Abstract

Purpose:

To describe the clinical profile of patients presenting with uveitis following COVID-19 infection at a tertiary care eye hospital in South India.

Methods:

In this retrospective chart review, all consecutive cases presenting with an acute episode of intraocular inflammation and a history of COVID-19 infection diagnosed within the preceding 6 weeks, between March 2020 and September 2021, were included. Data retrieved and analyzed included age, sex, laterality of uveitis, and site of inflammation. The diagnosis was categorized based on the SUN working group classification criteria for uveitis. Details regarding clinical features, investigations, ophthalmic treatment given, response to treatment, ocular complications, and status at last visit were also accessed. Statistical analysis of demographical data was done using Microsoft Excel 2019.

Results:

Twenty-one eyes of 13 patients were included in this hospital-based retrospective observational study. The study included six male and seven female patients. The mean age was 38 ± 16.8 years. Eight patients had bilateral involvement. Seven patients were diagnosed with anterior uveitis, three with intermediate uveitis, one with posterior uveitis, and two with panuveitis. All patients responded well to treatment and were doing well at their last visit. Two patients had complications that necessitated surgical treatment, following which they recovered good visual outcomes.

Conclusion:

With prompt diagnosis and appropriate management, all the patients with uveitis post-COVID-19 infection recovered with good visual outcomes. Thus, ophthalmologists must be aware of the possible uveitic manifestations following even uneventful COVID-19 infection.

Keywords: Anterior uveitis, COVID-19, intermediate uveitis, neuroretinitis, panuveitis, uveitis

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). It was first reported in December 2019 and has since spread rapidly worldwide, causing a global pandemic as declared by the World Health Organization in March 2020.

The SARS-CoV-2 is a member of the Coronaviridae family of viruses that can cause ocular manifestations through various mechanisms.[1] Coronaviruses have been shown to cause ocular infection in other mammals; thus, the possibility of SARS-CoV-2-related ocular involvement is very likely.[1]

Initial reports of ocular involvement included anterior segment manifestations such as conjunctival hyperemia, chemosis, epiphora, and conjunctivitis.[2] However, new clinical presentations and ocular features associated with various stages of the COVID-19 infection are being reported worldwide.[2] Herein, we report a case series of 13 patients who presented with various uveitic manifestations following a recent recovery from COVID-19 infection.

Methods

This was a retrospective observational study conducted at a tertiary eye care center in South India. Patients presenting to the uveitis department with an acute episode of intraocular inflammation and a history of COVID-19 infection diagnosed within the preceding 6 weeks, between March 2020 and September 2021, were included.

The study was approved by the institutional research and ethics committee, and the research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Only patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 followed by an acute episode of uveitis were included in the study.

Cases that had a reactivation of ocular inflammation due to inadequate treatment or cessation of medication were excluded. Teleconsultation patients were also excluded due to inadequate clinical documentation.

Clinical records of included patients were reviewed for demographic data and ocular history with particular attention to the duration between diagnosis of COVID-19 and onset of visual symptoms. In addition, the details of the COVID-19 episode, such as domiciliary or hospital-based treatment, the use of systemic steroids, and complications, were noted when available.

Data from records were retrospectively abstracted into a case sheet prepared for the study. All patients had a complete history, visual acuity, ophthalmic examination with refraction, slit-lamp biomicroscopy, applanation tonometry, and indirect ophthalmoscopy. In addition, imaging findings as applicable were retrieved for analysis (B-scan ultrasonography (B-scan), fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA), and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (OCT)). Laboratory investigations for an etiological workup and associated systemic conditions were done in all patients.

Data retrieved and analyzed included age, sex, laterality of uveitis, and site of inflammation. The diagnosis was categorized based on the SUN working group classification criteria for uveitis.[3] Details regarding ophthalmic treatment given, response to treatment, ocular complications, and status at last visit were also accessed.

Statistical analysis of demographic data was performed using Microsoft Excel 2019.

Results

Twenty-one eyes of 13 patients were included in this hospital-based retrospective observational study.

COVID-19 diagnosis

Eleven patients had positive real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for SARS-CoV-2 from nasopharyngeal swab during the COVID-19 infection. The remaining two patients with negative RT-PCR results at presentation were retrospectively diagnosed with a history of recent COVID-19 infection by the in-house physician based on medical history, clinical examination, and chest HRCT findings.[4,5,6]

Demographic and clinical profile

The study included six male and seven female patients. The mean age was 38 ± 16.8 years; two males were children aged 7 and 12 years. The median (interquartile range (IQR)) follow-up for all 13 patients was 34 days (12–57 days).

Of the 13 patients in this study, eight patients had bilateral involvement. Seven patients were diagnosed with anterior uveitis, three with intermediate uveitis, one with posterior uveitis, and two with panuveitis, as per the SUN working group classification criteria for uveitis.[3]

On comparing each patient’s presentation date and the timeline of vaccination rollout and eligibility ages in India, only one patient was eligible for vaccination at the time of presentation and had already received two doses of Covishield® vaccine 6 months prior to getting infected.

The remaining ten eligible patients (two children being ineligible) were subsequently noted to have received at least one dose of vaccine uneventfully on follow-up.

All demographic data with the clinical profile are elaborated in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Clinical summary of patients who presented with non-granulomatous anterior uveitis

| Patient Number (Age/Sex/Eye) | Onset Following Covid-19 Diagnosis (RT-PCR) | Treatment | Complications | Outcome At LFU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Uveitis Resolved | Visual Outcome | ||||

| Patient 1 (33/M/OS) | 3 Weeks | Topical Steroids | Nil | Yes | 6/6 |

| Patient 2 (35/F/OU) | 6 Weeks | Topical Steroids | Nil | Yes | 6/6, 6/6 |

| Patient 3 (36/M/OD) | 3 Weeks | Topical Steroids | Nil | Yes | 6/6 |

| Patient 4 (42/M/OU) | 3 Weeks | Topical Steroids | Nil | Yes | 6/6, 6/6 |

| Patient 5 (56/F/OD) | 6 Weeks | Topical Steroids | Nil | Yes | 6/6 |

| Patient 6* (65/M/OU) | 3 Weeks | Topical Steroids | Nil | Yes | 6/6, 6/6 |

| Patient 7 (28/F/OU) | 6 Weeks | Topical Steroids | BADI | Yes | 6/6, 6/6 |

*Positive history of a similar episode in the past. LFU – Last follow-up. BADI – Bilateral Acute Depigmentation of Iris

Table 2.

Clinical summary of patients who presented with intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis

| Patient number (Age/Sex/Eye/Diagnosis) | Onset following COVID-19 diagnosis | Treatment | Complications | Outcome at LFU | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Duration of Follow up (Days) | Uveitis Resolved | Visual Outcome | ||||

| Patient 8 (52/F/OS/IU*) | 3 Weeks† | Topical, Oral Steroids | RRD | 375 | Yes | 6/18 |

| Patient 9 (38/F/OS/IU) | 6 Weeks‡ | Oral Steroids, MMF | Nil | 14 | Yes | 6/6 |

| Patient 10 (57/F/OU/IU*) | 3 Weeks‡ | Oral Steroids | Nil | 57 | Yes | 6/9, 6/9 |

| Patient 11 (37/F/OU/PU) | 5 Weeks† | Oral Steroids | Nil | 56 | Yes | 6/12, 6/7.5 |

| Patient 12 (12/M/OU/PANU) | 2 Weeks‡ | IVMP, Topical, Oral Steroids, MTX | Complicated Cataract | 95 | Yes | 6/7.5, 6/9 |

| Patient 13 (7/M/OU/PANU) | 2 Weeks‡ | Topical, Oral Steroids | Complicated Cataract | 395 | Yes, Pseudophakia OU | 6/7.5, 6/7.5 |

LFU – Last follow-up, IU – Intermediate Uveitis, PU – Posterior Uveitis, PANU – Panuveitis, MMF – Mycophenolate mofetil, IVMP – Intravenous Methylprednisolone, MTX – Methotrexate, RRD – Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. *Positive history of a similar episode in the past †Tentatively - retrospective COVID-19 diagnosis (Clinical and HRCT based) ‡ RT-PCR Diagnosis

Anterior uveitis

Eleven eyes of seven patients had acute non-granulomatous anterior uveitis (NGAU). Four patients had bilateral involvement. Four patients were male, and three were female (mean age: 42 ± 13.5 years). The median (IQR) duration of follow-up for the seven patients with anterior uveitis was 12 days (range: 1.5–28.5 days).

For six patients, this was the first episode of acute NGAU and they had no significant medical or ocular history other than the history of a recent COVID-19 infection. However, one patient, a 65-year-old gentleman with acute bilateral NGAU, had a history of a similar episode 2 months before the present episode.

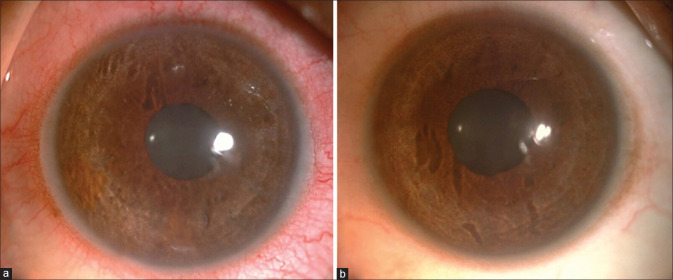

Four patients had the onset of visual symptoms of photophobia, redness, and pain within 3 weeks of the diagnosis, and the remaining three patients had onset within 6 weeks post-COVID-19 diagnosis. All patients had mild circumcorneal congestion, flare 1+, and cells 1+. In addition, fine KPs inferiorly were present bilaterally in two patients. A third patient had pigments on the endothelium and dispersed in the anterior chamber in both eyes due to bilateral acute depigmentation of the iris (BADI) [Fig. 1].

Figure 1.

Patient 7 with BADI. Slit-lamp photograph of the right eye (a) and left eye (b) showing non transilluminating depigmentation of the iris

All patients had BCVA 6/6 at the initial and last visit. They were treated with topical steroids and cycloplegics, and all responded well to the medication, with no recurrences or subsequent complications during the study period. The salient features of these seven patients with NGAU are summarized in Table 1.

Intermediate uveitis

Three female patients had presented with intermediate uveitis.

For a 38-year-old lady who presented with floaters in her left eye 6 weeks following her COVID-19 diagnosis, this was the first episode of intermediate uveitis. Her BCVA was 6/6 in the affected eye, and she had vitreous cells, which resolved completely with topical steroids and a short course of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF).

The second patient had her last episode of bilateral intermediate uveitis 12 years back, and this episode following COVID-19 was the first reactivation since. She presented with blurring of vision and floaters in both eyes. On examination, she had vitreous cells and cystoid macular edema (CME). She was initiated on topical and oral steroids, and at her last visit, she felt symptomatically better. Her BCVA OU had improved to 6/9, the inflammation had reduced, and CME was resolving.

The third patient was a one-eyed 52-year-old lady with a history of intermediate uveitis in her good left eye treated with antitubercular therapy 16 years ago. She presented with blurring of vision and floaters with BCVA of 6/9. She was diagnosed with reactivation of intermediate uveitis with vasculitis and started on steroids. On evaluating her systemic status for reactivation of tuberculosis with an HRCT of the chest, the radiologist diagnosed her to have resolving COVID-19 pneumonia with multifocal ground-glass opacities in the left lateral and posterior segments of lungs and a CORAD score of 4. The patient returned 1 month later with a sharp drop in vision to CF1M in the left eye. Her inflammation had resolved with systemic steroids; however, the vitreous condensation had caused a secondary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. She underwent vitrectomy, laser photocoagulation, and silicone oil injection. One year later, on her last visit, she was doing well with a BCVA of 6/9.

Posterior uveitis

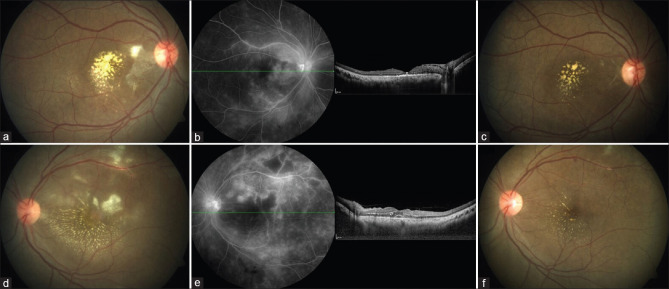

A 37-year-old lady presented with blurring vision for 1 month in her right eye and 2 weeks in the left eye. She had a history of fever, which resolved a week before the onset of visual symptoms. On examination, she was diagnosed with bilateral post fever neuro retinitis [Fig. 2a-e], and her BCVA was 6/36 N36 OU. On physician consultation, she was diagnosed with resolving COVID-19 infection based on history and HRCT findings. She was initiated on systemic steroids, and on review a month later, she was symptomatically better. Her BCVA was 6/12 OD and 6/7.5 in OS, and on examination, the inflammation was resolving in both eyes [Fig. 2c and f].

Figure 2.

Patient 11 with bilateral post fever retinitis. (a and d) Fundus photography of right (a) and left (d) eyes - multiple retinitis patches at the macula and peripapillary region, macular exudates. (b and e) Late phase of FFA of right (b) and left (e) eyes showing hypofluorescent areas with hyperfluorescent edges corresponding to the retinitis patches and disc leakage. OCT of right (b) eye showing resolved macular edema and left eye (e) showing subretinal and intraretinal fluid. (c and f) Fundus photography of right (c) and left (f) eyes at the last visit showing considerable inflammation resolution

Panuveitis

Two boys of 7 and 12 years of age presented with bilateral panuveitis within 2 weeks following the COVID-19 infection.

The 12-year-old boy had a first episode of blurring vision and floaters in both eyes 2 weeks after the diagnosis of COVID-19. The COVID-19 episode was uneventful, and he had received domiciliary care and systemic azithromycin. On examination, he had a BCVA of 6/12 in both eyes. In addition, he had 2+ cells and flare in the anterior chamber, posterior synechiae, early posterior subcapsular cataract, vitreous cells, and disc hyperemia in both eyes. Pediatrician opinion was sought, considering the possibility of an evolving multi-system inflammatory syndrome following COVID-19 infection (MIS-C). Apart from the presence of COVID-19 antibodies and evidence of resolving COVID-19 pneumonia in chest HRCT, the remaining blood and urine parameters were within normal limits, and the child was initiated on systemic steroids. He started improving symptomatically, and after a month, methotrexate was added. Both drugs were tapered at 2.5 mg/month, and at last follow-up four months later, inflammation was resolving with BCVA 6/7.5 OD and 6/9 OS.

A seven-year-old boy presented with redness, photophobia, and decreased vision of 10-day duration. The referring ophthalmologist had initially diagnosed bilateral conjunctivitis, and subsequently, the child was treated for anterior uveitis with frequent topical steroids, cycloplegics, and empirical systemic antibiotics.

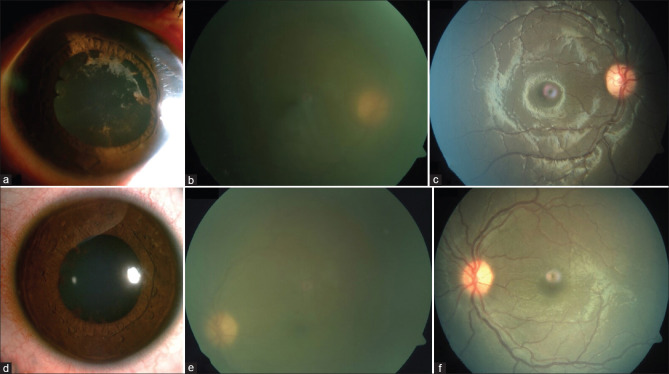

Past medical history revealed that the previously healthy child was admitted 1 month earlier for fever, loose stools, and cough and had tested COVID-19 positive (RT-PCR) with a raised CRP (43 mg/L), lymphopenia (20%), and neutrophilia (75%). After 3 weeks, the child was afebrile and active on presentation. His BCVA was 6/60 OD and 6/18 OS. Anterior chamber showed 3+ cells in the right eye and 2+ cells in the left eye. Both eyes had posterior synechiae and dense vitritis with a hazy view of the disc in the right eye [Fig. 3a-e]. Ultrasound B-scan showed a moderate number of low reflective posterior vitreous echoes in both eyes. A provisional diagnosis of bilateral panuveitis was considered. His blood tests were normal except for a mildly raised platelet count (4.7 lac/μL), diagnosed as reactive thrombocytosis by the pediatrician in light of his recent COVID-19 infection.

Figure 3.

Patient 13 with bilateral panuveitis. (a and d) Slit-lamp photograph of right (a) and left (d) eyes showing posterior synechiae. (b and e) Color fundus photography at presentation of right (b) eye showing the severe hazy view with disc barely visible and left (e) eye showing moderate haze. (c and f) Color fundus photography at last visit of right (c) and left (f) eyes showing resolution of inflammation

He was administered a three-day course of IV methylprednisolone (IVMP) followed by oral and topical steroids. As the inflammation resolved, posterior synechiae broke, vitreous inflammation was consolidating, and UBM had shown the presence of cyclitic membranes causing hypotony in both eyes, which resolved in time. Subsequently, he was noted to have a steroid response for which anti-glaucoma medication was also added. The systemic steroids were tapered gradually and stopped over 11 months. Two months later, he underwent surgery for complicated cataract in both eyes under cover of systemic steroids and methotrexate. Two months post-surgery, the steroids have been tapered and stopped; he continues to be on methotrexate and is doing well [Fig. 3c and f].

Clinical details of patients with intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis are summarized in Table 2. The median (IQR) duration of follow-up for these six patients was 76 days (range: 56.25–305 days).

Discussion

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis observed that the overall percentage of the ocular manifestations was approximately 11% and that the common ophthalmic manifestations reported with COVID-19 were ocular pain, redness, and follicular conjunctivitis.[7]

Diagnosis

Eleven patients in our study were diagnosed with COVID-19 by using the RT-PCR test. Two patients were diagnosed clinically and radiologically as they had negative RT-PCR at presentation. Mallet et al.[6] reported that COVID-19 RT-PCR may be negative when tested 10 days post the onset of symptoms. This explains the negative result obtained in these two patients. The literature has well documented the significance of the radiological and clinical diagnoses of COVID-19 in patients with negative RT-PCR results.[4,5]

The ophthalmological diagnosis was based on SUN working group classification for uveitis.[3]

Anterior uveitis

In our study, seven patients presented with acute NGAU. This was the first episode of NGAU for six patients, and we postulate that the uveitis could be due to post-infection immune dysregulation. Most of these patients developed symptoms within 1–2 months, correlating with the period of immunological seroconversion.[8]

Iriqat et al.[9] reported a case of anterior uveitis in a patient after recovering from COVID-19 that was severe with hypopyon and resolved with topical and systemic steroids therapy. In contrast, all our patients had mild NGAU that responded well to a single tapering course of topical steroids and cycloplegics and had no complications or recurrences during the study period. In addition, the patients did not have raised IOP, and all recovered without using antiviral medication, which may indicate a possible underlying immunogenic etiology of NGAU.

Reactivation of acute anterior uveitis has been reported by Sanjay et al.[10] One patient in our study had a history of NGAU 2 months before, which resolved with 2 weeks of topical steroids. His routine investigations were normal, and this episode resolved well.

A case of bilateral acute iris transillumination associated with COVID-19 has been reported by Yagci et al.[11] In our series, one patient with NGAU being treated with topical steroids had developed bilateral non-transilluminating depigmentation of the iris and pigment dispersion in the anterior chamber with no raised IOP after 2 weeks. To our knowledge, this may be the first case of bilateral acute depigmentation of iris reported from India following COVID-19 infection.

Bilateral anterior uveitis associated with MIS-C has been reported in the pediatric and adult age groups.[12,13,14] However, in our study, all patients with NGAU had an RT-PCR positive, asymptomatic COVID-19 infection managed with domiciliary quarantine alone, with no related sequelae or other systemic diseases. Furthermore, in the absence of systemic symptoms and ocular vascular signs, the relevance of serum biomarkers of systemic inflammation and hypercoagulation such as IL-2, D-dimer, and serum ferritin in these patients is speculative.[15] However, without other triggers, the temporal association with COVID-19 may be assumed to be causative.

Severe COVID-19 has been associated with an increased viral load, early seroconversion, and high IgG levels.[16] Mild infection like in our patients has been shown to cause a slower seroconversion and prolonged viral shedding. This results in late viral clearance, and the prolonged exposure to viral antigens also leads to raised IgG levels at 6–8 weeks.[17]

The role of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR 4) in COVID-19 immunopathogenesis has been reported in the literature.[18] These TLR 4 can be activated by viruses in the acute stage and later by even viral remnants such as the shed spike glycoprotein.[19] TLR 4 in iris pigment epithelium is more sensitive to pathogen-associated molecular patterns than TLR 4 in retinal pigment epithelium.[20,21] Thus, we hypothesize that the pro-inflammatory role and increased sensitivity of TLR 4 present anteriorly may cause a relatively increased incidence of anterior uveitis following SARS-CoV-2 infection.

BADI has been attributed to possible viral infection or reaction to drugs.[22] TLR 4 has also been known to cause apoptosis in some situations, and such a similar apoptosis of iris pigment epithelium leading to iris depigmentation and pigment release into the anterior chamber could be the reason for the clinical presentation of BADI in our series.[23,24,25]

Intermediate uveitis

Among the three patients with intermediate uveitis, inflammation resolved with systemic steroids in all and additional MMF in one. However, one patient subsequently developed rhegmatogenous retinal detachment and required surgical management.

One case of vitritis with posterior uveitis associated with COVID-19 infection has been reported in the literature.[9] Our patients did not have any associated neural or retinochoroidal inflammation and fitted the intermediate uveitis classification as per SUN working group guidelines.[3]

No other causes for intermediate uveitis were identified in these patients. It has been postulated that COVID-19 may precipitate a transient autoimmune response with resultant ocular inflammation in some patients. Reactivation of quiescent uveitis has also been reported post-COVID-19 infection.[10]

Posterior uveitis

This study included a patient with bilateral post fever neuro retinitis following COVID-19. Other causes of retinitis were ruled out. In contrast to a previous case report of COVID-19-associated post-fever retinitis, our patient did not have any systemic symptoms, responded well to systemic steroids, and did not develop any complications such as retinal vascular occlusions.[26]

Panuveitis with optic neuritis has been reported both as an initial presentation of COVID-19 and following recovering from COVID-19.[27,28]

Panuveitis

The two boys in this study had presented with bilateral panuveitis following COVID-19 infection. While there are several case reports of uveitis in children associated with MIS-C, neither patient in our study had associated MIS-C at presentation.[12,13,29]

SARS-CoV2-RNA has been detected in the vitreous sample of a patient with bilateral panuveitis and optic neuritis 1 month following COVID-19 infection.[28]

As the patients belonged to the pediatric age group, aqueous and vitreous sampling was deferred. Both children responded well to treatment, and consequently, invasive procedures were not done.

Similar to the case reported by Hosseini et al.,[28] one patient in our study required IVMP to control the inflammation.

Outcome

All 13 patients in our series responded well to treatment and were doing well at their last visit. Despite control of inflammation, two patients had developed complications necessitating surgery, following which they recovered good visual outcomes.

Limitations

The main limitation of our study is the inability to confirm the diagnosis as secondary to COVID-19 infection. Barring the temporal association, it is more of a diagnosis of exclusion.

While RT-PCR studies and inflammatory biomarker analysis of aqueous and vitreous samples of these patients may shed light on the immunopathogenesis, invasive procedures are done only as per need. The excellent response to treatment and ethical considerations did not warrant intraocular sampling in any of our patients. Moreover, it has been reported that viral RNA has been detected from ocular specimens only in 3.5% of patients.[7]

Ours was a retrospective observational study conducted in the Uveitis department at a tertiary eye care center with a small sample size. As most cases of NGAU are managed by comprehensive ophthalmologists, there is a high probability that the incidence of NGAU following COVID-19 in the community may be higher. In our experience, the patients responded well with a single course of topical steroids and cycloplegics, implying that there would be no reason for the primary ophthalmologist to refer such patients to higher centers. A prospective study following up on COVID-19 patients at least for 3 months after recovery for possible ocular inflammation will be more insightful.

Conclusion

When the SARS-CoV-2 emerged in late 2019, the world knew little about it. Now the pandemic continues to evolve with new viral variants. The ophthalmic community is also witnessing an upsurge in knowledge about the virus. Our case series highlights some uveitic manifestations following an uneventful COVID-19 infection. However, further research is required to understand the immunopathogenesis of these uveitic presentations. It is prudent for every ophthalmologist in this pandemic era to be aware of these possibilities, as with prompt diagnosis and appropriate management, these patients recover well with good visual outcomes.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Seah I, Agrawal R. Can the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) affect the eyes? A review of Coronaviruses and ocular implications in humans and animals. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;28:391–5. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1738501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sen M, Honavar SG, Sharma N, Sachdev MS. COVID-19 and eye: A review of ophthalmic manifestations of COVID-19. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69:488–509. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_297_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT. Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the first international workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:509–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Korkmaz I, Dikmen N, Keleş FO, Bal T. Chest CT in COVID-19 pneumonia: Correlations of imaging findings in clinically suspected but repeatedly RT-PCR test-negative patients. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med. 2021;52:96. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sureka B, Garg PK, Saxena S, Garg MK, Misra S. Role of radiology in RT-PCR negative COVID-19 pneumonia: Review and recommendations. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10:1814–7. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2108_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mallett S, Allen AJ, Graziadio S, Taylor SA, Sakai NS, Green K, et al. At what times during infection is SARS-CoV-2 detectable and no longer detectable using RT-PCR-based tests? A systematic review of individual participant data. BMC Med. 2020;18:346. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01810-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aggarwal K, Agarwal A, Jaiswal N, Dahiya N, Ahuja A, Mahajan S, et al. Ocular surface manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0241661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhao J, Yuan Q, Wang H, Liu W, Liao X, Su Y, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with Novel Coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2027–34. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iriqat S, Yousef Q, Ereqat S. Clinical profile of COVID-19 patients presenting with uveitis-A short case series. Int Med Case Rep J. 2021;14:421–7. doi: 10.2147/IMCRJ.S312461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sanjay S, Mutalik D, Gowda S, Mahendradas P, Kawali A, Shetty R. “Post Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) reactivation of a quiescent unilateral anterior uveitis”. SN Compr Clin Med. 2021:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s42399-021-00985-2. doi: 10.1007/s42399-021-00985-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yagci BA, Atas F, Kaya M, Arikan G. COVID-19 associated bilateral acute iris transillumination. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29:719–21. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2021.1933073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wong Chung JERE, Engin Ö, Wolfs TFW, Renson TJC, de Boer JH. Anterior uveitis in paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2. Lancet. 2021;397:e10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00579-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Öztürk C, Yüce Sezen A, SavaşŞen Z, Özdem S. Bilateral acute anterior uveitis and corneal punctate epitheliopathy in children diagnosed with multisystem inflammatory syndrome secondary to COVID-19. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29:700–4. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2021.1909070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bettach E, Zadok D, Weill Y, Brosh K, Hanhart J. Bilateral anterior uveitis as a part of a multisystem inflammatory syndrome secondary to COVID-19 infection. J Med Virol. 2021;93:139–40. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sanjay S, Srinivasan P, Jayadev C, Mahendradas P, Gupta A, Kawali A, et al. Post COVID-19 ophthalmic manifestations in an Asian Indian male. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29:656–61. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1870147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Masiá M, Telenti G, Fernández M, García JA, Agulló V, Padilla S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion and viral clearance in patients hospitalized with COVID-19: Viral load predicts antibody response. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8:ofab005. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jin CC, Zhu L, Gao C, Zhang S. Correlation between viral RNA shedding and serum antibodies in individuals with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1280–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aboudounya MM, Heads RJ. COVID-19 and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4): SARS-CoV-2 may bind and activate TLR4 to increase ACE2 expression, facilitating entry and causing hyperinflammation. Mediators Inflamm 2021. 2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/8874339. 8874339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Olejnik J, Hume AJ, Mühlberger E. Toll-like receptor 4 in acute viral infection: Too much of a good thing. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14:e1007390. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mai K, Chui JJ, Di Girolamo N, McCluskey PJ, Wakefield D. Role of toll-like receptors in human iris pigment epithelial cells and their response to pathogen-associated molecular patterns. J Inflamm. 2014;11:20. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-11-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chuis JJY, Li MWM, Girolamo ND, Chang JH, McCluskey PJ, Wakefield D. Iris pigment epithelial cells express a functional lipopolysaccharide receptor complex. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:2558–67. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kawali A, Mahendradas P, Shetty R. Acute depigmentation of the iris: A retrospective analysis of 22 cases. Can J Ophthalmol. 2019;54:33–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2018.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fei X, He Y, Chen J, Man W, Chen C, Sun K, et al. The role of toll-like receptor 4 in apoptosis of brain tissue after induction of intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neuroinflammation. 2019;16:234. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1634-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Katare PB, Nizami HL, Paramesha B, Dinda AK, Banerjee SK. Activation of toll like receptor 4 (TLR4) promotes cardiomyocyte apoptosis through SIRT2 dependent p53 deacetylation. Sci Rep. 2020;10:19232. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75301-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cen X, Liu S, Cheng K. The Role of Toll-Like Receptor in Inflammation and Tumor Immunity. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:878. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mahendradas P, Hande P, Patil A, Kawali A, Sanjay S, Ahmed SA, et al. Bilateral post fever retinitis with retinal vascular occlusions following severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus (SARS-CoV2) infection. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021:1–6. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2021.1936564. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2021.1936564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Benito-Pascual B, Gegúndez JA, Díaz-Valle D, Arriola-Villalobos P, Carreño E, Culebras E, et al. Panuveitis and optic neuritis as a possible initial presentation of the Novel Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;28:922–5. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1792512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hosseini SM, Abrishami M, Zamani G, Hemmati A, Momtahen S, Hassani M, et al. Acute bilateral neuroretinitis and panuveitis in a patient with Coronavirus Disease 2019: A case report. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29:677–80. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2021.1894457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Karthika IK, Gulla KM, John J, Satapathy AK, Sahu S, Behera B, et al. COVID-19 related multi-inflammatory syndrome presenting with uveitis-A case report. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69:1319–21. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_52_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]