Abstract

Background

The COVID‐19 pandemic has had a profound impact on medical care and medical student education as clinical rotations were halted and students' clinical activities were drastically curtailed. Learning experiences in medical school are known to promote identity formation through teamwork, reflection, and values‐based community discussion. This study explored the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on medical students' professional identity formation (PIF).

Methods

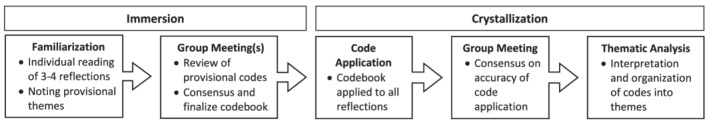

Students in all cohorts of medical education were invited by email in May 2020 to submit a written reflection about their learning experiences and impact of the pandemic on their PIF. We used iterative individual and team reviews, known as the “immersion/crystallisation” method, to code and analyse the data.

Findings

Twenty‐six students (20%) submitted reflections in which they discussed “changing conceptions of the role and image of a physician,” “views about medical education,” and the “role of students in a pandemic.” Students viewed physicians as altruistic, effective communicators, and pledged to be like them in the future. Their perceptions of virtual learning were mixed, along with considerations of lost interactions with patients, and wanting to be more useful as professionals‐in‐training.

Discussion

COVID‐19 has impacted students' views of themselves and reshaped their ideas, both negatively and positively, about the profession they are entering and their role(s) in it.

Conclusion

Exploring PIF and the impact of disruptions has allowed us to address the issues raised regarding clinical learning now and into the future. Reflection enhances PIF and unexpected events, such as COVID‐19, offer opportunities for reflection and development.

1. BACKGROUND

Professional identity formation (PIF) in medicine has been defined as a lifelong process through which medical students internalise professional values, ethics, knowledge, and skills that enable them to practice with confidence and give others confidence in their abilities. 1 Medical student PIF is largely experiential and occurs through engagement with patients, the health care team, and the community. 2 It is achieved by observing others, role modelling, reflecting on one's experience, and learning to improve one's performance guided by the values of the profession. 3 Some have argued that much of PIF is learned informally by observing and adopting behaviours in which others engage. 4 Critical experiences, including curricular changes that resulted from the COVID‐19 pandemic, would be expected to impact PIF, as students make sense of their developing professional selves during a crisis. 5 A growing body of literature points to the analysis of reflective narratives as a useful method for understanding the experience of trainees' processes of PIF. 3 , 6 , 7

The COVID‐19 pandemic has had a profound effect on medical education. Under the guidance of the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC), clinical rotations were halted and the majority of US medical students were removed from in‐person clinical placements in March of 2020. 5 , 8 Removal was necessitated by scarce resources, including a shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), testing supplies, and the need to minimise the risk of acquiring the virus through contact with patients and other health care professionals. 5

In response to the pandemic, health professions education curricula across the country, and the world, were transformed significantly. Medical schools were forced to quickly review all aspects of training and adapt to virtual teaching platforms and online teaching resources. 9 Basic science curricula transitioned to live‐streamed or recorded lectures and convening of virtual small groups. Clinical rotations were replaced with virtual didactic sessions and cases, and the academic calendar was modified to accommodate the requirements for hands‐on clinical experience. 10 , 11 , 12 Despite medical educators' efforts to adjust curricula to ensure meaningful learning experiences for students, some educators expressed concerns about learning based on digital technology, 13 while others asserted that changes in educational modalities might endanger professional identity formation through lost opportunities to engage with peers and teachers in the clinic and the classroom. 14

Medical educators have underscored the importance of understanding the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on PIF. 14 , 15 , 16 An early survey of US medical students revealed that nearly half endorsed the idea that COVID‐19 had shaped or influenced the trajectory of their careers. 12 University of California San Francisco School of Medicine paused its foundational science curricula and clinical clerkships to focus on PIF using guided reflection to give students an opportunity to confront the tensions between personal and professional duties during the pandemic. 17 Findyartini and colleagues explored reflections about how medical students adapted to changes brought about by the COVID‐19 pandemic 18 ; however, the broader question of how COVID‐19 has impacted medical students' views of professional identity remains largely unstudied.

This study utilised thematic analysis, a basic interpretive qualitative approach, to describe the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on medical students' PIF using written reflections. 19 While numerous conceptualizations of PIF exist, we conceptualise it as lifelong and dynamic, being developed through interactions and relationships. 1 This study investigates PIF through the three overlapping domains of professionalism, psychosocial identity development, and formation, as proposed by Holden and colleagues. 20 These domains include interrelated processes of reflection, internalisation and embodiment of ethics and values, self‐efficacy, role modelling, exploration, and commitment. 20 Our study was conducted during the initial wave of the pandemic when medical students were removed from in‐person activities and clinical placements. Our study was designed to answer the following research question: How do medical students describe the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on their professional identity formation and thoughts about their medical education?

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants and data collection

Medical students in all years were invited to take part in this study. All students had been removed from in‐person classroom and point of care learning and had been entered into a virtual teaching curriculum. The preclinical curriculum consisted of facilitator‐led eight‐person problem‐based learning sessions and interactive 16‐ to 32‐person seminars. These modified virtual sessions were facilitated using Zoom Video Communication, Inc. (2020). Students in their clinical years completed online virtual cases and preceptor‐led telehealth encounters with patients in virtual visits.

Students were asked to write a 150 to 200‐word reflection using the following prompt: “How has the [COVID‐19] pandemic impacted the way(s) you think about your medical education and your professional identity as a physician in training?” Reflections were solicited in May 2020, approximately 6 weeks after the students had been removed from the in‐person curriculum and clerkship rotations. 5 Completion of the reflection was optional, and students were also given the opportunity to opt out of having their reflection used in this study. Reflection prompts were sent via email and responses were entered into a REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) database, a web‐based application for data collection. All reflections were anonymized prior to data analysis.

2.2. Data analysis

Reflections were analysed using immersion/crystallisation, a systematic qualitative method for identifying themes (Figure 1). 21 The first step involves familiarisation, an iterative process in which reflections were read multiple times individually and in team meetings. Team members read through groups of three to four reflections at a time, making marginal notes, and identifying provisional codes inductively. The provisional codes were then reviewed in successive team meetings until consensus was reached and final codebook was agreed upon (immersion). The codebook was applied to all reflections and consensus regarding accuracy of coding was reached by the team (crystallisation). During interpretation, codes were reviewed, categorised into themes, and interpreted through the lens of the three overlapping domains of PIF. 20

FIGURE 1.

Process of immersion/crystallisation method of data analysis

The Institutional Review Board granted this study exempt status (#19‐974).

2.3. Findings

Twenty‐six medical students consented to their reflections being used in this study (10 preclerkship and, 16 clinical‐years students; 20% of students). The average length of the written reflections was 300 words. Students broadly reflected on the experience in three main ways: (1) “changing conceptions of the role and image of a physician,” (2) “views about medical education,” and (3) “the role of medical students in a pandemic.” Each theme had several subthemes. Descriptions and a representative quote for each subtheme can be found in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Description of subthemes and representative quotes for each theme

| Changing conceptions of the role and image of a physician | ||

|---|---|---|

| Subtheme | Description | Quote |

| Running toward danger. | Physicians are the ones who run toward danger, risking their own health to improve others. | I think this pandemic has reminded me that we are the ones who run toward danger, not away from it. We have chosen this profession and as such, we have professed our lives to serving society, whatever that means moment by moment. In this moment, and likely in future moments, it means sacrificing time, resources, and personal safety to help others. (Preclerkship) |

| Pledge to be [insert] physician. | Expressions of the types of physicians students want to be in the future. | I will don my PPE. I will work harder than I ever have before. I will aim to provide the best possible care to my patients. I will come home from work, wash my scrubs, shower, isolate myself from my partner, go to bed in a separate room, and repeat the cycle the next day. I will rise to the occasion, and I will protect myself and loved ones. (Clinical years) |

| Proving effective science and health communication. | Physicians build trust in the profession by effectively communicating about the pandemic. Students practiced this skill with friends and family. | I've realised the responsibility we have as physicians/physicians‐in‐training to stay informed on the latest COVID updates. Despite my limited medical education, my family frequently asks me for my perspectives on the latest coronavirus news. I find it likely that many other medical professionals experience a similar level of pressure to remain informed because of patients and family who ask for their seasoned perspectives on the pandemic. (Preclerkship) |

| Views about medical education | ||

|---|---|---|

| Subtheme | Description | Quote |

| Time for reflection. | Virtual curriculum allows for increased time for reflection on education and career goals. | The pandemic has led to many moments of reflection on my medical education, as well as my future goals as a physician. I have realised how important in‐person interaction with patients is for me to feel fulfilled. Last week, I participated in a telemedicine visit instead of virtual rounds and I felt so much better after speaking directly to a patient. I also realise that I learn much better from the team around me when there are opportunities to participate in discussions, ask questions, and learn from residents, fellows, and attending physicians in the hospital. (Clinical years) |

| Adaptability of online curriculum. | Basic sciences and virtual cases were viewed as effective adaptations to online curriculum. | I think that while the physical exam is such a crucial tool in the clinician's toolbelt, I have been surprised at how much we are learning because we have to find alternate ways to learn than seeing patients. In some ways, learning how to gain guideline information from interactive simulated cases and articles has provided a more robust knowledge base than we otherwise obtain in our busy in person rotation schedules. (Clinical years) |

| Dissatisfaction with virtual curriculum. | Virtual clerkship activities viewed as “busy work.” | We have been given work to do solely for the purpose of showing that we are doing work. This additional burden on top of test studying is a detriment to our growth as physicians. (Clinical years) |

| Need for interaction. | Lack of in‐person interaction results in feelings of social isolation. | The disruption the COVID‐19 pandemic has played on the tail end of my first year of medical school has greatly impacted how I view my medical education experience. Although every effort possible has been made to replicate the classroom experience virtually, the effects of being isolated from peers, facilitators, and lecturers are apparent. (Preclerkship) |

| The role of medical students in a pandemic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Subtheme | Description | Quote |

| Medical students as nonessential. | Students argued removal from clinic eliminated opportunity to learn valuable skills; Students questioned whether they had learned any skills that would be valuable in the clinic. | I was losing the opportunity of a lifetime … the opportunity to be on the front lines and do the very thing that brought me to medicine. I was losing the opportunity to learn how to care for patients during a pandemic. I wished it had been different. I wished I had enough knowledge and skills to contribute during this time and in exchange learn from the providers taking care of patients with this illness. (Clinical years) |

| A way to get involved. | Students volunteered to call patients, deliver negative test results, and answer virus‐related questions. | The most direct way for me to get involved was by calling patients back to discuss negative test results … During my calls it was just as common to spend time discussing the worry that someone felt about family members, coworkers, or children as it was to discuss their own symptoms. For many people facing the same frustration and sense of powerlessness as me, I suspect that being able to discuss their fears and frustrations was as much of a relief as receiving the negative test result. (Clinical years) |

2.4. Changing conceptions of the role and image of a physician

Many students described the role of physicians as members of society with special training who run toward, rather than away from, danger during a crisis like a pandemic. One clerkship student stated:

This is really the first time that I have observed physicians responding to a crisis like this on a large scale. I have felt the desire to be one of those running towards the crisis, and even though it is frustrating now that I cannot really participate in direct care with patients, it has reinforced that I chose the right profession. Having that responsibility as part of my professional identity in the future is both intimidating and exciting.

While many students expressed their admiration and respect for all essential workers, special note was made of the professionalism and altruism of physician role models, thus affirming their own career choice. Several expressed a desire, and made pledges, to be like the physicians they observed or read about during the pandemic. However, witnessing physicians in danger of becoming infected was a disconcerting realisation that they had not considered, especially in light of the lack of PPE at the beginning of the pandemic.

Witnessing physicians in danger of becoming infected was a disconcerting realisation that they had not considered.

Several students mentioned the importance of staying informed during the pandemic. They noted the extent to which the public and community leaders rely upon on knowledgeable physicians, public health experts, and researchers, to communicate accurate and trustworthy scientific information. Others described the importance of having accurate scientific information on hand to counsel family and friends despite limitations on their formal education.

2.5. Views about medical education

Students expressed a mix of benefits and challenges with the abrupt change from in‐person to virtual curricula in preclerkship and clerkship years. For example, many students described a benefit of the pandemic in terms of having more free time to reflect on career goals as well as opportunities for self‐care. At the preclerkship level, many students considered the basic science curriculum to be well‐adapted for virtual learning. A first‐year student stated, “COVID has shown us that a virtual curriculum can be as efficacious as in‐person sessions.”

At the clerkship level, some students considered virtual (online) cases to be beneficial given the increased volume of clinical content, while others regarded them as “busy work,” and a waste of their time. Across all training levels, students lamented the loss of time in the clinical setting, and some felt isolated from peers, patients, and the health care team.

2.6. The role of medical students in a pandemic

Being excluded from in‐person clinical learning experiences prompted a range of responses about the role of medical students on the health care team. A small subset of students described the steps they took to remain involved in patient care. These students volunteered to call patients and deliver negative COVID‐19 test results, which often led to longer conversations with patients' about virus‐related and other concerns.

Another group of students questioned why they were not permitted to provide direct service on the health care team, arguing that it deprived them of a skill set that would prove useful in the event of another pandemic. One clerkship student stated:

I have come to [the realization] that medical students are viewed as non‐essential in the hospital. On the surface, this makes sense because we do not want to unnecessarily risk student infection or have them serve as an infection reservoir to vulnerable patients. However, as I come to the close of my 3rd year in medical school, this situation made me realize that I am mostly useless in a clinical setting at this point. Outside of gathering a basic history and physical, there is very little I can contribute to the clinical team.

Finally, some students expressed the hope that the pandemic would serve as an opportunity for medical educators to be better prepared to offer meaningful medical student education in the face of future crises like the COVID‐19 pandemic.

3. DISCUSSION

The COVID‐19 pandemic is likely to have significant short‐ and long‐term impacts across all levels of medical education. Reflective writing provides an opportunity to rapidly sample student responses to critical events affecting PIF. Student narratives also offer medical educators valuable insights into the lived experience of the pandemic and, in turn, timely opportunities to craft curricula that are responsive to emerging student needs across domains of PIF. 3 , 20

Reflective writing provides an opportunity to rapidly sample student responses to critical events affecting PIF.

Our results echo the conclusion of Stetson and colleagues that reflection is a worthwhile activity for exploring PIF. 17 Similarly, our finding that volunteering was one way for students to fulfil a desire to maintain involvement in patient care is similar to what Findyartini and colleagues report in the Indonesian context. 17 However, our study advances the understanding of PIF though additional evidence of the significance of role models on PIF, despite reductions in contact with them. 3 , 22 Heroic physicians, whether faculty or appearing in the mass media, served as exemplars for types of physicians the students aspired to be and the qualities they hope to embody in the future. Further, removal from the clinical setting was identified as a possible barrier to advancing PIF in some students.

Several students described how the modified curriculum afforded additional opportunities for reflection and growth. 23 Reflection on critical experiences is essential in identity formation as it promotes examination of the qualities one wishes to embody 20 and forms the basis for future action. 24 , 25 , 26 Focusing the writing prompt on PIF allowed students to express their current perspectives and imagine the impact of the pandemic on their future selves as physicians. The fact that there was variation in perspectives suggests that “one size fits all” may not be an ideal approach to educational programming during a health crisis, a finding medical educators may want to consider in terms of curricular impact on PIF. 3 , 18 , 27

Focusing the writing prompt on PIF allowed students to express their current perspectives and imagine the impact of the pandemic on their future selves as physicians.

Several authors have warned that extended time away from clinical experiences will result in ethical dilemmas as students weigh the trade‐offs between their desire to fulfil their duty to patients, on the one hand, and avoid being a vector of disease spread, on the other hand. 28 Additionally, extended exclusion from the clinic may signal to students that they are simply observers, not integral members of the health care team. 15 , 29 , 30 Indeed, several clerkship students echoed these sentiments in their reflections and also questioned whether they had developed any skills that would be useful in a clinical setting during a crisis or pandemic. At the same time, students who described volunteering despite being unable to participate in clerkship rotations expressed satisfaction and a sense of usefulness. These results underscore the importance of self‐efficacy to identity formation 20 and suggest a promotion of student involvement through volunteerism in nonclinical care, e‐consultations, staffing hotlines, scouring the literature for up‐to‐date research, calling patients with test results, and other phone‐based services. 10 , 15 , 16 , 29 , 31 Not providing these opportunities for students in their clerkship years risks promoting identity dissonance 32 based on their desire to embody professional attributes, such as altruism, while at the same time being unable to participate the very activity that would reinforce them. 15 , 16 , 20

Extended exclusion from the clinic may signal to students that they are simply observers, not integral members of the health care team.

Students who described volunteering despite being unable to participate in clerkship rotations expressed satisfaction and a sense of usefulness.

These reflections represent a first person view of students' perceptions of the modified medical curriculum due to the pandemic. Reflections were not submitted as a component of the curriculum and the students who completed reflections did so voluntarily. A rapid analysis of the reflections could have allowed us to make actionable modifications to the curriculum to support PIF during the pause in clinical experiences. For example, we could have designed competency‐based experiences where students could have utilised skills appropriate to their training level to foster feelings of usefulness and to practice new skills or those they have already developed. One option for medical educators is to analyse reflections using rapid evaluation methods as they provide timely analysis, identification, and dissemination of critical findings such that they can be applied contemporaneously rather than historically. 32

These reflections represent a first person view of students' perceptions of the modified medical curriculum due to the pandemic.

Limitations of this study include sample size and transferability. The low response rate is likely multifactorial. Second year students were not included in this study as they were on leave for USMLE Step 1 preparation. Additionally, reflections were voluntary and 13 students completed reflections but elected not to include them in this study, indicating a hesitancy of about sharing reflections for research. A second limitation is transferability in that these reflections may not be representative of the students at our institution who did not complete a reflection or those at other institutions. However, the COVID‐19 pandemic had global consequences and by providing rich descriptions and context through participant quotations, these results may be applicable to other settings. 33 Future studies should investigate the long‐term impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic and curricular modifications on medical student identity formation.

4. CONCLUSION

In many ways, the COVID‐19 pandemic has been a perfect storm, a rare combination of circumstances that interrupted life as we knew it, including students learning to become physicians. Rapid sampling of reflections on professional identity formation is one way to assess the experience of becoming a medical professional during a pandemic. Additionally, written reflections provide medical educators “primary” data about the range of students' needs, and opportunities to be resourceful in crafting curricula that are sensitive to those needs. Reflective writing is a simple, cost effective way to get a snapshot of responses to an ongoing crisis. Much like an educational portfolio, multiple reflections can provide a synopsis or panorama of a medical student's professional identity development over time and are an enduring artefact of what it was like during the perfect storm and after it passed. Reflection is known to enhance professional identify formation and unexpected events, such as COVID‐19, offer an opportunity for students to pause and “bracket” their experiences and in so doing become more aware of just how powerful these experiences are in shaping their current and future identities as medical professionals.

Written reflections provide medical educators “primary” data about the range of students' needs.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The Institutional Review Board at Cleveland Clinic granted this study exempt status (#19–974).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank the students for voluntarily sharing their experiences in their reflective essays.

Byram JN, Frankel RM, Isaacson JH, Mehta N. The impact of COVID‐19 on professional identity. Clin Teach. 2022;19(3):205–212. 10.1111/tct.13467

REFERENCES

- 1. Monrouxe LV. Identity, identification and medical education: why should we care? Identity, identification and medical education. Med Educ. 2010;44(1):40–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Monrouxe LV. Theoretical insights into the nature and nurture of professional identities. In: Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y, editors. Teaching Medical Professionalism: Supporting the Development of a Professional Identity. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2016. p. 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wong A, Trollope‐Kumar K. Reflections: An inquiry into medical students' professional identity formation. Med Educ. 2014;48(5):489–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hafferty FW. Professionalism and the socialization of medical students. In: Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y, editors. Teaching Medical Professionalism: Supporting the Development of a Professional Identity. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2016. p. 54–67. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Important guidance for medical students on clinical rotations during the Coronavirus (COVID‐19) outbreak [Internet]. Aamc.org. [cited 2021 Apr 19]. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/important-guidance-medical-students-clinical-rotations-during-coronavirus-covid-19-outbreak

- 6. Branch WT Jr, Frankel R. Not all stories of professional identity formation are equal: an analysis of formation narratives of highly humanistic physicians. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(8):1394–9. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clandinin J, Cave MT, Cave A. Narrative reflective practice in medical education for residents: composing shifting identities. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2010;2:1–7. 10.2147/AMEP.S13241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harries AJ, Lee C, Jones L, et al. Effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic on medical students: a multicenter quantitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gordon M, Patricio M, Horne L, et al. Developments in medical education in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic: a rapid BEME systematic review: BEME guide no. 63. Med Teach. 2020;42(11):1202–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rose S. Medical student education in the time of COVID‐19. Jama. 2020;323(21):2131–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coffey CS, MacDonald BV, Shahrvini B, Baxter SL, Lander L. Student perspectives on remote medical education in clinical core clerkships during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Med Sci Educ. 2020;30(4):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shahrvini B, Baxter SL, Coffey CS, MacDonald BV, Lander L. Pre‐clinical remote undergraduate medical education during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a survey study. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ahmed H, Allaf M, Elghazaly H. COVID‐19 and medical education. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):777–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cullum RJ, Shaughnessy A, Mayat NY, Brown ME. Identity in lockdown: supporting primary care professional identity development in the COVID‐19 generation. Educ Prim Care. 2020;31(4):200–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kalet AL, Jotterand F, Muntz M, Thapa B, Campbell B. Hearing the call of duty: what we must do to allow medical students to respond to the COVID‐19 pandemic. WMJ. 2020;119(1):6–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chandratre S. Medical students and COVID‐19: challenges and supportive strategies. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520935059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stetson GV, Kryzhanovskaya IV, Lomen‐Hoerth C, Hauer KE. Professional identity formation in disorienting times. Med Educ. 2020;54(8):765–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Findyartini A, Anggraeni D, Husin JM, Greviana N. Exploring medical students' professional identity formation through written reflections during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Public Health Res. 2020;9(Suppl 1):1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Merriam SB, Grenier RS (Eds). Qualitative Research in Practice: Examples for Discussion and Analysis. 2nd ed., San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holden M, Buck E, Clark M, Szauter K, Trumble J. Professional identity formation in medical education: the convergence of multiple domains. HEC Forum. 2012;24:245–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Borkan J. Immersion/crystallization. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed., Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 1999. p. 179–94. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ibarra H. Provisional selves: experimenting with image and identity in professional adaptation. Adm Sci Q. 1999;44(4):764–91. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wald HS. Professional identity (trans)formation in medical education: reflection, relationship, resilience: reflection, relationship, resilience. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):701–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mezirow J. How critical reflection triggers transformative learning. Fostering Critical Reflection in Adulthood. 1990;1(20):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Branch WT Jr. Use of critical incident reports in medical education. A perspective. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):1063–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sandars J. The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE guide no. 44. Med Teach. 2009;31(8):685–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ryynänen K. Constructing Physician's Professional Identity: Explorations of Students' Critical Experiences in Medical Education [dissertation] Oulu, Finland: University of Oulu; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hjiej G, Fourtassi M. Medical students' dilemma during the Covid‐19 pandemic; between the will to help and the fear of contamination. Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1):1784374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Khamees D, Brown CA, Arribas M, Murphey AC, Haas MR, House JB. In crisis: medical students in the COVID‐19 pandemic. AEM Education and Training. 4(3):284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Anderson V. Academic during a pandemic: reflections from a medical student on learning during SARS‐CoVid‐2. HEC Forum. 2021;33(1–2):35–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li HO‐Y, Bailey AMJ. Medical education amid the COVID‐19 pandemic: new perspectives for the future. Acad Med. 2020;95(11):e11–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McNall M, Foster‐Fishman PG. Methods of rapid evaluation, assessment, and appraisal. Am J Eval. 2007;28(2):151–68. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]