Abstract

The driving environmental factors behind the development of the asthma phenotype remain incompletely studied and understood. Here, we present an overview of inhaled allergic/atopic and mainly non-allergic/non-atopic or toxicant shapers of the asthma phenotype, which are present in both the indoor and outdoor environment around us. The inhaled allergic/atopic factors include fungus, mold, animal dander, cockroach, dust mites, and pollen; these allergic triggers and shapers of the asthma phenotype are considered in the context of their ability to drive the immunologic IgE response and potentially induce interactions between the innate and adaptive immune responses, with special emphasis on the NADPH-dependent reactive oxygen-species-associated mechanism of pollen-associated allergy induction. The inhaled non-allergic/non-atopic, toxicant factors include gaseous and volatile agents, such as sulfur dioxide, ozone, acrolein, and butadiene, as well as particulate agents, such as rubber tire breakdown particles, and diesel exhaust particles. These toxicants are reviewed in terms of their relevant chemical characteristics and hazard potential, ability to induce airway dysfunction, and potential for driving the asthma phenotype. Special emphasis is placed on their interactive nature with other triggers and drivers, with regard to driving the asthma phenotype. Overall, both allergic and non-allergic environmental factors can interact to acutely exacerbate the asthma phenotype; some may also promote its development over prolonged periods of untreated exposure, or possibly indirectly through effects on the genome. Further therapeutic considerations should be given to these environmental factors when determining the best course of personalized medicine for individuals with asthma.

Keywords: acrolein, adaptive immunity, butadiene, dust mites, tire breakdown particles, diesel exhaust particles, innate immunity, NADPH oxidase, ozone, ragweed pollen, reactive oxygen species, sulfur dioxide

4.1. The relationship of allergen exposure to asthma prevalence, triggers, and phenotypes

4.1.1. Seasonal Asthma and Allergen Prevalence: The Seasonal Asthmatic Phenotype

There has been a long-standing association between asthma and allergy in both children and adults. The link between asthma and certain indoor allergens, such as house-dust mite, animal dander, and cockroach, and the outdoor fungus Alternaria, has been extensively studied and is well recognized. However, those who are sensitized to outdoor aeroallergens carry less risk for asthma. Yet once development of aeroallergen sensitivity has been established, IgE-mediated reactions are a major contributor both to acute asthmatic symptoms and chronic airway inflammation (Lemanske Jr & Busse, 2010). Although sensitization to outdoor allergens poses less of a risk for asthma, studies have shown exposure to outdoor allergens such as grass and ragweed pollen has been associated with seasonal asthma. There are seasonal variations in asthma, with symptoms improving in summer, and symptoms worsening in fall and winter in the United States. This seasonal allergen exposure and subsequent sensitization has been implicated in asthma exacerbations and even in sudden asthma-related deaths (Sykes & Johnston, 2008).

The NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey), one of the landmark cohorts to study asthma, provided data on the importance of reactivity to certain aeroallergens and the subsequent effect on respiratory disease. The NHANES II, published in 1992, specifically presented which allergens are directly associated with asthma (Gergen & Turkeltaub, 1992). The number of positive allergen skin prick tests correlated with the risk of asthma. Reactivity to any one allergen increased the risk of asthma by two to three times, except for Alternaria where the increased risk was almost five times. Although sensitization to Alternaria and house dust were the two allergens that provided the highest risk of developing asthma, there was also a positive correlation with ryegrass, ragweed, and oak (Gergen & Turkeltaub, 1992). The NHANES III data, which resulted in 2007, revealed that of 10 allergens tested for, only cat, Alternaria, and white oak showed significant, positive associations with asthma after adjustment by the subject characteristics and all other allergens (Arbes, Gergen, Elliott, & Zeldin, 2005). Although the NHANES II and III data concluded that many cases of asthma are attributable to atopy, the study did not discuss the seasonal impact of allergens on risk of asthma.

The Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP) is another landmark cohort that provided years of data on children with asthma. One purpose of the CAMP was to evaluate the relationship between sensitivity and exposure to inhalant allergens and pulmonary function and bronchial responsiveness in sensitized asthmatic children (Nelson et al., 1999). Using allergy skin testing, house dust mite collection, and determination of allergen exposure, the researchers concluded that only sensitivity to the indoor allergens dog and cat dander and the outdoor fungus Alternaria demonstrated significant increases in bronchial hypersensitivity (Nelson et al., 1999).

In addition to the NHANES and CAMP data, there have been many more studies in the United States that have examined the seasonal effect of allergens on asthma. One such study looked at the median weekly asthma admissions by age group to a hospital in Maryland from 1986-1999. The researchers concluded that asthma admissions increase four- to eightfold in the fall compared to the summer (Blaisdell et al., 2002). A study from 1986 established that the largest number of asthma admissions to a hospital in California occurred during the grass-pollen season (Reid et al., 1986). Recently a study examined the effect of temperature and season on adult emergency department visits for asthma in North Carolina. This study found that the number of ER visits for asthma peaked in February (when daily temperatures were coldest) and were lowest in July (when daily temperatures were warmest) (Buckley & Richardson, 2012).

International studies have also revealed the same seasonal phenomenon. For example, one study looked at the hospital admissions for asthma in Malta. Analysis revealed a peak in January and a trough in August for both pediatric and adult hospital admissions for acute asthma exacerbations (Grech, Balzan, Asciak, & Buhagiar, 2002). Another study in the Netherlands concluded that there was a decline in asthma symptoms and asthma medication use during the summer period and a peak during autumn to spring in pediatric patients over a one year time period (Koster, Raaijmakers, Vijverberg, van der Ent, & Maitland-van der Zee, 2011). Another study revealed that in Taiwanese children aged 6–8, asthma and rhinitis peaked in winter, especially in December. However, they also found that children aged 13–15 had two peaks (winter and summer) for asthma and rhinitis (Kao, Huang, Ou, & See, 2005). In another study done in Taiwan, school-aged children had a sharp increase in the number of asthma admissions in September and March that synchronized with school re-openings (Xirasagar, Lin, & Liu, 2006). An additional study from Taiwan revealed differences among adult and childhood asthma seasonality. Although the asthma-related hospital admission for adults remained low in summer and increased in winter, the researchers concluded that adult asthma hospitalizations were highest in spring and significantly correlated with air pollution and climate (Chen, Xirasagar, & Lin, 2006). In Australia, researchers have recently found that there is a clear relationship between increased risk of childhood asthma emergency room visits and increased levels of ambient grass pollen (Erbas et al., 2012). In Canada, a study using a national data set compared asthma hospital admission rates in cities with significantly different climates. They found that independent of season and air pollution levels, a doubling in basidiomycetes spore and pollen levels and grass pollen levels was associated with increases in daily asthma hospital admission rates (Dales et al., 2004).

In addition to the many studies revealing a seasonal effect on asthma exacerbations, there is evidence that treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis improves asthma symptoms (Grembiale et al., 2000; Jacobsen, Nuchel Petersen, Wihl, Lowenstein, & Ipsen, 1997; Johnstone & Dutton, 1968; Novembre et al., 2004; Roberts, Hurley, Turcanu, & Lack, 2006). Since outdoor allergen avoidance is challenging, specific immunotherapy is used as a strategy for the prevention of development of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and asthma. The Preventive Allergy Treatment study (PAT) tested whether specific immunotherapy (SIT) could prevent the development of asthma. This study also examined whether the clinical effects of immunotherapy persist in children suffering from seasonal allergic rhinoconjunctivitis caused by allergy to birch and/or grass pollen as these children grow up (Jacobsen et al., 2007). It was demonstrated that specific immunotherapy reduced the risk of developing asthma in children suffering from allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Results were validated at termination of treatment with SIT. Results were also seen at 2 years, 7 years, and 10 years after termination of treatment, indicating a long-lasting benefit of SIT as the children grow up.

Daily oral antihistamine therapy is another treatment modality for asthma associated with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Cetirizine is described to inhibit the recruitment of inflammatory cells (mainly eosinophils) in the bronchoalveolar lavage induced by bronchial allergen inhalation challenge (Redier et al., 1992). Data has shown a protective effect of antihistamine against bronchial hyperresponsiveness. A randomized, placebo-controlled study concluded that the use of cetirizine on a daily basis is a safe and effective method to relieve upper and lower tract airway symptoms in patients with allergic rhinitis and concomitant asthma (Grant et al., 1995). Another study suggests that cetirizine may be useful in patients with asthma associated with allergic rhinitis due to the fact that this antihistamine produces a significant protective effect against allergen-induced late-phase response (Aubier, Neukirch, Peiffer, & Melac, 2001).

It is clear that there is a seasonal effect on the prevalence of asthma exacerbations, both in the United States and abroad. Research has revealed an increase in asthma exacerbations during the fall, winter, and spring; and has shown a decrease in asthma exacerbations during the summer. The causes of higher rates of asthma in the fall, winter, and spring include increased incidence of viral infection, increased prevalence of aeroallergens, and increased prevalence of air pollution. Interestingly, deaths from asthma that occur in the summer months have been hypothesized to be associated with higher levels of aeroallergens (Weiss, 1990). And as stated above there is substantiation that treatment of allergic rhinitis improves asthma symptoms.

It is difficult to elucidate whether the most significant factor affecting the seasonal differences in asthma exacerbations is aeroallergen sensitization. Thus, much research is now being conducted examining the pathophysiology of allergic asthma. Mechanisms of IgE-mediated allergic responses within airways and respiratory epithelium can help further explain the seasonal asthmatic phenotype.

4.1.2. Mechanisms of IgE-mediated allergic responses as an asthma phenotype determinant

Asthma associated with allergic responses, referred to as allergic asthma, is characterized by eosinophilic inflammation, airway hyperresponsiveness, and mucus hypersecretion (Suarez, Parker, & Finn, 2008). It is a type I hypersensitivity reaction to an environmental protein such as pollen, dust mite excreta, or animal dander. The early response in asthma is immediate, occurring minutes to hours after an exposure, and clinical manifestations can include wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, bronchoconstriction, and nasal congestion (Verstraelen et al., 2008). The late-phase asthmatic reaction occurs 4-6 hours after the early-phase reaction and is characterized by chronic airway inflammation caused by ongoing airway constriction, increased vascular permeability, enhanced airway hyperresponsiveness, and increased mucus secretion.

There is a strong causal relationship between asthma and allergens. It is now known that patients with asthma have higher serum specific IgE antibodies and total IgE levels (Platts-Mills, 2001). There are several early studies reporting the close correlation between serum IgE levels and asthma (Johansson & Bennich, 1969), (Kumar, Newcomb, & Hornbrook, 1971), (Saha, Kulpati, Padmini, Shivpuri, & Shali, 1975), (Bryant, Burns, & Lazarus, 1975), (Burrows, Martinez, Halonen, Barbee, & Cline, 1989), (Sears et al., 1991), (Sunyer et al., 1995). In 1989, Burrows and colleagues reported a close link between serum IgE levels and asthma, concluding that “asthma is almost always associated with some sort of IgE-related reaction and therefore has an allergic basis” (Burrows et al., 1989). As stated above, many other studies have revealed elevated IgE levels correlating with both physician diagnosed asthma and physiologic evidence of bronchial hyperresponsiveness. As a result, allergen-specific IgE testing in clinical practice is used to diagnosis asthma and to guide therapy.

The early asthmatic response is initiated when IgE binds to the high-affinity mast cell surface FcεI receptor, triggering mast cell and/or basophil degranulation thus resulting in the clinical manifestations of allergic disease, including narrowing of the airway. Thus, it is well known that elevated allergen-specific IgE levels in serum are a hallmark of allergic asthma. However, new data look beyond the simple causal relationship between allergy and asthma and suggest that it may be far more complex than originally thought. Several recent studies have suggested that antigen-specific memory T-cells, especially CD4+ T cells, are vital in the late-phase asthmatic response. CD4+ T cells promote airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation via secretion of Th2-type cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 (Mizutani, Goshima, Nabe, & Yoshino, 2012). This exacerbated T helper type 2 cytokine production provides the immunologic basis of atopic sensitization and response to allergens (Langier S, 2012). Interestingly, IgE also has been shown to induce production of these Th2-type cytokines in mice, leading to the development of airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation, which are characteristic of chronic asthmatic responses (Mizutani et al., 2012).

Due to the strong correlation between IgE and allergic asthma, treatment with an anti-immunoglobulin E monoclonal antibody, omalizumab or Xolair, has become an option for those adults and children over the age of 12 with moderate-to-severe allergic asthma in which inhaled corticosteroids have been ineffective. Omalizumab works by interrupting the asthmatic response at its initial step when IgE binds to the high-affinity mast cell surface FcεI receptor. By reducing free IgE and the binding to its receptor, there is a decrease in allergen processing and presentation to Th2 lymphocytes, along with a decrease in Th2 cell differentiation and thus a lower expression of cytokines.

In addition to Th2 responses playing an important role in allergic asthma, recent evidence has revealed that other mechanisms, such as Th1 and Th17 responses, have been implicated in the immunological and clinical phenotype of allergic asthma (S. Kerzel et al., 2012; Langier S, 2012; Mizutani et al., 2012). Much of the data on the role of Th17 immunity in the allergic response are derived from animal models. However, IL-17 has been shown to be increased in human sputum, blood, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from adult and pediatric patients with allergic asthma (S. Kerzel et al., 2012; Sebastian Kerzel et al., 2012; Mizutani et al., 2012). One recent study evaluated whether Th17 cells (CD3+ CD4+ CD161+ CCR6+ lymphocytes) are increased in children with allergic asthma and whether they are correlated with disease activity. This study found that the proportion of Th17 cells in peripheral blood was significantly increased in children with allergic asthma. In addition, the study revealed a higher proportion of Th17 cells in patients with uncontrolled and partly controlled asthma versus well-controlled asthma (Sebastian Kerzel et al., 2012). Another recent study found that the concentration of C3a in BALF is elevated in human patients undergoing a late-phase asthmatic response compared to non-atopic control patients. The researchers then looked at an IgE-sensitized mouse model and established that IgE mediates the increase of IL-17+CD4+ cells in the lungs through C3a production. Because of this finding, they examined the effects of an anti-IL-17 monoclonal antibody. The mAb reduced the late-phase asthmatic response, as they witnessed a reduction in airway resistance, airway hyperresponsiveness, and neutrophilic accumulation (Zhao, Lloyd, & Noble, 2012).

4.1.3. Pollen as a critical allergen facilitator of the asthmatic phenotype

The exact mechanisms of allergic asthma have yet to be confirmed and continue to be researched extensively, as stated above. One area of investigation focuses on the interactions of particular allergens with the human respiratory epithelium. It is known that several cysteine and serine protease allergens function as Th2 adjuvants, thus explaining their role in asthma (Wills-Karp, Nathan, Page, & Karp, 2010). For example, Der p 1, a cysteine protease, and Der p 9, a serine protease, both induce release of cytokines from human bronchial epithelium and respiratory epithelial cells (Röschmann et al., 2009). Proteases from Aspergillus fumigatus induce IL-6 and IL-8 production and Pen ch 13, a serine protease from Penicilllum chrysogenum, induces prostaglandin-E2, IL-8, and TGF-B1, from human airway epithelial cells (Röschmann et al., 2009). In addition, removal of proteases from A. fumigatus, German cockroach frass, American cockroach Per a 10 antigen, Epi p1 antigen (from the fungus Epicoccum purpurascens) or Cur 11 antigen (from the mold Curvularia Iunata) was reported to decrease airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in mouse models of allergic asthma (Wills-Karp et al., 2010).

Extracts from different pollen have been shown to induce cytokine release as well. A study was recently conducted examining Ph1 p 1, the major allergen of timothy grass Phleum pratense, and its role in IgE reactivity in allergic individuals. The aim of the study was to investigate whether Ph1 p 1 has the ability to activate human respiratory epithelial cells and whether this ability is protease-dependent (Röschmann et al., 2009). The authors concluded that pollen grains in general function as allergen carriers and contain bioactive lipids that attract cells in allergic inflammation. Ph1 p 1 induces expression and release of IL-8, IL-6, and TGF-β in alveolar epithelial cells in vitro, without using a direct proteolytic mechanism (Röschmann et al., 2009). Using this pollen allergen in vitro model, we can further elucidate the pathogenesis of allergic asthma. IL-6 is known to be important in recruitment and activation of neutrophils. IL-8 is also known to recruit neutrophils and is a key chemokine in the attraction of monocytes and macrophages to sites of inflammation. Thus, the Ph1 p 1 allergen itself plays a vital role in perpetuating the allergic response in both early and late-phase asthmatic reactions.

Other studies have demonstrated that in addition to releasing particular allergens, pollen extrudes bioactive lipids, or pollen-associated lipid mediators (PALMs), that then stimulate neutrophils and eosinophils in vitro (Plotz et al., 2004). Taking from this recent demonstration of pollen-derived lipid components being an important factor in the development of IgE-mediated allergic hypersensitivity, another study examined the ability of birch pollen extracts to affect maturation and cytokine release from human dendritic cells, therefore inducing Th2 responses (Traidl-Hoffmann et al., 2005). The study demonstrated that an aqueous pollen extract from birch (Betula alba L.), or Bet.-APE, modulates the function of human dendritic cells which induces Th2-dominated adaptive immune responses (Traidl-Hoffmann et al., 2005). A more recent study also examined the role of PALMs, specifically the E1-phytoprostanes (PPE1), and Bet.-APE in the enhancement of dendritic cell mediated Th2 polarization of naïve T cells. This study found that Bet.-APE strongly and dose-dependently induces intracellular formation of cAMP. Incubation of dendritic cells with Bet.-APE lead to enhanced secretion of Th2-attracting chemokines, such as CCL17 (Gilles et al., 2009). Because of the strong induction of cAMP and the strong Th2-polarizing effect of the birch pollen extract Bet.-APE both in vitro and in vivo, this study suggests that there must be additional bioactive substances contributing to this effect, thus indicating the need for future research in this area (Gilles et al., 2009).

For the first time in 2005, researchers investigated the role of NADPH oxidases in pollens and subpollen particles and their effect on allergic airway inflammation. A landmark study was published looking specifically at ragweed pollen extract, which contains NADPH oxidase activity, in the recruitment of inflammatory cells and the development of allergy. Looking at cultured epithelial cells and murine conjunctiva, the study found that NADPH oxidases from the pollen extracts generate superoxides which in turn increase intracellular reactive oxygen species. The conclusion was made that ragweed pollen induced-oxidative stress is an independent process of adaptive immunity. They also showed that inactivation of the pollen NADPH oxidase significantly decreased the accumulation of inflammatory cells into the conjunctiva (Bacsi, Dharajiya, Choudhury, Sur, & Boldogh, 2005). Since that study, the role of NADPH oxidase in allergic inflammation has been studied further and a two-signal hypothesis for the induction of allergic inflammation has been proposed, with signal 1 consisting of innate reactive oxygen species, and signal 2 consisting of the classical pathway of antigen presentation to T cells (Dharajiya, Boldogh, Cardenas, & Sur, 2008). The role of pollen-induced oxidative stress on the airway epithelium in mice has been extended further to include how pollen grain exposure triggers oxidative stress in dendritic cells and mast cells (Chodaczek et al., 2009; Csillag et al., 2010). This adds growing evidence to the fact that oxidative stress from pollen grains contributes to allergic airway inflammation.

4.1.4. Adaptive vs. innate immune responses: contribution to heterogeneous asthma phenotype

There are complex interactions between both innate and adaptive immune cells that lead to the symptoms of both the early and late-phase asthmatic response. The innate immune cells that may control allergic responses in the lung include phagocytic cells such as alveolar macrophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophils; nonphagocytic leukocytes such as natural killer cells, mast cells, eosinophils, and basophils; and epithelial cells, specifically bronchial epithelial cells (Verstraelen et al., 2008).

Bronchial epithelial cells are involved in allergic airway inflammation by secreting cytokines and augmenting inflammatory cells (Suarez et al., 2008). It has been shown that upon exposure to a particular allergen Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, bronchial epithelial cells will produce the pro-inflammatory cytokines granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IL-8, and TGF-α, which all contribute to allergic airway inflammation (Lordan et al., 2002). Bronchial epithelial cells are also a source of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) which is a cytokine that enhances Th2 responses. It has been shown that TSLP is abundant in the airway epithelium of mice and human subjects with allergic asthma (Suarez et al., 2008). TSLP can activate dendritic cells and mast cells to produce Th2 cytokines (Kool, Hammad, & Lambrecht, 2012; Suarez et al., 2008).

Alveolar macrophages are important in first-line defense, along with bronchial epithelial cells, against respiratory pathogens and allergens. They can attenuate the immune response in the lung, thus suppressing some of the clinical manifestations of allergic asthma (Suarez et al., 2008). Although macrophages can have both pro-inflammatory and suppressive functions in the lung, overall, evidence indicates that they tend to inhibit immune activation and inflammatory cell entry into the lungs after the inhalation of respiratory allergens (Verstraelen et al., 2008). Upon inhalation of an allergen, alveolar macrophages secrete substances such as TGF-β and prostaglandin E2, thus suppressing airway inflammation. However, it is shown that once these macrophages are sensitized to allergen, their ability to produce these anti-inflammatory mediators is diminished (Suarez et al., 2008).

Dendritic cells are involved in the pathogenesis of allergic asthma due to their role in the chemotaxis of T cells in ongoing inflammation (Verstraelen et al., 2008). It has been shown that dendritic cells can recruit Th2 cells at sites of inflammation during the late-phase asthmatic reaction. As stated above, dendritic cells can be activated by TSLP, thus enhancing the Th2 response, a step necessary in allergic sensitization. Dendritic cells have also been found to be involved in memory immune responses with regards to allergic disorders (Suarez et al., 2008).

Innate immune molecules like toll-like receptors (TLRs) and NOD (nucleotide oligomerization domain) -like receptors (NLRs) also play an important role in airway epithelial cells generating a response to a complex allergen. Respiratory epithelial cells express endosomal TLRs which signal a series of adaptor proteins upon ligand attachment (Lambrecht & Hammad, 2012). This results in the activation of NF-κB and the production of several pro-inflammatory cytokines, interferons, chemokines, prostaglandins and defensins. In addition, activation of NODs, specifically NOD-1 and NOD-2 in respiratory epithelium, results in MAPK and NF-κB-dependent production of inflammatory mediators (Lambrecht & Hammad, 2012).

4.2. Gaseous, volatile. and particulate environmental triggers as determinants of the Asthmatic Phenotype

4.2.1. Small gas molecule environmental pollutant triggers: Phenotype Shapers or Interactors?

4.2.1.1. Sulfur dioxide

General Characteristics.

Sulfur dioxide (SO2) exists as a colorless tri-atomic gas, having two oxygen atoms bound to each sulfur atom, through an alternating double bond that is shared by each of the oxygen atoms. It is also known as sulfurous anhydride or sulfur(IV) oxide, and considered the active agent in anti-bacterial sulfating chemicals utilized in wines and other food product of fruit origin. Its pungent odor is characteristically described as that of rotten eggs, with a typical odor detectability threshold that averages approximately 2.5 ppm (Pohanish, 2004). While SO2 is a relatively stable gas when dry, in the presence of water, it can form sulfur acid (H2SO4), as shown in the following stoichiometrically-balanced equation:

| (1) |

Sulfuric acid is highly corrosive (hence its classical name “oil of vitriol”), but has a number of commercial uses; therefore, its bulk production is necessary for cleaning products, fertilizers, and water treatment applications. However, sulfuric acid is also readily produced by a similar hydration reaction when SO2 gas comes in contact with rain in the atmosphere, producing the corrosive “acid rain,” (Weathers, 2006) that has been described since the Industrial Revolution, preceding, and into, the 19th century (EPA, 2013). In a similar fashion, inhaled SO2 gas can form sulfuric acid when coming into contact with the hydrated surfaces of the nasal, oral, and pulmonary airways, which can result in local oxidative stress that may be important in the development or exacerbation of asthma (Lin, Hwang, Pantea, Kielb, & Fitzgerald, 2004; Peden, 1997; Schwela, 2000).

SO2 as a Hazardous Gas.

SO2 gas is typically released when fossil fuels are either burned or processed. Examples are the burning of coal for energy, and production of gasoline from crude oil. SO2 is also released when certain metals are extracted from their crude ores, such as copper (Lin et al., 2004). Thus, it is easy to imagine that workers in commercial industries either manufacturing sulfuric acid from SO2, or engaging in processes in which SO2 is a byproduct, could be acutely exposed to toxic or even lethal levels of SO2. Accordingly, NIOSH stipulates the level of SO2 that is considered to be immediately dangerous to life or health (IDLH) as 100 ppm (CDC, 1995). However, a significant amount of SO2 is produced by diesel engines in agricultural equipment and other non-road vehicles (Decker H., 2003), and can therefore be a gaseous hazard that is readily present in areas not necessarily associated with commercial manufacturing and processing. Due to its toxicity, regulations and safety standards for SO2 have been put into place by governmental bodies such as the EPA and NIOSH, which typically stipulate an exposure concentration and time factor combination. For example, in 2010, the EPA replaced the existing primary SO2 standards with a new 1-hour exposure standard, at a maximum level of 75 ppb. NIOSH standards of exposure acceptability vary from 5 ppm for 15 minutes of SO2 exposure, to 2 ppm for 10 hours of exposure, which are similar to that of OSHA, setting an acute permissible exposure limit (PEL) of 5 ppm over 8 hours (NIOSH, 2010).

SO2 as a factor in airway dysfunction.

With the presence of diesel engines in commercial vehicles, levels of gaseous SO2 in polluted urban air can remain high, which can be problematic, given that since 1971, the EPA primary standard has been 0.14 ppm for 24 hr of exposure (EPA, 2012d), and that the SO2 odor detection threshold (2.5-3.0 ppm) is above the level at which SO2 is associated with breathing problems in asthmatics. In other words, asthmatics in those areas can be exposed chronically to SO2, without being aware of their exposure, or the source of their airway dysfunction. Subsequently, in 2010, the EPA revoked the 24-hr standard, indicating that no level of SO2 beyond 75 ppb for 1 hour was acceptable (EPA, 2012d). While acute high level exposures to SO2 gas can cause pulmonary edema and derangements of gas-exchange at the level of the alveoli, acute exposures at levels as low as 0.1-0.5 ppm can induce bronchoconstriction and bronchospasm in asthmatics, whereas these symptoms are only seen at concentrations of 5-20ppm in non-asthmatics (Lin et al., 2004; Peden, 1997; Schwela, 2000; “TOXNET: Hazardous Substances Data Bank (HSDB),” 2013). Of further interest, SO2 appears to intensify allergic responses to inhaled allergens (Cai et al., 2008; D’Amato, Liccardi, D’Amato, & Cazzola, 2002), suggesting that it can synergize or amplify asthma, in those with significant atopy.

SO2 as a phenotype shaper or interactor?

An interesting question about SO2 is whether it should be viewed as a long-term shaper of the asthma phenotype, or simply an acute interactor with other factors in the airway. Given the known toxicity of SO2 and its ability to readily form sulfuric acid in the presence of moisture, one could reasonably postulate that the oxidative stress response to inhaled SO2 due to the presence of an acidic irritant stimulus in the airway would be a most potent aggravating factor in promoting asthmatic symptoms. Thus, in considering SO2 as a shaper of asthma phenotype, the case of chronic insensible exposure to inhaled SO2, at levels below the odor threshold mentioned above, could be easily considered. For example, a person genetically pre-disposed to the development of asthma, e.g., one in which a familial diagnosis is present, might have long-term changes in their airway biology, including irreversible airway remodeling, which are only marginally managed by current asthma therapy, rather than resolved or cured (Durrani, Viswanathan, & Busse, 2011).

At this time, the state of understanding of the progression of airway remodeling and its potential reversibility over time, as well as a lack of longitudinal data about long-term low-level SO2 exposure, do not currently allow certainty in assigning SO2 the status of a persistent asthma phenotype shaper. While a number of studies have been done on SO2-associated hospital admissions and mortality (WHO, 2000), and one study indicated minimal effects on lung function at a low exposure level (Lawther, Macfarlane, Waller, & Brooks, 1975), it is not known whether persons chronically exposed to low levels of SO2 develop asthma at higher rates than those who are not exposed over the same period of time. Furthermore, it is not known whether those diagnosed with asthma associated with living in areas of chronic low-level SO2 exposure experience relinquishment of symptoms or are cured of asthma, when the chronic exposure is discontinued. Thus, SO2 may be an acute asthma phenotype shaper, but little is known about its effects on its long-term phenotypic influence on the disease.

As mentioned above, there is a significant amount of evidence that acute SO2 exposure can play an interactive role in exacerbating asthma, and this role may be attributed to its ability to form sulfuric acid in the airway and possibly become a trigger of oxidative stress. There may also be either a synergism or amplification of effects with the interaction of Th2 allergic inflammatory pathways in atopic asthmatics that is also associated with production of reactive oxygen species in the airway, which may potentiate bronchospasm and bronchoconstriction associated with asthma (Cai et al., 2008; D’Amato et al., 2002; I. T. Lee & Yang, 2012). In this context, it is interesting to consider that asthmatics have a deficiency of production of IL-10 in the airway (Borish et al., 1996), for reasons as yet unexplained, but which could be critical to the exaggerated effects of SO2 seen in asthmatics, but not seen in non-asthmatics, who are IL-10 sufficient. A question that remains unsolved is whether asthmatics are extraordinarily sensitive to the effects of SO2 because they cannot mount a significant anti-inflammatory response, with a deficiency in the production of IL-10.

4.2.1.2. Ozone

General Characteristics.

Ozone (O3), also known as tri-oxygen, like SO2, is a tri-atomic molecule consisting of three oxygen atoms that share an alternating double bond, or traveling pair of electrons. The name ozone comes from a Greek word meaning “to smell,” which describes the characteristic bleach-like odor of O3, existing as a pale-blue gas, detectable at concentrations as low as 10 ppb, after lightning storms, and with function of some older toner-based printers and photocopiers, lacking ozone filters (EPA, 2012a; Morawska et al., 2009). As shown in the stoichiometrically-balanced equation, below, O3 decomposes to simple diatomic oxygen (O2) within about 30 minutes, under standard conditions in the atmosphere (Solutions, 2013); however, recent measures suggest half-lives as long as 1500 minutes under less-disturbed conditions (McClurkin, 2010):

| (2) |

O3 is naturally present in the stratosphere of the earth’s atmosphere, comprising the “ozone layer,” at distances that average about 20 miles from the earth’s surface, and which blocks a significant amount of the sun’s ultraviolet rays, even though the concentration of O3 in that layer is typically less than 10 ppm (Sci-Link, 1995). Typically, naturally-occurring O3 levels at the earth’s surface are negligible, but can be significantly elevated locally with the burning of fossil fuels, such as gasoline and diesel fuel. The action of sunlight on the combination of nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds, which come from power plants, factories, and vehicles, can produce O3, and in large cities such as Los Angeles, O3 is a significant component of the smog layer (AQMD, 2013; Linn et al., 1986). O3 is a more powerful oxidizing agent than O2, and can oxidize metals, other gases (e.g., nitric oxide), and olefin-based polymers, and is the basis for its use industrially and commercially as a disinfectant and anti-bacterial/anti-fungal in numerous applications, including water treatment, swimming pool cleaning, fabric treatments, and fresh fruit decontamination. A further interesting use of O3 is as a disinfectant in hospital surgical rooms, in which it is pumped into a sealed operating room (de Boer, van Elzelingen-Dekker, van Rheenen-Verberg, & Spanjaard, 2006), to kill any remaining bacteria after surface cleaning.

Ozone as a Hazardous Gas.

Considering its production with the burning of gasoline in motor vehicles, and its widespread commercial and industrial use, the possibilities for inhaled O3 exposure are potentially significant in certain populous urban locations. In fact, the amount of exposure to O3 in large cities has been considered to be a strong risk factor, as at least one study has shown a strongly elevated risk of dying of lung disease, in the cities of Los Angeles and Houston, both being in the top four population centers in the United States (Jerrett et al., 2009). Similar to SO2, the toxicity of O3 has resulted in regulations and safety standards by government entities, to protect the public health. The NIOSH IDLH for O3 is 5 ppm (one-twentieth of that for SO2), while the NIOSH REL and EPA PEL is 0.1 ppm (CDC, 1994b). In 2008, the primary standard for ground-level O3 was stipulated by the EPA to be 0.075 ppm over 8 hours (AQMD, 2013), but there has been recent desire since 2010 to reduce this even further, potentially as low as 0.060 ppm, due to concern for certain sensitive groups, such as children and asthmatics, who may be affected at O3 concentrations as low as 0.085 ppm (EPA, 2010a).

Ozone as a factor in airway dysfunction.

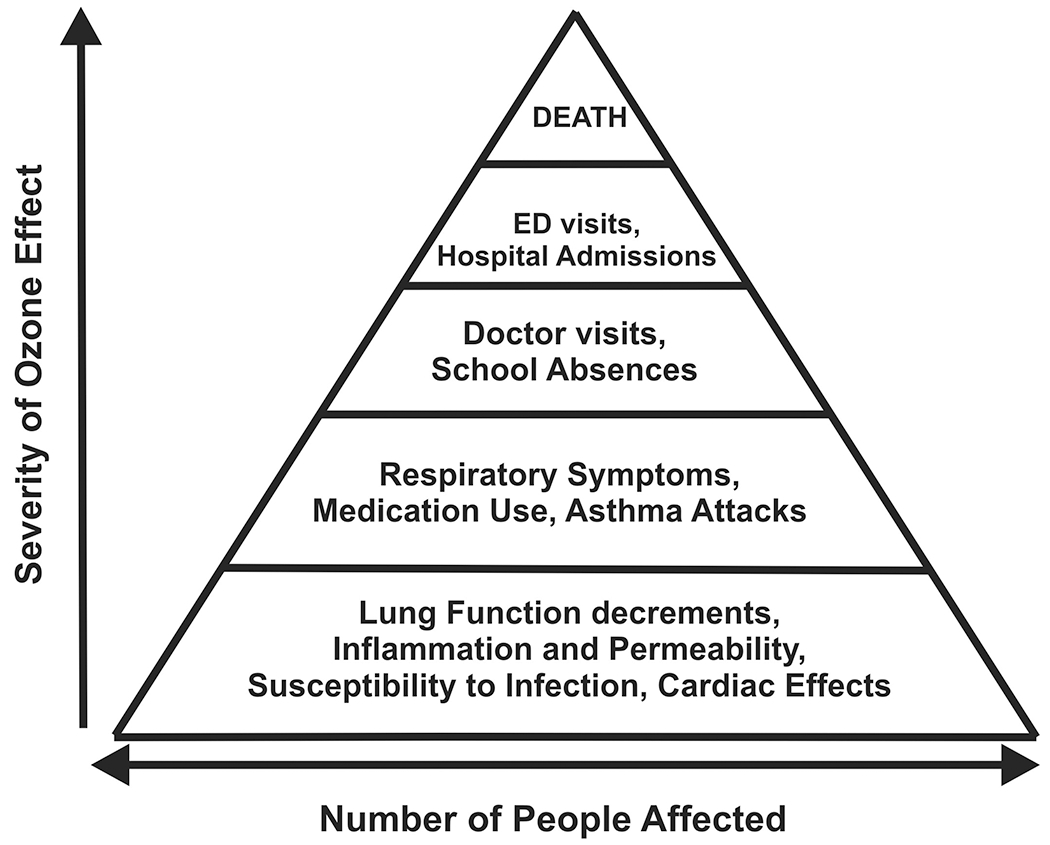

O3 is considered to be a potent source oxygen free radicals, or reactive oxygen species (ROS), which carry extra electrons within their structures that can cause damage to cell membranes, mitochondria, and DNA, leading to cell dysfunction (EPA, 2012c). Among the airway cells affected most are airway and alveolar epithelial cells, which bear the brunt of contact with inhaled O3, due to a lack of collection of O3 at higher airway levels, owing to its poor water solubility. As a result, the epithelial cells leak important enzymes and release inflammatory mediators into the airway, which can promote injury and the development of airway inflammation (Devlin, 1997). Furthermore, O3 can stimulate nociceptive nerve fibers which can lead to stimulation of the cough reflex and bronchospasm (Devlin, 1997). O3 has been reported to increase the airway responsiveness of allergic asthmatics to inhaled dust mite allergen, as drops in FEV1 (Kehrl, Peden, Ball, Folinsbee, & Horstman, 1999), indicating its potential to synergize with allergic asthma triggers to reduce lung function in atopic asthmatics. Thus, as a powerful oxidizing agent, inhaled O3 can result in significant oxidative stress within the airway, promoting bronchoconstriction, bronchospasm and asthma attacks, and even death (EPA, 2012b), as shown in the Ozone Effects Pyramid in Figure 1.

Figure 4-1: Pyramid of effects caused by ozone.

The relationship between the severity of the effect and the proportion of the population experiencing the effect can be presented as a pyramid. Many individuals experience the least serious, most common effects shown at the bottom of the pyramid. Fewer individuals experience the more severe effects such as hospitalization or death. Used by permission; from US EPA, ref 30.

Ozone as a phenotype shaper or interactor?

Perhaps more so than SO2, O3 may be a stronger factor in determining the phenotype of asthma, due to its significant oxidant-associated toxicity and the promotion of intracellular DNA damage, even at exceedingly small concentrations (Ferng, Castro, Afifi, Bermudez, & Mustafa, 1997; Steinberg, Gleeson, & Gil, 1990). For example, it is conceivable that if the site of DNA damage were genes controlling the inflammatory response or bronchial hyperresponsiveness, that an individual could become compromised in the ability to resolve inflammation resultant of exposure to other asthma triggers. Interestingly, one study indicated that nitric oxide (NO) could act to repair DNA strand breaks associated with O3 exposure in human bronchial epithelial cells in culture, which suggests a potential endogenous defense mechanism against the genotoxic effects of O3 (Cui et al., 2011).

However, it is not currently known to what level of alteration that chronic O3 inhalation can modify airway cellular function and phenotype. Thus, it is reasonable to expect that chronic O3 exposure and its attendant oxidative stress would lead to subsequent long-term modifications that are perhaps manifest in irreversible airway remodeling, consequent diminution of lung function, and the development of sustained difficult-to-treat asthma, or potentially, chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD). As in the case of SO2, it remains open to speculation and further research, as to whether the inability to mount a significant IL-10-driven airway anti-inflammatory response in asthmatics is a predisposing factor toward allowing chronic O3 exposure to shape toward a moderate to severe asthma phenotype. This consideration may be even more important, when one considers that the deleterious effects of O3 on lung function become more pronounced with aging (Devlin, 1997), which would fit with the idea that prolonged low-level exposure to O3 could lead to irreversible changes in lung function, particularly in asthmatics. Clearly, given the prominence of O3 in populous urban settings, and its potent effects in promoting DNA damage, further research is necessary to determine the potential of O3 to be an asthma phenotype shaper over the lifetime of an individual.

The characteristics of O3 that make it a powerful oxidant also make it a strong interactive agent that can acutely magnify the effects of other triggers, in people with asthma. The ability of O3 to acutely amplify allergen-associated decrements in lung function (Kehrl et al., 1999) bears consideration, in this regard. Moreover, the fact that asthma ED and hospital admissions were highly positively correlated to estimated O3 exposure, only during warmer months (Burnett et al., 1994), when the action of sunlight on nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds would be expected to be more effective in producing inhalable O3, further supports the idea that O3 can be an important interactive factor in the exacerbation of established asthma. Thus, in the case of O3, there are reasons to believe that its potency and presence in our lives make it a factor to be strongly considered as both a long-term asthma phenotype shaper requiring more global efforts toward its reduction, as well as an interactive factor requiring acute therapeutic strategies and attention.

4.2.2. Volatile Environmental Pollutant Triggers: Phenotype Shapers or Interactors?

4.2.2.1. Acrolein

General Characteristics.

Acrolein, also known as propenal, and acrylic aldehyde, is a highly electrophilic unsaturated aldehyde, which, similar to the toxic gases SO2 and O3, has a double-bonded oxygen within its molecular structure, and is a powerful oxidizer (Garg, 2001). As an oxidant, acrolein finds use as a water-treatment algaecide and herbicide in canals, irrigation systems, and other low-flow water settings, as well as in the oil drilling industry (Arntz, 2007; Faroon et al., 2008). Acrolein typically exists as colorless or pale yellow liquid, but has a characteristic “acrid” smell; hence, its name, and it is formed with high heating of cooking oils (Bein & Leikauf, 2011). Although toxic as a chemical irritant, the World Health Organization has recommended an oral acrolein intake of up to 7.5 mg/day per kg body weight, and typically fried foods result in acrolein intake levels below that threshold (Abraham et al., 2011). Acrolein is a product of many sources of incomplete combustion, including wood burning, and is also present in significant quantities in cigarette smoke (Stevens & Maier, 2008), being inhaled by smokers, but also as sidestream, second-hand, and environmental tobacco smoke, inhaled by non-smokers (Bein & Leikauf, 2011).

Acrolein as a Hazardous Compound.

Acrolein is a contact irritant of the eyes, skin, and nasal mucosa, as well as the lower airways (Ghilarducci & Tjeerdema, 1995). In humans, acrolein exposure experiments with 0.6 – 8.0 ppm over time intervals of 1 - 5 minutes, produced from slight eye irritation at low concentrations and early times, to profuse lacrimation at higher concentrations and later times (Darley E.F., 1960; Henderson Y., 1943; NRC, 1981; Sim & Pattle, 1957). Thus, the NIOSH Recommended Exposure Limit (REL) and OSHA PEL for acrolein are 0.1 ppm over 8 hours, and the IDLH is 2 ppm (CDC, 1994a). However, the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) of the State of California EPA has recommended even lower standards as of 2008, with an acute REL of 1.1 ppb, an 8-hr REL of 0.3 ppb, and a chronic REL of 0.15 ppb (CDC, 1994a). As mentioned above, acrolein is a prominent component of cigarette smoke, but as pointed out by Bein and Leikauf (Bein & Leikauf, 2011), it is of considerable interest that acrolein concentrations in sidestream smoke can be as much as 17 times higher than concentrations in mainstream smoke, due to the differences in combustion chemistry as a function of temperature. This apparent concentration of acrolein in sidestream cigarette smoke would indicate that it is a significant hazard for non-smokers who find themselves in the presence of smokers, provoking insensible and undesirable effects in their lungs that could exacerbate or drive the development of asthma.

Acrolein as a factor in airway dysfunction.

It bears notice that acrolein is clearly viewed as a potently hazardous toxic agent, which makes investigation with applied acrolein exposure in humans difficult, in part due to ethical considerations. There is a significant amount of animal study data that is suggestive of the potential effects of acrolein in the human airway, but which is outside the focus of this review. Thus, it has been acknowledged that there are no in vivo experimental human studies demonstrating acrolein effect on airway function and the development or exacerbation of asthma (Bein & Leikauf, 2011; OEHHA, 2001), which remains problematic for our full understanding of its effects in humans.

While human data about acrolein administration or exposure as a factor in airway dysfunction is scant, there are some indirect studies in humans and human tissues and cells, which indicate its potential for effects. It is of interest, for example, that comparisons of inhaled and exhaled cigarette smoke in humans demonstrate a nearly total removal of acrolein into the airways, particularly into the lower airways (Moldoveanu S., 2007). As reviewed by Bein and Leikauf (Bein & Leikauf, 2011), such indirect studies have also shown that acrolein can interact with a variety of cell structures, including the membrane, cell proteins, and nucleic acids, which substantiates expectations based on its oxidative characteristics. In agreement with these expectations, it has been reported that acrolein at a low concentration of 5 μM induces heme-oxygenase 1 (HO-1; a.k.a. heat-shock protein 32, an indicator of cell stress and inflammation) expression in cultured A549 cells (an alveolar basal epithelial cell line of human origin), but that higher concentrations considered cytotoxic, at 25-50 μM, decreased HO-1 expression (Li, Hamilton, Taylor, & Holian, 1997). Interestingly, acrolein was also shown to inhibit NF-kappaB activity in cultured human BAL macrophages, suggesting that acrolein may suppress pulmonary host defense and the ability to mount and resolve a proper inflammatory response (Li, Hamilton, & Holian, 1999; Li & Holian, 1998). Overall, data such as those above support that higher dose exposures of acrolein may promote human lung injury, while lower dose exposures may represent risk factors for the development of chronic pulmonary diseases associated with airway inflammatory processes, such as asthma and COPD (Bein & Leikauf, 2011).

Acrolein as a phenotype shaper or interactor?

Based on the lack of data in humans mentioned above, it remains difficult to confidently assign acrolein a role of phenotype shaper in humans with lung diseases, such as asthma and COPD. One contributory problem is that no specific long-term studies on acrolein exposure in humans exist from which data are available, to better understand its progressive effects. However, given its known presence in cigarette smoke, acrolein would seem to be a strong candidate as a chronic toxicant that could strongly influence the remodeling of the airways in smokers. It also stands to reason that acrolein may be a significant causative agent of lung pathology and dysfunction for people who consistently inhale sidestream smoke in the presence of smokers. Finally, its presence in secondhand and environmental tobacco smoke would also make it a potential candidate for the shaping of phenotype in those instances, as well.

Given the fact that acrolein is a powerful oxidizer and mucosal irritant, it is apparent that it could easily be considered to be an interactor, or perhaps an agent that amplifies, or possibly even triggers, acute upper and lower airway responses in asthmatics. Again, the fact that atopic asthmatics can have an immune over-response to certain allergic triggers such as pollen and dust, and a lack of inflammatory response resolution due to a lack of IL-10 production in the airway, one could imagine that the irritant and oxidative properties of acrolein would amplify those effects, if acrolein exposure occurred in a sensitized and untreated, or undertreated asthmatic. Recent evidence collected in human cell cultures, in vitro, suggests that acrolein may act through non-canonical signaling pathways to exert its effects in the lung (Verstraelen et al., 2009), suggesting that further work is warranted in determining the nature of those pathways. Acrolein has also been reported to increase ROS generation and degranulation in mast cells (Hochman, Collaco, & Brooks, 2012), an important cell determining airway responses to allergic triggers (Krishnaswamy et al., 2001), which was moderated by administration of anti-oxidants (Hochman et al., 2012), suggesting yet another target of acrolein effects in the lung, and a possible therapeutic treatment for its effects. These interactions are likely complex, but all would seem to be pre-disposed toward positive synergism in the exacerbation of asthma.

4.2.2.2. Butadiene.

General Characteristics.

Butadiene, typically referring to the form of 1,3-butadiene, also known as divinyl, is a conjugated diene which exists as a 4-carbon chain, with two double bonds originating at the 1- and 3-carbons of the chain (i.e., between each of the distal carbons and the next most proximal carbon, moving toward the center of the molecule), and having a total of six hydrogen atoms bound to the carbons; hence, its formula as C4H6. As a gas, it has a faint odor similar to gasoline that is discernible by humans at approximately 1-2 ppm (Amoore & Hautala, 1983), just above the OSHA PEL (ATSDR, 1992), making it relatively easy to discern potential acute exposure without sophisticated measuring equipment. Butadiene is highly volatile and has a low water solubility, and when exposed to sunlight, butadiene gas degrades with a half-life of under 2 hours (ACC, 1992). Historically, synthesis of butadiene polymers in massive quantities began just prior to World War II, in which they were used in the manufacture of tires for war vehicles and other rubber-based products (Herbert V., 1985). This has continued through today, e.g., polybutadiene, a polymerized form, and styrene butadiene, a combination of styrene and butadiene, account for a major amount of the material in car tires currently manufactured, worldwide. Exhaust from gasoline-powered motor vehicles is a major source of butadiene in the external environment, whereas cigarette smoke is considered to be a major source of butadiene in the internal environment (ATSDR, 1992). Also, with the burning of car tires, there are release of significant amounts of butadienes into the atmosphere (EPA, 1997), which could pose problems for people living near scrap tire piles throughout the United States, and particularly those that run along the United States/Mexico border (EPA, 2010b), in the case that uncontrollable fires were to erupt at those locations.

Butadiene as a Hazardous Compound.

Butadiene typically exists as a colorless gas, which has importance for its potential as an inhaled toxicant because it cannot be seen, but it also has the dangerous characteristic of being highly flammable (ATSDR, 1992), and is therefore a compound of concern regarding general safety. It is known to be self-reactive (CDC, 1992) and form polymers over time when stored in cylinders, which can subsequently rupture the cylinder and result in the release of butadiene gas into the environment, which can be problematic for the induction of acute inhaled toxic effects. Butadiene is listed by the EPA as a carcinogen and is also suspected to be a human teratogen, based on numerous studies, mainly in animals (EPA, 2009). Similar to acrolein, definitive experimental and mechanistic data regarding the effects of butadiene in humans is relatively scant, due to its known acute toxicities. For example, acute butadiene exposure is known to cause mucous membrane irritation, typically at levels > 10,000 ppm (CDC, 1992; CGA, 1999), but there are no experimental studies of chronic exposure of toxic levels in humans.

Butadiene as a Factor in Airway Dysfunction.

While butadiene gas is considered by some to have low inhalation toxicity (CGA, 1999); its main route of exposure is through inhalation, and its main effect when inhaled is to produce sinus and mucus membrane irritation of the upper respiratory tract (Cralley L.J., 1985). Furthermore, treatment recommendations for acute butadiene exposure in children who develop stridor call for administration of beta agonist aerosol, to dilate the airways and relieve difficulty breathing (ATSDR, 1992). As a mucous membrane irritant, it would stand to reason that chronic low levels of inhaled butadiene could produce persistent effects such as irritation of sinuses and sore throat, but might be mistaken for common cold or allergy symptoms. However, little is known about airway effects with low level, chronic exposures in humans, particularly in those with chronic airways disease.

Butadiene as a phenotype shaper or interactor?

Under such conditions that an asthmatic might inhale butadiene, it would be expected that butadiene exposure would amplify true allergic symptoms, such that atopic asthmatics could be prone to enhanced sensitivities to common allergen triggers, which could precipitate asthma exacerbations or attacks. The exposure of children to inhaled butadiene, particularly those with asthma, is of some greater concern, as it is thought that they may receive larger doses than adults for a given environmental concentration, due to children having higher surface area:body weight ratios, and greater minute volume:body weight ratios, as compared to adults (ATSDR, 1992). This idea has been supported by a singular epidemiologic study by Delfino, et al., (Delfino, Gong, Linn, Pellizzari, & Hu, 2003), in which air samples positive for butadiene were associated with adverse effects on asthma in children.

Overall, the evidence for butadiene gas suggests that it is mainly an asthma interactor, serving to exacerbate asthma symptoms, mainly through irritation of sinus membranes and airways. There is not yet enough long-term evidence to determine whether butadiene gas induces an asthma phenotype, as few studies exist in this area. Additionally, unlike the case for SO2, as presented above, wherein effects on the airways can occur at levels beneath the odor detectability threshold, the acute toxicities for butadiene are mainly considered to be transient and avoidable, because the odor threshold is at, or beneath, the level at which toxic and irritant effects have been shown to occur.

4.3. Particulate Environmental Pollutant Triggers: Phenotype Shapers or Interactors?

4.3.1. Tire Breakdown Particles

General Characteristics.

It has been estimated that over 80% of respirable particulate matter (typically PM10 ; particles with a mean aerodynamic diameter of 10 μM or less) in urban areas comes from activities associated with motor vehicle transportation (Gualtieri, Andrioletti, Mantecca, Vismara, & Camatini, 2005). Tire breakdown particles, or tire wear debris, have been shown to accumulate in significant amounts near highways and urban high-traffic areas where motor vehicles travel, and it has been pointed out that the smallest-sized particles can be transported over relatively large distances of 18-30 meters from the roadway (Wik & Dave, 2009). Reports have indicated that a typical tire loses approximately 30% of its rubber tread over its lifetime, and that up to 5% of the resultant tire particulates are airborne, achieving particularly high concentrations in tunnels (Dannis, 1974; Pierson & Brachaczek, 1974; Saito, 1989). The agents within tire breakdown particles that may have significant respiratory health effects include butadienes and other VOCs, latex, as well as some heavy metals, such as zinc (Adachi & Tainosho, 2004).

Tire Breakdown Particles as a Hazardous Compound.

The hazardous aspects of tire breakdown particles mainly relate to the known toxicities of their components. Thus, the health effects of butadiene, as outlined above, would be among those to be considered for tire breakdown particles, as well as those of other volatile organic compounds (VOCs) contained within them, such as benzothiazole and n-hexadecane (Brown, 2007; Ginsberg, Toal, & Kurland, 2011). While typically considered toxic in their volatilized gaseous forms, emerging evidence suggests that the presence of VOCs in the form of inhaled particulates may be of some greater concern than previously thought (Brown, 2007). For example, experiments in vitro with application of organic extracts of tire debris have been shown to increase cell mortality, DNA damage, and production of reactive oxygen species in A549 human alveolar epithelial cells (Gualtieri, Mantecca, Cetta, & Camatini, 2008; Gualtieri, Rigamonti, Galeotti, & Camatini, 2005). Furthermore, animal studies have suggested the potential that zinc contained within tire wear products can exert cytotoxic effects (Gerlofs-Nijland et al., 2007).

Tire Breakdown Particles as a Factor in Airway Dysfunction.

As mentioned above, butadiene would be one potentially toxic chemical agent within tire breakdown particles that might produce airway dysfunction, through its irritant effects on sinus membranes and lower airways, which may promote the formation of mucus and subsequent bronchospasm, and difficulties breathing. However, in recent years, latex has been considered to be a potentially important agent within tire breakdown particles that may induce an allergic response within the airways that could promote airway dysfunction. While relatively inert in terms of chemical toxicity, latex is known to promote allergic reactions on the skin of individuals sensitive to it (Hamann, 1993), and the latex protein has been shown to share immunologic cross-reactivity with mountain cedar and cypress pollen (Caimmi et al., 2012; Miguel, Cass, Weiss, & Glovsky, 1996). It has been further postulated that latex may also be an important protein allergen that can induce allergic responses within the airway (Eghari-Sabet, 1993), and that there may be similarities between skin and airway sensitivities. Since the typical particulate size distribution of tire debris has been shown to range from 2.2 – 35.2 μm, with an average of 6-7 μm (Williams et al., 1995), tire dust in the smaller size range would be easily inhalable by humans, and could reach relatively far into the airways, especially if inspired by mouth. This has practical ramifications in heavily urbanized areas such as Los Angeles, in which over 5 tons of rubber particulate < 10 μm were typically released into the air, on a daily basis (Cass, 1982).

Tire Breakdown Particles as a phenotype shaper or interactor?

Given the demonstration of significant amounts of tire debris particulates in the air, there has been concern that such inhaled particulates could be of relevance to asthma (Glovsky, Miguel, & Cass, 1997), particularly for individuals living near high traffic areas (Dockery et al., 1993), i.e., that car tire particulates may contribute to the development of the asthma phenotype, potentially due to its role in the increasing numbers of asthma morbidity, mortality, and diagnoses over the past quarter century. In this case, tire breakdown particles could be potentially considered as asthma phenotype shapers, from the perspective of long-term exposure to the compounds that make up those particles. More recent epidemiological studies have suggested that asthma can be worsened by increases in levels of PM10 (Donaldson, Gilmour, & MacNee, 2000), but also that anti-oxidants such as vitamin C and E may mitigate these effects (Canova et al., 2012), in the short term.

However, with the evidence regarding latex acting similar to an allergic trigger, one could also make the argument that small latex particles may act to exacerbate allergic asthma, and thus tire breakdown particles could be considered as interactors with the established disease of atopic origin. Interestingly, this would also be expected to hold true for the use of tire “crumbs” on synthetic turf surfaces used for sports, as those larger particles will eventually breakdown with use and wear, resulting in finer dust-like particulates that can be inhaled by athletes and associated athletic personnel (Brown, 2007). Furthermore, this acute mechanism would also apply to the use of tire crumbs now commonly used in children’s playgrounds (Brown, 2007). In all, the use of these products should be monitored to determine whether these potential health risks develop, as synthetic turf and playground pads have become the norm in recent years.

4.3.2. Diesel Exhaust Particles

General Characteristics.

While tire breakdown particles constitute a significant portion of PM10 particulate load in the environment, diesel exhaust particles (DEP) constitute a significant portion of the PM2.5 particulate load in the environment (particles with a mean aerodynamic diameter of 2.5 μM or less) (Wichmann, 2007). These are considered to be fine particles, and as such, may pose an even greater risk to health, in part due to the ease, associated with their small size, with which they can be deposited in the smaller airways, and in part due to other toxicants that can be bound to them. However, it is also worth noting that a significant portion of DEP also comprises ultra-fine particles, which are in the PM0.1 range (particles with a mean aerodynamic diameter of 0.1 μM or less) (Saiyasitpanich, Keener, Lu, Khang, & Evans, 2006), which are beyond visual resolution of the naked eye, and can be deposited all the way down to the alveoli.

Diesel exhaust particles as a Hazardous Compound.

Similar to tire breakdown particles, the hazardous aspects of DEP mainly relate to the known toxicities of their components, and other toxicants complexed onto them. These components include: acrolein, butadiene, sulfur dioxide, and heavy metals, among others; essentially all of the environmental toxicants described above, as promoting and/or exacerbating the asthma phenotype. Based on a number of epidemiologic studies, DEP are conventionally considered to promote lung cancer (Wichmann, 2007), although this concept has been disputed (Hesterberg et al., 2006), and may be lessened in the years to come, with the adoption of new-technology diesel exhaust (NTDE) engines, which utilize low-sulfur fuel and exhaust after-treatment, such as particulate filters (Gerlofs-Nijland et al., 2007; Hesterberg et al., 2006). However, there are many older technology diesel engines still in use in the United States and elsewhere; therefore, from present, it will possibly take another decade or two before this transition becomes more complete with vehicle fleet turnover (Blanchard, Hidy, Tanenbaum, Edgerton, & Hartsell, 2013), and will likely lag in time, in developing countries.

Diesel Exhaust Particles as a Factor in Airway Dysfunction.

Initial experimental studies in humans under controlled conditions demonstrated that 1-hour of inhalation of diesel exhaust increased trafficking leukocytes in BAL fluid, indicating an airways inflammatory response (Rudell, 1990). As pointed out by Salvi and Holgate (Salvi & Holgate, 1999), early changes that herald the beginnings of the inflammatory process, as assessed in human-relevant animal models such as guinea pigs, have been shown to occur with diesel exhaust producing eosinophilic infiltration into the nasal airway epithelium and subepithelium (Kobayashi, 2000). Those findings are consistent with more recent in vitro studies in human bronchial epithelial (BEAS-2B) and human small airway epithelial (SAECs) cells, which have indicated that DEP can components can lead to release of inflammatory cell markers and cell death (Schwarze et al., 2013). In fact, ultra-fine particles have been reported to induce pro-inflammatory mechanisms and oxidative stress in in vivo animal models, but it is worth noting that a number of those data were obtained form study of surrogate particles (e.g., carbon black), rather than ultrafine DEP, themselves (Donaldson & Stone, 2003) and that the exact causal relationship between DEP and the development of diseases such as lung cancer and asthma have not yet been established (Hesterberg et al., 2006). The relatively large surface area of DEP is considered to be a major factor (Donaldson & Stone, 2003; Salvi & Holgate, 1999; Wichmann, 2007), but the precise relationship remains unclear, and requires further research.

Diesel Exhaust Particles as a Phenotype Shaper or Interactor?

Due to their irregular shape and relatively large surface area, DEP can pick up pollen and other allergenic agents, e.g., grass pollen allergen Lol p 1 (Knox et al., 1997), potentially making it a double-hit, or possibly even a triple-hit threat, where the asthma phenotype is concerned. Intranasal co-administration of DEP with allergen in atopic rhinitic humans resulted in a 50-fold increase in allergen-specific IgE (Diaz-Sanchez, Tsien, Fleming, & Saxon, 1997), supporting this concept. There is evidence in animal models that are likewise supportive of this concept (G. B. Lee et al., 2013), and it has been pointed out that a number of studies suggest that DEP are associated with induction of the early and late phases of the inflammatory response in asthma (Pandya, Solomon, Kinner, & Balmes, 2002). Thus, diesel exhaust mitigations such as particulate filters could conceivable lessen the impact of allergic factors on inhaled DEP. Even so, it seems apparent that DEP can be considered to be asthma phenotype interactors, from the perspective of the combined nature of particulate/surface area effects, complexed volatile toxicants, and attached allergens, that make up the totality of the DEP that might be typically inhaled by a person in the environment. In this way, DEP could be considered the perfect storm of deep lung administration of environmental factors that can interact and exacerbate existing asthma.

However, some results of mouse studies (Hougaard et al., 2008) suggest that it is conceivable that with prolonged, and possibly early lifetime, or perhaps in-utero exposure, that DEP may promote early disposition to inflammatory effects at the molecular and cellular level, which can be considered precursors to later adverse respiratory health outcomes (Ristovski et al., 2012). For example, epigenetic modifications can occur with repeated exposures to environmental agents, both allergenic and toxicant, over time, that may be important in determining the risk and health outcomes of individuals (Ho et al., 2012), and subsequently have a strong impact on their disease phenotype. In this way, DEP could also possibly be considered as asthma phenotype shapers, if exposure is chronic and life-long.

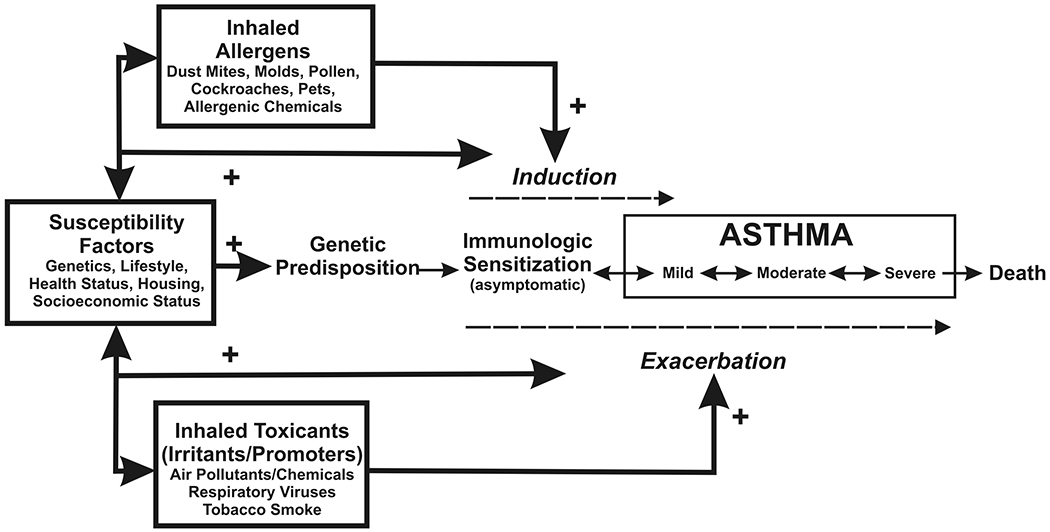

4.4. Summary

In summary, both allergic and non-allergic/toxicant factors can interact to acutely exacerbate the asthma phenotype; some may also promote its development over prolonged periods of untreated exposure. These interactions can include double- and triple-hit combinations such as allergen + toxicant + particulate effects, which may at least be additive, or could possibly be synergistic, producing profound exacerbations. Figure 2 illustrates this potential, within a continuum of asthma development, induction, and exacerbation.

Figure 4.2: Factors involved in induction and exacerbation of asthma.

Induction of asthma may occur in genetically susceptible people upon exposure to common allergens or certain chemicals. Nonspecific irritants and promoters may facilitate induction through injury and increased uptake of allergens or by modulating immune responses (dashed arrow). Both allergens and irritants may exacerbate existing asthma. Inflammation and airway obstruction in asthma are reversible. Consequently, severity of the disease is variable (double-headed arrows), depending on environmental influences as well as susceptibility factors as indicated here. Used by permission; from US EPA, ref 33.

However, of more recent consideration, is the possibility that allergen exposures and toxicants (i.e., irritants, promoters in Figure 4.2) may have direct effects on the genome, which may shape the asthma phenotype and increase susceptibility to the subsequent induction and development of asthma, along the continuum of mild to severe. Furthermore, as mentioned above, there may also be cross-reactivities that may be genetically promoted, which might need to be accounted for, in the determination of treatment options for asthma, in the future. Further research is necessary to better delineate and understand the effects of combined environmental allergens and toxicants on the determination of the asthma phenotype.

REFERENCES

- Abraham K, Andres S, Palavinskas R, Berg K, Appel KE, & Lampen A (2011). Toxicology and risk assessment of acrolein in food. Mol Nutr Food Res, 55(9), 1277–1290. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201100481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ACC. (1992). Butadiene Product Summary. Products and Technology. from http://www.americanchemistry.com/butadiene [Google Scholar]

- Adachi K, & Tainosho Y (2004). Characterization of heavy metal particles embedded in tire dust. Environment International, 30(8), 1009–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2004.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoore JE, & Hautala E (1983). Odor as an aid to chemical safety: odor thresholds compared with threshold limit values and volatilities for 214 industrial chemicals in air and water dilution. J Appl Toxicol, 3(6), 272–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AQMD. (2013). Ozone, 1976-2012. Historic Air Quality Trends. from http://www.aqmd.gov/smog/o3trend.html [Google Scholar]

- Arbes SJ Jr., Gergen PJ, Elliott L, & Zeldin DC (2005). Prevalences of positive skin test responses to 10 common allergens in the US population: results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 116(2), 377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arntz D, Fischer A, Höpp M, Jacobi S, Sauer J, Ohara T, Sato T, Shimizu N, Schwind H . (2007). Acrolein and Methacrolein Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. GmbH: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. [Google Scholar]

- ATSDR. (1992). Toxicological Profile for 1,3-Butadiene. Atlanta, GA: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Aubier M, Neukirch C, Peiffer C, & Melac M (2001). Effect of cetirizine on bronchial hyperresponsiveness in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis and asthma. Allergy, 56(1), 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bacsi A, Dharajiya N, Choudhury BK, Sur S, & Boldogh I (2005). Effect of pollen-mediated oxidative stress on immediate hypersensitivity reactions and late-phase inflammation in allergic conjunctivitis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 116(4), 836–843. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bein K, & Leikauf GD (2011). Acrolein - a pulmonary hazard. Mol Nutr Food Res, 55(9), 1342–1360. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201100279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaisdell CJ, Weiss SR, Kimes DS, Levine ER, Myers M, Timmins S, & Bollinger ME (2002). Using seasonal variations in asthma hospitalizations in children to predict hospitalization frequency. J Asthma, 39(7), 567–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard CL, Hidy GM, Tanenbaum S, Edgerton ES, & Hartsell BE (2013). The Southeastern Aerosol Research and Characterization (SEARCH) study: temporal trends in gas and PM concentrations and composition, 1999-2010. J Air Waste Manag Assoc, 63(3), 247–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borish L, Aarons A, Rumbyrt J, Cvietusa P, Negri J, & Wenzel S (1996). Interleukin-10 regulation in normal subjects and patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 97, 1288–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DR (2007). Artificial Turf: Exposures to Ground Up Rubber Tires-Athletic Fields, Playgrounds, Garden Mulch. In Alderman N. AS, Bradley J (Ed.), (pp. 36). North Haven, CT. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant DH, Burns MW, & Lazarus L (1975). The correlation between skin tests, bronchial provocation tests and the serum level of IgE specific for common allergens in patients with asthma. Clin Allergy, 5(2), 145–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley JP, & Richardson DB (2012). Seasonal modification of the association between temperature and adult emergency department visits for asthma: a case-crossover study. Environ Health, 11, 55. doi: 10.1186/1476-069x-11-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett RT, Dales RE, Raizenne ME, Krewski D, Summers PW, Roberts GR, … Brook J (1994). Effects of low ambient levels of ozone and sulfates on the frequency of respiratory admissions to Ontario hospitals. Environ Res, 65(2), 172–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows B, Martinez FD, Halonen M, Barbee RA, & Cline MG (1989). Association of asthma with serum IgE levels and skin-test reactivity to allergens. N Engl J Med, 320(5), 271–277. doi: 10.1056/nejm198902023200502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai C, Xu J, Zhang M, Chen XD, Li L, Wu J, … Zhong NS (2008). Prior SO2 exposure promotes airway inflammation and subepithelial fibrosis following repeated ovalbumin challenge. Clin Exp Allergy, 38(10), 1680–1687. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03053.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caimmi D, Raschetti R, Pons P, Dhivert-Donnadieu H, Bousquet J, & Demoly P (2012). Cross-reactivity between cypress pollen and latex assessed using skin tests. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol, 22(7), 525–526. [Google Scholar]

- Canova C, Dunster C, Kelly FJ, Minelli C, Shah PL, Caneja C, … Burney P (2012). PM10-induced hospital admissions for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the modifying effect of individual characteristics. Epidemiology, 23(4), 607–615. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182572563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass GR, Boone PM, Macias ES (1982). Emissions and air quality relationships for atmospheric carbon particles in Los Angeles. In Wolff T, Klimisch RL (Ed.), Particulate carbon-atmospheric life cycle (pp. 207–240). New York, NY: Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (1992). Occupational Safety and Health Guideline for Butadiene (1,3-butadiene). from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/81-123/pdfs/0067-rev.pdf

- CDC. (1994a). Documentation for Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLHs): Acrolein. NIOSH Publications and Products. from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2005-149/pdfs/2005-149.pdf [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (1994b). Documentation for Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLHs): Ozone. NIOSH Publications and Products. from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/idlh/10028156.html [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (1995). Documentation for Immediately Dangerous To Life or Health Concentrations (IDLHs): Chemical Listing and Documentation of Revised IDLH Values. NIOSH Publications and Products. from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/idlh/intridl4.html [Google Scholar]

- CGA. (1999). Handbook of Compressed Gases: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Xirasagar S, & Lin HC (2006). Seasonality in adult asthma admissions, air pollutant levels, and climate: a population-based study. J Asthma, 43(4), 287–292. doi: 10.1080/02770900600622935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodaczek G, Bacsi A, Dharajiya N, Sur S, Hazra TK, & Boldogh I (2009). Ragweed pollen-mediated IgE-independent release of biogenic amines from mast cells via induction of mitochondrial dysfunction. Mol Immunol, 46(13), 2505–2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cralley LJ, C. LV (1985). Patty’s industrial hygiene and toxicology (2nd ed. Vol. 3). New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Csillag A, Boldogh I, Pazmandi K, Magyarics Z, Gogolak P, Sur S, … Bacsi A (2010). Pollen-induced oxidative stress influences both innate and adaptive immune responses via altering dendritic cell functions. J Immunol, 184(5), 2377–2385. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Gao CQ, Sun G, Zhou Y, Qu F, Tang C, … Guan C (2011). L-arginine promotes DNA repair in cultured bronchial epithelial cells exposed to ozone: involvement of the ATM pathway. Cell Biol Int, 35(3), 273–280. doi: 10.1042/cbi20090252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato G, Liccardi G, D’Amato M, & Cazzola M (2002). Respiratory allergic diseases induced by outdoor air pollution in urban areas. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis, 57(3-4), 161–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]