To the Editor:

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has strained intensive care unit (ICU) resources across the world. One of several public health challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic has been the accurate counting of COVID-19 cases (1). International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) (2) codes are widely used to track the epidemiology of diseases. However, ICD codes may not accurately reflect disease status (3, 4). In April 2020, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated ICD-10 codes to include the code U07.1, COVID-19 for clinicians to document the presence of COVID-19 (5). Kadri and colleagues (6) identified the rapid uptake and high diagnostic accuracy of the COVID-19 ICD-10 code among hospitalized patients in the early pandemic. However, the degree to which the COVID-19 ICD-10 code reflects COVID-19 infection in critically ill patients and its accuracy over time are unclear. In this study, we sought to assess the accuracy of the COVID-19 ICD-10 code among adult patients admitted to U.S. ICUs and stepdown units in 2020.

We used the Premier Inc. database, an enhanced multicenter U.S. claims-based database with laboratory values available for a patient subset (7), to identify patients for study inclusion. Included patients were 1) adults (⩾18 yr) with a 2) hospital encounter that included a general or medical ICU or stepdown unit admission, who were 3) discharged between April 2020 and December 2020, and who had 4) at least one severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) ribonucleic acid polymerase chain reaction (PCR) laboratory test result (positive or negative) during the hospitalization. For each patient, we extracted results from all SARS-CoV-2 PCR tests and use of the ICD-10 code U07.1. COVID-19 positivity (gold standard) was defined as a positive result from any SARS-CoV-2 PCR test during the hospitalization. The SARS-CoV-2 antigen test was not used as gold standard owing to its rare use (3,464 tests performed in the database; 393 were positive).

We evaluated performance characteristics of the ICD-10 discharge code U07.1 for COVID-19 status based on the gold-standard SARS-CoV-2 PCR laboratory test result: 1) sensitivity, 2) specificity, 3) positive predictive value (PPV), 4), negative predictive value, and 5) c-statistic. In stratified analyses, we calculated performance statistics by 1) age, 2) sex, 3) race, 4) acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or acute respiratory failure (ARF) diagnoses, 5) use of mechanical ventilation, 6) admission to the ICU, and 7) discharge month. We stratified by month to assess for changes in performance due to changes in COVID-19 prevalence and changes in coding strategies over time. Lastly, we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding patients admitted as transfers from outside healthcare facilities to account for patients who might have previously positive testing and thus might not receive a second SARS-CoV-2 test. This study was designated not Human Subjects Research by Boston University’s Institutional Review Board (#H-41991).

Among 274,392 adult ICU and stepdown patients, 180,426 (65.8%) from 214 hospitals had a SARS-CoV-2 PCR test and were thus included in the study. SARS-CoV-2 laboratory tests were positive in 22,700 (12.4%) of tested patients (8.3% of all ICU and stepdown patients). Compared with patients with negative tests, patients with positive SARS-CoV-2 tests had higher rates of ARDS or ARF diagnoses (70.9%), mechanical ventilation (25.0%), and death (20.5%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of ICU patients with SARS-CoV-2 testing

| SARS-CoV-2 Positive (n = 22,700) | SARS-CoV-2 Negative (n = 157,726) | Overall (N = 180,426) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | |||

| <65 | 10,097 (44.5) | 71,026 (45.0) | 81,123 (45.0) |

| ⩾65 | 12,603 (55.5) | 86,700 (55.0) | 99,303 (55.0) |

| Sex* | |||

| Female | 9,913 (43.7) | 73,845 (46.8) | 83,758 (46.4) |

| Male | 12,786 (56.3) | 83,875 (53.2) | 96,661 (53.6) |

| Race | |||

| Asian | 513 (2.3) | 3,034 (1.9) | 3,547 (2.0) |

| Black | 4,642 (20.4) | 25,090 (15.9) | 29,732 (16.5) |

| Other | 2,224 (9.8) | 7,585 (4.8) | 9,809 (5.4) |

| Unknown | 997 (4.4) | 4,352 (2.8) | 5,349 (3.0) |

| White | 14,324 (63.1) | 117,665 (74.6) | 131,989 (73.2) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 5,665 (25.0) | 23,963 (15.2) | 29,628 (16.4) |

| ARDS or ARF diagnosis | 16,091 (70.9) | 49,737 (31.5) | 65,828 (36.5) |

| Hospital mortality | 4,644 (20.5) | 10,571 (6.7) | 15,215 (8.4) |

| Admission to the ICU | 11,496 (50.6) | 79,496 (50.4) | 90,992 (50.4) |

Definition of abbreviations: ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; ARF = acute respiratory failure; ICU = intensive care unit; SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Data are shown as n (%).

Sex was unknown for seven patients.

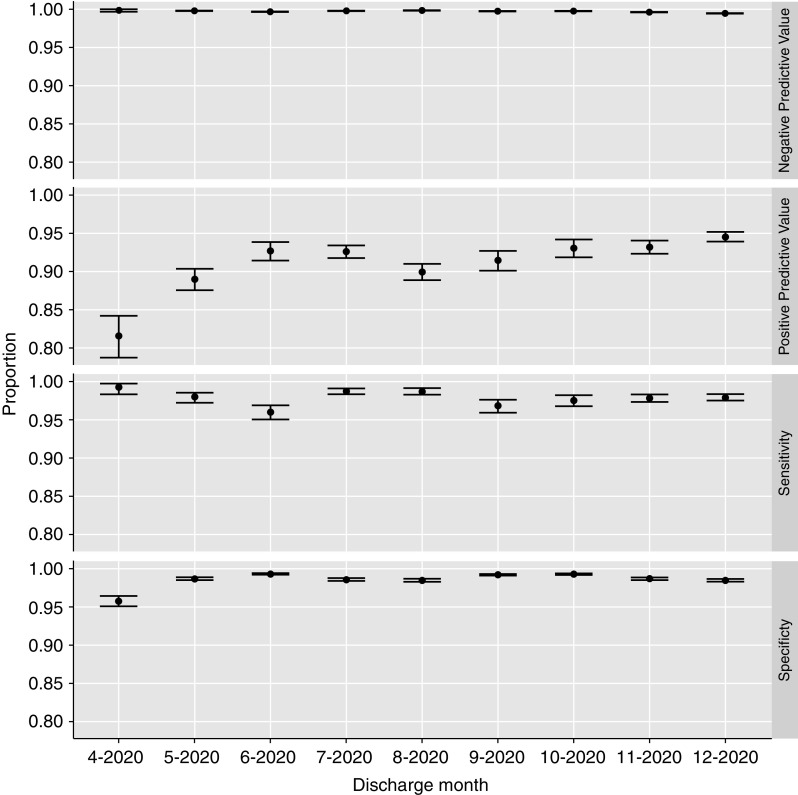

The overall sensitivity and specificity of the COVID-19 ICD-10 code was 0.98 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.98–0.98) and 0.99 (0.99–0.99), respectively. The overall PPV was 0.92 (0.92–0.92), negative predictive value was 1.00 (1.00–1.00), and the c-statistic was 0.98 (0.98–0.99). Excluding patients admitted from other healthcare facilities (n = 151,509) resulted in marginal increases in performance (c-statistic, 0.99 [0.98–0.99]). Stratified analyses were similar to the primary analysis, showing high performance of the U07.1 ICD-10 code across subgroups with 1) the lowest sensitivity (0.96 [0.95–0.96]) among patients without a diagnosis of ARDS or ARF, 2) the lowest specificity (0.97 [0.97–0.97]) among patients who received mechanical ventilation, and the lowest c-statistic (0.98 [95% CI, 0.97–0.98]) among patients without a diagnosis of ARDS or ARF. Performance was similar in patients admitted to ICUs (sensitivity, 0.98 [0.98–0.98]; specificity, 0.99 [0.99–0.99]) and in patients admitted only to stepdown units (sensitivity, 0.98 [0.98–0.98]; specificity, 0.99 [0.99–0.99]). Performance characteristics were largely stable by month of discharge (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Performance of the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision code U07.1 for the diagnosis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) from April 2020 to December 2020. Shown are point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for negative predictive value, positive predictive value, sensitivity, and specificity for each month.

We used a large U.S. multicenter enhanced claims database to examine the accuracy of the COVID-19 ICD-10 code for patients admitted to ICUs and stepdown units. More than 8% of ICU and stepdown unit admissions across more than 200 U.S. hospitals had a positive COVID-19 test in 2020. The ICD-10 code U07.1 was highly accurate for identifying critically ill patients with COVID-19; accuracy remained high across subgroups and over time. These results provide confidence in the use of claims data for COVID-19 surveillance among critically ill patients.

The performance of the COVID-19 ICD-10 U07.1 code in our study was similar to its performance among all hospitalized patients in the early pandemic (6). Building on this prior study, our study found that the performance of U07.1 was high among critically ill patients and persisted throughout the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. We speculate that the accurate coding of COVID-19—compared with other viral respiratory diseases (8)—may reflect increased scrutiny by hospitals to accurately document COVID-19 in the setting of reimbursement programs (9, 10). In addition, our results provide reassurance that media reports (11) suggesting hospitals overcount COVID-19 cases for reimbursement reasons are unfounded.

Strengths of our study include the large multicenter cohort, examination of performance characteristics over time to account for changes in prevalence and documentation practices, and similar results from the sensitivity and subgroup analyses. Our study also has limitations. First, although our study found that U07.1 correlates well with a positive SARS-CoV-2 test, neither the ICD-10 code nor a positive test necessarily indicates symptomatic COVID-19. In addition, long turnaround times of the PCR test early in the pandemic may have led to more frequent “empiric” coding for COVID-19 while tests were processing, thus decreasing the initial PPV of the ICD-10 code.

In conclusion, ICD-10 code U07.1 is highly specific and sensitive for SARS-CoV-2 infection and thus should be an accurate marker of disease activity in claims-based databases.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: N.A.B. takes responsibility for the integrity of the letter. All authors substantially contributed to the conception and design of this study. N.A.B. acquired the data. All authors were involved in the interpretation of data. N.A.B. drafted the manuscript and all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Mahase E. Covid-19: the problems with case counting. BMJ . 2020;370:m3374. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) 2020. [2021 Oct 14]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10.htm.

- 3. Ku JH, Henkle EM, Aksamit TR, Winthrop KL. Limited validity of diagnosis code-based claims to identify Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients with bronchiectasis in Medicare data. Ann Am Thorac Soc . 2021;18:1246–1249. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202007-767RL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ley B, Urbania T, Husson G, Vittinghoff E, Brush DR, Eisner MD, et al. Code-based diagnostic algorithms for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Case validation and improvement. Ann Am Thorac Soc . 2017;14:880–887. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201610-764OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC. ICD-10-CM Official Coding and Reporting Guidelines April 1, 2020 through September 30, 2020 2020. [2021 Oct 14]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/icd/COVID-19-guidelines-final.pdf

- 6. Kadri SS, Gundrum J, Warner S, Cao Z, Babiker A, Klompas M, et al. Uptake and accuracy of the diagnosis code for COVID-19 among US hospitalizations. JAMA . 2020;324:2553–2554. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.20323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Premier. White Paper: PINC AlTM Healthcare Data. 2020 [2021 Oct 14]. Available from: https://offers.premierinc.com/WC_PAS_WP_2019_10_24_Landing-Page.html.

- 8. Hamilton MA, Calzavara A, Emerson SD, Djebli M, Sundaram ME, Chan AK, et al. Validating International Classification of Disease 10th Revision algorithms for identifying influenza and respiratory syncytial virus hospitalizations. PLoS One . 2021;16:e0244746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Health Resources & Services Administration. About the Provider Relief Fund and Other Programs 2021. [2021 Oct 14]. Available from: https://www.hrsa.gov/provider-relief/about

- 10.Courtney J., Text - H.R.748–116th Congress (2019–2020): CARES Act 2020. [2021 Oct 14]. Available from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748/text

- 11.The Spectator. Hospitals Get Paid More to List Patients as COVID-19 and Three Times as Much if the Patient Goes on Ventilator (VIDEO) 2020. [2021 Oct 14]. Available from: https://thespectator.info/2020/04/09/hospitals-get-paid-more-to-list-patients-as-covid-19-and-three-times-as-much-if-the-patient-goes-on-ventilator-video/