Abstract

This study conducted a content analysis of 639 news articles about e-cigarettes in China from 2004–2019 to examine longitudinal changes in media frames and media tones about e-cigarettes in Chinese newspapers. Results indicated that policy frame was the most frequently used frame, followed by human impact frame, information frame, and uncertainty frame. Dividing the time period of 2004–2019 into four phases (i.e., 2004–2006, 2007–2010, 2011–2017 and 2018–2019), the study found that the frequency of the information frame significantly decreased over time, while the policy frame and uncertainty frame significantly increased, with the policy frame being the dominant frame in recent years. In contrast, the use of the economic frame and morality frame fluctuated, both reaching peaks in the phase of 2007–2010 and decreasing in the most recent phase. Overall, the tone of the large majority of news articles was unfavorable, and the turning point occurred in the phase of 2007–2010 when the percentage of news articles with negative tone exceeded those with positive tone for the first time. Framing of e-cigarette news articles in China demonstrated the pivotal role of policy makers in defining the e-cigarette issue, and the influence of the international public health community, as an important and reliable information source, on defining the health risk of e-cigarettes, which has implication for not only e-cigarette control, but tobacco control in China in general.

Introduction

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), which are also known as electronic nicotine delivery system (ENDS) have achieved global widespread visibility and popularity. The global ENDS market was valued at $11.5 billion in 2018 and is anticipated to register a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 21.6% during 2019–24 [1]. However, e-cigarettes are controversial products that some have promoted as a less harmful alternative to combustible tobacco or as a smoking cessation tool [2], while others have raised concerns about evidence of health harms of use, and youth adoption with negative impacts on adolescents’ brain development or progression to smoking initiation [3, 4]. Despite the controversy, e-cigarettes are getting more and more popular around the world.

China is the largest e-cigarette manufacturer in the world, producing 95% of the world’s e-cigarettes [5]. Though the prevalence of e-cigarette use in China is lower than many high-income countries, China is ‘a prime contender’ to become the largest consumer market of e-cigarettes [6]. The International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project surveys in China in 2010, 2012 and 2015 found that among current and former smokers in urban areas, there was a marked increase in awareness of e-cigarettes over time, an upward trend in experimentation with e-cigarettes, and a 5-fold increase in e-cigarette trial (from 2% at Wave 3 to 11% at Wave 5) [7]. Diffusion of innovation theory posits that mass media plays an important role in shaping awareness and perception of innovations [8]. Yates et al.s’ [9] study further demonstrated the importance of news influencing perceptions about the risks of using e-cigarettes. This may be particularly salient in China, where e-cigarettes are not clearly defined or well-regulated products: they are neither classified as tobacco nor drugs. Therefore, media portrayals of e-cigarettes are likely to have a substantial impact on the public’s awareness of, perception of, attitude toward and behaviors related to e-cigarettes.

Frames are powerful mechanisms to define problems and shape public opinion [10] and are especially powerful for analyzing media coverage on public policy issues [11]. However, perhaps due to the relatively recent introduction of e-cigarettes into the public sphere, frame analysis of media coverage on e-cigarettes in China is scant. Based on previous literature on frame analyses and studies on media representation of e-cigarettes in other countries [9, 12–14], this study identified frames that Chinese media have used to report on e-cigarettes since 2004 (when the first media report on e-cigarettes appeared in China) and described how these media frames changed over time. Through discussion of why different media frames and tones on e-cigarettes emerged and changed over each time period, this study sheds light on the various forces shaping the e-cigarette issue and media representation in China and further has implications for both e-cigarette control efforts and tobacco control in general in China.

Frame analysis in media coverage

Goffman [15] has defined a frame as a ‘schemata of interpretation’ through which individuals organize and make sense of information or occurrences. A frame is also considered as a story line or organizing idea that provides meaning [16, 17]. The frames used in media stories help define problems and call attention to some aspects of an event or issue while obscuring others [18]. Due to the news media’s function presenting messages to the public and its crucial role in shaping the public perceptions, a considerable number of frame analyses have focused on news frames. However, despite a large body of research on media frames, one problem frequently associated with frame research has been inconsistencies in the conceptualization of media frames [19]. In an effort to address this problem, scholars have categorized news frames into two major types: issue-specific frames and generic frames [20, 21]. While issue-specific frames are specific to a topic or event, allowing ‘great specificity and detail’, generic frames are applicable to a wide range of topics, and could be used to compare framing practices in different cultures [22]. Researchers have identified various issue-specific frames and generic frames [21, 23, 24]. Among them, Neuman, Just and Crigler’s five frames (i.e. economy, conflict, powerlessness, human impact and morality) have been widely used and have become the foundation for other popular frame typologies, such as Semetko and Valkenburg’s five generic frames (i.e. economic consequences, conflict, attribution of responsibility, human interest and morality) [21, 25].

Though generic frames provide a systematic platform to examine news frames across issues and topics, they do not pertain to a specific topic in a specific context. To solve this problem, some scholars have begun to combine generic frames and issue-specific frames when conducting frame analyses. For example, in a study on media coverage of stem cell research, Nisbet et al. [26] used both generic frames and two issue-specific frames: policy background and scientific background. Similarly, Dimitrova et al. [27] also combined generic frames with two issue specific frames: prediction frame and information frame. In the current study, we followed a similar strategy, using both generic and issue-specific frames to examine the media coverage of e-cigarettes in China. First, we identified a list of generic frames that are most applicable to the current study. Then we added two issue-specific frames based on the content of the media coverage included in the study. By doing so, the frames examined in this study capture both general and specific concepts.

Cigarette and e-cigarette control policy change in China

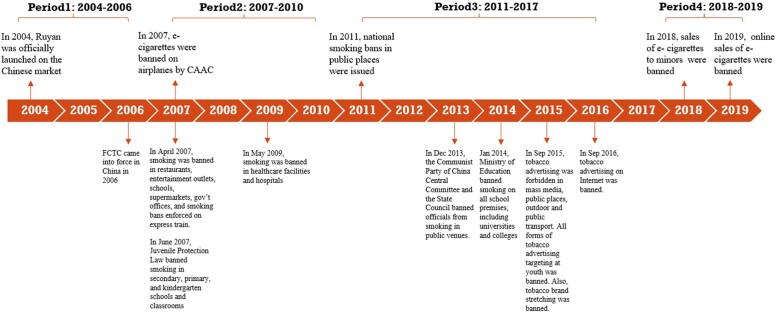

Traditionally, media in China was tightly controlled by the government and was considered the mouthpiece of the Communist Party of China (CPC) [28]. Though after media marketization since the early 1980s [29], the Chinese media has gradually gained more freedom, the CPC has continued to exert considerable control over both the programming and content of the media via the Central Propaganda Department and its local branches [30, 31], and Chinese media’s coverage of important issues was still highly consistent with the government’s policies [32]. Therefore, to explore the media frames on the issue of e-cigarettes, it is essential to know how tobacco control policies in general and policies on e-cigarettes specifically have changed in China. A review of the relevant policies during the past 16 years (Fig. 1) shows a gradual increase of tobacco control and e-cigarette regulation over time. When Ruyan, the first e-cigarette brand in China, was launched in the Chinese market in 2004, according to the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Tobacco Monopoly, Ruyan, as an unprecedented product, was not a tobacco product and therefore not in the regulatory scope of either the tobacco monopoly law or the State Food and Drug Administration [33]. Therefore, e-cigarettes enjoyed a significant period of development without regulation. A significant advance in China’s tobacco control was signing the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) treaty, which came into legal force in China in 2006. WHO FCTC was developed in response to the globalization of the tobacco epidemic. As a signatory, China is obligated to implement effective tobacco control measures; an increasing number of clean air policies focused on different places and groups have been issued since 2007, reaching a peak in 2011, when the first comprehensive national smoke-free law was released. In March 2011, the Ministry of Health of China (MHC) issued a set of rules stipulating that smoking in all public spaces nationwide is forbidden [34]. In addition, to implement Article 13 of the FCTC, restrictions on cigarette advertising and tobacco brand sharing/stretching activities were gradually enforced [35, 36]. Regarding e-cigarettes, the first regulation about e-cigarettes in China was the Civil Aviation Association of China’s (CAAC) prohibition of e-cigarette use on all aircraft in 2007 [37]. However, following this action, no additional e-cigarette polices were issued for over a decade. In 2018, the sale of electronic cigarettes to minors was banned; and in 2019, a new policy urged the producers and sellers of electronic cigarettes to shut down websites and other online portals and suspend related advertising [38].

Fig. 1.

Timeline of cigarette and e-cigarette policy changes in China developed based on ITC China’s Timeline of Tobacco Control Policies and ITC Surveys (CN) [52].

A review of the tobacco control and e-cigarettes policies in China during the past 16 years (Fig. 1) highlighted three significant events: in 2007, the first regulation on e-cigarettes was issued; in 2011, the first nationwide smoking ban in public places was released, and in 2018, regulation on e-cigarettes re-emerged after an eleven-year absence. Accordingly, we divided the 16 years into four periods: 2004–6, 2007–10, 2011–17 and 2018–19. The first two research questions are

RQ1: What frames were used in Chinese press reports on e-cigarettes, from 2004 to 2019?

RQ2: How did the media frames of e-cigarettes evolve in Chinese newspapers over the four phases, i.e. 2004–6, 2007–10, 2011–17 and 2018–19?

In addition to frames, media tone is another crucial issue in the content of media coverage [39]. In studies based on media texts, scholars examining media tone in e-cigarette coverage have had mixed findings in different countries: while the tone of media stories was largely unfavorable in South Korea [12], Rooke and Amos [14] concluded that the overall tone of media reports in the UK and Scottish newspapers was favorable, though most stories included both positive and negative aspects of e-cigarette use. To examine the tone of the Chinese media coverage on e-cigarettes, we put forth the following questions:

RQ3: What was the media tone about e-cigarettes in China in the period of 2004–19?

RQ4: How did the media tone about e-cigarettes evolve in China over the four phases, i.e. 2004–6, 2007–10, 2011–17 and 2018–19?

Methods

Data

This study used content analysis to examine news frames, focusing on newspaper coverage of e-cigarettes in mainland China from 1 January 2004, the year when e-cigarettes were reported for the first time, to 31 July 2019 when the study started. A search was conducted in the ‘Wisenews’ database using key words ‘Dian Zi Xiang Yan’ and ‘Dian Zi Yan’ (Chinese translations of e-cigarettes), limiting results to only mainland Chinese newspapers. WiseNews is a full-text news database providing access to >600 newspapers, magazines and websites from China, Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan as well as some regional newspapers from the US, and it is widely accepted as a valid database to examine Chinese media coverage [40, 41]. The keyword searches yielded a total of 1266 articles about e-cigarettes.

News articles were screened to eliminate articles where e-cigarettes were mentioned in passing but not the focus of the report, which eliminated 547 (43.2%) of articles. During the full-text coding process, 80 duplicates and unrelated stories were eliminated. The remaining 639 news articles were included in the analysis.

Coding procedure

Coding was conducted from August to October 2019. The full text of each article was examined for coding. Images and videos were not included in the analysis. We used a combination of deductive and inductive approaches to identify frames. Based on previous literature and a pilot examination of a sample of news articles, we identified five generic frames: human impact, conflict, morality, economic frame [25] and policy frame [26]. We developed two additional issue specific frames while coding a test set of 60 articles to develop the code book and to train the two coders. The ‘uncertainty frame’, adapted from Shehata and Hopmann’s [42] scientific-uncertainty frame, which claims that existing research is inconclusive when it comes to the causes and consequences of a scientific issue and more research is needed before any actions are taken. e-Cigarette articles expressed uncertainty regarding not only e-cigarette health impact but also on what constitutes an e-cigarette, Chinese policy on e-cigarettes and e-cigarette economic prospects. Thus, our ‘uncertainty frame’ includes all the uncertainty surrounding e-cigarettes. The ‘information frame’ refers to basic information about e-cigarettes, including their features and function, which was a common component of stories about this new product.

The code book was revised multiple times during pilot coding before the final version was completed. Coders chose one core frame for each of the articles based on the major frame found in the title and the lead. Because the headline and lead paragraph set the tone for reading the article, each headline and lead was examined for one of the following frames:

Human impact referred to an emphasis on fact-based outcomes with respect to human being because of using e-cigarettes.

Policy frame referred to legalization of e-cigarettes or policies about e-cigarettes.

Economic frame focused on profit and loss of e-cigarette businesses and the wider values of the capitalism culture.

Morality frame put the event, problem or issue in the context of morals, social prescriptions and religious tenets.

Conflict frame emphasized the expression of the conflict of interest, goals and values between individuals, groups or institutions.

Uncertainty frame focused on the unknown or understudied issues around e-cigarettes, such as the uncertain effects on health, economic prospects legalization, etc.

Information frame referred to introduction and description of e-cigarettes and their features, functions and working mechanism.

We calculated inter-coder reliability by double-coding a random subsample (n = 209 or 32.7%) of the data. Krippendorf’s α ranged from 0.82 to 1.0 for the seven frames, higher than the 0.80 α value indicating acceptable reliability [43]. Final intercoder reliability was α = 0.84 for human impact, α = 0.90 for policy, α = 0.88 for economic, α = 0.96 for morality, α = 0.84 for conflict, α = 0.86 for uncertainty and α = 0.82 for information frame. The overall tone of each article was coded based on what is highlighted the title and the lead and whether the coders would be more or less favorable or no different toward e-cigarettes after reading the story [12]. The reliability of the tone codes was high (Krippendorff’s α = 0.94).

Results

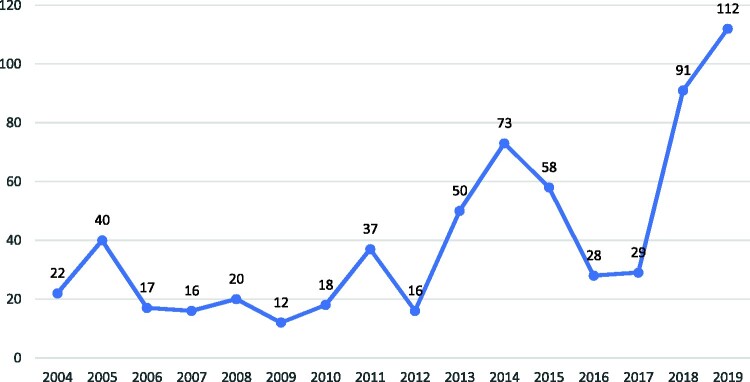

The number of articles on e-cigarettes increased substantially from 2004 to 2019. In 2004, there were 22 e-cigarette stories, rising to 112 during the first 7 months of 2019, suggesting that e-cigarettes gained more attention by the newspapers in China over time (Fig. 2). There were 398 news articles (62.3%) and 241 opinion pieces (37.7%) published in the four time periods. The percentage of news decreased significantly from 82.3% in period 1–41.9% in period 4 (Pearson’s χ2 = 57.35, P < 0.001), while the percentage of opinions significantly increased from 17.7% in period 1–58.1% in period 4 (Pearson’s χ2 = 57.35, P < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Number of media reports on e-cigarettes in Chinese newspaper, 1 January 2004 to 31 July 2019.

To answer RQ1, we calculated the frequency of frames and percentage of articles that had each frame (Table I). The policy frame (n = 168, 26.30%) was the most frequently used primary frame, followed by human impact frame (n = 148, 23.20%), information frame (n = 103, 16.10%), uncertainty frame (n = 102, 16%), economic frame (n = 70, 11%), morality (n = 34, 5.3%) and conflict frame (n = 14, 2.2%).

Table I.

Number and percentage of articles featuring specific frames in four time periods

| Frame | 2004–6 (n = 79) | 2007–10 (n = 66) | 2011–17 (n = 291) | 2018–19 (n = 203) | Total (n = 639) | Pearson’s χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human impact | 12 (15.2) | 16 (24.2) | 71 (24.4) | 49 (24.1) | 148 (23.2) | 3.22 |

| Policy | 0 (0) | 18 (27.3) | 71 (24.4) | 79 (38.9) | 168 (26.3) | 45.45*** |

| Economy | 0 (0) | 3 (4.5) | 54 (18.6) | 13 (6.4) | 70 (11) | 34.05*** |

| Morality | 0 | 0 | 25 (8.6) | 9 (4.4) | 34 (5.3) | 14.64** |

| Information | 64 (81) | 15 (22.7) | 19 (6.5) | 5 (2.5) | 103 (16.1) | 295.98*** |

| Uncertainty | 2 (2.5) | 13 (19.7) | 45 (15.5) | 42 (20.7) | 102 (16) | 14.75** |

| Conflict | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.5) | 6 (2.1) | 6 (3) | 14 (2.2) | 1.03 |

Values in parentheses represent percentage of articles in that time period with the frame. Pearson’s χ2 across time periods.

*P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

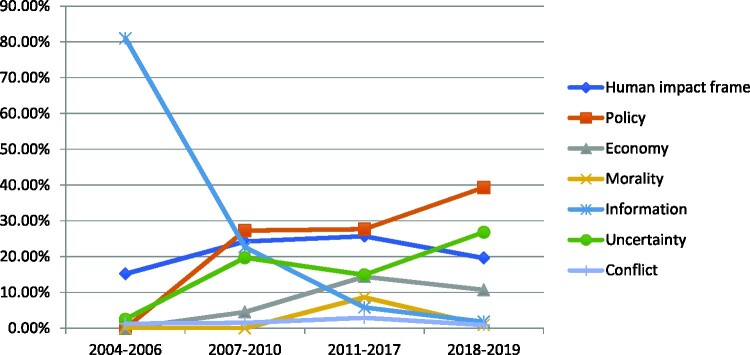

To answer RQ2, Fig. 3 illustrates the percentage of each frame in each year.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of news articles featuring specific frames related ‘e-cigarette’ coverage, 1 January 2004 to 31 July 2019.

We also ran a series of Pearson’s χ2 tests to examine whether the seven frames changed significantly across the four time periods. The human impact frame (Pearson’s χ2 = 3.22, P > 0.05) and conflict frame (Pearson’s χ2 = 1.03, P > 0.05) did not change significantly, while the other five frames showed significant differences. The human impact frame was one of the most prevalent frames, present in 15.2–24.4% of articles per time period. The conflict frame was used the least, present in between 1.3% and 3% of the articles. The policy frame significantly increased across the four time periods (Pearson’s χ2 = 45.45, P < 0.001), and it was particularly prominent in Chinese news coverage of e-cigarettes in the last three time periods, increasing over time. The information frame was the only frame that decreased significantly from Period 1 to Period 4 (Pearson’s χ2 = 295.98, P < 0.001), shrinking from 81% to 2.5% of articles. The economic frame and morality frames fluctuated in the percentage of reports, both reached peak at Period 3 and decreased in Period 4. The uncertainty frame rose from 2.5% of the articles in Period 1 to between 15.5% and 19.7% of the articles in subsequent periods. When we compared the numbers by time period, the information frame dominated press coverage in Period 1, while the policy frame dominated press coverage in Periods 2–4 and increased over time.

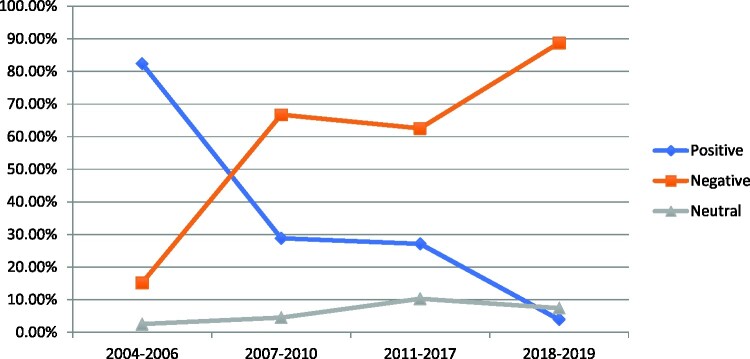

RQ 3 and RQ4 examined the tone of e-cigarette reports and the change over time. Results showed that the majority (n = 418, 65.4%) of the articles was unfavorable toward e-cigarettes, whereas only 171 (26.8%) articles were favorable and 50 (7.8%) articles were neutral. Articles using favorable tone declined significantly across the four time periods (Pearson’s χ2 = 178.33, P < 0.001), while articles using the unfavorable tone increased significantly across the four time periods (Pearson’s χ2 = 137.72, P < 0.001); articles using the neutral tone did not change much across the four time periods (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Percentage of news articles with positive, negative and neutral tone toward ‘e-cigarette’, 1 January 2004 to 31 July 2019.

Discussion

This analysis of the media coverage of e-cigarettes in China suggests that issue frames may be influenced by more than journalists’ cognitive techniques [44]. In this case, the media frames appeared to mirror a competition between policy makers and others concerned about e-cigarette impact on public health—and the different interest groups promoting or profiting from e-cigarettes. One might interpret the findings as two sides attempting to dominate the discursive construction of the e-cigarette issue, with the competition differing across the four time periods in the study. Contextual factors present in each time period support this hypothesis.

Prime time of industry promotion (2004–6)

In the first phase, the major interest group that benefited from the e-cigarette business was the rising e-cigarette industry, particularly Ruyan. When the product first became available in the market in China in 2004, it had not yet caught the attention of governments and scientists locally or globally, so Ruyan, would have had the unfettered opportunity to promote its product, a synonym for e-cigarettes at that time, in the media. We found most of the media reports during 2004–6 used the information frame and a positive tone to promote e-cigarettes, defining them as ‘fashionable’, and a healthy replacement for cigarettes. Other frames were rarely, if ever, found in any of the articles in this phase.

A changing period (2007–10)

The second time period (i.e. 2007–10) could be characterized as a time of significant change: the media tone switched from predominantly positive to primarily negative in this period and was accompanied by large changes in media frame use, with substantially decreasing use of the information frame and increasing use of the policy and uncertainty frames. During this period, the Chinese media extensively reported the international opinion that e-cigarettes are not healthy and should be regulated, which drove the shift in tone. A closer look at the news articles showed that the first turning point in the media’s tone appeared to accompany the 2007 CAAC ban on e-cigarettes in airplanes (Fig. 4). Many news articles in 2007 reported that CAAC’s investigation found that the nicotine in e-cigarettes not only threatened the health of passengers but also polluted the environment on aircrafts similar to combustible cigarettes. Therefore, they concluded that e-cigarette use should be banned on airplanes [37]. However, the social context at that time suggests additional factors may have influenced CAAC’s policy in addition to health concerns.

The FCTC came into force in China in 2006, and with it, an obligation to tighten tobacco control. In 2007, in preparation for the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, China proudly promised the world a smoke-free Olympics and released anti-smoking laws ahead of the ceremony [45]. Therefore, one might hypothesize that the CAAC’s e-cigarette ban served as a political posture in response to both smoke-free Olympics and FCTC obligations, rather than an indicator of Chinese government’s concern about e-cigarette health effects. In fact, the government never officially expressed a clear attitude toward e-cigarettes in this period. Media reports in this period focused more on e-cigarette regulations in foreign countries (using policy frames), and foreign research about e-cigarettes (using human impact frame) rather than on domestic activities. Meanwhile, though many articles reported negative scientific evidence, a few news stories used the uncertainty frame, reporting that the scientific community was divided regarding the impact of e-cigarettes on health and smoking cessation, and stated more research was needed before actions could be taken. Information frames decreased significantly during this period. The leading e-cigarette company, Ruyan, which had commonly appeared in advertorials in the previous phase, faced serious financial problems: its turnover in 2009 decreased 76.99% in comparison with 2008 [46], which may have contributed to the drop in the number of articles using information frame in this phase.

A chaotic period: government and investors join the interest groups (2011–17)

After 2011, demand for e-cigarettes in China increased rapidly, resulting in the appearance of ‘e-cigarette bars and pubs’ on the streets of China, and an increasing number of companies joining the e-cigarette industry. More companies also became part of the global production chain of e-cigarettes by producing and exporting the batteries and other parts of e-cigarettes. Along with an economic boom in e-cigarette business, the financial reporting on the e-cigarette industry increased in 2011. With regards to stock investment, Chinese use the term ‘sectors’ to categorize listed companies in the same business into a category and evaluate the business as a whole. Financial newspapers started to name listing companies that were related to the industry as part of the ‘e-cigarette stock sector’. These activities lead to an increase in positive articles under the frame of economic consequences, portraying e-cigarettes as a rising and promising business that is very attractive to investors.

In addition, the government became invested in e-cigarette interests during this time period. China’s National Tobacco Corporation (China Tobacco), the giant state-owned enterprise and the biggest cigarette manufacturer, built a research center in Shanghai in 2015, which focused on the technology development of e-cigarettes [47]. The actions of China Tobacco might explain why despite increasing negatively toned media reports on concerns about e-cigarettes in other countries (e.g. negative impact on minors and nonsmokers), Chinese policy makers still did not take serious legislative action on e-cigarettes. China Tobacco has significant impact on the government: tax revenue from cigarettes reported by the monopoly was about US$127 billion in 2016, representing almost 6.5% of fiscal revenue in China [48]. The lack of regulation is consistent with the uncertainty frame we found in e-cigarette reporting during this time period. Instead of scientific controversy, we found content on the policy and economic uncertainty of the Chinese e-cigarette markets reflected, for example, in news articles describing the prosperity of the e-cigarette market in China but raising concerns about its future if China were to implement restrictive policies on e-cigarettes.

Time to regulate e-cigarettes! (2018–19)

The Chinese government started to implement restrictive e-cigarette policies in this period. Reports that stationery stores near primary and secondary schools were selling e-cigarettes to students, including e-cigarettes labeled as ‘student e-cigarettes’ sold online [49], triggered more discussion about unethical marketing to youth and motivated action from policy makers. A ban on e-cigarettes sales to minors in 2018 initiated a series of regulations in this period. Following this policy, some local governments, like Hangzhou and Shenzhen, started to set up regulations restricting e-cigarette use, and drafted laws and regulations on e-cigarette manufacture and sales. The policy frame had appeared in news articles since 2007, but most of the early articles using the policy frame to discuss foreign policies, not local ones. In the fourth period, the policy frame was found in reports of domestic policies restricting e-cigarettes, such as the Notice on Prohibiting the Sale of Electronic Cigarettes to Minors issued in 2018 and Notice on Further Protecting Minors from Electronic Cigarettes in 2019, in which e-cigarette sales and advertising were banned. These policies limiting e-cigarette sales were probably not easy to enact. Seven listed companies that belong to the ‘e-cigarette stock sector’ gained a business income of 21.8 billion RMB (around USD $3.36 billion) in 2018 [50]. The central and local government regulations on e-cigarettes would likely have resulted in loss of significant tax revenue from this sector. Throughout the time of study, the conflict frame found in Chinese media mainly reflected conflict between e-cigarette industry and public health. However, in Period 4, the conflict between negative health impact from e-cigarettes (found through scientific research) and concern over public health was reported. In addition to mounting scientific evidence, regulations in this period might also have been linked to China’s goal to establish itself as a responsible power in the international community, which has been a large effort of the Chinese government in recent decades [51].

Conclusion

This study demonstrated how the media frames in Chinese news reports on e-cigarettes changed between 2004 and 2019. The frames used by media reflected the influence of and tension among various forces, including the e-cigarette industry, government and the international tobacco control community on the issue of e-cigarettes in China. At first, e-cigarette manufacturers were the dominant voice, and over time, more reports reflected views of financial investors. The government also benefited financially through tax and the participation of state-owned tobacco industry in the e-cigarette business. Eventually, we found an increasing negative tone about e-cigarettes and, perhaps in response to the obligation of FCTC member countries, the Chinese government issued a series of restrictions on e-cigarettes. What makes China’s case different from many other countries is the faint voice from domestic public health professionals, and the dominant role of government in shaping the e-cigarette issue and media representation. In addition, the international public health community was found in Chinese news stories and seemed to be an important and reliable information source in defining the health risk of the products. As China has been making efforts to build a positive image on the international stage, international public health communities may have an increased ability to encourage the Chinese government to impose stricter regulations on e-cigarettes. The potential for the international public health community to influence the Chinese government may apply not only applicable to e-cigarette control but also to tobacco control efforts in China in general.

Funding

This research was supported by National Cancer Institute (NIH) grant T32 CA 113710 (J.C.L.), National Cancer Institute (NIH) Grant, CA 141661 (P.M.L.), Macau Higher Education Fund, Grant ID: HSS-MUST-2020-05 and Macau University of Science and Technology Faculty Research Grants, Grant ID: FRG-20-002-FA (D.W.).

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Contributor Information

Joanne Chen Lyu, Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, University of California, San Francisco, USA.

Di Wang, Faculty of Humanities and Arts, Macau University of Science and Technology, Macau, China.

Zhifei Mao, School of Media and Communication, Shenzhen University, China.

Pamela M Ling, Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, University of California, San Francisco, USA.

References

- 1. Prescient & Strategic Intelligence. E-Cigarette Market Research Report, 2020. Available at: https://www.psmarketresearch.com/market-analysis/e-cigarette-market. Accessed: 13 September 2020.

- 2. Malas M, van der Tempel J, Schwartz R et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res 2016; 18: 1926–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bell K, Keane H. All gates lead to smoking: the “gateway theory”, e-cigarettes and the remaking of nicotine. Soc Sci Med 2014; 119: 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. E-cigarette use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General, 2016. Available at: https://e-cigarettes.surgeongeneral.gov/documents/2016_SGR_Full_Report_non-508.pdf. Accessed: 6 September 2020.

- 5. Eriksen M, Mackay J, Schluger N. The Tobacco Atlas. 5th edn. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Feldman EA, Yue C. E-Cigarette Regulation in China: The Road Ahead, 2016. Available at: http://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/1704. Accessed: 13 September 2020.

- 7. ITC China. ITC China Project Report: Findings from the Wave 1 to 5 Surveys (2006-2015). International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project. 2017. Available at: https://itcproject.org/resources/view/2488. Accessed: 6 June 2020.

- 8. Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations, 4th edn. NY: Free Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yates K, Friedman K, Slater MD et al. A content analysis of electronic cigarette portrayal in newspapers. Tob Regul Sci 2015; 1: 94–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Knight MG. Getting past the impasse: framing as a tool for public relations. Public Relat Rev 1999; 25: 381–98. [Google Scholar]

- 11. An S-K, Gower KK. How do the news media frame crises? A content analysis of crisis news coverage. Public Relat Rev 2009; 35: 107–12. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim S-H, Thrasher JF, Kang M-H et al. News media presentations of electronic cigarettes: a content analysis of news coverage in South Korea. J Mass Commun Q 2017; 94: 443–64. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Patterson C, Hilton S, Weishaar H. Who thinks what about e-cigarette regulation? A content analysis of UK newspapers. Addiction 2016; 111: 1267–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rooke C, Amos A. News media representations of electronic cigarettes: an analysis of newspaper coverage in the UK and Scotland. Tob Control 2014; 23: 507–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goffman E. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Cambridge, MAss: Harvard University Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gamson WA. Talking Politics. Cambridge, TAS, Australia: Cambridge University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gamson WA, Modigliani A. Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: a constructionist approach. Am J Sociol 1989; 95: 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Entman RM. Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J Commun 1993; 43: 51–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Scheufele DA, Tewksbury D. Framing, agenda setting, and priming: the evolution of three media effects models: models of media effects. J Commun 2007; 57: 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Vreese CH. News framing: theory and typology. Inf Des J 2005; 13: 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Semetko HA, Valkenburg PMV. Framing European politics: a content analysis of press and television news. J Commun 2000; 50: 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- 22. de Vreese CH, Peter J, Semetko HA. Framing politics at the launch of the euro: a cross-national comparative study of frames in the news. Polit Commun 2001; 18: 107–22. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Iyengar S. Is Anyone Responsible?: How Television Frames Political Issues. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cappella JN, Jamieson KH. Spiral of Cynicism: The Press and the Public Good. NY: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Neuman WR, Just MR, Crigler AN. Common Knowledge: News and the Construction of Political Meaning. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nisbet MC, Brossard D, Kroepsch A. Framing science: the stem cell controversy in an age of press/politics. Harv Int J Press/Politics 2003; 8: 36–70. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dimitrova DV, Kaid LL, Williams AP et al. War on the web: the immediate news framing of gulf war II. Harv Int J Press/Politics 2005; 10: 22–44. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu APL. Communication and National Integration in Communist China. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li L, Lin H. Monopoly, free competition, monopolistic competition: an Analysis of the trend of contemporary Chinese news media grouping. Journalistic University 1999; 2: 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brady A-M. Guiding hand: the role of the CCP central propaganda department in the current era. Westminst Pap Commun Cult 2006; 3: 58. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stockmann D. Communication, Society and Politics: Media Commercialization and Authoritarian Rule in China. Cambridge, TAS, Australia: Cambridge University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang Y, Li N, Li J. Media coverage and government policy of nuclear power in the People’s Republic of China. Prog Nuclear Energy 2014; 77: 214–23. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu Y. “Ruyan” status leads to embarrassment of supervision, claiming to “fill legal gap.” Beijing Times, 2016.

- 34. WHO. China Tightens Rules on Smoking in Public Places and Indirect Advertising, 2017. Available at: https://www.who.int/fctc/implementation/news/chnews/en/. Accessed: 6 June 2020.

- 35. NPC (National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China). The Advertisement Law of People’s Republic of China, 2015. Available at: http://www.npc.gov.cn/. Accessed: 6 June 2020.

- 36. SAIC (State Administration for Industry and Commerce). The Interim Regulation on Internet Advertisement, 2016. Available at: http://www.saic.gov.cn/fgs/lflg/201612/t20161206_172910.html. Accessed: 6 June 2020.

- 37. Yang Q. Civil aviation administration of China bans ruyan on airplanes. Shanghai Morning News, 2007. Available at: http://news.sina.com.cn/c/2007-09-24/015212620569s.shtml. Accessed: 6 September 2020.

- 38. Wang X. Regulators ban e-cigarette sales online. China Daily, 2019. Available at: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201911/02/WS5dbcc10fa310cf3e35574fe4.html. Accessed: 11 June 2020.

- 39. Kuttschreuter M, Gutteling JM, de Hond M. Framing and tone-of-voice of disaster media coverage: the aftermath of the Enschede fireworks disaster in the Netherlands. Health Risk Soc 2011; 13: 201–20. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lin Z, Guo Y, Chen Y. Macro-public relations: crisis communication in the age of internet. Int j Cyber Soc Educ 2013; 6: 123–38. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lyu JC. A comparative study of crisis communication strategies between Mainland China and Taiwan: the melamine-tainted milk powder crisis in the Chinese context. Public Relat Rev 2012; 38: 779–91. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shehata A, Hopmann DN. Framing climate change: a study of US and Swedish press coverage of global warming. J Stud 2012; 13: 175–92. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. 4th edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Obregon R, Waisbord S, (eds). The Handbook of Global Health Communication: Obregon/the Handbook of Global Health Communication. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 45. WHO. The Health Legacy of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games: Success and Recommendations, 2010. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/207690/9789290614593_eng.pdf. Accessed: 6 June 2020.

- 46. Ruyan Group (Holdings) Limited 2009 Annual Report. HKEXnews, 2010. Available at: https://www1.hkexnews.hk/listedco/listconews/sehk/2010/0429/ltn201004291665.pdf. Accessed: 6 June 2020.

- 47. China Tobacco. The Official Establishment of the Research Center of New Tobacco Products, 2015. Available at: http://www.tobacco.gov.cn/html/30/3004/4821732_n.html. Accessed: 6 June 2020.

- 48. Goodchild M, Zheng R. Early assessment of China’s 2015 tobacco tax increase. Bull World Health Organ 2018; 96: 506–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wan J. The State Administration of Market Regulation and the State Tobacco Monopoly Administration Issued a Notice Banning the Sale of Electronic Cigarettes to Minors, 2018. Available at: http://www.xinhuanet.com/legal/2018-09/05/c_129947671.htm. Accessed: 6 June 2020.

- 50. E-cigarettes become trendy business: global e-cigarette market size reaches $ 14.5 billion. Sina Finance, 2019. Available at: https://finance.sina.com.cn/chanjing/cyxw/2019-09-09/doc-iicezzrq4536094.shtml. Accessed: 6 June 2020.

- 51. Men H. China’s Grand Strategy: A Framework Analysis. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 52. ITC China. Timeline of Tobacco Control Policies and ITC Surveys (CN), 2020. Available at: https://itcproject.org/countries/china-mainland/. Accessed: 13 September 2020.