Abstract

Purpose of Review

Farmers are routinely exposed to organic dusts and aeroallergens that can have adverse respiratory health effects including asthma. Horses are farm-reared large animals with similar exposures and can develop equine asthma syndrome (EAS). This review aims to compare the etiology, pathophysiology, and immunology of asthma in horses compared to farmers and highlights the horse as a potential translational animal model for organic dust-induced asthma in humans.

Recent Findings

Severe EAS shares many clinical and pathological features with various phenotypes of human asthma including allergic, non-allergic, late onset, and severe asthma. EAS disease features include variable airflow obstruction, cough, airway hyperresponsiveness, airway inflammation/remodeling, neutrophilic infiltrates, excess mucus production, and chronic innate immune activation.

Summary

Severe EAS is a naturally occurring and biologically relevant, translational animal disease model that could contribute to a more thorough understanding of the environmental and immunologic factors contributing to organic dust-induced asthma in humans.

Keywords: Equine asthma syndrome, Occupational asthma, Organic dust, Innate immunity, neutrophilic asthma, Bronchitis

Introduction

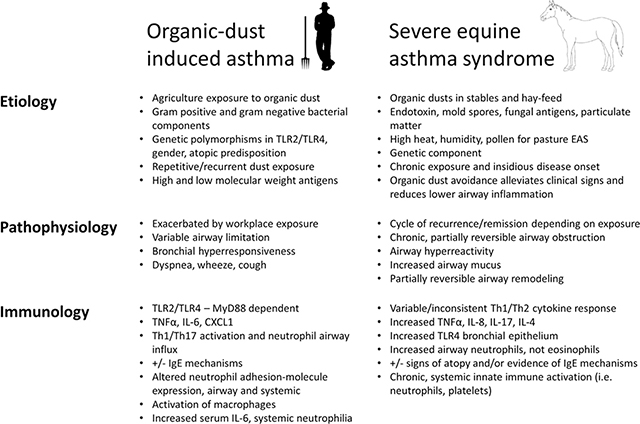

Asthma is a heterogeneous, chronic airway inflammatory disease with variable and reversible bronchoconstriction with symptoms of cough, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and wheeze. There are several asthma phenotypes including early versus late onset, allergic versus non-allergic, steroid resistant versus steroid sensitive, and asthma of variable disease severity [1]. Occupational and/or workplace exacerbated asthma represents an important phenotype of asthma in adults that can also have allergic and non-allergic features that are mediated by high-molecular-weight and/or low-molecular-weight antigen exposure [2]. Agriculture work is the largest form of employment in the world, and adverse respiratory health conditions, including asthma, are increased among farmers. Among farm operators with farm work-related asthma, 33% have reported asthma exacerbations at work [3]. Animal modeling of this occupational organic dust-associated asthma has focused primarily on rodent modeling strategies providing insight into innate and adaptive airway inflammatory responses. Alternatively, horses are farm-reared large animals that can naturally develop equine asthma syndrome (EAS), which shares features similar to both allergic and non-allergic asthma of humans. This chronic respiratory condition in horses is the result of environmental exposures similar to those experienced by agricultural workers. Indeed, horse barn exposure is also a risk factor for self-reported respiratory symptoms in humans [4–6]. In light of these shared exposure risks and respiratory outcomes in horses and humans, this review aims to compare what is known regarding the etiology, pathophysiology, and immunology of asthma in horses compared to farmers and highlight the horse as a possible translational animal model for organic dust-induced asthma, and related syndromes, in humans (Table 1).

Table 1:

Features of organic-dust induced human asthma vs. severe Equine Asthma Syndrome

|

Overview of EAS

Approximately 10–15% of adult horses living in temperate climates worldwide develop severe Equine Asthma Syndrome (sEAS), which is a chronic, non-infectious inflammatory lower airway disease that shares many similarities with human asthma, including reversible bronchoconstriction, bronchial hyperreactivity, increased mucus production, and airway wall remodeling [7, 8]. Clinically, these horses can present with symptoms that range in severity from exercise intolerance and cough, to severe expiratory dyspnea at rest [9]. Importantly, when horses affected with asthma syndrome are removed from environments containing inciting airborne agents, their clinical signs, and underlying airway inflammation resolves [10]. Whereas this disease was recently given the designation of severe EAS (sEAS) [11, 12], the clinical signs of sEAS in horses have been described since the times of ancient Greece. Within the more recent scientific and veterinary literature, the disease has been referred to as recurrent airway obstruction (RAO), equine chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, small airway disease, chronic bronchitis/bronchiolits, alveolar emphysema, broken-wind, hay sickness, and heaves [13].

Like asthma in humans, asthma in horses is a heterogeneous disease with two currently recognized phenotypes: mild/moderate EAS and sEAS. Mild/moderate EAS has been recently reviewed [11]. Briefly, compared to horses with sEAS, horses with mild/moderate EAS (previously referred to as Inflammatory Airway Disease, or IAD) are usually young to midd le -ag e d a nima ls with a l e s se r d eg re e o f bronchoconstriction, mucus production, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) inflammation with associated occasional cough, no respiratory signs at rest, reduced performance and/or prolonged recovery following exercise, and spontaneous improvement, or response to treatment [11]. Pulmonary function tests of these horses demonstrate lower airway obstruction and variable increased airway hyperreactivity [14]. The airway in- flammatory cellular influx of mild/moderate EAS is variable consisting of mast cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, or mixed cellular populations [11]. In mild/moderate EAS, ongoing research efforts are focusing on potential sub-phenotypes, and whether horses with mild/moderate EAS are at increased risk of developing sEAS. While it is currently unknown whether mild/moderate EAS spontaneously resolves through mechanisms of immune adaptation, the high prevalence of young horses with mild/moderate inflammation, but significantly low- er prevalence of sEAS in adult horses, does present parallels with respiratory inflammation in adult agricultural workers.

Diagnosis of sEAS

Severe equine asthma syndrome is most often diagnosed in horses greater than 7 years of age (equivalent to adult human), primarily through history and physical examination. Owner reported coughing and nasal discharge is significantly associated with diagnosis of sEAS [15], with cough often most notable when affected horses are in the barn, or at feeding time. Exercise intolerance is also a common owner concern for horses with sEAS. Affected horses demonstrate clinical signs related to the severity of mucus hypersecretion, bronchospasm, and airway obstruction. For example, these signs can include increased respiratory rate (respiratory rate > 20 breaths per minute), increased respiratory effort (increased movement of nasal alar folds), increased expiratory effort (as evidenced by increased flattening of the ventral abdomen), cough (often inducible by tracheal rubbing), and variable serous nasal discharge. Common abnormal findings include end-expiratory wheezes, early inspiratory crackles, and an in- creased lung field due to air trapping and lung hyperinflation. In less severely affected horses, abnormalities may only be appreciable with a rebreathing maneuver, which is performed by placing a bag over the horse’s nose for 3–4 min to promote deep breathing. For horses without active exposure to offending airborne antigens, physical examination can be within normal limits.

Although clinical history and symptoms usually suffice for the diagnosis of sEAS [16], ancillary tests are used to improve diagnostic accuracy, obtain baseline measures of disease sever- ity, monitor response to treatment, and conduct research studies. The degree of lower airway obstruction in horses can be measured by changes in transpleural pressure, either alone or in combination with airflow measured via a pneumotachometer fitted toa face mask. Commonly calculated pulmonary function indices include lung resistance and dynamic compliance [17]. During disease exacerbation, increases in pleural pressure reflect increases in pulmonary resistance and decreases in dynamic compliance, associated with airway narrowing and changes in rates of airflow [18]. While this form of conventional pulmonary function testing represents the gold standard in the re- search setting, drawbacks include lack of commercially avail- able systems, expense of equipment, limited usefulness in a “field” setting, need for a relatively invasive intraesophageal balloon catheter, and poor sensitivity for detecting mild to moderate airway obstruction [17]. Pulmonary function testing can also be used to assess airway hyperreactivity by using escalating doses of inhalant histamine or methacholine to induce bronchoconstriction. Horses with sEAS have increased airway reactivity during disease exacerbation and mild reactivity during disease remission [19], which is similar to methacholine challenges in the diagnosis of occupational asthma in humans. The most common ancillary diagnostic for sEAS is airway endoscopy. Visual endoscopic findings consistent with the diagnosis of sEAS include increased tracheal mucus and tra- cheal septum thickness [20]. Endoscopic lavage provides sampling of secretions from the tracheal lumen and lower airways. An increase in neutrophil percentage of tracheal as- pirates has been shown to correlate with inflammatory status of the lower airway [8, 21], but BALF cytology is the preferred sample for diagnosing and monitoring sEAS [11, 22]. Although BALF is rarely obtained from humans with asthma, it is relatively easy to obtain and is invaluable for veterinarians diagnosing and monitoring equine patients “on the farm,” without access to pulmonary function tests. Several studies support the positive correlation between clinical signs, BALF differential cell counts, and airway obstruction and hyperresponsiveness in horses with sEAS [16, 23], although a sub-phenotype of “paucigranulocytic” sEAS horses with severe clinical signs but < 20% neutrophils on BALF has been recently described [24]. For reference, normal horses typically have < 6% neutrophils, < 2% mast cells, < 0.1% eosinophils, 50–70% alveolar macrophages, and 30–50% lymphocytes, while horses with sEAS have a BALF neutrophil percentage of 20–25% and higher (with a concomitant decrease in macrophage percentage) [11], which can remain persistently elevated even during periods of asthma remission [25, 26] and glucocorticoid therapy [27]. Of note, this predominance of neutrophil influx in sEAS is a distinguishing feature separat- ing it from eosinophilic asthma phenotypes in humans.

Environmental Exposures

In general, the etiology of asthma involves a complex interaction between environmental and genetic factors that is incompletely understood, in both humans and horses. In agriculture-exposed persons with asthma and horses with asthma, the common environmental exposure recognized to play a pivotal role in disease development and progression is exposure to airborne organic dust. Airborne organic dusts are complex, and comprised of ultrafine particles, noxious gases, endotoxin, β-D-glucans, fungi, molds, and allergens [28–30]. Interestingly, grass pollens can also trigger asthma symptoms for a subset of sEAS horses with “pasture asthma,” which occurs in adult horses housed on grass pastures in the south-eastern USA or UK, during periods of high heat and humidity [31]. Due to typical management strategies, horses are rou- tinely exposed to airborne organic dust via stabling [32–34] and hay-feeding [35–38]. Exposure to “hay” feed is the com- mon route that provides the allergenic/antigenic exposure to mold spores from Aspergillus fumigatus, Saccharopolyspora rectivirgula, and Thermoactinomyces vulgaris in horses [39]. In addition, stable and hay dust contain numerous potentially pro-inflammatory agents including bacterial endotoxin, fungi, mold, peptidoglycan, proteases, forage mites, and β-D-glucans [40–42]. Various controlled challenge and exposure studies have provided insight into the pulmonary function and lower airway inflammation in response to organic dust components in normal versus sEAS horses. Because it is well-recognized that horse stables can have high concentrations of airborne endotoxin [43], and endotoxin exposure has been linked with severity of asthma in humans [44], studies by Pirie et al. examined the acute airway inflammatory effects of increasing doses of inhaled endotoxin (20, 200, and 2000 μg of soluble Salmonella typhimurium Ra60 lipopolysaccharide) on control and sEAS horses in remission [45]. Endotoxin inhalation induced a dose-dependent increase in neutrophilic airway inflammation in both control and sEAS horses, with sEAS horses demonstrating greater sensitivity to endotoxin exposure, even though they were asymptomatic at the time of exposure. In sEAS horses as compared to control horses, inhalation challenge with 2000 μg endotoxin increased lung resistance at 50 and 75% tidal vol- ume. Horses with sEAS also experienced significant BALF neutrophilia at a lower dose of endotoxin (20 μg) compared to control horses (200 μg).

To further understand the respiratory response parameters following exposure challenges more representative of natural horse exposures, Pirie et al. challenged control and sEAS horses with 5 h of hay/straw exposure and measured both respiratory parameters and respirable airborne endotoxin concentrations. This challenge protocol exposed horses to a biologically active respirable dust endotoxin dose of 0.18 μg and a biologically active total dust endotoxin dose of 7.44 μg. Despite these doses of endotoxin being considerably lower than the thresholds (i.e., 20 μg) for inhaled endotoxin-induced lung inflammation and dysfunction in previous studies, the horses with sEAS had sig- nificantly increased BALF neutrophil influx and increased tra- cheal secretions at 6 and 24 h following hay/straw exposure compared to baseline, and compared to control horses at 6 and 24 h [45].

Pirie and colleagues (2003) further investigated the relative contribution of inhaled LPS and organic dust particulates in inducing asthma symptoms in sEAS horses. Nebulized hay dust suspension (HDS) challenges, with and without LPS depletion, demonstrated that LPS depletion attenuated HDS-induced air- way neutrophilia and dysfunction and adding LPS back to depleted HDS reestablished the HDS-induced symptomatic air- way response. Moreover, the airway inflammatory response to LPS added to LPS-depleted HDS was of greater magnitude than LPS alone, confirming the synergistic effects of LPS plus other hay dust components. Similar studies have been conducted in humans. Sundblad and colleagues challenged farmers and non-farmers (control subjects) to pure endotoxin and pig barn dust and demonstrated that the barn dust exposure elicited a much stronger pro-inflammatory stimulus than that of the endotoxin challenge even though the pure endotoxin dose challenge was 200-fold higher than the endotoxin concentration determined in the dust exposure [46]. Collectively, these studies underscore the complexity of dust and that the airway inflammatory consequences cannot be ascribed to a single agent.

Immunopathogenesis

Similar to the delayed response exhibited by humans with “non-allergic” occupational asthma, horses with asthma syndrome also have a delayed airway response following acute exposure to airborne “triggers” that is often likened to a type III hypersensitivity response [47]. Within 4–6 h of exposure, affected horses experience a significant increase in airway neutrophils [48, 49], as well as neutrophil-derived mediators of inflammation including increased respiratory burst activity and neutrophil elastase [49], myeloperoxidase [50], neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) [51, 52], and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-8, MMP-9, and MMP-13) [53, 54]. In addition to airway neutrophil influx, exposure to airborne triggers also increases pro-inflammatory cytokines and inflammatory regulators in BALF cells and supernatant; however, results are inconsistent on whether the altered cytokines support a T-helper (Th)1-, Th2-, Th17-weighted, or mixed response. For example, Padoan et al. reported increased gene expression of interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-8, Toll-like receptor (TLR)4, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 and nuclear factor (NF)-kβ, and trends (not significant) towards increased IL-17 and interferon (IFN)-γ in the bronchial biopsies and BALF of sEAS horses as compared to healthy horses [55]. Additional studies support increases in IL-8, TNF-α, and IL-8 in horses with either symptomatic sEAS or horses with sEAS following exposure challenges [56–61]. In contrast, others have demonstrated either a mixed Th1/Th2 type cytokine response characterized by increased IL-4 and IL-13 (Th2), and IFN-γ (Th1) mRNA, but not IL-5 in horses with sEAS [62] or a potentiated Th2-weighted immune response with increased IL-4 and IL-5 gene expression, but not IFN-γ, expressing lymphocytes in sEAS vs. control horses following a 24-h hay challenge [63]. Evidence also exists for a Th1/Th17 response with a 5-day hay challenge eliciting increased messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of IL-1β, IL-6R, IL-18, and IL-23 that significantly correlated to neutrophil percent- ages, and clinical and tracheal mucus score [38]. Debrue et al. demonstrated that IL-17 mRNA was significantly increased in BAL isolated cells from sEAS, but not control horses, following a 35-day moldy hay challenge [64]. Interestingly, Korn et al. analyzed gene expression profiles, selected cytokine network analysis and immunohistochemical staining of mediastinal lymph nodes from horses with chronic, active sEAS, and concluded that the chronic airway inflammation in these horses is driven by an IL-17/NF-κB response [65]. Evidence for an IL-17-driven response in sEAS is particularly significant because of the demonstrated increase in IL-17 ex- pressing T cells in peripheral blood of agricultural workers and increased IL-17 protein in lung homogenates from mice following repetitive inhalation exposure to organic dust extracts [66].

Similar to human and murine asthma studies, regulatory T cells (Tregs) are recognized as playing an important role in the resolution of lung inflammation in horses with sEAS. In sEAS horses challenged with moldy hay contaminated with Aspergillus fumigatus, Henrὶquez et al. determined that the per- centage of cluster of differentiation (CD)4+, CD25high, Forkhead Box (Fox)p3+ cells in BALF significantly increased in horses with active disease compared to the same horses in remission [67]. As a potential therapy to activate Tregs and restore Th cell balance [68], sEAS horses treated with inhaled nanoparticle-bound cytosine-phosphate-guanosine (CpG- GNP) immunotherapy [69] showed significant improvement in all clinical and pulmonary parameters, concomitant with a decrease in BALF IL-4, IL-17, and IFN-γ cytokines, as well as reduced CD4+ IL-8, T-box transcription factor (T-bet), and GATA transcription factor (GATA)-3 mRNA expression with- out changes in IL-10, or CD4+ Foxp3, or TGF-β gene expression.

There are differences between asthma in humans and sEAS in horses. Although organic dust exposure is known to in- crease IL-6 in BALF of humans [70], evidence for a role for IL-6 in sEAS is conflicting. Several studies have failed to find an IL-6 signal in sEAS [60, 61, 71, 72], but others report an increase in IL-6R mRNA during sEAS exacerbation [38] and a positive correlation of IL-6 with IL-8 expression in BAL cells following hay challenge [73]. Another difference is that eosinophils are not a feature of the airway inflammation in horses with sEAS [74], and an early phase (10–20 min) hista- mine release and bronchoconstriction response to inhaled dust does not occur in diseased horses [75]. Further, while there is evidence of a Th2-weighted response in some sEAS horses, the role of immunoglobulin (Ig)E in sEAS remains uncertain [7]. In a small group of 14 adult horses, there were increases in serum-specific IgE against mites, but not molds, in sEAS-affected horses [76]. In comparison, Kȕnzle et al. reported that serum IgE levels against mold extracts were significantly elevated in sEAS vs. healthy horses, but the ranges of mold-specific serum IgE levels overlapped considerably between diseased and clinically healthy animals [77]. No difference in IgE cell staining has also been demonstrated on immuno- histochemistry of lung biopsies from sEAS horses vs. control [78]. There is also evidence demonstrating a lack of associations between serum IgE and sulfidoleukotriene release assay, intradermal testing, and sEAS disease status, suggesting that IgE-mediated reactions are not central to the pathophysiology of sEAS [79, 80].

Like humans with organic dust-induced asthma [30], horses with sEAS also have evidence of chronic, systemic immune system activation. Markers of chronic activation in horses with sEAS, usually during exacerbation, include increased serum levels of IL-13, IFN-γ, haptoglobin, and serum amyloid A (SAA); circulating immune complexes; activated platelets; and enhanced NET formation of increased low-density neutrophils but with low neutrophil bactericidal activity [81].

Histopathology

There are significant parallels between the pathophysiology of sEAS and asthma in humans [7]. During an asthmatic “episode,” sEAS horses experience increased airflow obstruction as a consequence of bronchospasms, mucus plugging and inflammatory cell infiltrates [13], airway hyperresponsiveness [82], and lung remodeling [83]. The histological changes are marked by goblet cell hyperplasia/metaplasia, increased airway smooth muscle, increased peribronchiolar elastic system fibers, adventitial inflammation, peribronchiolar fibrosis, and mucus occlusion of airways [31]. Airway inflammation is greater in symptomatic vs. asymptomatic sEAS and control horses, and neutrophil infiltrates in the airway are more frequently detected in sEAS cases compared with control horses [24]. This finding is consistent with previous descriptions of neutrophilic bronchiolitis as the primary lesion in sEAS [84], although lymphocytic and mastocytic infiltrate of the adventitia and bronchioles is also described [85]. The predominance of neutrophilic inflammation in sEAS horses as opposed to eosinophilic inflammation draws attention to the potential ref- erence to asthma and COPD overlap (ACO) in humans [86]. Thus, it is conceivable that horses, who develop asthma in their natural environment and experience life-long symptoms that can become difficult to manage, could also be modeled to provide insight into ACO. Furthermore, sEAS in horses reflect the non-allergic, organic dust-induced “occupational” asthma, where neutrophils are a hallmark of the inflammatory adaptation response [30].

Recently, gene expression profiling [65, 87–90] and proteomics [91, 92] of airway samples have been employed in attempts to unravel the links between immune system dysregulation and airway remodeling in sEAS. In sEAS horses maintained in a low-dust environment, clinical signs of asthma abate and lung inflammatory cellular and mediator indices normalize; however, there is evidence of ongoing subclinical inflammation in the form of persistent peripheral airway obstruction, airway smooth muscle cell turnover, and higher NF-κB activity [93]. The reversibility of airway smooth muscle (ASM) remodeling has also been recently examined, with multiple studies indicating that airway remodeling is partially reversible (~ 30%) with antigen avoidance and/or inhaled corticosteroids [94, 95].

Therapeutic and Translation Approaches

Environmental management through decreased exposure to airborne triggers is a mainstay approach to limit symptoms of asthmatic disease in both humans exposed to organic dust environments and horses. There is clear evidence that eliminating dust exposure through minimum dust bedding or pasture housing, and low-dust forage, is key to alleviating asthma symptoms and normalizing pulmonary function and airway reactivity in sEAS horses [19]. This point serves as a distinct advantage of horses as a translational asthma model in that disease remission is easily achieved by moving horses from a stabled environment to pasture and cessation of hay- feeding. Thus, when disease exacerbation is indicated for re- search purposes, a return to a dusty stable environment or hay challenge will induce rapid onset of neutrophilic lower airway inflammation, bronchospasm, and mucus hypersecretion. When environmental antigen/allergen elimination is not a feasible disease management option, drug therapies include local or systemic corticosteroids and bronchodilators. Because horses are obligate nasal breathers, facemasks for drug nebulization or aerosolization, similar to those used for pediatric patients, are commercially available. Investigations into therapeutic translational research approaches is another potential advantage of the sEAS model, particularly as a preclinical model where evidence from mouse studies often falls short of predicting drug efficacy in human asthma patients [96]. In fact, a recent meta-analysis identified many similarities in efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids and bronchodilators in the treatment of sEAS and asthma in humans [97]. Because of the relatively long lifespan (i.e., 25–30 years), horses offer an advantage in terms of repeated sampling over time. In addition, there is a relative ease and abundance of sample collection, as jugular venipuncture provides access to large quantities of circulating immune cells for experimental studies. Sedated-standing bronchoscopy provides means to collect tracheal wash aspirates, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, bronchial epithelial brushings, and endobronchial biopsies. Peripheral lung biopsy and pulmonary function tests can also be per- formed to interrogate asthma-associated airway remodeling and pulmonary mechanics.

There are complicating factors to using horses for translational research. Horses are large and long-lived, which can increase the costs associated with drugs and housing. Asthmatic horses need to be monitored and handled by ex- perts in veterinary health, requiring important partnering con- siderations and availability. Nonetheless, this animal model represents an opportunity for collaboration, and in lieu of live horse access, an equine respiratory tissue biobank (http://www.ertb.ca) provides investigators ready access to banked tissue samples.

Conclusions

There are several parallels in disease risk, pathology, and clinical signs between organic dust-induced asthma in agricultural works and sEAS in horses. There also remain many unanswered questions regarding what features allow some horses or some agricultural workers to adapt to the inhaled antigens in their environment, while others succumb to an exaggerated and chronic activation of the pulmonary and systemic immune system. Comparative research in these two species, complemented by studies in more traditional murine models, will likely contribute improved knowledge and novel treatment strategies that could ultimately benefit the respiratory health of both horses and humans. Moreover, based upon the evidence provided of striking similarities of the naturally occurring asthma in horses and agriculture organic dust expo- sure in exposed workers, studies with horses could be a powerful translational model to further elucidate the environmental and immunologic factors contributing to organic dust-induced asthma in humans.

Funding Information:

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R01ES019325 to JAP).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent: This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Hamilton D, Lehman H. Asthma Phenotypes as a Guide for Current and Future Biologic Therapies. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019. Jul. 10.1007/s12016-019-08760-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly KJ, Poole JA. Pollutants in the workplace: effect on occupational asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(6):2014–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazurek JM, White GE, Rodman C, Schleiff PL. Farm work- related asthma among US primary farm operators. J Agromed. 2015;20(1):31–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazan MR, Svatek J, Maranda L, Christiani D, Ghio A, Nadeau J, et al. Questionnaire assessment of airway disease symptoms in equine barn personnel. Occup Med (Lond). 2009;59(4):220–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackiewicz B, Prazmo Z, Milanowski J, Dutkiewicz J, Fafrowicz B. Exposure to organic dust and microorganisms as a factor affect- ing respiratory function of workers of purebred horse farms. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 1996;64(Suppl 1):19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tutluoglu B, Atiş S, Anakkaya AN, Altug E, Tosun GA, Yaman M. Sensitization to horse hair, symptoms and lung function in grooms. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32(8):1170–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bond S, Léguillette R, Richard EA, Couetil L, Lavoie JP, Martin JG, et al. Equine asthma: integrative biologic relevance of a recently proposed nomenclature. J Vet Intern Med. 2018;32(6):2088–98 Review of the biological relevance of equine asthma syndrome as a translational model for phenotypes of human asthma.

- 8.Wysocka B, Kluciński W. Cytological evaluation of tracheal aspirate and broncho-alveolar lavage fluid in comparison to endoscopic assessment of lower airways in horses with recurrent airways obstruc- tion or inflammatory airway disease. Pol J Vet Sci. 2015;18(3):587–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson NE, Berney C, Eberhart S, de Feijter-Rupp HL, Jefcoat AM, Cornelisse CJ, et al. Coughing, mucus accumulation, airway obstruction, and airway inflammation in control horses and horses affected with recurrent airway obstruction. Am J Vet Res. 2003;64(5):550–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miskovic M, Couetil LL, Thompson CA. Lung function and airway cytologic profiles in horses with recurrent airway obstruction maintained in low-dust environments. J Vet Intern Med. 2007;21(5):1060–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Couetil LL, Cardwell JM, Gerber V, Lavoie JP, Leguillette R, Richard EA. Inflammatory airway disease of horses-revised con- sensus statement. J Vet Intern Med. 2016;30(2):503–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavoie JP. Is the time primed for equine asthma? Equine Vet Educ. 2015;27:225–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marinkovic D, Aleksic-Kovacevic S, Plamenac P. Cellular basis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in horses. Int Rev Cytol. 2007;257:213–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffman AM, Mazan MR, Ellenberg S. Association between bronchoalveolar lavage cytologic features and airway reactivity in hors- es with a history of exercise intolerance. Am J Vet Res. 1998;59(2): 176–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rettmer H, Hoffman AM, Lanz S, Oertly M, Gerber V. Owner-reported coughing and nasal discharge are associated with clinical findings, arterial oxygen tension, mucus score and bronchoprovocation in horses with recurrent airway obstruction in a field setting. Equine Vet J. 2015;47(3):291–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tilley P, Sales Luis JP, Branco FM. Correlation and discriminant analysis between clinical, endoscopic, thoracic X-ray and broncho- alveolar lavage fluid cytology scores, for staging horses with recur- rent airway obstruction (RAO). Res Vet Sci. 2012;93(2):1006–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman AM. Respiratory applications for the future: one perspective. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2001;17(2):335–49 viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson NE, Derksen FJ, Olszewski M, Berney C, Boehler D, Matson C, et al. Determinants of the maximal change in pleural pressure during tidal breathing in COPD-affected horses. Vet J. 1999;157(2):160–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vandenput S, Votion D, Duvivier DH, Van Erck E, Anciaux N, Art T, et al. Effect of a set stabled environmental control on pulmonary function and airway reactivity of COPD affected horses. Vet J. 1998;155(2):189–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wysocka B, Kluciński W. Usefulness of the assessment of dis- charge accumulation in the lower airways and tracheal septum thickening in the differential diagnosis of recurrent airway obstruction (RAO) and inflammatory airway disease (IAD) in the horse. Pol J Vet Sci. 2014;17(2):247–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rossi H, Virtala AM, Raekallio M, Rahkonen E, Rajamäki MM, Mykkänen A. Comparison of tracheal wash and bronchoalveolar lavage cytology in 154 horses with and without respiratory signs in a referral hospital over 2009–2015. Front Vet Sci. 2018;5:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffman AM. Bronchoalveolar lavage: sampling technique and guidelines for cytologic preparation and interpretation. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2008;24(2):423–35 vii-viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Derksen FJ, Scott JS, Miller DC, Slocombe RF, Robinson NE. Bronchoalveolar lavage in ponies with recurrent airway obstruction (heaves). Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;132(5):1066–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bullone M, Joubert P, Gagné A, Lavoie JP, Hélie P. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid neutrophilia is associated with the severity of pulmonary lesions during equine asthma exacerbations. Equine Vet J. Sep;50(5):609–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis KU, Sheats MK. Bronchoalveolar lavage cytology characteristics and seasonal changes in a herd of pastured teaching horses. Front Vet Sci. 2019;6:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jean D, Vrins A, Beauchamp G, Lavoie JP. Evaluation of variations in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in horses with recurrent airway obstruction. Am J Vet Res. 2011;72(6):838–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lavoie JP, Leclere M, Rodrigues N, Lemos KR, Bourzac C, Lefebvre-Lavoie J, et al. Efficacy of inhaled budesonide for the treat- ment of severe equine asthma. Equine Vet J. 2019;51(3):401–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ivester KM, Couëtil LL, Moore GE, Zimmerman NJ, Raskin RE. Environmental exposures and airway inflammation in young thor- oughbred horses. J Vet Intern Med. 2014;28(3):918–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holcombe SJ, Jackson C, Gerber V, Jefcoat A, Berney C, Eberhardt S, et al. Stabling is associated with airway inflammation in young Arabian horses. Equine Vet J. 2001;33(3):244–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poole JA, Romberger DJ. Immunological and inflammatory responses to organic dust in agriculture. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12(2):126–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ferrari CR, Cooley J, Mujahid N, Costa LR, Wills RW, Johnson ME, et al. Horses with pasture asthma have airway remodeling that is characteristic of human asthma. Vet Pathol. 2018;55(1):144–58 Study quantifying the histological evidence of airway remodeling in equine asthma syndrome relevant to human asthma.

- 32.Clements JM, Pirie RS. Respirable dust concentrations in equine stables. Part 1: validation of equipment and effect of various management systems. Res Vet Sci. 2007;83(2):256–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berndt A, Derksen FJ, Edward RN. Endotoxin concentrations with- in the breathing zone of horses are higher in stables than on pasture. Vet J. 2010;183(1):54–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wålinder R, Riihimäki M, Bohlin S, Hogstedt C, Nordquist T, Raine A, et al. Installation of mechanical ventilation in a horse stable: effects on air quality and human and equine airways. Environ Health Prev Med. 2011;16(4):264–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clarke AF, Madelin T. Technique for assessing respiratory health hazards from hay and other source materials. Equine Vet J. 1987;19(5):442–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clements JM, Pirie RS. Respirable dust concentrations in equine stables. Part 2: the benefits of soaking hay and optimising the environment in a neighbouring stable. Res Vet Sci. 2007;83(2):263–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vandenput S, Istasse L, Nicks B, Lekeux P. Airborne dust and aeroallergen concentrations in different sources of feed and bedding for horses. Vet Q. 1997;19(4):154–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orard M, Hue E, Couroucé A, Bizon-Mercier C, Toquet MP, Moore-Colyer M, et al. The influence of hay steaming on clinical signs and airway immune response in severe asthmatic horses. BMC Vet Res. 2018;14(1):345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wasko AJ, Barkema HW, Nicol J, Fernandez N, Logie N, Léguillette R. Evaluation of a risk-screening questionnaire to detect equine lung inflammation: results of a large field study. Equine Vet J. 2011;43(2):145–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siegers EW, Anthonisse M, van Eerdenburg FJCM, van den Broek J, Wouters IM, Westermann CM. Effect of ionization, bedding, and feeding on air quality in a horse stable. J Vet Intern Med. 2018;32(3):1234–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pirie RS. Recurrent airway obstruction: a review. Equine Vet J. 2014;46(3):276–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elfman L, Riihimäki M, Pringle J, Wålinder R. Influence of horse stable environment on human airways. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2009;4:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGorum BC, Ellison J, Cullen RT. Total and respirable airborne dust endotoxin concentrations in three equine management sys- tems. Equine Vet J. 1998;30(5):430–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shamsollahi HR, Ghoochani M, Jaafari J, Moosavi A, Sillanpää M, Alimohammadi M. Environmental exposure to endotoxin and its health outcomes: a systematic review. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019;174:236–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horohov DW, Beadle RE, Mouch S, Pourciau SS. Temporal regulation of cytokine mRNA expression in equine recurrent airway obstruction. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2005;108(1–2):237–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cordeau ME, Joubert P, Dewachi O, Hamid Q, Lavoie JP. IL-4, IL- 5 and IFN-gamma mRNA expression in pulmonary lymphocytes in equine heaves. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2004;97(1–2):87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Debrue M, Hamilton E, Joubert P, Lajoie-Kadoch S, Lavoie JP. Chronic exacerbation of equine heaves is associated with an in- creased expression of interleukin-17 mRNA in bronchoalveolar lavage cells. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2005;105(1–2):25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Korn A, Miller D, Dong L, Buckles EL, Wagner B, Ainsworth DM. Differential gene expression profiles and selected cytokine protein analysis of mediastinal lymph nodes of horses with chronic recur- rent airway obstruction (RAO) support an interleukin-17 immune response. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0142622. Study provding evidence for Th17-weighted immune response in severe EAS.

- 49.Robbe P, Spierenburg EA, Draijer C, Brandsma CA, Telenga E, van Oosterhout AJ, et al. Shifted T-cell polarisation after agricultural dust exposure in mice and men. Thorax. 2014;69(7):630–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Henríquez C, Perez B, Morales N, Sarmiento J, Carrasco C, Morán G, et al. Participation of T regulatory cells in equine recurrent air- way obstruction. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2014;158(3–4): 128–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kündig TM, Klimek L, Schendzielorz P, Renner WA, Senti G, Bachmann MF. Is the allergen really needed in allergy immunotherapy? Curr Treat Options Allergy. 2015;2(1):72–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Klier J, Bartl C, Geuder S, Geh KJ, Reese S, Goehring LS, et al. Immunomodulatory asthma therapy in the equine animal model: A dose-response study and evaluation of a long-term effect. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2019. Sep;7(3):130–149. Study demonstrating efficacy of inhaled immunomodulatory therapy in horses with naturally occuring sEAS.

- 53.Von Essen SG, Robbins RA, Thompson AB, Ertl RF, Linder J, Rennard S. Mechanisms of neutrophil recruitment to the lung by grain dust exposure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138(4):921–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laan TT, Bull S, Pirie R, Fink-Gremmels J. The role of alveolar macrophages in the pathogenesis of recurrent airway obstruction in horses. J Vet Intern Med. 2006;20(1):167–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Riihimäki M, Raine A, Pourazar J, Sandström T, Art T, Lekeux P, et al. Epithelial expression of mRNA and protein for IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-alpha in endobronchial biopsies in horses with recurrent airway obstruction. BMC Vet Res. 2008;4:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Riihimäki M, Raine A, Art T, Lekeux P, Couëtil L, Pringle J. Partial divergence of cytokine mRNA expression in bronchial tissues com- pared to bronchoalveolar lavage cells in horses with recurrent air- way obstruction. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2008;122(3–4): 256–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dubuc J, Lavoie JP. Airway wall eosinophilia is not a feature of equine heaves. Vet J. 2014;202(2):387–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Deaton CM, Deaton L, Jose-Cunilleras E, Vincent TL, Baird AW, Dacre K, et al. Early onset airway obstruction in response to organic dust in the horse. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2007;102(3):1071–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Niedzwiedz A, Jaworski Z, Kubiak K. Serum concentrations of allergen-specific IgE in horses with equine recurrent airway obstruction and healthy controls assessed by ELISA. Vet Clin Pathol. 2015;44(3):391–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Künzle F, Gerber V, Van Der Haegen A, Wampfler B, Straub R, Marti E. IgE-bearing cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and allergen-specific IgE levels in sera from RAO-affected horses. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med. 2007;54(1):40–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van der Haegen A, Künzle F, Gerber V, Welle M, Robinson NE, Marti E. Mast cells and IgE-bearing cells in lungs of RAO-affected horses. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2005;108(3–4):325–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tahon L, Baselgia S, Gerber V, Doherr MG, Straub R, Robinson NE, et al. In vitro allergy tests compared to intradermal testing in horses with recurrent airway obstruction. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2009;127(1–2):85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Scharrenberg A, Gerber V, Swinburne JE, Wilson AD, Klukowska- Rötzler J, Laumen E, et al. IgE, IgGa, IgGb and IgG(T) serum antibody levels in offspring of two sires affected with equine recur- rent airway obstruction. Anim Genet. 2010;41(Suppl 2):131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Niedźwiedź A, Borowicz H, Kubiak K, Nicpoń J, Skrzypczak P, Jaworski Z, et al. Evaluation of serum cytokine levels in recurrent airway obstruction. Pol J Vet Sci. 2016;19(4):785–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Matusovsky OS, Kachmar L, Ijpma G, Bates G, Zitouni N, Benedetti A, et al. Peripheral airway smooth muscle, but not the trachealis, is hypercontractile in an equine model of asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;54(5):718–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Robinson NE, Derksen FJ, Olszewski MA, Buechner-Maxwell VA. The pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease of hors- es. Br Vet J. 1996;152(3):283–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Uberti B, Morán G. Role of neutrophils in equine asthma. Anim Health Res Rev. 2018. Jun;19(1):65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Léguillette R Recurrent airway obstruction–heaves. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2003;19(1):63–86 vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Krishnan JA, Nibber A, Chisholm A, Price D, Bateman ED, Bjermer L, et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Asthma-COPD Overlap in Routine Primary Care Practices. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019. Sep;16(9):1143–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tessier L, Côté O, Clark ME, Viel L, Diaz-Méndez A, Anders S, et al. Impaired response of the bronchial epithelium to inflammation characterizes severe equine asthma. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1): 708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tessier L, Côté O, Clark ME, Viel L, Diaz-Méndez A, Anders S, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis of the bronchial epithelium implicates contribution of cell cycle and tissue repair processes in equine asthma. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):16408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lavoie JP, Lefebvre-Lavoie J, Leclere M, Lavoie-Lamoureux A, Chamberland A, Laprise C, et al. Profiling of differentially expressed genes using suppression subtractive hybridization in an equine model of chronic asthma. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pacholewska A, Kraft MF, Gerber V, Jagannathan V. Differential Expression of Serum MicroRNAs Supports CD4??? T Cell Differentiation into Th2/Th17 Cells in Severe Equine Asthma. Genes (Basel). 2017. Dec 2 12;8(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bright LA, Dittmar W, Nanduri B, McCarthy FM, Mujahid N, Costa LR, et al. Modeling the pasture-associated severe equine asthma bronchoalveolar lavage fluid proteome identifies molecular events mediating neutrophilic airway inflammation. Vet Med (Auckl). 2019;10:43–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vargas A, Roux-Dalvai F, Droit A, Lavoie JP. Neutrophil-derived exosomes: a new mechanism contributing to airway smooth muscle remodeling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;55:450–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Miskovic M, Couëtil LL, Thompson CA. Lung function and airway cytologic profiles in horses with recurrent airway obstruction main- tained in low-dust environments. J Vet Intern Med. 2007;21(5): 1060–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bullone M, Vargas A, Elce Y, Martin JG, Lavoie JP. Fluticasone/salmeterol reduces remodelling and neutrophilic inflammation in severe equine asthma. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):8843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Leclere M, Lavoie-Lamoureux A, Joubert P, Relave F, Setlakwe EL, Beauchamp G, et al. Corticosteroids and antigen avoidance decrease airway smooth muscle mass in an equine asthma model. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;47(5):589–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lange-Consiglio A, Stucchi L, Zucca E, Lavoie JP, Cremonesi F, Ferrucci F. Insights into animal models for cell-based therapies in translational studies of lung diseases: is the horse with naturally occurring asthma the right choice? Cytotherapy. 2019;21(5):525–34 Recent review highlighting the potential value of the equine asthma model for the study of cell-based therapies for lung disease.

- 80.Calzetta L, Roncada P, di Cave D, Bonizzi L, Urbani A, Pistocchini E, et al. Pharmacological treatments in asthma-affected horses: a pair-wise and network meta-analysis. Equine Vet J. 2017;49(6): 710–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Niedźwiedź A, Borowicz H, Kubiak K, Nicpoń J, Skrzypczak P, Jaworski Z, et al. Evaluation of serum cytokine levels in recurrent airway obstruction. Pol J Vet Sci. 2016;19(4):785–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Matusovsky OS, Kachmar L, Ijpma G, Bates G, Zitouni N, Benedetti A, et al. Peripheral airway smooth muscle, but not the trachealis, is hypercontractile in an equine model of asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;54(5):718–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Robinson NE, Derksen FJ, OlszewskiMA, Buechner-Maxwell VA. The pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease of horses. Br Vet J. 1996;152(3):283–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Uberti B, Morán G. Role of neutrophils in equine asthma. Anim Health Res Rev. 2018. Jun;19(1):65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Léguillette R Recurrent airway obstruction–heaves. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2003;19(1):63–86 vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Krishnan JA, Nibber A, Chisholm A, Price D, Bateman ED, Bjermer L, et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Asthma-COPD Overlap in Routine Primary Care Practices. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019. Sep;16(9):1143–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tessier L, Côté O, Clark ME, Viel L, Diaz-Méndez A, Anders S, et al. Impaired response of the bronchial epithelium to inflammation characterizes severe equine asthma. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1): 708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tessier L, Côté O, Clark ME, Viel L, Diaz-Méndez A, Anders S, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis of the bronchial epithelium implicates contribution of cell cycle and tissue repair processes in equine asthma. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):16408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lavoie JP, Lefebvre-Lavoie J, Leclere M, Lavoie-Lamoureux A, Chamberland A, Laprise C, et al. Profiling of differentially expressed genes using suppression subtractive hybridization in an equine model of chronic asthma. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pacholewska A, Kraft MF, Gerber V, Jagannathan V. Differential Expression of Serum MicroRNAs Supports CD4??? T Cell Differentiation into Th2/Th17 Cells in Severe Equine Asthma. Genes (Basel). 2017. Dec 2 12;8(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bright LA, Dittmar W, Nanduri B, McCarthy FM, Mujahid N, Costa LR, et al. Modeling the pasture-associated severe equine asthma bronchoalveolar lavage fluid proteome identifies molecular events mediating neutrophilic airway inflammation. Vet Med (Auckl). 2019;10:43–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vargas A, Roux-Dalvai F, Droit A, Lavoie JP. Neutrophil-derived exosomes: a new mechanism contributing to airway smooth muscle remodeling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;55:450–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.MiskovicM Couëtil LL, Thompson CA. Lung function and airway cytologic profiles in horses with recurrent airway obstruction maintained in low-dust environments. J Vet Intern Med. 2007;21(5): 1060–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bullone M, Vargas A, Elce Y, Martin JG, Lavoie JP. Fluticasone/salmeterol reduces remodelling and neutrophilic inflammation in severe equine asthma. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):8843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Leclere M, Lavoie-Lamoureux A, Joubert P, Relave F, Setlakwe EL, Beauchamp G, et al. Corticosteroids and antigen avoidance decrease airway smooth muscle mass in an equine asthma model. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;47(5):589–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lange-Consiglio A, Stucchi L, Zucca E, Lavoie JP, Cremonesi F, Ferrucci F. Insights into animal models for cell-based therapies in translational studies of lung diseases: is the horse with naturally occurring asthma the right choice? Cytotherapy. 2019;21(5):525–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Calzetta L, Roncada P, di Cave D, Bonizzi L, Urbani A, Pistocchini E, et al. Pharmacological treatments in asthma-affected horses: a pair-wise and network meta-analysis. Equine Vet J. 2017;49(6): 710–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]