Abstract

Cancer treatment is associated with financial hardship for many patients and families. Screening for financial hardship and referrals to appropriate resources for mitigation are not currently part of most clinical practices. In fact, discussions regarding the cost of treatment occur infrequently in clinical practice. As the cost of cancer treatment continues to rise, the need to mitigate adverse consequences of financial hardship grows more urgent. The introduction of quality measurement and reporting has been successful in establishing standards of care, reducing disparities in receipt of care, and improving other aspects of cancer care outcomes within and across providers. The authors propose the development and adoption of financial hardship screening and management as an additional quality metric for oncology practices. They suggest relevant stakeholders, conveners, and approaches for developing, testing, and implementing a screening and management tool and advocate for endorsement by organizations such as the National Quality Forum and professional societies for oncology care clinicians. The confluence of increasingly high-cost care and widening disparities in ability to pay because of underinsurance and lack of health insurance coverage makes a strong argument to take steps to mitigate the financial consequences of cancer.

Keywords: cancer, disparities, financial hardship, quality measurement, screening

Introduction

Financial hardship after a cancer diagnosis is well documented in the United States.1 In addition to financial stressors that can leave patients and their families with debt and possible bankruptcy, financial hardship has negative emotional and physical effects. The pervasiveness of financial distress for cancer patients led to the creation of the term financial toxicity, a term that is consistent with other adverse events associated with treatment.2,3 Three major factors contribute to financial hardship: first, the cost of cancer treatment has risen considerably in the past 20 years4-9; second, more patients are eligible for treatment with expanding treatment options for cancer and are receiving treatment for a longer duration10; and third, the changing landscape of health insurance benefit design has led to patients paying out-of-pocket for a greater portion of their medical care expenditures.11 Spending on cancer drugs in the United States has grown 64% from 2013 to 2018, reaching $57 billion in 2018, and the median annual list price of newly approved cancer drugs has remained above $150,000 since 2014.12 Many of these newly approved cancer drugs are oral targeted agents that are taken until evidence of disease progression.13,14 In addition, advancements in radiation oncology and surgical oncology have also led to rising costs and patient financial burden.15

Simultaneously with the rise in cancer treatment costs is the trend in the rising number of uninsured16,17 and underinsured adults and the increased prevalence of high-deductible health insurance plans. More than 40% of adults with employer-based coverage have high-deductible health insurance plans that require patients to pay deductibles as much as $6750 out-of-pocket for individual coverage or $13,500 for family coverage in 2018 before insurance coverage begins18—an untenable amount for patients and families for whom the average monthly full-time pretax earnings were $3744 per month in the fourth quarter of 2019.19 A recent survey from the Federal Reserve reports that 40% of American families cannot cover an unexpected expense of ≥$400.20 Because financial burden is associated with gaps in insurance programs, it is no surprise that cancer survivors aged 18 to 64 years are more likely to experience financial hardship relative to their older, Medicare-insured counterparts21,22 who may qualify for programs like the Medicare Part D low-income subsidy program.23

To address these challenges, we propose a process for developing a financial screening and management quality measure for oncology practices. Although quality measures have limitations, without a national effort to incorporate financial screening and appropriate referral into routine practices, patients’ financial burden will continue to rise unabated. Widespread unemployment because of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, with accompanying loss of income and potential loss of health insurance coverage, will amplify escalating cost trends and underscore the urgency for mitigation.

Need for Financial Hardship Screening and Referral

Financial hardship negatively affects patients’ financial well-being, as reflected in increased household debt, savings depletion, and the need for bankruptcy protection,24-26 it negatively affects treatment adherence as well as physical and emotional well-being, and it may reduce cancer survival. Higher out-of-pocket costs for cancer drugs are associated with delayed treatment initiation and treatment abandonment.27-30 Patients experiencing financial hardship are also more likely to forgo mental health care, physician visits, and other medical care.28 These patients experience more symptom burden and diminished quality of life,31-33 and they may be at greater risk for early mortality.34 Initial evidence from a pilot study suggests that financial navigation programs can reduce anxiety about costs, even if financial burden does not change.35 Hospital staff training programs in financial navigation can decrease patient out-of-pocket spending ($33,265 on average per year) and reduce losses to health care institutions.36 However, in a survey of oncology navigators, only one-half agreed that patients got needed financial services,37 suggesting considerable room for improvement in connecting patients to resources.

The impact of treatment-related financial hardship has received attention from many professional societies, advocacy organizations, and the National Cancer Institute (NCI). For example, the Value in Cancer Care Task Force at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommends that all providers of cancer treatment have a discussion with patients about the cost of their care.38 Other organizations, including the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and the President’s Cancer Panel, highlight the importance of addressing the high costs of cancer care. Even smaller organizations such as the Mesothelioma Society feature information on cancer’s financial hardship on their website.39

Nearly all NCI-designated cancer centers conduct some form of financial screening, but only 30% of the centers are engaged in research to study outcomes and effectiveness of financial screening and connection to resources.40 Respondents to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) survey of member institutions (17 of 27 institutions) report that most have financial screening and management programs, but there is considerable variation in screening approach and services offered,41 highlighting the need for efforts to better document, understand, and alleviate financial burden in a standardized and systematic way. In addition, although the Commission on Cancer requires psychosocial screening for accreditation,42 this measure is assessed using the NCCN Psychosocial Distress Thermometer, which is not specific to distress related to financial concerns. Collectively, these efforts provide an opening to address the gap in financial hardship assessment and mitigation.

Role for Quality Metrics

The 1999 Institute of Medicine report Ensuring Quality Cancer Care emphasized the importance of developing and monitoring quality measures for a high-quality cancer care system.43 Its 2013 report Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care reemphasized the importance of quality metrics in a learning health care system and offered a standard set of tools to quantify and compare performance across providers.44 Quality metrics, when combined with accreditation of health care organizations or reimbursement under value-based payment models, are a powerful lever to transform clinical practice. Prior research has shown that clinician awareness of financial burden leads to lower out-of-pocket costs for patients.45 Another potential lever is the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) Oncology Care Model, which is an episode-based payment model with financial incentives to provide high-quality, low-cost chemotherapy treatment.46 On the basis of recommendations from the Institute of Medicine,44 providers agree to participate in shared decision making that incorporates treatment and cost information. A standardized approach to financial screening that is compatible with practice workflows could facilitate adherence to the Oncology Care Model’s requirements.

To improve the standard of care across oncology practices, several professional societies developed cancer-related quality metrics, such as ASCO’s Quality Oncology Practice Initiative.47 Metrics of the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative include screening for smoking and plans for cessation if individuals screen positive, screening for pain and a plan for pain management, and screening for emotional and mental distress along with a plan for mitigation. The measures are used alongside clinical measures such as treatment plan documentation and referrals to ancillary or adjuvant care.

As a result, oncology practices have become more resourceful with referral services and more facile in recognizing and documenting patient distress that interferes with cancer treatment, recovery, and survivorship. They also have become more versed in addressing these issues during a patient encounter as interventions to aid implementation of quality metrics grow. For example, approaches to palliative care consultations have been developed as have the adoption of standardized templates to document care.48,49

We propose the development of a new, standardized financial hardship screening tool, along with a compendium of local, state, and national resources, that fits within clinical workflows in practices ranging from academic medical centers to community-based practices. Multiple domains for such an instrument can be considered, including: 1) adequacy of insurance coverage, 2) whether insurance coverage depends on the employment of the patient or a caregiver and vulnerability to loss of coverage, 3) health insurance and financial literacy of the patient and caregiver,50,51 4) out-of-pocket expenses for copays, coinsurance, and deductibles as well as other medical costs, 5) out-of-pocket expenses for nonmedical services (eg, transportation, child care, home care, lodging, parking), and 6) impact on employment (eg, modification of work schedule, long-term impact on ability to perform a job, work loss). Ultimately, the domains chosen should be those agreed upon by key stakeholders who experience and bear the financial burdens associated with cancer and its treatment. Financial hardship screening should be conducted multiple times throughout the treatment trajectory to reflect changes in the treatment plan and patients’ lives.52

Screening alone is inadequate without a management plan. Such a plan includes referrals to social services, compassionate care programs, legal aid societies, and financial management services. Working alongside the oncology care team, the patient should be able to view a menu of institutional and community resources through their patient portal so they can follow-up with community resources as needed. We envision the outcomes of screening as identification of patients at high risk for financial hardship, documentation of financial assistance gained, fees waived, dollars and services received for patients at-risk, and other outcomes, as appropriate, as well as unmet needs.

Compilation of resources requires tailoring plans to the resources available in local communities. Venues through which this can be accomplished include collaboration with NCI-designated cancer centers’ community outreach and engagement teams. In addition, there is opportunity for state cancer plans53 to compile statewide resources available to alleviate financial burden. These planning efforts could collaborate with community practices to provide statewide resources to complement institution-specific or practice-specific resources.

Plan for Financial Hardship Quality Metric Development and Adoption

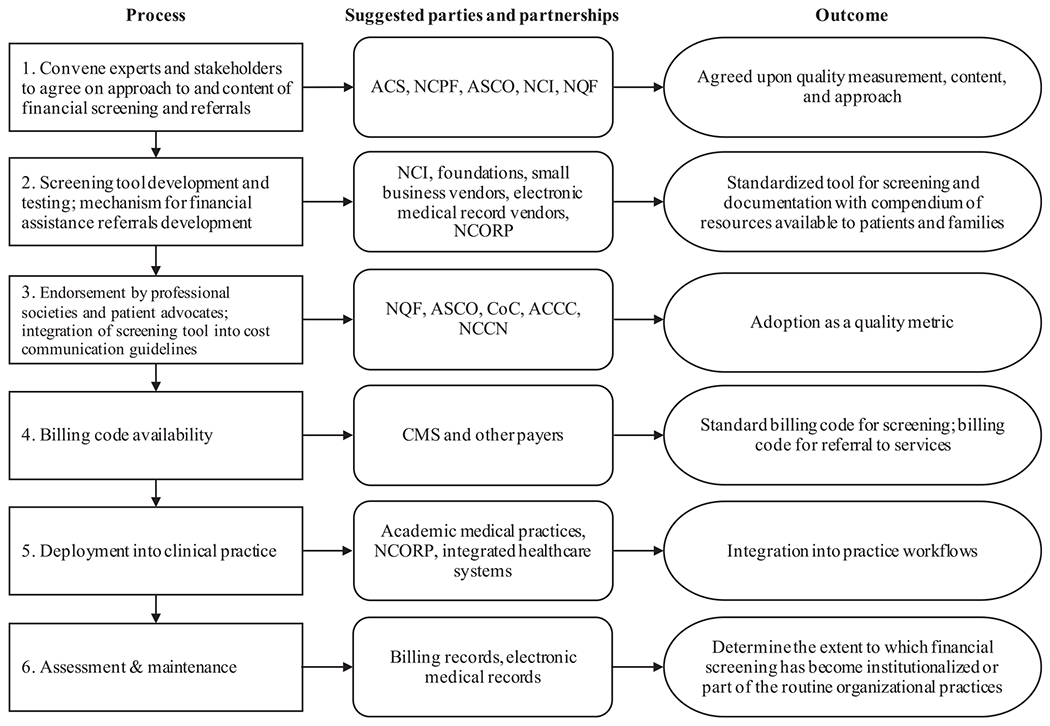

Figure 1 summarizes the process we recommend for developing and adopting a financial screening tool as a quality metric. The development of quality measures to improve patient outcomes is well established in oncology. The use of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) for symptom management increases survival for patients with metastatic cancer54 and is recommended for routine cancer care. Palliative care has a long-standing history of using PROs to support its adoption55-58 and is recommended as part of standard practice.

FIGURE 1.

Proposed Processes for Adoption and Implementation of Financial Hardship Screening and Management as a Quality Measure. ACCC indicates Association of Community Cancer Centers; ACS, American Cancer Society; ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; CMS, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; CoC, Commission on Cancer; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; NCI, National Cancer Institute; NCORP, NCI Community Oncology Research Program; NCPF, National Cancer Policy Forum of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; NQF, National Quality Forum.

An initiative conducted by the Pacific Business Group on Health, funded by the CMS, is developing PRO performance measures to improve health-related quality of life and pain management for oncology patients. The development of these measures is overseen by a multistakeholder steering committee, a multidisciplinary technical expert panel with patient representatives, and an ad hoc clinical workgroup. They will submit the PRO performance measures to the National Quality Forum (NQF) for review and will test the newly developed measures with the Michigan Oncology Quality Consortium and the Alliance of Dedicated Cancer Centers, where at least 28 sites are committed to participate in testing.59 We propose a similar process for developing a financial hardship screening and referral quality measure.

In a blueprint from the American Cancer Society to improve survivorship care, the authors proposed developing quality metrics as an essential component for dissemination and implementation.60,61 Likewise, a blueprint to combat financial hardship can elevate the development of quality metrics for screening and addressing financial hardship as a research priority, developed in conjunction with providers, patients, and patient advocates. These metrics must also be endorsed by professional societies and other organizations, such as the NCCN and NQF, to gain widespread approval and adoption. The NQF offers a Measure Incubator to facilitate measure development and testing through partnerships with stakeholders.62 They focus on areas of quality where there are gaps and where measure development may be complicated, costly, and time-consuming.62 We suggest convening an expert panel consisting of stakeholders to develop the content and presentation of a financial screening tool. Potential conveners include the ASCO, the National Cancer Policy Forum at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, the NCI, the American Cancer Society, the NQF, and the Association for Community Cancer Centers, as well as recognized experts from academia, practice, advocacy, and the payer community, including the CMS and major private payers. The NQF, which reaches their recommendations through a consensus process involving content experts and public and private stakeholders, is a model for how the content can be chosen. Buy-in from the larger community of clinicians, patients, and payers is necessary to elevate the need and acceptance of financial screening and management into practice. Moreover, payers can contribute valuable information in determining financial toxicity by providing a customized estimate of expected costs to the patient based on the benefit design of their health insurance plan, and treatment type, and duration.

The next step is to support research for the development of approaches to financial screening and management that can be integrated into practice workflows. Evidence supports that the electronic collection of PROs results in improved quality of care for patients with cancer but requires carefully constructed analytical solutions to ensure that such measures become part of routine practice.63 Several grant and contract mechanisms, including the National Institutes of Health Small Business Innovation Research program, are available to solicit the development of such tools; or, alternatively, partnerships could be initiated with electronic medical records vendors, such as EPIC or Cerner. Another potential funding source for such efforts is philanthropic foundations with an interest in improving public health and health care delivery, such as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation64 or Arnold Ventures.65 An advantage of using electronic medical records as a platform for screening and referrals is that outcomes such as dollars and services received and unmet needs can be tracked and monitored by the institution and, if made available, by the larger research community.

After the development of appropriate screening tools and methods for their implementation, testing is necessary. The success of financial screening depends on how well it fits within existing workflows and processes and whether it provides benefit to patients. We recommend a module developed as part of the electronic medical record system that can be accessed by patient navigators or other members of the oncology care team. Testing could involve multiple health systems and also could reach smaller community practices. We suggest strategic partnerships with the existing NCI Community Oncology Research Program infrastructure, which encompasses large and small practices, including the minority-based NCI Community Oncology Research Program.

Pragmatic dissemination and implementation strategies, such as RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance), offer a framework for widespread testing and adoption of financial screening tools66 in a variety of clinical settings. As applied to our proposed approach for the development and adoption of a quality measure, reach is achieved through consensus and development of the measure tool for clinical practice; effectiveness is accomplished through identification of patients at high risk for financial hardship and connecting these patients to programs or organizations for financial assistance; adoption is achieved through the endorsement of professional societies and requirement from payers, such as CMS; implementation, in the quality measure context, is the standardized approach in which financial screening and referrals are made, such as developing an Epic or similar module (Epic Systems Corporation) that can be implemented into practice workflows; and maintenance refers to the long-term effects of financial screening on outcomes and payments to the patient and providers. These outcomes (eg, payments made, treatment adherence, etc) must be measured over time with modifications to the program made as needed to assess the oncology care team burden and patient benefit.

Creating a billing code or modifier specific to financial hardship screening could increase clinicians’ acceptance and use of a financial hardship screening tool in clinical practice and provide an avenue for retrospective tracking and research. The lack of reimbursement is often cited as a reason that survivorship care plans—widely accepted as important for transitioning patients out of the oncology setting after treatment—have not been adopted into practice.67 Reimbursement serves a dual purpose: it creates a mechanism for compensation and becomes a means to track the frequency of financial screening through claims data. A more forceful approach is to mandate financial screening as a requirement for providers to receive reimbursement for cancer treatment and use this billing code to document the delivery of financial screening. A precedent is the CMS reimbursement policy for lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography. To ensure that smoking-cessation counseling and shared decision making (SDM) will take place before individuals undergo lung cancer screening, the CMS creates a unique billing code (G0296) for SDM and requires a documented, written order of an SDM visit when submitting claims for low-dose computed tomography.

Patient and provider education are other key elements that must accompany the introduction of financial hardship screening. It is critically important to build patient trust and ensure that the purpose of financial hardship screening is for physicians to help patients receive the best care, instead of excluding or including patients in a practice based on their ability to pay or using it as a tool to ration care or provide unequal care based on ability to pay.

We acknowledge that there are other approaches for the widespread incorporation of financial hardship screening and referrals into practice. The proposed process for development, testing, and incorporation of a quality measure is a long one. Therefore, currently, we encourage the use of at least informal screening (for example, simply asking patients whether they have problems affording care or are worried about lost income because of time off from work, or including a financial counselor in the intake process) until formal metrics are in place. There exists an urgent need to push this agenda forward to develop practical solutions for oncology practices and patients and their families. We believe incorporating financial hardship screening and referrals for help is necessary, much in the same way smoking cessation, weight loss, and psychological distress are routinely screened and addressed.

Concluding Remarks

We make a case for incorporating financial screening, along with a plan for mitigation of financial hardship, as a new quality metric for oncology practices. We highlight the untenable circumstances patients face when confronted with the high cost of cancer care, which is well documented.1 We also discuss the effect quality metrics have had on oncology practices and why we believe quality metrics are a way to incorporate financial concerns into routine practice. The approach we propose is patient-centered, which is what most patients want when balancing treatment and financial concerns.68 Practice change is rarely expeditious, and the path we propose toward incorporating financial burden assessment into practice is no exception.

A business case for practice change is often necessary. Some organizations have successfully demonstrated that reducing patients’ financial burden has resulted in additional payments for oncology services.69 Presumably, with less financial hardship, treatment adherence improves and mortality risk lessens, creating monetary benefits for payers and society as well. Moreover, armed with information regarding financial burden and harm to patients, payers are in a better position to negotiate on drug price relative to clinical benefit.

Actionable steps are urgently needed to alleviate the precarious financial position many patients and families face. Cancer’s financial consequences have adverse health, emotional, and social effects and the potential to widen disparities between those with resources and those without. With every new agent approved, the problem exacerbates such that exciting new therapies that can extend life and alleviate symptoms are increasingly unaffordable, and thereby unavailable, to patients who need them.

DISCLOSURES:

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01CA207216, R01CA225647, P30CA44688) and Health Care Services Corporation/Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas. S. Yousuf Zafar reports grant research support from the National Institutes of Health; grant research support and institutional research funding from AstraZeneca; personal fees from AIM Specialty Health, Vivor LLC, Sam Fund, RTI International, McKesson Corporation, and WIRB-Copernicus Group; uncompensated service on the Family Research Foundation board of directors; and spousal employment at Shattuck Labs Inc, all outside the submitted work. Ya-Chen Tina Shih reports personal fees from Pfizer Inc and personal fees from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. Cathy J. Bradley and K. Robin Yabroff report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Yabroff KR, Bradley C, Shih YT. Understanding financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States: strategies for prevention and mitigation. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:292–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, part I: a new name for a growing problem. Oncology (Williston Park). 2013;27:80–81,149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, part II: how can we help with the burden of treatment-related costs? Oncology (Williston Park). 2013;27:253–254,256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison C ‘Financial toxicity’ looms as cancer combinations proliferate. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:783–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y, Hueser HC, Hernandez I. Comparing the approval and coverage decisions of new oncology drugs in the United States and other selected countries. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23:247–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shanafelt TD, Borah BJ, Finnes HD, et al. Impact of ibrutinib and idelalisib on the pharmaceutical cost of treating chronic lymphocytic leukemia at the individual and societal levels. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:252–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bach PB. Limits on Medicare’s ability to control rising spending on cancer drugs. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:626–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Part B Drug Average Sales Price. Manufacturer Reporting of Average Sales Price (ASP) Data. 2020. Accessed June 10, 2020. cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Part-B-Drugs/McrPartBDrugAvgSalesPrice

- 9.Savage P, Mahmoud S, Patel Y, Kantarjian H. Cancer drugs: an international comparison of postlicensing price inflation. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:e538–e542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradley CJ, Yabroff KR, Mariotto AB, Zeruto C, Tran Q, Warren JL. Antineoplastic treatment of advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: treatment, survival, and spending (2000 to 2011). J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:529–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Printz C Drug parity legislation: states, organizations seek to make oral cancer drugs more affordable. Cancer. 2014;120:313–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The IQVIA Institute. Global Oncology Trends 2019. Accessed February 12, 2020. iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/global-oncology-trends-2019

- 13.Hess LM, Louder A, Winfree K, Zhu YE, Oton AB, Nair R. Factors associated with adherence to and treatment duration of erlotinib among patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23:643–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang ML, Blum KA, Martin P, et al. Long-term follow-up of MCL patients treated with single-agent ibrutinib: updated safety and efficacy results. Blood. 2015;126:739–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith GL, Ganz PA, Bekelman JE, et al. Promoting the appropriate use of advanced radiation technologies in oncology: summary of a National Cancer Policy Forum workshop. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;97:450–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffith KN. Changes in insurance coverage and access to care for young adults in 2017. J Adolesc Health. 2020;66:86–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tolbert J, Orgera K, Singer N, Damico A.Kaiser Family Foundation. Key Facts About the Uninsured Population. Accessed August 14, 2020. files.kff.org/attachment//fact-sheet-key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population

- 18.Kullgren JT, Cliff BQ, Krenz CD, et al. A survey of Americans with high-deductible health plans identifies opportunities to enhance consumer behaviors. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38:416–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Usual Weekly Earnings of Wage and Salary Workers, Fourth Quarter 2019. Accessed February 18, 2020. bls.gov/news.release/pdf/wkyeng.pdf

- 20.Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2017. Accessed June 18, 2020. federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2017-report-economic-well-being-us-households-201805.pdf

- 21.Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP, et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:259–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ekwueme DU, Zhao J, Rim SH, et al. Annual out-of-pocket expenditures and financial hardship among cancer survivors aged 18-64 years—United States, 2011-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:494–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chou YT, Farley JF, Stinchcombe TE, Proctor AE, Lafata JE, Dusetzina SB. The association between Medicare low-income subsidy and anticancer treatment uptake in advanced lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;112:637–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shankaran V, Jolly S, Blough D, Ramsey SD. Risk factors for financial hardship in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: a population-based exploratory analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1608–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington state cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:1143–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doshi JA, Li P, Huo H, Pettit AR, Armstrong KA. Association of patient out-of-pocket costs with prescription abandonment and delay in fills of novel oral anticancer agents. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:476–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knight TG, Deal AM, Dusetzina SB, et al. Financial toxicity in adults with cancer: adverse outcomes and noncompliance. J Oncol Pract. 2018:JOP1800120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Streeter SB, Schwartzberg L, Husain N, Johnsrud M. Patient and plan characteristics affecting abandonment of oral oncolytic prescriptions. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(3 suppl):46s–51s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaisaeng N, Harpe SE, Carroll NV. Out-of-pocket costs and oral cancer medication discontinuation in the elderly. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20:669–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lathan CS, Cronin A, Tucker-Seeley R, Zafar SY, Ayanian JZ, Schrag D. Association of financial strain with symptom burden and quality of life for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1732–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perry LM, Hoerger M, Seibert K, Gerhart JI, O’Mahony S, Duberstein PR. Financial strain and physical and emotional quality of life in breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58:454–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:980–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shankaran V, Leahy T, Steelquist J, et al. Pilot feasibility study of an oncology financial navigation program. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:e122–e129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherman D, Fessele KL. Financial support models: a case for use of financial navigators in the oncology setting. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2019;23:14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spencer JC, Samuel CA, Rosenstein DL, et al. Oncology navigators’ perceptions of cancer-related financial burden and financial assistance resources. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:1315–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: the cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3868–3874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Mesothelioma Center at Asbestos.com. High Cost of Cancer Treatment. Accessed February 8, 2020. asbestos.com/featured-stories/high-cost-of-cancer-treatment/

- 40.National Cancer Institute. Survey of Financial Navigation Services and Research: Summary Report. National Cancer Institute; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khera N, Sugalski J, Krause D, et al. Current practices for screening and management of financial distress at NCCN member institutions. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18:825–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.OncoNav. CoC 2020 Standards: Addressing Barriers to Care and Psychosocial Distress Screening. Accessed September 17, 2020. onco-nav.com/coc-2020-standards-addressing-barriers-to-care-and-psychosocial-distress-screening/

- 43.Institute of Medicine. Ensuring Quality Cancer Care. The National Academies Press; 1999. Accessed June 19, 2020. nap.edu/catalog/6467/ensuring-quality-cancer-care [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Institute of Medicine. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. The National Academies Press; 2013. Accessed June 19, 2020. nap.edu/catalog/18359/delivering-high-quality-cancer-care-charting-a-new-course-for [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zafar SY, Chino F, Ubel PA, et al. The utility of cost discussions between patients with cancer and oncologists. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21:607–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Oncology Care Model. Accessed July 6, 2020. cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/oncology-care-model

- 47.Neuss MN, Desch CE, McNiff KK, et al. A process for measuring the quality of cancer care: the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6233–6239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hanson LC, Collichio F, Bernard SA, et al. Integrating palliative and oncology care for patients with advanced cancer: a quality improvement intervention. J Palliat Med. 2017;20:1366–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Farrugia DJ, Fischer TD, Delitto D, Spiguel LR, Shaw CM. Improved breast cancer care quality metrics after implementation of a standardized tumor board documentation template. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:421–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams CP, Pisu M, Azuero A, et al. Health insurance literacy and financial hardship in women living with metastatic breast cancer. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16:e529–e537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao J, Han X, Zheng Z, Banegas MP, Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR. Is health insurance literacy associated with financial hardship among cancer survivors? Findings from a national sample in the United States. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019;3:pkz061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Given CW, Given BA, Bradley CJ, Krauss JC, Sikorskii A, Vachon E. Dynamic assessment of value during high-cost cancer treatment: a response to American Society of Clinical Oncology and European Society of Medical Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12:1215–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program (NCCCP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. Comprehensive Cancer Control Plans. Accessed September 17, 2020. cdc.gov/cancer/ncccp/ccc_plans.htm

- 54.Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:197–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non—small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1438–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pacific Business Group on Health. PROMOnc. Accessed July 6, 2020. pbgh.org/component/content/article/526

- 60.Alfano CM, Leach CR, Smith TG, et al. Equitably improving outcomes for cancer survivors and supporting caregivers: a blueprint for care delivery, research, education, and policy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:35–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nekhlyudov L, Mollica MA, Jacobsen PB, Mayer DK, Shulman LN, Geiger AM. Developing a quality of cancer survivorship care framework: implications for clinical care, research, and policy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:1120–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.National Quality Forum (NQF). NQF Measure Incubator. Accessed July 6, 2020. qualityforum.org/NQF_Measure_Incubator.aspx

- 63.LeBlanc TW, Abernethy AP. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer care—hearing the patient voice at greater volume. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:763–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Expanding Cost Conversations Between Patients and Their Providers. Accessed February 18, 2020. rwjf.org/en/library/funding-opportunities/2019/expanding-cost-conversations-between-patients-and-their-providers.html

- 65.Arnold Ventures. Arnold Ventures funds efforts to understand problems and identify policy solutions. Accessed February 18, 2020. arnoldventures.org/grants

- 66.Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, et al. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front Public Health. 2019;7:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mayer DK, Nekhlyudov L, Snyder CF, Merrill JK, Wollins DS, Shulman LN. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical expert statement on cancer survivorship care planning. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hunter WG, Zhang CZ, Hesson A, et al. What strategies do physicians and patients discuss to reduce out-of-pocket costs? Analysis of cost-saving strategies in 1,755 outpatient clinic visits. Med Decis Making. 2016;36:900–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bell K, Monak MM, Rothacker A, Whitt A, Kershaw E, LaGasse G. Patient financial burden: considerations for oncology care and access. One organization’s approach to addressing financial toxicity. Managed Care. July/August 2019. Supplement. Accessed July 6, 2020. lsc-pagepro.mydigitalpublication.com/publication/?i=610934&article_id=3454299&view=articleBrowser&ver=html5