Abstract

A unique community of bacteria colonizes the dorsal integument of the polychaete annelid Alvinella pompejana, which inhabits the high-temperature environments of active deep-sea hydrothermal vents along the East Pacific Rise. The composition of this bacterial community was characterized in previous studies by using a 16S rRNA gene clone library and in situ hybridization with oligonucleotide probes. In the present study, a pair of PCR primers (P94-F and P93-R) were used to amplify a segment of the dissimilatory bisulfite reductase gene from DNA isolated from the community of bacteria associated with A. pompejana. The goal was to assess the presence and diversity of bacteria with the capacity to use sulfate as a terminal electron acceptor. A clone library of bisulfite reductase gene PCR products was constructed and characterized by restriction fragment and sequence analysis. Eleven clone families were identified. Two of the 11 clone families, SR1 and SR6, contained 82% of the clones. DNA sequence analysis of a clone from each family indicated that they are dissimilatory bisulfite reductase genes most similar to the dissimilatory bisulfite reductase genes of Desulfovibrio vulgaris, Desulfovibrio gigas, Desulfobacterium autotrophicum, and Desulfobacter latus. Similarities to the dissimilatory bisulfite reductases of Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii, the sulfide oxidizer Chromatium vinosum, the sulfur reducer Pyrobaculum islandicum, and the archaeal sulfate reducer Archaeoglobus fulgidus were lower. Phylogenetic analysis separated the clone families into groups that probably represent two genera of previously uncharacterized sulfate-reducing bacteria. The presence of dissimilatory bisulfite reductase genes is consistent with recent temperature and chemical measurements that documented a lack of dissolved oxygen in dwelling tubes of the worm. The diversity of dissimilatory bisulfite reductase genes in the bacterial community on the back of the worm suggests a prominent role for anaerobic sulfate-reducing bacteria in the ecology of A. pompejana.

Alvinella pompejana is a polychaete annelid that inhabits high-temperature environments of active deep-sea hydrothermal vents along the East Pacific Rise (14). Colonies of this worm and a congener, Alvinella caudata, are found on the sides of black smoker chimneys, where hydrothermal fluids emit at temperatures near 350°C. The worms live in areas of steep chemical and thermal gradients where hydrothermal fluids move through the chimney wall and mix with the surrounding seawater (15, 16), creating a temperature gradient of maximally 60°C (9). The physiological and biochemical adaptations allowing the worm to thrive under extreme conditions not normally tolerated by eukaryotes are unknown.

The worm’s dorsal integument is covered by a diverse community of bacteria dominated by conspicuous filamentous members of the epsilon group of the class Proteobacteria (8, 18). Earlier culture efforts revealed a community composed of both aerobes and facultative anaerobes (25), sulfur oxidizers, sulfate reducers, nitrifiers, nitrate respirers, denitrifiers, and nitrogen fixers. Characteristics common to many of these isolates are resistance to cadmium, zinc, arsenate, and silver and tolerance of high concentrations of copper (21).

The role of epibiotic bacterial symbionts in the ecology of the host worm is not clear. A nutritional role analogous to the symbiotic associations between chemoautotrophic bacteria and other invertebrate hosts (10, 11) has been proposed, but there is little evidence of chemoautotrophy (CO2 fixation) (2). It has also been suggested that the symbionts detoxify the worm’s immediate environment of metals and hydrogen sulfide (2).

Our primary goal is to understand the interaction between A. pompejana and its associated bacteria by identifying the abundant bacterial epibionts and their metabolic capacities. In this study, we explored the diversity of a gene involved in the anaerobic respiratory metabolism of sulfur, because the worm’s environment contains abundant sulfur and little dissolved oxygen. Dissimilatory bisulfite reductase is the terminal redox enzyme that catalyzes the reduction of sulfite to sulfide during anaerobic respiratory sulfate reduction. Prokaryotic dissimilatory bisulfite reductases have an α2β2 or α2β2γ2 structure (4, 12, 24) and possess iron-sulfur clusters and siroheme prosthetic groups. This is the key enzyme involved in sulfate respiration and was probably utilized by the common ancestors of bacteria and archaea (31).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal collection.

Specimens of A. pompejana were collected from active vent sites designated 13°N (12°48′N, 103°56′W) and 9°N (9°50′N, 104°17′W) on the East Pacific Rise at a depth of approximately 2,620 m in November of 1994 and 1995. Animals were collected by the deep-submergence vehicle Alvin and held in an insulated container which maintained the collection at <5°C until surfacing. Once on board, specimens were held at 2°C until they were sampled for bacteria and nucleic acids as described below.

DNA purification.

Bacteria were aseptically removed from the dorsal surface of freshly collected A. pompejana for DNA purification. Forceps cleaned with 70% ethanol were used to remove approximately 50-μl tufts of hair-like projections covered with bacteria. Bacteria were homogenized in 1 ml of 5 M guanidine thiocyanate–50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–25 mM EDTA–0.8% 2-mercaptoethanol. A brief centrifugation was performed to remove the bulk of the mineral grains, and the homogenates were stored at −80°C until DNA extraction was performed in the laboratory. Aliquots (100 μl) of the thawed homogenates were incubated for 1 h with 25 μl of 20% Chelex 100 (32) while being mixed on a rotating wheel. Following a brief centrifugation to remove the Chelex 100, total nucleic acids were extracted with the IsoQuick nucleic acid extraction kit (ORCA Research, Inc., Bothel, Wash.). In accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, the first extraction was performed at 65°C for 10 min, and the second extraction was done at room temperature. The nucleic acids were concentrated by isopropanol precipitation and quantified spectrophotometrically.

PCR.

Deoxyoligonucleotide primers (P94-F and P93-R) were designed by Karkhoff-Schweizer et al. (22) on the basis of nucleotide sequence similarities between the Archaeoglobus fulgidus and Desulfovibrio vulgaris dissimilatory bisulfite reductase genes. The forward primer, P94-F [5′-ATCGG(A/T)ACCTGGAAGGA(C/T)GACATCAA], and the reverse primer, P93-R [5′-GGGCACAT(G/C)GTGTAGCAGTTACCGCA], hybridized at nucleotide positions 943 to 968 and 2347 to 2372, respectively, of the dissimilatory bisulfite reductase gene of D. vulgaris (GenBank accession no. U16723). The reaction mixtures contained approximately 7 ng of template DNA per μl, 1 mM (each) the four deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dTTP, dCTP, dGTP, and dATP), 1.25 mM MgCl2, 1 μM (each) primer, and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega) in a total reaction volume of 20 μl. The thermocycling was performed by using a RoboCycler gradient 96 thermocycler (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) with thermocycling conditions including 1.5 min of denaturation at 94°C, 2.5 min of primer annealing at 60°C, and 3 min of primer extension at 72°C. This cycle was repeated 30 times. A hot start (13) was performed by warming the reaction mixtures to 95°C before adding the primers and Taq DNA polymerase.

Clone library construction and screening.

PCR products obtained from two A. pompejana specimens collected at 9°N and 13°N were cloned by using the TA cloning kit with pCR II vector (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Approximately 200 hundred recombinants were screened for full-size inserts (approximately 1.4 kb) by transferring small aliquots of cells to PCR mixtures containing the bisulfite reductase primers and thermocycling under the same conditions described above. Colonies that did not produce amplifications were eliminated from the library. The PCR products, which were all approximately 1.4 kb, were cut with the restriction endonuclease MboI. The restriction fragments were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis with 3% NuSieve (FMC, Rockland, Maine) agarose. Clones with identical restriction patterns were grouped together into clone families.

Nucleotide sequencing.

Nucleotide sequencing was performed with a Perkin-Elmer (Foster City, Calif.) ABI PRISM 310 genetic analyzer and an ABI PRISM dye termination cycle sequencing ready reaction kit with Ampli Taq DNA polymerase, FS in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Double-stranded DNA templates were prepared according to the manufacturer’s alkaline-lysis and polyethylene glycol precipitation protocols. Sequencing primers M13 forward or reverse were used to sequence in from the cloning vector depending on the orientation of the cloned PCR product. The sequencing of complementary strands was performed with primers SFITE450AR (AGGCCCTGACGCTTCATCAG) and SFITE471AR (TAACGCTCAGGAAGGTGGGC) for clone families SR1, -2, -4, -5, -7, and -8 and SR3, -6, -9, -10, and -11, respectively. These primers bind to positions 450 and 471 nucleotides into the PCR products numbered with the clone representing SR2 as a reference. Approximately 500 nucleotides were sequenced for each strand. The sequences were initially analyzed by a search of all nonredundant GenBank CDS translations, PDB, SwissProt, and PIR databases by using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) (3).

Phylogenetic analysis of nucleotide sequences.

An alignment of the deduced protein sequences of the open reading frames was made using the CLUSTAL function of Sequence Navigator version V. 1.0.1 (Perkin-Elmer) was and refined by eye. The phylogenetic analysis was performed with the SEQBOOT, PROTDIST, NEIGHBOR, and CONSENSUS programs in PHYLIP version 3.527.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Occurrence of dissimilatory bisulfite reductase genes.

We investigated the presence of dissimilatory bisulfite reductase genes in the microbial community on the dorsal surface of A. pompejana, because preliminary data suggested that this habitat is high temperature, anoxic, and rich in potential electron acceptors, e.g., sulfate (9, 17). Since the chemical and physical environment will dictate the specific physiological capability of the bacteria, it was logical to investigate genes involved in the anaerobic respiration of sulfate. We used primers previously shown to be very effective with known sulfate reducers from the genera Desulfovibrio, Desulfobulbus, and Desulfobacter (22).

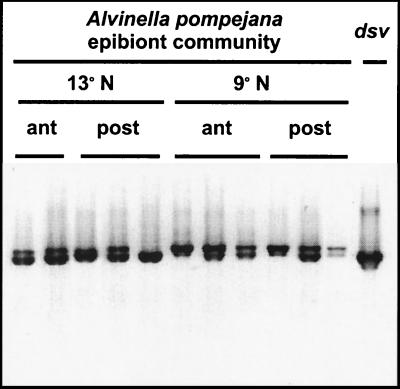

Genes encoding dissimilatory bisulfite reductase were detected in every DNA sample isolated from microbes on the dorsal surface of A. pompejana (Fig. 1). Amplifications were obtained from both the anterior and posterior dorsal surfaces of A. pompejana collected at both 13°N and 9°N on the East Pacific Rise. The amplicons were approximately the size generated in control amplifications of the dissimilatory bisulfite reductase gene of D. vulgaris (1.4 kb) (22). On agarose gels, the amplification products typically appeared as two closely spaced bands. The higher-molecular-weight band was slightly larger than the 1.4-kb amplicon produced from D. vulgaris.

FIG. 1.

Agarose gel of PCR amplification products generated by using primers (P94-F and P95-R) for dissimilatory bisulfite reductase genes. Template DNA was isolated from the epibiotic microbial community on the dorsal surface of A. pompejana (lanes 1 to 11) and from the pRKS72 plasmid that contains the dsvA and -B genes (dissimilatory bisulfite reductase of D. vulgaris) (22). A. pompejana specimens were collected from 13°N (lanes 1 to 5) and 9°N (lanes 6 to 11) of the East Pacific Rise. The microbial communities located on the anterior (ant [lanes 1 and 2 and 6 to 8]) and posterior (post [lanes 3 to 5 and 9 to 11]) of A. pompejana specimens were assayed separately. The dsv amplification product is 1.4 kb (22). The image was prepared with Adobe Photoshop.

Clone library construction and characterization.

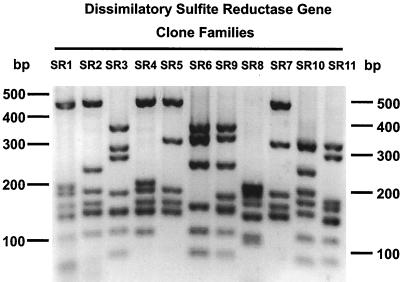

A clone library of PCR products was used to explore the diversity of dissimilatory bisulfite reductase genes of the bacteria on the dorsal surface of A. pompejana. The library consisted of clones from two PCR products enriched in the high- and low-molecular-weight bands, respectively (Fig. 1). The library contained 154 clones that were assembled into 11 clone families based on MboI restriction fragment banding patterns (Fig. 2). The library was dominated by clone families SR1 and SR6, which together accounted for 82% of the clones (Table 1). Clone families SR1 and SR6 were detected exclusively in libraries of the lower- and higher-molecular-weight PCR products, respectively. The balance of the library was composed of nine families obtained from both the high- and low-molecular-weight PCR products, which each contained 5% or fewer of the clones.

FIG. 2.

Agarose gel of the MboI restriction patterns of the 11 clone families identified in the clone library of dissimilatory bisulfite reductase gene fragments amplified from the A. pompejana epibiotic bacterial community. The image was prepared with Adobe Photoshop.

TABLE 1.

Abundance of clone families in the library of bisulfite reductase gene fragments amplified by PCR from the microbial community associated with the dorsal surface of A. pompejana

| Clone family | No. of clones | % of clones |

|---|---|---|

| SR1 | 68 | 44 |

| SR2 | 1 | 0.65 |

| SR3 | 8 | 5.2 |

| SR4 | 2 | 1.3 |

| SR5 | 8 | 5.2 |

| SR6 | 59 | 38 |

| SR7 | 4 | 2.5 |

| SR8 | 1 | 0.65 |

| SR9 | 1 | 0.65 |

| SR10 | 1 | 0.65 |

| SR11 | 1 | 0.65 |

Comparative sequence analysis of dissimilatory bisulfite reductase gene amplicons.

Comparative sequence analysis revealed high similarity between the clone families and the alpha subunits of dissimilatory bisulfite reductases. The BLASTP program (3) produced statistically significant alignments of the 11 clone families with every dissimilatory bisulfite reductase alpha subunit in the database (nonredundant GenBank CDS translations, PDB, SwissProt, SPupdate, and PIR sequences [release date 6 May 1998]). For example, alignments of clone family SR1 had the smallest sum probabilities, ranging from 2.3 × 10−58 to 8.6 × 10−4. The alignment with the D. vulgaris alpha subunit contained 85 identical amino acids out of the 112 in the alignment and had the smallest probability of occurring by chance alone. The most significant alignment with a gene other than a dissimilatory bisulfite reductase was made with the polyferredoxin gene of Methanococcus voltae (smallest sum probability, 0.022) and likely occurred by chance alone.

The similarity of the 5′ end of the amplicons with the alpha subunits of dissimilatory bisulfite reductase genes was consistent with binding of primer P94-F to a region of the operon coding for the alpha subunit in D. vulgaris and A. fulgidus (22). However, a significant alignment with the beta subunit would not have been unexpected. The genes coding for the two subunits of dissimilatory bisulfite reductase evolved by the duplication of a common ancestral gene and therefore contain segments of statistically significant nucleotide and amino acid similarity (19).

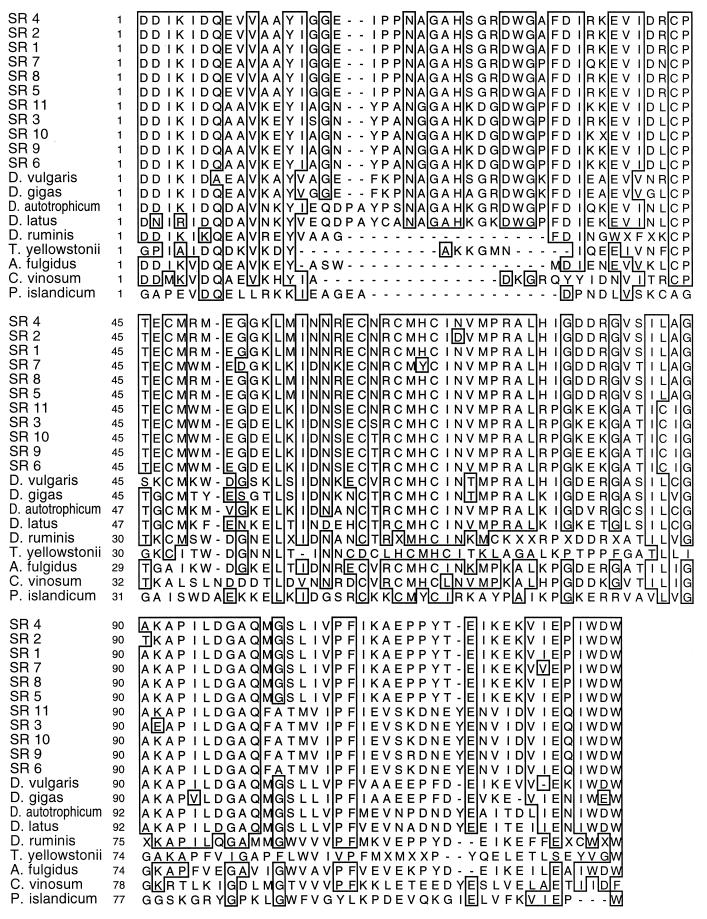

The 11 clone families were most similar to the dissimilatory bisulfite reductases of bacterial sulfate reducers. A CLUSTAL alignment of the conceptual translations of the 11 clone families with the alpha subunits of the dissimilatory bisulfite reductases of D. vulgaris, Desulfovibrio gigas, Desulfobacterium autotrophicum, Desulfobacter latus, Desulfotomaculum ruminis, Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii, Archeoglobus fulgidus, Chromatium vinosum, and Pyrobaculum islandicum contained regions of high conservation interspersed with regions of variability (Fig. 3). The similarity (percent identical aligned amino acids) between the clone families and the bacterial sulfate reducers D. vulgaris, D. gigas, D. autotrophicum, and D. latus ranged from 60.4 to 75.0%. The similarities to T. yellowstonii (thermophilic bacterial sulfate reducer), A. fulgidus (an archaeal sulfate reducer), and C. vinosum (a sulfur oxidizer) were lower (41.7 to 46.9%, 53.1 to 63.5%, and 44.8 to 47.9%, respectively). The clone families had very little similarity to an archaeal sulfur reducer, P. islandicum (25.0 to 29.2% similar).

FIG. 3.

Alignment of conceptual translations of the 11 clone families with the homologous region of the gene coding for the alpha subunit of the dissimilatory bisulfite reductases of D. vulgaris, D. gigas, Desulfobacterium autotrophicum, A. fulgidus, C. vinosum, and P. islandicum. Approximately 390 nucleotides from the 5′ end of each clone is represented. The alignment was made by using CLUSTAL. The boxes indicate identity greater than or equal to 65%, and dashes indicate gaps in the alignment.

Inspection of the alignment revealed two groups consisting of clone families SR1, SR2, SR4, SR5, and SR8 and SR3, SR6, SR9, SR10, and SR11, respectively. Similarity within these two groups ranged from 87.5 to 100%, while similarity between members of these groups ranged from 62.5 to 68.7%. Similarities within the two groups were at the high end of this range (87.5 to 100%), and similarities between members of the two groups were lower (62.5 to 68.7%). Clone families that were identical at the amino acid level were 99.1 to 100% similar at the nucleotide level. For example, clone families SR10 and SR11 had identical nucleotide sequences over 287 bases at the 5′ end of the insert, but different restriction digest patterns of these two clone families indicated sequence variation elsewhere in the gene (Fig. 2).

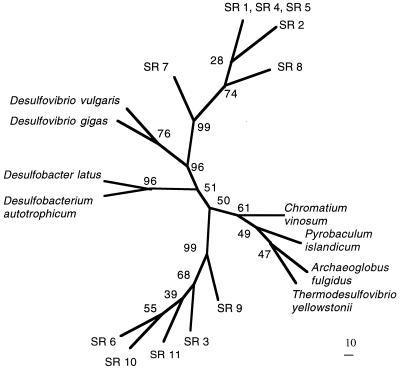

A phylogenetic tree drawn with the neighbor-joining algorithm contained two clades of bisulfite reductase clone families supported by bootstrap values of 99 that were clearly separate from previously described sulfate-reducing bacteria (Fig. 4). Two Desulfovibrio species formed another well-supported clade (bootstrap value of 76) separate from the clade containing D. latus and D. autotrophicum (bootstrap value of 96). There is probably some relationship between the similarity of dissimilatory bisulfite reductase genes and conventional taxonomic descriptors (i.e., genus, species, etc.), because there is a high degree of similarity between the evolutionary relationships inferred from 16S rRNA and dissimilatory bisulfite reductase genes (31). The two clades comprised of clone families probably represent two previously uncharacterized genera of sulfate-reducing bacteria, because similarities between these two clades (62.5 to 68.7%) were lower than the similarities between species within the genus Desulfovibrio (79.2%). Amino acid identity between sequences of the clone families and sequences reported by Wagner et al. (31) were typically less than 77%, supporting the idea that they represent previously uncharacterized sulfate-reducing bacteria. The partial sequences from these organisms were not included in the phylogenetic tree due to the small overlap with the region of the gene sequenced for the clone families. The high similarity between clone families within clades (greater than 87.5%) suggests that they are phylotypes more closely related than genera.

FIG. 4.

Dendrogram showing the relationships among the 11 clone families of dissimilatory bisulfite reductase genes and the alpha subunits of the dissimilatory bisulfite reductase genes of D. vulgarus, D. gigas, D. autotrophicum, A. fulgidus, C. vinosum, and P. islandicum. The analysis was made by using the neighbor-joining algorithm and 107 positions of aligned conceptual translations. The consensus of 100 bootstrap resamplings is shown with bootstrap values adjacent to the nodes.

The clade containing C. vinosum, P. islandicum, A. fulgidus, and T. yellowstonii was not well supported in this analysis, because the amount of variation was not suited to the great evolutionary distances separating these genera. The dissimilatory bisulfite reductases of P. islandicum, A. fulgidus, and C. vinosum are true homologs (19) and seem to have evolved from a common ancestral protein that divided into three independent lineages prior to the divergence of archaea and bacteria (23). The highly conserved siroheme-binding region of the gene that revealed this relationship is outside the portion of the gene amplified by primers P94-F and P93-R used in this study.

The primers designed by Karkhoff-Schweizer et al. (22) used in this study may have produced a conservative measure of the diversity of genes for dissimilatory bisulfite reductase, because they were designed solely with the highly conserved regions of archaeal and bacterial genes. Modified versions of these primers based on the alignment of a larger number of sequences suggested by Wagner et al. (31) might reveal equal or greater diversity. Nevertheless, the diversity of dissimilatory bisulfite reductase genes we found suggests a role for anaerobic sulfate-reducing bacteria in the ecology of A. pompejana.

Implications.

Sulfate-reducing bacteria are able to use a broad range of compounds as electron donors (6), but which ones are used by the sulfate-reducing bacteria associated with A. pompejana is not clear. Utilization of lactate and pyruvate is almost universal among the sulfate reducers (6), and many species that oxidize energy sources incompletely to excreted acetate can utilize malate, formate, and certain primary alcohols. Those capable of complete oxidation can oxidize electron donors, such as fatty acids, lactate, succinate, and benzoate. These compounds are end products of the hydrolysis and fermentation of complex polymeric compounds which are likely produced by other members of the microbial community utilizing materials produced by the worm (e.g., mucus, hair-like projections, and the dwelling tube are all likely candidates).

In addition to heterotrophic growth on the by-products of fermentation, certain sulfate-reducing bacteria are capable of autotrophic growth with CO2 as the sole carbon source, H2 as the electron donor, and sulfate as the electron acceptor. Carbon fixation by bacteria associated with Alvinella would be necessary if grazing by the worm on these bacteria is to make a net contribution to its nutrition (2). There is some evidence of bicarbonate uptake by bacteria associated with A. pompejana (1), but the low level of activity of the carbon-fixing enzyme ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase has cast doubt on the importance of autotrophy (1, 29). Nevertheless, the potential importance of autotrophy in the microbial community associated with Alvinella remains open, because autotrophic sulfate-reducing bacteria fix carbon by using the acetyl-coenzyme A pathway exclusive of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase (6).

It is unclear which bacterial morphotypes associated with the worm are sulfate reducers. Comparative sequence analysis indicated that the dominant 16S rRNA clone families are aligned with members of the epsilon group of Proteobacteria (18), and in situ hybridization revealed that these phylotypes are of the filamentous morphotype that dominates the community (8). Affiliation of the filaments with the epsilons suggests that they may not be sulfate reducers, because no cultivated members of the epsilon group of Proteobacteria are known to reduce sulfate. Sulfate-reducing bacteria come from many taxonomic groups, including the Nitrospira division, the Thermodesulfobacterium division, and the gram-positive group, and there is one archaeal representative, but most are members of the delta group of Proteobacteria (6), a group from which the epsilon subdivision was only recently separated (26). It may be possible to resolve which morphotypes are sulfate reducers without cultivation by using in situ PCR (20, 27) and fluorescence microscopy to localize dissimilatory bisulfite reductase genes within individual cells comprising the community.

There is growing evidence for interactions between bacterial and geological processes at deep-sea hydrothermal vents. The role that Alvinella spp. and their associated bacteria play in altering the growth and morphology of sulfide chimneys is not clear, but a strong influence is indicated. Where colonies of Alvinella spp. occur on the East Pacific Rise, there exist particular morphological types of chimneys known as white smokers or snowball diffusers which are colonized by the Alvinella spp. Elsewhere on the East Pacific Rise, where Alvinella spp. are absent, these chimney morphologies are absent as well, even though the chemistries of the vent fluids are similar (7, 28, 30). It has been postulated that sulfate-reducing bacteria associated with Alvinella spp. might play a role in the physical cementing of Alvinella dwelling tubes to smoker rocks (5).

Understanding the interaction between A. pompejana and its associated microbes requires identification of the abundant members of the community and the major metabolic capacities present. In this study, we established that at least two phylotypes (probably separate genera) of previously uncharacterized dissimilatory sulfate reducers are present in the community. The impact of sulfate-reducing members of the community and their interaction with the worm remain to be determined. Links with polymer-hydrolyzing and fermentative members of the community and an autotrophic role for these sulfate reducers are anticipated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the captain and crew of the Atlantis II and pilots of the deep-submergence vehicle Alvin for facilitating the collection of the samples used in this study. Gerrit Voordouw graciously provided the plasmid containing the dsv gene, and Robert Feldman provided thoughtful insight.

This research was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation to S. C. Cary (OCE-9314594 and OCE-9596082) and through a NATO Collaborative Research grant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alayse-Danet A M, Gaill F, Desbruyeres D. In situ bicarbonate uptake by bacteria-Alvinella associations. Mar Ecol. 1986;7:233–240. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alayse-Danet A M, Desbruyeres D, Gaill F. The possible nutritional or detoxification role of the epibiotic bacteria of Alvinellid polychaetes: review of current data. Symbiosis. 1987;4:51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arendsen A F, Verhagen M, Wolbert R B G, Pierik A J, Stams A J M, Jetten M S M, Hagen W R. The dissimilatory sulfite reductase from Desulfosarcina variabilis is a desulforubidin containing uncoupled metalated sirohemes and S = 9/2 iron-sulfur clusters. Biochemistry. 1993;32:10323–10330. doi: 10.1021/bi00090a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baross J A, Deming J W. The role of bacteria in the ecology of black-smoker environments. Bull Biol Soc Wash. 1985;6:355–371. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brock T D, Madigan M T. Biology of microorganisms. 6th ed. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butterfield D A, Massoth G J, McDuff R E, Lupton J E, Lilley M D. Geochemistry of hydrothermal fluids from axial seamount hydrothermal emissions study vent field, Juan-De-Fuca Ridge—subseafloor boiling and subsequent fluid-rock interaction. J Geophys Res Solid Earth and Planets. 1990;95:12895–12921. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cary S C, Cottrell M T, Stein J L, Camacho F, Desbruyeres D. Molecular identification and localization of filamentous symbiotic bacteria associated with the hydrothermal vent annelid Alvinella pompejana. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1124–1130. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1124-1130.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cary S C, Shank T, Stein J. Worms bask in extreme temperatures. Nature. 1998;391:545–546. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavanaugh C M, Gardiner S L, Jones M L, Jannasch H W, Waterbury J B. Prokaryotic cells in the hydrothermal vent tube worm Riftia pachyptila Jones—possible chemoautotrophic symbionts. Science. 1981;213:340–342. doi: 10.1126/science.213.4505.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavanaugh C M. Symbioses of chemoautotrophic bacteria and marine invertebrates from hydrothermal vents and reducing sediments. Bull Biol Soc Wash. 1985;6:373–388. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahl C, Kredich N M, Deutzmann R, Truper H G. Dissimilatory sulfite reductase from Archaeoglobus fulgidus—physicochemical properties of the enzyme and cloning, sequencing and analysis of the reductase genes. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1817–1828. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-8-1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daquila R T, Bechtel L J, Videler J A, Eron J J, Gorczyca P, Kaplan J C. Maximizing sensitivity and specificity of PCR by preamplification heating. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3749. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.13.3749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desbruyeres D, Laubier L. Alvinella pompejana gen. sp. nov., aberrant Ampharetidae from East Pacific Rise hydrothermal vents. Oceanol Acta. 1980;3:267–274. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desbruyeres D, Laubier L. Les Alvinellidae, une falle nouvelle d’annelides polychetes infeodees aux sources hydrothermales sous-marines: systematique, biologie et ecologie. Can J Zool. 1985;64:2227–2245. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desbruyeres D, Gaill F, Laubier L, Prieur D, Rau G H. Unusual nutrition of the “Pompeii worm” Alvinella pompejana (polychaetous annelid) from a hydrothermal vent environment: SEM, TEM, 13C, and 15N evidence. Mar Biol. 1983;75:201–205. [Google Scholar]

- 17.DiMeo, C. A., and S. C. Cary. Unpublished data.

- 18.Haddad A, Camacho F, Durand P, Cary S C. Phylogenetic characterization of the epibiotic bacteria associated with the hydrothermal vent polychaete Alvinella pompejana. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1679–1687. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.5.1679-1687.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hipp W M, Pott A S, Thum-Schmitz N, Faath I, Dahl C, Truper H G. Towards the phylogeny of APS reductases and sirohaem sulfite reductases in sulfate-reducing and sulfur-oxidizing prokaryotes. Microbiology. 1997;143:2891–2902. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-9-2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hodson R E, Dustman W A, Garg R P, Moran M A. In situ PCR for visualization of microscale distribution of specific genes and gene products in prokaryotic communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4074–4082. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.11.4074-4082.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeanthon C, Prieur D. Susceptibility to heavy metals and characterization of heterotrophic bacteria isolated from two hydrothermal vent polychaete annelids, Alvinella pompejana and Alvinella caudata. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3308–3314. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.11.3308-3314.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karkhoff-Schweizer R, Huber D P W, Voordouw G. Conservation of the genes for dissimilatory sulfite reductase from Desulfovibrio vulgaris and Archaeoglobus fulgidus allows their detection by PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:290–296. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.290-296.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molitor M, Dahl C, Schafer I, Speich N, Huber R, Deutzmann R, Truper H G. A dissimilatory sirohaem-sulfite-reductase-type protein from the hyperthermophilic archaeon, Pyrobaculum islandicum. Microbiology. 1998;144:529–541. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-2-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pierik A J, Duyvis M G, Vanhelvoort J, Wolbert B G, Hagen W R. The 3rd subunit of desulfoviridin-type dissimilatory sulfite reductases. Eur J Biochem. 1992;205:111–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prieur D, Chamroux S, Durand P, Erauso G, Fera P, Jeanthon C, Le Borgne L, Mevel G. Metabolic diversity in epibiotic microflora associated with the Pompeii worms Alvinella pompejana and A. caudata (Polychaetae: Annelida) from deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Mar Biol. 1990;106:361–367. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rainey F A, Toalster R, Stackebrandt E. Desulfurella acetivorans, a thermophilic, acetate-oxidizing and sulfur-reducing organism, represents a distinct lineage within the proteobacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1993;16:373–379. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tani K, Kurokawa K, Nasu M. Development of a direct in situ PCR method for detection of specific bacteria in natural environments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1536–1540. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.4.1536-1540.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tunnicliffe V, Botros M, Deburgh M E, Dinet A, Johnson H P, Juniper S K, McDuff R E. Hydrothermal vents of Explorer Ridge, Northeast Pacific. Deep-Sea Res I Oceanogr Res Pap. 1986;33:401–412. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuttle J H, Wirsen C O, Jannasch H W. Microbial activities in the emitted hydrothermal waters of the Galapagos Rift vents. Mar Biol. 1983;73:293–299. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vondamm K L, Bischoff J L. Chemistry of hydrothermal solutions from the Southern Juan-De-Fuca Ridge. J Geophys Res Solid Earth Planets. 1987;92:11334–11346. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wagner M, Roger A J, Flax J L, Brusseau G A, Stahl D A. Phylogeny of dissimilatory sulfite reductases supports an early origin of sulfate respiration. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2975–2982. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.11.2975-2982.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walsh P S, Metzger D A, Higuchi R. Chelex-100 as a medium for simple extraction of DNA for PCR-based typing from forensic material. BioTechniques. 1991;10:506–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]