Abstract

Efficient sensory processing is a complex and important function for species survival. As such, sensory circuits are highly organized to facilitate rapid detection of salient stimuli and initiate motor responses. For decades, the retina’s projections to image-forming centers have served as useful models to elucidate the mechanisms by which such exquisite circuitry is wired. In this chapter, we review the roles of molecular cues, neuronal activity, and axon-axon competition in the development of topographically ordered retinal ganglion cell (RGC) projections to the superior colliculus (SC) and dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN). Further, we discuss our current state of understanding regarding the laminar-specific targeting of subclasses of RGCs in the SC and its homolog, the optic tectum (OT). Finally, we cover recent studies examining the alignment of projections from primary visual cortex with RGCs that monitor the same region of space in the SC.

1. Introduction

Neurons in the visual system are connected in well-ordered arrays, allowing for efficient processing, modulation of information flow, and guiding behavioral responses. As such, this exquisite organization has served as an ideal model to understand the mechanisms underlying circuit development, the principles of which have been repeated in multiple brain regions and systems. Specifically, the pattern of connectivity between retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) and their image-forming targets, the superior colliculus (SC) and dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN), have provided particularly rich insights. In these regions, RGC projections are organized topographically, such that the terminals of inputs reflect the order of their cell bodies, thereby retaining spatial information of the visual scene. In addition, inputs are organized laminarly, reflecting both eye-specific origins and functional subtypes. Finally, in both the SC and dLGN, feedback connections from the primary visual cortex (V1) are organized in alignment with RGC terminals monitoring the same region of visual space. The mechanisms underlying the establishment of eye-specific layers, especially in the dLGN and V1, are relatively well understood and have been covered elsewhere (Hensch & Quinlan, 2018; Murcia-Belmonte & Erskine, 2019). Thus, in this review, we will focus on recent advances in our understanding of the mechanisms of retinofugal topographic map formation, the establishment of functional laminar targeting, and the alignment of convergent V1 inputs with RGCs.

2. Mature organization of inputs in the SC and dLGN

As subcortical image-forming areas, both the SC and dLGN are organized topographically, such that the neighbor-neighbor relationships in the retina are maintained by their axon terminals in the target (Figs. 1A and 2A). RGCs project from a retina that can be divided along two Cartesian axes: temporal-nasal (T-N) and dorsal-ventral (D-V), which correspond to the azimuth (horizontal) and elevation (vertical) axes of the visual scene, respectively. The SC can similarly be divided such that the T-N and D-V retinal axes are mapped along the anterior-posterior (A-P) and lateral-medial (L-M) axes of the SC, respectively. Thus, a two-dimensional visual scene is projected intact onto the SC, excepting the notable observation of a slight magnification of central visual space, corresponding to the anterior SC (Drager & Hubel, 1975). The dLGN is a more condensed structure than the SC, and thus the retinal axes are not as cleanly projected along two axes. Roughly, the T-N retinal axis project along the posterodorsomedial-anteroventrolateral dLGN, while the D-V retinal axis is found along the posteroventral-anterodorsal axis.

Fig. 1.

Organization of subcortical image-forming circuits. Retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) send axons along the optic tract and terminate in multiple retinorecipient regions. In image-forming centers, the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN) and superior colliculus (SC), RGC terminations are organized topographically. (A) RGCs axons course along the optic tract on the dorsolateral side of the dLGN. Those terminating in the dLGN innervate into topographically appropriate regions, indicated by correlating colors. As RGC axons pass the dLGN, they begin to turn posteriorly and innervate the SC at in the stratum opticum (SO), ventral to their terminal located in the stratum griseum superficiale (SGS). (B) In addition to topography, RGCs are organized into parallel circuits, such that distinct subclasses of RGCs terminate in different sublaminae of the dLGN and SC. In each region, two broad termination strata have been identified: the core and shell in the dLGN, as well as the upper and lower SGS (uSGS, lSGS) in the SC. For simplicity, only two representative RGC subclasses are depicted here in yellow and maroon. (C) In addition to RGCs, both the dLGN and SC receive inputs from primary visual cortex (V1). The dLGN is primarily innervated by neurons from layer 6 (L6), while the SC receives L5 inputs. In each case, V1 projections terminate in topographic alignment with RGCs monitoring the same region of visual space, as depicted by correlating colors. D, dorsal; N, nasal; V, ventral; T, temporal; A, anterior; P, posterior.

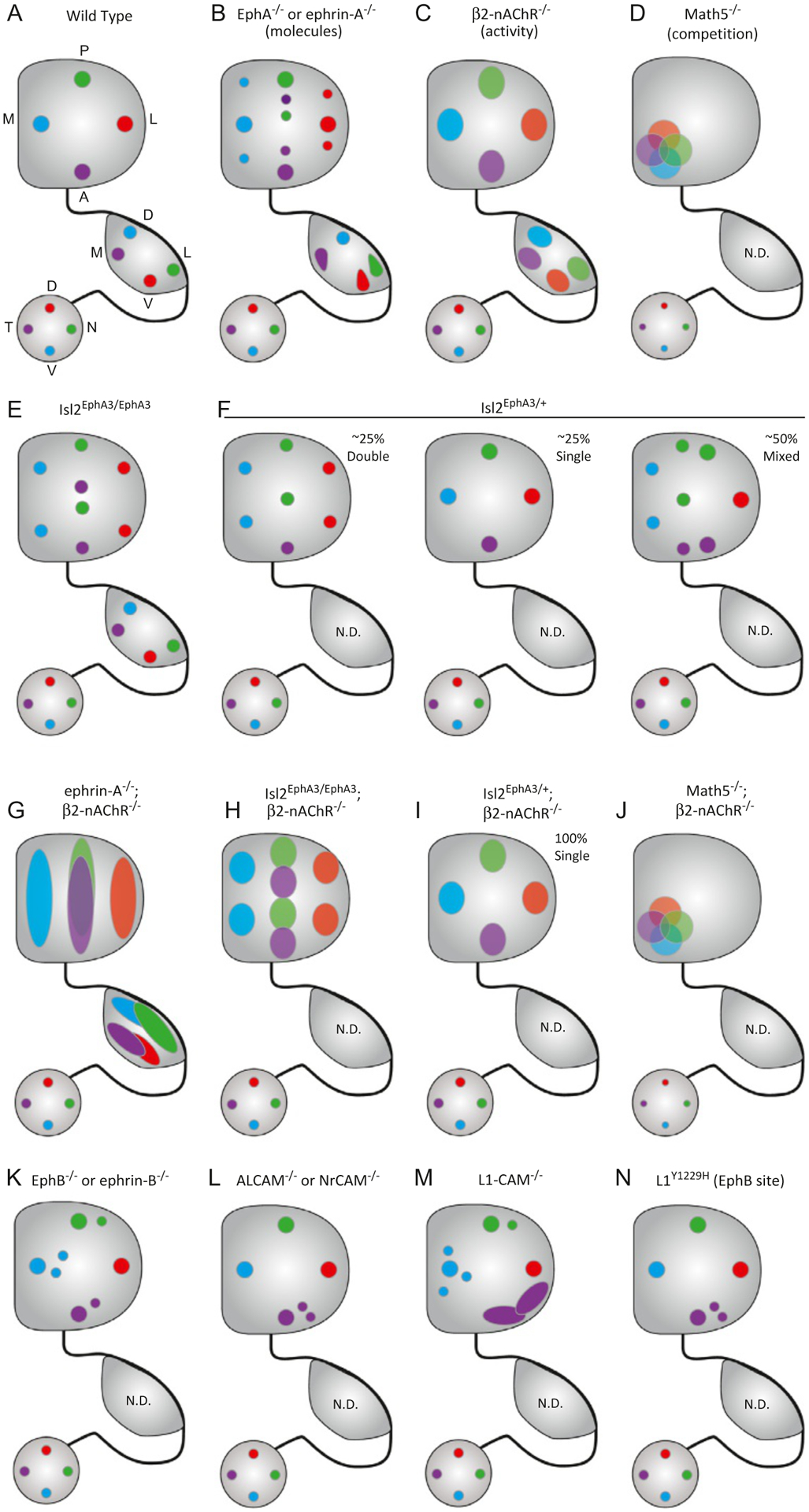

Fig. 2.

Summary of genetic manipulations that result in topographic mapping errors. (A) In wild type mice, the temporal-nasal (T-N) axis of the retina projects along the lateral-medial (L-M) axis of the dLGN and the anterior-posterior (A-P) axis of the SC, while the dorsal-ventral (D-V) axis of the retina projects along the V-D axis of the dLGN and the L-M axis of the SC. (B) In mice lacking ephrin-A or EphA expression in both the retina and SC, ectopic termination zones (TZs) are observed along the A-P axis of the SC, while subtle broadening and shifts of TZ location are observed in the dLGN. (B) In mice lacking the β2 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (β2-nAChR), Stage II retinal waves are disrupted and TZs in both dLGN and SC are roughly in the appropriate topographic zone, but poorly refined. (D) In Math5 knockout mice, only ~5–20% of the normal number of RGCs are present, reducing axonal competition. As a result, RGC terminals are clustered in the anteromedial portion of the SC and topography is disrupted. Effects on organization in the dLGN have not been determined (N.D.) in these mutants. (E) In homozygous Islet2-EphA3 knock-in mice (Isl2EphA3/EphA3), the retina’s projection is duplicated along the A-P axis of the SC, but no change is observed in the dLGN. (F) In heterozygous Isl2EphA3/+ mice, three different map organizations are observed: double (left), single (middle), and mixed (right). (G) In combination ephrin-A and β2-nAChR knockout mice, topographic order along the azimuth axes in both the dLGN and SC is completely lost. (H) When Stage II waves are disrupted in Isl2EphA3/EphA3 mice, the retinocollicular projection is duplicated along the A-P axis of the SC, but TZs are broader. (I) When Stage II waves are disrupted in Isl2EphA3/+ mice, heterogeneous map organizations are no longer observed. Instead, all maps appear single, though TZs are enlarged. (J) In combination Math5 and β2-nAChR knockout mice, RGCs remain clustered in the anteromedial SC. (K) Mutations in EphB or ephrin-B family members result in ectopic termination zones along the L-M axis of the SC. (L) Similarly, mutations in ALCAM and NrCAM drive disruptions along the L-M axis, though these tend to be concentrated in the anterior domain. (M) Deletion of L1-CAM results in dramatic disruptions in topography not restricted to either the A-P or L-M axis, with particularly large errors observed in anterolateral SC. (N) Deletion of a single EphB target site on L1-CAM results in errors only along the L-M axis, suggesting these molecules are in a linear pathway.

The SC and dLGN are comprised of sublaminae to which distinct subclasses of RGCs project their axons (Fig. 1B). The SC can be divided into multiple layers and sublayers along the D-V axis, where superficial layers process visual inputs and intermediate and lower layers mediate somatosenory, auditory, and motor functions (Ito & Feldheim, 2018). The superficial-most layer, the stratum griseum superficiale (SGS), receives retinal input and can be divided into upper and lower regions (uSGS, lSGS). Studies utilizing genetically-labeled RGCs revealed subtypes that terminate in each of these respective sublayers (Huberman et al., 2008, 2009; Kim, Zhang, Meister, & Sanes, 2010; Kim, Zhang, Yamagata, Meister, & Sanes, 2008; Siegert et al., 2009). Further, stochastic labeling of individual RGCs identified five “clusters” of RGC subclasses based on their terminal lamination pattern in the SC, suggesting that the uSGS and lSGS may be further subdivided (Hong, Kim, & Sanes, 2011). However, the precise localization of sublayers and their boundaries remains poorly defined in the mouse SC, a notable distinction from the zebrafish optic tectum (OT), where 10 synaptic laminae have been identified (Baier, 2013; Robles, Filosa, & Baier, 2013). Similarly, the sublayers targeted by RGC subclasses in the mouse dLGN are poorly defined compared to those in the ferret, cat, and monkey, where the high degree of stratification is apparent cytoarchitecturally. Thus far the mouse dLGN has been divided into “core” and “shell” regions, which receive inputs from distinct RGC subclasses and exhibit different functional properties (Seabrook, Burbridge, Crair, & Huberman, 2017).

In addition to RGCs, both the SC and dLGN receive feedback connections from visual cortex that play critical roles in both visual processing and execution of innate behaviors (Liang et al., 2015; Wang, Sarnaik, Rangarajan, Liu, & Cang, 2010). Neurons in Layer 5 (L5) of multiple visual cortical regions project to the SC (Wang & Burkhalter, 2013). Intriguingly, inputs from V1 and lateromedial area terminate in sublayers that overlap with retinal inputs (Fig. 1C), while those from other visual cortical areas terminate in more ventral (deep) sublayers. Importantly, the V1-SC projection is topographically organized and in register with the retinocollicular map. Similarly, the dLGN receives inputs from both L5 and L6 of V1, both of which are organized topographically and in alignment with retinal inputs and play critical roles in the development of proper connectivity in the thalamus (Hasse & Briggs, 2017).

3. Developmental timing of subcortical visual circuit wiring

The connectivity patterns of RGCs and V1 axons in the SC and dLGN are established in sequential, but overlapping, developmental windows. While we will discuss informative studies exploring the establishment of retinotectal connections in the fish, frogs, and chickens, we will focus on the mouse as a model organism to illustrate the timing of development. In both the dLGN and SC of mice, the bulk of retinal and cortical connections are established prior to eye opening (postnatal day 12–14 [P12–14]), though important experience-dependent processes are required for the maturation and maintenance of these connections (Hooks & Chen, 2020).

In the SC, RGC axons are the first to arrive, beginning as early as P0 and some precocious fibers appear embryonically (Triplett, 2014). Regardless of retinal origin location, the growth cones of all RGCs project to the posterior-most region of the SC. Following this, interstitial branches are dynamically formed and pruned at roughly topographically appropriate locations (Yates, Roskies, McLaughlin, & O’Leary, 2001). Over the first postnatal week, these branches eventually coalesce into a tightly packed terminal arbor, that is, positioned in the proper topographic location and within the appropriate sublamina of the SC. As the final refinement of retinocollicular axons is occurring, L5-V1 projections begin to innervate the SC, beginning at P6 (Triplett et al., 2009). Akin to RGCs, these axons go through a protracted period of branching and pruning, establishing adult-like topographic order and alignment with the retinal map by P12, just prior to eye opening. Importantly, development of L5-V1 connectivity is not entirely complete at this stage, as eye opening triggers a critical consolidation of synaptic inputs (Phillips et al., 2011).

Similar to the SC, the dLGN is first innervated by RGCs, which refine to a mature-like state by P8/9, and later by projections from V1, which refine during the second postnatal week. In contrast to the SC, as RGCs project into the dLGN, they do not appear to overshoot their future termination zone, but rather target it almost directly with minimal interstitial branching (Dhande et al., 2011). Intriguingly, while L6-V1 projections to the thalamus are observed at the ventromedial border of the dLGN as early as P2, they do not begin to innervate the dLGN until later (Seabrook, El-Danaf, Krahe, Fox, & Guido, 2013). This delay appears to be directed by RGCs, as L6-V1 axons precociously invade the dLGN in the absence of retinal input (Seabrook et al., 2013). In a peculiar twist to this mechanism, cortical input is required for proper RGC targeting to the dLGN (Shanks et al., 2016), suggesting highly orchestrated crosstalk between innervating axonal populations.

4. Mechanisms of retinofugal topographic map assembly

In the decades since Sperry’s initial experiments examining the regrowth of RGC axons into the frog tectum (Sperry, 1943, 1947, 1963), the field has made substantial advances towards understanding the intricacies of the forces driving the formation of topographic maps of space. In addition to the molecular cues that Sperry postulated in his chemoaffinity hypothesis, clear evidence of a role for spontaneous waves of retinal activity has emerged in the past two decades. Further, inter-axon interactions, such as competition, play a role in mapping. Finally, the concept that these forces do not operate in a vacuum, but rather interact and influence one another, has recently been investigated.

4.1. Molecular cues

In his chemoaffinity hypothesis, Sperry postulated that specific “chemical tags” expressed by RGCs and neurons in the OT served to ensure proper connectivity (Sperry, 1963). His hypothesis was refined to postulate that gradients of molecules might be expressed along the cardinal axes of the retina and OT. As molecular and genetic tools were developed in subsequent decades, evidence in support of a mechanism akin to Sperry’s truly insightful conclusion from his regeneration experiments has become “textbook” material.

4.1.1. Relative levels of repellant ephrin-A/EphA signals shape azimuth axis topography

The best demonstration of the influence of molecular gradients is in the mapping of the T-N axis of the retina onto the A-P axis of the SC/OT. There, counter-gradients of EphA receptor tyrosine kinases and their ligands, ephrin-As are found. The function of EphAs and ephrin-As has been reviewed in detail previously (Feldheim & O’Leary, 2010; Triplett & Feldheim, 2012), so we will briefly describe it here.

The clearest action of ephrin-A ligands expressed in the SC/OT is their role as repellant molecules. Elegant studies by the Boenhoffer lab leveraging the in vitro stripe assay demonstrated that temporal RGCs avoid posterior tectal membranes, an action mediated by a glycophosphoinosital (GPI)-linked protein (Walter, Henke-Fahle, & Bonhoeffer, 1987; Walter, Kern-Veits, Huf, Stolze, & Bonhoeffer, 1987). Subsequent work by many groups identified a family of GPI-linked molecules, later named ephrin-As, that are sufficient to replicate RGC avoidance results in the stripe assay and are expressed in high posterior to low anterior gradients in the SC/OT (Drescher et al., 1995). Intriguingly, these molecules are bound by a family of orphan receptor tyrosine kinases (Cheng & Flanagan, 1994; Cheng, Nakamoto, Bergemann, & Flanagan, 1995), later named EphAs, that are expressed in high temporal to low nasal gradients in the retina.

The expression patterns of ephrin-As in the SC/tectum and EphAs in the retina are consistent with a mass-action repellent model that could drive topographic mapping. That is, RGCs from the temporal retina express high levels of EphA, are most repelled by the ephrin-A gradient, and terminate anteriorly. As RGCs progressively nasal in position express less EphA, they are less repelled by the ephrin-A gradient and terminate progressively posteriorly. Experimental evidence in support of this model came via both gain- and loss-of-function experiments. Indeed, global deletion of the ephrin-As expressed in the SC/OT (ephrin-A2, ephrin-A3, and ephrin-A5 in mouse) alone or in combination leads to topographic guidance errors of RGCs projecting to the SC and dLGN, as assessed by anatomical tracing (Fig. 2B) (Feldheim et al., 2000, 1998; Frisén et al., 1998; Pfeiffenberger, Yamada, & Feldheim, 2006). Further, deletion of EphA5, expressed in a gradient in the retina, phenocopies ephrin-A knockout experiments (Feldheim et al., 2004). Over-expression of ephrin-A3 sporadically in the tectum results in RGCs avoiding these areas, suggesting sufficiency for repellant action (Nakamoto et al., 1996).

Further studies suggest that the sum of ephrin-A/EphA signaling, rather than the action of specific molecules, results in topographic order. In Islet2-EphA3 knock-in mice (Isl2EA3), the EphA3 receptor is expressed by Isl2+ RGCs, which represent ~40–50% of all RGCs and are scattered across the retina in a salt-and-pepper fashion (Brown et al., 2000). Amazingly, in homozygous Isl2EA3/EA3 mice, the retinocollicular map is duplicated both anatomically and physiologically along the azimuth axis (Fig. 2E) (Brown et al., 2000; Triplett et al., 2009). Since EphA3 is not normally expressed by RGCs, these findings suggest that the relative level of ephrin-A/EphA signaling shapes topography. Later computational modeling and combination knockout mouse models support this relative signaling mechanism (Bevins, Lemke, & Reber, 2011; Reber, Burrola, & Lemke, 2004). However, recent findings suggest a complicated interplay between ephrin-A/EphAs and other forces that was revealed in heterozygous Isl2EA3/+ mice (Owens, Feldheim, Stryker, & Triplett, 2015), which we will discuss in detail below.

4.1.2. Mapping nasal axons: Reverse signaling and dual functionality

The ephrin-A/EphA repellant model of retinofugal topographic mapping raises a potential paradox: how are nasal neurons guided to terminate in the most repellant regions of the gradient? Three putative mechanisms to achieve innervation in ephrin-A rich areas have been put forth: (1) inter-axon competition for synaptic territory, (2) EphA-mediated repulsion, and (3) ephrin-A attraction. Here, we will focus on the latter two, as we will discuss competition in more detail later. In addition, we will discuss how recent findings affect our interpretation of these models and, potentially, uncover a novel ephrin-A/EphA-mediated mechanism.

The hypothesis that EphAs may function as repulsive cues in the guidance of RGC axons stems from their complementary expression patterns in both the retina and target structures and their ability to initiate signaling in the “reverse” direction (Triplett & Feldheim, 2012). Signaling through the ephrin-A/EphA complex is propagated in two directions: “forward” into the EphA-bearing cell and “reverse” into the ephrin-A-bearing cell. Support for activation of reverse signaling in retinofugal map formation stems from both loss- and gain-of-function experiments. Deletion of EphA7, which is expressed in a high anterior to low posterior gradient in the SC (but not in the retina), results in topographic guidance errors, suggesting an active role for collicular EphAs (Rashid et al., 2005). Further, guidance errors induced by over-expression of a constitutively-active EphA6 in RGCs are prevented by co-expression of ephrin-A5, suggesting reverse signaling may provide at minimum a counterbalancing force (Carreres et al., 2011). Curiously, ephrin-As are membrane attached and do not have an intracellular domain, so the mechanism by which reverse signaling occurs likely involves co-receptors. The neurotrophin receptors p75 and TrkB can interact with ephrin-As and have been suggested to act as co-receptors that mediate reverse signaling (Lim et al., 2008; Marler, Poopalasundaram, Broom, Wentzel, & Drescher, 2010; Poopalasundaram, Marler, & Drescher, 2011). Further, each is capable of modulating EphA/ephrin-A mediated guidance events such as terminal positioning in the posterior SC or interstitial branching. However, effects on overall topography are not as robust as global ephrin-A/EphA knockouts, raising the possibility that further co-receptors remain to be identified.

In other systems, ephrin-A/EphA interactions drive cell adhesion and axon tracking, raising the possibility that similar functions could be elicited in the formation of topographic maps by RGCs. Indeed, explant assays suggest that exogenous ephrin-A has differential effects on axon outgrowth depending on the location of explant origin (Hansen, Dallal, & Flanagan, 2004). As expected, high levels of ephrin-A inhibits outgrowth regardless of location, but moderate levels have a surprisingly growth-promoting effect on explants from nasal retina. Thus, under the right conditions in vivo nasal axons could be attracted, or at least exhibit increased growth, in the presence of high levels of ephrin-A. Alternatively, recent studies of growth cone responses of lateral motor column neurons suggest that ephrin-A5 enhances attraction to netrin-1, despite its known role as a repulsive cue (Croteau, Kao, & Kania, 2019; Poliak et al., 2015). These results raise the intriguing possibility that in the context of topographic mapping, ephrin-As may facilitate attraction via another as yet unidentified molecular cue.

The dissection of how ephrin-A/EphA interactions between RGCs and SC neurons was recently extended using a conditional knockout approach, which yielded surprising results that add a new understanding to how these molecules shape topography (Suetterlin & Drescher, 2014). In contrast to expectations derived from the EphA repellant model, deletion of ephrin-A5 specifically from RGCs does not result in dramatic disruptions in topography, particularly of nasal axons. Intriguingly, SC-specific deletion of ephrin-A5 does not alter the projection pattern of RGCs originating from temporal or central retina. However, when ephrin-A5 was conditionally-deleted from both retina and SC, topographic mapping errors were observed in all RGC populations, similar to global knockouts. These data suggest that axon-axon interactions mediated via ephrin-A5 play a critical role in mapping. Indeed, in vitro assays suggest that nasal axons (which express high levels of ephrin-As) can repel temporal RGCs. This target-independent function of ephrin-A5 represents a novel mechanism of action in the retinofugal system, though similar roles have been reported in other systems. Additionally, this study found that SC-specific deletion of ephrin-A5 results in topographic mapping errors by nasal RGCs, which may support an attractive role for ephrin-As on this population.

4.1.3. Diverse signaling pathways shape topography of the elevation axis

While ephrin-A/EphA signaling is a clear molecular driver of topographic order along the azimuth axis, a more diverse set of molecular pathways appears to influence mapping along the elevation axis. Interestingly, much of the topographic order along this axis, especially in the retina’s projection to the SC/OT, is established prior to entering the target (Plas, Lopez, & Crair, 2005; Simon & O’Leary, 1991). Thus, many of the molecular regulators of mapping regulate the extent of interstitial branching along either side of the RGC axon, which ultimately dictates topographic order.

To begin, akin to the graded expression of EphAs/ephrin-As along the T-N and A-P axes, gradients of molecular cues have been described along the orthogonal axes. Indeed, the B-class of Ephs are expressed in a high ventral to low dorsal gradient in the retina, while their ligands, the ephrin-Bs are expressed in a high medial to low lateral gradient in the SC/OT (Braisted et al., 1997; Higenell, Han, Feldheim, Scalia, & Ruthazer, 2012; Holash et al., 1997). In contrast to the azimuth axis, these molecules primarily exert an attractive force, which shapes topography appropriately. In support of this, deletion of EphBs results in ectopic terminations lateral to the topographically appropriate region (Hindges, McLaughlin, Genoud, Henkemeyer, & O’Leary, 2002) (Fig. 2K). However, it should be noted that ectopic expression of ephrin-B1 appears to inhibit terminal stabilization (Mclaughlin, Hindges, Yates, & O’Leary, 2003; Thakar, Chenaux, & Henkemeyer, 2011), raising the possibility that these molecules may signal in a more complex manner, akin to their A-class family members.

Similar to EphBs/ephrin-Bs, molecules in the Wnt signaling pathway are expressed in gradients along the elevation axes and play a role in topographic mapping (Schmitt et al., 2005). Indeed, Wnt3 is expressed in a high medial to low lateral gradient in the SC, while one of its receptors, Ryk, is expressed in a high ventral to low dorsal gradient in the retina. Intriguingly, explant assays suggest that Wnt3 promotes the outgrowth of dorsal RGCs, while inhibiting and even repelling ventral RGCs. Thus, these signals may serve to counter-balance attractive/repulsive cues generated by ephrin-B/EphB signals. However, whether these signals converge on the same intracellular pathways remains unclear.

Finally, members of the immunoglobulin superfamily of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) play critical roles in topographic mapping (Fig. 2L–N). First, anatomical tracing experiments in global knockout mice indicate that the L1 CAM is required for multiple aspects of RGC targeting, including sorting at the optic chiasm (Sretevan, Feng, Puré, & Reichardt, 1994), innervation of the SC, and topographic mapping (Demyanenko & Maness, 2003). Topographic targeting errors are observed along both the A-P and L-M axes of the SC, consistent with the uniform expression of L1 in both the retina and SC (Buhusi, Schlatter, Demyanenko, Thresher, & Maness, 2008; Demyanenko & Maness, 2003). Interestingly, similar experiments in knock-in mice harboring a targeted mutation of a tyrosine residue phosphorylated by EphB (L1Y1229H) reveal topographic mapping errors specifically along the L-M axis of the SC, suggesting that L1 is a critical mediator of ephrin-B/EphB mediated guidance (Dai et al., 2012). Next, a related molecule, activated leukocyte CAM (ALCAM), is a binding partner of L1 expressed in overlapping patterns in the retinocollicular pathway. Deletion of ALCAM results in topographic mapping errors that phenocopy those observed in L1Y1229H mice, suggesting that ALCAM may be critical for the EphB-mediated signaling via L1 (Buhusi et al., 2009). Lastly, neuronglia related CAM (NrCAM) is a member of the L1 subfamily of CAMs, which is expressed in a similar pattern to L1 and ALCAM. Consistent with this, knockouts of NrCAM show similar L-M errors in topography (Dai et al., 2013). Intriguingly, EphB can phosphorylate NrCAM, which inhibits its ability to recruit ankyrin to the cell membrane, akin to its action on L1. Together, these data suggest that these related CAMs may signal in a complex downstream of EphBs to regulate topographic mapping.

4.2. Spontaneous activity

While molecular cues clearly play important roles in the establishment of retinofugal topography, experimental evidence suggests that they represent only part of the story. For instance, in the absence of any of the cues described above, the most common phenotype observed are ectopic TZs rather than a complete loss of organization. The coalescence of aberrant projections into clustered TZs is reminiscent of the organization of eye-specific inputs in the SC and dLGN, which is mediated in large part by spontaneous activity in the form of retinal waves. Indeed, many groups have investigated the role of retinal waves in the establishment of topography and have built a strong case in favor of them playing an instructive role in circuit formation (Ackman & Crair, 2014; Feller, 2009).

4.2.1. Stage II cholinergic waves instruct retinofugal topography

During development of the mammalian visual system, spontaneous neuronal activity propagates across the retina in a wave-like manner, such that neighboring clusters of RGCs have highly correlated patterns of activity. These waves progress through three developmental stages based on the mode of propagation: Stage I retinal waves occur during late gestation in rodents and are mediated through gap junctions; Stage II retinal waves are orchestrated by cholinergic starburst amacrine cells and occur from ~P0–10 in mice; and, Stage III waves are mediated via glutamatergic signaling driven by bipolar cells and modulated by amacrines and predominate from ~P10–15. A preponderance of evidence supports Stage II waves as the critical drivers of retinotopy, though Stage III waves are capable of compensating to some degree (Chandrasekaran, Plas, Gonzalez, & Crair, 2005).

Pharmacological manipulations confirmed that Stage II waves are mediated by the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR), specifically those containing the β2 subunit (Feller, Wellis, Stellwagen, Werblin, & Shatz, 1996; Wong, Myhr, Miller, & Wong, 2000). Indeed, the pattern of spontaneous activity during the first postnatal week is dramatically altered, though not absent, in β2-nAChR−/− mice (Bansal et al., 2000; Burbridge et al., 2014; McLaughlin, Torborg, Feller, & O’Leary, 2003; Stafford, Sher, Litke, & Feldheim, 2009; Sun, Warland, Ballesteros, van der List, & Chalupa, 2008). As a result, RGC projections to the SC and dLGN are dramatically disrupted, failing to refine to condensed TZs (Fig. 2C) (Chandrasekaran et al., 2005; Grubb, Rossi, Changeux, & Thompson, 2003; McLaughlin, Torborg, et al., 2003). While more diffuse, TZs in both the SC and dLGN are centered in approximately the right topographic zone, reflecting the influence of molecular forces. As predicted, anatomical disruptions result in altered functional receptive fields of neurons in the SC, which are enlarged and elongated along the azimuth axis (Chandrasekaran et al., 2005; Mrsic-Flogel et al., 2005). Intriguingly, Stage II waves preferentially travel along the azimuth axis both in vitro (Stafford et al., 2009) and in vivo (Ackman, Burbridge, & Crair, 2012).

These functional findings support an instructive role for Stage II waves in circuit development, as do multiple other lines of evidence. First, the level of RGC activity in β2-nAChR−/− mice is similar to that of control mice, arguing against a simply permissive role for Stage II waves. Second, conditional deletion of β2-nAChR specifically from the retina, but not the midbrain, results in alterations to wave patterns and topographic order similar to those observed in global knockouts (Burbridge et al., 2014). Finally, using the tet-Off inducible expression system, Xu and colleagues were able to over-express β2-nAChR specifically in RGCs in the background of a global knockout (Xu et al., 2011). This manipulation restored correlated activity in the developing retina, though waves were more spatially restricted. Intriguingly, topographic order was rescued in both the dLGN and SC for RGCs originating from the dorsonasal two thirds of the retina, but not the ventrotemporal third. As this region overlaps with ipsilaterally-projecting RGCs, the authors suspected an interaction and found that topography was rescued regardless of retinal origin location when binocular competition was eliminated via enucleation.

4.2.2. Exogenously manipulated activity can shape retinofugal topography

In order to further assess the instructive role activity plays in establishing topography, recent studies have leveraged techniques to manipulate the pattern of activity during development. In one study, the light-activatable channel rhodopsin (ChR2) was expressed in ~20% of RGCs under the control of the Thy1 promoter (Thy1-ChR2), allowing for stimulation via focused light exposure to the eyes (Zhang, Ackman, Xu, & Crair, 2011). A critical finding from these experiments was that synchronous activation of both eyes from ~P9–12 reduced, while asynchronous activation enhanced, eye-specific segregation in the SC and dLGN. Further, optogenetic activation of RGCs resulted in smaller TZs and partially rescued topographic deficits in β2-nAChR−/− mice.

Using a similar strategy, Munz and colleagues demonstrated that exogenously induced correlated firing stabilized RGC axonal branching in the OT, resulting in more compact terminal arbors and more efficient relay to tectal neurons (Munz et al., 2014). In this study, the authors took advantage of the observation that occasionally, a single RGC will project to the ipsilateral OT in Xenopus laevis tadpoles. By rearing tadpoles in varying visual environments or expressing ChR2 in these projections, they could be forced to fire synchronously or asynchronously with neighboring RGC fibers from the opposing eye. Intriguingly, asynchronous activation increased arbor dynamics whether the period of stimulation followed an epoch of darkness or synchronous stimulation, while synchronous activation only resulted in modest increases in dynamics when following a dark epoch.

Finally, manipulations of the pattern of visual experience can alter the topographic organization of RGC inputs to the OT in tadpoles. In normally-reared tadpoles, the predominant direction of optic flow is in the A-P direction as the tadpole swims forward. In a clever experiment, Hiramoto and Cline reared tadpoles in visual environments in which they were exposed to a natural stimulus (alternating white and black bars moving A to P) or the opposite (Hiramoto & Cline, 2014). Amazingly, 4 days of exposure to the natural direction of optic flow sharpened the topographic distribution of RGCs in the OT, while this sharpening did not occur in animals reared in the opposite environment nor in those dark-reared.

4.2.3. NMDARs play a critical role in activity-dependent map formation

The detection of coincident neuronal firing driven by spatially-correlated Stage II waves is critical for proper topographic map refinement, and several studies suggest that N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) mediate this process. NMDARs are coincidence detectors that require both a membrane depolarization and glutamate to be activated and are thus well-suited for this task. Indeed, pharmacologic blockade of NMDAR function via topical application of MK-801 to the tectal surface results in disrupted retinotectal topography (Cline & Constantine-Paton, 1989). And, similar manipulations with MK-801 or AP5 in the rat SC results in topographic mapping errors (Simon, Prusky, O’Leary, & Constantine-Paton, 1992). Further, NMDARs play important roles in regulating the dynamics and stabilization of RGC terminal arbors (Ruthazer, Akerman, & Cline, 2003; Sin, Haas, Ruthazer, & Cline, 2002). Interestingly, NMDARs may mediate both synaptic strengthening and elimination in the SC during development. On one hand, NR2A-containing NMDARs are required for induction of long-term potentiation in the SC in juvenile mice (P15–17) (Zhao & Constantine-Paton, 2007). On the other hand, activation of NMDARs results in synaptic depression and synaptic elimination in the SC at earlier developmental stages (Colonnese & Constantine-Paton, 2006; Shi, Aamodt, Townsend, & Constantine-Paton, 2001).

As in other systems, NMDARs are critical for plasticity in the SC, which can be induced experimentally through lesion or manipulation of activity patterns. In a model of optic nerve crush, which induces regeneration and re-innervation of the goldfish OT, NMDAR function is required for the refinement of tectal receptive fields (Schmidt, 1990). Similarly, partial ablation of the SC results in map compression with compensating plasticity to maintain receptive field size (Finlay, Schneps, & Schneider, 1979; Pallas & Finlay, 1989), which is prevented when NMDAR activity is blocked (Huang & Pallas, 2001). As discussed above, the ability of exogenously synchronized activation to limit branch dynamics and optic flow-induced shifts in topographic position are dependent on signaling through NMDARs (Hiramoto & Cline, 2014; Munz et al., 2014). Together, these studies implicate NMDARs in playing critical roles in activity-dependent circuit development in the SC; however, it remains unclear whether NMDAR function is required solely on the post-synaptic side of the cleft or if molecules localized pre-synaptically may contribute as well.

4.3. Axon-axon competition

As mentioned previously, a putative mechanism by which nasal RGCs are guided to terminate in regions of highly repellant ephrin-A expression is biased competition. That is, RGC axons that express relatively lower levels of EphA receptor in any given region are less repelled and, thus, capable of establishing synapses in regions neighboring axons cannot. Rather than compete for synaptic territory with these neighboring axons, those originating from the nasal retina terminate in more posterior regions. Though some controversy exists, computational and genetic mouse models support a competitive mechanism in establishing retinocollicular topography.

4.3.1. Clues of competitive forces from molecular manipulations

Genetic mouse models in which the EphA/ephrin-A gradient has been altered support a competitive mechanism. As discussed above, single or combination knockout of EphA or ephrin-A molecules results in topographic mapping errors. Importantly, however, bulk labeling of RGCs reveals that the entire target region of either the dLGN or SC are completely filled (Feldheim et al., 2000), suggesting that RGCs establish similar numbers of synapses. Additionally, in Isl2EphA3/EphA3 mice, Isl2+ axons expressing exogenously high EphA levels terminate in regions that would be occupied by Isl2− RGCs from the anterior SC, effectively out-competing them for this territory (Brown et al., 2000). Indeed, genetically-labeled classes of Isl2+ and Isl2− RGCs are sharply segregated into the anterior and posterior regions of the SC in Isl2EphA3/EphA3 mice, respectively (Triplett et al., 2014). Intriguingly, this segregation is reflected in altered functionality in each sub-region, but not altered receptive field size (Kay & Triplett, 2017), again suggesting competitive forces help shape optimal RGC convergence.

4.3.2. Models of reduced RGC axon-axon competition reveal a role in topographic mapping

To more directly test the hypothesis that RGC axon-axon competition plays a role in establishing topography, models in which the total number of RGCs is reduced have been utilized. In one such approach, retinocollicular topography was assessed in mice lacking the transcription factor Math5 (Atoh7), which plays a critical role in RGC differentiation (Brown, Patel, Brzezinski, & Glaser, 2001). As a result, the RGC population in Math5−/− mice is only 5–20% of that found in controls. In strong support of competitive mechanisms, bulk labeling reveals that RGCs innervate only the anteromedial portion of the SC (Fig. 2D) (Triplett et al., 2011). Furthermore, both antero- and retrograde tracing experiments suggest that topographic order within this region is disrupted. These data are consistent with computational models that incorporate combinations of ephrin-A/EphA repulsive, ephrin-B/EphB attractive and competitive forces (Triplett et al., 2011). Of note, in an evaluation of multiple computational models of retinocollicular mapping based on experimental data, the Koulakov model developed in this study performed most efficiently (Hjorth, Sterratt, Cutts, Willshaw, & Eglen, 2014).

Consistent with these findings, a less dramatic reduction in RGC numbers yielded similar changes in topography, as well as altered eye-specific segregation. Using the Pax6α-Cre line, which is expressed in nasal and temporal “wedges” of the retina but not central retina, Maiorano and Hindges reduced axon-axon competition by crossing this line with mice harboring floxed alleles of Dicer (Maiorano & Hindges, 2013). As a result, retinal progenitors at the nasal and temporal poles undergo apoptosis, leading to an ~40% reduction in the number of RGCs by P8. However, these remaining RGC axons occupy a substantial proportion of the SC, suggesting a plasticity in response to reduced competition. In addition, the authors report disrupted topographic organization, as revealed by both anterograde and retrograde tracing. Finally, the reduction in competition also results in an alteration of eye-specific segregation, such that ipsilaterally-projecting RGCs occupy the superficial layers in the anterior- and posterior-most SC which are unoccupied by contralaterally-projecting RGCs.

Another approach at reducing RGC numbers yielded less convincing results in support of axon-axon competition. In that study, progenitor cells from a zebrafish donor embryo that expresses GFP driven by the Brn3c promotor were transplanted into either a wild type or lakritz mutant host (Gosse, Nevin, & Baier, 2008). Since lakritz mutants fail to develop due to a disruption in the Ath5 (Atoh7) transcription factor and Brn3c is expressed exclusively in RGCs, the authors could visualize single, labeled RGCs in an otherwise RGC-less fish. By determining the location of the posterior-most branch of the terminal arbor in the tectum as a function of RGC cell body location in the retina, the authors found that the organization in the lakritz background was identical to control. Intriguingly, when the same analysis was performed for the anterior-most branch, the fidelity of topographic order decreased, though order was still ostensibly present.

Consistent with these results, manipulations of neuronal activity suggest that comparative levels of synaptic vesicle release influence terminal arbor size. By expressing the tetanus toxin light chain (TeNT) in single RGCs, Ben Fredj and colleagues found that terminal arbor size was increased compared to control axons (Ben Fredj et al., 2010). However, when TeNT was expressed in a background of other vesicle release incapable RGCs, terminal size was similar to control axons in an unaltered background. Similar to other activity-dependent manipulations in the context of retinocollicular mapping, NMDARs functioned as mediators of this competition. Intriguingly, however, manipulations of Stage II waves in the context of reduced RGC numbers did not exert dramatic effects. In Math5−/−;β2-nAChR−/− combination mutants, RGCs remained restricted to the anterior-medial SC (Fig. 2J) (Triplett et al., 2011). However, focal tracing was not performed in these animals, so the precise impact on topographic order remains unclear. Together, these data suggest that the influence of competitive forces may vary depending on organismal context.

4.4. Interactions between forces

Thus far, we have discussed the forces driving topographic map formation in isolation. However, molecular cues, spontaneous activity, and competition operate in overlapping temporal windows in vivo. Indeed, recent work has highlighted that these forces interact with one another during development, particularly ephrin-A/EphA signaling and Stage II waves.

4.4.1. Neuronal activity facilitates ephrin-A/EphA-mediated signaling

While activity has a clearly instructive role in its own right, evidence suggests that it is also required for efficient signaling of molecules that guide topographic mapping. To uncover this function, Nicol and colleagues developed an in vitro system in which they cultured retinal explants with SC slices (Nicol et al., 2007). When they blocked activity in this system, they found that ingrowing RGCs failed to prune branches in inappropriate topographic areas. Since they could manipulate the genotype of the retinal explant and SC explant independently, they were able to demonstrate that this was not due to a synaptic transmission mechanism. Further, in vitro growth cone collapse assays revealed that repulsion mediated by bath addition of ephrin-A5 was inhibited when action potentials were blocked with tetrodotoxin. Amazingly, they demonstrated that oscillations of cyclic AMP (cAMP) induced by uncaging could ameliorate this effect. Consistent with this, mice lacking functional adenylate cyclase 1 (AC1), which catalyzes the formation of cAMP, exhibit topographic mapping errors (Plas, Visel, Gonzalez, She, & Crair, 2004). And retina-specific, but not midbrain-specific, deletion of AC1 is sufficient to cause these errors (Dhande et al., 2012). Intriguingly, subsequent studies suggest that ephrin-As induce cAMP formation localized to lipid rafts which may be crucial for local guidance events (Averaimo et al., 2016). However, it remains unclear what role activity might play in the generation of these signals or if they act in parallel pathways.

In contrast to these studies, in vivo manipulations suggest that ephrin-A/EphA signaling and spontaneous activity are separable phenomena. By electroporating RGCs in utero, Benjumeda and colleagues were able to label axonal projections and express an inward-rectifying potassium channel (Kir2.1) to reduce activity (Benjumeda et al., 2013). In this system, the authors found that RGCs project to topographically appropriate regions in the SC, and co-expression of EphA6 results in an anteriorly-shifted termination zone even in Kir2.1+ RGCs. Notably, terminal arbors of single RGCs were less dense when activity was reduced, suggesting the primary function of Stage II waves may be condensation of terminal branches rather than gross axonal guidance.

4.4.2. Interactions between molecular cues and neuronal activity

At the resolution of groups of neurons, both molecular cues and spontaneous activity should act in concert to shape an ordered topographic map of space. Indeed, in combination ephrin-A2−/−;ephrin-A5−/−;β2-nAChR−/− mice, topographic order along the azimuth axes of both the SC and dLGN is completely abolished (Fig. 2G) (Pfeiffenberger et al., 2006). Intriguingly, however, disruption of Stage II waves does not interfere with the duplication along the azimuth axis of the SC observed in Isl2EphA3/EphA3 mice (Fig. 2H) (Triplett et al., 2009). Further, recent studies suggest that local clustering of similarly tuned visual neurons may exist in the SC (Ahmadlou & Heimel, 2015; Feinberg & Meister, 2015), which by necessity must disregard the precise local topography, suggesting that more complex interactions between these forces may exist. A recent study leveraging an animal model in which molecular and activity- driven forces were put in opposition revealed one potential mechanism by which such organizations may be achieved. In heterozygous Isl2EphA3/+, the EphA3 receptor is over-expressed in Isl2+ RGCs, but not to the same level as in homozygotes (Bevins et al., 2011; Brown et al., 2000; Reber et al., 2004). Thus, in temporal regions of the retina, the distinction between EphA levels in neighboring Isl2+ and Isl2− RGCs is less sharp. In initial anatomical tracing experiments, it appeared that rather than a complete duplication of the retina’s projection along the SC’s A-P axis, as in Isl2EphA3/EphA3 mice, the map was only partially duplicated in Isl2EphA3/+ mice (Bevins et al., 2011; Brown et al., 2000). However, later experiments revealed a more complex situation.

In Isl2EphA3/+ mice, the functional organization of the SC was found to be heterogeneous (Owens et al., 2015). That is, in ~25% of cases, the map is partially duplicated, as predicted by anatomical studies. Intriguingly, the functional map is similar to a wild type organization in ~25% of heterozygotes; and, in ~50% of cases the organization is “mixed,” meaning some regions appeared to be singular, while other regions were duplicated (Fig. 2F). Such heterogeneity suggests a stochasticity in local map organizations, which may be dictated by opposing molecular and activity-dependent forces. In support of this, map organizations are not only heterogeneous between animals, but even between colliculi of the same animal, ruling out potential genetic background causes. Further, when Stage II waves are disrupted by crossing into the β2-nAChR−/− line, heterogeneity is eliminated and all maps appear singular (Fig. 2I). Finally, mathematical models in which the difference in EphA expression between Isl2+ and Isl2− RGC populations could be altered replicates in vivo data. Together, these data suggest that in Isl2EphA3/+ mice, molecules and activity are forced into precarious balance and each can dictate local map organization in a seemingly stochastic manner. Such a mechanism could allow for local rearrangements to prioritize synapse formation in functionally-relevant ways at the expense of topography.

5. Mechanisms of laminar-specific targeting

A critical feature of vision is the parallel nature of processing, in which different subclasses of the same neuronal type are tuned to distinct features of the visual scene. For example, recent functional and molecular finger-printing analyses have identified upwards of 40 subclasses of RGCs (Baden et al., 2016; Rheaume et al., 2018). As this information is relayed to image-forming targets, terminations are localized to specific sublayers to facilitate efficient transfer of information (Inayat et al., 2015; Piscopo, El-Danaf, Huberman, & Niell, 2013; Shi et al., 2017). Thus, deciphering the developmental mechanisms by which these connections are established is a critical area of investigation. Current studies have focused on the contribution of topographic order, neuronal activity, and molecular cues to uncover these mechanisms.

5.1. Limited influence of topographic order

Despite the temporal overlap in the development of retinocollicular topography and laminar refinement of RGC subtypes, these two events are achieved via independent guidance mechanisms. To visualize subclass-specific arbors, multiple lines leveraging BAC transgenics to express GFP or Cre recombinase have been generated. For instance, in CB2-GFP mice a subset of “transient” OFF-aRGCs is labeled with GFP, which terminate in the core of the dLGN and the lSGS in the SC (Huberman et al., 2008). In contrast, in DRD4-GFP and TRHR-GFP mice, related, but distinct, direction-selective RGCs are labeled, and both terminate in the shell of the dLGN and uSGS of the SC (Huberman et al., 2009; Rivlin-Etzion et al., 2011). When these lines are crossed into an ephrin-A5−/− or ephrin-A2/A5−/− background, each still targets the appropriate sublamina (Sweeney, James, Sales, & Feldheim, 2015). Intriguingly, the authors of this study also found that ectopic TZs tend to be specific to either the uSGS or lSGS, implicating a misalignment of functional map organizations. In further support of their independence, DRD4-GFP and CB2-RGCs target the appropriate sublaminae in the SC of Isl2EphA3/EphA3, despite a dramatic rearrangement into distinct subzones (Triplett et al., 2014). Together, these studies suggest that topography and laminar targeting are distinct events in the SC; however, whether the same is true in the dLGN remains unclear.

5.2. Activity-independent laminar targeting

Investigations in both the mouse SC and zebrafish OT suggest that laminar targeting does not rely on normal patterns of spontaneous or visually-evoked activity. By crossing CB2-GFP mice into the β2-nAChR background, Huberman and colleagues were able to assess the role of Stage II waves in lamina-specific targeting (Huberman et al., 2008). In this context, CB2-GFP+ RGCs terminate in the ventromedial core region, similar to the pattern observed in controls. Similarly, axon terminals are restricted to the lSGS in the SC; however, the “columnar” organization of CB2-GFP+ RGCs is disrupted in β2-nAChR−/− mice. Consistent with these findings, the exquisite lamination observed in the zebrafish OT is not altered when activity patterns are changed in a variety of ways. Nevin and colleagues leveraged a line in which expression of GFP was driven by Pou4f3, which labels ~40% of RGCs to assess retinotectal targeting (Nevin, Taylor, & Baier, 2008). Neither manipulation of visual experience by dark rearing nor pharmacologic blockade of activity nor blockade of vesicle release altered the lamination pattern of Pou4f3:GFP arbors in the OT. Together, these data suggest that a molecular, rather than activity-dependent mechanism is utilized to establish lamina-specific targeting.

5.3. Molecular regulators of lamina-specific targeting

While by no means as well understood as the forces controlling topographic mapping, molecular cues that regulate lamina-specific targeting in the OT have been identified. To begin, analysis of Pou4f3-labeled RGCs via a GAL4::UAS system revealed deficits in tectal targeting in zebrafish harboring a mutation of a subunit of type IV collagen (Col4a5) (Xiao & Baier, 2007). Importantly, immunohistochemical markers of tectal laminae are normal in these mutants, suggesting a direct guidance role. Interestingly, treatment with heparitinase phenocopies these results, suggesting that heparin sulfate proteoglycans play a critical role in laminar targeting. Indeed, subsequent studies demonstrated that a gradient of slit1 originating from the basement membrane is necessary for targeting and that this action is mediated by the robo2 receptor (Xiao et al., 2011). Finally, a forward genetic screen identified topoisomerase 2beta (Top2b) as a key regulator of laminar targeting (Nevin, Xiao, Staub, & Baier, 2011). Since Top2b regulates DNA organization and transcription, the molecular cues at the surface responsible for guidance errors observed in this mutant remain unclear. However, these cues are expressed by RGCs, since errors are observed in Top2b-deficient RGCs innervating a wild type OT, but lamination is unaltered in the reverse context.

5.4. Relationship between laminar targeting and development of tuning

The exquisite laminar organization of RGC subtype axons in the SC/OT and dLGN suggests its importance in relaying visual information. However, a recent study suggests that a properly laminated OT is not essential for establishing functional circuitry [Nikolaou & Meyer, 2015]. To test the role of lamination, these investigators utilized the astray (astti272z) line, which disrupts robo2 expression (Fricke, Lee, Geiger-Rudolph, Bonhoeffer, & Chien, 2001), resulting in altered laminar targeting in the OT (Xiao et al., 2011). Indeed, the targeting of multiple direction-selective RGCs is disrupted in astti272z mutants, and the morphology of direction-selective tectal cells is also dramatically altered (Nikolaou & Meyer, 2015). Despite this, the expected repertoire of direction-selectivity in the tectum of older animals is intact; however, the rate of circuit development is delayed compared to controls. The authors further demonstrated that specific rescue of robo2 in RGCs or tectal cells can serve as a positional cue for the dendrites or axons of the reciprocal population. Together, these data suggest that laminar targeting is required for efficient assembly of functional circuits but that other mechanisms may regulate the establishment of specific synapses.

6. Mechanisms of visual map alignment

In many visual, auditory, and somatosensory nuclei, neurons and their projections are organized topographically; in multisensory areas, these maps are aligned in order to facilitate integration and lower the threshold for detection of salient stimuli (Stein, Stanford, & Rowland, 2014). The SC is one such region (Basso & May, 2017), and investigations into the mechanisms by which L5-V1 inputs to the SC are aligned with RGCs has advanced our understanding of how these processes may occur in other modalities and regions.

6.1. Retinal instruction of corticocollicular projection alignment

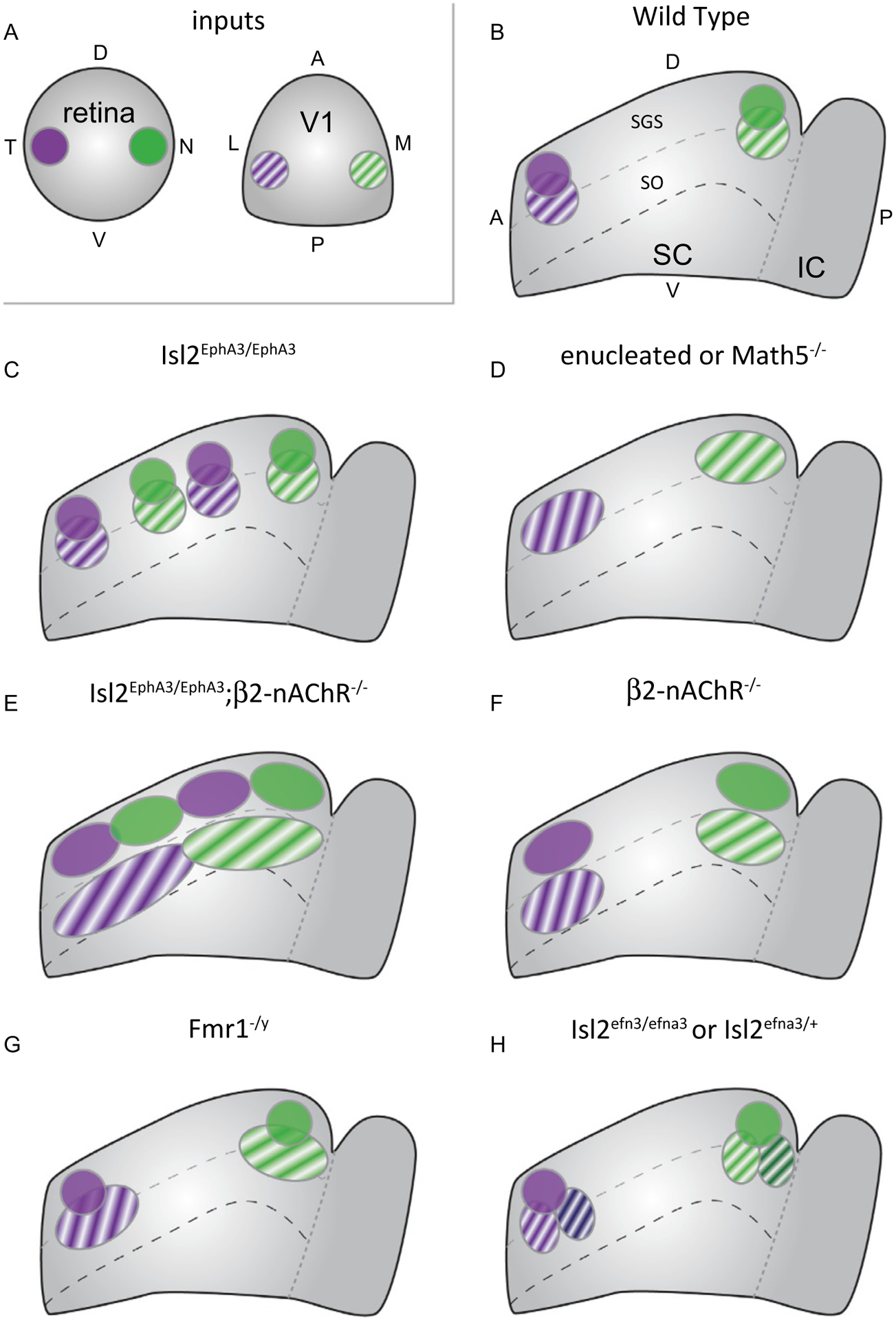

Two models have been proposed to explain how RGC and V1 inputs could be aligned in the SC. First, since similar gradients of ephrin-As/EphAs are observed along the L-M axis in V1, alignment could be achieved by a gradient-matching mechanism. Second, since L5-V1 projections innervate the SC after the retinocollicular map is established and partially course through the retinorecipient region, they could be aligned by “reading” the existing map. Experiments in Isl2EphA3/EphA3 mice were able to distinguish between these models. In contrast to the retinocollicular projection, the retinogeniculate projection in Isl2EphA3/EphA3 mice is maintained as a single map (Fig. 2E), and the cortical representation of visual space is similar to controls (Triplett et al., 2009). Strikingly, anatomical tracing experiments demonstrate that the L5-V1 to SC projection in these mice is duplicated along the azimuth to align with the retinal map (Fig. 3C). Notably, L5-V1 inputs do appear to be capable of responding to the endogenous ephrin-A/EphA gradients in the SC, as rough topography is maintained when RGC input is reduced via enucleation or in Math5−/− mice (Fig. 3D) (Triplett et al., 2009).

Fig. 3.

Summary of effects of manipulations that impact visual map alignment in the SC. (A & B) The superior colliculus (SC) receives inputs from the retina and primary visual cortex (V1) (A). RGCs from temporal retina and layer 5 (L5) neurons from lateral V1, which monitor the same region of space, terminate in the anterior portion of the SC (B). Likewise, RGCs from nasal retina and medial V1 terminate posteriorly. RGCs terminate in the stratum griseum superficiale (SGS), while V1 projections terminate more ventral, within the stratum opticum (SO) but overlapping RGC inputs. (C) In Isl2EphA3/EphA3 mice, the retina’s projection is duplicated along the anterior-posterior axis and V1 projections duplicate to maintain alignment. (D) When retinal input to the SC is reduced by enucleation or knockout of Math5, L5-V1 axons terminate in topographically appropriate regions, though termination zones (TZs) are broader. (E) When Stage II waves are disrupted in Isl2EphA3/EphA3 mice, L5-V1 inputs fail to align with the duplicated retinal map. (F) In β2-nAChR knockout mice with disrupted waves, L5-V1 axons terminate in topographically appropriate region, though TZs are broader and less overlapped with retinal inputs. (G) In fragile X mice (Fmr1−/y), retinocollicular topography is intact, but L5-V1 neurons have broader TZs. (H) In Islet2-ephrinA3 knock-in mice (Isl2efna3), the retinal projection to the SC is topographically ordered, but the TZs of L5-V1 inputs are partially duplicated and slightly shifted.

The mechanism underlying retinal instruction of L5-V1 input alignment is not fully understood and could involve molecular cues, activity, or a combination thereof. To determine the role of Stage II waves, Isl2EphA3/EphA3 mice were crossed into the β2-nAChR−/− background. In these combination mutants, the retinocollicular projection remains duplicated, but each termination zone is poorly refined (Fig. 2H). However, tracing experiments suggest that L5-V1 neurons project to form a single, broad map that is effectively misaligned with the retinal map (Fig. 3E). Notably, however, overlap between L5-V1 TZs and retinal input is significantly decreased in β2-nAChR−/− mice (Fig. 3F) (Triplett et al., 2009), potentially preventing any retinal instruction via molecular cues.

The downstream pathways utilized in an activity-dependent mechanism of retinal instruction remain unclear. Interestingly, recently developed computational models of visual map alignment in the SC support an activity-dependent mechanism that could proceed via simple correlational firing between RGCs and L5-V1 or a Hebbian-like mechanism in which SC neurons integrate RGC and L5-V1 inputs (Tikidji-Hamburyan, El-Ghazawi, & Triplett, 2016). And, investigations in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome (Fmr1−/y) implicate the fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) in the regulation of visual map alignment in the SC (Kay, Gabreski, & Triplett, 2018). Functional analyses in Fmr1−/y mice reveal increases in receptive field size, decreased direction-selectivity, and hyperactivity of orientation-selective neurons in the SC. Intriguingly, topography of RGC projections to the SC are unperturbed, but those from V1 are enlarged (Fig. 3G). These data suggest that FMRP may play a specific role in the development or maintenance of visual map alignment in the SC. Given its well described role in neuronal plasticity, FMRP may provide a link between neuronal activity and visual map alignment.

In opposition to findings supporting an activity-dependent mechanism of retinal instruction of visual map alignment, recent data provides compelling support for the influence of ephrin-As expressed on RGC axons in the SC. To demonstrate this, Savier and colleagues generated an Islet2-ephrin-A3 knock-in mouse model (Isl2efna3) (Savier et al., 2017). Anatomical tracing experiments in these mice suggest that topography of the retinocollicular projection is organized similar to controls, as a single map of visual space along the azimuth axis. However, rather than a single TZ for each V1 labeling, as observed in controls, approximately 50% of TZs are partially- or fully-duplicated in Isl2efna3/efna3 and Isl2efna3/+ mice (Fig. 3F). Notably, the duplication observed in this context is distinct from that reported in Isl2EphA3/EphA3 mice, appearing as a subtle displacement along the A-P axis rather than two well-separated TZs. Amazingly, L5-V1 topographic mapping errors are abrogated when the authors generated Isl2EphA3/efna3 “double heterozygous” mice, which effectively blocks ephrin-A3 signaling by increasing cis interactions within RGC axons. Further, a novel 3-step computational model that incorporates alterations to the ephrin-A/EphA gradient based on cues transported along RGC axons replicates these in vivo findings (Savier et al., 2017).

7. Concluding remarks

Subcortical visual circuits have served as valuable models to elucidate fundamental mechanisms by which molecular cues, neuronal activity, and axon-axon competition drive brain wiring. In the 70+ years since Sperry’s initial investigations into the regenerating retinotectal projection, we have achieved an almost complete understanding of the mechanisms by which topographic maps of visual space are established. However, several problems remain for the field to solve in order to provide a complete understanding of how these circuits are wired. First, the paradox of nasal axon mapping remains flummoxing. While support exists for multiple mechanisms, a unified model would solidify, and largely complete, our understanding of retinocollicular/retinotectal topographic map formation. Second, the mechanisms by which different subclasses of RGCs establish specific connections in the SC/OT and dLGN remains poorly understood. Surprisingly, in the decade or so since the generation of valuable tools to label different RGC subtypes in both fish and mice, only a few cues have been identified. One potential cause for this may be the very genetics that allow for labeling, since double or triple transgenic mice may be needed to assess the role of a candidate gene for each given line. Developing tools that allow for labeling different subtypes by a molecular means, such as viruses or electroporation, would allow for more rapid screening. Solving this mystery is critical, both for understanding how subcircuits are established and for aiding the development of regenerative therapies. Finally, elucidating the mechanisms by which topographic maps of space are aligned with one another presents a significant challenge. This is particularly true for cortical inputs to the dLGN, which play a critical role in processing. Further, while progress is being made in understanding the mechanisms of alignment in the SC, multiple cortical regions integrate sensory inputs, yet we have little understanding of how these circuits are assembled. Underscoring this is the prevalence of deficits in sensory processing and integration in neurodevelopmental disorders. As our recent work suggests, elucidating the organization of topographic maps in integrative centers may provide critical insights into the neural correlates of this dysfunction.

References

- Ackman JB, Burbridge TJ, & Crair MC (2012). Retinal waves coordinate patterned activity throughout the developing visual system. Nature, 490, 219–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackman JB, & Crair MC (2014). Role of emergent neural activity in visual map development. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 24, 166–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadlou M, & Heimel JA (2015). Preference for concentric orientations in the mouse superior colliculus. Nature Communications, 6, 6773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averaimo S, Assali A, Ros O, Couvet S, Zagar Y, Genescu I, et al. (2016). A plasma membrane microdomain compartmentalizes ephrin-generated cAMP signals to prune developing retinal axon arbors. Nature Communications, 7, 12896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baden T, Berens P, Franke K, Rosón MR, Bethge M, & Euler T (2016). The functional diversity of retinal ganglion cells in the mouse. Nature, 529, 345–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baier H (2013). Synaptic laminae in the visual system: Molecular mechanisms forming layers of perception. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology, 29, 385–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal A, Singer JH, Hwang BJ, Xu W, Beaudet A, & Feller MB (2000). Mice lacking specific nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits exhibit dramatically altered spontaneous activity patterns and reveal a limited role for retinal waves in forming ON and OFF circuits in the inner retina. The Journal of Neuroscience, 20, 7672–7681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso MA, & May PJ (2017). Circuits for action and cognition: A view from the superior colliculus. Annual Review of Vision Science, 3, 197–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Fredj N, Hammond S, Otsuna H, Chien C-B, Burrone J, & Meyer MP (2010). Synaptic activity and activity-dependent competition regulates axon arbor maturation, growth arrest, and territory in the retinotectal projection. The Journal of Neuroscience, 30, 10939–10951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjumeda I, Escalante A, Law C, Morales D, Chauvin G, Muca G, et al. (2013). Uncoupling of EphA/ephrinA signaling and spontaneous activity in neural circuit wiring. The Journal of Neuroscience, 33, 18208–18218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevins N, Lemke G, & Reber M (2011). Genetic dissection of EphA receptor signaling dynamics during retinotopic mapping. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31, 10302–10310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braisted JE, McLaughlin T, Wang HU, Friedman GC, Anderson DJ, & O’Leary DD (1997). Graded and lamina-specific distributions of ligands of EphB receptor tyrosine kinases in the developing retinotectal system. Developmental Biology, 191, 14–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NL, Patel S, Brzezinski J, & Glaser T (2001). Math5 is required for retinal ganglion cell and optic nerve formation. Development, 128, 2497–2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A, Yates PA, Burrola P, Ortuño D, Vaidya A, Jessell TM, et al. (2000). Topographic mapping from the retina to the midbrain is controlled by relative but not absolute levels of EphA receptor signaling. Cell, 102, 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi M, Demyanenko GP, Jannie KM, Dalal J, Darnell EPB, Weiner JA, et al. (2009). ALCAM regulates mediolateral retinotopic mapping in the superior colliculus. The Journal of Neuroscience, 29, 15630–15641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi M, Schlatter MC, Demyanenko GP, Thresher R, & Maness PF (2008). L1 interaction with ankyrin regulates mediolateral topography in the retinocollicular projection. The Journal of Neuroscience, 28, 177–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbridge TJ, Xu H. p., Ackman JB, Ge X, Zhang Y, Ye M-J, et al. (2014). Visual circuit development requires patterned activity mediated by retinal acetylcholine receptors. Neuron, 84, 1049–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreres MI, Escalante A, Murillo B, Chauvin G, Gaspar P, Vegar C, et al. (2011). Transcription factor foxd1 is required for the specification of the temporal retina in mammals. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31, 5673–5681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran AR, Plas DT, Gonzalez E, & Crair MC (2005). Evidence for an instructive role of retinal activity in retinotopic map refinement in the superior colliculus of the mouse. The Journal of Neuroscience, 25, 6929–6938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HJ, & Flanagan JG (1994). Identification and cloning of ELF-1, a developmentally expressed ligand for the Mek4 and Sek receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell, 79, 157–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HJ, Nakamoto M, Bergemann AD, & Flanagan JG (1995). Complementary gradients in expression and binding of ELF-1 and Mek4 in development of the topographic retinotectal projection map. Cell, 82, 371–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline HT, & Constantine-Paton M (1989). NMDA receptor antagonists disrupt the retinotectal topographic map. Neuron, 3, 413–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonnese MT, & Constantine-Paton M (2006). Developmental period for N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-dependent synapse elimination correlated with visuotopic map refinement. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 494, 738–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croteau LP, Kao TJ, & Kania A (2019). Ephrin-A5 potentiates netrin-1 axon guidance by enhancing Neogenin availability. Scientific Reports, 9, 12009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J, Buhusi M, Demyanenko GP, Brennaman LH, Hruska M, Dalva MB, et al. (2013). Neuron glia-related cell adhesion molecule (NrCAM) promotes topographic retinocollicular mapping. PLoS One, 8, e73000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J, Dalal JS, Thakar S, Henkemeyer M, Lemmon VP, Harunaga JS, et al. (2012). EphB regulates L1 phosphorylation during retinocollicular mapping. Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences, 50, 201–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyanenko GP, & Maness PF (2003). The L1 cell adhesion molecule is essential for topographic mapping of retinal axons. The Journal of Neuroscience, 23, 530–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhande OS, Bhatt S, Anishchenko A, Elstrott J, Iwasato T, Swindell EC, et al. (2012). Role of adenylate cyclase 1 in retinofugal map development. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 520, 1562–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhande OS, Hua EW, Guh E, Yeh J, Bhatt S, Zhang Y, et al. (2011). Development of single retinofugal axon arbors in normal and β2 knock-out mice. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31, 3384–3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drager UC, & Hubel DH (1975). Physiology of visual cells in mouse superior colliculus and correlation with somatosensory and auditory input. Nature, 253, 203–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher U, Kremoser C, Handwerker C, Löschinger J, Noda M, & Bonhoeffer F (1995). In vitro guidance of retinal ganglion cell axons by RAGS, a 25 kDa tectal protein related to ligands for Eph receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell, 82, 359–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg EH, & Meister M (2015). Orientation columns in the mouse superior colliculus. Nature, 519, 229–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldheim DA, Kim YI, Bergemann AD, Frisén J, Barbacid M, & Flanagan JG (2000). Genetic analysis of ephrin-A2 and ephrin-A5 shows their requirement in multiple aspects of retinocollicular mapping. Neuron, 25, 563–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldheim DA, Nakamoto M, Osterfield M, Gale NW, DeChiara TM, Rohatgi R, et al. (2004). Loss-of-function analysis of EphA receptors in retinotectal mapping. The Journal of Neuroscience, 24, 2542–2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldheim DA, & O’Leary DD (2010). Visual map development: Bidirectional signaling, bifunctional guidance molecules, and competition. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 2, a001768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldheim DA, Vanderhaeghen P, Hansen MJ, Frisén J, Lu Q, Barbacid M, et al. (1998). Topographic guidance labels in a sensory projection to the forebrain. Neuron, 21, 1303–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller MB (2009). Retinal waves are likely to instruct the formation of eye-specific retinogeniculate projections. Neural Development, 4, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller MB, Wellis DP, Stellwagen D, Werblin FS, & Shatz CJ (1996). Requirement for cholinergic synaptic transmission in the propagation of spontaneous retinal waves. Science, 272, 1182–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay BL, Schneps SE, & Schneider GE (1979). Orderly compression of the retinotectal projection following partial ablation in the newborn hamster. Nature, 280, 153–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke C, Lee J-S, Geiger-Rudolph S, Bonhoeffer F, & Chien C-B (2001). Astray, a zebrafish roundabout homolog required for retinal axon guidance. Science, 292, 507–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisén J, Yates PA, McLaughlin T, Friedman GC, O’Leary DD, & Barbacid M. (1998). Ephrin-A5 (AL-1/RAGS) is essential for proper retinal axon guidance and topographic mapping in the mammalian visual system. Neuron, 20, 235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosse N, Nevin L, & Baier H (2008). Retinotopic order in the absence of axon competition. Nature, 452, 892–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubb MS, Rossi FM, Changeux J-P, & Thompson ID (2003). Abnormal functional organization in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus of mice lacking the beta 2 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Neuron, 40, 1161–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen MJ, Dallal GE, & Flanagan JG (2004). Retinal axon response to ephrin-as shows a graded, concentration-dependent transition from growth promotion to inhibition. Neuron, 42, 717–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasse JM, & Briggs F (2017). A cross-species comparison of corticogeniculate structure and function. Visual Neuroscience, 34, E016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch TK, & Quinlan EM (2018). Critical periods in amblyopia. Visual Neuroscience, 35, E014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higenell V, Han SM, Feldheim DA, Scalia F, & Ruthazer ES (2012). Expression patterns of Ephs and ephrins throughout retinotectal development in Xenopus laevis. Developmental Neurobiology, 72, 547–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindges R, McLaughlin T, Genoud N, Henkemeyer M, & O’Leary D (2002). EphB forward signaling controls directional branch extension and arborization required for dorsal-ventral retinotopic mapping. Neuron, 35, 475–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiramoto M, & Cline HT (2014). Optic flow instructs retinotopic map formation through a spatial to temporal to spatial transformation of visual information. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111, E5105–E5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorth JJJ, Sterratt DC, Cutts CS, Willshaw DJ, & Eglen SJ (2014). Quantitative assessment of computational models for retinotopic map formation. Developmental Neurobiology, 75, 641–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holash JA, Soans C, Chong LD, Shao H, Dixit VM, & Pasquale EB (1997). Reciprocal expression of the Eph receptor Cek5 and its ligand(s) in the early retina. Developmental Biology, 182, 256–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong YK, Kim I-J, & Sanes JR (2011). Stereotyped axonal arbors of retinal ganglion cell subsets in the mouse superior colliculus. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 519, 1691–1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooks BM, & Chen C (2020). Circuitry underlying experience-dependent plasticity in the mouse visual system. Neuron, 106, 21–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, & Pallas SL (2001). NMDA antagonists in the superior colliculus prevent developmental plasticity but not visual transmission or map compression. Journal of Neurophysiology, 86, 1179–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huberman AD, Manu M, Koch SM, Susman MW, Lutz AB, Ullian EM, et al. (2008). Architecture and activity-mediated refinement of axonal projections from a mosaic of genetically identified retinal ganglion cells. Neuron, 59, 425–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huberman AD, Wei W, Elstrott J, Stafford BK, Feller MB, & Barres BA (2009). Genetic identification of an on-off direction-selective retinal ganglion cell subtype reveals a layer-specific subcortical map of posterior motion. Neuron, 62, 327–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inayat S, Barchini J, Chen H, Feng L, Liu X, & Cang J (2015). Neurons in the most superficial lamina of the mouse superior colliculus are highly selective for stimulus direction. The Journal of Neuroscience, 35, 7992–8003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, & Feldheim DA (2018). The mouse superior colliculus: An emerging model for studying circuit formation and function. Frontiers in Neural Circuits, 12, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay RB, Gabreski NA, & Triplett JW (2018). Visual subcircuit-specific dysfunction and input-specific mispatterning in the superior colliculus of fragile X mice. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 10, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay RB, & Triplett JW (2017). Visual neurons in the superior colliculus innervated by Islet2+ or Islet2− retinal ganglion cells display distinct tuning properties. Frontiers in Neural Circuits, 11, 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I-J, Zhang Y, Meister M, & Sanes JR (2010). Laminar restriction of retinal ganglion cell dendrites and axons: Subtype-specific developmental patterns revealed with transgenic markers. The Journal of Neuroscience, 30, 1452–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]