di Lecce V., et al. Prolonged active prone positioning in spontaneously breathing non-intubated patients with COVID-19-associated hypoxemic acute respiratory failure with PaO2/FiO2 >150. Frontiers in medicine . 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.626321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bianconi V., Mannarino M. R., Figorilli F., et al. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and its prognostic impact on patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Nutrition . 2021;91-92:p. 111408. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2021.111408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonakdaran S., Layegh P., Hasani S., et al. The prognostic role of metabolic and endocrine parameters for the clinical severity of COVID-19. Disease Markers . 2022;2022:8. doi: 10.1155/2022/5106342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yaribeygi H., Sathyapalan T., Jamialahmadi T., Sahebkar A. The impact of diabetes mellitus in COVID-19: a mechanistic review of molecular interactions. Journal of Diabetes Research . 2020;2020:9. doi: 10.1155/2020/5436832.5436832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Najjar H., Al-Rousan N. A Classifier Prediction Model to predict the Status of Coronavirus COVID-19 Patients in South Korea. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences . 2020;24(6):3400–3403. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202003_20709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao Z., Chen A., Hou W., et al. Prediction model and risk scores of ICU admission and mortality in COVID-19. PLoS One . 2020;15(7):p. e0236618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang S., Zha Y., Li W., et al. A fully automatic deep learning system for COVID-19 diagnostic and prognostic analysis. European Respiratory Journal . 2020;56(2):p. 2000775. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00775-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wynants L., Van Calster B., Collins G. S., et al. Prediction models for diagnosis and prognosis of COVID-19: systematic review and critical appraisal. BMJ . 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giovannetti G., De Michele L., De Ceglie M., et al. Lung ultrasonography for long-term follow-up of COVID-19 survivors compared to chest CT scan. Respiratory Medicine . 2021;181:p. 106384. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karagiannidis C., Mostert C., Hentschker C., et al. Case characteristics, resource use, and outcomes of 10 021 patients with COVID-19 admitted to 920 German hospitals: an observational study. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine . 2020;8(9):853–862. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30316-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byard R., Payne-James J. Encyclopedia of Forensic and Legal Medicine . Academic Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reich N. G., Lessler J., Cummings D. A., Brookmeyer R. Estimating absolute and relative case fatality ratios from infectious disease surveillance data. Biometrics . 2012;68(2):598–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2011.01709.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bai Y., Yao L., Wei T., et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. Journal of the American Medical Association . 2020;323(14):1406–1407. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mez J., Daneshvar D. H., Kiernan P. T., et al. Clinicopathological evaluation of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in players of American football. Journal of the American Medical Association . 2017;318(4):360–370. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.8334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rivera-Izquierdo M., del Carmen V.-U. M., R-delAmo J. L., et al. Sociodemographic, clinical and laboratory factors on admission associated with COVID-19 mortality in hospitalized patients: a retrospective observational study. PLoS One . 2020;15(6):p. e0235107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guan W.-j., Ni Z.-y., Hu Y., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. New England journal of medicine . 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Docherty A. B., Harrison E. M., Green C. A., et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with COVID-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ . 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogedegbe G., Ravenell J., Adhikari S., et al. Assessment of racial/ethnic disparities in hospitalization and mortality in patients with COVID-19 in New York City. JAMA network open . 2020;3(12):p. e2026881-e. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.26881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imam Z., Odish F., Gill I., et al. Older age and comorbidity are independent mortality predictors in a large cohort of 1305 COVID-19 patients in Michigan, United States. Journal of Internal Medicine . 2020;288(4):469–476. doi: 10.1111/joim.13119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang B., Zhou X., Qiu Y., et al. Clinical characteristics of 82 cases of death from COVID-19. PLoS One . 2020;15(7):p. e0235458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenthal N., Cao Z., Gundrum J., Sianis J., Safo S. Risk factors associated with in-hospital mortality in a US national sample of patients with COVID-19. JAMA network open . 2020;3(12):p. e2029058-e. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cummings M. J., Baldwin M. R., Abrams D., et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet . 2020;395(10239):1763–1770. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu Z., McGoogan J. M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Journal of the American Medical Association . 2020;323(13):1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grasselli G., Zangrillo A., Zanella A., et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region, Italy. Jama . 2020;323(16):1574–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aggarwal G., Lippi G., Michael H. B. Cerebrovascular disease is associated with an increased disease severity in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a pooled analysis of published literature. International Journal of Stroke . 2020;15(4):385–389. doi: 10.1177/1747493020921664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macedo M. C., Pinheiro I. M., Carvalho C. J., et al. Correlation between hospitalized patients’ demographics, symptoms, comorbidities, and COVID-19 pandemic in Bahia, Brazil. PLoS One . 2020;15(12):p. e0243966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Food U. Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for Emergency Use of Remdesivir for the Treatment of Hospitalized 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Patients . 2020.

- 38.Sterne J., Murthy S., Diaz J., et al. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19: A Meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association . 2020;324(13):1330–1341. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vickers N. J. Animal communication: when I’m calling you, will you answer too? Current Biology . 2017;27(14):R713–R715. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noreen S., Maqbool I., Madni A. Dexamethasone: therapeutic potential, risks, and future projection during COVID-19 pandemic. European journal of pharmacology. . 2021;894:p. 173854. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.173854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whitty C. Dexamethasone in the Treatment of COVID-19: Implementation and Management of Supply for Treatment in Hospitals . London: Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Institutes of HealthCOVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines, National Institutes of Health. April 2022 https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/ [PubMed]

- 43.Siemieniuk R., Rochwerg B., Agoritsas T., et al. A living WHO guideline on drugs for COVID-19. British Medical Journal . 2020;370 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grasselli G., Greco M., Zanella A., et al. Risk factors associated with mortality among patients with COVID-19 in intensive care units in Lombardy, Italy. JAMA internal medicine . 2020;180(10):1345–1355. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dennis J. M., McGovern A. P., Vollmer S. J., Mateen B. A. Improving survival of critical care patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in England: a national cohort study, March to June 2020. Critical care medicine . 2021;49(2):209–214. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dureab F., Al-Awlaqi S., Jahn A. COVID-19 in Yemen: preparedness measures in a fragile state. The Lancet Public Health . 2020;5(6):p. e311. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30101-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Horwitz L. I., Jones S. A., Cerfolio R. J., et al. Trends in COVID-19 risk-adjusted mortality rates. Journal of Hospital Medicine . 2021;16(2):90–92. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones H., Pardthaisong L. Demographic interactions and developmental implications in the era of AIDS: findings from northern Thailand. Applied Geography . 2000;20(3):255–275. doi: 10.1016/S0143-6228(00)00007-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Acharya K. P., Sah R., Subramanya S. H., et al. COVID-19 case fatality rate: misapprehended calculations. journal of pure and applied microbiology . 2020;14(3):1675–1679. doi: 10.22207/JPAM.14.3.05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perone G. The determinants of COVID-19 case fatality rate (CFR) in the Italian regions and provinces: an analysis of environmental, demographic, and healthcare factors. Science of the Total Environment . 2021;755:p. 142523. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: laboratory statistics of COVID-19 patients in Tehran. Figure S1: (A) Drugs being tested to treat COVID-19 for hospitalized patients. (B) Frequency of drug during time (note: only drugs that were used more than 250 times were shown. Labels represented the frequency of drugs for survived and deceased patients). Figure S2: the Kaplan-Meier survival time by demographic variables.

Data Availability Statement

Some restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.