Abstract

Background

Hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 suffered initially from high rates of venous thromboembolism (VTE), with possible associations between therapeutic anticoagulation and better clinical outcomes in observational studies.

Objective

To test whether therapeutic anticoagulation improves clinical outcomes in severe COVID‐19.

Patients/Methods

In this multicenter, open‐label, randomized controlled trial, we recruited acutely ill medical COVID‐19 patients with D‐dimer >1000 ng/ml or critically ill COVID‐19 patients in four Swiss hospitals, from April 2020 until June 2021, with a 30‐day follow‐up. Participants were randomized to in‐hospital therapeutic anticoagulation versus low‐dose anticoagulation in acutely ill participants/intermediate‐dose anticoagulation in critically ill participants, with enoxaparin or unfractionated heparins. The primary outcome was a centrally adjudicated composite of 30‐day all‐cause mortality, VTE, arterial thrombosis, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), with screening for proximal deep vein thrombosis.

Results

Among 159 participants, 55.3% were critically ill and 94.3% received corticosteroids. Before study inclusion, pulmonary embolism had been excluded in 71.7%. The primary outcome occurred in 4/79 participants randomized to therapeutic anticoagulation and 4/80 to low/intermediate anticoagulation (5.4% vs. 5.0%; risk difference +0.4%; adjusted hazard ratio 0.76, 95% confidence interval 0.18–3.21), including three deaths in each group. All primary outcomes and major bleeding (n = 3) occurred in critically ill participants. There was no asymptomatic proximal deep vein thrombosis and no difference in major bleeding.

Conclusions

Among patients with severe COVID‐19 treated with corticosteroids and with exclusion of pulmonary embolism at hospital admission for most, risks of mortality, thrombotic outcomes, and DIC were low at 30 days. The lack of benefit of therapeutic anticoagulation was too imprecise for definite conclusions.

Keywords: anticoagulants, COVID‐19, heparin, randomized controlled trial, thrombosis

Essentials.

Vascular thromboses including pulmonary microthromboses are characteristic of severe COVID‐19.

This multicenter randomized trial compared different doses of anticoagulation.

Risks of thrombotic complications and death were low in both groups.

The common exclusion of pulmonary embolism before study inclusion may explain these low risks.

1. INTRODUCTION

COVID‐19 has affected >300 million humans and caused >5 million deaths. The lack of specific therapies has led to an intense research effort to evaluate drugs of potential benefit, especially for severe COVID‐19 patients with an initial mortality of 10% to 30%. 1 , 2

Early, an unexpectedly high thrombotic burden was found among COVID‐19 patients. Despite standard‐dose thromboprophylaxis, venous thromboembolism (VTE), restricted to proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and pulmonary embolism (PE), occurred in about 9% of COVID‐19 patients, with greatest risks in the intensive care unit (ICU). 3 , 4 A prevalent tendency for systemic intravascular coagulopathy was also noted. 1 , 5 In parallel, observational studies reported associations of high‐dose heparins with better survival in COVID‐19 patients, compared with standard low‐dose thromboprophylaxis, 1 , 6 , 7 leading to empiric decision in some hospitals or guidance documents to administer higher doses of anticoagulants. 8 Heparins may have multiple theoretical benefits in severe COVID‐19, with potential reduction of thrombosis, systemic inflammation, and perhaps antiviral effects. 9 However, given the bleeding hazards of therapeutic anticoagulation and the possibility of confounding and bias from observational studies, there is a critical need for high‐quality interventional randomized trials evaluating the benefit–risk of different dosages of anticoagulation in patients with COVID‐19.

To inform the decision of anticoagulation for severe COVID‐19 patients, at least 20 randomized trials were started early in the epidemic. 10 Several have been reported already and have brought some answers. In particular, large international multiplatform trials have shown a possibly differential effect of therapeutic anticoagulation over low‐ or intermediate‐dose anticoagulation, with a benefit among noncritically ill but not among critically ill COVID‐19 patients, with regard to a combined endpoint of survival and the need for organ support. 11 , 12 Intermediate‐dose anticoagulation was not beneficial, compared with low‐dose anticoagulation, among critically ill patients in Iran in the INSPIRATION trial. 13 In noncritically ill patients, two other trials have suggested a benefit of therapeutic anticoagulation, with a reduction of a combined endpoint of VTE and mortality in the HEP‐COVID trial 14 and with a reduction of mortality as a secondary outcome in the RAPID trial. 15 Three other trials of smaller sample sizes have not shown benefits of increased doses of anticoagulation in COVID‐19 inpatients. 16 , 17 , 18 Here, we report the COVID‐HEP study, a Swiss multicenter randomized trial comparing different doses of heparins during hospital stay.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

The COVID‐HEP study is a multicenter, superiority, open‐label, investigator‐initiated, randomized controlled trial of therapeutic‐dose vs. low‐ or intermediate‐dose anticoagulation for hospitalized patients with microbiologically proven severe COVID‐19. The trial was set in two university hospitals (Geneva, Lausanne) and two nonuniversity hospitals (Sion, Locarno) in Switzerland. The local ethics committees of the centers approved the study and informed consent was obtained from all participants or their relatives, if a personal consent was unfeasible. The protocol and statistical analytic plan can be found as Supporting Information.

2.2. Participants

Study centers screened patients hospitalized for an acute severe COVID‐19, proven by a positive polymerase chain reaction or antigenic test, in internal medicine wards, intermediate care units, and/or ICUs. The definition of severe disease required either an admission D‐dimer level >1000 ng/ml for acute medical wards, or a hospitalization in intermediate care/intensive care units (ICU). Generally, clinical criteria for admission to intermediate care/ICU were a fraction of inspired oxygen >50% with a O2 saturation <90%, mostly to start high‐flow O2. Patients were eligible for study inclusion within 48 h of hospital admission or of transfer to intermediate/ICU. Exclusion criteria, detailed in the study protocol (found online), included ongoing therapeutic anticoagulation for any indication other than COVID‐19, contraindication to therapeutic anticoagulation, a high risk of bleeding, ongoing pregnancy, extreme body weight (<40 kg and >150 kg), and participation in another clinical trial.

D‐dimer levels were measured with enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (VIDAS D‐Dimer Exclusion II, Biomérieux) or quantitative latex immunoturbidimetric assays (HemosIL D‐Dimer HS, Instrumentation Laboratory; Innovance D‐dimer, Siemens), depending on the study center. Their normal range is <500 ng/ml for the diagnostic evaluation of DVT.

2.3. Randomization and masking

Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) to therapeutic anticoagulation (high‐dose) or low‐/intermediate‐dose anticoagulation, using a central, concealed, web‐based randomization system. We used randomly selected block sizes between two and six, stratified by study center and severity (acutely ill medical vs. critically ill). Outcome adjudicators were blinded to the group allocation, but participants and investigators were not.

2.4. Procedures

2.4.1. Intervention group

Therapeutic anticoagulation was either enoxaparin 1 mg/kg twice daily, with anti‐Xa assay monitoring in case of extreme weight (<50 kg or >100 kg) or renal clearance <50 ml/min, or therapeutic intravenous unfractionated heparin in case of renal clearance <30 ml/min or upon physician preference, with anti‐Xa unfractionated heparin (UFH) monitoring for dose titration.

2.4.2. Control group

We used different dosages for prophylactic anticoagulation for acutely ill medical participants (hospitalized in medical wards) and for critically ill participants (hospitalized in intermediate care units or ICUs), in agreement with local practices and French recommandations. 19 Acutely ill medical participants received low‐dose weight‐based once‐daily enoxaparin (20 mg if 40–49.9 kg, 40 mg if 50–99.9 kg, 60 mg if ≥100 kg), or subcutaneous UFH (5000 IU twice daily if <100 kg, three times daily if ≥100 kg) in case of renal clearance <30 ml/min. Critically ill participants received intermediate‐dose, weight‐based regimens, with twice‐daily enoxaparin (40 mg if 40–99.9 kg, 60 mg if ≥100 kg), or intravenous or subcutaneous UFH (15,000 IU daily if <100 kg, 20,000 IU if ≥100 kg). In case of transfers between wards, doses were adapted.

2.4.3. Procedures

Study treatment was stopped at the first occurrence of the following: hospital discharge (to home or a rehabilitation facility), in‐hospital clinical improvement (48 h after withdrawal of oxygen supplementation without fever), or study end at 30 days. Thereafter, the use of anticoagulation was left at the discretion of the in‐charge physician. Compliance was calculated as the number of days with the appropriate drug and dose over the total number of days of active intervention.

Participants were followed at 5, 10, and 15 days after inclusion with in‐person visits if still in the hospital, and at the end of study at 30 days after inclusion, with in‐person visit or phone call in case of discharge.

One screening bilateral compression ultrasound (CUS) of the proximal veins of the lower limb was planned between days 5 and 10. Experienced vascular physicians imaged the common and superficial femoral veins and the popliteal veins until the venous trifurcation.

2.5. Outcomes

The primary outcome was a composite of 30‐day VTE, arterial thrombosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and all‐cause mortality. VTE was defined as an objective segmental or more proximal PE diagnosed on computed tomography pulmonary angiography or lung scintigraphy, and/or objectively diagnosed proximal lower extremity DVT, symptomatic distal lower extremity DVT, or noncatheter‐related proximal upper extremity DVT. As such, subsegmental PE and asymptomatic distal DVT were excluded because of their uncertain clinical relevance. Arterial thrombosis was defined as acute myocardial infarction, acute ischemic stroke, or acute limb ischemia using objective imaging and biomarker criteria. We used the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) definition for DIC. 20 The motivation to include DIC in the primary outcome followed early COVID‐19 literature suggesting an important role in 10% to 30% of severe cases. 1 , 5 Detailed definitions of DIC and the bleeding criteria are found in the Protocol (Supporting Information).

Secondary outcomes included the individual components of the primary outcome, asymptomatic proximal DVT diagnosed through screening CUS, duration of hospitalization, of ICU stay, and of mechanical ventilation (MV) support. We also examined clinical deterioration among acutely ill medical, which we a priori defined as an admission to the intermediate/ICU, the use of invasive or noninvasive ventilation, the use of high‐flow oxygen or the use of an inspired fraction of oxygen >50%. We had planned as secondary outcomes the occurrence of sepsis‐induced coagulopathy, acute respiratory distress syndrome, the sequential organ failure assessment score, and respiratory ratios in the ICU, which were captured partially in the dataset and not analyzed or will be reported in a future manuscript. In a post hoc exploratory analysis, we also considered the risk of invasive MV or death at 30 days, among participants without invasive MV at baseline, as was done in other clinical trials.

Safety outcomes were major bleeding and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding (CRNMB), according to their ISTH definition, 21 , 22 and confirmed heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia, as defined by the 2020 French recommendations. 23

All thrombotic and bleeding events were independently and centrally adjudicated by two expert VTE clinicians, in a blinded fashion.

We defined serious adverse events as severe events that were unexpected in severe or critically ill inpatients, excluding the primary and safety outcomes except fatalities.

2.6. Sample size and study interruption

At the time of study design, we hypothesized an incidence of the composite primary outcome of 40% from early data from Wuhan. 24 We estimated a 50% relative reduction with therapeutic anticoagulation, which was associated with a 24% absolute lower mortality among patients with severe COVID‐19. 1 The sample size of 200 (100 in each arm) was determined with an alpha of 5%, a power of 80%, and a 10% loss of follow‐up.

There was no formal interim statistical analysis. We suspended inclusions of ICU patients from December 30, 2020, until February 2, 2021, based on preliminary reports of the multiplatform study suggesting a lack of benefit of therapeutic anticoagulation in ICU patients, 11 and resumed enrollment following the advice of the Data and Safety Monitoring Board. On June 2, 2021, the Steering Committee decided to prematurely stop the trial because of low recruitment, in agreement with the data and safety monitoring board. At that time, 40% of the Swiss population had received at least one dose of mRNA vaccine, and hospitalization rates for COVID‐19 had dropped to low levels, affecting the potential for recruitment dramatically.

2.7. Statistical analysis

All primary and secondary efficacy outcomes were analyzed according to the intention‐to‐treat method. Safety outcomes were analyzed in a per‐protocol fashion, with only participants who had received at least one appropriate dose of study drug. Outcomes were compared between study groups by using survival data analysis: Kaplan‐Meier approach to estimate survival probabilities and Cox regression models to assess hazard ratios (HRs). Participants lost to follow‐up or who had withdrawn consent were censored at the day of last news. The 30‐day cumulative risks were reported with 95% confidence interval (CI) based on the complementary log‐log transformation. 25 For outcomes with no observed event, 95% CIs were obtained by the Clopper‐Pearson exact method and ignoring information of censored participants. The 95% CI of 30 days’ risk difference between study groups was obtained by a parametric bootstrap approach. The HR for the primary outcome was adjusted on the baseline ward type and on a propensity score to account for potential imbalance in risk factors (age, sex, hypertension, body mass index [BMI], diabetes, active smoking, history of previous VTE, cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, chronic renal disease) between study groups. Adjustment was predefined, but simplified during the course of the study, before comparative analyses, in view of the small number of events (see Statistical Analytic Plan as Supporting Information). We also used survival data analysis to compare the times to hospital discharge (among the whole sample), to ICU discharge (among participants included in the ICU) and to MV weaning (among participants with MV at baseline).

Based on descriptive analyses showing a low incidence of the primary outcome, we restricted the planned subgroups to acutely ill medical versus critically ill participants at baseline and baseline D‐dimer levels with a cutoff of 4 times the norm, to align with other studies (<2000 vs. ≥2000 ng/ml).

Missing data were not imputed. All statistical analyses were conducted on R software, version 4.0.2, and all statistical tests were two‐sided with a significance level of 5%.

3. RESULTS

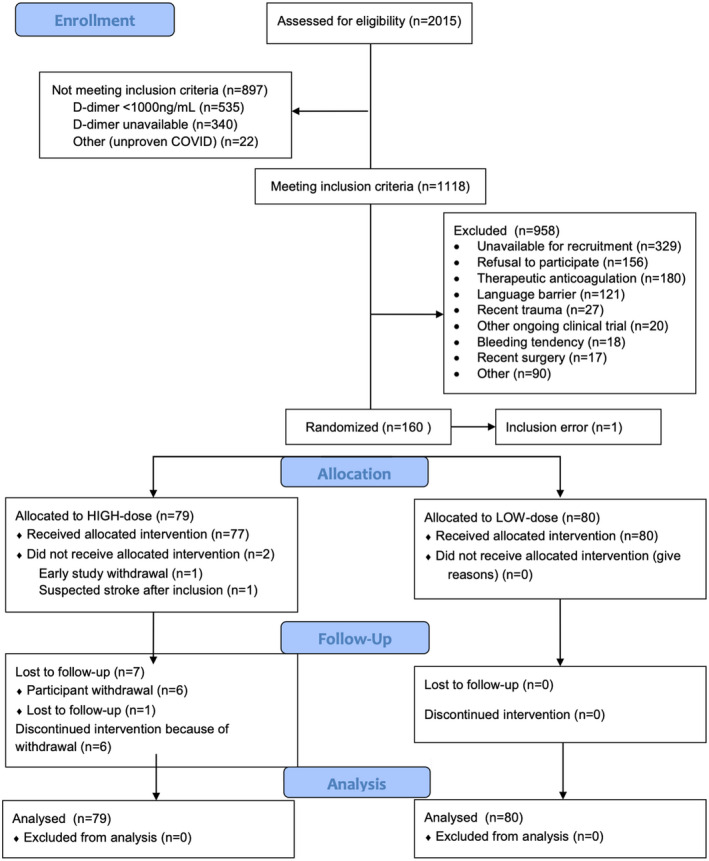

Between April 2020 and June 2021, 1118 patients (55.5%) of 2015 screened patients met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). After the exclusion of 958 patients and one randomization error, 159 participants were randomized. Six participants from the therapeutic‐dose group withdrew consent after a median of 11.5 days and one participant was lost to follow‐up after 9 days.

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT flowchart of the study. Inclusion error is the result of the wrong randomization of a COVID‐19 patient who had not been included in the study

Inclusion occurred at medians of 1 day after hospital admission and of 10 days after start of COVID‐19 symptoms. Baseline characteristics were well‐balanced between groups, with a mean age of 62.5 years and BMI of 28.6 kg/m2, and a majority of men (69.8%; Table 1 and Table S1). Participants were acutely ill medical (44.7%) and critically ill (55.3%) patients, and 52.2% were treated with high‐flow oxygen, noninvasive ventilation, and/or MV. Median (interquartile range [IQR]) D‐dimer levels at inclusion were 1361 (1031–1840) in the therapeutic anticoagulation group and 1324 (862–1926) in the control group. Corticosteroids were administered in 94.3% at baseline. In 71.7%, PE had been formally excluded by standard clinical care before study inclusion, by computed tomography pulmonary angiography or D‐dimer levels below the age‐adjusted cutoff.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the participants, stratified by randomization groups

| Therapeutic‐dose anticoagulation (N = 79) | Low‐/intermediate‐dose anticoagulation (N = 80) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 62.1 (11.9) | 62.9 (12.2) |

| Men | 56 (70.9%) | 55 (68.8%) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 63 (79.7%) | 71 (88.8%) |

| Black | 8 (10.1%) | 1 (1.2%) |

| Hispanic | 7 (8.9%) | 6 (7.5%) |

| Asian | 1 (1.3%) | 2 (2.5%) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.5 (4.8) | 27.8 (4.8) |

| Diabetes | 10 (12.7%) | 20 (25.0%) |

| Active smoking | 2 (2.5%) | 6 (7.5%) |

| Hypertension | 31 (39.2%) | 27 (33.8%) |

| History of VTE | 6 (7.6%) | 1 (1.2%) |

| Previous cardiovascular disease | 4 (5.1%) | 11 (13.8%) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 9 (11.4%) | 10 (12.5%) |

| Active cancer | 5 (6.3%) | 5 (6.2%) |

| Duration of COVID‐19 symptoms before inclusion, days | 9.6 (4.5) | 9.9 (4.4) |

| Duration of hospitalization before inclusion, days | 2.7 (4.2) | 2.2 (2.2) |

| Baseline hospital ward | ||

| Medical ward | 35 (44.3%) | 36 (45.0%) |

| Intermediate care | 21 (26.6%) | 22 (27.5%) |

| Intensive care | 23 (29.1%) | 22 (27.5%) |

| Respiratory support | ||

| None | 2 (2.5%) | 3 (3.8%) |

| Low‐flow oxygen | 34 (43.%) | 37 (46.3%) |

| High‐flow oxygen or noninvasive ventilation | 29 (36.7%) | 31 (38.8%) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 14 (17.7%) | 9 (11.3%) |

| FiO2 at baseline, % | 42.2 (18.0) | 42.1 (17.4) |

| Use of vasopressor | 11 (13.9%) | 7 (8.8%) |

| Use of antiplatelet | 10 (12.7%) | 11 (13.9%) |

| Use of dexamethasone or equivalent | 77 (97.5%) | 73 (91.2%) |

| Use of tocilizumab | 8 (10.1%) | 11 (13.8%) |

| Exclusion of pulmonary embolism before inclusion | 58 (73.4%) | 56 (70.0%) |

| Heart rate, per min | 77.2 (15.8) | 74.3 (13.5) |

| Respiratory rate, per min | 22.8 (5.6) | 21.9 (4.7) |

| Systolic / disastolic Blood pressure, mmHg | 123 (13) / 72 (15) | 126 (17) / 73 (13) |

| Blood group | ||

| O | 26 (32.9%) | 30 (38.9%) |

| A | 25 (31.6) | 23 (29.1%) |

| B | 11 (13.9%) | 5 (6.3%) |

| AB | 5 (6.3%) | 1 (1.3) |

| Missing | 12 (15.2%) | 20 (25.3%) |

| D‐dimer, ng/ml | 1706 (1540) | 1678 (1441) |

| D‐dimer ≥2000 ng/ml (≥4 times the norm) | 14 (18.7%) | 18 (24.3%) |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | 6.4 (1.8) | 6.7 (3.5) |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 137.9 (16.6) | 133.9 (15.7) |

| Platelets, G/L | 245.5 (110.3) | 268.3 (114.6) |

| Creatinine, µmol/L | 83.4 (30.8) | 80.4 (32.1) |

| ALT, U/L | 52.5 (36.0) | 58.1 (61.3) |

| C‐reactive protein, mg/L | 123.9 (85.2) | 111.9 (76.1) |

Continuous variables in mean (SD), categorical variables in % (n).

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; VTE, venous thrombotic embolism.

3.1. Study intervention

Overall, 81% of participants had a compliance ≥80%. Mean compliances were 87% and 93% and median durations were 9 days (IQR 5.5–14) and 9 days (IQR 6–14.2), in the therapeutic anticoagulation group and control group, respectively. There were 21/159 participants (13.2%) who did not receive the study drugs at the exact dose according to the protocol for >48 h during the study period, well balanced within both groups (12.5% and 13.9%). Two participants were excluded from per‐protocol analyses in the therapeutic anticoagulation group because they did not receive any study drugs.

3.2. Efficacy outcomes

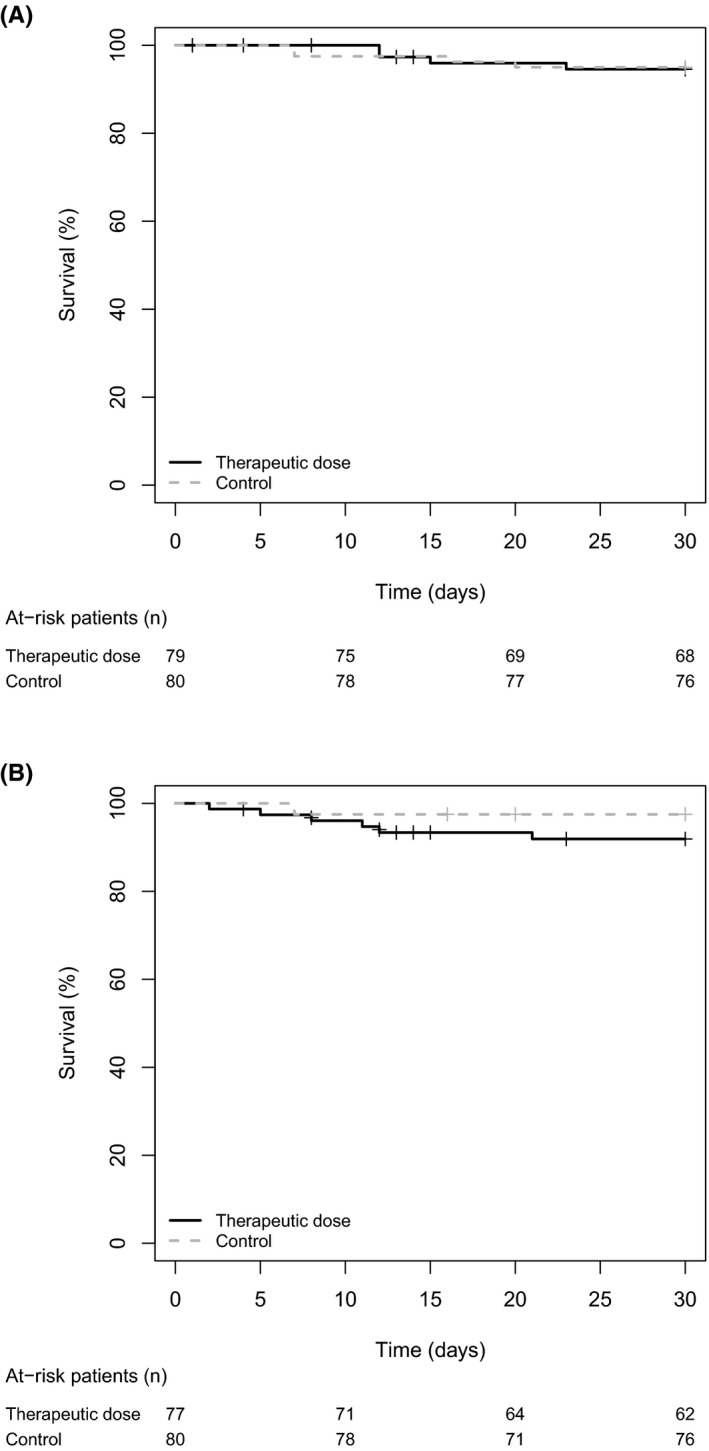

At 30 days, the primary composite outcome occurred in 4/79 (30‐d cumulative risk of 5.4%) participants in the therapeutic‐dose group versus 4/80 (30‐d cumulative risk of 5.0%) in the control group (risk difference +0.4%; adjusted HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.18–3.21; Table 2 and Figure 2). Three participants in the therapeutic‐dose and three in the control group died (4.1% vs. 3.7%). There were two ischemic strokes in the therapeutic‐dose group and one ischemic stroke and one symptomatic PE with proximal DVT in the control group (Table S2). There was no event of DIC, myocardial infarction, or acute limb ischemia during the study period.

TABLE 2.

Risks of the primary outcome and its components and of safety outcomes

| Efficacy outcome a | 30‐day cumulative risk | Risk difference | HR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic dose (n = 79) | Low/intermediate dose (n = 80) | Absolute risk difference (95%CI) | Unadjusted HR (95%CI) | Adjusted HR (95%CI) b | p value | |

| Composite primary outcome |

5.4% (4/79) (95% CI 2.1–13.9) |

5.0% (4/80) (95% CI 1.9–12.8) |

+0.4% (95% CI −7.9 to 9.3) |

1.08 (95% CI 0.27–4.31) |

0.76 (95% CI 0.18–3.21) |

0.70 |

| Components of the primary outcome | ||||||

| VTE |

0.0% (0/79) (95% CI 0.0–5.0) |

1.2% (1/80) (95% CI 0.2–8.5) |

−1.2% (95% CI not estimable) |

|||

| Mortality |

4.1% (3/79) (95% CI 1.3–12.2) |

3.7% (3/80) (95% CI 1.2–11.2) |

+0.4% (95% CI −7.3 to 8.6) |

|||

| DIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Arterial thrombosis |

1.3% (1/79) (95% CI 0.2–9.1) |

2.5% (2/80) (95% CI 0.6–9.7) |

−1.2% (95% CI −8.2 to 6.6) |

|||

| Safety outcome c | 30‐day cumulative risk | Risk difference | HR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic dose (n = 77) | Low/intermediate dose (n = 80) | Absolute risk difference (95%CI) | Unadjusted HR (95%CI) | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | p value | |

| Major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding |

8.1 (6/77) (95% CI 3.7–17.2) |

2.5% (2/80) (95% CI 0.6–9.6) |

+5.6% (95% CI −2.7 to 14.7) |

3.26 (95% CI 0.66–16.18) |

0.15 | |

| Major bleeding |

1.4% (1/77) (95% CI 0.2–9.2) |

2.5% (2/80) (95% CI 0.6–9.6) |

−1.1% (95% CI −8.1 to 6.8) |

0.52 (95% CI 0.05–5.78) |

0.60 | |

Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; HR, hazard ratio; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Intention‐to‐treat analysis.

Adjusted for the ward at inclusion and a propensity score combining age, sex, hypertension, body mass index, diabetes, smoking, previous VTE, previous cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, and chronic renal disease.

Per‐protocol analysis, excluding two participants who did not receive any study drug

FIGURE 2.

Survival curves (Kaplan–Meier estimates) of (A) the primary efficacy outcome (intention‐to‐treat analysis) and (B) the safety outcome major or clinically relevant bleeding (per protocol analysis). Censored data are represented by crosses. In the analysis of the safety outcome, follow‐up of patients who died was censored at the time of death

The screening lower limb CUS of the proximal veins was performed in 73 (92.4%) participants in the therapeutic‐dose group and 71 (88.8%) in the control group, at a median of 7 days after inclusion. No isolated asymptomatic DVT was found. Three participants (two therapeutic dose, one low/intermediate dose) had VTE events that did not fulfill the study definition for VTE (catheter‐related jugular DVT; asymptomatic distal DVT [protocol violation of the CUS]; subsegmental PE). Further, 26 participants (16.4%) had a computed tomography pulmonary angiography that was negative at the segmental or more proximal level.

The estimated median times to hospital discharge, ICU discharge, and MV weaning were 11 versus 10 days, 8.5 versus 7 days and 9 versus 9 days, in the therapeutic‐dose group versus the control group (survival curves in Figure S1). Corresponding adjusted HRs were 0.84 (95% CI 0.60–1.18), 0.72 (95% CI 0.37–1.39), and 0.71 (95% CI 0.27–1.85), respectively (HR < 1 indicating a lower risk of discharge or weaning).

Among the acutely ill medical participants at baseline (n = 71), eight deteriorated clinically in the therapeutic‐dose group (23.1% at 30 days) and six in the control group (16.7% at 30 days), without a statistically significant difference (adjusted HR = 1.48, 95% CI 0.46–4.78, p = 0.52; Table 3 and Figure S2). Among participants without invasive mechanical ventilation at baseline, the risk of invasive mechanical ventilation or death at 30 days was greater with therapeutic anticoagulation (12/65, 30‐day cumulative risk of 18.9%) than with low/intermediate anticoagulation (6/71, 30‐day cumulative risk of 8.5%; adjusted HR = 4.10, 95% CI 1.40–12.03, p = 0.01).

TABLE 3.

Predefined clinical deterioration and its components among acute medical participants at baseline (intention‐to‐treat analysis)

| Cumulative risk at 30 days (95% CI) | Difference (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic anticoagulation (n = 35) | Low‐dose anticoagulation (n = 36) | |||

| Combined clinical deterioration |

23.2% (8/35) (95% CI 12.3–41.0) |

16.7% (6/36) (95% CI 7.9–33.4) |

+6.6% (95% CI −7.9 to 9.3) |

1.48 (95% CI 0.46–4.78) |

| 1. Transfer to ICU/intermediate care unit |

20.3% (7/35) (95% CI 10.2–37.9) |

11.1% (4/36) (95% CI 4.3–26.9) |

+9.2% (95% CI −9.2 to 27.9) |

|

| 2. Use of mechanical or noninvasive ventilation |

8.8% (3/35) (95% CI 2.9–24.9) |

0% (0/36) (95% CI 0.0–4.5) |

+8.8% (95% CI not estimable) |

|

| 3. Use of high‐flow oxygen |

17.2% (6/35) (95% CI 8.1–34.4) |

13.9% (5/36) (95% CI 6.0–30.2) |

+3.4% (95% CI −15.0 to 22.2) |

|

| 4. Use of inspired O2 fraction >50% |

20.3% (7/35) (95% CI 10.2–37.9) |

13.9% (5/36) (95% CI 6.0–30.2) |

+6.4% (95% CI −12.8 to 25.6) |

|

Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; ICU, intensive care unit.

Adjusted for a propensity score combining age, sex, hypertension, body mass index, diabetes, smoking, previous venous thromboembolism, previous cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, and chronic renal disease.

3.3. Safety outcomes

Major bleeding occurred in three participants: 1/77 (1.4%) of the therapeutic‐dose group versus 2/80 (2.5%) of the control group (Table 2). All major bleeding events were nonfatal intracranial bleeding. Five CRNMBs occurred, all in the therapeutic‐dose group, without difference in the risk of combined major and CRNMB between groups (Figure 2). These included two gastrointestinal bleeding, two nasal bleeding, and one intramuscular hematoma (Table S2). There was no heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia.

3.4. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

All primary outcome events occurred in participants who were critically ill at baseline. No acutely ill medical inpatient suffered from a thrombotic event or died in either study group. There was no significant difference in the effect of therapeutic anticoagulation between groups of wards at admission and of baseline D‐dimer, but with low power because of the small numbers of participants and events in subgroups (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Subgroup analyses of the primary efficacy outcome

| Primary efficacy outcome | 30‐day cumulative risk | Risk difference | HR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic anticoagulation (n = 79) | Low‐/intermediate‐dose anticoagulation (n = 80) | Absolute risk difference (95% CI) | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) a | |

| Medical ward (n = 71) |

0% (0/35) (95% CI 0.0–5.0) |

0% (0/36) (95% CI 0.0–4.5) |

0% (95% CI not estimable) |

Not estimable | Not estimable |

| ICU or intermediate care unit (n = 88) |

9.9% (4/44) (95% CI 3.8–24.3) |

9.1% (4/44) (95% CI 3.5–22.4) |

+0.8% (95% CI −13.6 to 16.2) |

1.07 (95% CI 0.27–4.27) |

0.76 (95% CI 0.18–3.21) |

| Baseline D‐dimer <2000 ng/ml (n = 117) |

3.6% (2/61) (95% CI 0.9–13.4) |

7.1% (4/56) (95% CI 2.7–17.9) |

−3.5% (95% CI −14.4 to 7.3) |

0.49 (95% CI 0.09–2.68) |

0.42 (95% CI 0.07–2.40) |

| Baseline D‐dimer ≥2000 ng/ml (n = 32) |

7.1% (1/14) (95% CI 1.0–40.9) |

0% (0/18) (95% CI 0.0–4.5) |

−7.1% (95% CI not estimable) |

Not estimable | Not estimable |

Abbreviations: 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; ICU, intensive care unit.

Adjusted for a propensity score combining age, sex, hypertension, body mass index, diabetes, smoking, previous venous thromboembolism, previous cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, and chronic renal disease.

For bleeding outcomes, all major bleeding and 3/5 CRNMB occurred in participants who were critically ill at baseline.

Serious adverse events occurred in 14/79 (17.7%) participants with therapeutic anticoagulation and 8/80 (10.0%) participants with low‐/intermediate‐dose anticoagulation (Table S3). None was related to study treatment.

4. DISCUSSION

In this Swiss multicenter trial comparing different anticoagulation intensities in severe COVID‐19, the combined risks of thrombotic outcomes, severe coagulopathy, and all‐cause mortality at 30 days were low and unchanged by therapeutic anticoagulation. We did not observe any increased risk of major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding. Among acutely ill medical patients, therapeutic anticoagulation did not statistically or numerically decrease the occurrence of predefined clinical deterioration. However, the imprecise findings of this trial do not exclude meaningful differences between groups and definite conclusions are precluded.

The overall good clinical prognosis of the participants of our study appears better than that of other published trials of anticoagulation in hospitalized COVID‐19, 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 16 , 26 in spite of similar exclusion criteria, a mix of critically ill and acute medically ill participants and similar 12 , 16 or even higher 11 , 13 baseline D‐dimer levels. The 5% 30‐day mortality is lower than in trials in acutely ill medical patients (7%–15%) 12 , 14 , 15 , 26 and in critically ill patients (35%–41%). 11 , 13 , 14 Despite systematic screening for asymptomatic proximal DVT and more participants with ICU‐level respiratory or vasopressor support, only one participant suffered from adjudicated VTE. This contrasts widely with the 28% risk of VTE in the control group of the HEP‐COVID trial, which included participants with greater thrombotic risks because of differences in biological inclusion criteria (elevated D‐dimer >4 times the norm) and demographic characteristics (greater prevalence of obesity and of Black race). Importantly, our study also differs by a stricter definition for VTE, which excluded subsegmental PE, asymptomatic distal DVT, and catheter‐associated DVT and by a central adjudication process.

We hypothesize several reasons for the good prognosis in our study. First, almost all participants received corticosteroids, with a greater proportion than the multiplatform studies, 11 , 12 the HEP‐COVID, 14 and the RAPID 15 trials. Corticosteroids increase survival in severe COVID‐19 and may reduce VTE triggered by systemic inflammation. 27 Second, our definition of VTE was restricted to clinically relevant events, excluding asymptomatic distal DVT, catheter‐related upper limb thrombosis, and subsegmental PE. Third, our trial is the first to report the proportion of exclusion of PE at the time of hospital admission, before study inclusion (72% of participants). This may be a critical explanation of the low VTE risk during the study. Because several reports have suggested that VTE mainly occurs before hospital admission, 28 , 29 we hypothesize that some of the VTE found during the follow‐up of other studies may already have been present at the time of study inclusion. Further, the open‐label design of the COVID‐19 anticoagulation trials is prone to diagnostic suspicion bias, with a higher likelihood of suspicion of VTE in the group receiving a lower anticoagulant dose, perhaps exaggerating differences in VTE rates between groups. In other words, our trial mostly tested the effect of anticoagulation among a selection of patients with a documented lack of PE at hospital admission, and this may be a reason for the unexpectedly low rates of VTE.

In critically ill COVID‐19 patients, our findings of no benefit of a therapeutic anticoagulation over an intermediate anticoagulation complement the findings of the multiplatform ICU trial, the INSPIRATION trial, and the HEP‐COVID trial. 11 , 13 , 14

In acutely ill medical COVID‐19 patients, three studies have shown some benefit of high‐dose anticoagulation, compared with lower doses (multiplatform medical trial, HEP‐COVID study, RAPID study), with decreased clinical deterioration, decreased combined outcome of mortality and thrombotic events, and decreased mortality (in a secondary analysis), respectively. Other trials have not found similar results, but used rivaroxaban instead of low molecular weight heparin (ACTION study 26 ) or had limited statistical power. 17 , 18 The results of our trial do not suggest a benefit on clinical deterioration and treatment escalation of therapeutic anticoagulation, compared with low‐dose anticoagulation in medical patients, but remain imprecise. We await the results of the WHO REACT prospective meta‐analysis of anticoagulation trials, with homogenous definitions and specific subgroups of interest. In particular, this meta‐analysis will increase the precision of the possibly beneficial effect of therapeutic anticoagulation in medical COVID‐19 patients and add power to detect effect modification in specific subgroups to better inform the decision of anticoagulation dose in COVID‐19 inpatients.

The yield of screening for asymptomatic proximal DVT was null in our trial and should not be generalized in clinical practice. This is in agreement with previous prospective studies, the HEP‐COVID, and X‐COVID‐19 trials showing a low prevalence of asymptomatic proximal DVT of 0% to 2.9% among acutely ill medical patients. 14 , 17 , 30 , 31 , 32 In the ICU, we did not find the elevated (5%–23%) risks found by previous prospective studies. 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37

Our trial has several strengths. We conducted active follow‐up after hospital discharge, until 1 month. The use of corticosteroids (94%) was higher than in the other published trials, representing the current standard of clinical care. Compliance with study drugs was evaluated throughout the study period, in contrast with other trials, and was very high in both groups. The outcomes were centrally adjudicated, with a strict clinically relevant definition for VTE and screening for proximal DVT in 90% of participants.

As limitations, we first acknowledge an unbalanced number of participants with study withdrawal, exclusively in the therapeutic‐dose group. This highlights, in part, the discomfort of twice‐daily subcutaneous injections in patients already burdened by their hospital stay and health status. Second, our study design compared therapeutic anticoagulation with intermediate anticoagulation in participants hospitalized in critical and intermediate care units and not to low‐dose anticoagulation. Such heterogeneity of the control group is found in other trials. 11 , 12 , 14 Finally, our study was prematurely terminated at 80% of the planned sample size because of low recruitment with concurrent vaccination effort. Combined with a low number of events and an overestimated effect size in reports from the early pandemic phase, the study power to observe a difference was low. Although no signal of a numeric difference between groups was observed, our null results are not precise enough to be conclusive.

In conclusion, the occurrence of mortality, severe coagulopathy, and thrombotic outcomes was low in this trial of patients with severe COVID‐19. The exact role of therapeutic anticoagulation needs further research in ongoing meta‐analytic efforts.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Marc Blondon, Sara Cereghetti, Jérôme Pugin, Jean‐Luc Reny, Alexandra Calmy, Helia Robert‐Ebadi, Pierre Fontana, Marc Righini, and Alessandro Casini conceived the trial. All authors contributed to the acquisition of data and the interpretation of data for the work. Marc Blondon drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, approved the version to be published, had full access to the data and accepted responsibility to submit for publication. Marc Blondon is the guarantor of the content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis.

RELATIONSHIP DISCLOSURE

All authors declare no competing interests.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded with a grant from the Private Foundation of the Geneva University Hospitals, which had no role in the design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of the data, or in the writing of the report and the decision to submit the paper for publication.

With contributions of the Clinical Research Center, University Hospital and Faculty of Medicine, Geneva.

We thank Cécile Guillot, Tamara Mann, Pauline Gosselin, Lucie Altheer, Floriane Le Petit, Louise Riberdy, Anne‐Claude Hugi (Geneva University Hospitals), and Lynn Tofo, Dr. Bienvenido Sanchez (Hopital du Valais, Sion), Samia Abed Maillard, John‐Paul Miroz, Marie‐Josée Brochu (CHUV, Lausanne) for their work and help in this clinical trial.

Inclusion centers: Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland; Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne, Switzerland; Hôpital du Valais, Sion, Switzerland; Ospedale Regionale di Locarno, Locarno, Switzerland.

We warmly thank also the members of the data and safety monitoring board and of the adjudication committee.

Data and Safety Monitoring Board: Laurent Bertoletti (chair; Service de Médecine Vasculaire et Thérapeutique, CHU de St‐Etienne, Saint‐Etienne, France; INSERM, UMR1059, Equipe Dysfonction Vasculaire et Hémostase, Université Jean‐Monnet, Saint‐Etienne, France; INSERM, CIC‐1408, CHU Saint‐EtienneSaint‐Etienne, France; F‐CRIN INNOVTE network, Saint‐Etienne, France); Henri Bounameaux (Faculty of Medicine, University of Geneva, Switzerland); and François Herrmann (Department of Rehabilitation and Geriatrics, Geneva University Hospitals and Faculty of Medicine, Geneva, Switzerland).

Adjudication Committee: Aurélien Delluc (Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada) and Rolf Engelberger (Division of Angiology, Cantonal Hospital Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland; Faculty of Medicine, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland).

Blondon M, Cereghetti S, Pugin J, et al. Therapeutic anticoagulation to prevent thrombosis, coagulopathy, and mortality in severe COVID‐19: The Swiss COVID‐HEP randomized clinical trial. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2022;6:e12712. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12712

Handling Editor: Dr Lana Castellucci

Contributor Information

Marc Blondon, Email: marc.blondon@hcuge.ch.

Jérôme Pugin, @RenyLuc.

REFERENCES

- 1. Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1094‐1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):934‐943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Longchamp G, Manzocchi‐Besson S, Longchamp A, Righini M, Robert‐Ebadi H, Blondon M. Proximal deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in COVID‐19 patients: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Thromb J. 2021;19(1):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nopp S, Moik F, Jilma B, Pabinger I, Ay C. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID‐19: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4(7):1178‐1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844‐847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nadkarni GN, Lala A, Bagiella E, et al. Anticoagulation, bleeding, mortality, and pathology in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(16):1815‐1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Paranjpe I, Fuster V, Lala A, et al. Association of treatment dose anticoagulation with in‐hospital survival among hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(1):122‐124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fontana P, Casini A, Robert‐Ebadi H, Glauser F, Righini M, Blondon M. Venous thromboembolism in COVID‐19: systematic review of reported risks and current guidelines. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020;150:w20301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bertoletti L, Bikdeli B, Zuily S, Blondon M, Mismetti P. Thromboprophylaxis strategies to improve the prognosis of COVID‐19. Vascul Pharmacol. 2021;139:106883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tritschler T, Mathieu ME, Skeith L, et al. Anticoagulant interventions in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19: A scoping review of randomized controlled trials and call for international collaboration. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(11):2958‐2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. The REMAP‐CAP, ACTIV‐4a, and ATTACC Investigators , Goligher EC, Bradbury CA, et al. Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in critically ill patients with Covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(9):777‐789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. ATTACC Investigators; ACTIV‐4a Investigators; REMAP‐CAP Investigators , Lawler PR, Goligher EC, et al. Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in noncritically ill patients with Covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(9):790‐802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Investigators I, Sadeghipour P, Talasaz AH, et al. Effect of intermediate‐dose vs standard‐dose prophylactic anticoagulation on thrombotic events, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation treatment, or mortality among patients with COVID‐19 admitted to the intensive care unit: the INSPIRATION randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325(16):1620‐1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Spyropoulos AC, Goldin M, Giannis D, et al. Efficacy and safety of therapeutic‐dose heparin vs standard prophylactic or intermediate‐dose heparins for thromboprophylaxis in high‐risk hospitalized patients with COVID‐19: The HEP‐COVID randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(12):1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sholzberg M, Tang GH, Rahhal H, et al. Effectiveness of therapeutic heparin versus prophylactic heparin on death, mechanical ventilation, or intensive care unit admission in moderately ill patients with covid‐19 admitted to hospital: RAPID randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2021;375:n2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Perepu US, Chambers I, Wahab A, et al. Standard prophylactic versus intermediate dose enoxaparin in adults with severe COVID‐19: a multi‐center, open‐label, randomized controlled trial. J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19(9):2225‐2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morici N, Podda G, Birocchi S, et al. Enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized COVID‐19 patients: The X‐COVID‐19 Randomized Trial. Eur J Clin Invest. 2022;52(5):e13735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marcos‐Jubilar M, Carmona‐Torre F, Vidal R, et al. Therapeutic versus prophylactic bemiparin in hospitalized patients with nonsevere COVID‐19 pneumonia (BEMICOP Study): an open‐label multicenter randomized controlled trial. Thromb Haemost. 2022;122(02):295‐299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Susen S, Tacquard CA, Godon A, et al. Prevention of thrombotic risk in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 and hemostasis monitoring. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Iba T, Levy JH, Warkentin TE, et al. Diagnosis and management of sepsis‐induced coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17(11):1989‐1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kaatz S, Ahmad D, Spyropoulos AC, Schulman S, Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation . Definition of clinically relevant non‐major bleeding in studies of anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolic disease in non‐surgical patients: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(11):2119‐2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schulman S, Kearon C, Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis . Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non‐surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(4):692‐694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gruel Y, De Maistre E, Pouplard C, et al. Diagnosis and management of heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2020;39(2):291‐310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054‐1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Borgan O, Liestol K. A note on confidence intervals and bands for the survival function based on transformations. Scand J Stat. 1990;17:35‐41. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lopes RD, de Barros ESPGM, Furtado RHM, et al. Therapeutic versus prophylactic anticoagulation for patients admitted to hospital with COVID‐19 and elevated D‐dimer concentration (ACTION): an open‐label, multicentre, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10291):2253‐2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID‐19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group , Sterne JAC, Murthy S, Diaz JV, et al. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID‐19: a meta‐analysis. JAMA. 2020;324(13):1330‐1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jevnikar M, Sanchez O, Chocron R, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID‐19 at the time of hospital admission. Eur Respir J. 2021;58(1):2100116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lodigiani C, Iapichino G, Carenzo L, et al. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID‐19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res. 2020;191:9‐14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Demelo‐Rodriguez P, Cervilla‐Munoz E, Ordieres‐Ortega L, et al. Incidence of asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis in patients with COVID‐19 pneumonia and elevated D‐dimer levels. Thromb Res. 2020;192:23‐26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fares Y, Sinzogan‐Eyoum YC, Billoir P, et al. Systematic screening for a proximal DVT in COVID‐19 hospitalized patients: Results of a comparative study. J Med Vasc. 2021;46(4):163‐170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tung‐Chen Y, Calderon R, Marcelo C, et al. Duplex ultrasound screening for deep and superficial vein thrombosis in COVID‐19 patients. J Ultrasound Med. 2022;41(5):1095‐1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Galien S, Hultstrom M, Lipcsey M, et al. Point of care ultrasound screening for deep vein thrombosis in critically ill COVID‐19 patients, an observational study. Thromb J. 2021;19(1):38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kapoor S, Chand S, Dieiev V, et al. Thromboembolic events and role of point of care ultrasound in hospitalized Covid‐19 patients needing intensive care unit admission. J Intensive Care Med. 2021;36(12):1483‐1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Longchamp A, Longchamp J, Manzocchi‐Besson S, et al. Venous thromboembolism in critically Ill patients with COVID‐19: results of a screening study for deep vein thrombosis. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4(5):842‐847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nahum J, Morichau‐Beauchant T, Daviaud F, et al. Venous thrombosis among critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e2010478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Voicu S, Bonnin P, Stepanian A, et al. High prevalence of deep vein thrombosis in mechanically ventilated COVID‐19 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(4):480‐482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material