Abstract

Struma ovarii (SO) is an uncommon monodermal teratoma predominantly composed of mature thyroid tissue. Approximately 5% of SO are malignant; however, metastases are rare. A single female in her 40s, with a medical history of Graves’ disease and bilateral cystectomy 10 years prior for right endometriotic cyst and left SO, presented with an enlarging abdominal mass for 4 months. Ultrasound pelvis showed a 13.8 cm left adnexal heterogeneous solid-cystic mass with internal septations and vascularity. She underwent open left salpingo-oophorectomy and resection of fibrous nodules from the right infundibulo-pelvic ligament and fallopian tube. Histology showed highly differentiated metastatic follicular carcinoma. She subsequently underwent total thyroidectomy, total hysterectomy, right salpingo-oophorectomy, tumour debulking and omentectomy followed by radioactive iodine treatment. Four-year follow-up did not show tumour recurrence or metastases. Due to its rarity, there are no well-established guidelines for the management and follow-up of metastatic follicular carcinoma arising from SO.

Keywords: Obstetrics and gynaecology, Gynecological cancer

Background

Ovarian cancer is one of the top five frequently diagnosed malignancies in Singapore,1 and its prevalence has been increasing significantly in younger patients in some countries.2 15%–20% of ovarian tumours are germ cell tumours and the majority are mature cystic teratomas.3 Struma ovarii (SO) is a monodermal teratoma predominantly composed of mature thyroid tissue (>50% of overall tissue),4 accounting for approximately 5% of all ovarian teratomas.5 Approximately, 5% of SO turn out to be malignant; however, metastases are rare.6 Here we report a rare case of metastatic follicular carcinoma arising from SO and present the relevant literature review.

Case presentation

A single female in her 40s with a medical history of Graves’ disease on carbimazole and bilateral cystectomy 10 years prior for right endometriotic cyst and left SO, presented with an enlarging abdominal mass for 4 months. However, she did not report any compressive or constitutional symptoms.

Investigations

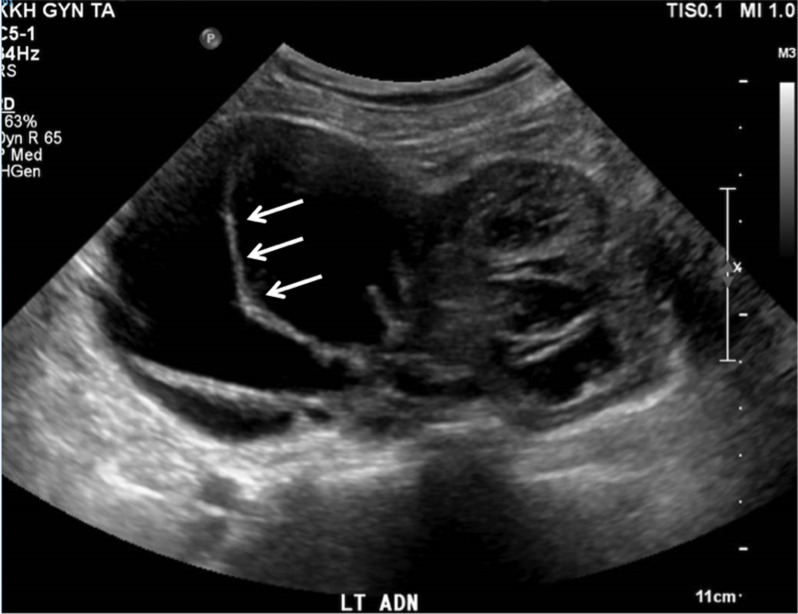

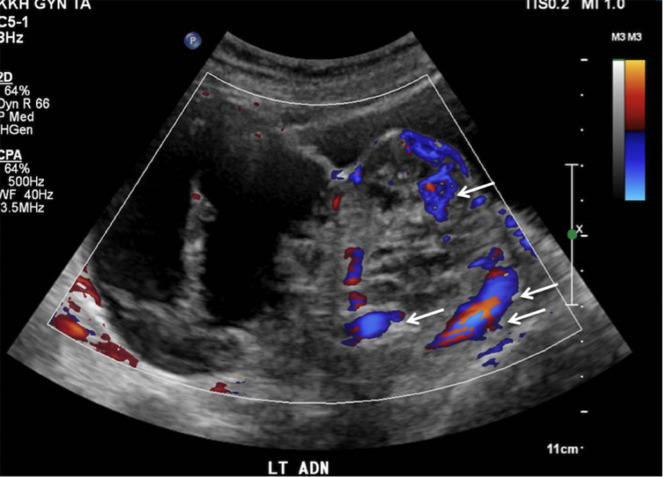

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis revealed uterine fibroids and a left adnexal cystic mass 10.7×9.6×8.4 cm, with nodular septations, thought to be ovarian in origin. There were no ascites or enlarged lymph nodes detected. Ovarian tumour markers were within the normal range (alpha-fetoprotein 3 µg/L, beta human chorionic gonadotropin <1 IU/L, cancer antigen 12 529 kU/L, carcinoembryonic antigen 1 µg/L). An ultrasound pelvis was subsequently performed and showed several uterine fibroids, ranging from 1.0×0.9×0.7 cm to 2.7×2.1×2.3 cm (intramural, right anterior wall) and a heterogeneous solid-cystic mass with internal septations and vascularity, measuring 13.8×11.6×7.1 cm in the left adnexal region (figures 1 and 2). The left ovary was not separately visualised and the right ovary was unremarkable. Her risk of malignancy index for ovarian cancer was low risk at 87 points.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound image of ovarian mass showing internal septations (arrow).

Figure 2.

Ultrasound image of ovarian mass with internal vascularity (arrow).

Treatment

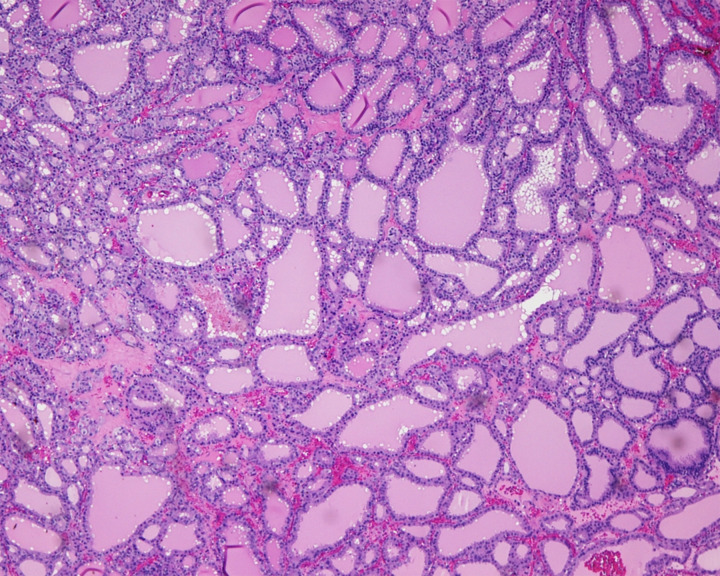

The patient was initially counselled for open unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, with intraoperative frozen section evaluation, keep in view (KIV) staging, KIV myomectomy and, if the frozen section showed malignancy, to proceed with contralateral salpingo-oophorectomy, hysterectomy, omentectomy, pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection, KIV appendectomy. She eventually underwent open left salpingo-oophorectomy as the intraoperative frozen section showed benign SO. Intraoperatively, there were fibrous nodules of less than 5 mm scattered on the bowel and peritoneal surfaces. Nodules on the right infundibulo-pelvic ligament and right fallopian tube were sampled for routine histological evaluation. On gross examination, the ovarian tumour was a complex solid-cystic mass measuring 115×60×35 mm. On histological examination, there were thyroid follicles of variable sizes containing luminal colloid (figure 3). No nuclear features of papillary carcinoma were noted. There was a focus of tumour pushing into the border of the paraovarian tissue but no frank capsular invasion. The nodules from the right infundibulo-pelvic ligament and right fallopian tube showed thyroid follicles similar to those in the ovarian tumour. In view of the presence of thyroid tissue in extra-ovarian sites, a diagnosis of highly differentiated metastatic follicular carcinoma was made. Postoperatively, the patient made an uneventful recovery.

Figure 3.

Left ovarian tumour composed of well-formed thyroid follicles, indistinguishable from struma ovarii.

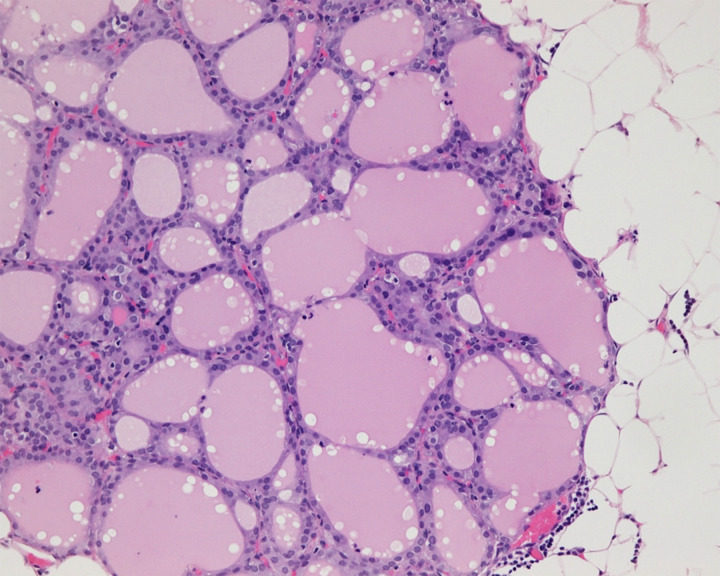

Subsequently, the patient underwent total thyroidectomy and histology showed colloid nodule and lymphocytic thyroiditis. She also underwent total hysterectomy, right salpingo-oophorectomy, tumour debulking and omentectomy followed by radioactive iodine (RAI) treatment as suggested by the multidisciplinary tumour board (MTB) comprising specialists from gynaeoncology, endocrinology, nuclear medicine, medical oncology, pathology and radiology. Final histology showed nodules of thyroid tissue in the omentum, right pelvic side wall peritoneum and on the serosal surfaces of the bladder and rectum, consistent with metastases from the highly differentiated follicular carcinoma of the left ovary (figure 4). Post RAI treatment scan showed several foci of I-131 uptake in the bowel. Single photon-emission CT showed that several foci were within loops of bowel while others were localised to the bowel wall. Overall, there were no large masses or peritoneal nodules seen. The patient was followed up with CT chest, abdomen, and pelvis 6 months later and there was no evidence of local recurrence or distant metastases.

Figure 4.

Omental nodule of thyroid tissue consistent with metastatic highly differentiated follicular carcinoma.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was placed on long-term thyroxine replacement therapy and during the 4-year follow-up period, the patient did not show evidence of recurrence or metastases.

Discussion

SO is an uncommon tumour that accounts for less than 1% of all ovarian tumours5 7 and 2.7% of all dermoid tumours (mature cystic teratomas).5 The majority of SO turn out to be benign, and the malignancy rate is only 5%–10%.8 9 Malignant SO (MSO) is usually unilateral and often affects the left ovary.10 11 Papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) is the most prevalent pathological subtype for MSO, followed by follicular variant of PTC, follicular carcinoma, mixed follicular-papillary carcinoma and poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma.12

MSO occurs most commonly in patients around 30–40 years old with widely varied clinical manifestations.13 14 The most common presenting complaints are lower abdominal pain, a palpable abdominal mass, ascites and abnormal vaginal bleeding.5 However, our patient did not have any abdominal pain at the time of presentation; rather she presented with an enlarging abdominal mass for 4 months.

Dardik et al15 found that about 8% of women with SO also have concomitant thyrotoxicosis despite not having any thyroid symptoms. MSO rarely causes thyroid dysfunction.16 Patients with SO and thyrotoxicosis do not usually have a goitre.17 The results of thyroid function tests for patients with SO causing thyrotoxicosis are the same as those with primary hyperthyroidism: thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) is low; free thyroxine (T4) and/or triiodothyronine (T3) and serum thyroglobulin (TG) are elevated.18 Our patient has a known history of Graves’ disease, diagnosed on the basis of the presence of TSH receptor antibodies, and was already on carbimazole before the discovery of the abdominal mass. There was no positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT) done prior to surgery. Her thyrotoxicosis before the surgery was thought to be due to Grave’s disease and not related to the pelvic mass. Patients with SO were hardly reported in the literature to have Graves’ disease simultaneously.19 20

No standard guidelines exist for the treatment of MSO due to its rarity. Currently, the surgical treatment options for MSO include ovarian cystectomy, unilateral or bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, total hysterectomy bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy or debulking surgery.12 A review done by Marti et al7 showed that pelvic surgery alone may be sufficient for patients with disease limited to the ovary. This was not only true for the four patients that they presented (all of them were alive and disease-free), but also for the 57 cases that they reviewed. The 25-year recurrence rate was only 7.5%.7 MSO confined to the ovary without metastases has a low risk of recurrence.18 Furthermore, patients’ desire for fertility should also be considered when deciding surgical options. In patients with MSO confined to the ovary and who have yet to complete their family, unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy may be the preferred surgery.12

There is a lack of consensus regarding the use of RAI postoperatively.6 7 21–23 In a review done by DeSimone et al,22 among patients with thyroid-type carcinoma, those who were treated with total thyroidectomy and radioactive ablation after local surgery had no disease recurrence even after 36 years. In comparison, those who were treated conservatively without additional therapy such as total thyroidectomy, RAI and intraperitoneal chronic phosphate for metastatic intraperitoneal disease, with thyroid suppression24 had a recurrence rate of 50%. Our patient who had highly differentiated metastatic follicular carcinoma, underwent RAI treatment after surgery as recommended by the MTB. She has not shown any evidence of recurrence or metastases to date, 4 years after the diagnosis.

Some studies showed that RAI and thyrotropin suppression may improve survival rates.10 25 In addition, levothyroxine can be given to patients with MSO postoperatively to suppress TSH to the lower limit of the normal range. Our patient was placed on long-term levothyroxine replacement and follow-up TSH values were kept below 0.1 mIU/L.

Highly differentiated follicular carcinoma of ovarian origin (HDFCO) is a variant of MSO that characteristically cannot be diagnosed on the primary tumour (ovary) due to its harmless histological appearance.16 The diagnosis is usually made when there is evidence of tumour spread beyond the ovary, revealing its aggressive biological behaviour. Hence, in our patient, it was not possible at the frozen section to determine if the tumour was benign or malignant, thus only unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was performed initially. On the final histology, the diagnosis of HDFCO was made in view of the presence of the extra-ovarian tumour in the right infundibulo-pelvic ligament and right fallopian tube. The differential diagnoses of SO with extraovarian dissemination include metastatic typical thyroid cancer, HDFCO, and so-called peritoneal strumosis. Peritoneal strumosis was the term used to describe the presence of benign-looking thyroid tissue in the peritoneal cavity in the presence of an SO, and pathological examination of these implants may show multiple nodules of mature thyroid tissue of varying size similar to SO.26 However, Roth and Karseladze question the existence of strumosis as a distinct clinico-pathological entity given their diagnosis of HDFCO.16

The size of the strumal component can be used as a prognosticating factor. For instance, Robboy et al27 proposed that if the size of the strumal component is more than or equal to 12 cm, there is a higher risk of recurrence. Also, Shaco-Levy et al28 suggested that pathological factors predictive of poorer prognosis include overall tumour size 10 cm or more, strumal component more than 80% and mitotic count 5 or more per 10 high power fields. Some authors raised the possibility that the size of the carcinomatous component rather than the size of the strumal component might have a prognosticative value in patients with MSO.12 Other poor prognostic findings that have been proposed include the presence of adhesions, ascites of 1 L or more, and ovarian serosal rent27 or FIGO stage IV disease, age 45 years or older, and poorly differentiated tumour.29 One study did not identify any potential risk factors in MSO confined to the ovary.12

There is a lack of guidelines on the follow-up strategy for MSO confined to the ovary due to its scarcity. Some authors suggest the use of serum TG, serum TG antibody (TGAb), and imaging for MSO follow-up. To use serum TG for the follow-up to monitor for recurrence and metastases, patients are recommended to undergo prophylactic total thyroidectomy to exclude a primary thyroid carcinoma followed by RAI.22 23 Some studies suggested the follow-up interval to be 6–12 months for patients with MSO and to monitor serum TG and TGAb as per the guidelines for thyroid cancer.30 Extremely high TG levels suggest metastatic disease. Our patient underwent thyroidectomy and was on regular follow-up every 6 months with serum TG and TGAb assessments. She did not show any evidence of recurrence or metastases during the follow-up period.

In conclusion, metastatic follicular carcinoma arising from SO is rare. Due to its scarcity, there is a lack of established consensus regarding management and follow-up. However, a combination of pelvic surgery, thyroidectomy, RAI and thyrotropin suppression can be considered for patients with metastatic MSO as total thyroidectomy not only allows the exclusion of primary thyroid carcinoma but also allows RAI ablation therapy for micro-metastases31 and thus reduce the recurrence rate.

Learning points.

Metastatic follicular carcinoma arising from struma ovarii (SO) is a rare condition.

For patients with metastatic malignant SO (MSO) and who have completed their family, a combination of local surgery, total thyroidectomy and radioactive iodine therapy can be considered.

Regular follow-up with serum thyroglobulin (TG), serum TG antibody and imaging are needed for patients with MSO who have undergone total thyroidectomy.

Footnotes

Contributors: YHGN and YL conceived of the presented idea. JD drafted the manuscript. SHC reviewed and obtained the histological slides. YHGN, SHC and YL reviewed the manuscript drafts. All authors contributed and gave final approval to the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

References

- 1.Ling A, Foo LL, Lee E. Data from: Singapore cancer registry annual report 2018. National Registry of diseases office. Available: https://www.nrdo.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider3/default-document-library/scr-annual-report-2018.pdf?sfvrsn=bcf56c25_0 [Accessed 31 Mar 2021].

- 2.Bhurgri Y, Shaheen Y, Kayani N, et al. Incidence, trends and morphology of ovarian cancer in karachi (1995-2002). Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2011;12:1567–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kabukcuoglu F, Baksu A, Yilmaz B, et al. Malignant struma ovarii. Pathol Oncol Res 2002;8:145–7. 10.1007/BF03033726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kondi-Pafiti A, Mavrigiannaki P, Grigoriadis C, et al. Monodermal teratomas (struma ovarii). clinicopathological characteristics of 11 cases and literature review. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2011;32:657–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoo S-C, Chang K-H, Lyu M-O, et al. Clinical characteristics of struma ovarii. J Gynecol Oncol 2008;19:135–8. 10.3802/jgo.2008.19.2.135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGill JF, Sturgeon C, Angelos P. Metastatic struma ovarii treated with total thyroidectomy and radioiodine ablation. Endocr Pract 2009;15:167–73. 10.4158/EP.15.2.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marti JL, Clark VE, Harper H, et al. Optimal surgical management of well-differentiated thyroid cancer arising in struma ovarii: a series of 4 patients and a review of 53 reported cases. Thyroid 2012;22:400–6. 10.1089/thy.2011.0162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenblum NG, LiVolsi VA, Edmonds PR, et al. Malignant struma ovarii. Gynecol Oncol 1989;32:224–7. 10.1016/S0090-8258(89)80037-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volpi E, Ferrero A, Nasi PG, et al. Malignant struma ovarii: a case report of laparoscopic management. Gynecol Oncol 2003;90:191–4. 10.1016/S0090-8258(03)00142-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang X, Axiotis C. Thyroid-type carcinoma of struma ovarii. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2010;134:786–91. 10.5858/134.5.786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hatami M, Breining D, Owers RL, et al. Malignant struma ovarii--a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2008;65:104–7. 10.1159/000108654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S, Yang T, Xiang Y, et al. Clinical characteristics and survival outcomes of malignant struma ovarii confined to the ovary. BMC Cancer 2021;21:383. 10.1186/s12885-021-08118-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegel MR, Wolsky RJ, Alvarez EA, et al. Struma ovarii with atypical features and synchronous primary thyroid cancer: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2019;300:1693–707. 10.1007/s00404-019-05329-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goffredo P, Sawka AM, Pura J, et al. Malignant struma ovarii: a population-level analysis of a large series of 68 patients. Thyroid 2015;25:211–5. 10.1089/thy.2014.0328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dardik RB, Dardik M, Westra W, et al. Malignant struma ovarii: two case reports and a review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol 1999;73:447–51. 10.1006/gyno.1999.5355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roth LM, Karseladze AI. Highly differentiated follicular carcinoma arising from struma ovarii: a report of 3 cases, a review of the literature, and a reassessment of so-called peritoneal strumosis. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2008;27:213–22. 10.1097/PGP.0b013e318158e958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young RH. New and unusual aspects of ovarian germ cell tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 1993;17:1210–24. 10.1097/00000478-199312000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anagnostou E, Polymeris A, Morphopoulos G, et al. An unusual case of malignant struma ovarii causing thyrotoxicosis. Eur Thyroid J 2016;5:207–11. 10.1159/000448474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kung AW, Ma JT, Wang C, et al. Hyperthyroidism during pregnancy due to coexistence of struma ovarii and Graves' disease. Postgrad Med J 1990;66:132–3. 10.1136/pgmj.66.772.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teale E, Gouldesbrough DR, Peacey SR. Graves' disease and coexisting struma ovarii: struma expression of thyrotropin receptors and the presence of thyrotropin receptor stimulating antibodies. Thyroid 2006;16:791–3. 10.1089/thy.2006.16.791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yassa L, Sadow P, Marqusee E. Malignant struma ovarii. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2008;4:469–72. 10.1038/ncpendmet0887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeSimone CP, Lele SM, Modesitt SC. Malignant struma ovarii: a case report and analysis of cases reported in the literature with focus on survival and I131 therapy. Gynecol Oncol 2003;89:543–8. 10.1016/S0090-8258(03)00141-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shrimali RK, Shaikh G, Reed NS. Malignant struma ovarii: the West of Scotland experience and review of literature with focus on postoperative management. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2012;56:478–82. 10.1111/j.1754-9485.2012.02394.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenblum NG, LiVolsi VA, Edmonds PR, et al. Malignant struma ovarii. Gynecol Oncol 1989;32:224–7. 10.1016/S0090-8258(89)80037-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jean S, Tanyi JL, Montone K, et al. Papillary thyroid cancer arising in struma ovarii. J Obstet Gynaecol 2012;32:222–6. 10.3109/01443615.2011.645921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim D, Cho H-C, Park J-W, et al. Struma ovarii and peritoneal strumosis with thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid 2009;19:305–8. 10.1089/thy.2008.0307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robboy SJ, Shaco-Levy R, Peng RY, et al. Malignant struma ovarii: an analysis of 88 cases, including 27 with extraovarian spread. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2009;28:405–22. 10.1097/PGP.0b013e3181a27777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaco-Levy R, Bean SM, Bentley RC, et al. Natural history of biologically malignant struma ovarii: analysis of 27 cases with extraovarian spread. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2010;29:212–27. 10.1097/PGP.0b013e3181bfb133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li S, Kong S, Wang X, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic predictors in patients with malignant struma ovarii. Front Med 2021;8:774691. 10.3389/fmed.2021.774691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Filetti S, Durante C, Hartl D, et al. Thyroid cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann Oncol 2019;30:1856–83. 10.1093/annonc/mdz400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janszen EWM, van Doorn HC, Ewing PC, et al. Malignant struma ovarii: good response after thyroidectomy and I ablation therapy. Clin Med Oncol 2008;2:CMO.S410–52. 10.4137/CMO.S410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]