Abstract

Objectives:

Previous studies indicate that patient satisfaction with mental healthcare is correlated with both treatment outcomes and quality of life. This study aimed to 1) describe online reviews of mental health treatment facilities, including key themes in review content, and 2) evaluate the correlation between narrative review themes, facility characteristics, and review ratings.

Methods:

United States National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS) facilities were linked to their corresponding Yelp pages, created between March, 2007 and September, 2019. Correlations between review ratings and both machine-learning generated latent Dirichlet allocation topics and N-MHSS reported facility characteristics were measured using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, and significance was defined by a Bonferroni adjusted p<.001.

Results:

Of 10,191 unique mental health treatment facilities, 1,383 (13.6%) had relevant Yelp pages with 8,133 corresponding reviews. The number of newly reviewed facilities and the number of new reviews increased throughout the study period. Narrative topics positively correlated with review ratings included caring staff (Spearman’s rho=.39) and non-pharmacologic treatment (rho=.16). Topics negatively correlated with review ratings included rude staff (rho=−.14) and safety and abuse (rho=−.13). Of 126 N-MHSS survey items, 11 were positively correlated with review rating, including “outpatient mental health facility” (rho=.13), and 33 were negatively correlated with review rating, including accepting Medicare (rho=−.21).

Conclusions:

Narrative topics provide information beyond what is currently collected through the N-MHSS. Topics associated with positive and negative reviews, such as staff attitude towards patients, can guide improvement in patients’ satisfaction and engagement with mental healthcare.

In the United States (US), approximately 1 in 5 people will experience a mental illness each year, and less than 50% will receive treatment.(1) While most evidence points to increasing provision of treatment over time, studies also show an increasing mental health burden both nationally and internationally.(2–4) Factors contributing to the treatment gap include underfunding - in 2015, the mental health burden in the US was 2.7 times greater than the proportion of health funds allocated to mental health(3) - but also patients’ engagement in their own care. Patient engagement impacts treatment retention and therapeutic outcomes.(5) While engagement depends on patients’ perceptions of the quality of care they receive, few studies have analyzed factors associated with positive or negative experiences of mental health treatment.(6, 7) Patient satisfaction is associated with fewer psychiatric symptoms and better quality of life.(8)

The implementation of mental healthcare quality measures lags behind that of other fields of medical care.(9) The majority of the quality measures that have been endorsed by the US National Quality Forum and used in major quality reporting programs, such as the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Hospital Compare, are related to screening and assessment rather than patient-centered outcomes.(10) According to the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, end-users of research, including patients, should be involved in defining outcomes that are “meaningful and important to patients and caregivers.”(11) Psychiatric hospitals included in Hospital Compare and evaluated through the Inpatient Psychiatric Facility Quality Reporting Program do not report star ratings, and patients who “received psychiatric or rehabilitative services” are excluded from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) because the “instrument is not designed to address…the behavioral health issues pertinent to psychiatric patients”.(12, 13) The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) collects data on mental health treatment facilities through the National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS), but the survey does not include quality or patient satisfaction measures.(14)

Online review sites, such as Yelp, Google, and Facebook, provide platforms for word-of-mouth communication about healthcare, including mental health services.(15–23) Risks with using online review data include fraudulent reviews and over-representation of extreme opinions. Reviews do, however, offer advantages: they allow for narrative reporting, are public, and are available to both patients and their support networks.(15, 24) Studies have demonstrated that review ratings and narrative themes tend to correlate with both existing national surveys, such as HCAHPS and the National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services, and in some cases, with health outcomes.(16, 21, 25) Review themes also provide insight into drivers of satisfaction, as measured by review ratings, that are not captured by standard surveys.(16, 18, 19, 21, 22, 25)

In order to identify factors associated with patients’ or their families’ positive or negative experiences with mental healthcare, we analyzed Yelp reviews of mental health facilities registered in SAMHSA’s Treatment Locator. As of March 31, 2020, Yelp had 35 million average monthly mobile app users and 211 million reviews.(26) Given Yelp’s extensive usership and the lack of standardized patient quality and satisfaction measures in US mental healthcare, patients may turn to the site when selecting or evaluating a mental health facility. Understanding the factors that influence user reviews of facilities could inform areas of focus for reducing unmet mental health needs in the US. The purpose of this analysis was threefold: to understand the extent to which Yelp is used to review mental health treatment facilities, to describe narrative themes in Yelp reviews of mental health treatment, and to identify narrative themes and facility services correlated with review ratings.

Methods

This study was considered exempt by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board. The Yelp data used in the study represents an academic dataset generated directly by Yelp for research and includes all US facilities tagged as “health” facilities according to Yelp’s developer documentation.(27) It is updated daily, and extends beyond content available through the Yelp application programming interface. SAMHSA facility data and N-MHSS data are freely available for download from the SAMHSA website.

Study sample

To evaluate online reviews for a validated group of facilities, we sought to match SAMHSA mental health facilities to their corresponding Yelp pages. This matching afforded the added advantage of allowing for comparison between Yelp review ratings and the N-MHSS data associated with each SAMHSA facility.

We downloaded all SAMHSA data and Yelp data in September, 2019. Facilities were added to Yelp between March, 2007 and September, 2019. Facility data included name; location; and reviews, including both review star rating (one to five) and narrative review content.

From SAMHSA’s Treatment Locator, we identified 10,191 unique “mental health” facilities, last updated between February, 2017 and September, 2019. Facilities are eligible for registration in the Treatment Locator if they are funded by a state mental health agency, administered by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, or licensed by a state agency or national organization to provide mental health treatment. Eligible facilities are identified through surveys of state mental health authorities and medical organizations. All included facilities complete the N-MHSS, and according to the 2018 N-MHSS, the “survey universe” of mental health treatment facilities was 14,159. (14)

Each SAMHSA facility was matched to a corresponding Yelp page according to a probabilistic string-matching algorithm with a sensitivity of 88.9% and a specificity of 95.1%.(28, 29) The list of SAMHSA mental health facilities successfully matched to Yelp pages included medical centers with psychiatric units. In the majority of such cases, the corresponding Yelp page was for the parent organization, and most of the reviews pertained to general medical care rather than mental healthcare. We used a term search strategy to remove facilities with reviews using high proportions of words more likely to refer to general medical care.20 This step was validated through a combination of hand-coding and topic modeling. Further details are available online.

Review analysis

To understand Yelp usage over time, we calculated the number of new reviews and the number of facilities receiving a first review by yearly quarter. To evaluate review content, we used a machine learning based natural language processing model, Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA). LDA operates under the assumption that documents, in this case Yelp reviews, can be described by a pre-specified number of topics. Topics are defined by distributions of commonly co-occurring words, and each review is then defined by a distribution of topics. A topic most strongly defined by the words “staff”, “helpful”, and “friendly” might then be highly representative of a review such as, “Great place!! Front desk staff were very helpful.” Authors DCS and HM independently reviewed the ten words and reviews most strongly associated with each of the 30 LDA topics and, where review content was consistent, assigned the topics a theme. Discrepancies were adjudicated by a third reviewer (RMM). This process resulted in identification of 13 consistent topics. This approach, and the ratio of meaningful topics to all LDA topics, was consistent with prior Yelp studies. (16, 19, 21)

Survey analysis

Patient ratings of mental health treatment facilities may be correlated with existing objective facility metrics, as has proven true in hospitals, substance use treatment facilities, and nursing homes.(16, 21, 25) In mental healthcare, for instance, evidence from qualitative analyses suggests patients have concerns specific to pharmacologic and inpatient treatment.(30, 31) The N-MHSS is an annual survey conducted by SAMHSA and is the only national survey of both public and private mental health treatment facilities.(14) The survey includes 18 service categories divided into 126 binary service codes, and it covers such information as facility type, special programming, and availability of emergency mental health services. In order to identify how narrative analysis of review content may support or augment data currently collected by SAMHSA, we sought to measure the correlation between N-MHSS survey items and Yelp review ratings.

Statistical analysis

To compare star ratings with both N-MHSS services and LDA topics, we used Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, which is suited to comparisons of nonparametric data. Star ratings are ordinal, ranging from 1 to 5, while LDA probability distributions are generally non-normally distributed continuous variables between 0 and 1. N-MHSS services are binary variables. Both the correlations between N-MHSS services and star ratings and between star ratings and LDA probabilities were performed at the level of the Yelp review. Significance was defined by a Bonferroni-corrected p<.001, corresponding to a corrected alpha of .0000072.(32) All statistical analyses were performed using R, version 3.6.1.(33)

Results

Study sample

Of the 10,191 unique SAMHSA facilities, 2,403 (23.6%) were matched to Yelp “health” facilities. Of these matches, 1,383 (13.6%) remained following filtering by general medical terms (flow diagram available online). As summarized in Table 1, the final sample differed meaningfully from SAMHSA mental health facilities without dedicated Yelp pages by geographic distribution, with over-representation of facilities located in the West, and on several survey items: among service settings, “hospital inpatient” and “partial hospitalization/day treatment” were over-represented, as was special programming for specific groups, such as “young adults” and “veterans”.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of SAMHSA mental health facilities on Yelp compared to all SAMHSA mental health facilitiesa

| Characteristic | SAMHSA mental health facilities (N=10,191) |

p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Yelp reviews (N=1,383) | Without Yelp reviews (N=8,808) | ||||

|

| |||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Region | <.001 | ||||

| Northeast | 254 | 18.4 | 1941 | 22.2 | |

| South | 358 | 25.9 | 2682 | 30.7 | |

| Midwest | 303 | 21.9 | 2303 | 26.4 | |

| West | 468 | 33.8 | 1806 | 20.7 | |

| Service settingsb | |||||

| Hospital inpatient | 396 | 28.6 | 1233 | 14.0 | <.001 |

| Outpatient | 1113 | 80.5 | 7012 | 79.6 | .478 |

| Partial hospitalization/day treatment | 369 | 26.7 | 7544 | 14.4 | <.001 |

| Residential | 218 | 15.8 | 1237 | 14.0 | .097 |

| Telemedicine/telehealth | 513 | 37.1 | 3358 | 38.1 | .481 |

| Offers special programming for people pertaining to the following groupsb | |||||

| Young adults | 356 | 25.7 | 1907 | 21.7 | <.001 |

| Seniors | 460 | 33.3 | 2300 | 26.1 | <.001 |

| Veterans | 291 | 21.0 | 1436 | 16.3 | <.001 |

| LGBT | 426 | 30.8 | 1838 | 20.9 | <.001 |

| Co-occurring mental and substance use disorders | 827 | 59.8 | 4430 | 50.3 | <.001 |

| Living with HIV/AIDS | 204 | 14.8 | 920 | 10.4 | <.001 |

| Experienced trauma | 681 | 49.2 | 3844 | 43.6 | <.001 |

| Children/adolescents with serious emotional disturbances | 492 | 35.6 | 3268 | 37.1 | .287 |

| Living with serious mental illness | 721 | 52.1 | 4327 | 49.1 | .040 |

| Offers emergency mental health servicesb | |||||

| Crisis intervention team | 643 | 46.5 | 4481 | 50.9 | .003 |

| Psychiatric emergency walk-in services | 512 | 37.0 | 2914 | 33.1 | .004 |

Proportions were compared by chi square tests.

Categories not mutually exclusive, and differences therefore tested individually.

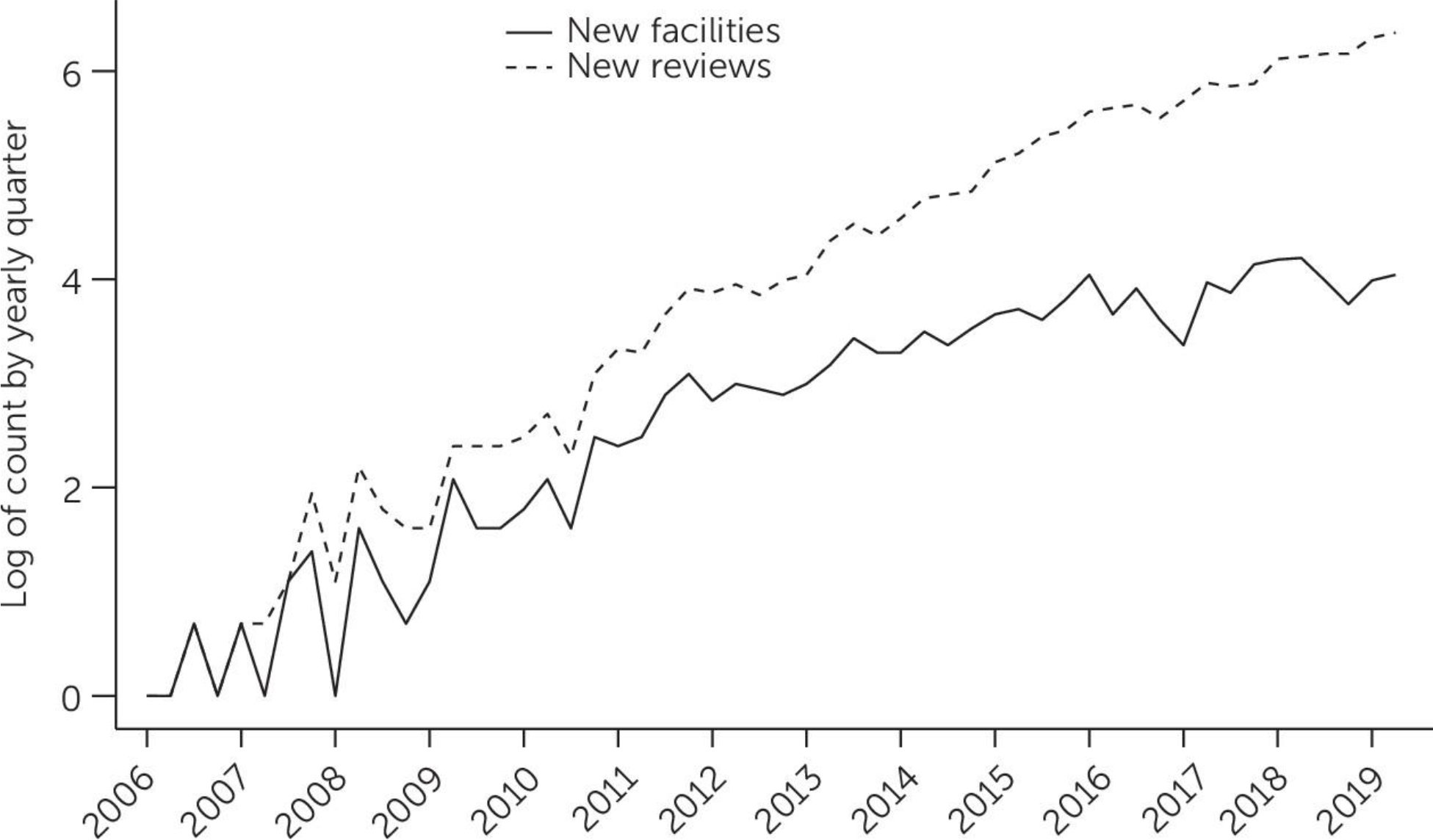

The facilities had a total of 8,133 reviews, corresponding to a mean number of 5.88 reviews per facility (range 1 to 107, median 3). The mean word count per review was 170.2±164.8. The distribution of review ratings was bimodal, with 57.5% one-star (lowest possible) and 26.5% five-star (highest possible) reviews. As shown in Figure 1, both the number of reviews and the number of facilities receiving a first review increased from 2006 to 2019.

Figure 1.

Number of new mental health facility reviews and mental health facilities receiving a first review on Yelp by quarter between January, 2006 and June, 2019

Review analysis

Of the 13 LDA topics, four were positively correlated with review ratings, seven were negatively correlated with review ratings, and two were not significantly correlated with review ratings, according to a Bonferroni corrected p<.001. The topics, redacted sample reviews, and correlations with review ratings are presented in Table 2. The strength of correlations was generally greater for positive topics, e.g. “helpful and friendly staff” (Spearman’s rho = .39), than for negative topics, e.g. “rude ancillary staff” (rho = −.14).

Table 2.

Yelp review topics with sample redacted reviews and Spearman’s rank correlation to review rating

| Online review theme | Example reviewa | Spearman’s rho |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Topics positively correlated with review rating | ||

| Caring staff | …everyone here are so nice and so helpful…from the front staff all the way to the doctors!…Im very happy with the service I have received and continue to receive. Thank you everyone…. | .39 |

| Life-saving treatment | If you are ready to get better and you work the program you will succeed! Staff is caring and compassionate…They will fight for you which at times you will hate but in the end, it will save your life. | .28 |

| Non-pharmacologic treatment modalities | I did outpatient individual therapy, dietitian support…and…group therapy all in one building…Every…provider I worked with really genuinely cared for me. | .16 |

| Therapeutic alliance with primary provider | Dr M is the best. He listens and he shows concern as well as empathy…I would highly recommend Dr M. | .11 |

| Topics negatively correlated with review rating | ||

| Rude ancillary staff | For how amazing and incredible the residential staff is, the front desk staff is arrogant, rude, and comes across as not caring. Front desk is the first impression… its a shame its being ruined by your front desk staff | −.14 |

| Safety and abuse | I left with more psychological problems than when I arrived. The staff are not trained…I laughed when they tried to stop bullying since the staff were the ones bullying children with name calling and brutal physical assaults… | −.14 |

| Billing and insurance | I was lied to about insurance coverage…told multiple times that my insurance would cover it all and then got billed…they'll only take your insurance if you work for certain companies. | −.11 |

| Scheduling | My family member has called almost every week to schedule an appointment now that she did her intake, and each time she calls they tell her that she has not been assigned a counselor and they transfer her to…voicemail. None of her messages have been returned… It shouldnt take 3 months to get an appointment…every time we ask to speak to the director, we are told that they are not in. | −.09 |

| Treatment for specific diagnosis | …Brought a person here who needed help with drug dependency and depression…patient was treated as if they were a criminal being booked into a jail. Still in search of dignified and compassionate care! | −.08 |

| Communication with family | No communication with the families. No support for the families. When we picked up our loved one we were given ZERO information. No info about options of what the next steps should be once the patient leaves. | −.08 |

| Pharmacotherapy | My counselor was great…but the Doctor got me hooked on antidepressants and after 4 years tried to discharge me after I missed some counseling appts. I ended up…thanking my counselor and told her that I would not be back and that I would ween myself off the meds. | −.06 |

| Topics non-significantly correlated with review rating b | ||

| Child and adolescent treatment | I was 14 years old when I was at this place. I hated the way the staff would treat us kids, they are there to help us not destroy our happiness…Continuously put residents down as if they were trash. Im almost 30 now and I'm still scarred and scared of that place. | .01 |

| Inpatient facility amenities | Their food is horrible…Beds are trash. Worst "hospital" ever. Extremely limited food, outside activity, phone calls, visitation, recreational exercise. The nurses go in your room every 5 seconds slamming doors open and shut in your shared room. | −.05 |

Elements of the reviews have been redacted in order to preserve user anonymity

Correlation considered significant where p below Bonferroni corrected alpha of .001 (p<.(001/139)=7.2×10−6)

Reviews most represented by the generally positive topic “nonpharmacologic treatment modalities” (rho=.16) included mentions of “individual therapy”, “Yoga”, “dietitian support”, “group therapy”, “dialectical behavior skills”, “family workshops”, and “trauma program[s]”. Those for the generally negative topic “safety and abuse” (rho=−.14) mentioned specific concerns about “name calling” and being “violated…verbally”, “physical assault” by both patients and staff, “sexual assault”, “theft”, and “neglect”. Of the seven topics negatively correlated with review rating, two were related to clerical services: “billing and insurance” (rho=−.11) and “scheduling” (rho=−.09).

Survey analysis

Facilities offered on average 40±11 of the 126 N-MHSS services. In total, 11 services were significantly correlated with five-star reviews, and 33 were significantly correlated with one-star reviews. Table 3 shows the 10 services with strongest positive and negative correlations to Yelp review ratings. Among facility types, “outpatient mental health facility”(rho=.13) and “residential treatment center for adults” (rho=.07) were positively correlated with review rating, while “psychiatric hospital” (rho=−.19) was negatively correlated with review rating.

Table 3.

SAMHSA services most positively and negatively correlated with Yelp review ratings, according to Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient

| Services | Spearman’s rho |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Services most positively correlated with review rating | |

| Facility Type | |

| Outpatient mental health facility | .13 |

| Residential treatment center (RTC) for adults | .07 |

| Facility Operation (e.g. Prviate, Public) | |

| Veterans Affairs Medical Center | .05 |

| Exclusive Services | |

| Serves Veterans only | .05 |

| Service Settings | |

| Outpatient | .06 |

| Special Programs/Groups Offered | |

| Lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) clients | .10 |

| Persons with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | .06 |

| Ancillary Services | |

| Housing services | .07 |

| Intensive case management | .06 |

| Psychosocial rehabilitation services | .05 |

| Services most negatively correlated with review rating | |

| Payment/Insurance/Funding Accepted | |

| Medicare | −.21 |

| Medicaid | −.18 |

| Military insurance | −.16 |

| State welfare or child and family services funds | −.12 |

| Facility Type | |

| Psychiatric hospital or psychiatric unit of a general hospital | −.19 |

| Service Settings | |

| Hospital inpatient | −.18 |

| Emergency Mental Health Services | |

| Psychiatric emergency walk-in services | −.17 |

| Language Services | |

| Services for the deaf and hard of hearing | −.16 |

| Treatment Approaches | |

| Psychotropic medication | −.15 |

| Tobacco/Screening Services | |

| Screening for tobacco use | −.13 |

All p-values below Bonferroni-corrected alpha of. 001 (p<.(001/139)=7.2×10−6)

As with the LDA topic “non-pharmacologic treatment modalities” (rho=.16), N-MHSS codes for special programs and for ancillary services were generally positively correlated with review rating, e.g. programming for “lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender clients” (rho=.10) and “housing services” (rho=.07). On the other hand, as with the LDA topic “billing and insurance”, N-MHSS codes for specific forms of payment and insurance, especially public insurance, were generally negatively correlated with review rating, e.g. “Medicare” (rho=−.21), as were both the LDA topic “pharmacotherapy” (rho=−.06) and the N-MHSS code “psychotropic medication (rho=−.15).

Discussion

This study has three main findings. First, individuals are increasingly reviewing mental health facilities online. The percent of SAMHSA facilities identified on Yelp (14%) was between the percent of hospitals (31%) and skilled nursing facilities (11%) identified on the site in prior studies.(16, 25) The number of Yelp pages and reviews of mental health facilities is expected to continue to increase: in the four months between June and September of 2019, 806 Yelp pages were added under the site’s “counseling and mental health” tag. Of note, facilities in the West and facilities offering inpatient treatment were over-represented on Yelp. Yelp is California-based, which may explain the former, and large facilities may be both more likely to offer inpatient services and more likely to have Yelp pages. The bimodal distribution of online review ratings, with high proportions of one-star and five-star reviews, was consistent with distributions observed for other health facilities.(16, 19) In the absence of formal outlets for patients to report their experiences of mental healthcare, we expect the volume of patients choosing to do so through more informal means, such as online reviews, to continue to grow.

Second, correlations between review ratings, narrative topics, and N-MHSS services were consistent with previous findings in both qualitative analyses of mental healthcare and analyses of online reviews. An analysis of online reviews of substance use treatment facilities in Pennsylvania identified the positive review theme “life-changing experiences” and the negative review theme “medication needs”, consistent with themes we identified as correlated positively (“life-saving treatment”) and negatively (“pharmacotherapy”) with online reviews of mental health facilities.(21) The strength of correlations reported in the substance use treatment paper between themes and review ratings were slightly larger than those reported here, perhaps due to a combination of fewer LDA topics and binary treatment of review ratings. Studies of inpatient psychiatric care point to patient concerns around safety, restrictions on freedom, communication, and stigma. (34, 35) In our analysis, there were more negative comments associated with inpatient services than with outpatient services, and reviews with poor ratings were more likely to mention issues of “safety and abuse”, “communication with family”, and “rude ancillary staff”. Themes associated with more positive ratings, like “relationship with primary provider” and “caring staff”, also correspond to existing evidence: a study of 61 inpatients found that “feeling cared for” and “positive qualities of staff” were themes common to positive patient appraisals of care.(34) In general, evidence suggests that patient “satisfaction” is perhaps most dependent on staff-patient communication.(36) Communication with staff has been consistently identified as a theme in online reviews of healthcare, including in reviews for emergency departments, hospitals, and substance use treatment facilities.(16, 18, 21) Among mental healthcare facility reviews, we found that topics related to communication, namely “caring staff” and “rude ancillary staff”, were those most strongly correlated with positive and negative review ratings, respectively.

The third main finding is that narrative topics identified in reviews include actionable items that may improve satisfaction with mental healthcare. Satisfaction is inherently important - how patients feel about the care they receive should matter to providers - but in mental healthcare in particular, it may also be associated with fewer psychiatric symptoms and better quality of life.(8) Evidence regarding the relationship between satisfaction and physical health outcomes is mixed, but generally supports positive correlations between patient evaluations of communication with both doctors and nurses and more objective measures of quality.(25, 36, 37) Many negative reviews of mental healthcare facilities mentioned “rudeness” explicitly. While “rudeness” is not unique to mental healthcare, it may contribute to patients’ internalized stigma, which is associated with decreased help-seeking and disempowerment among those with mental illness.(38, 39) Mental healthcare facilities could use the information from Yelp reviews to guide patient-centered interventions. For instance, negative reviews consistently mentioning rude staff could prompt clinic managers to organize targeted communication and anti-stigma training, with the potential to improve patient engagement in mental healthcare.

Limitations

Limitations inherent to online reviews include that reviews skew towards extremes, and that fake reviews may escape algorithmic detection. In addition, Yelp users are not representative of those needing mental healthcare. According to Yelp, US users are almost equally distributed between the ages of 18–34, 35–54, and 55 and over. Users skew heavily towards at least some college (82%), and half of users have an income above $100,000 a year.(26) According to a 2018 SAMHSA report, “any mental illness” was most common among those aged 18 to 49, and among those 18 and older, approximately 64% had at least some college education and 24% were living below the poverty line.(1) Yelp is therefore at least over-representative of those with high education and income. Yelp notably does not report on the racial-ethnic demographics of its users, and several racial-ethnic groups in the US, particularly Black and Latinx people, face persistent barriers to mental healthcare.(41) In the future, dialogue with those with lived experience of mental health treatment, and those with specific barriers to care, will be necessary to determine how well Yelp themes encompass factors contributing to patient satisfaction.

This study was further limited by a relatively low proportion of SAMHSA facilities with Yelp pages. Google and Facebook reviews are not accessible through application programming interfaces, but may include facilities not found on Yelp..(21) Sub-analyses by facility type, e.g. inpatient vs. outpatient and adult vs. child, were not conducted due to limitations in sample size. These analyses, and evaluations of emergency psychiatric care and of tele-psych communication, will be important as further online review data becomes available.

A limitation of natural language processing is that identified themes cannot always be easily addressed.(23) For instance, despite a negative correlation between pharmacologic treatment and review ratings, in many cases evidence supports the use of medication in treating mental illness. Knowledge of patient aversion to medication, however, can help set the foundation for therapeutic alliance.

Finally, while we were able to compare facility ratings to standard facility-level characteristics through N-MHSS data, there is no nationally reported facility rating system for mental health facilities in the United States (e.g. Hospital Compare for hospitals), against which to measure Yelp review ratings. Evidence from studies where such comparisons were possible point to correlations ranging from 0.09 to 0.5.(16, 20)

Conclusion

Online reviews are powerful in that they are unscripted, and as such, the themes that arise from these review narratives are naturally “patient-centered”. Our study’s findings regarding review ratings and the narrative content of reviews are consistent with both national survey data and the available literature. In the absence of the wide-spread adoption of validated patient-centered outcome measures in mental health, online reviews of mental health facilities have the potential to guide interventions to improve patient satisfaction.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

This study utilizes natural language processing of 8,133 online patient reviews, in combination with review ratings and National Mental Health Services Survey data, to understand thematic features associated with positive and negative ratings of mental health care

Themes associated with positive ratings included caring staff, non-pharmacologic treatment, and therapeutic alliance, while those associated with negative ratings included concerns around safety and abuse, pharmacotherapy, and poor communication with family

Limitations include that online reviews skew towards extreme opinions, and that the only available national-level data for comparison is survey data that does not include patient ratings, perspectives, or outcomes

Disclosures and acknowledgments

Dr. B reports receiving royalties from Oxford University Press and funding from NIH and CDC grants; she has provided consulting to Merck and the Camden Coalition of Healthcare Providers.

Footnotes

All other authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

The authors declare that these data have not been previously described or published.

Contributor Information

Daniel C. Stokes, Penn Medicine Center for Digital Health, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Center for Emergency Care Policy and Research, Department of Emergency Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Rachel Kishton, National Clinician Scholars Program, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Haley J. McCalpin, Penn Medicine Center for Digital Health, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Arthur P. Pelullo, Penn Medicine Center for Digital Health, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Zachary F. Meisel, Center for Emergency Care Policy and Research, Department of Emergency Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Rinad S. Beidas, Department of Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Penn Medical Ethics and Health Policy, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; Penn Implementation Science Center at the Leonard Davis Institute, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Raina M. Merchant, Penn Medicine Center for Digital Health, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Center for Emergency Care Policy and Research, Department of Emergency Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

References

- 1.Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health [Internet]. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019[cited 2019 Dec 9] Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jorm AF, Patten SB, Brugha TS, et al. : Has increased provision of treatment reduced the prevalence of common mental disorders? Review of the evidence from four countries. World Psychiatry 2017; 16:90–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vigo DV, Kestel D, Pendakur K, et al. : Disease burden and government spending on mental, neurological, and substance use disorders, and self-harm: cross-sectional, ecological study of health system response in the Americas. The Lancet Public Health 2019; 4:e89–e96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, et al. : The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ 2004; 82:858–866 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon LB, Holoshitz Y, Nossel I: Treatment engagement of individuals experiencing mental illness: review and update. World Psychiatry 2016; 15:13–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tambuyzer E, Audenhove CV: Is perceived patient involvement in mental health care associated with satisfaction and empowerment? Health Expectations 2015; 18:516–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ratner Y, Zendjidjian XY, Mendyk N, et al. : Patients’ satisfaction with hospital health care: Identifying indicators for people with severe mental disorder. Psychiatry Research 2018; 270:503–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vermeulen JM, Schirmbeck NF, van Tricht MJ, et al. : Satisfaction of psychotic patients with care and its value to predict outcomes. Eur Psychiatry 2018; 47:60–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders: Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions: Quality Chasm Series [Internet]. Washington (DC), National Academies Press (US), 2006[cited 2019 Oct 17] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK19830/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kilbourne AM, Beck K, Spaeth-Rublee B, et al. : Measuring and improving the quality of mental health care: a global perspective. World Psychiatry 2018; 17:30–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank L, Basch E, Selby JV: The PCORI Perspective on Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. JAMA 2014; 312:1513–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inpatient Psychiatric Facility Quality Measure Data – by Facility | Data.Medicare.gov [Internet][cited 2019 Oct 17] Available from: https://data.medicare.gov/Hospital-Compare/Inpatient-Psychiatric-Facility-Quality-Measure-Dat/q9vs-r7wp [Google Scholar]

- 13.CAHPS Hospital Survey (HCAHPS): Quality Assurance Guidelines [Internet]. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2018[cited 2020 Jul 20] Available from: https://hcahpsonline.org/globalassets/hcahps/quality-assurance/2018_qag_v13.0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Mental Health Services Sruvey (N-MHSS): 2018. Data on Mental Health Treatment Facilities [Internet]. Rockville, MD, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019[cited 2020 Jul 21] Available from: https://wwwdasis.samhsa.gov/dasis2/nmhss/NMHSS-2018-C.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merchant RM, Volpp KG, Asch DA: Learning by Listening—Improving Health Care in the Era of Yelp. JAMA 2016; 316:2483–2484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ranard BL, Werner RM, Antanavicius T, et al. : Yelp Reviews Of Hospital Care Can Supplement And Inform Traditional Surveys Of The Patient Experience Of Care. Health Affairs 2016; 35:697–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bardach NS, Lyndon A, Asteria-Peñaloza R, et al. : From the closest observers of patient care: a thematic analysis of online narrative reviews of hospitals. BMJ Qual Saf 2016; 25:889–897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kilaru AS, Meisel ZF, Paciotti B, et al. : What do patients say about emergency departments in online reviews? A qualitative study. BMJ Qual Saf 2016; 25:14–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agarwal AK, Mahoney K, Lanza AL, et al. : Online Ratings of the Patient Experience: Emergency Departments Versus Urgent Care Centers. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2019; 73:631–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johari K, Kellogg C, Vazquez K, et al. : Ratings game: an analysis of Nursing Home Compare and Yelp ratings. BMJ Qual Saf 2018; 27:619–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agarwal AK, Wong V, Pelullo AM, et al. : Online Reviews of Specialized Drug Treatment Facilities—Identifying Potential Drivers of High and Low Patient Satisfaction [Internet]. J GEN INTERN MED 2019; [cited 2019 Nov 22] Available from: 10.1007/s11606-019-05548-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graves RL, Goldshear J, Perrone J, et al. : Patient narratives in Yelp reviews offer insight into opioid experiences and the challenges of pain management. Pain Management 2018; 8:95–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibbons C, Greaves F: Lending a hand: could machine learning help hospital staff make better use of patient feedback? BMJ Qual Saf 2018; 27:93–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cognetta-Rieke C, Guney S: Analytical Insights from Patient Narratives: The Next Step for Better Patient Experience. J Patient Exp 2014; 1:20–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryskina KL, Andy AU, Manges KA, et al. : Association of Online Consumer Reviews of Skilled Nursing Facilities With Patient Rehospitalization Rates. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3:e204682–e204682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fast Facts [Internet]. Yelp Newsroom; 2020; [cited 2020 Jul 16] Available from: https://www.yelp-press.com/company/fast-facts/default.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 27.All Category List - Yelp Fusion [Internet][cited 2019 Nov 14] Available from: https://www.yelp.com/developers/documentation/v3/all_category_list

- 28.Van der Loo MP: The stringdist package for approximate string matching. The R Journal 2014; 6:111–122 [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKenzie G, Janowicz K, Adams B: Weighted multi-attribute matching of user-generated points of interest, inProceedings of the 21st ACM SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems. ACM, 2013, pp 440–443. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shields MC, Stewart MT, Delaney KR: Patient Safety In Inpatient Psychiatry: A Remaining Frontier For Health Policy. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018; 37:1853–1861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McHugh RK, Whitton SW, Peckham AD, et al. : Patient Preference for Psychological vs. Pharmacological Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: A Meta-Analytic Review. J Clin Psychiatry 2013; 74:595–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kern ML, Eichstaedt JC, Schwartz HA, et al. : From “Sooo excited!!!” to “So proud”: using language to study development. Dev Psychol 2014; 50:178–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.R Core Team: R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Internet]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2019Available from: https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chevalier A, Ntala E, Fung C, et al. : Exploring the initial experience of hospitalisation to an acute psychiatric ward [Internet]. PLoS One 2018; 13[cited 2020 Jan 7] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6122813/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Staniszewska S, Mockford C, Chadburn G, et al. : Experiences of in-patient mental health services: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 2019; 214:329–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manary MP, Boulding W, Staelin R, et al. : The patient experience and health outcomes. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:201–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, et al. : The Cost of Satisfaction: A National Study of Patient Satisfaction, Health Care Utilization, Expenditures, and Mortality. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172:405–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, et al. : What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med 2015; 45:11–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang K, Link BG, Corrigan PW, et al. : Perceived provider stigma as a predictor of mental health service users’ internalized stigma and disempowerment. Psychiatry Res 2018; 259:526–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Windle E, Tee H, Sabitova A, et al. : Association of Patient Treatment Preference With Dropout and Clinical Outcomes in Adult Psychosocial Mental Health Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis [Internet]. JAMA Psychiatry 2019; [cited 2019 Dec 8] Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/2756319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cook BL, Trinh N-H, Li Z, et al. : Trends in Racial-Ethnic Disparities in Access to Mental Health Care, 2004–2012. PS 2016; 68:9–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.