Abstract

Pulmonary artery acceleration time (PAT) and PAT: ejection time (PATET) ratio are echocardiographic measurements of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). These non-invasive quantitative measurements are ideal to follow longitudinally through the clinical course of PAH, especially as it relates to need for and/or response to treatment. This review article focuses on the current literature of PATET measurement for infants and children as it relates to shortening of the PATET ratio in PAH. At the same time, further development of PATET as an outcome measure for PAH in pre-clinical models, particularly mice, such that the field can move forward to human clinical studies that are both safe and effective. Here we present what is known about PATET in infants and children and discuss what is known in pre-clinical models with particular emphasis on neonatal mouse models. In both animal models and human disease, PATET allows for longitudinal measurements in the same individual, leading to more precise determinations of disease/model progression and/or response to therapy.

Introduction:

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a disease characterized by right heart catheter measurement of mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) greater than 20 mmHg at rest, according to the recent 6th World Symposium 1. Over time PAH can lead to right ventricular failure and death in any age group. In infants and children, PAH can occur as a result of the chronic lung disease of prematurity, bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD). The World Health Organization (WHO) PH classification system places PAH associated with BPD into group 3 2, wherein the pulmonary vasculature is relatively contracted and/or remodeled, decreasing vessel diameter. Monitoring for PAH in high risk populations such as BPD patients is crucial for early PAH diagnosis and management. Catheter-based hemodynamic measurements are invasive, usually requiring anesthesia, and therefore not ideal in many clinical situations, such as a patient who is small (neonatal/infant), has poor vascular integrity, and/or requires long term right ventricular pressure (RVP) monitoring. Alternatively, RVP monitoring by pulsed-wave Doppler echocardiography using pulmonary artery acceleration time: ejection time (PATET) ratio is non-invasive, quantitative, and more easily assessed than tricuspid regurgitation measurement 3 with high intra- and inter-observer agreement 4. Since early diagnosis and treatment of PAH are vitally important to slow PAH development and prevent PAH-associated morbidity and mortality, PATET has evolved as a useful clinical predictor of PAH in many clinical settings in adults. However, its use is relatively new in small children particularly infants. Therefore, the aims of this review are to 1) examine the use of PATET as a quantitative clinical tool to assess PAH in the current pediatric literature, and 2) discuss the utility of PATET measurement in small animal models of PAH.

PAT and PATET ratio:

Pulmonary artery acceleration time (PAT), also known as PAAT, PAcT, or time to peak velocity (TPV), is the time (in msec) it takes for blood from the right ventricle to exit through the pulmonary valve and reach peak velocity after the pulmonary valve opens during systole. PAT is inversely related to HR 5–7, and adjustment for HR is made by dividing by the right ventricular ejection time ((RV)ET) to get the PATET 8. When PAP is elevated, as in the case of PAH, tachycardia has less of an effect on the PAT 9. The (RV)ET is the total time (in msec) it takes for blood from the right ventricle to exit through the pulmonary valve during one systolic cycle, from the opening to the closing of the pulmonary valve 10. The PATET then is the ratio of these two time intervals, which gives a unitless (msec/msec) proportion, whereby the smaller the proportion (shortening of the PATET) the less time per cycle is spent getting to peak velocity, indicative of higher mPAP. Stated another way, when mPAP is elevated, as measured by elevated right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP), it will take a shorter time for blood flow from the pulmonary artery to reach maximum velocity (faster flow acceleration) 11,12, and the PATET ratio will be decreased/shortened. In summary, the shorter the PATET, the worse the PAH, reflecting the indirect relationship of PATET and measures of PAH including RVSP, PAP, and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), as well as the direct relationship of PATET and measures of PAH including pulmonary arterial compliance and RV mechanical performance 3,5,7.

Adult PAT:

PAT research was first conducted in adults who normally have baseline HR <100bpm. The correction for HR with ET was therefore less of a concern and had not yet been introduced in the literature. The following studies are in adults and evaluated by transthoracic echocardiography unless otherwise noted. In 1983, Kitabatake et al. were the first to discover that PAT shortened as mPAP increased (mean PAT=137 msec when mPAP <20 mmHg, mean PAT=97 msec when mPAP >20 mmHg) 12. Also, in the 1980’s, the linear, inverse relationship between PAT and mPAP was established, within a PAT range of 74–170 msec 5,12–15. Currently, PAT is used either independently or in conjunction with tricuspid regurgitation velocity (TRV) to predict PAH 6,7,14,16,17, and PAT and TRVmax are inversely correlated 18. Granstam et al. 2013 confirmed that PAT is a clinically useful tool, especially in high risk patients, and reported that a PAT<100 msec is strongly associated with PAH 19. In 2015, Tousignant et al. studied patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery, where simultaneous hemodynamic measurements by trans-esophageal echocardiography and catheter-based pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) showed that PAT correlated with invasive hemodynamic parameters 20. In 2016, Cowie et al. also studied cardiac surgical patients and found that PAT<107 msec predicted PAH 21. More recently, Zhan et al. utilized PAT to classify PAH severity (mild 70–90 msec, medium 50–70 msec, and severe <50 msec) 22. Interestingly, adults exposed to hyperoxia (100%O2) had modestly lengthened PAT, whereas hypoxia (17%O2) had minimal effect 23. PAT can also be used to predict cardiovascular events in young adults 24.

Children PAT and PATET:

For children, use of PAT to predict PAH can vary by age, body surface area, and HR. There is a positive correlation of PAT and age, PAT and body surface area, and a negative correlation of PAT and HR 7. Overall in children, detection of elevated PVR, decreased pulmonary arterial compliance, and RV dysfunction occurs at PAT <90 msec and PATET <0.3 3,10, and PATET<0.29 predicts PAH with 100% sensitivity and 96% specificity 6,7. In 1984, Kosturakis et al. reported a range of PAT in children of 51–140 msec 25. In a cohort of both children and adults with cystic fibrosis, PAT<101 msec was proposed as a useful decision making tool for clinicians regarding timing of lung transplantation 26.

Infant PAT and PATET:

PATET and TRV are the major quantitative echocardiographic measurements in older children and adults to predict PAH. As patients become smaller, the TRV is more difficult to assess, thus the importance of measuring PAT and PATET. In both infants and children, PAT has been shown to predict PAP, PVR, and vascular compliance as measured by cardiac catheterization 3,6,10. In 2008, at a time when PATET was not yet routinely measured, Mourani et al. stated that the accurate estimate of catheter-based systolic PAP by echocardiographic quantitative measurements were much needed, especially in children < 2 years of age 27. In 2020, PAT was found to correlate with systolic PAP as estimated by TRV in neonates and young infants using the equation: sPAP = 82.6 – 0.58 x PAT + right atrial (RA) mean pressure 28.

Preterm infant PAT and PATET:

A study by Carlton et al. in 2017 found that quantitative (PATET and TRV) echocardiographic measurements of PAH were more reliable among cardiologists than qualitative measurements in the assessment of pulmonary vascular disease in preterm neonates 29. Indeed, much of the PATET literature in infants has focused on preterm infants, with and without co-morbidities such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

In healthy preterm infants, PATET increases longitudinally from birth to 1 year of age indicative of the normal decrease in RV afterload that occurs postnatally 4. In the 1990’s, Gill et al. studied the natural history of PATET in a cohort of very low birthweight infants and found that the PATET becomes greater over the first three weeks of life, corresponding to the normal drop in PVR. Additionally those patients who continued to require supplemental oxygen after 36 weeks post menstrual age (PMA) had a lower PATET than room air controls 30,31, and PATET could be used to predict preterm patients that would develop chronic lung disease 32,33. Levy et al. published PATET values for a cohort of preterm patients at 1 year of age and found that PATET was lower in patients with PAH than in those without PAH 3,5. In patients ≤ 1 year of age, some of which were preterm with BPD and/or patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), infant PAT was inversely related to mPAP, systolic PAP, and PVR 5. Interestingly, when BPD-PH patients received either 100% O2 or 20ppm nitric oxide, PATET lengthened, indicative of improved PAP 34.

Prenatal PAT and PATET:

In 1987, Machado et al. reported the first human fetal (16–30 weeks gestation) PAT, as well as aortic AT, and found that PAT was shorter than aortic AT, consistent with the fetal circulatory pattern 35. In 2003, Fuke et al. predicted pulmonary hypoplasia using shorter fetal PATET obtained antenatally (20–39 weeks gestation). Normal values for mean PATET were also obtained in both right (0.17) and left (0.15) fetal pulmonary arteries 36. Additional antenatal human fetal studies have shown that mean PAT and PATET lengthen with increasing gestational age (18 weeks: PAT=24 msec, PATET=0.14; 38 weeks: PAT=36 msec, PATET=0.20), likely reflecting normal fetal pulmonary vascular development, decreasing PVR, and increasing pulmonary blood flow 37–39.

PAT and PATET in small animals:

PAH has been studied in canines, who, like humans, can develop PAH in response to underlying respiratory disease and left sided heart disease. Additionally, canine PAH is commonly associated with degenerative valve disease and parasites, such as heartworms. Veterinarians routinely use echocardiography clinically to diagnose and assess PAH, however, this can be challenging given the diverse number of species, and factors such as size, breed, and anatomical complexities 40,41. The American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) recently published a consensus statement providing a guideline for diagnosis, classifying, treating, and monitoring canine PAH 40. One of the recommendations includes evaluating anatomical sites, such as the pulmonary artery using echocardiography. RV outflow doppler time (similar to PAT) <52–58 msec or PATET <0.30 has been shown to suggest a higher probability of PAH in canines 40,42–44. Additionally, systolic notching of the Doppler RV outflow profile can assist in determining PAH in veterinary species 40.

Early studies in mice had difficulty visualizing the heart by echocardiography because of high heart rate (>400 bpm) and small size 45,46. However, recent advances in technology, as well as comprehensive protocols to assess the right heart in mice, have overcome these barriers with great potential to advance the study of PAH in mouse models 47–49. Echocardiographic probes are now miniaturized with frequencies >30 MHz designed for rodents 50–52. Echocardiographic landmarks in mice that are relevant to PAH include: right ventricle, right ventricular outflow tract (PAT measurement), and tricuspid valve (TRV measurement), 53. PAT and TRV can then be used to calculate PVR 54–56.

In a seminal article by Thibault et al. in 2010, mice underwent echocardiography and PATET was compared to pressures obtained from right ventricle catheterization at 3 months of age, which are currently the youngest mice studied using catheterization and echocardiography. It was determined that PATET<0.39 detected elevated RVSP (>32 mmHg) with sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 86%, while keeping both intra-observer and inter-observer variability at <6% 57. This demonstrated that PATET by echocardiography could be used to accurately assess PAH in mice greater than 3 months of age. However, the question still remains as to whether PATET by echocardiography can be utilized to assess PAH in mice less than 3 months of age.

Recently, PAT and PATET have been routinely measured in several PAH mouse models, adult and neonatal. Although the great strength of mouse models is the ability to interrogate genetic molecular targets causal to the disease phenotype of interest, many of the PAH mouse models are environmental exposures. A study in adult mice exposed to three weeks of hypoxia and repeated exposure to SU5416 (VEGF receptor inhibition) showed shortening of the PATET, as well as increases in RV wall thickness measured in diastole, compared to control 45. In a study by Zhu et al. 2019, an eight-week hypoxic mouse model and two rat models (hypoxia/sugen and MCT) showed shortening of the PATET compared to control 58. Adiponectin knockout mice have shortening of the PATET and evidence of PAH at one year of age 59. PATET has also been used to longitudinally evaluate adult mice with congenital diaphragmatic hernia for PAH 60. Reynolds et al. in 2016, evaluated newborn C57BL/6J mice in 70% O2 at 14 days and found evidence of shortening of the PATET, demonstrating PAH in the youngest cohort of mice to be reported at this time 61.

Experiment: PAT and PATET in a PAH hypoxic mouse model:

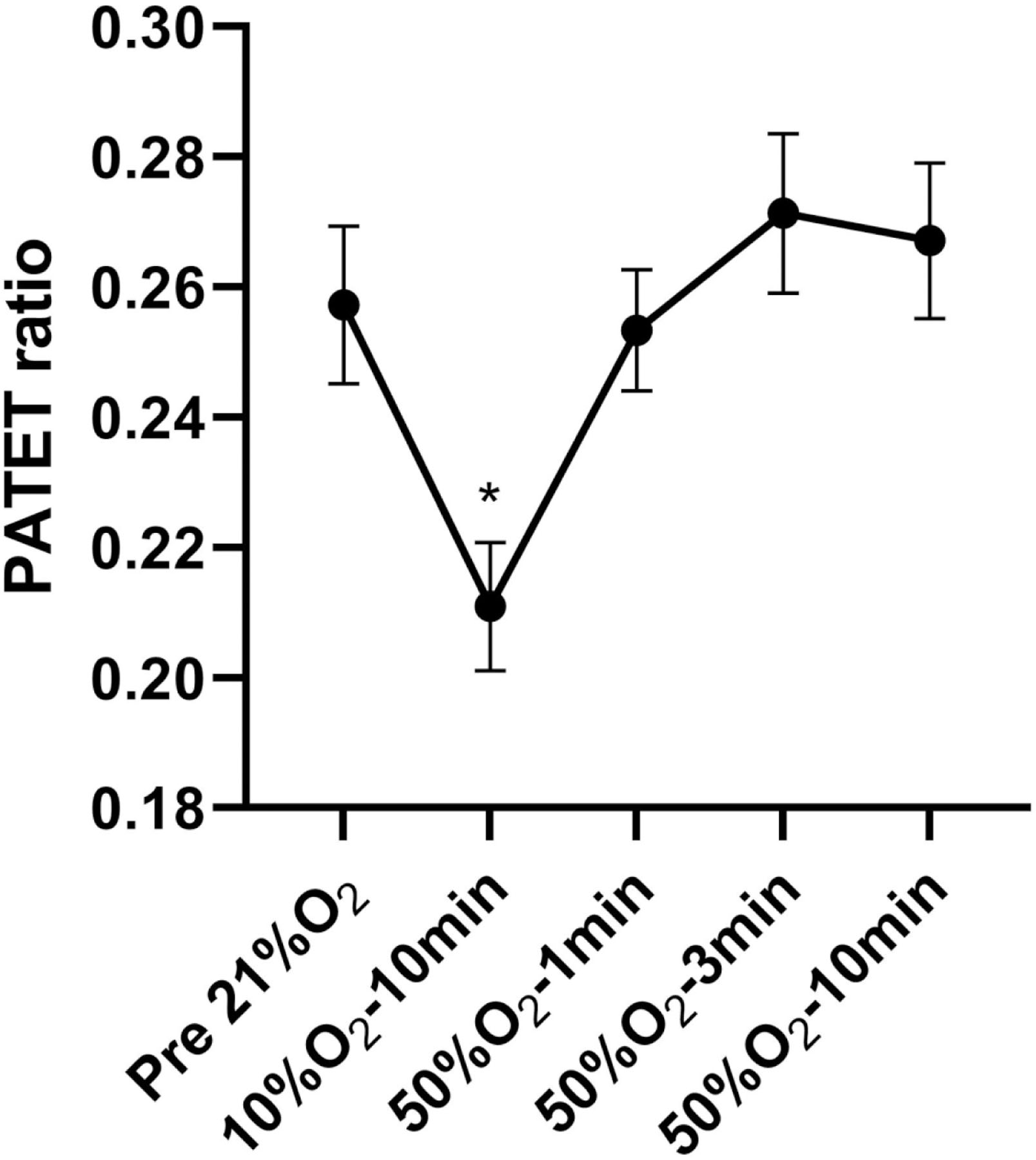

We recently evaluated PATET by echocardiography 56 in anesthetized 28-day old C57BL mice before, during an acute hypoxic exposure-induced PAH, and recovery in hyperoxia (50% O2) (Figure). We measured appreciable shortening (by 18%) of the PATET during acute hypoxic exposure (mean PATET=0.211) compared to pre-hypoxia (mean PATET=0.257), and recovery of PATET with hyperoxia at 1min, p=0.014). These data confirm that PATET can be reliably repeatedly measured in 28-day old mice and that shortening of the PATET, consistent with elevated PAP, can be observed in an acute exposure to hypoxia. These data confirm previous studies 57,61 that PAT and PATET measurements are important tools to assess PAH even in very young mice. A mouse model such as this will be very useful in studying the progression of PAH disease, particularly in the context of models of human disease such as persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn or BPD.

Figure. PATET shortening in PAH hypoxic mouse model.

28-day old C57BL mice before (Pre-21% O2), during hypoxia (10% O2), and recovery with hyperoxia (50% O2). Mice were anesthetized with inhaled 1–3% isoflurane during the experiment. Each mouse (N=9) had 3–10 data points that were averaged prior to calculation of mean ± SE presented. Repeated measures one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. *10%O2 vs. 50%O2−1min, p=0.014; 10%O2 vs. 50%O2−3min, p<0.001; 10%O2 vs. 50%O2−10min, p<0.01.

PAT and PATET Limitations:

There are general limitations of small animal models, including the areas of studying breathing mechanics, gas exchange, and pulmonary hemodynamics 62, especially catheterization. Because of the difficulty to catheterize extremely small neonatal mice, we focus on developing PATET by echo as a potential solution. However, there are several limitations and/or considerations that need to be addressed when analyzing PAT and PATET data. Operator technique is important in acquiring data from Doppler echocardiography, including operator variation in determining the optimal angle between the transducer and pulmonary artery 63. This is an issue especially with smaller individuals, and it has been shown that the measurement of blood velocity decreases as the mis-alignment in the angle increases, and at >20% difference clinically the test is no longer considered accurate 47,64. Another consideration is that PAT measurements when expressed as a range, are not continuous because the Doppler waveform is derived from intermittent Fourier analysis 23. Some researchers have proposed MRI as a better modality to estimate PATET 63, and at least three studies in patients with bronchopulmonary dysplasia have determined that another quantitative measurement, eccentricity index, may be a better measure of right ventricular mechanics 65–67. Guidelines for measuring cardiopulmonary physiology by both echocardiography and MRI have been published and are an important step forward in the development of preclinical animal models 68,69. Despite superior imaging of MRI and micro-CT 70, the primary advantage of echo assessment is that the echo probe technique and PATET measurement can be 1) studied on a mouse prior to clinical use on a neonatal patient and 2) measure in real-time (functional echocardiography71), with relatively little anesthesia. Anesthesia can have negative impacts include hypercarbia, acidosis, hypothermia, alteration to ventilation/perfusion matching, tidal volume, and hypoxia resulting in pulmonary vasoconstriction 72–74. Any of these changes could alter PAT and PATET ratio but have so far not been studied. In addition, exploration of alternative anesthetic protocols to achieve reduction in minimum alveolar concentration for volatile agents and their negative impacts is needed.

It is important to note that PAP estimation by maximal TRV in the absence of pulmonary stenosis continues to be the gold standard echocardiographic measurement to estimate systolic PAP 5,11,75–77. However, TR envelope is not accessible much of the time 5,78,79, whereas PATET is accessible in >90% of patients 11,69. In mice, TR occurs only in severe PH and because of problems with flow alignment, measurements by echo are prone to inaccuracy 46,61. Additionally, studies in both children and adults have put the TRV under scrutiny, with some published data that TRV does not accurately predict right heart catheterization measurements 10,80.

In preterm neonates, PATET may not be useful in the context of patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) with left-to-right shunting. PDA causes turbulent flow in the pulmonary artery, potentially altering PATET measurement 5,6,10,81. Gaulton et al. studied 57 infants (77% with PDA) who had both an echocardiogram and catheterization done within 10 days of each other and found that there was a correlation between PAT and PAP at catheterization, but no correlation between PATET and PAP at catheterization [7], highlighting the ambiguity of data interpretation in the context of PDA.

Discussion on the correction for HR made in the calculation of PATET was presented earlier under the heading “PAT and PATET ratio”. However, further adjustments have been proposed by correcting for the RR interval. Tossavainen et al. in 2013 corrected for HR by calculating a corrected PAT using the formula PAT/√RR interval, finding in adults that a corrected PAT <90 msec is a good predictor of PVR >3 Wood units 17. Interestingly, in neonatal patients, studies have not shown a correlation between PAT or PATET and RR interval 10,81,82.

Besides HR and large left-to-right shunts, RV dysfunction due to reasons other than PAH, can also confound the PATET, such that the PATET should routinely be interpreted in the context of measurements of RV systolic function and shunts 81. There are also considerations specific to the fetus including early RV and LV developmental effects on intrinsic contractile properties, vascular impedance, capacitance of the vascular bed, and ventricular preload, that should be taken into consideration while interpreting the fetal PATET 83.

Conclusions:

PAT and PATET are useful tools for the study of PAH in neonates, infants, and children although further studies are needed to determine optimal cut-off values that have robust correlation with PAH as diagnosed by catherization. Furthermore, studies are needed to differentiate normal developmental changes from changes that are attributable to disease progression. In terms of preclinical studies, the mouse model is of particular interest given its wide-spread use for studying neonatal diseases and developmental changes. Further study to establish PATET as a routine and accurate measure of PAH in small and large animal models is needed to provide a non-invasive, longitudinal measure of PAH. For pre-clinical studies in neonatal mice to study PAH in bronchopulmonary dysplasia, early time points (day of life 14–28), when catherization may be limited, validation of PATET against Fulton’s index and/or pulmonary vascular histology may be necessary. Consideration of neonatal functional echo studies 71 that include PATET as a real-time tool for a bedside PAH evaluation that is reliable and accurate would greatly advance assessment and treatment plans for these very sick infants.

Impact:

PATET ratio is a quantitative measurement by a non-invasive technique, Doppler echocardiography, providing clinicians a more precise/accurate, safe, and longitudinal assessment of pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH).

We present a brief history/ state-of-the-art of PATET ratio to predict PAH in adult, children, infants, and fetus, as well as in small animal models of PAH.

In a preliminary study, PATET shortened by 18% during acute hypoxic exposure compared to pre-hypoxia.

Studies are needed to establish PATET especially in mouse models of disease, such as bronchopulmonary, as a routine measure of PAH.

Financial support:

This work was supported by NIH NHLBI K08 HL129080 (PI: Trittmann) and the Abigail Wexner Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital.

Abbreviations:

- AT

acceleration time

- BPD

bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- MCT

monocrotaline

- NO

nitric oxide

- mPAP

mean pulmonary arterial pressure

- PAH

pulmonary arterial hypertension

- PAT

pulmonary artery acceleration time

- PATET

pulmonary artery acceleration time ejection time ratio

- PCWP

pulmonary capillary wedge pressure

- PDA

patent ductus arteriosus

- PMA

post menstrual age

- PVR

pulmonary vascular resistance

- RA

right atrial

- RVET or ET

right ventricular ejection time

- RV(S)P

right ventricular (systolic) pressure

- TR(J)V

tricuspid regurgitation (jet) velocity

- VTIRVOT

velocity time interval of the right ventricular outflow tract

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Consent: Patient consent was not required.

References:

- 1.Simonneau G et al. Haemodynamic Definitions and Updated Clinical Classification of Pulmonary Hypertension. Eur Respir J 53 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nef HM, Mollmann H, Hamm C, Grimminger F & Ghofrani HA Pulmonary Hypertension: Updated Classification and Management of Pulmonary Hypertension. Heart 96, 552–559 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy PT, Patel MD, Choudhry S, Hamvas A & Singh GK Evidence of Echocardiographic Markers of Pulmonary Vascular Disease in Asymptomatic Infants Born Preterm at One Year of Age. J Pediatr 197, 48–56 e42 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel MD et al. Echocardiographic Assessment of Right Ventricular Afterload in Preterm Infants: Maturational Patterns of Pulmonary Artery Acceleration Time over the First Year of Age and Implications for Pulmonary Hypertension. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 32, 884–894 e884 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaulton JS et al. Relationship between Pulmonary Artery Acceleration Time and Pulmonary Artery Pressures in Infants. Echocardiography 36, 1524–1531 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koestenberger M et al. Normal Reference Values and Z Scores of the Pulmonary Artery Acceleration Time in Children and Its Importance for the Assessment of Pulmonary Hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 10 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Habash S et al. Normal Values of the Pulmonary Artery Acceleration Time (Paat) and the Right Ventricular Ejection Time (Rvet) in Children and Adolescents and the Impact of the Paat/Rvet-Index in the Assessment of Pulmonary Hypertension. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 35, 295–306 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardin JM et al. Effect of Acute Changes in Heart Rate on Doppler Pulmonary Artery Acceleration Time in a Porcine Model. Chest 94, 994–997 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mallery JA, Gardin JM, King SW, Ey S & Henry WL Effects of Heart Rate and Pulmonary Artery Pressure on Doppler Pulmonary Artery Acceleration Time in Experimental Acute Pulmonary Hypertension. Chest 100, 470–473 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy PT et al. Pulmonary Artery Acceleration Time Provides a Reliable Estimate of Invasive Pulmonary Hemodynamics in Children. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 29, 1056–1065 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang YC, Huang CH & Tu YK Pulmonary Hypertension and Pulmonary Artery Acceleration Time: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 31, 201–210 e203 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitabatake A et al. Noninvasive Evaluation of Pulmonary Hypertension by a Pulsed Doppler Technique. Circulation 68, 302–309 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dabestani A et al. Evaluation of Pulmonary Artery Pressure and Resistance by Pulsed Doppler Echocardiography. Am J Cardiol 59, 662–668 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan KL et al. Comparison of Three Doppler Ultrasound Methods in the Prediction of Pulmonary Artery Pressure. J Am Coll Cardiol 9, 549–554 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuda M et al. Reliability of Non-Invasive Estimates of Pulmonary Hypertension by Pulsed Doppler Echocardiography. Br Heart J 56, 158–164 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marra AM et al. Reference Ranges and Determinants of Right Ventricle Outflow Tract Acceleration Time in Healthy Adults by Two-Dimensional Echocardiography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 33, 219–226 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tossavainen E et al. Pulmonary Artery Acceleration Time in Identifying Pulmonary Hypertension Patients with Raised Pulmonary Vascular Resistance. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 14, 890–897 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yared K et al. Pulmonary Artery Acceleration Time Provides an Accurate Estimate of Systolic Pulmonary Arterial Pressure During Transthoracic Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 24, 687–692 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Granstam SO, Bjorklund E, Wikstrom G & Roos MW Use of Echocardiographic Pulmonary Acceleration Time and Estimated Vascular Resistance for the Evaluation of Possible Pulmonary Hypertension. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 11, 7 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tousignant C & Van Orman JR Pulmonary Artery Acceleration Time in Cardiac Surgical Patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 29, 1517–1523 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cowie B, Kluger R, Rex S & Missant C The Relationship between Pulmonary Artery Acceleration Time and Mean Pulmonary Artery Pressure in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: An Observational Study. Eur J Anaesthesiol 33, 28–33 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhan HY, Xu FQ, Liu CX & Zhao G Clinical Applicability of Monitoring Pulmonary Artery Blood Flow Acceleration Time Variations in Monitoring Fetal Pulmonary Artery Pressure. Adv Clin Exp Med 27, 1723–1727 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ernst JH & Goldberg SJ Do Changes in Fraction of Inspired Oxygen Affect Pulmonary Artery Acceleration Time? Am J Cardiol 65, 252–254 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreira HT et al. Pulmonary Artery Acceleration Time in Young Adulthood and Cardiovascular Outcomes Later in Life: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 33, 82–89 e81 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kosturakis D, Goldberg SJ, Allen HD & Loeber C Doppler Echocardiographic Prediction of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in Congenital Heart Disease. Am J Cardiol 53, 1110–1115 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Damy T et al. Pulmonary Acceleration Time to Optimize the Timing of Lung Transplant in Cystic Fibrosis. Pulm Circ 2, 75–83 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mourani PM, Sontag MK, Younoszai A, Ivy DD & Abman SH Clinical Utility of Echocardiography for the Diagnosis and Management of Pulmonary Vascular Disease in Young Children with Chronic Lung Disease. Pediatrics 121, 317–325 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohammad Nijres B et al. Utility of Pulmonary Artery Acceleration Time to Estimate Systolic Pulmonary Artery Pressure in Neonates and Young Infants. Pediatr Cardiol 41, 265–271 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlton EF et al. Reliability of Echocardiographic Indicators of Pulmonary Vascular Disease in Preterm Infants at Risk for Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. J Pediatr 186, 29–33 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gill AB & Weindling AM Raised Pulmonary Artery Pressure in Very Low Birthweight Infants Requiring Supplemental Oxygen at 36 Weeks after Conception. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 72, F20–22 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gill AB & Weindling AM Pulmonary Artery Pressure Changes in the Very Low Birthweight Infant Developing Chronic Lung Disease. Arch Dis Child 68, 303–307 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Subhedar NV, Hamdan AH, Ryan SW & Shaw NJ Pulmonary Artery Pressure: Early Predictor of Chronic Lung Disease in Preterm Infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 78, F20–24 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Su BH, Watanabe T, Shimizu M & Yanagisawa M Doppler Assessment of Pulmonary Artery Pressure in Neonates at Risk of Chronic Lung Disease. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 77, F23–27 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sehgal A, Blank D, Roberts CT, Menahem S & Hooper SB Assessing Pulmonary Circulation in Severe Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia Using Functional Echocardiography. Physiol Rep 9, e14690 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Machado MV, Chita SC & Allan LD Acceleration Time in the Aorta and Pulmonary Artery Measured by Doppler Echocardiography in the Midtrimester Normal Human Fetus. Br Heart J 58, 15–18 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fuke S et al. Antenatal Prediction of Pulmonary Hypoplasia by Acceleration Time/Ejection Time Ratio of Fetal Pulmonary Arteries by Doppler Blood Flow Velocimetry. Am J Obstet Gynecol 188, 228–233 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaoui R et al. Doppler Echocardiography of the Main Stems of the Pulmonary Arteries in the Normal Human Fetus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 11, 173–179 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rasanen J, Huhta JC, Weiner S, Wood DC & Ludomirski A Fetal Branch Pulmonary Arterial Vascular Impedance During the Second Half of Pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 174, 1441–1449 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Azpurua H et al. Acceleration/Ejection Time Ratio in the Fetal Pulmonary Artery Predicts Fetal Lung Maturity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 203, 40 e41–48 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reinero C et al. Acvim Consensus Statement Guidelines for the Diagnosis, Classification, Treatment, and Monitoring of Pulmonary Hypertension in Dogs. J Vet Intern Med 34, 549–573 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fleming, E. a. E., S. Pulmonary Hypertension. Compendium 28, 1–15 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Visser LC, Im MK, Johnson LR & Stern JA Diagnostic Value of Right Pulmonary Artery Distensibility Index in Dogs with Pulmonary Hypertension: Comparison with Doppler Echocardiographic Estimates of Pulmonary Arterial Pressure. J Vet Intern Med 30, 543–552 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Serres F et al. Diagnostic Value of Echo-Doppler and Tissue Doppler Imaging in Dogs with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. J Vet Intern Med 21, 1280–1289 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schober KE & Baade H Doppler Echocardiographic Prediction of Pulmonary Hypertension in West Highland White Terriers with Chronic Pulmonary Disease. J Vet Intern Med 20, 912–920 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ciuclan L et al. A Novel Murine Model of Severe Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184, 1171–1182 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones JE et al. Serial Noninvasive Assessment of Progressive Pulmonary Hypertension in a Rat Model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283, H364–371 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brittain E, Penner NL, West J & Hemnes A Echocardiographic Assessment of the Right Heart in Mice. J Vis Exp (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kohut A, Patel N & Singh H Comprehensive Echocardiographic Assessment of the Right Ventricle in Murine Models. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound 24, 229–238 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moceri P et al. Imaging in Pulmonary Hypertension: Focus on the Role of Echocardiography. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 107, 261–271 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Urboniene D, Haber I, Fang YH, Thenappan T & Archer SL Validation of High-Resolution Echocardiography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Vs. High-Fidelity Catheterization in Experimental Pulmonary Hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 299, L401–412 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Badea CT, Bucholz E, Hedlund LW, Rockman HA & Johnson GA Imaging Methods for Morphological and Functional Phenotyping of the Rodent Heart. Toxicol Pathol 34, 111–117 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rey-Parra GJ et al. Blunted Hypoxic Pulmonary Vasoconstriction in Experimental Neonatal Chronic Lung Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 178, 399–406 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou YQ et al. Comprehensive Transthoracic Cardiac Imaging in Mice Using Ultrasound Biomicroscopy with Anatomical Confirmation by Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Physiol Genomics 18, 232–244 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bossone E, Bodini BD, Mazza A & Allegra L Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: The Key Role of Echocardiography. Chest 127, 1836–1843 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abbas AE et al. A Simple Method for Noninvasive Estimation of Pulmonary Vascular Resistance. J Am Coll Cardiol 41, 1021–1027 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hannemann J, Zummack J, Hillig J & Boger R Metabolism of Asymmetric Dimethylarginine in Hypoxia: From Bench to Bedside. Pulm Circ 10, 2045894020918846 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thibault HB et al. Noninvasive Assessment of Murine Pulmonary Arterial Pressure: Validation and Application to Models of Pulmonary Hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 3, 157–163 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu Z et al. Echocardiographic Assessment of Right Ventricular Function in Experimental Pulmonary Hypertension. Pulm Circ 9, 2045894019841987 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Summer R et al. Adiponectin Deficiency: A Model of Pulmonary Hypertension Associated with Pulmonary Vascular Disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297, L432–438 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shah M, Phillips MR, Quintana M, Stupp G & McLean SE Echocardiography Allows for Analysis of Pulmonary Arterial Flow in Mice with Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia. J Surg Res 221, 35–42 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reynolds CL, Zhang S, Shrestha AK, Barrios R & Shivanna B Phenotypic Assessment of Pulmonary Hypertension Using High-Resolution Echocardiography Is Feasible in Neonatal Mice with Experimental Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia and Pulmonary Hypertension: A Step toward Preventing Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 11, 1597–1605 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morty RE Using Experimental Models to Identify Pathogenic Pathways and Putative Disease Management Targets in Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Neonatology 117, 233–239 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wacker CM et al. The Pulmonary Artery Acceleration Time Determined with the Mr-Race-Technique: Comparison to Pulmonary Artery Mean Pressure in 12 Patients. Magn Reson Imaging 12, 25–31 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baumgartner H et al. Echocardiographic Assessment of Valve Stenosis: Eae/Ase Recommendations for Clinical Practice. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 22, 1–23; quiz 101–102 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ehrmann DE et al. Echocardiographic Measurements of Right Ventricular Mechanics in Infants with Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia at 36 Weeks Postmenstrual Age. J Pediatr 203, 210–217 e211 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McCrary AW et al. Differences in Eccentricity Index and Systolic-Diastolic Ratio in Extremely Low-Birth-Weight Infants with Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia at Risk of Pulmonary Hypertension. Am J Perinatol 33, 57–62 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abraham S & Weismann CG Left Ventricular End-Systolic Eccentricity Index for Assessment of Pulmonary Hypertension in Infants. Echocardiography 33, 910–915 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lindsey ML, Kassiri Z, Virag JAI, de Castro Bras LE & Scherrer-Crosbie M Guidelines for Measuring Cardiac Physiology in Mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 314, H733–H752 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Truong U et al. Update on Noninvasive Imaging of Right Ventricle Dysfunction in Pulmonary Hypertension. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 10, 1604–1624 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pinar IP & Jones HD Novel Imaging Approaches for Small Animal Models of Lung Disease (2017 Grover Conference Series). Pulm Circ 8, 2045894018762242 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.de Boode WP et al. Application of Neonatologist Performed Echocardiography in the Assessment and Management of Persistent Pulmonary Hypertension of the Newborn. Pediatr Res 84, 68–77 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Saraswat V Effects of Anaesthesia Techniques and Drugs on Pulmonary Function. Indian J Anaesth 59, 557–564 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Trachsel D, Svendsen J, Erb TO & von Ungern-Sternberg BS Effects of Anaesthesia on Paediatric Lung Function. Br J Anaesth 117, 151–163 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gille J et al. Perioperative Anesthesiological Management of Patients with Pulmonary Hypertension. Anesthesiol Res Pract 2012, 356982 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yock PG & Popp RL Noninvasive Estimation of Right Ventricular Systolic Pressure by Doppler Ultrasound in Patients with Tricuspid Regurgitation. Circulation 70, 657–662 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Subhedar NV & Shaw NJ Changes in Pulmonary Arterial Pressure in Preterm Infants with Chronic Lung Disease. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 82, F243–247 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chow LC, Dittrich HC, Hoit BD, Moser KM & Nicod PH Doppler Assessment of Changes in Right-Sided Cardiac Hemodynamics after Pulmonary Thromboendarterectomy. Am J Cardiol 61, 1092–1097 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mourani PM et al. Early Pulmonary Vascular Disease in Preterm Infants at Risk for Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 191, 87–95 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Benatar A, Clarke J & Silverman M Pulmonary Hypertension in Infants with Chronic Lung Disease: Non-Invasive Evaluation and Short Term Effect of Oxygen Treatment. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 72, F14–19 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Groh GK et al. Doppler Echocardiography Inaccurately Estimates Right Ventricular Pressure in Children with Elevated Right Heart Pressure. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 27, 163–171 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Levy PT, El Khuffash A, Woo KV & Singh GK Right Ventricular-Pulmonary Vascular Interactions: An Emerging Role for Pulmonary Artery Acceleration Time by Echocardiography in Adults and Children. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 31, 962–964 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fitzgerald D, Evans N, Van Asperen P & Henderson-Smart D Subclinical Persisting Pulmonary Hypertension in Chronic Neonatal Lung Disease. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 70, F118–122 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Reller MD, Morton MJ, Reid DL & Thornburg KL Fetal Lamb Ventricles Respond Differently to Filling and Arterial Pressures and to in Utero Ventilation. Pediatr Res 22, 621–626 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]