Abstract

Background

COVID‐19‐associated invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) is associated with increased mortality. Cases of CAPA caused by azole‐resistant Aspergillus fumigatus strains have been reported.

Objectives

To analyse the twelve‐month CAPA prevalence in a German tertiary care hospital and to characterise clinical A. fumigatus isolates from two German hospitals by antifungal susceptibility testing and microsatellite genotyping.

Patients/Methods.

Retrospective observational study in critically ill adults from intensive care units with COVID‐19 from 17 February 2020 until 16 February 2021 and collection of A. fumigatus isolates from two German centres. EUCAST broth microdilution for four azole compounds and microsatellite PCR with nine markers were performed for each collected isolate (N = 27) and additional for three non‐COVID A. fumigatus isolates.

Results

welve‐month CAPA prevalence was 7.2% (30/414), and the rate of azole‐resistant A. fumigatus isolates from patients with CAPA was 3.7% with detection of one TR34/L98H mutation. The microsatellite analysis revealed no major clustering of the isolates. Sequential isolates mainly showed the same genotype over time.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate similar CAPA prevalence to other reports and a low azole‐resistance rate. Genotyping of A. fumigatus showed polyclonal distribution except for sequential isolates.

Keywords: Aspergillus fumigatus, azole‐resistance, CAPA prevalence, COVID‐19, COVID‐19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis, microsatellite typing

1. INTRODUCTION

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) is a severe fungal infection with a high mortality rate. 1 IPA usually occurs in severely immunocompromised patients with prolonged neutropenia 2 but also in patients on intensive care units (ICU) with viral pneumonia are more susceptible to fungal superinfections as seen in influenza‐associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA). 3 Since the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) emerged in December 2019 reports of COVID‐19‐associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) raised concerns about this superinfection as an additional contributing factor to mortality. 4 Diagnosis and management of patients with CAPA are challenging due to missing host factors and typical radiological signs; fungal diagnostic approaches are impaired by a reduced use of bronchoscopy and concurrent insufficient sensitivity of circulating galactomannan (GM) in serum [10]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to study the characteristics of this secondary mould infection. In the meantime, ECMM/ISHAM consensus criteria for defining and managing CAPA have been published. 5 According to Prattes et al. 6 CAPA, occurring with a prevalence ranging between 1.7% and26.8%, is an independent and strong predictor of ICU mortality, leading to implications for antifungal therapy as well as emergence of azole‐resistance. In IPA, patients from either the haematology ward or the ICU reveal a voriconazole‐resistance rate of Aspergillus fumigatus of more than 16% in a Dutch monocentric study 7 whereas in a retrospective study in patients with CAPA, four azole‐resistant A. fumigatus were detected (12.5%); three of which had the TR34/L98H resistance mutation in the cyp51A gene (9.4%). 8

Molecular typing methods enable strain differentiation of isolates from the same species to unveil the source of infection and potential transmission routes to characterise the epidemiology of infections. In previous studies, clonal relatedness of azole‐resistant A. fumigatus strains in patients at high risk 7 and patients with cystic fibrosis 9 could not be verified. However, this has not been investigated so far in neither IAPA nor in CAPA. The aim of our study was to assess (i) CAPA twelve‐month prevalence in critically ill ICU patients in a German tertiary care hospital, (ii) prevalence of azole‐resistant A. fumigatus isolates in CAPA patients and (iii) clonal relatedness of these A. fumigatus isolates by using microsatellite genotyping including sequential isolates.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Patient characteristics

Patient data including sex, age, outcome, microbiological results (Aspergillus culture, antifungal susceptibility tests of A. fumigatus isolates, GM from serum and respiratory specimens (Platelia Aspergillus galactomannan ELISA (Bio‐Rad Laboratories, Hercules) and Aspergillus real‐time PCR AsperGenius® (PathoNostics)) and administration of antifungals were collected. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Duisburg‐Essen (20‐9334_1‐BO). To assign patients to proven, probable or possible CAPA definition criteria from Koehler et al. 5 were used.

2.2. Twelve‐month CAPA prevalence

We calculated the twelve‐month CAPA prevalence of adult patients with COVID‐19 in the period from 17 February 2020 until 16 February 2021. Included were only patients on intensive care units (ICUs) of the University Hospital Essen except for the neurosurgery ICU. Only the first A. fumigatus positive culture or serological/molecular detection of A. fumigatus were considered. As not all diagnostic approaches (culture, GM and PCR) were performed for every patient, at least one respiratory specimen per patient was accepted to apply CAPA classification criteria. Included specimens were bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), bronchial aspirate (BS) and tracheal aspirate (TS) and sterile samples from pulmonary sites.

2.3. Collection of A. fumigatus isolates

A. fumigatus isolates were collected at the Institute of Medical Microbiology, University Hospital Essen and at the Institute of Clinical Hygiene, Medical Microbiology and Infectiology, General Hospital Nuremberg, Paracelsus Medical University, Nuremberg, both in Germany. Isolates were grown from respiratory specimens and specimens derived from pleurocentesis taken from ICU patients with molecular evidence of SARS‐CoV‐2 and corresponding disease COVID‐19. All isolates were further investigated in the Institute of Medical Microbiology, University Hospital Essen, Essen, Germany. Species identification was performed by characteristic micro‐ and macromorphological criteria. In total, 30 A. fumigatus isolates (CAPA: n = 27, non‐CAPA: n = 3) including six sequential isolates were analysed in this study. A. fumigatus ATCC 204305 and ATCC 9197 were included as quality control strains for susceptibility testing and as reference strains for mutation analysis and genotyping.

2.4. Susceptibility testing

All A. fumigatus isolates were further characterised using broth microdilution according to the EUCAST method for susceptibility testing of moulds. 10 Susceptibility was assessed for itraconazole (MedChemExpress), voriconazole (Sigma Aldrich), posaconazole (MedChemExpress) and isavuconazole (MedChemExpress). Interpretation of minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) was performed according to the clinical breakpoints for fungi of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) Version 10.0.

2.5. DNA isolation

From isolates grown on Sabouraud agar (Thermo Scientific) for 24–48 h at 35°C, two 1 cm2 agar blocks from opposing areas were punched out and lysed using Maxwell Tissue LEV Total RNA Purification Kit and Maxwell 16 instrument (both Promega Corp.).

2.6. Determination of mutations in cyp51A

Isolates with elevated MICs for at least one azole antifungal (itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole or isavuconazole) were further analysed for underlying mutations with the multiplex PCR AsperGeniusVR (PathoNostics). In a next step, the cyp51A gene was sequenced as described. 11 Sequences were then analysed using the FunResDB database 12 and matched with the non‐mutated cyp51A sequence. Amino acid substitutions were correlated with published mutations and concomitant cross‐resistance to azoles.

2.7. Microsatellite PCR

Microsatellite PCR was performed for all 32 A. fumigatus isolates as described previously by de Valk et al. 9 , 13 Nine different primers were used for the following short tandem repeats: GA, AG, CA, TCT, AAG, TAG, TTCT, CTAT and ATGT. PCR products were analysed by capillary electrophoresis using an ABI 3130 sequence analyser (Applied Biosystems), and GeneScan 1200 LIZ Dye Standard (Applied Biosystems) was used as size standard. After calculation of the fragment lengths of all nine microsatellites, Geneious 8.1.2 software was used to assign peak maxima and bin data for specific fragment lengths of microsatellite loci. Fragment length tables were exported to Microsoft Excel 2016. Hierarchical clustering with unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) and Hamming Distance was performed using PHYLOViZ 2.0 online software (https://www.phyloviz.net).

2.8. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad).

3. RESULTS

Overall, the total number of COVID‐19 cases recorded on ICU within twelve months was 414 (Table 1). Males dominated the cohort (66.4%) and median ages of all COVID‐19 cases compared to CAPA were similar (63 versus 63.5 years). Twelve‐month prevalence of CAPA was 7.2% (n = 30) with 6.3% having probable CAPA and 1.0% possible CAPA (Table 1). No case was classified as proven. Most CAPA cases were included from the second COVID‐19 wave with the beginning of September 2020 until the end of April 2021 (86.7%, 26 out of 30). Detailed diagnostic results leading to the CAPA classification according to ECMM/ISHAM per case for the twelve‐month period as well as assignment to the pandemic waves are shown in Table S1.

TABLE 1.

Twelve‐month CAPA prevalence of all COVID‐19 cases on ICU at the University Hospital Essen

| n (%) | Male (%) | Female (%) | Age in years; median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of COVID‐19 cases | 414 | 275 (66.4) | 139 (33.6) | 63 (53−74) |

| CAPA | 30 (7.2) | 23 (8.3) | 7 (0.5) | 63.5 (56–68) |

| Proven | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.a. |

| Probable | 26 (86.7) | 20 (7.2) | 6 (4.3) | 63.5 (55–68) |

| Possible | 4 (13.3) | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.7) | 63.5 (61–69) |

| Aspergillus fumigatus PCR positive a | 9 (30) | |||

| Aspergillus Galactomannan positive b | 23 (76.7) | |||

| Aspergillus fumigatus culture positive c | 16 (53.3) | |||

| Azole‐resistant Aspergillus fumigatus | 0 |

From BAL (n = 8) and bronchial aspirate (n = 1).

From BAL (n = 23).

From BAL (n = 13), bronchial aspirate (n = 2) and tracheal aspirate (n = 2).

In 16 (53%) cases, A. fumigatus could be isolated from respiratory specimen. Among the diagnostic procedures for CAPA definition, GM from respiratory specimen was positive in 77% followed by Aspergillus culture (57%) and PCR (30%). The GM median (IQR) was index 3.5 (2.1 ‐ 5.5), and PCR median (IQR) had a ct‐value of 32.0 (29.1 ‐ 35.3) for A. fumigatus and 27.7 (26.6 ‐ 29.9) for Aspergillus species. Within the observed period, no azole‐resistant A. fumigatus was found.

Next, antifungal susceptibility testing and further molecular analysis were performed for the collected A. fumigatus isolates. Patients` details are shown in Table 2. In total, 27 A. fumigatus isolates were derived from patients with COVID‐19 and three negative controls from patients without COVID‐19 were included. Of these CAPA isolates, two sequential isolates belonging to the same patient originate from Essen and four sequential isolates from two patients from Nuremberg. All samples except for two were taken in the second pandemic wave. Patients with COVID‐19 were mostly male (16 out of 21) and had a median age of 64 years. In total, 15 ICU patients with COVID‐19 died (62%). Antifungal treatment was administered in 75% of COVID‐19 cases. Voriconazole (67%) and isavuconazole (13) were the most frequently used antifungal drugs in the COVID‐19 cohort. For one patient with COVID‐19, information on antifungal treatment was not available.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of patients and corresponding A. fumigatus isolates used for further studies on phenotypic and molecular antifungal susceptibility as well as genotyping analysis

| Isolate | Source | COVID‐19 | Center | Sex | Age (years) | Outcome | Antifungal prophylaxis/treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC 204305 | No | Na | Na | Na | Na | Na |

| 2 | Patient isolate | No | Essen | Male | 51 | Died | Voriconazole |

| 3 | Patient isolate | Yes | Essen | Male | 74 | Died | Voriconazole |

| 4 | Patient isolate | Yes | Essen | Male | 57 | Died | Voriconazole |

| 5 | Patient isolate | Yes | Essen | Male | 48 | Died | Voriconazole |

| 6 | Patient isolate | Yes | Essen | Male | 47 | Died | None |

| 7 | Patient isolate | Yes | Essen | Male | 66 | Died | None |

| 8 | Patient isolate | Yes | Essen | Male | 70 | Discharged | Voriconazole |

| 9 | Patient isolate | No | Essen | Male | 78 | Died | Voriconazole |

| 10 | Patient isolate, sequential isolate of no. 6 | Yes | Essen | Male | 47 | Died | None |

| 11 | Patient isolate | Yes | Essen | Male | 54 | Discharged | None |

| 12 | Patient isolate | No | Essen | Male | 78 | Died | None |

| 13 | Patient isolate | Yes | Essen | Male | 64 | Died | Voriconazole first, then amphotericin b |

| 14 | Patient isolate | Yes | Essen | Female | 62 | Transferred | None |

| 15 | Patient isolate | Yes | Essen | Male | 69 | Died | Voriconazole |

| 16 | Patient isolate | Yes | Essen | Male | 81 | Died | Voriconazole |

| 17 | Patient isolate | Yes | Essen | Male | 57 | Died | Voriconazole |

| 18 | Patient isolate | Yes | Essen | Male | 58 | Died | None |

| 19 | Patient isolate | Yes | Essen | Female | 63 | In‐patient | Voriconazole |

| 20 | Patient isolate | Yes | Essen | Male | 54 | In‐patient | Voriconazole |

| 21 | Patient isolate | Yes | Essen | Male | 79 | Died | Posaconazole |

| 22 | Patient isolate, sequential isolate of no. 21 | Yes | Essen | Male | 79 | Died | Posaconazole |

| 23 | Patient isolate | Yes | Essen | Female | 52 | Transferred | Voriconazole |

| 24 | Patient isolate | Yes | Nuremberg | Male | 81 | Discharged | Isavuconazole |

| 25 | Patient isolate | Yes | Nuremberg | Female | 83 | Died | Isavuconazole |

| 26 | Patient isolate | Yes | Nuremberg | Female | 64 | Discharged | Isavuconazole first, then amphotericin b |

| 27 | Patient isolate, sequential isolate of no. 25 | Yes | Nuremberg | Female | 83 | Died | Isavuconazole |

| 28 | Patient isolate, sequential isolate of no. 26 | Yes | Nuremberg | Female | 64 | Discharged | Isavuconazole first, then amphotericin b |

| 29 | Patient isolate | Yes | Nuremberg | Male | 67 | Died | Na |

| 30 | Patient isolate, sequential isolate of no. 29 | Yes | Nuremberg | Male | 67 | Died | Na |

| 31 | Patient isolate, sequential isolate of no. 24 | Yes | Nuremberg | Male | 81 | Discharged | Isavuconazole |

| 32 | Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC 9197 | No | Na | Na | Na | Na | Na |

The antifungal susceptibility testing results (MIC range, MIC50 and MIC90) for the triazole agents itraconazole, posaconazole, voriconazole and isavuconazole against the 30 A. fumigatus isolates were as follows: The MIC ranges for itraconazole, posaconazole, voriconazole and isavuconazole were 0.25 – >8 µg/ml, 0.06 ‐ >8 µg/ml, 0.25 ‐ 8 µg/ml and 0.5 ‐ 4 µg/ml respectively. Voriconazole and isavuconazole had the same MIC50 of 1 µg/ml, whereas posaconazole had the lowest MIC50 with 0.1875 µg/ml followed by itraconazole (0.5 µg/ml). Results for MIC90 were similar with voriconazole and isavuconazole having the highest values with 2 µg/ml. The lowest MIC90 was determined for posaconazole (0.25 µg/ml) and itraconazole achieved a MIC90 of 1 µg/ml.

Overall, ten A. fumigatus strains exhibited elevated MICs for itraconazole, voriconazole or posaconazole and were further analysed for mutations (Table 3). A single mutation was found with both approaches, the AsperGenius® PCR and cyp51A gene sequencing, in isolate number 14 from a COVID‐19 patient (TR34/L98H alteration). However, two additional mutations were found by sequencing in isolates 2 (G54R) and 3 (F46Y, M172V and E427K). Eight of the ten A. fumigatus isolates depicted in Table 3 were derived from patients with COVID‐19 (isolates 3, 8, 10, 14, 17, 26, 29 and 30). As shown, mutations come along with increased MICs of azole compounds. No mutation corresponding with azole‐resistance was found in the A. fumigatus isolates derived from the centre in Nuremberg.

TABLE 3.

Detection of mutations in cyp51A by AsperGenius® PCR (three most common mutations) and by cyp51A gene sequencing

| Isolate | AsperGenius® | cyp51A mutation | Azole compound MIC (µg/ml) | COVID‐19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Negative | G54R | ITC and POS >8 | No |

| 3 | Negative | F46Y, M172V, E427K | ITC = 1.5 | Yes |

| 8 | Negative | Negative | POS = 0.25 | Yes |

| 9 | Negative | Negative | POS = 0.25 and VRZ = 2 | No |

| 10 | Negative | Negative | POS = 0.25 and VRZ = 2 | Yes |

| 14 | Tr34/l98h | L98H | VRZ = 8, ITC >8, POS = 1 and ISC = 4 | Yes |

| 17 | Negative | Negative | VRZ = 2 and ISC = 2 | Yes |

| 26 | Negative | Negative | POS = 0.25 | Yes |

| 29 | Negative | Negative | POS = 2 and ISC = 2 | Yes |

| 30 | Negative | Negative | POS = 0.5, VRZ = 4 and ISC = 2 | Yes |

Abbreviations: ISC, isavuconazole; ITC, itraconazole; POS, posaconazole; VRZ, voriconazole.

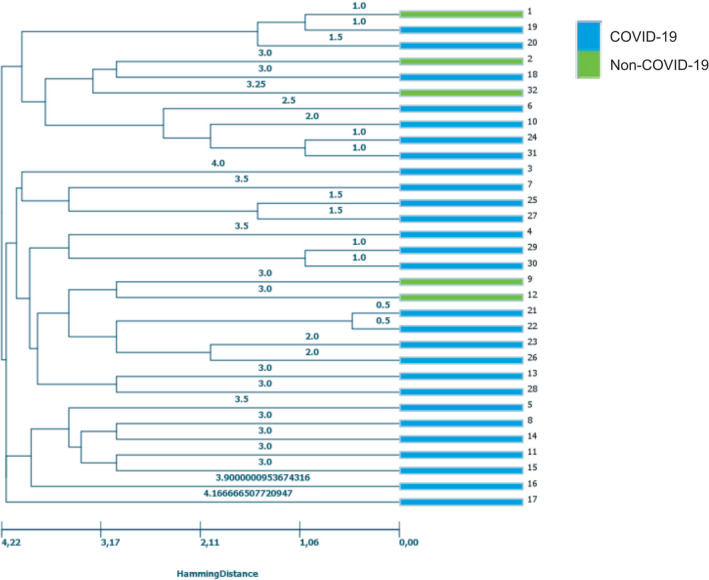

Next, to analyse molecular relationships, microsatellite typing was performed. The microsatellite derived clustering of all isolates from patients with and without COVID‐19 is summarised in Figure 1. Assignment to the centre of origin or to CAPA classification by genotyping was not successful (data not shown). We also checked for clonal relatedness of isolates from patients with fatal outcome and survival but there was no clustering of isolates from patients who died versus patients who survived (and also not for discharged/transferred patients or in‐patients) (data not shown). Most of the detected genotypes showed a polyclonal distribution except for the sequential isolates 24/31, 25/27 and 29/30.

FIGURE 1.

Genetic relatedness of A. fumigatus isolates from patients with (blue) and without (green) underlying COVID‐19 disease originating from the two centres Essen and Nuremberg based on microsatellite typing. The dendrogram was constructed based on UPGMA clustering of nine microsatellite markers

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we found a CAPA prevalence of 7.2% in 414 ICU COVID‐19 patients from a German university hospital. Reports on CAPA prevalence around the world range from 3.8% 14 up to 40%. 15 In a recent multi‐centre study, Prattes et al. 6 observed a CAPA prevalence of 15.4% on ICUs in 20 centres from nine countries with regional variation. These variations may be due to local epidemiological variations, different burden of Aspergillus exposure, diagnostic accuracy and genetic predisposing risk factors. Case series from Cologne, Germany, reported CAPA in 26.3% of ICU patients 16 and therefore in higher rates compared to our findings with 7.2%. Due to their use of the modified AspICU algorithm 17 for classification, comparison is difficult. The difference in prevalence might be attributable to patients’ demographics, host factors and different treatment strategies. In comparison with a recent study from the Netherlands, 18 our data revealed lower rates for proven (0% vs. 2%) and probable CAPA (6.3% vs. 12%) but not for possible CAPA (1% vs. 1%).

Interestingly, in most of the CAPA cases, GM from respiratory specimen was positive (77%) followed by culture (57%) and PCR (30%). These findings correspond to the multi‐national study of Janssen et al. 18 with 78% positivity for GM, 42% Aspergillus culture and only 17% PCR. Antifungal therapy or prophylaxis did not influence PCR results and therefore should not be the reason for the low positivity rate. 19 Within the study period, neither other Aspergillus species than A. fumigatus nor Mucorales were detected by culture or PCR from patients with CAPA. Delineating differences regarding separate COVID‐19 waves was not possible because most of the cases were derived from the second wave. This might be due to higher awareness of CAPA within the course of the pandemic leading to increased sampling and microbiological diagnostics. Therefore, the prevalence is probably underestimated.

Mutation analysis showed that one isolate (number 14) exhibited a TR34/L98H alteration and one (number 3) multiple mutations (F46Y, M172V and E427K). TR34/L98H is an environmentally occurring resistance mutation and is widespread across multiple continents. Multiple mutations have been reported worldwide with only moderate elevated azole MICs not considered azole‐resistant. 20 This resulted in a low proportion of azole‐resistant A. fumigatus isolates from patients with COVID‐19 (3.7%). Further, the G54R mutation in isolate 2 derived from a non‐COVID‐19 patient is described as being associated with long‐term azole therapy but also with long‐term exposure of A. fumigatus to fungicides in the environment. 21 , 22 The patients’ isolates for whom mutations were identified, received no azole prophylaxis/treatment (isolate number 14), voriconazole for treatment (isolate number 3) and azole prophylaxis/ voriconazole treatment (isolate number 2). In a retrospective analysis using clinical data of patients worldwide who received a CAPA diagnosis, 4 azole‐resistant A. fumigatus were detected (12.5%); three of which had the TR34/L98H resistance mutation (9.4%). From these, two patients had a possible previous exposure to triazoles. 8 Similarly, Meijer and colleagues assessed 15% (n = 2/13) azole‐resistant A. fumigatus isolates harbouring the TR34/L98H mutation found in CAPA in the Netherlands, a bordering country of Germany. 23 Both countries are known to use high amounts of azole fungicide per hectare of agricultural land, 24 and according to a dutch survey of invasive aspergillosis, azole‐resistance rates were reported to be up to 30% on high‐risk wards. 25

Another important aim of the study was to gain information about the relatedness of CAPA isolates. Therefore, we applied microsatellite genotyping, a well‐established molecular approach with high discriminatory power. 13 Microsatellite typing showed polyclonality of strains. It further revealed no major clustering neither regarding isolates from patients with or without COVID‐19, nor the centre of origin, nor regarding CAPA classification. However, some, but not all sequential isolates seem to be related to each other. Why isolates 26 and 28 are not closely related as the other sequential isolates can only be assumed. In comparison with the other pairs of first and sequential isolates, pair 26/28 had the longest interval between sampling (five days). Possibly, the patient was infected with two distinct A. fumigatus genotypes.

To the best of our knowledge, no comparable genotyping data are available neither for IAPA, nor for CAPA. Steenwyk et al. 26 found that CAPA isolate genomes do not exhibit significant differences from the genome of a reference strain by using genome sequencing of four A. fumigatus strains. Additionally, all four CAPA isolates cluster together, which may be due to the fact they were all from the same geographic area. However, our findings, based on 27 isolates from patients with CAPA from two centres, showed no epidemiological association of isolates in terms of origin and underlying disease.

In the past, several approaches were used for genotyping A. fumigatus. With microsatellite and cyp51A sequence typing, Fuhren et al analysed the putative clonality of azole‐resistant A. fumigatus strains from high‐risk patients from either the haematology ward or the ICU and found no clonal spread of resistant strains [7]. Also more recently, a new genotyping method based on hypervariable tandem repeats within exons of surface protein‐coding genes was established by Garcia‐Rubio et al have been developed which is highly discriminatory and easy to perform [23].

In summary, we found a CAPA twelve‐month prevalence of 7.2% which is in line with other reports. Within our collection of A. fumigatus isolates derived from patients with CAPA, the proportion of azole‐resistant A. fumigatus isolates was low (1/27; 3.7%). Genotyping showed no clonal spread of A. fumigatus patient isolates.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Lisa Kirchhoff: Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (lead); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Supervision (equal); Writing – original draft (equal). Lukas Miles Braun: Data curation (supporting); Formal analysis (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Visualization (equal). Dirk Schmidt: Formal analysis (equal); Methodology (equal). Silke Dittmer: Formal analysis (equal); Investigation (supporting); Methodology (supporting). Jutta Dedy: Resources (equal). Frank Herbstreit: Resources (equal). Raphael Stauf: Software (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). Nina Kristin Steckel: Resources (equal). Jan Buer: Resources (equal); Writing – review & editing (supporting). Peter‐Michael Rath: Data curation (equal); Methodology (supporting); Writing – review & editing (equal). Jörg Steinmann: Data curation (equal); Methodology (equal); Writing – original draft (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). Hedda Luise Verhasselt: Conceptualization (lead); Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Supervision (equal); Writing – original draft (lead); Writing – review & editing (equal).

Supporting information

Table S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Open access funding enabled and organized by ProjektDEAL.

Kirchhoff L, Braun LM, Schmidt D, et al. COVID‐19‐associated pulmonary aspergillosis in ICU patients in a German reference centre: Phenotypic and molecular characterisation of Aspergillus fumigatus isolates. Mycoses. 2022;65:458–465. doi: 10.1111/myc.13430

Presented in part at the 55th Scientific Conference of the German speaking Mycological Society (DMykG) e. V., 27‐29 September 2021. Poster PIII‐01.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NA, Levitz SM, Netea MG, White TC. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(165):165rv113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lin SJ, Schranz J, Teutsch SM. Aspergillosis Case‐fatality rate: systematic review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(3):358‐366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van de Veerdonk FL, Kolwijck E, Lestrade PP, et al. Influenza‐associated aspergillosis in critically Ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(4):524‐527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single‐centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):475‐481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koehler P, Bassetti M, Chakrabarti A, et al. Defining and managing COVID‐19‐associated pulmonary aspergillosis: the 2020 ECMM/ISHAM consensus criteria for research and clinical guidance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(6):e149‐e162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prattes J, Wauters J, Giacobbe DR, et al. Risk factors and outcome of pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill coronavirus disease 2019 patients‐a multinational observational study by the European Confederation of Medical Mycology. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;S1198‐743X(21):00474‐2. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.08.014. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fuhren J, Voskuil WS, Boel CH, et al. High prevalence of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates from high‐risk patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(10):2894‐2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Salmanton‐García J, Sprute R, Stemler J, et al. COVID‐19‐associated pulmonary aspergillosis, March‐August 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(4):1077‐1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Seufert R, Sedlacek L, Kahl B, et al. Prevalence and characterization of azole‐resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in patients with cystic fibrosis: a prospective multicentre study in Germany. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(8):2047‐2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing . Clinical breakpoints for fungi v. 332 10.0. 2020. AFST_BP_v10.0_200204_updatd_links_200924.pdf. Accessed 20.11.2021, 2021.

- 11. Chen J, Li H, Li R, Bu D, Wan Z. Mutations in the cyp51A gene and susceptibility to itraconazole in Aspergillus fumigatus serially isolated from a patient with lung aspergilloma. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55(1):31‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weber M, Schaer J, Walther G, et al. FunResDB‐A web resource for genotypic susceptibility testing of Aspergillus fumigatus. Med Mycol. 2018;56(1):117‐120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Valk HA, Meis JF, Curfs IM, Muehlethaler K, Mouton JW, Klaassen CH. Use of a novel panel of nine short tandem repeats for exact and high‐resolution fingerprinting of Aspergillus fumigatus isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(8):4112‐4120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lamoth F, Glampedakis E, Boillat‐Blanco N, Oddo M, Pagani JL. Incidence of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis among critically ill COVID‐19 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(12):1706‐1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nasir N, Farooqi J, Mahmood SF, Jabeen K. COVID‐19‐Associated Pulmonary Aspergillosis (CAPA) in patients admitted with severe COVID‐19 pneumonia: an observational study from Pakistan. Mycoses. 2020;63(8):766‐770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koehler P, Cornely OA, Böttiger BW, et al. COVID‐19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses. 2020;63(6):528‐534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Blot SI, Taccone FS, Van den Abeele AM, et al. A clinical algorithm to diagnose invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(1):56‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Janssen NAF, Nyga R, Vanderbeke L, et al. Multinational observational cohort study of COVID‐19‐associated pulmonary aspergillosis(1). Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(11):2892‐2898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Scharmann U, Kirchhoff L, Hain A, et al. Evaluation of three commercial PCR assays for the detection of azole‐resistant aspergillus fumigatus from respiratory samples of immunocompromised patients. J Fungi (Basel). 2021;7(2):132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Garcia‐Rubio R, Alcazar‐Fuoli L, Monteiro MC, et al. Insight into the significance of Aspergillus fumigatus cyp51A polymorphisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(6):e00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Riat A, Plojoux J, Gindro K, Schrenzel J, Sanglard D. Azole resistance of environmental and clinical aspergillus fumigatus isolates from Switzerland. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(4):e02088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sharma C, Hagen F, Moroti R, Meis JF, Chowdhary A. Triazole‐resistant Aspergillus fumigatus harbouring G54 mutation: Is it de novo or environmentally acquired? J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2015;3(2):69‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meijer EFJ, Dofferhoff ASM, Hoiting O, Meis JF. COVID‐19‐associated pulmonary aspergillosis: a prospective single‐center dual case series. Mycoses. 2021;64(4):457‐464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Burks C, Darby A, Gómez Londoño L, Momany M, Brewer MT. Azole‐resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in the environment: identifying key reservoirs and hotspots of antifungal resistance. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17(7):e1009711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lestrade PP, Meis JF, Arends JP, et al. Diagnosis and management of aspergillosis in the Netherlands: a national survey. Mycoses. 2016;59(2):101‐107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Steenwyk JL, Mead ME, de Castro PA, et al. Genomic and phenotypic analysis of COVID‐19‐associated pulmonary aspergillosis isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus. Microbiol Spectr. 2021;9(1):e0001021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1