Abstract

Single-molecule studies can reveal phenomena that remain hidden in ensemble measurements. Here we show the correlation between lateral protein diffusion and channel activity of the general protein import pore of mitochondria (TOM-CC) in membranes resting on ultrathin hydrogel films. Using electrode-free optical recordings of ion flux, we find that TOM-CC switches reversibly between three states of ion permeability associated with protein diffusion. While freely diffusing TOM-CC molecules are predominantly in a high permeability state, non-mobile molecules are mostly in an intermediate or low permeability state. We explain this behavior by the mechanical binding of the two protruding Tom22 subunits to the hydrogel and a concomitant combinatorial opening and closing of the two β-barrel pores of TOM-CC. TOM-CC could thus represent a β-barrel membrane protein complex to exhibit membrane state-dependent mechanosensitive properties, mediated by its two Tom22 subunits.

Subject terms: Single-molecule biophysics, Ion transport

Wang et al. exploit single-molecule measurements to uncover a potentially new mechanosensitive functionality of mitochondrial TOM core complexes.

Introduction

The TOM complex of the outer membrane of mitochondria is the main entry gate for nuclear-encoded proteins from the cytosol into mitochondria1. It does not act as an independent entity, but in a network of interacting protein complexes, which transiently cluster in mitochondrial outer- and inner-membrane contact sites2,3. For proteins destined for integration into the lipid bilayer of the inner mitochondrial membrane, TOM transiently cooperates with components of the inner-membrane protein translocase TIM22. Proteins en route to the mitochondrial matrix require supercomplex formation with the inner-membrane protein translocase TIM234,5. Depending on the activity of mitochondria, the lateral organization and the possibility of the respective repositioning of TOM, TIM22, and TIM23 in the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes to form transient contact sites may therefore be of fundamental importance for the different import requirements of the organelle2.

Detailed insights into the molecular architecture of the TOM core complex (TOM-CC) from N. crassa6, S. cerevisiae7,8 and human9 mitochondria were obtained by cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM). All three structures show well-conserved symmetrical dimers, where the monomer comprises five membrane protein subunits. Each of the two transmembrane β-barrel domains of the protein-conducting subunit Tom40 interacts with one subunit of Tom5, Tom6, and Tom7, respectively. Two central transmembrane Tom22 receptor proteins, reaching out into the cytosol and the mitochondrial intermembrane space (IMS), connect the two Tom40 pores at the dimer interface.

Most studies that reported on the dynamic properties of the TOM-CC channel have been based on ion current measurements through single TOM-CC channels in planar lipid membranes under application of a membrane potential10–14. However, the physiological significance of the voltage-dependent conformational transitions between the open and closed states of the TOM-CC is controversial because the critical voltage |ΔV| > 50 mV above which TOM-CC channels close14,15, is significantly greater than any metabolically theory-derived potential |MDP| < 5 mV at the outer mitochondrial membrane16.

In this work, we probe and correlate lateral mobility and ion flux though single TOM-CC molecules in lipid membranes resting on ultrathin hydrated agarose films using non-invasive real time electrode-free optical single-channel recording17,18. This approach does not require the use of fluorescent fusion proteins or labeling of TOM-CC by fluorescent dyes or proteins that might interfere with lateral movement and function of TOM-CC in the membrane. In our study, possible changes in ion flux associated with conformational changes of the TOM-CC are only caused by thermal motion of the protein and possible interactions with the hydrogel underlying the membrane. Our setup is therefore a simplified model system where we study a single aspect of complex interactions in the mitochondrial membrane.

We find that freely diffusing TOM-CC molecules stall when interacting with structures adjacent to the membrane, ostensibly due to interaction between the extended polar domains of Tom22 and the supporting agarose film. Concomitantly with suspension of movement, TOM-CC changes reversibly from an active (both pores open) to a weakly active (one pore open) and inactive (both pores closed) state. The strong temporal correlation between lateral mobility and ion permeability suggests that TOM-CC channel gating is highly sensitive to molecular confinement and the mode of lateral diffusion. Taken alongside recent cryo-electron microscopy of this complex, we argue that these dynamics provide a new functionality of the TOM-CC. From a general perspective, for the best of our knowledge, this may be the first demonstration of β-barrel protein mechanoregulation and the causal effect of lateral diffusion. The experimental approach we used can also be readily applied to other systems in which channel activity plays a role in addition to lateral membrane diffusion.

Results

Visualizing the open-closed channel activity of TOM-CC

TOM-CC was isolated from a N. crassa strain that carries a version of subunit Tom22 with a hexahistidine tag at the C-terminus (Fig. 1a)6,10,19, and reconstituted into a well-defined supported lipid membrane20. Droplet interface membranes (DIBs) were created through contact of lipid monolayer-coated aqueous droplets in a lipid/oil phase and a lipid monolayer on top of an agarose hydrogel (Supplementary Fig. S1)17,18. The cis side of the membrane contained Ca2+-ions, while having a Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent dye (Fluo-8) at the trans side. Ca2+-ion flux through individual TOM-CCs was measured by monitoring Fluo-8 emission in close proximity to the membrane using TIRF microscopy in the absence of membrane potential to avoid voltage-dependent TOM-CC gating (Fig. 1b, c). Contrary to the classical single-molecule tracking approach using single fluorescently labeled proteins, an almost instantaneous update of fluorophores close to the TOM-CC nanopores can be observed. This enables the spatiotemporal tracking of individual molecules for an observation time up to several minutes.

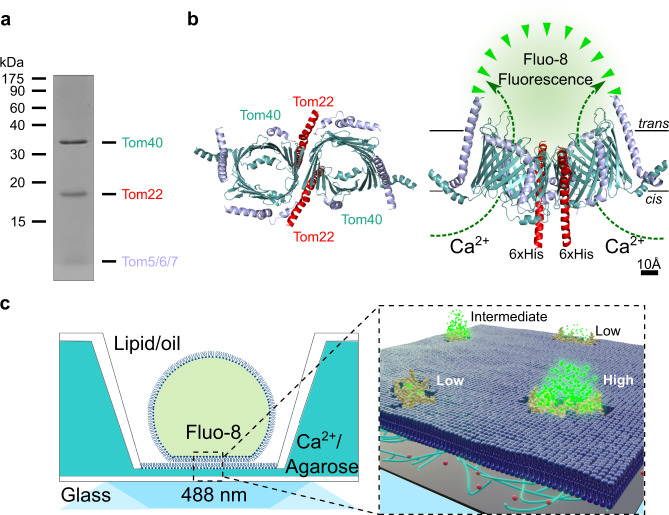

Fig. 1. Scheme for tracking single TOM-CC molecules and imaging their ion channel activity.

a TOM-CC was isolated from mitochondria of a Neurospora strain carrying a Tom22 with a hexahistidinyl tag (6xHis). Analysis of purified protein by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by Coomassie Blue staining revealed all known subunits of the core complex, Tom40, Tom22, Tom7, Tom6 and Tom5. The small subunits Tom7, Tom6 and Tom5 are not separated by SDS-PAGE. b Atomic model based on the cryoEM map of N. crassa TOM core complex (EMDB, EMD-37616). The ionic pathway through the two aqueous β-barrel Tom40 pores is used to optically study the open-closed channel activity of individual TOM-CCs. Left, cytosolic view; right, side view; cis, mitochondria intermembrane space; trans, cytosol. Tom7, Tom6 and Tom5 are not labeled for clarity. c Single-molecule tracking and channel activity sensing of TOM-CC in DIB membranes using electrode-free optical single-channel recording. Left: Membranes are created through contact of lipid monolayer-coated aqueous droplets in a lipid/oil phase and a lipid monolayer on top of an agarose hydrogel. The cis side of the membrane contained Ca2+-ions (0.66 M), while having at the trans side a Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent dye (Fluo-8) and KCl (1.32 M) to balance the membrane osmotic pressure. The high Ca2+ content is necessary to induce high calcium flux through the TOM-CC pores and to provide reliable optical signals. Right: Ca2+-ion flux through individual TOM-CCs from cis to trans is driven by a Ca2+ concentration gradient, established around the two Tom40 pores, and measured by monitoring Fluo-8 emission in close proximity to the membrane using TIRF microscopy. Fluorescence signals reveal the local position of individual TOM-CCs, which is used to determine their mode of lateral diffusion in the membrane. The level of the fluorescence (high, intermediate and low intensity) correlates with corresponding permeability states of a TOM-CC molecule. A 100× TIRF objective is used both for illumination and imaging. Green dots, fluorescent Fluo-8; red dots, Ca2+ ions.

Upon TIRF illumination of membranes with 488 nm laser light, single TOM-CC molecules appeared as high-contrast fluorescent spots on a dark background (Fig. 2a). High (SH), intermediate (SI), and low (SL) intensity levels were indicating Ca2+-flux through the TOM-CC in three distinct permeability states. No high-contrast fluorescent spots were observed in membranes without TOM-CC. The fact that the TOM-CC is a dimer with two identical β-barrel pores6–9 suggests that the high and intermediate intensity levels correspond to two conformational states (SH and SI) with two pores and one pore open, respectively. The low intensity level may represent a conformation (SL) where both pores are closed with residual permeation for calcium.

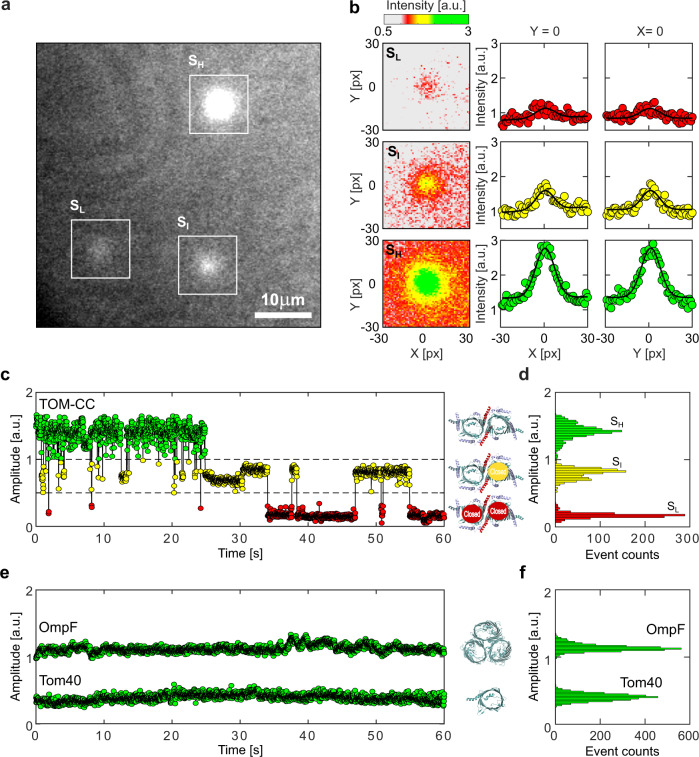

Fig. 2. Visualizing the two-pore channel activity of TOM-CC.

a Typical image (N > 5.3 × 105) of a non-modified agarose-supported DIB membrane with TOM-CC channels under 488 nm TIRF-illumination. The white squares mark spots of high (SH), intermediate (SI), and low (SL) intensity (Supplementary Movie S1). The TIRF image has not been corrected by fluorescence bleaching or by a filter algorithm. b Fitting the fluorescence intensity profile of the three spots marked in (a) to two-dimensional Gaussian functions (Supplementary Movie S2). Red, yellow and green intensity profiles represent TOM-CC in SL, SI, and SH demonstrating Tom40 channels, which are fully closed, one and two channels open, respectively. Pixel size, 0.16 μm. c Fluorescence amplitude trace and (d) amplitude histogram of the two-pore β-barrel protein channel TOM-CC. The TOM-CC channel switches between SH, SI, and SL permeability states over time. Inserts, schematic of N. crassa TOM core complex with two pores open in SH (top), one pore open in SI (middle), and two pores closed in SL (bottom) (EMDB, EMD-37616); e Representative single-channel optical recordings and (f) amplitude histograms of the TOM-CC subunit Tom40 and OmpF. Tom40 and OmpF are completely embedded in the lipid bilayer. In contrast to the two-pore β-barrel protein complex TOM-CC, Tom40, and OmpF exhibit one permeability state over time only. Insert, structural model of N. crassa Tom40 (EMDB, EMD-3761) and E. coli OmpF (PDB, 1OPF) with open β-barrel pores. Data were acquired as described in Fig. 1c at a frame rate of 47.5 s−1. a.u. arbitrary unit.

Supplementary Movie S1 shows an optical recording of the open-closed channel activity of several TOM-CCs over time. Individual image frames of membranes were recorded at high frequency at a frame rate of 47.5 s−1 and corrected for fluorescence bleaching. The position and amplitude of individual spots were determined by fitting their intensity profiles to a two-dimensional symmetric Gaussian function with planar tilt to account for possible local illumination gradients in the bleaching corrected background (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. S2). The time evolution of amplitude signals (Fig. 2c, d, Supplementary Movie S2 and Fig. S3) shows that the TOM-CC does not occupy only one of the permeability states SH, SI and SL, but can switch between these three permeability states over time.

To rule out the possibility that the observed intensity fluctuations are caused by possible thermodynamical membrane undulations in the evanescent TIRF illumination field or by local variations in Ca2+ flux from cis to trans, we compared the ion flux through TOM-CC with that through isolated individual Tom40 molecules21 and an unrelated multimeric β-barrel protein22 which has three pores and is almost entirely embedded in the lipid bilayer. In a series of control experiments, we reconstituted Tom40 (Fig. 2e, f and Supplementary Fig. S4) and E. coli OmpF (Fig. 2e, f and Supplementary Figs. S5–S7) into DIB membranes and observed virtually constant fluorescence intensities, respectively. In contrast to TOM-CC, neither protein channel exhibits gating transitions between specific permeability states. The toggling of the TOM-CC between the three different permeability states SH, SI and SL (Fig. 2c) therefore must have another root cause.

The permeability states of TOM-CC are coupled to lateral mobility

Lateral mobility, e.g., free, restricted or directed diffusion, is an important factor for the organization and function of biological membranes and its components23–28. In some cases, the transient anchoring of mobile membrane proteins thereby precedes protein-induced signaling events, as shown for CFTR29 and presynaptic calcium channels30. It is also well accepted that there is a direct correlation between activity and rotational membrane diffusion for cytochrome oxidase31 and sarcoplasmic reticulum ATPase32,33. Since rotational diffusion is obligatorily coupled to lateral diffusion (both require a fluid crystalline membrane), we asked whether, and if so, how the mode of diffusion affects the channel activity of TOM-CC and its permeability states SH, SI, and SL. To this end, we simultaneously tracked the open-closed activity and position of individual TOM-CC molecules in the membrane over time (Fig. 3a).

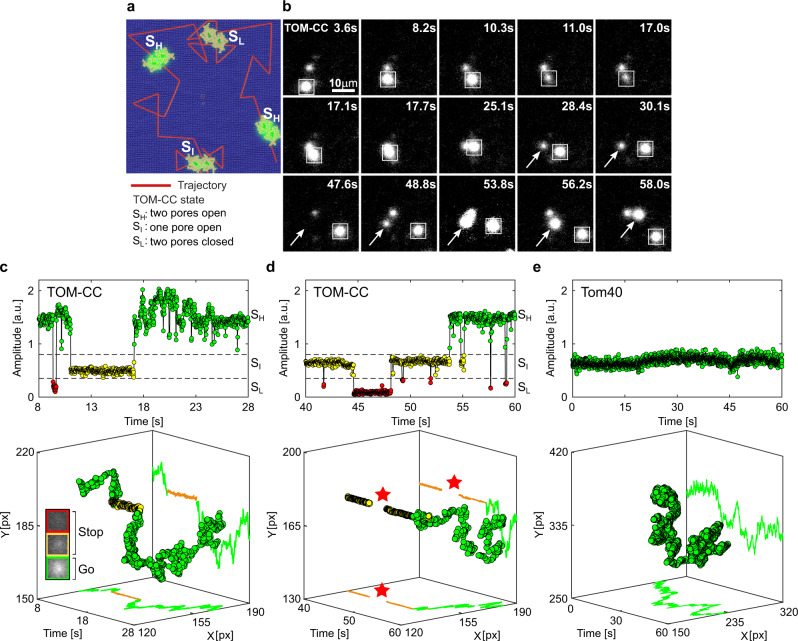

Fig. 3. Lateral mobility correlates with the channel activity of TOM-CC.

a Scheme for imaging both position and channel activity of single TOM-CCs. b Representative TIRF microscopy images of a non-modified agarose-supported DIB membrane with three TOM-CC molecules taken from a time series of 60 s. The square-marked spot displays lateral motion, interrupted by a transient arrest between t = 11.0 s and t = 17.0 s. The arrow-marked spot corresponds to a non-moving TOM-CC until t = 48.8 s. Afterwards, it starts moving. Both moving spots show high fluorescence intensity (SH); the non-moving spots display intermediate (SI) or dark (SL) fluorescence intensity (Supplementary Movie S3). c, d Fluorescent amplitude trace and corresponding trajectory of the square- and arrow-marked TOM-CC as shown in (b) highlighted for two different time windows. Plots on top shows the change of amplitude over time, and plots on the bottom show the respective spatiotemporal dynamics for the three states. Comparison of the trajectories of single TOM-CC molecules with their corresponding amplitude traces reveals a direct correlation between stop-and-go movement and open-closed channel activity. Lateral diffusion of TOM-CCs in the DIB membrane is interrupted by temporary arrest, presumably due to transient linkage to the underlying agarose hydrogel. Although weak intensity profiles in SI do not allow accurate position determination, the fluorescent spots disappear and reappear at the same spatial x, y coordinates (red stars). The higher amplitude (c top) between t = 17.1 s and t = 25.1 s is due to the overlap between two adjacent spots. Green, TOM-CC is freely diffusive in SH; yellow and red, immobile TOM-CC in SI and SL. e Fluorescent amplitude trace and corresponding trajectory of a single β-barrel subunit Tom40. The Tom40 channel exhibits only one permeability state and is subject to simple thermal movement in the membrane (Supplementary Movie S5). Tom40 does not show stop-and-go motion as with TOM-CC. All data were acquired as described in Fig. 1c at a frame rate of 47.5 s−1. A total of nTOM = 64 and nTom40 = 20 amplitude traces and trajectories were analyzed. a.u., arbitrary unit.

Supplementary Movie S3 and Fig. 3b show that the open-closed channel activity of single TOM-CCs is coupled to lateral movement in the membrane. This is supported by comparison of the trajectories of single TOM-CC molecules with their corresponding fluorescence amplitude traces (Fig. 3c, d). The position of fluorescent spots does not change when TOM-CC is in intermediate SI or low SL permeability state. Although weak intensity profiles do not allow accurate determination of the position of TOM-CC in the membrane plane, Supplementary Movie S3 and Fig. 3d clearly show that TOM-CC does not move in SL; disappearance and reappearance of the fluorescent spot, switching from SI to SL and back to SI, occurs at virtually the same spatial x, y coordinates. In contrast, the trajectories of TOM-CC in SH state demonstrate free diffusion. Additional samples of trajectories and amplitude traces are shown in Supplementary Fig. S3.

Similar stop-and-go movement patterns were observed in an independent set of experiments for TOM-CC covalently labeled with fluorescent dye Cy3 (Supplementary Movie S4 and Fig. S8). It is particularly striking that freely moving TOM-CC molecules stop at the same spatial x, y-position when they cross the same position a second time, indicating a specific molecular trap or anchor point (agarose polysaccharide strands) at this stop-position below the membrane. In contrast, single Tom40 molecules isolated from TOM-CC (Supplementary Movie S5, Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. S4) and OmpF molecules purified from E. coli. outer membranes (Supplementary Movie S6 and Supplementary Fig. S5) show the most elementary mode of mobility expected for homogeneous membranes: simple Brownian translational diffusion. Consistent with the fact that OmpF is fully embedded in membranes22, only very few out of a total of 171 analyzed OmpF molecules were temporarily (~15%) or permanently (~12%) trapped in the membrane (Supplementary Figs. S7, S6). In contrast to TOM-CC, however, a “stop” of OmpF did not seem to be accompanied by a change in intensity (Supplementary Figs. S6, S7) and thus by closing the pores.

In good agreement with these results, the diffusion coefficients of the TOM-CC, evaluated from the activity profiles and trajectories (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S3), were determined from time-averaged mean squared displacements as D(SI) = D(SL) ≤ Dmin = 0.01 μm2 s−1 and D(SH) ≃ 0.85 ± 0.16 (mean ± SEM, n = 46) in states SI and SH, respectively. TOM-CC molecules, that revealed diffusion constants less or equal than Dmin, were defined as immobilized. The diffusion coefficient D(SH) corresponds to the typical values of mobile Tom40 (DTom40 ~ 0.5 μm2 s−1) and mobile Tom7 (DTom7 ~ 0.7 μm2 s−1) in native mitochondrial membranes34,35 and is comparable to that of transmembrane proteins in plasma membranes lined by cytoskeletal networks28. The diffusion coefficient of TOM-CC in SL state could not always be reliably determined due to its extremely low intensity levels.

TOM-CC labeled with Cy3 yielded diffusion constants of DCy3 ≃ 0.36 ± 0.08 μm2 s−1 (mean ± SEM, n = 15) and DCy3 ≤ Dmin = 0.01 μm2 s−1 for moving and transiently trapped particles, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S8). In agreement with typical values for monomeric and multimeric proteins in homogenous lipid membranes36,37, the lateral diffusion coefficients of the control proteins Tom40 and OmpF yielded translational diffusion coefficients of DTom40 ≃ 1.49 ± 0.21 μm2 s−1 (mean ± SEM, n = 20) and DOmpF ≃ 1.16 ± 0.07 μm2 s−1 (mean ± SEM, n = 42), respectively (Supplementary Figs. S4, S5).

Based on these results, we concluded that the arrest of TOM-CC in the lipid bilayer membrane, caused by short-lived interaction with the polysaccharide strands of the supporting hydrogel (Supplementary Fig. S1), triggers a transient closure of its two β-barrel pores.

Controlled immobilization of the TOM-CC results in channel closures

Since the two Tom22 subunits in the middle of the TOM-CC (Fig. 1b) clearly protrude from the membrane plane at their intramembrane space (IMS) side6–9, we considered whether Tom22 acts as “light-switch” that determines the lateral mobility of the TOM-CC and thereby causing transitions between open (SH) and the closed (SI and SL) conformations of the two TOM-CC pores.

To address this question, we employed a Ni-NTA-modified agarose to permanently restrict lateral movement of the protein by fixing single TOM-CC molecules to the hydrogel via the C-terminus of His-tagged Tom22 (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Movie S7).

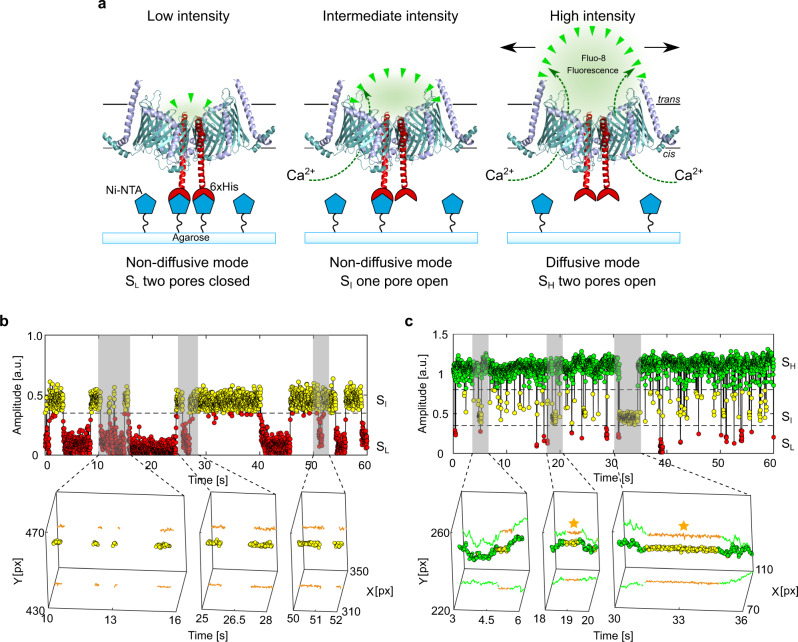

Fig. 4. Controlled immobilization of TOM-CC triggers channel closures.

a Schematic representation of individual TOM-CC channels in DIB membranes supported by Ni-NTA-modified agarose. TOM-CC molecules can be permanently linked to the underlying hydrogel via His-tagged Tom22. Tethered and non-tethered TOM-CC molecules in closed (SI and SL) and open (SH) states are indicated, respectively. b Fluorescent amplitude trace (top) of a TOM-CC channel permanently tethered to Ni-NTA-modified agarose. The trajectory segments (bottom) correspond to the time periods of the amplitude traces marked in gray (Supplementary Movie S7: bottom). Non-diffusive, permanently immobilized TOM-CC is only found in SI or SL, indicating that tight binding of the His-tagged Tom22 domain (Fig. 1b) to Ni-NTA-modified agarose triggers closure of the β-barrel TOM-CC pores. c Fluorescence amplitude trace (top) of a TOM-CC channel transiently and non-specifically entangled by Ni-NTA-modified agarose. The trajectory segments (bottom) correspond to the time periods of the amplitude traces marked in gray. The movement of TOM-CC is interrupted twice at the same spatial x,y membrane position from t1 = 18.56 s to t2 = 19.19 s and from t3 = 31.14 s to t4 = 34.55 s (yellow stars). Consistent with the data shown in Fig. 3, moving TOM-CC molecules in diffusive mode are found in the fully open SH state; transient tethering causes the TOM-CC β-barrels to close. Data were acquired as described in Fig. 1c at a frame rate of 47.5 s−1. A total of nTOM = 123 amplitude traces and trajectories were analyzed. a.u. arbitrary unit.

As expected, permanently immobilized TOM-CC ( and D(SL) ≤ Dmin = 0.01 μm2 s−1, n = 83) was most often found in states SI or SL, indicating one or two pores closed, respectively (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Movie S7 and Fig. S9a–d). Only a minority of TOM-CC molecules that were not immobilized by the binding of Tom22 to Ni-NTA moved randomly in the membrane plane ( ≃ 0.34 ± 0.06 μm2 s−1, mean ± SEM, n = 40). The movement of this latter population of molecules was occasionally interrupted by periods of transient anchorage ( and ≤ Dmin), as observed for molecules in membranes supported by unmodified agarose. Again, moving TOM-CC molecules were found in the fully open SH state; non-moving complexes in the SI or the SL states (Fig. 4c; Supplementary Fig. S9e–h). For comparison, purified Tom40 itself showed only one ion permeation state and no stop-and-go dynamics (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Movie S5 and Supplementary Fig. S4). Consistently, in the presence of imidazole, which prevents binding of hexahistidine-tagged Tom22 to Ni-NTA-modified agarose (Supplementary Movie S8), also virtually no permanently immobilized TOM-CC molecules were observed ( ≃ 1.35 ± 0.14 μm2 s−1, mean ± SEM, n = 30).

Correlation between lateral motion and TOM-CC channel activity

DIB membranes supported by both hydrogels, non-modified and Ni-NTA-modified agarose (Supplementary Movie S7), showed a significant number of single TOM-CC molecules that were either non-diffusive or diffusive at SI and SH. Thus, TOM-CC molecules were numerically sorted into diffusive and non-diffusive tethered groups to emphasis the correlation between the mode of lateral diffusion and channel activity of 187 observed TOM-CC molecules. We then asked whether the molecules were in the fully opened SH or half-open SI state. Since weak intensity profiles did not allow accurate determination of the position of TOM-CC and thus the lateral diffusion coefficient D(SL), we conducted the classification analysis using only the parameters and .

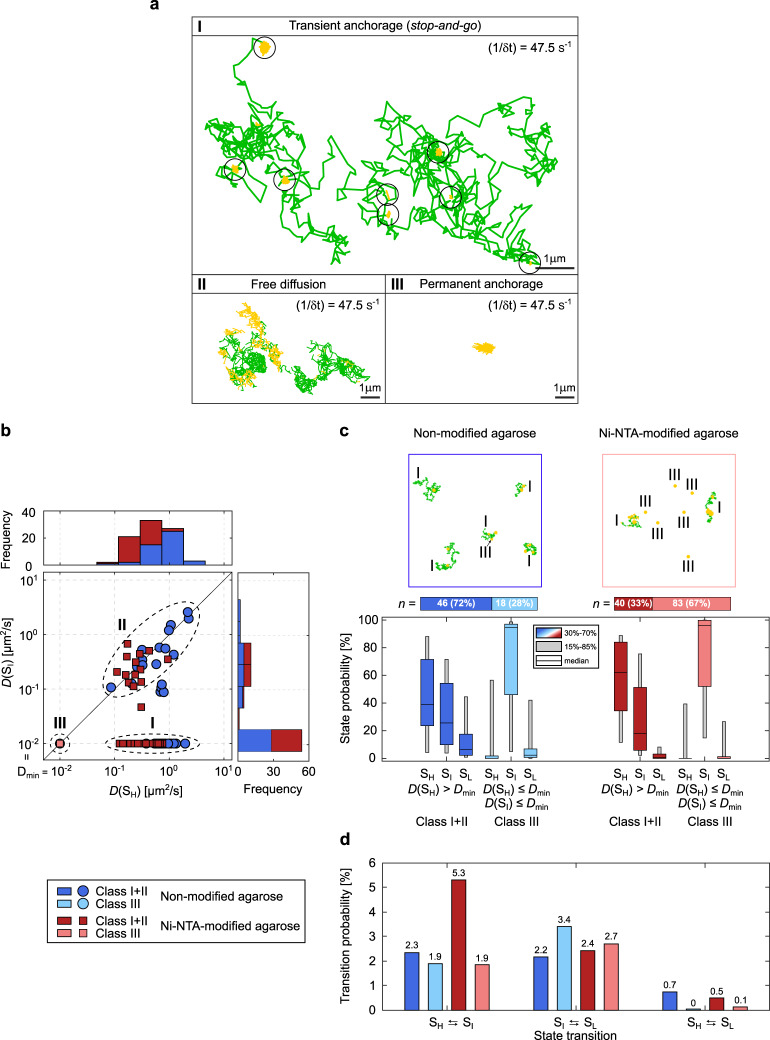

As shown in Fig. 5a, b, we can define three different classes of lateral motion and channel activity. The first and major class I shows lateral mobility at SH only, while being tethered at SI. Here, spatiotemporal stop-and-go dynamics of the TOM-CC correlate with channel activity. The second class II shows similar diffusivities at both states, SH and SI (Supplementary Fig. S10). The TOM molecules in this class are unlikely to have a functional Tom2221,38 or are incorporated into the membrane in a reverse orientation and therefore do not interact with the hydrogel. Another possible but unlikely explanation is a spatial void of agarose network preventing mechanoregulated interaction of Tom22 with the network within the observation time window. The third class III represents events exhibiting permanently tethered TOM-CC molecules, which do not move in the membrane and are exclusively non-diffusive (Supplementary Fig. S9a, b). Most molecules in this class are in SI and SL. Those TOM-CC molecules, which briefly change from SI to SH and back to SI (Supplementary Fig. S9c, d), could diffuse in SH but are immediately recaptured and trapped by the hydrogel below the membrane, resulting in .

Fig. 5. Statistical correlation between channel activity and lateral mobility of TOM-CC.

a Trajectories for various modes of TOM-CC mobility. Class I, diffusion interrupted by periods of transient anchorage (sites of transient anchorage circled); Class II, free diffusion; Class III, permanent anchorage. Moving particles in SH are shown in the trajectories in green; transiently or permanently tethered molecules in SI are shown in yellow. Data were acquired for t = 60 s at a frame rate of 47.5 s−1. b D(SI) as a function of D(SH) individually plotted for all TOM-CC molecules in DIB membranes supported by non-modified (dark blue and light blue, n = 64) and Ni-NTA modified agarose (dark red and light red, n = 123). Frequency histograms of D(SI), and are shown on top and right side, respectively. Three classes can be defined: a main class (I) of moving particles in SH while being transiently tethered at SI , a second class (II) of freely moving particles in SH and SI and a third class (III) of permanently tethered molecules in SI and SL . c Example trajectories (top and Supplementary Movie S7) and state probabilities (bottom) of non-permanently and permanently tethered TOM-CC in DIBs supported by non-modified and Ni-NTA-modified agarose. The probability of being in state SH is higher for non-permanently (classes I and II, dark blue [n = 46] and dark red [n = 40]) than for permanently tethered molecules (class III, light blue [n = 18] and light red [n = 83]). The probability of being in state SI is significantly higher for permanently (class III) than for non-permanently tethered particles (classes I and II). This suggests that binding of Tom22 to Ni-NTA agarose below the membrane triggers closure of the TOM-CC channels. The data are represented as median; the confidence intervals are given between 15 to 85% and 30 to 70%. d Absolute state transition probabilities classified by bidirectional state transitions as SH ⇆ SI, SI ⇆ SL, and SH ⇆ SL. Diffusive TOM-CC molecules have a significantly higher transition probability for switching between SH and SI in DIBs supported by Ni-NTA-modified agarose (~5.3%) than in non-modified agarose membranes (~2.3%). This is consistent with the higher efficacy of TOM-CC-trapping by Ni-NTA-modified agarose compared to non-modified agarose. Classification of non-permanently and permanently tethered TOM-CC is shown at the left bottom.

Figure 5c shows state probabilities of TOM-CC in membranes supported by the two different hydrogels, non-modified and Ni-NTA-modified agarose. Diffusive molecules (D > Dmin) in membranes supported both by non-modified and Ni-NTA-modified agarose show similar probabilities to be at one of the three permeability states (SH, SI, and SL). Diffusive TOM-CC molecules are significantly more often at SH than at SI and SL. The permanently tethered fraction of TOM-CC (67%) in Ni-NTA-modified agarose is ~2.4 times larger compared to the fraction (28%) in non-modified agarose, consistent with the stronger interaction of Tom22 with the hydrogel, thereby permanently constraining lateral motion. In line with this, permanently tethered molecules (D ≤ Dmin) in both hydrogel-supported membranes stay at SI during the majority of time, and show only transient SH and SL occupancy. The data suggest that the C-terminal (IMS) domain of Tom22 plays a previously unrecognized role in mechanoregulation of TOM-CC channel activity by binding to immobile structures near the membrane.

Although diffusive TOM-CC molecules (D > Dmin) are observed more often at SH in Ni-NTA-modified agarose than in non-modified agarose-supported membranes (Fig. 5c), they show a lower stability at SH having a significantly higher transition probability for switching between SH and SI (Fig. 5d, (SH ⇆ SI) ≃ 5.3% versus (SH ⇆ SI) ≃ 2.3%). This is in line with the higher efficacy of TOM-CC-trapping by Ni-NTA-modified agarose compared to non-modified agarose. In contrast to unmodified hydrogel, Ni-NTA-modified agarose hydrogel can capture freely mobile TOM-CC via the (IMS) domain of Tom22 in two ways: on the one hand, by specific interaction and permanent anchoring with Ni-NTA, and, on the other hand, by collision and transient nonspecific anchoring. While a direct transition between SH and SL barely occurs in both systems, transitions between SI and SL are similarly often. This indicates that the two Tom40 β-barrel pores independently open and close within the time resolution (~20 ms) of our experiment.

Discussion

In this study, we have shown that TOM-CC molecules can interact with their environment and switch reversibly between three states of transmembrane channel activity. Only when both channels are open (high permeable state) the TOM-CC molecules move freely in the membrane, while transient physical interaction with the hydrated agarose film supporting the membrane leads to temporary immobilization and closure of at least one pore. The use of agarose films with covalently bound Ni-NTA promotes TOM-CC immobilization. Duration of channel closure is thereby significantly prolonged. This indicates that TOM-CC does not only respond to biochemical39, but also to mechanical stimuli: the anchoring of freely moving TOM-CC to structures near the membrane leads to a partial or complete closure of the two-pore TOM-CC channel.

We obtained data from n = 187 single molecules and over half a million image frames (Fig. 5b, NTOM-CC = 532,576). This sampling number allows us to assign molecular events with statistical confidence using non-parametric statistics, but even visual perusal of the data is sufficient to allow a first assessment of data reliability. Our data is consistent with the dimeric pore structure of the TOM-CC where the three molecular states correspond to one or two pores open and all pores closed, respectively. At least in our model system recent proposals of a trimeric functional pore structure40 are not consistent with our data. Functional reversible disassembly and reassembly of the TOM-CC at time scales studied here are highly improbable.

Previous electrophysiology studies41 have shown that the TOM channel of yeast mitochondria is mainly in a closed state, while TOM lacking Tom22 has been found mainly in an open state, similar to that of yeast and N. crassa Tom4011,21,41. It has therefore been postulated that Tom22 negatively regulates the opening probability of TOM41. However, the molecular mechanism of how Tom22 influences the activity of the open-closed channels of the TOM machinery has remained an open question.

Examination of the cryoEM structures of TOM-CC reveals that its two Tom22 subunits extend significantly into the IMS space (more than 22 Å6–9, Fig. 1b), thereby preventing a direct interaction of the two Tom40 β-barrels with the agarose matrix. It is therefore likely that the two Tom22 subunits localized in the center of the complex are primarily responsible for the matrix-dependent channel activity. This is supported by our observation that binding of one hexahistidine-tagged Tom22 to the Ni-NTA matrix leads to a permanent immobilization of the TOM-CC in the membrane, with one of the two Tom40 pores open. Restricting the movement of the second inter-membrane space domain of Tom22 could then lead to the closure of the second Tom40 pore. Consistent with this, the isolated Tom40 pore itself showed essentially no correlated stop-and-go and open-closed dynamics.

In conclusion, we have clear evidence—structural and dynamic—that the two Tom22 subunits of TOM-CC can force the Tom40 dimer to undergo a conformational change that leads to channel closure. This process is reversible and triggered solely by natural thermal fluctuations of the TOM-CC in the membrane. We realize that the agarose matrix underlying the membrane is not a perfect substitute for the intermembrane space of mitochondria. Nevertheless, the reconstituted system allows the complex effects of mitochondrial compartmentalization to be eliminated as shown for plasma membrane proteins localized in polymer supported lipid bilayers20,42.

Our results raise a fundamental question: are the two Tom40 channels open continually, as static cryoEM structures seem to indicate6–9, or can the protein channels be actively influenced by interaction with exogenous interacting proteins near the membrane that restrict the movement of the TOM-CC? In the future, the development of improved in vitro assays may help to observe intrinsic TOM-CC dynamics and could reveal even more processes and dynamics of possible physiological relevance. With regard to the mechanism of TOM-mediated protein translocation into mitochondria, our data open the exciting possibility that proteins at the periphery of the outer membrane, e.g., components of inner-membrane TIM23 complex, not only limit lateral membrane diffusion of the TOM-CC by transient interaction and formation of an active supercomplex at mitochondrial contact sites43, but might also regulate the open-close status of the channel as a consequence. This could in turn translate into conformational changes of the TOM-CC that influence the translocation process of incoming mitochondrial preproteins. In this context, it might be interesting to visualize different Tom22-dependent conformations of TOM-CC using cryoEM and to perform single-molecule FRET experiments to study the dynamics of TOM-CC between different conformations in the near future.

Recently, the now extensive structural and physical data common to mechanosensitive membrane proteins have been reviewed44,45. The structural data now allows mechanosensitive proteins and protein complexes (all of which were comprised of transmembrane α-helices) to be separated into five different classes, each subject to characteristic underlying molecular mechanisms. They also show that for the membrane channels considered, fundamental physical properties of the membrane can influence channel activity. This ancient mechanism to regulate open-closed channel activity has also been observed in MSL1, a mitochondrial ion channel that dissipates the mitochondrial membrane potential to maintain redox homeostasis during abiotic stress46–49.

In this study, we provide in vitro evidence for the first example of a membrane β-barrel protein complex that exhibits membrane state-dependent mechanosensitive-like properties. Our findings are consistent with the “tether model”45, where an intermembrane protein anchor domain (here Tom22) limits lateral diffusion, as observed for a large number of α-helical membrane proteins44,45,50–53. Since the TOM-CC complex bends the outer mitochondrial membrane locally towards the intermembrane space with an average radius of about 140 Å54, the anchor domains of the two Tom22 subunits should easily be able to dock with other proteins in the mitochondrial intermembrane space and the mitochondrial inner membrane. It will be interesting to study as to whether the mechanostimulated conformational change of the TOM-CC observed in vitro can be confirmed in intact mitochondria.

Methods

Growth of Neurospora crassa and preparation of mitochondria

Neurospora crassa (strain GR-107) that contains a hexahistidinyl-tagged form of Tom22 was grown and mitochondria were isolated as described6. Briefly, ~1.5 kg (wet weight) of hyphae were homogenized in 250 mM sucrose, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris pH 8.5, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) in a Waring blender at 4 °C. ~1.5 kg of quartz sand was added and the cell walls were disrupted by passing the suspension through a corundum stone mill. Cellular residues were pelleted and discarded in two centrifugation steps (4000 × g) for 5 min at 4 °C. The mitochondria were sedimented in 250 mM sucrose, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris pH 8.5, 1 mM PMSF at 17,000 × g for 80 min. This step was repeated to improve the purity. The isolated mitochondria were suspended in 250 mM sucrose, 20 mM Tris pH 8.5, 1 mM PMSF at a final protein concentration of 50 mg/ml, shock-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −20 °C.

Isolation of TOM core complex

TOM-CC, containing subunits Tom40, Tom22, Tom7, Tom6, and Tom5, were purified from Neurospora crassa strain GR-107 as described6,10,19. N. crassa mitochondria were solubilized at a protein concentration of 10 mg/ml in 1% (w/v) n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (Glycon Biochemicals, Germany), 20% (v/v) glycerol, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), and 1 mM PMSF. After centrifugation at 130,000 × g, the clarified extract was loaded onto a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid column (Cytiva, Germany). The column was rinsed with the same buffer containing 0.1% (w/v) n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside and TOM core complex was eluted with buffer containing 0.1% (w/v) n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside, 10% (w/v) glycerol, 20 mM Tris (pH 8.5), 1 mM PMSF, and 300 mM imidazole. For further purification, TOM core complex containing fractions were pooled and loaded onto a Resource Q anion exchange column (Cytiva) equilibrated with 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.2), 2% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 0.1% (w/v) n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside. TOM core complex was eluted with 0–500 mM KCl. A few preparations contained additional phosphate (~0.19 mM). The purity of protein samples (0.4–1.2 mg/ml) was assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue.

Fluorescence labeling of TOM core complex

TOM-CC was covalently labeled with the fluorescent dye Cy3 according to Joo and Ha55. Briefly, about 1 mg/ml of purified TOM-CC was reacted with Cy3-maleimide (AAT Bioquest, USA) at a molar ratio complex to dye of 1:5 in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 2% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide, 350 mM KCl and 0.1% (w/v) n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside at 25 °C for 2 h in the dark. Labeled protein was separated from unconjugated dye by affinity chromatography using Ni-NTA resin, subjected to SDS-PAGE and visualized by 555 nm light and Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining.

Isolation of Tom40

For the isolation of Tom40, isolated mitochondria of N. crassa strain GR-107 were solubilized at a protein concentration of 10 mg/ml in 1% (w/v) n-dodecyl β-D-maltoside (Glycon Biochemicals, Germany), 20% (v/v) glycerol, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 20 mM Tris (pH 8.5), and 1 mM PMSF for 30 min at 4 °C21. After centrifugation at 130,000 × g, the clarified extract was filtered and loaded onto a Ni-NTA column (Cytiva, Germany). The column was rinsed with 0.1% DDM, 10% glycerol, 300 mM NaCl, and 20 mM Tris (pH 8.5) and Tom40 was directly eluted with 3% (w/v) n-octyl β-D-glucopyranoside (OG; Glycon Biochemicals, Germany), 2% (v/v) DMSO, and 20 mM Tris (pH 8.5). The purity of the isolated protein (∼0.3 mg/ml) was assessed by SDS-PAGE.

Isolation of OmpF

Native OmpF protein was purified from Escherichia coli strain BE BL21(DE3)omp6, lacking both LamB and OmpC as described56. Cells from 1 L culture were suspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 buffer containing 2 mM MgCl2 and DNAse and broken by passing through a French press. Unbroken cells were removed by a low-speed centrifugation, then, the supernatant was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and mixed with an equal volume of SDS buffer containing 4% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5. After 30 min incubation at a temperature of 50 °C, the solution was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The pellet was suspended in 2% (w/v) SDS, 0.5 M NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, incubated at a temperature of 37 °C for 30 min and centrifuged again at 100,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant containing OmpF was dialyzed overnight against 20 mM Tris, pH 8, 1 mM EDTA and 1% (w/v) n-octyl polyoxyethylene (Octyl-POE, Bachem, Switzerland). The purity of the protein was assessed by SDS-PAGE.

Formation of droplet interface bilayers

Droplet interface bilayer (DIB) membranes were prepared as previously described17,18 with minor modifications. Glass coverslips were washed in an ultrasonic bath with acetone. Then the coverslips were rinsed several times with deionized water and dried under a stream of nitrogen. Subsequently, the glass coverslips were subjected to plasma cleaning for 5 min. 140 μl of molten 0.75% (w/v) low melting non-modified agarose (Tm < 65 °C, Sigma-Aldrich) or alternatively low melting Ni-NTA-modified agarose (Cube Biotech, Germany) was spin-coated at 5,000 rpm for 30 s onto the plasma-cleaned side of a glass coverslip. After assembly of the coverslip in a custom-built DIB device, the hydrogel film was hydrated with 2.5% (w/v) low melting agarose, 0.66 M CaCl2 and 8.8 mM HEPES (pH 7.2) or with 2.5% (w/v) low melting agarose, 0.66 M CaCl2, 300 mM imidazole and 8.8 mM HEPES (pH 7.2) and covered with a lipid/oil solution containing 9.5 mg/ml 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPhPC, Avanti Polar Lipids, USA) and 1:1 (v/v) mixture oil of hexadecane (Sigma-Aldrich) and silicon oil (Sigma-Aldrich). Aqueous droplets (~200 nl) containing 7 μM Fluo-8 sodium salt with a maximum excitation wavelength of 495 nm (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), 400 μM EDTA, 8.8 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 1.32 M KCl, ~2.7 nM TOM core complex or ~2 nM OmpF were pipetted into the same lipid/oil solution in a separate tray using a Nanoliter 2000 injector (World Precision Instruments). After 2 h of equilibration at room temperature, the droplets were transferred into the custom-built DIB device to form stable lipid bilayers between the droplet and the agarose hydrogel.

AFM imaging

AFM images of agarose-coated coverslips were acquired in liquid solution using a Nanoscope 5 Multimode-8 AFM system with SNL-10 cantilevers (Bruker) in tapping mode.

TIRF microscopy and optical recording

An inverted total internal reflection fluorescence microscope (Ti-E Nikon) was used to image DIB membranes under TIRF illumination using a 488 nm laser (Visitron). Fluorescent emission of Fluo-8, transmitted through a Quad-Band TIRF-Filter (446/523/600/677 HC, AHF), was collected through a 100 × oil objective lens (Apochromat N.A. 1.49, Nikon) and recorded by a back-illuminated electron-multiplying CCD camera (iXon Ultra 897, 512 × 512 pixels, Andor) for 1 min at a frame rate of 47.51 s−1. The pixel size was 0.16 µm.

Tracking of fluorescence spots

For reliable tracking and analysis of the spatiotemporal dynamics of individual fluorescence TOM-CC, Tom40 and OmpF channel activities a customized fully automated analysis routine was implemented in Matlab (The Mathworks, USA). The effect of bleaching was corrected by applying a standard fluorescence bleaching correction procedure57. A double exponential decay obtained by least-square fitting of the image series (average frame intensity ) was obtained as

| 1 |

where t is the frame index (time) and ak are the fitting parameters. The time series was corrected according to

| 2 |

where is the intensity as a function of time t. No filter algorithm was applied. The initial spatial position of a fluorescence spot was manually selected and within a defined region of interested (ROI, 30 × 30 pixels) fitted to a two-dimensional symmetric Gaussian function with planar tilt that accounts for possible local illumination gradients, that the global bleach correction cannot account of, as follows

| 3 |

where x = (x, y) is the ROI with the fluorescence intensity information, A and σ are the amplitude and width of the Gaussian, pk are parameters that characterize the background intensity of the ROI, and μ = (x0, y0) defines the position of the Gaussian. The latter was used to update the position of ROI for the next image. Spots that temporal fuse their fluorescence signal with closely located spots were not considered due to the risk of confusing those spots.

Data analysis

The extracted amplitudes were separated by two individually selected amplitude-thresholds that dived the three states of activity (SH, SI, and SL). The lateral diffusion constants and were obtained individually for spots within the respective high and intermediate amplitude range by linear regression of the time delay τ and the mean square displacement of the spots as

| 4 |

The largest time delay τmax = 0.5 s was iteratively decreased to suffice the coefficient of determination R2 ≥ 0.9 for avoiding the influence of sub-diffusion or insufficient amount of data. This followed the general approach of a Brownian particle in two-dimensions. The diffusions less than Dmin = 0.01 μm2 s−1 are defined as non-diffusive considering the spatiotemporal limitations of the experimental setup and resolution of the fitted two-dimensional Gaussian function, since most led to R2 << 0.9. The calculation of the mean μ and standard deviation σ of the diffusion constant was done using the log-transformation due to its skewed normal distribution, as:

| 5 |

and

| 6 |

where N is the number of diffusion constants obtained for one experimental condition. The back-transformation was calculated then as

| 7 |

and

| 8 |

respectively, following the Finney estimator approach58. The standard error of mean (SEM) considering a confidence interval of 95% was calculated as

| 9 |

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank Beate Nitschke for help with protein preparation, Stephan Eisler, and Ke Zhou for help with the TIRF microscopy, and Sisi Fan for help with the AFM. We thank Robin Ghosh, for stimulating discussion, and the Baden-Württemberg Foundation for funding (BiofMO-6, S.N.).

Author contributions

S.N. initiated and directed the study. S.W. fluorescently labeled proteins, collected and processed the TIRF data. M.H. and S.W. wrote the software used for data and statistical analysis. S.W., M.H., and S.N. analyzed results. S.N. wrote the initial paper draft and secured funding. S.W., M.W., M.H., and S.N. edited and reviewed the draft. L.F., S.L., and M.W. provided initial expertise.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Marco Fritzsche and Gene Chong. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the paper and supporting files. All original TIRF source data are stored at the data repository of the University of Stuttgart (DaRUS): S.W., L.F., S.L., M.I.W., M.H., S.N., 2021. Data for: Correlation of mitochondrial TOM core complex stop-and-go and open-closed channel dynamics, 10.18419/darus-2158.

Code availability

The Matlab software code used for data analysis can be provided upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Marcel Hörning, Email: Marcel.Hoerning@bio.uni-stuttgart.de.

Stephan Nussberger, Email: Stephan.Nussberger@bio.uni-stuttgart.de.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-022-03419-4.

References

- 1.Wiedemann N, Pfanner N. Mitochondrial machineries for protein import and assembly. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017;86:685–714. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfanner N, Warscheid B, Wiedemann N. Mitochondrial protein organization: from biogenesis to networks and function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019;20:267–284. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0092-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scorrano L, et al. Coming together to define membrane contact sites. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1287. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09253-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chacinska A, et al. Mitochondrial presequence translocase: switching between TOM tethering and motor recruitment involves Tim21 and Tim17. Cell. 2005;120:817–829. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mokranjac D, et al. Role of Tim50 in the transfer of precursor proteins from the outer to the inner membrane of mitochondria. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:1400–1407. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e08-09-0934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bausewein T, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the TOM core complex from Neurospora crassa. Cell. 2017;170:693–700. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Araiso Y, et al. Structure of the mitochondrial import gate reveals distinct preprotein paths. Nature. 2019;575:395–401. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1680-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tucker K, Park E. Cryo-EM structure of the mitochondrial protein-import channel TOM complex at near-atomic resolution. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2019;26:1158–1166. doi: 10.1038/s41594-019-0339-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang W, et al. Atomic structure of human TOM core complex. Cell Discov. 2020;6:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-00198-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahting U, et al. The TOM core complex: the general protein import pore of the outer membrane of mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 1999;147:959–968. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill K, et al. Tom40 forms the hydrophilic channel of the mitochondrial import pore for preproteins. Nature. 1998;395:516–521. doi: 10.1038/26780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuszak AJ, et al. Evidence of distinct channel conformations and substrate binding affinities for the mitochondrial outer membrane protein translocase pore Tom40. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:26204–26217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.642173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahendran KR, Lamichhane U, Romero-Ruiz M, Nussberger S, Winterhalter M. Polypeptide translocation through the mitochondrial TOM channel: temperature-dependent rates at the single-molecule level. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:78–82. doi: 10.1021/jz301790h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poynor M, Eckert R, Nussberger S. Dynamics of the preprotein translocation channel of the outer membrane of mitochondria. Biophys. J. 2008;95:1511–1522. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.131003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Künkele K-P, et al. The preprotein translocation channel of the outer membrane of mitochondria. Cell. 1998;93:1009–1019. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemeshko SV, Lemeshko VV. Metabolically derived potential on the outer membrane of mitochondria: a computational model. Biophys. J. 2000;79:2785–2800. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76518-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang S, Romero-Ruiz M, Castell OK, Bayley H, Wallace MI. High-throughput optical sensing of nucleic acids in a nanopore array. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2015;10:986–991. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leptihn S, et al. Constructing droplet interface bilayers from the contact of aqueous droplets in oil. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:1048–1057. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mager F, Sokolova L, Lintzel J, Brutschy B, Nussberger S. LILBID-mass spectrometry of the mitochondrial preprotein translocase TOM. J. Phys. Condens. Matter Inst. Phys. J. 2010;22:454132. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/22/45/454132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka M, Sackmann E. Polymer-supported membranes as models of the cell surface. Nature. 2005;437:656–663. doi: 10.1038/nature04164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahting U, et al. Tom40, the pore-forming component of the protein-conducting TOM channel in the outer membrane of mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:1151–1160. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benz, R. Bacterial and Eukaryotic Porins: Structure, Function, Mechanism (John Wiley & Sons, 2006).

- 23.Owen DM, Williamson D, Rentero C, Gaus K. Quantitative microscopy: protein dynamics and membrane organisation. Traffic. 2009;10:962–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spector J, et al. Mobility of BtuB and OmpF in the Escherichia coli outer membrane: implications for dynamic formation of a translocon complex. Biophys. J. 2010;99:3880–3886. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alenghat FJ, Golan DE. Membrane protein dynamics and functional implications in mammalian cells. Curr. Top. Membr. 2013;72:89–120. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-417027-8.00003-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heine M, Ciuraszkiewicz A, Voigt A, Heck J, Bikbaev A. Surface dynamics of voltage-gated ion channels. Channels. 2016;10:267–281. doi: 10.1080/19336950.2016.1153210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kusumi A, Tsunoyama TA, Hirosawa KM, Kasai RS, Fujiwara TK. Tracking single molecules at work in living cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:524–532. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobson K, Liu P, Lagerholm BC. The lateral organization and mobility of plasma membrane components. Cell. 2019;177:806–819. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haggie PM, Kim JK, Lukacs GL, Verkman AS. Tracking of quantum dot-labeled CFTR shows near immobilization by C-terminal PDZ interactions. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:4937–4945. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e06-08-0670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider R, et al. Mobility of calcium channels in the presynaptic membrane. Neuron. 2015;86:672–679. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawato S, Sigel E, Carafoli E, Cherry RJ. Rotation of cytochrome oxidase in phospholipid vesicles. Investigations of interactions between cytochrome oxidases and between cytochrome oxidase and cytochrome bc1 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:7518–7527. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)68993-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas DD, Hidalgo C. Rotational motion of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 1978;75:5488–5492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.11.5488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoffmann W, Sarzala MG, Chapman D. Rotational motion and evidence for oligomeric structures of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-activated ATPase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 1979;76:3860–3864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.8.3860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuzmenko A, et al. Single molecule tracking fluorescence microscopy in mitochondria reveals highly dynamic but confined movement of Tom40. Sci. Rep. 2011;1:195. doi: 10.1038/srep00195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sukhorukov VM, et al. Determination of protein mobility in mitochondrial membranes of living cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2010;1798:2022–2032. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koppel DE, Sheetz MP, Schindler M. Matrix control of protein diffusion in biological membranes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 1981;78:3576–3580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramadurai S, et al. Lateral diffusion of membrane proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:12650–12656. doi: 10.1021/ja902853g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shiota T, et al. Molecular architecture of the active mitochondrial protein gate. Science. 2015;349:1544–1548. doi: 10.1126/science.aac6428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt O, et al. Regulation of mitochondrial protein import by cytosolic kinases. Cell. 2011;144:227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Araiso Y, Imai K, Endo T. Structural snapshot of the mitochondrial protein import gate. FEBS J. 2021;288:5300–5310. doi: 10.1111/febs.15661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Wilpe S, et al. Tom22 is a multifunctional organizer of the mitochondrial preprotein translocase. Nature. 1999;401:485–489. doi: 10.1038/46802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferhan AR, et al. Solvent-assisted preparation of supported lipid bilayers. Nat. Protoc. 2019;14:2091–2118. doi: 10.1038/s41596-019-0174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gomkale R, et al. Mapping protein interactions in the active TOM-TIM23 supercomplex. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:5715. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26016-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jin P, Jan LY, Jan Y-N. Mechanosensitive ion channels: structural features relevant to mechanotransduction mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2020;43:207–229. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-070918-050509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kefauver JM, Ward AB, Patapoutian A. Discoveries in structure and physiology of mechanically activated ion channels. Nature. 2020;587:567–576. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2933-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deng Z, et al. Structural mechanism for gating of a eukaryotic mechanosensitive channel of small conductance. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3690. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17538-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee CP, et al. MSL1 is a mechanosensitive ion channel that dissipates mitochondrial membrane potential and maintains redox homeostasis in mitochondria during abiotic stress. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2016;88:809–825. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Y, et al. Structural insights into a plant mechanosensitive ion channel MSL1. Cell Rep. 2020;30:4518–4527.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walewska A, Kulawiak B, Szewczyk A, Koprowski P. Mechanosensitivity of mitochondrial large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Bioenerg. 2018;1859:797–805. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ge J, et al. Structure of mouse protocadherin 15 of the stereocilia tip link in complex with LHFPL5. eLife. 2018;7:e38770. doi: 10.7554/eLife.38770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martinac B. Mechanosensitive ion channels: molecules of mechanotransduction. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:2449–2460. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Y, et al. Push-to-open: the gating mechanism of the tethered mechanosensitive ion channel NompC. eLife. 2021;10:e58388. doi: 10.7554/eLife.58388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brohawn SG, Campbell EB, MacKinnon R. MacKinnon, R. Physical mechanism for gating and mechanosensitivity of the human TRAAK K+ channel. Nature. 2014;516:126–130. doi: 10.1038/nature14013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lomize AL, Todd SC, Pogozheva ID. Spatial arrangement of proteins in planar and curved membranes by PPM 3.0. Protein Sci. 2022;31:209–220. doi: 10.1002/pro.4219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Joo, C. & Ha, T. Single-molecule FRET with total internal reflection microscopy. In Single-molecule techniques: a laboratory manual (eds. Selvin, P. R. & Ha, T.) 3–36 (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2008).

- 56.Bieligmeyer M, et al. Reconstitution of the membrane protein OmpF into biomimetic block copolymer–phospholipid hybrid membranes. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2016;7:881–892. doi: 10.3762/bjnano.7.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vicente NB, Zamboni JED, Adur JF, Paravani EV, Casco VH. Photobleaching correction in fluorescence microscopy images. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2007;90:012068. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/90/1/012068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Finney DJ. On the distribution of a variate whose logarithm is normally distributed. Suppl. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1941;7:155–161. doi: 10.2307/2983663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the paper and supporting files. All original TIRF source data are stored at the data repository of the University of Stuttgart (DaRUS): S.W., L.F., S.L., M.I.W., M.H., S.N., 2021. Data for: Correlation of mitochondrial TOM core complex stop-and-go and open-closed channel dynamics, 10.18419/darus-2158.

The Matlab software code used for data analysis can be provided upon reasonable request.