Abstract

Introduction

Noninvasive biomarkers that reflect tubular health and allow early recognition of accelerated graft fibrosis development are warranted. Serum uromodulin (sUmod) and urinary epidermal growth factor (uEGF) originate from kidney tubules and may reflect functional nephron mass. The aim of this study was to investigate the associations between sUmod and uEGF with measured glomerular filtration rate (mGFR) and kidney allograft interstitial fibrosis percentage (IF%) score.

Methods

sUmod and uEGF measurements, mGFR by iohexol-clearance and kidney allograft biopsies were obtained from kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) included in the Omega-3 fatty acids in Renal Transplantation (ORENTRA) trial at 8 weeks (baseline) and at 1 year after transplantation (end of study). Associations were analyzed with univariable and multivariable linear regression.

Results

Ninety patients at baseline and 48 patients at end of study had complete study variable assessments. uEGF normalized to urinary creatinine (uEGF/Cr) was associated with mGFR both at baseline (standardized β-coefficient [Std. β-coeff] = 0.457 [p = <0.001]) and at end of study (Std. β-coeff = 0.637 [p = <0.001]). sUmod was only associated with mGFR at end of study (Std. β-coeff = 0.443 [p = 0.002]). uEGF/Cr, sUmod, and mGFR were associated with graft IF% score both at baseline (Std. β-coeff = −0.349 [p = 0.001], −0.274 [p = 0.009] and −0.289 [p = 0.006], respectively) and at end of study (Std. β-coeff = −0.365 [p = 0.011], −0.347 [p = 0.016] and −0.405 [p = 0.004], respectively). The results remained largely unchanged in multivariable analysis.

Conclusion

uEGF/Cr and sUmod were associated with mGFR and graft IF% score. Our results indicate a possible role of uEGF/Cr and sUmod in the follow-up of KTRs.

Keywords: Uromodulin, Epidermal growth factor, Interstitial fibrosis, Measured glomerular filtration rate, Kidney transplantation

Introduction

Progression of fibrosis due to chronic alloimmune response and immunosuppressant side effects is the leading because of late kidney transplant failure [1, 2]. In a clinical setting, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), either based on creatinine or cystatin C, is used to monitor change in graft function over time. However, eGFR has wide margins of error in determining graft function in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) [3], and early stages of fibrosis is not reflected by changes in eGFR [1, 4]. Graft fibrosis progression can be reliably monitored with measured GFR (mGFR) [4], but it is time-consuming to perform and may not be feasible in routine clinical use. There is a need for noninvasive biomarkers which adequately reflect tubular health and allow early recognition of accelerated development of fibrosis with comparable precision as mGFR.

Uromodulin has been proposed as a biomarker for estimating functional tubular mass [5, 6]. Also known as Tamm-Horsfall protein, it is a kidney-specific glycoprotein synthesized at the thick ascending limb of loop of Henle and, to a lesser extent, at the distal convoluted tubule (DCT) [7, 8]. Biological roles of uromodulin include sodium handling, blood pressure regulation, protection against urinary tract infections, inhibition of kidney stone formation, and immune homeostasis [9]. Most of it is released into the tubular lumen from the apical membrane of epithelial cells, making uromodulin the most abundant protein secreted in the urine under physiological conditions. A lower amount of this protein is also released from the basolateral side of epithelial cells into the circulation [10]. Both urinary and serum levels of uromodulin have been suggested to reflect the number of intact nephrons [5, 11].

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) is another biomarker which has gained interest as an indicator of tubular function and for assessing kidney disease progression [12, 13, 14, 15]. It is a 53-amino acid polypeptide that is predominantly produced in the kidneys, like uromodulin, in the ascending limb of Henle's loop and the DCT. EGF promotes regeneration of renal tubular cells after injury, and it is involved in regulation of electrolyte transport [16]. High concentrations of EGF can be detected in urine and reflect levels of local production [17]. Previous studies have shown that both serum uromodulin (sUmod) and urinary EGF (uEGF) can predict kidney function decline in the general population and in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) [18, 19]. In addition, levels of sUmod and uEGF are inversely associated with the risk of graft loss in KTRs [20, 21].

This is a post hoc analysis of the “Omega-3 fatty acids in Renal Transplantation (ORENTRA)” trial [22]. Our aim in the present study was to prospectively investigate the associations of sUmod and uEGF with mGFR and interstitial fibrosis percentage (IF%) score in kidney allograft biopsies, 8 weeks post-transplant and 1 year after transplantation.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The ORENTRA trial design has been described in detail [22]. ORENTRA (Clinical.Trials.gov identifier NCT01744067) was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial designed to investigate the effects of marine n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) supplementation on kidney graft function. The study was performed at Oslo University Hospital Rikshospitalet between 2012 and 2015. According to standard procedure for management of KTRs in Norway, a full clinical assessment, including protocol kidney transplant biopsies, are performed 8 weeks post-transplant and repeated 1 year after transplantation at Oslo University Hospital Rikshospitalet. These time points were defined as the baseline and the end of study visits in the ORENTRA trial, respectively. Norwegian KTRs with eGFR >30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 at 8 weeks after transplantation and ≥18 years of age were included. Participants were randomized to either treatment with marine n-3 PUFA ethyl ester (3 capsules of 1 g, ≈2.6 g effective dose of eicosapentaenoic acid plus docosahexaenoic acid, per day) or placebo (extra virgin olive oil, 3 capsules of 1 g per day). The primary endpoint was change in mGFR after 44 weeks of follow-up. Written informed consent for participation was obtained from all patients. The study was approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Norway and the Norwegian Medicines Agency and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the principles of Good Clinical Practice.

Procedures and Measurements

All procedures and measurements were done at the baseline visit 8 weeks post-transplant and repeated at the end of study visit 1 year after transplantation. Fasting blood and urine samples were obtained from study participants in the morning. Samples were centrifuged, frozen, and stored at −80°C at the Renal Physiology Laboratory Biobank at Oslo University Hospital, Rikshospitalet, Norway, until study analyses were performed. Individual fatty acid levels in plasma phospholipids were analyzed by gas chromatography at The Lipid Research Center, Aalborg University Hospital, Denmark, and quantified as weight percentage of total plasma phospholipid fatty acids [23].

mGFR was determined by clearance of iohexol, a nonradioactive X-ray contrast medium widely used for this purpose. Plasma concentration was quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography 2 and 5 h after intravenous injection of 5 mL iohexol [24].

Protocol kidney graft biopsy samples were obtained at baseline and at end of study. The samples were fixed in 4% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and stained with trichrome. Light microscopic evaluation of the biopsy samples was performed semi-quantitatively by two investigators of the ORENTRA trial, blinded for patient identity and clinical data. Only samples with at least 5 glomeruli and sufficient cortical tissue outside scars were included in IF% scoring. Areas with fibrosis were determined at 5% level for each visual field and 1% level for averaged values [25]. There was a high degree of concordance in IF% scores between the investigators, with intra- and inter-observer variability <5% in all but 3 cases [22].

sUmod was measured with a commercial ELISA-kit (Euroimmun, Medizinische Labordiagnostika AG, Lübeck, Germany). uEGF was measured on the Bio-Plex 200TM system using a customized commercial multiplex immunoassay panel (ProcartaPlexTM ThermoFisher Scientific/Invitrogen). Both analyses were performed per manufacturers' instructions in duplicates. To minimize the effect of matrix interference [26] in analysis of uEGF, we performed a pilot-study in advance with four randomly selected urine samples from the study cohort. A dilution factor of 1:10 resulted in the highest measurement values (online suppl. material; see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000521757 for all online suppl. material). uEGF values were normalized to urinary creatinine concentrations (VITROS CREA, Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics). Mean coefficient of variation for all measurements of uEGF was 2% and for sUmod 6%.

Statistical Analysis

Study variables were assessed for normality with Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Shapiro-Wilk tests, and normality plots. The data were reported as mean ± standard deviation for values with normal distribution, as median (interquartile range) for values with non-normal distribution, and as n (percentage) for categorical data. Difference in post-interventional changes of uEGF and sUmod between the marine n-3 PUFA group and the control group was evaluated using analysis of covariance with adjustment for baseline values. Associations between study variables were analyzed with univariable and multivariable linear regression models. The strength of the associations was determined by standardized beta coefficients. Adjustments in the multivariable models were made with predefined clinically relevant variables and marine n-3 PUFA intervention with forced simultaneous entry method. Two-sided p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® version 26 (Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

The ORENTRA trial included 132 participants in total. Ninety patients had complete assessments of renal graft fibrosis score, mGFR, uEGF, and sUmod at baseline and of which 48 patients had all assessments repeated at the end of study. All assessments were performed within the same day of the respective study visit. Patient characteristics and study variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study variables of patients with complete assessments

| Baseline1 | Baseline2 | End of study | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 90 | 48 | |

| Recipient age, yr | 52.4±14.5 | 54.3±13.2 | |

| Recipient gender, female | 21 (23.3) | 16 (33.3) | |

| Ethnicity, Caucasian | 86 (95.6) | 45 (93.8) | |

| Randomized to n-3 PUFA group | 42 (46.6) | 23 (47.9) | |

| Marine n-3 PUFA, wt% | 6.2±2.0 | 6.5±1.6 | 8.8±3.0 |

| Renal graft fibrosis, % | 9 (6, 16) | 10 (5, 18) | 12 (6, 22) |

| mGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 55.5±13.2 | 51.1±12.5 | 56.8±14.9 |

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 69.1±19.9 | 62.2±19.3 | 68.2±23.3 |

| uEGF, µg/g creatinine | 21.6 (15.9, 28.7) | 21.4 (12.7, 24.9) | 19.7 (12.7, 27.2) |

| sUmod, ng/mL | 70.6 (49.1, 90.8) | 66.4 (44.2, 90.4) | 67.0 (46.1, 85.1) |

| uACR, mg/mmoL | 3.5 (1.6, 10.3) | 3.9 (1.4, 11.0) | 3.2 (1.0, 7.4) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 132±15 | 136±16 | 129±15 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 82±10 | 82±9 | 79±8 |

| Current smoker | 11 (12.2) | 8 (16.6) | 5 (10.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus (incl. PTDM) | 22 (24.4) | 10 (20.8) | 12 (25.0) |

| Immunosuppression regimen | |||

| Tacrolimus | 88 (97.7) | 48 (100) | 46 (95.8) |

| Tacrolimus trough level, μg/L | 6.3 (5.2, 7.4) | 6.2 (5.2, 7.6) | 5.6 (4.7, 6.9) |

| Cyclosporine | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 2 (4.2) |

| mTOR inhibitor | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Mycophenolate | 90 (100) | 48 (100) | 48 (100) |

| Prednisolone | 90 (100) | 48 (100) | 48 (100) |

| Living donor | 25 (27.8) | 10 (20.8) | |

| DGF post-transplant | 7 (7.8) | 2 (4.2) | |

| Biopsy-proven acute rejection | 17 (18.9) | 11 (22.9) | 5 (10.4) |

Patient characteristics presented as mean ± standard deviation for values with normal distribution, as median (interquartile range) for values with non-normal distribution and n (%) for categorical data. wt%, weight percentage of total plasma phospholipid fatty acids; mGFR, measured glomerular filtration rate; uEGF, urine epidermal growth factor; uACR, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio; PTDM, post-transplant diabetes mellitus; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin.

All patients with complete assessments at baseline.

Patients with complete assessments both at baseline and at end of study.

All patients in this post hoc analysis received induction therapy with basiliximab (20 mg on transplantation day [day 0] and day 4) and methylprednisolone (250–350 mg on day 0) intravenously. Maintenance immunosuppressive regimen for almost all patients consisted of tacrolimus (target trough 3–7 μg/L), mycophenolate mofetil (750 mg twice daily), and prednisolone (20 mg daily from day 1, gradually tapered down to a maintenance dose of 5 mg daily 6 months after transplantation).

In patients of this post hoc analysis, protocol transplant biopsies revealed 17 (18.9%) acute rejections at baseline (16 cases were subclinical, 1 suspected) versus 5 (10.4%) cases at end of study (all subclinical). Seven KTRs experienced delayed graft function (DGF) after transplantation, and four of these had also subclinical acute rejections at the baseline visit.

In the 48 patients with complete assessments both at baseline and at end of study, change in uEGF normalized to urinary creatinine (uEGF/Cr) was associated with change in sUmod during follow-up (univariable linear regression, standardized β-coefficient [Std. β-coeff] = 0.508 [p = 0.001]) (Fig. 1). No significant differences were found between the marine n-3 PUFA group and the control group in change of uEGF/Cr (p = 0.267) and sUmod (p = 0.613) levels during follow-up (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Scatter plot with linear regression line showing association between change in sUmod and change in uEGF during follow-up.

Table 2.

Post-interventional changes of uEGF and sUmod levels between treatment groups

| Marine, n-3 PUFA group | Control group | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| uEGF/Cr, μg/g creatinine | −1.93±9.51 | 1.62±7.24 | 0.267 |

| sUmod, ng/mL | −1.84±18.62 | 1.54±13.21 | 0.613 |

Post-interventional changes shown as mean ± standard deviation. Differences between treatment groups were evaluated using analysis of covariance with adjustment for baseline values.

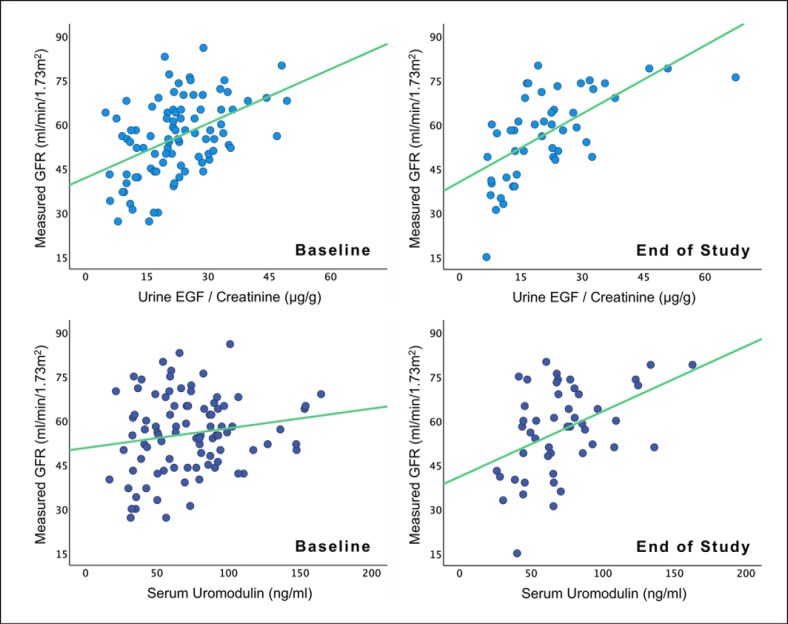

Associations with Measured Glomerular Filtration Rate

In univariable analysis, there were positive associations between uEGF/Cr and mGFR both at baseline (Std. β-coeff = 0.457 [p = <0.001]) and at end of study (Std. β-coeff = 0.637 [p = <0.001]). sUmod was not significantly associated with mGFR at baseline (Std. β-coeff = 0.163 [p = 0.126]), but there was a positive association at end of study (Std. β-coeff = 0.443 [p = 0.002]). Associations between uEGF/Cr and mGFR were stronger than between sUmod and mGFR at both time points (Table 3, Fig. 2). In multivariable analysis, the results remained unchanged.

Table 3.

Associations of uEGF and sUmod with measured glomerular filtration rate

| Measured glomerular filtration rate | N | unstd. β-coeff (95% CI) | std. β-coeff | p value | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable linear regression analysis | |||||

| Baseline | |||||

| uEGF/Cr | 90 | 0.617 (0.362, 0.871) | 0.457 | <0.001 | 0.209 |

| sUmod | 90 | 0.067 (−0.019, 0.153) | 0.163 | 0.126 | 0.026 |

| End of study | |||||

| uEGF/Cr | 48 | 0.773 (0.495, 1.050) | 0.637 | <0.001 | 0.405 |

| sUmod | 48 | 0.222 (0.088, 0.355) | 0.443 | 0.002 | 0.196 |

|

| |||||

| Multivariable linear regression analysis | |||||

| Baseline | |||||

| uEGF/Cr | 90 | 0.596 (0.291, 0.901) | 0.432 | <0.001 | 0.309* |

| sUmod | 90 | 0.068 (−0.029, 0.165) | 0.159 | 0.165 | 0.187* |

| End of study | |||||

| uEGF/Cr | 48 | 0.668 (0.359, 0.977) | 0.532 | <0.001 | 0.625* |

| sUmod | 48 | 0.183 (0.029, 0.336) | 0.345 | 0.021 | 0.488* |

The following variables were included in the multivariable model: recipient age and gender, marine n-3 PUFA intervention, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, smoking status, diabetes mellitus (including post-transplant diabetes mellitus), donor status (living/deceased), DGF, and biopsy-proven acute rejection. Unstd., unstandardized; Std.; standardized, β-coeff., β-coefficient; CI, confidence intervals.

R2 for the full multivariable linear regression model with all variables.

Fig. 2.

Scatter plots with linear regression lines showing associations of uEGF and sUmod with measured glomerular filtration rate at baseline and at end of study.

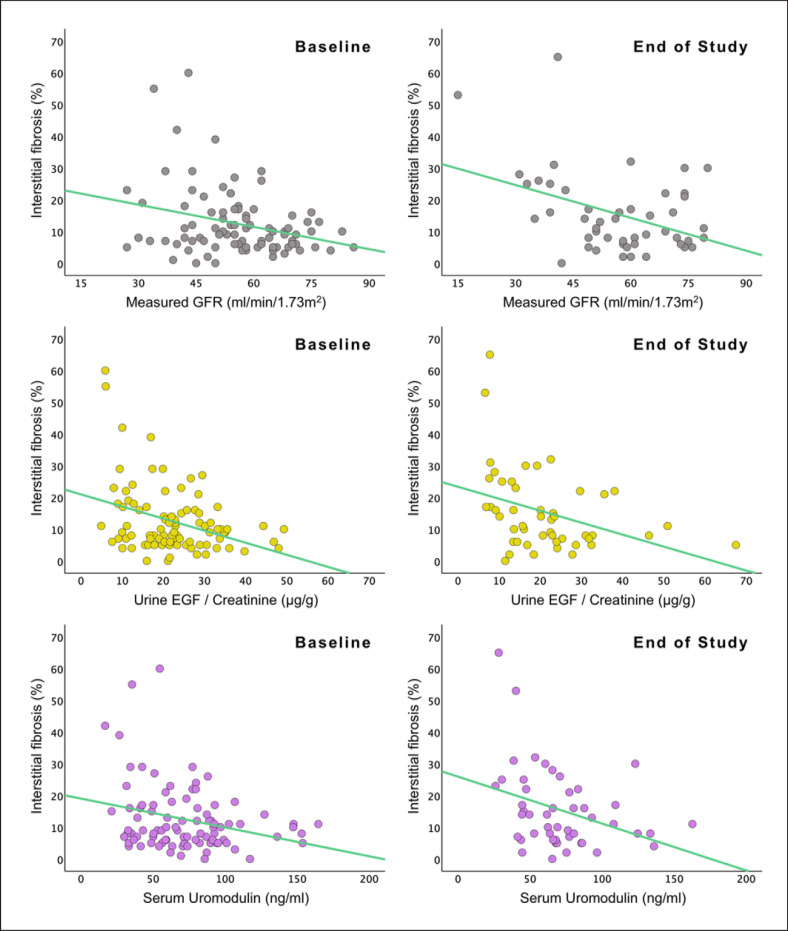

Associations with Graft Interstitial Fibrosis Score

In univariable analysis, uEGF/Cr, sUmod, and mGFR had all similar inverse associations with graft IF% score, both at baseline (Std. β-coeff = −0.349 [p = 0.001], −0.274 [p = 0.009], and −0.289 [p = 0.006], respectively) and at end of study (Std. β-coeff = −0.365 [p = 0.011], −0.347 [p = 0.016], and −0.405 [p = 0.004], respectively). All associations were generally stronger at end of study (Table 4; Fig. 3). In multivariable analysis, the results were largely unchanged.

Table 4.

Associations of uEGF, sUmod, and measured glomerular filtration rate with graft IF % score

| Graft interstitial fibrosis percentage score | N | unstd. β-coeff (95% CI) | std. β-coeff | p value | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable linear regression analysis | |||||

| Baseline | |||||

| uEGF/Cr | 90 | −0.381 (−0.597, −0.165) | −0.349 | 0.001 | 0.122 |

| sUmod | 90 | −0.091 (−0.159, −0.023) | −0.274 | 0.009 | 0.075 |

| mGFR | 90 | −0.233 (−0.397, −0.070) | −0.289 | 0.006 | 0.084 |

| End of study | |||||

| uEGF/Cr | 48 | −0.377 (−0.663, −0.092) | −0.365 | 0.011 | 0.133 |

| sUmod | 48 | −0.148 (−0.267, −0.029) | −0.347 | 0.016 | 0.120 |

| mGFR | 48 | −0.345 (−0.576, −0.114) | −0.405 | 0.004 | 0.164 |

|

| |||||

| Multivariable linear regression analysis | |||||

| Baseline | |||||

| uEGF/Cr | 90 | −0.407 (−0.673, −0.140) | −0.360 | 0.003 | 0.213* |

| sUmod | 90 | −0.112 (−0.191, −0.033) | −0.317 | 0.006 | 0.201* |

| mGFR | 90 | −0.215 (−0.405, −0.024) | −0.262 | 0.028 | 0.171* |

| End of study | |||||

| uEGF/Cr | 48 | −0.495 (−0.836, −0.155) | −0.439 | 0.006 | 0.436* |

| sUmod | 48 | −0.172 (−0.323, −0.020) | −0.360 | 0.028 | 0.382* |

| mGFR | 48 | −0.527 (−0.829, −0.224) | −0.586 | 0.001 | 0.485* |

The following variables were included in the multivariable model: recipient age and gender, marine n-3 PUFA intervention, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, smoking status, diabetes mellitus (including post-transplant diabetes mellitus), donor status (living/deceased), DGF, and biopsy-proven acute rejection. Unstd., unstandardized; Std.; standardized, β-coeff., β-coefficient; CI, confidence intervals; mGFR, measured glomerular filtration rate.

R2 for the full multivariable linear regression model with all variables.

Fig. 3.

Scatter plots with linear regression lines showing associations of measured glomerular filtration rate, uEGF, and sUmod with graft interstitial fibrosis percentage score at baseline and at end of study.

Discussion/Conclusion

In this post hoc analysis of the ORENTRA trial, uEGF/Cr was positively associated with mGFR both at baseline and at end of study, while sUmod was only associated with mGFR at end of study. uEGF/Cr, sUmod, and mGFR had inverse associations with graft IF% score at both time points. All associations were generally stronger at end of study than at baseline, and the results remained unchanged in multivariable analysis.

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate the associations of sUmod and uEGF with mGFR and kidney allograft fibrosis in the same cohort. Our findings are consistent with previous reports, which have shown that uEGF levels decrease concurrently with progressive graft failure in KTRs [27], and are inversely correlated with histological scores of interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy in patients with nephrotic syndrome [12]. Similar results were found in a study on sUmod in patients with CKD, where those with lowest sUmod levels had most severe tubular atrophy [28].

Circulating uromodulin is reported to be linearly correlated with eGFR in CKD patients and may help identify early stages of kidney damage when creatinine is still in the normal range [10, 11]. In our study, sUmod was associated with mGFR at the end of study, 1 year after transplantation. However, we found no significant association between sUmod and mGFR at baseline. One possible explanation for this is that sUmod needs time to achieve steady state in circulation after its release from tubular epithelial cells. Based on experiments with urinary excretion, it has been estimated that uromodulin has a half-life of 16 h [29], but it may be highly variable, from 3 h up to 7 days [30]. No study has examined the turnover rate of circulating uromodulin. At 8 weeks post-transplant, kidney graft function may not be fully stabilized for all patients in our study, and subsequently not all patients would have reached steady state in their sUmod levels.

We found generally stronger associations for all markers at end of study compared to baseline. This is most likely again due to unstable graft function in a substantial number of patients at the baseline visit, either caused by acute graft rejection or DGF (Table 1). Although not statistically significant, mean mGFR increased by the end of study, possibly due to recovery from these events. Recent studies have also shown that, compared to controls, uEGF levels are lower in KTRs with acute rejection [31], and sUmod levels are lower in KTRs with DGF [11]. Also, in the general population, patients who experience acute kidney injury are reported to have lower levels of both uEGF and sUmod [32, 33]. Nevertheless, adjusting for acute rejections, DGF, and other clinically relevant variables did not change the results in multivariable regression analysis, which signals that uEGF/Cr and sUmod have robust associations with mGFR and graft IF% score.

In the kidney, both uromodulin and EGF originate from the loop of Henle and the DCT [11, 16]. In line with this, median sUmod and uEGF/Cr levels changed minimally from baseline to end of study, as graft IF% scores were only marginally higher by end of study (Table 1). Change in sUmod and uEGF/Cr levels during follow-up also corresponded well with each other in our study population (Fig. 1). Both uEGF and sUmod are stable in long-term storage, as well as after repeated freeze-thaw cycles, and they can be reliably measured in their respective compartments (blood and urine) [11, 34]. However, in situations where immediate status of kidney function is warranted, uEGF may be more appropriate than sUmod, as it is excreted directly from the kidneys. On the other hand, treatment with calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), the cornerstone of immunosuppression in KTRs, has been associated with lower uEGF excretion [35]. There is conflicting data on this [27], and it is unclear if this EGF-inhibiting effect differs between types of CNI and whether it is correlated with CNI drug concentration.

The strength of the current study is the use of precise fibrosis scoring in kidney allografts and mGFR for analyses at two time points. Limitations include possible sampling bias in kidney biopsies, and many participants did not have all measurements repeated, leaving only 48 out of 90 participants from baseline for our analysis at end of study. Nonetheless, the patient characteristics did not change significantly, except for a higher percentage of female participants at end of study, which is unlikely to have influenced our findings. The follow-up time in the current study was also limited to 44 weeks. A longer follow-up with more repeated study assessments might provide further insights into the clinical utility of uEGF and sUmod. We used sUmod in our study and using urinary uromodulin instead may produce different results [5]. However, uromodulin may aggregate in the urine and cause inaccurate measurements if the urine samples are not handled adequately [36]. Urinary uromodulin excretion is also subject to considerable variations and may be affected by extrarenal factors [9].

In conclusion, uEGF/Cr was positively associated with mGFR, both at 8 weeks and 1 year post-transplant. sUmod was only associated with mGFR 1 year after transplantation. uEGF/Cr, sUmod, and mGFR have similar associations with the severity of kidney allograft fibrosis at both time points. Our results indicate a possible role of both uEGF/Cr and sUmod in the follow-up of KTRs for detecting early stages of fibrosis development.

Statement of Ethics

Study approval statement: This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Norway (approval number REK 2012/1419) and the Norwegian Medicines Agency. The trial was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Clinical.Trials.gov identifier NCT01744067, ORENTRA). Consent to participate statement: Study participants were given verbal and written information about the nature, purpose, possible risk, and benefit of the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the national regulatory requirements.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The other authors have no disclosures. The results presented in this article have not been published previously in whole or part.

Funding Sources

This research was funded by Akershus University Hospital, Norway. The funder had no role in study design; data collection, analysis, or reporting; or the decision to submit for publication.

Author Contributions

Research idea and study design: J.C., I.A.E., and M.S.; data acquisition: J.C., I.A.E., and T.M.T.; data analysis/interpretation: J.C., I.A.E., and T.M.T.; statistical analysis: J.C.; supervision or mentorship: B.W., T.J., and M.S. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hilde Loge Nilsen and all our colleagues at Department of Clinical Molecular Biology (EpiGen), Division of Medicine, Akershus University Hospital. We thank the study participants of the ORENTRA trial for their contributions.

References

- 1.Nankivell BJ, Borrows RJ, Fung CL, O'Connell PJ, Allen RD, Chapman JR. The natural history of chronic allograft nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2003;349((24)):2326–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wekerle T, Segev D, Lechler R, Oberbauer R. Strategies for long-term preservation of kidney graft function. Lancet. 2017;389((10084)):2152–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31283-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porrini E, Ruggenenti P, Luis-Lima S, Carrara F, Jimenez A, de Vries APJ, et al. Estimated GFR: time for a critical appraisal. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019;15((3)):177–90. doi: 10.1038/s41581-018-0080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uslu A, Hur E, Sen C, Sen S, Akgun A, Tasli FA, et al. To what extent estimated or measured GFR could predict subclinical graft fibrosis: a comparative prospective study with protocol biopsies. Transpl Int. 2015;28((5)):575–81. doi: 10.1111/tri.12534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pivin E, Ponte B, de Seigneux S, Ackermann D, Guessous I, Ehret G, et al. Uromodulin and nephron mass. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13((10)):1556–7. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03600318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ponte B, Devuyst O. Circulating uromodulin and risk of cardiovascular events and kidney failure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15((5)):589–91. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03580320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rampoldi L, Scolari F, Amoroso A, Ghiggeri G, Devuyst O. The rediscovery of uromodulin (Tamm-Horsfall protein): from tubulointerstitial nephropathy to chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2011;80((4)):338–47. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tokonami N, Takata T, Beyeler J, Ehrbar I, Yoshifuji A, Christensen EI, et al. Uromodulin is expressed in the distal convoluted tubule, where it is critical for regulation of the sodium chloride cotransporter NCC. Kidney Int. 2018;94((4)):701–15. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devuyst O, Olinger E, Rampoldi L. Uromodulin: from physiology to rare and complex kidney disorders. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13((9)):525–44. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steubl D, Block M, Herbst V, Nockher WA, Schlumberger W, Satanovskij R, et al. Plasma uromodulin correlates with kidney function and identifies early stages in chronic kidney disease patients. Medicine. 2016;95((10)):e3011. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scherberich JE, Gruber R, Nockher WA, Christensen EI, Schmitt H, Herbst V, et al. Serum uromodulin-a marker of kidney function and renal parenchymal integrity. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33((2)):284. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ju W, Nair V, Smith S, Zhu L, Shedden K, Song PXK, et al. Tissue transcriptome-driven identification of epidermal growth factor as a chronic kidney disease biomarker. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7((316)):316ra193. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac7071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azukaitis K, Ju W, Kirchner M, Nair V, Smith M, Fang Z, et al. Low levels of urinary epidermal growth factor predict chronic kidney disease progression in children. Kidney Int. 2019;96((1)):214–21. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gipson DS, Trachtman H, Waldo A, Gibson KL, Eddy S, Dell KM, et al. Urinary epidermal growth factor as a marker of disease progression in children with nephrotic syndrome. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5((4)):414–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2019.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu L, Li XQ, Chang DY, Zhang H, Li JJ, Wu SL, et al. Associations of urinary epidermal growth factor and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 with kidney involvement in patients with diabetic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35((2)):291–7. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfy314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeng F, Harris RC. Epidermal growth factor, from gene organization to bedside. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;28:2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meybosch S, De Monie A, Anne C, Bruyndonckx L, Jurgens A, De Winter BY, et al. Epidermal growth factor and its influencing variables in healthy children and adults. PLoS One. 2019;14((1)):e0211212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steubl D, Buzkova P, Garimella PS, Ix JH, Devarajan P, Bennett MR, et al. Association of serum uromodulin with ESKD and kidney function decline in the elderly: the cardiovascular health study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;74((4)):501–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norvik JV, Harskamp LR, Nair V, Shedden K, Solbu MD, Eriksen BO, et al. Urinary excretion of epidermal growth factor and rapid loss of kidney function. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;36((10)):1882. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bostom A, Steubl D, Garimella PS, Franceschini N, Roberts MB, Pasch A, et al. Serum uromodulin: a biomarker of long-term kidney allograft failure. Am J Nephrol. 2018;47((4)):275–82. doi: 10.1159/000489095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yepes-Calderon M, Sotomayor CG, Kretzler M, Gans ROB, Berger SP, Navis GJ, et al. Urinary epidermal growth factor/creatinine ratio and graft failure in renal transplant recipients: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Med. 2019;8((10)):1673. doi: 10.3390/jcm8101673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eide IA, Reinholt FP, Jenssen T, Hartmann A, Schmidt EB, Asberg A, et al. Effects of marine n-3 fatty acid supplementation in renal transplantation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Transplant. 2019;19((3)):790–800. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eide IA, Jenssen T, Hartmann A, Diep LM, Dahle DO, Reisaeter AV, et al. The association between marine n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid levels and survival after renal transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10((7)):1246–56. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11931214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nilsson-Ehle P. Iohexol clearance for the determination of glomerular filtration rate: 15 years' experience in clinical practice. EJIFCC. 2001;13((2)):48–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farris AB, Adams CD, Brousaides N, Della Pelle PA, Collins AB, Moradi E, et al. Morphometric and visual evaluation of fibrosis in renal biopsies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22((1)):176–86. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009091005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor TP, Janech MG, Slate EH, Lewis EC, Arthur JM, Oates JC. Overcoming the effects of matrix interference in the measurement of urine protein analytes. Biomark Insights. 2012;7:1–8. doi: 10.4137/BMI.S8703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amado JA, De-Francisco AL, Botana MA, Pesquera C, Vázquez-de-Prada JA, Arias M. Influence of kidney or heart transplantation on the urinary excretion of epidermal growth factor. Transpl Int. 1994;7((2)):127–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00336474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prajczer S, Heidenreich U, Pfaller W, Kotanko P, Lhotta K, Jennings P. Evidence for a role of uromodulin in chronic kidney disease progression. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25((6)):1896–903. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grant AM, Neuberger A. The turnover rate of rabbit urinary Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein. Biochem J. 1973;136((3)):659–68. doi: 10.1042/bj1360659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lynn KL, Shenkin A, Marshall RD. Factors affecting excretion of human urinary Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein. Clin Sci. 1982;62((1)):21–6. doi: 10.1042/cs0620021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heidari SS, Nafar M, Kalantari S, Tavilani H, Karimi J, Foster L, et al. Urinary epidermal growth factor is a novel biomarker for early diagnosis of antibody mediated kidney allograft rejection: a urinary proteomics analysis. J Proteomics. 2021;240:104208. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2021.104208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwon O, Ahn K, Zhang B, Lockwood T, Dhamija R, Anderson D, et al. Simultaneous monitoring of multiple urinary cytokines may predict renal and patient outcome in ischemic AKI. Ren Fail. 2010;32((6)):699–708. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2010.486496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kusnierz-Cabala B, Gala-Bladzinska A, Mazur-Laskowska M, Dumnicka P, Sporek M, Matuszyk A, et al. Serum uromodulin levels in prediction of acute kidney injury in the early phase of acute pancreatitis. Molecules. 2017;22((6)):988. doi: 10.3390/molecules22060988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harskamp LR, Meijer E, van Goor H, Engels GE, Gansevoort RT. Stability of tubular damage markers epidermal growth factor and heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor in urine. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2019;57((10)):e265–e8. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2019-0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ledeganck KJ, De Winter BY, Van den Driessche A, Jurgens A, Bosmans JL, Couttenye MM, et al. Magnesium loss in cyclosporine-treated patients is related to renal epidermal growth factor downregulation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29((5)):1097–102. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Youhanna S, Weber J, Beaujean V, Glaudemans B, Sobek J, Devuyst O. Determination of uromodulin in human urine: influence of storage and processing. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29((1)):136–45. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.