Abstract

Aim:

Many emerging adults disengage from early intervention in psychosis (EIP) services prematurely. Service disengagement may be in part due to having unresolved treatment decision-making needs about use of mental health services. A basic understanding of the decision-making needs of this population is lacking. The purpose of this qualitative study was to identify the range of treatment decisions that emerging adults face during their initial engagement in an EIP program and elucidate barriers and facilitators to decision-making.

Methods:

Twenty emerging adults with early psychosis were administered semi-structured interviews to capture treatment decision-making experiences during the first six months after enrollment in an EIP program. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Responses were independently coded by two authors using an integrated thematic analysis approach; differences in coding were discussed to consensus. Data analysis was facilitated using NVivo 12 Plus.

Results:

Emerging adults identified numerous decisions faced after EIP enrollment. Decisions pertaining to life and treatment goals and to starting and continuing psychiatric medication were commonly selected as the most difficult/complicated. Decision-making barriers included not having the right amount or type of information/knowledge; social factors (e.g., lacking social support, opposition/pressure); lacking internal resources (e.g., cognitive and communication skills, self-efficacy, motivation); and unappealing options. Obtaining information/knowledge, social supports (e.g., connection/trust, learning from others’ experiences, encouragement), considering personal values, and time were decision-making facilitators.

Conclusions:

This study informs development and optimization of interventions to support decision-making among emerging adults with early psychosis, which may promote service engagement.

Keywords: decision support, shared decision making, service engagement, first-episode psychosis, coordinated specialty care

1. Introduction

Approximately 20–60% of emerging adults aged 18–25 prematurely terminate early intervention in psychosis (EIP) services (Doyle et al., 2014; Mascayano et al., 2020; Mascayano et al., 2021; Reynolds et al., 2019), a risk factor for poorer prognosis (Turner, Smith-Hamel, & Mulder, 2007). Promoting early engagement (Salzer & Kottsieper, 2015) and retention are needed to support better outcomes.

Although mental health treatment decisions are ongoing, emerging adults in EIP may especially face decisions as they first become familiar with the service setting, establish goals, and learn about treatment options. This likely involves considerable decisional conflict - “the simultaneous opposing tendencies…to accept and reject a given course of action” (Janis & Mann, 1977). Given strong associations among decisional conflict and service utilization outcomes (Perez, Menear, Brehaut, & Legare, 2016), engagement enhancements must address factors causing decisional conflict. To our knowledge, no studies have examined these factors during early EIP engagement. Therefore, this study used the evidence-based Ottawa Decision Support Framework (ODSF) (O’Connor et al., 1998) to understand the decision-making needs of emerging adults during this early period.

1.1. Ottawa Decision Support Framework

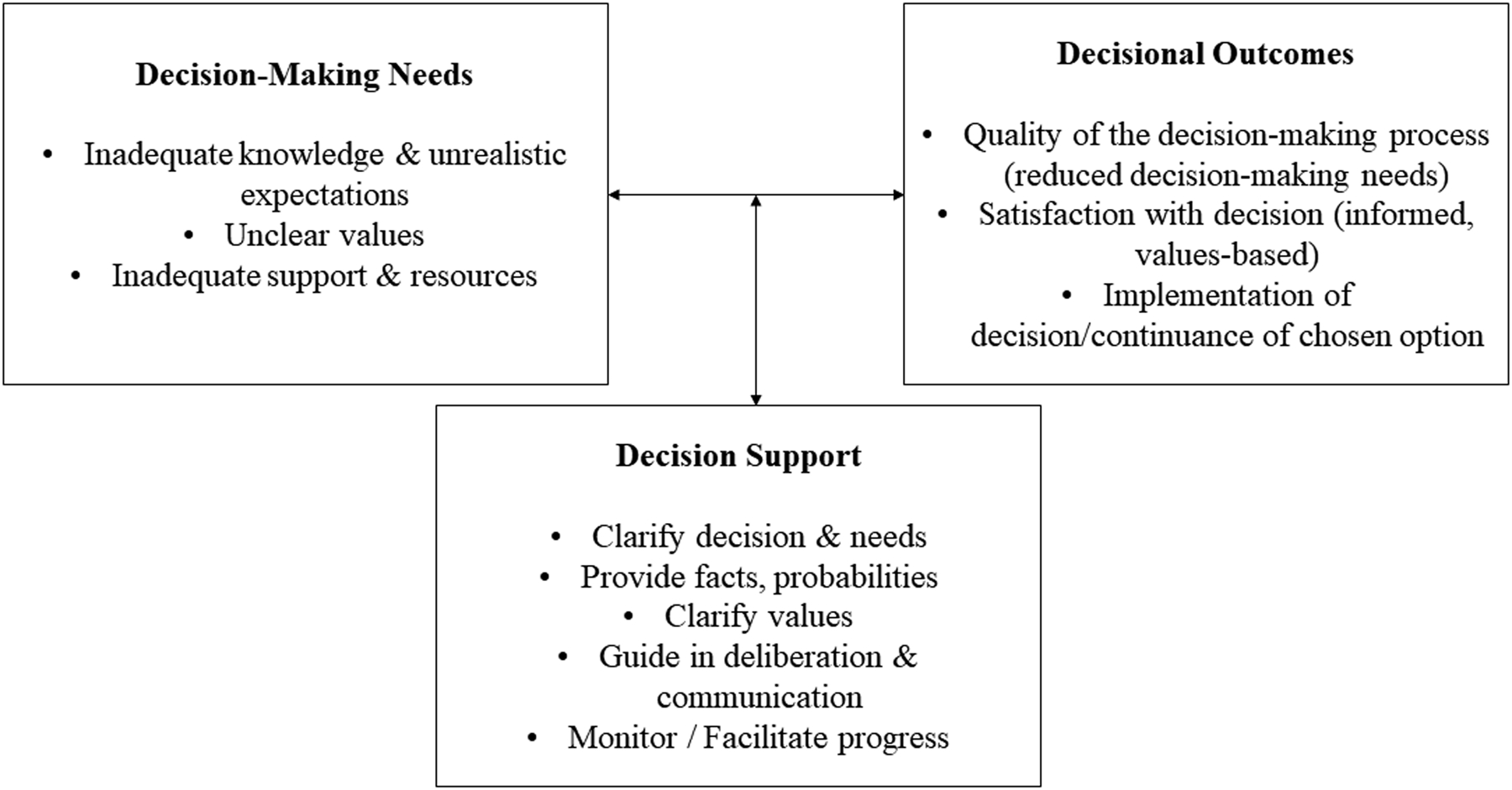

The ODSF is grounded in the construct of decisional conflict, theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991), and social support theories (House, Kahn, McLeod, & Williams, 1985; Kahn, 1994). It specifies several modifiable decision-making needs (Figure 1; Box 1) cause decisional conflict: knowledge deficiencies; uncertain personal values; low social support or high social pressure; lack of internal (e.g., motivation, self-efficacy) or tangible (e.g., money) resources needed for decision-making. Various components of decision support, e.g., facilitating access to information and clarifying values (Figure 1; Box 2), lead to improved decisional outcomes (Figure 1; Box 3), including decision quality, satisfaction, and implementation.

Figure 1.

Ottawa Decision Support Framework

The ODSF shares similarities with other theories used to understand treatment decision-making among young people with mental illnesses. The Unified Theory of Behavior incorporates social and psychological theories to identify cognitive (e.g., behavioral beliefs), socio-environmental (e.g., social norms), and emotional variables linked to intentions and behavior (Jaccard, Dodge, & Dittus, 2002). The Network Episode Model highlights molecular, personal, social, institutional, and community factors influencing decision-making across the illness career (Munson et al., 2012; Pescosolido, 1992). The Theoretical Domains Framework (Cane, O’Connor, & Michie, 2012) explicates drivers of active engagement in treatment decision-making (e.g., knowledge, skills, motivation, social/environmental influences) (Hayes, Edbrooke-Childs, Town, Wolpert, & Midgley, 2020). The ODSF was selected for this study given its concordance with these theories and added utility for understanding and addressing decisional conflict.

1.2. Extant Literature

Treatment decision-making studies with emerging adults experiencing serious mental illnesses (not in EIP) have focused on help-seeking and service utilization (Munson et al., 2012; Simmons, Batchelor, Dimopoulos-Bick, & Howe, 2017), and medication-related decisions (Delman, Clark, Eisen, & Parker, 2015). Literature with adults experiencing mental illnesses highlight decisions related to social determinants of health, including lifestyle modifications (e.g., exercise, social activities), mental illness disclosure, employment/education, and living arrangements (Bassett, Lloyd, & Bassett, 2001; Lucas, Skokowski, & Ancis, 2000; Pahwa, Fulginiti, Brekke, & Rice, 2017; Stacey et al., 2008). Given their relatively new experience of psychosis and treatment, the developmental characteristics of emerging adulthood, and the multi-faceted nature of EIP, this broader literature likely does not reflect the most prominent challenges that emerging adults face in EIP care. The field needs to ascertain decision points that are particularly challenging for this population, so as to offer concentrated support around them.

Identifying factors complicating and facilitating decision-making for these emerging adults is also needed. Based on the aforementioned theories, qualitative literature outside the EIP context suggests informational barriers and supports (e.g., (in)sufficient information), service user challenges and strengths (e.g., psychiatric symptoms, self-efficacy), service user-treatment interaction characteristics (e.g., (mis)trust), social factors (e.g., family involvement in decision-making), and logistical issues (e.g., transportation) (Delman et al., 2015; Fisher, Manicavasagar, Sharpe, Laidsaar-Powell, & Juraskova, 2018; Gondek et al., 2017; Grim, Rosenberg, Svedberg, & Schon, 2016; Hayes et al., 2020; Lal, Nguyen, & Theriault, 2018; Mikesell, Bromley, Young, Vona, & Zima, 2016; Munson et al., 2012; Simmons, Hetrick, & Jorm, 2011; Stacey et al., 2008; Stovell, Wearden, Morrison, & Hutton, 2016). How relevant these are to emerging adults in EIP, and implications for intervention, remain to be determined.

Using an interpretive/constructivist epistemological approach (Merriam, 2009), this qualitative study addresses these knowledge gaps by eliciting emerging adults’ perspectives about challenging decision points during initial EIP engagement and their experience of decision-making barriers and facilitators.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

We recruited participants via flyers, presentations, and EIP staff referrals from an urban EIP program in the northeast United States. Inclusion criteria were: 1) 18–25 years; 2) experiencing early psychosis (i.e., ≤ 18 months); 3) able to speak/understand English and provide informed consent; and 4) enrolled in the EIP program ≥ 6 months. Minimizing fixed influences on decision-making that were not the study focus and increasing successful engagement in the qualitative interview, exclusion criteria were: having a legal guardian; or diagnosis of dementia, delirium, or intellectual disability.

We utilized a stratified purposeful sampling design to maximize selection of information-rich participants and optimize variations in data (Palinkas et al., 2015). Participants’ primary clinicians completed the multi-dimensional Service Engagement Scale (Tait, Birchwood, & Trower, 2002). Then, we grouped participants into below average, average, and above average levels of service engagement using recommended total score cutoffs (Tait et al., 2002). Targeted recruitment of underrepresented groups occurred as necessary to obtain a well-mixed sample.

2.2. Setting

The EIP program’s multidisciplinary team offered multi-faceted and holistic services (e.g., recovery-oriented cognitive behavioral therapy, family education/support, supported employment/education, medication management) and collaborative treatment planning consistent with EIP best practices commonly available in the U.S. (White, Luther, Bonfils, & Salyers, 2015).

2.3. Procedures

We followed recommendations for conducting decision needs assessments from the ODSF (Jacobsen, O’Connor, & Stacey, 2013), decision-making literature, and a lived experience advisory board to develop a qualitative interview guide (see appendix). It focused on decision points experienced during the first six months after EIP enrollment and barriers and facilitators associated with participants’ most difficult/complicated decisions.

Interviews, conducted one-on-one by either the first or second author, were one-hour long, audio-recorded, and professionally transcribed after written informed consent. Following each, field notes were recorded. Participants could review their transcripts and make additions, deletions, or clarifications prior to data analysis. Only one returned comments; these did not change the content or meaning of the data. Participants also completed a demographics measure. All study procedures received approval from the relevant Institutional Review Boards (reference numbers: 25075 and 2018–16) and conformed to ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.4. Data Analysis

We used an integrated thematic analysis approach, enabling inductive and deductive coding (Bradley, Curry, & Devers, 2007). Initial analysis began after the third interview. The first and second authors proofread each transcript while making notes regarding decision-making, then created an initial draft of coding categories, reviewed by all study authors. Using the Constant Comparison Method (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), the first and second authors independently coded each transcript, discussing differences to consensus, sometimes creating new codes or collapsing existing ones. After refining the code list, the final coding of each interview was double-checked for accuracy. The first author then used a hierarchical coding tree to consolidate codes into broader categories aligned with the ODSF; this was reviewed by the second author and any disagreements were again discussed to consensus. Finally, we performed subgroup analyses by examining frequencies of reported barriers/facilitators within each engagement group. Strategies to ensure rigor (Padgett, 2012) included multiple coders and auditing by the third author, an experienced qualitative researcher. Qualitative analysis was facilitated using NVivo 12 Plus.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Thirty individuals were screened. Eight were ineligible (five ≥ 25 years, three had legal guardians). Two others declined to participate. In the final sample (N=20; see Table 1 for participant characteristics), four were rated as having “below average” engagement, nine as “average,” and seven as “above average.” We determined that 20 participants provided sufficient “information power” to elucidate the aims of the study (Malterud, Siersma, & Guassora, 2015).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants (N=20)

| Variable | N (%) | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Men | 13 (65) | ||

| Women | 5 (25) | ||

| Non-Binary | 1 (5) | ||

| Gender-Exclusive | 1 (5) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity† | |||

| Black | 16 (80) | ||

| White | 3 (15) | ||

| Hispanic | 5 (25) | ||

| Asian | 2 (10) | ||

| Other | 3 (15) | ||

| Education (years) | 12.10 | 1.74 | |

| Age (years) | 20.20 | 2.26 | |

| Currently Working for Pay‡ | 4 (21) | ||

| Currently a Student | 9 (45) | ||

| Lifetime Arrests | .70 | .92 |

Categories are not mutually exclusive.

N=19

3.2. Decision Points

Participants identified a range of decisions during early EIP engagement (Table 2). Decisions about life and treatment goals and about medications were most frequently identified as participants’ most difficult/complicated decisions.

Table 2.

Decision Points Reported during Early Engagement in EIP

| Decision Points About… | N (%) Mentioning Decision | N (%) Indicating Decision Most Difficult/Complicated | Exemplar Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment/life goals (e.g., work or go to school first?) † | 19 (95%) | 6 (30%) |

. |

| Whether to continue taking medication | 10 (50%) | 3 (15%) |

. |

| Changing medications (e.g., switch from pills to injectables?) | 17 (85%) | 2 (10%) |

. |

| Participating in program social activities (e.g., go to groups?) | 15 (75%) | 2 (10%) |

. |

| Whether to continue in the EIP program | 14 (70%) | 2 (10%) |

. |

| Whether to start medication | 11 (55%) | 2 (10%) |

. |

| Whether to continue specific EIP service (non-pharmacological) | 7 (35%) | 1 (5%) |

. |

| Self-disclosure (e.g., open up to therapist?) | 6 (30%) | 1 (5%) |

. |

| Using external mental health/medical services | 3 (15%) | 1 (5%) |

. |

| Involving family in the EIP program | 13 (65%) | 0 (0%) |

. |

| Level of involvement in EIP program (e.g., how often to come?) | 8 (40%) | 0 (0%) |

. |

| Whether to start therapy | 4 (20%) | 0 (0%) |

. |

| Program participation logistics (e.g., timing of appointments?) | 4 (20%) | 0 (0%) |

. |

| Using information/skills/strategies learned in program in daily life | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

. |

Italicized decisions were those that were specifically asked about during qualitative interviews.

3.3. Barrier Themes

Exemplar quotes for the barrier and facilitator themes below are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Treatment Decision-Making Barriers and Facilitators with Exemplar Quotes

| Information/knowledge barriers (N=15) † | |

| Too much information (N=4) |

. |

| Not enough information (N=14) |

. |

| Negative past experiences bias processing of new information (N=6) |

. |

| Social barriers (N=12) | |

| Lack of trust/connection (N=5) |

. |

| Perceived stigma (N=1) |

. |

| Others unavailable/unreliable (N=2) |

. |

| Opposition/unwanted pressure (N=9) |

. |

| Internal barriers (N=12) | |

| Cognitive challenges (N=1) |

. |

| Communication challenges (N=1) |

. |

| Low self-efficacy (N=2) |

. |

| Low motivation (N=11) |

. . |

| Unappealing options (N=9) | |

| Options inconsistent with preferences/sense of self (N=8) |

. . |

| No apparent benefits of any option (N=3) |

. |

| Information/knowledge facilitators (N=18) | |

| Having desired information |

. . |

| Social facilitators (N=18) | |

| Trust/connection (N=11) |

. . |

| Learning from others’ experiences (N=7) |

. . . . |

| Encouragement (N=14) |

. . |

| Considering personal values (N=13) | |

| Clear sense of personal values |

. . |

| Time (N=3) | |

| Having ample time and space to consider a decision before taking action |

. . |

N = Number of participants endorsing each theme. Ns within each theme are not mutually exclusive.

3.3.1. Information/knowledge barriers

The amount and type of information/knowledge participants had about options was often problematic. Having too much information was associated with confusion, but more participants wanted additional information, with one (#1079) stating “too much information is never a problem.” Not having the right type of information could also cause anxiety and uncertainty. Scarce information created skepticism about treatment and limited perspectives about available options. Some participants described how knowledge from negative past experiences could adversely affect their judgement and processing of new information.

3.3.2. Social barriers

3.3.2.1. Distance from others.

Some participants felt “distance” when they did not know staff well enough to trust them with decision-making discussions. Others reported fellow program participants, with whom they interacted at the clinic, felt like “strangers,” limiting their comfort in sharing decision dilemmas. Many participants wanted others’ involvement in decision-making (e.g., “sometimes it’s better to have another person to talk to about a decision you’re making” (#1066)) and felt “alone” when they lacked support.

3.3.2.2. Others are poor sources of support.

Many participants described feeling under-supported by the people with whom they were close - when others were unavailable, could not be relied on, rigidly opposed their preferences, or unduly pressured them. One participant (#1066) described pressure from multiple people as “too much support.” Such overinvolvement and opposition could lead to decision uncertainty and regret.

3.3.3. Internal barriers

Internal barriers included participants’ cognitive and communication challenges, and low self-efficacy and motivation. Participants especially linked low motivation to delaying decision-making. They reported that decision-making was complicated even when they had some resources but lacked others: “I feel like I’m a real skilled, intelligent person. I just feel like I’m hard-headed, so I need a little push sometimes” (#1079).

3.3.4. Unappealing options

Feeling conflicted made decision-making difficult, especially when participants could identify an option’s benefits yet found it inconsistent with their personal preferences or self-concept. Participants said it was difficult to move past such feelings to make decisions; they would have liked “more options.” Some spoke about difficulty with adjusting their self-image after deciding. Similarly, perceiving little or no benefits associated with options contributed to indecisiveness.

3.4. Facilitator Themes

3.4.1. Information/knowledge facilitators

Obtaining desired information (via EIP staff, program announcements, and the internet) and having the opportunity to evaluate options were named as helpful by almost all participants. They expressed preferences for obtaining information about “more than one option,” learning about their benefits and risks, and receiving comparative information. This information was helpful for increasing the number of perceived options and changing evaluations of these.

3.4.2. Social facilitators

3.4.2.1. Connection.

Being able to discuss decisions with trusted others relieved stress, promoted open-mindedness and confidence, and helped participants feel “less alone.” This was especially important regarding treatment providers and was facilitated by caring gestures and autonomy support. One participant (#1063) said “…being in the hospital, she would come visit. And I learned that she is supportive of me and my decision.” Some participants described feeling more comfortable asking for help and listening to staff advice once they had built relationships.

3.4.2.2. Learning from others’ experiences.

Having opportunities to speak with or observe others who had faced similar decisions was helpful for some, but not all, participants. Often these were family members, fellow EIP participants, or media characters. Learning from others inspired hope, motivation, confidence, and new perspectives about options, although media portrayal of mental health services was not always positive.

3.4.2.3. Encouragement.

For some, encouragement promoted decision clarity. A few participants even indicated that “positive pressure” – consistent, positively-framed messages to make or follow through with a choice – was helpful, giving them the “push” they needed to move forward in the decision-making process.

3.4.3. Considering personal values

Considering decisions in light of personal values and priorities facilitated decision clarity. Personal priorities included: having good (mental) health, getting back to one’s “old self,” being independent, having a romantic relationship, being a good parent, having money, trying new things, being educated, working, pursuing interests, making others proud, staying out of the hospital, and having something worthwhile to do. Keeping these in mind helped participants evaluate options and promoted forward movement.

3.4.4. Time

Having time and space to think about a decision before acting was helpful, as it offered opportunities to speak with others. Being able to have repeated discussions about the same decision also supported decision clarity.

3.5. Subgroup Analyses

There did not appear to be meaningful differences in the degree to which barriers and facilitators were experienced between the three engagement groups (Tables 1–2 of online supplement).

4. Discussion

This study addresses a critical gap in the literature on treatment decision-making among emerging adults with early psychosis. It identifies a range of decisions that young people find difficult during initial EIP engagement, and important barriers and facilitators to decision-making from their lived perspective. Further, through use of a practical decision support framework, this study clarifies how interventions may be developed and optimized to support decision-making and engagement.

Participants described decisions ranging from whether and how to use specific services to how treatment meshes with their personal and long-term goals. Recognizing this diversity is important since decision-making interventions for this population have focused on treatment planning (Browne et al., 2017; Gordon, Gidugu, Rogers, DeRonck, & Ziedonis, 2016) or medication-related decisions only (Robinson et al., 2018). Future research should develop and test decision-making supports applicable to the more complex life-and-treatment decisions identified by interviewees.

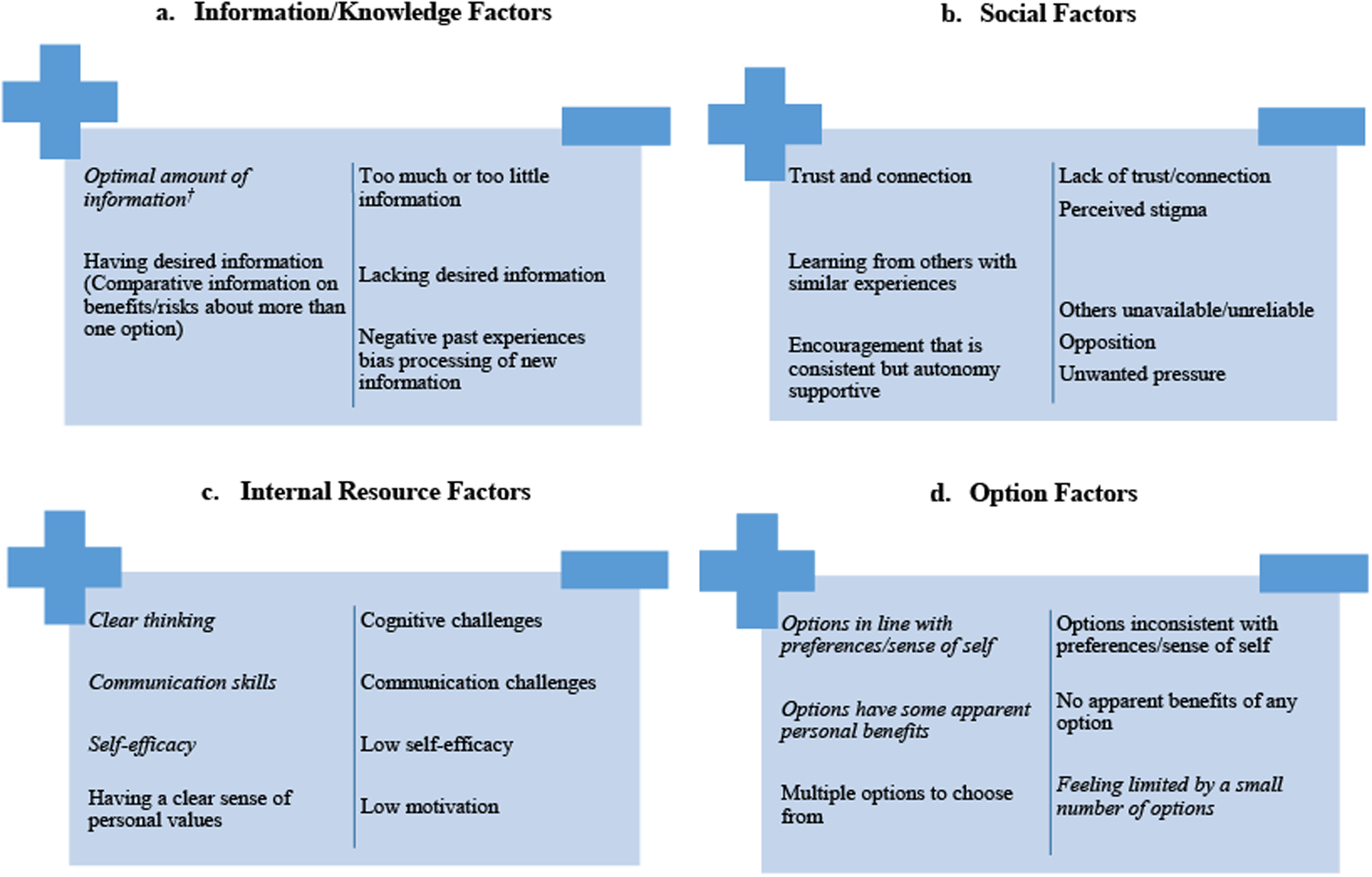

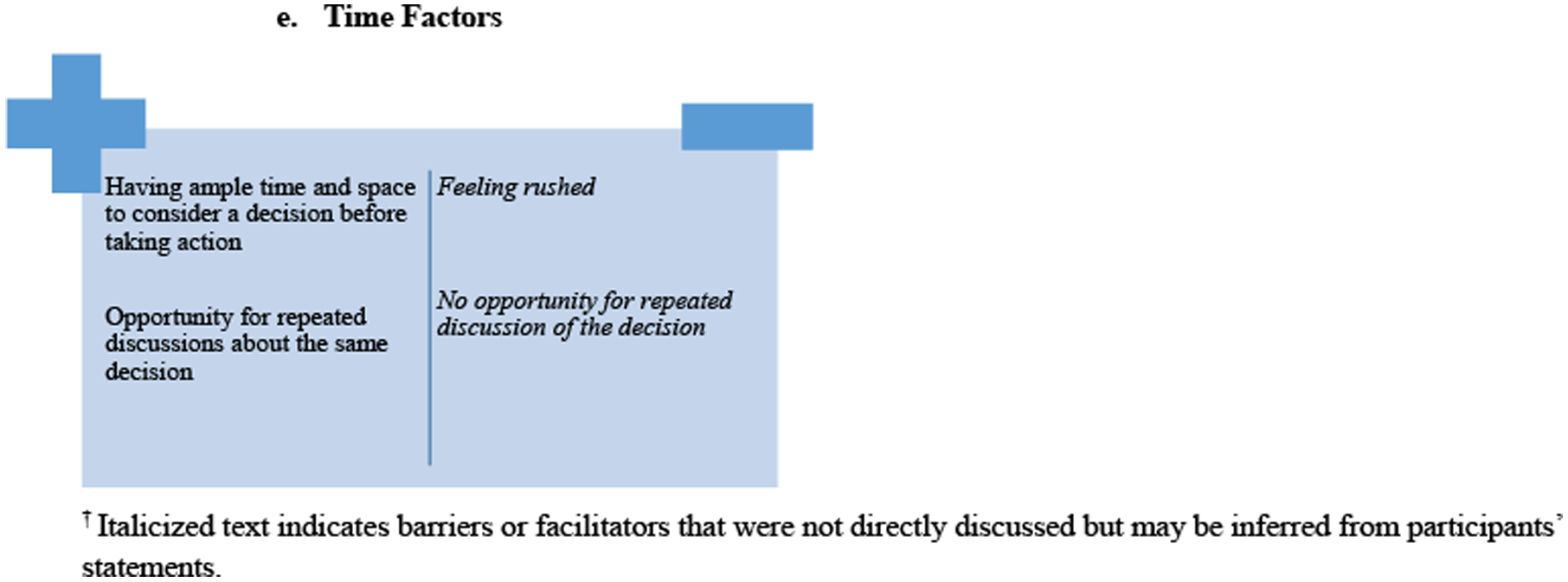

This study also elucidates how the ODSF applies to emerging adults with early psychosis (Figure 2). For example, most participants indicated that they would have liked more and better information, especially to compare options, in keeping with the broader literature (Grim et al., 2016; Lal et al., 2018; Munson et al., 2012; O’Neal et al., 2008).

Figure 2.

Barriers and Facilitators to Treatment Decision-Making among Emerging Adults with Early Psychosis

a. Information/Knowledge Factors

b. Social Factors

c. Internal Resource Factors

d. Option Factors

e. Time Factors

† Italicized text indicates barriers or facilitators that were not directly discussed but may be inferred from participants’ statements.

Participants expounded on social factors hindering or facilitating their decision-making. Consistent with other reports (Simmons et al., 2011), the lack of comfortable, trusted, reliable social support was a troubling hindrance. Understanding this issue requires consideration of common challenges that people with psychosis experience, including stigma (Jansen, Pedersen, Hastrup, Haahr, & Simonsen, 2018), psychosis symptoms that impede trust (Hajdúk, Klein, Harvey, Penn, & Pinkham, 2019), and social anxiety (Michail & Birchwood, 2013). Further, given the myriad of social stressors and familial heritability of mental illnesses (Rasic, Hajek, Alda, & Uher, 2013), young people experiencing early psychosis may have family members with their own mental health challenges that limit their capacity to provide decision support. This makes careful attention to the working alliance (da Costa, Martin, & Franck, 2020) even more important in supporting EIP clients’ decision-making.

The complexity of decision-making “pressure” is also important. Several interviewees reported harmful decision-making pressure from others. Yet, contrary to the ODSF, pressure was also sometimes described as helpful for decision-making. The nuances of “good” vs. “bad” pressure merit further understanding.

Learning from others (i.e., family members, peers, media characters) was a reported facilitator of decision-making. As suggested by Jorm (2000), these sources influence mental health literacy and attitudes about treatment, reflected in participants’ statements. Most indicated they benefitted from knowing others had faced similar decisions, and from learning about the process and outcomes of these.

Interviewees’ report of internal resource factors as central to their decision-making is consistent with other studies (Delman et al., 2015; Stacey et al., 2008), and points to a need for additional supports for some. For example, emerging adults with cognitive challenges may benefit from educational strategies (e.g., multiple learning trials) and simplified language regarding information about options (Dunn & Jeste, 2001).

This study also identifies two decision needs not explicitly articulated in the ODSF: feeling that options are consistent with one’s self-concept and having ample time to consider options before deciding. These factors have been reported elsewhere (Deegan, 2020; Fisher et al., 2018; Munson et al., 2012). While both may be partly outside the control of an EIP program, providers can strive to offer full information about treatment choices and be open to repeated discussions as needed.

These findings demonstrate that emerging adults in EIP may benefit from interventions designed to reduce decisional conflict. Consistent with the ODSF, decision support interventions such as decision coaching, guidance, and decision aids (Stacey et al., 2013), help people make informed, values-aligned decisions by modifying decision-making needs. These interventions reduce decisional conflict and promote mental health service engagement (Bonfils et al., 2016; Mott, Stanley, Street, Grady, & Teng, 2014; Simmons et al., 2017). Additionally, they facilitate shared decision making (Charles, Gafni, & Whelan, 1997), which emerging adults consider an engagement-facilitator (Lucksted et al., 2015). However, a recent systematic review showed they are lacking for emerging adults with serious mental illnesses (Thomas et al., in press). Our findings especially call for the development of youth-friendly decision aids providing evidence-based information about treatment options to help young people choose deliberately between them (Joseph-Williams et al., 2014), and decision coaching interventions to address social obstacles to decision-making.

While subgroup analyses must be interpreted with caution due to sample size, it appeared that participants experienced decision-making barriers and facilitators comparably regardless of level of engagement. This suggests that the recommended decision support strategies are likely to be useful even to low engagers.

The relatively homogeneous participant demographic makeup limits this study, and replication in other early intervention and youth mental health samples is needed. Additionally, emerging adults with barriers to autonomous decision-making (e.g., guardianship, severe cognitive impairment), and those who chose not to enroll in EIP or prematurely discontinued treatment were not included; future research should examine their decision-making needs. Finally, interview probe questions may have artificially inflated the frequencies of reported decision points, barriers, and facilitators.

This study’s importance is reflected in its provision of actionable insights which may help emerging adults make informed, values-consistent decisions about EIP, support shared decision making practices, and increase service engagement.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health under grant number K08MH116101. However, the contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, and endorsement by the Federal government should not be assumed. We express our gratitude to Bodi Bodenhamer, Dennis Laughery, Grayson Bowen, Stephen Dawe, and other members of the Co-Researcher advisory group for their vital contributions to qualitative interview guide development and results interpretation.

Appendix

Decision-Making Needs Qualitative Interview

Now, I am going to ask you some questions about your experiences since you joined [name of EIP program]. Remember that the purpose of this study is to better understand the needs of young people as they make decisions about participating in programs like [name of EIP program]. By “programs like [name of EIP program],” I am referring to those that offer a variety of mental health services and supports, such as medication, therapy, peer support, and help with work or school, to individuals who are experiencing early psychosis. As a [name of EIP program] participant, your opinion will be very helpful for this research. As we discussed previously, we would like to record our interview so that we can be sure to accurately capture what you have to say – we are interested in your views and what is important to you. There are no right or wrong answers.

Only the small team that is working on this study and the professional transcriptionist will be able to hear the interview recording. Your identity and what you say here will NOT be revealed in any way that identifies you. The summaries, reports, or articles we create from the interviews will not include any identifying information. Only de-identified information will be provided to anyone outside the study. So, [name of EIP program] staff and others will not be able to link what you say here back to you. Do you have any questions before we begin? Is it alright with you if we start audio recording our conversation now?

[Interviewer turns on recorders after this point]

DECISION-MAKING CONTEXT

-

1

I would first like to ask you to tell me a little bit about what it has been like to be a part of [name of EIP program]. Tell me whatever you think is important about your experience.

-

2

What specific parts of [name of EIP program] do you use, such as peer support, medication, employment training, or therapy? What do you think about those services? What improvements could be made to these services in order to encourage more people to use them?

-

3

What has it been like to work with [name of EIP program] staff? What do they do that is helpful/not helpful?

DECISION POINTS

When people are involved in a program like [name of EIP program], they often have to make different decisions about whether and how they are going to be a part of the program.

-

4

You have told me that you use [services mentioned in response to Q2]. Thinking back over the first 6 months of your participation in [name of EIP program], what are some decisions that you needed to make about [1st service]? What decisions did you and [therapist/psychiatrist/etc] need to make together while you were participating in [1st service]? [repeat questions for 2nd service, 3rd service, etc]

-

5

Once you started at [name of EIP program], did you need to decide how involved you wanted to be, or whether you wanted to continue in the program? If so, please tell me more about that decision.

Possible probes (if not addressed): Did you face decisions related to:

Choosing between various services within the EIP program

Medications

Treatment goals, such as those related to work/school

Family involvement in the program

-

6

Let’s focus on one particular decision. Of the decisions you mentioned, which one was the most difficult or complicated to make?

-

7

Explain to me why you selected this as your most difficult or complicated decision. What made it more difficult or complicated than the others you mentioned?

-

8

Walk me through the process, step by step, of how you got to that decision. When did you first start to think about this decision? What happened next?

-

9

What ended up happening related to the decision?

DECISIONAL CONFLICT

-

10

Let’s talk about the difficulty with making this decision. What kinds of feelings or thoughts did you have during this whole process?

Possible Probes (if not addressed): During this process, were you:

Unsure about what to do

Worried what could go wrong

Distressed or upset

Constantly thinking about the decision

Changing your mind a lot

Feeling like putting off the decision

Unsure about what was important to you

Physically stressed (tense muscles, racing heartbeat, difficulty sleeping)

If the participant identifies with any of these probes, ask: What do you think might have caused you to feel this way?

If the participant does not identify with a probe, ask: Some people say this is a problem for them. Can you tell me more about why this didn’t apply in your situation or why this was not a problem for you?

FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO DECISIONAL CONFLICT

-

11

What made [DECISION] difficult? How did this make decision-making difficult?

Possible Probes (if not addressed): Were you:

Lacking information about options and/or the pros and cons of each option

Lacking information on the chances of experiencing good or bad results

Confused from information overload

Feeling unsupported in making a decision

Feeling pressure from others to make a decision

Lacking motivation or not feeling ready to make a decision

Lacking the ability or skill to make a decision

Feeling like prejudice or discrimination against you negatively impacted decision-making in some way

If the participant identifies with any of these probes, ask: How did [probe] make decision-making difficult?

If the participant does not identify with a probe, ask: Some people say this is a problem for them. Can you tell me more about why this didn’t apply in your situation or why this was not a problem for you?

DECISION SUPPORT

Now I want to switch gears and talk about what may have helped with making this decision.

-

12

What, if anything, helped with making this decision? How was this helpful?

Possible Probes:

Did talking to EIP staff help?

Did talking to people who have faced the same decision help?

- Did receiving information help?

- If so, what kind of information was helpful?

- Information about options

- Information about the pros of various options

- Information about the cons of various options

- Information about the chances of experiencing good or bad results

- Information helping you consider what is important to you

- Information about how to problem solve and talk to others about the decision

- Other information (specify)

- If so, how did you receive the information:

- Booklet, brochure

- Internet

- Videos/DVDs

- Other (specify)

Is there anything else that supported you in making this decision?

If the participant identifies with any of these probes, ask: How did [probe] help with decision-making?

If the participant does not identify with a probe, ask: Some people say this is helpful for them. Can you tell me more about why this didn’t apply in your situation or why this was not helpful for you?

ONLY ASK 13–15 IF THESE QUESTIONS WERE NOT ADDRESSED DURING QUESTION 12.

-

13What role did [name of EIP program] staff have in your decision?

- If they had a role, ask: how did they support you in making this decision?

- If they did not have a role, ask: what do you wish they would have done?

-

14What role did other people, like your family, friends, or significant other, have in your decision?

- If they had a role, ask: how did they support you in making this decision?

- If they did not have a role, ask: what do you wish they would have done?

-

15Did you know anyone else who had to make a decision like yours?

- IF NO: SKIP TO Q17

- IF YES: Did you talk to this person when facing this decision?

- IF NO: Why not?

- IF YES: How did this person support you when you were facing this decision, if at all?

- IF YES: What influence, if any, did this person have on the decision?

-

16Did you feel like you had enough support from others, like [name of EIP program] staff, family, friends, and/or your significant other, when you were facing this decision? Why or why not?

- If interviewee felt unsupported or under-supported: What could others have done to support you more?

-

17

How did you prefer that the decision be made - on your own, by others, or with others? Is this always how you prefer that decisions be made? If yes, why? If no, why not?

-

18

How was the decision actually made? How did you feel about how the decision was actually made?

-

19

If you had to make another decision like this one, what kind of information or support would you want?

INTERVIEWEE CONTRIBUTIONS TO DECISION-MAKING

-

21.

How do you think you contributed to making this decision?

-

22.

What do you think you taught [name of EIP program] staff, family, friends, or others about decision-making?

WRAP UP

-

23.

Is there anything I didn’t specifically ask about that you think would be helpful for me to know?

-

24.

How do you think your input regarding these questions could benefit other people receiving services?

-

25.

Do you have any questions for me?

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest associated with this research.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Ajzen I (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-t [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett J, Lloyd C, & Bassett H (2001). Work issues for young people with psychosis: Barriers to employment. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 64(2), 66–72. doi: 10.1177/030802260106400203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfils KA, Dreison KC, Luther L, Fukui S, Dempsey AE, Rapp CA, & Salyers MP (2016). Implementing CommonGround in a community mental health center: Lessons in a computerized decision support system. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 41(3), 216–223. doi: 10.1037/prj0000225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley EH, Curry LA, & Devers KJ (2007). Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Services Research, 42(4), 1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne J, Penn DL, Bauer DJ, Meyer-Kalos P, Mueser KT, Robinson DG, … Kane JM (2017). Perceived autonomy dupport in the NIMH RAISE early treatment program. Psychiatric Services, 68(9), 916–922. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cane J, O’Connor D, & Michie S (2012). Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation Science, 7(1), 37. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles C, Gafni A, & Whelan T (1997). Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: What does it mean? (Or it takes at least two to tango). Social Science & Medicine, 44(5), 681–692. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00221-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa H, Martin B, & Franck N (2020). Determinants of therapeutic alliance with people with psychotic disorders: A systematic literature review. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 208(4), 329–339. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deegan PE (2020). The journey to use medication optimally to support recovery. Psychiatric Services, 71(4), 401–402. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delman J, Clark JA, Eisen SV, & Parker VA (2015). Facilitators and barriers to the active participation of clients with serious mental illnesses in medication decision making: the perceptions of young adult clients. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 42(2), 238–253. doi: 10.1007/s11414-014-9431-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle R, Turner N, Fanning F, Brennan D, Renwick L, Lawlor E, & Clarke M (2014). First-episode psychosis and disengagement from treatment: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services, 65(5), 603–611. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LB, & Jeste DV (2001). Enhancing informed consent for research and treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology, 24(6), 595–607. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00218-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher A, Manicavasagar V, Sharpe L, Laidsaar-Powell R, & Juraskova I (2018). A qualitative exploration of patient and family views and experiences of treatment decision-making in bipolar II disorder. Journal of Mental Health, 27(1), 66–79. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2016.1276533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, & Strauss A (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Gondek D, Edbrooke-Childs J, Velikonja T, Chapman L, Saunders F, Hayes D, & Wolpert M (2017). Facilitators and barriers to person-centred care in child and young people mental health services: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(4), 870–886. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon C, Gidugu V, Rogers ES, DeRonck J, & Ziedonis D (2016). Adapting open dialogue for early-onset psychosis into the US health care environment: A feasibility study. Psychiatric Services, 67(11), 1166–1168. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grim K, Rosenberg D, Svedberg P, & Schon UK (2016). Shared decision-making in mental health care-A user perspective on decisional needs in community-based services. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 11, 30563. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v11.30563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajdúk M, Klein HS, Harvey PD, Penn DL, & Pinkham AE (2019). Paranoia and interpersonal functioning across the continuum from healthy to pathological—Network analysis. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(1), 19–34. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes D, Edbrooke-Childs J, Town R, Wolpert M, & Midgley N (2020). Barriers and facilitators to shared decision-making in child and youth mental health: Exploring young person and parent perspectives using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Counselling & Psychotherapy Research, 20(1), 57–67. doi: 10.1002/capr.12257 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Kahn RL, McLeod JD, & Williams D (1985). Measures and concepts of social support. In Cohen S & Syme SL (Eds.), Social support and health. (pp. 83–108). San Diego, CA, US: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Dodge T, & Dittus P (2002). Parent-adolescent communication about sex and birth control: a conceptual framework. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev(97), 9–41. doi: 10.1002/cd.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen M, O’Connor A, & Stacey D (2013). Decisional needs assessment in populations: A workbook for assessing patients’ and practitioners’ decision-making needs. University of Ottawa. [Google Scholar]

- Janis IL, & Mann L (1977). Decision making : a psychological analysis of conflict, choice, and commitment. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen JE, Pedersen MB, Hastrup LH, Haahr UH, & Simonsen E (2018). Important first encounter: Service user experience of pathways to care and early detection in first-episode psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 12(2), 169–176. doi: 10.1111/eip.12294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF (2000). Mental health literacy. Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry, 177, 396–401. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.5.396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph-Williams N, Newcombe R, Politi M, Durand MA, Sivell S, Stacey D, … Elwyn G (2014). Toward minimum standards for certifying patient decision aids: A modified Delphi consensus process. Medical Decision Making, 34(6), 699–710. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RL (1994). Social support: Content, causes and consequences. New York: Springer Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Lal S, Nguyen V, & Theriault J (2018). Seeking mental health information and support online: experiences and perspectives of young people receiving treatment for first-episode psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 12(3), 324–330. doi: 10.1111/eip.12317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas MS, Skokowski CT, & Ancis JR (2000). Contextual themes in career decision making of female clients who indicate depression. Journal of Counseling and Development, 78(3), 316–325. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2000.tb01913.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucksted A, Essock SM, Stevenson J, Mendon SJ, Nossel IR, Goldman HH, … Dixon LB (2015). Client views of engagement in the RAISE Connection Program for early psychosis recovery. Psychiatric Services, 66(7), 699–704. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, & Guassora AD (2015). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascayano F, van der Ven E, Martinez-Ales G, Basaraba C, Jones N, Lee R,…Dixon LB (2020). Predictors of early discharge from early intervention services for psychosis in New York state. Psychiatric Services, 71(11),1151–1157. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascayano F, van der Ven E, Martinez-Ales G, Henao AR, Zambrano J, Jones N,…Dixon LB (2021). Disengagement from early intervention services for psychosis: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services, 72(1), 49–60. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam SB (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Michail M, & Birchwood M (2013). Social anxiety disorder and shame cognitions in psychosis. Psychological Medicine, 43(1), 133–142. doi: 10.1017/s0033291712001146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikesell L, Bromley E, Young AS, Vona P, & Zima B (2016). Integrating client and clinician perspectives on psychotropic medication decisions: Developing a communication-centered epistemic model of shared decision making for mental health contexts. Health Communication, 31(6), 707–717. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2014.993296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott JM, Stanley MA, Street RL Jr., Grady RH, & Teng EJ (2014). Increasing engagement in evidence-based PTSD treatment through shared decision-making: A pilot study. Military Medicine, 179(2), 143–149. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson MR, Jaccard J, Smalling SE, Kim H, Werner JJ, & Scott LD (2012). Static, dynamic, integrated, and contextualized: A framework for understanding mental health service utilization among young adults. Social Science & Medicine, 75(8), 1441–1449. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor AM, Tugwell P, Wells GA, Elmslie T, Jolly E, Hollingworth G, … Drake E (1998). A decision aid for women considering hormone therapy after menopause: decision support framework and evaluation. Patient Education and Counseling, 33(3), 267–279. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00026-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neal EL, Adams JR, McHugo GJ, Van Citters AD, Drake RE, & Bartels SJ (2008). Preferences of older and younger adults with serious mental illness for involvement in decision-making in medical and psychiatric settings. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(10), 826–833. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318181f992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahwa R, Fulginiti A, Brekke JS, & Rice E (2017). Mental illness disclosure decision making. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87(5), 575–584. doi: 10.1037/ort0000250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, & Hoagwood K (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), 533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez MMB, Menear M, Brehaut JC, & Legare F (2016). Extent and predictors of decision regret about health care decisions: A systematic review. Medical Decision Making, 36(6), 777–790. doi: 10.1177/027298910.1177/0272989x16636113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido BA (1992). Beyond rational choice: The social dynamics of how people seek help. American Journal of Sociology, 97(4), 1096–1138. doi: 10.1086/229863 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK (2012). Qualitative and mixed methods in public health. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc. Retrieved from https://methods.sagepub.com/book/qualitative-and-mixed-methods-in-public-health. doi: 10.4135/9781483384511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rasic D, Hajek T, Alda M, & Uher R (2013). Risk of mental illness in offspring of parents with schizophrenia, bipolar Disorder, and major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of family high-risk studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 40(1), 28–38. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds S, Brown E, Kim DJ, Geros H, Sizer H, Eaton S, … O’Donoghue B (2019). The association between community and service level factors and rates of disengagement in individuals with first episode psychosis. Schizophrenia research, 210, 122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.05.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DG, Schooler NR, Correll CU, John M, Kurian BT, Marcy P, … Kane JM (2018). Psychopharmacological treatment in the RAISE-ETP study: Outcomes of a manual and computer decision support system based intervention. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(2), 169–179. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16080919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzer MS, & Kottsieper P (2015). Peer support and service engagement. In Corrigan PW (Ed.), Person-centered care for mental illness: The evolution of adherence and self-determination. (pp. 191–209). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons MB, Batchelor S, Dimopoulos-Bick T, & Howe D (2017). The choice project: peer workers promoting shared decision making at a youth mental health service. Psychiatric Services, 68(8), 764–770. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons MB, Hetrick SE, & Jorm AF (2011). Experiences of treatment decision making for young people diagnosed with depressive disorders: a qualitative study in primary care and specialist mental health settings. BMC Psychiatry, 11, 13. doi: 10.1186/1471-244x-11-194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey D, Kryworuchko J, Belkora J, Davison BJ, Durand MA, Eden KB, … Street RL (2013). Coaching and guidance with patient decision aids: A review of theoretical and empirical evidence. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 13, 11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-s2-s11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey D, Menard P, Gaboury I, Jacobsen M, Sharif F, Ritchie L, & Bunn H (2008). Decision-making needs of patients with depression: a descriptive study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 15(4), 287–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01224.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stovell D, Wearden A, Morrison AP, & Hutton P (2016). Service users’ experiences of the treatment decision-making process in psychosis: A phenomenological analysis. Psychosis-Psychological Social and Integrative Approaches, 8(4), 311–323. doi: 10.1080/17522439.2016.1145730 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tait L, Birchwood M, & Trower P (2002). A new scale (SES) to measure engagement with community mental health services. Journal of Mental Health, 11(2), 191–198. doi: 10.1080/09638230020023570-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas EC, Ben-David S, Treichler E, Roth S, Dixon L, Salzer M, & Zisman-Ilani Y (in press). A systematic review of shared decision making interventions for service users with serious mental illnesses: State of science and future directions. Psychiatric Services. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner M, Smith-Hamel C, & Mulder R (2007). Prediction of twelve-month service disengagement from an early intervention in psychosis service. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 1(3), 276–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2007.00039.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White DA, Luther L, Bonfils KA, & Salyers MP (2015). Essential components of early intervention programs for psychosis: Available intervention services in the United States. Schizophrenia Research, 168(1), 79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.