Abstract

In the past decade, there has been a shift in research, clinical development, and commercial activity to exploit the many physiological roles of RNA for use in medicine. With the rapid success in the development of lipid–RNA nanoparticles for mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 and with several approved RNA-based drugs, RNA has catapulted to the forefront of drug research. With diverse functions beyond the role of mRNA in producing antigens or therapeutic proteins, many classes of RNA serve regulatory roles in cells and tissues. These RNAs have potential as new therapeutics, with RNA itself serving as either a drug or a target. Here, based on the CAS Content Collection, we provide a landscape view of the current state and outline trends in RNA research in medicine across time, geography, therapeutic pipelines, chemical modifications, and delivery mechanisms.

Introduction

Recent advances in RNA design and delivery have enabled the development of RNA-based medicine for a broad range of applications, including therapeutics, vaccines, and diagnostics. While human RNA medicine has faced many challenges in terms of efficacy and immunogenicity, the recent success of mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 and the approval of new RNA-based drugs provide new momentum to the field. Many classes of RNA play important regulatory roles in cells and tissues, beyond the obvious role of mRNA in protein synthesis. Scientific research, clinical development, and commercial production now focus on exploiting the many roles of RNA for use in biotechnology and medicine. Advances in understanding RNA structure and function are combined with a robust production pipeline to develop clinically effective RNA-related applications.1−12

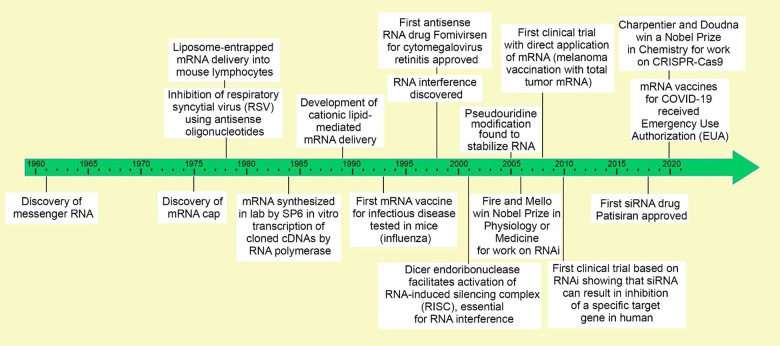

Many key discoveries have contributed to the advancing of RNA medicines we have today. Early research in the 1960s on nucleic acids led to the discovery of mRNA.13 In the next decade, the 5′-cap on mRNA was discovered,14,15 the first liposome-entrapped RNA was delivered into cells,16 and antisense oligomers (ASOs) were used to inhibit Rous sarcoma virus (RSV).17 In the 1980s, in vitro transcription from engineered DNA templates using a bacteriophage SP6 promoter and RNA polymerase18 allowed the manufacture of mRNA and expression of other types of RNA in cell-free systems. Later in the 1980s, the first cationic-lipid-mediated mRNA delivery was achieved.19,20 The discovery of RNA interference (RNAi)21 and the approval of the first antisense RNA drug in the late 1990s22 were key to the development of RNA therapeutics. For their pioneering work on RNAi and the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC),23 Fire and Mello21 were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 2006. During the 2000s, the discovery of the importance of pseudouridine modification24 and further research on mRNA led to the first human trial of an mRNA vaccine against melanoma in 2008.25 In 2010, a pivotal human clinical trial showed that siRNA could target specific human genes,10 and subsequent pre-clinical research and development led to the approval of the first siRNA drug in 2018.26 Most recently, Doudna and Charpentier were awarded the Nobel Prize in 2020 for CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. In a CRISPR-Cas9 system, a small piece of RNA with a short “guide” sequence attaches to a specific target sequence of DNA in a genome; the RNA also binds to the Cas9 enzyme—thus, the modified RNA is used to recognize the DNA sequence, and the Cas9 enzyme cuts the DNA at the targeted location.27 Two human mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 received Emergency Use Authorization in 2020, and one of them was finally approved in 2021.28−30 These key milestones and achievements are captured in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Timeline of major RNA research and development milestones. A more detailed timeline table complete with references is provided as Table S1.

RNA technology provides an innovative approach for developing new drugs for rare or difficult-to-treat diseases. Since 2014, several drugs have been approved to treat macular degeneration, Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), polyneuropathy, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.31 Drugs to treat many other diseases, including cancer, hepatic and renal diseases, cardiac diseases, metabolic diseases, blood disorders, respiratory diseases, and autoimmune diseases are currently in various stages of clinical studies, some showing promising results.

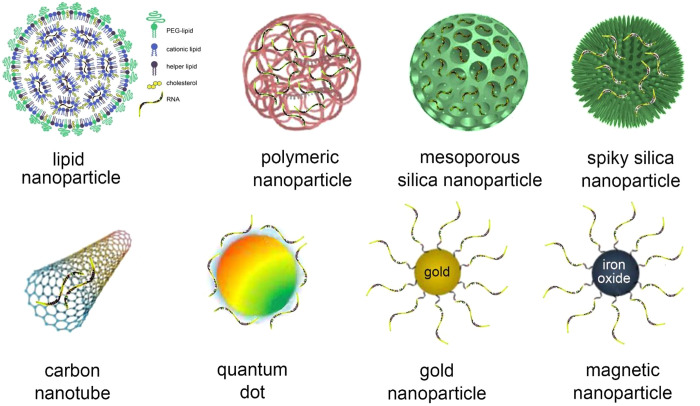

Compared to other biomolecules, RNA molecules are unstable and transient. Foreign RNA molecules, when introduced to the human body, have limited protein expression levels in cells and often trigger immunogenicity in the body. However, these practical problems can often be mitigated by various optimizations on RNA molecules, including chemical modifications, mRNA cap/codon/tail optimization, etc. Leveraging the unique aspects of both the chemical and biological information of the CAS Content Collection,32 this paper focuses on chemical modifications to the base, backbone, sugar, and 5′ or 3′ ligations to other molecules. While chemical modifications increase RNA stability, complexes of RNA within nanoparticles provide further protection. Except for aptamers that bind to a cell surface target, RNA must be delivered into the cell by a carrier. After the RNA is internalized, it must be released from the membrane-bound vesicle or endosome to the cytosol. Without a doubt, the delivery system has been an important research topic for RNA medicine.

In this paper, we reviewed naturally occurring RNAs with their cellular functions and the associated research trends based on the analysis of CAS Content Collection.32 We then appraised different types of RNA in medical applications: their advantages, challenges, and research trends. Subsequently, we assessed the development pipelines of RNA therapeutics and vaccines with company research focuses, disease categories, development stages and publication trends. Finally, we discussed RNA chemical modifications and delivery systems in detail, as they are critical to the success of RNA medicine. We thus revealed the sustained global effort that propelled this field to the cusp of realization for novel medical applications of RNA in many diseases. We hope this review can serve as an easy-to-understand overview so that scientists from many different disciplines can appreciate the current state of the field of RNA medicine and join in solving the remaining challenges for fulfilling its potential.

Types of Naturally Occurring RNA and Their Functions in Biological Systems

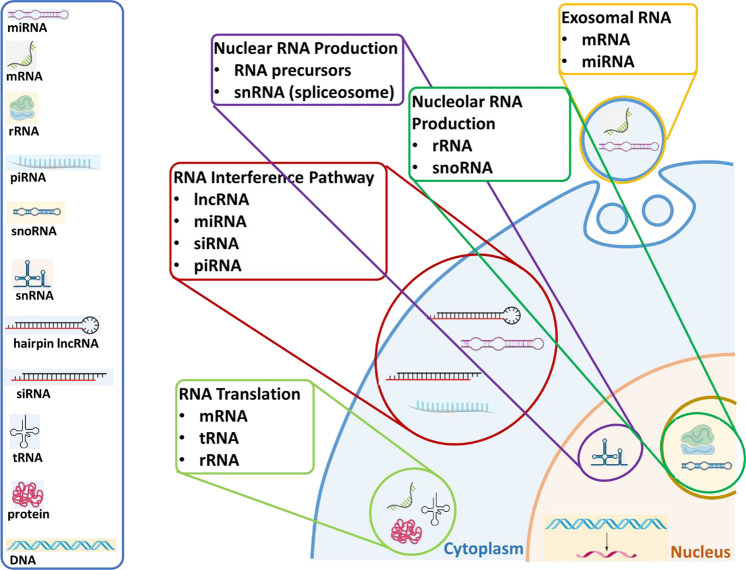

RNA, a versatile macromolecule that is specialized for many functions, can be broadly defined as coding or messenger RNA (mRNA) and non-coding RNA (ncRNA). There are several different types of ncRNA including ribosomal RNA (rRNA),33,34 transfer RNA (tRNA),33,34 small nuclear RNA (snRNA),35−37 small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA),36,38−45 long non-coding RNA (lncRNA),7,46−52 short hairpin RNA (shRNA), micro-RNA (miRNA),53−59 transfer messenger RNA (tmRNA), small interfering RNA (siRNA),60−71 small activating RNA (saRNA), piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA),3,4,72−78 circular RNA (circRNA), ribozymes, and exosomal RNA.79−83 The cellular localizations of different types of RNA are illustrated in Figure 2, and an overview of their functions is provided in the following section.

Figure 2.

Types of naturally occurring RNA and their cellular functions and localizations

Functions of the Naturally Occurring RNA Types

mRNA, which was the first RNA to be characterized, is the initial transcription product of a protein-coding gene and includes both protein-coding exons and non-coding introns. The mature, translatable mRNA must be spliced to remove the introns and, in transcripts that can go through alternative splicing, one or more potential exons. The mature RNA has a 5′-7-methylguanosine cap, a 5′-untranslated region, a start codon (unique sequence of 3 bases) for the translated region of the gene, a stop codon that ends the translated region of the gene and starts the 3′-untranslated region, and a 3′-polyadenosine tail. Gene expression, which is often regulated by the amount of mRNA for the gene, is controlled by the balance between synthesis and degradation of mRNA. Although mRNA is a critically important RNA, it makes up only 1–5% of the RNA in a cell.33,34

ncRNAs, in contrast to mRNA, are the final functional products of the DNA. Although it was thought initially that ncRNAs were non-functional junk RNA, in the 1950s, in the same paper that introduced the phrase “Central Dogma”, Francis Crick correctly hypothesized that the ncRNA might function in the translation of mRNA into protein.84 In 1955, George Palade identified ribosomes as a small particulate component of the cytoplasm that contains RNA, and in 1965, Robert Holley purified a tRNA from yeast and determined the structure.85,86 In the past half-century, many types of ncRNA with various functions have been identified; many are involved in regulating transcription and protein expression in the cell.87−94

rRNA, which constitutes up to 80% of the RNA in an active cell, comprises three rRNAs (the 5S, 5.8S, and 28S) complexed with many proteins to form the large subunit of the ribosome and one rRNA (the 18S) complexed with proteins to form the small subunit of the ribosome. There are also two mitochondrial rRNA genes (the 12S and 16S) which, along with many proteins, form the mitochondrial ribosome. rRNA in the ribosome, acting as a ribozyme, catalyzes peptide bond formation between two amino acids. Synthesis of the large amount of rRNA occurs in the nucleolus, a heterochromatic region found in most nuclei.33,34

tRNA, which makes up 10–15% of the RNA in the cell, translates the mRNA codon sequence for each amino acid. The many different tRNAs, which are usually 75–95 nucleotides, all fold into very similar three-dimensional structures. The 3D structure exposes three unpaired nucleotides that serve as the anti-codon to base pair with the mRNA. Specific amino acids are covalently bound to a tRNA by aminoacyl tRNA synthetases. The specificity between the anti-codon and the bound amino acid is the basis of translation. Each tRNA anticodon can bind to several different mRNA codons. This pairing is based on the wobble rules for the third nucleotide position of the anti-codon, which is often post-transcriptionally modified to allow for wobble-pairing. Common modifications at the third position include 5-methyl-2-thiouridine, 5-methyl-2′-O-methyluridine, 2′-O-methyluridine, 5-methyluridine, 5-hydroxyuridine, hypoxanthine, and lysidine.33,34

snRNAs (∼150 nucleotides) are components of the small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) of the spliceosome. They act as catalysts that splice mRNA into its mature form and they are important in the selection of alternative splicing sequences.35−37

snoRNAs (60–300 nucleotides) are bound to four core proteins and act as guides to correctly target modifications for the maturation of rRNA. They comprise two classes of RNA. C/D snoRNAs participate in the 2-methylation of targeted nucleotides, while H/ACA snoRNAs participate in the modification of uridine to pseudouridine. They help guide the protein to the specific target, rather than catalyzing the reaction directly. As participants in rRNA maturation, snoRNAs are found in the nucleolus.36,38−45

siRNAs are products of double-stranded lncRNAs (e.g., hairpin lncRNA) and are central to RNA interference, which negatively regulates gene expression. Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), either from genomic lncRNA or dsRNA viruses, is recognized and cleaved by the endonuclease Dicer into 20–24 base-pair sections with short overhangs on both ends. These siRNAs bind the Argonaute protein to form the pre-RISC (RNA-induced silencing complex). Argonaute selects the less thermodynamically stable strand of the siRNA and releases the other strand to form the mature RISC. RISC recognizes mRNA complementary to the single-stranded siRNA, and the Argonaute endonuclease cuts this targeted mRNA, thereby downregulating the gene product. The binding of a RISC to a target mRNA also prevents efficient ribosome binding and translation, further downregulating the gene product. Active RISCs may also affect the transcription of target genes by inducing chromatin reorganization through epigenetic modifications. This can be a defense mechanism against dsRNA viruses or an endogenous gene-regulatory mechanism.60−71

miRNAs are closely related to siRNAs but are formed from pri-miRNAs (primary microRNAs), which are long, imperfectly paired hairpin RNA transcripts. The pri-miRNA is processed first by Drosha nuclease into a ∼70-nucleotide imperfectly paired hairpin pre-miRNA (precursor microRNA) that is then, like siRNA, processed by Dicer to produce the 21–23-bp, mature, double-stranded miRNA that binds to Argonaute to form the RISC. Alternatively, some miRNAs are made from introns in mRNAs. After splicing, that intron is a pre-miRNA that is processed by Dicer to form a RISC. miRNAs form negative gene regulatory networks and intronic miRNAs may regulate and balance potentially competing pathways.53−59

piRNAs, like siRNA and miRNA, negatively regulate gene expression, but they interact with the Piwi class of Argonaute proteins. Unlike siRNA and miRNA, piRNAs (24–31 nucleotides) are produced from long, single-stranded RNA transcripts through an uncharacterized Dicer-independent mechanism. Mature piRNAs bind to Piwi proteins to form RISCs that act primarily as epigenetic regulators of transposons (genetic elements that move around the genome) but may also regulate transposons post-transcriptionally through the ping-pong pathway.3,4,72−78

saRNA, like siRNA, is a ∼21-bp dsRNA long that interacts with Argonaute proteins to form a RISC. Unlike siRNA, saRNA upregulates target gene expression by an unknown mechanism, perhaps activating transcription by targeting the promoter region of the gene. saRNA may be produced endogenously or artificially to strongly activate the target gene.5,95−101

lncRNAs comprise a mixed group of RNAs >200 bp, which differentiates them from short ncRNAs such as snoRNA, siRNA, miRNA, piRNA, etc. lncRNAs have a wide variety of functions including regulation of chromosome architecture and interactions, chromatin remodeling, and positive or negative regulation of transcription, nuclear body architecture, and mRNA stability and turnover.7,46−52

circRNAs are lncRNAs with 5′ and 3′ ends linked covalently to form a continuous circle. circRNAs are broadly expressed in mammalian cells and have shown cell-type and tissue-specific expression patterns.102 Neither the mechanisms leading to circularization of the RNA nor the function of circRNA is known, but the leading hypothesis is that they may serve as miRNA sponges. Many circRNAs contain large numbers of miRNA target sites that may competitively antagonize the ability of miRNA to silence its target genes.

Exosomal RNAs are mRNAs, miRNAs, siRNAs, and lncRNAs that are packaged and exported from the cell through the exosomal pathway. Although they are poorly understood, exosomal RNAs may serve as signaling molecules to regulate gene expression in target cells. These circulating RNAs, especially miRNAs, may serve as diagnostic and/or prognostic targets for various diseases such as cancers.79−83

Antisense RNA (asRNA), also referred to as antisense oligonucleotide (ASO), is a single-stranded RNA that is complementary to a protein-coding messenger RNA (mRNA) with which it hybridizes, and thereby blocks its translation into protein.103

Research Trends on Different Types of RNA As Reflected by Number of Publications

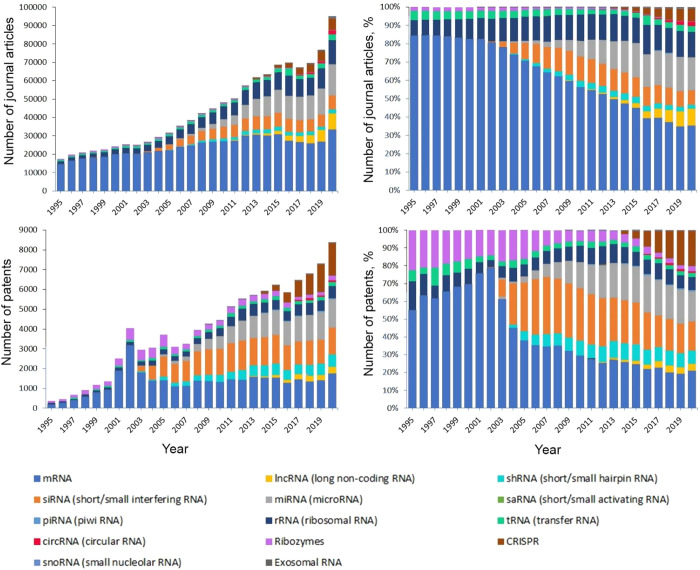

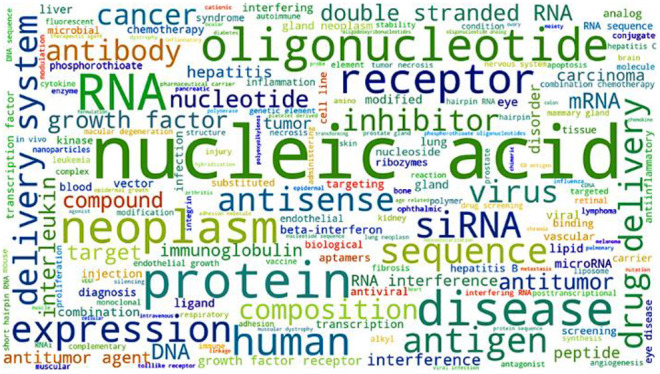

The CAS Content Collection32 is the largest human-curated collection of published scientific knowledge, used for quantitative analysis of global scientific publications against variables such as time, research area, formulation, application, disease association, and chemical composition. We searched the title, abstract, or CAS-indexed terms using RNA-related keywords and their synonyms to identify relevant published documents. Figure 3 shows trends in the number of publications for specific types of RNA. In the past 25 years, the research areas became more diverse as new types of RNA were discovered, and this is reflected in both journal and patent publications, particularly in the areas of siRNA, miRNA, lncRNA, and CRISPR-related research. CRISPR technology has recently increased rapidly in volume of patent publications, and it accounted for 20% of the RNA-related patent publications in 2020.

Figure 3.

Document publication trends for different types of RNA from 1995 to 2020 as found from the CAS Content Collection.32 Top two panels: journal publications in absolute numbers and given year percentages. Bottom two panels: patent publications (counted once per patent family) in absolute numbers and given year percentages.

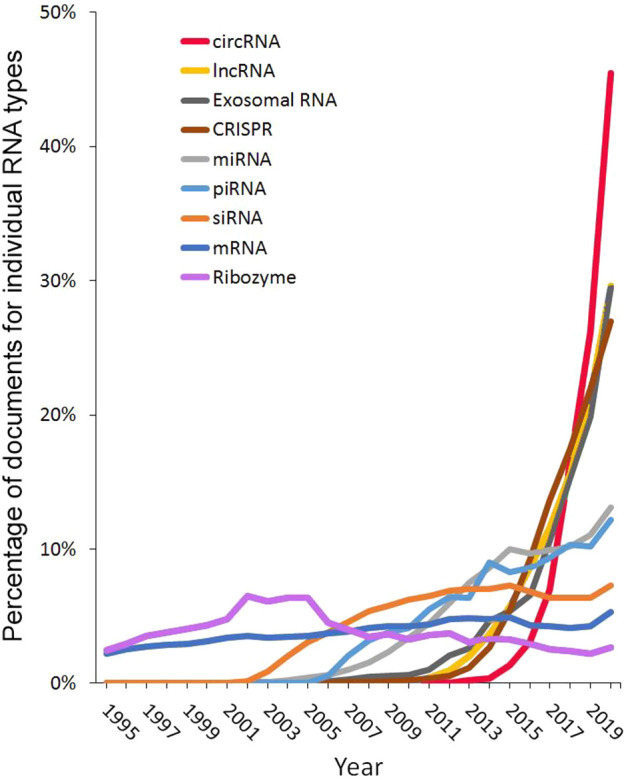

To better reveal the rising trends of those recently emerged types of RNA, the percentage of document publications of a specific year was calculated within the given type of RNA over the time (Figure 4). Although the cumulative publication numbers for circRNA, exosomal RNA, lncRNA, and CRISPR, are relatively small compared with others (Figure 3), their rates of increase are much faster.

Figure 4.

Trends in publication volume for different RNA types in the years 1995–2020. Percentages are calculated with yearly publication numbers for each individual RNA type, normalized by total publications in the years 1995–2020 for the same RNA type. Example: Percentage of circRNA documents in 2020 = (number of circRNA documents in 2020)/(total number of circRNA documents from 1995 to 2020).

Types of RNA Used in Medical Applications, Their Advantages, and Challenges

Types of RNAs and Their Applications in Medicine

mRNA transcripts can act as therapeutic RNAs, diagnostic biomarkers, or therapeutic targets. Translation of an mRNA in the cell can produce a therapeutic protein to replace a defective or missing protein. In the case of vaccines, mRNA translation can generate antigenic targets for the immune system, such as the spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 in the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. mRNA may also serve as a therapeutic target for ASOs, siRNA, miRNA, aptamers, and suppressor tRNAs.

In the cell, miRNAs bind to the 3′-untranslated region of mRNAs and target them for degradation by the RISC.104 Because a single miRNA binds to multiple mRNAs, miRNAs serve as regulatory check points. The cellular processes regulated by miRNAs include those involved in many diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and disease-related metabolic pathways.105,106 Thus, they can serve as biomarkers for disease diagnosis, as potential drugs, or as attractive targets for other regulatory RNAs.

Although siRNAs, like miRNAs, use the RISC to degrade their target mRNAs, siRNAs bind to specific areas in the mRNA coding region. This target specificity makes them attractive as potential drugs, but off-target effects can negate this advantage. In order to minimize off-target effects, siRNAs are modified to decrease their thermal stability, increase their target specificity, and decrease the stability of their binding of the siRNA to mRNAs that are not an exact match to the intended target mRNA. These usually include 2′-O-methyl and 2′-MOE ribose modifications that introduce steric hindrance to decrease binding affinity (more discussion in the Chemical Modifications section below).104

One of the earliest therapeutic RNAs, ASOs, recognize and bind to complementary DNA or RNA sequences, including mutated sequences that may lead to disease. Upon binding to the mutated sequences, ASOs may facilitate proper mRNA splicing, prevent translation of a defective protein, or target RNAs for degradation.104

In therapeutic antibody–oligonucleotide conjugates (AOCs), the antibody targets the site of interest while carrying an ASO or a siRNA that acts on the targeted region.107 Conjugation of an ASO to an antibody to create an AOC improves the pharmacokinetics of the ASO in vivo by increasing tissue distribution and prolonging gene silencing in multiple tissues.108

The CRISPR-Cas system uses a guide RNA that is either a combination of a trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA) and a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) or a joined single guide RNA (sgRNA). The guide RNA directs the CRISPR complex containing a Cas endonuclease to a specific site in the genome for cleavage.6 The ability of the CRISPR-Cas system to create directed double-stranded breaks in DNA allows the repair of genetic mutations. Changing the endonuclease activity of Cas can convert CRISPR-Cas to a system that nicks a single strand of the DNA or that deaminates a specific nucleotide.109 If the Cas endonuclease is inactivated, the system can simply bind to DNA to regulate transcription.104

Aptamers are structure-based rather than sequence-based ligands that neither hybridize with other nucleic acids nor produce proteins. They can be RNA, DNA, RNA/DNA combinations, or even proteins. In vitro systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) is used to identify single-stranded RNA or DNA oligonucleotides with a high affinity for a target. Because their binding depends on their 3D structure, aptamers can bind a wide range of targets, including proteins, cells, microorganisms, chemical compounds, and other nucleic acids.110 Aptamers may also serve as delivery agents for siRNA in nanoparticles for cancer therapy.111

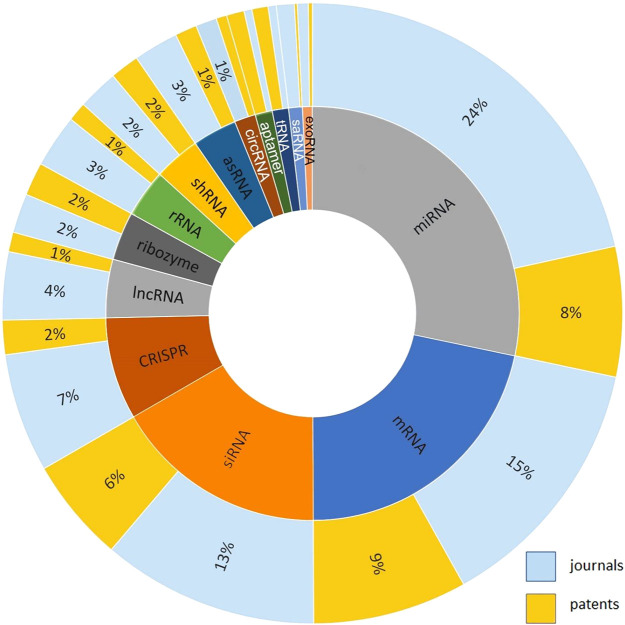

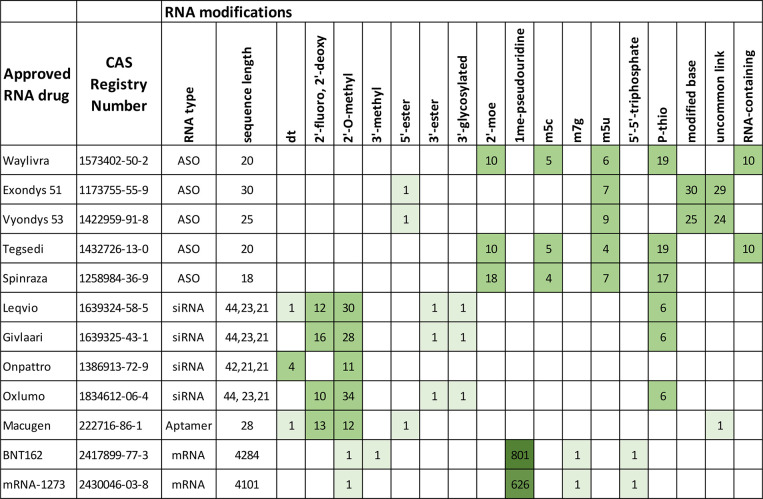

To measure the distribution of research effort using different types of RNA as therapeutics, vaccines, or diagnostics, related documents were extracted accordingly from the CAS Content Collection, and journal and patent publications percentages for each type of RNA were determined as shown in Figure 6.32 miRNA and mRNA, the two most popular therapeutic RNAs in the journal and patent literature, can serve as drugs, disease biomarkers, and drug targets. Together with siRNA, they represent most of the therapeutic RNA patent activity. Approved RNA drugs include mRNAs, siRNAs, ASOs, and aptamers; these RNAs along with CRISPR RNAs and AOCs comprise most of the clinical candidates.

Figure 6.

Percentage of journal documents and patents for various types of RNA used in medical studies including therapeutics, vaccines, and diagnostics.

Publication Trends for RNAs Used in Medical Applications

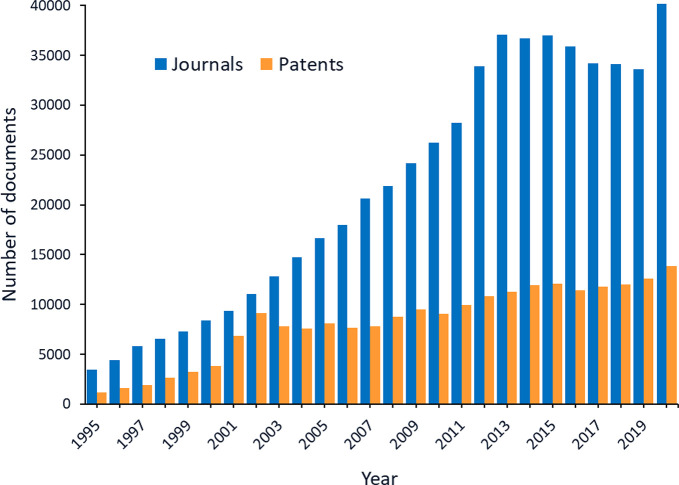

The CAS Content Collection32 shows a steady increase in the number of journal articles and patents related to RNA applications in medicine (Figure 5). The peak in patents in 2001–2002 may correlate with the first clinical trials using dendritic cells transfected with mRNA encoding tumor antigens (a therapeutic mRNA cancer vaccine) in 2001.112,113 The spike in journal article numbers in 2020 likely resulted from interest in the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. The increase in journal articles and patents on therapeutic RNA from 2011 to 2016 can be attributed to initial interest in siRNA and miRNA, which decreased temporarily with the discovery of their off-target effects. Interest in mRNA also increased from 2011 to 2016, then decreased and only recovered once mRNA vaccines took center stage in the fight against COVID-19.

Figure 5.

Numbers of journal documents and patents related to RNAs for medical use by year.

However, other types of RNA are potential therapeutics or targets. These RNAs include (a) shRNA; (b) lncRNA, an RNA whose role in gene regulation is generating increasing interest; (c) circRNA, once thought to be a byproduct of RNA splicing, that may have a role in regulation as a miRNA sponge; (d) saRNA, which regulates gene transcription; and (e) exosomal RNA, which is contained in naturally occurring lipid vesicles called exosomes, which can cross the blood-brain barrier and appear to be vital for cell-to-cell communication, and which transport mainly miRNA.114

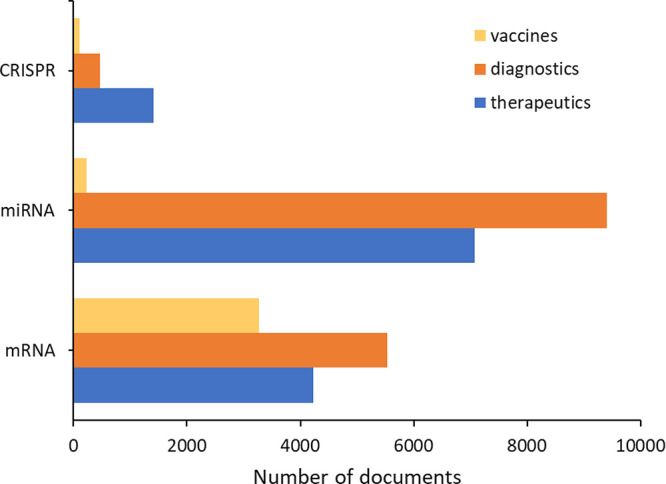

Based on the CAS Content Collection data for CRISPR RNA, miRNA, and mRNA used in vaccines, diagnostics, and therapeutics,32 only mRNA has substantial applications in vaccines (Figure 7). However, both miRNA and mRNA have demonstrated their potential as therapeutics and diagnostics.

Figure 7.

Number of journal publications and patents for mRNA, miRNA, and CRISPR with applications in therapeutics, vaccines, and diagnostics.

The large body of work on miRNA and mRNA in diagnostics may be surprising since these molecules are much more susceptible to nuclease degradation than DNA. However, the essential roles of mRNA and miRNA in cellular metabolism make them excellent biomarkers for the study of normal cellular processes and the diagnosis of disease. Metabolic diseases such as cancer as well as infectious diseases can be diagnosed via miRNA biomarkers by reverse transcriptase-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) and lateral flow immunoassays.115,116 High-throughput sequencing of total cellular mRNA pinpoints changes in gene expression that can be used in diagnosis.117 The specificity of the CRISPR system for its target DNA makes it a potential tool with both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.118 The number of journal publications and patents using RNA for diagnosis demonstrates its power (Figure 7); however, a comprehensive review of RNA as a diagnostic biomarker or, in the case of CRISPR RNA, as a diagnostic agent, is beyond the scope of this review. Here we focus on RNAs as therapeutic agents.

Advantages and Challenges of RNAs as Therapeutics

There are several important advantages to RNA therapeutics. They are: (a) target specific, (b) modular with easy-to-switch sequences, (c) predictable in terms of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, (d) economical in comparison to antibodies or protein drugs since they are synthesized from widely available synthons on an automated synthesizer, and (e) relatively safe, as most of them do not alter the genome.

Proteins must be designed for synthesis from genes in plasmids, then optimized for expression and purification, and these processes may be different for each protein and challenging to optimize. In contrast, RNA can be easily synthesized and purified by established methods using commercially available reagents and equipment. Small RNAs, such as aptamers, siRNAs, miRNAs, and ASOs can be synthesized using solid-support chemistry in commercial oligonucleotide synthesizers.119,120In vitro transcription using commercial kits121 produces longer RNAs, i.e., mRNAs and lncRNAs. The sequence of the RNA can be changed easily, providing custom molecules targeting different proteins or genes. Thus, the development of RNA therapeutics and vaccines that target disease-specific genes or proteins is relatively fast and straightforward. This was demonstrated by the development, testing, and administration of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines within a year of the isolation and sequencing of the SARS-CoV-2 viral genome.108

Most RNAs regulate transcription, post-transcriptional processing, and translation, but they do not alter the genome. The exception is the CRISPR-Cas system in which the guide RNA and Cas endonuclease can edit the genome. RNA aptamers, which mimic ligands, regulate post-translational protein activity. The rapid degradation and predictable pharmacokinetics of RNAs give them a safety advantage over gene therapies.104

Despite the attractiveness of the plug-and-play concept of RNA therapeutic drug design, they require testing to determine their efficacy and safety, and cell delivery is difficult because RNA is easily degraded. The therapeutic RNA must penetrate the cell membrane and escape endosomal entrapment.104 Although designed for specific targets, therapeutic RNAs can have off-target effects, limiting their usefulness as drugs. Several of these limitations can be mitigated by chemically modifying the RNA to increase target specificity, lower nuclease susceptibility, and improve cellular uptake.104,108

Types of RNA in Medicine in the Development Pipeline and Their Targeted Diseases

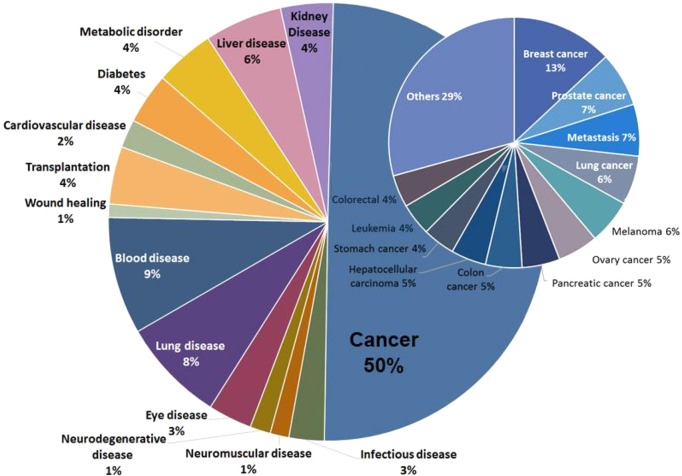

Distribution of Diseases Associated with RNA Medicine in Publications and Patents

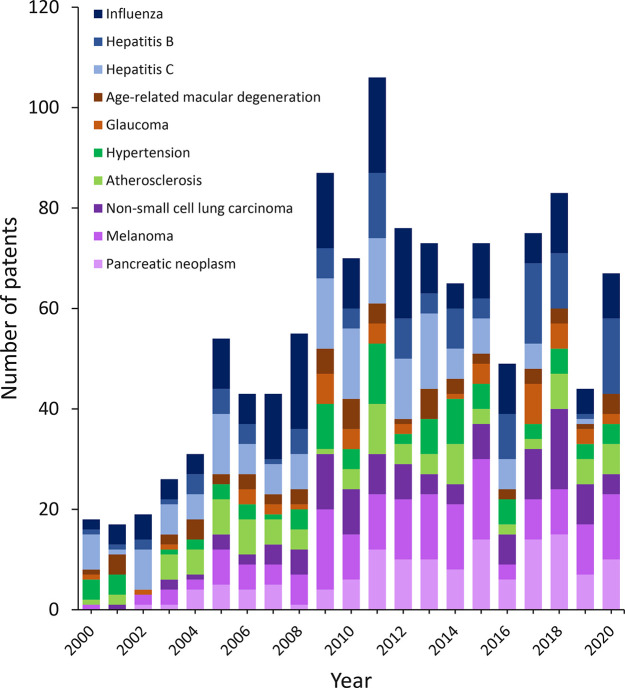

Since the first approved ASO RNA therapeutic in 1998, the research and development of RNA in medical applications has increased. We analyzed data from the CAS Content Collection32 for journal publications and patents on RNAs as therapeutics, vaccines, or diagnostic agents for diseases and found that 50% of the publications are associated with cancer diagnosis or treatment, although lung, liver, and metabolic diseases are also highly represented (Figure 8). There was little correlation between the type of RNA and a targeted disease, indicating that different types of RNA have been explored for many kinds of diseases in the research phase (Figure S1). Infectious diseases and cancer have shown the greatest growth and are the most frequent diseases treated by RNA, followed by eye and cardiovascular diseases, which grew in the first decade of this century and remained relatively stable in the second decade (Figure 9). Specifically, the association of RNA medicine with pancreatic neoplasm, melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer, hepatitis B, and influenza has increased quickly in the past 20 years. Patent publications for RNA therapeutics for hepatitis C have decreased in recent years, most likely due to the approval of several effective small molecule drugs for hepatitis C. RNA therapeutics for atherosclerosis, hypertension, glaucoma, and age-related macular degeneration research have remained relatively stable. The top 20 patent assignees for patent publications on RNA therapeutics, vaccines, or diagnostics are mostly in the U.S. or China, although a few are in Germany, Korea, Japan, Switzerland, or Israel (Figure 10).

Figure 8.

Percentage of publications associated with RNAs in medical applications

Figure 9.

Yearly number of patent publications on specific diseases targeted by RNA therapeutics, vaccines, and diagnostics.

Figure 10.

Top patent assignees for RNA therapeutics, vaccines, and diagnostics.

Pipeline Dynamics of RNAs for Therapeutics and Vaccines

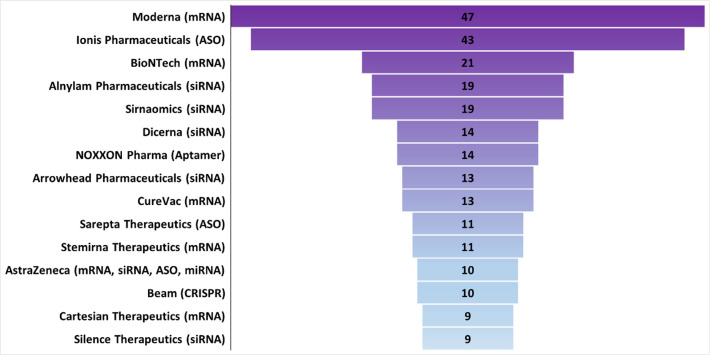

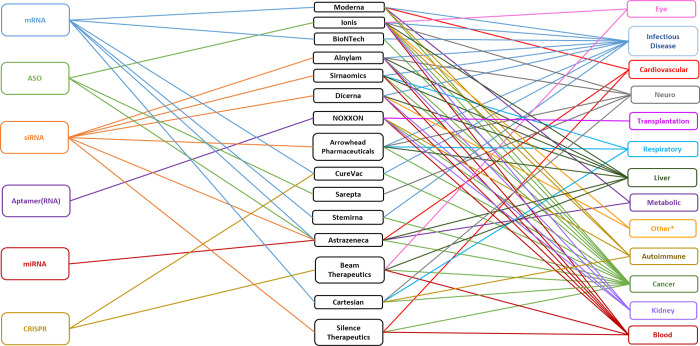

After decades of extensive research, the therapeutic potential of RNAs has led to the development of over 250 therapeutics that are approved or in development (Table S2). Among the top 15 RNA therapeutics companies (Figure 11), which are located worldwide (Figure S2), each mostly focuses on one type of RNA to develop novel RNA therapeutics for treating diseases that range from very rare to common. mRNA and siRNA are the most common RNAs used by the top 15 companies, followed by ASO, CRISPR, and aptamers. Many of these companies are among the top patent assignees for RNA therapeutics, vaccines, and diagnostics in the commercial sector (Figure 10).

Figure 11.

Top pharmaceutical companies ranked by the number of RNA therapeutic and vaccine agents in the development pipeline. Counts include RNA agents in company-announced pre-clinical development, in clinical trials, or approved. A single RNA agent can be counted multiple times when applied to multiple diseases.

Moderna, BioNTech, CureVac, Stemirna Therapeutics, and Cartesian Therapeutics specialize in mRNA related therapeutics or vaccines. Moderna, headquartered in Massachusetts, USA,122 leads this group with over 45 therapeutics in its pipeline (Figure 11) and 131 RNA therapeutic/diagnostic patents (Figure 10). BioNTech and CureVac are both headquartered in Germany.123,124 BioNTech has in its pipeline 21 therapeutics that utilize the immune system to treat cancer and infectious diseases (Figure 11).123 CureVac has 13 therapeutics (Figure 11) along with 76 RNA therapeutic/diagnostic patents (Figure 10) for mRNA medicines.124 Stemirna Therapeutics headquartered in China,125 has a pipeline of 11 mRNA-based therapeutics (Figure 11). Cartesian Therapeutics, headquartered in Maryland, USA,126 has 9 therapeutics and is a pioneer in using mRNA for cell therapies within and beyond oncology, with products in development for autoimmune and respiratory disorders (Figure 11).

Alnylam, Sirnaomics, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, Silence Therapeutics, and Dicerna develop siRNAs for their RNA therapeutics. (Effective December 28, 2021, Dicerna is a wholly owned subsidiary of Novo Nordisk. In this paper Dicerna is considered separately.) Alnylam Pharmaceuticals and Dicerna are headquartered in Massachusetts, USA.127,128 Alnylam is the leader in siRNA therapy with over 19 therapeutics in their pipeline and 77 therapeutic/diagnostic patents (Figure 11). Dicerna treats both rare and common diseases with its 14 therapeutics (Figure 11). Sirnaomics, headquartered in Maryland, USA, has developed over 19 therapies for human diseases that have no treatments.129 Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, headquartered in California, USA,130 treats previously intractable diseases with their 13 therapeutics (Figure 11). Silence Therapeutics, headquartered in London, UK,131 has 9 therapeutics (Figure 11).

Ionis Pharmaceuticals and Sarepta Therapeutics use ASOs for their RNA therapeutics. Ionis Pharmaceuticals is headquartered in California, USA,132 and Sarepta Therapeutics in Massachusetts, USA.133 Ionis has developed over 40 therapeutics (Figure 11) and 115 therapeutic/diagnostic patents (Figure 10). Sarepta uses antisense technology to target neurological diseases, including neuromuscular and neurodegenerative disease, with their 11 therapeutics (Figure 11).

NOXXON Pharma, headquartered in Germany, uses RNA aptamers for their 14 therapeutics (Figure 11).134 Their current pipeline is focused only on oncology, but previously they researched treatments for transplantation, metabolic, blood, autoimmune, and kidney diseases (Figure 12). Beam Therapeutics, headquartered in Massachusetts, USA,135 is pioneering the use of base editing with CRISPR-Cas. Beam has 10 therapeutics in development (Figure 11). AstraZeneca supports multiple RNA platforms through partnerships with many of the top RNA companies.136

Figure 12.

Types of RNA by company and targeted diseases. *Other: acromegaly, hereditary angioedema, and alcohol use disorder.

All but two of the top 15 RNA medicine companies specialize in one type of RNA (Figure 12). AstraZeneca supports multiple RNA platforms and CureVac is partnering with CRISPR Therapeutics for their current pre-clinical CRISPR RNA therapy137 along with their mRNA therapy. Companies typically specialize in one type of RNA but treat multiple diseases. All but two of the top 15 RNA medicine companies cover multiple diseases. Sarepta specializes in neurological and neuromuscular diseases and NOXXON has supported multiple diseases in the past (Figure 12) but is now dedicated exclusively to the treatment of cancer.

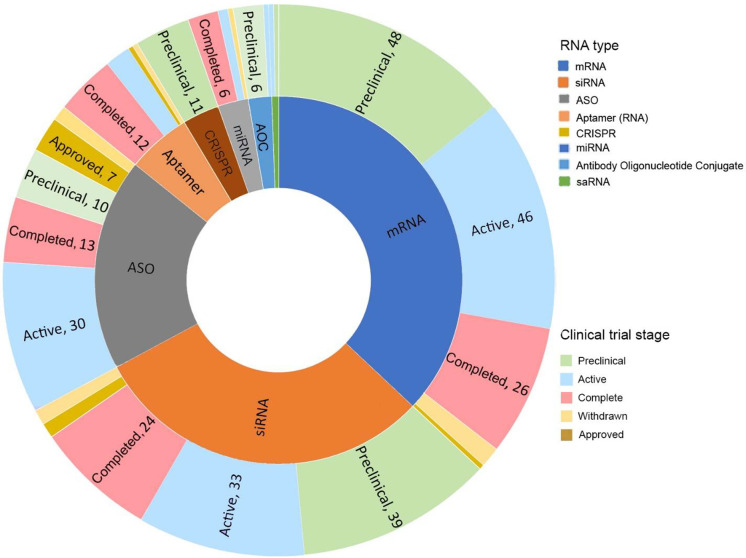

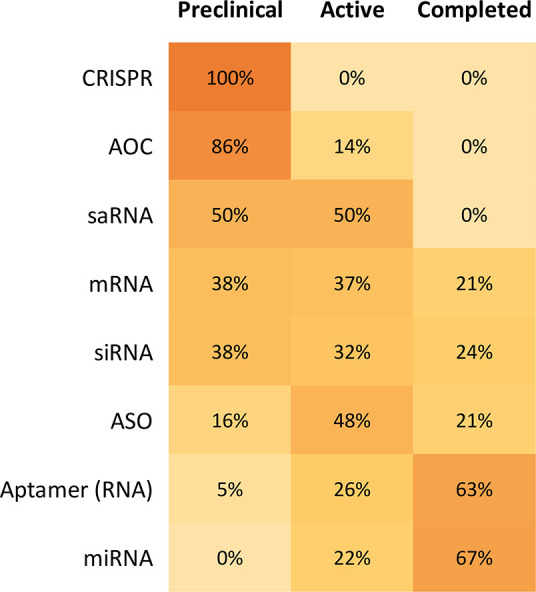

To investigate the research trends among different types of RNA therapeutics, the collected RNA therapeutics were further grouped by their types and development stages (Figures 13 and 14). The newer RNA therapeutics, such as AOCs and CRISPR, often have higher numbers of pre-clinical trials, indicating a great potential for future drug approval. In contrast, the more established types of RNA therapeutics, such as ASO and siRNA, often have a higher percentage of therapeutics on the market and a higher percentage of active and completed clinical trials, suggesting a shifting of research focus on the early development pipeline.

Figure 13.

Counts of potential therapeutics and vaccines in different stages of development (pre-clinical, clinical, completed, withdrawn, and approved) for the various types of RNA. A full list of collected clinical trials is provided in Table S2.

Figure 14.

Percentage of pre-clinical, active, and completed clinical trials by RNA type. Figure rows may not sum to 100% because approved and withdrawn clinical trials are not included in this figure.

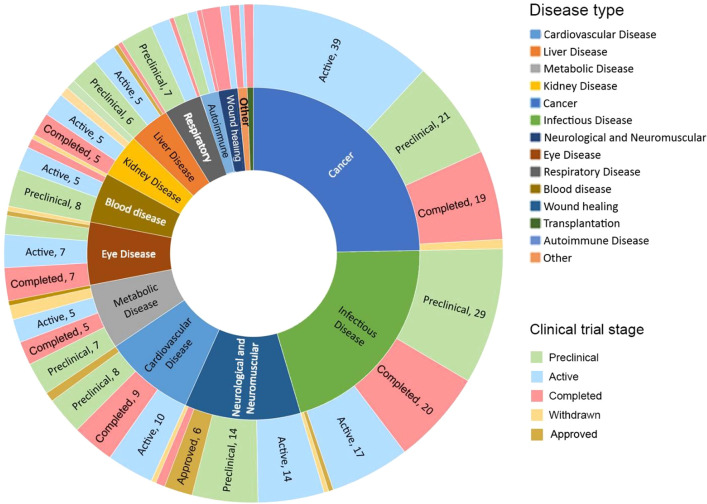

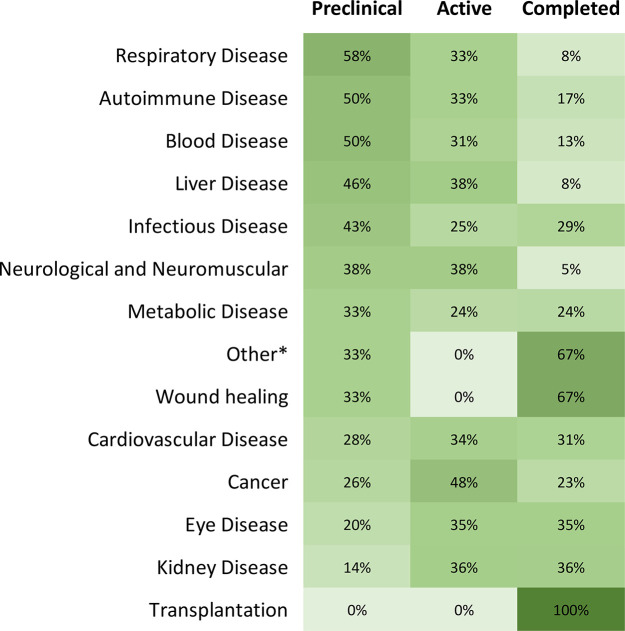

Disease-Specific RNA Therapeutics and Vaccines

To further assess the pipeline dynamics, the above collected RNA therapeutics (Table S2) were then categorized based on their targeting diseases and development status (Figure 15). Cancer has attracted the highest number of therapeutics and vaccines in the research phase, with infectious diseases in second place. Neurological and neuromuscular diseases have the most approved treatments on the market, followed by cardiovascular and infectious diseases. The COVID-19 pandemic quickly catapulted RNA therapeutics for infectious diseases in both the research phase and approved vaccines to the forefront. While diseases such as familial hypercholesterolemia and DMD have approved RNA therapeutics, blood diseases, cancers, and respiratory diseases currently do not have any approved RNA treatments. Respiratory disease, autoimmune disease, and blood diseases have the highest percentage of therapeutics in pre-clinical trials but so far have no approved treatments. Figure 16 shows the percentages of RNA therapeutics in various development stages based on disease type, revealing places with high activities, as well as places needing more attention.

Figure 15.

Counts of potential therapeutics and vaccines in different development stages (pre-clinical, clinical, completed, withdrawn, and approved) for various disease types. A full list of collected clinical trials is provided in Table S2.

Figure 16.

Percentage of pre-clinical, active, and completed clinical trials by disease type. Figure rows may not sum to 100% because approved and withdrawn clinical trials are not included in this figure. *Other: acromegaly, alcohol use disorder, and hereditary angioedema.

Disease types along with their RNA therapeutics are examined and summarized below (Tables 1–11). These tables and corresponding text are not exhaustive and highlight promising therapeutics in the development stages from the collected RNA therapeutics (Table S2).

Table 1. RNA Therapies for Cardiovascular Diseases.

| cardiovascular disease | drug name/lab code | type of RNA | target | company | development stage | clinical trial number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| familial hypercholesterolemia | Leqvio | siRNA | proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 | Alnylam/Novartis | FDA approval in 2021139 | |

| cardiovascular disease with high LpA | SLN360 | siRNA | lipoprotein A | Silence Therapeutics | phase I | NCT04606602141 |

| hypertension | Zilebesiran | siRNA | angiotensinogen | Alnylam | phase I | NCT03934307147 |

| ischemic heart disease | AZD8601 | mRNA | vascular endothelial growth factor-A | Moderna/AstraZeneca | phase II | NCT03370887148 |

Table 11. RNA Therapies for Other Diseases.

| other disease | drug name/lab code | type of RNA | target | company | development stage | clinical trial number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| keloid scarring | STP705 | siRNA | transforming growth factor beta 1/cyclooxygenase-2 | Sirnaomics | phase II | NCT04844840244 |

| autoimmune diseases | mRNA-6231 | mRNA | interleukin-2 | Moderna | phase I | NCT04916431251 |

| alcohol use disorder | DCR-AUD | siRNA | aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 | Dicerna Pharmaceuticals | phase I | NCT05021640252 |

Cardiovascular diseases, which account for 32% of all deaths, are the leading cause of death worldwide, taking an estimated 17.9 million lives each year.138 Cardiovascular diseases include disorders of the heart and blood vessels. Over 80% of cardiovascular disease deaths are due to heart attacks and strokes, and one-third of these deaths occur prematurely in people under 70 years of age.138

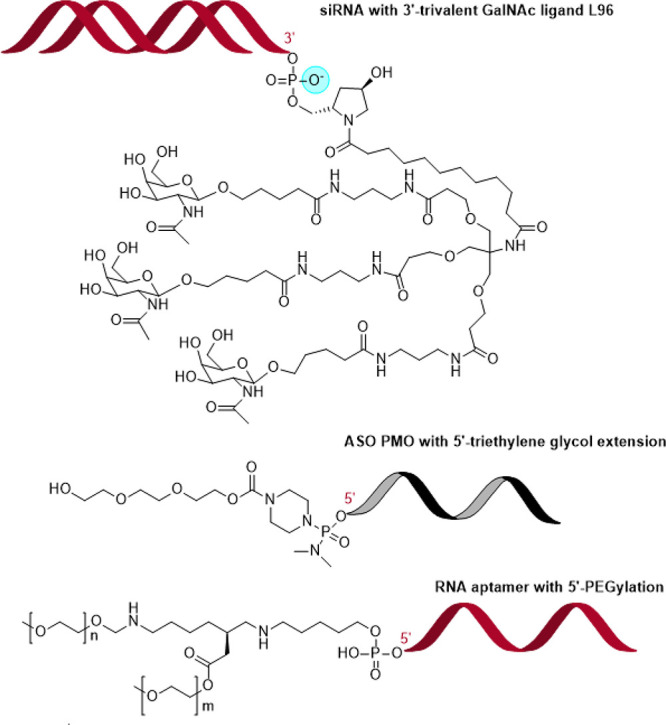

Leqvio is an approved therapeutic for the treatment of the cardiovascular disease, familial hypercholesterolemia (Table 1). Leqvio requires only two doses per year, and it received US FDA approval very recently in December 2021.139 It is a trivalent N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc)-conjugated siRNA with three GalNAc molecules clustered and conjugated to one siRNA molecule.140

In addition to this approved one, there are several more promising RNA therapeutics for cardiovascular diseases currently in the clinical trial stages (Table 1). Silence Therapeutics is evaluating the siRNA product SLN360 in a phase I clinical trial for its safety, tolerance, and pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic response in individuals with high lipoprotein A (LpA) cardiovascular disease.141 By targeting the LPA gene, SLN360 lowers the levels of LpA, decreasing the risk of heart disease, heart attacks, and strokes.131 Alnylam is also evaluating the siRNA product Zilebesiran that targets angiotensinogen for sustained reduction of hypertension.142 Interim phase I results show >90% reduction in serum angiotensinogen (AGT) for 12 weeks at a dosage of 100 mg or greater given quarterly or biannually.143 This dosing regimen and the continued efficacy and safety of the drug are being evaluated in a phase II study initiated in June 2021 (NCT04936035).143 Zilebesiran also uses Alnylam’s trivalent GalNAc-conjugated siRNA delivery platform.140 AstraZeneca and Moderna are collaborating on the mRNA drug AZD8601 to treat ischemic heart disease.144 AZD8601 targets vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A).145 When AZD8601 is injected into the epicardium, VEGF-A is produced close to the damaged heart muscle, allowing cardiac regeneration.146

Metabolic diseases affect over a billion people worldwide by causing too much or too little of essential substances in the body.149 Diabetes alone affects 422 million people worldwide, causing 1.5 million deaths annually.150 IONIS-GCGRRx is an ASO product developed by Ionis Pharmaceuticals that treats diabetes by reducing the production of the glucagon receptor (GCGR) (Table 2).151 Glucagon is a hormone that opposes the action of insulin and stimulates the liver to produce glucose, particularly in patients with type-2 diabetes.152 Waylivra, another ASO product by Ionis Pharmaceuticals targeting apolipoprotein C-III (apoC-III), received European Union (EU) approval in 2019 as a treatment for familial chylomicronemia syndrome (FCS) (Table 2).153 FCS is a disease that prevents the body from breaking down consumed triglycerides. ApoC-III protein, which is produced in the liver, regulates plasma triglyceride levels in FCS patients, and Waylivra (volanesorsen) reduces its mean plasma levels.154

Table 2. RNA Therapies for Metabolic Diseases.

| metabolic disease | drug name/lab code | type of RNA | target | company | development stage | clinical trial number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| diabetes | IONIS-GCGRRx | ASO | glucagon receptor GCGR | Ionis Pharmaceuticals | phase II | NCT01885260161 |

| familial chylomicronemia syndrome | Waylivra | ASO | apolipoprotein C-III | Ionis Pharmaceuticals | EU approval in 2019153 | |

| alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency | ARO-AAT | siRNA | mutant of α1-antitrypsin | Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals | phase II | NCT03946449162 |

| alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency | unnamed | CRISPR | precise correction of E342K mutation | Beam Therapeutics | pre-clinical157 | |

| methylmalonic acidemia | mRNA-3705 | mRNA | mitochondrial enzyme methylmalonic-CoA mutase | Moderna | phase I/II | NCT04899310163 |

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD) is a hereditary metabolic disease. Alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) is a glycoprotein produced in the liver that travels through the bloodstream to protect the lungs from inflammation.155 Mutations in the SERPINA1 gene cause a deficiency of AAT in the blood, leading to toxic effects in the lungs and the accumulation of high levels of AAT in the liver that cause liver damage.155 ARO-ATT, a siRNA product developed by Arrowhead Pharmaceutical, targets the SERPINA1 mutation, and in pre-clinical studies has shown promise in reducing AAT liver disease (Table 2).156 Beam Therapeutics is developing a CRISPR base editing drug to treat AATD by correcting the E342 K mutation in the SERPINA1 gene.157 Beam’s base editor has two main components, a CRISPR protein bound to a guide RNA and a base editing enzyme, which are fused to form a single protein.158 This fusion allows the precise targeting and editing of a single base pair of DNA, which has not been previously achieved.158 Repairing the mutation would restore normal gene function and eliminate abnormal AAT production. This editing system uses a non-viral lipid nanoparticle delivery system.157

Methylmalonic acidemia (MMA) is a hereditary metabolic disease in which the body is unable to metabolize certain proteins and lipids correctly.159 MMA is caused by mutations in the MMUT, MMAA, MMAB, MMADHC, and MCEE genes. The mutation in the MMUT gene accounts for about 60% of MMA cases. Moderna has developed an mRNA therapeutic mRNA-3705 that targets the MMUT mutation (Table 2).144 mRNA-3705 instructs the cell to restore the missing or dysfunctional proteins that cause MMA. mRNA-3705 entered clinical trials with the first patient treated in August 2021.160

Liver diseases affect more than 1.5 billion people worldwide164 and account for over 2 million deaths per year.165 The siRNA therapeutic GIVLAARI, developed by Alnylam, received FDA approval in 2019 for the treatment of acute hepatic porphyria (Table 3).142 Acute hepatic porphyria is a genetic disease characterized by life-threatening acute attacks and chronic pain.166 GIVLAARI is the first approved GalNAc-conjugated RNA therapeutic.167

Table 3. RNA Therapies for Liver Diseases.

| liver disease | drug name/lab code | type of RNA | target | company | development stage | clinical trial number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| acute hepatic porphyria | GIVLAARI | siRNA | 5-aminolevulinic acid synthase 1 mRNA | Alnylam | FDA approval in 2019170 | |

| non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | ION839/AZD2693 | ASO | patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 | Ionis/AstraZeneca | phase I | NCT04483947168 |

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is an accumulation of fat in the liver that causes liver damage. The antisense therapeutic ION839/AZD2693 from Ionis/AstraZeneca entered phase I trials (Table 3) in 2020 in patients with NASH and fibrosis.168 ION839/AZD2693 targets patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 (PNPLA3), reducing its expression.151 Mutation of PNPLA3, which produces a protein that accumulates on the surface of intracellular lipid droplets, is strongly associated with an increased risk for NASH.169

Cancer includes a large group of diseases that are characterized by abnormal cell growth in various parts of the body. It is the second leading cause of death globally, accounting for an estimated 10 million deaths per year with over 19 million new cases diagnosed in 2020.171 Currently there are no approved RNA therapeutics for cancer treatment. NOXXON Pharma’s lead aptamer candidate NOX-A12 is in development as a combination therapy for multiple types of cancers (Table 4).172 It is intended to enhance other anti-cancer treatments without side effects. A phase I/II trial of NOX-A12 in combination with radiotherapy in newly diagnosed brain cancer patients who would not benefit from standard chemotherapy is ongoing.172 Interim data from the study in June 2021 showed tumor reduction in five of six patients, consistent with an anti-cancer immune response, and there were no unexpected adverse events.172 NOXXON is collaborating with Merck in their pancreatic cancer program.172 NOXXON, in a phase I/II combination trial with Merck’s Keytruda, reported success in treating metastatic pancreatic and colorectal cancer and entered a second collaboration with Merck to conduct a phase II study in pancreatic cancer patients.173 NOX-A12 targets C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12),172 which, with its receptors, acts as a link between tumor cells and their environment, promotes tumor proliferation, new blood vessel formation, and metastases, and inhibits cell death.174

Table 4. RNA Therapies for Cancers.

| cancer | drug name/lab code | type of RNA | target | company | development stage | clinical trial number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| brain cancer/glioblastoma | NOX-A12 | aptamer (RNA) | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 | NOXXON Pharma | phase I/II | NCT04121455179 |

| pancreatic cancer | NOX-A12 | aptamer (RNA) | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 | NOXXON Pharma | phase II | NCT04901741180 |

| solid tumor | STP707 | siRNA | transforming growth factor beta, cyclooxygenase-2 | Sirnaomics | phase I | NCT05037149181 |

| multiple myeloma | Descartes-11 | mRNA | B-cell maturation antigen | Cartesian Therapeutics | phase I/II | NCT03994705182 |

The anti-cancer siRNA product, STP707 by Sirnaomics,175 targets TGF-β1 and COX-2 mRNAs (Table 4). A pre-clinical study demonstrated that knocking down TGF-β1 and COX-2 gene expression simultaneously in the tumor microenvironment increases active T cell infiltration and combining the two siRNAs produces a synergistic effect that diminishes pro-inflammatory factors.176 Descartes-11 developed by Cartesian is a CAR T-cell therapy for treating multiple myeloma, a white blood cell cancer that affects plasma cells (Table 4).177 It recently completed (March 2022) phase II studies with newly diagnosed patients.178 Descartes-11 contains autologous CD8+ T cells engineered with RNA chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) that bind to B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA).177 BCMA is highly expressed in all myeloma cells, and Descartes-11 binds and destroys BCMA-positive myeloma cells.177

Infectious diseases are caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites.

SARS-CoV-2 has infected over 549 million people, causing over 6.1 million deaths worldwide.183 The COVID-19 pandemic brought the first approved mRNA vaccine to market. BioNTech/Pfizer’s COVID-19 BNT162/Comirnaty vaccine was given U.S. FDA emergency use authorization in 2020 and approved by the FDA in 2021 (Table 5).184 Moderna’s COVID-19 mRNA-1273/Spikevax vaccine was also given US FDA emergency use authorization in 2020 and approved by the FDA in 2022 (Table 5).185 Globally over 11.39 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered.186

Table 5. RNA Therapies and Vaccines for Infectious Diseases.

| infectious disease | drug name/lab code | type of RNA | target | company | development stage | year (first posted) | clinical trial number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 | BNT162/Comirnaty | mRNA | SARS-CoV-2 spike protein | BioNTech/Pfizer | FDA approval in 2021184 | ||

| COVID-19 | mRNA-1273/Spikevax | mRNA | SARS-CoV-2 spike protein | Moderna | FDA approval in 2022185 | ||

| hepatitis B viral | AB-729 | siRNA | hepatitis B viral surface antigen | Arbutus Biopharma Corporation | phase I | 2021 | NCT04775797192 |

| influenza | mRNA-1010 | mRNA | Moderna | phase I/II | 2021 | NCT04956575193 | |

| respiratory syncytial virus | unnamed | mRNA | CureVac | pre-clinical137 | |||

| respiratory syncytial virus | mRNA-1345 | mRNA | Moderna | phase I | 2021 | NCT04528719194 |

Arbutus Biopharma Corporation developed AB-729, an RNA interference (RNAi) therapeutic specifically designed to reduce all hepatitis B virus (HBV) antigens, including hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) (Table 5).187 HBsAg interferes with host immune response,188 and preliminary data indicate that long-term suppression of HBsAg with AB-729 results in an increased HBV-specific immune response.187

Moderna’s first quadrivalent seasonal influenza mRNA vaccine candidate mRNA-1010 is in phase I/II trials (Table 5).144 mRNA-1010 targets influenza lineages recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for the prevention of influenza, including seasonal influenza A H1N1 and H3N2 and influenza B Yamagata and Victoria.189 CureVac has a mRNA prophylactic vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), a common respiratory virus that can cause serious illness in infants and older adults, in their pipeline under pre-clinical development (Table 5).137 Moderna has also developed a vaccine for RSV.144 Moderna’s mRNA-1345 (Table 5) is currently in a phase I trial to evaluate its tolerance and reactogenicity in children, younger adults, and older adults.190,191

Neuromuscular diseases affect the function of muscles and nerves that communicate sensory information to the brain.195 They affect the brain as well as the nerves found throughout the body and the spinal cord.196 These types of diseases have the greatest number of approved RNA therapeutics. Approved treatments for Duchenne muscular dystrophy include Sarepta’s ASO therapeutics Exondys 51, which targets exon 51 of the dystrophin gene, receiving FDA approval in 2016,197 Vyondys 53, which targets exon 53 of the dystrophin gene, receiving FDA approval in 2019,198 and NS Pharma’s Viltepso, also targeting exon 53 of the dystrophin gene, receiving FDA approval in 2020 (Table 6).199 Ionis Pharmaceuticals received FDA approval in 2016 for ASO therapeutic Spinraza targeting survival of motor neuron 2 (SMN2) for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy (Table 6).200 Their second therapeutic approved by the FDA in 2018 was the ASO neurological therapeutic Tegsedi, which targets hepatic production of transthyretin (TTR) and is used for the treatment of hATTR amyloidosis-polyneuropathy, a disease due to mutations in the gene encoding TTR that leads to abnormal amyloid deposits on nerves.201 Onpattro by Alnylam is another approved RNA drug for the treatment of hATTR amyloidosis-polyneuropathy by targeting hepatic production of transthyretin (Table 6).202 Onpattro, which was FDA approved in 2018 (Table 6), was the first siRNA drug.26 Sarepta Therapeutics has two other ASO therapeutics for the treatment of DMD, SRP-5044 and SRP-5050 (targeting exon 44 and exon 50 of the dystrophin gene, respectively), that are in pre-clinical studies (Table 6).203

Table 6. RNA Therapies for Neuromuscular and Neurological Diseases.

| neurological and neuromuscular disease | drug name/lab code | type of RNA | target | company | development stage | clinical trial number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy | Exondys 51 | ASO | exon 51 dystrophin | Sarepta Therapeutics | FDA approval in 2016197 | |

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy | Vyondys 53 | ASO | exon 53 dystrophin | Sarepta Therapeutics | FDA approval in 2019198 | |

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy | Viltepso | ASO | exon 53 dystrophin | NS Pharma | FDA approval in 2020199 | |

| spinal muscular atrophy | Spinraza | ASO | survival of motor neuron 2 mRNA | Ionis Pharmaceuticals | FDA approval in 2016200 | |

| hATTR amyloidosis-polyneuropathy | Tegsedi | ASO | transthyretin mRNA | Ionis Pharmaceuticals | FDA approval in 2018201 | |

| hATTR amyloidosis-polyneuropathy | Onpattro | siRNA | transthyretin mRNA | Alnylam | FDA approval in 2018207 | |

| amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | Tofersen | ASO | superoxide dismutase 1 | Ionis Pharmaceuticals/Biogen | phase III | NCT04856982208 |

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy | SRP-5044 | ASO | exon 44 dystrophin | Sarepta Therapeutics | pre-clinical203 | |

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy | SRP-5050 | ASO | exon 50 dystrophin | Sarepta Therapeutics | pre-clinical203 | |

| myotonic dystrophy type 1 | AOC 1001 | antibody–oligonucleotide conjugate | myotonic dystrophy protein kinase | Avidity Biosciences | phase I/II | NCT05027269209 |

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy | AOC 1044 | antibody–oligonucleotide conjugate | exon 44 dystrophin | Avidity Biosciences | pre-clinical205 |

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord.204 Ionis Pharmaceuticals in partnership with Biogen has an ASO investigational drug, Tofersen, in phase III clinical trials (Table 6).151 Tofersen targets superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), the second most common and best understood genetic cause of ALS.

Avidity Biosciences has a pipeline of antibody oligo-nucleotide conjugate (AOC) therapeutics focused on neuromuscular diseases. Their leading candidate, AOC 1001, is a siRNA conjugated with a monoclonal antibody (mAb) (Table 6).205 AOC 1001 has an ongoing phase I/II trial in adults with myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1). DM1 is a progressive neuromuscular disease that impacts skeletal and cardiac muscle. DM1 is caused by an abnormal number of CUG triplet repeats in the myotonic dystrophy protein kinase gene (DMPK), reducing muscleblind-like protein (MBNL) activity and disrupting muscle development.206 AOC 1001 is designed to reduce DMPK levels and CUG triplet repeats so that MBNL can perform normally.205 Avidity Biosciences has also developed an AOC to treat DMD.205 The oligonucleotides are designed to promote skipping of specific exons to produce dystrophin in patients with DMD. Their leading DMD drug candidate, AOC 1044, can induce exon skipping specifically for exon 44 (Table 6), and clinical trials are planned for 2022.205

Eye diseases including visual impairment affect 2.2 billion people globally.210 Macular degeneration, which causes loss in the center of the field of vision and is irreversible, affects 196 million people.211 Macugen, developed by Gilead Sciences (Table 7), was the first FDA-approved (2014) RNA aptamer treatment for neovascular age-related macular degeneration.212 Macugen targets the Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) protein in the eye, reducing the growth of blood vessels to control the leakage and swelling that cause vision loss.213 As age-related macular degeneration (AMD) progresses, geographic atrophy (GA), a chronic progressive degeneration of the macula, can develop.214 Zimura by Iver Bio is another RNA aptamer therapeutic and is currently in a phase III clinical trial (Table 7). Zimura inhibits complement component 5,215 which is involved in the development and progression of AMD. In clinical trials, Zimura slowed the progression of GA over 12 months in individuals with age-related macular degeneration.214 QR-504a from ProQR Therapeutics is an investigational RNA ASO therapeutic that is in ongoing phase I/II clinical trials.216 QR-504a is designed to slow vision loss in individuals with Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD) which results from trinucleotide repeat expansion mutations in the Transcription factor 4 (TCF4) gene.217

Table 7. RNA Therapies for Eye Diseases.

| eye disease | drug name/lab code | type of RNA | target | company | development stage | clinical trial number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| macular degeneration | Macugen | aptamer (RNA) | vascular endothelial growth factor protein | Gilead Sciences | FDA approval in 2014212 | |

| geographic atrophy related to age-related macular degeneration | Zimura | aptamer (RNA) | complement component 5 | IVERIC Bio | phase III | NCT04435366215 |

| Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy | QR-504a | ASO | transcription factor 4 | ProQR Therapeutics | phase I/II | NCT05052554216 |

Kidney disease affects over 850 million people worldwide.218 Primary hyperoxaluria type 1 (PH1) is a genetic kidney disease characterized by the overproduction of oxalate, which leads to kidney stones, kidney failure, and systemic oxalosis.218 The siRNA therapeutic Oxlumo was developed by Alynlam and approved by the FDA in 2020 (Table 8).219 Oxlumo targets the hydroxy acid oxidase 1 (HAO1) gene, which encodes glycolate oxidase.219 Oxlumo reduced urinary oxalate excretion in patients with progressive kidney failure in PH1.219,220 The majority of patients had normal or near-normal levels of oxalate after 6 months of treatment. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is caused by mutations in the PKD1 or PKD2 gene.221 It is characterized by cysts within the kidneys, often leading to kidney failure. To treat ADPKD, Regulus designed RGLS4326, a second-generation oligonucleotide that inhibits miR-17 (Table 8), which produces kidney cysts. RGLS4326 binds to miR-17 microRNAs, inhibits miR-17 activity, and reduces disease progression.222 Immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy is a chronic kidney disease that is caused by deposits of protein IgA inside the glomeruli of the kidneys.223 Overproduction of complement factor B (FB) is associated with increased IgA nephropathy. Ionis has partnered with Roche to develop a ligand-conjugated ASO therapeutic, IONIS-FB-LRx, which targets FB to reduce the production of IgA and alleviate the symptoms of IgA nephropathy (Table 8).151

Table 8. RNA Therapies for Kidney Diseases.

| kidney disease | drug name/lab code | type of RNA | target | company | development stage | clinical trial number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| primary hyperoxaluria type 1 | Oxlumo | siRNA | hydroxy acid oxidase 1 | Alnylam | FDA approval in 2020 | NCT04152200224 |

| autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease | RGLS4326 | oligonucleotide | miR-17 | Regulus | phase I | NCT04536688225 |

| IGA nephropathy | IONIS-FB-LRx | ASO | complement factor B | Ionis/Roche | phase II | NCT04014335226 |

Respiratory diseases affect more than 1 billion people worldwide.227 COVID-19 brought acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) to the forefront of medical news during the pandemic. ARDS is a severe inflammatory lung disease with a mortality rate of over 40%.228 Inflammation leads to lung tissue injury and leakage of blood and plasma into air spaces, resulting in low oxygen levels and often requiring mechanical ventilation.228 Descartes-30 is an engineered mRNA cell therapy product by Cartesian Therapeutics (Table 9). It comprises human mesenchymal stem cells that secret two human DNases for degrading ARDS-causing neutrophil extracellular traps (NETS).177 Descartes-30 is currently in phase I/II clinical trials.229

Table 9. RNA Therapies for Respiratory Diseases.

| respiratory disease | drug name/lab code | type of RNA | target | company | development stage | clinical trial number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| acute respiratory distress syndrome | Descartes-30 | mRNA | neutrophil extracellular traps | Cartesian Therapeutics | phase I/II | NCT04524962229 |

| cystic fibrosis | MRT5005 | mRNA | cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator | Translate Bio | phase I/II | NCT03375047236 |

| cystic fibrosis | ARO-ENaC | siRNA | epithelial sodium channel α subunit | Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals | phase I/IIa | NCT04375514237 |

Cystic fibrosis is caused by a dysfunctional cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein, resulting from mutations in the CFTR gene.230 Without CFTR, mucus in various organs including the lungs is extremely thick and sticky. MRT5005, developed by Translate Bio, is an mRNA therapeutic (Table 9) that bypasses this mutation by delivering mRNA encoding a fully functional CFTR protein to the cells in the lungs through nebulization.231 Although initial interim results from clinical studies showed promise,232 results from the second interim phase I/II clinical trial showed no increase in the lung function of individuals receiving MRT5005.233 The siRNA therapeutic ARO-ENaC is designed by Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals to reduce epithelial sodium channel alpha subunit (αENaC) in the lungs and airways (Table 9). Increased ENaC contributes to airway dehydration and increased mucus.234 However, Arrowhead paused a phase I/II study of ARO-ENaC in July 2021 after safety studies showed local lung inflammation in rats.235

Blood diseases affect one or more components of blood. Sickle cell disease is a type of blood disease that causes red blood cells to become misshapen and break down.238 Beta-thalassemia syndromes are a group of blood diseases that result in reduced levels of hemoglobin in red blood cells.239 BEAM-101 (Table 10), Beam Therapeutics leading ex vivo base editor, is a patient-specific, autologous hematopoietic investigational cell therapy. BEAM-101 introduces base edits that mimic the single nucleotide polymorphisms found in individuals with hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HPFH), which could alleviate the effects of mutations causing sickle cell disease or beta-thalassemia since the fetal hemoglobin does not become misshapen.240 Beam plans to initiate a phase I/II clinical trial to assess the safety and efficacy of BEAM-101 for the treatment of sickle cell disease.240 BEAM-101 uses an electroporation delivery system.157 Silence Therapeutics has RNA therapeutics for blood diseases such as thalassemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, and rare iron-loading anemias.241 Their siRNA therapeutic SLN124 targets transmembrane serine protease 6 (TMPRSS6) (Table 10), a gene that prevents the liver from producing hepcidin.241 Phase I clinical trial data showed that SLN124 improved red blood cell production and reduced anemia by increasing the levels of hepcidin.241,242

Table 10. RNA Therapies for Blood Disease.

| blood disease | drug name/lab code | type of RNA | target | company | development stage | clinical trial number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sickle cell disease/beta-thalassemia | BEAM-101 | CRISPR | fetal hemoglobin activation | Beam Therapeutics | pre-clinical157 | |

| thalassemia/low-risk myelodysplastic syndrome | SLN124 | siRNA | transmembrane serine protease 6 | Silence Therapeutics | phase I | NCT04718844243 |

Keloid scarring is a type of pathological condition that forms abnormally thick scarring after a skin injury. STP705, from Sirnaomics, is a siRNA therapeutic in phase II clinical trial for the treatment of keloid scars (Table 11).244 STP705 targets both TGF-β1 and COX-2 gene expression with polypeptide nanoparticle-enhanced delivery.245 The synergistic effect of simultaneous silencing TGF-β1 and COX-2 may reverse skin fibrotic scarring by decreasing inflammation and activating fibroblast apoptosis. This mechanism of action of STP705 can be widely applied for the treatment of other fibrotic conditions.245

Autoimmune diseases are characterized by immune activation in response to normal antigens.246 mRNA-6231 from Moderna is an mRNA encoding IL-2 mutein (Table 11) that activates and expands the regulatory T cell population and dampens self-reactive lymphocytes to help restore normal immune function.247

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is the inability to control alcohol use despite adverse social, occupational, or health consequences. According to the World Health Organization, AUD affects over 283 million people globally.248 Alcohol is metabolized in the liver to acetaldehyde via alcohol dehydrogenase and then to acetic acid by aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2).249 Inhibiting ALDH2 results in unpleasant symptoms due to the increased acetaldehyde when alcohol is not fully metabolized.250 The siRNA therapeutic DCR-AUD by Dicerna knocks down ALDH2 protein expression (Table 11) in the liver, which results in increased acetaldehyde levels that discourage continued alcohol use in AUD patients.250

Chemical Modifications for Improving RNA Stability and Target Specificity

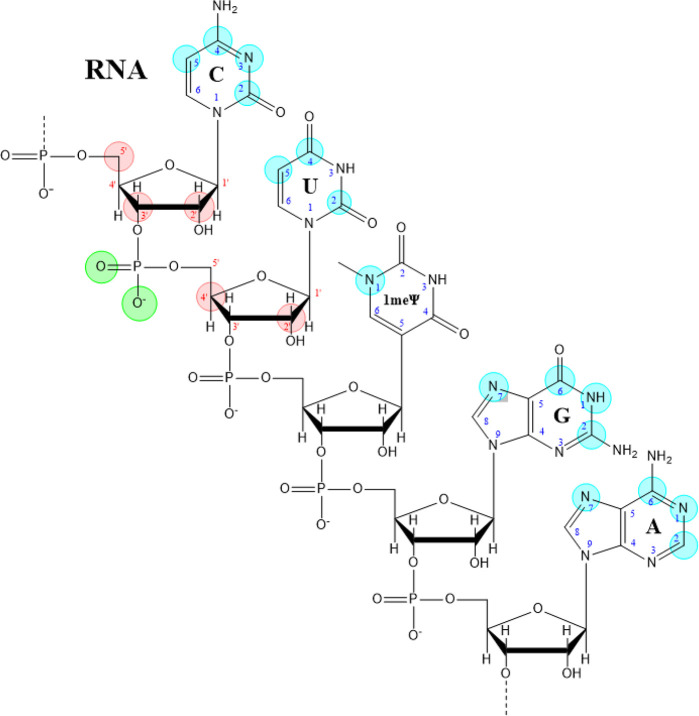

RNA is composed of nucleosides that consist of a nucleic acid base attached to a d-ribose through a β-N-glycosyl bond between the ribose and a pyrimidine base (uracil and cytosine) or a purine base (adenosine and guanosine). The nucleosides are connected by a phosphodiester bond using the phosphate between the 3′ and 5′ carbons on adjacent ribose molecules (Figure 17).253 RNAs can be modified on the nucleic acid base and on the phosphate and the ribose of the sugar–phosphate backbone, as illustrated in Figure 17 with color circles.

Figure 17.

An example of RNA structure and modification sites. Green circles, modification sites on the phosphate; red circles, attachment sites for modifications on the ribose; blue circles, attachment sites for modifications on the nucleic acid base: 1-methylpseudouridine (1meΨ), cytosine (C), uridine (U), guanosine (G), and adenosine (A).

The nucleic acid side chains extending from the sugar–phosphate backbone form hydrogen bonds between the nucleic acid bases of complementary RNA chains; U bonds with A, and G bonds with C. Double-stranded RNA structures form as a result of intramolecular and intermolecular base pairing. Base pairing between loops of double-stranded stem-loops can yield 3D structures, and triple helixes can form within single strands or between multiple strands.

Chemical modifications on RNA can improve the stability and reduce the immunogenicity of therapeutic RNAs. RNA is very susceptible to nucleases and hydrolysis by basic compounds. Chemical modification of RNA protects the vulnerable sugar–phosphate backbone from nuclease degradation and lowers the risk of off-target effects. For RNAs that form a duplex with a target sequence, mutations that lower the melting temperature of the duplex destabilize the complex and improve target specificity by decreasing base pairing with non-target RNA. RNA modifications can also improve the delivery of the RNA into the cell through the plasma membrane and enhance the activity of the RNA.104

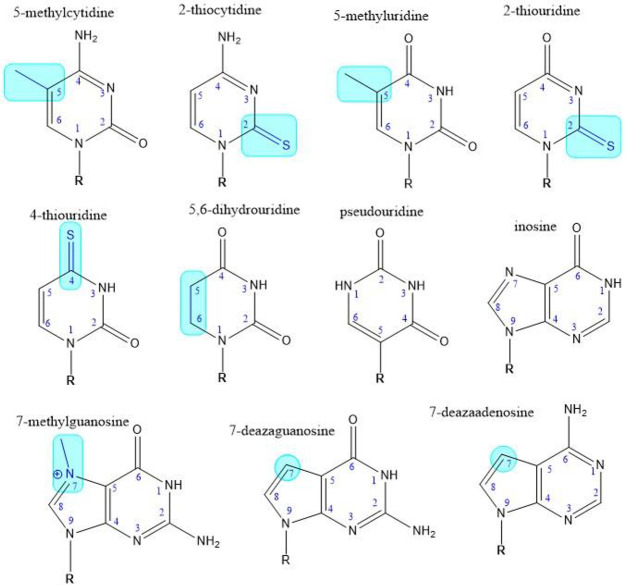

Nucleic acid base modifications

Figure 18 shows chemical structures of commonly seen base modifications and rare bases. Modifications include methylation, replacement of oxygen with sulfur, and replacement of a nitrogen within the ring system with carbon. Cytidines or uridines can be methylated at the N-5 position to be 5-methylcytidines or 5-methyluridines. Cytidines can have the oxygen replaced with a sulfur at the N-2 position to be 2-thiocytidines. When uridines have the oxygen replaced with a sulfur at either the N-2 or the N-4 position, they become 2-thiouridines or 4-thiouridines respectively. Uridines can also be reduced on the base ring and become 5,6-dihydrouridines. Another commonly seen base modification, methylation at the N-7 position of the guanosine, occurs in mRNA cap structure. The guanosines can also be modified at the N-7 position by converting the nitrogen to a carbon, and become 7-deazaguanosine. Similar modifications can happen to adenosines, resulting in 7-methyladenosines and 7-deazaadenosines. The rare bases, pseudouridine and inosine, are also seen in modified RNA sequences. Additional modified or rare bases are shown in Figure S7. According to the data in the CAS Content Collection,32 the use of RNA modifications has been increasing since 1995 (Figure S6).

Figure 18.

Examples of modified and rare bases. R = d-ribose; locations of modifications are shown in blue.

Base modifications that interfere with the formation of hydrogen bonds can thermally destabilize duplex formation with the target, and thus improve target specificity by limiting off-target binding.254 In addition, modifications improve the performance of therapeutic RNA. Replacing uridine with the modified base 1-methylpseudouridine (Figure 17) in therapeutic mRNAs, such as the COVID-19 vaccines (Pfizer’s Comirnaty and Moderna’s Spikevac), improves translation and lowers cytotoxic side effects and immune responses to the mRNA.255 Both Pfizer’s Comirnaty and Moderna’s Spikevac mRNA vaccines also use a 7-methylguanosine cap linked by a 5′-triphosphate to the 5′ end of the mRNA, replicating the naturally occurring mRNA caps that prevent degradation of the 5′ end of the mRNA.256

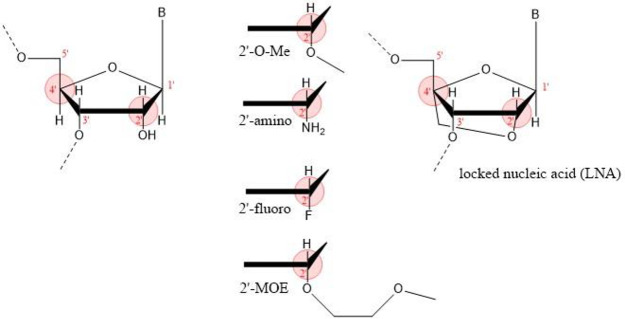

Modifications on Ribose

The hydroxyl group on the C-2′ position of the ribose destabilizes RNA compared to DNA. Modification of this hydroxyl protects against nuclease digestion and can lower the thermal stability of duplexes formed with a target RNA. Figure 19 shows the chemical structures of these modifications on ribose. The most common modifications at the C-2′ position include 2′-O-methyl, 2′-amine, 2′-fluoro, and 2′-O-methoxyethyl (2′-MOE). Another modification at the C-2′ position is the LNA in which a 2′-O,4′-C-methylene bridge connects the 2′ position to the 4′ position on the ribose.257

Figure 19.

Common modifications on the 2′-hydroxyl group of d-ribose. B = nucleic acid base.

In addition, the 5′ and 3′ ends of RNA can be modified using cleavable linkers attached to GalNAc groups or lipophilic moieties to target the therapeutic RNA to the desired tissue. The linkers are cleaved by acid pH, redox potential, or degradative enzymes in cells but not in serum or blood. Cleavable linkers include acid-cleavable groups, ester-based cleavable groups, and peptide-based cleavable groups.254

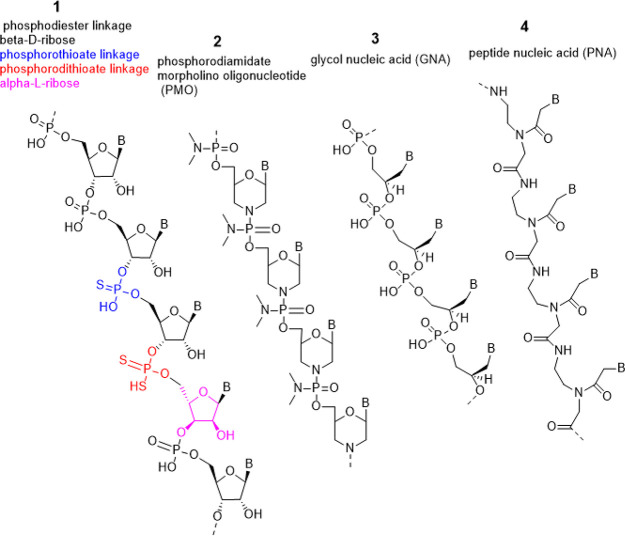

Backbone Modifications

Modifications to the phosphate group in the sugar–phosphate backbone can improve the resistance of therapeutic RNAs to extracellular and intracellular nucleases. In addition, the negative charge on the phosphate group interferes with the delivery of the RNA into the cell through the lipid bilayer membrane, which is impermeable to polar molecules. Thus, replacing the oxygens on the phosphates with neutral groups or complexing the phosphate groups to cations like sodium can improve RNA delivery.258

A widely used backbone modification, phosphorothioate, as shown in Figure 20, which replaces an oxygen in the phosphate group with sulfur, reduces the activity of extracellular and intracellular nucleases.259 RNA molecules with phosphorothioate linkages at the ends resist exonucleases, whereas RNA molecules with phosphorothioate linkages within the RNA resist endonucleases. However, the sulfur on the phosphate group creates stereogenic α-phosphorus atoms resulting in diastereomers with different functional properties that can affect duplex formation. Careful spacing of the phosphorothioate linkages within the RNA can ameliorate this problem.257,258

Figure 20.

Examples of modified RNA backbones. Backbone 1 shows phosphate–ribose backbone linkages, which include the classic phosphodiester (black), phosphorothioate (blue), and phosphorodithioate (red). The purple ribose, α-l-ribose, has an alternative stereochemistry compared to the normal β-d-ribose moieties shown in black. Backbone 2 is a phosphorodiamidate morpholino (PMO) backbone, backbone 3 is (R)-glycol nucleic acid ((R)-GNA), and backbone 4 is peptide nucleic acid (PNA). B = nucleic acid base.

Other backbone modifications replace the d-ribose with either an l-ribose or a non-ribose moiety (Figure 20). Phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligonucleotides (PMOs) contain morpholino groups linked by phosphorodiamidate groups rather than ribose linked by phosphates. Glycol nucleic acids (GNAs) have a backbone of repeating glycerol units linked by phosphodiester bonds.260 In peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) the sugar–phosphate backbone is replaced with a flexible N-(2-aminoethyl)glycine polymer with the nucleobases attached via a methylene carbonyl linkage.261 PMOs, GNAs, and PNAs all resist nuclease degradation. PNA forms duplexes with complementary DNA or RNA with higher affinity and specificity than unmodified DNA–DNA or DNA–RNA duplexes. However, duplexes containing PNAs, PMOs, and LNAs resist RNase H degradation, inhibiting gene knockdown through targeted mRNA degradation.257

Trends of RNA Chemical Modifications

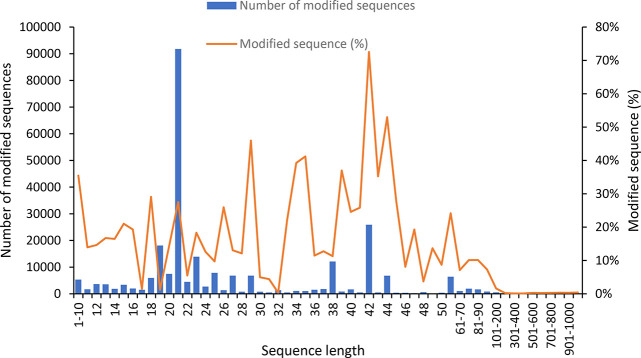

Sequence data for RNAs and RNA modifications are annotated and collected with CAS Registry Sequence Guidelines262 from published documents and stored in the CAS Content Collection.32 To better understand the chemical modification trends on RNA molecules, we extracted ∼170,000 modified RNA sequences from the CAS Content Collection. Figure 21 shows the number of the modified RNA sequences and distribution of these modified sequences along the sequence length. The predominance of modified nucleotide RNAs for lengths of 18–27 bases reflects the fact that this sequence length is commonly used in siRNAs and ASOs; processed, naturally occurring double-stranded siRNAs are typically 21 or 23 bp long. The double-stranded nature of siRNAs accounts for the large number of modifications for nucleotides with a length of 42 and 44; two 21-nucleotide RNAs produce 42 nucleotides of RNA, while a 21-nucleotide and a 23-nucleotide RNA produce 44 nucleotides. The percentage of modified RNA sequences in the total RNA sequences was also shown along the sequence length, suggesting that sequences less than 100 base pairs are more frequently being modified than the longer sequences. This drop-off observed in RNA modification for RNAs over 100 nt is likely an artifact of the methods used to synthesize artificial RNA and the methods used to sequence naturally occurring RNAs. Small artificial RNAs are produced by solid-support synthesis or other chemical methods; larger RNAs are produced by in vitro transcription. Chemical synthesis has more capacity to add modified nucleotides to an RNA; in vitro transcription faces the limitations posed by the use of enzymes. Furthermore, naturally occurring RNA sequences are generally characterized by reverse transcription to cDNA, amplification, and then sequencing. This process would obscure modification present on the initial RNA.

Figure 21.

RNA sequences containing modifications and their distribution with respect to sequence lengths (from the CAS Content Collection). Blue bars: absolute number of modified RNA sequences; orange line: percentage of modified RNA sequences in the total RNA sequences with same sequence length.

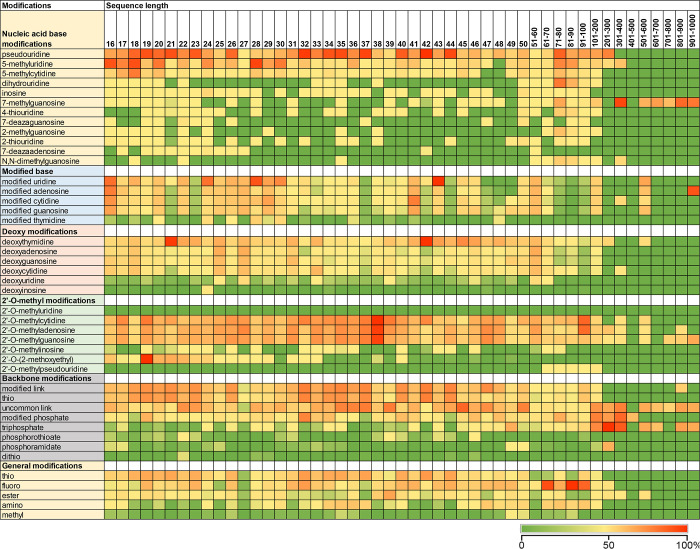

Chemical modifications were further analyzed using this data set with specific types of modifications and sequence lengths. Out of 145 curated sequence modifications, 117 sequence modifications were identified in the modified RNA data set. A heatmap (Figure 22) covering the most popular modifications was constructed based on the relative frequencies of specific types of modification in the total modification events in that sequence length. The heat map of modification type versus sequence length shows a sharp change in the types of modifications in sequences <200 nucleotides vs >200 nucleotides. Sequences >200 nucleotides are modified much less than shorter sequences. This set of longer RNAs, which includes lncRNAs and mRNAs, is either transcribed in vivo or produced using in vitro transcription. The most common modifications contained in the longer sequences are triphosphates and 7-methylguanosines, suggesting that they are mRNAs with 5′ end caps consisting of 7-methylguanosine linked to the 5′ end of the mRNA with a triphosphate group. In addition, modified adenosine is observed in longer sequences, particularly in sequences from 901 to 1000 nucleotides; this would include the mRNA modification, 6-methyladenosine.263,264 Since therapeutic mRNAs are translated by the ribosomes to produce an active protein, excessive modification might provide steric hindrance that inhibits translation.

Figure 22.

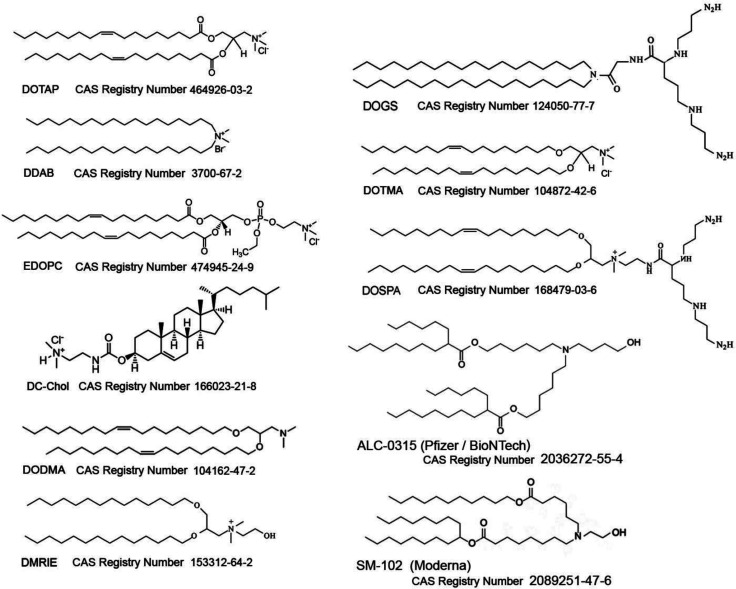

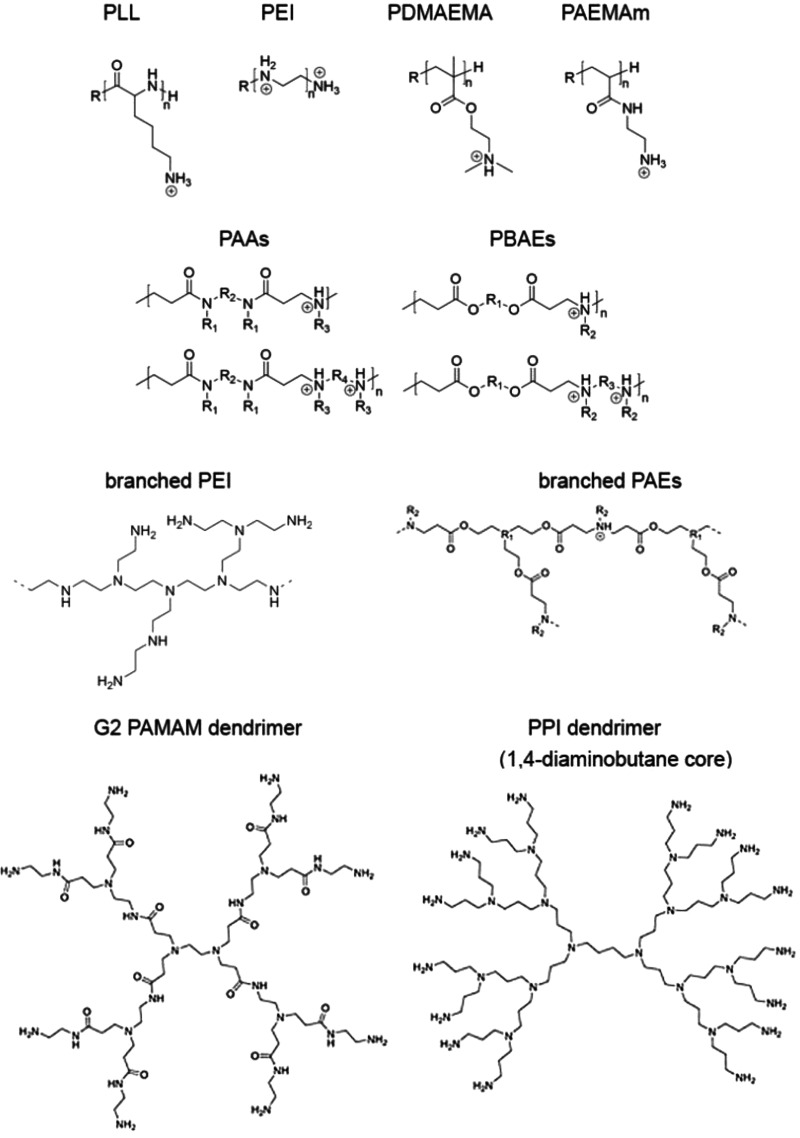

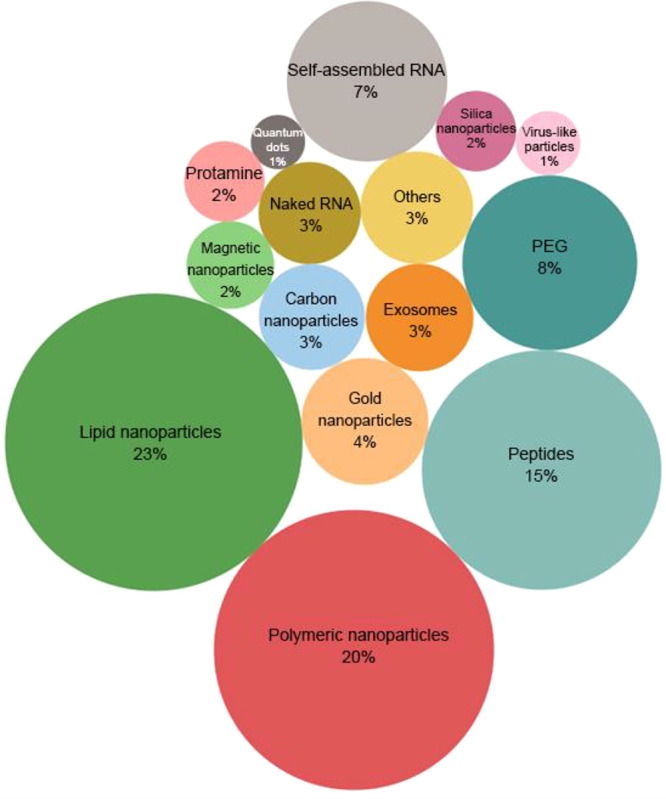

Frequencies of modifications of RNA and their distributions based on sequence lengths (CAS Content Collection).