Abstract

Background

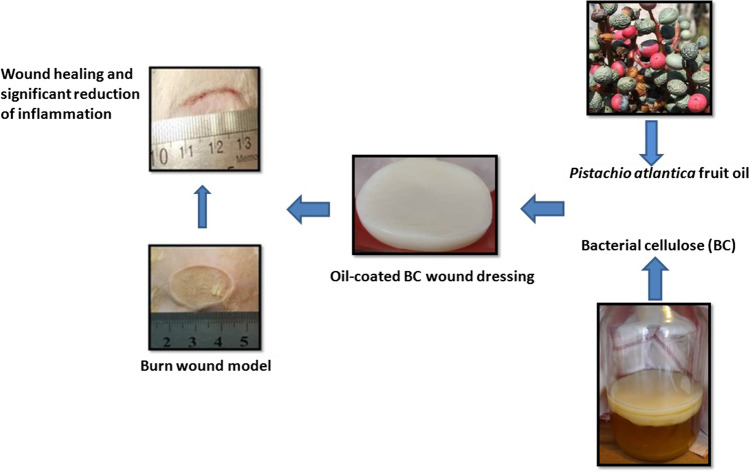

Biological activities of Pistacia atlantica have been investigated for few decades. The fruit oil of the plant has been used for treatment of wounds, inflammation, and other ailments in Traditional Persian Medicine (TPM).

Objectives

The main objectives of this study were to analyze the chemical composition of Pistacia atlantica fruit oil and to study wound healing and anti-inflammatory effects of oil-absorbed bacterial cellulose in an in vivo burn wound model.

Method

Bacterial cellulose membrane was prepared from Kombucha culture and Fourier-transform infrared was used to characterize the bacterial cellulose. Cold press technique was used to obtain Pistacia atlantica fruit oil and the chemical composition was analyzed by gas chromatography. Bacterial cellulose membrane was impregnated with the Pistacia atlantica fruit oil. Pistacia atlantica hydrogel was prepared using specific Carbopol. Burn wound model was used to evaluate in vivo wound healing and anti-inflammatory effects of the wound dressings containing either silver sulfadiazine as positive control, Pistacia atlantica hydrogel or bacterial cellulose membrane coated with the Pistacia atlantica fruit oil. Blank dressing was used as negative control.

Results

FT-IR analysis showed that the structure of the bacterial cellulose corresponded with the standard FT-IR spectrum. The major components of Pistacia atlantica fruit oil constituted linoleic acid (38.1%), oleic acid (36.9%) and stearic acid (3.8%). Histological analysis showed that bacterial cellulose coated with fruit oil significantly decreased the number of neutrophils as a measure of inflammation compared to either negative control or positive control (p < 0.05). Wound closure occurred faster in the treated group with fruit oil-coated bacterial cellulose compared to the other treatments (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

The results showed that bacterial cellulose coated with Pistacia atlantica fruit oil can be a potential bio-safe dressing for wound management.

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Wound healing, Pistacia atlantica, Bacterial cellulose

Introduction

Natural oils from different sources such as medicinal plants and certain animals have been used in different traditional practices for the treatment of cutaneous irritations. Pistacia atlantica (P. atlantica) or Bene belonging to the Anacardiaceae family is an indigenous plant in Iran which has been used in Traditional Persian Medicine [1]. P. atlantica fruit oil is commonly called Bene Hull Oil (BHO) constituting compounds such as carotene and tocopherols with antioxidant properties. Tocopherols have potential skin health properties and exert biological activities on the skin similar to vitamin E [2, 3]. There is some evidence on the wound healing properties of certain fruit oils. Khedir and colleagues investigated the effect of Pistacia lentiscus fruit oil on laser burn wounds and observed that the fruit oil treatment significantly improved wound contraction compared to untreated control group [4]. Previously, the fatty acid composition of P. lentiscus seed oil was analyzed in Algeria and was shown to contain high amount (73.44%) of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). Major PUFAs in that analysis included oleic acid (45.66%) and linolenic acid (24.21%) [5]. Moreover, the mechanism of wound healing upon treatment with fruit oils has been investigated by measuring the trans-epidermal water loss. Trans-epidermal moisturizing activity was positively correlated with wound healing process [6, 7].

Fish oil is another example of a natural product with many health benefits. Fish oil is rich in fatty acids and has been shown to alleviate skin disorders. Fatty acids, in general, are classified into saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. The unsaturated fatty acids come in either monounsaturated or poly unsaturated forms. Major saturated fatty acids in the fish oil include myristic acid (14:0), palmitic acid (16:0), stearic acid (18:0), and behenic acid (22:0). The unsaturated fatty acids in the fish oil are myristoleic acid (14:1ω5), palmitoleic acid (16:1ω7), oleic acid (18:1ω9), eicosenoic acid (20:1ω9), gadoleic acid (20:1ω11), erucic acid (22:1ω9), and catoleic acid (22:1ω11). Linoleic acid (LA, 18:2ω6), α-linolenic acid (ALA, 18:3ω3), DHA (22:6ω3), EPA (22:5ω3) constitute the mono and poly unsaturated fatty acids [8].

The safety and efficacy of different types of wound dressings have been extensively studied. Bacterial cellulose (BC) is a bio-safe biomaterial that can potentially be used in the treatment of wounds. Compared to plant cellulose, bacterial cellulose is much more pure and does not contain any lignin. Although the chemical structure of BC is similar to plant cellulose, it has specific physical, mechanical [9, 10], and biological properties [9, 11, 12]. The cellulose-producing bacteria have been found in Kombucha, a traditional fermented tea that contains symbiotic culture of different osmophilic yeast and acetic acid bacteria. Gluconacetobacter xylinus and Acetobacter xylinum are Gram-negative bacteria that produce and secrete cellulosic pellicle [11]. The BC fibrils are much smaller than plant cellulose providing larger surface area for loading different medications [9]. Moreover, BC is compatible with the human body and does not trigger immune system reactions [13, 14]. Special features of BC led researchers to devise scaffolds in tissue engineering [15] and to manufacture wound dressings [16, 17], artificial blood vessels [18], dental implants [19, 20], and skeletal grafts [20].

Burn wounds are important cause of death and disability and impose high costs of medication, surgery and hospitalization to the healthcare systems worldwide [21, 22]. Many treatments have been used in traditional medicine. Yet, the treatment of burn wounds and subsequent complications including infections and inflammation remain as challenging issues in modern medicine.

The main objective of this study was to investigate the wound healing properties of Pistacia atlantica fruit oil in the presence and absence of bacterial cellulose.

Materials and method

Materials

All the solvents and reagents used in this study were of analytical grade. Methanol, n-hexane, sodium hydroxide, methanolic boron trifluoride, acetic acid and sodium sulfate were purchased from Merck, Darmstadt, Germany. The certified standard mixture of 37-component FA methyl ester C4-C24 was purchased from (Accuastan-dard, USA). Linoleic acid and linolenic acid methyl ester isomer were purchased from Sigma, USA. Flamexin® (Silver sulfadiazine) topical cream was purchased from Sina-Darou, Iran.

Method

Preparation of bacterial cellulose membranes

Kombucha culture (Fungus tea; Khubdat Humza) was used as the BC raw material. To prepare a culture medium, one L tap water was boiled and 90 g/L sucrose was added during boiling as explained by Chen, C. and B. Liu [23]. Then, 3 g/L black tea leaves was added to the sucrose solution and the leaves were removed after 10 min. After cooling to room temperature the solution was inoculated with 1:100 Kombucha (local source, Iran). To inhibit the growth of undesirable microorganisms the pH was adjusted to 3-4 with 5% acetic acid (Merck, Germany).

The culture was left at 25°C for 7 days to obtain the cellulose pellicle.

Purification of bacterial cellulose

Purification of bacterial cellulose was performed based on Trevino-Garza et al. [24]. Briefly, Bacterial cellulose was washed twice with distilled water. Then, the harvested BC was boiled in 1% NaOH (Merck, Germany) to detach the cells and other undesirable substances. The NaOH solution was changed every 15 min. This procedure was continued until the color of BC was changed to white. Then, the BC was washed with distilled water until the pH of the washing liquid turned neutral.

Preparation of oil-coated BC bandages (BC-Oil)

Coating of bacterial cellulose with the fruit oil was performed based on Meftahi et al., [25]. The BC membrane was cut in 2×2 cm pieces, and was sterilized by an autoclave. Then, 50% of water was removed in an oven (Memmert, Germany) at 50°C. Finally, BC membranes were impregnated in 200 µl P. atlantica oil and were stored at 4°C.

Collection of Pistacia atlantica

Pistacia atlantica fruits were collected in late summer and early fall from South Khorasan

Province, Iran (35°02ʹ49ʺ N 59°58ʹ29ʺ E 1894 m). The identification of the plant species and assigning scientific name has been done by the botanical expert, Professor Gholamreza Amin at the Herbarium of Faculty of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Oil extraction

Hydraulic mechanical cold press technique at 24°C, 1000- 1500 psi was used to obtain Pistacia atlantica fruit oil as explained by Shouqin et al. [26]. The fruits were added into the cold press machine (made in Iran) without heat treatment. The impurities were separated by filtration.

Purified oil was kept at room temperature.

Characterization of bacterial cellulose

Surface functional groups of bacterial cellulose were analyzed using Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR, Nicollet FT-IR Magna 550 spectrometer) with spectral range of 4000400 cm-1 [27]. Bacterial cellulose was dried in an oven (Memmert, Germany) at 70°C. Dried bacterial cellulose was pressed into pellet with potassium bromide (KBr) in a ratio of 1:19. Briefly, the powdered samples and KBr were ground to make particles smaller than 5 mm. Then, the pellet was obtained and infrared spectroscopy was performed.

GC-FID analysis of fruit oil

Sample preparation was done by methyl-esterification using BF3-MeOH method according to

American Oil Chemist Society (AOCS) [5]. First, 0.1 g of oil was weighed in a vial and 1 ml

of 4% (N) methanolic sodium hydroxide solutions was added. The mixture was heated at 50 °C for 10 min. Then, 1.2 ml BF3-MeOH was added and heated for extra 5 min. After cooling, 1.5 ml n-hexane was added and mixed vigorously by a vortex. The mixture was left at room temperature until the two phases were visible. Then, 1 ml of the top organic phase was removed and anhydrous Na2SO4 was added. The sample solution was injected to the gas chromatography (GC) after filtering through 0.22 μm disposable syringe filter.

The GC-FID analyses were performed using an Agilent model 7890 GC instrument equipped with a flame-ionization detector. A highly polar capillary column (100 m × 0.25 mm i.d × 0.25 μm film thickness) of HP-88 (Agilent, USA) was used to separate the FAMEs. Nitrogen was used as the carrier at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. A split ratio of 100:1 was used and 1 μL of the sample was injected into the instrument. The oven temperature program was as follows:

180°C for 30 min, then the temperature was elevated to 200°C at a rate of 1.5°C/min and kept at 200°C for 30 min. The temperature was set at 220°C for the injector and at 250°C for the detector. The samples were analyzed in triplicate and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Preparation of Pistacia atlantica hydrogel (Carb-Oil)

Preparation of hydrogel was performed based on unpublished data of our own lab and Rossi et al. [28]. Carbopols are water-soluble polymers used as condensers and stabilizers for suspensions and emulsions, most of which are related to the hydrophilic nature of the polymer. In this study, 0.5 g TEGO® 140 Carbopol (Evonik, Germany) was gradually added to 50 ml of distilled water on a heater- stirrer at 200 rpm for 35 min. After complete dissolution, 5 g of Pistacia atlantica fruit oil (10%) was added to the solution, while still stirring on the heater-stirrer. Finally, triethanolamine was added dropwise.

Burn wound model

An animal study was conducted using an established model in our lab [29] based on ethical guidelines of Iran National Committee for Ethics in Biomedical Research (IR.TUMS.MEDICINE.REC.1399.1194). Twenty five male Wistar rats weighing about 250 g were used. The animals were provided with water and food and were housed under standard condition of temperature at 12-h light/dark. The rats were randomly divided into four groups of five animals, numbered 1 to 5. Then, their dorsal skins were shaved, and second-degree burns were created by a round soldering iron (20 mm2 diameter) at 100°C for 10 sec and ophthalmic ointment was applied to their eyes to prevent drying during treatments. The rats were kept on a warm towel for gradual recovery. Different treatments using sterile gauze pads were applied on the wounds before full recovery of the rats. During the three-week treatments, the dressings were changed every other day, and photographs were taken with a digital camera at a constant distance from the burn wounds.

Different groups with the following treatments were studied during three weeks:

Neg. Cont: Blank dressing without any medication (negative control)

Pos. Cont: Silver sulfadiazine cream (positive control)

Carb-Oil: Carbopol + Pistacia atlantica fruit oil

Bc-Oil: Bacterial cellulose + Pistacia atlantica fruit oil

Histology and inflammation quantification

The rats were selected randomly and biopsies were taken from burned tissues at three intervals on day 7, 14 and 21. The tissue samples were placed in 10% formaldehyde for 24 h and then were imbedded in paraffin. Slices (0.5 µm) were made using a microtome and were fixed on a microscope slide. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed and the stained samples were observed under a bright-field light microscope at 400× magnification. The number of neutrophils was measured based on Cantürk et al by counting the neutrophils in five different random microscopic fields [30].

Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA and t-test were performed using GraphPad prism version 5 and P-values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

Characterization of BC

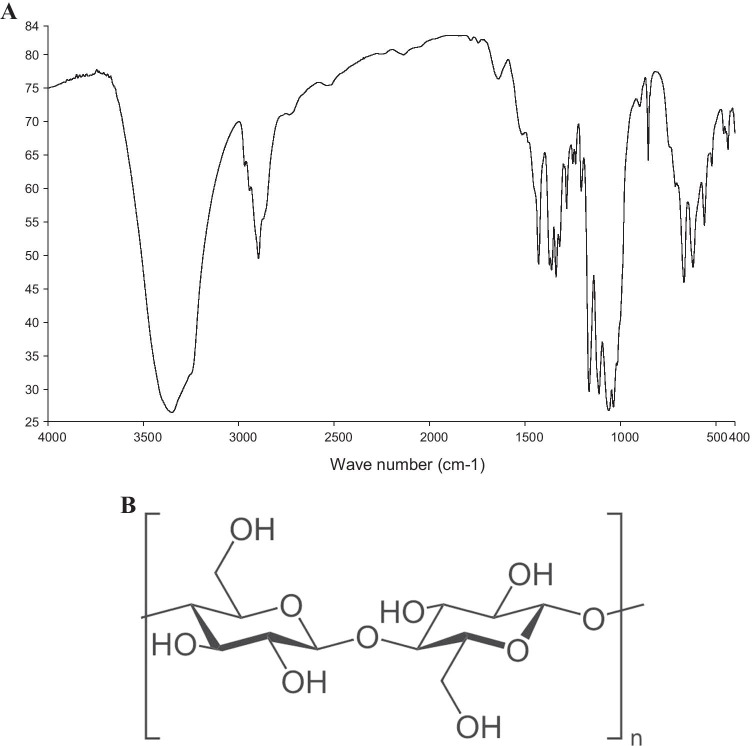

FT-IR spectrum of the bacterial cellulose and the molecular structure is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Structural analysis of the bacterial cellulose. A. FT-IR spectrum of the bacterial cellulose. B. The classic molecular structure of bacterial cellulose (This image is ineligible for

copyright and therefore in the public domain, because it consists entirely of information that is common property and contains no original authorship)

The corresponding wave numbers of the functional groups derived from FT-IR analysis is summarized in Table 1 which conformed to the standard cellulose structure. Previous studies were used to interpret the FT-IR spectrum as discussed by Choi et al. [31].

Table 1.

Summary table of corresponding wave numbers derived from FT-IR analysis

| Wave length number (cm−1) | Functional Groups |

|---|---|

| 3550–3200 | OH stretching, sharp and strong |

| 3000–2840 | C-H stretching, medium |

| 1200–1020 | C–C, C–OH, C-H vibration, strong |

Macroscopic analysis of wound closure

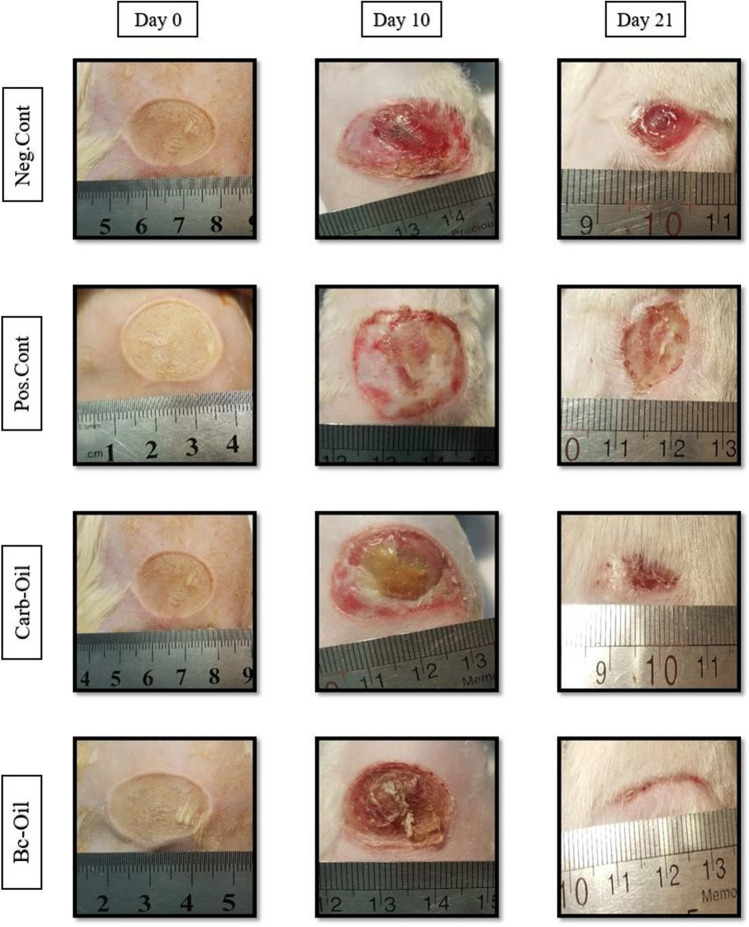

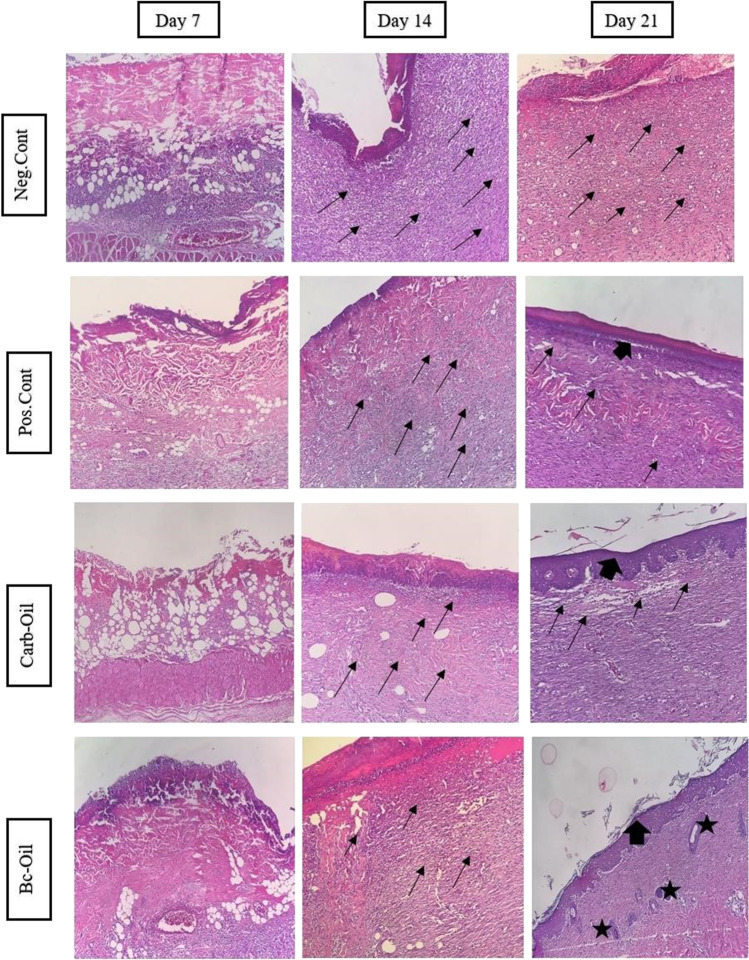

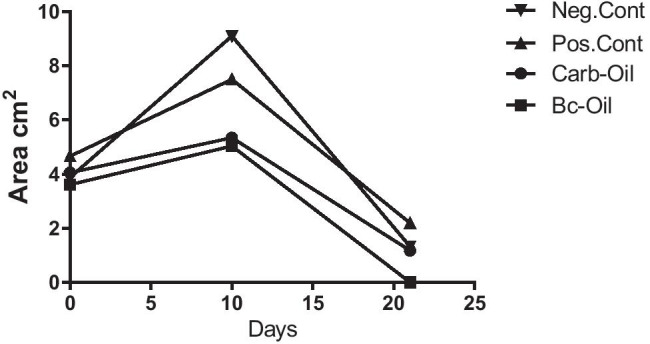

The process of wound closure was captured by a digital camera every day and the wound area was calculated by ImageJ software (v1.52h). Statistical analysis showed that there was significant difference in wound closure between the Bc-Oil group (Bacterial cellulose + Pistacia atlantica fruit oil) and the other treated groups (Figs. 2 and 3). However, there was no significant difference in wound closure when Carb-Oil treated group was compared with either positive or negative controls. It is worth mentioning that hair growth and presence of many hair follicles were observed at the wound surface in Bc-Oil group on the 21st day of the treatments (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Macroscopic observation of wound healing process from the onset of burn to 21st day of the treatments. The wounds treated with Bacterial cellulose + Pistacia atlantica fruit oil (Bc-Oil group) healed and closed faster compared with the other treated groups

Fig. 3.

Trend of surface area of wound closure over time. Image analysis showed that the wound closure in the Bc-oil-treated group (Bacterial cellulose + Pistacia atlantica fruit oil) happened in a faster fashion compared with the other treated groups (p < 0.05)

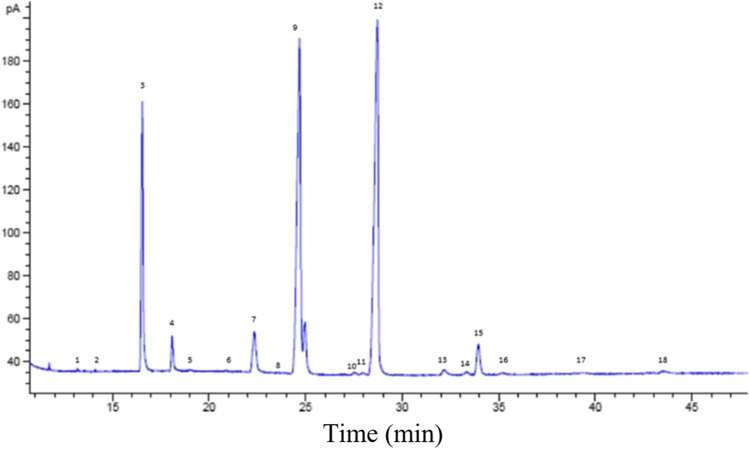

PUFAs are generally located in cell membrane phospholipids. Linoleic acid (LA) plays a role in the growth, reproduction and skin health and is the richest fatty acid in epidermal layer and also a messenger for ceramide synthesis. PUFAs monitor the process of inflammation indirectly by altering cytokine synthesis and activity. Cardoso et al. demonstrated that ALA (omega-3), LA (omega-6), and oleic acid (omega-9) modulated skin wound healing at different levels [8]. According to Table 2 and Fig. 4 the most abundant fatty acids in the Pistacia fruit oil were linoleic acid (C18:2C), oleic acid (C18:1C) and palmitic acid (C16:0).

Table 2.

Summary table of the fatty acid compositions of Pistacia atlantica oil (%)

| Fatty acid | AUC% (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|

| Myristic AME C14:0 | 0.099 ± 0.000 |

| Myristoleic AME C14:1C | 0.052 ± 0.002 |

| Palmitic AME C16:0 | 13.859 ± 0.136 |

| Palmitoleic AME C16:1C | 1.915 ± 0.021 |

| Heptadecanoic AME C17:0 | 0.101 ± 0.006 |

| cis-10-heptadecenoic AME C17:1C | 0.067 ± 0.018 |

| Stearic AME C18:0 | 3.889 ± 0.047 |

|

Elaidic acid C18:1 T |

0.065 ± 0.013 |

| Oleic AME C18:1C | 36.941 ± 0.038 |

| t-linoleic acid t-linoleic acid | 0.238 ± 0.004 |

|

t-linoleic acid C18:2 T |

0.205 ± 0.024 |

| Linoleic AME C18:2C | 38.164 ± 0.151 |

| Arachidic AME C20:0 | 0.628 ± 0.013 |

|

t-linolenic acid C18:3 T |

0.284 ± 0.003 |

| Linolenic AME C18:3C | 2.770 ± 0.019 |

| Heneicosanoic AME C21:0 | 0.189 ± 0.012 |

|

methyl cis-11,14-eicosadienoic C20:2C |

0.045 ± 0.001 |

|

methyl cis-8,11,14,eicosatrienoic AME C20:3C |

0.353 ± 0.002 |

Fig. 4.

GC analysis of Pistacia atlantica oil: 1: myristic (C14:0), 2: myristoleic (C14:1), 3: palmitic (C16:0), 4: palmitoleic (C16:1), 5: heptadecanoic (C17:0), 6: cis-10heptadecenoic (C17:1), 7: stearic (C18:0), 8: elaidic acid (C18:1), 9: oleic (C18:1), 10: tlinoleic acid, 11: t-linoleic acid (C18:2 T), 12: linoleic (C18:2), 13: arachidic (C20:0), 14: t-linolenic acid (C18:3 T), 15: linolenic (C18:3), 16: heneicosanoic (C21:0), 17: methyl cis-11,14-eicosadienoic (C20:2), 18: methyl cis-8,11,14, eicosatrienoic (C20:3C)

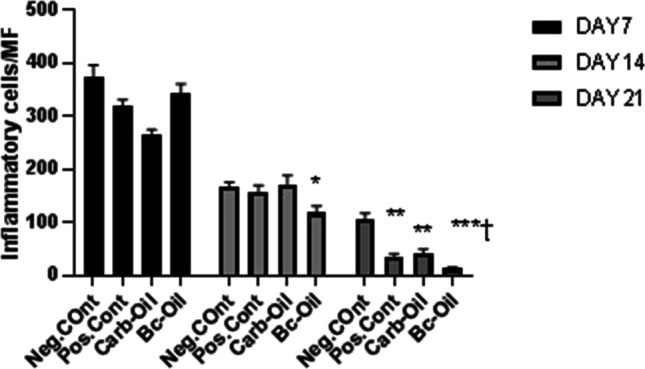

Histopathological analysis

The number of neutrophils was measured in the histological sections. Moreover, epithelialization, angiogenesis, and collagen formation were observed. However, among the studied groups, the presence of neutrophils in Bc-Oil was statistically different from the control group. The number of neutrophils which is a measure of the extent of inflammation was quantified based on Table 3. Also, epithelialization, angiogenesis, collagen formation were observed. Among the studied parameters, the presence of neutrophils in the Bc-Oil group was significantly lower on day 21 compared with Neg. Cont. (Fig. 5).

Table 3.

Neutrophil count in histopathological sections. *, **, ***: values indicate statistically significant difference between treated groups and negative control group (Neg. Cont.); †: statistically significant compared with positive control (Pos. Cont.); * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. MF: microscopic field at 400 × magnification

| Group | Inflammatory cells/3MF |

|---|---|

| Neg. Cont |

374.2 ± 21.7 (7 d) 165.8 ± 9.2 (14 d) 106.5 ± 10.2 (21 d) |

| Pos. Cont |

319.6 ± 11.5 (7d) 157.2 ± 12.4 (14 d) 34.2 ± 6.4 (21 d) ** |

| Carb-Oil |

265.8 ± 8.4 (7 d) 171.5 ± 16.8 (14 d) 41.5 ± 7.7 (21 d) ** |

| Bc-Oil |

343.1 ± 17.5 (7 d) 117.4 ± 13.2 (14 d) * 12.6 ± 2.4 (21 d) ***† |

Fig. 5.

Measurement of inflammatory cells (neutrophils) per microscopic fields post-treatment on days 7, 14 and 21. The number of neutrophils as a measure of inflammation was counted in the histological sections and statistical analysis was done using one-way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism. *, **, ***: values indicate statistically significant difference between treatment group and negative control group (Neg. Cont.); †: statistically significant compared with positive control (Pos. Cont.); MF: Microscopic field; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001

The data showed that treatment with bacterial cellulose coated with Pistacia fruit oil alleviated inflammation and facilitates wound healing (Fig. 6). The number of inflammatory cells was significantly fewer in Bc-Oil group on day 21 compared with the other groups. Epidermal layer and hair follicles were present in Bc-Oil group. Histopathological evaluation at day 7 showed severe infiltration of inflammatory cells into the wound area in all the groups. At day 14, the number of inflammatory cells was significantly reduced in wound area in the Bc-Oil group compared to the other groups. Finally, at day 21 post-treatment, the epithelialization process was completed and the inflammatory cells were significantly reduced in comparison to the Neg.Cont (Fig. 5). The trend of reduction of inflammation in Carb-Oil and Pos. Cont. groups at 7, 14 and 21 days post-treatment were similar and the number of neutrophils infiltrated to the wound area reduced over time (Fig. 5). However, this healing process happened faster in the group treated with Bacterial cellulose + Pistacia atlantica fruit oil (Bc-Oil).

Fig. 6.

H&E stained microscopic sections of burn wounds treated with either silver sulfadiazin (Pos. Cont.), Carbopol hydrogel + Pistacia atlantica fruit oil (Carb-Oil), Bacterial cellulose + Pistacia atlantica fruit oil (Bc-Oil) or left untreated (Neg. Cont.). The number of inflammatory cells was significantly fewer in Bc-Oil group on day 21 compared with the other groups. Epidermal layer and hair follicles were present in Bc-Oil group. Thin arrows: infiltration of inflammatory cells, black thick arrow: epidermal layer. Stars indicate the presence of the hair follicles

Discussion

Natural wound healing without any intervention depends on a variety of factors that occur sequentially in a particular order [32]. However, many factors, including bacterial infections, can delay and complicate wound healing if left untreated [33]. The whole concept of using wound dressings is to speed up the process and physically protect the irritated area from post-wound problems [34]. In this study, the wound healing and anti-inflammatory effects of bacterial cellulose coated with Pistacia atlantica fruit oil have been investigated in an in vivo burn wound model. Previous studies on the chemical composition of Pistacia atlantica oil have shown that the fatty acid components were important bioactive molecules with skin health benefits. They play key role in regulating epithelialization in wound healing processes [7, 35]. Pistacia atlantica fruit oil has been reported to have antioxidant properties due to its total phenol content [36]. Djerrou et al. [37] showed that Pistacia atlantica oil significantly facilitated the contraction of the wound and epithelial layer formation in a rabbit model. Pistacia atlantica oil in combination with the oils from other plants including Sesamum indicum, Cannabis sativa, Juglans regia has been reported to improve wound contraction in an animal model using exposure to boiling water [38]. As opposed to Pistacia lentiscus, P. atlantica is indigenous to Iran [39, 40]. Although, geographical and ecological conditions may affect the metabolites of medicinal plants, the data in our study showed that fatty acid composition of Pistacia atlantica fruit oil indigenous in South Khorasan Province, Iran has similar fatty acid profile of Pistacia atlantica in other regions including Fars, Isfahan, and Kohkeloye Boyerahmad provinces in Iran.

Silver sulfadiazine (SSD) has been used as positive control in this study. SSD is widely used for the treatment of burn wounds in the clinical settings and animal models. Besides its antimicrobial properties, there are several studies showing that SSD promotes early phase of wound healing and subsequent epithelialization processes [41, 42]. However, there are contradictory data in the literature on whether SSD promotes wound healing or exerts deleterious effects on healing processes [43]. Our data showed that SSD stimulated wound closure and promoted anti-inflammatory processes in a retarded pace compared to the sample, bacterial cellulose coated with the oil (Figs. 2, 3 and 5, and Table 3).

Acute inflammation is the consequence of various conditions including infection, trauma and burn injury. It has been shown that own innate immunity can be provoked during inflammation and persistence presence of immune cells such as neutrophils can aggravate the situation. Long term presence of neutrophils and secretion of several enzymes and reactive oxygen species causes tissue damage and this pattern of inflammation repeats itself in several animal models including arthritis, colitis and periodontitis models [30]. Our histological data showed that bacterial cellulose coated with Pistacia atlantica oil significantly decreased the number of neutrophils present in the injured tissue and wound healing and anti-inflammatory effects were more evident upon treatment after 21 days. Although, Pistacia atlantica oil formulated with Carbopol had anti-inflammatory effects, bacterial cellulose and the plant oil synergistically exerted much higher impact in terms of healing and alleviating the inflammation (Figs. 5 and 6).

Conclusion

The results showed that bacterial cellulose coated with Pistacia atlantica fruit oil can be a potential bio-safe dressing for wound management and reduction of neutrophil-mediated inflammatory processes. The study revealed that the most abundant fatty acids in a Pistacia oil were linoleic acid (C18:2C), oleic acid (C18:1C) and palmitic acid (C16:0). Although many wound management approaches are available, need for accelerated wound healing still exists, especially for severe burned cases. Bacterial cellulose is a biocompatible polymer which can be coated with therapeutics such as wound healing products and can be commercialized as a wound dressing.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to sincerely thank Dr. Mohsen Amini for his assistance in GC analysis. We appreciate the collaboration of Dr. Gholamreza Amin for identifying the plant species and assigning scientific name.

Funding

National Institutes of Medical Research Development (NIMAD 958943).

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Ethical approval

An animal study was conducted based on ethical guidelines of Iran National Committee for Ethics in Biomedical Research (IR.TUMS.MEDICINE.REC.1399.1194).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Farhoosh R, Khodaparast MHH, Sharif A. Bene hull oil as a highly stable and antioxidative vegetable oil. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2009;111(12):1259–1265. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.200900081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farhoosh R, Tavassoli-Kafrani MH, Sharif A. Antioxidant activity of the fractions separated from the unsaponifiable matter of bene hull oil. Food Chem. 2011;126(2):583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.11.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delazar A, Reid RG, Sarker SD. GC-MS Analysis of the Essential Oil from the Oleoresin of Pistacia atlantica var. mutica. Chem Nat Compd. 2004;40(1):24–27. doi: 10.1023/B:CONC.0000025459.72590.9e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khedir SB, Bardaa S, Chabchoub N, Moalla D, Sahnoun Z, Rebai T. The healing effect of Pistacia lentiscus fruit oil on laser burn. Pharm Biol. 2017;55(1):1407–1414. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2016.1233569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charef M, Yousfi M, Saidi M, Stocker P. Determination of the Fatty Acid Composition of Acorn (Quercus), Pistacia lentiscus Seeds Growing in Algeria. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2008;85(10):921–924. doi: 10.1007/s11746-008-1283-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGaw L, Jäger A, Staden J, Houghton PJ. Antibacterial effects of fatty acids and related compounds from plants. S Afr J Bot. 2002;68:417–423. doi: 10.1016/S0254-6299(15)30367-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribeiro Barros Cardoso C, Aparecida Souza M, Amália Vieira Ferro E, Favoreto JRS, Deolina Oliveira Pena J. Influence of topical administration of n-3 and n-6 essential and n-9 nonessential fatty acids on the healing of cutaneous wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2004;12(2):235–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.012216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang TH, Wang PW, Yang SC, Chou WL, Fang JY. Cosmetic and Therapeutic Applications of Fish Oil’s Fatty Acids on the Skin Mar Drugs. 2018;16(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Czaja W, Krystynowicz A, Bielecki S, Brown RM., Jr Microbial cellulose–the natural power to heal wounds. Biomaterials. 2006;27(2):145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iguchi M, Yamanaka S, Budhiono A. Bacterial cellulose—a masterpiece of nature's arts. J Mater Sci. 2000;35(2):261–270. doi: 10.1023/A:1004775229149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jayabalan R, Malbaša RV, Lončar ES, Vitas JS, Sathishkumar M. A Review on Kombucha Tea—Microbiology, Composition, Fermentation, Beneficial Effects, Toxicity, and Tea Fungus. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2014;13(4):538–550. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abeer MM, Mohd Amin MC, Martin C. A review of bacterial cellulose-based drug delivery systems: their biochemistry, current approaches and future prospects. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2014;66(8):1047–1061. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pértile RAN, Moreira S, Gil da Costa RM, Correia A, Guãrdao L, Gartner F, Vilanova M, Gama M. Bacterial Cellulose: Long-Term Biocompatibility Studies. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2012;23(10):1339–1354. doi: 10.1163/092050611X581516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin N, Dufresne A. Nanocellulose in biomedicine: Current status and future prospect. Eur Polym J. 2014;59:302–325. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2014.07.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrade FK, Alexandre N, Amorim I, Gartner F, Maurício AC, Luís AL, Gama M. Studies on the biocompatibility of bacterial cellulose. J Bioact Compat Polym. 2013;28(1):97–112. doi: 10.1177/0883911512467643. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fontana JD, de Souza AM, Fontana CK, Torriani IL, Moreschi JC, Gallotti BJ, de Souza SJ, Narcisco GP, Bichara JA, Farah LF. Acetobacter cellulose pellicle as a temporary skin substitute. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 1990;24–25:253–264. doi: 10.1007/BF02920250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin Y-K, Chen K-H, Ou K-L, Liu M. Effects of different extracellular matrices and growth factor immobilization on biodegradability and biocompatibility of macroporous bacterial cellulose. J Bioact Compat Polym. 2011;26(5):508–518. doi: 10.1177/0883911511415390. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bäckdahl H, Helenius G, Bodin A, Nannmark U, Johansson BR, Risberg B, Gatenholm P. Mechanical properties of bacterial cellulose and interactions with smooth muscle cells. Biomaterials. 2006;27(9):2141–2149. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Novaes AB, Jr, Novaes AB. Immediate implants placed into infected sites: a clinical report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1995;10(5):609–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Picheth GF, Pirich CL, Sierakowski MR, Woehl MA, Sakakibara CN, de Souza CF, Martin AA, da Silva R, de Freitas RA. Bacterial cellulose in biomedical applications: A review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;104(Pt A):97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.05.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gore MA, Akolekar D. Evaluation of banana leaf dressing for partial thickness burn wounds. Burns. 2003;29(5):487–492. doi: 10.1016/S0305-4179(03)00050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghosh A, Bharat R. Domestic burns prevention and first aid awareness in and around Jamshedpur, India: strategies and impact. Burns. 2000;26(7):605–608. doi: 10.1016/S0305-4179(00)00021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen C, Liu BY. Changes in major components of tea fungus metabolites during prolonged fermentation. J Appl Microbiol. 2000;89(5):834–839. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Treviño-Garza MZ, Guerrero-Medina AS, González-Sánchez RA, García-Gómez C, Guzmán-Velasco A, Báez-González JG, Márquez-Reyes JM. Production of Microbial Cellulose Films from Green Tea (Camellia Sinensis) Kombucha with Various Carbon Sources. Coatings. 2020;10(11):1132. doi: 10.3390/coatings10111132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meftahi A, Nasrolahi D, Babaeipour V, Alibakhshi S, Shahbazi S. Investigation of Nano Bacterial Cellulose Coated by Sesamum Oil for Wound Dressing Application. Procedia Mater Sci. 2015;11:212–216. doi: 10.1016/j.mspro.2015.11.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shouqin Z, Junjie Z, Changzhen W. Novel high pressure extraction technology. Int J Pharm. 2004;278(2):471–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andritsou V, de Melo EM, Tsouko E, Ladakis D, Maragkoudaki S, Koutinas AA, Matharu AS. Synthesis and Characterization of Bacterial Cellulose from Citrus-Based Sustainable Resources. ACS Omega. 2018;3(8):10365–10373. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.8b01315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rossi F, Santoro M, Casalini T, Veglianese P, Masi M, Perale G. Characterization and Degradation Behavior of Agar-Carbomer Based Hydrogels for Drug Delivery Applications: Solute Effect. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12(6):3394–3408. doi: 10.3390/ijms12063394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.AzimzadehAsiabi P, Ramazani A, Khoobi M, Amin M, Shakoori M, MirmohammadSadegh N, Farhadi R. Regenerated silk fibroin-based dressing modified with carnosine-bentonite nanosheets accelerates healing of second-degree burn wound. Chem Pap. 2020;74(10):3243–3257. doi: 10.1007/s11696-020-01155-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cantürk NZ, Vural B, Cantürk Z, Esen N, Vural S, Solakoglu S, Kirkal G. The role of L-arginine and neutrophils on incisional wound healing. Eur J Emerg Med. 2001;8(4):311–315. doi: 10.1097/00063110-200112000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi Y-J, Ahn Y, Kang M-S, Jun H-K, Kim IS, Moon S-H. Preparation and characterization of acrylic acid-treated bacterial cellulose cation-exchange membrane. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2004;79(1):79–84. doi: 10.1002/jctb.942. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nayak S, Nalabothu P, Sandiford S, Bhogadi V, Adogwa A. Evaluation of wound healing activity of Allamanda cathartica. L. and Laurus nobilis. L. extracts on rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Albayrak A, Demiryilmaz I, Albayrak Y, Aylu B, Ozogul B, Cerrah S, Celik M. The role of diminishing appetite and serum nesfatin-1 level in patients with burn wound infection. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15(5):389–392. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.4198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campos L, Mansilla M, Chica A. Topical chemotherapy for the treatment of burns. Rev enferm. 2005;28:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mao-Qiang M, Elias PM, Feingold KR. Fatty acids are required for epidermal permeability barrier function. J Clin Invest. 1993;92(2):791–798. doi: 10.1172/JCI116652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Givianrad MH, Saber-Tehrani M, JafariMohammadi SA. Chemical composition of oils from wild almond (Prunus scoparia) and wild pistachio (Pistacia atlantica) GRASAS ACEITES. 2013;64(1):77–84. doi: 10.3989/gya.070312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Djerrou Z, Maameri Z, Hamdi-Pacha Y, Serakta M, Riachi F, Djaalab H, Boukeloua A. Effect of virgin fatty oil of Pistacia lentiscus on experimental burn wound's healing in rabbits. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2010;7(3):258–263. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v7i3.54788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mehrabani M, Seyyedkazemi SM, Nematollahi MH, Jafari E, Mehrabani M, Mehdipour M, Sheikhshoaee Z, Mandegary A. Accelerated Burn Wound Closure in Mice with a New Formula Based on Traditional Medicine. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;18(11):e26613. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.26613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mozaffarian V. A dictionary of Iranian plant names. Tehran: Farhang Moaser; 1996. p. 396. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khatamsaz M. Flora of Iran. [Koenigstein, W. Germany]: Ministry of Agriculture, Iran; 1991.

- 41.O'Meara SM, Cullum NA, Majid M, Sheldon TA. Systematic review of antimicrobial agents used for chronic wounds. Br J Surg. 2001;88(1):4–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2001.01631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Atiyeh BS, Costagliola M, Hayek SN, Dibo SA. Effect of silver on burn wound infection control and healing: review of the literature. Burns. 2007;33(2):139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burd A, Kwok CH, Hung SC, Chan HS, Gu H, Lam WK, Huang L. A comparative study of the cytotoxicity of silver-based dressings in monolayer cell, tissue explant, and animal models. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15(1):94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2006.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.