Abstract

Spoilage fungi were isolated from the skin and the muscle of smoke-dried catfish samples, which were products of traditional and improved processing methods. The samples significantly different mean aw of 0.85 and 0.81 respectively [F (1, 3) = 0.014, P = 0.018], when they were checked immediately after purchase from selected open markets. The isolated spoilage fungi were identified by their phenotypic appearance and morphological features under microscope, with reference to standard identification guidelines. The isolates comprised of Aspergillus fumigatus, A. niger, A. flavus and Penicillium species. Effects of water activity (aw) on growth and sporulation of these species at ambient temperature (25 ± 5 °C) were studied on standard media (aw = 0.995) or media in which aw was modified using NaCl as follows: 0.98, 0.94, 0.86 and 0.80. All the isolates could grow in the range of the aw studied and there were statistically significant variabilities in the rates of growth among species [F (7, 50) = 63.34, P = 0.001] and in relation to media aw [F (28, 50) = 4.055, P = 0.001]. There was no limitant aw found in the studied conditions (0.995–0.80 aw x fluctuating ambient temperature, 25 ± 5 °C), as all the isolates were fast growing. The aw of the fish samples from the improved processing line was lower than those from the traditional processing lines. However, the aw of all the tested the samples was above the Codex Standard for smoked fish, smoke-flavoured fish and smoke-dried fish, which is 0.75 aw or less (10% moisture or less), as necessary to control bacteria pathogens and spoilage fungi. The results indicated that the open market fish samples may pose serious health risks if they are consumed after a short-term storage.

Research Highlights

Tolerance of smoke-dried fish spoilage fungi to water stress

Effect of aw on growth characteristics of smoke-dried fish spoilage fungi

Water activity relations of some spoilage fungi from dried fish

Keywords: Water activity, Spoilage fungi, Growth, Sporulation, Fish processing

Introduction

Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) is a major source of animal protein in Nigeria, having amino acid composition comparable with egg, cow milk, meat products and contains significant amounts of minerals and unsaturated fat (Osibona et al. 2009). It is a freshwater fish that is largely cultivated by peasant and large scale farmers and highly perishable when refrigeration or preservation processes are delayed after catch. Postharvest handling and processing of catfish to be sold in markets are unregulated in Nigeria and no government licenses are required by processors at any stage of value-addition and eventual storage. Smoke-drying is the predominant method of preservation. (Foline et al. 2011) and traditionally, the fish is rolled-up with the tail fixed into the mouth, followed by smoking on fire made with wood shavings. In large scale processing lines, here considered as improved method, the visceral organs of fish are removed and treated with culinary seasoning materials or soaked in brine containing sodium glutamate before smoking. In either case, there is usually no check of the final safe moisture content before packaging and storage.

Unregulated handling in the postharvest line after catch and non-adherence to standardized processing techniques are responsible for variabilities in qualities, especially the moisture content (Ikutegbe and Sikoki 2009) and the microbial profiles (Adebayo-Tayo et al. 2008) of smoke-dried fish available in markets. The heating and the dehydration that occur during smoke-drying (Benjakul and Aroonrueng 1999) are likely to reduce microbial load and create water stress against growth of microorganisms and significantly inhibit development of spoilage bacteria species. More importantly, antibacterial components of smoke, especially, aldehyde and phenol acids and derivatives (Suñen et al. 2001) are likely to exert antimicrobial effects on bacteria species more than the fungal microflorals. Effective drying to a safe water activity level (Parra and Magan, 2004) may be more effective in preventing spoilage by fungi.

Apart from degradation of proteins through enzymatic reactions that are responsible for autolysis before drying and development of oxidative rancidity in intermediate moisture fish products, spoilage by microorganisms (Marshall and Kim 1996; Gram 2009) are responsible for a significant loss of smoke-dried fish in storage. The rate of microbial degradation of intermediate moisture fish, such as smoke-dried, would depend on their microbial profile and load and the adaptability of the spoilage organisms to exploit favourably the moisture environment (Pitt and Hocking 2009). While bacterial activities are likely to be reduced in intermediate moisture fish, spoilage fungi have evolved greater ecological adaptations to thrive under different moisture conditions, including very low moisture levels (Andrews and Pitt 1987; Santos et al. 2017). Thus spoilage of smoke-dried fish products in storage could occur in the presence of xeromorphic spoilage fungi, which are adaptable to growth, sporulation and toxin production under marginally favourable interacting abiotic factors (Farag et al., 2011). Methods of handling that expose smoke-dried fish to re-contamination after initial heat treatment (smoke-drying) are likely to reduce shelve life in storage.

Smoke-dried fish products are usually stored in exposed jute sacks and woven raffia baskets in open markets in Nigeria. While this method of handling is likely to facilitate continuous drying in low relative humidity (RH) environments, the risk of microbial recontamination is enormous. Under high RH humidity conditions, initially dried products could hygroscopically pick-up moisture from the air and facilitate microbial deterioration. Microbial deterioration often result in development of toxins in food, when toxigenic strains of microbes are involved. Edema and Agbon (2010) reported the potential toxigenic species that are associated with dried fish products and the likely health effects on consumers. The natural microfloral of fresh fish samples that are responsible for its rapid deterioration after catch are well known but the microbial profiles may change significantly during postharvest handling practices, which may expose the fish to contamination from equipment in the value-addition processing line.

Heat processing is known to alter proximate composition and moisture content (Foline et al. 2011), which could select species that are adaptable to prevailing aw of the smoke-dried samples. Spoilage molds of smoke-dried fish samples are expected to be predominantly xeromorphs or halotolerant species, when the processing stages include brine treatments. However, there are no studies that profiled the spoilage fungi of smoke-dried catfish in relation to the methods of postharvest handling and processing.

Catfish are predominantly reared in artificial earthen or concrete ponds in Nigeria and incidents of infections among consumers caused by contaminated fresh water fish (Gauthier 2015) have not been reported as a threat. Health risks to consumers in relation to fresh water fish consumption may likely occur among consumers of processed, stored and intoxicated products and the impact could be enormous when postharvest handling and processing methods render fish products into the form that select toxigenic fungal species. The method of packaging, which involves sealing of processed fish in non-perforated cellophane bag, as alternative to open storage practice in Nigeria, creates relative anaerobic condition which could either stimulate fungal growth and toxin production depending on the aw of the product (Magan and Lacey 1984), the contaminant microbes and duration of storage. Slightly elevated carbon dioxide concentrations and its interaction with temperature and aw have been shown to stimulate growth of mycotoxigenic species in some food products (Giorni et al. 2008).

As far as we know, water activity relations of spoilage fungi associated with smoke-dried catfish sold in open markets in Nigeria have not been profiled. Also, there is no data on the aw boundaries of species in relation to growth and sporulation, which can be useful in defining safe moisture and storage requirements for local processors. Thus, the aim of this study is to isolate fungal species from smoke-dried fish samples collected from open markets and profile their aw requirements necessary for growth and sporulation. This kind of data is clearly necessary in defining the safe moisture requirements for effective preservation and storage of smoke-dried freshwater fish products and a useful guide to extensionists working on food safety.

Materials and methods

Source of smoke-dried C. gariepinus fish samples

The sellers in the open market described the smoke-dried fish samples as products of two different processing lines, here presented as the traditional and the improved methods. The two processing lines are described in process flow chart. The traditional processing method is a two-stage process; the fishes are piled up and are left to die by oxygen starvation after catch, followed by curling with the tail tucked in the mouth and fixed with a wooden peg before smoke-drying. The smoke is generated from fired wood shavings and charcoal and the end of the smoking process is arbitrary, usually at the discretion of the untrained processor.

Process flow-chart of traditional and improved post-catch handling of catfish as described by handlers

In the improved processing method, the fish samples are killed by impact force applied to the head region followed by slitting the throat and removal of visceral organs (dressing), pre-cleaning with hot water to remove blood and slime from the skin, curling the fish tail-to-mouth without wooden pegs, soaking in brine or seasoning recipe, oven drying, cooling and packaging in sealable polyethylene bags or stored in open baskets. We measured the peak temperature of typical 1.5 kg charcoal-powered kiln (commonly used) from ten processors using infrared thermometer (Craftsman mini Infrared Thermometer, 500 Degree) in order to determine the processing temperature to which the fish samples were subjected in the production line.

Collection of fish samples and determination of water activity

Twenty samples of fish processed using either the traditional or the improved methods were randomly collected from different sales outlets and the aw of the samples was determined using Water Activity Meter (AQUALAB 4TE, Accuracy = ± 0.003 aw). The aw of products from the two processing lines were compared.

Isolation of fungi from fish samples

Standard Sabouraud Dextrose Agar media (Sigma-Aldrich, aw = 0.995; pH = 5.6), containing 0.05% chloramphenicol (CSDA) for selective isolation of food fungi was prepared and poured into 9 cm disposable Petridishes. Samples of the skin and the flesh (muscle) of the fish samples stored in sealable cellophane bags for 14 days were removed using a scalpel. The skin was cut into approximately 0.5 cm2 subsamples, surface-sterilized using 80% ethanol and transferred unto the selective media. The muscle samples were equally surface-sterilized and placed on the selective media. Unsterilized samples of the skin and the muscle were prepared and transferred into the selective media. The plates were sealed with Parafilm and incubated at ambient temperature (25 ± 2 °C) for 5–7 days. Where the cultures yielded growth, the fungi were subcultured on SDA and purified using the optimized single spore isolation technique described by Zhang et al. (2013).

Identification of fungal isolates

The fungal isolates were cultured on Malt Extract Agar (MEA) and incubated at 25 °C for 6 days. Thereafter, the fungal cultures were identified using their phenotypic appearance, including colour and colony morphology on Malt Extract Agar (MEA). Microscope slides were prepared and micromorphology was observed under microscope, with reference to identification guides for food fungi (Samson et al., 2010) and the illustrated genera of imperfect fungi (Barnett and Hunter, 1998).

Effects of aw on growth and sporulation

Standard SDA (0.995 aw) and NaCl-modified SDA media (NaCl-SDA) (aw = 0.98, 0.94, 0.86 and 0.80), containing calculated amounts of laboratory grade sodium chloride were prepared and poured into 9 cm disposable Petridishes. The aw of the media was checked using Water Activity Meter and they were accurate within 0.002 aw of the target levels. Conidia suspension of 14 days old isolate was prepared using sterile distilled water containing 0.02% polyoxyethylene sorbitan monoleate (Tween 80®) and standardized to 1 × 103 conidia ml−1. The standard SDA plates and the NaCl-SDA plates were inoculated at the Centre with 10 µl of the prepared conidia suspension using Micropipette (10–200 µl, Eppendorff®). The plates were left open in Laminar flow Cabinet for 15 min to dry, covered thereafter with the lid and sealed with Parafilm. Incubation was done at ambient temperature for 10–14 days and radial extension of the culture was measured after 24 h incubation and repeated daily for 10 days along two orthogonal axes drawn at the back of the Petridish. The data of the radial extension of the culture was plotted against the incubation period and the slope of the exponential growth phase was used to estimate growth in a linear model (Borisade and Magan 2014). Agar plugs (1 cm2) were taken from five positions on 14 days old culture growing at 0.98 aw in 9 cm Petridish into 10 ml sterile distilled water containing 0.02% Tween 80® in a Falcon bottle and vortexed for 1 min to dislodged the spores. Serial dilutions were made where necessary and spores were counted using improved Neubauer Haemocytometer. The number of conidia cm−2 of colony area was estimated.

Statistical analysis

The data on the rates of growth of the fungal isolates at different water activity levels and the number of conidia produced cm−2 colony area were subjected to Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Where there were statistically significant differences, a Post-hoc test was conducted to separate the means, using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) statistical procedure.

Results

Isolated fungal species

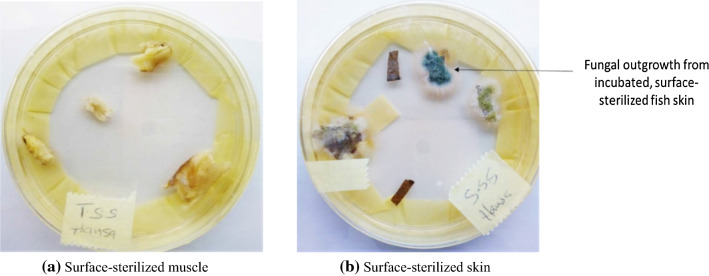

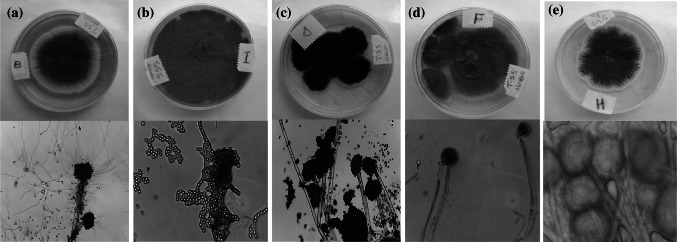

The surface-sterilized skin and muscle of the fish samples and the unsterilized yielded growth after 24–48 h incubation at 25 °C. Representative plates of the samples on CSDA media is shown in Fig. 1 and the data is based on surface sterilized samples only. Unsterilized samples yielded yeast colonies that impaired isolation of fungal specimens. Fungal isolates were predominantly Aspergillus species, consisting of Aspergillus fumigatus, Penicillium sp, A. niger, A. flavus, and yellow pigment-producing Aspergillus sp, with representative phenotypic and micromorphological appearance of some of the isolates shown in Fig. 2. Two strains of A. fumigatus and a strain each of A. niger and A. flavus were detected in the tissue of the fish samples processed by the traditional method, while A. flavus, A. parasiticus and Penicillium sp were isolated from the skin samples. These species were considered as different strains based on variabilities in their rates of growth at the same aw, in addition to phenotypic differentiations. Aspergilus niger was the only fungus isolated from the tissue of the samples processed using the improved method but A. flavus and A. niger were isolated from the skin (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Growing fungi on fish samples placed on CSDA after three days incubation period

Fig. 2.

Phenotypic and micromorphological characters of fungal species isolated from smoke-dried catfish: a Aspergillus fumigatus b Penicillium sp. c A. niger d A. flavus and e yellow pigment-producing Aspergillus sp

Table 1.

Fungal species isolated from fish samples processed using traditional and improved methods

| Source of fungal isolates | Processing method | Fungal isolates | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | ||

|

Tissue Skin |

Traditional | + + | + + | – | + + | – | + + | + + | – |

| – | – | + + | + + | + + | – | – | + + | ||

|

Tissue Skin |

Improved method | – | – | – | + + | – | – | – | – |

| – | – | – | + + | + + | + + | – | – | ||

+ + = Fungal isolate present

– = Fungal isolate not present

Key: A = Aspergillus fumigatus strain 1, B = Aspergillus fumigatus strain 2, C = Aspergillus parasiticus, D = Aspergillus niger strain 1, E = Aspergillus niger strain 2, F = Aspergillus flavus, G = Aspergillus sp., H = Penicillium sp

Water activity of Samples

The mean aw values of fish samples from the traditional and the improved processing lines were 0.85 and 0.81 respectively. These values were significantly different statistically, regardless of the source of collection [F (1, 3) = 0.014, P = 0.018] (Table 2).

Table 2.

The mean aw of fish samples processed using traditional and improved methods

| Processing Methods | |

|---|---|

| Traditional Processing | Improved processing |

| Mean aw of samples | |

| 0.85a | 0.81b |

Growth and aw relations

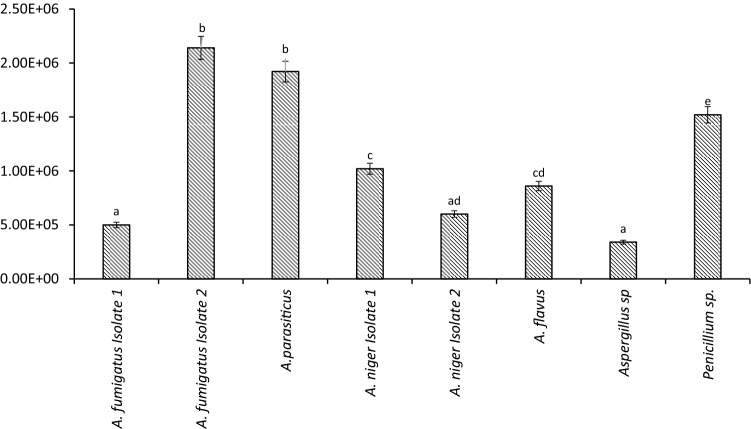

Table 3 shows the growth rates of the fungal isolates at 0.995 aw when water was freely available in the media and at different levels of water stress: aw = 0.98, 0.94, 0.86 and 0.80. All the isolates could grow in the range of the aw studied and there were statistically significant variabilities in the rates of growth among isolates [F (7, 50) = 63.34, P = 0.001] and in relation to interacting aw (F (28, 50) = 4.055, P = 0.001]. The growth rates of the two isolates of A. fumigatus were not significantly different at 0.995–0.80 aw, which on the average were 7.8 mm day−1 (Isolate 1) and 8.1 mm day−1 (isolate 2) and no optimal aw could be indicated. The lowest growth of A. parasiticus (4.8 mm day−1) occurred at 0.995 aw and the optimal aw was 0.94, at which growth was 1.2 mm day−1.The optimal aw for the growth of the two isolates of A. niger, Isolate 1 and Isolate 2 was 0.94 and their growth rates were comparable, 20.4 mm day−1 and 21.9 mm day−1 respectively. However, the growth of these two isolates decreased as the water stress increased, 0.86–0.80 aw. The A. flavus tolerated the water aw range, 0.995–0.80 without significant variabilities in the rates of growth. The optimal aw for the growth of the yellow pigment-producing strain of Aspergillus was 0.94 (growth = 22.1 mm day−1) and comparably, the growth decreased significantly at 0.86 and 0.80 aw. The optimal water activity for growth of the Penicillium species was 0.94–0.80 and the growth rates within the aw range was consistent. The lowest rate of growth was recorded in all the isolates at 0.995–0.98 aw levels. All the isolates sporulated differentially at 0.98 aw [F(7,8) = 35.31, P = 0.001] and the A. fumigatus isolate 2 and A. parasiticus appeared more adaptable to sporulation at 0.98 aw; they produced 2.14 × 106 and 1.92 × 106 conidia cm−2 colony area respectively, which was significantly higher than the number of spores produced by the other isolates (Fig. 3). The A. fumigatus strain 1 and the yellow pigment-secreting strain of Aspergillus species produced the least number of spores, 5.0 × 105 and 3.4 × 105 conidia cm−2 colony area respectively. The other isolates, Penicillium sp, A. flavus and A. niger produced 1.52 × 106, 8.60 × 105 and 6.0 × 105 conidia cm−2 colony area respectively.

Table 3.

Growth rates (mm/day) of fungal isolates at different aw regimes

| Fungal isolates | Water activity levels | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.995 aw | 0.98 aw | 0.94 aw | 0.86 aw | 0.80 aw | |

| A. fumigatus Isolate 1 | 6.97a | 8.75a | 8.38a | 7.13a | 7.38a |

| A. fumigatus Isolate 2 | 8.60a | 9.13a | 9.65a | 8.58a | 8.88a |

| A. parasiticus | 4.83a | 9.55a,b | 12.00b | 11.50b,c | 9.75a,b |

| A. niger Isolate 1 | 13.25a | 18.53b,c | 20.38b | 17.30c | 17.40c,d |

| A. niger Isolate 2 | 16.25a,c | 19.65a,b | 21.85b | 20.00a,b | 13.75c |

| A. flavus | 15.60a | 15.45a | 16.42a | 16.90a | 15.00a |

| Aspergillus sp. | 12.87a | 18.63a,b | 22.10b | 18.85a,b | 11.78a |

| Penicillium sp | 10.35a | 10.88a | 15.18b | 15.45b | 14.95b |

Fig. 3.

Sporulation rates of fungal species isolated from smoke-dried catfish after two weeks storage

Discussion

This study showed the profile of fungal species associated with smoke-dried and oven-dried catfish sold in open markets in Nigeria and demonstrated the aw relations of some of these indigenous isolates for the first time. The fungal species were predominantly Aspergillus group, representing 87.5% of the species and a species of Penicillium. Earlier reports on microfloral of salted, smoke-dried catfish sold in open markets in Nigeria indicated consistent occurrence of Aspergillus and Penicillium species, including toxigenic strains (Adebayo-Tayo et al. 2008).

The post-harvest handling process-flow chart was described by the peasants and specifics on drying temperature, duration of smoking or oven-drying were not provided. However, subjecting fresh fish samples to brine treatments and the typical drying temperature of charcoal-powered kiln used for traditional and improved fish processing, 100–140 °C and the duration, 10–15 h (Omodara et al. 2016) can be expected to kill potential spoilage fungi. Thus, it can be suggested that most spoilage fungi reported on the smoke-dried fish samples occurred during postharvest handling and improper storage. The modern processing method included removal of the visceral organs of the fish, which could reduce the microbial load of samples (Emikpe et al. 2011) and the bleeding process can also facilitate drying during heat treatment. Thus, the improved processing methods can be perfect for preservation, provided that the samples are allowed to dry to a safe moisture level and re-contamination is prevented.

The fish samples examined in this study were freshly dried and stored for 14 days only before evaluation, which may account for the low fungal biodiversity. Five important spoilage fungi which were capable of growing on smoke-dried fish samples were isolated. The microbial profile is expected to increase with storage period and duration of exposure in the open market. Abolagba and Igbinevbo (2010) reported increased diversity of spoilage fungus associated with smoke-dried fish samples in open markets in relation with period of storage while Adebayo-Tayo et al. (2008) recorded Aspergillus as the dominant species in earlier studies elsewhere, which is in agreement with the findings in this report.

In this study, mycellial growth of A. fumigatus isolates and A. flavus was not significantly affected at 0.995–0.80 aw and all the isolates could grow at the lowest aw level examined (0.80 aw), which is even below the water activity of the samples collected from the market. The optimum aw for the growth of other Aspergillus isolates was 0.94, while the Penicillium sp was growing optimally at 0.94–0.80 aw and all the fungi produced secondary spores at 0.98 aw. Their ability to sporulate indicate potential spread of infection in storage or contamination of newly processed fish samples. The results indicate that open market fish samples may pose a serious health risk to consumers, considering the xeromorphic nature of the associated species but, there is no data to compare the aw profiles of these indigenous species found on fish products elsewhere in Nigeria. However, Abellana et al. (2001) described the aw and temperature relations of Aspergillus and Penicillium species found on sponge cake, and all the isolates could grow within 0.90–0.85 aw, with optimal growth recorded at 0.90 aw level and showed that growth responses were temperature dependent. In the study, 0.80–0.75 aw was reported as the limitant range for some of the Aspergillus and the Penicillium isolates.

Apart from aw and aw-modifying solute that are directly related to water availability and carbon source respectively, which are capable of modifying fungal growth (Nesci et al. 2004), other interacting abiotic factor, temperature, exert significant influence on growth windows and ecology of toxin production in fungal species (Magan and Lacy 1984). There are contrasting reports on aw and temperature relations of Aspergillus species, for example, the optimal aw for growth and toxin production by A. flavus and A. parasiticus isolated from maize were 0.95–0.98 aw at 25–30 °C (Faraj et al. 1991). Romero et al. (2007) described water stress-tolerant strains of Aspergillus sp isolated from dried vine fruits, which were able to grow up to 0.85 aw at 25–30 °C. Similarly, Wheeler et al. (1988) reported some Aspergillus species isolated from fish, with optimum aw activity for growth below 0.95 aw and minimum growth near 0.75 aw in media containing NaCl. The results of this study is in agreement with some of those earlier reports in terms of aw activity windows for growth (Astoreca et al. 2007; Beuchat 2017), but the rates of growth were lower than observed in the current study. It is interesting that all the cited earlier studies on temperature and aw relations were conducted at constant temperatures, in contrast to the current study which was conducted at fluctuating ambient temperature, 25 ± 5 °C. Constant temperature does not occur in nature and may be limiting to aspects of growth relations. Measurement of growth rates at ambient temperature better simulates natural conditions and the fungi are likely to have better exploited favourable temperature windows, resulting in the faster growth rates. Water activity relations of these indigenous species have been rarely studied and there is strong evidence of intra-specific and regional variabilities in occurrence and biodiversity of species (Bellı et al., 2004; Su-Lin et al. 2006; Romero et al. 2007), which could imply that the strains being reported are exceptionally xeromorphic, but there is no data to compare from Nigeria.

Conclusion

There was no limitant aw level found in the studied conditions (0.995–0.80 aw x fluctuating ambient temperature, 25 ± 5 °C), as all the isolates were fast growing. The aw of the fish samples from the improved processing line was lower than those from the traditional processing lines, but the aw of all the tested the samples was above the Codex Standard for smoked fish, smoke-flavoured fish and smoke-dried fish, which is 0.75 aw or less (10% moisture or less), as necessary to control bacteria pathogens and spoilage fungi. The constraints to codex standards are diverse; it may include the quality of processing equipment, use of non-standardized traditional processing methods by untrained peasants and ineffective regulation of product standards. Further studies on aw of the fungal species is necessary to determine the baseline aw necessary for preservation against the spoilage fungi. The spoilage fungi recorded in this study included species that are known to be toxigenic, thus establishing potential risks to consumers and the need for improvements in postharvest handling. Smoke-dried fish should be consumed in time and not stored for long period. This study has indicated the need to enforce quality standards in fish postharvest handling of catfish and the derivatives in Nigeria.

Acknowledgements

Facilities used for the experiment were provided by the Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture, Ekiti State University Nigeria. The support of the laboratory to accomplish this study is hereby acknowledged.

Appendix

see Table 4

Table 4.

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) Table of the aw of fish samples collected from open markets

| Dependent Variable: Water activity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source of Variation | Type III Sum of Squares | DF | Mean Square | F | Sig |

| Corrected Model | .025a | 7 | .004 | 1.615 | .167 |

| Source of samples | .009 | 3 | .003 | 1.374 | .268 |

| Processing method | .014 | 1 | .014 | 6.230 | .018 |

| Source x Processing method | .002 | 3 | .001 | .317 | .813 |

| Error | .070 | 32 | .002 | ||

| Total | 27.585 | 40 | |||

| Corrected Total | .095 | 39 | |||

Declarations

Conflict of interests

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abellana M, Sanchis V, Ramos AJ. Effect of water activity and temperature on growth of three Penicillium species and Aspergillus flavus on a sponge cake analogue. Int J Food Microbiol. 2001;71(2–3):151–157. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(01)00596-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abolagba OJ, Igbinevbo EE. Microbial load of fresh and smoked fish marketed in Benin metropolis, Nigeria. Res J Fish Hydrobiol. 2010;5(2):99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Adebayo-Tayo BC, Onilude AA, Patrick UG. Mycofloral of smoke-dried fishes sold in Uyo, Eastern Nigeria. World J Agric Sci. 2008;4(3):346–350. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews S, Pitt JI. Further studies on the water relations of xerophilic fungi, including some halophiles. Microbiology. 1987;133(2):233–238. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-2-233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Astoreca A, Magnoli C, Ramirez ML, Combina M, Dalcero A. Water activity and temperature effects on growth of Aspergillus niger, A. awamori and A. carbonarius isolated from different substrates in Argentina. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;119(3):314–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett HL and Hunter BB (1998) Illustrated Genera of Imperfect Fungi, Fourth Edition. Burges Publications Company.

- Bellı N, Marın S, Sanchis V, Ramos AJ. Influence of water activity and temperature on growth of isolates of Aspergillus section Nigri obtained from grapes. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004;96(1):19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjakul S, Aroonrueng N. Effect of smoke sources on quality and storage stability of catfish fillet (Clarias macrocephatus Gunther) J Food Qual. 1999;22(2):213–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4557.1999.tb00552.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beuchat LR (2017) Influence of water activity on sporulation, germination, outgrowth, and toxin production. In Water Activity pp. 137–151. Routledge.

- Borisade OA, Magan N. Growth and sporulation of entomopathogenic Beauveria bassiana, Metarhizium anisopliae, Isaria farinosa and Isaria fumosorosea strains in relation to water activity and temperature interactions. Biocontrol Sci Tech. 2014;24(9):999–1011. doi: 10.1080/09583157.2014.909007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edema MO, Agbon AO. Significance of fungi associated with smoke-cured Ethmalosa fimbriata and Clarias gariepinus. J Food Process Preserv. 2010;34:355–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4549.2009.00426.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emikpe BO, Adebisi T, Adedeji OB. Bacteria load on the skin and stomach of Clarias gariepinus and Oreochromis niloticus from Ibadan, South West Nigeria: Public health implications. J Microbiol Biotechnol Res. 2011;1(1):52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Farag HE, El-Tabiy AA, Hassan HM. Assessment of ochratoxin A and aflatoxin B1 levels in the smoked fish with special reference to the moisture and sodium chloride content. Res J Microbiol. 2011;6(12):813. doi: 10.3923/jm.2011.813.825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faraj MK, Smith JE, Harran G. Interaction of water activity and temperature on aflatoxin production by Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus in irradiated maize seeds. Food Addit Contam. 1991;8(6):731–736. doi: 10.1080/02652039109374031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foline OF, Rachael AM, Iyabo BE, Fidelis AE. Proximate composition of catfish (Clarias gariepinus) smoked in Nigerian stored products research institute (NSPRI): Developed kiln. Int J Fish Aquac. 2011;3(5):96–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier DT. Bacterial zoonoses of fishes: a review and appraisal of evidence for linkages between fish and human infections. Vet J. 2015;203(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorni P, Battilani P, Pietri A, Magan N. Effect of aw and CO2 level on Aspergillus flavus growth and aflatoxin production in high moisture maize post-harvest. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008;122(1–2):109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gram L. Compendium of the microbiological spoilage of foods and beverages. New York, NY: Springer; 2009. Microbiological spoilage of fish and seafood products; pp. 87–119. [Google Scholar]

- Ikutegbe V, Sikoki F. Microbiological and biochemical spoilage of smoke-dried fishes sold in West African open markets. Food Chem. 2009;161:332–336. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magan N, Lacey J. Effects of gas composition and water activity on growth of field and storage fungi and their interactions. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1984;82(2):305–314. doi: 10.1016/S0007-1536(84)80074-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall DL, Kim CR. Microbiological and sensory analyses of refrigerated catfish fillets treated with acetic and lactic acids. J Food Qual. 1996;19(4):317–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4557.1996.tb00426.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nesci A, Etcheverry M, Magan N. Osmotic and matric potential effects on growth, sugar alcohol and sugar accumulation by Aspergillus section Flavi strains from Argentina. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;96(5):965–972. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omodara MA, Olayemi FF, Oyewole SN, Ade AR, Olaleye OO, Abel GI, Peters O. The drying rates and sensory qualities of african catfish, clarias gariepinus dried in three NSPRI developed fish kilns. Niger J Fish Aquac. 2016;4(1):42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Osibona AO, Kusemiju K, Akande GR. Fatty acid composition and amino acid profile of two freshwater species, African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) and tilapia (Tilapia zillii) Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev. 2009;9(1):608–621. [Google Scholar]

- Parra R, Magan N. Modelling the effect of temperature and water activity on growth of Aspergillus niger strains and applications for food spoilage moulds. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;97(2):429–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt JI, Hocking AD (2009) The ecology of fungal food spoilage. In: Fungi and food spoilage. Springer, Boston, MA. pp (3–9).

- Romero SM, Patriarca A, Pinto VF, Vaamonde G. Effect of water activity and temperature on growth of ochratoxigenic strains of Aspergillus carbonarius isolated from Argentinean dried vine fruits. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;115(2):140–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson RA, Houbraken J, Thrane U, Frisvad JC, Andersen B (2010) Food and indoor fungi. 390 pp. CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre Utrecht, The Netherlands.

- Santos JL, Chaves RD, Sant’Ana AS, Estimation of growth parameters of six different fungal species for selection of strains to be used in challenge tests of bakery products. Food Biosci. 2017;20:62–66. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2017.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su-lin LL, Hocking AD, Scott ES. Effect of temperature and water activity on growth and ochratoxin A production by Australian Aspergillus carbonarius and A. niger isolates on a simulated grape juice medium. Int J Food Microbiol. 2006;110(3):209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suñen E, Fernandez-Galian B, Aristimuno C. Antibacterial activity of smoke wood condensates against Aeromonas hydrophila, Yersinia enterocolitica and Listeria monocytogenes at low temperature. Food Microbiol. 2001;18(4):387–393. doi: 10.1006/fmic.2001.0411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler KA, Hocking AD, Pitt JI. Water relations of some Aspergillus species isolated from dried fish. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1988;91(4):631–637. doi: 10.1016/S0007-1536(88)80038-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Yuan-Ying S, Cai L. An optimized protocol of single spore isolation for fungi. Cryptogam, Mycol. 2013;34(4):349–356. doi: 10.7872/crym.v34.iss4.2013.349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]