Abstract

Background and Aims:

Spinal anaesthesia induced maternal hypotension in parturients undergoing caesarean delivery may lead to neonatal acidosis and fall in umbilical artery pH. The aim of this study was to compare low dose norepinephrine infusion with phenylephrine to see the effect on umbilical arterial pH and maternal blood pressure during spinal anaesthesia for caesarean delivery.

Methods:

In a randomised, double-blind study, 60 parturients belonging to American Society of Anesthesiologists grade II, age 18–35 years with singleton term pregnancy were divided into the phenylephrine group and norepinephrine group. Participants received prophylactic phenylephrine and norepinephrine infusion after spinal anaesthesia till the delivery of the baby at a fixed rate of 50 μg/min and 2.5 μg/min, respectively. The primary outcome was umbilical artery pH. Neonatal Apgar score, incidence of bradycardia and hypotension, number of boluses of vasopressor required and reactive hypertension were also compared.

Results:

The umbilical arterial pH was comparable between the groups (p = 0.38). Apgar scores were comparable (p = 0.17). Incidence of bradycardia was higher in phenylephrine group without reaching statistical significance (43.3% vs. 20%, P = 0.052). Incidence of hypotension was more but not significant in norepinephrine group compared to phenylephrine group (16.7% vs. 10%, P = 0.44). Number of vasopressor boluses and reactive hypertension episodes were comparable between both groups (p = 0.09).

Conclusion:

Low dose (2.5 μg/min) intravenous infusion of norepinephrine is a suitable alternative to phenylephrine in the maintenance of umbilical arterial pH and maternal blood pressure.

Keywords: Caesarean section, norepinephrine, phenylephrine, spinal anaesthesia

INTRODUCTION

Anaesthetic management of caesarean section always presents the anaesthesiologist with an additional responsibility of health of the foetus. Subarachnoid block (SAB) is the anaesthetic technique of choice for caesarean delivery. It is fast, easy to perform and provides excellent intraoperative analgesia.[1] However, hypotension is a frequent intraoperative complication following SAB. One of the severe consequences of hypotension is placental hypoperfusion.[2] It leads to decreased oxygen supply to the foetus, resulting in foetal hypoxia, and resultant neonatal acidosis as measured by the umbilical artery pH. The threshold pH for adverse neurological outcomes is 7.10 and the ideal umbilical artery pH is 7.26–7.30.[3] Lower pH can herald hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy and other serious neurological damage to the newborn, including cerebral palsy.[4]

Phenylephrine is the gold standard drug in obstetrics to counteract the hypotension.[5] It is often associated with a dose-related reflexive slowing of maternal heart rate (HR) and a corresponding decrease in cardiac output (CO).[6] Therefore, investigation of alternative vasopressor with less pronounced reflexive negative chronotropic effects is of interest. Norepinephrine has weak b-adrenergic receptor agonist activity (unlike phenylephrine) in addition to potent a-adrenergic receptor activity.[7,8] Comparative information for phenylephrine and norepinephrine with respect to efficacy, safety, side-effect profile, and neonatal outcome though available, is still limited. So, we compared the effect of phenylephrine and norepinephrine during spinal anaesthesia for elective caesarean delivery. The primary outcome was umbilical artery pH. Neonatal Apgar scores, maternal systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and HR, incidence of bradycardia and hypotension, number of boluses of vasopressor required, reactive hypertension, shivering, nausea and vomiting were secondary outcomes.

METHODS

This prospective, randomised, double-blind controlled study was conducted after obtaining Institutional Ethics Committee approval and was registered with Clinical Trials Registry of India (CTRI/2018/03/012773). Written informed consent was obtained from the parturients. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was conducted from April 2018 to June 2019. Sixty parturients belonging to American Society of Anesthesiologists grade II, aged 18–35 years with uncomplicated normal singleton term pregnancy scheduled to undergo elective caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia were enroled in this study. Patients with absolute/relative contraindications for spinal anaesthesia, with history of allergy to any of the study drugs, gestational hypertension, cardiovascular, cerebrovascular or renal disease, oligohydramnios, intrauterine growth restriction and patients suffering from connective tissue disorders which reduce blood flow to the placenta were excluded from the study. Patients with prolonged uterine incision to delivery time were also excluded.

Randomisation of the patients was done by a computer generated random number table. Group allocation concealment was performed by placing the details of group allocation in an opaque coloured sealed envelope. Patient and the investigator were both blinded to the study drugs. The study drugs were prepared in identical looking 50 ml syringes by a person not involved in the study.

All patients were evaluated a day prior to surgery to assess the fitness for spinal anaesthesia. Patients were kept fasted after midnight and pre-medicated with ranitidine 150 mg orally night before and on the morning of surgery. On arrival in the operating room, the patient was positioned on the operating table in the supine position with left lateral tilt using a standard sized wedge under the right buttock. HR, non-invasive blood pressure, continuous electrocardiogram and peripheral oxygen saturation were monitored using multichannel monitors (Aspire View, GE Healthcare, Madison, United States of America). Pulse rate was recorded using pulse oximetry and blood pressure was recorded using an automated non-invasive device that was cycled every 1 to 2 min until three consecutive measurements of SBP were recorded with a difference of not more than 10%. The mean values of blood pressure and HR at these times were calculated and defined as baseline values. An intravenous line was secured with an 18 gauge intravenous cannula. No pre-hydration was given.

Parturients were positioned sitting and standard spinal anaesthesia technique was followed. Under all aseptic precautions, the skin was infiltrated with lignocaine 2%. A 26-gauge Quincke spinal needle was inserted at L3-L4 or L4-L5 vertebral interspace using midline approach. After confirmation of free flow of cerebrospinal fluid, 2.2 ml of hyperbaric bupivacaine 0.5% (w/v) was injected intrathecally according to our protocol and the patient was returned to the tilted supine position. At the start of intrathecal injection, intravenous ringer lactate solution was rushed (maximum 90 ml/min) simultaneously through an 18 gauge cannula with fully opened clamp of infusion set from same height in all patients. Prophylactic infusion of the study drug was started through syringe infusion pump (Infutek 405) at the same time of hydration. Phenylephrine group (n = 30) received phenylephrine infusion at the rate of 60 mlh-1 (1 ml/min) (2 mg of phenylephrine diluted with 0.9% normal saline (NS) to make a total volume of 40 ml, resulting in a concentration of 50 μg/ml) and norepinephrine group (n = 30) received norepinephrine infusion at the rate of 60 mlh-1 (1 ml/min) (0.1 mg of norepinephrine diluted with 0.9% NS to make a total volume of 40 ml, resulting in a concentration of 2.5 μg/ml). The infusion was administered till the delivery of the baby. Doses of vasopressors were taken in equipotent ratio (20:1) to study the effects with equal potency.

To achieve a minimum sensory block level of T6 for dull pin-prick, the operation table was tilted to 15-20° head down position, if required. SBP, DBP, mean arterial pressure and HR were measured and recorded every minute after turning the patient supine until delivery of baby. For the purpose of this study, maternal hypotension was defined as decrease in SBP ≤20% of baseline values or less than 90 mm Hg and was managed by one ml bolus of the respective vasopressor through an infusion pump. Blood pressure 20% higher than baseline values after the use of the vasopressor infusion or bolus was labelled as reactive hypertension and was managed by discontinuing the vasopressor infusion. A HR lower than 60 beats per minute indicates bradycardia and it was managed expectantly or with increments of 0.3 mg of intravenous atropine if needed. The time from the spinal injection to skin incision, uterine incision and delivery of the baby was noted. Immediately after delivery, the surgeon was asked to apply double clamps to the umbilical cord. Umbilical arterial and venous samples were taken in two heparinised syringes from double clamped segment of the umbilical cord and then sent for blood gas analysis immediately (Radiometer ABL800 BASIC blood gas and electrolytes analyser). Neonatal status was assessed by Apgar scoring at 1 min and 5 min. Intraoperative maternal nausea, vomiting and shivering were also noted.

The statistical analysis was carried out using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, version 22.0 for Windows). Normality was checked using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The normally distributed data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared using Student’s t-test (unpaired); whereas the skewed data were presented with median and inter-quartile range (IQR). For non-normally distributed or ordinal data, Mann–Whitney test was used. For categorical/classified data, Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, whichever applicable was used. The data were presented as numbers or percentage. Haemodynamic responses were compared using Student’s t-test and also their trend within each group over time was analysed using repeated measure analysis of variance. Value of P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

The sample size was calculated by using a software (https://www.stat.ubc.ca). In a previous study, the mean umbilical artery pH was 7.30 with a SD of 0.06.[9] In order to achieve a mean difference of 0.05 in umbilical artery pH between the groups, and with 90% power and alpha of 5%, a minimum sample of 25 cases was required in each group. After allowing for 20% patient dropout or incomplete data, it was decided to recruit 30 patients in each group.

RESULTS

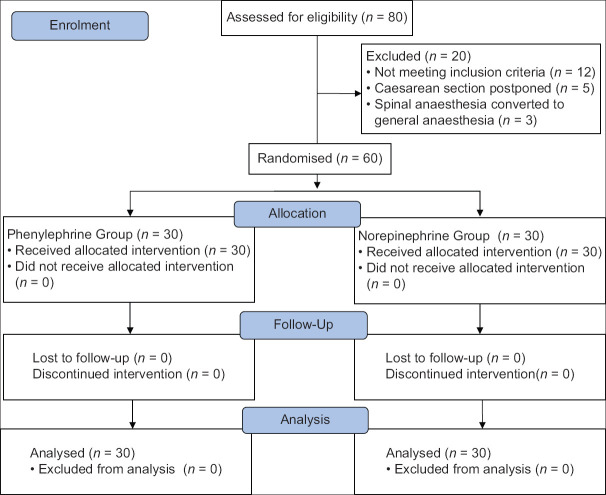

In the present study, 80 parturients were screened for eligibility; 12 parturients did not meet inclusion criteria, 5 cases were postponed and 3 were converted to general anaesthesia due to partial and inadequate effect of spinal anaesthesia. So, eventually, 60 parturients were analysed [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) chart. n: Number of patients

Both the groups were comparable in age, weight, height and parity. Mean time difference from spinal injection to uterine incision, spinal injection to delivery and uterine incision to delivery between both the groups was statistically insignificant [Table 1].

Table 1.

Patient and anaesthesia characteristics in the both groups

| Parameters | Phenylephrine (n=30) | Norepinephrine (n=30) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 26.20 (4.08) | 27.57 (4.51) | 0.22 |

| Weight (kg) | 60.96 (12.12) | 59.72 (5.60) | 0.61 |

| Height (cm) | 158.28 (4.03) | 156.63 (3.78) | 0.10 |

| Parityɫ | 2 (1.75-2) | 2 (2-3) | 0.95 |

| Baseline heart rate (beats/min) | 97.45 (17.94) | 94.08 (15.48) | 0.339 |

| Baseline systolic blood pressure (mm of Hg) | 121.15 (14.45) | 122.38 (16.49) | 0.421 |

| Spinal injection to supine position (seconds) | 26.17 (7.62) | 23.20 (11.66) | 0.24 |

| Spinal injection to uterine incision (min) | 10.45 (3.48) | 9.39 (3.67) | 0.25 |

| Spinal injection to delivery time (min) | 11.90 (3.66) | 10.68 (3.87) | 0.21 |

| Uterine incision to delivery time (seconds) | 84.43 (69.76) | 76.33 (45.95) | 0.59 |

Data represented as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range)ɫ n- number

The mean umbilical cord arterial blood pH (mean ± S.D.) was 7.28 ± 0.04 (95% confidence nterval 7.27-7.30) in phenylephrine group and 7.29 ± 0.04 (95% confidence interval 7.28-7.31) in norepinephrine group. The difference between the two groups was found to be statistically insignificant (P = 0.38). Umbilical cord venous blood pH values were comparable in both the groups (P = 0.20). There was no statistically significant difference in the neonatal Apgar score among the two groups at 1 min and 5 min (P > 0.05). Median (interquartile range) of Apgar score in phenylephrine group versus norepinephrine group at 1 min was 9 (7-9) versus 9 (9-9) and at 5 min was 9 (9-9) versus 9 (9-9), respectively [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of umbilical cord blood gases and neonatal outcome

| Parameters | Phenylephrine (n=30) | Norepinephrine (n=30) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial – pH | 7.28 (0.04) | 7.29 (0.04) | 0.38 |

| Venous – pH | 7.31 (.04) | 7.33 (.03) | 0.20 |

| Birth weight (kg) | 2.63 (0.41) | 2.81 (0.44) | 0.10 |

| Apgar - 1 minɫ | 9 (7-9) | 9 (9-9) | 0.17 |

| Apgar - 5 minɫ | 9 (9-9) | 9 (9-9) | 0.0 |

The data are represented as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range)ɫ, n - number

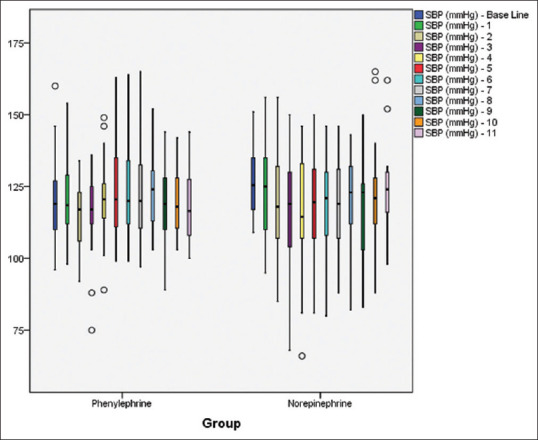

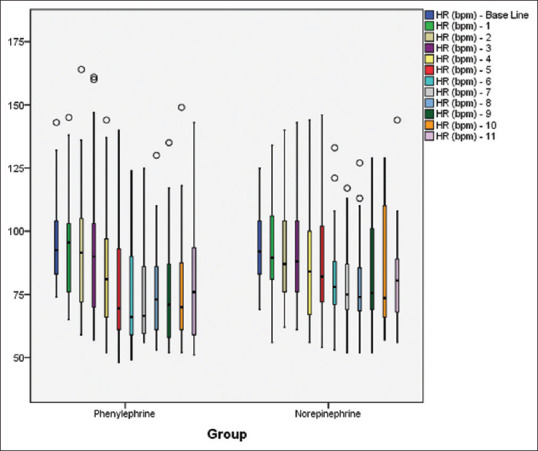

Mean ± SD difference of SBP at any time point between the two groups was found to be comparable [Figure 2]. At all-time intervals, the difference of mean HR between the two groups was found to be comparable [Figure 3].

Figure 2.

Mean systolic blood pressure at different time intervals in both groups

Figure 3.

Mean heart rate at different time intervals in both groups

Bradycardia was found in 13 (43.3%) patients with phenylephrine and in 6 (20%) patients with norepinephrine (P = 0.052). Bradycardia was managed expectantly. No other types of arrhythmias were found in any group. Hypotension was found in three (10%) patients in phenylephrine group and in five (16.7%) patients in norepinephrine group (P = 0.44). Median (IQR) number of vasopressor boluses used was 1 (1-1) in phenylephrine group versus 2 (1-2) in norepinephrine group (P = 0.09) Reactive hypertension was reported in none in phenylephrine group versus one (3.3%) patient in norepinephrine group (P = 0.31). Nausea was observed in one (3.3%) patient in norepinephrine group. Shivering and vomiting were not found in any patients [Table 3].

Table 3.

Other outcomes and side effects

| Phenylephrine (n=30) | Norepinephrine (n=30) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bradycardia (<60 beats/min), n (%) | 13 (43.3%) | 6 (20%) | 0.05 |

| Hypotension, n (%) | 3 (10%) | 5 (16.7%) | 0.44 |

| No. of vasopressor bolusesɫ | 1 (1-1) | 2 (1-2) | 0.09 |

| Reactive hypertension, n (%) | 0 | 1 (3.3%) | 0.31 |

| Shivering, n | 0 | 0 | |

| Nausea, n (%) | 0 | 1 (3.3%) | 0.31 |

| Vomiting, n | 0 | 0 |

The data are represented as mean (standard deviation), number (percentage) or median (interquartile range)ɫ n, No. = number

DISCUSSION

Anaesthesia in a parturient is a challenge for anaesthesiologists. A simple and feasible approach for prevention of post-spinal hypotension and neonatal acidosis during caesarean delivery would be a priority. A number of methods have been used to counter hypotension during caesarean section. These include intravenous crystalloid pre-hydration, co-loading and use of colloids; none of these, however, are fully reliable.[10] Vasopressor infusions remain a tangible method to maintain blood pressure and prevent maternal symptoms.[11]

In the present study, we compared phenylephrine and norepinephrine in equipotent doses (1:20). This ratio was taken on the basis of evidence in literature.[7,12]

The mean umbilical arterial blood pH difference between the two groups was found to be statistically not significant (P = 0.38). Only one patient in phenylephrine group had umbilical arterial pH less than 7.2 (7.18). Mean umbilical venous blood pH values were also comparable in both the groups (P = 0.20).

The outcomes of our study were consistent with the study by Ngan Kee et al.[7] The authors investigated the use of norepinephrine compared to phenylephrine as computer controlled infusion during caesarean delivery. Their results showed norepinephrine having similar efficacy as phenylephrine in maintaining umbilical cord blood pH and maternal blood pressure but with a greater HR.

As mentioned in previous studies, umbilical cord blood samples in this study were taken from the double-clamped segment of the cord after delivery for immediate blood gas analysis.[12,13]

None of the neonates in either group had Apgar score <7 at 1 or 5 min in this study. We found bradycardia (<60/min) in 20% parturients in norepinephrine group compared to phenylephrine (43.3%) group without reaching statistical significance (P = 0.052). A possible explanation for this was the low dose of vasopressor infusion used.

Our results were in line with studies done by Vallejo et al. and Sharkey et al. in relation to incidence of bradycardia in phenylephrine group and norepinephrine group. Vallejo et al. compared phenylephrine (0.1 μg/kg/min) versus norepinephrine (0.05 μg/kg/min) infusion in prevention of spinal hypotension and Sharkey et al. compared intermittent intravenous boluses of phenylephrine (100 μg) versus norepinephrine (6 μg) to prevent and treat spinal induced hypotension in caesarean deliveries.[14,15] Our results were not in line with a study done by Ngan Kee WD, in which the author found a significant incidence of bradycardia in phenylephrine group. This was a random allocation dose-response study where a rapid intravenous bolus of either norepinephrine at a dose of 5 to 12 μg or phenylephrine at a dose of 60 to 200 μg was given to treat hypotension after spinal anaesthesia.[16]

The incidence of hypotension was slightly more but not statistically significant in norepinephrine group (16.7% vs. 10%) which was in concordance with the results of Onwochei et al.[17] where a norepinephrine dose of less than 6 μg was used. The low dose of norepinephrine infusion (2.5 μg/min) was the probable cause of hypotension in our study.

In the current study, three patients required single bolus dose of vasopressor in phenylephrine group. Five patients required bolus of vasopressor in norepinephrine group, out of which two patients required single bolus and three patients required two boluses, but this was also not statistically significant. This could be explained by the 20:1 (50 μg: 2.5 μg) ratio of the drugs used in the study.

The usual route for infusion of norepinephrine is through central veins; however, peripheral administration has shown adequate safety in obstetric anaesthesia with no significant local side effects.[7,14] In our study, norepinephrine was used with some safety precautions such as adequate dilution (2.5 μg.mL-1), administration through wide bore cannula and the drug infusion in the same line with running fluids.

According to the consensus statement, prophylactic use of vasopressors after spinal block is preferred to reactive management (after development of hypotension) during caesarean delivery. It provides better haemodynamic profile and lower incidence of nausea and vomiting.[5,18] The recommended regimen for vasopressor administration is continuous infusion, which is superior to rescue bolus regimen.[19]

In the current study, a continuous diluted infusion of vasopressors was started prophylactically after spinal block and it was found that both drugs, norepinephrine and phenylephrine, were effective in controlling maternal blood pressure.

There are a few limitations associated with the study. It was a single centre study with a small sample size and inclusion of only healthy parturients in it. Phenylephrine and norepinephrine were used in a dose ratio of 20:1. Although our calculations were based on the evidence available in the literature, the equipotent ratio may not have been very accurate.

CONCLUSION

When given as a low dose infusion (2.5 μg/min), norepinephrine has similar efficacy compared to phenylephrine infusion (50 μg/min) in the maintenance of umbilical arterial pH and maternal blood pressure without producing any deleterious effect on neonatal outcome during spinal anaesthesia for caesarean delivery. Norepinephrine can be considered a suitable alternative to phenylephrine with an additional advantage of less incidence of maternal bradycardia.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Khaw KS, Kee WDN, Lee SW. Hypotension during spinal anesthesia for caesarean section:Implications, detection, prevention and treatment. Fetal Matern Med Rev. 2006;17:157–83. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fakherpour A, Ghaem H, Fattahi Z, Zaree S. Maternal and anaesthesia-related risk factors and incidence of spinal anaesthesia-induced hypotension in elective caesarean section:A multinomial logistic regression. Indian J Anaesth. 2018;62:36–46. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_416_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeh P, Emary K, Impey L. The relationship between umbilical cord arterial pH and serious adverse neonatal outcome:Analysis of 51 519 consecutive validated samples:Umbilical cord arterial pH and serious neonatal outcome. BJOG. 2012;119:824–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malin GL, Morris RK, Khan KS. Strength of association between umbilical cord pH and perinatal and long term outcomes:Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:c1471. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veeser M, Hofmann T, Roth R, Klöhr S, Rossaint R, Heesen M. Vasopressors for the management of hypotension after spinal anesthesia for elective caesarean section. Systematic review and cumulative meta-analysis:Vasopressors in spinal anaesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012;56:810–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2011.02646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puthenveettil N, Sivachalam SN, Rajan S, Paul J, Kumar L. Comparison of norepinephrine and phenylephrine boluses for the treatment of hypotension during spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section –A randomised controlled trial. Indian J Anaesth. 2019;63:995–1000. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_481_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ngan Kee WD, Lee SWY, Ng FF, Tan PE, Khaw KS. Randomized double-blinded comparison of norepinephrine and phenylephrine for maintenance of blood pressure during spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Anesthesiology. 2015;122:736–45. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah PJ, Agrawal P, Beldar RK. Intravenous norepinephrine and mephentermine for maintenance of blood pressure during spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section:An interventional double-blinded randomised trial. Indian J Anaesth. 2020;64:235–41. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_91_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manomayangkul K, Siriussawakul A, Nimmannit A, Yuyen T, Ngerncham S, Reesukumal K. Reference values for umbilical cord blood gases of newborns delivered by elective cesarean section. J Med Assoc Thai. 2016;99:611–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitra J, Roy J, Bhattacharyya P, Yunus M, Lyngdoh N. Changing trends in the management of hypotension following spinal anesthesia in cesarean section. J Postgrad Med. 2013;59:121–6. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.113840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nag DS. Vasopressors in obstetric anesthesia:A current perspective. World J Clin Cases. 2015;3:58–64. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohta M, Janani SS, Sethi AK, Agarwal D, Tyagi A. Comparison of phenylephrine hydrochloride and mephentermine sulphate for prevention of post spinal hypotension. Anaesthesia. 2010;65:1200–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohta M, Dubey M, Malhotra RK, Tyagi A. Comparison of the potency of phenylephrine and norepinephrine bolus doses used to treat post-spinal hypotension during elective caesarean section. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2019;38:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vallejo MC, Attaallah AF, Elzamzamy OM, Cifarelli DT, Phelps AL, Hobbs GR, et al. An open-label randomized controlled clinical trial for comparison of continuous phenylephrine versus norepinephrine infusion in prevention of spinal hypotension during cesarean delivery. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2017;29:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharkey AM, Siddiqui N, Downey K, Ye XY, Guevara J, Carvalho JCA. Comparison of intermittent intravenous boluses of phenylephrine and norepinephrine to prevent and treat spinal-induced hypotension in caesarean deliveries:Randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2019;129:1312–8. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000003704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ngan Kee WD. A Random-allocation graded dose–response study of norepinephrine and phenylephrine for treating hypotension during spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Anesthesiology. 2017;127:934–41. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onwochei DN, Ngan Kee WD, Fung L, Downey K, Ye XY, Carvalho JCA. Norepinephrine intermittent intravenous boluses to prevent hypotension during spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery:A sequential allocation dose-finding study. Anesth Analg. 2017;125:212–8. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kinsella SM, Carvalho B, Dyer RA, Fernando R, McDonnell N, Mercier FJ, et al. International consensus statement on the management of hypotension with vasopressors during caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2018;73:71–92. doi: 10.1111/anae.14080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siddik-Sayyid SM, Taha SK, Kanazi GE, Aouad MT. A randomized controlled trial of variable rate phenylephrine infusion with rescue phenylephrine boluses versus rescue boluses alone on physician interventions during spinal anesthesia for elective cesarean delivery:Anesth Analg. 2014;118:611–8. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000437731.60260.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]